Inclusive Education: Frameworks, History, and Global Impact Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/03/31

|39

|14520

|392

Essay

AI Summary

This essay provides a comprehensive overview of inclusive education, differentiating it from special education and emphasizing its core principle of enabling all children to learn together by acknowledging diversities in ability, culture, gender, and more. It highlights the significance of Article 24 of the CRPD in advocating for quality education for all students, focusing on removing barriers to access and participation. The essay references Ainscow and Miles' framework for inclusive education, emphasizing its applicability in various national contexts, including Bhutan, where inclusive education is a recent development. It also discusses the historical evolution of inclusive education, from the special education model to the social model of disability, and the influence of international conventions and statements like the Salamanca Statement and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in shaping global education policies. The essay concludes by highlighting the importance of understanding the historical development of inclusive education to address current challenges effectively.

2.1 Inclusive education

The definition of inclusive education provided in Chapter 1, section 1.5 provides a clear

understanding of the difference between inclusive education and special education. Booth and

Ainscow's (2011) argument states that inclusive education works towards accepting and

placing children with disabilities in regular classrooms with non-disabled peers when

necessary adjustments and appropriate modifications support learning in all students. The

following section will now examine closely how inclusive education facilitates the education

of all children harmoniously.

The basic premise of inclusive education is for all children to learn together. The focus

is on acknowledging the diversities that exist in ability, culture, gender, language, class and

ethnicity (Carrington, MacArthur, Kearney, Kimber, Mercer & Morton, 2012; UNESCO,

1994, 2016). With Article 24, Comment 4 of the CRPD providing the most authoritative

articulation of the human right of persons with disabilities to inclusive education, it is widely

accepted that inclusive education now encompasses the delivery of a quality education to all

students; not only to students with a disability but focusing on barriers to student access and

participation, and not just physical barriers (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Graham, 2013,

Graham &Jahnukainen, 2011). Further, inclusion, in the Index of Inclusion by Ainscow, is a

principled approach to developing education, as it focuses on cultures, policies and practices

that affect everyone: children and adults, schools, families and communities (Booth,

Ainscow& Kingston, 2006). Therefore, apart from including children from all races,

disadvantaged groups and all cultures, inclusive education also recognizes that learning

occurs both at home and in the community and hence the support of parents, family and the

community is important.

The inclusive education approach began in the United States in the late 1980s and “was

started principally by advocates for learners with severe disabilities, who were not an

essential part of the regular education initiative” (Power-Defur&Orelove, 1997, p.3). In this

approach the focus was mainly placed on moving students with severe disabilities from

segregated schools to integrated environments. As the approach gained significant

momentum, the efforts became increasingly focused on educating children with disabilities in

mainstream classrooms — eventually known as inclusive education.

Inclusive education is where all students learn together irrespective of any difficulties

or differences they may have.Ainscow and Miles (2009, p.2) argued that inclusive education

1

The definition of inclusive education provided in Chapter 1, section 1.5 provides a clear

understanding of the difference between inclusive education and special education. Booth and

Ainscow's (2011) argument states that inclusive education works towards accepting and

placing children with disabilities in regular classrooms with non-disabled peers when

necessary adjustments and appropriate modifications support learning in all students. The

following section will now examine closely how inclusive education facilitates the education

of all children harmoniously.

The basic premise of inclusive education is for all children to learn together. The focus

is on acknowledging the diversities that exist in ability, culture, gender, language, class and

ethnicity (Carrington, MacArthur, Kearney, Kimber, Mercer & Morton, 2012; UNESCO,

1994, 2016). With Article 24, Comment 4 of the CRPD providing the most authoritative

articulation of the human right of persons with disabilities to inclusive education, it is widely

accepted that inclusive education now encompasses the delivery of a quality education to all

students; not only to students with a disability but focusing on barriers to student access and

participation, and not just physical barriers (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Graham, 2013,

Graham &Jahnukainen, 2011). Further, inclusion, in the Index of Inclusion by Ainscow, is a

principled approach to developing education, as it focuses on cultures, policies and practices

that affect everyone: children and adults, schools, families and communities (Booth,

Ainscow& Kingston, 2006). Therefore, apart from including children from all races,

disadvantaged groups and all cultures, inclusive education also recognizes that learning

occurs both at home and in the community and hence the support of parents, family and the

community is important.

The inclusive education approach began in the United States in the late 1980s and “was

started principally by advocates for learners with severe disabilities, who were not an

essential part of the regular education initiative” (Power-Defur&Orelove, 1997, p.3). In this

approach the focus was mainly placed on moving students with severe disabilities from

segregated schools to integrated environments. As the approach gained significant

momentum, the efforts became increasingly focused on educating children with disabilities in

mainstream classrooms — eventually known as inclusive education.

Inclusive education is where all students learn together irrespective of any difficulties

or differences they may have.Ainscow and Miles (2009, p.2) argued that inclusive education

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

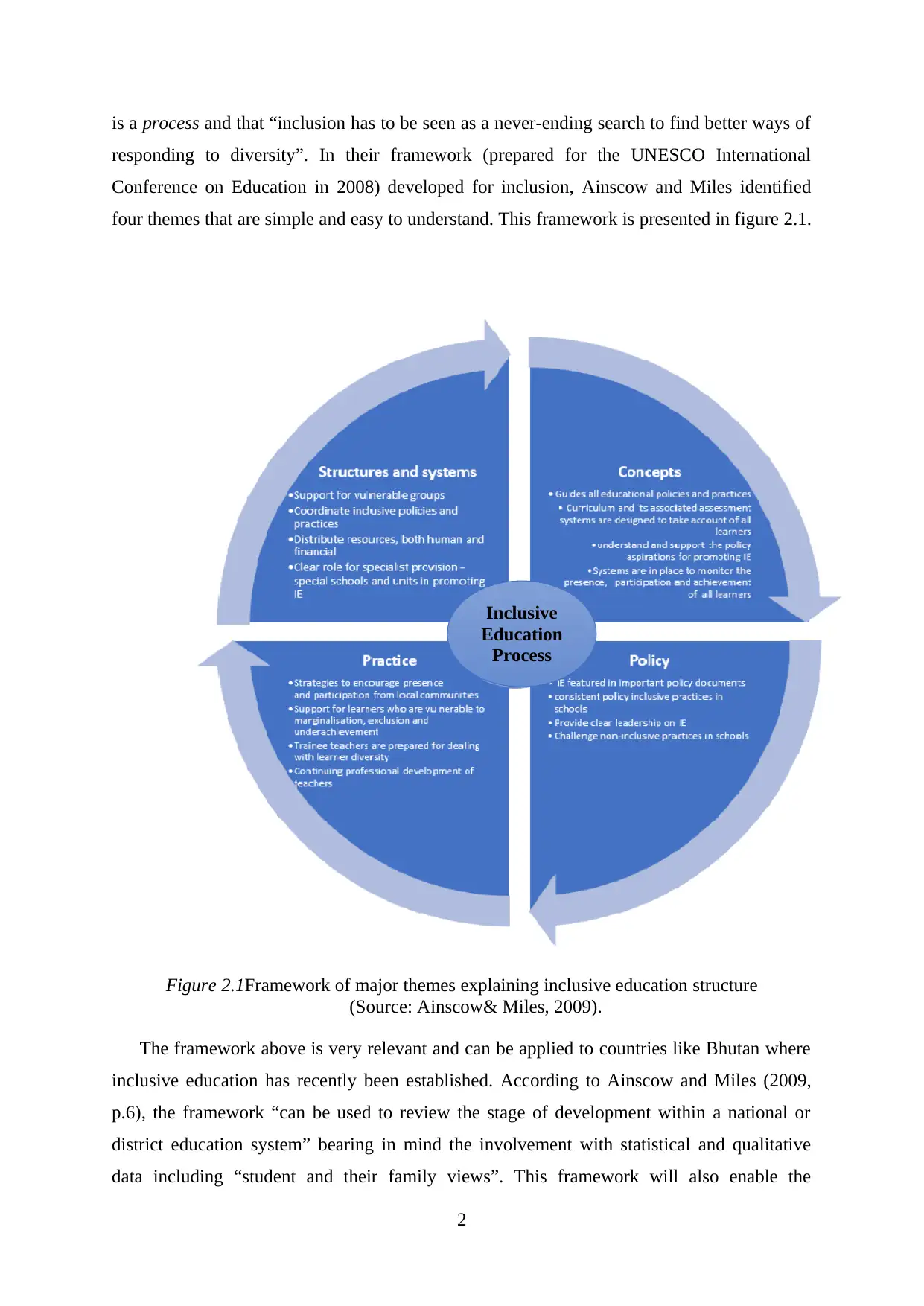

is a process and that “inclusion has to be seen as a never-ending search to find better ways of

responding to diversity”. In their framework (prepared for the UNESCO International

Conference on Education in 2008) developed for inclusion, Ainscow and Miles identified

four themes that are simple and easy to understand. This framework is presented in figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1Framework of major themes explaining inclusive education structure

(Source: Ainscow& Miles, 2009).

The framework above is very relevant and can be applied to countries like Bhutan where

inclusive education has recently been established. According to Ainscow and Miles (2009,

p.6), the framework “can be used to review the stage of development within a national or

district education system” bearing in mind the involvement with statistical and qualitative

data including “student and their family views”. This framework will also enable the

2

Inclusive

Education

Process

responding to diversity”. In their framework (prepared for the UNESCO International

Conference on Education in 2008) developed for inclusion, Ainscow and Miles identified

four themes that are simple and easy to understand. This framework is presented in figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1Framework of major themes explaining inclusive education structure

(Source: Ainscow& Miles, 2009).

The framework above is very relevant and can be applied to countries like Bhutan where

inclusive education has recently been established. According to Ainscow and Miles (2009,

p.6), the framework “can be used to review the stage of development within a national or

district education system” bearing in mind the involvement with statistical and qualitative

data including “student and their family views”. This framework will also enable the

2

Inclusive

Education

Process

development of plans for inclusive education to follow a process in moving policy and

practice forward. Inclusive schools will therefore be recognized and prioritized. As a result,

this will allow them to respond to the diverse needs of their students (Carrington & Elkins,

2002), accommodate different learning styles (Broderick, Mehta-Parekh & Reid, 2005; Duke,

2014), and ensure quality education for everyone through proper support such as:

appropriate/adapted curricula (Ainscow, Mara & Mara, 2012), organizational arrangements

and teaching strategies (Mills, 2013), use of teaching and learning resources and partnerships

with their parents and communities (Ainscow, 2005; Ballard, 2011; Loreman, Deppeler&

Harvey, 2011).

When discussing inclusive education in the Bhutanese context, it may be reiterated that

inclusive education means the inclusion of children with SEN and disabilities with their peers

without SEN in regular classrooms except for teaching children with visual impairment and

hearing impairment that are done in special schools (Dorji, 2015; MOE, 2011-2018; P.

Chhogyel1, personal communication, March 22, 2019). The Bhutan MOE has successfully

established 18 inclusive schools across the country, considering the benefits of inclusive

education, such as improved learning, better academic achievement, improved social and

communication through student involvement, and its cost-effectiveness in the long run

(Loreman, 2010). There are ongoing efforts to make the education system more inclusive,

based on the principles of GNH philosophy (Dorji, 2015). However, there are issues related

to inclusive education in Bhutan that are widely viewed as 1) barriers-lack of human resource

and infrastructure resources, lack of budget, 2) teacher preparation 3) inclusive attitudes and

4) lack of coordination in the implementation of inclusive education (Dorji, 2015; Dukpa,

2014; Jigyel, Miller, Mavropoulou& Berman, 2018; Kamenopoulou&Dukpa, 2018; MOE,

2016; Subba, Yangzom, Dorji, Choden, Namgay, Carrington & Nickerson, 2018). This study

has therefore closely examined data related to these issues and these are discussed and

explained in Chapters 4, 5 and 6 respectively.

2.1.1 The advent of inclusive education

The special education model moved towards the end of the twentieth century to the

concept of inclusive education that parallels the emergence of social models of disability. The

inclusive education model aimed at addressing oppression and discrimination of people with

disabilities resulting from institutional forms of “exclusion and cultural attitudes” embodied

1P. Chhogyel is the Deputy Chief Program Officer of the Special Education Section at the Ministry of Education

in Bhutan who provided ‘special education and inclusive education’ information to the researcher.

3

practice forward. Inclusive schools will therefore be recognized and prioritized. As a result,

this will allow them to respond to the diverse needs of their students (Carrington & Elkins,

2002), accommodate different learning styles (Broderick, Mehta-Parekh & Reid, 2005; Duke,

2014), and ensure quality education for everyone through proper support such as:

appropriate/adapted curricula (Ainscow, Mara & Mara, 2012), organizational arrangements

and teaching strategies (Mills, 2013), use of teaching and learning resources and partnerships

with their parents and communities (Ainscow, 2005; Ballard, 2011; Loreman, Deppeler&

Harvey, 2011).

When discussing inclusive education in the Bhutanese context, it may be reiterated that

inclusive education means the inclusion of children with SEN and disabilities with their peers

without SEN in regular classrooms except for teaching children with visual impairment and

hearing impairment that are done in special schools (Dorji, 2015; MOE, 2011-2018; P.

Chhogyel1, personal communication, March 22, 2019). The Bhutan MOE has successfully

established 18 inclusive schools across the country, considering the benefits of inclusive

education, such as improved learning, better academic achievement, improved social and

communication through student involvement, and its cost-effectiveness in the long run

(Loreman, 2010). There are ongoing efforts to make the education system more inclusive,

based on the principles of GNH philosophy (Dorji, 2015). However, there are issues related

to inclusive education in Bhutan that are widely viewed as 1) barriers-lack of human resource

and infrastructure resources, lack of budget, 2) teacher preparation 3) inclusive attitudes and

4) lack of coordination in the implementation of inclusive education (Dorji, 2015; Dukpa,

2014; Jigyel, Miller, Mavropoulou& Berman, 2018; Kamenopoulou&Dukpa, 2018; MOE,

2016; Subba, Yangzom, Dorji, Choden, Namgay, Carrington & Nickerson, 2018). This study

has therefore closely examined data related to these issues and these are discussed and

explained in Chapters 4, 5 and 6 respectively.

2.1.1 The advent of inclusive education

The special education model moved towards the end of the twentieth century to the

concept of inclusive education that parallels the emergence of social models of disability. The

inclusive education model aimed at addressing oppression and discrimination of people with

disabilities resulting from institutional forms of “exclusion and cultural attitudes” embodied

1P. Chhogyel is the Deputy Chief Program Officer of the Special Education Section at the Ministry of Education

in Bhutan who provided ‘special education and inclusive education’ information to the researcher.

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

in social practices (Dorji, 2015, p.4). Inclusive education came for everyone (all) worldwide

due to numerous social movements and international conventions and statements about

education. In section 2.2.4 – History and development of special education, these movements,

conventions and statements were discussed. Therefore, to respond appropriately to the

challenges in an inclusive system, understanding the historical development of inclusive

education at the international and national level is important. Table 2.2 presents a timeline of

important international conventions and statements leading to the paradigm shift from special

education to inclusive education worldwide.

Table 2.1International conventions and declarations leading to inclusive education

worldwide.

Year Conventions/Declarations

1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights

1959 Declaration of Rights of the Child

1975

1989

Declaration of Rights of Disabled Persons

Declaration of Rights of Disabled persons

1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child

1990 World Declaration on Education for All

1994 UNESCO’s Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on

Special Needs Education

2000 World Education Forum: The Dakar Framework for Action

(UNESCO)

2000 Millennium Declaration

2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

At that time when inclusive education was laying its foundation in the 20th century, a

concern arose globally that it should be a basic right of all children to have access to

essential, relevant and free education. Through its broad definition, UNESCO articulated:

Schools should accommodate all children regardless of their physical, intellectual, social,

emotional, linguistic or other conditions. This should include disabled and gifted children,

street and working children, children from remote or nomadic populations, children from

4

due to numerous social movements and international conventions and statements about

education. In section 2.2.4 – History and development of special education, these movements,

conventions and statements were discussed. Therefore, to respond appropriately to the

challenges in an inclusive system, understanding the historical development of inclusive

education at the international and national level is important. Table 2.2 presents a timeline of

important international conventions and statements leading to the paradigm shift from special

education to inclusive education worldwide.

Table 2.1International conventions and declarations leading to inclusive education

worldwide.

Year Conventions/Declarations

1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights

1959 Declaration of Rights of the Child

1975

1989

Declaration of Rights of Disabled Persons

Declaration of Rights of Disabled persons

1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child

1990 World Declaration on Education for All

1994 UNESCO’s Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on

Special Needs Education

2000 World Education Forum: The Dakar Framework for Action

(UNESCO)

2000 Millennium Declaration

2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

At that time when inclusive education was laying its foundation in the 20th century, a

concern arose globally that it should be a basic right of all children to have access to

essential, relevant and free education. Through its broad definition, UNESCO articulated:

Schools should accommodate all children regardless of their physical, intellectual, social,

emotional, linguistic or other conditions. This should include disabled and gifted children,

street and working children, children from remote or nomadic populations, children from

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

linguistic, ethnic or cultural minorities and children from other disadvantaged or marginalised

areas or groups (UNESCO, 1994, p. 3).

It is important to note that the education of all children has been greatly shaped by

social movements. For instance, within the global arena, UNESCO was created by the United

Nations (UN) and instructed to make sure that all adults, youngsters and children could

access basic and quality education. In broader terms, UNESCO stated that there was a need

for accommodation of all children in schools irrespective of their emotional, physical,

linguistic, social or intellectual conditions. Such children include street children, gifted

children, working children, children from remote areas, children belonging to underprivileged

groups, and children from different social, racial or dialectal minorities (Ainscow, Farrell, &

Tweddle, 2000).

One of the most important international policy documents about inclusive education is

The 1994 Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education:

We call upon all governments and urge them to adopt as a matter of law or policy the principle

of inclusive education, enrolling all children in regular schools, unless there are compelling

reasons for doing otherwise. (UNESCO 1994, p. ix).

The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education

stressed the importance of inclusion. As per the Salamanca Statement of 1994, in which 25

global firms and 92 countries participated, it was specified that all students must be educated

within inclusive classrooms. The statement highlighted, urged and required governments to

adopt and implement a legal policy based on inclusive education. It espoused the principle of

enrolling all children in regular schools until and unless there were existing convincing

motives for not doing so (Liasidou, 2016).

Following this, in 2000, when 164 governments met in Dakar, Senegal, at the World

Education Forum, they re-affirmed their commitment to achieving basic education to all

children, youth and adults as reflected in the Dakar Framework for Action. The forum

reviewed progress towards EFA and identified the following key challenge:

… to ensure that the broad vision of Education for All as an inclusive concept is reflected in national

government and funding agency policies. Education for All… must take account of the need of the poor

and the most disadvantaged, including working children, remote rural dwellers and nomads, and ethnic

and linguistic minorities, children, young people and adults affected by conflict, HIV/AIDS, hunger and

poor health; and those with special learning needs…’ (UNESCO, 2000).

5

areas or groups (UNESCO, 1994, p. 3).

It is important to note that the education of all children has been greatly shaped by

social movements. For instance, within the global arena, UNESCO was created by the United

Nations (UN) and instructed to make sure that all adults, youngsters and children could

access basic and quality education. In broader terms, UNESCO stated that there was a need

for accommodation of all children in schools irrespective of their emotional, physical,

linguistic, social or intellectual conditions. Such children include street children, gifted

children, working children, children from remote areas, children belonging to underprivileged

groups, and children from different social, racial or dialectal minorities (Ainscow, Farrell, &

Tweddle, 2000).

One of the most important international policy documents about inclusive education is

The 1994 Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education:

We call upon all governments and urge them to adopt as a matter of law or policy the principle

of inclusive education, enrolling all children in regular schools, unless there are compelling

reasons for doing otherwise. (UNESCO 1994, p. ix).

The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education

stressed the importance of inclusion. As per the Salamanca Statement of 1994, in which 25

global firms and 92 countries participated, it was specified that all students must be educated

within inclusive classrooms. The statement highlighted, urged and required governments to

adopt and implement a legal policy based on inclusive education. It espoused the principle of

enrolling all children in regular schools until and unless there were existing convincing

motives for not doing so (Liasidou, 2016).

Following this, in 2000, when 164 governments met in Dakar, Senegal, at the World

Education Forum, they re-affirmed their commitment to achieving basic education to all

children, youth and adults as reflected in the Dakar Framework for Action. The forum

reviewed progress towards EFA and identified the following key challenge:

… to ensure that the broad vision of Education for All as an inclusive concept is reflected in national

government and funding agency policies. Education for All… must take account of the need of the poor

and the most disadvantaged, including working children, remote rural dwellers and nomads, and ethnic

and linguistic minorities, children, young people and adults affected by conflict, HIV/AIDS, hunger and

poor health; and those with special learning needs…’ (UNESCO, 2000).

5

Inclusion was the main component used with EFA, and the Dakar Framework for

Action recognized the urgency of addressing these learners’ needs.It identified and stressed

the need for inclusive education systems, actively seeking out children who are not enrolled

and responding flexibly to the circumstances and needs of all learners (UNESC), 2000).

In 2000, eight different Millennium Development Goals were set by the UN

Millennium Summit, one of which was to achieve universal primary education by 2015.

Through this objective, the UN reiterated its commitment to EFA as stated earlier through the

1990 World Declaration on Education for All, reinforced subsequently by the Salamanca

Declaration of 1994.

Another powerful influence that further promoted and ensured the educational aspects

of children with disabilities was the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with

Disabilities (CRPD) and that came in 2006. CRPD had the highest number of signatories in

the UN history on the first day - 30 March, 2007 of its convention marking the official

paradigm shift in attitudes towards individuals with disability (Márton, Polk &Fiala, 2013).

The Convention aimed to protect the human rights of all persons with disabilities and to

promote respect for their inherent dignity by covering a broad range of areas including

discrimination, health, education, employment, justice and access to information. Article 24

of the Convention recognizes the right of persons with disabilities to education and it

specifically posits that;

States Parties recognize the right of persons with disabilities to education. With a view to realizing this

right without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity, States Parties shall ensure an inclusive

education system at all levels and lifelong learning. (UN, 2006, p.14)

To achieve this right, the UN proposed an inclusive education system at all learning

levels. Inclusive education here entails taking appropriate measures to hire teachers,

including teachers with disabilities, qualified in sign language and/or braille, and to train

professionals and staff who work at all levels of education (Márton, 2013). Such training is

supposed to include disability awareness and the utilization of appropriate augmentative and

alternative modes, means and forms of communication, educational techniques and materials

to support people with disabilities. The CRC therefore played an important role in the

development of inclusive education as it reinforced the principles, goals and concepts and

clarified various practices - issues in the development of inclusive schools.

6

Action recognized the urgency of addressing these learners’ needs.It identified and stressed

the need for inclusive education systems, actively seeking out children who are not enrolled

and responding flexibly to the circumstances and needs of all learners (UNESC), 2000).

In 2000, eight different Millennium Development Goals were set by the UN

Millennium Summit, one of which was to achieve universal primary education by 2015.

Through this objective, the UN reiterated its commitment to EFA as stated earlier through the

1990 World Declaration on Education for All, reinforced subsequently by the Salamanca

Declaration of 1994.

Another powerful influence that further promoted and ensured the educational aspects

of children with disabilities was the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with

Disabilities (CRPD) and that came in 2006. CRPD had the highest number of signatories in

the UN history on the first day - 30 March, 2007 of its convention marking the official

paradigm shift in attitudes towards individuals with disability (Márton, Polk &Fiala, 2013).

The Convention aimed to protect the human rights of all persons with disabilities and to

promote respect for their inherent dignity by covering a broad range of areas including

discrimination, health, education, employment, justice and access to information. Article 24

of the Convention recognizes the right of persons with disabilities to education and it

specifically posits that;

States Parties recognize the right of persons with disabilities to education. With a view to realizing this

right without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity, States Parties shall ensure an inclusive

education system at all levels and lifelong learning. (UN, 2006, p.14)

To achieve this right, the UN proposed an inclusive education system at all learning

levels. Inclusive education here entails taking appropriate measures to hire teachers,

including teachers with disabilities, qualified in sign language and/or braille, and to train

professionals and staff who work at all levels of education (Márton, 2013). Such training is

supposed to include disability awareness and the utilization of appropriate augmentative and

alternative modes, means and forms of communication, educational techniques and materials

to support people with disabilities. The CRC therefore played an important role in the

development of inclusive education as it reinforced the principles, goals and concepts and

clarified various practices - issues in the development of inclusive schools.

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

2.3.2 The (contested) concept of inclusive education

Initially inclusive education was advocated for children with disabilities where students

with disabilities were included in mainstream schools (Bunch &Valeo, 1997; Hunt & Goetz,

1997). Their learning in inclusive classrooms was supported with appropriate teaching aids

and additional support. However, due to the lack of clarity about its meaning, inclusive

education means ‘different things to different people’ and the risk could be ‘that inclusion

may end up meaning everything and nothing at the same time’ (Armstrong, Armstrong

&Spandagou, 2010, p.29). Therefore, the right to inclusive education that applies to all

children with disabilities is authoritatively articulated in Article 24, Comment 4 of the CRPD

which the UN has urged all its signatories to comply. () has stated that inclusive education

will be successful only when the Government is able to appoint some special investigation

and implementation team. () has suggested in the similar context that no policy is successful

unless and until there is a proper feedback and evaluation undertaken. Though Government

and the other educational organizations are doing a good job by formulation new policies for

inclusion of the disabled students they gave to focus over the proper implementation as well.

Ainscow and Sandhill (2010); Graham and Jahnukainen, (2011) contest that inclusive

education is not exclusively for students with SEN, but rather encompasses the education of

all students. Countries like Australia, the UK and the US have implemented inclusive

education where students from all backgrounds, including children with SEN, are enrolled in

mainstream schools (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Forlin, 2012; Gerber, 2012). However many

developing countries, such as Bangladesh, Bhutan, Ghana, India, Malaysia and Thailand,

focus their inclusive education efforts toward children with SEN (Chhetri, 2015), 2015; Deku

and Ackah-Jnr, 2012; Ibrahim, 2012; Sharma, Shaukat &Furlonger, 2015; Srivastava, Boer

&Pijl, 2015). Barro et al. (2017) stated that some reasons for this include constraints in

resource allocation, including inadequate budgets for implementing inclusive education,

poorly equipped teachers in terms of knowledge and skills about inclusive education, poor

government support towards inclusive education, and the absence of consistent government

policy on inclusive education. Hence Waitoller and Artiles’s (2013) observation that

inclusive education has different meanings in different countries is justified by how

differently inclusion is being implemented as educational reform.

In the past, inclusion has been a complex and contested concept. A very common

misunderstanding is that inclusion is a synonym for integration in which inclusion is simply

the presence of a child with SEN in a mainstream school (Cologon, 2015). Such a

7

Initially inclusive education was advocated for children with disabilities where students

with disabilities were included in mainstream schools (Bunch &Valeo, 1997; Hunt & Goetz,

1997). Their learning in inclusive classrooms was supported with appropriate teaching aids

and additional support. However, due to the lack of clarity about its meaning, inclusive

education means ‘different things to different people’ and the risk could be ‘that inclusion

may end up meaning everything and nothing at the same time’ (Armstrong, Armstrong

&Spandagou, 2010, p.29). Therefore, the right to inclusive education that applies to all

children with disabilities is authoritatively articulated in Article 24, Comment 4 of the CRPD

which the UN has urged all its signatories to comply. () has stated that inclusive education

will be successful only when the Government is able to appoint some special investigation

and implementation team. () has suggested in the similar context that no policy is successful

unless and until there is a proper feedback and evaluation undertaken. Though Government

and the other educational organizations are doing a good job by formulation new policies for

inclusion of the disabled students they gave to focus over the proper implementation as well.

Ainscow and Sandhill (2010); Graham and Jahnukainen, (2011) contest that inclusive

education is not exclusively for students with SEN, but rather encompasses the education of

all students. Countries like Australia, the UK and the US have implemented inclusive

education where students from all backgrounds, including children with SEN, are enrolled in

mainstream schools (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Forlin, 2012; Gerber, 2012). However many

developing countries, such as Bangladesh, Bhutan, Ghana, India, Malaysia and Thailand,

focus their inclusive education efforts toward children with SEN (Chhetri, 2015), 2015; Deku

and Ackah-Jnr, 2012; Ibrahim, 2012; Sharma, Shaukat &Furlonger, 2015; Srivastava, Boer

&Pijl, 2015). Barro et al. (2017) stated that some reasons for this include constraints in

resource allocation, including inadequate budgets for implementing inclusive education,

poorly equipped teachers in terms of knowledge and skills about inclusive education, poor

government support towards inclusive education, and the absence of consistent government

policy on inclusive education. Hence Waitoller and Artiles’s (2013) observation that

inclusive education has different meanings in different countries is justified by how

differently inclusion is being implemented as educational reform.

In the past, inclusion has been a complex and contested concept. A very common

misunderstanding is that inclusion is a synonym for integration in which inclusion is simply

the presence of a child with SEN in a mainstream school (Cologon, 2015). Such a

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

misunderstanding contributes to a notion that inclusion is for some students only (instead of

everyone) where inclusion is viewed as a process of adjustment — mere placing of students

in classrooms instead of academic achievement. Carrington and MacArthur (2012)

highlighted four issues when considering education reform towards inclusive schooling. First,

there is a need for teachers to have a broad and deep understanding of what inclusion means.

Unless teachers are guided to become more aware of their assumptions and beliefs and the

implications for inclusion, they will find it difficult to think of alternative teaching practices

to support inclusive education (Whittaker, 2017). Second, the models for teacher education

need to be considered as teachers have a critical role to play in progressing inclusive

education. Many teachers are not informed about inclusive education policy and practice

(Graham &Spandagou, 2011). Teachers’ lack of knowledge can become a barrier to inclusion

education.

The third issue to be considered is the organization and resourcing of schools. As per

the opinion of Howell, McKenzie and Chataika, T. (2018) inclusive practices in schools can

be strengthened by expanding broader educational reform agendas that take care of the lack

of attention to students with disabilities and also promote deficit thinking models around the

disability of students (Williams, Shealey, & Blanchett, 2009). More and better support

towards inclusive practices can be provided by educational leaders who have greater

knowledge about resources to support inclusive education, knowledge of legal dimensions of

inclusive practice and in educating students with disabilities (Birnbaum, 2006), knowledge of

collaborative teaching and support arrangements (Carrington & MacArthur, 2012; Sailor,

2009; Zeretsky, 2005), and skills in professional development initiatives that support

inclusive practices (Hochberg & Desimone, 2010; USDOE, 2002) Finally, the social

implications of inclusion are another issue. Social and cultural contexts are fundamental for

the success of inclusion. Whittaker (2017) has argued it makes children suffer the same

context that the help and support systems must be developed in a proper way so that the issue

of stigmatization can be removed. Kruijsen-Terpstr et al. (2016) has agreed to the same

saying that the very method of segregation itself makes the disabled children suffer from a

feeling of isolation. Thus proper counselling sessions have to be arranged so that the children

do not suffer from any kinds of ill feelings or feelings of stigmatization. Barro et al. (2017)

has also stated that occupational therapists or the mental health social workers must be used

in this aspect. This will help in engaging these children into the different kinds of social

activities.

8

everyone) where inclusion is viewed as a process of adjustment — mere placing of students

in classrooms instead of academic achievement. Carrington and MacArthur (2012)

highlighted four issues when considering education reform towards inclusive schooling. First,

there is a need for teachers to have a broad and deep understanding of what inclusion means.

Unless teachers are guided to become more aware of their assumptions and beliefs and the

implications for inclusion, they will find it difficult to think of alternative teaching practices

to support inclusive education (Whittaker, 2017). Second, the models for teacher education

need to be considered as teachers have a critical role to play in progressing inclusive

education. Many teachers are not informed about inclusive education policy and practice

(Graham &Spandagou, 2011). Teachers’ lack of knowledge can become a barrier to inclusion

education.

The third issue to be considered is the organization and resourcing of schools. As per

the opinion of Howell, McKenzie and Chataika, T. (2018) inclusive practices in schools can

be strengthened by expanding broader educational reform agendas that take care of the lack

of attention to students with disabilities and also promote deficit thinking models around the

disability of students (Williams, Shealey, & Blanchett, 2009). More and better support

towards inclusive practices can be provided by educational leaders who have greater

knowledge about resources to support inclusive education, knowledge of legal dimensions of

inclusive practice and in educating students with disabilities (Birnbaum, 2006), knowledge of

collaborative teaching and support arrangements (Carrington & MacArthur, 2012; Sailor,

2009; Zeretsky, 2005), and skills in professional development initiatives that support

inclusive practices (Hochberg & Desimone, 2010; USDOE, 2002) Finally, the social

implications of inclusion are another issue. Social and cultural contexts are fundamental for

the success of inclusion. Whittaker (2017) has argued it makes children suffer the same

context that the help and support systems must be developed in a proper way so that the issue

of stigmatization can be removed. Kruijsen-Terpstr et al. (2016) has agreed to the same

saying that the very method of segregation itself makes the disabled children suffer from a

feeling of isolation. Thus proper counselling sessions have to be arranged so that the children

do not suffer from any kinds of ill feelings or feelings of stigmatization. Barro et al. (2017)

has also stated that occupational therapists or the mental health social workers must be used

in this aspect. This will help in engaging these children into the different kinds of social

activities.

8

It is argued that segregation because of exclusion from society has a negative impact on

children who experience disability resulting in marginalization, stigmatisation, bullying and

abuse (Biklen & Burke, 2006). This calls for policies that respect the diversity of individuals

and families and acknowledge the rights of children to inclusive schooling. It is through such

policies and attention to inclusive practice that education leaders, teachers and school

administrators can understand the difference between the two paradigms of inclusive

education and special education.

Inclusive education may be understood differently especially when viewed from

different perspectives(Slee, 2001, 2008; Sharma &Sokal, 2015). In general, education is

framed by cultural and social contexts. Therefore, viewing inclusive education from cultural

and social perspectives is key to successful inclusion (Ainscow, Booth & Dyson, 2006).

When a culturally inclusive learning environment is created, it helps to develop personal

contacts which is important for individuals with disabilities. It also helps to develop effective

intercultural skills. This means all individuals – regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, religious

affiliation, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation or political beliefs are encouraged to

foster cultural inclusivity, mutual respect and genuine appreciation of diversity (Graham

&Spandagou, 2011). This in turn builds a harmonious society. Thus, considering culture as

an intrinsic part of each student’s life, schools play a crucial role in creating a culturally

inclusive classroom through which all children learn from each other and respect the culture

of each other (Howell, McKenzie & Chataika, 2018). The four strategies identified by

Barker, Frederiks and Farrelly to create a culturally inclusive classroom environment will

now be discussed in the following section.

Barker, Frederiks and Farrelly (u.d) recommended four important strategies to creating

a culturally inclusive classroom environment as discussed below.

9

children who experience disability resulting in marginalization, stigmatisation, bullying and

abuse (Biklen & Burke, 2006). This calls for policies that respect the diversity of individuals

and families and acknowledge the rights of children to inclusive schooling. It is through such

policies and attention to inclusive practice that education leaders, teachers and school

administrators can understand the difference between the two paradigms of inclusive

education and special education.

Inclusive education may be understood differently especially when viewed from

different perspectives(Slee, 2001, 2008; Sharma &Sokal, 2015). In general, education is

framed by cultural and social contexts. Therefore, viewing inclusive education from cultural

and social perspectives is key to successful inclusion (Ainscow, Booth & Dyson, 2006).

When a culturally inclusive learning environment is created, it helps to develop personal

contacts which is important for individuals with disabilities. It also helps to develop effective

intercultural skills. This means all individuals – regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, religious

affiliation, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation or political beliefs are encouraged to

foster cultural inclusivity, mutual respect and genuine appreciation of diversity (Graham

&Spandagou, 2011). This in turn builds a harmonious society. Thus, considering culture as

an intrinsic part of each student’s life, schools play a crucial role in creating a culturally

inclusive classroom through which all children learn from each other and respect the culture

of each other (Howell, McKenzie & Chataika, 2018). The four strategies identified by

Barker, Frederiks and Farrelly to create a culturally inclusive classroom environment will

now be discussed in the following section.

Barker, Frederiks and Farrelly (u.d) recommended four important strategies to creating

a culturally inclusive classroom environment as discussed below.

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Figure 2.2Recommended strategies to assist with creating a culturally inclusive classroom

(Source: Barker, Frederiks&Farrelly, n.d, p.1).

Positive interactions with students: In a culturally inclusive classroom both students

and teachers have the prospect of recognising and appreciating diversity, which in turn

develops the overall learning experience. According to Carrington, MacArthur, Kearney,

Kimber, Mercer and Morton’s (2012), teachers are agents of change who ‘can model

inclusion and social justice in schools’ (2012, p. 79). Therefore, teachers must engage

themselves in positive interactions with students to gain information, for example something

unique about students’ cultural backgrounds. Lately, ‘social inclusion’ has come to be

considered highly important, focusing attention on the interactions of teachers and students

within the classroom (Foreman, 2008). Social inclusion is the act of making all students in a

classroom feel valued and important which can be achieved through ‘peer acceptance,

friendships and participation in groups’ (Foreman, 2008, p. 207). Therefore, it is important

for teachers to display positive nonverbal cues like eye contact and inviting facial expressions

to make themselves approachable to students, which will allow students to participate in

classroom activities more inclusively. Since inclusion is based on justice and rights, teachers

working for inclusion also work for democratic education (Slee, 2011). Therefore, if teachers

do not facilitate or encourage students’ participation, ‘then this is exclusion and is against

democratic practice’ (Carrington, MacArthur, Kearney, Kimber, Mercer & Morton, 2012, p.

80).

Use inclusive language and appropriate modes of address: Social interactions are vital

for successful and productive participations in society (Loreman, Deppeler& Harvey, 2005).

Similarly, students should be motivated to participate in classroom discussions through

communication. The need to communicate effectively for students in an inclusive setting

includes the need to be accepted — to fit in, make friends and be liked (Shultz, 1988). Some

10

(Source: Barker, Frederiks&Farrelly, n.d, p.1).

Positive interactions with students: In a culturally inclusive classroom both students

and teachers have the prospect of recognising and appreciating diversity, which in turn

develops the overall learning experience. According to Carrington, MacArthur, Kearney,

Kimber, Mercer and Morton’s (2012), teachers are agents of change who ‘can model

inclusion and social justice in schools’ (2012, p. 79). Therefore, teachers must engage

themselves in positive interactions with students to gain information, for example something

unique about students’ cultural backgrounds. Lately, ‘social inclusion’ has come to be

considered highly important, focusing attention on the interactions of teachers and students

within the classroom (Foreman, 2008). Social inclusion is the act of making all students in a

classroom feel valued and important which can be achieved through ‘peer acceptance,

friendships and participation in groups’ (Foreman, 2008, p. 207). Therefore, it is important

for teachers to display positive nonverbal cues like eye contact and inviting facial expressions

to make themselves approachable to students, which will allow students to participate in

classroom activities more inclusively. Since inclusion is based on justice and rights, teachers

working for inclusion also work for democratic education (Slee, 2011). Therefore, if teachers

do not facilitate or encourage students’ participation, ‘then this is exclusion and is against

democratic practice’ (Carrington, MacArthur, Kearney, Kimber, Mercer & Morton, 2012, p.

80).

Use inclusive language and appropriate modes of address: Social interactions are vital

for successful and productive participations in society (Loreman, Deppeler& Harvey, 2005).

Similarly, students should be motivated to participate in classroom discussions through

communication. The need to communicate effectively for students in an inclusive setting

includes the need to be accepted — to fit in, make friends and be liked (Shultz, 1988). Some

10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

strategies that teachers can adopt to motivate communication among students are: 1) through

the use of ‘inclusive language that avoids ethnocentric tones – for example ‘family name’

rather than last name and ‘given name’ rather than ‘Christian name’ (Barker,

Frederiks&Farrelly, n.d); 2) referring to students by their names as much as possible and by

asking to address them in the way they prefer; and 3) correct pronunciation of names as it

demonstrates cultural awareness and respect. To enable teachers to apply these strategies,

Florian (2012) acclaims the need for teacher education to consider students’ increasing

cultural and linguistic diversity in classrooms. () is of the opinon that children from the non

native English speaking background are ofren then victims of bullying. Thus they often feel

neglected in their schools and their classroom set ups. They suffer from the feeling that they

are di8fferent and do not belong to the general accepted crowd of their classes. Good and

Lavigne (2017) has stated that school bullying and harassments are also due to the lack of

proper awareness among the students and also the class teachers. Thus efforts have to be

made to interact with the children freely and supporting them to overcome their problem.

Cross cultural competency developments must be initiated right from an early stage so that

students realize about the importance of embracing the cross cultural differences. Language

translators and interpreters are to be appointed in schools so that they can act as a bridge

between the native and the non native English speaking students. Horizontal communication

and interaction sessions must be developed so that students can understand each other and

help each other with proper cooperation and support.

Actively discourage classroom incivilities: Students are very sensitive to teacher’s

actions and teacher’s treatment of them. Teachers should be careful not to ignore or neglect

the needs of their students. For example, when answering questions, teachers should ensure

that every student’s response is considered and that teachers do not favour one group over

another. Priority should be given to protect against cultural exclusion and insensitivity

through effective communication to display mutual respect and support student diversity. An

effective way of providing support is ‘when practitioners (teachers) plan activities with all

children in mind, recognizing their different starting points, experiences, interests and

learning styles, or when children help each other’ (Booth, Ainscow& Kingston, 2006, p. 7).

One benefit of planning activities to support the participation of all children is to reduce the

need for individual support. Hence, when mass participation is encouraged, inclusion

becomes effective.

11

the use of ‘inclusive language that avoids ethnocentric tones – for example ‘family name’

rather than last name and ‘given name’ rather than ‘Christian name’ (Barker,

Frederiks&Farrelly, n.d); 2) referring to students by their names as much as possible and by

asking to address them in the way they prefer; and 3) correct pronunciation of names as it

demonstrates cultural awareness and respect. To enable teachers to apply these strategies,

Florian (2012) acclaims the need for teacher education to consider students’ increasing

cultural and linguistic diversity in classrooms. () is of the opinon that children from the non

native English speaking background are ofren then victims of bullying. Thus they often feel

neglected in their schools and their classroom set ups. They suffer from the feeling that they

are di8fferent and do not belong to the general accepted crowd of their classes. Good and

Lavigne (2017) has stated that school bullying and harassments are also due to the lack of

proper awareness among the students and also the class teachers. Thus efforts have to be

made to interact with the children freely and supporting them to overcome their problem.

Cross cultural competency developments must be initiated right from an early stage so that

students realize about the importance of embracing the cross cultural differences. Language

translators and interpreters are to be appointed in schools so that they can act as a bridge

between the native and the non native English speaking students. Horizontal communication

and interaction sessions must be developed so that students can understand each other and

help each other with proper cooperation and support.

Actively discourage classroom incivilities: Students are very sensitive to teacher’s

actions and teacher’s treatment of them. Teachers should be careful not to ignore or neglect

the needs of their students. For example, when answering questions, teachers should ensure

that every student’s response is considered and that teachers do not favour one group over

another. Priority should be given to protect against cultural exclusion and insensitivity

through effective communication to display mutual respect and support student diversity. An

effective way of providing support is ‘when practitioners (teachers) plan activities with all

children in mind, recognizing their different starting points, experiences, interests and

learning styles, or when children help each other’ (Booth, Ainscow& Kingston, 2006, p. 7).

One benefit of planning activities to support the participation of all children is to reduce the

need for individual support. Hence, when mass participation is encouraged, inclusion

becomes effective.

11

Encourage open, honest and respectful inclusive class discussion: Teachers can create

an inclusive atmosphere in the classroom by letting students take turns when expressing their

own opinions and also by encouraging them to consider listening to the views of others.

Another way to encourage class discussion is by inviting students to respond using open-

ended statements such as, would anyone like to give a different answer or opinion?

The above discussions make it clear how inclusive education can be influenced by

cultural perspectives. Research has shown that culture, specific to a place or a region has

always played a larger role in the conceptualization and implementation of inclusive

education (Booth and Ainscow, 2016; Webber and Lupart, 2011). Accepting children with

disabilities particularly in schools has never been an issue in Bhutan. A study on Bhutanese

teachers’ perception on inclusion and disability by Drukpa and Kamenopoulou (2017, p.10)

ascertained that Bhutanese teachers’ ‘understanding of inclusion was compatible with the

broader view of inclusion as the elimination of all forms of discrimination and with the

rights-based/social model approach’. Nevertheless, it needs to be pointed out that inclusion in

schools in Bhutan still focuses mainly on children with disabilities (Chhetri, 2015; Dorji,

2015) which is aligned with the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, 1994).

Within every school there exists a culture that includes beliefs, values and the school’s

own ways of doing things within its community (Carrington, MacArthur, Kearney, Kimber,

Mercer & Morton, 2012). When such perspectives are respected, there is more support

towards inclusion and when inclusion becomes a practice, it encourages higher levels of

interaction than segregated settings (Cologon, 2013). For many countries in South Asia like

India (Antil, 2014; Sanjeev & Kumar, 2007; Singal, 2005) Nepal (Khamal, 2018; Regmi,

2017), Srilanka (Wijesekera, Alford &Guanglun Mu, 2018) Bangladesh (Ahsan, Sharma

&Deppeler, 2012) and Bhutan (Dorji, 2015; Kamenopoulou&Dukpa, 2018) where the

concept of inclusive education is still new, consideration of socio-cultural contexts remains a

challenge in the successful implementation of inclusive education.

To some extent, the term ‘inclusive education’ has been plagued by conceptual

confusion, ideological struggles, and a lack of national and local policies (Slee, 2008).

Despite the emphasis laid by Article 24 of CRPD in promoting education of children with

disabilities through inclusion, there are some draw backs and many countries continue to face

the challenges of defining the meaning, purpose and content of inclusive education. As

discussed, despite several international assertions that promote equal educational

opportunities, research has found that “the levels at which inclusive education is practised are

12

an inclusive atmosphere in the classroom by letting students take turns when expressing their

own opinions and also by encouraging them to consider listening to the views of others.

Another way to encourage class discussion is by inviting students to respond using open-

ended statements such as, would anyone like to give a different answer or opinion?

The above discussions make it clear how inclusive education can be influenced by

cultural perspectives. Research has shown that culture, specific to a place or a region has

always played a larger role in the conceptualization and implementation of inclusive

education (Booth and Ainscow, 2016; Webber and Lupart, 2011). Accepting children with

disabilities particularly in schools has never been an issue in Bhutan. A study on Bhutanese

teachers’ perception on inclusion and disability by Drukpa and Kamenopoulou (2017, p.10)

ascertained that Bhutanese teachers’ ‘understanding of inclusion was compatible with the

broader view of inclusion as the elimination of all forms of discrimination and with the

rights-based/social model approach’. Nevertheless, it needs to be pointed out that inclusion in

schools in Bhutan still focuses mainly on children with disabilities (Chhetri, 2015; Dorji,

2015) which is aligned with the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, 1994).

Within every school there exists a culture that includes beliefs, values and the school’s

own ways of doing things within its community (Carrington, MacArthur, Kearney, Kimber,

Mercer & Morton, 2012). When such perspectives are respected, there is more support

towards inclusion and when inclusion becomes a practice, it encourages higher levels of

interaction than segregated settings (Cologon, 2013). For many countries in South Asia like

India (Antil, 2014; Sanjeev & Kumar, 2007; Singal, 2005) Nepal (Khamal, 2018; Regmi,

2017), Srilanka (Wijesekera, Alford &Guanglun Mu, 2018) Bangladesh (Ahsan, Sharma

&Deppeler, 2012) and Bhutan (Dorji, 2015; Kamenopoulou&Dukpa, 2018) where the

concept of inclusive education is still new, consideration of socio-cultural contexts remains a

challenge in the successful implementation of inclusive education.

To some extent, the term ‘inclusive education’ has been plagued by conceptual

confusion, ideological struggles, and a lack of national and local policies (Slee, 2008).

Despite the emphasis laid by Article 24 of CRPD in promoting education of children with

disabilities through inclusion, there are some draw backs and many countries continue to face

the challenges of defining the meaning, purpose and content of inclusive education. As

discussed, despite several international assertions that promote equal educational

opportunities, research has found that “the levels at which inclusive education is practised are

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 39

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.