Implementing Effective Vaccination Mandates: Best Practices

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|4

|3814

|11

Report

AI Summary

This report examines the effectiveness and ethical considerations surrounding mandatory vaccination policies. It discusses the rise in measles cases globally and explores how governments are considering compulsory immunizations. The report analyses various approaches to vaccination mandates, including exemptions and penalties, and their impact on vaccination rates. It highlights that while mandates can improve vaccination rates, rigid, punitive policies may not be as effective as more flexible ones. The report emphasizes the importance of addressing the underlying reasons for low vaccination rates, such as poverty, social exclusion, and access difficulties, before implementing mandates. It also outlines five key steps for governments to take when considering mandates, including using multiple interventions, ensuring easy access to vaccines, and avoiding the entrenchment of inequity or fueling of anti-vaccine activism. The report suggests that allowing non-medical exemptions but making them hard to obtain might be the most effective approach, as removing choice entirely could induce parents to seek loopholes and fuel negative attitudes towards vaccination.

PUBLIC HEALTH Citizen science

is helping to map snakebite

risk p.478

ENVIRONMENT A call to safeguard

biodiversity in regions of

armed conflict p.478

POLITICS How Hindu

nationalists have co-opted

the trappings of science p.476

BIAS Why do racial

stereotypes persist

in sport? p.474

Thousands of people worldwide have

been affected by recent measles

outbreaks, even though there is a

safe and effective vaccine.

In the first four months of this year, the

World Health Organization (WHO) reported

about 226,000 measles cases — almost three

times the count recorded in the same period

last year (see go.nature.com/2jkq8d3).

Already, the number of cases in the United

States this year has exceeded the reported

tally in any year since the country halted

sustained transmission of the disease in

2000. Similarly, in Europe, the 2018 figures

were the highest this decade (see ‘Measles

on the rise’).

Partly in response to these outbreaks,

some governments are now considering

making vaccination for measles and other

diseases a legal requirement1. The state of

New York signed legislation to that effect

last month.

Such mandates, which began with small-

pox vaccination in nineteenth-century

Europe, are in place for numerous vaccines

in various countries. And several studies

show that requiring vaccination can

Mandate vaccination with c

Governments that are considering compulsory immunizations must avoid stoking

anti-vaccine sentiment, argue Saad B. Omer, Cornelia Betsch and Julie Lea

Children with measles in an overcrowded hospital ward in the Philippines, where an outbreak occurred in Manila and central Luzon in F

FRANCIS R. MALASIG/EPA-EFE/SHUTTERSTOCK

2 5 J U L Y 2 0 1 9 | V O L 5 7 1 | N A T U R E | 4 6 9

COMMENT

© 2019 Springer Nature Limited. All rights reserved.

is helping to map snakebite

risk p.478

ENVIRONMENT A call to safeguard

biodiversity in regions of

armed conflict p.478

POLITICS How Hindu

nationalists have co-opted

the trappings of science p.476

BIAS Why do racial

stereotypes persist

in sport? p.474

Thousands of people worldwide have

been affected by recent measles

outbreaks, even though there is a

safe and effective vaccine.

In the first four months of this year, the

World Health Organization (WHO) reported

about 226,000 measles cases — almost three

times the count recorded in the same period

last year (see go.nature.com/2jkq8d3).

Already, the number of cases in the United

States this year has exceeded the reported

tally in any year since the country halted

sustained transmission of the disease in

2000. Similarly, in Europe, the 2018 figures

were the highest this decade (see ‘Measles

on the rise’).

Partly in response to these outbreaks,

some governments are now considering

making vaccination for measles and other

diseases a legal requirement1. The state of

New York signed legislation to that effect

last month.

Such mandates, which began with small-

pox vaccination in nineteenth-century

Europe, are in place for numerous vaccines

in various countries. And several studies

show that requiring vaccination can

Mandate vaccination with c

Governments that are considering compulsory immunizations must avoid stoking

anti-vaccine sentiment, argue Saad B. Omer, Cornelia Betsch and Julie Lea

Children with measles in an overcrowded hospital ward in the Philippines, where an outbreak occurred in Manila and central Luzon in F

FRANCIS R. MALASIG/EPA-EFE/SHUTTERSTOCK

2 5 J U L Y 2 0 1 9 | V O L 5 7 1 | N A T U R E | 4 6 9

COMMENT

© 2019 Springer Nature Limited. All rights reserved.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

improve rates in high-income countries

(see, for example, ref. 2), although there

is limited evidence of the impact of such

requirements in low- or middle-income

nations.

However, mandatory vaccination can

worsen inequities in access to resources,

because penalties for not complying can

disproportionately affect disadvantaged

groups. What’s more, the evidence suggests

that there is no simple linear relationship

between the forcefulness of a policy and its

impact on the rate of vaccination.

It is crucial that policies don’t inadvert-

ently entrench inequity or fuel anti-vaccine

activism. As specialists in vaccination

policy and programmes, we lay out here

what’s known, to help governments con-

sider whether a mandate is the right fit for

their situation. We also discuss what other

changes should be made before introduc-

ing requirements (see ‘Best practice’). And

we distil how mandates should be designed

to ensure effectiveness.

WHICH MANDATES WORK?

There has long been substantial variability

in how governments and jurisdictions

mandate vaccination — specifically, in

what is actually required of people; the

penalties imposed if requirements are not

met; and the age groups and populations

that are covered.

In the United States, for instance, proof

of immunization or exemption documen-

tation is required before children can go to

school. All 50 states and Washington DC

allow exemptions for medical reasons, and

45 states allow philosophical or religious

exemptions. In Australia, certain vaccines

are a requirement for entry into preschool

or childcare in some states, but not in

others. In Uganda, parents who fail to vac-

cinate their children can be jailed for six

months.

Studies conducted largely in the United

States and Europe suggest that making vac-

cination a requirement for enrolment in

childcare and school can help to increase

rates (see, for example, ref. 2). For instance,

a review of studies conducted mostly in the

United States found that the need to pro-

vide documentation to access childcare or to

attend school and college is associated with

a median improvement of 18 percentage

points in the rate of vaccination for diseases

such as measles, hepatitis B and whooping

cough (see go.nature.com/3tzrujo).

When it comes to obtaining an exemption,

having complex administrative procedures

in place (such as those involving counsel-

ling with a physician) reduces the number of

parents who refuse to have their children vac-

cinated. It also lowers the number of people

who are affected by vaccine-preventable

diseases2

. In a 2012 study, non-medical

exemption rates were more than twice as

high in US states that had relatively easy

exemption procedures, compared with states

that had more complex ones3.

Given such evidence, governments have

sometimes removed non-medical exemp-

tions altogether. In the past four years, the

states of Maine,

New York and Cali-

fornia joined West

Virginia and Mis-

sissippi in eliminat-

ing non-medical

exemptions for all

or some vaccines.

And in response

to a media and

public campaign,

Australia implemented legislation in 2016

that prevents parents from obtaining

non-medical exemptions.

Increases in vaccination rates have been

associated with financial penalties. These

take the form of either the withdrawal of

family assistance payments (currently as

much as Aus$26,000 (US$18,200) a year

in Australia, by our calculations) or fines

for parents who refuse to vaccinate their

children. In a study evaluating mandatory

vaccination in Europe, measles vaccine

coverage was 0.8% higher and whooping-

cough vaccine coverage was 1.1% higher

for every €500 (US$560) increase in the

penalty4.

Vaccination requirements (tied to school

and childcare access, or to monetary pen-

alties) fare well in comparisons with other

large-scale interventions, such as vaccina-

tion drives at schools, or communication

campaigns involving pamphlets, billboards,

television advertisements and so on. A 2017

review of interventions to increase vaccina-

tion found that in high-income countries,

requirements to vaccinate are more likely to

affect rates than are attempts to change ho

people think and feel about vaccination5.

EXEMPTIONS AND PENALTIES

So, in many cases, requirements to vaccina

do seem to improve vaccination rates. But

do rigid, punitive policies work better than

flexible ones? In our view, not necessarily.

In fact, the limited data that are available

suggest that a middle-of-the-road approach

might be more effective. These data come

mainly from California, Washington state

(which eliminated personal-belief exemp-

tions to measles, mumps and rubella (MMR)

vaccination this year) and Australia.

In 2015, California became the third US

state to eliminate all non-medical exemp-

tions, and the first state to do so in more

than three decades. This change in the law

was preceded by a 2014 administrative

initiative to reduce the misuse of a school

admission process involving ‘conditional

entrants’ — children who have started the

required vaccination schedule but haven’t

completed it6

. (Since 1979, children in Cal-

ifornia have been allowed to attend school

as conditional entrants — but before 2014,

only some schools followed up with par-

ents, and some children were never fully

vaccinated6.)

The proportion of children of kinder-

garten age who are not up to date on their

vaccinations has decreased in California,

from 9.8% in 2013 to 4.9% in 2017 (ref. 7).

However, this change seems to be mainly

associated with the administrative crack-

down on conditional entrants. Following

the elimination of non-medical exemp-

tions, many parents with strong objections

to vaccination simply acquired medical

exemptions instead, educated their chil-

dren at home, enrolled them in independ-

ent study programmes that do not require

classroom-based instruction, or found

other loopholes6.

In Australia, following policy changes in

1999, parents had to get their child vacci-

nated to get assistance payments. And they

could obtain non-medical exemptions only

after they had discussed the issue with a

health-care provider. According to surveys,

these policies helped to improve vaccina-

tion coverage from an estimated 80% to

more than 90% in three years8.

Then, in 2016, Australia implemented

a ‘No Jab No Pay’ policy, which removed

non-medical exemptions and applied the

“There is no

simple linear

relationship

between the

forcefulness

of a policy

and its impact

on the rate of

vaccination.”

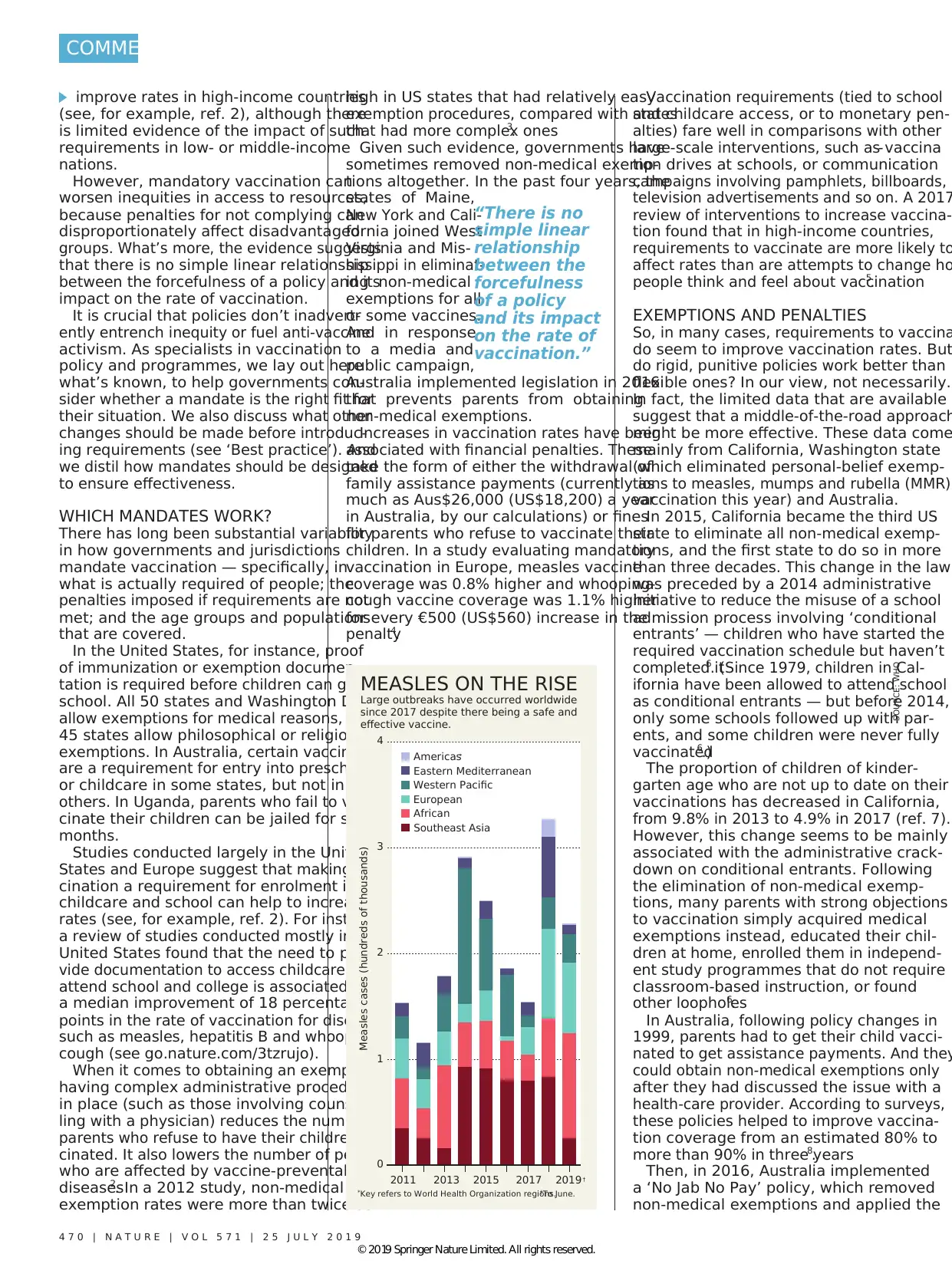

SOURCE: WHO

4 7 0 | N A T U R E | V O L 5 7 1 | 2 5 J U L Y 2 0 1 9

2015 2017 2019 †20132011

Measles cases (hundreds of thousands)

0

1

2

3

4

African

Americas*

Eastern Mediterranean

European

Southeast Asia

Western Pacific

MEASLES ON THE RISE

Large outbreaks have occurred worldwide

since 2017 despite there being a safe and

effective vaccine.

*Key refers to World Health Organization regions.†To June.

COMMENT

© 2019 Springer Nature Limited. All rights reserved.

(see, for example, ref. 2), although there

is limited evidence of the impact of such

requirements in low- or middle-income

nations.

However, mandatory vaccination can

worsen inequities in access to resources,

because penalties for not complying can

disproportionately affect disadvantaged

groups. What’s more, the evidence suggests

that there is no simple linear relationship

between the forcefulness of a policy and its

impact on the rate of vaccination.

It is crucial that policies don’t inadvert-

ently entrench inequity or fuel anti-vaccine

activism. As specialists in vaccination

policy and programmes, we lay out here

what’s known, to help governments con-

sider whether a mandate is the right fit for

their situation. We also discuss what other

changes should be made before introduc-

ing requirements (see ‘Best practice’). And

we distil how mandates should be designed

to ensure effectiveness.

WHICH MANDATES WORK?

There has long been substantial variability

in how governments and jurisdictions

mandate vaccination — specifically, in

what is actually required of people; the

penalties imposed if requirements are not

met; and the age groups and populations

that are covered.

In the United States, for instance, proof

of immunization or exemption documen-

tation is required before children can go to

school. All 50 states and Washington DC

allow exemptions for medical reasons, and

45 states allow philosophical or religious

exemptions. In Australia, certain vaccines

are a requirement for entry into preschool

or childcare in some states, but not in

others. In Uganda, parents who fail to vac-

cinate their children can be jailed for six

months.

Studies conducted largely in the United

States and Europe suggest that making vac-

cination a requirement for enrolment in

childcare and school can help to increase

rates (see, for example, ref. 2). For instance,

a review of studies conducted mostly in the

United States found that the need to pro-

vide documentation to access childcare or to

attend school and college is associated with

a median improvement of 18 percentage

points in the rate of vaccination for diseases

such as measles, hepatitis B and whooping

cough (see go.nature.com/3tzrujo).

When it comes to obtaining an exemption,

having complex administrative procedures

in place (such as those involving counsel-

ling with a physician) reduces the number of

parents who refuse to have their children vac-

cinated. It also lowers the number of people

who are affected by vaccine-preventable

diseases2

. In a 2012 study, non-medical

exemption rates were more than twice as

high in US states that had relatively easy

exemption procedures, compared with states

that had more complex ones3.

Given such evidence, governments have

sometimes removed non-medical exemp-

tions altogether. In the past four years, the

states of Maine,

New York and Cali-

fornia joined West

Virginia and Mis-

sissippi in eliminat-

ing non-medical

exemptions for all

or some vaccines.

And in response

to a media and

public campaign,

Australia implemented legislation in 2016

that prevents parents from obtaining

non-medical exemptions.

Increases in vaccination rates have been

associated with financial penalties. These

take the form of either the withdrawal of

family assistance payments (currently as

much as Aus$26,000 (US$18,200) a year

in Australia, by our calculations) or fines

for parents who refuse to vaccinate their

children. In a study evaluating mandatory

vaccination in Europe, measles vaccine

coverage was 0.8% higher and whooping-

cough vaccine coverage was 1.1% higher

for every €500 (US$560) increase in the

penalty4.

Vaccination requirements (tied to school

and childcare access, or to monetary pen-

alties) fare well in comparisons with other

large-scale interventions, such as vaccina-

tion drives at schools, or communication

campaigns involving pamphlets, billboards,

television advertisements and so on. A 2017

review of interventions to increase vaccina-

tion found that in high-income countries,

requirements to vaccinate are more likely to

affect rates than are attempts to change ho

people think and feel about vaccination5.

EXEMPTIONS AND PENALTIES

So, in many cases, requirements to vaccina

do seem to improve vaccination rates. But

do rigid, punitive policies work better than

flexible ones? In our view, not necessarily.

In fact, the limited data that are available

suggest that a middle-of-the-road approach

might be more effective. These data come

mainly from California, Washington state

(which eliminated personal-belief exemp-

tions to measles, mumps and rubella (MMR)

vaccination this year) and Australia.

In 2015, California became the third US

state to eliminate all non-medical exemp-

tions, and the first state to do so in more

than three decades. This change in the law

was preceded by a 2014 administrative

initiative to reduce the misuse of a school

admission process involving ‘conditional

entrants’ — children who have started the

required vaccination schedule but haven’t

completed it6

. (Since 1979, children in Cal-

ifornia have been allowed to attend school

as conditional entrants — but before 2014,

only some schools followed up with par-

ents, and some children were never fully

vaccinated6.)

The proportion of children of kinder-

garten age who are not up to date on their

vaccinations has decreased in California,

from 9.8% in 2013 to 4.9% in 2017 (ref. 7).

However, this change seems to be mainly

associated with the administrative crack-

down on conditional entrants. Following

the elimination of non-medical exemp-

tions, many parents with strong objections

to vaccination simply acquired medical

exemptions instead, educated their chil-

dren at home, enrolled them in independ-

ent study programmes that do not require

classroom-based instruction, or found

other loopholes6.

In Australia, following policy changes in

1999, parents had to get their child vacci-

nated to get assistance payments. And they

could obtain non-medical exemptions only

after they had discussed the issue with a

health-care provider. According to surveys,

these policies helped to improve vaccina-

tion coverage from an estimated 80% to

more than 90% in three years8.

Then, in 2016, Australia implemented

a ‘No Jab No Pay’ policy, which removed

non-medical exemptions and applied the

“There is no

simple linear

relationship

between the

forcefulness

of a policy

and its impact

on the rate of

vaccination.”

SOURCE: WHO

4 7 0 | N A T U R E | V O L 5 7 1 | 2 5 J U L Y 2 0 1 9

2015 2017 2019 †20132011

Measles cases (hundreds of thousands)

0

1

2

3

4

African

Americas*

Eastern Mediterranean

European

Southeast Asia

Western Pacific

MEASLES ON THE RISE

Large outbreaks have occurred worldwide

since 2017 despite there being a safe and

effective vaccine.

*Key refers to World Health Organization regions.†To June.

COMMENT

© 2019 Springer Nature Limited. All rights reserved.

loss of payments more frequently. Overall

immunization rates for five-year-olds

have since increased nationally, from

92.6% in 2015 to 94.8% by March 2019

(see go.nature.com/2xmgtun). But this

smaller improvement comes after the

roll-out of several concurrent strategies

designed to improve coverage — from

schemes to remind parents to get their

child vaccinated, to campaigns to improve

public awareness. So the impact of the ‘No

Jab No Pay’ policy alone is unclear.

In 2017, one of us (J.L.) was involved

in a study that interviewed 31 parents in

Australia who were refusing vaccination

for their child9. Of this group, 17 indicated

that they planned to get more involved in

protest action if additional such measures

were implemented, because they felt that

the government was coercing them. Inter-

estingly, in an experimental study10

, more

people with a negative attitude towards

vaccination chose to accept a hypothetical

second vaccine when they had previously

been told that they could choose to be vac-

cinated with a first vaccine. When these

individuals were told that they had to be

vaccinated with the first vaccine, 39% less

people elected to receive the optional one10

.

In short, various findings suggest that the

most effective approach when it comes to

mandating vaccination could be to allow

non-medical exemptions, but to make

them hard to obtain. Removing the choice

of opting out entirely might simply induce

parents to seek loopholes, and, worse, fuel

negative attitudes towards vaccination.

SMART AND ETHICAL

If vaccination rates are low in a particular

region or community, a government’s

first step must be to find out why. Guid-

ance from the WHO Regional Office for

Europe, for example, lays out steps for tar-

geting specific communities, such as by

working with community leaders, health-

care workers and service users to establish

whether people are struggling to get to

their local clinics or avoiding health-care

providers for some other reason11

. (J. L.

was a reviewer of this guide, and all three

of us have received funds from the WHO,

which, as a UN agency, has no financial

competing interest regarding this article.)

Mandates are often inspired by the per-

ception among politicians and the public

that vaccine refusal by parents is the big-

gest problem. But poverty, social exclusion

and difficulties over access also depress

rates, and, in many settings, more so than

refusal. In Germany, for example, barriers

to access probably explain why children of

migrant parents have a 10% lower immu-

nization rate for booster doses (such as fo

tetanus or human papillomavirus) than do

children who were born there12

.

A requirement to vaccinate when the

vaccine or primary-care service is difficult

or impossible for many people to reach is

not justifiable or fair13

. Thus, before even

considering mandates, governments must

ensure that people from all sectors of

society can get vaccines easily and safely

This means making primary-care services

flexible, welcoming and easy to reach, and

ensuring a stable supply of vaccines.

If governments then decide that

mandates are appropriate, they should tak

the following five steps.

Use multiple interventions. Ideally,

requirements to vaccinate should be part

of a suite of interventions. These could

include: robust methods for recording

immunization, such as in a registry; text-

message or e-mail reminders to parents

before a child’s vaccines are due; and a

process to monitor and give feedback on

how primary-care providers perform on

vaccination rates5 (see also go.nature.

Parents on a march protesting against mandatory vaccinations in Washington state earlier this year.

2 5 J U L Y 2 0 1 9 | V O L 5 7 1 | N A T U R E | 4 7 1

COMMENT

LINDSEY WASSON/REUTERS

© 2019 Springer Nature Limited. All rights reserved.

immunization rates for five-year-olds

have since increased nationally, from

92.6% in 2015 to 94.8% by March 2019

(see go.nature.com/2xmgtun). But this

smaller improvement comes after the

roll-out of several concurrent strategies

designed to improve coverage — from

schemes to remind parents to get their

child vaccinated, to campaigns to improve

public awareness. So the impact of the ‘No

Jab No Pay’ policy alone is unclear.

In 2017, one of us (J.L.) was involved

in a study that interviewed 31 parents in

Australia who were refusing vaccination

for their child9. Of this group, 17 indicated

that they planned to get more involved in

protest action if additional such measures

were implemented, because they felt that

the government was coercing them. Inter-

estingly, in an experimental study10

, more

people with a negative attitude towards

vaccination chose to accept a hypothetical

second vaccine when they had previously

been told that they could choose to be vac-

cinated with a first vaccine. When these

individuals were told that they had to be

vaccinated with the first vaccine, 39% less

people elected to receive the optional one10

.

In short, various findings suggest that the

most effective approach when it comes to

mandating vaccination could be to allow

non-medical exemptions, but to make

them hard to obtain. Removing the choice

of opting out entirely might simply induce

parents to seek loopholes, and, worse, fuel

negative attitudes towards vaccination.

SMART AND ETHICAL

If vaccination rates are low in a particular

region or community, a government’s

first step must be to find out why. Guid-

ance from the WHO Regional Office for

Europe, for example, lays out steps for tar-

geting specific communities, such as by

working with community leaders, health-

care workers and service users to establish

whether people are struggling to get to

their local clinics or avoiding health-care

providers for some other reason11

. (J. L.

was a reviewer of this guide, and all three

of us have received funds from the WHO,

which, as a UN agency, has no financial

competing interest regarding this article.)

Mandates are often inspired by the per-

ception among politicians and the public

that vaccine refusal by parents is the big-

gest problem. But poverty, social exclusion

and difficulties over access also depress

rates, and, in many settings, more so than

refusal. In Germany, for example, barriers

to access probably explain why children of

migrant parents have a 10% lower immu-

nization rate for booster doses (such as fo

tetanus or human papillomavirus) than do

children who were born there12

.

A requirement to vaccinate when the

vaccine or primary-care service is difficult

or impossible for many people to reach is

not justifiable or fair13

. Thus, before even

considering mandates, governments must

ensure that people from all sectors of

society can get vaccines easily and safely

This means making primary-care services

flexible, welcoming and easy to reach, and

ensuring a stable supply of vaccines.

If governments then decide that

mandates are appropriate, they should tak

the following five steps.

Use multiple interventions. Ideally,

requirements to vaccinate should be part

of a suite of interventions. These could

include: robust methods for recording

immunization, such as in a registry; text-

message or e-mail reminders to parents

before a child’s vaccines are due; and a

process to monitor and give feedback on

how primary-care providers perform on

vaccination rates5 (see also go.nature.

Parents on a march protesting against mandatory vaccinations in Washington state earlier this year.

2 5 J U L Y 2 0 1 9 | V O L 5 7 1 | N A T U R E | 4 7 1

COMMENT

LINDSEY WASSON/REUTERS

© 2019 Springer Nature Limited. All rights reserved.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

com/3puzrga). All of these interventions

should be in place whether or not mandates

are implemented (see ‘Best practice’).

Ensure just procedures. Limited restric-

tions on personal autonomy are more likely

to be workable in democracies. In these,

societies are more able to express their

collective will than in dictatorships, where

such restrictions can be abused. Indeed,

it is crucial that the process of develop-

ing mandates is itself democratic. Delib-

erative methods can ask what an informed

citizenry would find an acceptable policy

response and why. A good model is the

community juries used for more than

two decades, mostly in the United States,

Australia and Canada, to address policy

issues in other areas of health care, such

as for cancer screening. In these, panels

of citizens hear evidence, then debate the

issue and give their verdicts14

.

Make penalties proportionate. In our

view, incarceration is never justified

for enforcing vaccination. Temporary

quarantine or the use of child protection

laws might be an appropriate action when

the risk of a vaccine-preventable disease

is very high (such as in a newborn whose

mother tests positive for hepatitis B)15

. Even

with penalties such as fines, withheld bene-

fits or blocked entry to childcare or schools,

care must be taken to ensure that they do

not exacerbate social or health inequities.

Monitor safety and compensate for side

effects. In the exceedingly rare instances in

which required vaccines cause harm, those

affected should be adequately compen-

sated. (For instance, around 2.6 cases of the

rare bleeding disorder thrombocytopenic

purpura arise for every 100,000 doses of

MMR vaccine that are given16

.)

Proactive surveillance systems that

monitor side effects should be paired with

a timely programme for compensation

that minimizes administrative and legal

burdens for those injured17

. In the United

States, people seeking compensation

following vaccination have to demonstrate

only that they (or their child) had an

adverse event known to be associated

with the vaccine. By contrast, people in

Australia have to pursue compensation

through the courts — a time-consuming

and expensive process.

Such programmes can be financially

sustainable. In the United States, vaccine

manufacturers are taxed on vaccines sold

in the country to finance this (currently,

75 cents per antigen). Other financial mod-

els have been proposed, including for low

and middle-income countries18

.

Avoid selective mandates. Governments

should avoid making specific vaccines

mand ator y.In

Fr a n c ei n t h e

1960s, there was a

policy shift. Older

vaccines such as

those for smallpox,

diphtheria, tetanus,

tuberculosis and

polio remained

mandatory; newer

ones for diseases such as measles were only

‘recommended’19

. For many years, there

has been a difference in uptake of up to

20% between the two classes. Vaccines that

were ‘only’ recommended were perceived

as non-essential by French parents. (In

2018, the recommended vaccines became

mandatory20

.) And experimental evidence

shows that making one vaccine mandatory

might reduce people’s uptake of others10

.

In our view, Germany, which is currently

considering a mandate for just measles,

should rethink.

In summary, making vaccination a

legal requirement can be a powerful and

effective tool if implemented with care and

with regard to the context. Crucially, evi-

dence for the effectiveness of mandates is

largely limited to high-income countries.

Overly strict mandates can result in

parents finding ways to avoid the vaccine

requirements, and selective mandates

might damage the broader vaccination

programme. Most importantly, vaccine

policy — like other types of effective public

policy — must be based on evidence, and

not driven by political and ideological

considerations.■

Saad B. Omer is the director of the Yale

Institute for Global Health; professor of

medicine (infectious diseases) at Yale Schoo

of Medicine; and professor of epidemiology

of microbial diseases at Yale School of

Public Health, New Haven, Connecticut,

USA. Cornelia Betsch is professor of

health communication at the University of

Erfurt, Psychology and Infectious Diseases

Lab, Erfurt, Germany. Julie Leask is

professor in the Susan Wakil School of

Nursing and Midwifery at the University

of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health,

Camperdown, New South Wales, Australia.

e-mail: julie.leask@sydney.edu.au

1. MacDonald, N. E. et al. Vaccine 36, 5811–5818

(2018).

2. Omer, S. B. et al. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 296,

1757–1763 (2006).

3. Omer, S. B., Richards, J. L., Ward, M. &

Bednarczyk, R. A. N. Engl. J. Med. 367,

1170–1171 (2012).

4. Vaz, O. M. et al. Pediatrics (in the press).

5. Brewer, N. T., Chapman, G. B., Rothman, A. J.,

Leask, J. & Kempe, A. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest

18, 149–207 (2017).

6. Delamater P. L. et al. Pediatrics 143, e20183301

(2019).

7. Pingali, S. C. et al. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 322, 49–56

(2019).

8. Bond, L., Davie, G., Carlin, J. B., Lester, R. & Nolan,

T. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 26, 58–64 (2002).

9. Helps, C., Leask, J. & Barclay, L. J. Pub. Health

Policy 39, 156–169 (2018).

10. Betsch, C. & Böhm, R. Eur. J. Public Health 26,

378–381 (2016).

11. World Health Organization Regional Office for

Europe. The Guide to Tailoring Immunization

Programmes (TIP) (WHO, 2013).

12. Poethko-Müller, C., Kuhnert, R., Gillesberg

Lassen, S. & Siedler, A. [in German]

Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung

Gesundheitsschutz 62, 410–421 (2019).

13. Boyce, T. et al. Eurosurveillance 24, 1800204

(2019).

14. Degeling, C., Rychetnik, L., Street, J., Thomas, R.

& Carter, S. M. Soc. Sci. Med. 179, 166–171

(2017).

15. Isaacs, D., Kilham, H., Leask, J. & Tobin, B. Vaccine

27, 615–618 (2009).

16. Mantadakis, E., Farmaki, E. & Buchanan, G. R.

J. Pediatr. 156, 623–628 (2010).

17. Attwell, K., Drislane, S. & Leask, J. Vaccine 37,

2843–2848 (2019).

18. Halabi, S. & Omer, S. B. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 317,

471–472 (2017).

19. Attwell, K. et al. Vaccine 36, 7377–7384 (2018).

20. Lévy-Bruhl D. et al. Eurosurveillance 24, 1900301

(2019).

“Experimental

evidence shows

that making

one vaccine

mandatory

might reduce

people’s uptake

of others.”

4 7 2 | N A T U R E | V O L 5 7 1 | 2 5 J U L Y 2 0 1 9

COMMENT

Ensure everyone can

access vaccines

Use immunization

registry and reminders

Diagnose reasons for

under-vaccination

Monitor performance of

providers and give feedback

Provide vaccinations in

communities

Make clinics welcoming,

safe and easy to get to

Ensure stable supply

of vaccines

Use multiple interventions

to improve uptake

Create smart and

ethical mandates

Ensure procedures

are fair

Make penalties

appropriate

Compensate for

side effects

Avoid implementing

selective mandates

Essential

If mandates are politically

considered appropriate

STEP 1 STEP 2 STEP 3

Monitor safety

BEST PRACTICE

Before even considering mandatory vaccination, governments must first ensure easy access to vaccines.

(Examples in white boxes are not exhaustive.)

© 2019 Springer Nature Limited. All rights reserved.

should be in place whether or not mandates

are implemented (see ‘Best practice’).

Ensure just procedures. Limited restric-

tions on personal autonomy are more likely

to be workable in democracies. In these,

societies are more able to express their

collective will than in dictatorships, where

such restrictions can be abused. Indeed,

it is crucial that the process of develop-

ing mandates is itself democratic. Delib-

erative methods can ask what an informed

citizenry would find an acceptable policy

response and why. A good model is the

community juries used for more than

two decades, mostly in the United States,

Australia and Canada, to address policy

issues in other areas of health care, such

as for cancer screening. In these, panels

of citizens hear evidence, then debate the

issue and give their verdicts14

.

Make penalties proportionate. In our

view, incarceration is never justified

for enforcing vaccination. Temporary

quarantine or the use of child protection

laws might be an appropriate action when

the risk of a vaccine-preventable disease

is very high (such as in a newborn whose

mother tests positive for hepatitis B)15

. Even

with penalties such as fines, withheld bene-

fits or blocked entry to childcare or schools,

care must be taken to ensure that they do

not exacerbate social or health inequities.

Monitor safety and compensate for side

effects. In the exceedingly rare instances in

which required vaccines cause harm, those

affected should be adequately compen-

sated. (For instance, around 2.6 cases of the

rare bleeding disorder thrombocytopenic

purpura arise for every 100,000 doses of

MMR vaccine that are given16

.)

Proactive surveillance systems that

monitor side effects should be paired with

a timely programme for compensation

that minimizes administrative and legal

burdens for those injured17

. In the United

States, people seeking compensation

following vaccination have to demonstrate

only that they (or their child) had an

adverse event known to be associated

with the vaccine. By contrast, people in

Australia have to pursue compensation

through the courts — a time-consuming

and expensive process.

Such programmes can be financially

sustainable. In the United States, vaccine

manufacturers are taxed on vaccines sold

in the country to finance this (currently,

75 cents per antigen). Other financial mod-

els have been proposed, including for low

and middle-income countries18

.

Avoid selective mandates. Governments

should avoid making specific vaccines

mand ator y.In

Fr a n c ei n t h e

1960s, there was a

policy shift. Older

vaccines such as

those for smallpox,

diphtheria, tetanus,

tuberculosis and

polio remained

mandatory; newer

ones for diseases such as measles were only

‘recommended’19

. For many years, there

has been a difference in uptake of up to

20% between the two classes. Vaccines that

were ‘only’ recommended were perceived

as non-essential by French parents. (In

2018, the recommended vaccines became

mandatory20

.) And experimental evidence

shows that making one vaccine mandatory

might reduce people’s uptake of others10

.

In our view, Germany, which is currently

considering a mandate for just measles,

should rethink.

In summary, making vaccination a

legal requirement can be a powerful and

effective tool if implemented with care and

with regard to the context. Crucially, evi-

dence for the effectiveness of mandates is

largely limited to high-income countries.

Overly strict mandates can result in

parents finding ways to avoid the vaccine

requirements, and selective mandates

might damage the broader vaccination

programme. Most importantly, vaccine

policy — like other types of effective public

policy — must be based on evidence, and

not driven by political and ideological

considerations.■

Saad B. Omer is the director of the Yale

Institute for Global Health; professor of

medicine (infectious diseases) at Yale Schoo

of Medicine; and professor of epidemiology

of microbial diseases at Yale School of

Public Health, New Haven, Connecticut,

USA. Cornelia Betsch is professor of

health communication at the University of

Erfurt, Psychology and Infectious Diseases

Lab, Erfurt, Germany. Julie Leask is

professor in the Susan Wakil School of

Nursing and Midwifery at the University

of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health,

Camperdown, New South Wales, Australia.

e-mail: julie.leask@sydney.edu.au

1. MacDonald, N. E. et al. Vaccine 36, 5811–5818

(2018).

2. Omer, S. B. et al. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 296,

1757–1763 (2006).

3. Omer, S. B., Richards, J. L., Ward, M. &

Bednarczyk, R. A. N. Engl. J. Med. 367,

1170–1171 (2012).

4. Vaz, O. M. et al. Pediatrics (in the press).

5. Brewer, N. T., Chapman, G. B., Rothman, A. J.,

Leask, J. & Kempe, A. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest

18, 149–207 (2017).

6. Delamater P. L. et al. Pediatrics 143, e20183301

(2019).

7. Pingali, S. C. et al. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 322, 49–56

(2019).

8. Bond, L., Davie, G., Carlin, J. B., Lester, R. & Nolan,

T. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 26, 58–64 (2002).

9. Helps, C., Leask, J. & Barclay, L. J. Pub. Health

Policy 39, 156–169 (2018).

10. Betsch, C. & Böhm, R. Eur. J. Public Health 26,

378–381 (2016).

11. World Health Organization Regional Office for

Europe. The Guide to Tailoring Immunization

Programmes (TIP) (WHO, 2013).

12. Poethko-Müller, C., Kuhnert, R., Gillesberg

Lassen, S. & Siedler, A. [in German]

Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung

Gesundheitsschutz 62, 410–421 (2019).

13. Boyce, T. et al. Eurosurveillance 24, 1800204

(2019).

14. Degeling, C., Rychetnik, L., Street, J., Thomas, R.

& Carter, S. M. Soc. Sci. Med. 179, 166–171

(2017).

15. Isaacs, D., Kilham, H., Leask, J. & Tobin, B. Vaccine

27, 615–618 (2009).

16. Mantadakis, E., Farmaki, E. & Buchanan, G. R.

J. Pediatr. 156, 623–628 (2010).

17. Attwell, K., Drislane, S. & Leask, J. Vaccine 37,

2843–2848 (2019).

18. Halabi, S. & Omer, S. B. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 317,

471–472 (2017).

19. Attwell, K. et al. Vaccine 36, 7377–7384 (2018).

20. Lévy-Bruhl D. et al. Eurosurveillance 24, 1900301

(2019).

“Experimental

evidence shows

that making

one vaccine

mandatory

might reduce

people’s uptake

of others.”

4 7 2 | N A T U R E | V O L 5 7 1 | 2 5 J U L Y 2 0 1 9

COMMENT

Ensure everyone can

access vaccines

Use immunization

registry and reminders

Diagnose reasons for

under-vaccination

Monitor performance of

providers and give feedback

Provide vaccinations in

communities

Make clinics welcoming,

safe and easy to get to

Ensure stable supply

of vaccines

Use multiple interventions

to improve uptake

Create smart and

ethical mandates

Ensure procedures

are fair

Make penalties

appropriate

Compensate for

side effects

Avoid implementing

selective mandates

Essential

If mandates are politically

considered appropriate

STEP 1 STEP 2 STEP 3

Monitor safety

BEST PRACTICE

Before even considering mandatory vaccination, governments must first ensure easy access to vaccines.

(Examples in white boxes are not exhaustive.)

© 2019 Springer Nature Limited. All rights reserved.

1 out of 4

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.