Analysis of Priming on Abstract Object Recognition Experiment

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/03

|13

|2668

|476

Report

AI Summary

This report details an experiment investigating the effects of priming on abstract object recognition. Participants were presented with abstract objects under fast and slow priming conditions, and their reaction times were measured. The study aimed to determine whether action representations influence object detection in the early stages of visual processing. The results indicated that priming affected object detection, with a significant positive correlation found between reaction times in both fast and slow priming conditions. However, the study found no significant difference in reaction times between the two priming stimuli. The experiment also explored the influence of the visual stimuli and their effects on the recognition of abstract objects. The research supports the idea that object recognition involves both visual analysis and the activation of stored visual representations, and that action representations play a crucial role in this process, influencing the speed and accuracy of object identification. The report includes descriptive and inferential statistical analysis of the collected data, discusses the findings in relation to existing literature on object recognition, and highlights the importance of understanding the cognitive processes involved in perception.

Priming on Abstract Object Recognition – An

Experiment on Time of Reaction

Experiment on Time of Reaction

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Introduction

Action and perception are considered classical as different functional and neurological

mechanisms. However, recent studies that use an action planning paradigm have defied this

perception and demonstrated that narratives can facilitate the recognition of objects (Chilisa,

2011). The objective of the research was to resolve whether representations of the action affect

object detection at the beginning of the visual process. The moment of activation of the

underlying brain for this purpose was studied at the time of the description of the object. The

subjects were presented with objects manipulated sequentially to describe in slow priming mode.

In fast simulating mode, the participants performed similar actions, while in the intransigent

mode different actions were performed. The objects were shown as an abstract image or a word

to test the effects of the main mode on the main operations. A priming effect was found

recognizing shapes or patterns after selecting image primers. The results suggest that the primer

affects the detection of objects by fast and slow signal curves, but, there was no significance in

the time difference for the fast process and slow process, when it was activated with visual

stimuli.

It is generally accepted that the detection of a object visually, depends largely on the

analysis of information perceived visually, and on the active realization of representations of

stored visual objects (Barsalou, 2008). However, recent studies show that the detection of

manipulated objects includes visual representations, and also initializes actions in the functional

system of the brain (Binder, Desai, Graves, & Conant, 2009). Behavioral studies using a start-of-

action paradigm, as described below, have shown that action implementation makes the

recognition of objects possible, and thus play a pivotal role in recognizing objects visually

(Gupta, Kembhavi, & Davis, 2009). The purpose of this study was to describe the influence of

Action and perception are considered classical as different functional and neurological

mechanisms. However, recent studies that use an action planning paradigm have defied this

perception and demonstrated that narratives can facilitate the recognition of objects (Chilisa,

2011). The objective of the research was to resolve whether representations of the action affect

object detection at the beginning of the visual process. The moment of activation of the

underlying brain for this purpose was studied at the time of the description of the object. The

subjects were presented with objects manipulated sequentially to describe in slow priming mode.

In fast simulating mode, the participants performed similar actions, while in the intransigent

mode different actions were performed. The objects were shown as an abstract image or a word

to test the effects of the main mode on the main operations. A priming effect was found

recognizing shapes or patterns after selecting image primers. The results suggest that the primer

affects the detection of objects by fast and slow signal curves, but, there was no significance in

the time difference for the fast process and slow process, when it was activated with visual

stimuli.

It is generally accepted that the detection of a object visually, depends largely on the

analysis of information perceived visually, and on the active realization of representations of

stored visual objects (Barsalou, 2008). However, recent studies show that the detection of

manipulated objects includes visual representations, and also initializes actions in the functional

system of the brain (Binder, Desai, Graves, & Conant, 2009). Behavioral studies using a start-of-

action paradigm, as described below, have shown that action implementation makes the

recognition of objects possible, and thus play a pivotal role in recognizing objects visually

(Gupta, Kembhavi, & Davis, 2009). The purpose of this study was to describe the influence of

diagrams on the perception of objects taking advantage of the high temporal dissolution of

temporary recordings. In particular, the scholar wanted to determine whether the action

representations had already influenced the recognition of objects in a first editing window, that

is, a few seconds after the start of the stimulus, which is temporarily extended to the levels.

The main effect of action on object recognition is the question of conventional cognitive

models for recognition of objects and control of actions, which offers two different functional

and neurological forms for targeted actions stimulate (Milner, & Goodale, 2008). Extension of

the primary visual cortex of the brain stimulates visual recognition of objects. However, dorsal

visual flow, which also comes from the primary visual cortex, continues to show superior

computation of visual cognition information (Silver, & Kastner, 2009). In this context, object-

oriented recognition and object-oriented action are considered fundamentally different processes

according to the different computational principles. The relative detection of objects is slow and

depends on the construction of a deliberate visual perception (Haggard, 2008). On the other

hand, the preparation of the action sent through the object is fast and unconscious.

Given the evidence in the current study, the scholar scrutinized the effects of fast and

slow priming stimuli on description time for abstract subjects. It was hypothesized that speed of

abstract description for fast priming was greater than that of the slow priming stimuli. The null

hypothesis was constructed assuming that there was no difference in speed of abstract narration

due to the two stimuli. The scholar also hypothesized that there strong correlation between these

two effects, signifying the consistency of the human brain. These claims were tested at 5% level

of significance to inculcate previous results of various literatures.

temporary recordings. In particular, the scholar wanted to determine whether the action

representations had already influenced the recognition of objects in a first editing window, that

is, a few seconds after the start of the stimulus, which is temporarily extended to the levels.

The main effect of action on object recognition is the question of conventional cognitive

models for recognition of objects and control of actions, which offers two different functional

and neurological forms for targeted actions stimulate (Milner, & Goodale, 2008). Extension of

the primary visual cortex of the brain stimulates visual recognition of objects. However, dorsal

visual flow, which also comes from the primary visual cortex, continues to show superior

computation of visual cognition information (Silver, & Kastner, 2009). In this context, object-

oriented recognition and object-oriented action are considered fundamentally different processes

according to the different computational principles. The relative detection of objects is slow and

depends on the construction of a deliberate visual perception (Haggard, 2008). On the other

hand, the preparation of the action sent through the object is fast and unconscious.

Given the evidence in the current study, the scholar scrutinized the effects of fast and

slow priming stimuli on description time for abstract subjects. It was hypothesized that speed of

abstract description for fast priming was greater than that of the slow priming stimuli. The null

hypothesis was constructed assuming that there was no difference in speed of abstract narration

due to the two stimuli. The scholar also hypothesized that there strong correlation between these

two effects, signifying the consistency of the human brain. These claims were tested at 5% level

of significance to inculcate previous results of various literatures.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

One hundred twenty four healthy volunteers (MED = 26 years, Range = 18 – 29 years)

with normal vision or corrected normal eyesight were involved in the experiment. The

participants signed the consent form for the experiment and were briefed by the scholar about the

purpose of the research, and were informed that no payment would be provided in appropriation

of their service. The experience was conducted according to the ethical standards prevailing in

the university administration and approved by the university ethics committee. The stimuli

consisted of artificial family objects that were visually presented on a giant screen. Key object

and target pairs were chosen for the main objects and objectives to be associated with a typical

similar action, whereas the typical actions did not coincide with the other half. Since each main

object was associated with the same number of simultaneous goals, hence, possible repetition

effects may also affect congruent and inadequate states.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

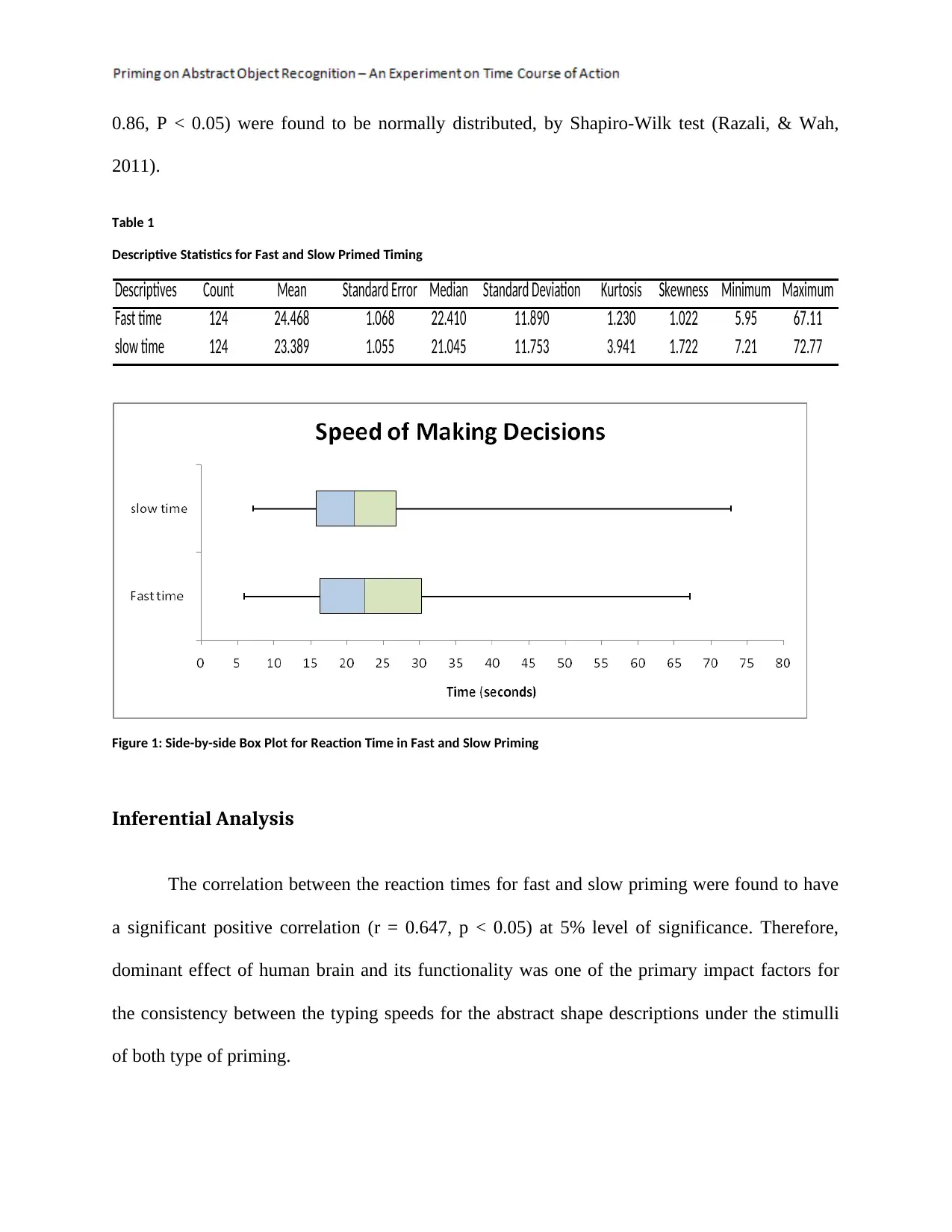

The average reaction time to describe abstract objects for positively primed situation (M

= 24.47, SD = 11.89) was slightly greater than that of the slow primed reaction time (M = 23.39,

SD = 11.75). Due to presence of few outlier reaction times positive skewness for both the

reaction times were observed. From the side-by-side box plot in Figure 1, it was identified that

Interquartile range of reaction timing for fast priming was larger than that of the slow primed

situation. Due to presence of outliers the skewness in slow priming was greater than fast priming.

But, abstract description timing for priming fast (W = 0.94, P < 0.05), and priming slow (W =

with normal vision or corrected normal eyesight were involved in the experiment. The

participants signed the consent form for the experiment and were briefed by the scholar about the

purpose of the research, and were informed that no payment would be provided in appropriation

of their service. The experience was conducted according to the ethical standards prevailing in

the university administration and approved by the university ethics committee. The stimuli

consisted of artificial family objects that were visually presented on a giant screen. Key object

and target pairs were chosen for the main objects and objectives to be associated with a typical

similar action, whereas the typical actions did not coincide with the other half. Since each main

object was associated with the same number of simultaneous goals, hence, possible repetition

effects may also affect congruent and inadequate states.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

The average reaction time to describe abstract objects for positively primed situation (M

= 24.47, SD = 11.89) was slightly greater than that of the slow primed reaction time (M = 23.39,

SD = 11.75). Due to presence of few outlier reaction times positive skewness for both the

reaction times were observed. From the side-by-side box plot in Figure 1, it was identified that

Interquartile range of reaction timing for fast priming was larger than that of the slow primed

situation. Due to presence of outliers the skewness in slow priming was greater than fast priming.

But, abstract description timing for priming fast (W = 0.94, P < 0.05), and priming slow (W =

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

0.86, P < 0.05) were found to be normally distributed, by Shapiro-Wilk test (Razali, & Wah,

2011).

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for Fast and Slow Primed Timing

Descriptives Count Mean Standard Error Median Standard Deviation Kurtosis Skewness Minimum Maximum

Fast time 124 24.468 1.068 22.410 11.890 1.230 1.022 5.95 67.11

slow time 124 23.389 1.055 21.045 11.753 3.941 1.722 7.21 72.77

Figure 1: Side-by-side Box Plot for Reaction Time in Fast and Slow Priming

Inferential Analysis

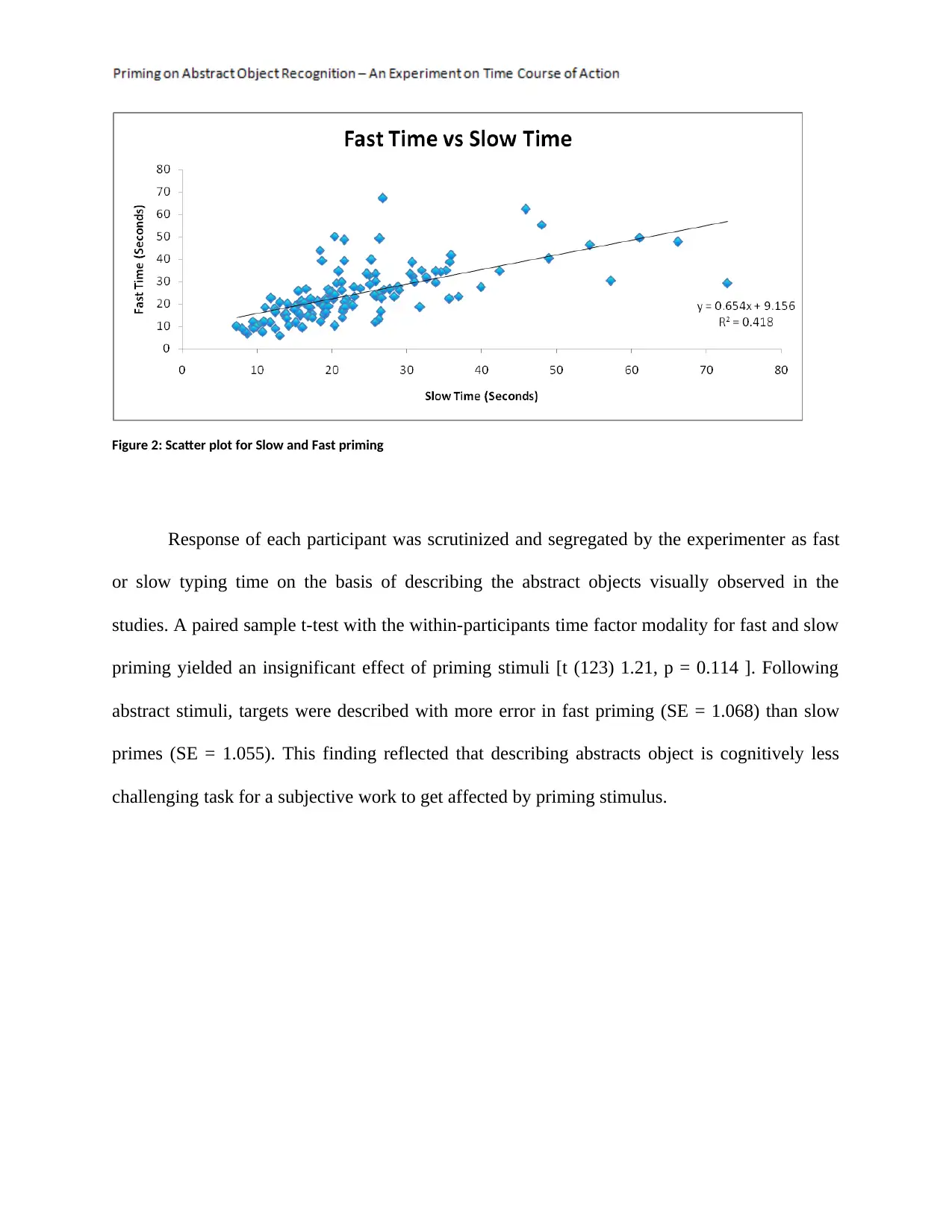

The correlation between the reaction times for fast and slow priming were found to have

a significant positive correlation (r = 0.647, p < 0.05) at 5% level of significance. Therefore,

dominant effect of human brain and its functionality was one of the primary impact factors for

the consistency between the typing speeds for the abstract shape descriptions under the stimulli

of both type of priming.

2011).

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for Fast and Slow Primed Timing

Descriptives Count Mean Standard Error Median Standard Deviation Kurtosis Skewness Minimum Maximum

Fast time 124 24.468 1.068 22.410 11.890 1.230 1.022 5.95 67.11

slow time 124 23.389 1.055 21.045 11.753 3.941 1.722 7.21 72.77

Figure 1: Side-by-side Box Plot for Reaction Time in Fast and Slow Priming

Inferential Analysis

The correlation between the reaction times for fast and slow priming were found to have

a significant positive correlation (r = 0.647, p < 0.05) at 5% level of significance. Therefore,

dominant effect of human brain and its functionality was one of the primary impact factors for

the consistency between the typing speeds for the abstract shape descriptions under the stimulli

of both type of priming.

Figure 2: Scatter plot for Slow and Fast priming

Response of each participant was scrutinized and segregated by the experimenter as fast

or slow typing time on the basis of describing the abstract objects visually observed in the

studies. A paired sample t-test with the within-participants time factor modality for fast and slow

priming yielded an insignificant effect of priming stimuli [t (123) 1.21, p = 0.114 ]. Following

abstract stimuli, targets were described with more error in fast priming (SE = 1.068) than slow

primes (SE = 1.055). This finding reflected that describing abstracts object is cognitively less

challenging task for a subjective work to get affected by priming stimulus.

Response of each participant was scrutinized and segregated by the experimenter as fast

or slow typing time on the basis of describing the abstract objects visually observed in the

studies. A paired sample t-test with the within-participants time factor modality for fast and slow

priming yielded an insignificant effect of priming stimuli [t (123) 1.21, p = 0.114 ]. Following

abstract stimuli, targets were described with more error in fast priming (SE = 1.068) than slow

primes (SE = 1.055). This finding reflected that describing abstracts object is cognitively less

challenging task for a subjective work to get affected by priming stimulus.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Discussion

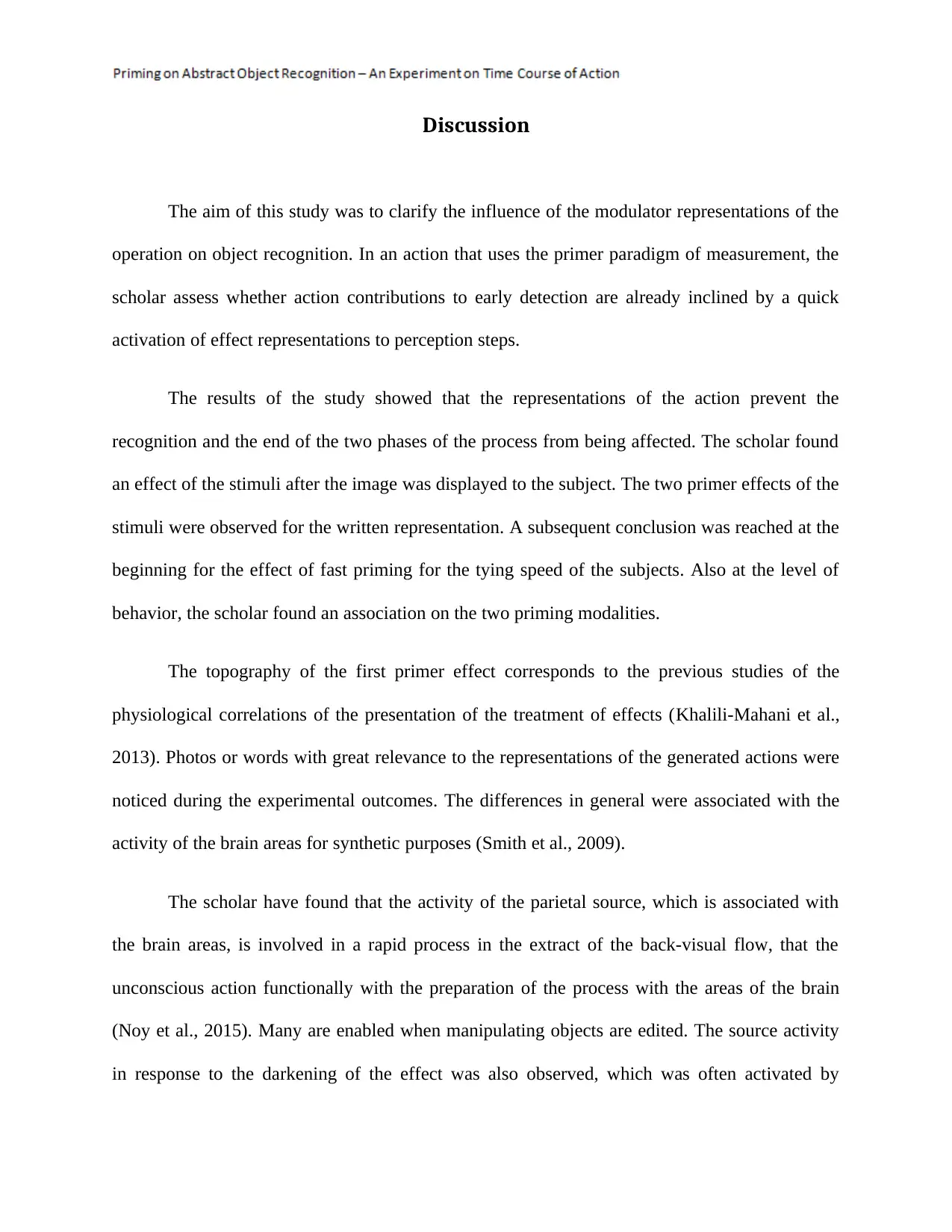

The aim of this study was to clarify the influence of the modulator representations of the

operation on object recognition. In an action that uses the primer paradigm of measurement, the

scholar assess whether action contributions to early detection are already inclined by a quick

activation of effect representations to perception steps.

The results of the study showed that the representations of the action prevent the

recognition and the end of the two phases of the process from being affected. The scholar found

an effect of the stimuli after the image was displayed to the subject. The two primer effects of the

stimuli were observed for the written representation. A subsequent conclusion was reached at the

beginning for the effect of fast priming for the tying speed of the subjects. Also at the level of

behavior, the scholar found an association on the two priming modalities.

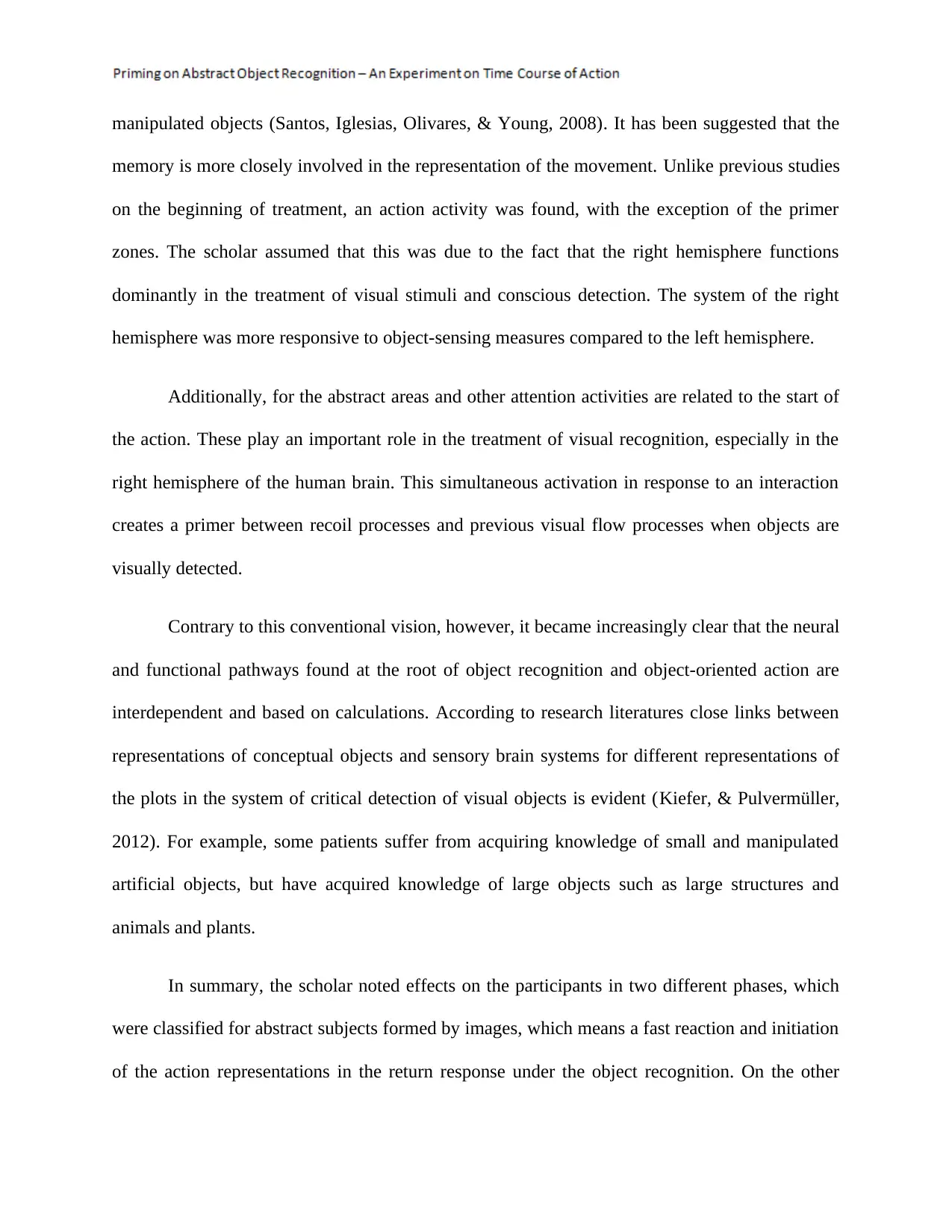

The topography of the first primer effect corresponds to the previous studies of the

physiological correlations of the presentation of the treatment of effects (Khalili-Mahani et al.,

2013). Photos or words with great relevance to the representations of the generated actions were

noticed during the experimental outcomes. The differences in general were associated with the

activity of the brain areas for synthetic purposes (Smith et al., 2009).

The scholar have found that the activity of the parietal source, which is associated with

the brain areas, is involved in a rapid process in the extract of the back-visual flow, that the

unconscious action functionally with the preparation of the process with the areas of the brain

(Noy et al., 2015). Many are enabled when manipulating objects are edited. The source activity

in response to the darkening of the effect was also observed, which was often activated by

The aim of this study was to clarify the influence of the modulator representations of the

operation on object recognition. In an action that uses the primer paradigm of measurement, the

scholar assess whether action contributions to early detection are already inclined by a quick

activation of effect representations to perception steps.

The results of the study showed that the representations of the action prevent the

recognition and the end of the two phases of the process from being affected. The scholar found

an effect of the stimuli after the image was displayed to the subject. The two primer effects of the

stimuli were observed for the written representation. A subsequent conclusion was reached at the

beginning for the effect of fast priming for the tying speed of the subjects. Also at the level of

behavior, the scholar found an association on the two priming modalities.

The topography of the first primer effect corresponds to the previous studies of the

physiological correlations of the presentation of the treatment of effects (Khalili-Mahani et al.,

2013). Photos or words with great relevance to the representations of the generated actions were

noticed during the experimental outcomes. The differences in general were associated with the

activity of the brain areas for synthetic purposes (Smith et al., 2009).

The scholar have found that the activity of the parietal source, which is associated with

the brain areas, is involved in a rapid process in the extract of the back-visual flow, that the

unconscious action functionally with the preparation of the process with the areas of the brain

(Noy et al., 2015). Many are enabled when manipulating objects are edited. The source activity

in response to the darkening of the effect was also observed, which was often activated by

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

manipulated objects (Santos, Iglesias, Olivares, & Young, 2008). It has been suggested that the

memory is more closely involved in the representation of the movement. Unlike previous studies

on the beginning of treatment, an action activity was found, with the exception of the primer

zones. The scholar assumed that this was due to the fact that the right hemisphere functions

dominantly in the treatment of visual stimuli and conscious detection. The system of the right

hemisphere was more responsive to object-sensing measures compared to the left hemisphere.

Additionally, for the abstract areas and other attention activities are related to the start of

the action. These play an important role in the treatment of visual recognition, especially in the

right hemisphere of the human brain. This simultaneous activation in response to an interaction

creates a primer between recoil processes and previous visual flow processes when objects are

visually detected.

Contrary to this conventional vision, however, it became increasingly clear that the neural

and functional pathways found at the root of object recognition and object-oriented action are

interdependent and based on calculations. According to research literatures close links between

representations of conceptual objects and sensory brain systems for different representations of

the plots in the system of critical detection of visual objects is evident (Kiefer, & Pulvermüller,

2012). For example, some patients suffer from acquiring knowledge of small and manipulated

artificial objects, but have acquired knowledge of large objects such as large structures and

animals and plants.

In summary, the scholar noted effects on the participants in two different phases, which

were classified for abstract subjects formed by images, which means a fast reaction and initiation

of the action representations in the return response under the object recognition. On the other

memory is more closely involved in the representation of the movement. Unlike previous studies

on the beginning of treatment, an action activity was found, with the exception of the primer

zones. The scholar assumed that this was due to the fact that the right hemisphere functions

dominantly in the treatment of visual stimuli and conscious detection. The system of the right

hemisphere was more responsive to object-sensing measures compared to the left hemisphere.

Additionally, for the abstract areas and other attention activities are related to the start of

the action. These play an important role in the treatment of visual recognition, especially in the

right hemisphere of the human brain. This simultaneous activation in response to an interaction

creates a primer between recoil processes and previous visual flow processes when objects are

visually detected.

Contrary to this conventional vision, however, it became increasingly clear that the neural

and functional pathways found at the root of object recognition and object-oriented action are

interdependent and based on calculations. According to research literatures close links between

representations of conceptual objects and sensory brain systems for different representations of

the plots in the system of critical detection of visual objects is evident (Kiefer, & Pulvermüller,

2012). For example, some patients suffer from acquiring knowledge of small and manipulated

artificial objects, but have acquired knowledge of large objects such as large structures and

animals and plants.

In summary, the scholar noted effects on the participants in two different phases, which

were classified for abstract subjects formed by images, which means a fast reaction and initiation

of the action representations in the return response under the object recognition. On the other

hand, the initial effect of successive actions for the primary stimuli of abstract images has been

achieved. This is probably due to the fact that this effect comes from the regions of the brain and

reflects the integration of the semantic traits into a coherent concept, regardless of the primary

modality. Recent results show that priming operations can quickly and slowly affect the

recording of objects (Barsalou, 2008). It affects the fast processes induced by the first stimuli

with images, but it can also adapt in the slow abstract image integration process that is caused

due to functionality of subconscious human brain.

achieved. This is probably due to the fact that this effect comes from the regions of the brain and

reflects the integration of the semantic traits into a coherent concept, regardless of the primary

modality. Recent results show that priming operations can quickly and slowly affect the

recording of objects (Barsalou, 2008). It affects the fast processes induced by the first stimuli

with images, but it can also adapt in the slow abstract image integration process that is caused

due to functionality of subconscious human brain.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Reference

Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 59, 617-645.

Binder, J. R., Desai, R. H., Graves, W. W., & Conant, L. L. (2009). Where is the semantic

system? A critical review and meta-analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies.

Cerebral Cortex, 19(12), 2767-2796.

Chilisa, B. (2011). Indigenous research methodologies. Sage Publications.

Gupta, A., Kembhavi, A., & Davis, L. S. (2009). Observing human-object interactions: Using

spatial and functional compatibility for recognition. IEEE Transactions on Pattern

Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 31(10), 1775-1789.

Haggard, P. (2008). Human volition: towards a neuroscience of will. Nature Reviews

Neuroscience, 9(12), 934.

Khalili-Mahani, N., Chang, C., van Osch, M. J., Veer, I. M., van Buchem, M. A., Dahan, A., ...

& Rombouts, S. A. (2013). The impact of “physiological correction” on functional

connectivity analysis of pharmacological resting state fMRI. Neuroimage, 65, 499-510.

Kiefer, M., & Pulvermüller, F. (2012). Conceptual representations in mind and brain: theoretical

developments, current evidence and future directions. cortex, 48(7), 805-825.

Milner, A. D., & Goodale, M. A. (2008). Two visual systems re-viewed. Neuropsychologia,

46(3), 774-785.

Noy, N., Bickel, S., Zion-Golumbic, E., Harel, M., Golan, T., Davidesco, I., ... & Mehta, A. D.

(2015). Ignition’s glow: Ultra-fast spread of global cortical activity accompanying local

Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 59, 617-645.

Binder, J. R., Desai, R. H., Graves, W. W., & Conant, L. L. (2009). Where is the semantic

system? A critical review and meta-analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies.

Cerebral Cortex, 19(12), 2767-2796.

Chilisa, B. (2011). Indigenous research methodologies. Sage Publications.

Gupta, A., Kembhavi, A., & Davis, L. S. (2009). Observing human-object interactions: Using

spatial and functional compatibility for recognition. IEEE Transactions on Pattern

Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 31(10), 1775-1789.

Haggard, P. (2008). Human volition: towards a neuroscience of will. Nature Reviews

Neuroscience, 9(12), 934.

Khalili-Mahani, N., Chang, C., van Osch, M. J., Veer, I. M., van Buchem, M. A., Dahan, A., ...

& Rombouts, S. A. (2013). The impact of “physiological correction” on functional

connectivity analysis of pharmacological resting state fMRI. Neuroimage, 65, 499-510.

Kiefer, M., & Pulvermüller, F. (2012). Conceptual representations in mind and brain: theoretical

developments, current evidence and future directions. cortex, 48(7), 805-825.

Milner, A. D., & Goodale, M. A. (2008). Two visual systems re-viewed. Neuropsychologia,

46(3), 774-785.

Noy, N., Bickel, S., Zion-Golumbic, E., Harel, M., Golan, T., Davidesco, I., ... & Mehta, A. D.

(2015). Ignition’s glow: Ultra-fast spread of global cortical activity accompanying local

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

“ignitions” in visual cortex during conscious visual perception. Consciousness and

cognition, 35, 206-224.

Razali, N. M., & Wah, Y. B. (2011). Power comparisons of shapiro-wilk, kolmogorov-smirnov,

lilliefors and anderson-darling tests. Journal of statistical modeling and analytics, 2(1),

21-33.

Santos, I. M., Iglesias, J., Olivares, E. I., & Young, A. W. (2008). Differential effects of object-

based attention on evoked potentials to fearful and disgusted faces. Neuropsychologia,

46(5), 1468-1479.

Silver, M. A., & Kastner, S. (2009). Topographic maps in human frontal and parietal cortex.

Trends in cognitive sciences, 13(11), 488-495.

Smith, S. M., Fox, P. T., Miller, K. L., Glahn, D. C., Fox, P. M., Mackay, C. E., ... & Beckmann,

C. F. (2009). Correspondence of the brain's functional architecture during activation and

rest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(31), 13040-13045.

cognition, 35, 206-224.

Razali, N. M., & Wah, Y. B. (2011). Power comparisons of shapiro-wilk, kolmogorov-smirnov,

lilliefors and anderson-darling tests. Journal of statistical modeling and analytics, 2(1),

21-33.

Santos, I. M., Iglesias, J., Olivares, E. I., & Young, A. W. (2008). Differential effects of object-

based attention on evoked potentials to fearful and disgusted faces. Neuropsychologia,

46(5), 1468-1479.

Silver, M. A., & Kastner, S. (2009). Topographic maps in human frontal and parietal cortex.

Trends in cognitive sciences, 13(11), 488-495.

Smith, S. M., Fox, P. T., Miller, K. L., Glahn, D. C., Fox, P. M., Mackay, C. E., ... & Beckmann,

C. F. (2009). Correspondence of the brain's functional architecture during activation and

rest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(31), 13040-13045.

Appendix

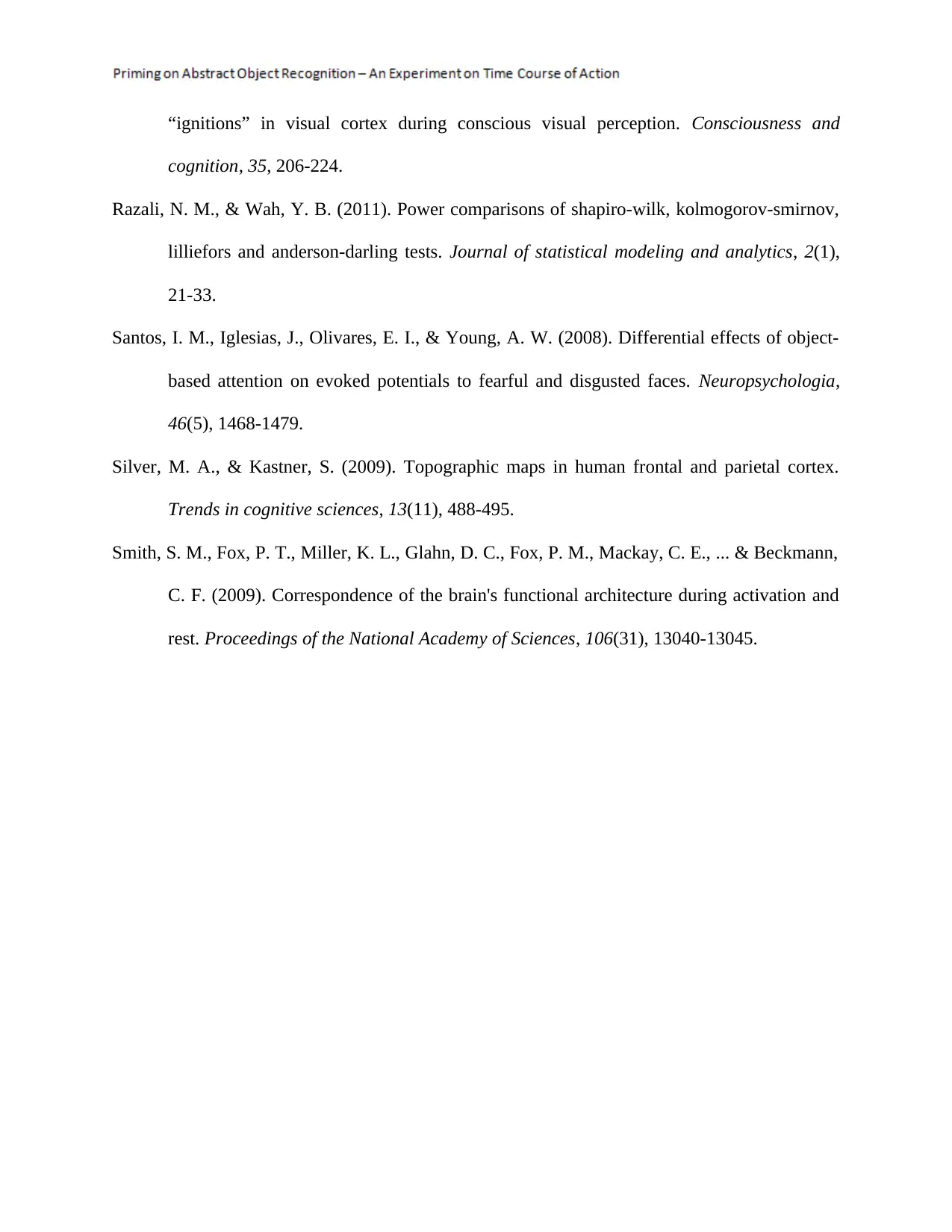

Table 2

Paired t-test Table

Fast time slow time

Mean 24.468 23.389

Variance 141.376 138.126

Observations 124 124

Pearson Correlation 0.647

Hypothesized Mean Difference 0

df 123

t Stat 1.210

P(T<=t) one-tail 0.114

t Critical one-tail 1.657

P(T<=t) two-tail 0.229

t Critical two-tail 1.979

Table 3

Tests of Normality

Kolmogorov-Smirnova Shapiro-Wilk

Statistic df Sig. Statistic df Sig.

Fast time .102 124 .003 .938 124 .000

slow time .141 124 .000 .862 124 .000

a. Lilliefors Significance Correction

Table 2

Paired t-test Table

Fast time slow time

Mean 24.468 23.389

Variance 141.376 138.126

Observations 124 124

Pearson Correlation 0.647

Hypothesized Mean Difference 0

df 123

t Stat 1.210

P(T<=t) one-tail 0.114

t Critical one-tail 1.657

P(T<=t) two-tail 0.229

t Critical two-tail 1.979

Table 3

Tests of Normality

Kolmogorov-Smirnova Shapiro-Wilk

Statistic df Sig. Statistic df Sig.

Fast time .102 124 .003 .938 124 .000

slow time .141 124 .000 .862 124 .000

a. Lilliefors Significance Correction

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 13

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.