Systematic Review: Mental Toughness and Sports Performance, May 2020

VerifiedAdded on 2020/11/09

|44

|17330

|153

Report

AI Summary

This systematic review examines the critical role of mental toughness in professional sports performance. Conducted at University College Birmingham, the review analyzed articles from January 2004 to November 2019, focusing on the psychological elements of mental toughness, its importance for athletes, and its impact on performance across different competition levels. The study reviewed 18 articles, revealing that mentally tough athletes often exhibit problem-solving focus, high motivation, self-belief, and better coping mechanisms, which positively influence performance. However, some studies suggest that excessive mental toughness may lead to overtraining and increased injury risk. The review also explores the relationship between mental toughness and variables like practice hours and mental health, concluding that there is a strong positive association between mental toughness and sports performance, although many other factors can influence this relationship.

A systematic review of the role of mental toughness for execution

successful performance in professional sport athletes

BA Hons Sport and Fitness

University College Birmingham

Validated by: The University of Birmingham

May 2020

1

successful performance in professional sport athletes

BA Hons Sport and Fitness

University College Birmingham

Validated by: The University of Birmingham

May 2020

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Aim: To examine the role of mental toughness levels for the execution of successful sports

performance. More specifically, the current study seeks to examine psychological elements

necessary for an athlete to be mentally tough, the importance of developing and maintaining

mental toughness levels regarding sports performance, differences in mental toughness levels

between the level of competition and effects of mental toughness levels on sports performance

and outcome.

Methods: Electronic databases were searched to find trials conducted from January 2004 to

November 2019. Articles were assessed independently according to the following inclusion

criteria: (1) population: professional, semi-pro or amateur athletes, (2) intervention: mental

toughness levels assessing, competition levels assessing, psychological elements necessary for

an athlete to be mentally tough assessing, and sports performance assessing, (3) outcomes:

changes in athlete’s mental toughness levels, sports performance, or sports outcome.

Results: From the 228 articles initially identified, 18 met the criteria for detailed review.

There were randomised, and nonrandomised questioners, interviews, surveys, measures or

observations study designs. Twelve studies have shown that athletes with high levels of

mental toughness are more problem solving focused, less emotional focused, highly

motivated, have high levels of self believe, cope better with failure, recover quicker after error

and in team sports communicate more in comparison with athletes with lower levels of mental

toughness, which for the result have a positive effect on their sports performance. Two studies

have shown that higher levels of mental toughness are positively associated with higher hours

of sport-specific practice with no difference between gender and age of specialisation in a

specific sport. One study has shown that athletes with high levels of mental toughness have

significantly fewer mental health issues, such as depression and burnout. Whereas, two

studies found that athlete's sports performance and affect intensity are unrelated to mental

toughness levels.

Conclusion: Results suggest that there is a strong positive association between mental

toughness and sports performance. However, there are a lot of different variables that can

determine levels of an athlete's mental toughness and be positively or negatively associated

with mental toughness levels, which have a direct impact on sports performance.

2

performance. More specifically, the current study seeks to examine psychological elements

necessary for an athlete to be mentally tough, the importance of developing and maintaining

mental toughness levels regarding sports performance, differences in mental toughness levels

between the level of competition and effects of mental toughness levels on sports performance

and outcome.

Methods: Electronic databases were searched to find trials conducted from January 2004 to

November 2019. Articles were assessed independently according to the following inclusion

criteria: (1) population: professional, semi-pro or amateur athletes, (2) intervention: mental

toughness levels assessing, competition levels assessing, psychological elements necessary for

an athlete to be mentally tough assessing, and sports performance assessing, (3) outcomes:

changes in athlete’s mental toughness levels, sports performance, or sports outcome.

Results: From the 228 articles initially identified, 18 met the criteria for detailed review.

There were randomised, and nonrandomised questioners, interviews, surveys, measures or

observations study designs. Twelve studies have shown that athletes with high levels of

mental toughness are more problem solving focused, less emotional focused, highly

motivated, have high levels of self believe, cope better with failure, recover quicker after error

and in team sports communicate more in comparison with athletes with lower levels of mental

toughness, which for the result have a positive effect on their sports performance. Two studies

have shown that higher levels of mental toughness are positively associated with higher hours

of sport-specific practice with no difference between gender and age of specialisation in a

specific sport. One study has shown that athletes with high levels of mental toughness have

significantly fewer mental health issues, such as depression and burnout. Whereas, two

studies found that athlete's sports performance and affect intensity are unrelated to mental

toughness levels.

Conclusion: Results suggest that there is a strong positive association between mental

toughness and sports performance. However, there are a lot of different variables that can

determine levels of an athlete's mental toughness and be positively or negatively associated

with mental toughness levels, which have a direct impact on sports performance.

2

1.0 Introduction...........................................................................................................................4

1.1 Known about topic............................................................................................................4

1.2 Aim and objectives...........................................................................................................5

2.0 Literature review...................................................................................................................5

3.0 Methods.................................................................................................................................7

3.1 Eligibility criteria..............................................................................................................7

3.2 Information sources and search........................................................................................7

3.3 Study selection and Data collection process.....................................................................8

3.4 Risk of bias assessment method........................................................................................8

3.5 Samples.............................................................................................................................9

4.0 Results...................................................................................................................................9

4.1 Database results................................................................................................................9

4.2 Data Collection Procedure..............................................................................................16

4.3 Performance....................................................................................................................18

5.0 Discussion...........................................................................................................................19

5.1 Psychological elements necessary for an athlete to be mentally tough..........................19

5.2 Importance of developing and maintaining mental toughness levels regarding sports

performance..........................................................................................................................21

5.3 Differences in mental toughness levels between the level of competition.....................25

5.4 Effects of mental toughness levels on sports performance and outcome.......................26

6.0 Summary.............................................................................................................................32

7.0 Reference List.....................................................................................................................34

8.0 Appendix.............................................................................................................................40

3

1.1 Known about topic............................................................................................................4

1.2 Aim and objectives...........................................................................................................5

2.0 Literature review...................................................................................................................5

3.0 Methods.................................................................................................................................7

3.1 Eligibility criteria..............................................................................................................7

3.2 Information sources and search........................................................................................7

3.3 Study selection and Data collection process.....................................................................8

3.4 Risk of bias assessment method........................................................................................8

3.5 Samples.............................................................................................................................9

4.0 Results...................................................................................................................................9

4.1 Database results................................................................................................................9

4.2 Data Collection Procedure..............................................................................................16

4.3 Performance....................................................................................................................18

5.0 Discussion...........................................................................................................................19

5.1 Psychological elements necessary for an athlete to be mentally tough..........................19

5.2 Importance of developing and maintaining mental toughness levels regarding sports

performance..........................................................................................................................21

5.3 Differences in mental toughness levels between the level of competition.....................25

5.4 Effects of mental toughness levels on sports performance and outcome.......................26

6.0 Summary.............................................................................................................................32

7.0 Reference List.....................................................................................................................34

8.0 Appendix.............................................................................................................................40

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Known about the topic

The existing body of research on mental toughness suggests that mental toughness in sport is

defined as an intentional, effectual and flexible psychological factor for enhancing and

maintaining goal-oriented pursuits (Crust, 2011, Gucciardi et al., 2015 and Powell and Myers,

2017). In the same way, the existing research recognises the critical role in sports success,

outcome, goals progresses and dealing with stressful situations played by mental toughness,

which can have positive and negative effects (Gucciardi, Gordan and Dimmock, 2008, Crust,

2011, Gucciardi et al., 2015 and Powell and Myers, 2017). Therefore, research suggests that

mentally tough athletes are those athletes who have high levels of cognitive and behavioural

effort such as; determination, focus and self-believe and who can maintain those levels over

the specific amount of time (Gucciardi, Gordan and Dimmock, 2008, Sheard, 2010 and Jones

and Parker, 2017,).

However, on the other hand, it has been demonstrated that mentally tough athletes have a

higher risk of injury during practice or in a competition by pushing their bodies over the limit

which can have a direct impact on their sports performance (Andersen, 2011, Su and Reeve,

2011, Bell et al., 2013 and Gucciardi, 2017). More specifically, athletes with high levels of

mental toughness are in a greater risk of jeopardising their injury recovery process by

ignoring possible pain, not following recommended rehabilitation process, attempting to

pursue their goals and coming back to practice and the competition before injury fully heals

which for result can have poor sports performance and possible new injuries (Andersen, 2011,

Su and Reeve, 2011, Bell et al., 2013 and Gucciardi, 2017).

Although extensive researches have been carried out on mental toughness and its relation to

sports performance, one major drawback is that all studies used questionnaires, interviews or

some similar sort of self-reported measures approach (Wright, 2017). Perhaps the most

serious disadvantages of this method are facts that samples may lie due to social desirability

or that samples can give no-valid answers due to differences in understanding and

interpretation (Wright, 2017). Additionally, there is no way that researchers can tell how

truthful and thoughtful sample have had been in responding (Wright, 2017). However,

although self-report measures approach is perhaps the most serious disadvantage of existing

literature made on mental toughness and its relationship with sports performance, in the same

way, there are no other methods available to assess mental toughness levels (Gucciardi,

4

1.1 Known about the topic

The existing body of research on mental toughness suggests that mental toughness in sport is

defined as an intentional, effectual and flexible psychological factor for enhancing and

maintaining goal-oriented pursuits (Crust, 2011, Gucciardi et al., 2015 and Powell and Myers,

2017). In the same way, the existing research recognises the critical role in sports success,

outcome, goals progresses and dealing with stressful situations played by mental toughness,

which can have positive and negative effects (Gucciardi, Gordan and Dimmock, 2008, Crust,

2011, Gucciardi et al., 2015 and Powell and Myers, 2017). Therefore, research suggests that

mentally tough athletes are those athletes who have high levels of cognitive and behavioural

effort such as; determination, focus and self-believe and who can maintain those levels over

the specific amount of time (Gucciardi, Gordan and Dimmock, 2008, Sheard, 2010 and Jones

and Parker, 2017,).

However, on the other hand, it has been demonstrated that mentally tough athletes have a

higher risk of injury during practice or in a competition by pushing their bodies over the limit

which can have a direct impact on their sports performance (Andersen, 2011, Su and Reeve,

2011, Bell et al., 2013 and Gucciardi, 2017). More specifically, athletes with high levels of

mental toughness are in a greater risk of jeopardising their injury recovery process by

ignoring possible pain, not following recommended rehabilitation process, attempting to

pursue their goals and coming back to practice and the competition before injury fully heals

which for result can have poor sports performance and possible new injuries (Andersen, 2011,

Su and Reeve, 2011, Bell et al., 2013 and Gucciardi, 2017).

Although extensive researches have been carried out on mental toughness and its relation to

sports performance, one major drawback is that all studies used questionnaires, interviews or

some similar sort of self-reported measures approach (Wright, 2017). Perhaps the most

serious disadvantages of this method are facts that samples may lie due to social desirability

or that samples can give no-valid answers due to differences in understanding and

interpretation (Wright, 2017). Additionally, there is no way that researchers can tell how

truthful and thoughtful sample have had been in responding (Wright, 2017). However,

although self-report measures approach is perhaps the most serious disadvantage of existing

literature made on mental toughness and its relationship with sports performance, in the same

way, there are no other methods available to assess mental toughness levels (Gucciardi,

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Hanton and Mallett, 2012). Therefore, self-report measures approaches are the most logical

assessment tolls (Gucciardi, Hanton and Mallett, 2012).

1.2 Aim and objectives

This systematic review aims to explore the relationship between mental toughness and sports

performance in professional athletes.

The specific objective of this systematic review was:

-To explore which psychological elements are necessary for an athlete to be mentally tough.

- To explore the importance of developing and maintaining mental toughness levels regarding

sports performance.

-To explore differences in mental toughness levels between the level of competition.

-To explore the effects of mental toughness levels on sports performance and outcome.

2.0 Literature review

It is now well established from a variety of studies that mental toughness is one of the crucial

psychological factors for success in elite sport (Golby and Sherad, 2004, Bull et al., 2005,

Jones, Hanton and Connaughton, 2007, Gucciardi, Gordan and Dimmock, 2008, Nicholls et

al., 2008, Crust and Azadi, 2010, Chen and Cheesman, 2013, Gucciardi, 2017 and Meggs and

Chen, 2018).

Several studies have examined the effects of higher and lower levels of mental toughness,

their positive and negative effects on sports performance (Connaughton et al., 2008, Chen and

Cheesman, 2013, Diment, 2014, Mahoney et al., 2014 and Jones and Parker, 2019). Results

suggest that higher levels of mental toughness will separate elite athletes and successful

performance versus athletes with lower levels of mental toughness performance

(Connaughton et al., 2008, Chen and Cheesman, 2013, Diment, 2014 and Mahoney et al.,

2014) whereby the study by Jones and Parker (2019) suggests that mental toughness levels

and sports performance are unrelated.

Similarly to the studies by Connaughton et al. (2008), Chen and Cheesman (2013), Diment

(2014), Mahoney et al. (2014) and Jones and Parker (2019), the study by Slimani et al. (2015)

examined the relationship between mental toughness and power test performances and shown

that mental toughness has a direct impact on power performance.

5

assessment tolls (Gucciardi, Hanton and Mallett, 2012).

1.2 Aim and objectives

This systematic review aims to explore the relationship between mental toughness and sports

performance in professional athletes.

The specific objective of this systematic review was:

-To explore which psychological elements are necessary for an athlete to be mentally tough.

- To explore the importance of developing and maintaining mental toughness levels regarding

sports performance.

-To explore differences in mental toughness levels between the level of competition.

-To explore the effects of mental toughness levels on sports performance and outcome.

2.0 Literature review

It is now well established from a variety of studies that mental toughness is one of the crucial

psychological factors for success in elite sport (Golby and Sherad, 2004, Bull et al., 2005,

Jones, Hanton and Connaughton, 2007, Gucciardi, Gordan and Dimmock, 2008, Nicholls et

al., 2008, Crust and Azadi, 2010, Chen and Cheesman, 2013, Gucciardi, 2017 and Meggs and

Chen, 2018).

Several studies have examined the effects of higher and lower levels of mental toughness,

their positive and negative effects on sports performance (Connaughton et al., 2008, Chen and

Cheesman, 2013, Diment, 2014, Mahoney et al., 2014 and Jones and Parker, 2019). Results

suggest that higher levels of mental toughness will separate elite athletes and successful

performance versus athletes with lower levels of mental toughness performance

(Connaughton et al., 2008, Chen and Cheesman, 2013, Diment, 2014 and Mahoney et al.,

2014) whereby the study by Jones and Parker (2019) suggests that mental toughness levels

and sports performance are unrelated.

Similarly to the studies by Connaughton et al. (2008), Chen and Cheesman (2013), Diment

(2014), Mahoney et al. (2014) and Jones and Parker (2019), the study by Slimani et al. (2015)

examined the relationship between mental toughness and power test performances and shown

that mental toughness has a direct impact on power performance.

5

On the other hand, the study by Raudsepp and Vink (2018) tested the relationship between

sport-specific exercises and mental toughness and shown higher mental toughness levels

when more hours were invested in sport-specific exercises.

In contrast to the study by Raudsepp and Vink (2018), which has been explored a

physiological relationship with mental toughness, the studies by Cowden et al. (2018) and

Vaughan et al. (2018) researched psychological resources necessary for achieving peak

performance in sport and their relationship with mental toughness. Data suggests that personal

standards and self-determination are positively related to mental toughness. However, on the

other hand, concerns over mistakes and non-self-determination are negatively related to

mental toughness.

Similarly, several studies have postulated a convergence between mental toughness and

psychological performance strategies such as self-talk, emotional control, and relaxation

strategies (Golby and Sherad, 2004, Bull et al., 2005, Jones, Hanton and Connaughton, 2007,

Nicholls et al., 2008 and Crust and Azadi, 2010). The studies by Golby and Sherad (2004),

Bull et al. (2005), Jones, Hanton and Connaughton (2007), Nicholls et al. (2008) and Crust

and Azadi (2010) reported that psychological performance strategies are positively related

with mental toughness. Results suggest that athletes with high levels of mental toughness are

more consistent in remaining focused and determined. More specifically, mentally tough

athletes cope better with the demands of the sport such as training, competition, outcome, and

lifestyle, which allows them to have better sports performance.

In the same way, the study by Meggs and Chen (2018) investigated the relationship between

sport's performance failure and Mental toughness. The study had a sampling of 80 high-level

swimmers who experienced sports outcome failure in the previous four weeks. Evidence

suggests that athletes with high levels of mental toughness are more likely to explain sport's

performance failure as being a result of controllable factors.

The study by Buhrow et al. (2017) offers probably the most comprehensive empirical analysis

of the relationship between mental toughness, early age sport specialisation, and gender. Data

suggests that there is no significant difference in those who specialise early in comparison to

those who did not. Similarly, there was no significant difference in mental toughness levels

between males and females.

6

sport-specific exercises and mental toughness and shown higher mental toughness levels

when more hours were invested in sport-specific exercises.

In contrast to the study by Raudsepp and Vink (2018), which has been explored a

physiological relationship with mental toughness, the studies by Cowden et al. (2018) and

Vaughan et al. (2018) researched psychological resources necessary for achieving peak

performance in sport and their relationship with mental toughness. Data suggests that personal

standards and self-determination are positively related to mental toughness. However, on the

other hand, concerns over mistakes and non-self-determination are negatively related to

mental toughness.

Similarly, several studies have postulated a convergence between mental toughness and

psychological performance strategies such as self-talk, emotional control, and relaxation

strategies (Golby and Sherad, 2004, Bull et al., 2005, Jones, Hanton and Connaughton, 2007,

Nicholls et al., 2008 and Crust and Azadi, 2010). The studies by Golby and Sherad (2004),

Bull et al. (2005), Jones, Hanton and Connaughton (2007), Nicholls et al. (2008) and Crust

and Azadi (2010) reported that psychological performance strategies are positively related

with mental toughness. Results suggest that athletes with high levels of mental toughness are

more consistent in remaining focused and determined. More specifically, mentally tough

athletes cope better with the demands of the sport such as training, competition, outcome, and

lifestyle, which allows them to have better sports performance.

In the same way, the study by Meggs and Chen (2018) investigated the relationship between

sport's performance failure and Mental toughness. The study had a sampling of 80 high-level

swimmers who experienced sports outcome failure in the previous four weeks. Evidence

suggests that athletes with high levels of mental toughness are more likely to explain sport's

performance failure as being a result of controllable factors.

The study by Buhrow et al. (2017) offers probably the most comprehensive empirical analysis

of the relationship between mental toughness, early age sport specialisation, and gender. Data

suggests that there is no significant difference in those who specialise early in comparison to

those who did not. Similarly, there was no significant difference in mental toughness levels

between males and females.

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

On the other hand, the study by Gerber et al. (2018) examines the importance of mental

toughness in young elite athlete's careers when they are exposed to high-stress levels.

Researchers attempted to evaluate the possible interaction of mental toughness on the burnout

and depressive symptoms in young elite athletes. The results of this study indicate that

athletes with higher levels of mental toughness reported significantly fewer health issues

when they were exposed to highs stress levels, in comparison to those with lower mental

toughness levels.

In contrast, the study by Crust (2009) reported that there is no relationship between mental

toughness and the ability of athletes to control emotions under stressful situations. This is an

important finding because it shows that athletes with high levels of mental toughness do not

perform better because they are able to control emotions under stressful situations in

competition, compared to athletes with lower levels of mental toughness.

3.0 Methods

3.1 Eligibility criteria

In November 2019, studies investigating the relationship between mental toughness and

sports performance were searched. More specifically, the focus was on the relationship

between mental toughness and sports performance and outcome in amateur, semi-pro, and

professional athletes with no restriction on gender, age, or sport. A comprehensive systematic

literature search was restricted on only journals with date cut from January 2004 to November

2019, written in English.

3.2 Information sources and search

Four different search engines databases were used to find the appropriate journals: U Search

(Electronic Library of University College Birmingham) Pub Med, Sport Discus, and Google

Scholar. In order to proceed to a strategic search, the advanced search strategies have been

used. The following terms were used: 'mental toughness in sport'. U Search (Electronic

Library of University College Birmingham) found 7797 results. In order to find reliable

sources of information, research was narrowed only on academic journals. U Search found

3925 academic journals. To reduce the number of articles and to get into a more specific

search, the logical Boolean operator 'AND' and 'NOT' have been used. New terms have been

added to the search: ‘AND sports performance, ‘AND enhance,' 'AND elite sport,' 'AND

professional athletes,' 'NOT higher education,' 'NOT students'. Electronic Library of

7

toughness in young elite athlete's careers when they are exposed to high-stress levels.

Researchers attempted to evaluate the possible interaction of mental toughness on the burnout

and depressive symptoms in young elite athletes. The results of this study indicate that

athletes with higher levels of mental toughness reported significantly fewer health issues

when they were exposed to highs stress levels, in comparison to those with lower mental

toughness levels.

In contrast, the study by Crust (2009) reported that there is no relationship between mental

toughness and the ability of athletes to control emotions under stressful situations. This is an

important finding because it shows that athletes with high levels of mental toughness do not

perform better because they are able to control emotions under stressful situations in

competition, compared to athletes with lower levels of mental toughness.

3.0 Methods

3.1 Eligibility criteria

In November 2019, studies investigating the relationship between mental toughness and

sports performance were searched. More specifically, the focus was on the relationship

between mental toughness and sports performance and outcome in amateur, semi-pro, and

professional athletes with no restriction on gender, age, or sport. A comprehensive systematic

literature search was restricted on only journals with date cut from January 2004 to November

2019, written in English.

3.2 Information sources and search

Four different search engines databases were used to find the appropriate journals: U Search

(Electronic Library of University College Birmingham) Pub Med, Sport Discus, and Google

Scholar. In order to proceed to a strategic search, the advanced search strategies have been

used. The following terms were used: 'mental toughness in sport'. U Search (Electronic

Library of University College Birmingham) found 7797 results. In order to find reliable

sources of information, research was narrowed only on academic journals. U Search found

3925 academic journals. To reduce the number of articles and to get into a more specific

search, the logical Boolean operator 'AND' and 'NOT' have been used. New terms have been

added to the search: ‘AND sports performance, ‘AND enhance,' 'AND elite sport,' 'AND

professional athletes,' 'NOT higher education,' 'NOT students'. Electronic Library of

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

University College Birmingham found 228 academic journals whereby Sport Discus found

296 academic journals.

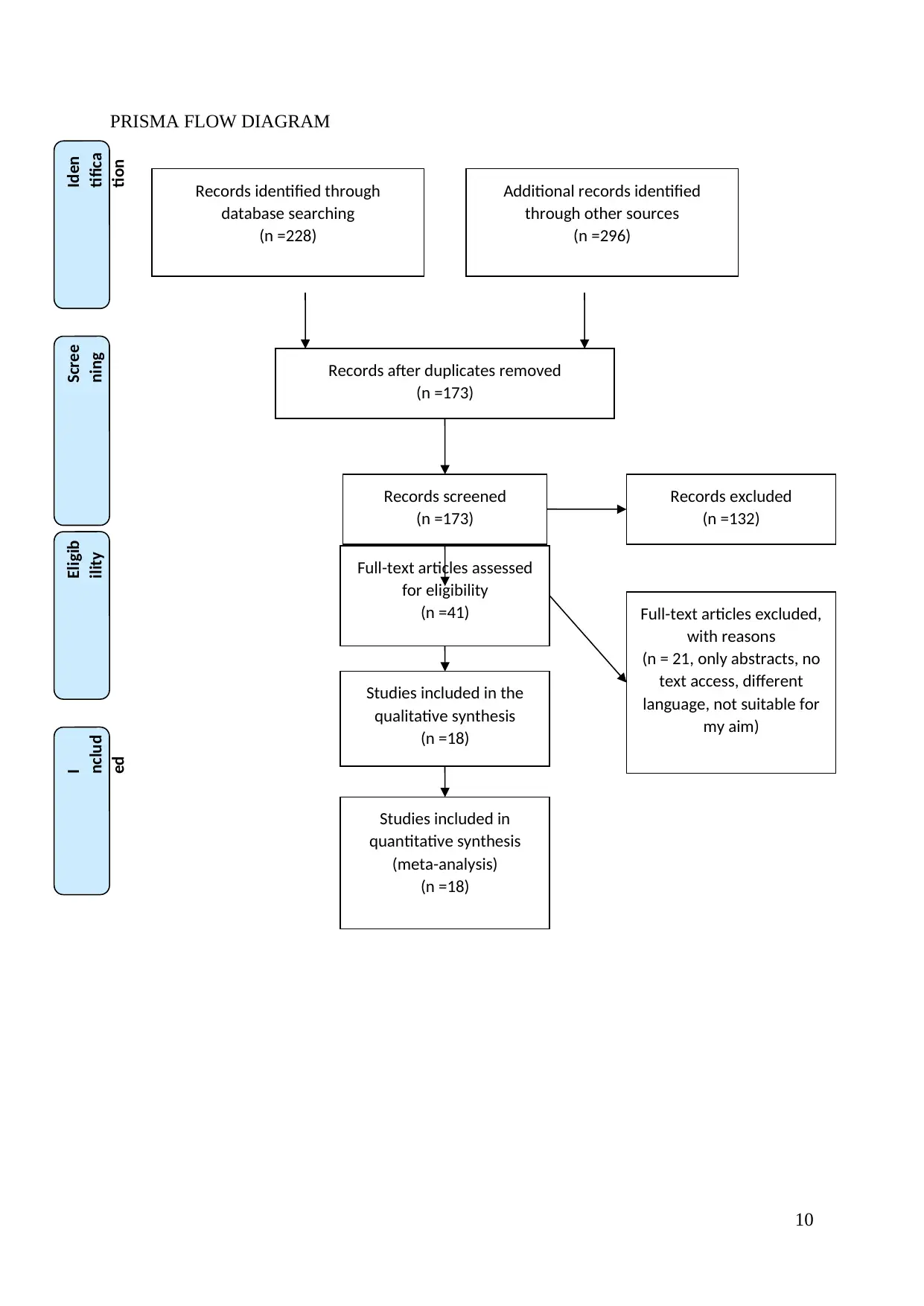

3.3 Study selection and Data collection process

Two hundred twenty-eight academic journals found by Electronic Library of University

College Birmingham search engine and 296 academic journals found by Sport Discus were

screened by title. After duplicates have had been removed, 173 academic journals were found.

Journals which in the title did not have keywords: 'mental toughness – sport’, ‘mental

toughness – enhance’, mental toughness – elite’, ‘mental toughness – athletes’, ‘mental

toughness – performance’, mental toughness – physical’ were excluded. In the same way,

journals, which in the title have: 'Coach's influence’, ‘coach's importance’, ‘coach's

development’ and ‘comparison of different measures approach’ were excluded which

altogether narrowed number of journals to 62. Additionally, academic journals with no access

to the full text, or journals which are not written in English were excluded, which narrowed

numbers of journals to 41. The rest of the journals were read fully or by abstract in order to

assess their suitability for the systematic review. Articles were considered suitable for the

study if researchers investigated: mental toughness in relation to sports performance or

outcome, participants were amateur, semi-pro or professional athletes, mental toughness and

sport-specific practice and their relationship with sports performance, positive and negative

effects of mental toughness on sports performance, burnout or depression symptoms in

relationship with sports performance and mental toughness. After the studies were screened

by reading the abstract or full text, 18 studies have had been found to be suitable for the

current study and PICO table was done. The search process is presented, trough the PRISMA

flow diagram in the result section 4.1 (Moher et al., 2009). PICO table is presented in Table 1,

result section.

3.4 Risk of bias assessment method

To identify which studies are suitable and reliable for the current study, a critical appraisal

tool (CASP) has been used (Young and Solomon, 2009, Hannes, Lockwood and Pearson,

2010, and Nadelson and Nadelson, 2014). Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to

identify the pros and cons of a research article in order to assess the reliability and usefulness

of study findings (Young and Solomon, 2009, Hannes, Lockwood and Pearson, 2010, and

Nadelson and Nadelson, 2014). To identify the most relevant high-quality studies, the 10-step

guide has been used (Young and Solomon, 2009, Hannes, Lockwood and Pearson, 2010, and

Nadelson and Nadelson, 2014). CASP is presented in Table 2, appendix section.

8

296 academic journals.

3.3 Study selection and Data collection process

Two hundred twenty-eight academic journals found by Electronic Library of University

College Birmingham search engine and 296 academic journals found by Sport Discus were

screened by title. After duplicates have had been removed, 173 academic journals were found.

Journals which in the title did not have keywords: 'mental toughness – sport’, ‘mental

toughness – enhance’, mental toughness – elite’, ‘mental toughness – athletes’, ‘mental

toughness – performance’, mental toughness – physical’ were excluded. In the same way,

journals, which in the title have: 'Coach's influence’, ‘coach's importance’, ‘coach's

development’ and ‘comparison of different measures approach’ were excluded which

altogether narrowed number of journals to 62. Additionally, academic journals with no access

to the full text, or journals which are not written in English were excluded, which narrowed

numbers of journals to 41. The rest of the journals were read fully or by abstract in order to

assess their suitability for the systematic review. Articles were considered suitable for the

study if researchers investigated: mental toughness in relation to sports performance or

outcome, participants were amateur, semi-pro or professional athletes, mental toughness and

sport-specific practice and their relationship with sports performance, positive and negative

effects of mental toughness on sports performance, burnout or depression symptoms in

relationship with sports performance and mental toughness. After the studies were screened

by reading the abstract or full text, 18 studies have had been found to be suitable for the

current study and PICO table was done. The search process is presented, trough the PRISMA

flow diagram in the result section 4.1 (Moher et al., 2009). PICO table is presented in Table 1,

result section.

3.4 Risk of bias assessment method

To identify which studies are suitable and reliable for the current study, a critical appraisal

tool (CASP) has been used (Young and Solomon, 2009, Hannes, Lockwood and Pearson,

2010, and Nadelson and Nadelson, 2014). Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to

identify the pros and cons of a research article in order to assess the reliability and usefulness

of study findings (Young and Solomon, 2009, Hannes, Lockwood and Pearson, 2010, and

Nadelson and Nadelson, 2014). To identify the most relevant high-quality studies, the 10-step

guide has been used (Young and Solomon, 2009, Hannes, Lockwood and Pearson, 2010, and

Nadelson and Nadelson, 2014). CASP is presented in Table 2, appendix section.

8

3.5 Samples

The sample size in studies was ranged from 12 to 58 years old male participants and 14 to 43

years old female participants. Three studies involved only males, and 15 studies involved both

genders. Participants were amateur, semi-pro, or professional athletes involved in the sport of

volleyball, tennis, running, swimming, football, kickboxing, cricket, and rugby. All together

in studies was involved 4420 participants, 2816 males, and 1604 females.

4.0 Results

4.1 Database results

The inclusion and exclusion of studies eligible for this study are presented trough the

PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009). More specifically, after keywords and logical

operators 'AND' and 'NOT' has been used Electronic Library of University College

Birmingham found 228 academic journals. The process of screening studies has been taken,

which narrowed eligible studies for the current systematic review on 18. The whole process is

presented in Prisma Flow diagram. PICO table is presented in Table 1.

9

The sample size in studies was ranged from 12 to 58 years old male participants and 14 to 43

years old female participants. Three studies involved only males, and 15 studies involved both

genders. Participants were amateur, semi-pro, or professional athletes involved in the sport of

volleyball, tennis, running, swimming, football, kickboxing, cricket, and rugby. All together

in studies was involved 4420 participants, 2816 males, and 1604 females.

4.0 Results

4.1 Database results

The inclusion and exclusion of studies eligible for this study are presented trough the

PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009). More specifically, after keywords and logical

operators 'AND' and 'NOT' has been used Electronic Library of University College

Birmingham found 228 academic journals. The process of screening studies has been taken,

which narrowed eligible studies for the current systematic review on 18. The whole process is

presented in Prisma Flow diagram. PICO table is presented in Table 1.

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

PRISMA FLOW DIAGRAM

10

Full-text articles excluded,

with reasons

(n = 21, only abstracts, no

text access, different

language, not suitable for

my aim)

Records identified through

database searching

(n =228)

Scree

ning

I

nclud

ed

Eligib

ility

Iden

tifica

tion

Additional records identified

through other sources

(n =296)

Records after duplicates removed

(n =173)

Records screened

(n =173)

Records excluded

(n =132)

Full-text articles assessed

for eligibility

(n =41)

Studies included in the

qualitative synthesis

(n =18)

Studies included in

quantitative synthesis

(meta-analysis)

(n =18)

10

Full-text articles excluded,

with reasons

(n = 21, only abstracts, no

text access, different

language, not suitable for

my aim)

Records identified through

database searching

(n =228)

Scree

ning

I

nclud

ed

Eligib

ility

Iden

tifica

tion

Additional records identified

through other sources

(n =296)

Records after duplicates removed

(n =173)

Records screened

(n =173)

Records excluded

(n =132)

Full-text articles assessed

for eligibility

(n =41)

Studies included in the

qualitative synthesis

(n =18)

Studies included in

quantitative synthesis

(meta-analysis)

(n =18)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

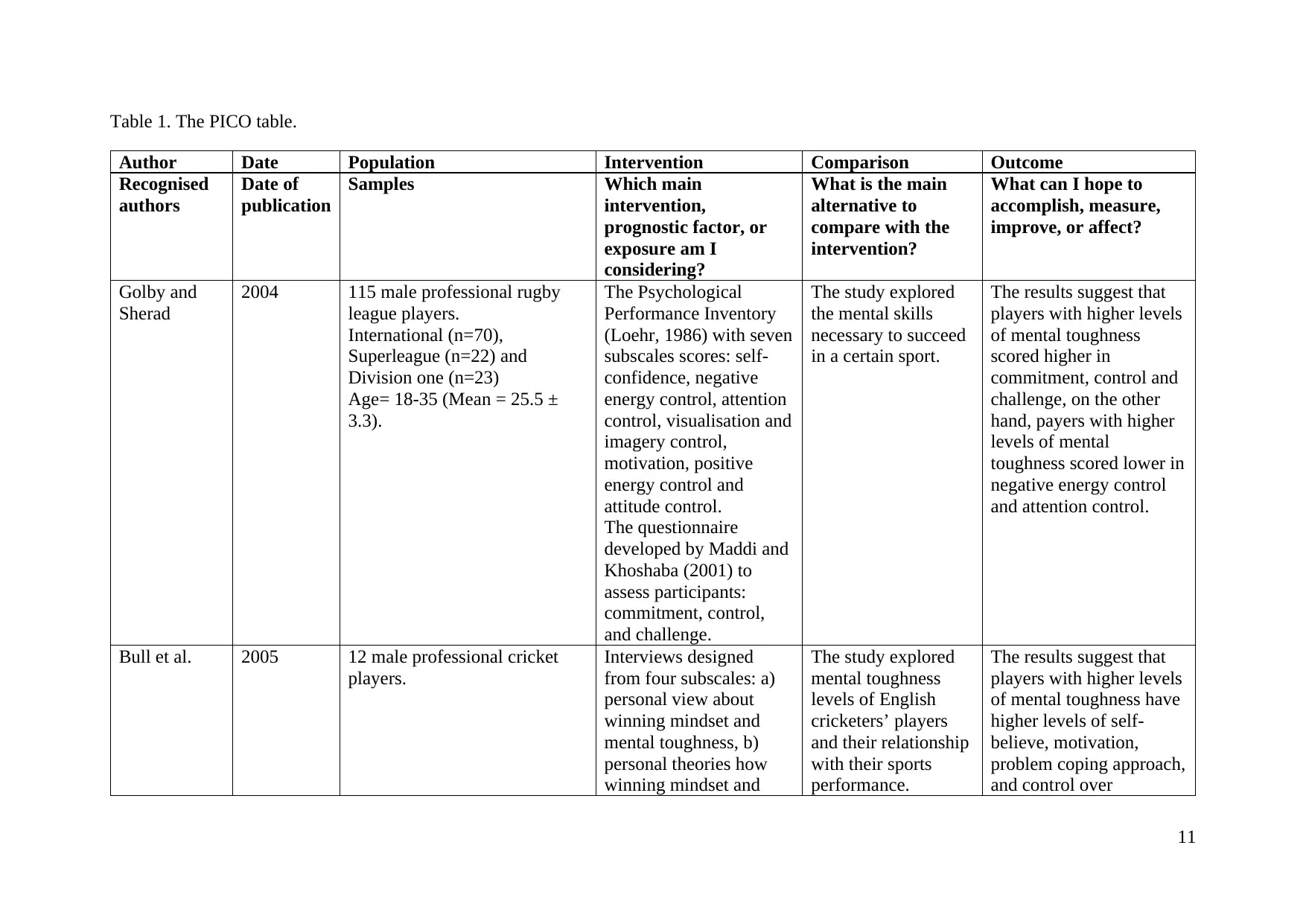

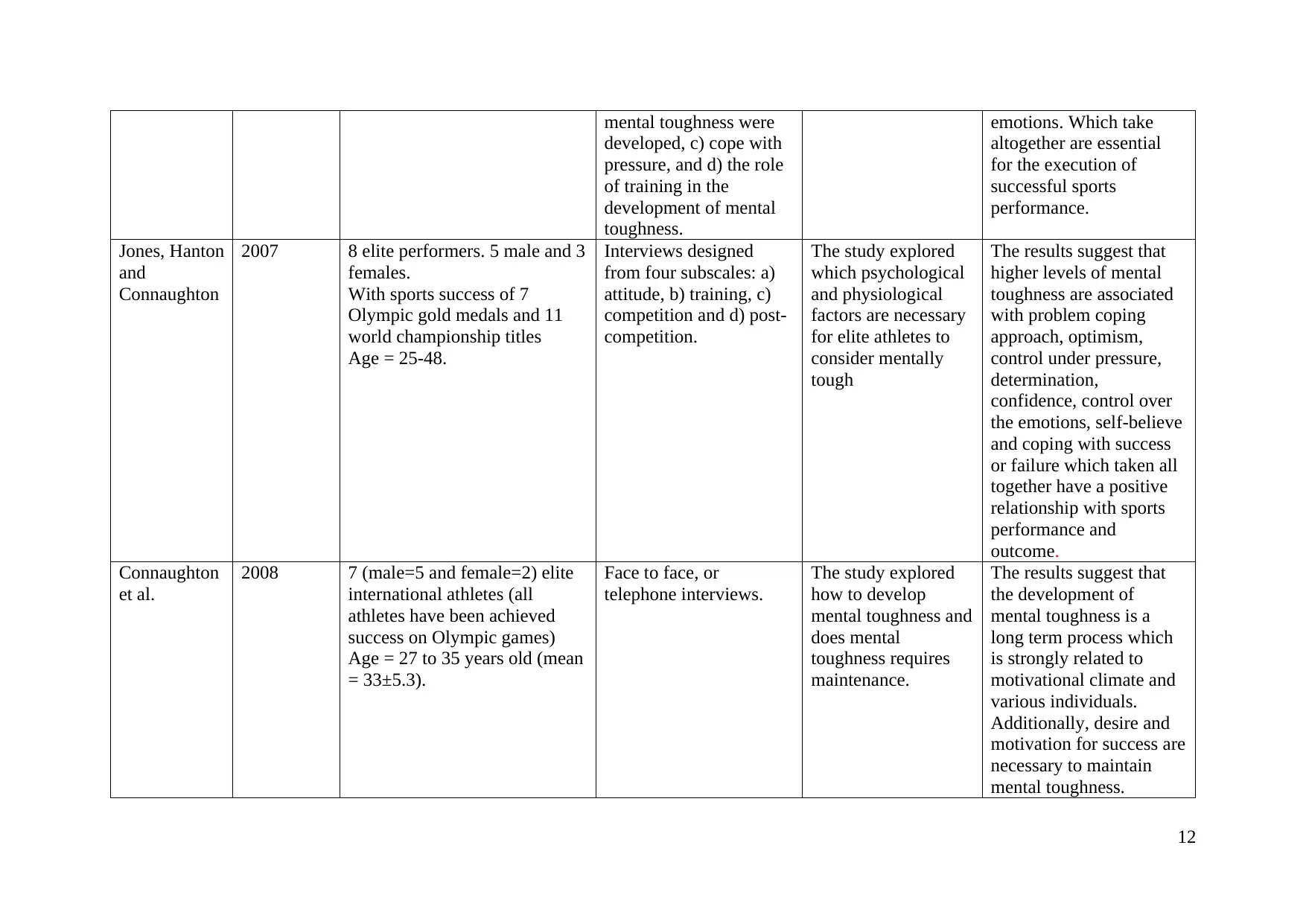

Table 1. The PICO table.

Author Date Population Intervention Comparison Outcome

Recognised

authors

Date of

publication

Samples Which main

intervention,

prognostic factor, or

exposure am I

considering?

What is the main

alternative to

compare with the

intervention?

What can I hope to

accomplish, measure,

improve, or affect?

Golby and

Sherad

2004 115 male professional rugby

league players.

International (n=70),

Superleague (n=22) and

Division one (n=23)

Age= 18-35 (Mean = 25.5 ±

3.3).

The Psychological

Performance Inventory

(Loehr, 1986) with seven

subscales scores: self-

confidence, negative

energy control, attention

control, visualisation and

imagery control,

motivation, positive

energy control and

attitude control.

The questionnaire

developed by Maddi and

Khoshaba (2001) to

assess participants:

commitment, control,

and challenge.

The study explored

the mental skills

necessary to succeed

in a certain sport.

The results suggest that

players with higher levels

of mental toughness

scored higher in

commitment, control and

challenge, on the other

hand, payers with higher

levels of mental

toughness scored lower in

negative energy control

and attention control.

Bull et al. 2005 12 male professional cricket

players.

Interviews designed

from four subscales: a)

personal view about

winning mindset and

mental toughness, b)

personal theories how

winning mindset and

The study explored

mental toughness

levels of English

cricketers’ players

and their relationship

with their sports

performance.

The results suggest that

players with higher levels

of mental toughness have

higher levels of self-

believe, motivation,

problem coping approach,

and control over

11

Author Date Population Intervention Comparison Outcome

Recognised

authors

Date of

publication

Samples Which main

intervention,

prognostic factor, or

exposure am I

considering?

What is the main

alternative to

compare with the

intervention?

What can I hope to

accomplish, measure,

improve, or affect?

Golby and

Sherad

2004 115 male professional rugby

league players.

International (n=70),

Superleague (n=22) and

Division one (n=23)

Age= 18-35 (Mean = 25.5 ±

3.3).

The Psychological

Performance Inventory

(Loehr, 1986) with seven

subscales scores: self-

confidence, negative

energy control, attention

control, visualisation and

imagery control,

motivation, positive

energy control and

attitude control.

The questionnaire

developed by Maddi and

Khoshaba (2001) to

assess participants:

commitment, control,

and challenge.

The study explored

the mental skills

necessary to succeed

in a certain sport.

The results suggest that

players with higher levels

of mental toughness

scored higher in

commitment, control and

challenge, on the other

hand, payers with higher

levels of mental

toughness scored lower in

negative energy control

and attention control.

Bull et al. 2005 12 male professional cricket

players.

Interviews designed

from four subscales: a)

personal view about

winning mindset and

mental toughness, b)

personal theories how

winning mindset and

The study explored

mental toughness

levels of English

cricketers’ players

and their relationship

with their sports

performance.

The results suggest that

players with higher levels

of mental toughness have

higher levels of self-

believe, motivation,

problem coping approach,

and control over

11

mental toughness were

developed, c) cope with

pressure, and d) the role

of training in the

development of mental

toughness.

emotions. Which take

altogether are essential

for the execution of

successful sports

performance.

Jones, Hanton

and

Connaughton

2007 8 elite performers. 5 male and 3

females.

With sports success of 7

Olympic gold medals and 11

world championship titles

Age = 25-48.

Interviews designed

from four subscales: a)

attitude, b) training, c)

competition and d) post-

competition.

The study explored

which psychological

and physiological

factors are necessary

for elite athletes to

consider mentally

tough

The results suggest that

higher levels of mental

toughness are associated

with problem coping

approach, optimism,

control under pressure,

determination,

confidence, control over

the emotions, self-believe

and coping with success

or failure which taken all

together have a positive

relationship with sports

performance and

outcome.

Connaughton

et al.

2008 7 (male=5 and female=2) elite

international athletes (all

athletes have been achieved

success on Olympic games)

Age = 27 to 35 years old (mean

= 33±5.3).

Face to face, or

telephone interviews.

The study explored

how to develop

mental toughness and

does mental

toughness requires

maintenance.

The results suggest that

the development of

mental toughness is a

long term process which

is strongly related to

motivational climate and

various individuals.

Additionally, desire and

motivation for success are

necessary to maintain

mental toughness.

12

developed, c) cope with

pressure, and d) the role

of training in the

development of mental

toughness.

emotions. Which take

altogether are essential

for the execution of

successful sports

performance.

Jones, Hanton

and

Connaughton

2007 8 elite performers. 5 male and 3

females.

With sports success of 7

Olympic gold medals and 11

world championship titles

Age = 25-48.

Interviews designed

from four subscales: a)

attitude, b) training, c)

competition and d) post-

competition.

The study explored

which psychological

and physiological

factors are necessary

for elite athletes to

consider mentally

tough

The results suggest that

higher levels of mental

toughness are associated

with problem coping

approach, optimism,

control under pressure,

determination,

confidence, control over

the emotions, self-believe

and coping with success

or failure which taken all

together have a positive

relationship with sports

performance and

outcome.

Connaughton

et al.

2008 7 (male=5 and female=2) elite

international athletes (all

athletes have been achieved

success on Olympic games)

Age = 27 to 35 years old (mean

= 33±5.3).

Face to face, or

telephone interviews.

The study explored

how to develop

mental toughness and

does mental

toughness requires

maintenance.

The results suggest that

the development of

mental toughness is a

long term process which

is strongly related to

motivational climate and

various individuals.

Additionally, desire and

motivation for success are

necessary to maintain

mental toughness.

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 44

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.