HSN753 Research Practice in Human Nutrition: Salt Intake in Kids

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/21

|16

|4514

|220

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the sodium and potassium intake of Australian children aged 8-11. The study involved urine samples and diet assessments to understand the impact of these minerals on children's health. Results indicated that while salt consumption was minimal, certain foods like bread, pastries, and dairy products contributed significantly to sodium and potassium intake. The report discusses the methodology, including participant recruitment, data collection, and analysis using specialized software. It also addresses challenges encountered during the study and suggests improvements for future research. The findings contribute to the understanding of dietary habits and their potential health implications for Australian children, emphasizing the importance of monitoring and managing sodium and potassium levels in their diets.

1

Salt intake in Australian children

Name of student

Name of University

Date

Salt intake in Australian children

Name of student

Name of University

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

Abstract

It is known that little intake of sodium and high potassium intake is helpful in the control,

prevention, reduction of high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases that may occur later

in life. The aim of the survey was to put on trial samples of urine and to assess the diet from

children in order to understand the effects of sodium and potassium in Australian children

with ages between 8 to 11 years in one Australian primary school (1). A sample of 27

children was selected in a span of two weeks. All these children had their urine samples

picked (about 72%) and those who carried the interview checked their diet for a period of 24

hours to ascertain the percentage of sodium and potassium content in the food they take. The

range of sodium intake was 2192 (1086-4785) milligram per day which is equivalent to 5.4

grams of salt, the intake of potassium was 1775 which also translates to 800-2980 milligrams

per day. It was evident that the frequency of consumption of salt was minimal. However,

there are certain foods that are known to have a high content of sodium and potassium; they

include bread, pastry, dairy products and some non-alcoholic drinks (2). Interestingly, most

participants participated in the exercise and were seen to be enjoying the whole process. We

can suggest that a large survey can be done for the confirmation of the findings and to

suggest further interventions and improvements. Some improvements can be adopted to

improve the quality of urine and the diet samples.

Abstract

It is known that little intake of sodium and high potassium intake is helpful in the control,

prevention, reduction of high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases that may occur later

in life. The aim of the survey was to put on trial samples of urine and to assess the diet from

children in order to understand the effects of sodium and potassium in Australian children

with ages between 8 to 11 years in one Australian primary school (1). A sample of 27

children was selected in a span of two weeks. All these children had their urine samples

picked (about 72%) and those who carried the interview checked their diet for a period of 24

hours to ascertain the percentage of sodium and potassium content in the food they take. The

range of sodium intake was 2192 (1086-4785) milligram per day which is equivalent to 5.4

grams of salt, the intake of potassium was 1775 which also translates to 800-2980 milligrams

per day. It was evident that the frequency of consumption of salt was minimal. However,

there are certain foods that are known to have a high content of sodium and potassium; they

include bread, pastry, dairy products and some non-alcoholic drinks (2). Interestingly, most

participants participated in the exercise and were seen to be enjoying the whole process. We

can suggest that a large survey can be done for the confirmation of the findings and to

suggest further interventions and improvements. Some improvements can be adopted to

improve the quality of urine and the diet samples.

3

Table of Contents

Introduction................................................................................................................................4

Research Methods......................................................................................................................5

2.1 The design of study..........................................................................................................5

2.2 Measures of outcome........................................................................................................5

2.3 Participants and their consent...........................................................................................5

2.4 Outcome measures and collection procedure...................................................................6

Results........................................................................................................................................8

3.1 Recruitments and retention...............................................................................................8

3.2 Demographic and participating children..........................................................................8

3.3 Accuracy of samples of Urine..........................................................................................9

3.4 Sodium and potassium intake...........................................................................................9

3.5 Sources of food with potassium and sodium..................................................................10

3.6 Blood pressure................................................................................................................10

3.7 Methods of collecting 24-hour urine samples and diet recalls.......................................10

3.8 The 24-hour Diet Recalls................................................................................................11

Discussion................................................................................................................................12

Conclusions..............................................................................................................................13

References................................................................................................................................15

Table of Contents

Introduction................................................................................................................................4

Research Methods......................................................................................................................5

2.1 The design of study..........................................................................................................5

2.2 Measures of outcome........................................................................................................5

2.3 Participants and their consent...........................................................................................5

2.4 Outcome measures and collection procedure...................................................................6

Results........................................................................................................................................8

3.1 Recruitments and retention...............................................................................................8

3.2 Demographic and participating children..........................................................................8

3.3 Accuracy of samples of Urine..........................................................................................9

3.4 Sodium and potassium intake...........................................................................................9

3.5 Sources of food with potassium and sodium..................................................................10

3.6 Blood pressure................................................................................................................10

3.7 Methods of collecting 24-hour urine samples and diet recalls.......................................10

3.8 The 24-hour Diet Recalls................................................................................................11

Discussion................................................................................................................................12

Conclusions..............................................................................................................................13

References................................................................................................................................15

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

Introduction

Nutritional research has proved that both sodium and potassium play an important role in the

determination of the blood pressure level in human beings. The same research shows that a

high level of sodium in diets contributes to a high number of disabilities in human life. In

fact, 74,000 people with disability are globally attributed to the high consumption of sodium

and potassium. These people are at a higher risk of having high blood pressure and

cardiovascular diseases. In Australia and any other developed countries, cardiovascular

disease is a major cause of health deterioration. Additionally, high consumption of sodium in

diets also causes stomach cancer and kidney disorders. In connection to this, modern research

shows that excess sodium may lead to the development of obesity in children. Therefore,

controlling the level and rate of consumption of sodium is helpful to public health.

In 2012, many countries, including Australia have committed themselves to the World Health

Organization’s recommendation on the reduction of the consumption of sodium. The WHO

has advised that the consumption of sodium should be reduced by thirty percent (30%) in

every 5grams or 2000 milligrams of sodium per day. It has been recorded that Australian

adults consume higher sodium than children. Those aged above 15 years are now consuming

3,300 milligrams of sodium per day. Children prefer eating a lot of sodium in their early ages

and they are likely to grow with that preference. However, several studies on healthy eating

have indicated that reduction of sodium consumption results to the reduction of blood

pressure. High blood pressure in childhood leads to a high blood pressure later in life which

is quite harmful for health. World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that children

should consume at most 2000 milligrams and 3510 milligrams of sodium and potassium

respectively per day (3). The molar ratio of potassium and sodium meant for children

consumption should be one.

Introduction

Nutritional research has proved that both sodium and potassium play an important role in the

determination of the blood pressure level in human beings. The same research shows that a

high level of sodium in diets contributes to a high number of disabilities in human life. In

fact, 74,000 people with disability are globally attributed to the high consumption of sodium

and potassium. These people are at a higher risk of having high blood pressure and

cardiovascular diseases. In Australia and any other developed countries, cardiovascular

disease is a major cause of health deterioration. Additionally, high consumption of sodium in

diets also causes stomach cancer and kidney disorders. In connection to this, modern research

shows that excess sodium may lead to the development of obesity in children. Therefore,

controlling the level and rate of consumption of sodium is helpful to public health.

In 2012, many countries, including Australia have committed themselves to the World Health

Organization’s recommendation on the reduction of the consumption of sodium. The WHO

has advised that the consumption of sodium should be reduced by thirty percent (30%) in

every 5grams or 2000 milligrams of sodium per day. It has been recorded that Australian

adults consume higher sodium than children. Those aged above 15 years are now consuming

3,300 milligrams of sodium per day. Children prefer eating a lot of sodium in their early ages

and they are likely to grow with that preference. However, several studies on healthy eating

have indicated that reduction of sodium consumption results to the reduction of blood

pressure. High blood pressure in childhood leads to a high blood pressure later in life which

is quite harmful for health. World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that children

should consume at most 2000 milligrams and 3510 milligrams of sodium and potassium

respectively per day (3). The molar ratio of potassium and sodium meant for children

consumption should be one.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

However, we realized certain problems while collecting information on sodium and

potassium intakes. One of the problems is the traditional dietary behavior for many families

in Australia. Many people have their own ways of preparing food either using a lot of sodium

and potassium or little of the latter.

Research Methods

2.1 The design of the study

This was a pilot study that cut across the lifestyle of many people in Australia. The methods

that were applied were results found after testing salts and other nutrients from samples.

2.2 Measures of outcome

It was important to observe the recruitment and the retention rates of the samples of urine that

was used to provide the sodium samples. The samples were also derived from major sources

of food which had the presence of sodium and potassium in them. Similarly, some levels of

sodium or potassium could be obtained from adding small portions of salt or potassium in

cooked meals for feasibility studies, and consequently helped in the collection of 24-h

samples of urine and recalls of diet.

2.3 Participants and their consent

Since this study was for trial purposes, the sample size was not considered a formal one by

having an appropriate calculation. There were some factors that hindered us from carrying an

adequate and effective exercise. These include inadequate time, lack, of funds, and capacity.

The aim was to do a survey among 30 children based on the estimation of 24-h urine samples

resulting in a total of 24 samples. This was also estimated to be approximately 90% sample

rate that was adequate for analysis. In the exercise, children within the age bracket of 8-11

were interviewed because they were fluent in English. It is believed that Australian children

However, we realized certain problems while collecting information on sodium and

potassium intakes. One of the problems is the traditional dietary behavior for many families

in Australia. Many people have their own ways of preparing food either using a lot of sodium

and potassium or little of the latter.

Research Methods

2.1 The design of the study

This was a pilot study that cut across the lifestyle of many people in Australia. The methods

that were applied were results found after testing salts and other nutrients from samples.

2.2 Measures of outcome

It was important to observe the recruitment and the retention rates of the samples of urine that

was used to provide the sodium samples. The samples were also derived from major sources

of food which had the presence of sodium and potassium in them. Similarly, some levels of

sodium or potassium could be obtained from adding small portions of salt or potassium in

cooked meals for feasibility studies, and consequently helped in the collection of 24-h

samples of urine and recalls of diet.

2.3 Participants and their consent

Since this study was for trial purposes, the sample size was not considered a formal one by

having an appropriate calculation. There were some factors that hindered us from carrying an

adequate and effective exercise. These include inadequate time, lack, of funds, and capacity.

The aim was to do a survey among 30 children based on the estimation of 24-h urine samples

resulting in a total of 24 samples. This was also estimated to be approximately 90% sample

rate that was adequate for analysis. In the exercise, children within the age bracket of 8-11

were interviewed because they were fluent in English. It is believed that Australian children

6

in this age bracket may have exceeded the guidelines for sodium intakes (4). At least one

child from the sampled family took part in the exercise. The plan was also to recruit children

from three classes in a diverse educational facility in the selected region. The data from the

ministry of education was used to help in the identification of an appropriate school with the

required population of children that would help achieving the required number of respondents

and participants to be used in the survey. The selected schools were contacted one by one via

e-mails to confirm their interests in participation. After this, a school was selected to

participate in the survey (5). It was our responsibility to carry out adequate briefing sessions

with the assistance of school management in order to make them aware of the intention of the

survey, procedures, and the guidelines to be followed during the exercise. Precisely, the

management and the teachers had to know the intent of such exercise and their roles in

making the exercise successful. Finally, there was a joint briefing session that included

children, teachers, and school management was held where the procedures and the roles of

each person were explained. Invitation letters were given to the selected children to take to

their parents informing them of their participation in the exercise. Information about the

survey was also put in the school's other information boards such as school newsletter and

facebook page.

2.4 Outcome measures and collection procedure

The rates of retention and recruitment were done according to the study journals on the

selected schools and the number of respondents who gave adequate information about the

survey. Information on demographic features was gotten from an online survey using

software that incorporated the income for every household, ethnic affiliation of the child, age,

gender, any medical condition, and dietary requirements. The 24-hour collection of urine was

conducted considering the procedures and guidelines recommended by the World Health

Organization (WHO) but this depended on the agreement of the parent or guardian; could be

in this age bracket may have exceeded the guidelines for sodium intakes (4). At least one

child from the sampled family took part in the exercise. The plan was also to recruit children

from three classes in a diverse educational facility in the selected region. The data from the

ministry of education was used to help in the identification of an appropriate school with the

required population of children that would help achieving the required number of respondents

and participants to be used in the survey. The selected schools were contacted one by one via

e-mails to confirm their interests in participation. After this, a school was selected to

participate in the survey (5). It was our responsibility to carry out adequate briefing sessions

with the assistance of school management in order to make them aware of the intention of the

survey, procedures, and the guidelines to be followed during the exercise. Precisely, the

management and the teachers had to know the intent of such exercise and their roles in

making the exercise successful. Finally, there was a joint briefing session that included

children, teachers, and school management was held where the procedures and the roles of

each person were explained. Invitation letters were given to the selected children to take to

their parents informing them of their participation in the exercise. Information about the

survey was also put in the school's other information boards such as school newsletter and

facebook page.

2.4 Outcome measures and collection procedure

The rates of retention and recruitment were done according to the study journals on the

selected schools and the number of respondents who gave adequate information about the

survey. Information on demographic features was gotten from an online survey using

software that incorporated the income for every household, ethnic affiliation of the child, age,

gender, any medical condition, and dietary requirements. The 24-hour collection of urine was

conducted considering the procedures and guidelines recommended by the World Health

Organization (WHO) but this depended on the agreement of the parent or guardian; could be

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

collected on a weekend or any other appropriate day (6). The collected samples were put in

transparent plastic bags which were properly sealed and labeled. The total volume of the

urine sample was recorded and about 2*10ml was prepared and kept at -3 degrees-Celsius.

The analysis of these samples was done in accredited university laboratory by using Hitachi

Cobas C311 analyzer and ion electrodes. In case the sample of urine collected was not done

exactly within the 24-hour duration, perhaps within 20-28 hour duration, standardization

could be done to reduce urinary sodium or potassium to 24-hour duration. The 24-hour urine

samples collected could be assessed by approximately more than 300 milliliters within the

collection duration of 20-28 hour. However, participants could report some few missed

collection of urine which was approximately slightly more than 0.1 molar moles per kilogram

body weight per day (7).

The calculation of sodium and potassium was done by the use of 24-hour urine collection

data and used as the medium range. Because the sample data was small and somehow

skewed, we decided to calculate the medians for all the samples of urine separately. The

twenty-four-hour diet analysis was done by a professional research analyst during or after

school times and using the Australian version of the interactive online 24-hour software. This

is a recommended software program that incorporates unique features for analysis of urine

samples and diet recall samples. It saves the time of analysis besides giving rather accurate

results of the analysis. However, being the first time using this software in children, it was

necessary to carry out some interviews by face-to-face technique and parents given the

opportunity to enter their own data with the aid of a professional researcher (8). It was also

important to confirm from the participants if they added salt to food or recipe they used. The

24-hour Intake software allows for an additional 0.25 teaspoons of salt to be added.

The food sources that are known to be having sodium and potassium in them were assessed

using the Intake24 hour software. It was also important to construct some three questions to

collected on a weekend or any other appropriate day (6). The collected samples were put in

transparent plastic bags which were properly sealed and labeled. The total volume of the

urine sample was recorded and about 2*10ml was prepared and kept at -3 degrees-Celsius.

The analysis of these samples was done in accredited university laboratory by using Hitachi

Cobas C311 analyzer and ion electrodes. In case the sample of urine collected was not done

exactly within the 24-hour duration, perhaps within 20-28 hour duration, standardization

could be done to reduce urinary sodium or potassium to 24-hour duration. The 24-hour urine

samples collected could be assessed by approximately more than 300 milliliters within the

collection duration of 20-28 hour. However, participants could report some few missed

collection of urine which was approximately slightly more than 0.1 molar moles per kilogram

body weight per day (7).

The calculation of sodium and potassium was done by the use of 24-hour urine collection

data and used as the medium range. Because the sample data was small and somehow

skewed, we decided to calculate the medians for all the samples of urine separately. The

twenty-four-hour diet analysis was done by a professional research analyst during or after

school times and using the Australian version of the interactive online 24-hour software. This

is a recommended software program that incorporates unique features for analysis of urine

samples and diet recall samples. It saves the time of analysis besides giving rather accurate

results of the analysis. However, being the first time using this software in children, it was

necessary to carry out some interviews by face-to-face technique and parents given the

opportunity to enter their own data with the aid of a professional researcher (8). It was also

important to confirm from the participants if they added salt to food or recipe they used. The

24-hour Intake software allows for an additional 0.25 teaspoons of salt to be added.

The food sources that are known to be having sodium and potassium in them were assessed

using the Intake24 hour software. It was also important to construct some three questions to

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

seek the answers on the use of salt among Australian children. They include: Do you usually

provide salt shakers on the table during meal times? Do you add salt in food while cooking?

or does your child add salt in the food during mealtime? The participants were then given

answers in choices such as Yes, Sometimes, No and don’t know.

Results

3.1 Recruitments and retention

The recruitment of schools and children that were supposed to participate in the exercise was

carried out in the months of August and November 2017. Four schools were selected to

participate in the study with the third school accepting to wholly be involved in the said

exercise. Approximately thirty consent forms were returned within two weeks after their

dispatch for 117 children. This was 24% of the response. It was realized that one child

dropped out of school before she gave out her information and neither the parents nor

guardians turned up to give the information that she ought to have given (9). Some children

were also withdrawn from the survey because they could never understand nor write English.

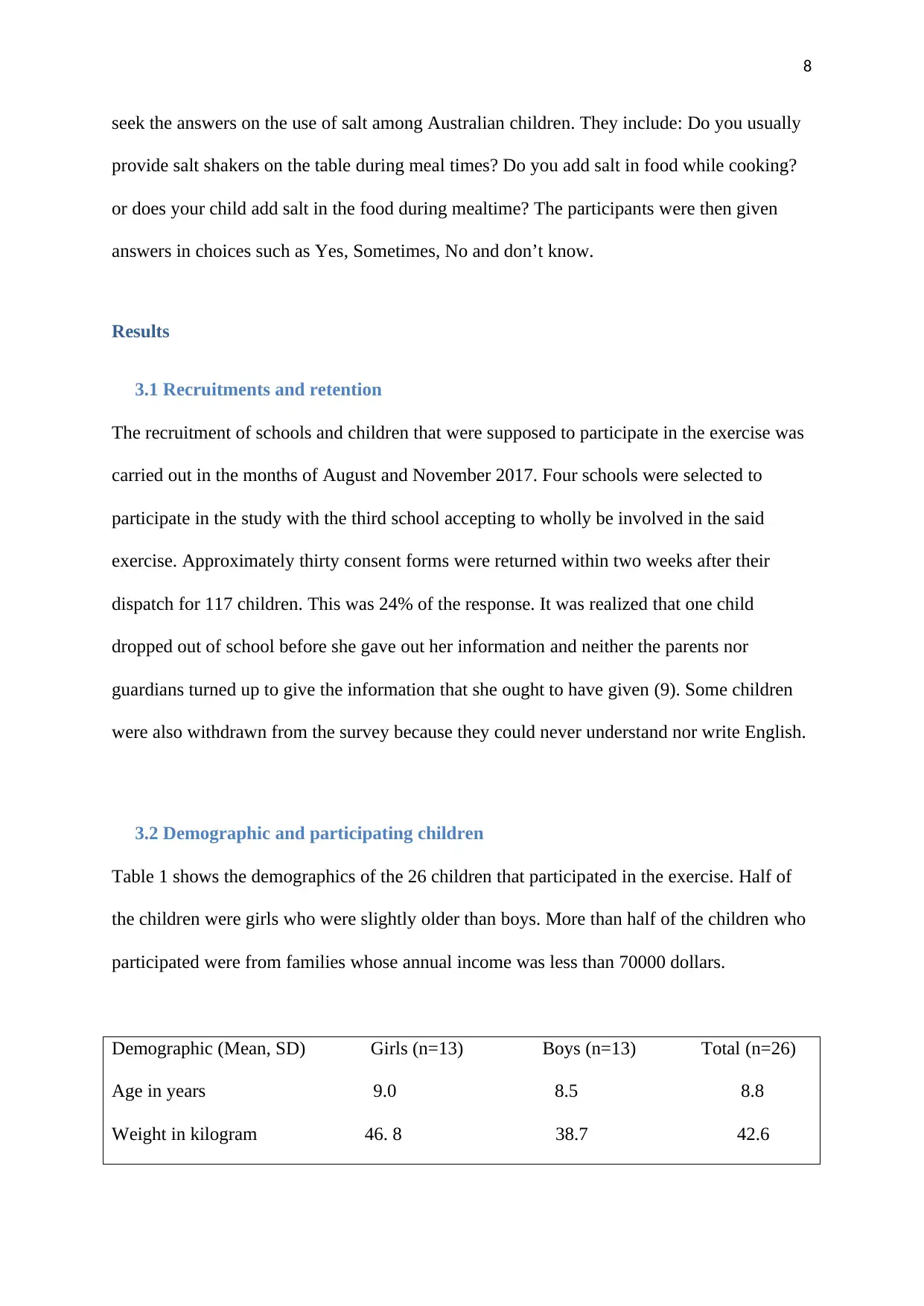

3.2 Demographic and participating children

Table 1 shows the demographics of the 26 children that participated in the exercise. Half of

the children were girls who were slightly older than boys. More than half of the children who

participated were from families whose annual income was less than 70000 dollars.

Demographic (Mean, SD) Girls (n=13) Boys (n=13) Total (n=26)

Age in years 9.0 8.5 8.8

Weight in kilogram 46. 8 38.7 42.6

seek the answers on the use of salt among Australian children. They include: Do you usually

provide salt shakers on the table during meal times? Do you add salt in food while cooking?

or does your child add salt in the food during mealtime? The participants were then given

answers in choices such as Yes, Sometimes, No and don’t know.

Results

3.1 Recruitments and retention

The recruitment of schools and children that were supposed to participate in the exercise was

carried out in the months of August and November 2017. Four schools were selected to

participate in the study with the third school accepting to wholly be involved in the said

exercise. Approximately thirty consent forms were returned within two weeks after their

dispatch for 117 children. This was 24% of the response. It was realized that one child

dropped out of school before she gave out her information and neither the parents nor

guardians turned up to give the information that she ought to have given (9). Some children

were also withdrawn from the survey because they could never understand nor write English.

3.2 Demographic and participating children

Table 1 shows the demographics of the 26 children that participated in the exercise. Half of

the children were girls who were slightly older than boys. More than half of the children who

participated were from families whose annual income was less than 70000 dollars.

Demographic (Mean, SD) Girls (n=13) Boys (n=13) Total (n=26)

Age in years 9.0 8.5 8.8

Weight in kilogram 46. 8 38.7 42.6

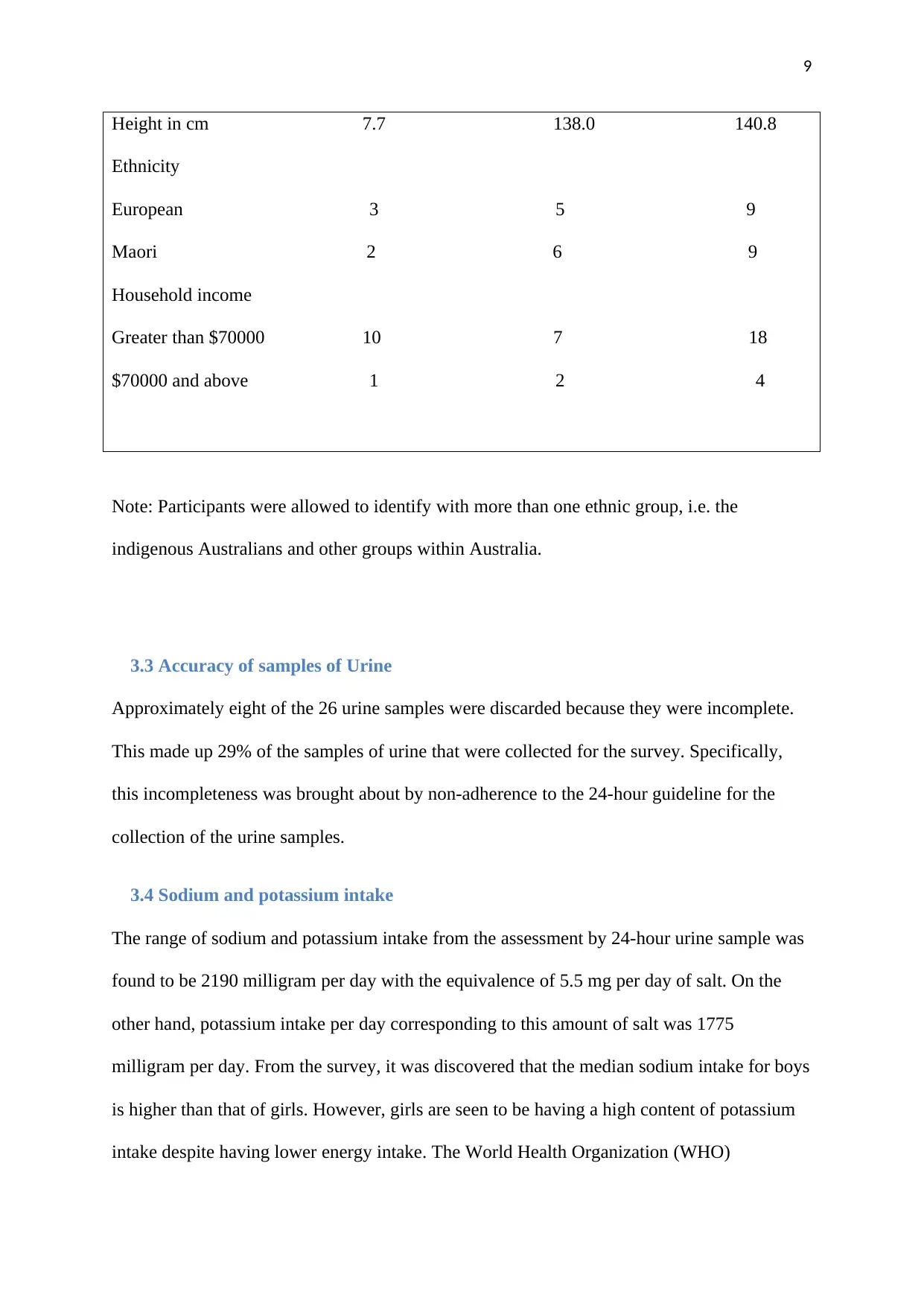

9

Height in cm 7.7 138.0 140.8

Ethnicity

European 3 5 9

Maori 2 6 9

Household income

Greater than $70000 10 7 18

$70000 and above 1 2 4

Note: Participants were allowed to identify with more than one ethnic group, i.e. the

indigenous Australians and other groups within Australia.

3.3 Accuracy of samples of Urine

Approximately eight of the 26 urine samples were discarded because they were incomplete.

This made up 29% of the samples of urine that were collected for the survey. Specifically,

this incompleteness was brought about by non-adherence to the 24-hour guideline for the

collection of the urine samples.

3.4 Sodium and potassium intake

The range of sodium and potassium intake from the assessment by 24-hour urine sample was

found to be 2190 milligram per day with the equivalence of 5.5 mg per day of salt. On the

other hand, potassium intake per day corresponding to this amount of salt was 1775

milligram per day. From the survey, it was discovered that the median sodium intake for boys

is higher than that of girls. However, girls are seen to be having a high content of potassium

intake despite having lower energy intake. The World Health Organization (WHO)

Height in cm 7.7 138.0 140.8

Ethnicity

European 3 5 9

Maori 2 6 9

Household income

Greater than $70000 10 7 18

$70000 and above 1 2 4

Note: Participants were allowed to identify with more than one ethnic group, i.e. the

indigenous Australians and other groups within Australia.

3.3 Accuracy of samples of Urine

Approximately eight of the 26 urine samples were discarded because they were incomplete.

This made up 29% of the samples of urine that were collected for the survey. Specifically,

this incompleteness was brought about by non-adherence to the 24-hour guideline for the

collection of the urine samples.

3.4 Sodium and potassium intake

The range of sodium and potassium intake from the assessment by 24-hour urine sample was

found to be 2190 milligram per day with the equivalence of 5.5 mg per day of salt. On the

other hand, potassium intake per day corresponding to this amount of salt was 1775

milligram per day. From the survey, it was discovered that the median sodium intake for boys

is higher than that of girls. However, girls are seen to be having a high content of potassium

intake despite having lower energy intake. The World Health Organization (WHO)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

recommends that children within the age bracket of 9-13 years should consume 2000mg or

5grams of salt per day (10). It was also realized that the sodium to potassium molar ratio was

at least higher than that recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) which

should be aproximately1.1 to 4.8. Additionally, this molar ratio is also higher in boys than

girls. All children that were sampled to participate in the survey yielded a molar ratio of

potassium to sodium of more than1.0.

3.5 Sources of food with potassium and sodium

The survey records that the major source of salt is the bread which contains about 15.1% of

salt. Other contributors include pastries, sauces, meat and poultry, snacks etc. These

contribute less than 5% of sodium intake (11). However, the main contributor of potassium

was found to be dairy products with 23.1% followed by meat and poultry products, fruits, and

non-starchy vegetables which contribute to approximately less than 5% of the potassium

intake.

3.6 Blood pressure

The range of blood pressure for the 26 sampled children surveyed was 104 mmHg. This

corresponds to that for 13 sampled boys with systolic blood pressure being approximately

104 mmHg. This indicated that both genders had equal chances of having high blood pressure

(BP) when they have consumed more than the recommended sodium or potassium in their

daily diet.

3.7 Methods of collecting 24-hour urine samples and diet recalls

Most children that were selected to participate in the exercise were required to produce their

samples on a weekday. It was again important to supervise the collection of data after a

careful communication by and to the participants i.e. the children, their parents, teachers, and

the management of the school that was selected to participate in the process (12). In the

recommends that children within the age bracket of 9-13 years should consume 2000mg or

5grams of salt per day (10). It was also realized that the sodium to potassium molar ratio was

at least higher than that recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) which

should be aproximately1.1 to 4.8. Additionally, this molar ratio is also higher in boys than

girls. All children that were sampled to participate in the survey yielded a molar ratio of

potassium to sodium of more than1.0.

3.5 Sources of food with potassium and sodium

The survey records that the major source of salt is the bread which contains about 15.1% of

salt. Other contributors include pastries, sauces, meat and poultry, snacks etc. These

contribute less than 5% of sodium intake (11). However, the main contributor of potassium

was found to be dairy products with 23.1% followed by meat and poultry products, fruits, and

non-starchy vegetables which contribute to approximately less than 5% of the potassium

intake.

3.6 Blood pressure

The range of blood pressure for the 26 sampled children surveyed was 104 mmHg. This

corresponds to that for 13 sampled boys with systolic blood pressure being approximately

104 mmHg. This indicated that both genders had equal chances of having high blood pressure

(BP) when they have consumed more than the recommended sodium or potassium in their

daily diet.

3.7 Methods of collecting 24-hour urine samples and diet recalls

Most children that were selected to participate in the exercise were required to produce their

samples on a weekday. It was again important to supervise the collection of data after a

careful communication by and to the participants i.e. the children, their parents, teachers, and

the management of the school that was selected to participate in the process (12). In the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

identification of the methods to be used, cultural aspects were also looked at. Generally,

certain children could be able to collect their own samples of urine and they could enjoy

taking part in the exercise as well (13). This enabled the process to be quickly accomplished

and also improved the accuracy of the samples collected. Teachers had a feeling that this

study was aligned with the topics that they teach in schools such as the wellbeing, family

affairs, and science. However, there were mixed reactions about how the students and parents

understood the whole process of the study (14). It was evident that the method of

communication which was mainly through e-mail could have not served the intended purpose

effectively. This forced the organizers to revert to sending text messages to parents and

guardians rather than e-mails. Additionally, it was not clear to parents what to do with the

urine samples collected, where to return them and how to preserve them. Similarly, some

children shied away from discussing urine collection, in a nutshell, they felt somehow

uncomfortable from sharing information about the collection of their urine samples (15).

Therefore, it was also important to recognize the safety of urine stored after the collection.

This could be given in clear instructions to parents or guardians.

3.8 The 24-hour Diet Recalls

It was important to note that all the 24-hour diet recall was accomplished just at the same

time with the 24-hour period urine collection. Approximately, the average for diet recalls

took 33.8 minutes to accomplish. Out of the 427 types of foods and beverages took by the

children that participated in the exercise, 232 i.e. 53% had their sodium data with new

specific values of 2017 nutritrack values. Many parents and guardians reported the benefits of

the 24-hour Intake software as positive and helped them in recording and remembering the

foods and beverages efficiently (16). A few participants reported that they had difficulties in

using the system. Some of them say the system was confusing to use because it had many

features that make it difficult to use. All parents admitted that face-to-face interaction was

identification of the methods to be used, cultural aspects were also looked at. Generally,

certain children could be able to collect their own samples of urine and they could enjoy

taking part in the exercise as well (13). This enabled the process to be quickly accomplished

and also improved the accuracy of the samples collected. Teachers had a feeling that this

study was aligned with the topics that they teach in schools such as the wellbeing, family

affairs, and science. However, there were mixed reactions about how the students and parents

understood the whole process of the study (14). It was evident that the method of

communication which was mainly through e-mail could have not served the intended purpose

effectively. This forced the organizers to revert to sending text messages to parents and

guardians rather than e-mails. Additionally, it was not clear to parents what to do with the

urine samples collected, where to return them and how to preserve them. Similarly, some

children shied away from discussing urine collection, in a nutshell, they felt somehow

uncomfortable from sharing information about the collection of their urine samples (15).

Therefore, it was also important to recognize the safety of urine stored after the collection.

This could be given in clear instructions to parents or guardians.

3.8 The 24-hour Diet Recalls

It was important to note that all the 24-hour diet recall was accomplished just at the same

time with the 24-hour period urine collection. Approximately, the average for diet recalls

took 33.8 minutes to accomplish. Out of the 427 types of foods and beverages took by the

children that participated in the exercise, 232 i.e. 53% had their sodium data with new

specific values of 2017 nutritrack values. Many parents and guardians reported the benefits of

the 24-hour Intake software as positive and helped them in recording and remembering the

foods and beverages efficiently (16). A few participants reported that they had difficulties in

using the system. Some of them say the system was confusing to use because it had many

features that make it difficult to use. All parents admitted that face-to-face interaction was

12

effective in giving instructions to participants and created a mutual relationship between the

respondents and the interviewers (17). Four parents suggested that to have an effective

collection of samples of food intake in future, the collection should be done away from

special holidays and to ensure that children understand the language being applied or the one

used in the presentation of research questions.

Discussion

We were successful in recruiting and retaining a diverse sample of children (n=26) whose

ages were between 8 and 11years from the Australian primary school for the case study. The

urine sample 24-hour diet collection was done within one term. It was again important to

supervise the collection of data after a careful communication by and to the participants i.e.

the children, their parents, teachers, and the management of the school that was selected to

participate in the process (18). In the identification of the methods to be used, cultural aspects

were also looked at. Generally, certain children could be able to collect their own samples of

urine and they could enjoy taking part in the exercise as well (19). This enabled the process to

be quickly accomplished and also improved the accuracy of the samples collected. Teachers

had a feeling that this study was aligned with the topics that they teach in schools such as the

wellbeing, family affairs, and science (19). However, there were mixed reactions about how

the students and parents understood the whole process of the study. It was evident that the

method of communication which was mainly through e-mail could have not served the

intended purpose effectively. This forced the organizers to revert to sending text messages to

parents and guardians rather than e-mails. Additionally, it was not clear to parents what to do

with the urine samples collected, where to return them and how to preserve them (20).

effective in giving instructions to participants and created a mutual relationship between the

respondents and the interviewers (17). Four parents suggested that to have an effective

collection of samples of food intake in future, the collection should be done away from

special holidays and to ensure that children understand the language being applied or the one

used in the presentation of research questions.

Discussion

We were successful in recruiting and retaining a diverse sample of children (n=26) whose

ages were between 8 and 11years from the Australian primary school for the case study. The

urine sample 24-hour diet collection was done within one term. It was again important to

supervise the collection of data after a careful communication by and to the participants i.e.

the children, their parents, teachers, and the management of the school that was selected to

participate in the process (18). In the identification of the methods to be used, cultural aspects

were also looked at. Generally, certain children could be able to collect their own samples of

urine and they could enjoy taking part in the exercise as well (19). This enabled the process to

be quickly accomplished and also improved the accuracy of the samples collected. Teachers

had a feeling that this study was aligned with the topics that they teach in schools such as the

wellbeing, family affairs, and science (19). However, there were mixed reactions about how

the students and parents understood the whole process of the study. It was evident that the

method of communication which was mainly through e-mail could have not served the

intended purpose effectively. This forced the organizers to revert to sending text messages to

parents and guardians rather than e-mails. Additionally, it was not clear to parents what to do

with the urine samples collected, where to return them and how to preserve them (20).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 16

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.