COMP640 Forecasting: Student Outcomes and Technology's Impact

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/09

|38

|23492

|17

Project

AI Summary

This capstone project, submitted to the University of the Potomac for COMP640 – Forecasting and Management Technology, investigates the multifaceted impact of technological changes on students. The project begins by outlining the problem of increased technology dependency, referencing literature that highlights both the benefits, such as enhanced learning through tools like calculators, and potential drawbacks of technology overuse in education. The research includes a literature review, methodology, findings, and conclusions, with the student acknowledging the use of various technologies in the classroom to capture attention and increase achievement levels. The project aims to determine the effects of technology, addressing the research question through a well-defined hypothesis, establishing the purpose and significance of the study, and providing a structured organization. The project also includes a table of contents, acronyms, and a list of references, showcasing a comprehensive approach to the topic of technology and its influence on students in a higher education setting. The project examines the effects of technology on students, and references to previous literature on the topic are made throughout the project.

American Economic Review 2018, 108(7): 1737–1772

https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161570

1737

* Hershbein: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 300 S Westnedge Avenue, Kalamazoo

49007, and IZA (email: hershbein@upjohn.org); Kahn: Yale School of Management, 165 Whitney Avenue, PO

Box 208200, New Haven, CT 06511, NBER, and IZA (email: lisa.kahn@yale.edu). This paper was accepted to

the AER under the guidance of Hilary Hoynes, Coeditor. We are grateful to Jason Abaluck, Joe Altonji, Dav

Autor, Tim Bartik, David Berger, Nick Bloom, Jeff Clemens, David Deming, David Green, John Horton, Peter

Kuhn, Fabian Lange, Steve Malliaris, Adrien Matray, Alicia Sasser Modestino, Daniel Shoag, Henry Siu, Basit

Zafar, four anonymous referees, and seminar participants at the 2016 AEAs, the Atlanta Fed, Boston

Boston University, Brookings, Georgetown University, Harvard, the LSE, MIT, NBER Summer Institute (Macro

and Labor), Northwestern, Princeton, Rutgers, SOLE/EALE 2015 meetings, Trans Pacific Labor Seminar 2015,

University of British Columbia, University of Chicago, University of Illinois, University of Kansas, University of

Michigan, University of Notre Dame, University of Pennsylvania, University of Pittsburgh, University of South

Florida, and the WEAI 2016 meetings. We are especially indebted to Dan Restuccia, Jake Sherman, and Bled

for providing the Burning Glass data. Jing Cai provided excellent research assistance with CPS data. A previo

version of this paper was titled “Is College the New High School? Evidence from Vacancy Postings.”

† Go to https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161570 to visit the article page for additional materials and

disclosure statement(s).

Do Recessions Accelerate Routine-Biased Technological

Change? Evidence from Vacancy Postings†

By Brad Hershbein and Lisa B. Kahn*

We show that skill requirements in job vacancy postings differentially

increased in MSAs that were hit hard by the Great Recession, relative

to lesshard-hit areas. These increases persist through at least the

end of 2015 and are correlated with increases in capital investments,

both at the MSA andfirm levels. We also find that effects are most

pronounced in routine-cognitive occupations, which exhibit relative

wage growth as well. We argue that this evidence is consistent with

the restructuring of production toward routine-biased technologies

and the more-skilled workers that complement them, and that the

Great Recession accelerated this process. (JEL E24, E32, J24, J31,

J63, L23, O33)

The employment shift from occupations in the middle of the skill distribution

toward those in the tails is one of the most important trends in the US labor ma

ket over the last 30 years. Previous research makes the compelling case that a

mary driver of this job polarization isroutine-biased technological change (RBTC),

whereby new machine technologies and overseas labor substitute for middle-s

jobs in the United States and are in turn complementary to high-skill co

jobs.1 Until recently, RBTC had been thought to be a gradual, secular phenomen

However, a long theoretical literature, beginning with Schumpeter’s (1939) “c

ative destruction,” suggests adjustments to technological change may be more

sodic. In boom times, high opportunity costs, or frictions such as adjustment co

may inhibit resources from being reallocated optimally in the face of technolog

1See, for example, the seminal work of Autor, Levy, and Murnane (2003); Goos and Manning (2007); Auto

Katz, and Kearney (2008); and Autor and Dorn (2013).

https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161570

1737

* Hershbein: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 300 S Westnedge Avenue, Kalamazoo

49007, and IZA (email: hershbein@upjohn.org); Kahn: Yale School of Management, 165 Whitney Avenue, PO

Box 208200, New Haven, CT 06511, NBER, and IZA (email: lisa.kahn@yale.edu). This paper was accepted to

the AER under the guidance of Hilary Hoynes, Coeditor. We are grateful to Jason Abaluck, Joe Altonji, Dav

Autor, Tim Bartik, David Berger, Nick Bloom, Jeff Clemens, David Deming, David Green, John Horton, Peter

Kuhn, Fabian Lange, Steve Malliaris, Adrien Matray, Alicia Sasser Modestino, Daniel Shoag, Henry Siu, Basit

Zafar, four anonymous referees, and seminar participants at the 2016 AEAs, the Atlanta Fed, Boston

Boston University, Brookings, Georgetown University, Harvard, the LSE, MIT, NBER Summer Institute (Macro

and Labor), Northwestern, Princeton, Rutgers, SOLE/EALE 2015 meetings, Trans Pacific Labor Seminar 2015,

University of British Columbia, University of Chicago, University of Illinois, University of Kansas, University of

Michigan, University of Notre Dame, University of Pennsylvania, University of Pittsburgh, University of South

Florida, and the WEAI 2016 meetings. We are especially indebted to Dan Restuccia, Jake Sherman, and Bled

for providing the Burning Glass data. Jing Cai provided excellent research assistance with CPS data. A previo

version of this paper was titled “Is College the New High School? Evidence from Vacancy Postings.”

† Go to https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161570 to visit the article page for additional materials and

disclosure statement(s).

Do Recessions Accelerate Routine-Biased Technological

Change? Evidence from Vacancy Postings†

By Brad Hershbein and Lisa B. Kahn*

We show that skill requirements in job vacancy postings differentially

increased in MSAs that were hit hard by the Great Recession, relative

to lesshard-hit areas. These increases persist through at least the

end of 2015 and are correlated with increases in capital investments,

both at the MSA andfirm levels. We also find that effects are most

pronounced in routine-cognitive occupations, which exhibit relative

wage growth as well. We argue that this evidence is consistent with

the restructuring of production toward routine-biased technologies

and the more-skilled workers that complement them, and that the

Great Recession accelerated this process. (JEL E24, E32, J24, J31,

J63, L23, O33)

The employment shift from occupations in the middle of the skill distribution

toward those in the tails is one of the most important trends in the US labor ma

ket over the last 30 years. Previous research makes the compelling case that a

mary driver of this job polarization isroutine-biased technological change (RBTC),

whereby new machine technologies and overseas labor substitute for middle-s

jobs in the United States and are in turn complementary to high-skill co

jobs.1 Until recently, RBTC had been thought to be a gradual, secular phenomen

However, a long theoretical literature, beginning with Schumpeter’s (1939) “c

ative destruction,” suggests adjustments to technological change may be more

sodic. In boom times, high opportunity costs, or frictions such as adjustment co

may inhibit resources from being reallocated optimally in the face of technolog

1See, for example, the seminal work of Autor, Levy, and Murnane (2003); Goos and Manning (2007); Auto

Katz, and Kearney (2008); and Autor and Dorn (2013).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1738 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW JULY 2018

change. Recessions lower the opportunity cost and can produce large enough s

to overcome these frictions.2

Whether adjustments to new technology are smooth or lumpy is important fo

policy and for our understanding of recoveries. The recoveries from the last thr

US recessions (1991, 2001, 2007–2009) have been jobless: employment was s

to rebound despite recovery in aggregate output. The reasons for jobless recov

are not well understood, but a small theoretical literature points to adjustment

as a potential mechanism, since they can generate reallocation that is concent

downturns (Koenders and Rogerson 2005; Berger 2012; Jaimovich and Siu 2012

Such lumpy adjustment may leave a mass of displaced workers with the

skills for new production. Jaimovich and Siu (2015) provide suggestive evidenc

that countercyclical reallocation, in the form of RBTC, and jobless recove

linked. They show that the vast majority of the declines inmiddle-skill employment

have occurred during recessions and that, over the same time period, recovery

jobless only in these occupations. However, there is still relatively little direct e

dence on how firms restructure employment in the face of technological chang

and, in particular, whether this restructuring is gradual or episodic.3

In this paper we investigate how the demand for skills changed over the Grea

Recession. We use a new dataset collected by Burning Glass Technologie

contains thenear-universe of electronically posted job vacancies in 2007 an

2010–2015. Exploiting spatial variation in economic conditions, we establi

new fact: the skill requirements of job ads increase in metropolitan statistical a

(MSAs) that suffered larger employment shocks in the Great Recession, relative

the same areas before the shock and other areas that experienced smaller sho

Our estimates imply that ads posted in a hard-hit metro area are about 5 perc

points (16 percent) more likely to contain education and experience requireme

and about 2–3 percentage points ( 8–12 percent) more likely to state requirem

for cognitive and computer skills. Moreover, the vast majority of this “upskilling

persists through the end of our sample in 2015. That is, even while most meas

local labor-market strength had converged back to pre-recession levels, differ

in advertised skill demands remain. This is true holding constant a rich set of c

trols for the availability of skilled labor and the composition of ads across firms

occupations. In fact, we find that the very firms that upskilled early in the recov

drive the persistence later in our sample period.

These patterns collectively raise the possibility that a structural shift in

demand for skill occurred disproportionately in harder-hit MSAs. In particular, t

skill requirements we explore (education, experience, cognitive, and computer

known to complement routine-biased technologies (Autor, Levy, and Murnane

Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2011). If a structural shift in line with RBTC is occur-

ring, we would expect changes in these skill requirements to be accompanied b

2Many theoretical papers predict this phenomenon. See, for example, Hall (1991, 2005); Caballer

Hammour (1994, 1996); Mortensen and Pissarides (1994); Gomes, Greenwood, and Rebelo (2001); and Koen

and Rogerson (2005).

3For example, Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017) find that the diffusion of industrial robots across US commu

zones reduced aggregate employment and wages; Harrigan, Reshef, and Toubal (2016) show that job polari

tion was more pronounced in French firms with greater shares oftechnology-related occupations; and Hawkins,

Michaels, and Oh (2015) show that capital investments and employment reductions frequently occur togethe

Korean manufacturing plants, but these papers focus on long-run changes.

change. Recessions lower the opportunity cost and can produce large enough s

to overcome these frictions.2

Whether adjustments to new technology are smooth or lumpy is important fo

policy and for our understanding of recoveries. The recoveries from the last thr

US recessions (1991, 2001, 2007–2009) have been jobless: employment was s

to rebound despite recovery in aggregate output. The reasons for jobless recov

are not well understood, but a small theoretical literature points to adjustment

as a potential mechanism, since they can generate reallocation that is concent

downturns (Koenders and Rogerson 2005; Berger 2012; Jaimovich and Siu 2012

Such lumpy adjustment may leave a mass of displaced workers with the

skills for new production. Jaimovich and Siu (2015) provide suggestive evidenc

that countercyclical reallocation, in the form of RBTC, and jobless recove

linked. They show that the vast majority of the declines inmiddle-skill employment

have occurred during recessions and that, over the same time period, recovery

jobless only in these occupations. However, there is still relatively little direct e

dence on how firms restructure employment in the face of technological chang

and, in particular, whether this restructuring is gradual or episodic.3

In this paper we investigate how the demand for skills changed over the Grea

Recession. We use a new dataset collected by Burning Glass Technologie

contains thenear-universe of electronically posted job vacancies in 2007 an

2010–2015. Exploiting spatial variation in economic conditions, we establi

new fact: the skill requirements of job ads increase in metropolitan statistical a

(MSAs) that suffered larger employment shocks in the Great Recession, relative

the same areas before the shock and other areas that experienced smaller sho

Our estimates imply that ads posted in a hard-hit metro area are about 5 perc

points (16 percent) more likely to contain education and experience requireme

and about 2–3 percentage points ( 8–12 percent) more likely to state requirem

for cognitive and computer skills. Moreover, the vast majority of this “upskilling

persists through the end of our sample in 2015. That is, even while most meas

local labor-market strength had converged back to pre-recession levels, differ

in advertised skill demands remain. This is true holding constant a rich set of c

trols for the availability of skilled labor and the composition of ads across firms

occupations. In fact, we find that the very firms that upskilled early in the recov

drive the persistence later in our sample period.

These patterns collectively raise the possibility that a structural shift in

demand for skill occurred disproportionately in harder-hit MSAs. In particular, t

skill requirements we explore (education, experience, cognitive, and computer

known to complement routine-biased technologies (Autor, Levy, and Murnane

Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2011). If a structural shift in line with RBTC is occur-

ring, we would expect changes in these skill requirements to be accompanied b

2Many theoretical papers predict this phenomenon. See, for example, Hall (1991, 2005); Caballer

Hammour (1994, 1996); Mortensen and Pissarides (1994); Gomes, Greenwood, and Rebelo (2001); and Koen

and Rogerson (2005).

3For example, Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017) find that the diffusion of industrial robots across US commu

zones reduced aggregate employment and wages; Harrigan, Reshef, and Toubal (2016) show that job polari

tion was more pronounced in French firms with greater shares oftechnology-related occupations; and Hawkins,

Michaels, and Oh (2015) show that capital investments and employment reductions frequently occur togethe

Korean manufacturing plants, but these papers focus on long-run changes.

1739HERSHBEIN AND KAHN: ROUTINE-BIASED TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGEVOL. 108 NO. 7

accelerated adoption of such technologies, as well. Indeed, we find that increas

in skill requirements are correlated with capital investments at both the MSA a

firm levels. First, using the Ci Technology Database from Harte-Hanks, a marke

intelligence firm, we show that harder-hit MSAs exhibited a relative increase in

investments, as measured by the adoption of personal computers, at the same

as they upskilled in job postings. These differences across MSAs emerge only a

the Great Recession and, once again, persist through our sample period. Secon

link firms in our job postings database to those in the Harte-Hanks database, a

as to publicly traded firms in Compustat. We show that the firms increasing the

capital investments, based on PC adoption and physical capital holdings, are al

more likely to upskill. Thus, increased demand for labor skill appears closely lin

to both general and IT capital investment.

If this increased investment is in fact related to routine-biased techno

we would expect to see the strongest changes to labor characteristics for the jo

most susceptible to such technologies, routine ones. We thus additionally

on different types of routine occupations, exploring joint changes in skill requir

ments, employment, and wages. Following Acemoglu and Autor (2011), we dis

guish routine-cognitive occupations (e.g., clerical, administrative, and sales) fr

routine-manual ones (e.g., production and operatives), and we supplement the

ads data with Current Population Survey (CPS) and Occupational Employm

Statistics (OES) data. For routine-manual occupations, we see evidence consis

with firms’ substitution of technology for labor: a sharp increase in layoff risk fo

harder-hit MSAs early on, and persistently depressed employment, with n

ticular impact on skill requirements. This is the traditional view exhibited in the

polarization literature: employment losses concentrated in occupations we exp

to be most readily replaceable by machines. Consistent with Jaimovich a

(2015), we show that these changes also appear to be episodic around the Gre

Recession. However, in contrast to this conventional view of labor substi

routine-cognitive occupations in harder-hit MSAs surprisingly exhibit only mod

est increases in layoff risk and no relative employment losses. Instead, we show

that these occupations experience pronounced upskilling, as well as modest re

wage and employment growth after the recession. That is, rather than disappe

entirely, surviving routine-cognitive occupations appear to have become both

tively higher-skilled and more productive. These occupations thus became epi

cally less routine, and more cognitive, as a result of the Great Recession.

Taken together, our results suggest that firms located in areas more s

affected by the Great Recession were induced to restructure their production to

greater use of technology and higher-skilled workers; that is, the Great Recess

hastened the polarization of the US labor market.

This paper is related to a number of important literatures. First, we pr

evidence that the Great Recession spurred persistent changes in labor in

a manner consistent with technological change. Several classes of model

adjustment costs can rationalize this result. For instance, firms may make prod

tivity-enhancing improvements in a recession because of a decline in the oppo

nity cost of restructuring (Hall 2005), a shift in managerial attention from grow

to efficiency possibly due to an increased risk of closure (Koenders and Rogers

2005; Gibbons and Roberts 2012), or changes in the costs and benefits of mak

accelerated adoption of such technologies, as well. Indeed, we find that increas

in skill requirements are correlated with capital investments at both the MSA a

firm levels. First, using the Ci Technology Database from Harte-Hanks, a marke

intelligence firm, we show that harder-hit MSAs exhibited a relative increase in

investments, as measured by the adoption of personal computers, at the same

as they upskilled in job postings. These differences across MSAs emerge only a

the Great Recession and, once again, persist through our sample period. Secon

link firms in our job postings database to those in the Harte-Hanks database, a

as to publicly traded firms in Compustat. We show that the firms increasing the

capital investments, based on PC adoption and physical capital holdings, are al

more likely to upskill. Thus, increased demand for labor skill appears closely lin

to both general and IT capital investment.

If this increased investment is in fact related to routine-biased techno

we would expect to see the strongest changes to labor characteristics for the jo

most susceptible to such technologies, routine ones. We thus additionally

on different types of routine occupations, exploring joint changes in skill requir

ments, employment, and wages. Following Acemoglu and Autor (2011), we dis

guish routine-cognitive occupations (e.g., clerical, administrative, and sales) fr

routine-manual ones (e.g., production and operatives), and we supplement the

ads data with Current Population Survey (CPS) and Occupational Employm

Statistics (OES) data. For routine-manual occupations, we see evidence consis

with firms’ substitution of technology for labor: a sharp increase in layoff risk fo

harder-hit MSAs early on, and persistently depressed employment, with n

ticular impact on skill requirements. This is the traditional view exhibited in the

polarization literature: employment losses concentrated in occupations we exp

to be most readily replaceable by machines. Consistent with Jaimovich a

(2015), we show that these changes also appear to be episodic around the Gre

Recession. However, in contrast to this conventional view of labor substi

routine-cognitive occupations in harder-hit MSAs surprisingly exhibit only mod

est increases in layoff risk and no relative employment losses. Instead, we show

that these occupations experience pronounced upskilling, as well as modest re

wage and employment growth after the recession. That is, rather than disappe

entirely, surviving routine-cognitive occupations appear to have become both

tively higher-skilled and more productive. These occupations thus became epi

cally less routine, and more cognitive, as a result of the Great Recession.

Taken together, our results suggest that firms located in areas more s

affected by the Great Recession were induced to restructure their production to

greater use of technology and higher-skilled workers; that is, the Great Recess

hastened the polarization of the US labor market.

This paper is related to a number of important literatures. First, we pr

evidence that the Great Recession spurred persistent changes in labor in

a manner consistent with technological change. Several classes of model

adjustment costs can rationalize this result. For instance, firms may make prod

tivity-enhancing improvements in a recession because of a decline in the oppo

nity cost of restructuring (Hall 2005), a shift in managerial attention from grow

to efficiency possibly due to an increased risk of closure (Koenders and Rogers

2005; Gibbons and Roberts 2012), or changes in the costs and benefits of mak

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1740 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW JULY 2018

layoffs (Berger 2012; Jaimovich and Siu 2012). In addition, recessions may driv

Schumpeterian cleansing, whereby older, less-productive firms die, making wa

newer, more-productive firms. Empirical support for adjustment-cost mod

focused on the impacts of competition or trade shocks on productivity. For exa

Bloom, Draca, and Van Reenen (2016) show that increased Chinese import com

tition in Europe led to technological change within firms.4 Our paper adds to this

literature by highlighting recession-induced changes in the firm-level demand

skill. This may have important consequences for labor market recoveries, since

implies potential for a sudden skill mismatch.

Second, the Burning Glass job postings data provide a unique opportunity to

sure changes in skill requirements both across and within occupations. In contr

the extant literature on job polarization has focused on shifts across occupation

and has therefore been unable to ascertain the importance of the intra-occupa

margin. We show that the bulk of upskilling occurs within occupations, suggest

this margin is quite important. Moreover, our finding that upskilling is concentr

within routine-cognitive occupations and is accompanied by relative wage grow

implies that RBTC occurs both within and across occupations. This result helps

clarify work by Beaudry, Green, and Sand (2014, 2016) and others documentin

“great reversal” in demand for cognitive skill. They show that since 2000, cogn

occupations have seen no gains in employment or wages, and that college grad

have become more likely to work in routine occupations than previously. They

that a decrease in demand for cognitive occupations drove college graduates t

jobs lower in the occupational distribution, squeezing out the high school gradu

who formerly held them. This is something of a puzzle, especially given the com

mon belief that technological change continues and the fact that more-skilled

ers still earn a sizable premium in the labor market (Card, Heining, and Kline 2

Card, Cardoso, and Kline 2016). We hypothesize part of the solution to this puz

that cognitive workers are being drawn into (formerly) routine-task occupation

the skill content of these occupations evolves. These changes make the occupa

more skilled and therefore likely more desirable than before, although probabl

not as desirable as traditional high-skilled jobs.5

Third, we contribute to a growing literature exploiting data on vacancy

ings. Although several studies have used aggregate vacancy data, and even va

microdata, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Openings and Labor Market

Turnover (JOLTS) survey (Davis, Faberman, and Haltiwanger 2012, 2013), thes

data contain little information on the characteristics of a given vacancy or the fi

that is posting it. Fewer studies have used vacancy data that contain informatio

on the occupation or specific requirements of the job posted, and these have g

ally used narrow slices of the data (Rothwell 2014), or data that are limited to o

vacancy source (Kuhn and Shen 2013; Marinescu 2017). To our knowledg

4Additionally, Nickell (1996) provides evidence that increased competition is associated with faster total

tor productivity growth; Syverson (2004a, b) shows that productivity is higher in industries and geographies

greater substitutability of products across firms; and Bernard, Redding, and Schott (2011) show firms shift t

higher productivity products upon the liberalization of firm trade. Other examples are cited in each of these

5Our analyses, however, do not explain why employment and wages have not grown in high-skill occupa

Deming (2017) proposes a compelling hypothesis that a rising importance of social skills, especially in conju

with cognitive skills, can help account for this fact.

layoffs (Berger 2012; Jaimovich and Siu 2012). In addition, recessions may driv

Schumpeterian cleansing, whereby older, less-productive firms die, making wa

newer, more-productive firms. Empirical support for adjustment-cost mod

focused on the impacts of competition or trade shocks on productivity. For exa

Bloom, Draca, and Van Reenen (2016) show that increased Chinese import com

tition in Europe led to technological change within firms.4 Our paper adds to this

literature by highlighting recession-induced changes in the firm-level demand

skill. This may have important consequences for labor market recoveries, since

implies potential for a sudden skill mismatch.

Second, the Burning Glass job postings data provide a unique opportunity to

sure changes in skill requirements both across and within occupations. In contr

the extant literature on job polarization has focused on shifts across occupation

and has therefore been unable to ascertain the importance of the intra-occupa

margin. We show that the bulk of upskilling occurs within occupations, suggest

this margin is quite important. Moreover, our finding that upskilling is concentr

within routine-cognitive occupations and is accompanied by relative wage grow

implies that RBTC occurs both within and across occupations. This result helps

clarify work by Beaudry, Green, and Sand (2014, 2016) and others documentin

“great reversal” in demand for cognitive skill. They show that since 2000, cogn

occupations have seen no gains in employment or wages, and that college grad

have become more likely to work in routine occupations than previously. They

that a decrease in demand for cognitive occupations drove college graduates t

jobs lower in the occupational distribution, squeezing out the high school gradu

who formerly held them. This is something of a puzzle, especially given the com

mon belief that technological change continues and the fact that more-skilled

ers still earn a sizable premium in the labor market (Card, Heining, and Kline 2

Card, Cardoso, and Kline 2016). We hypothesize part of the solution to this puz

that cognitive workers are being drawn into (formerly) routine-task occupation

the skill content of these occupations evolves. These changes make the occupa

more skilled and therefore likely more desirable than before, although probabl

not as desirable as traditional high-skilled jobs.5

Third, we contribute to a growing literature exploiting data on vacancy

ings. Although several studies have used aggregate vacancy data, and even va

microdata, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Openings and Labor Market

Turnover (JOLTS) survey (Davis, Faberman, and Haltiwanger 2012, 2013), thes

data contain little information on the characteristics of a given vacancy or the fi

that is posting it. Fewer studies have used vacancy data that contain informatio

on the occupation or specific requirements of the job posted, and these have g

ally used narrow slices of the data (Rothwell 2014), or data that are limited to o

vacancy source (Kuhn and Shen 2013; Marinescu 2017). To our knowledg

4Additionally, Nickell (1996) provides evidence that increased competition is associated with faster total

tor productivity growth; Syverson (2004a, b) shows that productivity is higher in industries and geographies

greater substitutability of products across firms; and Bernard, Redding, and Schott (2011) show firms shift t

higher productivity products upon the liberalization of firm trade. Other examples are cited in each of these

5Our analyses, however, do not explain why employment and wages have not grown in high-skill occupa

Deming (2017) proposes a compelling hypothesis that a rising importance of social skills, especially in conju

with cognitive skills, can help account for this fact.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1741HERSHBEIN AND KAHN: ROUTINE-BIASED TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGEVOL. 108 NO. 7

are the first study to use data based on anear-universe of online job postings that

covers every metropolitan area in the United States. Online job vacancies repre

but one slice of the labor market, and, by their nature, will overrepresent grow

firms (Davis, Faberman, and Haltiwanger 2013). Nonetheless, we show that lin

vacancies to data on employment, wages, and capital investments, the last at

firm level, presents consistent evidence on how labor markets changed followin

the Great Recession.

We demonstrate that during the Great Recession firms changed not only who

they would hire in the recovery, but how they would produce. Instead of occurr

gradually, with relatively few workers needing to be reallocated at any given ti

we find support that changes in demand for skill were episodic, resulting in a sw

of displaced workers whose skills were suddenly rendered obsolete as fir

cheted up their requirements. The need to reallocate workers on such a large s

may help drive jobless recoveries. It also has distributional consequences

that low-skill workers are well known to suffer worse employment and wage co

quences in recessions.6 Finally, this type of episodic reallocation likely plays a role

in the well-noted and marked decline in male employment-to-population ratio

the past 25 years, especially since these declines have beenstair-step around reces-

sions (Moffitt 2012).7 The evidence provided in this paper is thus integral for under

standing worker reallocation, and can help inform policymakers about the optim

mix during a downturn of worker retraining and subsidizing job search th

unemployment insurance.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section I introduces the dat

while Section II summarizes our methodology. Section III presents new fa

on changes in skill requirements as a function of local labor market con

Section IVinvestigateshow thesechangesare linked to capitalinvestments.

Section V examines cross-occupation heterogeneity in response to local labor

ket shocks on skill requirements, employment, and wages, with a particular foc

routine occupations. Section VI concludes.

I. Data

Our data come from a unique source: microdata from nearly 100 million elec

tronic job postings in the United States that span the Great Recession (

2007 and 2015). These job postings were collected and assembled by Burning

Technologies, an employment analytics and labor market information firm. In t

section, we describe the data and our particular sample construction. We provi

detailed examination of the sample’s characteristics and representativeness in

Appendix A.

6See von Wachter and Handwerker (2008); Hoynes, Miller, and Schaller (2012); and Forsythe (2016).

7Supporting the notion that episodic restructuring drives stair-step declines in male employment, Foote a

Ryan (2014) point out that middle-skill workers, the most vulnerable to RBTC, are most at risk of leaving the

force when unemployed.

are the first study to use data based on anear-universe of online job postings that

covers every metropolitan area in the United States. Online job vacancies repre

but one slice of the labor market, and, by their nature, will overrepresent grow

firms (Davis, Faberman, and Haltiwanger 2013). Nonetheless, we show that lin

vacancies to data on employment, wages, and capital investments, the last at

firm level, presents consistent evidence on how labor markets changed followin

the Great Recession.

We demonstrate that during the Great Recession firms changed not only who

they would hire in the recovery, but how they would produce. Instead of occurr

gradually, with relatively few workers needing to be reallocated at any given ti

we find support that changes in demand for skill were episodic, resulting in a sw

of displaced workers whose skills were suddenly rendered obsolete as fir

cheted up their requirements. The need to reallocate workers on such a large s

may help drive jobless recoveries. It also has distributional consequences

that low-skill workers are well known to suffer worse employment and wage co

quences in recessions.6 Finally, this type of episodic reallocation likely plays a role

in the well-noted and marked decline in male employment-to-population ratio

the past 25 years, especially since these declines have beenstair-step around reces-

sions (Moffitt 2012).7 The evidence provided in this paper is thus integral for under

standing worker reallocation, and can help inform policymakers about the optim

mix during a downturn of worker retraining and subsidizing job search th

unemployment insurance.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section I introduces the dat

while Section II summarizes our methodology. Section III presents new fa

on changes in skill requirements as a function of local labor market con

Section IVinvestigateshow thesechangesare linked to capitalinvestments.

Section V examines cross-occupation heterogeneity in response to local labor

ket shocks on skill requirements, employment, and wages, with a particular foc

routine occupations. Section VI concludes.

I. Data

Our data come from a unique source: microdata from nearly 100 million elec

tronic job postings in the United States that span the Great Recession (

2007 and 2015). These job postings were collected and assembled by Burning

Technologies, an employment analytics and labor market information firm. In t

section, we describe the data and our particular sample construction. We provi

detailed examination of the sample’s characteristics and representativeness in

Appendix A.

6See von Wachter and Handwerker (2008); Hoynes, Miller, and Schaller (2012); and Forsythe (2016).

7Supporting the notion that episodic restructuring drives stair-step declines in male employment, Foote a

Ryan (2014) point out that middle-skill workers, the most vulnerable to RBTC, are most at risk of leaving the

force when unemployed.

1742 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW JULY 2018

A. Burning Glass Overview

Burning Glass Technologies—henceforth, BG or Burning Glass—examines som

40,000 online job boards and company websites to aggregate the job postings,

and deduplicate them into a systematic,machine-readable form, and create labor

market analytic products. Thanks to the breadth of this coverage, BG believes

resulting database captures a near-universe of jobs that were posted online. T

a special agreement, we obtained these posting-level data for the years 2007

from 2010 through 2015, covering every MSA in the United States.8

The two key advantages of our data are its breadth and detail. The broad cov

age of the database presents a substantial strength over datasets based on a s

vacancy source, such as CareerBuilder.com. While the JOLTS asks a nationally

resentative sample of employers about vacancies they wish to fill in the near te

it is typically available only at aggregated levels, and contains relatively little in

mation about the characteristics of vacancies. In contrast, the BG data contain

70 possible standardized fields for each vacancy. We exploit detailed informati

occupation, geography, skill requirements, and firm identifiers. The codified sk

include stated education and experience requirements, as well as thousands of

cific skills standardized from open text in each job posting.9 The data thus allow for

analysis of a key, but largely unexplored, margin of firm demand: skill requirem

within occupation.10 Moreover, they allow for afirm-level analysis, which, as we

show below, is key to disentangling mechanisms for upskilling.

However, the richness of the BG data comes with a few shortcomings. Notab

the database covers only vacancies posted on the internet. First, Davis, Faberm

and Haltiwanger (2013) show that the distribution of vacancies in JOLTS overre

resents growing firms. Although roughly two-thirds of hiring is replacement hir

(Lazear and Spletzer 2012), vacancies in general will be somewhat skewed tow

certain areas of the economy. Second, even though vacancies for availab

have increasingly appeared online instead of in traditional sources, such as new

papers, one may worry that the types of jobs posted online are not representat

of all openings. In online Appendix A, we provide a detailed description o

industry-occupation mix of vacancies in BG relative to other sources (JOLTS, th

Current Population Survey, and Occupational Employment Statistics), an analy

8Our dataset was provided in February 2016. Although BG’s algorithms for removing duplicates and codin

ad characteristics change over time, each iteration is applied to all postings in the data. The database unfort

lacks postings from 2008 and 2009. These years would be useful for completeness and for understanding th

timing over which skill requirements changed; however, since hiring volume fell byone-third in 2008 and did not

begin to recover until 2010 (per JOLTS), and our focus is on longer-term changes in hiring demand, addition

for the recession years are not integral for this paper. We also have data on jobs posted in Micropolitan Stat

Areas, which we do not use for lack of some of the labor market indicators in these areas, and substantial no

the ones that are available. They represent 5.6 percent of all posted ads.

9For example, an ad might ask for a worker who is bilingual or who can organize and manage a team. BG

and codes these and other skills into a taxonomy of thousands of unique, but standardized requirements. Be

with a set of predefined possible skills, BG searches text in an ad for an indication that the skill is required.

example, for team work, they search for the key words “team work” but also look for variations such as “abi

work as a team.”

10Other private-sector firms, such as Wanted Analytics, used by the Conference Board’s Help-Wanted On

Index, also offer disaggregated data, but not skill requirements. State vacancy surveys, conducted by a limit

ber of states, sometimes collect certain skill requirements, but cover only a few geographic areas and are ge

not comparable across states (Carnevale, Jayasundera, and Repnikov 2014; Rothwell 2014).

A. Burning Glass Overview

Burning Glass Technologies—henceforth, BG or Burning Glass—examines som

40,000 online job boards and company websites to aggregate the job postings,

and deduplicate them into a systematic,machine-readable form, and create labor

market analytic products. Thanks to the breadth of this coverage, BG believes

resulting database captures a near-universe of jobs that were posted online. T

a special agreement, we obtained these posting-level data for the years 2007

from 2010 through 2015, covering every MSA in the United States.8

The two key advantages of our data are its breadth and detail. The broad cov

age of the database presents a substantial strength over datasets based on a s

vacancy source, such as CareerBuilder.com. While the JOLTS asks a nationally

resentative sample of employers about vacancies they wish to fill in the near te

it is typically available only at aggregated levels, and contains relatively little in

mation about the characteristics of vacancies. In contrast, the BG data contain

70 possible standardized fields for each vacancy. We exploit detailed informati

occupation, geography, skill requirements, and firm identifiers. The codified sk

include stated education and experience requirements, as well as thousands of

cific skills standardized from open text in each job posting.9 The data thus allow for

analysis of a key, but largely unexplored, margin of firm demand: skill requirem

within occupation.10 Moreover, they allow for afirm-level analysis, which, as we

show below, is key to disentangling mechanisms for upskilling.

However, the richness of the BG data comes with a few shortcomings. Notab

the database covers only vacancies posted on the internet. First, Davis, Faberm

and Haltiwanger (2013) show that the distribution of vacancies in JOLTS overre

resents growing firms. Although roughly two-thirds of hiring is replacement hir

(Lazear and Spletzer 2012), vacancies in general will be somewhat skewed tow

certain areas of the economy. Second, even though vacancies for availab

have increasingly appeared online instead of in traditional sources, such as new

papers, one may worry that the types of jobs posted online are not representat

of all openings. In online Appendix A, we provide a detailed description o

industry-occupation mix of vacancies in BG relative to other sources (JOLTS, th

Current Population Survey, and Occupational Employment Statistics), an analy

8Our dataset was provided in February 2016. Although BG’s algorithms for removing duplicates and codin

ad characteristics change over time, each iteration is applied to all postings in the data. The database unfort

lacks postings from 2008 and 2009. These years would be useful for completeness and for understanding th

timing over which skill requirements changed; however, since hiring volume fell byone-third in 2008 and did not

begin to recover until 2010 (per JOLTS), and our focus is on longer-term changes in hiring demand, addition

for the recession years are not integral for this paper. We also have data on jobs posted in Micropolitan Stat

Areas, which we do not use for lack of some of the labor market indicators in these areas, and substantial no

the ones that are available. They represent 5.6 percent of all posted ads.

9For example, an ad might ask for a worker who is bilingual or who can organize and manage a team. BG

and codes these and other skills into a taxonomy of thousands of unique, but standardized requirements. Be

with a set of predefined possible skills, BG searches text in an ad for an indication that the skill is required.

example, for team work, they search for the key words “team work” but also look for variations such as “abi

work as a team.”

10Other private-sector firms, such as Wanted Analytics, used by the Conference Board’s Help-Wanted On

Index, also offer disaggregated data, but not skill requirements. State vacancy surveys, conducted by a limit

ber of states, sometimes collect certain skill requirements, but cover only a few geographic areas and are ge

not comparable across states (Carnevale, Jayasundera, and Repnikov 2014; Rothwell 2014).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1743HERSHBEIN AND KAHN: ROUTINE-BIASED TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGEVOL. 108 NO. 7

of how it has changed over our sample period, and various validity checks cond

on the data both by us and by other researchers. To briefly summarize, althoug

postings are disproportionately concentrated in occupations and industries tha

ically require greater skill, the distributions are relatively stable across time, an

the aggregate and industry trends in the quantity of vacancies track other sour

reasonably closely.

Another downside of the BG data is that vacancies represent just one

by which a firm may adjust labor inputs: through stated, but not necessarily rea

ized, demand. For a complete picture, one would also like to see hires, separat

wages, and other measures (e.g., incumbent worker training, recruitment inten

(Davis, Faberman, and Haltiwanger 2013)). Thus, we also provide corroborating

evidence on some of these margins using supplemental datasets, as described

We restrict our main BG sample to ads withnon-missing employers that posted

at least 10 ads over the sample period of 2007 and 2010–2015. Employer nam

missing in 40 percent of postings, primarily from those listed on recruiting web

that typically do not reveal the employer.11 Many of our analyses exploitfirm-level

information to distinguish among possible mechanisms for upskilling. We there

choose to focus our entire analysis on the consistent sample of ads with non-m

firms, with a sufficient number of observations per firm to estimate firm-level c

acteristics. However, we have performed analyses not requiring firm-level info

tion on the full dataset and obtain very similar results. Moreover, we have confi

that the probability of satisfying this sample criterion (having a valid firm ident

does not vary over the business cycle (see online Appendix A.8). Thus, our sam

restriction should not confound the estimated relationship between local labor

ket conditions and the skill requirements of postings.

B. Skill Requirements in Burning Glass

In our analyses, we exploit four categories of skill requirements: stated educ

and experience requirements, stated demand for skills that we classify as “cog

tive,” and stated demand for computer skills. We choose these skill requiremen

for two reasons. First, they represent a broad swath of human capital measures

which both employers and economists have interest. Second, they reflect what

economics discipline has learned about technological change over the past 20

(Autor, Levy, and Murnane 2003; Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2011). In particular,

the RBTC literature emphasizes that new information technology or cheap over

labor substitute for routine, algorithmic, middle-skill tasks. These new technolo

are in turn complementary with high-skill cognitive, abstract tasks.12 High-skilled

workers favored by RBTC may be required to work with computers and perform

11When name is available, Burning Glass uses a proprietary algorithm to group name variants into a stan

set: for example, “Bausch and Lomb,” “Bausch Lomb,” and “Bausch & Lomb” would be grouped together. W

perform some additional cleaning on firm name, removing any remaining punctuation, spaces, and a few pro

atic words, such as “Incorporated” or “Inc.” The 10-ad restriction drops about 4 percent of job ads that list a

name. However, employer names with very few ads are likely to be miscoded (for example, capturing a frag

of the city name).

12This literature finds also that RBTC may indirectly affect low-skill, manual tasks (Autor and Dorn 2013)

downside of the BG sample is that low-skill jobs are underrepresented. We thus focus our analysis on the de

which employers shift demand from medium- toward high-skill tasks and workers.

of how it has changed over our sample period, and various validity checks cond

on the data both by us and by other researchers. To briefly summarize, althoug

postings are disproportionately concentrated in occupations and industries tha

ically require greater skill, the distributions are relatively stable across time, an

the aggregate and industry trends in the quantity of vacancies track other sour

reasonably closely.

Another downside of the BG data is that vacancies represent just one

by which a firm may adjust labor inputs: through stated, but not necessarily rea

ized, demand. For a complete picture, one would also like to see hires, separat

wages, and other measures (e.g., incumbent worker training, recruitment inten

(Davis, Faberman, and Haltiwanger 2013)). Thus, we also provide corroborating

evidence on some of these margins using supplemental datasets, as described

We restrict our main BG sample to ads withnon-missing employers that posted

at least 10 ads over the sample period of 2007 and 2010–2015. Employer nam

missing in 40 percent of postings, primarily from those listed on recruiting web

that typically do not reveal the employer.11 Many of our analyses exploitfirm-level

information to distinguish among possible mechanisms for upskilling. We there

choose to focus our entire analysis on the consistent sample of ads with non-m

firms, with a sufficient number of observations per firm to estimate firm-level c

acteristics. However, we have performed analyses not requiring firm-level info

tion on the full dataset and obtain very similar results. Moreover, we have confi

that the probability of satisfying this sample criterion (having a valid firm ident

does not vary over the business cycle (see online Appendix A.8). Thus, our sam

restriction should not confound the estimated relationship between local labor

ket conditions and the skill requirements of postings.

B. Skill Requirements in Burning Glass

In our analyses, we exploit four categories of skill requirements: stated educ

and experience requirements, stated demand for skills that we classify as “cog

tive,” and stated demand for computer skills. We choose these skill requiremen

for two reasons. First, they represent a broad swath of human capital measures

which both employers and economists have interest. Second, they reflect what

economics discipline has learned about technological change over the past 20

(Autor, Levy, and Murnane 2003; Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2011). In particular,

the RBTC literature emphasizes that new information technology or cheap over

labor substitute for routine, algorithmic, middle-skill tasks. These new technolo

are in turn complementary with high-skill cognitive, abstract tasks.12 High-skilled

workers favored by RBTC may be required to work with computers and perform

11When name is available, Burning Glass uses a proprietary algorithm to group name variants into a stan

set: for example, “Bausch and Lomb,” “Bausch Lomb,” and “Bausch & Lomb” would be grouped together. W

perform some additional cleaning on firm name, removing any remaining punctuation, spaces, and a few pro

atic words, such as “Incorporated” or “Inc.” The 10-ad restriction drops about 4 percent of job ads that list a

name. However, employer names with very few ads are likely to be miscoded (for example, capturing a frag

of the city name).

12This literature finds also that RBTC may indirectly affect low-skill, manual tasks (Autor and Dorn 2013)

downside of the BG sample is that low-skill jobs are underrepresented. We thus focus our analysis on the de

which employers shift demand from medium- toward high-skill tasks and workers.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1744 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW JULY 2018

more versatile set of functions. Indeed, thenon-algorithmic tasks that complement

routine-task performing machines or overseas labor involve more complexity,

lem solving, and analytical skills, and the ability to determine which tasks need

be performed at a given moment.

In accord with human capital theory, we believe more-educated workers or t

with greater experience on the job will be better able to perform these function13

In online Appendix A.3, to cross-validate the data, we show that education req

ments strongly correlate with average education levels of employed workers at

MSA and occupation levels.

We categorize cognitive and computer skill requirements based on the open

fields for skills. We designate an ad as requiring computer skills if it contains th

key word “computer” or it is categorized as software by BG.14 We define cognitive

skill requirements based on a set of key words chosen deliberately to match

non-routine analytical job tasks used in Autor, Levy, and Murnane (2003) and s

sequently used by the majority of papers studying RBTC and polarization. We a

ensure that the presence of these key words correlates with external measures

cognitive skill at the occupation level.15

This set of skills (education, experience, cognitive, and computer) aligns wel

with our priors on how jobs change with the availability of computers (Brynjolfs

and McAfee 2011). For example, a sales person who previously devoted most o

or her energy to client relations may now be required to use data analytics to b

ter target packages to clients. This salesperson now needs computer and analy

skills, and some experience in the field may help in mapping data recommenda

to practice. Similarly, thanks to machine vision technology, a quality control op

ator no longer need spend his or her time measuring and identifying the shape

produced goods, but instead can be diverted to other tasks such as troubleshoo

and making judgment calls in design optimization. This set of tasks requires hig

cognitive function and intuition that can be gained by experience.16

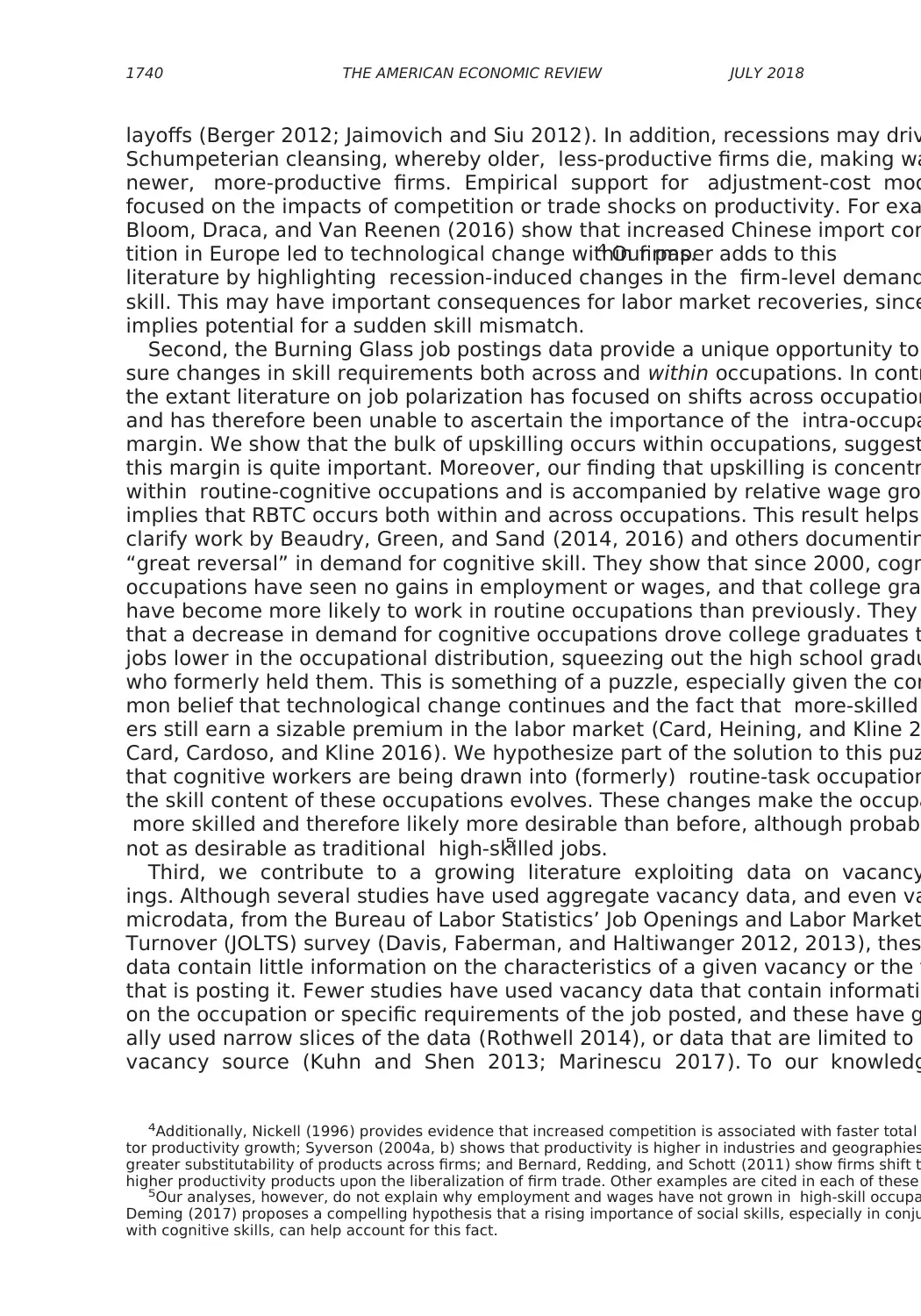

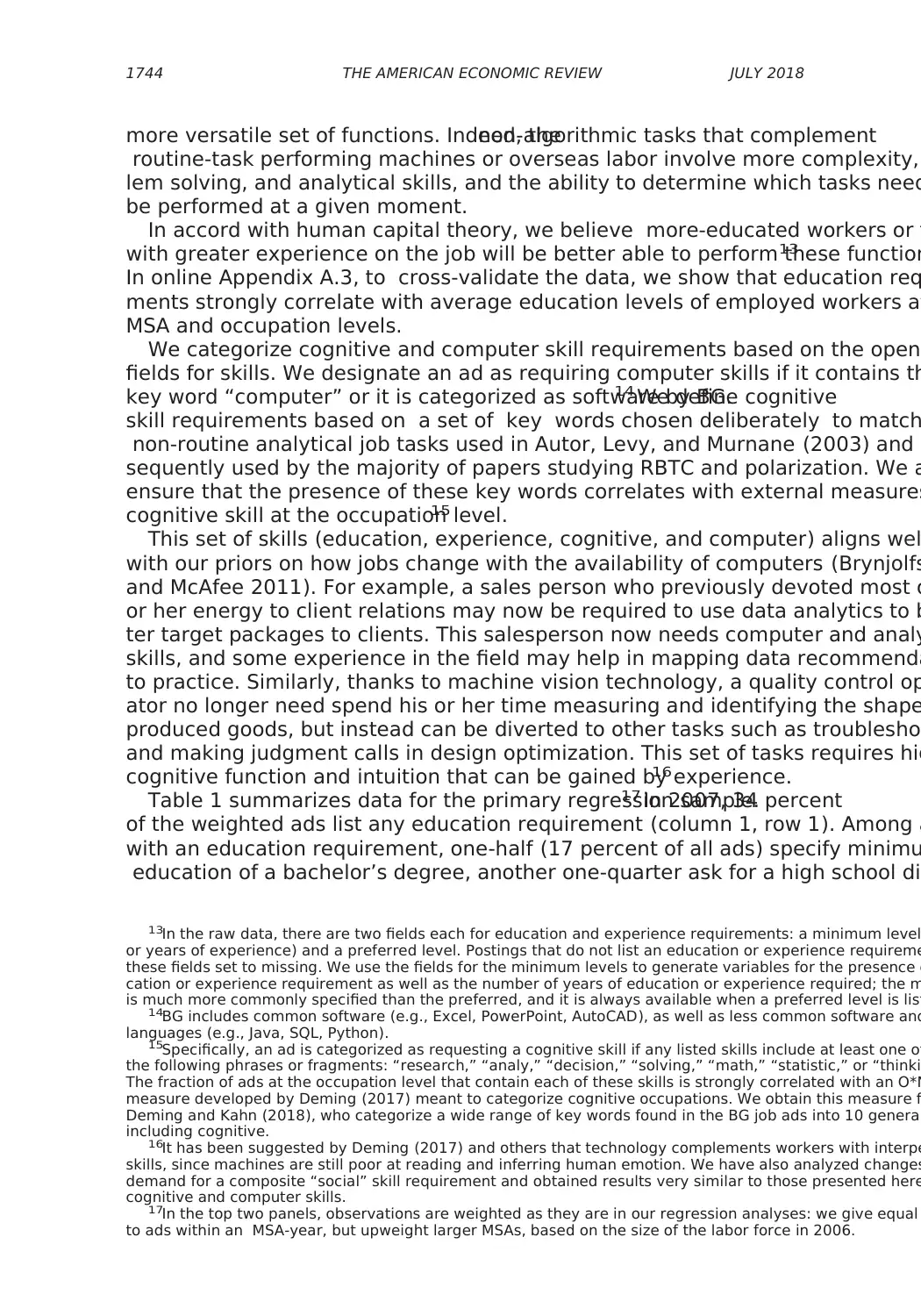

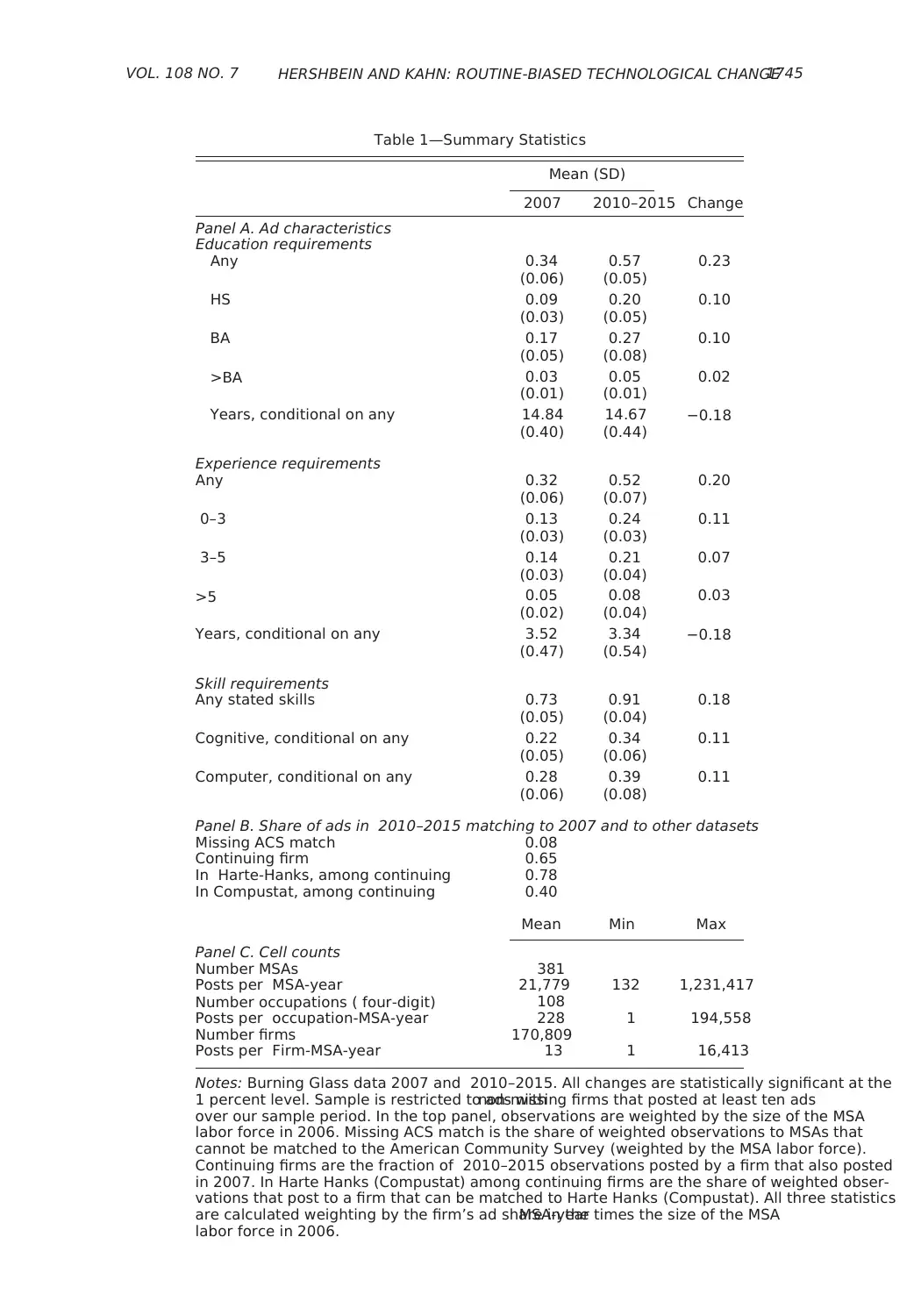

Table 1 summarizes data for the primary regression sample.17 In 2007, 34 percent

of the weighted ads list any education requirement (column 1, row 1). Among a

with an education requirement, one-half (17 percent of all ads) specify minimu

education of a bachelor’s degree, another one-quarter ask for a high school dip

13In the raw data, there are two fields each for education and experience requirements: a minimum level

or years of experience) and a preferred level. Postings that do not list an education or experience requireme

these fields set to missing. We use the fields for the minimum levels to generate variables for the presence o

cation or experience requirement as well as the number of years of education or experience required; the m

is much more commonly specified than the preferred, and it is always available when a preferred level is list

14BG includes common software (e.g., Excel, PowerPoint, AutoCAD), as well as less common software and

languages (e.g., Java, SQL, Python).

15Specifically, an ad is categorized as requesting a cognitive skill if any listed skills include at least one of

the following phrases or fragments: “research,” “analy,” “decision,” “solving,” “math,” “statistic,” or “thinki

The fraction of ads at the occupation level that contain each of these skills is strongly correlated with an O*N

measure developed by Deming (2017) meant to categorize cognitive occupations. We obtain this measure f

Deming and Kahn (2018), who categorize a wide range of key words found in the BG job ads into 10 general

including cognitive.

16It has been suggested by Deming (2017) and others that technology complements workers with interpe

skills, since machines are still poor at reading and inferring human emotion. We have also analyzed changes

demand for a composite “social” skill requirement and obtained results very similar to those presented here

cognitive and computer skills.

17In the top two panels, observations are weighted as they are in our regression analyses: we give equal

to ads within an MSA-year, but upweight larger MSAs, based on the size of the labor force in 2006.

more versatile set of functions. Indeed, thenon-algorithmic tasks that complement

routine-task performing machines or overseas labor involve more complexity,

lem solving, and analytical skills, and the ability to determine which tasks need

be performed at a given moment.

In accord with human capital theory, we believe more-educated workers or t

with greater experience on the job will be better able to perform these function13

In online Appendix A.3, to cross-validate the data, we show that education req

ments strongly correlate with average education levels of employed workers at

MSA and occupation levels.

We categorize cognitive and computer skill requirements based on the open

fields for skills. We designate an ad as requiring computer skills if it contains th

key word “computer” or it is categorized as software by BG.14 We define cognitive

skill requirements based on a set of key words chosen deliberately to match

non-routine analytical job tasks used in Autor, Levy, and Murnane (2003) and s

sequently used by the majority of papers studying RBTC and polarization. We a

ensure that the presence of these key words correlates with external measures

cognitive skill at the occupation level.15

This set of skills (education, experience, cognitive, and computer) aligns wel

with our priors on how jobs change with the availability of computers (Brynjolfs

and McAfee 2011). For example, a sales person who previously devoted most o

or her energy to client relations may now be required to use data analytics to b

ter target packages to clients. This salesperson now needs computer and analy

skills, and some experience in the field may help in mapping data recommenda

to practice. Similarly, thanks to machine vision technology, a quality control op

ator no longer need spend his or her time measuring and identifying the shape

produced goods, but instead can be diverted to other tasks such as troubleshoo

and making judgment calls in design optimization. This set of tasks requires hig

cognitive function and intuition that can be gained by experience.16

Table 1 summarizes data for the primary regression sample.17 In 2007, 34 percent

of the weighted ads list any education requirement (column 1, row 1). Among a

with an education requirement, one-half (17 percent of all ads) specify minimu

education of a bachelor’s degree, another one-quarter ask for a high school dip

13In the raw data, there are two fields each for education and experience requirements: a minimum level

or years of experience) and a preferred level. Postings that do not list an education or experience requireme

these fields set to missing. We use the fields for the minimum levels to generate variables for the presence o

cation or experience requirement as well as the number of years of education or experience required; the m

is much more commonly specified than the preferred, and it is always available when a preferred level is list

14BG includes common software (e.g., Excel, PowerPoint, AutoCAD), as well as less common software and

languages (e.g., Java, SQL, Python).

15Specifically, an ad is categorized as requesting a cognitive skill if any listed skills include at least one of

the following phrases or fragments: “research,” “analy,” “decision,” “solving,” “math,” “statistic,” or “thinki

The fraction of ads at the occupation level that contain each of these skills is strongly correlated with an O*N

measure developed by Deming (2017) meant to categorize cognitive occupations. We obtain this measure f

Deming and Kahn (2018), who categorize a wide range of key words found in the BG job ads into 10 general

including cognitive.

16It has been suggested by Deming (2017) and others that technology complements workers with interpe

skills, since machines are still poor at reading and inferring human emotion. We have also analyzed changes

demand for a composite “social” skill requirement and obtained results very similar to those presented here

cognitive and computer skills.

17In the top two panels, observations are weighted as they are in our regression analyses: we give equal

to ads within an MSA-year, but upweight larger MSAs, based on the size of the labor force in 2006.

1745HERSHBEIN AND KAHN: ROUTINE-BIASED TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGEVOL. 108 NO. 7

Table 1—Summary Statistics

Mean (SD)

2007 2010–2015 Change

Panel A. Ad characteristics

Education requirements

Any 0.34 0.57 0.23

(0.06) (0.05)

HS 0.09 0.20 0.10

(0.03) (0.05)

BA 0.17 0.27 0.10

(0.05) (0.08)

>BA 0.03 0.05 0.02

(0.01) (0.01)

Years, conditional on any 14.84 14.67 −0.18

(0.40) (0.44)

Experience requirements

Any 0.32 0.52 0.20

(0.06) (0.07)

0–3 0.13 0.24 0.11

(0.03) (0.03)

3–5 0.14 0.21 0.07

(0.03) (0.04)

>5 0.05 0.08 0.03

(0.02) (0.04)

Years, conditional on any 3.52 3.34 −0.18

(0.47) (0.54)

Skill requirements

Any stated skills 0.73 0.91 0.18

(0.05) (0.04)

Cognitive, conditional on any 0.22 0.34 0.11

(0.05) (0.06)

Computer, conditional on any 0.28 0.39 0.11

(0.06) (0.08)

Panel B. Share of ads in 2010–2015 matching to 2007 and to other datasets

Missing ACS match 0.08

Continuing firm 0.65

In Harte-Hanks, among continuing 0.78

In Compustat, among continuing 0.40

Mean Min Max

Panel C. Cell counts

Number MSAs 381

Posts per MSA-year 21,779 132 1,231,417

Number occupations ( four-digit) 108

Posts per occupation-MSA-year 228 1 194,558

Number firms 170,809

Posts per Firm-MSA-year 13 1 16,413

Notes: Burning Glass data 2007 and 2010–2015. All changes are statistically significant at the

1 percent level. Sample is restricted to ads withnon-missing firms that posted at least ten ads

over our sample period. In the top panel, observations are weighted by the size of the MSA

labor force in 2006. Missing ACS match is the share of weighted observations to MSAs that

cannot be matched to the American Community Survey (weighted by the MSA labor force).

Continuing firms are the fraction of 2010–2015 observations posted by a firm that also posted

in 2007. In Harte Hanks (Compustat) among continuing firms are the share of weighted obser-

vations that post to a firm that can be matched to Harte Hanks (Compustat). All three statistics

are calculated weighting by the firm’s ad share in theMSA-year times the size of the MSA

labor force in 2006.

Table 1—Summary Statistics

Mean (SD)

2007 2010–2015 Change

Panel A. Ad characteristics

Education requirements

Any 0.34 0.57 0.23

(0.06) (0.05)

HS 0.09 0.20 0.10

(0.03) (0.05)

BA 0.17 0.27 0.10

(0.05) (0.08)

>BA 0.03 0.05 0.02

(0.01) (0.01)

Years, conditional on any 14.84 14.67 −0.18

(0.40) (0.44)

Experience requirements

Any 0.32 0.52 0.20

(0.06) (0.07)

0–3 0.13 0.24 0.11

(0.03) (0.03)

3–5 0.14 0.21 0.07

(0.03) (0.04)

>5 0.05 0.08 0.03

(0.02) (0.04)

Years, conditional on any 3.52 3.34 −0.18

(0.47) (0.54)

Skill requirements

Any stated skills 0.73 0.91 0.18

(0.05) (0.04)

Cognitive, conditional on any 0.22 0.34 0.11

(0.05) (0.06)

Computer, conditional on any 0.28 0.39 0.11

(0.06) (0.08)

Panel B. Share of ads in 2010–2015 matching to 2007 and to other datasets

Missing ACS match 0.08

Continuing firm 0.65

In Harte-Hanks, among continuing 0.78

In Compustat, among continuing 0.40

Mean Min Max

Panel C. Cell counts

Number MSAs 381

Posts per MSA-year 21,779 132 1,231,417

Number occupations ( four-digit) 108

Posts per occupation-MSA-year 228 1 194,558

Number firms 170,809

Posts per Firm-MSA-year 13 1 16,413

Notes: Burning Glass data 2007 and 2010–2015. All changes are statistically significant at the

1 percent level. Sample is restricted to ads withnon-missing firms that posted at least ten ads

over our sample period. In the top panel, observations are weighted by the size of the MSA

labor force in 2006. Missing ACS match is the share of weighted observations to MSAs that

cannot be matched to the American Community Survey (weighted by the MSA labor force).

Continuing firms are the fraction of 2010–2015 observations posted by a firm that also posted

in 2007. In Harte Hanks (Compustat) among continuing firms are the share of weighted obser-

vations that post to a firm that can be matched to Harte Hanks (Compustat). All three statistics

are calculated weighting by the firm’s ad share in theMSA-year times the size of the MSA

labor force in 2006.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1746 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW JULY 2018

and the remainder are roughly evenly split between associate degrees (not sho

master’s degrees, and professional degrees or PhDs. Converting the degrees to

modal equivalent years of schooling, the average education requirement, cond

on one being specified, is nearly 15 years.

The second column shows skill requirements averaged over the period 2010

The third column shows the within-MSA change in skill requirements across th

two sample periods. The share of ads specifying an education requirement incr

by 23 percentage points (ppts), on average. This is roughly evenly split across

requiring high school and ads requiring college; because the proportional incre

is slightly larger for high school, the overall (conditional) years of schooling fall

slightly. All differences in means are statistically significant at the 1 percent lev

Experience requirements follow a very similar pattern to education requirem

In 2007, almost one-third of ads specify some amount of experience in the fiel

Among ads with a requirement, the vast majority ask for less than five years, w

much of the remainder asking for between 5 and 10 years. Conditional on post

experience requirement, the average ad asks for 3.5 years. In the later time pe

the propensity to specify an experience requirement increases by 20 ppts. The

increases are again concentrated in the lower categories, so that the average,

tional on specifying any requirement, falls by about one-fifth of a year.

Finally, in 2007, 73 percent of weighted ads specify at least one specific, tex

skill requirement. Among these, 22 percent specify a cognitive skill requiremen

and 28 percent have a computer requirement. In 2010–2015, 91 percent

have at least one text-based skill requirement, and the shares specifying cogn

skills or computer skills increase to roughly one-third and two-fifths, respectiv

In regression analyses, we use the probability of posting a cognitive or comput

skill requirement, conditional on posting a specifictext-based skill, as dependent

variables, rather than the unconditional probabilities, which might instead pick

tendency for ads to become more verbose as posting costs decline.

These increases in stated skill demand could be driven by the nationa

sion that took place between 2007 and the 2010–2015 period. However, they c

also be driven by a variety of other factors, such as changing composition of fir

posting ads online orpreexisting national trends. Because of these issues and the

relatively short panel we have to work with, our regression analyses always con

for year dummies. We therefore fully absorb the overall change in skill requirem

illustrated in Table 1. Instead, we identify differences in the change in skill requ

ments across metro areas as a function of how they weathered the Great Rece

The bottom panel of Table 1 provides an idea of our sample coverage

have a balanced panel of 381 MSAs, which contain an (unweighted) average of

21,779 posts per MSA-year. When we disaggregate to the four-digit occu

level, we have 108 occupations represented, with an average of 228 posts in e

occupation-MSA-year.18 Finally, our data contain roughly 171,000 unique firms,

which translate into an average of 14 posts in each firm-MSA-year.

18Though occupation is available in the BG data at the six-digit Standard Occupation Classification (SOC)

level, we restrict our attention to comparisons across and within four-digit SOC codes, which provid

ads per occupation-MSA-year cell and ensure a balanced panel of occupation-MSAs across years in nearly a

cases. Virtually all ads posted in the 2010–2015 period are in occupation-MSAs that also posted in

within-occupation analyses, we drop the 0.36 percent of ads that cannot be matched.

and the remainder are roughly evenly split between associate degrees (not sho

master’s degrees, and professional degrees or PhDs. Converting the degrees to

modal equivalent years of schooling, the average education requirement, cond

on one being specified, is nearly 15 years.

The second column shows skill requirements averaged over the period 2010

The third column shows the within-MSA change in skill requirements across th

two sample periods. The share of ads specifying an education requirement incr

by 23 percentage points (ppts), on average. This is roughly evenly split across

requiring high school and ads requiring college; because the proportional incre

is slightly larger for high school, the overall (conditional) years of schooling fall

slightly. All differences in means are statistically significant at the 1 percent lev

Experience requirements follow a very similar pattern to education requirem

In 2007, almost one-third of ads specify some amount of experience in the fiel

Among ads with a requirement, the vast majority ask for less than five years, w

much of the remainder asking for between 5 and 10 years. Conditional on post

experience requirement, the average ad asks for 3.5 years. In the later time pe

the propensity to specify an experience requirement increases by 20 ppts. The

increases are again concentrated in the lower categories, so that the average,

tional on specifying any requirement, falls by about one-fifth of a year.

Finally, in 2007, 73 percent of weighted ads specify at least one specific, tex

skill requirement. Among these, 22 percent specify a cognitive skill requiremen

and 28 percent have a computer requirement. In 2010–2015, 91 percent

have at least one text-based skill requirement, and the shares specifying cogn

skills or computer skills increase to roughly one-third and two-fifths, respectiv

In regression analyses, we use the probability of posting a cognitive or comput

skill requirement, conditional on posting a specifictext-based skill, as dependent

variables, rather than the unconditional probabilities, which might instead pick

tendency for ads to become more verbose as posting costs decline.

These increases in stated skill demand could be driven by the nationa

sion that took place between 2007 and the 2010–2015 period. However, they c

also be driven by a variety of other factors, such as changing composition of fir

posting ads online orpreexisting national trends. Because of these issues and the

relatively short panel we have to work with, our regression analyses always con

for year dummies. We therefore fully absorb the overall change in skill requirem

illustrated in Table 1. Instead, we identify differences in the change in skill requ

ments across metro areas as a function of how they weathered the Great Rece

The bottom panel of Table 1 provides an idea of our sample coverage

have a balanced panel of 381 MSAs, which contain an (unweighted) average of

21,779 posts per MSA-year. When we disaggregate to the four-digit occu

level, we have 108 occupations represented, with an average of 228 posts in e

occupation-MSA-year.18 Finally, our data contain roughly 171,000 unique firms,

which translate into an average of 14 posts in each firm-MSA-year.

18Though occupation is available in the BG data at the six-digit Standard Occupation Classification (SOC)

level, we restrict our attention to comparisons across and within four-digit SOC codes, which provid

ads per occupation-MSA-year cell and ensure a balanced panel of occupation-MSAs across years in nearly a

cases. Virtually all ads posted in the 2010–2015 period are in occupation-MSAs that also posted in

within-occupation analyses, we drop the 0.36 percent of ads that cannot be matched.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1747HERSHBEIN AND KAHN: ROUTINE-BIASED TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGEVOL. 108 NO. 7

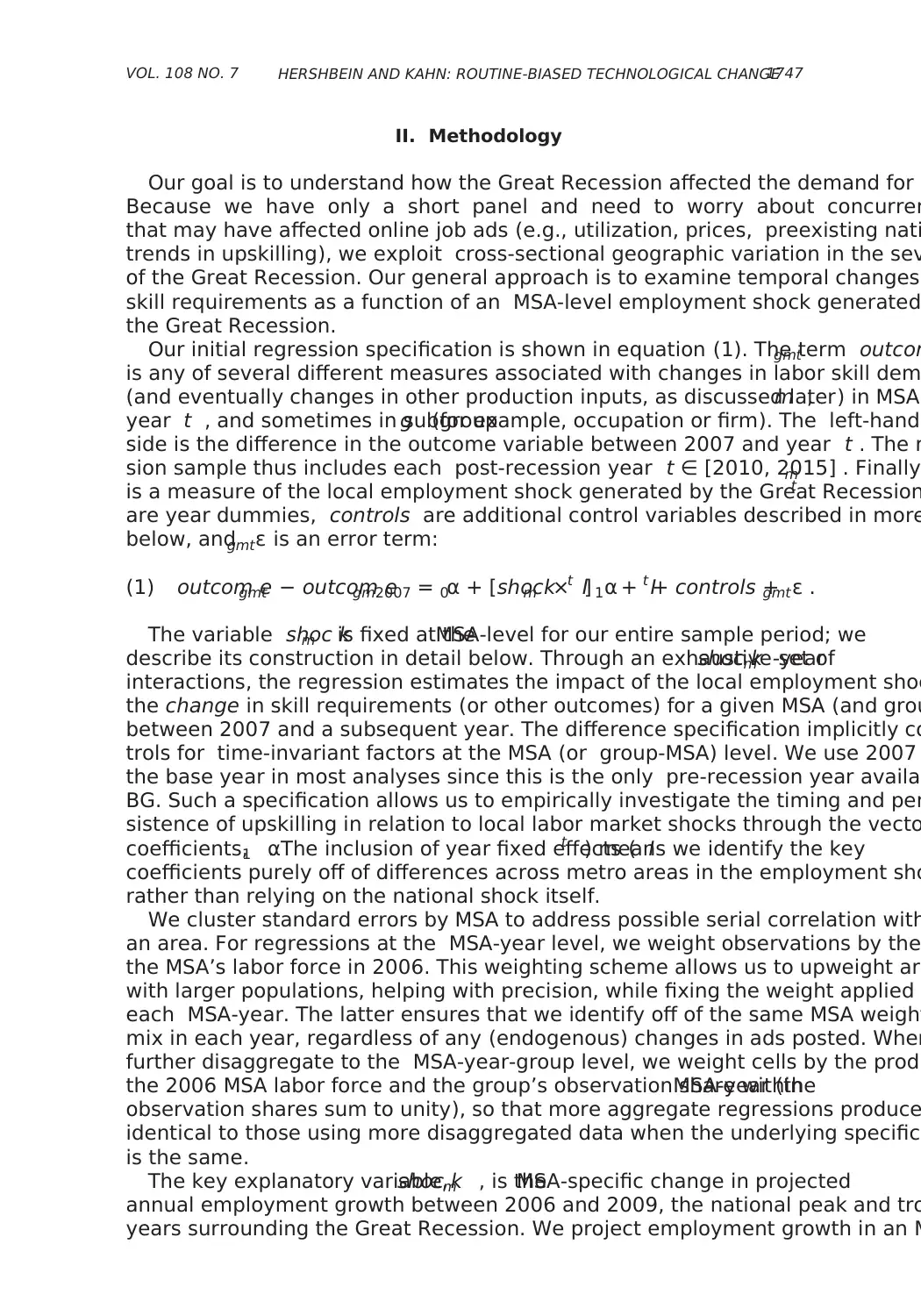

II. Methodology

Our goal is to understand how the Great Recession affected the demand for s

Because we have only a short panel and need to worry about concurren

that may have affected online job ads (e.g., utilization, prices, preexisting nati

trends in upskilling), we exploit cross-sectional geographic variation in the sev

of the Great Recession. Our general approach is to examine temporal changes

skill requirements as a function of an MSA-level employment shock generated

the Great Recession.

Our initial regression specification is shown in equation (1). The term outcomgmt

is any of several different measures associated with changes in labor skill dem

(and eventually changes in other production inputs, as discussed later) in MSAm ,