Comparative Analysis of Climate Change Strategies in UK Cities: Report

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/18

|16

|4148

|79

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive comparison and contrast of the climate change strategies implemented by the local councils of Hull, Manchester, and Newcastle in the UK. The analysis begins with an introduction to the global challenge of climate change and the importance of local initiatives in addressing it. It then delves into each city's strategy, examining their objectives, commitments, and approaches to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate change impacts. The report highlights the strengths and weaknesses of each strategy, considering factors such as emission reduction targets, community engagement, and integration with national and international climate goals. The report also assesses the potential contributions of these local strategies to meeting national and international climate change targets, while also identifying potential lessons for other UK councils on developing and implementing their own climate action plans. The report examines specific areas such as road transport, domestic buildings, industrial and commercial buildings, and renewable energy usage. The report also considers Hull’s measures of success which are climate change future adaptation, natural resources sustainable use, and reduction of carbon dioxide emission as mitigation. The report concludes with a comparative analysis of the three cities' strategies, drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of their approaches.

1

CLIMATE CHANGE STRATEGIES REPORT: A CASE STUDY OF HULL, MANCHESTER

AND NEWCASTLE STRATEGIES

By

Name

Instructor’s/Professor’s Name

Course Number

College/University’s Name

Street

Date

CLIMATE CHANGE STRATEGIES REPORT: A CASE STUDY OF HULL, MANCHESTER

AND NEWCASTLE STRATEGIES

By

Name

Instructor’s/Professor’s Name

Course Number

College/University’s Name

Street

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

Introduction

Climate change is not only a threat to world but also one of the topmost challenges that earth is

facing today and in the future (Aldy & Pizer, 2015). Although, some parts of world are still

ignorant about climate change, the reduction in the availability of natural resources will certainly

change the manner in which the future generation will do business, learn in school, as well as the

job opportunities that will be pursued (Aguiar et al., 2018). It is thus worth noting that the quality

of life in future will be affected by changing climate impacts (Tol, 2018). In a bid to ensure that

changing climate impacts are addressed, governments, cities, organizations, individuals and

councils are coming up with holistic approaches.

It is worth noting that Manchester, Newcastle as well as Hull have come up with their own

approached to address climate change with missions of promoting sustainable development.

These cities have the knowhow that globalization as well as human population growth is swiftly

depleting resources. Therefore, the focus of this report is to compare and contrast Hull,

Manchester as well as Newcastle cities climate change strategies. Also, it assesses the strengths

and the weaknesses of the climate change strategies of three cities in association with

international standards. Besides, the EU climate change policy requires all cities to be

responsible for carbon emissions as well as to device machenisms of controlling climate change

impacts (Rayner & Jordan, 2016)

Comparing and Contrasting Hull, Newcastle and Manchester Climate Change Strategies

To begin with, Newcastle as a city has come up with a climate change strategy named

Newcastle City Council Climate Change (Mitigation) Strategy 2018 which has numerous

commitments helpful in CO2 reduction. It is worth noting that the commitments of the city

carbon emission reduction have their roots from the Nottingham Declaration in the year 2016

Introduction

Climate change is not only a threat to world but also one of the topmost challenges that earth is

facing today and in the future (Aldy & Pizer, 2015). Although, some parts of world are still

ignorant about climate change, the reduction in the availability of natural resources will certainly

change the manner in which the future generation will do business, learn in school, as well as the

job opportunities that will be pursued (Aguiar et al., 2018). It is thus worth noting that the quality

of life in future will be affected by changing climate impacts (Tol, 2018). In a bid to ensure that

changing climate impacts are addressed, governments, cities, organizations, individuals and

councils are coming up with holistic approaches.

It is worth noting that Manchester, Newcastle as well as Hull have come up with their own

approached to address climate change with missions of promoting sustainable development.

These cities have the knowhow that globalization as well as human population growth is swiftly

depleting resources. Therefore, the focus of this report is to compare and contrast Hull,

Manchester as well as Newcastle cities climate change strategies. Also, it assesses the strengths

and the weaknesses of the climate change strategies of three cities in association with

international standards. Besides, the EU climate change policy requires all cities to be

responsible for carbon emissions as well as to device machenisms of controlling climate change

impacts (Rayner & Jordan, 2016)

Comparing and Contrasting Hull, Newcastle and Manchester Climate Change Strategies

To begin with, Newcastle as a city has come up with a climate change strategy named

Newcastle City Council Climate Change (Mitigation) Strategy 2018 which has numerous

commitments helpful in CO2 reduction. It is worth noting that the commitments of the city

carbon emission reduction have their roots from the Nottingham Declaration in the year 2016

3

with objectives of reducing GHG (greenhouse gas) in association with the UK Climate Change

Act as well as well as Paris Climate Agreement. Although, Newcastle mitigation strategy may

not be comprehensive since it entirely depend overall world climate changes and policies, it has

the capacity of showing how the city is doing in its carbon emission mitigation (Newcastle City

Council, 2018).

On the other hand, Hull has developed a wide range of actions necessary to address the

challenges brought by climate change as well as depletion of natural resources through the

Environment and Climate Change Strategy developed by ECC SAG. The climate change

strategy build on ONE HULL Climate Change Strategy of 2007 with the major objective of

minisising of the city’s environmental impact, reducing causes of global climate change as well

as adapting climate future changes. Through achieving these responsibilities, Hull city strategy

will not only minimise economic, social as well as environmental effects but also take advantage

of resultant positive opportunities that will rise from carbon emissions reduction and economic

growth. Notably, Hull’s strategy acknowledges that climate change is not only a responsibility of

the city but also understands that it is a global problem and issue therefore it has responsibility of

its own emission which is also a contributor to the global problem.

Manchester on its part is considered a full time player in limiting climate change effects both at

the city level and at the global level. Manchester is not only thriving, zero waste, climate resilient

but also zero carbon city where all public, private, residents as well as third sector organizations

are active contributors and benefactors of the success of the city. Therefore, city’s objectives

which were built during 2010 to 2016 and are continuing to progress over medium, short as well

long-term are; resilience to climate change, sustainable jobs and economy, zero carbon emission,

with objectives of reducing GHG (greenhouse gas) in association with the UK Climate Change

Act as well as well as Paris Climate Agreement. Although, Newcastle mitigation strategy may

not be comprehensive since it entirely depend overall world climate changes and policies, it has

the capacity of showing how the city is doing in its carbon emission mitigation (Newcastle City

Council, 2018).

On the other hand, Hull has developed a wide range of actions necessary to address the

challenges brought by climate change as well as depletion of natural resources through the

Environment and Climate Change Strategy developed by ECC SAG. The climate change

strategy build on ONE HULL Climate Change Strategy of 2007 with the major objective of

minisising of the city’s environmental impact, reducing causes of global climate change as well

as adapting climate future changes. Through achieving these responsibilities, Hull city strategy

will not only minimise economic, social as well as environmental effects but also take advantage

of resultant positive opportunities that will rise from carbon emissions reduction and economic

growth. Notably, Hull’s strategy acknowledges that climate change is not only a responsibility of

the city but also understands that it is a global problem and issue therefore it has responsibility of

its own emission which is also a contributor to the global problem.

Manchester on its part is considered a full time player in limiting climate change effects both at

the city level and at the global level. Manchester is not only thriving, zero waste, climate resilient

but also zero carbon city where all public, private, residents as well as third sector organizations

are active contributors and benefactors of the success of the city. Therefore, city’s objectives

which were built during 2010 to 2016 and are continuing to progress over medium, short as well

long-term are; resilience to climate change, sustainable jobs and economy, zero carbon emission,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

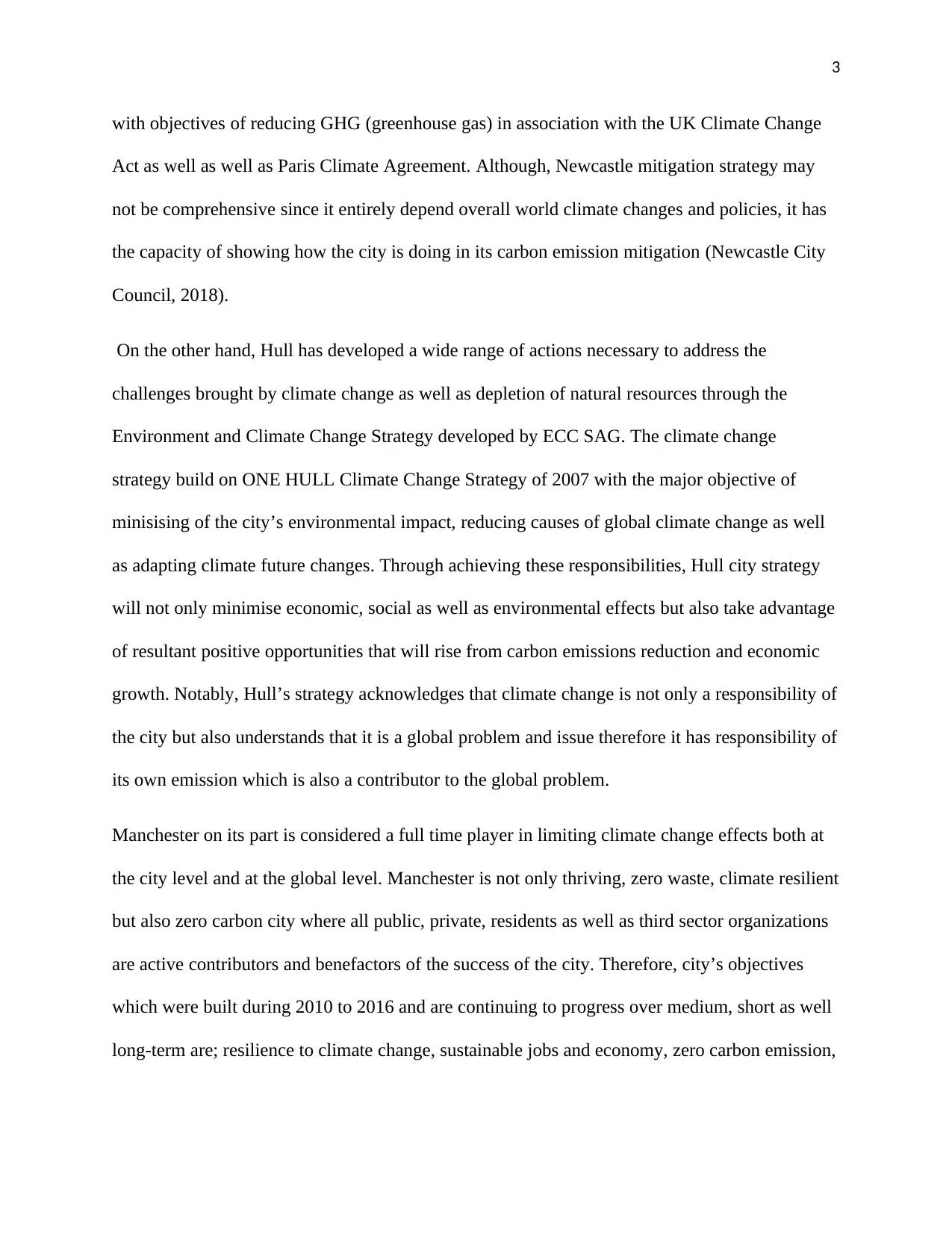

healthy communities and culture change which has projected a remarkable graph by 2050 as

shown below (Manchester Climate Change Agency, 2016).

Achievement of Manchester’s objectives towards climate change requires a comprehensive

strategy as well as adoption of several practices by the city. First, attracting investments,

innovations as well as business growth for low carbon emissions, as well as environmental

friendly’ services and goods. Notably, order for Manchester to ensure it promotes this objective

then it needs to develop as well as export globally the right ‘spaces’ and resources to innovate.

Secondly, Manchester strategy tends to invest on young people. Manchester clarifies that

investors, business leaders as well as 2050 politicians are at college, university and schools today

(Manchester Climate Change Agency, 2016). Therefore, the global outlook, skills and

knowledge they develop will be key to planet’s success and their own success. Manchester

supports and promotes young education towards low carbon emission to ensure that its residents

and students have full knowledge and skills required climate resilience.

After becoming a signatory in 2008 to Covenant of Mayors, Newcastle commitment to CO2

emissions reduction in the local authority area was at 21% from 2005 levels to the 2015 levels.

healthy communities and culture change which has projected a remarkable graph by 2050 as

shown below (Manchester Climate Change Agency, 2016).

Achievement of Manchester’s objectives towards climate change requires a comprehensive

strategy as well as adoption of several practices by the city. First, attracting investments,

innovations as well as business growth for low carbon emissions, as well as environmental

friendly’ services and goods. Notably, order for Manchester to ensure it promotes this objective

then it needs to develop as well as export globally the right ‘spaces’ and resources to innovate.

Secondly, Manchester strategy tends to invest on young people. Manchester clarifies that

investors, business leaders as well as 2050 politicians are at college, university and schools today

(Manchester Climate Change Agency, 2016). Therefore, the global outlook, skills and

knowledge they develop will be key to planet’s success and their own success. Manchester

supports and promotes young education towards low carbon emission to ensure that its residents

and students have full knowledge and skills required climate resilience.

After becoming a signatory in 2008 to Covenant of Mayors, Newcastle commitment to CO2

emissions reduction in the local authority area was at 21% from 2005 levels to the 2015 levels.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

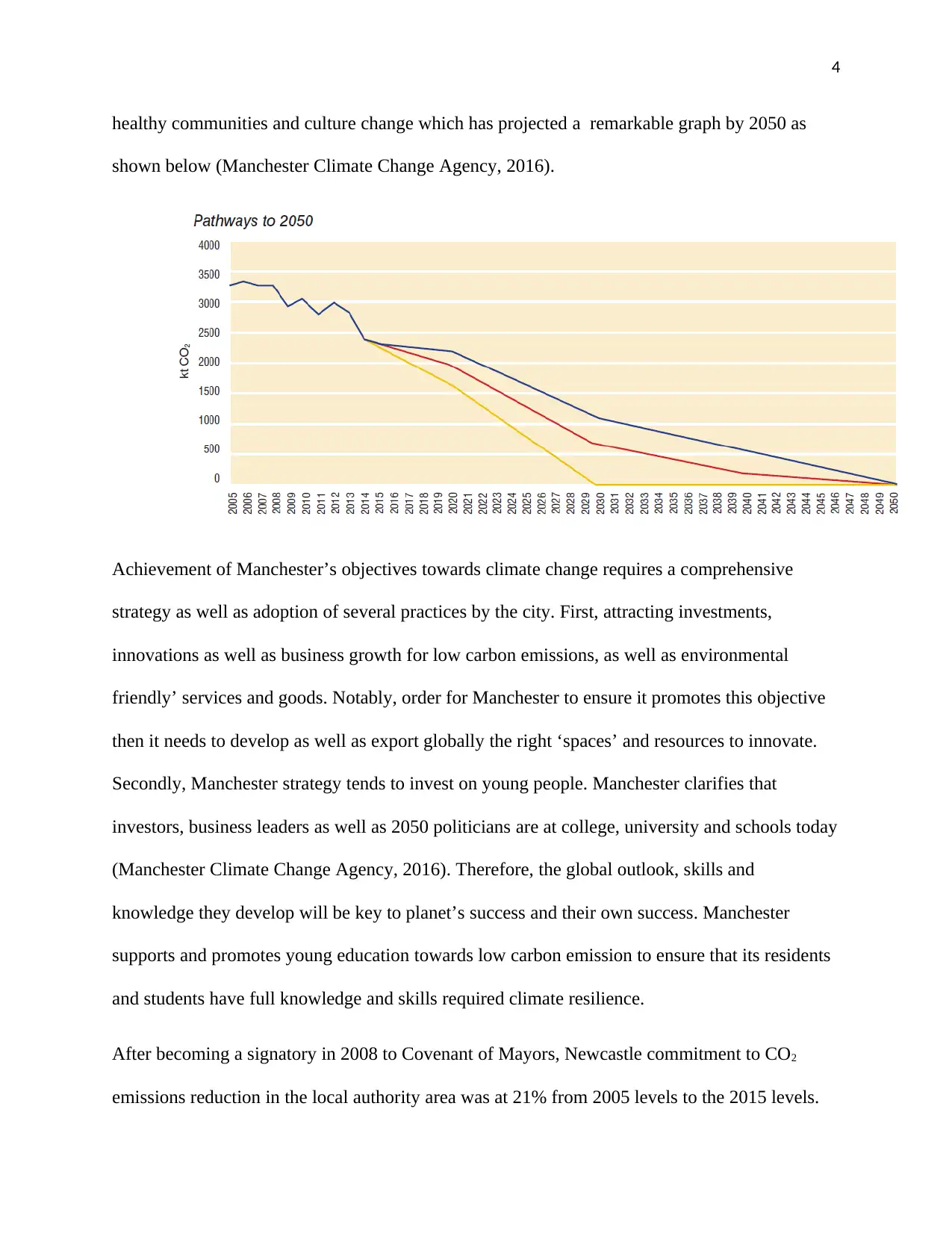

The local authority areas of target are road transport which reduced from 4.85million tCO2 in

2005 to 4.05 million tCO2 in 2015; industrial and commercial buildings which reduced from 7.95

million tCO2 in 2005 to 5.39 million tCO2 in 2015 and domestic buildings which reduced from

6.68 million tCO2 in 2005 to 4.40 million tCO2 in 2015 as shown in table 1 below.

Source: Newcastle Case study

Although, Newcastle has shown a 29% drop in CO2 emission between 2005 and 2015 due to

improvements in energy performance of the city’s housing stock and increase in the usage of

renewable energy like electrical power, the city still needs more mitigations since the transport as

well as the energy future of UK is uncertain. First, the trend of increase in renewable energy

(electricity generation) usage is expected to continue for decades as people tend to move from

gas or coal energy usage thereby reducing CO2 emission per unit of consumed electricity. Also,

the UK is considered by Newcastle city to be increasingly focusing providing low carbon heat

instead of the present approach which uses natural gas predominantly. Furthermore, the increase

in electric vehicles usage will certainly reduce the amount of emissions especially in road

The local authority areas of target are road transport which reduced from 4.85million tCO2 in

2005 to 4.05 million tCO2 in 2015; industrial and commercial buildings which reduced from 7.95

million tCO2 in 2005 to 5.39 million tCO2 in 2015 and domestic buildings which reduced from

6.68 million tCO2 in 2005 to 4.40 million tCO2 in 2015 as shown in table 1 below.

Source: Newcastle Case study

Although, Newcastle has shown a 29% drop in CO2 emission between 2005 and 2015 due to

improvements in energy performance of the city’s housing stock and increase in the usage of

renewable energy like electrical power, the city still needs more mitigations since the transport as

well as the energy future of UK is uncertain. First, the trend of increase in renewable energy

(electricity generation) usage is expected to continue for decades as people tend to move from

gas or coal energy usage thereby reducing CO2 emission per unit of consumed electricity. Also,

the UK is considered by Newcastle city to be increasingly focusing providing low carbon heat

instead of the present approach which uses natural gas predominantly. Furthermore, the increase

in electric vehicles usage will certainly reduce the amount of emissions especially in road

6

transport as a sector (Newcastle City Council, 2018). However, this strategy is still doubt since

the benefit will be maximized depending how electricity is generated as a source of energy for

electric vehicles (Watts at el., 2015). Generally, the Newcastle mitigation is faced with these

substantial uncertainties since they will impact how both national as well as city’s emissions

change over a span of time.

Since Newcastle achieved 29% CO2 emission reduction from 2005 to 2015 it is road transport,

domestic buildings as well as industrial and commercial sectors, the city’s current strategy is a

long-term one committed to achieving 100% clean energy in its road transport as well as

buildings by 2050. The influence in the CO2 in emissions in Newcastle change due to several

factors. First, the Local Plan of the city is set to ensure that new industrial, new housing as well

as commercial buildings are delivered to conform to the forecast population increase in the city

which will add more energy consumption in Newcastle (Newcastle City Council, 2018).

Furthermore, it is projected that road vehicles are becoming more efficient thereby reducing CO2

emissions for every distance covered. According to Nienhueser and Qiu (2016), a shift towards

usage of electric vehicles is likely to provide a lot of contribution towards reducing CO2

emissions.

First, reducing emissions from the operations of Newcastle’s Council, reducing emissions from

council offices, as well as reducing emissions from buildings such as; care homes and schools

among others. Secondly, Newcastle City Council working as well as supporting large

organizations and stakeholders like NHS and Universities which have also shown commitment

of reducing CO2 emissions through their established corporate commitments (Newcastle City

Council, 2018). Thirdly, the UK is increasingly putting more focus on energy efficiency

measures on industries which Newcastle promote by raising awareness as well as behavior

transport as a sector (Newcastle City Council, 2018). However, this strategy is still doubt since

the benefit will be maximized depending how electricity is generated as a source of energy for

electric vehicles (Watts at el., 2015). Generally, the Newcastle mitigation is faced with these

substantial uncertainties since they will impact how both national as well as city’s emissions

change over a span of time.

Since Newcastle achieved 29% CO2 emission reduction from 2005 to 2015 it is road transport,

domestic buildings as well as industrial and commercial sectors, the city’s current strategy is a

long-term one committed to achieving 100% clean energy in its road transport as well as

buildings by 2050. The influence in the CO2 in emissions in Newcastle change due to several

factors. First, the Local Plan of the city is set to ensure that new industrial, new housing as well

as commercial buildings are delivered to conform to the forecast population increase in the city

which will add more energy consumption in Newcastle (Newcastle City Council, 2018).

Furthermore, it is projected that road vehicles are becoming more efficient thereby reducing CO2

emissions for every distance covered. According to Nienhueser and Qiu (2016), a shift towards

usage of electric vehicles is likely to provide a lot of contribution towards reducing CO2

emissions.

First, reducing emissions from the operations of Newcastle’s Council, reducing emissions from

council offices, as well as reducing emissions from buildings such as; care homes and schools

among others. Secondly, Newcastle City Council working as well as supporting large

organizations and stakeholders like NHS and Universities which have also shown commitment

of reducing CO2 emissions through their established corporate commitments (Newcastle City

Council, 2018). Thirdly, the UK is increasingly putting more focus on energy efficiency

measures on industries which Newcastle promote by raising awareness as well as behavior

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

change campaign (Urry, 2015). Moreover, Newcastle council strategy is focused on street-

lighting replacement, council fleet replacement, improving efficiency of houses, and embracing

commercial PV programme among others.

Notably, Hull in known to be adapting its targets from the national targets due to unavailability

of data for Hull since 2005 with a baseline taken from 2008 Climate Change Act, Hull success

measures are established from three major key issues (ECC SAG, 2010). The measures are

climate change future adaptation, natural resources sustainable use, and reduction of carbon

dioxide emission as mitigation. To ensure that carbon dioxide emissions target of reduction is

achieved, Hull established carbon emission process of reporting in 2011. Also, using the 2005

baseline, Hull reduces carbon emissions by an approximate of 23.6 percent to 30% by 2015.

Besides, Hull projects a reduction of carbon emission by 34 percent to an estimate of 45% by

next year (2020).

Furthermore, using future climate change adaption as measure of success, Hull came up with a

number of strategies. Firstly, producing Adaption Risk Assessment Tool as well as identifying

major areas of assessment in 2011. Secondly, Producing Adaption Strategy and Action Plan for

the city in 2012 as well as adaption embedded ONE HULL working policies. Moreover, natural

resources sustainable use is another viable measure of target which is also in line with European

ecology (Lindner et al., 2010). First, in 2012 Hull held sustainable Procurement Conference

which there was sharing of best practice in Hull city. Secondly, the city holds from 2011 to 2020

inter-business events to ensure that it links design, innovation as well as production businesses

for providing or manufacturing services with least possible resources. Lastly, the city has

projected by 2020 for organisations and businesses not only to adopt but also to have sustainable

procurement processes.

change campaign (Urry, 2015). Moreover, Newcastle council strategy is focused on street-

lighting replacement, council fleet replacement, improving efficiency of houses, and embracing

commercial PV programme among others.

Notably, Hull in known to be adapting its targets from the national targets due to unavailability

of data for Hull since 2005 with a baseline taken from 2008 Climate Change Act, Hull success

measures are established from three major key issues (ECC SAG, 2010). The measures are

climate change future adaptation, natural resources sustainable use, and reduction of carbon

dioxide emission as mitigation. To ensure that carbon dioxide emissions target of reduction is

achieved, Hull established carbon emission process of reporting in 2011. Also, using the 2005

baseline, Hull reduces carbon emissions by an approximate of 23.6 percent to 30% by 2015.

Besides, Hull projects a reduction of carbon emission by 34 percent to an estimate of 45% by

next year (2020).

Furthermore, using future climate change adaption as measure of success, Hull came up with a

number of strategies. Firstly, producing Adaption Risk Assessment Tool as well as identifying

major areas of assessment in 2011. Secondly, Producing Adaption Strategy and Action Plan for

the city in 2012 as well as adaption embedded ONE HULL working policies. Moreover, natural

resources sustainable use is another viable measure of target which is also in line with European

ecology (Lindner et al., 2010). First, in 2012 Hull held sustainable Procurement Conference

which there was sharing of best practice in Hull city. Secondly, the city holds from 2011 to 2020

inter-business events to ensure that it links design, innovation as well as production businesses

for providing or manufacturing services with least possible resources. Lastly, the city has

projected by 2020 for organisations and businesses not only to adopt but also to have sustainable

procurement processes.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

Moreover, Hull strategy takes into consideration UK government’s carbon reduction 2020 targets

such as The UK Renewable Energy Strategy, UK Low Carbon Transport-A Greener Future, UK

Low Carbon Transition Plan, as well as the UK Low Carbon Industrial Strategy. Notably, Hull

adopts the UK Low Carbon Transition Plan which has five major themes (ECC SAG, 2010).

Firstly protecting the society from immediate climate change risks and preparation for the future.

Also, a low carbon building of the UK as well as limiting the future climate change severity

through new international climate agreements. Lastly, supporting businesses, communities as

well as individuals to effectively play their part with respect to climate change and sustainable

development.

Notably, Hull emission scenarios such as low scenario at 2oC, medium emission at 3.2oC and

high emission at 4oC depends on global mitigation efforts with regards to greenhouse gases being

emitted to the atmosphere.Therefore, it worth noting that, future changes in climate are likely to

have a lot of implications on earth (Blöschl et al., 2017). Therefore, as Hull move towards hotter

and dryer summers and warmer and wetter winters will certainly have an impact on animals and

plants habitats as well as increase in demands of goods as well as services. Therefore, Hull as a

city potential issues are; health and well being, biodiversity, flood risk, environmental services,

housing and buildings, industry and commerce, and awareness.

Moreover, Hull strategy takes into consideration UK government’s carbon reduction 2020 targets

such as The UK Renewable Energy Strategy, UK Low Carbon Transport-A Greener Future, UK

Low Carbon Transition Plan, as well as the UK Low Carbon Industrial Strategy. Notably, Hull

adopts the UK Low Carbon Transition Plan which has five major themes (ECC SAG, 2010).

Firstly protecting the society from immediate climate change risks and preparation for the future.

Also, a low carbon building of the UK as well as limiting the future climate change severity

through new international climate agreements. Lastly, supporting businesses, communities as

well as individuals to effectively play their part with respect to climate change and sustainable

development.

Notably, Hull emission scenarios such as low scenario at 2oC, medium emission at 3.2oC and

high emission at 4oC depends on global mitigation efforts with regards to greenhouse gases being

emitted to the atmosphere.Therefore, it worth noting that, future changes in climate are likely to

have a lot of implications on earth (Blöschl et al., 2017). Therefore, as Hull move towards hotter

and dryer summers and warmer and wetter winters will certainly have an impact on animals and

plants habitats as well as increase in demands of goods as well as services. Therefore, Hull as a

city potential issues are; health and well being, biodiversity, flood risk, environmental services,

housing and buildings, industry and commerce, and awareness.

9

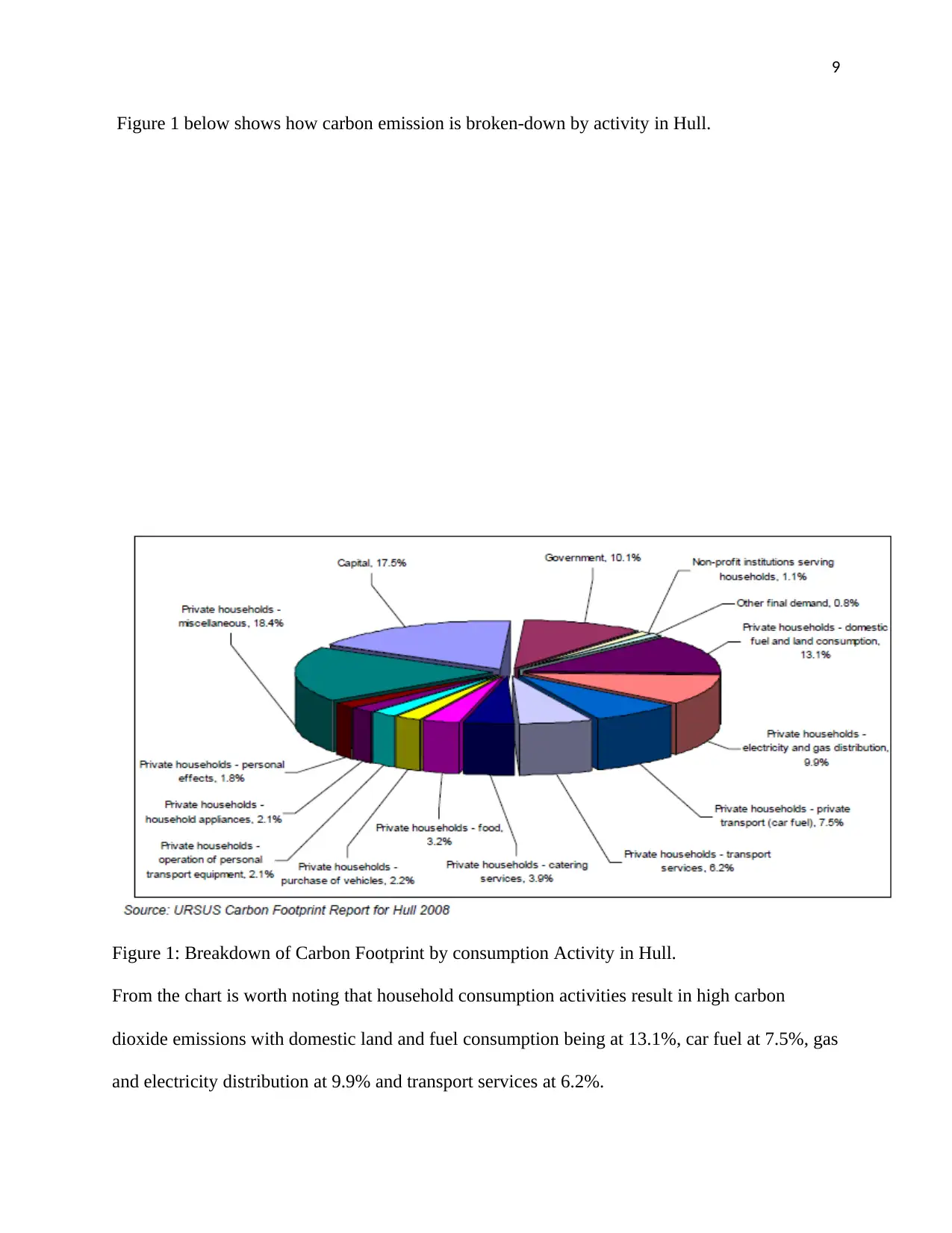

Figure 1 below shows how carbon emission is broken-down by activity in Hull.

Figure 1: Breakdown of Carbon Footprint by consumption Activity in Hull.

From the chart is worth noting that household consumption activities result in high carbon

dioxide emissions with domestic land and fuel consumption being at 13.1%, car fuel at 7.5%, gas

and electricity distribution at 9.9% and transport services at 6.2%.

Figure 1 below shows how carbon emission is broken-down by activity in Hull.

Figure 1: Breakdown of Carbon Footprint by consumption Activity in Hull.

From the chart is worth noting that household consumption activities result in high carbon

dioxide emissions with domestic land and fuel consumption being at 13.1%, car fuel at 7.5%, gas

and electricity distribution at 9.9% and transport services at 6.2%.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

Therefore strategically, Hull’s policies tend to raise and promote awareness by providing support

for business and homes, promoting as well as improving energy efficiency in new and existing

buildings (ECC SAG, 2010). Also, according to Araújo et al. (2011), use the natural environment

as a mechanism of mitigating and adapting climate change. Improve quality of life through

reducing carbon emission in transport sector as well as improve social outcome and health

through promotion of cycling, walking, public transport and alternative use of technologies and

fuels. Lastly, enhance efficiency as well as energy security through promoting renewable as well

as low carbon produced and used in Hull city (Affolderbach, Schulz, & Braun, 2018).

On the other hand, Manchester’s supports it strategy by enabling as incentivising institutional

investment. The city has already put forward investment incentives such as the installation of the

low carbon energy systems in institutions like Manchester Metropolitan at Birley Field Campus

University, Manchester City’s Football Academy, as well as in Town Hall and Central Library

transformations. Besides, organisations that show commitment to low carbon emission are

rewarded with reputational benefits and reduced energy bills.

Moreover, Manchester thematic actions outlines it initiatives with respect to energy, buildings,

transport, resources and waste, food, and green spaces as well as waterways. First, buildings

especially existing ones are poised to be retrofitted to ensure that their energy requirements are

minimised. Also, Manchester energy strategy is to take control, influence and ownership of

energy system of the city, businesses and residents through replacing the gas biogas as well as

hydrogen (Manchester Climate Change Agency, 2016). Besides, the strategy is poised to adapt

new infrastructure so that it can withstand high temperatures as well as extreme rainfall.

Furthermore, the strategy is poised to transform on the way to 2050 through new working

arrangements, digital communication technologies, well-planned as well as new developments

Therefore strategically, Hull’s policies tend to raise and promote awareness by providing support

for business and homes, promoting as well as improving energy efficiency in new and existing

buildings (ECC SAG, 2010). Also, according to Araújo et al. (2011), use the natural environment

as a mechanism of mitigating and adapting climate change. Improve quality of life through

reducing carbon emission in transport sector as well as improve social outcome and health

through promotion of cycling, walking, public transport and alternative use of technologies and

fuels. Lastly, enhance efficiency as well as energy security through promoting renewable as well

as low carbon produced and used in Hull city (Affolderbach, Schulz, & Braun, 2018).

On the other hand, Manchester’s supports it strategy by enabling as incentivising institutional

investment. The city has already put forward investment incentives such as the installation of the

low carbon energy systems in institutions like Manchester Metropolitan at Birley Field Campus

University, Manchester City’s Football Academy, as well as in Town Hall and Central Library

transformations. Besides, organisations that show commitment to low carbon emission are

rewarded with reputational benefits and reduced energy bills.

Moreover, Manchester thematic actions outlines it initiatives with respect to energy, buildings,

transport, resources and waste, food, and green spaces as well as waterways. First, buildings

especially existing ones are poised to be retrofitted to ensure that their energy requirements are

minimised. Also, Manchester energy strategy is to take control, influence and ownership of

energy system of the city, businesses and residents through replacing the gas biogas as well as

hydrogen (Manchester Climate Change Agency, 2016). Besides, the strategy is poised to adapt

new infrastructure so that it can withstand high temperatures as well as extreme rainfall.

Furthermore, the strategy is poised to transform on the way to 2050 through new working

arrangements, digital communication technologies, well-planned as well as new developments

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

which will reduce need to travel while supporting running, cycling, green routes and safe.

Generally, Hull strategy can be considered to be more comprehensive as it caters across

sustainable usage of resources, future climate change adaption and reduction in carbon dioxide

emission. On the other hand, Manchester strategy is also a comprehensive strategy with details

how it is committed towards resilience to climate change, sustainable jobs and economy, zero

carbon emission, healthy communities and culture change especially through supporting young

people in schools, universities and colleges as well as its residents and organization. However,

Newcastle’s mitigation majorly deals with CO2 emission reduction only within road transport,

industrial and domestic buildings thereby a lot of rooms to areas like air transport, rail transport

and young people involvement at large.

Weaknesses and Strengths of Newcastle, Manchester and Hull Climate Change Strategies

A strength, Manchester’s strategy is resilient as it is committed towards resilience to climate

change, sustainable jobs and economy, zero carbon emission, healthy communities and culture

change especially through supporting young people in schools, universities and colleges as well

as its residents and organization. Besides, the strategy takes into consideration not only it’s

residents, organizations and businesses but also provides room for its young generation to

acquire skills and knowledge to support future success of businesses, organizations and political

class. On the other hand, Hull strategy’s strength is that takes into consideration UK

government’s carbon reduction 2020 targets such as The UK Renewable Energy Strategy, UK

Low Carbon Transport-A Greener Future, UK Low Carbon Transition Plan, as well as the UK

Low Carbon Industrial Strategy which are well planned strategies. Also, Newcastle’ strength is

majorly depended universal reduction of CO2 emission through electric vehicles and national

policies.

which will reduce need to travel while supporting running, cycling, green routes and safe.

Generally, Hull strategy can be considered to be more comprehensive as it caters across

sustainable usage of resources, future climate change adaption and reduction in carbon dioxide

emission. On the other hand, Manchester strategy is also a comprehensive strategy with details

how it is committed towards resilience to climate change, sustainable jobs and economy, zero

carbon emission, healthy communities and culture change especially through supporting young

people in schools, universities and colleges as well as its residents and organization. However,

Newcastle’s mitigation majorly deals with CO2 emission reduction only within road transport,

industrial and domestic buildings thereby a lot of rooms to areas like air transport, rail transport

and young people involvement at large.

Weaknesses and Strengths of Newcastle, Manchester and Hull Climate Change Strategies

A strength, Manchester’s strategy is resilient as it is committed towards resilience to climate

change, sustainable jobs and economy, zero carbon emission, healthy communities and culture

change especially through supporting young people in schools, universities and colleges as well

as its residents and organization. Besides, the strategy takes into consideration not only it’s

residents, organizations and businesses but also provides room for its young generation to

acquire skills and knowledge to support future success of businesses, organizations and political

class. On the other hand, Hull strategy’s strength is that takes into consideration UK

government’s carbon reduction 2020 targets such as The UK Renewable Energy Strategy, UK

Low Carbon Transport-A Greener Future, UK Low Carbon Transition Plan, as well as the UK

Low Carbon Industrial Strategy which are well planned strategies. Also, Newcastle’ strength is

majorly depended universal reduction of CO2 emission through electric vehicles and national

policies.

12

On weaknesses, Newcastle’s strategy does not include CO2 emissions associated with rail travel

as well as air travel. Besides, Newcastle council’s strategy is largely depended on national

strategies rather than being much specific to emissions around the city and challenges that city

faces due to global. The 2050 100% clean energy can only be achieved universally since it will

mean that everyone Newcastle will be having electric vehicles which may not be possible by

2050 (Affolderbach, Schulz, & Braun, 2018). Besides, if the City is still targeting only a

reduction of 50% CO2 emission by 2030 which is a difference of 15 years from 2015 then it is

not viable to achieve 100% clean transition from 2030 2050 which has 20 years difference.

Furthermore, the target is majorly depend how much ready the UK, Europe and the entire world

is ready and willing to transform wholly to electric vehicle usage by 2050.

Furthermore, Hull strategy’s has probability of loopholes left especially due to unavailability of

data retrieved from Hull in relation to climate change before the year 2005. This gives a set back

since the level of confidence for predicting as well as projecting future climate changes may not

be comprehensive therefore provide high chances of errors in future projection. Although,

Manchester’s may not have much weaknesses but it is also facing uncertainties since climate

change is a global issue that requires participation and involvement of worldwide parties,

corporations, people and governments (Goldstein, 2016).

Conclusion

In conclusion, climate change and depletion of natural resources is a global issue that requires

governments, cities, organizations, individuals and councils to come up with holistic approaches

to address the their impacts. Manchester, Newcastle as well as Hull City are developing

strategies to address climate change with missions of promoting sustainable development. For

instance, with a target of 974 ktCO2, Newcastle has several climate change strategies to meet its

On weaknesses, Newcastle’s strategy does not include CO2 emissions associated with rail travel

as well as air travel. Besides, Newcastle council’s strategy is largely depended on national

strategies rather than being much specific to emissions around the city and challenges that city

faces due to global. The 2050 100% clean energy can only be achieved universally since it will

mean that everyone Newcastle will be having electric vehicles which may not be possible by

2050 (Affolderbach, Schulz, & Braun, 2018). Besides, if the City is still targeting only a

reduction of 50% CO2 emission by 2030 which is a difference of 15 years from 2015 then it is

not viable to achieve 100% clean transition from 2030 2050 which has 20 years difference.

Furthermore, the target is majorly depend how much ready the UK, Europe and the entire world

is ready and willing to transform wholly to electric vehicle usage by 2050.

Furthermore, Hull strategy’s has probability of loopholes left especially due to unavailability of

data retrieved from Hull in relation to climate change before the year 2005. This gives a set back

since the level of confidence for predicting as well as projecting future climate changes may not

be comprehensive therefore provide high chances of errors in future projection. Although,

Manchester’s may not have much weaknesses but it is also facing uncertainties since climate

change is a global issue that requires participation and involvement of worldwide parties,

corporations, people and governments (Goldstein, 2016).

Conclusion

In conclusion, climate change and depletion of natural resources is a global issue that requires

governments, cities, organizations, individuals and councils to come up with holistic approaches

to address the their impacts. Manchester, Newcastle as well as Hull City are developing

strategies to address climate change with missions of promoting sustainable development. For

instance, with a target of 974 ktCO2, Newcastle has several climate change strategies to meet its

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 16

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.