GEOG 1191 Assignment: Exploring Perception and Land Use Decisions

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|6

|2164

|14

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This assignment, for GEOG 1191, explores the multifaceted relationship between human perception and land use decisions. Question 1 focuses on perceptions of ecologically sustainable forestry and community safety in Kelowna, analyzing different perspectives and their impact on wildfire risk management. Question 2 examines the influence of mental maps on land use choices, delving into how these mental representations affect society. Question 3 involves a survey of ten individuals to assess their environmental preferences for different regions in British Columbia, comparing these preferences with the concept of mental maps and the 'View from California'. The assignment requires critical analysis, data presentation, and reflection on the interplay of individual perceptions, regional characteristics, and land use planning, using concepts from the course textbook and provided articles. The goal is to understand how perception shapes the way we view and interact with the environment.

Question 1 relates to the section on how people perceive, which is covered in

Unit 2, Module 5.

Read the article “Forest as hazard, forest as victim: Community perspectives

and disaster mitigation in the aftermath of Kelowna’s 2003 wildfires”

(Goemans & Ballamingie, 2012) and answer the following questions: (20

marks total)

1. The authors identify three different perceptions towards ecologically

sustainable forestry and community safety. In a paragraph each,

identify and describe each. Why do the perceptions vary? (5 marks)

2. The authors describe an evolution of geographic thought around

human perception of natural hazards that accounts for our changing

ideas about society’s vulnerability. Briefly outline the key points in this

discussion. Which approach in Module 5 evaluates human adjustment

to the natural environment? (5 marks)

3. If your job was to plan urban-rural-natural land use in Kelowna and the

surrounding areas, how do you think your understanding of these

different perceptions would help you in developing different

approaches with which to educate people on fire risk and

management? Identify and briefly discuss three ways that you could

educate people (keeping in mind their different perceptions) on what

they can do to protect their property and community from wildfire.

Your answer should be approximately 500 words (two double-spaced

pages). (10 marks)

Question 2:

One of the themes around perception is that perception varies with

knowledge and is closely related to the cultural and social considerations of

the individual who holds a particular mental “picture”. Mental maps of

geographic areas are heavily influenced by one’s perception.

Six ways that mental maps can be important and impact society include:

1. Mental images change in a shrinking world, and we become

increasingly aware of this when something happens in one place that

affects us all.

2. Mental images around mobility or population movement

3. Perceptions of a few can impact many.

4. People in power can have distorted mental maps/images.

5. Mental maps change.

6. Mental maps explore what we think of unknown areas and what we

don’t know.

Unit 2, Module 5.

Read the article “Forest as hazard, forest as victim: Community perspectives

and disaster mitigation in the aftermath of Kelowna’s 2003 wildfires”

(Goemans & Ballamingie, 2012) and answer the following questions: (20

marks total)

1. The authors identify three different perceptions towards ecologically

sustainable forestry and community safety. In a paragraph each,

identify and describe each. Why do the perceptions vary? (5 marks)

2. The authors describe an evolution of geographic thought around

human perception of natural hazards that accounts for our changing

ideas about society’s vulnerability. Briefly outline the key points in this

discussion. Which approach in Module 5 evaluates human adjustment

to the natural environment? (5 marks)

3. If your job was to plan urban-rural-natural land use in Kelowna and the

surrounding areas, how do you think your understanding of these

different perceptions would help you in developing different

approaches with which to educate people on fire risk and

management? Identify and briefly discuss three ways that you could

educate people (keeping in mind their different perceptions) on what

they can do to protect their property and community from wildfire.

Your answer should be approximately 500 words (two double-spaced

pages). (10 marks)

Question 2:

One of the themes around perception is that perception varies with

knowledge and is closely related to the cultural and social considerations of

the individual who holds a particular mental “picture”. Mental maps of

geographic areas are heavily influenced by one’s perception.

Six ways that mental maps can be important and impact society include:

1. Mental images change in a shrinking world, and we become

increasingly aware of this when something happens in one place that

affects us all.

2. Mental images around mobility or population movement

3. Perceptions of a few can impact many.

4. People in power can have distorted mental maps/images.

5. Mental maps change.

6. Mental maps explore what we think of unknown areas and what we

don’t know.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

In an essay of approximately 750 words (~3 pages double-spaced), discuss

which one of the six, in your opinion, has the greatest influence on land use

decision making. (20 marks)

Question 3:

For this question, you will need the help of at least ten people. You will only

need each person’s help for about five minutes, so you should be able to

persuade friends or people you know to help you. If you cannot come up with

ten people, get as many as you can. They are going to help you explore the

realm of environmental preferences that we discussed in the unit.

Follow the step-by-step procedure, and answer the questions as you come to

them: (60 marks)

Step 1:

Prepare a list of locations (see below) on paper or a digital file. Select at least

ten people who will participate in this exercise. You may approach them one

at a time or in groups. (Steps 2 through 4 are worth 20 marks collectively;

step 5 is worth 40 marks)

Step 2:

Provide each of the ten people with a list of the following regions in British

Columbia, and ask them to rank these regions in terms of their preferability

as places in which to live.

Make sure that each person assigns the number 12 to the least desirable

region and 1 to the most desirable place to live.

The regions are:

A. Greater Victoria

B. The rest of Vancouver Island

C. Greater Vancouver

D. The Fraser Valley

E. The Okanagan Valley

F. The Kootenays

G. Kamloops/Thompson

H. The Sunshine Coast/Sechelt Peninsula

I. The Central Interior

J. The Peace River District

K. The Northwest

L. The North

which one of the six, in your opinion, has the greatest influence on land use

decision making. (20 marks)

Question 3:

For this question, you will need the help of at least ten people. You will only

need each person’s help for about five minutes, so you should be able to

persuade friends or people you know to help you. If you cannot come up with

ten people, get as many as you can. They are going to help you explore the

realm of environmental preferences that we discussed in the unit.

Follow the step-by-step procedure, and answer the questions as you come to

them: (60 marks)

Step 1:

Prepare a list of locations (see below) on paper or a digital file. Select at least

ten people who will participate in this exercise. You may approach them one

at a time or in groups. (Steps 2 through 4 are worth 20 marks collectively;

step 5 is worth 40 marks)

Step 2:

Provide each of the ten people with a list of the following regions in British

Columbia, and ask them to rank these regions in terms of their preferability

as places in which to live.

Make sure that each person assigns the number 12 to the least desirable

region and 1 to the most desirable place to live.

The regions are:

A. Greater Victoria

B. The rest of Vancouver Island

C. Greater Vancouver

D. The Fraser Valley

E. The Okanagan Valley

F. The Kootenays

G. Kamloops/Thompson

H. The Sunshine Coast/Sechelt Peninsula

I. The Central Interior

J. The Peace River District

K. The Northwest

L. The North

Do not allow the respondents to work together or to listen in on or see each

other’s responses. If they ask you what are the boundaries of the various

regions, tell them to guess (this in itself might be an interesting indication of

your respondents’ mental maps of the regions and their characteristics).

This will result in ten lists, each with the 12 locations and numbers indicating

preferences from 1 to 12. You will provide the raw numbers for this exercise

as part of the table you hand in (see Step 4, below). (5 marks)

Step 3:

Next, ask the respondents to indicate if he or she knows each of the regions

well, a little, or not at all. Each time a participant indicates that they know a

place “well”, assign a score of 3 for that location. Each time a participant

indicates they know a place “a little”, assign a score of 2 for that location.

And finally, assign a score of 1 for each location that is not known at all. You

will provide the raw numbers as part of the table that you hand in (see

Step 4, below). (5 marks)

Step 4:

Calculate, and present in two tables, the data from above.

The first table presents the results from participants about their most to least

desirable places to live (Step 2): (5 marks)

Write the names of participants across one axis and the location

names across another. In each corresponding square or cell, put in the

raw numbers (1–12) assigned by each participant.

Aggregate (total) the answers for the 12 locations by adding a “Total”

column to your table. Place the total for each location in that column.

To do this, add the sum of the preferences for each region and rank

the regions from the lowest to the highest preference score. The

region with the smallest aggregate score is the most desirable as a

place to live.

Change the order of the above 12 locations in your table so that the

most desirable place appears first in your table and the least desirable

place appears last. These placings are based on the aggregate totals

that you calculated.

The second table presents the results from Step 3, when you asked the

respondents to indicate how well they know each place: (5 marks)

Write the names of the participants across one axis and the location

names across another. In each corresponding square or cell, put in the

other’s responses. If they ask you what are the boundaries of the various

regions, tell them to guess (this in itself might be an interesting indication of

your respondents’ mental maps of the regions and their characteristics).

This will result in ten lists, each with the 12 locations and numbers indicating

preferences from 1 to 12. You will provide the raw numbers for this exercise

as part of the table you hand in (see Step 4, below). (5 marks)

Step 3:

Next, ask the respondents to indicate if he or she knows each of the regions

well, a little, or not at all. Each time a participant indicates that they know a

place “well”, assign a score of 3 for that location. Each time a participant

indicates they know a place “a little”, assign a score of 2 for that location.

And finally, assign a score of 1 for each location that is not known at all. You

will provide the raw numbers as part of the table that you hand in (see

Step 4, below). (5 marks)

Step 4:

Calculate, and present in two tables, the data from above.

The first table presents the results from participants about their most to least

desirable places to live (Step 2): (5 marks)

Write the names of participants across one axis and the location

names across another. In each corresponding square or cell, put in the

raw numbers (1–12) assigned by each participant.

Aggregate (total) the answers for the 12 locations by adding a “Total”

column to your table. Place the total for each location in that column.

To do this, add the sum of the preferences for each region and rank

the regions from the lowest to the highest preference score. The

region with the smallest aggregate score is the most desirable as a

place to live.

Change the order of the above 12 locations in your table so that the

most desirable place appears first in your table and the least desirable

place appears last. These placings are based on the aggregate totals

that you calculated.

The second table presents the results from Step 3, when you asked the

respondents to indicate how well they know each place: (5 marks)

Write the names of the participants across one axis and the location

names across another. In each corresponding square or cell, put in the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

number that indicates how well they know a location (1 for “not at all”,

2 for “a little”, or 3 for “well”).

Add a “Total” column and for each of the 12 locations, total up the

scores that match whether participants felt they know a place well, a

little, or not at all.

Present your totals in a column and order the locations from best

known (top) to least known (bottom). (Note: Your table may have

“ties”. This is okay. Just group all the well-known, little-known, and

unknown locations together.

In this table, the locations with the highest scores are the ones that

are known the best.

Step 5:

Write answers for each of the following questions:

A. What areas are ranked by the entire group as being the four most

preferable regions in which to live? (Identify these areas clearly.).

What might be the reasons for these preferences? Include ideas based

on your opinion and building on the concepts from pages 36–37 in

your textbook. Reviewing the concept region on pages 36–37 of your

textbook will provide some theoretical background. In particular,

consider the differences between regionalization, regionalism, and

vernacular regions, and the roles that these views may play in helping

you understand the patterns for preferences that you are seeing in

your data.

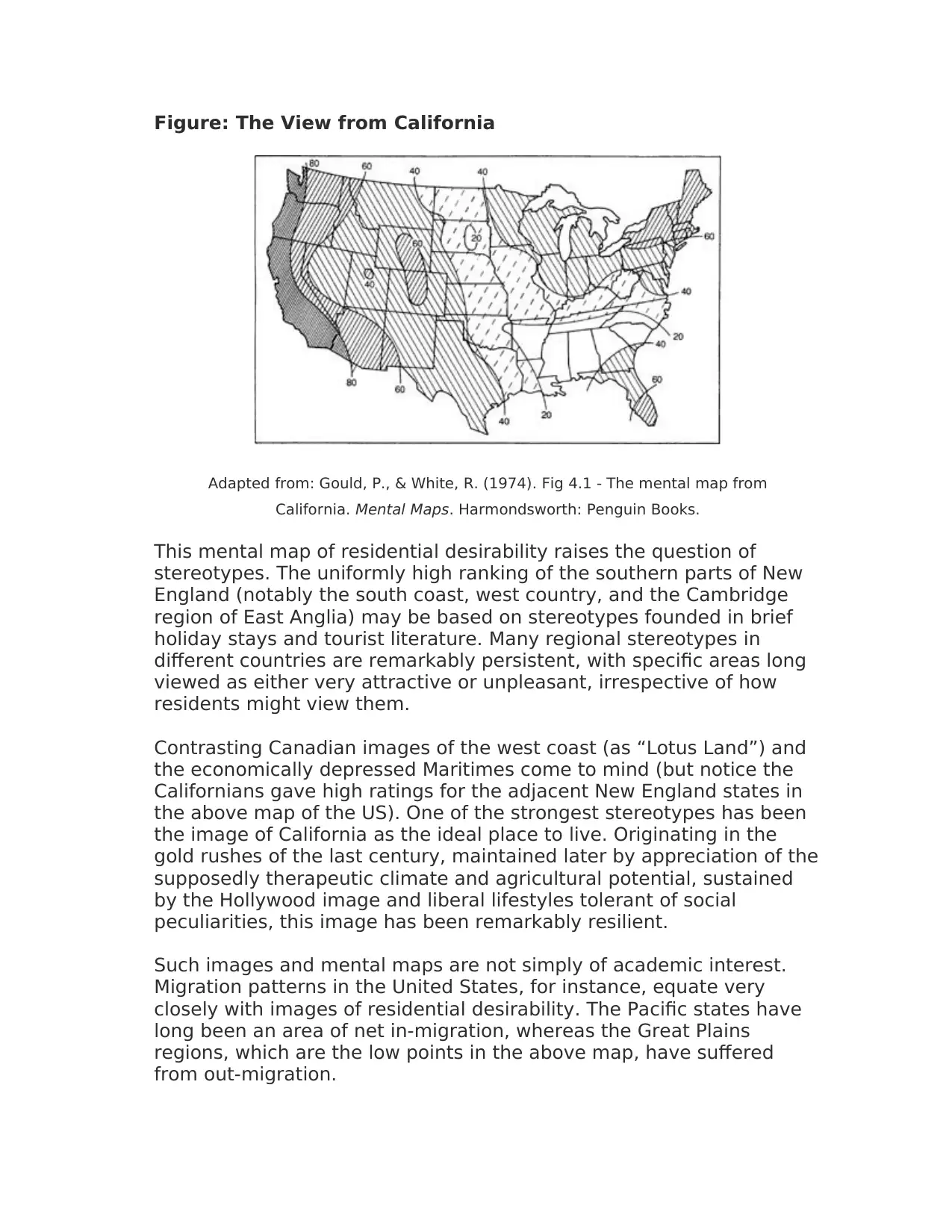

For the third part of Part A, consider the map below titled “The View

from California”. The map shows patterns of residential desirability

using zones indicated by numbers. So, on this map, the zone with a

value of 80 is the most desirable, and places to the left of the 80 line

indicates this zone. For example, levels of residential desirability are

high on the west coast, extending from California to Washington State.

(If you are not sure where California and Washington State are

located, use a search engine to consult a map of the United States.)

Moving eastwards from the west coast, desirability sinks to a low in

Utah (where the zone is 40), but then rises to a plateau in Colorado

(where the zone is 60). From here eastwards, there is a gradual

decline to the low point of the Dakotas, but at this point the essentially

west-east trend changes.

From about the one hundred degree meridian, the trend shifts to a

north-south one. Values rise towards the northeast, but decline to the

south (with the exception of Florida).

2 for “a little”, or 3 for “well”).

Add a “Total” column and for each of the 12 locations, total up the

scores that match whether participants felt they know a place well, a

little, or not at all.

Present your totals in a column and order the locations from best

known (top) to least known (bottom). (Note: Your table may have

“ties”. This is okay. Just group all the well-known, little-known, and

unknown locations together.

In this table, the locations with the highest scores are the ones that

are known the best.

Step 5:

Write answers for each of the following questions:

A. What areas are ranked by the entire group as being the four most

preferable regions in which to live? (Identify these areas clearly.).

What might be the reasons for these preferences? Include ideas based

on your opinion and building on the concepts from pages 36–37 in

your textbook. Reviewing the concept region on pages 36–37 of your

textbook will provide some theoretical background. In particular,

consider the differences between regionalization, regionalism, and

vernacular regions, and the roles that these views may play in helping

you understand the patterns for preferences that you are seeing in

your data.

For the third part of Part A, consider the map below titled “The View

from California”. The map shows patterns of residential desirability

using zones indicated by numbers. So, on this map, the zone with a

value of 80 is the most desirable, and places to the left of the 80 line

indicates this zone. For example, levels of residential desirability are

high on the west coast, extending from California to Washington State.

(If you are not sure where California and Washington State are

located, use a search engine to consult a map of the United States.)

Moving eastwards from the west coast, desirability sinks to a low in

Utah (where the zone is 40), but then rises to a plateau in Colorado

(where the zone is 60). From here eastwards, there is a gradual

decline to the low point of the Dakotas, but at this point the essentially

west-east trend changes.

From about the one hundred degree meridian, the trend shifts to a

north-south one. Values rise towards the northeast, but decline to the

south (with the exception of Florida).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Figure: The View from California

Adapted from: Gould, P., & White, R. (1974). Fig 4.1 - The mental map from

California. Mental Maps. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

This mental map of residential desirability raises the question of

stereotypes. The uniformly high ranking of the southern parts of New

England (notably the south coast, west country, and the Cambridge

region of East Anglia) may be based on stereotypes founded in brief

holiday stays and tourist literature. Many regional stereotypes in

different countries are remarkably persistent, with specific areas long

viewed as either very attractive or unpleasant, irrespective of how

residents might view them.

Contrasting Canadian images of the west coast (as “Lotus Land”) and

the economically depressed Maritimes come to mind (but notice the

Californians gave high ratings for the adjacent New England states in

the above map of the US). One of the strongest stereotypes has been

the image of California as the ideal place to live. Originating in the

gold rushes of the last century, maintained later by appreciation of the

supposedly therapeutic climate and agricultural potential, sustained

by the Hollywood image and liberal lifestyles tolerant of social

peculiarities, this image has been remarkably resilient.

Such images and mental maps are not simply of academic interest.

Migration patterns in the United States, for instance, equate very

closely with images of residential desirability. The Pacific states have

long been an area of net in-migration, whereas the Great Plains

regions, which are the low points in the above map, have suffered

from out-migration.

Adapted from: Gould, P., & White, R. (1974). Fig 4.1 - The mental map from

California. Mental Maps. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

This mental map of residential desirability raises the question of

stereotypes. The uniformly high ranking of the southern parts of New

England (notably the south coast, west country, and the Cambridge

region of East Anglia) may be based on stereotypes founded in brief

holiday stays and tourist literature. Many regional stereotypes in

different countries are remarkably persistent, with specific areas long

viewed as either very attractive or unpleasant, irrespective of how

residents might view them.

Contrasting Canadian images of the west coast (as “Lotus Land”) and

the economically depressed Maritimes come to mind (but notice the

Californians gave high ratings for the adjacent New England states in

the above map of the US). One of the strongest stereotypes has been

the image of California as the ideal place to live. Originating in the

gold rushes of the last century, maintained later by appreciation of the

supposedly therapeutic climate and agricultural potential, sustained

by the Hollywood image and liberal lifestyles tolerant of social

peculiarities, this image has been remarkably resilient.

Such images and mental maps are not simply of academic interest.

Migration patterns in the United States, for instance, equate very

closely with images of residential desirability. The Pacific states have

long been an area of net in-migration, whereas the Great Plains

regions, which are the low points in the above map, have suffered

from out-migration.

Although the figure is at a different scale than the province of BC (the

regions you surveyed), do you see any patterns or similarities in the

concepts between “The View from California” (as presented above and

from your own knowledge) and your analyzed data? Are there zones or

areas in BC that are more desirable to live than others? Is this

reflected in the data you collected? Do you think all people who live in

BC would share this view? You are expected to discuss the ideas of

differences in climate, land use (agriculture, residential, etc.), and

economic development (related to migration), as described above.

(Total for Part A: 20 marks)

Reference: Gould, P. R. (1966). “Some Implications of Mental

Maps.” Position Paper #9.

B. Does the pattern of preferences shown by your respondents surprise

you? If so, how? Why did the pattern surprise you? If not, why not?

Would you have expressed the same preferences? (10 marks)

C. Is there any relationship between the respondents’ preferences for

regions and their familiarity with those regions? Use a graphic or

tabular way to show if there is such a relationship. (10 marks)

regions you surveyed), do you see any patterns or similarities in the

concepts between “The View from California” (as presented above and

from your own knowledge) and your analyzed data? Are there zones or

areas in BC that are more desirable to live than others? Is this

reflected in the data you collected? Do you think all people who live in

BC would share this view? You are expected to discuss the ideas of

differences in climate, land use (agriculture, residential, etc.), and

economic development (related to migration), as described above.

(Total for Part A: 20 marks)

Reference: Gould, P. R. (1966). “Some Implications of Mental

Maps.” Position Paper #9.

B. Does the pattern of preferences shown by your respondents surprise

you? If so, how? Why did the pattern surprise you? If not, why not?

Would you have expressed the same preferences? (10 marks)

C. Is there any relationship between the respondents’ preferences for

regions and their familiarity with those regions? Use a graphic or

tabular way to show if there is such a relationship. (10 marks)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 6

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.