Team Development Interventions: Evidence-Based Approaches for Improving Teamwork

VerifiedAdded on 2022/12/28

|15

|15728

|28

AI Summary

This article provides a review of four types of evidence-based team development interventions (TDIs) including team training, leadership training, team building, and team debriefing. It aims to provide psychologists with an understanding of the scientific principles underlying TDIs and their impact on team dynamics.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Team Development Interventions: Evidence-Based Approaches for

Improving Teamwork

Christina N. Lacerenza

University of Colorado Boulder

Shannon L. Marlow

Rice University

Scott I. Tannenbaum

The Group for Organizational Effectiveness, Inc.,

Albany, New York

Eduardo Salas

Rice University

The rate of teamwork and collaboration within the workforce has burgeoned over the years,

and the use of teams is projected to continue increasing. With the rise of teamwork comes the

need for interventions designed to enhance teamwork effectiveness. Successful teams pro-

duce desired outcomes; however, it is critical that team members demonstrate effective

processes to achieve these outcomes. Team development interventions (TDIs) increase

effective team competencies and processes, thereby leading to improvements in proximal and

distal outcomes. The effectiveness of TDIs is evident across domains (e.g., education, health

care, military, aviation), and they are applicable in a wide range of settings. To stimulate the

adoption and effective use of TDIs, the current article provides a review of four types of

evidence-based TDIs including team training, leadership training, team building, and team

debriefing. In doing so, we aim to provide psychologists with an understanding of the

scientific principles underlying TDIs and their impact on team dynamics. Moreover, we

provide evidence-based recommendations regarding how to increase the effectiveness of

TDIs as well as a discussion on future research needed within this domain.

Keywords: teams, team training, team debriefing, leadership training, team building

According to a recent survey conducted by Deloitte

across 130 countries and over 7,000 participants, the num-

ber one global workforce trend is teamwork (Kaplan, Dol-

lar, Melian, Van Durme, & Wong, 2016). Employees are

expected to work more collaboratively than ever before, and

according to Cross, Rebele, and Grant (2016), “collabora-

tion is taking over the workplace” (p. 4), with employees

and managers reporting at least a 50% increase in the

amount of time spent on team-related tasks. Specifically,

organizations are implementing networks of teams, whereby

projects are assigned to groups of individuals who work inter-

dependently, employ high levels of empowerment, communi-

cate freely, and either disband following project completion or

continue collaborating. The rise of teamwork spans industries,

including health care, science, engineering, and technology

(e.g.,Wuchty, Jones, & Uzzi, 2007). Teamwork is even critical

for successful space exploration as is evidenced by the recent

push for teamwork research to support a future Mars mission

(Salas, Tannenbaum, Kozlowski, Miller, Mathieu, & Vessey,

2015).

Effective teamwork allows teams to produce outcomes

greater than the sum of individual members’ contributions

(Stagl, Shawn Burke, & Pierce, 2006) and is driven by team

processes (i.e., “interdependent acts that convert inputs to

outcomes through cognitive, verbal, and behavioral activi-

ties directed toward organizing taskwork to achieve collec-

tive goals”; Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001, p. 357) and

emergent states (i.e., dynamic properties of the team that

vary depending upon various factors), both of which require

Editor’s note. This article is part of a special issue, “The Science of

Teamwork,” published in the May–June 2018 issue of American Psychol-

ogist. Susan H. McDaniel and Eduardo Salas served as guest editors of the

special issue, with Anne E. Kazak as advisory editor.

Authors’ note. Christina N. Lacerenza, Leeds School of Business, Uni-

versity of Colorado Boulder; Shannon L.Marlow,Department of Psychology,

Rice University; Scott I. Tannenbaum, The Group for Organizational Effective-

ness, Inc., Albany, New York; Eduardo Salas, Department of Psychology, Rice

University.

This work was supported in part by contract 80NSSC18K0092 with the Na-

tional Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to the Group for Organi-

zational Effectiveness, contracts NNX16AP96G and NNX16AB08G with NASA

to Rice University, and research grants from the Ann and John Doerr Institute for

New Leaders at Rice University.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Eduardo

Salas, Department of Psychology, Rice University, 6100 Main Street,

Houston, TX 77005. E-mail: eduardo.salas@rice.edu

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

American Psychologist

© 2018 American Psychological Association 2018, Vol. 73, No. 4, 517–531

0003-066X/18/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000295

517

Improving Teamwork

Christina N. Lacerenza

University of Colorado Boulder

Shannon L. Marlow

Rice University

Scott I. Tannenbaum

The Group for Organizational Effectiveness, Inc.,

Albany, New York

Eduardo Salas

Rice University

The rate of teamwork and collaboration within the workforce has burgeoned over the years,

and the use of teams is projected to continue increasing. With the rise of teamwork comes the

need for interventions designed to enhance teamwork effectiveness. Successful teams pro-

duce desired outcomes; however, it is critical that team members demonstrate effective

processes to achieve these outcomes. Team development interventions (TDIs) increase

effective team competencies and processes, thereby leading to improvements in proximal and

distal outcomes. The effectiveness of TDIs is evident across domains (e.g., education, health

care, military, aviation), and they are applicable in a wide range of settings. To stimulate the

adoption and effective use of TDIs, the current article provides a review of four types of

evidence-based TDIs including team training, leadership training, team building, and team

debriefing. In doing so, we aim to provide psychologists with an understanding of the

scientific principles underlying TDIs and their impact on team dynamics. Moreover, we

provide evidence-based recommendations regarding how to increase the effectiveness of

TDIs as well as a discussion on future research needed within this domain.

Keywords: teams, team training, team debriefing, leadership training, team building

According to a recent survey conducted by Deloitte

across 130 countries and over 7,000 participants, the num-

ber one global workforce trend is teamwork (Kaplan, Dol-

lar, Melian, Van Durme, & Wong, 2016). Employees are

expected to work more collaboratively than ever before, and

according to Cross, Rebele, and Grant (2016), “collabora-

tion is taking over the workplace” (p. 4), with employees

and managers reporting at least a 50% increase in the

amount of time spent on team-related tasks. Specifically,

organizations are implementing networks of teams, whereby

projects are assigned to groups of individuals who work inter-

dependently, employ high levels of empowerment, communi-

cate freely, and either disband following project completion or

continue collaborating. The rise of teamwork spans industries,

including health care, science, engineering, and technology

(e.g.,Wuchty, Jones, & Uzzi, 2007). Teamwork is even critical

for successful space exploration as is evidenced by the recent

push for teamwork research to support a future Mars mission

(Salas, Tannenbaum, Kozlowski, Miller, Mathieu, & Vessey,

2015).

Effective teamwork allows teams to produce outcomes

greater than the sum of individual members’ contributions

(Stagl, Shawn Burke, & Pierce, 2006) and is driven by team

processes (i.e., “interdependent acts that convert inputs to

outcomes through cognitive, verbal, and behavioral activi-

ties directed toward organizing taskwork to achieve collec-

tive goals”; Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001, p. 357) and

emergent states (i.e., dynamic properties of the team that

vary depending upon various factors), both of which require

Editor’s note. This article is part of a special issue, “The Science of

Teamwork,” published in the May–June 2018 issue of American Psychol-

ogist. Susan H. McDaniel and Eduardo Salas served as guest editors of the

special issue, with Anne E. Kazak as advisory editor.

Authors’ note. Christina N. Lacerenza, Leeds School of Business, Uni-

versity of Colorado Boulder; Shannon L.Marlow,Department of Psychology,

Rice University; Scott I. Tannenbaum, The Group for Organizational Effective-

ness, Inc., Albany, New York; Eduardo Salas, Department of Psychology, Rice

University.

This work was supported in part by contract 80NSSC18K0092 with the Na-

tional Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to the Group for Organi-

zational Effectiveness, contracts NNX16AP96G and NNX16AB08G with NASA

to Rice University, and research grants from the Ann and John Doerr Institute for

New Leaders at Rice University.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Eduardo

Salas, Department of Psychology, Rice University, 6100 Main Street,

Houston, TX 77005. E-mail: eduardo.salas@rice.edu

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

American Psychologist

© 2018 American Psychological Association 2018, Vol. 73, No. 4, 517–531

0003-066X/18/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000295

517

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

task and team competencies. While taskwork competencies

are the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs) necessary to

achieve individual task performance, team competencies are

those KSAs critical for team members to interdependently

interact with one another effectively and in such a way that

leads to positive team-based outcomes (Salas, Rosen,

Burke, & Goodwin, 2009). Thus, in addition to exhibiting

individual-level expertise (i.e., taskwork competencies),

team members must also display expertise in teamwork (i.e.,

team competencies). A vast domain of team competencies

exists, with organizational scientists from both industry and

academia identifying those that are most critical to team

effectiveness. For example, for teams at Google, those most

critical include psychological safety and dependability

(among others; Rozovsky, 2015), while Salas and col-

leagues (2009) provide a general list of competencies rele-

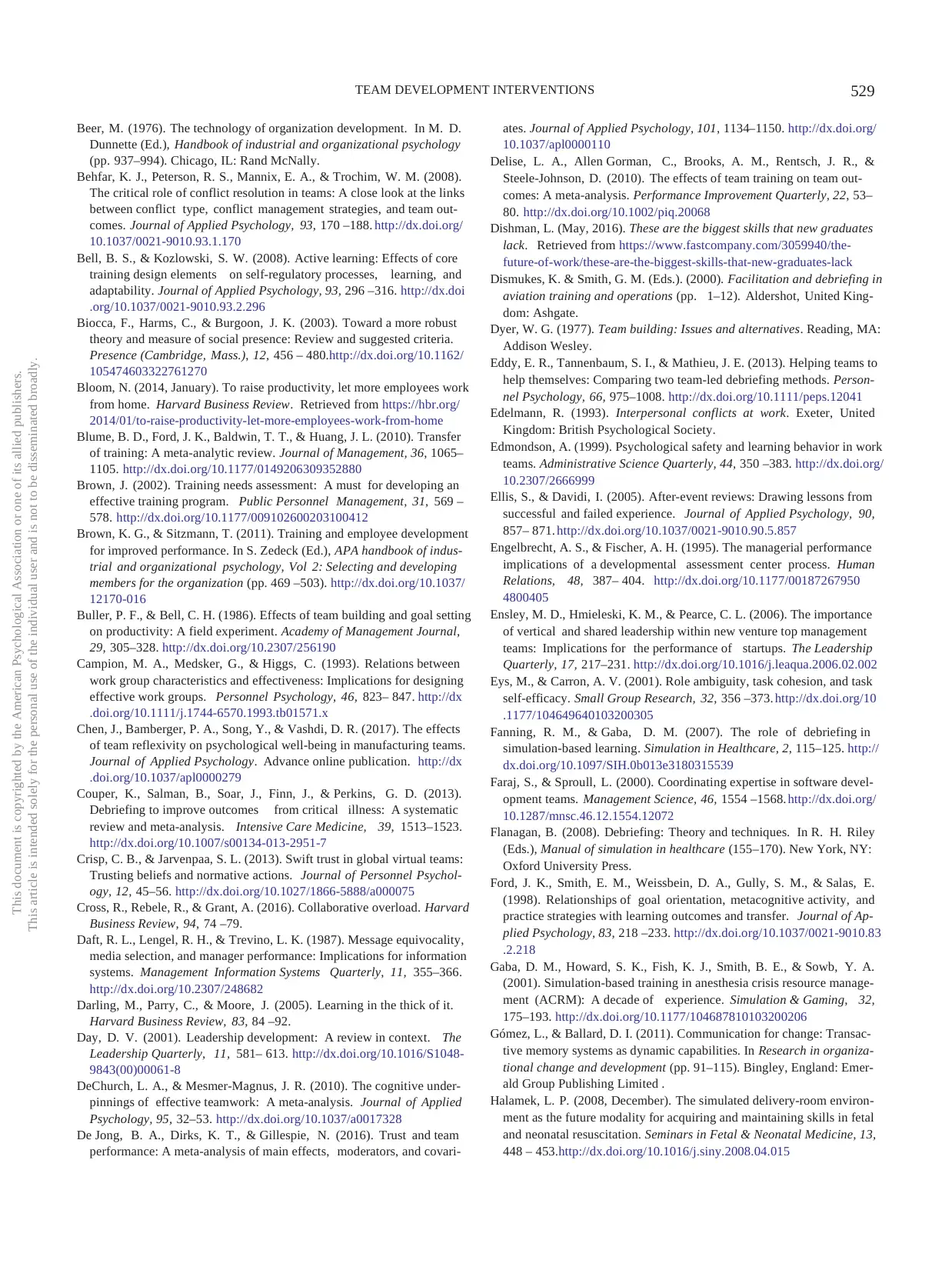

vant to teams across domains (see Figure 1 for a subset of

these competencies), which can be classified into three

broad categories (i.e., attitudes, behaviors, and cognitions).

Despite the increased expectations to work collabora-

tively and the benefits associated with effective teamwork,

companies continue to report a lack of team competencies

among their employees. According to a recent study con-

ducted by PayScale, 36% of recent graduates have deficient

team and interpersonal competencies (Dishman, 2016). Re-

latedly, companies also demonstrate the inability to manage

and arrange teams because only 21% of executives believe

their company holds expertise in designing cross-functional

teams (Kaplan et al., 2016). As such, there is a compelling

need to deploy psychologically sound, empirically tested

ways to boost effective teamwork, and, more specifically,

team competencies (e.g., adaptability, team orientation; Salas,

Sims, & Burke, 2005), team processes (e.g., mission anal-

ysis, team monitoring, and backup behavior; Marks et al.,

2001), interpersonal processes (e.g., conflict resolution,

trust development; Shuffler, DiazGranados, & Salas, 2011),

and leadership capabilities (e.g., intrapersonal skills, busi-

ness skills; Hogan & Warrenfeltz, 2003).

One way to improve teamwork is through the implemen-

tation of team development interventions (TDIs; Shuffler et

al., 2011). We define a TDI as a systematic activity aimed

at improving requisite team competencies, processes, and

overall effectiveness. There are multiple types of TDIs that

are used in organizations across industries. Although TDIs

may differ in terms of content focus, the intent of each is

similar, to improve team effectiveness in order to enhance

Christina N.

Lacerenza

Figure 1. Team competencies: Attitudes, behaviors, and cognitions. This figure provides a subset of evidence-

based team competencies.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

518 LACERENZA, MARLOW, TANNENBAUM, AND SALAS

are the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs) necessary to

achieve individual task performance, team competencies are

those KSAs critical for team members to interdependently

interact with one another effectively and in such a way that

leads to positive team-based outcomes (Salas, Rosen,

Burke, & Goodwin, 2009). Thus, in addition to exhibiting

individual-level expertise (i.e., taskwork competencies),

team members must also display expertise in teamwork (i.e.,

team competencies). A vast domain of team competencies

exists, with organizational scientists from both industry and

academia identifying those that are most critical to team

effectiveness. For example, for teams at Google, those most

critical include psychological safety and dependability

(among others; Rozovsky, 2015), while Salas and col-

leagues (2009) provide a general list of competencies rele-

vant to teams across domains (see Figure 1 for a subset of

these competencies), which can be classified into three

broad categories (i.e., attitudes, behaviors, and cognitions).

Despite the increased expectations to work collabora-

tively and the benefits associated with effective teamwork,

companies continue to report a lack of team competencies

among their employees. According to a recent study con-

ducted by PayScale, 36% of recent graduates have deficient

team and interpersonal competencies (Dishman, 2016). Re-

latedly, companies also demonstrate the inability to manage

and arrange teams because only 21% of executives believe

their company holds expertise in designing cross-functional

teams (Kaplan et al., 2016). As such, there is a compelling

need to deploy psychologically sound, empirically tested

ways to boost effective teamwork, and, more specifically,

team competencies (e.g., adaptability, team orientation; Salas,

Sims, & Burke, 2005), team processes (e.g., mission anal-

ysis, team monitoring, and backup behavior; Marks et al.,

2001), interpersonal processes (e.g., conflict resolution,

trust development; Shuffler, DiazGranados, & Salas, 2011),

and leadership capabilities (e.g., intrapersonal skills, busi-

ness skills; Hogan & Warrenfeltz, 2003).

One way to improve teamwork is through the implemen-

tation of team development interventions (TDIs; Shuffler et

al., 2011). We define a TDI as a systematic activity aimed

at improving requisite team competencies, processes, and

overall effectiveness. There are multiple types of TDIs that

are used in organizations across industries. Although TDIs

may differ in terms of content focus, the intent of each is

similar, to improve team effectiveness in order to enhance

Christina N.

Lacerenza

Figure 1. Team competencies: Attitudes, behaviors, and cognitions. This figure provides a subset of evidence-

based team competencies.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

518 LACERENZA, MARLOW, TANNENBAUM, AND SALAS

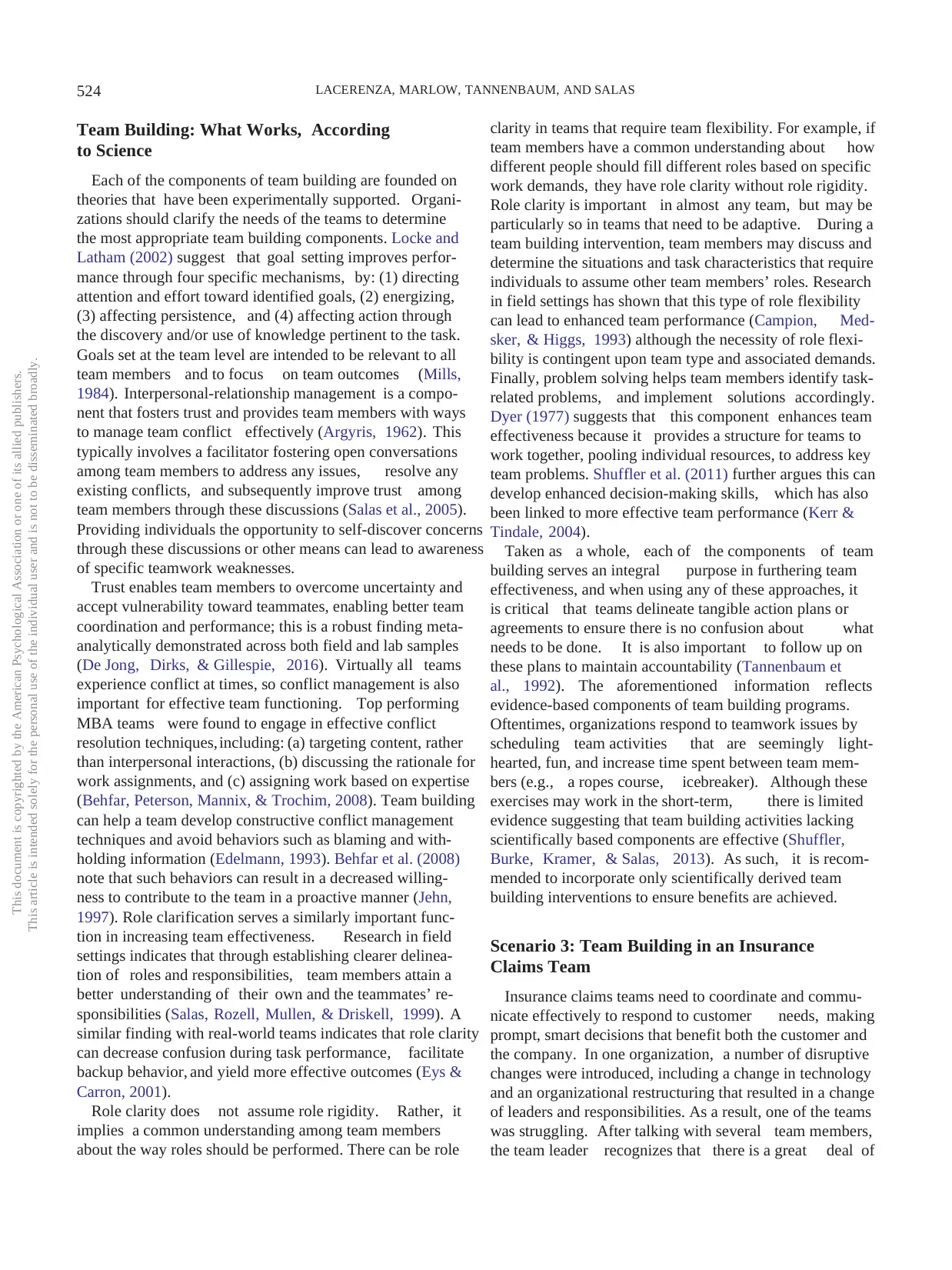

results—and meta-analytic and empirical evidence suggest

they do so successfully across proximal (e.g., team perfor-

mance; Salas, Nichols, & Driskell, 2007) and distal (e.g.,

reduction in patient deaths; Hughes et al., 2016) outcomes.

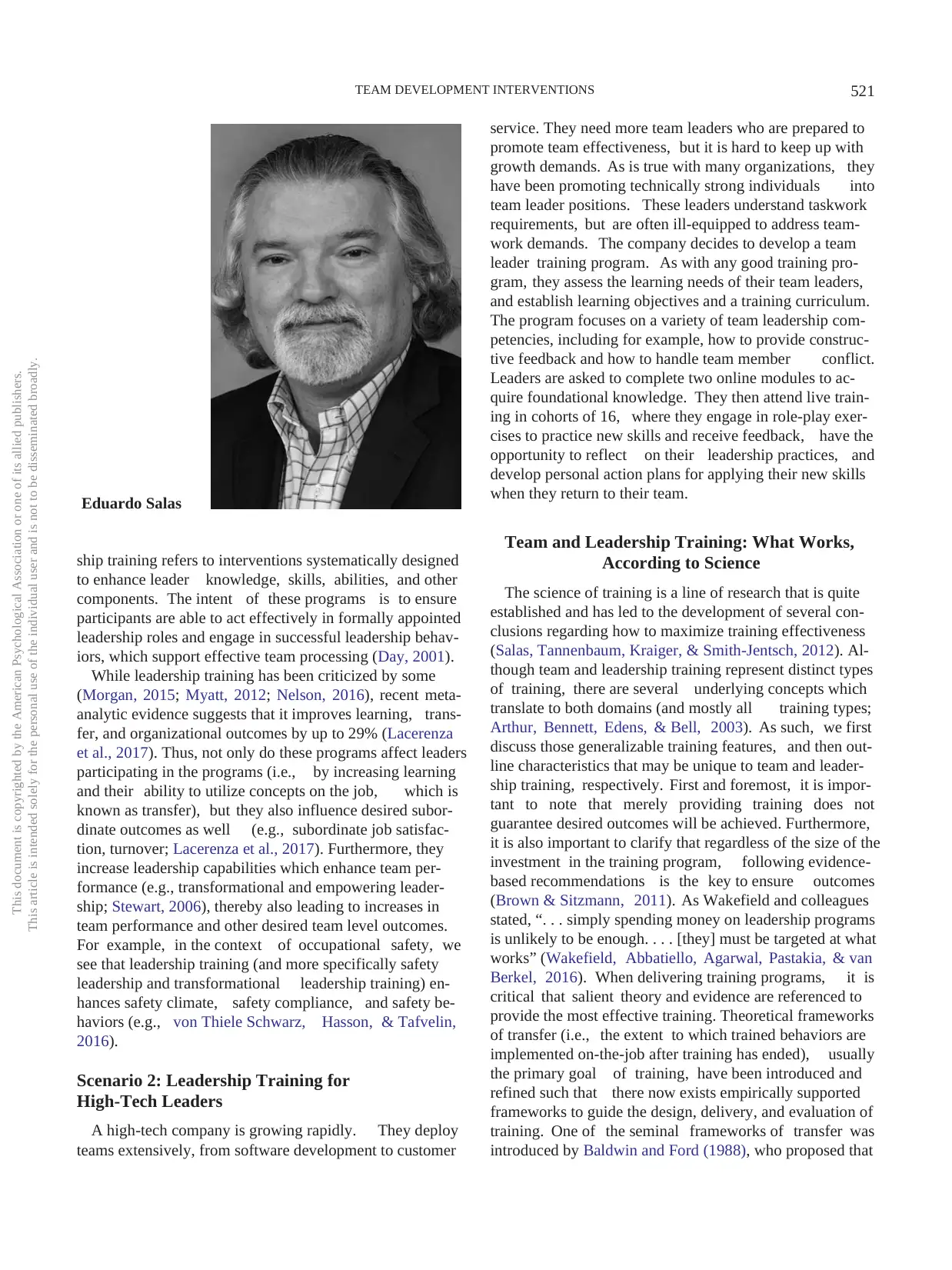

In the current article, we identify four major types of TDIs

and synthesize scientific evidence supporting the use of each

intervention type. In doing so, we aim to provide psychologists

with an understanding of the scientific principles and evidence

underlying TDIs. The four types of TDIs presented are (1)

team training, (2) leadership training, (3) team building, and

(4) team debriefing. We selected these TDIs because each has

ample theoretical and empirical evidence in support of its

efficacy and because each intervention serves a distinct pur-

pose. Although previous reviews have focused on one (e.g.,

team building; Klein et al., 2009) or two (e.g., team building

and team training; Shuffler et al., 2011) types of TDIs, we

include the aforementioned four to provide readers with an

understanding of the range of interventions and how and why

they work.1 All four can be effective, but they serve different

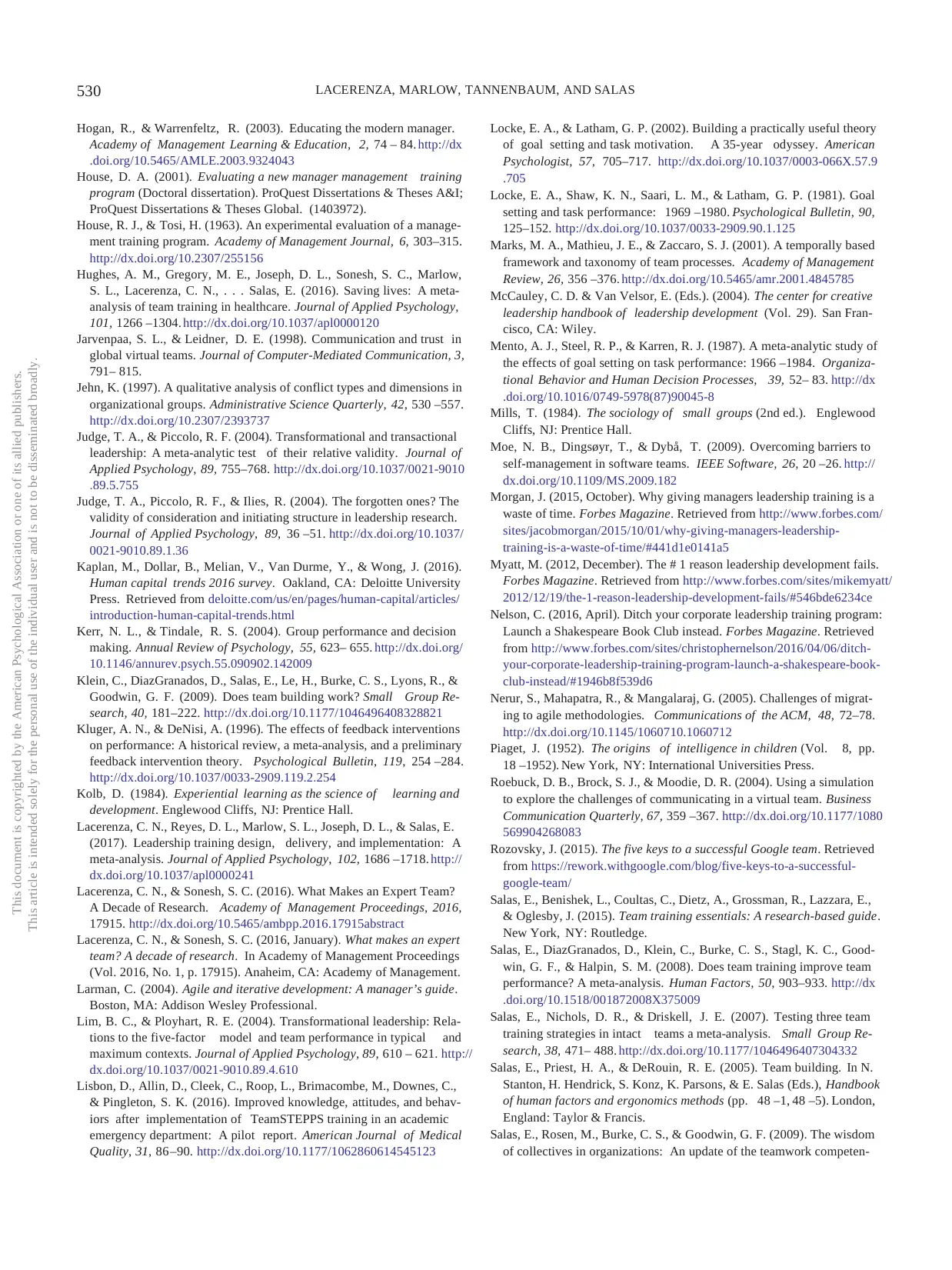

purposes and are designed differently (as identified in Figure

2). We note there to be two main categories of TDIs, training

interventions and process interventions. These TDIs can be

further distinguished by identifying who is attending the train-

ing program, either a leader (i.e., individual), or team members

belonging to a team that is either intact (i.e., a team with fairly

stable membership and shared work experience with each

other) or ad hoc (i.e., a team with individuals lacking a history

of working together). Generally, process interventions are de-

signed for intact teams, while training interventions can be for

leaders, ad hoc, or intact teams. As such, it is not our intention

to promote the use of one TDI over the other; rather, our goal

is to identify the conditions under which each strategy is most

effective and to highlight the main goal of each.2 In the

following sections, we define each TDI, highlight evidence in

support of their success, and synthesize scientific findings

regarding boundary conditions and influences on their effec-

tiveness. We also describe four scenarios to provide the reader

with a sense of the way in which each TDI tends to work in

practice. These scenarios are based, in part, on the authors’

experiences.

Improving Team Competencies:

Team Training

Team training is a formalized, structured learning experience

with preset objectives and curriculum that target specific team

competencies. Furthermore, this intervention improves team

processes by improving these competencies and is argued to

foster enhanced teamwork by promoting improvement in spe-

cific teamwork skills linked to team performance (Salas et al.,

2008). Team training has been implemented across industries

(e.g., engineering, education, health care; Salas et al., 2008) as

science suggests its effectiveness across various outcomes

(e.g., team communication, patient deaths; Hughes et al.,

2016). Because of the strong empirical support for team train-

ing, we are seeing a rise in the implementation of these pro-

grams across health care settings nationwide to reduce the

amount of medical errors caused by teamwork failures (e.g.,

Weaver, Dy, & Rosen, 2014). For example, the Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, which is housed in

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) invested

in the development and dissemination of Team Strategies and

Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (Team-

STEPPS; AHRQ, 2017), which is a team training program

consisting of case studies and web-based tools. This program

has been used across health care institutions and is customiz-

able (as evidenced by Lisbon et al. [2016], who implemented

a version that entailed video vignettes, group discussion, and

informational modules). In addition to health care, team train-

ing has also been circulated within the education domain; for

example, CATME (the Comprehensive Assessment of Team

Member Effectiveness) was developed to assist student engi-

neering teams with their team effectiveness and consists of

web-based tools, teamwork evaluation metrics,and other re-

lated instruments (see info.catme.org for more information).

These examples represent a few of many approaches to team

training. Many team training programs have been created,

there are many different tools available to facilitate them, and

there is ample evidence supporting their effectiveness across

1 Although the current framework is nested within the teams literature,

it is important to note that it is not necessarily comprehensive and other

modes of organizing the team development intervention literature may

exist.

2 Although these four TDIs can be used for multiple purposes (e.g., team

training can include interpersonal content), the current paper focuses on the

primary purpose of each TDI type for sake of parsimony.

Shannon L.

Marlow

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

519TEAM DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTIONS

they do so successfully across proximal (e.g., team perfor-

mance; Salas, Nichols, & Driskell, 2007) and distal (e.g.,

reduction in patient deaths; Hughes et al., 2016) outcomes.

In the current article, we identify four major types of TDIs

and synthesize scientific evidence supporting the use of each

intervention type. In doing so, we aim to provide psychologists

with an understanding of the scientific principles and evidence

underlying TDIs. The four types of TDIs presented are (1)

team training, (2) leadership training, (3) team building, and

(4) team debriefing. We selected these TDIs because each has

ample theoretical and empirical evidence in support of its

efficacy and because each intervention serves a distinct pur-

pose. Although previous reviews have focused on one (e.g.,

team building; Klein et al., 2009) or two (e.g., team building

and team training; Shuffler et al., 2011) types of TDIs, we

include the aforementioned four to provide readers with an

understanding of the range of interventions and how and why

they work.1 All four can be effective, but they serve different

purposes and are designed differently (as identified in Figure

2). We note there to be two main categories of TDIs, training

interventions and process interventions. These TDIs can be

further distinguished by identifying who is attending the train-

ing program, either a leader (i.e., individual), or team members

belonging to a team that is either intact (i.e., a team with fairly

stable membership and shared work experience with each

other) or ad hoc (i.e., a team with individuals lacking a history

of working together). Generally, process interventions are de-

signed for intact teams, while training interventions can be for

leaders, ad hoc, or intact teams. As such, it is not our intention

to promote the use of one TDI over the other; rather, our goal

is to identify the conditions under which each strategy is most

effective and to highlight the main goal of each.2 In the

following sections, we define each TDI, highlight evidence in

support of their success, and synthesize scientific findings

regarding boundary conditions and influences on their effec-

tiveness. We also describe four scenarios to provide the reader

with a sense of the way in which each TDI tends to work in

practice. These scenarios are based, in part, on the authors’

experiences.

Improving Team Competencies:

Team Training

Team training is a formalized, structured learning experience

with preset objectives and curriculum that target specific team

competencies. Furthermore, this intervention improves team

processes by improving these competencies and is argued to

foster enhanced teamwork by promoting improvement in spe-

cific teamwork skills linked to team performance (Salas et al.,

2008). Team training has been implemented across industries

(e.g., engineering, education, health care; Salas et al., 2008) as

science suggests its effectiveness across various outcomes

(e.g., team communication, patient deaths; Hughes et al.,

2016). Because of the strong empirical support for team train-

ing, we are seeing a rise in the implementation of these pro-

grams across health care settings nationwide to reduce the

amount of medical errors caused by teamwork failures (e.g.,

Weaver, Dy, & Rosen, 2014). For example, the Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, which is housed in

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) invested

in the development and dissemination of Team Strategies and

Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (Team-

STEPPS; AHRQ, 2017), which is a team training program

consisting of case studies and web-based tools. This program

has been used across health care institutions and is customiz-

able (as evidenced by Lisbon et al. [2016], who implemented

a version that entailed video vignettes, group discussion, and

informational modules). In addition to health care, team train-

ing has also been circulated within the education domain; for

example, CATME (the Comprehensive Assessment of Team

Member Effectiveness) was developed to assist student engi-

neering teams with their team effectiveness and consists of

web-based tools, teamwork evaluation metrics,and other re-

lated instruments (see info.catme.org for more information).

These examples represent a few of many approaches to team

training. Many team training programs have been created,

there are many different tools available to facilitate them, and

there is ample evidence supporting their effectiveness across

1 Although the current framework is nested within the teams literature,

it is important to note that it is not necessarily comprehensive and other

modes of organizing the team development intervention literature may

exist.

2 Although these four TDIs can be used for multiple purposes (e.g., team

training can include interpersonal content), the current paper focuses on the

primary purpose of each TDI type for sake of parsimony.

Shannon L.

Marlow

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

519TEAM DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTIONS

affective, cognitive, and performance-based outcomes at all

levels (i.e., individual, team, organization; Delise, Allen Gor-

man, Brooks, Rentsch, & Steele-Johnson, 2010; Hughes et al.,

2016; Salas et al., 2007; 2008).

Scenario 1: Team Training for Surgical Teams

A hospital has an active, high-volume surgical center. Sur-

geries are performed by teams (e.g., surgeon, anesthesiologist,

nurse, tech) that must coordinate to provide safe, effective care.

They discover that teamwork breakdowns are a primary cause

of surgical errors. Because team membership changes from

surgery to surgery, it is very difficult to intervene at the intact

team level, so they decide to conduct team training that focuses on

transportable competencies that individuals can deploy during any

surgery. They conduct a training needs analysis and discover that

the most critical competencies are related to communication and

mutual monitoring skills, including being alert for potential mis-

takes, speaking up regardless of seniority, communicating us-

ing standard language, and ensuring messages are accurately

received (“closed-loop” communication). Using good instruc-

tional design principles, they develop learning objectives and a

training curriculum that includes exercises (role-plays and sim-

ulated surgery) that allow the participants to practice and

receive feedback on their communication and mutual monitor-

ing skills. Follow-up shows that participants have acquired

competencies they can apply during any surgery.

Improving Leader Capabilities: Leadership Training

Heredity explains roughly 30% of the variance in leader-

ship, while diverse experiences, training, and other factors

are responsible for the remaining 70% (Arvey, Rotundo,

Johnson, Zhang, & McGue, 2006). This suggests that indi-

vidual leadership capabilities can be improved, particularly

with well-designed leadership training programs, and meta-

analytic evidence supports this claim (Lacerenza, Reyes,

Marlow, Joseph, & Salas, 2017). Because leaders are an

essential element to teams (Salas, Priest, & DeRouin, 2005),

leadership training is an important TDI to discuss. Leader-

Scott I.

Tannenbaum

Figure 2. Team development interventions. This figure illustrates the four methods of team development

interventions.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

520 LACERENZA, MARLOW, TANNENBAUM, AND SALAS

levels (i.e., individual, team, organization; Delise, Allen Gor-

man, Brooks, Rentsch, & Steele-Johnson, 2010; Hughes et al.,

2016; Salas et al., 2007; 2008).

Scenario 1: Team Training for Surgical Teams

A hospital has an active, high-volume surgical center. Sur-

geries are performed by teams (e.g., surgeon, anesthesiologist,

nurse, tech) that must coordinate to provide safe, effective care.

They discover that teamwork breakdowns are a primary cause

of surgical errors. Because team membership changes from

surgery to surgery, it is very difficult to intervene at the intact

team level, so they decide to conduct team training that focuses on

transportable competencies that individuals can deploy during any

surgery. They conduct a training needs analysis and discover that

the most critical competencies are related to communication and

mutual monitoring skills, including being alert for potential mis-

takes, speaking up regardless of seniority, communicating us-

ing standard language, and ensuring messages are accurately

received (“closed-loop” communication). Using good instruc-

tional design principles, they develop learning objectives and a

training curriculum that includes exercises (role-plays and sim-

ulated surgery) that allow the participants to practice and

receive feedback on their communication and mutual monitor-

ing skills. Follow-up shows that participants have acquired

competencies they can apply during any surgery.

Improving Leader Capabilities: Leadership Training

Heredity explains roughly 30% of the variance in leader-

ship, while diverse experiences, training, and other factors

are responsible for the remaining 70% (Arvey, Rotundo,

Johnson, Zhang, & McGue, 2006). This suggests that indi-

vidual leadership capabilities can be improved, particularly

with well-designed leadership training programs, and meta-

analytic evidence supports this claim (Lacerenza, Reyes,

Marlow, Joseph, & Salas, 2017). Because leaders are an

essential element to teams (Salas, Priest, & DeRouin, 2005),

leadership training is an important TDI to discuss. Leader-

Scott I.

Tannenbaum

Figure 2. Team development interventions. This figure illustrates the four methods of team development

interventions.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

520 LACERENZA, MARLOW, TANNENBAUM, AND SALAS

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

ship training refers to interventions systematically designed

to enhance leader knowledge, skills, abilities, and other

components. The intent of these programs is to ensure

participants are able to act effectively in formally appointed

leadership roles and engage in successful leadership behav-

iors, which support effective team processing (Day, 2001).

While leadership training has been criticized by some

(Morgan, 2015; Myatt, 2012; Nelson, 2016), recent meta-

analytic evidence suggests that it improves learning, trans-

fer, and organizational outcomes by up to 29% (Lacerenza

et al., 2017). Thus, not only do these programs affect leaders

participating in the programs (i.e., by increasing learning

and their ability to utilize concepts on the job, which is

known as transfer), but they also influence desired subor-

dinate outcomes as well (e.g., subordinate job satisfac-

tion, turnover; Lacerenza et al., 2017). Furthermore, they

increase leadership capabilities which enhance team per-

formance (e.g., transformational and empowering leader-

ship; Stewart, 2006), thereby also leading to increases in

team performance and other desired team level outcomes.

For example, in the context of occupational safety, we

see that leadership training (and more specifically safety

leadership and transformational leadership training) en-

hances safety climate, safety compliance, and safety be-

haviors (e.g., von Thiele Schwarz, Hasson, & Tafvelin,

2016).

Scenario 2: Leadership Training for

High-Tech Leaders

A high-tech company is growing rapidly. They deploy

teams extensively, from software development to customer

service. They need more team leaders who are prepared to

promote team effectiveness, but it is hard to keep up with

growth demands. As is true with many organizations, they

have been promoting technically strong individuals into

team leader positions. These leaders understand taskwork

requirements, but are often ill-equipped to address team-

work demands. The company decides to develop a team

leader training program. As with any good training pro-

gram, they assess the learning needs of their team leaders,

and establish learning objectives and a training curriculum.

The program focuses on a variety of team leadership com-

petencies, including for example, how to provide construc-

tive feedback and how to handle team member conflict.

Leaders are asked to complete two online modules to ac-

quire foundational knowledge. They then attend live train-

ing in cohorts of 16, where they engage in role-play exer-

cises to practice new skills and receive feedback, have the

opportunity to reflect on their leadership practices, and

develop personal action plans for applying their new skills

when they return to their team.

Team and Leadership Training: What Works,

According to Science

The science of training is a line of research that is quite

established and has led to the development of several con-

clusions regarding how to maximize training effectiveness

(Salas, Tannenbaum, Kraiger, & Smith-Jentsch, 2012). Al-

though team and leadership training represent distinct types

of training, there are several underlying concepts which

translate to both domains (and mostly all training types;

Arthur, Bennett, Edens, & Bell, 2003). As such, we first

discuss those generalizable training features, and then out-

line characteristics that may be unique to team and leader-

ship training, respectively. First and foremost, it is impor-

tant to note that merely providing training does not

guarantee desired outcomes will be achieved. Furthermore,

it is also important to clarify that regardless of the size of the

investment in the training program, following evidence-

based recommendations is the key to ensure outcomes

(Brown & Sitzmann, 2011). As Wakefield and colleagues

stated, “. . . simply spending money on leadership programs

is unlikely to be enough. . . . [they] must be targeted at what

works” (Wakefield, Abbatiello, Agarwal, Pastakia, & van

Berkel, 2016). When delivering training programs, it is

critical that salient theory and evidence are referenced to

provide the most effective training. Theoretical frameworks

of transfer (i.e., the extent to which trained behaviors are

implemented on-the-job after training has ended), usually

the primary goal of training, have been introduced and

refined such that there now exists empirically supported

frameworks to guide the design, delivery, and evaluation of

training. One of the seminal frameworks of transfer was

introduced by Baldwin and Ford (1988), who proposed that

Eduardo Salas

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

521TEAM DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTIONS

to enhance leader knowledge, skills, abilities, and other

components. The intent of these programs is to ensure

participants are able to act effectively in formally appointed

leadership roles and engage in successful leadership behav-

iors, which support effective team processing (Day, 2001).

While leadership training has been criticized by some

(Morgan, 2015; Myatt, 2012; Nelson, 2016), recent meta-

analytic evidence suggests that it improves learning, trans-

fer, and organizational outcomes by up to 29% (Lacerenza

et al., 2017). Thus, not only do these programs affect leaders

participating in the programs (i.e., by increasing learning

and their ability to utilize concepts on the job, which is

known as transfer), but they also influence desired subor-

dinate outcomes as well (e.g., subordinate job satisfac-

tion, turnover; Lacerenza et al., 2017). Furthermore, they

increase leadership capabilities which enhance team per-

formance (e.g., transformational and empowering leader-

ship; Stewart, 2006), thereby also leading to increases in

team performance and other desired team level outcomes.

For example, in the context of occupational safety, we

see that leadership training (and more specifically safety

leadership and transformational leadership training) en-

hances safety climate, safety compliance, and safety be-

haviors (e.g., von Thiele Schwarz, Hasson, & Tafvelin,

2016).

Scenario 2: Leadership Training for

High-Tech Leaders

A high-tech company is growing rapidly. They deploy

teams extensively, from software development to customer

service. They need more team leaders who are prepared to

promote team effectiveness, but it is hard to keep up with

growth demands. As is true with many organizations, they

have been promoting technically strong individuals into

team leader positions. These leaders understand taskwork

requirements, but are often ill-equipped to address team-

work demands. The company decides to develop a team

leader training program. As with any good training pro-

gram, they assess the learning needs of their team leaders,

and establish learning objectives and a training curriculum.

The program focuses on a variety of team leadership com-

petencies, including for example, how to provide construc-

tive feedback and how to handle team member conflict.

Leaders are asked to complete two online modules to ac-

quire foundational knowledge. They then attend live train-

ing in cohorts of 16, where they engage in role-play exer-

cises to practice new skills and receive feedback, have the

opportunity to reflect on their leadership practices, and

develop personal action plans for applying their new skills

when they return to their team.

Team and Leadership Training: What Works,

According to Science

The science of training is a line of research that is quite

established and has led to the development of several con-

clusions regarding how to maximize training effectiveness

(Salas, Tannenbaum, Kraiger, & Smith-Jentsch, 2012). Al-

though team and leadership training represent distinct types

of training, there are several underlying concepts which

translate to both domains (and mostly all training types;

Arthur, Bennett, Edens, & Bell, 2003). As such, we first

discuss those generalizable training features, and then out-

line characteristics that may be unique to team and leader-

ship training, respectively. First and foremost, it is impor-

tant to note that merely providing training does not

guarantee desired outcomes will be achieved. Furthermore,

it is also important to clarify that regardless of the size of the

investment in the training program, following evidence-

based recommendations is the key to ensure outcomes

(Brown & Sitzmann, 2011). As Wakefield and colleagues

stated, “. . . simply spending money on leadership programs

is unlikely to be enough. . . . [they] must be targeted at what

works” (Wakefield, Abbatiello, Agarwal, Pastakia, & van

Berkel, 2016). When delivering training programs, it is

critical that salient theory and evidence are referenced to

provide the most effective training. Theoretical frameworks

of transfer (i.e., the extent to which trained behaviors are

implemented on-the-job after training has ended), usually

the primary goal of training, have been introduced and

refined such that there now exists empirically supported

frameworks to guide the design, delivery, and evaluation of

training. One of the seminal frameworks of transfer was

introduced by Baldwin and Ford (1988), who proposed that

Eduardo Salas

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

521TEAM DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTIONS

the extent to which learning transfers into on-the-job behav-

iors is influenced by: training design features (e.g., training

content), trainee characteristics (e.g., motivation), and char-

acteristics of the work environment (e.g., organizational

support). There is meta-analytic evidence to support Bald-

win and Ford’s (1988) model of transfer (Blume, Ford,

Baldwin, & Huang, 2010) and this model applies to the

context of team (e.g., Hughes et al., 2016) and leadership

training (Lacerenza et al., 2017).

An important step to be taken during the initial stages of

training development is that of a needs analysis. A needs

analysis reflects the “process of gathering data to determine

what training needs exist so that training can be developed

to help the organization accomplish its objectives” (Brown,

2002, p. 569). During this analysis, you identify elements

such as the teams that require training, the KSAs necessary

for effectively completing team tasks, organizational goals

and other elements of the environment that will affect

training success, and the KSAs required for effective team-

work (Brown, 2002). A needs analysis boosts training ef-

fectiveness via identifying gaps between the existing and

required skills and tailoring the training to address those

gaps (Brown, 2002). It also provides insight into whether

the organization will support training transfer. As an exam-

ple, House (2001) first conducted a thorough needs analysis,

including interviews and focus groups with stakeholders

(e.g., experienced managers) and a review of competitors’

leadership training procedures, before developing the lead-

ership training program. This process also provides an op-

portunity to ensure that the goals of training align with both

the needed skills of the trainees and the stakeholders’ ex-

pectations of training.

Delivery methods are another well-known element that

influences outcomes, and they can be categorized into three

overarching dimensions: information (e.g., lecture), demon-

stration (e.g., video), and practice (e.g., role play). Although

benefits exist for all three categories, research suggests the

most effective programs tend to include a mix of the three

(Salas et al., 2012). For example, in House’s (2001) lead-

ership training program for employees of a high technology

company, the program included lectures, discussion, role

play, case studies, and other exercises; the program ulti-

mately proved to be successful at improving key manage-

ment skills following training. Similarly, House and Tosi

(1963) implemented information- (i.e., discussions, lec-

tures, reading materials) and practice-based (i.e., on-the-job

training exercises) delivery methods in a leadership training

program with engineering managers that ultimately led to

transfer 18 months following training. By incorporating

multiple delivery methods, various learning methods can be

used (e.g., individuals are provided with opportunities to

practice leadership skills in addition to being exposed to the

underlying information as this enables them to actively

participate, reflect, and grow; McCauley & Van Velsor,

2004), and both passive and active learning benefits can be

achieved (Hughes et al., 2016; Zapp, 2001).

In addition to information, demonstration, and practice-

based delivery methods, research also supports the use of

feedback in both leadership and team training. When pos-

sible, trainees should receive diagnostic feedback as part of

their learning experience, whether it be following a role play

exercise, on-the-job training, or a related experience (e.g.,

Barling, Weber, & Kelloway, 1996). Feedback can improve

an individual’s awareness of strengths and weaknesses, and

provide him/her with information on how to self-correct

undesirable behavior (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). Lab- and

field-based research supports the effectiveness of feedback

(Engelbrecht & Fisher, 1995; Ford, Smith, Weissbein,

Gully, & Salas, 1998), and it is a commonly used design

feature in leadership (e.g., Abrell, Rowold, Weibler, &

Moenninghoff, 2011) and team training programs (Hughes

et al., 2016). For example, Engelbrecht and Fischer (1995)

provided managers with a feedback report including strengths,

weaknesses, and a developmental action plan during their

leadership training program; training participants were

rated higher than a control on various leadership skills

(e.g., problem resolution, managing information) a few

months following the training program. When imple-

menting feedback for developmental purposes, however,

it is important to frame the information as diagnostic

rather than evaluative (e.g., Kluger & DeNisi, 1996), to

help reduce reactance and increase acceptance.

Leadership Training

In addition to the aforementioned general guidelines,

there are several design and delivery characteristics specific

to leadership training. In particular, research suggests that

leadership training developers should pay close attention to

the desired outcome (e.g., organizational results, transfer,

learning) because leadership training programs may be

more effective for some than others. While leadership train-

ing typically shows positive results for affective learning

and affective transfer, they tend to be even stronger for

cognitive learning, cognitive transfer, skill-based learn-

ing, and skill-based transfer (Avolio, Reichard, Hannah,

Walumbwa, & Chan, 2009; Lacerenza et al., 2017). As

such, when designing a leadership training program, it

might be more beneficial to include (and evaluate) cog-

nitive and/or skill-based content. Relatedly, stakeholder

expectations should be managed to reflect these potential

differences (e.g., make them aware that effects might not

be as large for affective outcomes compared with skill-

based).

The desired outcome(s) should also be identified early on

during training development because the training design

should align with the coveted outcome. Specifically, content

included in the program (e.g., the skills trained) should

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

522 LACERENZA, MARLOW, TANNENBAUM, AND SALAS

iors is influenced by: training design features (e.g., training

content), trainee characteristics (e.g., motivation), and char-

acteristics of the work environment (e.g., organizational

support). There is meta-analytic evidence to support Bald-

win and Ford’s (1988) model of transfer (Blume, Ford,

Baldwin, & Huang, 2010) and this model applies to the

context of team (e.g., Hughes et al., 2016) and leadership

training (Lacerenza et al., 2017).

An important step to be taken during the initial stages of

training development is that of a needs analysis. A needs

analysis reflects the “process of gathering data to determine

what training needs exist so that training can be developed

to help the organization accomplish its objectives” (Brown,

2002, p. 569). During this analysis, you identify elements

such as the teams that require training, the KSAs necessary

for effectively completing team tasks, organizational goals

and other elements of the environment that will affect

training success, and the KSAs required for effective team-

work (Brown, 2002). A needs analysis boosts training ef-

fectiveness via identifying gaps between the existing and

required skills and tailoring the training to address those

gaps (Brown, 2002). It also provides insight into whether

the organization will support training transfer. As an exam-

ple, House (2001) first conducted a thorough needs analysis,

including interviews and focus groups with stakeholders

(e.g., experienced managers) and a review of competitors’

leadership training procedures, before developing the lead-

ership training program. This process also provides an op-

portunity to ensure that the goals of training align with both

the needed skills of the trainees and the stakeholders’ ex-

pectations of training.

Delivery methods are another well-known element that

influences outcomes, and they can be categorized into three

overarching dimensions: information (e.g., lecture), demon-

stration (e.g., video), and practice (e.g., role play). Although

benefits exist for all three categories, research suggests the

most effective programs tend to include a mix of the three

(Salas et al., 2012). For example, in House’s (2001) lead-

ership training program for employees of a high technology

company, the program included lectures, discussion, role

play, case studies, and other exercises; the program ulti-

mately proved to be successful at improving key manage-

ment skills following training. Similarly, House and Tosi

(1963) implemented information- (i.e., discussions, lec-

tures, reading materials) and practice-based (i.e., on-the-job

training exercises) delivery methods in a leadership training

program with engineering managers that ultimately led to

transfer 18 months following training. By incorporating

multiple delivery methods, various learning methods can be

used (e.g., individuals are provided with opportunities to

practice leadership skills in addition to being exposed to the

underlying information as this enables them to actively

participate, reflect, and grow; McCauley & Van Velsor,

2004), and both passive and active learning benefits can be

achieved (Hughes et al., 2016; Zapp, 2001).

In addition to information, demonstration, and practice-

based delivery methods, research also supports the use of

feedback in both leadership and team training. When pos-

sible, trainees should receive diagnostic feedback as part of

their learning experience, whether it be following a role play

exercise, on-the-job training, or a related experience (e.g.,

Barling, Weber, & Kelloway, 1996). Feedback can improve

an individual’s awareness of strengths and weaknesses, and

provide him/her with information on how to self-correct

undesirable behavior (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). Lab- and

field-based research supports the effectiveness of feedback

(Engelbrecht & Fisher, 1995; Ford, Smith, Weissbein,

Gully, & Salas, 1998), and it is a commonly used design

feature in leadership (e.g., Abrell, Rowold, Weibler, &

Moenninghoff, 2011) and team training programs (Hughes

et al., 2016). For example, Engelbrecht and Fischer (1995)

provided managers with a feedback report including strengths,

weaknesses, and a developmental action plan during their

leadership training program; training participants were

rated higher than a control on various leadership skills

(e.g., problem resolution, managing information) a few

months following the training program. When imple-

menting feedback for developmental purposes, however,

it is important to frame the information as diagnostic

rather than evaluative (e.g., Kluger & DeNisi, 1996), to

help reduce reactance and increase acceptance.

Leadership Training

In addition to the aforementioned general guidelines,

there are several design and delivery characteristics specific

to leadership training. In particular, research suggests that

leadership training developers should pay close attention to

the desired outcome (e.g., organizational results, transfer,

learning) because leadership training programs may be

more effective for some than others. While leadership train-

ing typically shows positive results for affective learning

and affective transfer, they tend to be even stronger for

cognitive learning, cognitive transfer, skill-based learn-

ing, and skill-based transfer (Avolio, Reichard, Hannah,

Walumbwa, & Chan, 2009; Lacerenza et al., 2017). As

such, when designing a leadership training program, it

might be more beneficial to include (and evaluate) cog-

nitive and/or skill-based content. Relatedly, stakeholder

expectations should be managed to reflect these potential

differences (e.g., make them aware that effects might not

be as large for affective outcomes compared with skill-

based).

The desired outcome(s) should also be identified early on

during training development because the training design

should align with the coveted outcome. Specifically, content

included in the program (e.g., the skills trained) should

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

522 LACERENZA, MARLOW, TANNENBAUM, AND SALAS

consist of that which is proven to influence the desired

outcome. For instance, if team level outcomes are desired

(e.g., cohesion, team satisfaction), the training should in-

corporate skills which support these outcomes. For instance,

research suggests that transformational leaders engender

team cohesion, potency, and performance; as such, if an

organization wishes to increase these outcomes, we suggest

to implement a program incorporating transformational

leadership skills, such as charisma, risk-taking, and mentor-

ing (Judge & Piccolo, 2004). Furthermore, because research

suggests a strong impact of certain leadership styles (i.e.,

transformational leadership, empowering leadership; Lim &

Ployhart, 2004) on team-based outcomes, we recommend

the adoption of programs incorporating related skills if team

outcomes are desired. Research has also shown that team

leadership training programs that build skills related to

initiating structure (a well-known facet of leadership; Judge,

Piccolo, & Ilies, 2004) produce team level effects following

training.

Team Training

As with leadership training, there are additional recom-

mendations specific to team training. As the goal of team

training is to foster improved teamwork, the training should

be tailored such that it is at the team level. In other words,

training goals should be set at the team level and outcomes

should be evaluated at the team level (Salas et al., 2015).

Similarly, researchers note that both team processes (e.g.,

team communication) and outcomes (e.g., performance)

should be measured to evaluate team effectiveness post-

training (Smith-Jentsch, Sierra, & Wiese, 2013). As an

example of an outcome measure, Siassakos and colleagues

(2009) evaluated the effectiveness of a health care team

training program with a measure of patient outcomes (e.g.,

rate of admission to neonatal intensive care unit). As an

example of a process measure, Sonesh et al. (2015) imple-

mented a self-report measure of perceived teamwork fol-

lowing a team training intervention. Data on team outcomes

indicate how well the team is performing while data on team

processes provide insight into why a certain level of per-

formance is being observed. For example, a measure of

team process could reveal that team communication is a

major challenge.

Another recommendation specific to team training is to

foster psychological safety during training. Psychological

safety is a mutual belief among team members that the team

can take interpersonal risks and that a “sense of confidence

that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone

for speaking up” (Edmondson, 1999, p. 354) exists. Psy-

chological safety provides team members the comfort

needed to openly discuss errors without fear of punishment

(Edmondson, 1999). This is especially critical during team

training, as learning from errors has been shown to facilitate

enhanced performance in lab-based settings (Bell & Koz-

lowski, 2008). If psychological safety is established, team

members will be more likely to openly discuss errors and

how to address them in the future (Edmondson, 1999). If

psychological safety is not in place, such a discussion may

not occur.

Improving Team Dynamics: Team Building

Team building has been defined as an intervention de-

signed to foster improvement within a team, providing

individuals closely involved with the task with the strategies

and information needed to solve their own problems (Tan-

nenbaum, Beard, & Salas, 1992). Researchers suggest there

are four primary components to team building which can be

implemented alone or in some combination: (a) goal setting,

(b) interpersonal-relationship management, (c) role clarifi-

cation, and (d) problem solving (Beer, 1976; Dyer, 1977).

Locke, Shaw, Saari, and Latham (1981) suggested that

setting difficult yet specific goals can improve performance.

As an example of a difficult yet specific goal, a team might

set the goal of meeting twice a week. Support for setting

difficult yet specific goals has received ample empirical

support (e.g., Mento, Steel, & Karren, 1987). In a team

building context, the goal-setting component often includes

the establishment of goals at both the individual and team-

level. The interpersonal-relationship management compo-

nent to team building focuses on developing trust and re-

solving conflict, whereas the role clarification component

entails uncovering role ambiguities and conflicts and then

establishing clear roles within the team (Beer, 1976). Fi-

nally, Buller and Bell (1986) describe the problem solving

component as helping team members identify and solve

task-related problems as well as identifying effective decision-

making processes.

A meta-analysis conducted by Klein and colleagues

(2009), based on 60 effect sizes, supports the utility of

team building for several outcomes. Their results indicate

significant positive increases in several cognitive, affec-

tive (e.g., trust), and process (e.g., coordination) out-

comes as a function of team building interventions. How-

ever, they did not find a significant direct effect of

team-building on team performance although perfor-

mance may be enhanced via improvements in the cogni-

tive, affective, and process outcomes discussed. Their

results further indicate that all four components generally

associated with team building interventions significantly

improved some outcomes but goal setting and role clar-

ification were the most effective. Goal setting and role

clarification components build shared understandings of

the task and team (i.e., shared mental models) that, in

turn, may foster changes in team processes.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

523TEAM DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTIONS

outcome. For instance, if team level outcomes are desired

(e.g., cohesion, team satisfaction), the training should in-

corporate skills which support these outcomes. For instance,

research suggests that transformational leaders engender

team cohesion, potency, and performance; as such, if an

organization wishes to increase these outcomes, we suggest

to implement a program incorporating transformational

leadership skills, such as charisma, risk-taking, and mentor-

ing (Judge & Piccolo, 2004). Furthermore, because research

suggests a strong impact of certain leadership styles (i.e.,

transformational leadership, empowering leadership; Lim &

Ployhart, 2004) on team-based outcomes, we recommend

the adoption of programs incorporating related skills if team

outcomes are desired. Research has also shown that team

leadership training programs that build skills related to

initiating structure (a well-known facet of leadership; Judge,

Piccolo, & Ilies, 2004) produce team level effects following

training.

Team Training

As with leadership training, there are additional recom-

mendations specific to team training. As the goal of team

training is to foster improved teamwork, the training should

be tailored such that it is at the team level. In other words,

training goals should be set at the team level and outcomes

should be evaluated at the team level (Salas et al., 2015).

Similarly, researchers note that both team processes (e.g.,

team communication) and outcomes (e.g., performance)

should be measured to evaluate team effectiveness post-

training (Smith-Jentsch, Sierra, & Wiese, 2013). As an

example of an outcome measure, Siassakos and colleagues

(2009) evaluated the effectiveness of a health care team

training program with a measure of patient outcomes (e.g.,

rate of admission to neonatal intensive care unit). As an

example of a process measure, Sonesh et al. (2015) imple-

mented a self-report measure of perceived teamwork fol-

lowing a team training intervention. Data on team outcomes

indicate how well the team is performing while data on team

processes provide insight into why a certain level of per-

formance is being observed. For example, a measure of

team process could reveal that team communication is a

major challenge.

Another recommendation specific to team training is to

foster psychological safety during training. Psychological

safety is a mutual belief among team members that the team

can take interpersonal risks and that a “sense of confidence

that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone

for speaking up” (Edmondson, 1999, p. 354) exists. Psy-

chological safety provides team members the comfort

needed to openly discuss errors without fear of punishment

(Edmondson, 1999). This is especially critical during team

training, as learning from errors has been shown to facilitate

enhanced performance in lab-based settings (Bell & Koz-

lowski, 2008). If psychological safety is established, team

members will be more likely to openly discuss errors and

how to address them in the future (Edmondson, 1999). If

psychological safety is not in place, such a discussion may

not occur.

Improving Team Dynamics: Team Building

Team building has been defined as an intervention de-

signed to foster improvement within a team, providing

individuals closely involved with the task with the strategies

and information needed to solve their own problems (Tan-

nenbaum, Beard, & Salas, 1992). Researchers suggest there

are four primary components to team building which can be

implemented alone or in some combination: (a) goal setting,

(b) interpersonal-relationship management, (c) role clarifi-

cation, and (d) problem solving (Beer, 1976; Dyer, 1977).

Locke, Shaw, Saari, and Latham (1981) suggested that

setting difficult yet specific goals can improve performance.

As an example of a difficult yet specific goal, a team might

set the goal of meeting twice a week. Support for setting

difficult yet specific goals has received ample empirical

support (e.g., Mento, Steel, & Karren, 1987). In a team

building context, the goal-setting component often includes

the establishment of goals at both the individual and team-

level. The interpersonal-relationship management compo-

nent to team building focuses on developing trust and re-

solving conflict, whereas the role clarification component

entails uncovering role ambiguities and conflicts and then

establishing clear roles within the team (Beer, 1976). Fi-

nally, Buller and Bell (1986) describe the problem solving

component as helping team members identify and solve

task-related problems as well as identifying effective decision-

making processes.

A meta-analysis conducted by Klein and colleagues

(2009), based on 60 effect sizes, supports the utility of

team building for several outcomes. Their results indicate

significant positive increases in several cognitive, affec-

tive (e.g., trust), and process (e.g., coordination) out-

comes as a function of team building interventions. How-

ever, they did not find a significant direct effect of

team-building on team performance although perfor-

mance may be enhanced via improvements in the cogni-

tive, affective, and process outcomes discussed. Their

results further indicate that all four components generally

associated with team building interventions significantly

improved some outcomes but goal setting and role clar-

ification were the most effective. Goal setting and role

clarification components build shared understandings of

the task and team (i.e., shared mental models) that, in

turn, may foster changes in team processes.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

523TEAM DEVELOPMENT INTERVENTIONS

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Team Building: What Works, According

to Science

Each of the components of team building are founded on

theories that have been experimentally supported. Organi-

zations should clarify the needs of the teams to determine

the most appropriate team building components. Locke and

Latham (2002) suggest that goal setting improves perfor-

mance through four specific mechanisms, by: (1) directing

attention and effort toward identified goals, (2) energizing,

(3) affecting persistence, and (4) affecting action through

the discovery and/or use of knowledge pertinent to the task.

Goals set at the team level are intended to be relevant to all

team members and to focus on team outcomes (Mills,

1984). Interpersonal-relationship management is a compo-

nent that fosters trust and provides team members with ways

to manage team conflict effectively (Argyris, 1962). This

typically involves a facilitator fostering open conversations

among team members to address any issues, resolve any

existing conflicts, and subsequently improve trust among

team members through these discussions (Salas et al., 2005).

Providing individuals the opportunity to self-discover concerns

through these discussions or other means can lead to awareness

of specific teamwork weaknesses.

Trust enables team members to overcome uncertainty and

accept vulnerability toward teammates, enabling better team

coordination and performance; this is a robust finding meta-

analytically demonstrated across both field and lab samples

(De Jong, Dirks, & Gillespie, 2016). Virtually all teams

experience conflict at times, so conflict management is also

important for effective team functioning. Top performing

MBA teams were found to engage in effective conflict

resolution techniques, including: (a) targeting content, rather

than interpersonal interactions, (b) discussing the rationale for

work assignments, and (c) assigning work based on expertise

(Behfar, Peterson, Mannix, & Trochim, 2008). Team building

can help a team develop constructive conflict management

techniques and avoid behaviors such as blaming and with-

holding information (Edelmann, 1993). Behfar et al. (2008)

note that such behaviors can result in a decreased willing-

ness to contribute to the team in a proactive manner (Jehn,

1997). Role clarification serves a similarly important func-

tion in increasing team effectiveness. Research in field

settings indicates that through establishing clearer delinea-

tion of roles and responsibilities, team members attain a

better understanding of their own and the teammates’ re-

sponsibilities (Salas, Rozell, Mullen, & Driskell, 1999). A

similar finding with real-world teams indicates that role clarity

can decrease confusion during task performance, facilitate

backup behavior, and yield more effective outcomes (Eys &

Carron, 2001).

Role clarity does not assume role rigidity. Rather, it

implies a common understanding among team members

about the way roles should be performed. There can be role

clarity in teams that require team flexibility. For example, if

team members have a common understanding about how

different people should fill different roles based on specific

work demands, they have role clarity without role rigidity.

Role clarity is important in almost any team, but may be

particularly so in teams that need to be adaptive. During a

team building intervention, team members may discuss and

determine the situations and task characteristics that require

individuals to assume other team members’ roles. Research

in field settings has shown that this type of role flexibility

can lead to enhanced team performance (Campion, Med-

sker, & Higgs, 1993) although the necessity of role flexi-

bility is contingent upon team type and associated demands.

Finally, problem solving helps team members identify task-

related problems, and implement solutions accordingly.

Dyer (1977) suggests that this component enhances team

effectiveness because it provides a structure for teams to

work together, pooling individual resources, to address key

team problems. Shuffler et al. (2011) further argues this can

develop enhanced decision-making skills, which has also

been linked to more effective team performance (Kerr &

Tindale, 2004).

Taken as a whole, each of the components of team

building serves an integral purpose in furthering team

effectiveness, and when using any of these approaches, it

is critical that teams delineate tangible action plans or

agreements to ensure there is no confusion about what

needs to be done. It is also important to follow up on

these plans to maintain accountability (Tannenbaum et

al., 1992). The aforementioned information reflects

evidence-based components of team building programs.

Oftentimes, organizations respond to teamwork issues by

scheduling team activities that are seemingly light-

hearted, fun, and increase time spent between team mem-

bers (e.g., a ropes course, icebreaker). Although these

exercises may work in the short-term, there is limited

evidence suggesting that team building activities lacking

scientifically based components are effective (Shuffler,

Burke, Kramer, & Salas, 2013). As such, it is recom-

mended to incorporate only scientifically derived team

building interventions to ensure benefits are achieved.

Scenario 3: Team Building in an Insurance

Claims Team

Insurance claims teams need to coordinate and commu-

nicate effectively to respond to customer needs, making

prompt, smart decisions that benefit both the customer and

the company. In one organization, a number of disruptive

changes were introduced, including a change in technology

and an organizational restructuring that resulted in a change

of leaders and responsibilities. As a result, one of the teams

was struggling. After talking with several team members,

the team leader recognizes that there is a great deal of

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

524 LACERENZA, MARLOW, TANNENBAUM, AND SALAS

to Science

Each of the components of team building are founded on

theories that have been experimentally supported. Organi-

zations should clarify the needs of the teams to determine

the most appropriate team building components. Locke and

Latham (2002) suggest that goal setting improves perfor-

mance through four specific mechanisms, by: (1) directing

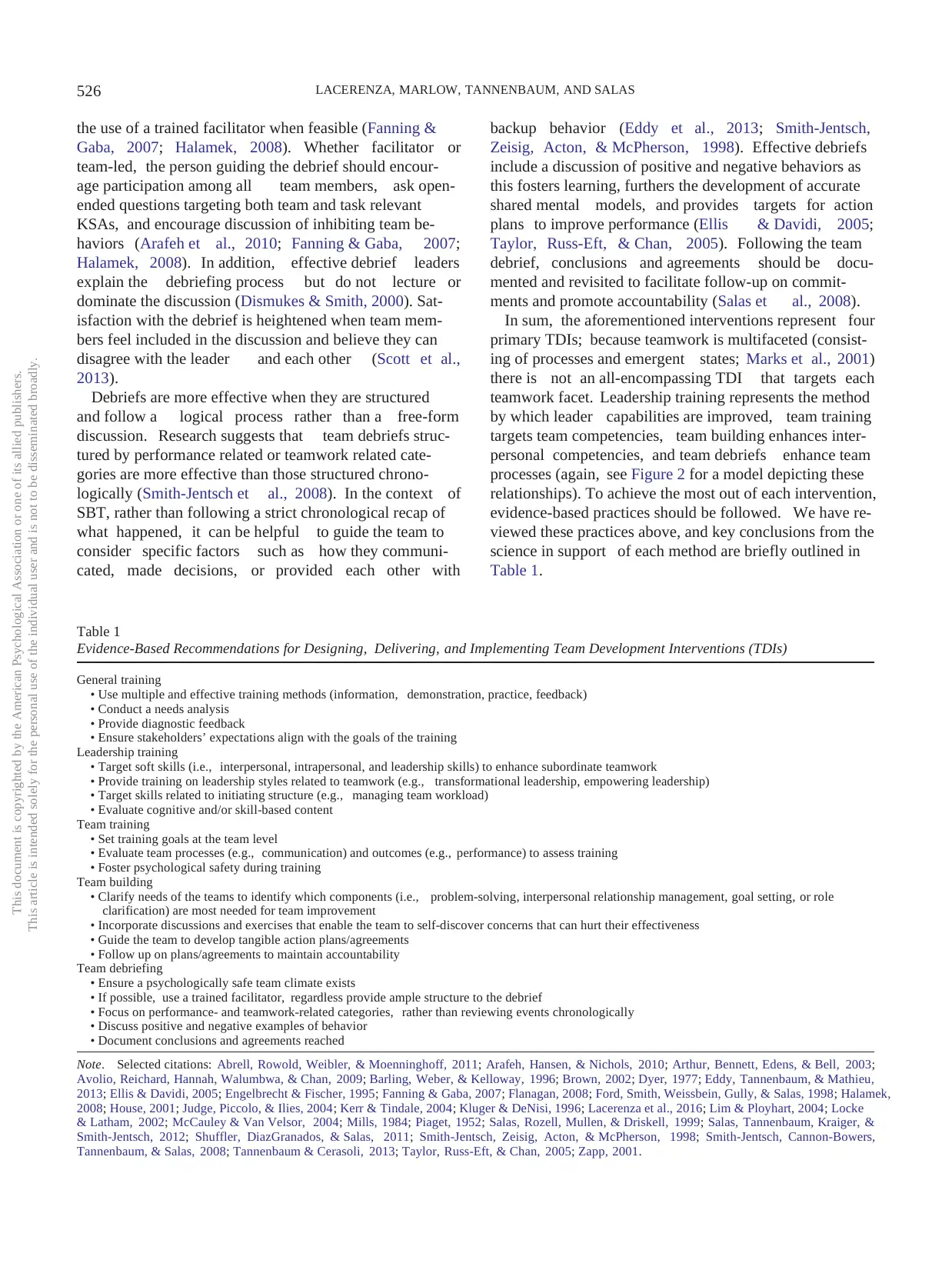

attention and effort toward identified goals, (2) energizing,