Pediatric Anaphylaxis AEFI in Victoria, Australia: 2007-2013

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|6

|6284

|12

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a comprehensive analysis of pediatric anaphylaxis as an adverse event following immunization (AEFI) in Victoria, Australia, from 2007 to 2013. The study, based on data from the SAEFVIC surveillance system, applied the Brighton Collaboration case definition to classify and analyze anaphylactic events. The findings reveal an estimated incidence rate of anaphylaxis for DTaP vaccines of 0.36 cases per 100,000 doses and 1.25 per 100,000 doses for MMR vaccines. The majority of cases had rapid onset, but some developed symptoms beyond 30 minutes post-immunization. Intramuscular adrenaline was administered in most cases, with all patients making a full recovery. The study highlights the importance of diagnostic criteria in passive surveillance systems and emphasizes the need for healthcare professionals and parents to be aware of the potential for delayed onset of anaphylaxis following immunization.

Vaccine 33 (2015) 1602–1607

Contentslists available at ScienceDirect

Vaccine

j o u rn al h ome p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / v a c c i n e

Pediatric anaphylacticadverseevents following immunization in

Victoria, Australia from 2007 to 2013

Daryl R. Chenga,b,∗, Kirsten P. Perretta,c,d, Sharon Chood, Margie Danchina,c,e,

Jim P. Butteryf, Nigel W. Crawforda,e,f

a Departmentof GeneralMedicine,TheRoyal Children’sHospital,Melbourne,VIC, Australia

b JohnsHopkinsBloombergSchoolof Public Health,Baltimore,MD, USA

c Vaccineand ImmunisationResearchGroup(VIRGo),Murdoch ChildrensResearchInstituteand MelbourneSchoolof Populationand GlobalHealth,

TheUniversityof Melbourne,Melbourne,VIC, Australia

d Departmentof Allergyand Immunology,Royal Children’sHospital,Melbourne,VIC, Australia

e Departmentof Pediatrics,The Universityof Melbourne,Melbourne,VIC, Australia

f SAEFVIC,Murdoch Children’sResearchInstitute,Melbourne,VIC, Australia

a r t i c l e i n f o

Articlehistory:

Received10 November 2014

Receivedin revised form 3 February 2015

Accepted4 February 2015

Available online 16 February 2015

Keywords:

Anaphylaxis

Immunization

AEFI

Vaccine safety

a b s t r a c t

Background:Anaphylaxis is a rare life-threatening adverse event following immunization (AEFI). Vari-

ability in presentationcan make differentiation between anaphylaxisand other AEFI difficult. This study

summarizespediatricanaphylaxisAEFI reportedto an Australianstate-basedpassivesurveillancesystem.

Methods:All suspectedand reported pediatric (<18years)anaphylaxisAEFI notified to SAEFVIC (Surveil-

lance of Adverse Events Following Vaccination In the Community) Melbourne, Australia, between May

2007 to May 2013 were analyzed.Clinical descriptions of the AEFI, using the internationally recognized

Brighton Collaborationcasedefinition (BCCD)and final outcome were documented.

Results:93%(25/27) of AEFI classifiedas anaphylaxismet BCCD criteria, with 36%(9/25), assessedas the

highest level of diagnostic certainty (Level 1). Median age was 4.7 years (range 0.3–16.2); 48%of cases

were male. The vaccine antigens administered included: diphtheria, tetanus,acellular pertussis (DTaP)

alone or in combination vaccinescontaining other antigensin 11 of 25 cases(44%);and live attenuated

measlesmumps rubella (MMR) vaccinefor six (five also had other vaccinesconcomitantlyadministered).

The estimatedincidencerate of anaphylaxisfor DTaP vaccineswas 0.36 casesper 100,000doses,and 1.25

per 100,000 doses for MMR vaccines.The majority of caseshad rapid onset, but in 24%(6/25) of cases,

first symptomsof anaphylaxisdeveloped≥30min after immunization. In 60%(15/25) of cases,symptoms

resolved ≤60min of presentation.Intramuscular adrenaline was administered in 90%(18/25) of cases.

All casesmade a full recoverywith no sequelaeidentified.

Conclusion:This comprehensivecase series of pediatric anaphylaxisas an AEFI identified that diagnos-

tic criteria are useful when applied to a passive vaccine surveillance system when adequate clinical

information is available.Anaphylaxis as an AEFI is rare and usually begins within 30 min of vaccination.

However, healthcareprofessionalsand vaccinees/parentsshould be aware that onset of anaphylaxiscan

be delayedbeyond30 min following immunization and that medical attentionshould be soughtpromptly

if anaphylaxisis suspected.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Australia has a standardized childhood National Immunisa-

tion Program (NIP) schedule approved and reviewed on a regular

∗ Correspondingauthor at: The Royal Children’sHospital Melbourne, 50 Fleming-

ton Rd, Parkville, VIC 3052, Australia. Tel.: +619345 5522.

E-mail address:daryl.cheng@rch.org.au(D.R.Cheng).

basis by the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisa-

tion (ATAGI) and authorized by the National Health and Medical

ResearchCouncil (NHMRC) [1]. It includes infant and early child-

hood immunization, as well as a secondaryschool (age12–16 years)

program for catch-up vaccines (Hepatitis B, Varicella) and new

vaccines(e.g.Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine introduced for

females in 2007; males in 2012) [2]. There are also specific special

risk groups with additional vaccine requirements (e.g. Aboriginal

and Torres St Islanders).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.008

0264-410X/©2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Contentslists available at ScienceDirect

Vaccine

j o u rn al h ome p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / v a c c i n e

Pediatric anaphylacticadverseevents following immunization in

Victoria, Australia from 2007 to 2013

Daryl R. Chenga,b,∗, Kirsten P. Perretta,c,d, Sharon Chood, Margie Danchina,c,e,

Jim P. Butteryf, Nigel W. Crawforda,e,f

a Departmentof GeneralMedicine,TheRoyal Children’sHospital,Melbourne,VIC, Australia

b JohnsHopkinsBloombergSchoolof Public Health,Baltimore,MD, USA

c Vaccineand ImmunisationResearchGroup(VIRGo),Murdoch ChildrensResearchInstituteand MelbourneSchoolof Populationand GlobalHealth,

TheUniversityof Melbourne,Melbourne,VIC, Australia

d Departmentof Allergyand Immunology,Royal Children’sHospital,Melbourne,VIC, Australia

e Departmentof Pediatrics,The Universityof Melbourne,Melbourne,VIC, Australia

f SAEFVIC,Murdoch Children’sResearchInstitute,Melbourne,VIC, Australia

a r t i c l e i n f o

Articlehistory:

Received10 November 2014

Receivedin revised form 3 February 2015

Accepted4 February 2015

Available online 16 February 2015

Keywords:

Anaphylaxis

Immunization

AEFI

Vaccine safety

a b s t r a c t

Background:Anaphylaxis is a rare life-threatening adverse event following immunization (AEFI). Vari-

ability in presentationcan make differentiation between anaphylaxisand other AEFI difficult. This study

summarizespediatricanaphylaxisAEFI reportedto an Australianstate-basedpassivesurveillancesystem.

Methods:All suspectedand reported pediatric (<18years)anaphylaxisAEFI notified to SAEFVIC (Surveil-

lance of Adverse Events Following Vaccination In the Community) Melbourne, Australia, between May

2007 to May 2013 were analyzed.Clinical descriptions of the AEFI, using the internationally recognized

Brighton Collaborationcasedefinition (BCCD)and final outcome were documented.

Results:93%(25/27) of AEFI classifiedas anaphylaxismet BCCD criteria, with 36%(9/25), assessedas the

highest level of diagnostic certainty (Level 1). Median age was 4.7 years (range 0.3–16.2); 48%of cases

were male. The vaccine antigens administered included: diphtheria, tetanus,acellular pertussis (DTaP)

alone or in combination vaccinescontaining other antigensin 11 of 25 cases(44%);and live attenuated

measlesmumps rubella (MMR) vaccinefor six (five also had other vaccinesconcomitantlyadministered).

The estimatedincidencerate of anaphylaxisfor DTaP vaccineswas 0.36 casesper 100,000doses,and 1.25

per 100,000 doses for MMR vaccines.The majority of caseshad rapid onset, but in 24%(6/25) of cases,

first symptomsof anaphylaxisdeveloped≥30min after immunization. In 60%(15/25) of cases,symptoms

resolved ≤60min of presentation.Intramuscular adrenaline was administered in 90%(18/25) of cases.

All casesmade a full recoverywith no sequelaeidentified.

Conclusion:This comprehensivecase series of pediatric anaphylaxisas an AEFI identified that diagnos-

tic criteria are useful when applied to a passive vaccine surveillance system when adequate clinical

information is available.Anaphylaxis as an AEFI is rare and usually begins within 30 min of vaccination.

However, healthcareprofessionalsand vaccinees/parentsshould be aware that onset of anaphylaxiscan

be delayedbeyond30 min following immunization and that medical attentionshould be soughtpromptly

if anaphylaxisis suspected.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Australia has a standardized childhood National Immunisa-

tion Program (NIP) schedule approved and reviewed on a regular

∗ Correspondingauthor at: The Royal Children’sHospital Melbourne, 50 Fleming-

ton Rd, Parkville, VIC 3052, Australia. Tel.: +619345 5522.

E-mail address:daryl.cheng@rch.org.au(D.R.Cheng).

basis by the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisa-

tion (ATAGI) and authorized by the National Health and Medical

ResearchCouncil (NHMRC) [1]. It includes infant and early child-

hood immunization, as well as a secondaryschool (age12–16 years)

program for catch-up vaccines (Hepatitis B, Varicella) and new

vaccines(e.g.Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine introduced for

females in 2007; males in 2012) [2]. There are also specific special

risk groups with additional vaccine requirements (e.g. Aboriginal

and Torres St Islanders).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.008

0264-410X/©2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

D.R.Chenget al. / Vaccine33 (2015)1602–1607 1603

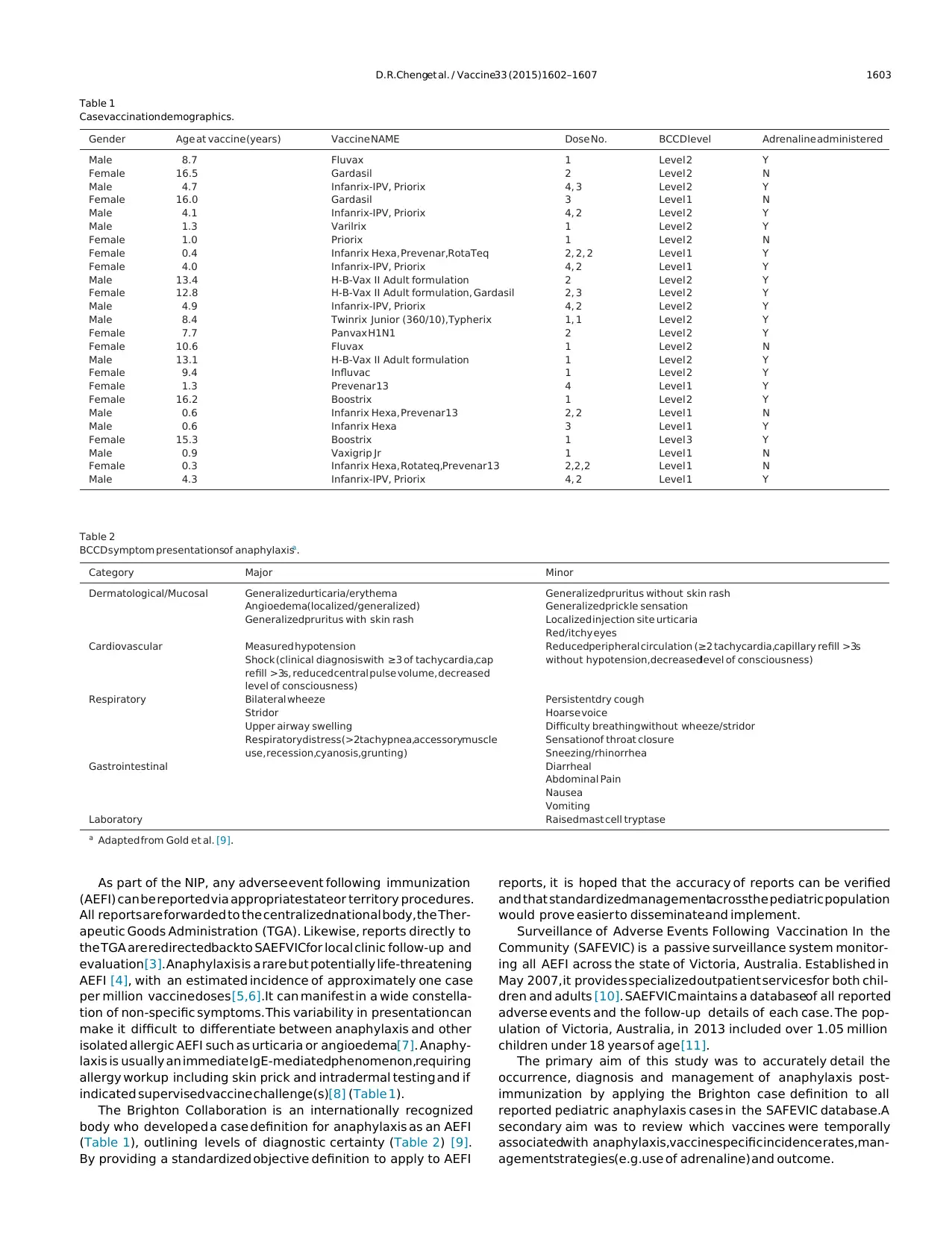

Table 1

Casevaccination demographics.

Gender Age at vaccine(years) Vaccine NAME Dose No. BCCD level Adrenaline administered

Male 8.7 Fluvax 1 Level 2 Y

Female 16.5 Gardasil 2 Level 2 N

Male 4.7 Infanrix-IPV, Priorix 4, 3 Level 2 Y

Female 16.0 Gardasil 3 Level 1 N

Male 4.1 Infanrix-IPV, Priorix 4, 2 Level 2 Y

Male 1.3 Varilrix 1 Level 2 Y

Female 1.0 Priorix 1 Level 2 N

Female 0.4 Infanrix Hexa, Prevenar,RotaTeq 2, 2, 2 Level 1 Y

Female 4.0 Infanrix-IPV, Priorix 4, 2 Level 1 Y

Male 13.4 H-B-Vax II Adult formulation 2 Level 2 Y

Female 12.8 H-B-Vax II Adult formulation, Gardasil 2, 3 Level 2 Y

Male 4.9 Infanrix-IPV, Priorix 4, 2 Level 2 Y

Male 8.4 Twinrix Junior (360/10),Typherix 1, 1 Level 2 Y

Female 7.7 Panvax H1N1 2 Level 2 Y

Female 10.6 Fluvax 1 Level 2 N

Male 13.1 H-B-Vax II Adult formulation 1 Level 2 Y

Female 9.4 Influvac 1 Level 2 Y

Female 1.3 Prevenar 13 4 Level 1 Y

Female 16.2 Boostrix 1 Level 2 Y

Male 0.6 Infanrix Hexa, Prevenar13 2, 2 Level 1 N

Male 0.6 Infanrix Hexa 3 Level 1 Y

Female 15.3 Boostrix 1 Level 3 Y

Male 0.9 Vaxigrip Jr 1 Level 1 N

Female 0.3 Infanrix Hexa, Rotateq,Prevenar13 2,2,2 Level 1 N

Male 4.3 Infanrix-IPV, Priorix 4, 2 Level 1 Y

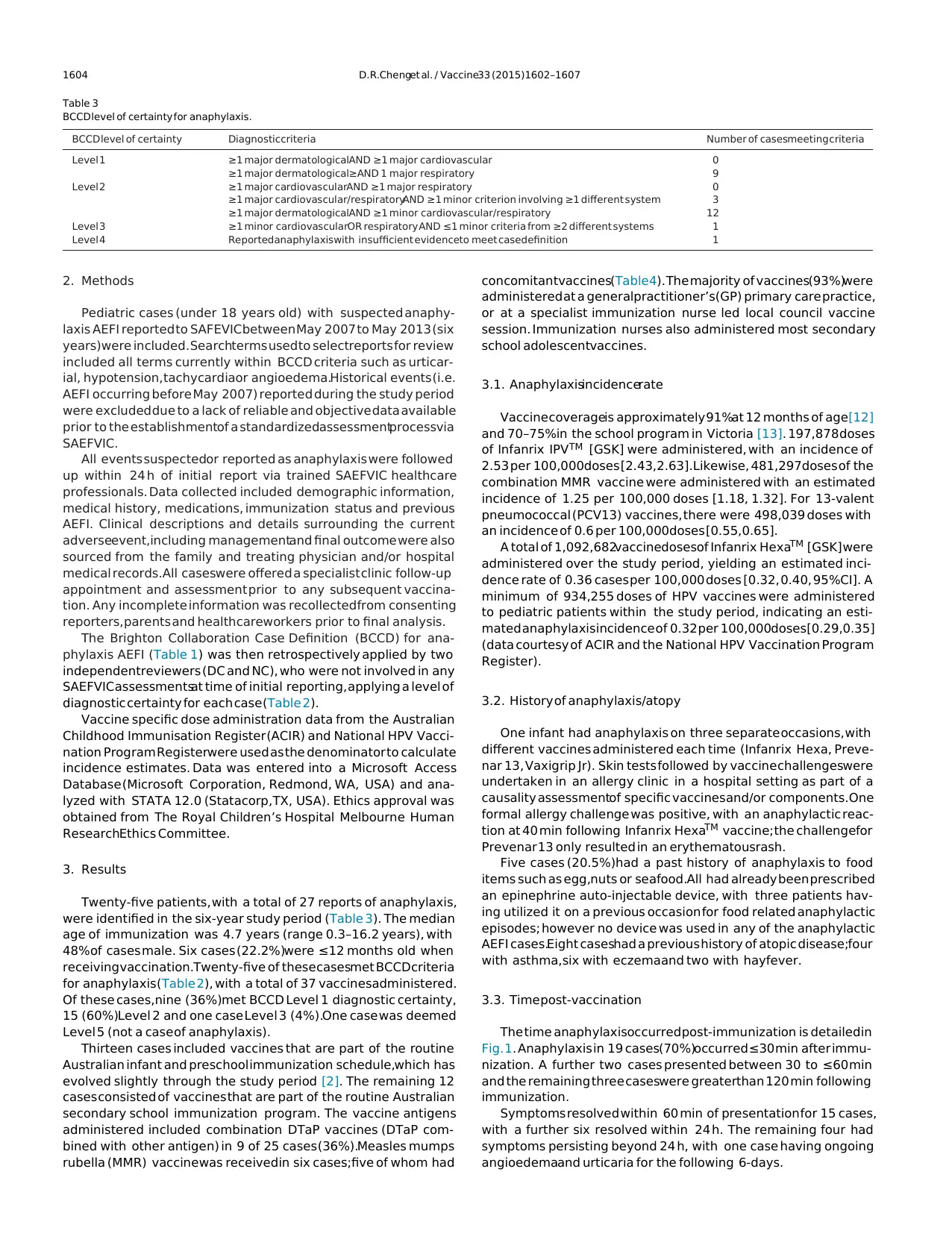

Table 2

BCCD symptom presentationsof anaphylaxisa.

Category Major Minor

Dermatological/Mucosal Generalizedurticaria/erythema

Angioedema(localized/generalized)

Generalizedpruritus with skin rash

Generalizedpruritus without skin rash

Generalizedprickle sensation

Localized injection site urticaria

Red/itchy eyes

Cardiovascular Measured hypotension

Shock (clinical diagnosiswith ≥3 of tachycardia,cap

refill >3s, reducedcentral pulse volume, decreased

level of consciousness)

Reducedperipheral circulation (≥2 tachycardia,capillary refill >3s

without hypotension,decreasedlevel of consciousness)

Respiratory Bilateral wheeze

Stridor

Upper airway swelling

Respiratorydistress(>2tachypnea,accessorymuscle

use, recession,cyanosis,grunting)

Persistentdry cough

Hoarse voice

Difficulty breathingwithout wheeze/stridor

Sensationof throat closure

Sneezing/rhinorrhea

Gastrointestinal Diarrheal

Abdominal Pain

Nausea

Vomiting

Laboratory Raisedmast cell tryptase

a Adapted from Gold et al. [9].

As part of the NIP, any adverse event following immunization

(AEFI) can be reported via appropriatestateor territory procedures.

All reports are forwarded to the centralizednational body, the Ther-

apeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Likewise, reports directly to

the TGA are redirectedbackto SAEFVICfor local clinic follow-up and

evaluation[3]. Anaphylaxis is a rare but potentially life-threatening

AEFI [4], with an estimated incidence of approximately one case

per million vaccine doses [5,6].It can manifest in a wide constella-

tion of non-specific symptoms. This variability in presentation can

make it difficult to differentiate between anaphylaxis and other

isolated allergic AEFI such as urticaria or angioedema[7]. Anaphy-

laxis is usually an immediate IgE-mediatedphenomenon,requiring

allergy workup including skin prick and intradermal testing and if

indicated supervised vaccine challenge(s)[8] (Table 1).

The Brighton Collaboration is an internationally recognized

body who developed a case definition for anaphylaxis as an AEFI

(Table 1), outlining levels of diagnostic certainty (Table 2) [9].

By providing a standardized objective definition to apply to AEFI

reports, it is hoped that the accuracy of reports can be verified

and that standardizedmanagementacrossthe pediatric population

would prove easier to disseminate and implement.

Surveillance of Adverse Events Following Vaccination In the

Community (SAFEVIC) is a passive surveillance system monitor-

ing all AEFI across the state of Victoria, Australia. Established in

May 2007, it provides specialized outpatient servicesfor both chil-

dren and adults [10]. SAEFVIC maintains a databaseof all reported

adverse events and the follow-up details of each case. The pop-

ulation of Victoria, Australia, in 2013 included over 1.05 million

children under 18 years of age [11].

The primary aim of this study was to accurately detail the

occurrence, diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis post-

immunization by applying the Brighton case definition to all

reported pediatric anaphylaxis cases in the SAFEVIC database.A

secondary aim was to review which vaccines were temporally

associatedwith anaphylaxis,vaccinespecific incidence rates,man-

agementstrategies(e.g.use of adrenaline) and outcome.

Table 1

Casevaccination demographics.

Gender Age at vaccine(years) Vaccine NAME Dose No. BCCD level Adrenaline administered

Male 8.7 Fluvax 1 Level 2 Y

Female 16.5 Gardasil 2 Level 2 N

Male 4.7 Infanrix-IPV, Priorix 4, 3 Level 2 Y

Female 16.0 Gardasil 3 Level 1 N

Male 4.1 Infanrix-IPV, Priorix 4, 2 Level 2 Y

Male 1.3 Varilrix 1 Level 2 Y

Female 1.0 Priorix 1 Level 2 N

Female 0.4 Infanrix Hexa, Prevenar,RotaTeq 2, 2, 2 Level 1 Y

Female 4.0 Infanrix-IPV, Priorix 4, 2 Level 1 Y

Male 13.4 H-B-Vax II Adult formulation 2 Level 2 Y

Female 12.8 H-B-Vax II Adult formulation, Gardasil 2, 3 Level 2 Y

Male 4.9 Infanrix-IPV, Priorix 4, 2 Level 2 Y

Male 8.4 Twinrix Junior (360/10),Typherix 1, 1 Level 2 Y

Female 7.7 Panvax H1N1 2 Level 2 Y

Female 10.6 Fluvax 1 Level 2 N

Male 13.1 H-B-Vax II Adult formulation 1 Level 2 Y

Female 9.4 Influvac 1 Level 2 Y

Female 1.3 Prevenar 13 4 Level 1 Y

Female 16.2 Boostrix 1 Level 2 Y

Male 0.6 Infanrix Hexa, Prevenar13 2, 2 Level 1 N

Male 0.6 Infanrix Hexa 3 Level 1 Y

Female 15.3 Boostrix 1 Level 3 Y

Male 0.9 Vaxigrip Jr 1 Level 1 N

Female 0.3 Infanrix Hexa, Rotateq,Prevenar13 2,2,2 Level 1 N

Male 4.3 Infanrix-IPV, Priorix 4, 2 Level 1 Y

Table 2

BCCD symptom presentationsof anaphylaxisa.

Category Major Minor

Dermatological/Mucosal Generalizedurticaria/erythema

Angioedema(localized/generalized)

Generalizedpruritus with skin rash

Generalizedpruritus without skin rash

Generalizedprickle sensation

Localized injection site urticaria

Red/itchy eyes

Cardiovascular Measured hypotension

Shock (clinical diagnosiswith ≥3 of tachycardia,cap

refill >3s, reducedcentral pulse volume, decreased

level of consciousness)

Reducedperipheral circulation (≥2 tachycardia,capillary refill >3s

without hypotension,decreasedlevel of consciousness)

Respiratory Bilateral wheeze

Stridor

Upper airway swelling

Respiratorydistress(>2tachypnea,accessorymuscle

use, recession,cyanosis,grunting)

Persistentdry cough

Hoarse voice

Difficulty breathingwithout wheeze/stridor

Sensationof throat closure

Sneezing/rhinorrhea

Gastrointestinal Diarrheal

Abdominal Pain

Nausea

Vomiting

Laboratory Raisedmast cell tryptase

a Adapted from Gold et al. [9].

As part of the NIP, any adverse event following immunization

(AEFI) can be reported via appropriatestateor territory procedures.

All reports are forwarded to the centralizednational body, the Ther-

apeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Likewise, reports directly to

the TGA are redirectedbackto SAEFVICfor local clinic follow-up and

evaluation[3]. Anaphylaxis is a rare but potentially life-threatening

AEFI [4], with an estimated incidence of approximately one case

per million vaccine doses [5,6].It can manifest in a wide constella-

tion of non-specific symptoms. This variability in presentation can

make it difficult to differentiate between anaphylaxis and other

isolated allergic AEFI such as urticaria or angioedema[7]. Anaphy-

laxis is usually an immediate IgE-mediatedphenomenon,requiring

allergy workup including skin prick and intradermal testing and if

indicated supervised vaccine challenge(s)[8] (Table 1).

The Brighton Collaboration is an internationally recognized

body who developed a case definition for anaphylaxis as an AEFI

(Table 1), outlining levels of diagnostic certainty (Table 2) [9].

By providing a standardized objective definition to apply to AEFI

reports, it is hoped that the accuracy of reports can be verified

and that standardizedmanagementacrossthe pediatric population

would prove easier to disseminate and implement.

Surveillance of Adverse Events Following Vaccination In the

Community (SAFEVIC) is a passive surveillance system monitor-

ing all AEFI across the state of Victoria, Australia. Established in

May 2007, it provides specialized outpatient servicesfor both chil-

dren and adults [10]. SAEFVIC maintains a databaseof all reported

adverse events and the follow-up details of each case. The pop-

ulation of Victoria, Australia, in 2013 included over 1.05 million

children under 18 years of age [11].

The primary aim of this study was to accurately detail the

occurrence, diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis post-

immunization by applying the Brighton case definition to all

reported pediatric anaphylaxis cases in the SAFEVIC database.A

secondary aim was to review which vaccines were temporally

associatedwith anaphylaxis,vaccinespecific incidence rates,man-

agementstrategies(e.g.use of adrenaline) and outcome.

1604 D.R.Chenget al. / Vaccine33 (2015)1602–1607

Table 3

BCCD level of certainty for anaphylaxis.

BCCD level of certainty Diagnosticcriteria Number of casesmeeting criteria

Level 1 ≥1 major dermatologicalAND ≥1 major cardiovascular 0

≥1 major dermatological≥AND 1 major respiratory 9

Level 2 ≥1 major cardiovascularAND ≥1 major respiratory 0

≥1 major cardiovascular/respiratoryAND ≥1 minor criterion involving ≥1 different system 3

≥1 major dermatologicalAND ≥1 minor cardiovascular/respiratory 12

Level 3 ≥1 minor cardiovascularOR respiratory AND ≤1 minor criteria from ≥2 different systems 1

Level 4 Reportedanaphylaxiswith insufficient evidenceto meet casedefinition 1

2. Methods

Pediatric cases (under 18 years old) with suspected anaphy-

laxis AEFI reported to SAFEVICbetween May 2007 to May 2013 (six

years)were included. Searchterms used to selectreports for review

included all terms currently within BCCD criteria such as urticar-

ial, hypotension, tachycardiaor angioedema.Historical events (i.e.

AEFI occurring before May 2007) reported during the study period

were excluded due to a lack of reliable and objective data available

prior to the establishmentof a standardizedassessmentprocessvia

SAEFVIC.

All events suspectedor reported as anaphylaxis were followed

up within 24 h of initial report via trained SAEFVIC healthcare

professionals. Data collected included demographic information,

medical history, medications, immunization status and previous

AEFI. Clinical descriptions and details surrounding the current

adverseevent,including managementand final outcome were also

sourced from the family and treating physician and/or hospital

medical records.All caseswere offered a specialist clinic follow-up

appointment and assessment prior to any subsequent vaccina-

tion. Any incomplete information was recollectedfrom consenting

reporters, parents and healthcareworkers prior to final analysis.

The Brighton Collaboration Case Definition (BCCD) for ana-

phylaxis AEFI (Table 1) was then retrospectively applied by two

independentreviewers (DC and NC), who were not involved in any

SAEFVIC assessmentsat time of initial reporting, applying a level of

diagnostic certainty for each case (Table 2).

Vaccine specific dose administration data from the Australian

Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR) and National HPV Vacci-

nation Program Registerwere used as the denominator to calculate

incidence estimates. Data was entered into a Microsoft Access

Database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and ana-

lyzed with STATA 12.0 (Statacorp,TX, USA). Ethics approval was

obtained from The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne Human

ResearchEthics Committee.

3. Results

Twenty-five patients, with a total of 27 reports of anaphylaxis,

were identified in the six-year study period (Table 3). The median

age of immunization was 4.7 years (range 0.3–16.2 years), with

48%of cases male. Six cases (22.2%)were ≤12 months old when

receiving vaccination.Twenty-five of these casesmet BCCDcriteria

for anaphylaxis (Table 2), with a total of 37 vaccinesadministered.

Of these cases,nine (36%)met BCCD Level 1 diagnostic certainty,

15 (60%)Level 2 and one case Level 3 (4%).One case was deemed

Level 5 (not a case of anaphylaxis).

Thirteen cases included vaccines that are part of the routine

Australian infant and preschool immunization schedule,which has

evolved slightly through the study period [2]. The remaining 12

cases consisted of vaccines that are part of the routine Australian

secondary school immunization program. The vaccine antigens

administered included combination DTaP vaccines (DTaP com-

bined with other antigen) in 9 of 25 cases (36%).Measles mumps

rubella (MMR) vaccinewas receivedin six cases;five of whom had

concomitantvaccines(Table4). The majority of vaccines(93%)were

administered at a generalpractitioner’s(GP) primary care practice,

or at a specialist immunization nurse led local council vaccine

session. Immunization nurses also administered most secondary

school adolescentvaccines.

3.1. Anaphylaxisincidencerate

Vaccine coverageis approximately 91%at 12 months of age[12]

and 70–75%in the school program in Victoria [13]. 197,878 doses

of Infanrix IPVTM [GSK] were administered, with an incidence of

2.53 per 100,000doses [2.43,2.63].Likewise, 481,297doses of the

combination MMR vaccine were administered with an estimated

incidence of 1.25 per 100,000 doses [1.18, 1.32]. For 13-valent

pneumococcal (PCV13) vaccines, there were 498,039 doses with

an incidence of 0.6 per 100,000doses [0.55,0.65].

A total of 1,092,682vaccinedosesof Infanrix HexaTM [GSK] were

administered over the study period, yielding an estimated inci-

dence rate of 0.36 cases per 100,000 doses [0.32, 0.40, 95%CI]. A

minimum of 934,255 doses of HPV vaccines were administered

to pediatric patients within the study period, indicating an esti-

mated anaphylaxisincidence of 0.32 per 100,000doses[0.29,0.35]

(data courtesy of ACIR and the National HPV Vaccination Program

Register).

3.2. History of anaphylaxis/atopy

One infant had anaphylaxis on three separate occasions, with

different vaccines administered each time (Infanrix Hexa, Preve-

nar 13, Vaxigrip Jr). Skin tests followed by vaccine challengeswere

undertaken in an allergy clinic in a hospital setting as part of a

causality assessmentof specific vaccinesand/or components.One

formal allergy challenge was positive, with an anaphylactic reac-

tion at 40 min following Infanrix HexaTM vaccine; the challengefor

Prevenar 13 only resulted in an erythematousrash.

Five cases (20.5%)had a past history of anaphylaxis to food

items such as egg,nuts or seafood.All had already been prescribed

an epinephrine auto-injectable device, with three patients hav-

ing utilized it on a previous occasion for food related anaphylactic

episodes; however no device was used in any of the anaphylactic

AEFI cases.Eight caseshad a previous history of atopic disease;four

with asthma,six with eczemaand two with hayfever.

3.3. Time post-vaccination

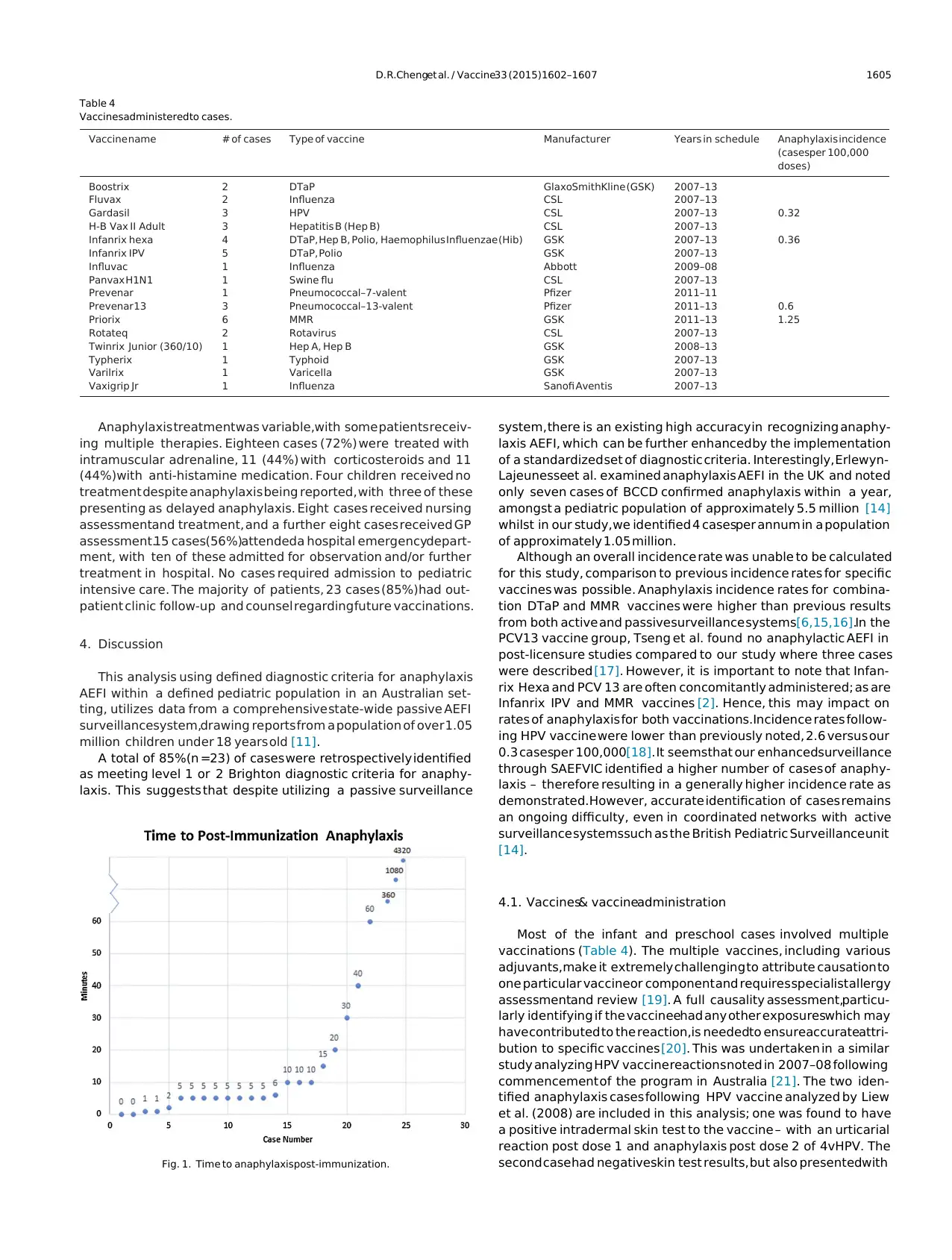

The time anaphylaxisoccurred post-immunization is detailedin

Fig. 1. Anaphylaxis in 19 cases(70%)occurred ≤30 min after immu-

nization. A further two cases presented between 30 to ≤60 min

and the remaining three caseswere greaterthan 120 min following

immunization.

Symptoms resolved within 60 min of presentation for 15 cases,

with a further six resolved within 24 h. The remaining four had

symptoms persisting beyond 24 h, with one case having ongoing

angioedemaand urticaria for the following 6-days.

Table 3

BCCD level of certainty for anaphylaxis.

BCCD level of certainty Diagnosticcriteria Number of casesmeeting criteria

Level 1 ≥1 major dermatologicalAND ≥1 major cardiovascular 0

≥1 major dermatological≥AND 1 major respiratory 9

Level 2 ≥1 major cardiovascularAND ≥1 major respiratory 0

≥1 major cardiovascular/respiratoryAND ≥1 minor criterion involving ≥1 different system 3

≥1 major dermatologicalAND ≥1 minor cardiovascular/respiratory 12

Level 3 ≥1 minor cardiovascularOR respiratory AND ≤1 minor criteria from ≥2 different systems 1

Level 4 Reportedanaphylaxiswith insufficient evidenceto meet casedefinition 1

2. Methods

Pediatric cases (under 18 years old) with suspected anaphy-

laxis AEFI reported to SAFEVICbetween May 2007 to May 2013 (six

years)were included. Searchterms used to selectreports for review

included all terms currently within BCCD criteria such as urticar-

ial, hypotension, tachycardiaor angioedema.Historical events (i.e.

AEFI occurring before May 2007) reported during the study period

were excluded due to a lack of reliable and objective data available

prior to the establishmentof a standardizedassessmentprocessvia

SAEFVIC.

All events suspectedor reported as anaphylaxis were followed

up within 24 h of initial report via trained SAEFVIC healthcare

professionals. Data collected included demographic information,

medical history, medications, immunization status and previous

AEFI. Clinical descriptions and details surrounding the current

adverseevent,including managementand final outcome were also

sourced from the family and treating physician and/or hospital

medical records.All caseswere offered a specialist clinic follow-up

appointment and assessment prior to any subsequent vaccina-

tion. Any incomplete information was recollectedfrom consenting

reporters, parents and healthcareworkers prior to final analysis.

The Brighton Collaboration Case Definition (BCCD) for ana-

phylaxis AEFI (Table 1) was then retrospectively applied by two

independentreviewers (DC and NC), who were not involved in any

SAEFVIC assessmentsat time of initial reporting, applying a level of

diagnostic certainty for each case (Table 2).

Vaccine specific dose administration data from the Australian

Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR) and National HPV Vacci-

nation Program Registerwere used as the denominator to calculate

incidence estimates. Data was entered into a Microsoft Access

Database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and ana-

lyzed with STATA 12.0 (Statacorp,TX, USA). Ethics approval was

obtained from The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne Human

ResearchEthics Committee.

3. Results

Twenty-five patients, with a total of 27 reports of anaphylaxis,

were identified in the six-year study period (Table 3). The median

age of immunization was 4.7 years (range 0.3–16.2 years), with

48%of cases male. Six cases (22.2%)were ≤12 months old when

receiving vaccination.Twenty-five of these casesmet BCCDcriteria

for anaphylaxis (Table 2), with a total of 37 vaccinesadministered.

Of these cases,nine (36%)met BCCD Level 1 diagnostic certainty,

15 (60%)Level 2 and one case Level 3 (4%).One case was deemed

Level 5 (not a case of anaphylaxis).

Thirteen cases included vaccines that are part of the routine

Australian infant and preschool immunization schedule,which has

evolved slightly through the study period [2]. The remaining 12

cases consisted of vaccines that are part of the routine Australian

secondary school immunization program. The vaccine antigens

administered included combination DTaP vaccines (DTaP com-

bined with other antigen) in 9 of 25 cases (36%).Measles mumps

rubella (MMR) vaccinewas receivedin six cases;five of whom had

concomitantvaccines(Table4). The majority of vaccines(93%)were

administered at a generalpractitioner’s(GP) primary care practice,

or at a specialist immunization nurse led local council vaccine

session. Immunization nurses also administered most secondary

school adolescentvaccines.

3.1. Anaphylaxisincidencerate

Vaccine coverageis approximately 91%at 12 months of age[12]

and 70–75%in the school program in Victoria [13]. 197,878 doses

of Infanrix IPVTM [GSK] were administered, with an incidence of

2.53 per 100,000doses [2.43,2.63].Likewise, 481,297doses of the

combination MMR vaccine were administered with an estimated

incidence of 1.25 per 100,000 doses [1.18, 1.32]. For 13-valent

pneumococcal (PCV13) vaccines, there were 498,039 doses with

an incidence of 0.6 per 100,000doses [0.55,0.65].

A total of 1,092,682vaccinedosesof Infanrix HexaTM [GSK] were

administered over the study period, yielding an estimated inci-

dence rate of 0.36 cases per 100,000 doses [0.32, 0.40, 95%CI]. A

minimum of 934,255 doses of HPV vaccines were administered

to pediatric patients within the study period, indicating an esti-

mated anaphylaxisincidence of 0.32 per 100,000doses[0.29,0.35]

(data courtesy of ACIR and the National HPV Vaccination Program

Register).

3.2. History of anaphylaxis/atopy

One infant had anaphylaxis on three separate occasions, with

different vaccines administered each time (Infanrix Hexa, Preve-

nar 13, Vaxigrip Jr). Skin tests followed by vaccine challengeswere

undertaken in an allergy clinic in a hospital setting as part of a

causality assessmentof specific vaccinesand/or components.One

formal allergy challenge was positive, with an anaphylactic reac-

tion at 40 min following Infanrix HexaTM vaccine; the challengefor

Prevenar 13 only resulted in an erythematousrash.

Five cases (20.5%)had a past history of anaphylaxis to food

items such as egg,nuts or seafood.All had already been prescribed

an epinephrine auto-injectable device, with three patients hav-

ing utilized it on a previous occasion for food related anaphylactic

episodes; however no device was used in any of the anaphylactic

AEFI cases.Eight caseshad a previous history of atopic disease;four

with asthma,six with eczemaand two with hayfever.

3.3. Time post-vaccination

The time anaphylaxisoccurred post-immunization is detailedin

Fig. 1. Anaphylaxis in 19 cases(70%)occurred ≤30 min after immu-

nization. A further two cases presented between 30 to ≤60 min

and the remaining three caseswere greaterthan 120 min following

immunization.

Symptoms resolved within 60 min of presentation for 15 cases,

with a further six resolved within 24 h. The remaining four had

symptoms persisting beyond 24 h, with one case having ongoing

angioedemaand urticaria for the following 6-days.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

D.R.Chenget al. / Vaccine33 (2015)1602–1607 1605

Table 4

Vaccinesadministeredto cases.

Vaccine name # of cases Type of vaccine Manufacturer Years in schedule Anaphylaxis incidence

(casesper 100,000

doses)

Boostrix 2 DTaP GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) 2007–13

Fluvax 2 Influenza CSL 2007–13

Gardasil 3 HPV CSL 2007–13 0.32

H-B Vax II Adult 3 Hepatitis B (Hep B) CSL 2007–13

Infanrix hexa 4 DTaP, Hep B, Polio, Haemophilus Influenzae (Hib) GSK 2007–13 0.36

Infanrix IPV 5 DTaP, Polio GSK 2007–13

Influvac 1 Influenza Abbott 2009–08

Panvax H1N1 1 Swine flu CSL 2007–13

Prevenar 1 Pneumococcal–7-valent Pfizer 2011–11

Prevenar 13 3 Pneumococcal–13-valent Pfizer 2011–13 0.6

Priorix 6 MMR GSK 2011–13 1.25

Rotateq 2 Rotavirus CSL 2007–13

Twinrix Junior (360/10) 1 Hep A, Hep B GSK 2008–13

Typherix 1 Typhoid GSK 2007–13

Varilrix 1 Varicella GSK 2007–13

Vaxigrip Jr 1 Influenza Sanofi Aventis 2007–13

Anaphylaxis treatmentwas variable,with some patients receiv-

ing multiple therapies. Eighteen cases (72%) were treated with

intramuscular adrenaline, 11 (44%) with corticosteroids and 11

(44%)with anti-histamine medication. Four children received no

treatment despite anaphylaxis being reported, with three of these

presenting as delayed anaphylaxis. Eight cases received nursing

assessmentand treatment, and a further eight cases received GP

assessment.15 cases(56%)attendeda hospital emergencydepart-

ment, with ten of these admitted for observation and/or further

treatment in hospital. No cases required admission to pediatric

intensive care. The majority of patients, 23 cases (85%)had out-

patient clinic follow-up and counsel regarding future vaccinations.

4. Discussion

This analysis using defined diagnostic criteria for anaphylaxis

AEFI within a defined pediatric population in an Australian set-

ting, utilizes data from a comprehensive state-wide passive AEFI

surveillancesystem,drawing reports from a population of over 1.05

million children under 18 years old [11].

A total of 85%(n =23) of cases were retrospectively identified

as meeting level 1 or 2 Brighton diagnostic criteria for anaphy-

laxis. This suggests that despite utilizing a passive surveillance

Fig. 1. Time to anaphylaxispost-immunization.

system, there is an existing high accuracy in recognizing anaphy-

laxis AEFI, which can be further enhanced by the implementation

of a standardized set of diagnostic criteria. Interestingly, Erlewyn-

Lajeunesseet al. examined anaphylaxis AEFI in the UK and noted

only seven cases of BCCD confirmed anaphylaxis within a year,

amongst a pediatric population of approximately 5.5 million [14]

whilst in our study,we identified 4 casesper annum in a population

of approximately 1.05 million.

Although an overall incidence rate was unable to be calculated

for this study, comparison to previous incidence rates for specific

vaccines was possible. Anaphylaxis incidence rates for combina-

tion DTaP and MMR vaccines were higher than previous results

from both active and passivesurveillance systems[6,15,16].In the

PCV13 vaccine group, Tseng et al. found no anaphylactic AEFI in

post-licensure studies compared to our study where three cases

were described [17]. However, it is important to note that Infan-

rix Hexa and PCV 13 are often concomitantly administered; as are

Infanrix IPV and MMR vaccines [2]. Hence, this may impact on

rates of anaphylaxis for both vaccinations.Incidence rates follow-

ing HPV vaccine were lower than previously noted, 2.6 versus our

0.3 casesper 100,000[18]. It seemsthat our enhancedsurveillance

through SAEFVIC identified a higher number of cases of anaphy-

laxis – therefore resulting in a generally higher incidence rate as

demonstrated.However, accurate identification of cases remains

an ongoing difficulty, even in coordinated networks with active

surveillance systemssuch as the British Pediatric Surveillanceunit

[14].

4.1. Vaccines& vaccineadministration

Most of the infant and preschool cases involved multiple

vaccinations (Table 4). The multiple vaccines, including various

adjuvants,make it extremely challenging to attribute causation to

one particular vaccineor component and requires specialist allergy

assessmentand review [19]. A full causality assessment,particu-

larly identifying if the vaccineehad any other exposureswhich may

have contributed to the reaction,is neededto ensureaccurateattri-

bution to specific vaccines [20]. This was undertaken in a similar

study analyzing HPV vaccine reactions noted in 2007–08 following

commencement of the program in Australia [21]. The two iden-

tified anaphylaxis cases following HPV vaccine analyzed by Liew

et al. (2008) are included in this analysis; one was found to have

a positive intradermal skin test to the vaccine – with an urticarial

reaction post dose 1 and anaphylaxis post dose 2 of 4vHPV. The

second casehad negativeskin test results, but also presentedwith

Table 4

Vaccinesadministeredto cases.

Vaccine name # of cases Type of vaccine Manufacturer Years in schedule Anaphylaxis incidence

(casesper 100,000

doses)

Boostrix 2 DTaP GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) 2007–13

Fluvax 2 Influenza CSL 2007–13

Gardasil 3 HPV CSL 2007–13 0.32

H-B Vax II Adult 3 Hepatitis B (Hep B) CSL 2007–13

Infanrix hexa 4 DTaP, Hep B, Polio, Haemophilus Influenzae (Hib) GSK 2007–13 0.36

Infanrix IPV 5 DTaP, Polio GSK 2007–13

Influvac 1 Influenza Abbott 2009–08

Panvax H1N1 1 Swine flu CSL 2007–13

Prevenar 1 Pneumococcal–7-valent Pfizer 2011–11

Prevenar 13 3 Pneumococcal–13-valent Pfizer 2011–13 0.6

Priorix 6 MMR GSK 2011–13 1.25

Rotateq 2 Rotavirus CSL 2007–13

Twinrix Junior (360/10) 1 Hep A, Hep B GSK 2008–13

Typherix 1 Typhoid GSK 2007–13

Varilrix 1 Varicella GSK 2007–13

Vaxigrip Jr 1 Influenza Sanofi Aventis 2007–13

Anaphylaxis treatmentwas variable,with some patients receiv-

ing multiple therapies. Eighteen cases (72%) were treated with

intramuscular adrenaline, 11 (44%) with corticosteroids and 11

(44%)with anti-histamine medication. Four children received no

treatment despite anaphylaxis being reported, with three of these

presenting as delayed anaphylaxis. Eight cases received nursing

assessmentand treatment, and a further eight cases received GP

assessment.15 cases(56%)attendeda hospital emergencydepart-

ment, with ten of these admitted for observation and/or further

treatment in hospital. No cases required admission to pediatric

intensive care. The majority of patients, 23 cases (85%)had out-

patient clinic follow-up and counsel regarding future vaccinations.

4. Discussion

This analysis using defined diagnostic criteria for anaphylaxis

AEFI within a defined pediatric population in an Australian set-

ting, utilizes data from a comprehensive state-wide passive AEFI

surveillancesystem,drawing reports from a population of over 1.05

million children under 18 years old [11].

A total of 85%(n =23) of cases were retrospectively identified

as meeting level 1 or 2 Brighton diagnostic criteria for anaphy-

laxis. This suggests that despite utilizing a passive surveillance

Fig. 1. Time to anaphylaxispost-immunization.

system, there is an existing high accuracy in recognizing anaphy-

laxis AEFI, which can be further enhanced by the implementation

of a standardized set of diagnostic criteria. Interestingly, Erlewyn-

Lajeunesseet al. examined anaphylaxis AEFI in the UK and noted

only seven cases of BCCD confirmed anaphylaxis within a year,

amongst a pediatric population of approximately 5.5 million [14]

whilst in our study,we identified 4 casesper annum in a population

of approximately 1.05 million.

Although an overall incidence rate was unable to be calculated

for this study, comparison to previous incidence rates for specific

vaccines was possible. Anaphylaxis incidence rates for combina-

tion DTaP and MMR vaccines were higher than previous results

from both active and passivesurveillance systems[6,15,16].In the

PCV13 vaccine group, Tseng et al. found no anaphylactic AEFI in

post-licensure studies compared to our study where three cases

were described [17]. However, it is important to note that Infan-

rix Hexa and PCV 13 are often concomitantly administered; as are

Infanrix IPV and MMR vaccines [2]. Hence, this may impact on

rates of anaphylaxis for both vaccinations.Incidence rates follow-

ing HPV vaccine were lower than previously noted, 2.6 versus our

0.3 casesper 100,000[18]. It seemsthat our enhancedsurveillance

through SAEFVIC identified a higher number of cases of anaphy-

laxis – therefore resulting in a generally higher incidence rate as

demonstrated.However, accurate identification of cases remains

an ongoing difficulty, even in coordinated networks with active

surveillance systemssuch as the British Pediatric Surveillanceunit

[14].

4.1. Vaccines& vaccineadministration

Most of the infant and preschool cases involved multiple

vaccinations (Table 4). The multiple vaccines, including various

adjuvants,make it extremely challenging to attribute causation to

one particular vaccineor component and requires specialist allergy

assessmentand review [19]. A full causality assessment,particu-

larly identifying if the vaccineehad any other exposureswhich may

have contributed to the reaction,is neededto ensureaccurateattri-

bution to specific vaccines [20]. This was undertaken in a similar

study analyzing HPV vaccine reactions noted in 2007–08 following

commencement of the program in Australia [21]. The two iden-

tified anaphylaxis cases following HPV vaccine analyzed by Liew

et al. (2008) are included in this analysis; one was found to have

a positive intradermal skin test to the vaccine – with an urticarial

reaction post dose 1 and anaphylaxis post dose 2 of 4vHPV. The

second casehad negativeskin test results, but also presentedwith

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1606 D.R.Chenget al. / Vaccine33 (2015)1602–1607

an urticarial reaction post dose 1 and anaphylaxis post dose 2 of

4vHPV.

It is probable that the infant who had multiple presentationsof

anaphylaxis was not classical immunoglobulin-E (IgE) mediated,

with IgG and other inflammatory pathways postulated [22]. This

hypothesis of non-IgE pathways, is further supported by the four

cases of anaphylaxis presenting >60min after vaccination; this is

consistent with previous studies indicating that a delayed non-IgE

mediated reaction or an IgE mediated reaction from exposure to

another allergen after immunization are the most likely explana-

tions for delayed anaphylaxis presentation [6,21].

4.2. Medical & allergichistory

It is also important to consider AEFI in the context of back-

ground rates of conditions that may be assessedincorrectly as an

AEFI. SAEFVIC has reviewed the backgroundrates of certain condi-

tions in Victoria which are commonly attributed to vaccineAEFIs –

specifically in relation to HPV vaccine introduction in males [23].

For example, both allergies and anaphylaxis are increasing

across westernized and urbanized populations, with some of the

highest rates (up to 10% of 12 month olds have egg allergy) of

both conditions identified in the authors’stateof Victoria, Australia

[24]. However, although 19%(n =5) of patients in this study had a

proven food allergy, anaphylaxis incidence rates for vaccineswere

still extremely low, suggestingminimal correlation. Furthermore,

although a history of atopic disease (32%)was more common in

the study than the general population (16.6%)[5], there was no

correlation with a definitive clinical outcome.

The evidence to support the link between atopic history

and increased risk of anaphylaxis AEFI is mixed [25]. Gruber

et al. demonstrated that there was no identifiable link between

occurrenceor severity of atopic diseaseand early childhood immu-

nization. Cumulativevaccinedoseswere shown to slightly decrease

the severity of atopic dermatitis, thought to be secondary to vac-

cine antigen“education”of the immune systemand shifting it away

from a Th2 immune response [26]. This corresponds to previous

findings investigating risk factors for anaphylaxis in combination

MMR vaccines[27].

4.3. Futurepractice

Whilst the BCCDcriteria provides a standardizedcasedefinition

to aid in the diagnosis of anaphylaxis,its clinical application in the

field can be difficult [9]. Passive surveillance systems are mostly

utilized by health professionals,but can also include reports from

community membersand parents.The availability or knowledge of

specific criteria is variable,resulting in a wide rangeof clinical data.

Where possible,SAEFVICcontactsall serious adversereporters and

vaccines for serious AEFI such as anaphylaxis.This enhanced pas-

sive surveillance data will improve on the capacity to categorize

anaphylaxis and make an accuratediagnosis.

Healthcare professionals reported all our SAEFVIC cases,some

of whom were familiar with BCCD criteria. Nonetheless, two

distinct patterns emerged suggesting clinical difficulty with the

application of BCCD. Each case involved at least a dermatolog-

ical or respiratory symptom – suggesting that these symptoms

were likely the most easily diagnosed or recognized,especially in

the community setting. Secondly, there was a relative dearth of

cardiovascular symptoms, with only three minor cardiovascular

symptoms reported in total. The definition of clinical cardiac symp-

toms requires both clinical assessmentand measurementsof blood

pressure,heart rate and capillary refill. The lack of available equip-

ment or awareness of these symptoms could have contributed to

the difficulty of determining and thus recording cardiovascular

symptoms in a community setting.

Application of the Brighton criteria to specific AEFI of inter-

est has been identified as a challenge [9]. The development of a

prospectivechecklist and glossaryof terms that could be instituted

state-wide where pediatric immunization is delivered would be

ideal to ensure uniform reporting.

Current practice guidelines suggestthat patients are observed

for at least 15 min for any adverse reaction [1]; the timing of our

cases would indicate that there is a possibility of missing ana-

phylactic episodes.Patients who have had a previous anaphylactic

reaction should have a specialized assessmentas detailed above.

This includes a discussion regarding risks and benefits of immu-

nization as anaphylaxis is usually considered a contraindication

to further vaccine doses. Close observation in a hospital setting is

required. Future vaccinations with the same vaccines are usually

contraindicatedif a true anaphylacticAEFI has been confirmed and

the antigen identified [28]. This is not the case for isolated hyper-

sensitivity reactions such as urticaria; thus it is paramount that

casesare correctly classifiedto ensureappropriate follow-up in the

future.

The managementof anaphylaxisshould always err on the side of

caution, even if it is not immediately clear whether BCCD criteria

are met but the patient is clinically compromised. Intramuscular

adrenalineis first line treatmentand should be given if indicated,as

was the casein the majority of thesecases.Adrenaline has minimal

side effects,including in caseswhich on later review are considered

not to be anaphylaxis.

5. Limitations

The use of a passive surveillance system and potential under-

reporting of AEFI, incomplete data of all vaccines administered

acrossthe study period (2007–2013),the ever-changingAustralian

immunization schedule,the large number of unique vaccines and

multiple time points involved (e.g. some vaccines are three-dose

schedules) means that true overall AEFI incidence rates are dif-

ficult to determine. Nonetheless, the comprehensive dataset and

robust reporting process employed by SAEFVIC coupled with inci-

dence rates of certain specific vaccines and data regarding overall

coverageof routine vaccinesincreasethe reliability of findings.

Diagnosis of anaphylaxis in the study is dependent on BCCD

criteria, which may overestimate numbers of cases. The validity

of the diagnostic criteria has been demonstrated in other studies

[18,29]. Care needs to be taken when drawing conclusions from

the above data, especially if estimating rates and trends or deter-

mining safetyof individual vaccines.The number of adverseevents

reported to SAEFVIC may reflect somewhat on the number of doses

of a specific vaccine administered, but interpreting safety trends

with a rare adverseeventlike anaphylaxisis complex. Another lim-

itation of this study is the analysis of allergy testing (if applicable)

for allergy casesidentified.This was beyondthe scopeof this report,

with further researchdetailing our vaccinechallengesin confirmed

casesof anaphylaxis to be detailed in future publications.

6. Conclusion

This is a comprehensive case series of a serious AEFI, anaphy-

laxis, in the pediatric population. We identified 27 cases, with

approximately 90%receiving adrenaline and no serious sequelae

identified. Diagnosticcriteria are useful but can be difficult to apply

in a passive vaccine surveillance system,with the main limitation

being a lack of information on cardiovascular status. Healthcare

professionals and vaccinees/parentsshould be aware that onset of

anaphylaxiscan be delayedmore than 30 min following immuniza-

tion and prompt administration of adrenaline is recommended if

the diagnosis is considered.

an urticarial reaction post dose 1 and anaphylaxis post dose 2 of

4vHPV.

It is probable that the infant who had multiple presentationsof

anaphylaxis was not classical immunoglobulin-E (IgE) mediated,

with IgG and other inflammatory pathways postulated [22]. This

hypothesis of non-IgE pathways, is further supported by the four

cases of anaphylaxis presenting >60min after vaccination; this is

consistent with previous studies indicating that a delayed non-IgE

mediated reaction or an IgE mediated reaction from exposure to

another allergen after immunization are the most likely explana-

tions for delayed anaphylaxis presentation [6,21].

4.2. Medical & allergichistory

It is also important to consider AEFI in the context of back-

ground rates of conditions that may be assessedincorrectly as an

AEFI. SAEFVIC has reviewed the backgroundrates of certain condi-

tions in Victoria which are commonly attributed to vaccineAEFIs –

specifically in relation to HPV vaccine introduction in males [23].

For example, both allergies and anaphylaxis are increasing

across westernized and urbanized populations, with some of the

highest rates (up to 10% of 12 month olds have egg allergy) of

both conditions identified in the authors’stateof Victoria, Australia

[24]. However, although 19%(n =5) of patients in this study had a

proven food allergy, anaphylaxis incidence rates for vaccineswere

still extremely low, suggestingminimal correlation. Furthermore,

although a history of atopic disease (32%)was more common in

the study than the general population (16.6%)[5], there was no

correlation with a definitive clinical outcome.

The evidence to support the link between atopic history

and increased risk of anaphylaxis AEFI is mixed [25]. Gruber

et al. demonstrated that there was no identifiable link between

occurrenceor severity of atopic diseaseand early childhood immu-

nization. Cumulativevaccinedoseswere shown to slightly decrease

the severity of atopic dermatitis, thought to be secondary to vac-

cine antigen“education”of the immune systemand shifting it away

from a Th2 immune response [26]. This corresponds to previous

findings investigating risk factors for anaphylaxis in combination

MMR vaccines[27].

4.3. Futurepractice

Whilst the BCCDcriteria provides a standardizedcasedefinition

to aid in the diagnosis of anaphylaxis,its clinical application in the

field can be difficult [9]. Passive surveillance systems are mostly

utilized by health professionals,but can also include reports from

community membersand parents.The availability or knowledge of

specific criteria is variable,resulting in a wide rangeof clinical data.

Where possible,SAEFVICcontactsall serious adversereporters and

vaccines for serious AEFI such as anaphylaxis.This enhanced pas-

sive surveillance data will improve on the capacity to categorize

anaphylaxis and make an accuratediagnosis.

Healthcare professionals reported all our SAEFVIC cases,some

of whom were familiar with BCCD criteria. Nonetheless, two

distinct patterns emerged suggesting clinical difficulty with the

application of BCCD. Each case involved at least a dermatolog-

ical or respiratory symptom – suggesting that these symptoms

were likely the most easily diagnosed or recognized,especially in

the community setting. Secondly, there was a relative dearth of

cardiovascular symptoms, with only three minor cardiovascular

symptoms reported in total. The definition of clinical cardiac symp-

toms requires both clinical assessmentand measurementsof blood

pressure,heart rate and capillary refill. The lack of available equip-

ment or awareness of these symptoms could have contributed to

the difficulty of determining and thus recording cardiovascular

symptoms in a community setting.

Application of the Brighton criteria to specific AEFI of inter-

est has been identified as a challenge [9]. The development of a

prospectivechecklist and glossaryof terms that could be instituted

state-wide where pediatric immunization is delivered would be

ideal to ensure uniform reporting.

Current practice guidelines suggestthat patients are observed

for at least 15 min for any adverse reaction [1]; the timing of our

cases would indicate that there is a possibility of missing ana-

phylactic episodes.Patients who have had a previous anaphylactic

reaction should have a specialized assessmentas detailed above.

This includes a discussion regarding risks and benefits of immu-

nization as anaphylaxis is usually considered a contraindication

to further vaccine doses. Close observation in a hospital setting is

required. Future vaccinations with the same vaccines are usually

contraindicatedif a true anaphylacticAEFI has been confirmed and

the antigen identified [28]. This is not the case for isolated hyper-

sensitivity reactions such as urticaria; thus it is paramount that

casesare correctly classifiedto ensureappropriate follow-up in the

future.

The managementof anaphylaxisshould always err on the side of

caution, even if it is not immediately clear whether BCCD criteria

are met but the patient is clinically compromised. Intramuscular

adrenalineis first line treatmentand should be given if indicated,as

was the casein the majority of thesecases.Adrenaline has minimal

side effects,including in caseswhich on later review are considered

not to be anaphylaxis.

5. Limitations

The use of a passive surveillance system and potential under-

reporting of AEFI, incomplete data of all vaccines administered

acrossthe study period (2007–2013),the ever-changingAustralian

immunization schedule,the large number of unique vaccines and

multiple time points involved (e.g. some vaccines are three-dose

schedules) means that true overall AEFI incidence rates are dif-

ficult to determine. Nonetheless, the comprehensive dataset and

robust reporting process employed by SAEFVIC coupled with inci-

dence rates of certain specific vaccines and data regarding overall

coverageof routine vaccinesincreasethe reliability of findings.

Diagnosis of anaphylaxis in the study is dependent on BCCD

criteria, which may overestimate numbers of cases. The validity

of the diagnostic criteria has been demonstrated in other studies

[18,29]. Care needs to be taken when drawing conclusions from

the above data, especially if estimating rates and trends or deter-

mining safetyof individual vaccines.The number of adverseevents

reported to SAEFVIC may reflect somewhat on the number of doses

of a specific vaccine administered, but interpreting safety trends

with a rare adverseeventlike anaphylaxisis complex. Another lim-

itation of this study is the analysis of allergy testing (if applicable)

for allergy casesidentified.This was beyondthe scopeof this report,

with further researchdetailing our vaccinechallengesin confirmed

casesof anaphylaxis to be detailed in future publications.

6. Conclusion

This is a comprehensive case series of a serious AEFI, anaphy-

laxis, in the pediatric population. We identified 27 cases, with

approximately 90%receiving adrenaline and no serious sequelae

identified. Diagnosticcriteria are useful but can be difficult to apply

in a passive vaccine surveillance system,with the main limitation

being a lack of information on cardiovascular status. Healthcare

professionals and vaccinees/parentsshould be aware that onset of

anaphylaxiscan be delayedmore than 30 min following immuniza-

tion and prompt administration of adrenaline is recommended if

the diagnosis is considered.

D.R.Chenget al. / Vaccine33 (2015)1602–1607 1607

Acknowledgements

Neal Halsey, Mandira Hiremath, Alissa McMinn for assistance

and advice in the study. We also thank the staff at ACIR and the

National HPV Vaccination Program Register for assistancein data

provision for the study.

Conflict of interest:The authors wish to confirm that there are

no known conflicts of interest associatedwith this publication and

there has been no significant financial support for this work that

could have influenced its outcome.

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved

by all named authors and that there are no other persons who

satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further

confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been

approved by all of us. DC was the coordinating author, responsible

for design of the study, data collection and data analysis as well

as writing and finalizing the manuscript for submission. NC was

responsible for conceptualization of the study, data analysis and

writing/editing/finalizing the manuscript. KP, SC, MD and JB were

responsible for writing/editing the manuscript.

All authors confirm that they have given due consideration to

the protection of intellectual property associated with this work

and that there are no impediments to publication, including the

timing of publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so

doing we confirm that we have followed the regulations of our

institutions concerning intellectual property.

References

[1] National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). The Australian

Immunisation Handbook. 10th ed. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia;

2013.

[2] Department of Health, State Government of Victoria, Australia. Immun-

isation Schedule Victoria. 2014. Available at: http://www.health.vic.gov.au/

immunisation/factsheets/schedule-victoria.htm,accessed1 August 2014.

[3] Clothier HJ, Crawford NW, Kempe A, Buttery JP. Surveillanceof adverseevents

following immunisation: the model of SAEFVIC,Victoria. Commun Dis Intell Q

Rep 2011;35:294–8.

[4] RuggebergJU, Gold MS, Bayas JM, Blum MD, Bonhoeffer J, Friedlander S, et al.

Anaphylaxis: case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and

presentationof immunization safetydata.Vaccine 2007;25:5675–84.

[5] Bohlke K, Davis RL, Marcy SM, Braun MM, DeStefano F, Black SB, et al.

Risk of anaphylaxis after vaccination of children and adolescents.Pediatrics

2003;112:815–20.

[6] Patja A, Davidkin I, Kurki T, Kallio MJ, Valle M, Peltola H. Seriousadverseevents

after measles–mumps–rubellavaccinationduring a fourteen-yearprospective

follow-up. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19:1127–34.

[7] Caubet JC, Siegrist CA, Eigenmann PA. Allergic reactions and vaccines: distin-

guishing true and false reactions.Rev Med Suisse2009;5:416–9.

[8] Gold M. A clinical approach to investigationof suspectedvaccineanaphylaxis.

Curr Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;25:68–70.

[9] Gold MS, Gidudu J, Erlewyn-LajeunesseM, Law B. Brighton CollaborationWork-

ing Group on A. Can the Brighton Collaboration case definitions be used to

improve the quality of AdverseEventFollowing Immunization (AEFI) reporting.

Anaphylaxis as a casestudy. Vaccine 2010;28:4487–98.

[10] Clothier HJ, Crawford NW, Kempe A, Buttery JP. Surveillanceof adverseevents

following immunisation: The model of SAEFVIC Victoria. Commun Dis Intell Q

Rep 2011;35:294–8.

[11] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Population by Age and Sex, Regions of

Australia,2013.In: Australian Bureauof Statistics.Canberra:Australian Bureau

of Statistics;2014.

[12] National Centre for Immunisations Researchand Surveillance(NCIRS). Child-

hood Immunisation Coverageestimates.NCIRS,2013.

[13] Brotherton JM, Deeks SL, Campbell-Lloyd S, Misrachi A, Passaris I, Peterson

K, et al. Interim estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coveragein

the school-based program in Australia. Communicable DiseasesIntelligence

2008;32:457–61.

[14] Erlewyn-LajeunesseM, Hunt LP, Heath PT, Finn A. Anaphylaxis as an adverse

eventfollowing immunisation in the UK and Ireland. Archiv DiseaseChildhood

2012;97:487–90.

[15] D’SouzaRM, Campbell-Lloyd S, Isaacs D, Gold M, BurgessM, Turnbull F, et al.

Adverse Events Following Immunisation associatedwith the 1998 Australian

Measles Control Campaign.In: Department of Health and Ageing AG, editor.

CommunicableDiseasesIntelligence2000,pp. 27–33.

[16] Nakayama T, Onoda K. Vaccine adverse events reported in post-marketing

study of the Kitasato Institute from 1994 to 2004.Vaccine 2007;25:570–6.

[17] Tseng HF, Sy LS, Liu IL, Qian L, Marcy SM, Weintraub E, et al. Postlicensure

surveillancefor pre-specifiedadverseeventsfollowing the 13-valent pneumo-

coccal conjugatevaccinein children. Vaccine 2013;31:2578–83.

[18] Brotherton JM, Gold MS, Kemp AS, McIntyre PB, BurgessMA, Campbell-LloydS,

et al. Anaphylaxis following quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination.

CMAJ: Can Med Assoc J 2008;179:525–33.

[19] Halsey NA, Edwards KM, Dekker CL, Klein NP, Baxter R, Larussa P, et al.

Algorithm to assesscausalityafter individual adverseeventsfollowing immun-

izations. Vaccine 2012;30:5791–8.

[20] Tozzi AE, Asturias EJ, BalakrishnanMR, HalseyNA, Law B, ZuberPL. Assessment

of causalityof individual adverseeventsfollowing immunization (AEFI): a WHO

tool for global use. Vaccine 2013;31:5041–6.

[21] Liew WK, Crawford N, Tang ML, Buttery J, Royle J, Gold M, et al. Hypersen-

sitivity reactions to human papillomavirus vaccine in Australian schoolgirls:

retrospectivecohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a2642.

[22] Khodoun MV, Mercatili P, Orekov T, Finkelman FD. Basophilsand macrophages

both contribute to IgG-mediatedanaphylaxis.J Immunol 2009;182:36.7.

[23] Clothier HJ, Lee KJ, SundararajanV, Buttery JP, Crawford NW. Human papillo-

mavirus vaccine in boys: backgroundrates of potential adverseevents.Med J

Aust 2013;198:554–8.

[24] Osborne NJ, Koplin JJ, Martin PE, Gurrin LC, Lowe AJ, Matheson MC, et al.

Prevalenceof challenge-provenIgE-mediated food allergy using population-

basedsampling and predeterminedchallengecriteria in infants. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 2011;127:668–76.

[25] Terhune TD, Deth RC. How aluminum adjuvants could promote and enhance

non-targetIgE synthesisin a genetically-vulnerablesub-population.J Immuno-

toxicol 2013;10:210–22.

[26] Gruber C, Warner J, Hill D, BauchauV, Group ES. Early atopic diseaseand early

childhood immunization – is there a link. Allergy 2008;63:1464–72.

[27] BonhoefferJ, Heininger U. Adverseeventsfollowing immunization: perception

and evidence.Curr Opin Infect Dis 2007;20:237–46.

[28] Crawford NW, Buttery JP. Adverse events following immunizations: fact and

fiction. Paediatr Child Health 2013;23:121–4.

[29] Erlewyn-Lajeunesse M, Dymond S, Slade I, Mansfield HL, Fish R, Jones O,

et al. Diagnostic utility of two case definitions for anaphylaxis. Drug Safety

2010;33:57–64.

Acknowledgements

Neal Halsey, Mandira Hiremath, Alissa McMinn for assistance

and advice in the study. We also thank the staff at ACIR and the

National HPV Vaccination Program Register for assistancein data

provision for the study.

Conflict of interest:The authors wish to confirm that there are

no known conflicts of interest associatedwith this publication and

there has been no significant financial support for this work that

could have influenced its outcome.

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved

by all named authors and that there are no other persons who

satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further

confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been

approved by all of us. DC was the coordinating author, responsible

for design of the study, data collection and data analysis as well

as writing and finalizing the manuscript for submission. NC was

responsible for conceptualization of the study, data analysis and

writing/editing/finalizing the manuscript. KP, SC, MD and JB were

responsible for writing/editing the manuscript.

All authors confirm that they have given due consideration to

the protection of intellectual property associated with this work

and that there are no impediments to publication, including the

timing of publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so

doing we confirm that we have followed the regulations of our

institutions concerning intellectual property.

References

[1] National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). The Australian

Immunisation Handbook. 10th ed. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia;

2013.

[2] Department of Health, State Government of Victoria, Australia. Immun-

isation Schedule Victoria. 2014. Available at: http://www.health.vic.gov.au/

immunisation/factsheets/schedule-victoria.htm,accessed1 August 2014.

[3] Clothier HJ, Crawford NW, Kempe A, Buttery JP. Surveillanceof adverseevents

following immunisation: the model of SAEFVIC,Victoria. Commun Dis Intell Q

Rep 2011;35:294–8.

[4] RuggebergJU, Gold MS, Bayas JM, Blum MD, Bonhoeffer J, Friedlander S, et al.

Anaphylaxis: case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and

presentationof immunization safetydata.Vaccine 2007;25:5675–84.

[5] Bohlke K, Davis RL, Marcy SM, Braun MM, DeStefano F, Black SB, et al.

Risk of anaphylaxis after vaccination of children and adolescents.Pediatrics

2003;112:815–20.

[6] Patja A, Davidkin I, Kurki T, Kallio MJ, Valle M, Peltola H. Seriousadverseevents

after measles–mumps–rubellavaccinationduring a fourteen-yearprospective

follow-up. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19:1127–34.

[7] Caubet JC, Siegrist CA, Eigenmann PA. Allergic reactions and vaccines: distin-

guishing true and false reactions.Rev Med Suisse2009;5:416–9.

[8] Gold M. A clinical approach to investigationof suspectedvaccineanaphylaxis.

Curr Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;25:68–70.

[9] Gold MS, Gidudu J, Erlewyn-LajeunesseM, Law B. Brighton CollaborationWork-

ing Group on A. Can the Brighton Collaboration case definitions be used to

improve the quality of AdverseEventFollowing Immunization (AEFI) reporting.

Anaphylaxis as a casestudy. Vaccine 2010;28:4487–98.

[10] Clothier HJ, Crawford NW, Kempe A, Buttery JP. Surveillanceof adverseevents

following immunisation: The model of SAEFVIC Victoria. Commun Dis Intell Q

Rep 2011;35:294–8.

[11] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Population by Age and Sex, Regions of

Australia,2013.In: Australian Bureauof Statistics.Canberra:Australian Bureau

of Statistics;2014.

[12] National Centre for Immunisations Researchand Surveillance(NCIRS). Child-

hood Immunisation Coverageestimates.NCIRS,2013.

[13] Brotherton JM, Deeks SL, Campbell-Lloyd S, Misrachi A, Passaris I, Peterson

K, et al. Interim estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coveragein

the school-based program in Australia. Communicable DiseasesIntelligence

2008;32:457–61.

[14] Erlewyn-LajeunesseM, Hunt LP, Heath PT, Finn A. Anaphylaxis as an adverse

eventfollowing immunisation in the UK and Ireland. Archiv DiseaseChildhood

2012;97:487–90.

[15] D’SouzaRM, Campbell-Lloyd S, Isaacs D, Gold M, BurgessM, Turnbull F, et al.

Adverse Events Following Immunisation associatedwith the 1998 Australian

Measles Control Campaign.In: Department of Health and Ageing AG, editor.

CommunicableDiseasesIntelligence2000,pp. 27–33.

[16] Nakayama T, Onoda K. Vaccine adverse events reported in post-marketing

study of the Kitasato Institute from 1994 to 2004.Vaccine 2007;25:570–6.

[17] Tseng HF, Sy LS, Liu IL, Qian L, Marcy SM, Weintraub E, et al. Postlicensure

surveillancefor pre-specifiedadverseeventsfollowing the 13-valent pneumo-

coccal conjugatevaccinein children. Vaccine 2013;31:2578–83.

[18] Brotherton JM, Gold MS, Kemp AS, McIntyre PB, BurgessMA, Campbell-LloydS,

et al. Anaphylaxis following quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination.

CMAJ: Can Med Assoc J 2008;179:525–33.

[19] Halsey NA, Edwards KM, Dekker CL, Klein NP, Baxter R, Larussa P, et al.

Algorithm to assesscausalityafter individual adverseeventsfollowing immun-

izations. Vaccine 2012;30:5791–8.

[20] Tozzi AE, Asturias EJ, BalakrishnanMR, HalseyNA, Law B, ZuberPL. Assessment

of causalityof individual adverseeventsfollowing immunization (AEFI): a WHO

tool for global use. Vaccine 2013;31:5041–6.

[21] Liew WK, Crawford N, Tang ML, Buttery J, Royle J, Gold M, et al. Hypersen-

sitivity reactions to human papillomavirus vaccine in Australian schoolgirls:

retrospectivecohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a2642.

[22] Khodoun MV, Mercatili P, Orekov T, Finkelman FD. Basophilsand macrophages

both contribute to IgG-mediatedanaphylaxis.J Immunol 2009;182:36.7.

[23] Clothier HJ, Lee KJ, SundararajanV, Buttery JP, Crawford NW. Human papillo-

mavirus vaccine in boys: backgroundrates of potential adverseevents.Med J

Aust 2013;198:554–8.

[24] Osborne NJ, Koplin JJ, Martin PE, Gurrin LC, Lowe AJ, Matheson MC, et al.

Prevalenceof challenge-provenIgE-mediated food allergy using population-

basedsampling and predeterminedchallengecriteria in infants. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 2011;127:668–76.

[25] Terhune TD, Deth RC. How aluminum adjuvants could promote and enhance

non-targetIgE synthesisin a genetically-vulnerablesub-population.J Immuno-

toxicol 2013;10:210–22.

[26] Gruber C, Warner J, Hill D, BauchauV, Group ES. Early atopic diseaseand early

childhood immunization – is there a link. Allergy 2008;63:1464–72.

[27] BonhoefferJ, Heininger U. Adverseeventsfollowing immunization: perception

and evidence.Curr Opin Infect Dis 2007;20:237–46.

[28] Crawford NW, Buttery JP. Adverse events following immunizations: fact and

fiction. Paediatr Child Health 2013;23:121–4.

[29] Erlewyn-Lajeunesse M, Dymond S, Slade I, Mansfield HL, Fish R, Jones O,

et al. Diagnostic utility of two case definitions for anaphylaxis. Drug Safety

2010;33:57–64.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 6

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.