Social Forces 98(2) - Gender Inequality in Product Markets Research

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/22

|30

|15731

|23

Report

AI Summary

This research paper, published in Social Forces, investigates gender inequality in product markets through three online experiments. The study, conducted by Elise Tak, Shelley J. Correll, and Sarah A. Soule at Stanford University, explores how gender status beliefs influence product evaluations. The authors develop a theory of status belief transfer, demonstrating that products made by women are disadvantaged in male-typed markets (craft beer) but not in female-typed markets (cupcakes). The research reveals an asymmetric negative bias, where products made by women receive lower evaluations in male-dominated markets. The study also examines the moderating effects of external status conferral and evaluator's product knowledge. The findings highlight the pervasive influence of gender-typing in product markets and suggest strategies to mitigate gender biases, drawing on status characteristics theory (SCT) to explain how these biases are perpetuated.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Gender Inequality in Product Markets: When an

How Status Beliefs Transfer to Products

Elise Tak, Stanford University

Shelley J. Correll and Sarah A. Soule, Stanford University

This paper develops and evaluates a theory of status belief transfer, the

by which gender status beliefs differentially affect the evaluations of pr

made by men and women.We conductthree online experiments to evaluate

this theory. In Study 1, we gathered 50 product categories from a large onli

and had participants rate each product’s association with femininity and ma

We find evidence ofthe pervasiveness ofgender-typing in productmarkets.In

Studies 2 and 3,we simulate male-typed and female-typed productmarkets (craft

beerand cupcakes,respectively).In the male-typed productmarket,a craftbeer

described as produced by a woman is evaluated more negatively than the s

product described as produced by a man. Consistent with our predictions, w

find that if the beer is conferred externalstatus via an award,the evaluation of the

beer made by a woman improves by a greater magnitude than the same be

by a man.In the female-typed productmarketof cupcakes,the producer’s gender

does not affect ratings. Together, the two studies provide evidence of an as

negative bias:products made by women are disadvantaged in male-typed ma

butproducts made by men are notdisadvantaged in female-typed markets.These

studies also provide compelling evidence of status belief transfer from prod

their products. We draw out the implications of these findings and suggest w

gender biases in product markets can be reduced.

Introduction

Research has consistently shown that women are disadvantaged by the sta

belief that they are less competent than men, which leads people to have lo

expectationsfor women’sperformance relativeto men’s (Ridgeway 2011).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

This research wassupported bya grant from the Stanford GraduateSchool of Business,

“Collaboration and Innovation in the American Craft Beer Industry.” Stanford University appro

this IRB protocol (31730).An earlier version of this paper was presented atthe American

SociologicalAssociation Meetings in August2015 in Chicago,Stanford–Berkeley Organizational

Behavior Conference,EGOS 2016, and the Academy ofManagementMeeting 2017 in Atlanta,

Chicago,IL. The authors would like to thank the participants ofthe Stanford Organizational

Behavior Seminar for comments on an earlier version of this paper. Direct correspondence to

Tak, 655 Knight Way, Stanford, CA, 94305; email:etak@stanford.edu.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

© The Author(s) 2019. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. All rights reserved. For permissions,

please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com.

Social Forces 98(2) 548–577, November 2019

doi: 10.1093/sf/soy125

Advance Access publication on 22 January 2019

Gender Inequality in Product Markets

Social Forces 98(2)548

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Gender Inequality in Product Markets: When an

How Status Beliefs Transfer to Products

Elise Tak, Stanford University

Shelley J. Correll and Sarah A. Soule, Stanford University

This paper develops and evaluates a theory of status belief transfer, the

by which gender status beliefs differentially affect the evaluations of pr

made by men and women.We conductthree online experiments to evaluate

this theory. In Study 1, we gathered 50 product categories from a large onli

and had participants rate each product’s association with femininity and ma

We find evidence ofthe pervasiveness ofgender-typing in productmarkets.In

Studies 2 and 3,we simulate male-typed and female-typed productmarkets (craft

beerand cupcakes,respectively).In the male-typed productmarket,a craftbeer

described as produced by a woman is evaluated more negatively than the s

product described as produced by a man. Consistent with our predictions, w

find that if the beer is conferred externalstatus via an award,the evaluation of the

beer made by a woman improves by a greater magnitude than the same be

by a man.In the female-typed productmarketof cupcakes,the producer’s gender

does not affect ratings. Together, the two studies provide evidence of an as

negative bias:products made by women are disadvantaged in male-typed ma

butproducts made by men are notdisadvantaged in female-typed markets.These

studies also provide compelling evidence of status belief transfer from prod

their products. We draw out the implications of these findings and suggest w

gender biases in product markets can be reduced.

Introduction

Research has consistently shown that women are disadvantaged by the sta

belief that they are less competent than men, which leads people to have lo

expectationsfor women’sperformance relativeto men’s (Ridgeway 2011).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

This research wassupported bya grant from the Stanford GraduateSchool of Business,

“Collaboration and Innovation in the American Craft Beer Industry.” Stanford University appro

this IRB protocol (31730).An earlier version of this paper was presented atthe American

SociologicalAssociation Meetings in August2015 in Chicago,Stanford–Berkeley Organizational

Behavior Conference,EGOS 2016, and the Academy ofManagementMeeting 2017 in Atlanta,

Chicago,IL. The authors would like to thank the participants ofthe Stanford Organizational

Behavior Seminar for comments on an earlier version of this paper. Direct correspondence to

Tak, 655 Knight Way, Stanford, CA, 94305; email:etak@stanford.edu.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

© The Author(s) 2019. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. All rights reserved. For permissions,

please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com.

Social Forces 98(2) 548–577, November 2019

doi: 10.1093/sf/soy125

Advance Access publication on 22 January 2019

Gender Inequality in Product Markets

Social Forces 98(2)548

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

fined as culturally shared expectations about the competency or

worthiness of certain socialcategories (Correlland Ridgeway 2006),powerfully

shape evaluations and interactions in ways that disadvantage members of deva

groups.These beliefs have substantialrepercussions in the labor market—in the

case of gender, women,relative to men,tend to be judged by harsher standards

(Foschi1996,2000;Steinpreis,Anders and Ritzke 1999),are compensated less

(Castilla and Benard 2010),are less likely to get jobs (Goldin and Rouse 2000;

Turco 2010; Correll et al. 2007), and are less satisfied with their jobs (Chan and

Anteby 2015).These patterns are especially pronounced for women in male-

dominated jobs (Turco 2010). In contrast, there is no consistent evidence of suc

penalties for men in female-dominated domains (Taylor 2010; Williams 1992).

While there is extensive research on the disadvantaging effects of status beli

in the domain of labor markets, there is surprisingly little work on the effects of

these status beliefs on the evaluations of products.1 This is surprising because

many products are closely associated with those who produce them,as is the

case in entrepreneurship (e.g.,Thornton 1999),smalland medium businesses,

scholarly work (Simcoe and Waguespack2011), and cultural markets

(DiMaggio 1987). If, as we argue in more detail below, status beliefs about indi-

vidual producers transfer to their products, status beliefs affect the assessment

of the quality of products, in addition to affecting the assessments of the people

producing them. This suggests that the effects of gender status beliefs on gend

inequality in the economy are greater than previously shown.

In this paper, we draw on status characteristics theory (SCT) to develop and

evaluate a theory of status belief transfer, showing how gender status beliefs d

ferentially affect the evaluations of products made by men and women. We pre

dict that genderstatusbeliefsabout men and women willtransferto the

products they produce,such that there willbe a lower evaluation of products

made by women in certain product markets. To the extent that our predictions

hold, this implies that in many product markets,a female producer would be

rated lower than an otherwise equal male producer (e.g., being seen as less cap

ble of delivering a product) and that her product itself would also be seen as

lower quality.

We conductthree experimentalstudiesto examine these ideas.Study 1

shows the pervasiveness of gender-typing in product markets by testing for cul

tural associations with masculinity or femininity among fifty widely used pro-

ducts. Studies 2 and 3 test for the transfer of status beliefs from the producer t

their products by investigating how products made by men and women fare in

male-typed and female-typed markets, respectively. We find that women-made

products receive lower evaluation than the same product made by a man in a

male-typed market (Study 2), but that this penalty does not exist for men-made

products in a female-typed market(Study 3).Furthermore,we develop and

evaluate two mechanisms that moderate the effect of gender status beliefs on

product evaluations:externalstatus conferraland evaluator’s product knowl-

edge. We conclude by drawing out the implications of our findings for reducing

gender biases in product markets.

Status beliefs, de

Gender Inequality in Product Markets549 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

worthiness of certain socialcategories (Correlland Ridgeway 2006),powerfully

shape evaluations and interactions in ways that disadvantage members of deva

groups.These beliefs have substantialrepercussions in the labor market—in the

case of gender, women,relative to men,tend to be judged by harsher standards

(Foschi1996,2000;Steinpreis,Anders and Ritzke 1999),are compensated less

(Castilla and Benard 2010),are less likely to get jobs (Goldin and Rouse 2000;

Turco 2010; Correll et al. 2007), and are less satisfied with their jobs (Chan and

Anteby 2015).These patterns are especially pronounced for women in male-

dominated jobs (Turco 2010). In contrast, there is no consistent evidence of suc

penalties for men in female-dominated domains (Taylor 2010; Williams 1992).

While there is extensive research on the disadvantaging effects of status beli

in the domain of labor markets, there is surprisingly little work on the effects of

these status beliefs on the evaluations of products.1 This is surprising because

many products are closely associated with those who produce them,as is the

case in entrepreneurship (e.g.,Thornton 1999),smalland medium businesses,

scholarly work (Simcoe and Waguespack2011), and cultural markets

(DiMaggio 1987). If, as we argue in more detail below, status beliefs about indi-

vidual producers transfer to their products, status beliefs affect the assessment

of the quality of products, in addition to affecting the assessments of the people

producing them. This suggests that the effects of gender status beliefs on gend

inequality in the economy are greater than previously shown.

In this paper, we draw on status characteristics theory (SCT) to develop and

evaluate a theory of status belief transfer, showing how gender status beliefs d

ferentially affect the evaluations of products made by men and women. We pre

dict that genderstatusbeliefsabout men and women willtransferto the

products they produce,such that there willbe a lower evaluation of products

made by women in certain product markets. To the extent that our predictions

hold, this implies that in many product markets,a female producer would be

rated lower than an otherwise equal male producer (e.g., being seen as less cap

ble of delivering a product) and that her product itself would also be seen as

lower quality.

We conductthree experimentalstudiesto examine these ideas.Study 1

shows the pervasiveness of gender-typing in product markets by testing for cul

tural associations with masculinity or femininity among fifty widely used pro-

ducts. Studies 2 and 3 test for the transfer of status beliefs from the producer t

their products by investigating how products made by men and women fare in

male-typed and female-typed markets, respectively. We find that women-made

products receive lower evaluation than the same product made by a man in a

male-typed market (Study 2), but that this penalty does not exist for men-made

products in a female-typed market(Study 3).Furthermore,we develop and

evaluate two mechanisms that moderate the effect of gender status beliefs on

product evaluations:externalstatus conferraland evaluator’s product knowl-

edge. We conclude by drawing out the implications of our findings for reducing

gender biases in product markets.

Status beliefs, de

Gender Inequality in Product Markets549 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

A status characteristic is a nominaldistinction,such as an ascribed attribute

(e.g., race or gender) or a role (e.g., professor or mother), with widely share

liefs aboutthe competence or worthiness ofdifferentstates ofthe distinction

(e.g., men versus women) (Berger, Cohen, and Zelditch 1972). These beliefs

important because they affect relative expectations individuals have for the

formance of individuals in evaluative contexts (Ridgeway and Correll 2004).

a consequence, in the case of gender, people tend to have higher performa

pectations for men compared to women, leading men to be judged as more

petent than women (Foschi 1996, 2000). SCT has been widely used to expla

the differences in evaluative outcomes of people in labor markets (Foschi 19

2000;Steinpreis,Anders,and Ritzke 1999)and in organizations (Bunderson

2003; Turco 2010).

We argue that status beliefs also transfer to the products that men and w

make, and we theorize about the mechanism of status belief transfer. There

both theoretical and empirical reasons to expect that status belief transfer i

vasive and is also an important mechanism by which inequality is perpetuat

outside of the domain of labor markets. From a theoretical perspective, the

that status beliefs may spread to “non-status elements” was an assumption

the foundationalwork on SCT by Berger et al.(1972,p. 245).However,this

assumption has notbeen systematically tested,which has limited our under-

standing of the extent to which status beliefs transfer from individuals to pr

ducts. In addition to providing a test of the mechanism, we also develop a n

argument for why status beliefs transfer to products. We do so by investigat

how status beliefs shape evaluations of products in male- and female-typed

kets. Empirically, in many product markets, there are close associations bet

the productand its producer.Examples include scholarly work (Simcoe and

Waguespack 2011),cultural products(DiMaggio 1987) and products of

entrepreneurialendeavors (Thornton 1999).Understanding the mechanism of

status belief transfer will illuminate how status-based gender inequality is p

uated in these product markets.

Status Beliefs and the Evaluations of Products in Male- and Fem

Typed Markets

Conceptually, there are two types of status characteristics that have been s

to affect the evaluation of individuals:specificand diffuse (Correll and

Ridgeway 2006). Specific status characteristics, such as an occupational rol

possession ofspecific skillset,carry culturalexpectations for a well-defined

range of tasks, thus forming beliefs and aiding evaluations in a limited rang

contexts (Kunda and Spencer 2003). For instance, without specific informat

about an individual, we expect a software engineer to be competent at prog

ming a computer and a kindergarten teacher to be adept at teaching childre

the extent that those characteristics are relevant to the task at hand, specifi

tus characteristics influence performance expectations.

A Theory of Status Belief Transfer

Social Forces 98(2)550

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

(e.g., race or gender) or a role (e.g., professor or mother), with widely share

liefs aboutthe competence or worthiness ofdifferentstates ofthe distinction

(e.g., men versus women) (Berger, Cohen, and Zelditch 1972). These beliefs

important because they affect relative expectations individuals have for the

formance of individuals in evaluative contexts (Ridgeway and Correll 2004).

a consequence, in the case of gender, people tend to have higher performa

pectations for men compared to women, leading men to be judged as more

petent than women (Foschi 1996, 2000). SCT has been widely used to expla

the differences in evaluative outcomes of people in labor markets (Foschi 19

2000;Steinpreis,Anders,and Ritzke 1999)and in organizations (Bunderson

2003; Turco 2010).

We argue that status beliefs also transfer to the products that men and w

make, and we theorize about the mechanism of status belief transfer. There

both theoretical and empirical reasons to expect that status belief transfer i

vasive and is also an important mechanism by which inequality is perpetuat

outside of the domain of labor markets. From a theoretical perspective, the

that status beliefs may spread to “non-status elements” was an assumption

the foundationalwork on SCT by Berger et al.(1972,p. 245).However,this

assumption has notbeen systematically tested,which has limited our under-

standing of the extent to which status beliefs transfer from individuals to pr

ducts. In addition to providing a test of the mechanism, we also develop a n

argument for why status beliefs transfer to products. We do so by investigat

how status beliefs shape evaluations of products in male- and female-typed

kets. Empirically, in many product markets, there are close associations bet

the productand its producer.Examples include scholarly work (Simcoe and

Waguespack 2011),cultural products(DiMaggio 1987) and products of

entrepreneurialendeavors (Thornton 1999).Understanding the mechanism of

status belief transfer will illuminate how status-based gender inequality is p

uated in these product markets.

Status Beliefs and the Evaluations of Products in Male- and Fem

Typed Markets

Conceptually, there are two types of status characteristics that have been s

to affect the evaluation of individuals:specificand diffuse (Correll and

Ridgeway 2006). Specific status characteristics, such as an occupational rol

possession ofspecific skillset,carry culturalexpectations for a well-defined

range of tasks, thus forming beliefs and aiding evaluations in a limited rang

contexts (Kunda and Spencer 2003). For instance, without specific informat

about an individual, we expect a software engineer to be competent at prog

ming a computer and a kindergarten teacher to be adept at teaching childre

the extent that those characteristics are relevant to the task at hand, specifi

tus characteristics influence performance expectations.

A Theory of Status Belief Transfer

Social Forces 98(2)550

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

eral expectations about the competence of members of a category. In the case

gender,widely shared beliefs continue to contain expectations thatmen are

more capable than women in a wide array of settings, independent of the speci

task at hand (Correll and Ridgeway 2006). In tandem, there are also specific ex

pectations thatmen are more capable atstereotypicalmasculine tasks (e.g.,

sports),while women are more capable atstereotypicalfeminine tasks (e.g.,

caretaking). Research has shown that these combinations of specific and diffus

status beliefs shape the evaluations ofmen and women in self-fulfilling ways

that,on balance,disadvantage women in various labor market outcomes (e.g.,

Castilla and Benard 2010;Chan and Anteby 2015;Goldin and Rouse 2000;

Steinpreis, Anders, and Ritzke 1999; Turco 2010).

We argue that these specific and diffuse status beliefs combine to produce re

ative devaluation of women’s products, leading to the mechanism of status bel

transfer. Concretely, we argue that the diffuse status beliefs associated with pro

ducer’sgendercombine with the specific statusbeliefsassociated with the

gender-typing of the product market, which jointly determine the overall evalua

tion of the product.When the producer’s gender aligns with the gender-typing

of the product market, such as men in male-typed product markets or women i

female-typed product markets, specific status beliefs will favor these producers

leading to higher performance expectations. However, when a product is made

by someone whose gender does not align with the gender-typing of the produc

market, specific status beliefs will be disadvantaging. In other words, specific st

tus beliefs vary with gender-typing of the market, whereas diffuse status beliefs

are consistent across contexts.

We differentiate between male-typed markets (i.e., those culturally associate

with men, such as sports markets) and female-typed markets (i.e., those cultur

ally associated with women, such as markets for children’s products) and make

predictions about each of these markets. First, in male-typed product markets,

man’s product will benefit both from the diffuse status belief that men are gene

ally more capable and from the specific status belief that men are better at ma

typed tasks,such as those required to make or consume male-typed products.

Both the specific and diffuse status characteristics are associated with more po

tive performance expectations for a man’s product than for a woman’s product

leading to more favorable assessments of men’s products. If the identical produ

were instead made by a woman,her product would be disadvantaged both by

the diffuse status belief that women are overall less capable and by the specific

status belief that women are not as good at the tasks required to produce male

typed products. This results in a lower evaluation for the same product made by

a woman than by a man in such markets.2

Hypothesis 1. In a male-typed market, a product made by a woman will

be evaluated more negatively than the same product made by a man.

In female-typed product markets, the diffuse expectation that men are generall

competent is at odds with the specific expectation that men are less skilled at t

tasks required to make or consume female-typed products. Based on the conte

Diffuse status characteristics, such as gender and race, carry broad and gen-

Gender Inequality in Product Markets551 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

gender,widely shared beliefs continue to contain expectations thatmen are

more capable than women in a wide array of settings, independent of the speci

task at hand (Correll and Ridgeway 2006). In tandem, there are also specific ex

pectations thatmen are more capable atstereotypicalmasculine tasks (e.g.,

sports),while women are more capable atstereotypicalfeminine tasks (e.g.,

caretaking). Research has shown that these combinations of specific and diffus

status beliefs shape the evaluations ofmen and women in self-fulfilling ways

that,on balance,disadvantage women in various labor market outcomes (e.g.,

Castilla and Benard 2010;Chan and Anteby 2015;Goldin and Rouse 2000;

Steinpreis, Anders, and Ritzke 1999; Turco 2010).

We argue that these specific and diffuse status beliefs combine to produce re

ative devaluation of women’s products, leading to the mechanism of status bel

transfer. Concretely, we argue that the diffuse status beliefs associated with pro

ducer’sgendercombine with the specific statusbeliefsassociated with the

gender-typing of the product market, which jointly determine the overall evalua

tion of the product.When the producer’s gender aligns with the gender-typing

of the product market, such as men in male-typed product markets or women i

female-typed product markets, specific status beliefs will favor these producers

leading to higher performance expectations. However, when a product is made

by someone whose gender does not align with the gender-typing of the produc

market, specific status beliefs will be disadvantaging. In other words, specific st

tus beliefs vary with gender-typing of the market, whereas diffuse status beliefs

are consistent across contexts.

We differentiate between male-typed markets (i.e., those culturally associate

with men, such as sports markets) and female-typed markets (i.e., those cultur

ally associated with women, such as markets for children’s products) and make

predictions about each of these markets. First, in male-typed product markets,

man’s product will benefit both from the diffuse status belief that men are gene

ally more capable and from the specific status belief that men are better at ma

typed tasks,such as those required to make or consume male-typed products.

Both the specific and diffuse status characteristics are associated with more po

tive performance expectations for a man’s product than for a woman’s product

leading to more favorable assessments of men’s products. If the identical produ

were instead made by a woman,her product would be disadvantaged both by

the diffuse status belief that women are overall less capable and by the specific

status belief that women are not as good at the tasks required to produce male

typed products. This results in a lower evaluation for the same product made by

a woman than by a man in such markets.2

Hypothesis 1. In a male-typed market, a product made by a woman will

be evaluated more negatively than the same product made by a man.

In female-typed product markets, the diffuse expectation that men are generall

competent is at odds with the specific expectation that men are less skilled at t

tasks required to make or consume female-typed products. Based on the conte

Diffuse status characteristics, such as gender and race, carry broad and gen-

Gender Inequality in Product Markets551 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

woman would be evaluated more positively than an identical product produ

by a man. However, even in female-typed markets, the diffuse status belief

women are less competent or worthy may persist, thus disadvantaging wom

products. This tension between diffuse and specific status beliefs complicate

prediction.Status characteristics theory has shown thatspecific status beliefs

have a bigger impact on performance expectations and evaluations than do

fuse status beliefs because specific status beliefs are more relevant to the t

hand (Correlland Ridgeway 2006).Thus, we expectthatthe advantage wo-

men’s products gain from specific status beliefs is larger than the advantag

men’s products gain from diffuse status beliefs.This means that women’s pro-

ducts should have an advantage over men’s products, but the magnitude of

advantageshould be smallerthan that experienced by men in male-typed

markets.

Hypothesis 2. In a female-typed market, a product made by a man will

be evaluated more negatively than the same product made by a woman

although the magnitude of the gap will be smaller than that found in a

male-typed market.

External Status Conferral

Sociologists have shown that status beliefs powerfully influence judgments

conditions ofuncertainty (Gould 2002;Podolny 1993;Salganik,Dodds,and

Watts 2006).Similarly,socialpsychologists have shown that stereotypes func-

tion as cognitive shortcuts when there is ambiguity about how to evaluate p

formances (cf. Correll 2017). Applying these insights to product evaluations

expect that if there is uncertainty about the quality of a product, individuals

on status beliefs to reduce the uncertainty, thereby forming evaluations tha

consistent with status beliefs associated with the product (Hypotheses 1 an

However, to the extent that there is a reduction in uncertainty about the pro

uct, we should expect the effects of status beliefs to diminish.

One way to reduce uncertainty around the quality of a product is external

tus conferral. Research shows that status conferral, such as winning an awa

receiving a certification, is associated with more positive evaluations becau

signalsexternaljudgmentsof quality (Podolny 1993;but seeKovács and

Sharkey 2014).However,externalstatus conferralcould have different effects

for products made by women and men. For example, recent empirical work

shown that there may be greater benefits from status conferral for low-statu

tors (e.g.,women) in the context of entrepreneurship (Thébaud 2015;Tinkler

et al. 2015). Building on this work, we explore how these predictions play ou

product markets and, importantly, how these predictions might differ depen

on the gender-typing of the product market.

We develop an argument for why there may be different effects of extern

status conferralby theorizing about how multiple pieces of status information

are synthesized when forming performance evaluations and expectations.We

of specific status beliefs, we might expect that female-typed products made

Social Forces 98(2)552

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

by a man. However, even in female-typed markets, the diffuse status belief

women are less competent or worthy may persist, thus disadvantaging wom

products. This tension between diffuse and specific status beliefs complicate

prediction.Status characteristics theory has shown thatspecific status beliefs

have a bigger impact on performance expectations and evaluations than do

fuse status beliefs because specific status beliefs are more relevant to the t

hand (Correlland Ridgeway 2006).Thus, we expectthatthe advantage wo-

men’s products gain from specific status beliefs is larger than the advantag

men’s products gain from diffuse status beliefs.This means that women’s pro-

ducts should have an advantage over men’s products, but the magnitude of

advantageshould be smallerthan that experienced by men in male-typed

markets.

Hypothesis 2. In a female-typed market, a product made by a man will

be evaluated more negatively than the same product made by a woman

although the magnitude of the gap will be smaller than that found in a

male-typed market.

External Status Conferral

Sociologists have shown that status beliefs powerfully influence judgments

conditions ofuncertainty (Gould 2002;Podolny 1993;Salganik,Dodds,and

Watts 2006).Similarly,socialpsychologists have shown that stereotypes func-

tion as cognitive shortcuts when there is ambiguity about how to evaluate p

formances (cf. Correll 2017). Applying these insights to product evaluations

expect that if there is uncertainty about the quality of a product, individuals

on status beliefs to reduce the uncertainty, thereby forming evaluations tha

consistent with status beliefs associated with the product (Hypotheses 1 an

However, to the extent that there is a reduction in uncertainty about the pro

uct, we should expect the effects of status beliefs to diminish.

One way to reduce uncertainty around the quality of a product is external

tus conferral. Research shows that status conferral, such as winning an awa

receiving a certification, is associated with more positive evaluations becau

signalsexternaljudgmentsof quality (Podolny 1993;but seeKovács and

Sharkey 2014).However,externalstatus conferralcould have different effects

for products made by women and men. For example, recent empirical work

shown that there may be greater benefits from status conferral for low-statu

tors (e.g.,women) in the context of entrepreneurship (Thébaud 2015;Tinkler

et al. 2015). Building on this work, we explore how these predictions play ou

product markets and, importantly, how these predictions might differ depen

on the gender-typing of the product market.

We develop an argument for why there may be different effects of extern

status conferralby theorizing about how multiple pieces of status information

are synthesized when forming performance evaluations and expectations.We

of specific status beliefs, we might expect that female-typed products made

Social Forces 98(2)552

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

attenuation principle,

additionalinformation about status has more impact on evaluations when the

information isnovel than when the information isredundant(Correll and

Ridgeway 2006).Additionalpositive status information (such as winning an

award) adds incremental value on performance expectations. Second, the incon

sistency principle predicts that a single piece of positive status information will

have a greater impact on the evaluative outcome if it is conventionally associat

with negative status information (Correll and Ridgeway 2006). Based on these

principles, we predict that a product made by a high-status actor will benefit les

from additional status than a product made by a low-status actor.

Applying these principles to a male-typed product market, products made by

men already benefit from both diffuse (being produced by a man) and specific

(men’s higher competency in a male-typed task)status beliefs.For a product

made by a man,winning an award adds more positive information to a field

already imbued with positive status. Thus, the attenuation principle leads us to

predict that the evaluation of a man’s product would be raised only slightly afte

winning an award. However, as argued in Hypothesis 1, a woman’s product in

a male-typed market typically experiences negative expectations because of bo

lower diffuse and specific status beliefs. Thus, for women’s products, the positiv

signal from winning an award should have a large positive increase on the eval

ation of her product,as predicted by the inconsistency principle.We predict a

gender-differentiated impact of status conferral on product evaluations.

Hypothesis 3. In a male-typed market, the evaluations of products made

by women willexperience greater gains from status conferralthan the

evaluations of products made by men will.

In female-typed product markets, we expect that status conferral will have a les

gender-differentiated effect on product evaluations. In these settings, specific a

diffuse status beliefs lead to inconsistent information about status, such that th

gain thatwomen experience in female-typed markets is relatively smallcom-

pared to the gain men experience in male-typed markets (Hypothesis 2).The

partially offsetting effects of diffuse and specific status beliefs mean that the le

of uncertainty about product quality should also be more equal for women and

men in female-typed markets compared to male-typed markets. Thus, we predi

that status conferralwill have a similar effect for men and women in female-

typed markets.

Hypothesis 4. In a female-typed market, status conferral will lead to pos-

itive improvements in the evaluations ofboth products made by men

and products made by women.

Product Knowledge

Anotherway thatuncertainty aboutproductquality could be reduced,and

thereforedecreasean evaluator’srelianceon statusbeliefs,is by assessing

whether the evaluator is knowledgeable about the product. Lack of knowledge

draw on two principles in SCT.First, according to the

Gender Inequality in Product Markets553 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

additionalinformation about status has more impact on evaluations when the

information isnovel than when the information isredundant(Correll and

Ridgeway 2006).Additionalpositive status information (such as winning an

award) adds incremental value on performance expectations. Second, the incon

sistency principle predicts that a single piece of positive status information will

have a greater impact on the evaluative outcome if it is conventionally associat

with negative status information (Correll and Ridgeway 2006). Based on these

principles, we predict that a product made by a high-status actor will benefit les

from additional status than a product made by a low-status actor.

Applying these principles to a male-typed product market, products made by

men already benefit from both diffuse (being produced by a man) and specific

(men’s higher competency in a male-typed task)status beliefs.For a product

made by a man,winning an award adds more positive information to a field

already imbued with positive status. Thus, the attenuation principle leads us to

predict that the evaluation of a man’s product would be raised only slightly afte

winning an award. However, as argued in Hypothesis 1, a woman’s product in

a male-typed market typically experiences negative expectations because of bo

lower diffuse and specific status beliefs. Thus, for women’s products, the positiv

signal from winning an award should have a large positive increase on the eval

ation of her product,as predicted by the inconsistency principle.We predict a

gender-differentiated impact of status conferral on product evaluations.

Hypothesis 3. In a male-typed market, the evaluations of products made

by women willexperience greater gains from status conferralthan the

evaluations of products made by men will.

In female-typed product markets, we expect that status conferral will have a les

gender-differentiated effect on product evaluations. In these settings, specific a

diffuse status beliefs lead to inconsistent information about status, such that th

gain thatwomen experience in female-typed markets is relatively smallcom-

pared to the gain men experience in male-typed markets (Hypothesis 2).The

partially offsetting effects of diffuse and specific status beliefs mean that the le

of uncertainty about product quality should also be more equal for women and

men in female-typed markets compared to male-typed markets. Thus, we predi

that status conferralwill have a similar effect for men and women in female-

typed markets.

Hypothesis 4. In a female-typed market, status conferral will lead to pos-

itive improvements in the evaluations ofboth products made by men

and products made by women.

Product Knowledge

Anotherway thatuncertainty aboutproductquality could be reduced,and

thereforedecreasean evaluator’srelianceon statusbeliefs,is by assessing

whether the evaluator is knowledgeable about the product. Lack of knowledge

draw on two principles in SCT.First, according to the

Gender Inequality in Product Markets553 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

’ uncertainty abouthow to

evaluate its quality. This prediction is based on research in consumer marke

which finds that there are differences in how experts and novices gather an

information about products, which results in meaningful differences in how

conduct product evaluations (Brucks 1985). The more knowledge the consu

possess, the more likely they are to make evaluations based on a larger num

of product attributes, and the less likely they are to rely on brand names, w

convey statusinformation (Bettman and Park 1980;Park and Lessig 1981;

Sujan 1985).

This literature also points to differences in how experts respond to atypica

features of a product. Knowledgeable consumers generate more product-re

thoughts and spend more time when evaluating atypicalproducts,a difference

not observed among the less-knowledgeable consumers (Sujan 1985). Relat

Peracchio and Tybout (1996) show that evaluators who possess a high level

knowledge are less affected by cultural schemas, such as status beliefs, com

with those who have a low level of knowledge. Since those with more knowl

are better able to attend to product features, they are less likely to need to

on status information as a signal of quality. While these papers theorize bro

about atypical attributes of products, we specifically focus on one type of at

cality, which is when a product is made by someone whose gender is incons

with the gender-typing of the particular product. We predict that those who

knowledge about a product will be more likely to discriminate based on the

der of the person producing the product.Therefore,as the evaluator’s levelof

knowledge about the product increases, the less likely the evaluator is to re

status beliefs about gender when evaluating the product.

Hypothesis 5. The lower the level of an evaluator’s product knowledge,

the greater the gender gap in product evaluation for a product made by

a producer whose gender is inconsistent with the gender-typing of the

market.

Overview of Studies

We conducted three experimental studies that test our arguments about ge

inequality in product markets. In Study 1, we demonstrate the pervasivenes

gender-typing in product markets by investigating people’s gendered perce

of a wide range of consumer products. Theoretically, Study 1 forms the basi

our argument that these specific status beliefs could operate in ways that d

vantage producers whose gender is inconsistent with these beliefs. Studies

3 ask participants to evaluate a product based on a product label, where sp

information was changed to manipulate the gender of the producer and whe

the product was conferred external status. These studies test the claim that

ple arrive at different evaluations because of the gender of the producer an

gender-typing of the market.We offer these studies as evidence of status belief

transferto product markets.In all studies,we recruited participantsfrom

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk).3

abouta product,conversely,increases evaluators

Social Forces 98(2)554

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

evaluate its quality. This prediction is based on research in consumer marke

which finds that there are differences in how experts and novices gather an

information about products, which results in meaningful differences in how

conduct product evaluations (Brucks 1985). The more knowledge the consu

possess, the more likely they are to make evaluations based on a larger num

of product attributes, and the less likely they are to rely on brand names, w

convey statusinformation (Bettman and Park 1980;Park and Lessig 1981;

Sujan 1985).

This literature also points to differences in how experts respond to atypica

features of a product. Knowledgeable consumers generate more product-re

thoughts and spend more time when evaluating atypicalproducts,a difference

not observed among the less-knowledgeable consumers (Sujan 1985). Relat

Peracchio and Tybout (1996) show that evaluators who possess a high level

knowledge are less affected by cultural schemas, such as status beliefs, com

with those who have a low level of knowledge. Since those with more knowl

are better able to attend to product features, they are less likely to need to

on status information as a signal of quality. While these papers theorize bro

about atypical attributes of products, we specifically focus on one type of at

cality, which is when a product is made by someone whose gender is incons

with the gender-typing of the particular product. We predict that those who

knowledge about a product will be more likely to discriminate based on the

der of the person producing the product.Therefore,as the evaluator’s levelof

knowledge about the product increases, the less likely the evaluator is to re

status beliefs about gender when evaluating the product.

Hypothesis 5. The lower the level of an evaluator’s product knowledge,

the greater the gender gap in product evaluation for a product made by

a producer whose gender is inconsistent with the gender-typing of the

market.

Overview of Studies

We conducted three experimental studies that test our arguments about ge

inequality in product markets. In Study 1, we demonstrate the pervasivenes

gender-typing in product markets by investigating people’s gendered perce

of a wide range of consumer products. Theoretically, Study 1 forms the basi

our argument that these specific status beliefs could operate in ways that d

vantage producers whose gender is inconsistent with these beliefs. Studies

3 ask participants to evaluate a product based on a product label, where sp

information was changed to manipulate the gender of the producer and whe

the product was conferred external status. These studies test the claim that

ple arrive at different evaluations because of the gender of the producer an

gender-typing of the market.We offer these studies as evidence of status belief

transferto product markets.In all studies,we recruited participantsfrom

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk).3

abouta product,conversely,increases evaluators

Social Forces 98(2)554

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

There is a lay perception that some products are more strongly associated with

femininity or with masculinity,such as baby products or golf clubs.However,

no sociologicalwork has systematically investigated the extentto which pro-

ducts are gender-typed. Study 1 demonstrates the pervasiveness of gender-typ

in productmarkets by testing for gender associations for 50 commonly used

consumer and household products. In order to compile an exhaustive list of pro

ducts, we collected the complete list of product categories on Jet.com (now par

of Walmart), a generalist online retailer that offers branded household and con-

sumer products. The complete list resulted in 362 products. After sorting alpha-

betically,we used a random number generator in the statisticalsoftware R to

choose fifty products for inclusion in our study.4

Participants and Task

We recruited 150 paid participants who were residing in the United States and

were at least twenty-one years old (see appendix A for a summary of partici-

pants’ demographic characteristics across three studies). We filtered participan

by gender before the survey started to achieve equal representation of men an

women, resulting in seventy-six women and seventy-four men. For each partici-

pant, the survey (created in Qualtrics) showed a random set of twenty products

out of fifty possible products,then asked the participant to rate the extent to

which the product was gender-typed. This resulted in each product having ~60

ratings ([150 participants× 20 product ratings/participant]/50 products).

Participants answered one question about each product’s overallfemininity or

masculinity: “Most people think (product) is _____” with a 7-point Likert scale

that ranged from “Very feminine” (7) to “Very masculine (1).” We used these

ratings to construct a variable called gender-typing. The means and 95 percent

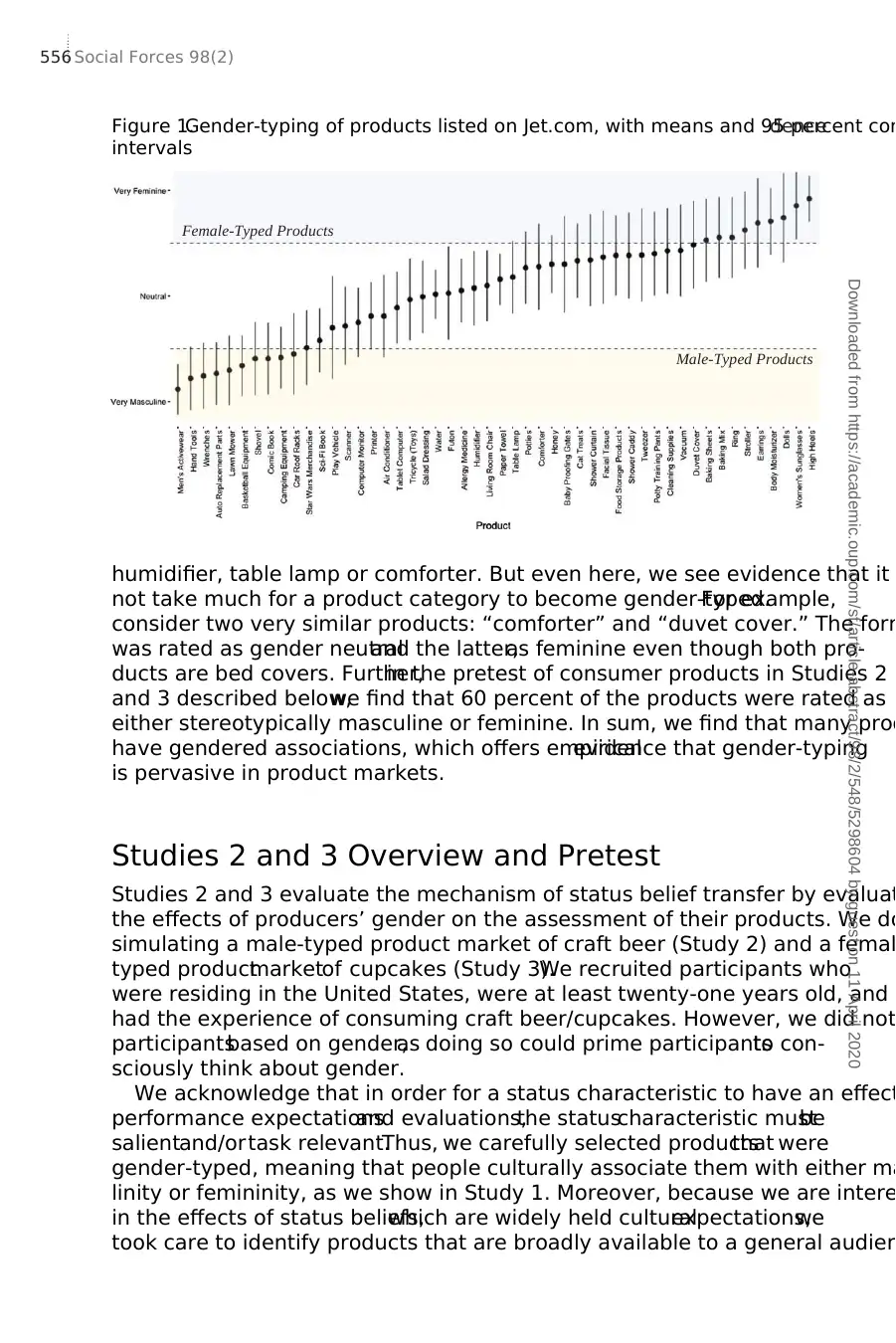

confidence intervals are shown in Figure1.

Results

We find that many products have stronger associations with one gender than th

other. As shown in figure 1, examples of strongly male-typed products (defined

as ≤3 on the 7-point Likert scale) include hand tools, lawn mower, shovel, bas-

ketballequipment,camping equipment,Sci-Fi books,and car roofranks (22

percent of allproducts surveyed).Examples of strongly female-typed products

(defined as ≥5 on the 7-pointLikert scale)include baking mix,ring, stroller,

body moisturizer, and high heels (18 percent of all products surveyed). Thus, w

see evidence of strong associations with one gender or another across in 40 pe

cent of product categories.While the percentage of products that are gender-

typed is quite high, we expect these effects would be even larger if we included

products that are more explicitly marketed to men or women (e.g.,razors tar-

geted at women vs. men; vitamin pills for men vs. women). There are also pro-

ducts that did not have strong associationswith either gender,such as

Study 1. Gender-Typing in Product Markets

Gender Inequality in Product Markets555 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

femininity or with masculinity,such as baby products or golf clubs.However,

no sociologicalwork has systematically investigated the extentto which pro-

ducts are gender-typed. Study 1 demonstrates the pervasiveness of gender-typ

in productmarkets by testing for gender associations for 50 commonly used

consumer and household products. In order to compile an exhaustive list of pro

ducts, we collected the complete list of product categories on Jet.com (now par

of Walmart), a generalist online retailer that offers branded household and con-

sumer products. The complete list resulted in 362 products. After sorting alpha-

betically,we used a random number generator in the statisticalsoftware R to

choose fifty products for inclusion in our study.4

Participants and Task

We recruited 150 paid participants who were residing in the United States and

were at least twenty-one years old (see appendix A for a summary of partici-

pants’ demographic characteristics across three studies). We filtered participan

by gender before the survey started to achieve equal representation of men an

women, resulting in seventy-six women and seventy-four men. For each partici-

pant, the survey (created in Qualtrics) showed a random set of twenty products

out of fifty possible products,then asked the participant to rate the extent to

which the product was gender-typed. This resulted in each product having ~60

ratings ([150 participants× 20 product ratings/participant]/50 products).

Participants answered one question about each product’s overallfemininity or

masculinity: “Most people think (product) is _____” with a 7-point Likert scale

that ranged from “Very feminine” (7) to “Very masculine (1).” We used these

ratings to construct a variable called gender-typing. The means and 95 percent

confidence intervals are shown in Figure1.

Results

We find that many products have stronger associations with one gender than th

other. As shown in figure 1, examples of strongly male-typed products (defined

as ≤3 on the 7-point Likert scale) include hand tools, lawn mower, shovel, bas-

ketballequipment,camping equipment,Sci-Fi books,and car roofranks (22

percent of allproducts surveyed).Examples of strongly female-typed products

(defined as ≥5 on the 7-pointLikert scale)include baking mix,ring, stroller,

body moisturizer, and high heels (18 percent of all products surveyed). Thus, w

see evidence of strong associations with one gender or another across in 40 pe

cent of product categories.While the percentage of products that are gender-

typed is quite high, we expect these effects would be even larger if we included

products that are more explicitly marketed to men or women (e.g.,razors tar-

geted at women vs. men; vitamin pills for men vs. women). There are also pro-

ducts that did not have strong associationswith either gender,such as

Study 1. Gender-Typing in Product Markets

Gender Inequality in Product Markets555 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

humidifier, table lamp or comforter. But even here, we see evidence that it

not take much for a product category to become gender-typed.For example,

consider two very similar products: “comforter” and “duvet cover.” The form

was rated as gender neutraland the latter,as feminine even though both pro-

ducts are bed covers. Further,in the pretest of consumer products in Studies 2

and 3 described below,we find that 60 percent of the products were rated as

either stereotypically masculine or feminine. In sum, we find that many prod

have gendered associations, which offers empiricalevidence that gender-typing

is pervasive in product markets.

Studies 2 and 3 Overview and Pretest

Studies 2 and 3 evaluate the mechanism of status belief transfer by evaluat

the effects of producers’ gender on the assessment of their products. We do

simulating a male-typed product market of craft beer (Study 2) and a femal

typed productmarketof cupcakes (Study 3).We recruited participants who

were residing in the United States, were at least twenty-one years old, and h

had the experience of consuming craft beer/cupcakes. However, we did not

participantsbased on gender,as doing so could prime participantsto con-

sciously think about gender.

We acknowledge that in order for a status characteristic to have an effect

performance expectationsand evaluations,the statuscharacteristic mustbe

salientand/ortask relevant.Thus, we carefully selected productsthat were

gender-typed, meaning that people culturally associate them with either ma

linity or femininity, as we show in Study 1. Moreover, because we are intere

in the effects of status beliefs,which are widely held culturalexpectations,we

took care to identify products that are broadly available to a general audien

Figure 1.Gender-typing of products listed on Jet.com, with means and 95 percent con

intervals

Female-Typed Products

Male-Typed Products

dence

Social Forces 98(2)556

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

not take much for a product category to become gender-typed.For example,

consider two very similar products: “comforter” and “duvet cover.” The form

was rated as gender neutraland the latter,as feminine even though both pro-

ducts are bed covers. Further,in the pretest of consumer products in Studies 2

and 3 described below,we find that 60 percent of the products were rated as

either stereotypically masculine or feminine. In sum, we find that many prod

have gendered associations, which offers empiricalevidence that gender-typing

is pervasive in product markets.

Studies 2 and 3 Overview and Pretest

Studies 2 and 3 evaluate the mechanism of status belief transfer by evaluat

the effects of producers’ gender on the assessment of their products. We do

simulating a male-typed product market of craft beer (Study 2) and a femal

typed productmarketof cupcakes (Study 3).We recruited participants who

were residing in the United States, were at least twenty-one years old, and h

had the experience of consuming craft beer/cupcakes. However, we did not

participantsbased on gender,as doing so could prime participantsto con-

sciously think about gender.

We acknowledge that in order for a status characteristic to have an effect

performance expectationsand evaluations,the statuscharacteristic mustbe

salientand/ortask relevant.Thus, we carefully selected productsthat were

gender-typed, meaning that people culturally associate them with either ma

linity or femininity, as we show in Study 1. Moreover, because we are intere

in the effects of status beliefs,which are widely held culturalexpectations,we

took care to identify products that are broadly available to a general audien

Figure 1.Gender-typing of products listed on Jet.com, with means and 95 percent con

intervals

Female-Typed Products

Male-Typed Products

dence

Social Forces 98(2)556

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

test (N = 50) that tested for the gender-typing of ten widely available and affor

able food products in a way that is similar to Study 1.5 The test identified four

products that were considered gender-neutral(dinner rolls,soup,spinach,and

coffee), three that were more male-typed (craft beer, chicken wings, and bacon

and three thatwere more female-typed (dietcola, cupcakes,and macarons).

Next, we narrowed down our choices by considering monthly consumption,

which ranged from 1 (never)to 5 (more than twenty timesper month).

Cupcakes and craft beer were consumed with similar frequency, with a mean o

1.88 for craft beer and 1.54 for cupcakes, a difference that is not statistically sig

nificant (t = −1.70, 95 percent CI = [−0.74, 0.06]). Further, we needed product

for which we could reasonably make cases for describing the identity of the pro

ducer (i.e.,brewer,baker),including their gender,withoutraising suspicion

about these studies’ focus on gender. Based on these criteria, we chose craft b

and cupcake for our two studies.6

Study 2. Male-Typed Product Market of Craft Beer

Procedure

Study 2 utilized a between-subject design where 272 participants were random

assigned to one of the four conditions, which crossed brewer’s gender (man or

woman) with externalstatus conferral(with or without status).To encourage

participants to pay attention to the information provided on the label,their

screen was locked for forty-five seconds before proceeding to the evaluation

task.

Manipulation

Brewer’s gender

We manipulated brewer’s gender by changing the name of the brewer on the

label. In the condition where the brewer was a woman, the labeldescribed the

producer as Sarah and included a brief description of her career in brewing. All

pronouns referred to Sarah as a she.In the condition where the brewer was a

man,the labelwas identicalexcept that the producer was David and allpro-

nouns referred to David as a he.

External status conferral

In the status conferral condition, the label described the beer as the winner of a

gold medal at the Great American Beer Festival. This is a prestigious award pre

sented annually by the Brewer’s Association,a nationaltrade association for

craft and home brewers. While we used a real award, the beer label described a

fictitious beer. In the no-status condition, there was no mention of an award. To

keep the text length similar to the status condition, we included some text abou

the kind of glassware that is appropriate for the beer. The suggested glassware

was described as a Pilsner glass, a common style of glassware.7

In order to select products that met these requirements, we conducted a pre-

Gender Inequality in Product Markets557 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

able food products in a way that is similar to Study 1.5 The test identified four

products that were considered gender-neutral(dinner rolls,soup,spinach,and

coffee), three that were more male-typed (craft beer, chicken wings, and bacon

and three thatwere more female-typed (dietcola, cupcakes,and macarons).

Next, we narrowed down our choices by considering monthly consumption,

which ranged from 1 (never)to 5 (more than twenty timesper month).

Cupcakes and craft beer were consumed with similar frequency, with a mean o

1.88 for craft beer and 1.54 for cupcakes, a difference that is not statistically sig

nificant (t = −1.70, 95 percent CI = [−0.74, 0.06]). Further, we needed product

for which we could reasonably make cases for describing the identity of the pro

ducer (i.e.,brewer,baker),including their gender,withoutraising suspicion

about these studies’ focus on gender. Based on these criteria, we chose craft b

and cupcake for our two studies.6

Study 2. Male-Typed Product Market of Craft Beer

Procedure

Study 2 utilized a between-subject design where 272 participants were random

assigned to one of the four conditions, which crossed brewer’s gender (man or

woman) with externalstatus conferral(with or without status).To encourage

participants to pay attention to the information provided on the label,their

screen was locked for forty-five seconds before proceeding to the evaluation

task.

Manipulation

Brewer’s gender

We manipulated brewer’s gender by changing the name of the brewer on the

label. In the condition where the brewer was a woman, the labeldescribed the

producer as Sarah and included a brief description of her career in brewing. All

pronouns referred to Sarah as a she.In the condition where the brewer was a

man,the labelwas identicalexcept that the producer was David and allpro-

nouns referred to David as a he.

External status conferral

In the status conferral condition, the label described the beer as the winner of a

gold medal at the Great American Beer Festival. This is a prestigious award pre

sented annually by the Brewer’s Association,a nationaltrade association for

craft and home brewers. While we used a real award, the beer label described a

fictitious beer. In the no-status condition, there was no mention of an award. To

keep the text length similar to the status condition, we included some text abou

the kind of glassware that is appropriate for the beer. The suggested glassware

was described as a Pilsner glass, a common style of glassware.7

In order to select products that met these requirements, we conducted a pre-

Gender Inequality in Product Markets557 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The dependent variable,overallevaluation,was constructed by creating a com-

posite of four items.The first item in the composite was taken from a question

where participants were asked how likely they would be to buy the beer, wh

had answer choices ranging from “very unlikely” (1) to “very likely” (7).The

mean was 4.67 (SD = 1.42). The second item was how much the participant

willing to pay for a pint of this beer at a brewpub. Participants could enter a

amount but if they recorded a value higher than $10, which is unusually hig

a pint of beer, the survey alerted the respondent to reconsider. The average

ingness to pay was $4.53 (SD = 1.84), with a minimum of $0.00 and a maxi

of $11.00.Third, we measured the participants’expected taste.Participants re-

sponded to,“overall,what do you think the beer willtaste like?” with answer

choices ranging between “terrible” (1) and “excellent” (7) (mean = 4.90,SD =

1.02).Lastly,we measured expected quality with answer choices ranging from

“lowest quality” (1) to “highest quality” (7),which had the mean of 5.20 and

standard deviation of 1.21. To construct the composite variable, overall eva

tion, we first standardized each of these four variables to a standard norma

bution, then averaged these z-scores. Cronbach’s alpha for the measure is 0

Evaluator’s Product Knowledge

We draw on the literature on consumer product knowledge to construct our

uct knowledge measures. This literature classifies product knowledge as ob

and subjective knowledge (Carlson et al.2009).Objective knowledge describes

the actualinformation that consumers possess,while subjective knowledge de-

scribes consumers’perceptions of their own knowledge.We mirrored a widely

cited measurement methodology to measure both dimensions of product kn

edge (Mitchelland Dacin 1996). The first question was, “in your opinion,how

would you evaluate your level of expertise in craft beer?” and the answer ch

ranged between “no expertise” (1) to “connoisseur” (5), and the mean was

(SD = 1.07). This measure captures one’s own assessment of expertize—su

knowledge (Carlson et al. 2009). We also asked about their familiarity with c

beer in two ways. First we asked whether the participant had ever been call

“beer snob,” a term in the craft beer community to describe those who are

edgeable about craft beer. Twenty-three percent of the participants reporte

they had been called a beer snob.The second question was,“on average,how

many days in a week do you drink beer?” and answer choices ranged from 0

days.The mean was 2.13 days a week (SD = 1.67).This measure was useful

because consumption frequency increases familiarity with the product and f

iarity is correlated with consumer knowledge (Alba and Hutchinson 1987; Pa

and Lessig 1981).

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents summary statistics for the four conditions and the results o

paired t tests that compare the overall evaluations of man-made and woma

Dependent Variable

Social Forces 98(2)558

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

posite of four items.The first item in the composite was taken from a question

where participants were asked how likely they would be to buy the beer, wh

had answer choices ranging from “very unlikely” (1) to “very likely” (7).The

mean was 4.67 (SD = 1.42). The second item was how much the participant

willing to pay for a pint of this beer at a brewpub. Participants could enter a

amount but if they recorded a value higher than $10, which is unusually hig

a pint of beer, the survey alerted the respondent to reconsider. The average

ingness to pay was $4.53 (SD = 1.84), with a minimum of $0.00 and a maxi

of $11.00.Third, we measured the participants’expected taste.Participants re-

sponded to,“overall,what do you think the beer willtaste like?” with answer

choices ranging between “terrible” (1) and “excellent” (7) (mean = 4.90,SD =

1.02).Lastly,we measured expected quality with answer choices ranging from

“lowest quality” (1) to “highest quality” (7),which had the mean of 5.20 and

standard deviation of 1.21. To construct the composite variable, overall eva

tion, we first standardized each of these four variables to a standard norma

bution, then averaged these z-scores. Cronbach’s alpha for the measure is 0

Evaluator’s Product Knowledge

We draw on the literature on consumer product knowledge to construct our

uct knowledge measures. This literature classifies product knowledge as ob

and subjective knowledge (Carlson et al.2009).Objective knowledge describes

the actualinformation that consumers possess,while subjective knowledge de-

scribes consumers’perceptions of their own knowledge.We mirrored a widely

cited measurement methodology to measure both dimensions of product kn

edge (Mitchelland Dacin 1996). The first question was, “in your opinion,how

would you evaluate your level of expertise in craft beer?” and the answer ch

ranged between “no expertise” (1) to “connoisseur” (5), and the mean was

(SD = 1.07). This measure captures one’s own assessment of expertize—su

knowledge (Carlson et al. 2009). We also asked about their familiarity with c

beer in two ways. First we asked whether the participant had ever been call

“beer snob,” a term in the craft beer community to describe those who are

edgeable about craft beer. Twenty-three percent of the participants reporte

they had been called a beer snob.The second question was,“on average,how

many days in a week do you drink beer?” and answer choices ranged from 0

days.The mean was 2.13 days a week (SD = 1.67).This measure was useful

because consumption frequency increases familiarity with the product and f

iarity is correlated with consumer knowledge (Alba and Hutchinson 1987; Pa

and Lessig 1981).

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents summary statistics for the four conditions and the results o

paired t tests that compare the overall evaluations of man-made and woma

Dependent Variable

Social Forces 98(2)558

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

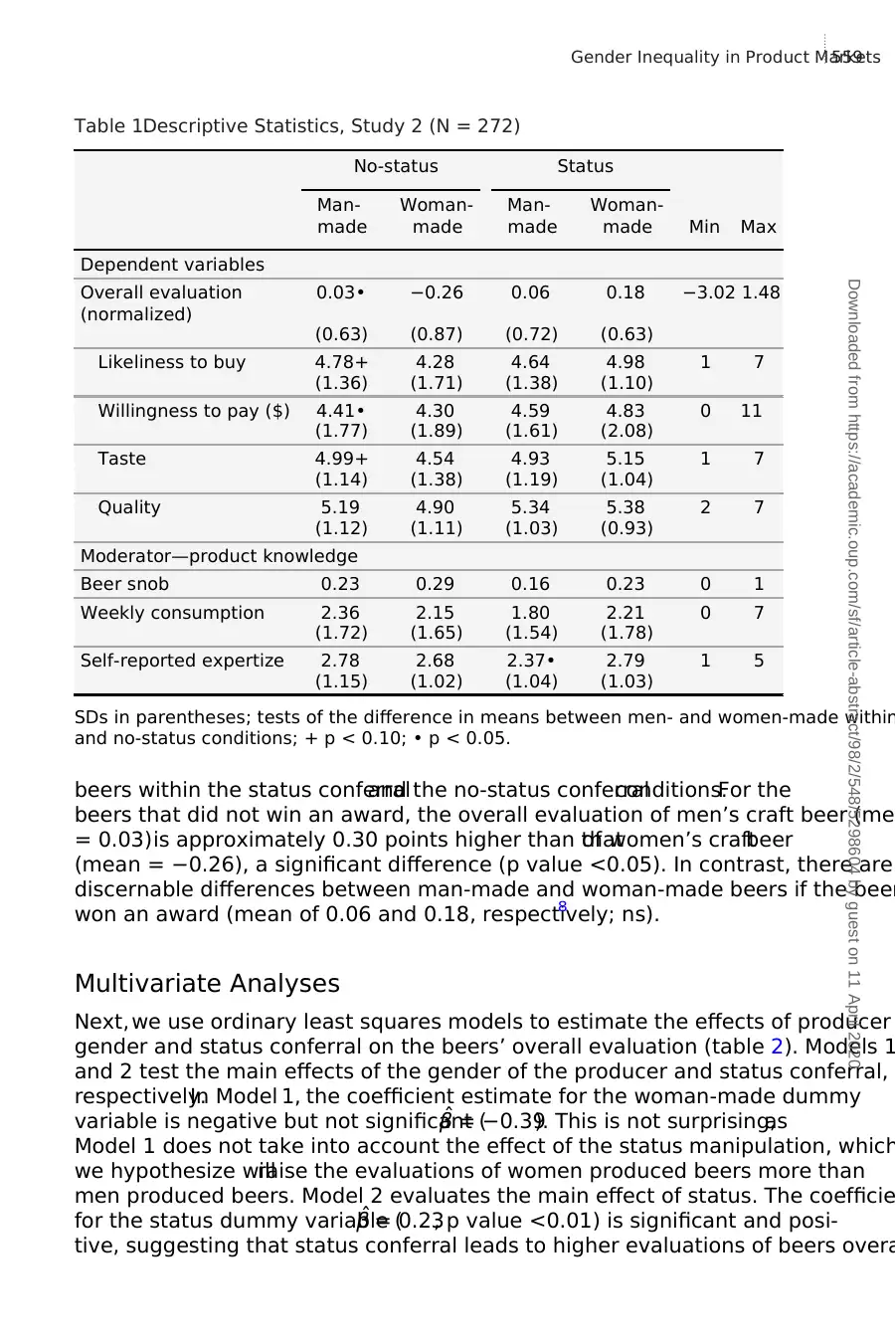

beers within the status conferraland the no-status conferralconditions.For the

beers that did not win an award, the overall evaluation of men’s craft beer (mea

= 0.03)is approximately 0.30 points higher than thatof women’s craftbeer

(mean = −0.26), a significant difference (p value <0.05). In contrast, there are

discernable differences between man-made and woman-made beers if the beer

won an award (mean of 0.06 and 0.18, respectively; ns).8

Multivariate Analyses

Next, we use ordinary least squares models to estimate the effects of producer

gender and status conferral on the beers’ overall evaluation (table 2). Models 1

and 2 test the main effects of the gender of the producer and status conferral,

respectively.In Model 1, the coefficient estimate for the woman-made dummy

variable is negative but not significant (βˆ = −0.39). This is not surprising,as

Model 1 does not take into account the effect of the status manipulation, which

we hypothesize willraise the evaluations of women produced beers more than

men produced beers. Model 2 evaluates the main effect of status. The coefficie

for the status dummy variable (βˆ = 0.23, p value <0.01) is significant and posi-

tive, suggesting that status conferral leads to higher evaluations of beers overa

No-status Status

Man-

made

Woman-

made

Man-

made

Woman-

made Min Max

Dependent variables

Overall evaluation

(normalized)

0.03• −0.26 0.06 0.18 −3.02 1.48

(0.63) (0.87) (0.72) (0.63)

Likeliness to buy 4.78+ 4.28 4.64 4.98 1 7

(1.36) (1.71) (1.38) (1.10)

Willingness to pay ($) 4.41• 4.30 4.59 4.83 0 11

(1.77) (1.89) (1.61) (2.08)

Taste 4.99+ 4.54 4.93 5.15 1 7

(1.14) (1.38) (1.19) (1.04)

Quality 5.19 4.90 5.34 5.38 2 7

(1.12) (1.11) (1.03) (0.93)

Moderator—product knowledge

Beer snob 0.23 0.29 0.16 0.23 0 1

Weekly consumption 2.36 2.15 1.80 2.21 0 7

(1.72) (1.65) (1.54) (1.78)

Self-reported expertize 2.78 2.68 2.37• 2.79 1 5

(1.15) (1.02) (1.04) (1.03)

SDs in parentheses; tests of the difference in means between men- and women-made within

and no-status conditions; + p < 0.10; • p < 0.05.

Table 1.Descriptive Statistics, Study 2 (N = 272)

Gender Inequality in Product Markets559 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/2/548/5298604 by guest on 11 April 2020

beers that did not win an award, the overall evaluation of men’s craft beer (mea

= 0.03)is approximately 0.30 points higher than thatof women’s craftbeer

(mean = −0.26), a significant difference (p value <0.05). In contrast, there are

discernable differences between man-made and woman-made beers if the beer

won an award (mean of 0.06 and 0.18, respectively; ns).8

Multivariate Analyses

Next, we use ordinary least squares models to estimate the effects of producer

gender and status conferral on the beers’ overall evaluation (table 2). Models 1

and 2 test the main effects of the gender of the producer and status conferral,

respectively.In Model 1, the coefficient estimate for the woman-made dummy

variable is negative but not significant (βˆ = −0.39). This is not surprising,as

Model 1 does not take into account the effect of the status manipulation, which

we hypothesize willraise the evaluations of women produced beers more than

men produced beers. Model 2 evaluates the main effect of status. The coefficie

for the status dummy variable (βˆ = 0.23, p value <0.01) is significant and posi-

tive, suggesting that status conferral leads to higher evaluations of beers overa

No-status Status

Man-

made

Woman-

made

Man-

made

Woman-

made Min Max

Dependent variables

Overall evaluation

(normalized)

0.03• −0.26 0.06 0.18 −3.02 1.48

(0.63) (0.87) (0.72) (0.63)

Likeliness to buy 4.78+ 4.28 4.64 4.98 1 7

(1.36) (1.71) (1.38) (1.10)

Willingness to pay ($) 4.41• 4.30 4.59 4.83 0 11

(1.77) (1.89) (1.61) (2.08)

Taste 4.99+ 4.54 4.93 5.15 1 7

(1.14) (1.38) (1.19) (1.04)

Quality 5.19 4.90 5.34 5.38 2 7

(1.12) (1.11) (1.03) (0.93)

Moderator—product knowledge

Beer snob 0.23 0.29 0.16 0.23 0 1

Weekly consumption 2.36 2.15 1.80 2.21 0 7

(1.72) (1.65) (1.54) (1.78)

Self-reported expertize 2.78 2.68 2.37• 2.79 1 5

(1.15) (1.02) (1.04) (1.03)