Analyzing the Effect of Code-Sharing Alliances on Airline Profitability

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/25

|8

|9330

|19

Report

AI Summary

This paper, published in the Journal of Air Transport Management, investigates the impact of code-sharing strategies and their integration into global alliances on airline performance, using a dataset of 81 airlines from 2007 to 2012. The study reveals a positive correlation between an airline's profit margin and the number of its code-sharing partners, with enhanced gains when a higher proportion of these partners belong to the same global alliance. The research introduces the concept of 'allied code-sharing partners' to measure the extent of an airline's allied code-sharing partnerships, finding that airlines can achieve greater profitability by increasing code-sharing partnerships with allied airlines. The findings suggest that airlines should consider whether to develop code-sharing partnerships with allied or non-allied airlines, which is particularly valuable for non-aligned airlines when choosing a beneficial global alliance to join. The study contributes to existing literature by analyzing the joint benefits of code-sharing partnerships and global alliances on airline performance, providing valuable implications for airline management seeking to develop the most rewarding code-sharing partnerships.

The effect of code-sharing alliances on airline profitability

Li Zou* , Xueqian Chen1

College of Business,Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University,Daytona Beach,FL 32114,USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 20 May 2016

Received in revised form

30 August 2016

Accepted 15 September 2016

Keywords:

Codesharing

Airline global alliances

Profitability

a b s t r a c t

Code sharing and global alliances both have been increasingly adopted by airlines worldwide in recent

years.A growing number of airlines,therefore,are embedded in networks of multilateral “coopetitive”

(i.e.,cooperative,but competitive) relationships that influence their product offering,pricing strategies,

operating efficiency,market power,and their overallsuccesses.There has been considerable research

analyzing the benefits for airlines from joining globalalliances,including bilateralcode-sharing part-

nerships.However,the joint effect of code-sharing and global alliances on airline performance has not

been fully investigated.In this paper,we study how the use of code-sharing strategies and their struc-

tural embeddedness into globalalliances may impact airline performance.Using a unique dataset

compiled from Flight Global and Airline Business's Annual Airline Alliance Report, the paper empirically

investigates the joint benefits of code-sharing partnerships and global alliances on airline profitability.

The results based on a group of 81 airlines during the 2007e2012 period show that the profit margin of

an airline is positively associated with the number ofcode-sharing partners it has.Furthermore,the

profit margin gains from code-sharing are greater when an airline has a higher proportion of its code-

sharing partners in the same globalalliance; i.e.,allied code-sharing partners.Finally,we find no sig-

nificant evidence that the percent of comprehensive code sharing partnerships to total partnerships has

an impact on profit margin.

© 2016 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Code-sharing arrangements,the most common type of airline

alliance, rapidly developed in the US domestic airline industry after

industry deregulation in 1978 and on international routes by the

late 1980s (Dresner, 2010). Under a code-sharing arrangement, one

airline can use its designation code on a flight operated by a second

carrier. The seats on that flight can be marketed and sold by the first

airline either to provide regionalconnections to complement its

own network (i.e.,complementary alliance) or to reduce competi-

tion by having only one airline actually operate on the route (i.e.

parallel alliance). There are several benefits for airlines from

developing code-sharing partnerships. For example, through code-

sharing arrangements,a major hub-and-spoke airline can use the

flights operated by its regional affiliates or partners to feed traffic

from spoke cities to its hub cities,enabling the efficient and suc-

cessful operation of hub-and-spoke networks.Code-sharing ar-

rangements also allow an airline to expand its service network

without committing its own resources; for example,by extending

its route coverage to more internationaldestinations that other-

wise cannot be served under the restrictive regulatory framework

for international air transport.

The distinct advantages associated with code-sharing arrange-

ment prompt many global airlines to enter into such partnerships,

first at a bilateral leveland later evolving into multilateral,more

formalized group alliances. In 1989, Wings, the first global alliance,

was established,mainly based on cooperation between KLM and

Northwest. In 1997, Star Alliance,the largest and most mature

alliance,was formed by five core members,including United,Luf-

thansa,SAS,Air Canada and Thai Airways Intl.One year after the

formation of Star Alliance, American Airlines, British Airways,

Qantas, Canadian Airlines, and Cathay Pacific teamed together and

formed their own alliance e Oneworld.In 2000,Skyteam Alliance

was founded by Air France, Delta, Korean Air, CSA, and Aeromexico.

Following the merger between Air France and KLM,all the major

member airlines of Wings joined Skyteam.With the extinction of

* Corresponding author.College of Business,Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Univer-

sity 600 S.Clyde Morris Blvd.,Daytona Beach,FL 32114,USA.

E-mail address: zoul@erau.edu (L.Zou).

1 Ms. Xueqian Chen is an undergraduate student in the accelerated MBA program

at the College of Business of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, and she helped

collect data for this project under the supervision of Dr. Li Zou during the spring of

2015.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Air Transport Management

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / j a i r t r a m a n

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2016.09.006

0969-6997/© 2016 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Journal of Air Transport Management 58 (2017) 50e57

Li Zou* , Xueqian Chen1

College of Business,Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University,Daytona Beach,FL 32114,USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 20 May 2016

Received in revised form

30 August 2016

Accepted 15 September 2016

Keywords:

Codesharing

Airline global alliances

Profitability

a b s t r a c t

Code sharing and global alliances both have been increasingly adopted by airlines worldwide in recent

years.A growing number of airlines,therefore,are embedded in networks of multilateral “coopetitive”

(i.e.,cooperative,but competitive) relationships that influence their product offering,pricing strategies,

operating efficiency,market power,and their overallsuccesses.There has been considerable research

analyzing the benefits for airlines from joining globalalliances,including bilateralcode-sharing part-

nerships.However,the joint effect of code-sharing and global alliances on airline performance has not

been fully investigated.In this paper,we study how the use of code-sharing strategies and their struc-

tural embeddedness into globalalliances may impact airline performance.Using a unique dataset

compiled from Flight Global and Airline Business's Annual Airline Alliance Report, the paper empirically

investigates the joint benefits of code-sharing partnerships and global alliances on airline profitability.

The results based on a group of 81 airlines during the 2007e2012 period show that the profit margin of

an airline is positively associated with the number ofcode-sharing partners it has.Furthermore,the

profit margin gains from code-sharing are greater when an airline has a higher proportion of its code-

sharing partners in the same globalalliance; i.e.,allied code-sharing partners.Finally,we find no sig-

nificant evidence that the percent of comprehensive code sharing partnerships to total partnerships has

an impact on profit margin.

© 2016 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Code-sharing arrangements,the most common type of airline

alliance, rapidly developed in the US domestic airline industry after

industry deregulation in 1978 and on international routes by the

late 1980s (Dresner, 2010). Under a code-sharing arrangement, one

airline can use its designation code on a flight operated by a second

carrier. The seats on that flight can be marketed and sold by the first

airline either to provide regionalconnections to complement its

own network (i.e.,complementary alliance) or to reduce competi-

tion by having only one airline actually operate on the route (i.e.

parallel alliance). There are several benefits for airlines from

developing code-sharing partnerships. For example, through code-

sharing arrangements,a major hub-and-spoke airline can use the

flights operated by its regional affiliates or partners to feed traffic

from spoke cities to its hub cities,enabling the efficient and suc-

cessful operation of hub-and-spoke networks.Code-sharing ar-

rangements also allow an airline to expand its service network

without committing its own resources; for example,by extending

its route coverage to more internationaldestinations that other-

wise cannot be served under the restrictive regulatory framework

for international air transport.

The distinct advantages associated with code-sharing arrange-

ment prompt many global airlines to enter into such partnerships,

first at a bilateral leveland later evolving into multilateral,more

formalized group alliances. In 1989, Wings, the first global alliance,

was established,mainly based on cooperation between KLM and

Northwest. In 1997, Star Alliance,the largest and most mature

alliance,was formed by five core members,including United,Luf-

thansa,SAS,Air Canada and Thai Airways Intl.One year after the

formation of Star Alliance, American Airlines, British Airways,

Qantas, Canadian Airlines, and Cathay Pacific teamed together and

formed their own alliance e Oneworld.In 2000,Skyteam Alliance

was founded by Air France, Delta, Korean Air, CSA, and Aeromexico.

Following the merger between Air France and KLM,all the major

member airlines of Wings joined Skyteam.With the extinction of

* Corresponding author.College of Business,Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Univer-

sity 600 S.Clyde Morris Blvd.,Daytona Beach,FL 32114,USA.

E-mail address: zoul@erau.edu (L.Zou).

1 Ms. Xueqian Chen is an undergraduate student in the accelerated MBA program

at the College of Business of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, and she helped

collect data for this project under the supervision of Dr. Li Zou during the spring of

2015.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Air Transport Management

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / j a i r t r a m a n

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2016.09.006

0969-6997/© 2016 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Journal of Air Transport Management 58 (2017) 50e57

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Wings,the remaining three global alliances e Star,Oneworld,and

Skyteam,continue their growth and expansion,increasing airline

membership by 58% from 34 in 2004 to 54 in 2012.

With the increasing prevalence ofcode-sharing partnerships

and global alliances,a growing number of airlines,therefore,have

recently been embedded in networks of multilateral “coopeti-

tivity”, meaning the coexistence ofcooperation and competition

among allied partners that influence productofferings,pricing

strategies,operating efficiency,market power,and overall perfor-

mance.On one hand,more and more airlines have formed closer

and deeper partnerships with allied airlines in the same global

alliance to leverage their joint branding,joint marketing,resource

sharing,etc.,for potential revenue gains,cost savings,or both.On

the other hand,airlines also have developed and maintained their

bilateralalliance relationships with non-aligned airlines or even

with airlines from rival group alliances. For many airlines, including

both aligned and non-aligned carriers,the bilateralcode-sharing

strategy remains a driver of revenue growth and cost savings.

Though there has been much research analyzing the benefits for

airlines either from joining global alliances or from building bilat-

eral code-sharing partnerships,an examination of the joint effects

of code-sharing and global alliances on airline performance is still

unexplored. In this paper, we focus on the question: To what extent

are the impacts from code-sharing strategies on an airline's per-

formance moderated by its structural embeddedness (or the lack

thereof) into global alliances? Using data collected from Flight

Global and the Annual Airline Alliance Summary Reportresults

published by Airline Business,we empirically investigate the com-

bined effects of code-sharing partnerships and global alliances on

airline performance.The results based on a group of81 airlines

during the 2007e2012 period show that the profit margin of an

airline is positively associated with the number ofcode-sharing

partners it has.Furthermore,the profit margin gains from code-

sharing partnerships are greaterwhen an airline has a higher

proportion of its code-sharing partners in the same global alliance,

i.e.,allied code-sharing partners.Perhaps,due to methodological

limitations,we do not find significant evidence that the levelof

cooperation moderates the profitability benefits for code-sharing

partners from a code-sharing strategy.Nevertheless,our finding

that there are joint benefits from code-sharing partnerships and

global alliances provides valuable implications for airline man-

agementseeking to develop the most rewarding code-sharing

partnerships in the context of global alliances.

This paper contributes to the existing literature and to airline

alliance managementin three ways: First, we develop a new

construct,namely, allied code-sharing partner,to represent the

code-sharing partnership formed between airlines in the same

global alliance. This construct is then used to measure the extent of

an airline's allied code-sharing partnerships compared to its total

number of code-sharing alliances.Through our empirical analysis,

we find evidence suggesting thatan airline can gain a greater

profitability benefit when it increases its code-sharing partnerships

with allied airlines. For airlines that are already in the three global

alliances (i.e.,Star,Oneworld,and Skyteam Alliance),this finding

can help them decide whether to develop code-sharing partner-

ships with allied or non-allied airlines.For those non-aligned air-

lines that have existing code-sharing arrangements,our findings

may be valuable in helping them to choose the most beneficial

global alliance to join. Second, although there is empirical research

estimating the impact of code-sharing alliances on airline perfor-

mance, the moderating effect of the depth of code-sharing alliances

(measured by the extent of route integration through code-sharing

arrangements) is unexplored.In this paper,we develop a conve-

nient instrument to measure the depth of code-sharing arrange-

ments in order to estimate their potentially moderating effects.

Finally,we contribute to the existent literature on airline alliances

by using a panel dataset that includes a broad sample of airlines

varying in operating scale, geographic region, and alliance

engagement.

In the following section, a literature review is provided. Section

3 introduces our hypotheses.Data descriptions and the empirical

models are presented in Section 4.The results are summarized in

Section 5.The last section concludes the paper and discusses po-

tential for future research.

2. Literature review

Dresner and Windle (1996) examine the early development of

airline alliances and code-sharing arrangementsand suggest

several rationales for the adoption of such strategies by a growing

number of international airlines in the 1990s. For most airlines, the

primary consideration of forming alliances is to expand global route

coverage and serve on international routes that would otherwise be

impossible to offer due to legal and regulatory restrictions. Through

code-sharing arrangements,the most common type of airline alli-

ance,each of the two partner airlines can market and sellseats

under its code on the flights operated by the partner carrier.Such

an arrangement may generate revenue to partner airlines through

market expansion,traffic feeds,improved connectivity,multiple

listings on Computer Reservation System (CRS) screens, etc.

Moreover, code-sharing arrangements and other alliance activities

may help the partner airlines reduce the cost per passenger because

of increased traffic, joint advertising,equipment sharing, etc.

Therefore,it is expected that airlines may gain competitive ad-

vantages by code-sharing,and that carriers that do not enter into

these partnerships are ata disadvantage (Dresner and Windle,

1996).

There are various types of code-sharing partnerships. In the US

domestic airline industry, the first code-sharing arrangement were

formed between major US airlines and their smaller regional

partners that provided service on lower density routes,and fed

traffic onto mainline routes operated by the major airline. This type

of code-sharing arrangement,known as “complementary code-

sharing,” has become an essentialcomponentof the hub-and-

spoke systems in the US domestic airline industry (Ito and Lee,

2007). On international routes, a similar type of code-sharing

arrangement has been adopted by internationalairlines to con-

nect their route networks and provide seamless connections for

passengerstraveling from one country to another and flying

beyond gateway hubs to inland destinations in the foreign country.

In contrast, so-called “parallelcode-sharing”arrangementsare

developed between two airlines that competed on routes prior to

forming partnerships (Park,1997).The study of airfare effects of

parallel versus complementary alliances has been a research topic

over the last two decades (Yousseff and Hansen, 1994; Oum et al.,

1996; Park,1997; Park and Zhang,2000; Brueckner,2001,2003;

Brueckner and Zhang,2001; Ito and Lee,2007; Wan et al.,2009;

Zou et al.,2011; Gayle and Brown,2014).The extent of coopera-

tion associated with code-sharing arrangements on international

routes also varies depending on whether antitrustimmunity is

granted or not.With antitrust immunity,the partner airlines are

allowed to jointly set airfares and capacity,enabling them to have

greater cooperation in terms ofairfares,flight scheduling,mar-

keting and capacity adjustments (Dresner and Windle, 1996;

Brueckner,2003).

Given the prevalence of code-sharing partnerships and the po-

tential anticompetitive concerns over antitrust immunity for the

alliances,Brueckner (2003) develops an in-depth study to investi-

gate the joint airfare effects of code-sharing alliances and antitrust

immunity.As an extension ofhis earlier results (Brueckner and

L. Zou,X. Chen / Journal of Air Transport Management 58 (2017) 50e57 51

Skyteam,continue their growth and expansion,increasing airline

membership by 58% from 34 in 2004 to 54 in 2012.

With the increasing prevalence ofcode-sharing partnerships

and global alliances,a growing number of airlines,therefore,have

recently been embedded in networks of multilateral “coopeti-

tivity”, meaning the coexistence ofcooperation and competition

among allied partners that influence productofferings,pricing

strategies,operating efficiency,market power,and overall perfor-

mance.On one hand,more and more airlines have formed closer

and deeper partnerships with allied airlines in the same global

alliance to leverage their joint branding,joint marketing,resource

sharing,etc.,for potential revenue gains,cost savings,or both.On

the other hand,airlines also have developed and maintained their

bilateralalliance relationships with non-aligned airlines or even

with airlines from rival group alliances. For many airlines, including

both aligned and non-aligned carriers,the bilateralcode-sharing

strategy remains a driver of revenue growth and cost savings.

Though there has been much research analyzing the benefits for

airlines either from joining global alliances or from building bilat-

eral code-sharing partnerships,an examination of the joint effects

of code-sharing and global alliances on airline performance is still

unexplored. In this paper, we focus on the question: To what extent

are the impacts from code-sharing strategies on an airline's per-

formance moderated by its structural embeddedness (or the lack

thereof) into global alliances? Using data collected from Flight

Global and the Annual Airline Alliance Summary Reportresults

published by Airline Business,we empirically investigate the com-

bined effects of code-sharing partnerships and global alliances on

airline performance.The results based on a group of81 airlines

during the 2007e2012 period show that the profit margin of an

airline is positively associated with the number ofcode-sharing

partners it has.Furthermore,the profit margin gains from code-

sharing partnerships are greaterwhen an airline has a higher

proportion of its code-sharing partners in the same global alliance,

i.e.,allied code-sharing partners.Perhaps,due to methodological

limitations,we do not find significant evidence that the levelof

cooperation moderates the profitability benefits for code-sharing

partners from a code-sharing strategy.Nevertheless,our finding

that there are joint benefits from code-sharing partnerships and

global alliances provides valuable implications for airline man-

agementseeking to develop the most rewarding code-sharing

partnerships in the context of global alliances.

This paper contributes to the existing literature and to airline

alliance managementin three ways: First, we develop a new

construct,namely, allied code-sharing partner,to represent the

code-sharing partnership formed between airlines in the same

global alliance. This construct is then used to measure the extent of

an airline's allied code-sharing partnerships compared to its total

number of code-sharing alliances.Through our empirical analysis,

we find evidence suggesting thatan airline can gain a greater

profitability benefit when it increases its code-sharing partnerships

with allied airlines. For airlines that are already in the three global

alliances (i.e.,Star,Oneworld,and Skyteam Alliance),this finding

can help them decide whether to develop code-sharing partner-

ships with allied or non-allied airlines.For those non-aligned air-

lines that have existing code-sharing arrangements,our findings

may be valuable in helping them to choose the most beneficial

global alliance to join. Second, although there is empirical research

estimating the impact of code-sharing alliances on airline perfor-

mance, the moderating effect of the depth of code-sharing alliances

(measured by the extent of route integration through code-sharing

arrangements) is unexplored.In this paper,we develop a conve-

nient instrument to measure the depth of code-sharing arrange-

ments in order to estimate their potentially moderating effects.

Finally,we contribute to the existent literature on airline alliances

by using a panel dataset that includes a broad sample of airlines

varying in operating scale, geographic region, and alliance

engagement.

In the following section, a literature review is provided. Section

3 introduces our hypotheses.Data descriptions and the empirical

models are presented in Section 4.The results are summarized in

Section 5.The last section concludes the paper and discusses po-

tential for future research.

2. Literature review

Dresner and Windle (1996) examine the early development of

airline alliances and code-sharing arrangementsand suggest

several rationales for the adoption of such strategies by a growing

number of international airlines in the 1990s. For most airlines, the

primary consideration of forming alliances is to expand global route

coverage and serve on international routes that would otherwise be

impossible to offer due to legal and regulatory restrictions. Through

code-sharing arrangements,the most common type of airline alli-

ance,each of the two partner airlines can market and sellseats

under its code on the flights operated by the partner carrier.Such

an arrangement may generate revenue to partner airlines through

market expansion,traffic feeds,improved connectivity,multiple

listings on Computer Reservation System (CRS) screens, etc.

Moreover, code-sharing arrangements and other alliance activities

may help the partner airlines reduce the cost per passenger because

of increased traffic, joint advertising,equipment sharing, etc.

Therefore,it is expected that airlines may gain competitive ad-

vantages by code-sharing,and that carriers that do not enter into

these partnerships are ata disadvantage (Dresner and Windle,

1996).

There are various types of code-sharing partnerships. In the US

domestic airline industry, the first code-sharing arrangement were

formed between major US airlines and their smaller regional

partners that provided service on lower density routes,and fed

traffic onto mainline routes operated by the major airline. This type

of code-sharing arrangement,known as “complementary code-

sharing,” has become an essentialcomponentof the hub-and-

spoke systems in the US domestic airline industry (Ito and Lee,

2007). On international routes, a similar type of code-sharing

arrangement has been adopted by internationalairlines to con-

nect their route networks and provide seamless connections for

passengerstraveling from one country to another and flying

beyond gateway hubs to inland destinations in the foreign country.

In contrast, so-called “parallelcode-sharing”arrangementsare

developed between two airlines that competed on routes prior to

forming partnerships (Park,1997).The study of airfare effects of

parallel versus complementary alliances has been a research topic

over the last two decades (Yousseff and Hansen, 1994; Oum et al.,

1996; Park,1997; Park and Zhang,2000; Brueckner,2001,2003;

Brueckner and Zhang,2001; Ito and Lee,2007; Wan et al.,2009;

Zou et al.,2011; Gayle and Brown,2014).The extent of coopera-

tion associated with code-sharing arrangements on international

routes also varies depending on whether antitrustimmunity is

granted or not.With antitrust immunity,the partner airlines are

allowed to jointly set airfares and capacity,enabling them to have

greater cooperation in terms ofairfares,flight scheduling,mar-

keting and capacity adjustments (Dresner and Windle, 1996;

Brueckner,2003).

Given the prevalence of code-sharing partnerships and the po-

tential anticompetitive concerns over antitrust immunity for the

alliances,Brueckner (2003) develops an in-depth study to investi-

gate the joint airfare effects of code-sharing alliances and antitrust

immunity.As an extension ofhis earlier results (Brueckner and

L. Zou,X. Chen / Journal of Air Transport Management 58 (2017) 50e57 51

Whalen, 2000), Brueckner (2003) finds strong evidence that airline

cooperation through either code-sharing or antitrustimmunity

leads to airfare reductions for interline passengers on international

routes. However, the combined airfare reduction effects from code

sharing and antitrust immunity were found to be smaller than the

separate, individual effects. Such airfare reductions generate

further benefits for interline passengers above and beyond the

improved convenience and tighter connections associated with

code-shared flights.

Gayle and Brown (2014) compare the average airfare, traffic and

market share on routes connecting the 50 largest cities in the US

before and after the implementation ofalliances among Delta,

Continental, and Northwest Airlines in 2003 and find no statistical

evidence for collusive pricing on code-shared routes.Instead,a

traffic increase is found on routes where these three airlines have

code-sharing arrangements.The demand increase only existed on

routes where the joint market share between two allied airlines

was greater than 0.49 prior to their code-sharing alliance.Accord-

ing to the authors, the traffic stimulating effects can be attributed to

the enhanced opportunity for passengersto accumulate and

redeem frequent flier points with code-sharing partner airlines. In

other words,the formation of code-sharing partnerships seems to

bring additionalbenefits to airlines that already have a base of

customers that are loyal to either one of the partners prior to the

alliance.Through code-sharing alliances,loyalty may induce loy-

alty; thus,the total traffic of the code-sharing partners is greater

than the sum of the traffic of the individual airlines.

While there has been a generalconsensus abouthow code-

sharing alliances affect airfares in both the domestic and interna-

tional context,its overall impacts on airline performance are less

certain, with mixed findings in the existent literature. For example,

in their study of the three alliances formed between US airlines and

their European counterparts in the 1990s,including Continental

Airlines/SAS,Delta/Swissair,and Northwest/KLM, Dresner et al.

(1995) find that not all three alliances generate greaterthan

average increase in traffic and load factor in their markets.There-

fore, they conclude that the expected benefits from alliances are not

guaranteed,even after the partner airlines realign their route net-

works for improved connectivity. By contrast, in studying the code-

sharing alliances between US Air and British Airways and between

Northwest and KLM,Gellman Research Associates (1994),using a

different methodology,find evidence in support of the positive

traffic and revenue effects of these alliances. Their methodology is

based on passenger selection outcomes among alternative traveling

options,which are then employed to derive values placed by pas-

sengers on fares,flight time, connections,codesharing arrange-

ments, etc. Based in part on interview data and airline internal data,

the US General Accounting Office (1995) reports large traffic gains

and revenue increases for three strategic code-sharing alliances,

including Northwest/KLM (formed in 1992),USAir/British Airways

(1993), and United/Lufthansa (1994). As for the four regional code-

sharing alliances examined,two are found to result in modest in-

creases in traffic and revenue,including United/Ansett Australia

and United/British Midland,while the other two e Northwest/

Ansett Australia and TWA/Gulf Air fall, are not. According to the US

General Accounting Office (GAO, 1995), the majority of the 61 code-

sharing partnerships have a low degree of route integration at that

time and therefore, they are not profitable or long lasting.

Morrish and Hamilton (2002) provide a comprehensive review

of airline alliances and their impacts on airline performance in both

economic and non-economic terms.As Morrish and Hamilton

(2002) note,‘there is no conclusive evidence to date that major

airlines have been able to use global alliances to restrict competi-

tion and boost their own profitability.’They further suggest that

although alliance partnersmight experience some increase in

traffic,load factor,and productivity from alliances,these benefits

may be partially or even totally offset by greater frequencies and

lower airfares,thereby resulting in modest or little profit gains.

Pitfield (2007) echoes the view saying that an analysis using data

from the US Bureau Transportation Statistics ‘does not yield un-

ambiguous conclusions in accordance with theory or expectation’

about the positive impacts of code-sharing alliances on traffic and

market share of partner airlines. These inconclusive findings at the

route levelmay be due to the complexity of supply and demand

interactions,unidentifiable route characteristics,and/or diverse

regulatory and competitive environments (Pitfield, 2007).

The integration between airlines in code-sharing alliances may

be extensive, and distinct for different arrangements. Depending on

the specifics of each alliance,the market coverage ranges from

limited to comprehensive,and from point-specific to regional and

strategic.The scope of cooperation may include a variety of areas,

such as scheduling, route networks, operations, advertising,

frequent flyer programs, etc. As a result, it is necessary to take into

account the level and characteristics of code-sharing arrangements

when estimating the benefits to the partner airlines.For example,

in the study by Oum et al.(2004),the authors categorize alliances

into high-level and low-level by the degree of cooperation involved.

A high-level alliance involves network-level collaboration, through

which the allied airlines link their route networks. By contrast, the

collaboration in a low-level alliances only occurs at the route level

without combining the entire networks.The authors estimate the

impacts of alliances on airline productivity and profitability

focusing on the 108 alliances formed among the 22 leading inter-

national airlines during the 1986e1995 period.Their results sug-

gest that although alliances in general only lead to the

improvement of productivity (not profitability),strategic alliances

characterized by high-level cooperation contribute to both higher

productivity and greater profitability.

Yousseffand Hansen (1994) consider technicalefficiency and

market power as two primary factors leading to increased profit-

ability for airlines from participation in code-sharing alliances.

More specifically, improvement in technical efficiency will

contribute to unit cost reduction and can be accomplished through

traffic increase,route network consolidation, resource sharing,

flight scheduling optimization, and greater outputs in terms of the

quality and quantity of connecting services,etc.In addition to the

cost saving benefit, the formation of alliances, in general, is viewed

as a means for airlines to restrain competition, preclude rivalry, and

seek virtual monopoly status.Alliances allow carriers to retain

market power which otherwise might be threatened as the long-

standing regulatory regimes for air transportare replaced with

liberalization over time (Yousseff and Hansen, 1994).On the other

hand, the new entrants may also resort to code-sharing alliances as

a strategy to help strengthen their market power against the

dominant market leader.Using data for 56 airlines during the

1986e1993 period, Park and Cho (1997) find evidence showing that

the combined market share ofpartner airlines is more likely to

increase afterthe formation of code-sharing alliance and such

market share gains are higher when the alliance is formed between

two relatively new entrants on a route,and when the market has

fewer competitors and it is growing quickly.

There may be inconsistencies between theoreticalpredictions

and empirical results regarding the cost effects from code-sharing

alliances.In a survey conducted by Iatrou and Alamdari(2005)

among managers of alliance departments at 28 airlines belonging

to the four global alliances in 2002,the respondents,on average,

perceive cost to be least affected by alliances,compared to other

factors, such as fares, revenue, load factor, and traffic. Moreover, as

compared to outcomes such as traffic growth, load factor increases,

and revenue growth, cost reduction is cited much less as an

L. Zou,X. Chen / Journal of Air Transport Management 58 (2017) 50e5752

cooperation through either code-sharing or antitrustimmunity

leads to airfare reductions for interline passengers on international

routes. However, the combined airfare reduction effects from code

sharing and antitrust immunity were found to be smaller than the

separate, individual effects. Such airfare reductions generate

further benefits for interline passengers above and beyond the

improved convenience and tighter connections associated with

code-shared flights.

Gayle and Brown (2014) compare the average airfare, traffic and

market share on routes connecting the 50 largest cities in the US

before and after the implementation ofalliances among Delta,

Continental, and Northwest Airlines in 2003 and find no statistical

evidence for collusive pricing on code-shared routes.Instead,a

traffic increase is found on routes where these three airlines have

code-sharing arrangements.The demand increase only existed on

routes where the joint market share between two allied airlines

was greater than 0.49 prior to their code-sharing alliance.Accord-

ing to the authors, the traffic stimulating effects can be attributed to

the enhanced opportunity for passengersto accumulate and

redeem frequent flier points with code-sharing partner airlines. In

other words,the formation of code-sharing partnerships seems to

bring additionalbenefits to airlines that already have a base of

customers that are loyal to either one of the partners prior to the

alliance.Through code-sharing alliances,loyalty may induce loy-

alty; thus,the total traffic of the code-sharing partners is greater

than the sum of the traffic of the individual airlines.

While there has been a generalconsensus abouthow code-

sharing alliances affect airfares in both the domestic and interna-

tional context,its overall impacts on airline performance are less

certain, with mixed findings in the existent literature. For example,

in their study of the three alliances formed between US airlines and

their European counterparts in the 1990s,including Continental

Airlines/SAS,Delta/Swissair,and Northwest/KLM, Dresner et al.

(1995) find that not all three alliances generate greaterthan

average increase in traffic and load factor in their markets.There-

fore, they conclude that the expected benefits from alliances are not

guaranteed,even after the partner airlines realign their route net-

works for improved connectivity. By contrast, in studying the code-

sharing alliances between US Air and British Airways and between

Northwest and KLM,Gellman Research Associates (1994),using a

different methodology,find evidence in support of the positive

traffic and revenue effects of these alliances. Their methodology is

based on passenger selection outcomes among alternative traveling

options,which are then employed to derive values placed by pas-

sengers on fares,flight time, connections,codesharing arrange-

ments, etc. Based in part on interview data and airline internal data,

the US General Accounting Office (1995) reports large traffic gains

and revenue increases for three strategic code-sharing alliances,

including Northwest/KLM (formed in 1992),USAir/British Airways

(1993), and United/Lufthansa (1994). As for the four regional code-

sharing alliances examined,two are found to result in modest in-

creases in traffic and revenue,including United/Ansett Australia

and United/British Midland,while the other two e Northwest/

Ansett Australia and TWA/Gulf Air fall, are not. According to the US

General Accounting Office (GAO, 1995), the majority of the 61 code-

sharing partnerships have a low degree of route integration at that

time and therefore, they are not profitable or long lasting.

Morrish and Hamilton (2002) provide a comprehensive review

of airline alliances and their impacts on airline performance in both

economic and non-economic terms.As Morrish and Hamilton

(2002) note,‘there is no conclusive evidence to date that major

airlines have been able to use global alliances to restrict competi-

tion and boost their own profitability.’They further suggest that

although alliance partnersmight experience some increase in

traffic,load factor,and productivity from alliances,these benefits

may be partially or even totally offset by greater frequencies and

lower airfares,thereby resulting in modest or little profit gains.

Pitfield (2007) echoes the view saying that an analysis using data

from the US Bureau Transportation Statistics ‘does not yield un-

ambiguous conclusions in accordance with theory or expectation’

about the positive impacts of code-sharing alliances on traffic and

market share of partner airlines. These inconclusive findings at the

route levelmay be due to the complexity of supply and demand

interactions,unidentifiable route characteristics,and/or diverse

regulatory and competitive environments (Pitfield, 2007).

The integration between airlines in code-sharing alliances may

be extensive, and distinct for different arrangements. Depending on

the specifics of each alliance,the market coverage ranges from

limited to comprehensive,and from point-specific to regional and

strategic.The scope of cooperation may include a variety of areas,

such as scheduling, route networks, operations, advertising,

frequent flyer programs, etc. As a result, it is necessary to take into

account the level and characteristics of code-sharing arrangements

when estimating the benefits to the partner airlines.For example,

in the study by Oum et al.(2004),the authors categorize alliances

into high-level and low-level by the degree of cooperation involved.

A high-level alliance involves network-level collaboration, through

which the allied airlines link their route networks. By contrast, the

collaboration in a low-level alliances only occurs at the route level

without combining the entire networks.The authors estimate the

impacts of alliances on airline productivity and profitability

focusing on the 108 alliances formed among the 22 leading inter-

national airlines during the 1986e1995 period.Their results sug-

gest that although alliances in general only lead to the

improvement of productivity (not profitability),strategic alliances

characterized by high-level cooperation contribute to both higher

productivity and greater profitability.

Yousseffand Hansen (1994) consider technicalefficiency and

market power as two primary factors leading to increased profit-

ability for airlines from participation in code-sharing alliances.

More specifically, improvement in technical efficiency will

contribute to unit cost reduction and can be accomplished through

traffic increase,route network consolidation, resource sharing,

flight scheduling optimization, and greater outputs in terms of the

quality and quantity of connecting services,etc.In addition to the

cost saving benefit, the formation of alliances, in general, is viewed

as a means for airlines to restrain competition, preclude rivalry, and

seek virtual monopoly status.Alliances allow carriers to retain

market power which otherwise might be threatened as the long-

standing regulatory regimes for air transportare replaced with

liberalization over time (Yousseff and Hansen, 1994).On the other

hand, the new entrants may also resort to code-sharing alliances as

a strategy to help strengthen their market power against the

dominant market leader.Using data for 56 airlines during the

1986e1993 period, Park and Cho (1997) find evidence showing that

the combined market share ofpartner airlines is more likely to

increase afterthe formation of code-sharing alliance and such

market share gains are higher when the alliance is formed between

two relatively new entrants on a route,and when the market has

fewer competitors and it is growing quickly.

There may be inconsistencies between theoreticalpredictions

and empirical results regarding the cost effects from code-sharing

alliances.In a survey conducted by Iatrou and Alamdari(2005)

among managers of alliance departments at 28 airlines belonging

to the four global alliances in 2002,the respondents,on average,

perceive cost to be least affected by alliances,compared to other

factors, such as fares, revenue, load factor, and traffic. Moreover, as

compared to outcomes such as traffic growth, load factor increases,

and revenue growth, cost reduction is cited much less as an

L. Zou,X. Chen / Journal of Air Transport Management 58 (2017) 50e5752

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

outcome of code sharing by the participating respondents. In sum,

Iatrou and Alamdari (2005) find that code-sharing is the most

effective type ofalliance for providing airlines distinctrevenue

benefits in terms of traffic and load factor increases. As for the cost

effects, the authors do not observe the same discernable benefits, as

widely acknowledged by airline alliance managers.The cost re-

ductions associated with alliances are nonexistent or very small, at

least in the short run. Through estimating a structural econometric

model, Gayle and Le (2013) decompose the cost effects of code-

sharing alliances atthe route level into three types: short-run

marginalcost,medium-to long-run sunk market entry cost,and

recurring fixed costs.Using a difference-in-differences estimation

methodology, Gayle and Le (2013) focus on the three-way alliances

among Delta, Northwest and Continental to investigate the alliance

effects in contributing to cost changes at these three airlines. Their

results suggest that the Delta-Northwest-Continentalalliance al-

lows the three partners to decrease their marginal costs, especially

when they have a dominant market presence at origin and desti-

nation endpoints,and to decrease their market entry sunk costs.

However, the three airlines are found to have increased fixed costs

following their alliances, implying that the overall cost effects from

alliances are uncertain because of these offsetting consequences.

The assessment of the profitability effects of code-sharing alli-

ances needs to take into account severaltradeoff,with consider-

ation to the following issues: First, “parallel” and “complementary”

code-sharing alliances have distinct effects in terms on traffic, load

factor, service, airfare, and revenue. The different outcomes are also

contingent upon whether the alliance is endowed with antitrust

immunity. Second, the traffic increase resulting from code-sharing

alliances may not be sufficient to offset the potential airfare

reduction and the incrementalcosts incurred.Thus, the overall

profitability effects cannot be assessed based on changes in traffic

or revenue alone.Third, the effects of code-sharing alliances may

not be the same across all routes because of distinct route-related

market structure and demand characteristics.Moreover, even

though partner airlines may win traffic from rival airlines due to

alliance agreements,the rival airlines in response may retaliate,

punitively,on overlapping routes with the partner airlines and

cause the loss of traffic for the partner airlines on some of their non-

codeshared routes. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the overall

effects ofcode-sharing alliances not only at the route level,but

throughout the network.

3. Hypotheses development

As stated above,it is necessary to consider both the potential

revenue and cost effects in a code-sharing arrangement for an ac-

curate assessment of its overall profitability.In contrast to a great

number of studies investigating revenue effects,empirical studies

on the cost effects of code-sharing alliances are very limited.As

noted by Gayle and Le (2013), the lack of the research, in part, is due

to the difficulty in disaggregating costdata to the route level.

Theoretically,the overall effect of alliances on the total cost of air-

lines (including marginal costs, market entry costs, and fixed costs)

may be uncertain.On one hand,code-sharing alliances may help

the two partner airlines consolidate their traffic by reducing or

eliminating duplicate flights.The practice of code sharing also en-

ables airlines to expand their route networks, optimize flight

schedules,and improve connecting services,thereby attracting

new passengers and increasing traffic. The increased traffic density

can lead to a marginal cost reduction. Moreover, an airline under a

code-sharing arrangementcan enter new markets by using the

flights of its partner airlines.Thus, the airline can avoid making

investments in route development, thereby saving costs associated

with market entry. On the other hand, to accommodate the

increased traffic resulting from code-sharing alliances,the two

partner airlines may have to incur costs acquiring baggage handling

facilities, airport gates, check-in counters, airplanes, etc., if there is a

traffic volume increase beyond their joint capacity. Because of these

offsetting effects,Gayle and Le (2013)further suggestthat the

overall impact on the totalcosts of partner airlines willbe small

after considering both the positive and negative forces. This view is

consistent with empirical findings in the studies by Goh and Yong

(2006),Gagnepain and Marin (2010),and Chen (2000).

The survey research by Iatrou and Alamdari (2005), based on the

questionnaires filled by alliance managers of28 airlines partici-

pating in Wings, Star, oneworld and Skyteam in 2002 also indicate

that cost is perceived to be least affected by the formation of alli-

ances,compared to severalother aspects of airline operations,

including airfares,load factor,revenue and traffic.

Using firm-level data for 10 US airlines from 1994 through 2001,

Goh and Yong (2006) estimate a truncated third-order translog cost

function and find that ‘ … alliances do appear to lower costs.

However,while the impacts are statistically significant,in eco-

nomic terms the magnitude appears to be immaterial.’On the

revenue side,the majority of the existent literature provides both

theoretical arguments and empirical support for the revenue ben-

efits from codesharing alliances.Thus, we propose the following

hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1. The operating margin ofan airline is positively

associated with the number of code-sharing partners it has.

The level of cooperation between two code-sharing partners can

be enhanced when the partners are in the same globalalliance.

Through sharing airport lounges,joint marketing,branding and

frequent flier programs, etc., allied airlines have more opportunities

to improve their connecting services involving code-shared flights,

and to make their services more seamless.Moreover,the service

standards followed by airlines in the same global alliances tend to

be more harmonized and consistent.Hence, code-share flights

offered by airlines in the same global alliance may be more

appealing to passengers,as compared to code-share flights by air-

lines not in the same global alliances. From the passenger’s

perspective, Goh and Uncles (2003) discuss five main benefits that

air travelers (especially business travelers) may be aware of when

choosing airlines in the same global alliance: “a) greater network

access; b) seamless travel; c) transferablepriority status; d)

extended lounge access; and e) enhanced frequent-flyer program.”

The first two can be regarded as benefits associated with code-

sharing partnerships,while the last three are benefits thatare

more relevant to global alliances in general. The offering of all these

benefits would be most likely when the code-sharing partnership is

formed between allied airlines.As outlined by Goh and Uncles

(2003),the full awareness of these benefits,and their actualde-

livery, would increase customer loyalty to a particular airline or

alliance group, a source of competitive advantage. In line with this

argument, we hypothesize that profitability gains would be greater

as an airline increases its code-sharing partnership with airlines in

the same global alliance.

Hypothesis 2. The operating margin ofan airline is positively

associated with the percentage ofallied code-sharing partners (i.e.,

those in the same global alliance as the focal airline) it has compared

its total number of code-sharing partners.

For two airlines in a code-sharing relationship, the more routes

that are code-shared, the more integrated are their route networks.

On the supply side,the increased number of code-shared routes

enables the partner airlines to add more destinations.This en-

hances the combined route networks, bringing greater efficiencies

and cost saving benefitsfrom improved traffic density to the

L. Zou,X. Chen / Journal of Air Transport Management 58 (2017) 50e57 53

Iatrou and Alamdari (2005) find that code-sharing is the most

effective type ofalliance for providing airlines distinctrevenue

benefits in terms of traffic and load factor increases. As for the cost

effects, the authors do not observe the same discernable benefits, as

widely acknowledged by airline alliance managers.The cost re-

ductions associated with alliances are nonexistent or very small, at

least in the short run. Through estimating a structural econometric

model, Gayle and Le (2013) decompose the cost effects of code-

sharing alliances atthe route level into three types: short-run

marginalcost,medium-to long-run sunk market entry cost,and

recurring fixed costs.Using a difference-in-differences estimation

methodology, Gayle and Le (2013) focus on the three-way alliances

among Delta, Northwest and Continental to investigate the alliance

effects in contributing to cost changes at these three airlines. Their

results suggest that the Delta-Northwest-Continentalalliance al-

lows the three partners to decrease their marginal costs, especially

when they have a dominant market presence at origin and desti-

nation endpoints,and to decrease their market entry sunk costs.

However, the three airlines are found to have increased fixed costs

following their alliances, implying that the overall cost effects from

alliances are uncertain because of these offsetting consequences.

The assessment of the profitability effects of code-sharing alli-

ances needs to take into account severaltradeoff,with consider-

ation to the following issues: First, “parallel” and “complementary”

code-sharing alliances have distinct effects in terms on traffic, load

factor, service, airfare, and revenue. The different outcomes are also

contingent upon whether the alliance is endowed with antitrust

immunity. Second, the traffic increase resulting from code-sharing

alliances may not be sufficient to offset the potential airfare

reduction and the incrementalcosts incurred.Thus, the overall

profitability effects cannot be assessed based on changes in traffic

or revenue alone.Third, the effects of code-sharing alliances may

not be the same across all routes because of distinct route-related

market structure and demand characteristics.Moreover, even

though partner airlines may win traffic from rival airlines due to

alliance agreements,the rival airlines in response may retaliate,

punitively,on overlapping routes with the partner airlines and

cause the loss of traffic for the partner airlines on some of their non-

codeshared routes. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the overall

effects ofcode-sharing alliances not only at the route level,but

throughout the network.

3. Hypotheses development

As stated above,it is necessary to consider both the potential

revenue and cost effects in a code-sharing arrangement for an ac-

curate assessment of its overall profitability.In contrast to a great

number of studies investigating revenue effects,empirical studies

on the cost effects of code-sharing alliances are very limited.As

noted by Gayle and Le (2013), the lack of the research, in part, is due

to the difficulty in disaggregating costdata to the route level.

Theoretically,the overall effect of alliances on the total cost of air-

lines (including marginal costs, market entry costs, and fixed costs)

may be uncertain.On one hand,code-sharing alliances may help

the two partner airlines consolidate their traffic by reducing or

eliminating duplicate flights.The practice of code sharing also en-

ables airlines to expand their route networks, optimize flight

schedules,and improve connecting services,thereby attracting

new passengers and increasing traffic. The increased traffic density

can lead to a marginal cost reduction. Moreover, an airline under a

code-sharing arrangementcan enter new markets by using the

flights of its partner airlines.Thus, the airline can avoid making

investments in route development, thereby saving costs associated

with market entry. On the other hand, to accommodate the

increased traffic resulting from code-sharing alliances,the two

partner airlines may have to incur costs acquiring baggage handling

facilities, airport gates, check-in counters, airplanes, etc., if there is a

traffic volume increase beyond their joint capacity. Because of these

offsetting effects,Gayle and Le (2013)further suggestthat the

overall impact on the totalcosts of partner airlines willbe small

after considering both the positive and negative forces. This view is

consistent with empirical findings in the studies by Goh and Yong

(2006),Gagnepain and Marin (2010),and Chen (2000).

The survey research by Iatrou and Alamdari (2005), based on the

questionnaires filled by alliance managers of28 airlines partici-

pating in Wings, Star, oneworld and Skyteam in 2002 also indicate

that cost is perceived to be least affected by the formation of alli-

ances,compared to severalother aspects of airline operations,

including airfares,load factor,revenue and traffic.

Using firm-level data for 10 US airlines from 1994 through 2001,

Goh and Yong (2006) estimate a truncated third-order translog cost

function and find that ‘ … alliances do appear to lower costs.

However,while the impacts are statistically significant,in eco-

nomic terms the magnitude appears to be immaterial.’On the

revenue side,the majority of the existent literature provides both

theoretical arguments and empirical support for the revenue ben-

efits from codesharing alliances.Thus, we propose the following

hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1. The operating margin ofan airline is positively

associated with the number of code-sharing partners it has.

The level of cooperation between two code-sharing partners can

be enhanced when the partners are in the same globalalliance.

Through sharing airport lounges,joint marketing,branding and

frequent flier programs, etc., allied airlines have more opportunities

to improve their connecting services involving code-shared flights,

and to make their services more seamless.Moreover,the service

standards followed by airlines in the same global alliances tend to

be more harmonized and consistent.Hence, code-share flights

offered by airlines in the same global alliance may be more

appealing to passengers,as compared to code-share flights by air-

lines not in the same global alliances. From the passenger’s

perspective, Goh and Uncles (2003) discuss five main benefits that

air travelers (especially business travelers) may be aware of when

choosing airlines in the same global alliance: “a) greater network

access; b) seamless travel; c) transferablepriority status; d)

extended lounge access; and e) enhanced frequent-flyer program.”

The first two can be regarded as benefits associated with code-

sharing partnerships,while the last three are benefits thatare

more relevant to global alliances in general. The offering of all these

benefits would be most likely when the code-sharing partnership is

formed between allied airlines.As outlined by Goh and Uncles

(2003),the full awareness of these benefits,and their actualde-

livery, would increase customer loyalty to a particular airline or

alliance group, a source of competitive advantage. In line with this

argument, we hypothesize that profitability gains would be greater

as an airline increases its code-sharing partnership with airlines in

the same global alliance.

Hypothesis 2. The operating margin ofan airline is positively

associated with the percentage ofallied code-sharing partners (i.e.,

those in the same global alliance as the focal airline) it has compared

its total number of code-sharing partners.

For two airlines in a code-sharing relationship, the more routes

that are code-shared, the more integrated are their route networks.

On the supply side,the increased number of code-shared routes

enables the partner airlines to add more destinations.This en-

hances the combined route networks, bringing greater efficiencies

and cost saving benefitsfrom improved traffic density to the

L. Zou,X. Chen / Journal of Air Transport Management 58 (2017) 50e57 53

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

partners.There are also several demand-side benefits to having a

greater scope of code-sharing practices.According to Yousseff and

Hansen,1994, the quality and quantity of connecting services

may increase because ofimproved scheduling coordination.As

partner airlines have more routes codeshared with each other,the

extended route network and will entice passengers to pay higher

airfares as a result.Moreover,the benefits to passengers from the

joint frequent flier programs offered by partner airlines are multi-

plied as code-sharing airlines increase the extent oftheir route

integration.Finally,due to passengers’incomplete information,a

large route network can provide an airline with some marketing

advantages as it is more likely to be selected by passengers.More

specifically,the US GAO,(1995) writes the following while discus-

sing potential factors influencing the benefits for participating

airlines from code-sharing alliances.

‘The extent to which airlines participating in alliances benefit from

them varies greatly and depends on the (1) geographic scope of the

code-sharing arrangement,(2) levelof operating and marketing

integration achieved by the airlines,and (3) agreement between

the airlines on how to divide revenues.’

Thus, our Hypothesis 3 is the following:

Hypothesis 3. The operating margin ofan airline is positively

associated with the percentage of comprehensive code-sharing part-

ners (i.e., those having a comprehensive code-sharing partnership with

the focal airline) compared to its total number of code-sharing

partners.

In Hypothesis 3, the comprehensive code-sharing partnersrefer

to those having ten or more code-shared routes. As explained in the

following section,the data we use in the analysis is derived from

the annual Airline Alliance Survey report published by Airline

Business.The annual survey categorizes the type of code-sharing

alliances as limited or comprehensive,with limited code-sharing

alliances defined as agreements with up to 10 routes covered and

comprehensive agreements with at least 10 routes covered.

4. Data and methodology

The data for our analysis is mainly collected from FlightGlobal

and the Airline Alliance Survey published by Airline Business.In its

annual Airline Alliance Survey report,the Airline Business maga-

zine provides a list of codesharing agreements for each member

airline of the Star, Skyteam and Oneworld Alliances. In addition, the

report provides code-sharing agreement information for a group of

leading non-aligned airlines. The code-sharing agreements

compiled in the report are relevant to allairlines featured in the

Airline Business Top 200 Passenger Rankings list. The alliance survey

data is supplemented by airline performance and operating char-

acteristics drawn from FlightGlobal.

Using panel data for 81 airlines from 2007 to 2012, we estimate

the effects on profit margin to a focal airline from: a) the number of

codesharing partners;b) the percentage of allied codesharing

partners; and c) the percentage ofcomprehensive codesharing

partners,while controlling for other variables,such as load factor,

passenger yield,unit cost,operating scale (measured by ASK),and

global alliance membership. During the study period, the number of

airlines in the Star Alliance increased from 22 to 27, in the Skyteam

Alliance from 12 to 17, and remained 11 in the Oneworld Alliance. In

our initial sample, there are a total of 92 airlines, including 24 in Star,

19 in Skyteam,and 11 in Oneword.The remaining 38 are non-

aligned airlines.After the exclusion of airlines with missing per-

formance data, our final sample covers 81 airlines with a total of 486

annual observations from 2007 through 2012,including 136 ob-

servations for Star Alliance,83 for Skyteam,66 for Oneworld,and

201 for the non-aligned group. Table 1 provides the descriptions for

key variables as well as summary statistics.

Table 2 presents the correlations between all key variables.

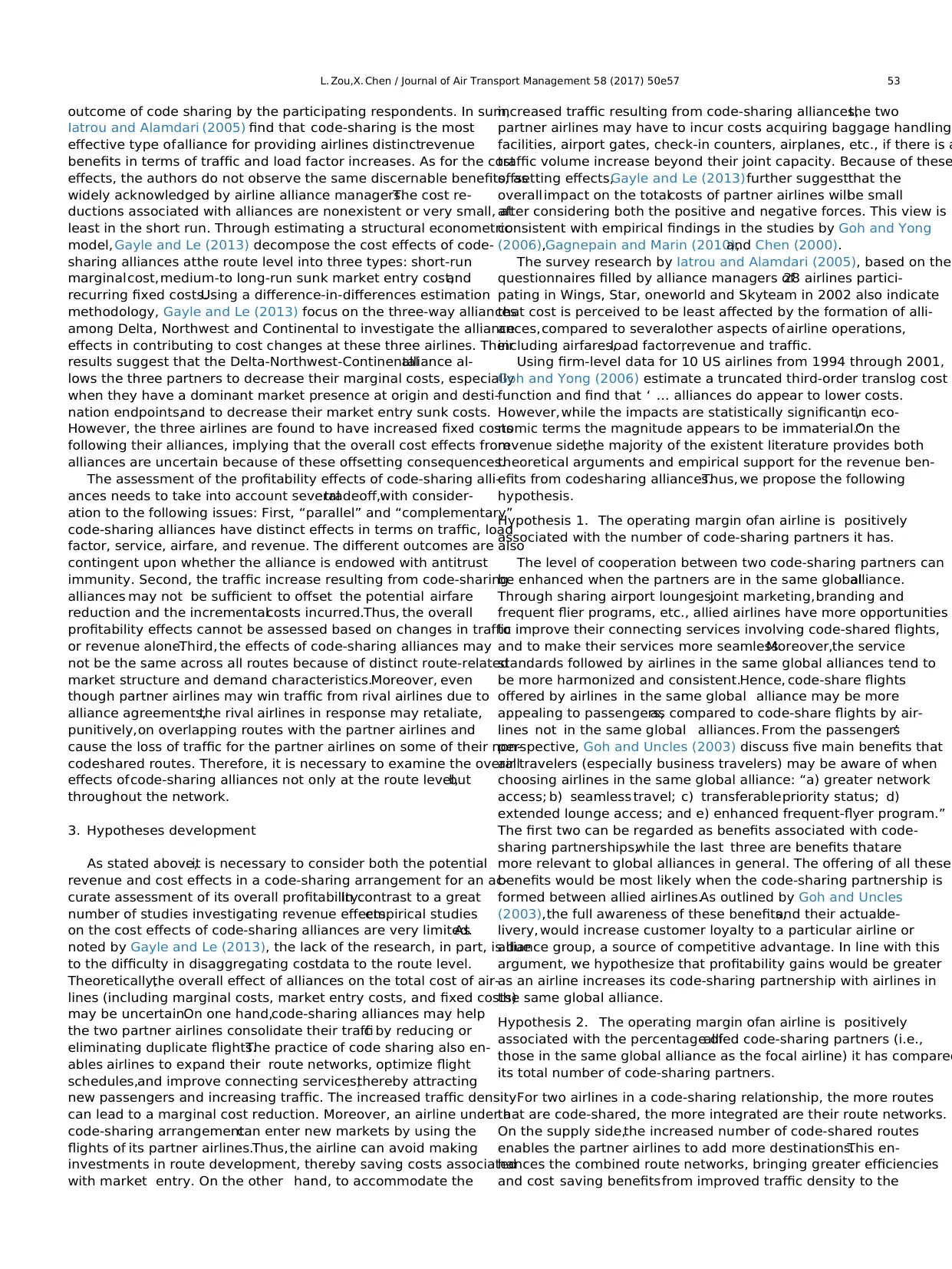

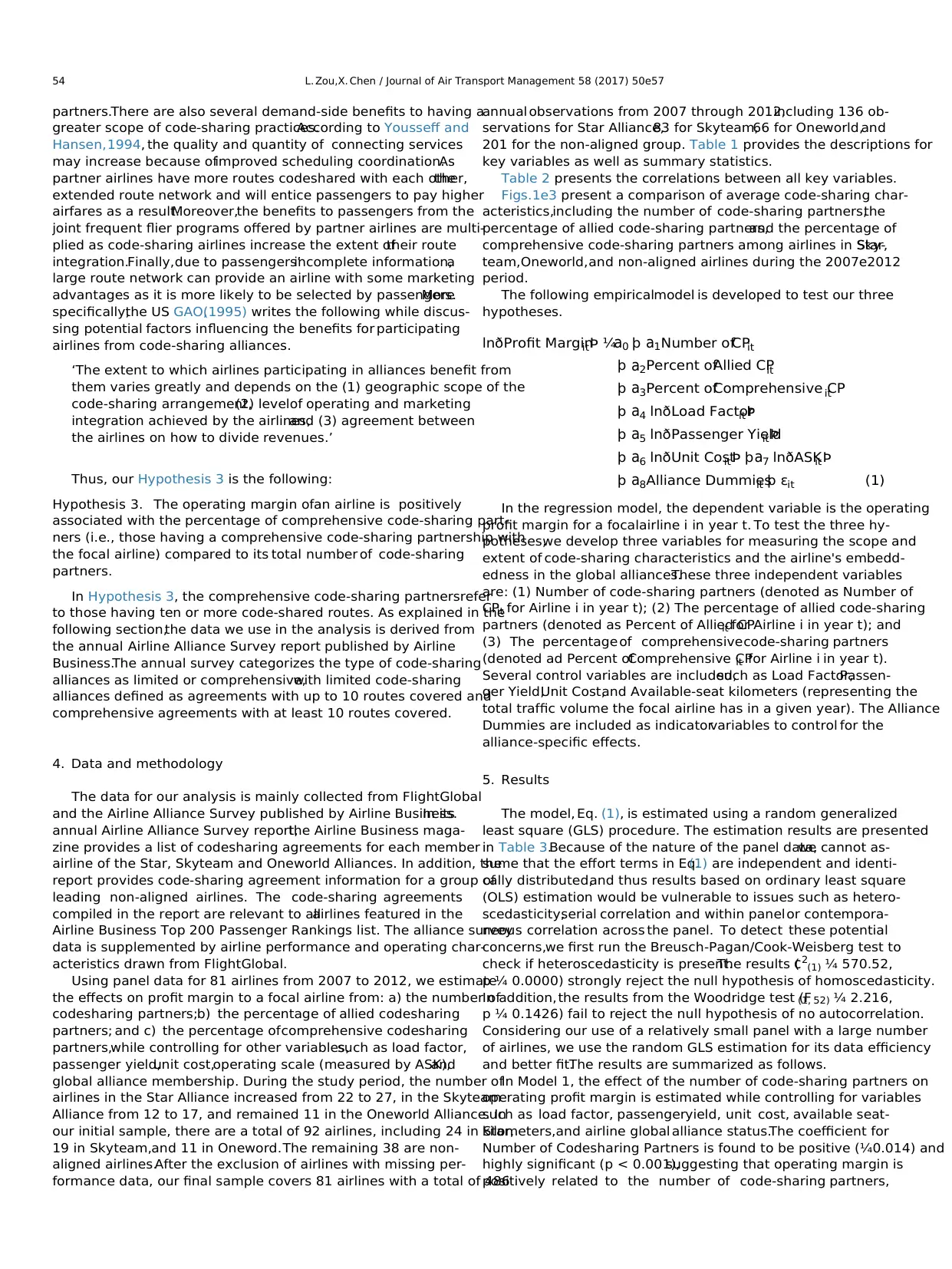

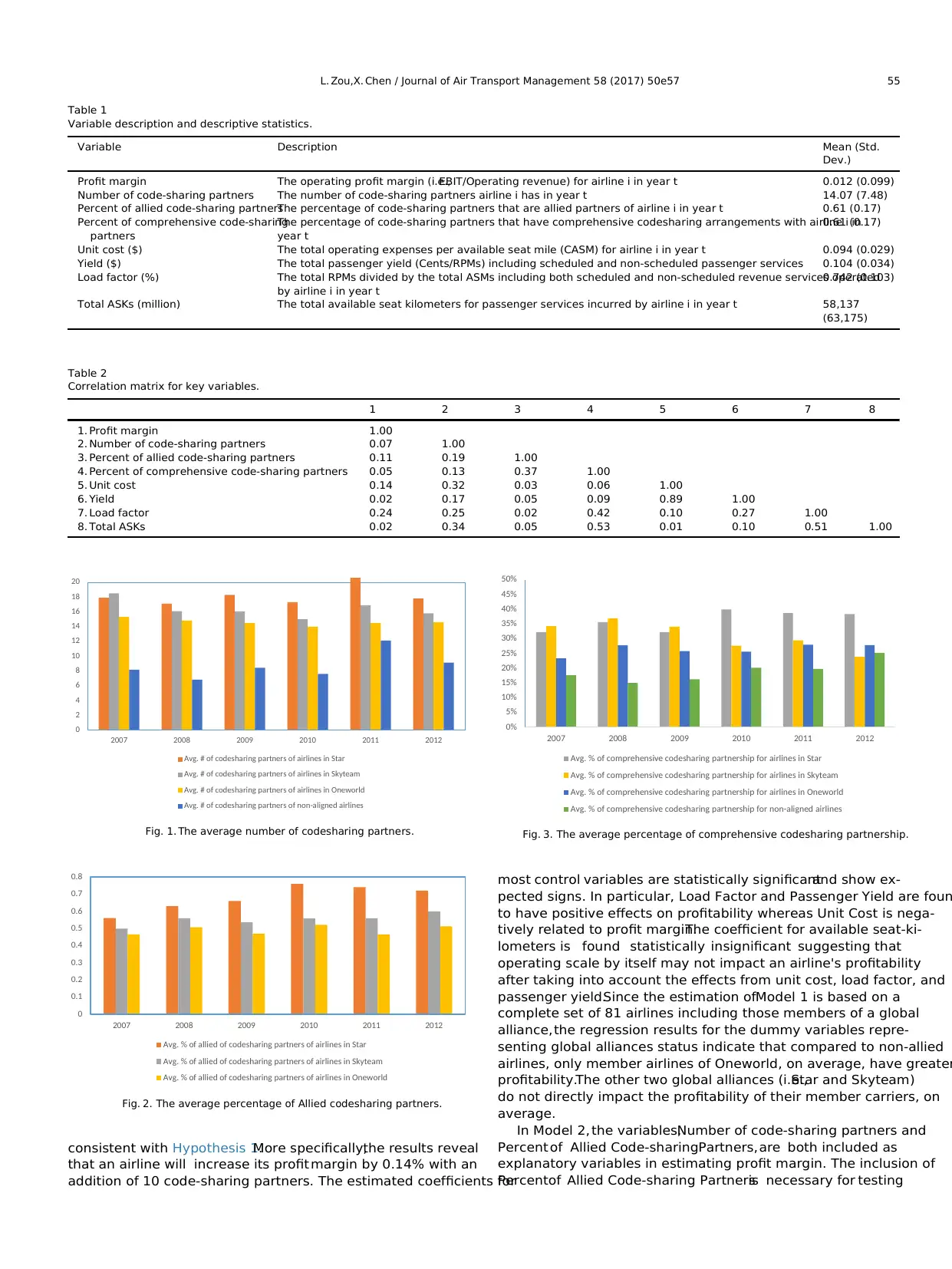

Figs.1e3 present a comparison of average code-sharing char-

acteristics,including the number of code-sharing partners,the

percentage of allied code-sharing partners,and the percentage of

comprehensive code-sharing partners among airlines in Star,Sky-

team,Oneworld,and non-aligned airlines during the 2007e2012

period.

The following empiricalmodel is developed to test our three

hypotheses.

lnðProfit Marginit Þ ¼a0 þ a1 Number ofCPit

þ a2 Percent ofAllied CPit

þ a3 Percent ofComprehensive CPit

þ a4 lnðLoad Factorit Þ

þ a5 lnðPassenger Yieldit Þ

þ a6 lnðUnit Costit Þ þ a7 lnðASKit Þ

þ a8 Alliance Dummiesit þ εit (1)

In the regression model, the dependent variable is the operating

profit margin for a focalairline i in year t. To test the three hy-

potheses,we develop three variables for measuring the scope and

extent of code-sharing characteristics and the airline's embedd-

edness in the global alliances.These three independent variables

are: (1) Number of code-sharing partners (denoted as Number of

CPit for Airline i in year t); (2) The percentage of allied code-sharing

partners (denoted as Percent of Allied CPit for Airline i in year t); and

(3) The percentage of comprehensivecode-sharing partners

(denoted ad Percent ofComprehensive CPit for Airline i in year t).

Several control variables are included,such as Load Factor,Passen-

ger Yield,Unit Cost,and Available-seat kilometers (representing the

total traffic volume the focal airline has in a given year). The Alliance

Dummies are included as indicatorvariables to control for the

alliance-specific effects.

5. Results

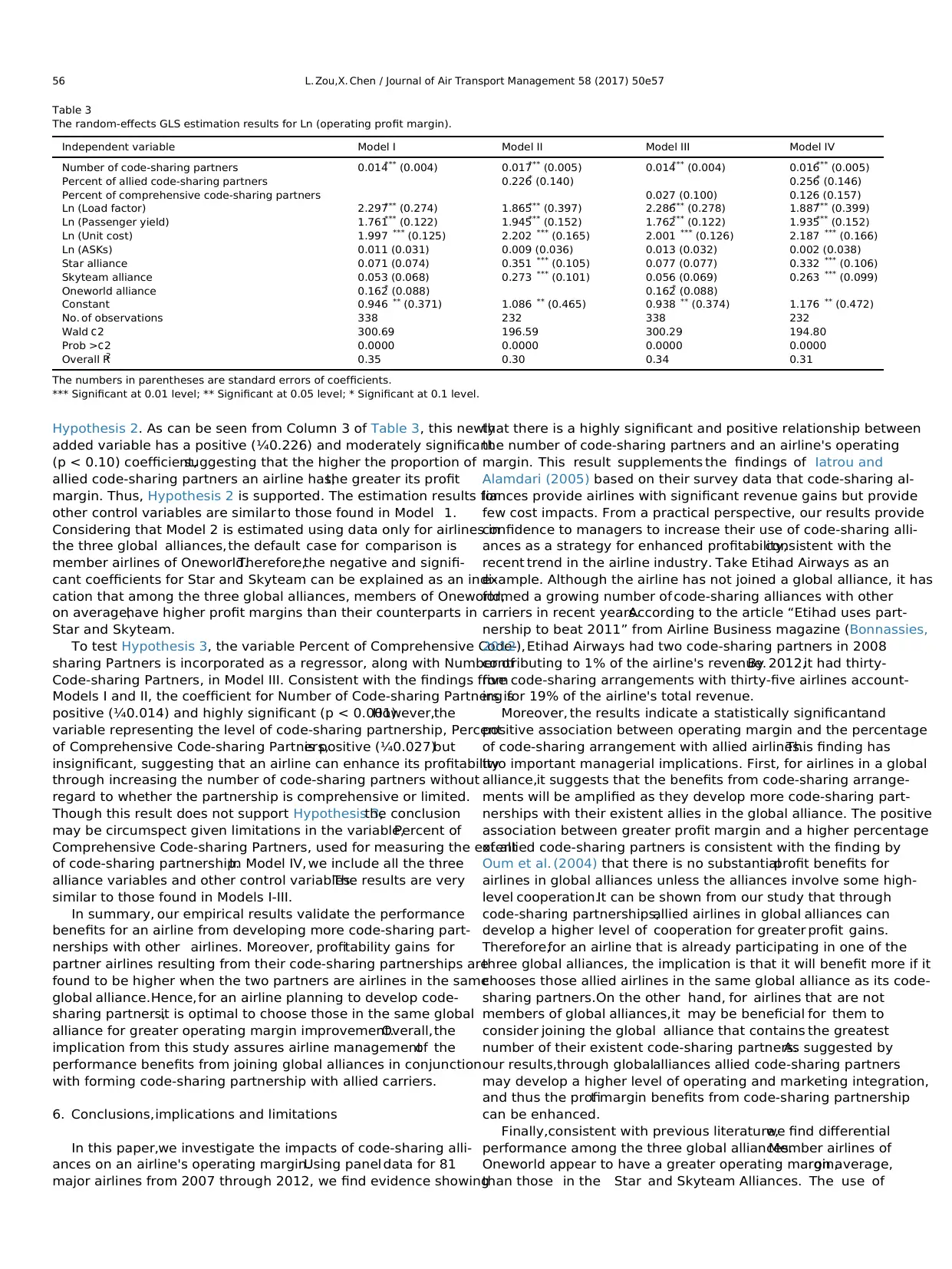

The model, Eq. (1), is estimated using a random generalized

least square (GLS) procedure. The estimation results are presented

in Table 3.Because of the nature of the panel data,we cannot as-

sume that the effort terms in Eq.(1) are independent and identi-

cally distributed,and thus results based on ordinary least square

(OLS) estimation would be vulnerable to issues such as hetero-

scedasticity,serial correlation and within panelor contempora-

neous correlation across the panel. To detect these potential

concerns,we first run the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test to

check if heteroscedasticity is present.The results (c 2(1) ¼ 570.52,

p ¼ 0.0000) strongly reject the null hypothesis of homoscedasticity.

In addition,the results from the Woodridge test (F(1, 52) ¼ 2.216,

p ¼ 0.1426) fail to reject the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation.

Considering our use of a relatively small panel with a large number

of airlines, we use the random GLS estimation for its data efficiency

and better fit.The results are summarized as follows.

In Model 1, the effect of the number of code-sharing partners on

operating profit margin is estimated while controlling for variables

such as load factor, passengeryield, unit cost, available seat-

kilometers,and airline global alliance status.The coefficient for

Number of Codesharing Partners is found to be positive (¼0.014) and

highly significant (p < 0.001),suggesting that operating margin is

positively related to the number of code-sharing partners,

L. Zou,X. Chen / Journal of Air Transport Management 58 (2017) 50e5754

greater scope of code-sharing practices.According to Yousseff and

Hansen,1994, the quality and quantity of connecting services

may increase because ofimproved scheduling coordination.As

partner airlines have more routes codeshared with each other,the

extended route network and will entice passengers to pay higher

airfares as a result.Moreover,the benefits to passengers from the

joint frequent flier programs offered by partner airlines are multi-

plied as code-sharing airlines increase the extent oftheir route

integration.Finally,due to passengers’incomplete information,a

large route network can provide an airline with some marketing

advantages as it is more likely to be selected by passengers.More

specifically,the US GAO,(1995) writes the following while discus-

sing potential factors influencing the benefits for participating

airlines from code-sharing alliances.

‘The extent to which airlines participating in alliances benefit from

them varies greatly and depends on the (1) geographic scope of the

code-sharing arrangement,(2) levelof operating and marketing

integration achieved by the airlines,and (3) agreement between

the airlines on how to divide revenues.’

Thus, our Hypothesis 3 is the following:

Hypothesis 3. The operating margin ofan airline is positively

associated with the percentage of comprehensive code-sharing part-

ners (i.e., those having a comprehensive code-sharing partnership with

the focal airline) compared to its total number of code-sharing

partners.

In Hypothesis 3, the comprehensive code-sharing partnersrefer

to those having ten or more code-shared routes. As explained in the

following section,the data we use in the analysis is derived from

the annual Airline Alliance Survey report published by Airline

Business.The annual survey categorizes the type of code-sharing

alliances as limited or comprehensive,with limited code-sharing

alliances defined as agreements with up to 10 routes covered and

comprehensive agreements with at least 10 routes covered.

4. Data and methodology

The data for our analysis is mainly collected from FlightGlobal

and the Airline Alliance Survey published by Airline Business.In its

annual Airline Alliance Survey report,the Airline Business maga-

zine provides a list of codesharing agreements for each member

airline of the Star, Skyteam and Oneworld Alliances. In addition, the

report provides code-sharing agreement information for a group of

leading non-aligned airlines. The code-sharing agreements

compiled in the report are relevant to allairlines featured in the

Airline Business Top 200 Passenger Rankings list. The alliance survey

data is supplemented by airline performance and operating char-

acteristics drawn from FlightGlobal.

Using panel data for 81 airlines from 2007 to 2012, we estimate

the effects on profit margin to a focal airline from: a) the number of

codesharing partners;b) the percentage of allied codesharing

partners; and c) the percentage ofcomprehensive codesharing

partners,while controlling for other variables,such as load factor,

passenger yield,unit cost,operating scale (measured by ASK),and

global alliance membership. During the study period, the number of

airlines in the Star Alliance increased from 22 to 27, in the Skyteam

Alliance from 12 to 17, and remained 11 in the Oneworld Alliance. In

our initial sample, there are a total of 92 airlines, including 24 in Star,

19 in Skyteam,and 11 in Oneword.The remaining 38 are non-

aligned airlines.After the exclusion of airlines with missing per-

formance data, our final sample covers 81 airlines with a total of 486

annual observations from 2007 through 2012,including 136 ob-

servations for Star Alliance,83 for Skyteam,66 for Oneworld,and

201 for the non-aligned group. Table 1 provides the descriptions for

key variables as well as summary statistics.

Table 2 presents the correlations between all key variables.

Figs.1e3 present a comparison of average code-sharing char-

acteristics,including the number of code-sharing partners,the

percentage of allied code-sharing partners,and the percentage of

comprehensive code-sharing partners among airlines in Star,Sky-

team,Oneworld,and non-aligned airlines during the 2007e2012

period.

The following empiricalmodel is developed to test our three

hypotheses.

lnðProfit Marginit Þ ¼a0 þ a1 Number ofCPit

þ a2 Percent ofAllied CPit

þ a3 Percent ofComprehensive CPit

þ a4 lnðLoad Factorit Þ

þ a5 lnðPassenger Yieldit Þ

þ a6 lnðUnit Costit Þ þ a7 lnðASKit Þ

þ a8 Alliance Dummiesit þ εit (1)

In the regression model, the dependent variable is the operating

profit margin for a focalairline i in year t. To test the three hy-

potheses,we develop three variables for measuring the scope and

extent of code-sharing characteristics and the airline's embedd-

edness in the global alliances.These three independent variables

are: (1) Number of code-sharing partners (denoted as Number of

CPit for Airline i in year t); (2) The percentage of allied code-sharing

partners (denoted as Percent of Allied CPit for Airline i in year t); and

(3) The percentage of comprehensivecode-sharing partners

(denoted ad Percent ofComprehensive CPit for Airline i in year t).

Several control variables are included,such as Load Factor,Passen-

ger Yield,Unit Cost,and Available-seat kilometers (representing the

total traffic volume the focal airline has in a given year). The Alliance