Applying Mixed Methods to QSR Customer Satisfaction at the Unit Level

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/18

|10

|11383

|323

Report

AI Summary

This report explores the drivers of customer satisfaction in Quick Service Restaurants (QSRs) at the unit level, addressing the limitations of the Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) method. The study synthesizes qualitative methods, Penalty-Reward Contrast Analysis (PRCA), and importance grid methods to identify key attributes influencing customer satisfaction. Findings reveal basic factors like taste, temperature, and accuracy, performance factors such as friendliness, and excitement factors including cleanliness, speed, and ease of understanding. The study emphasizes prioritizing taste, temperature, and accuracy, followed by friendliness, and then allocating resources to cleanliness, speed, and ease of understanding. The research contributes a novel approach to optimize resource allocation and provides practical insights for hospitality practitioners aiming to enhance customer satisfaction in the competitive QSR environment. The generalizability is limited to the single QSR chain examined and the limited number of attributes considered.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282562967

Applying mixed methods to identify what drives quick service restaurant's

customer satisfaction at the unit-level

Article in International Journal of Hospitality Management · September 2015

DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.07.007

CITATIONS

16

READS

749

3 authors, including:

Kimberly Mathe

Oklahoma State University - Stillwater

19PUBLICATIONS210CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Lisa Slevitch

Oklahoma State University - Stillwater

24PUBLICATIONS245CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Applying mixed methods to identify what drives quick service restaurant's

customer satisfaction at the unit-level

Article in International Journal of Hospitality Management · September 2015

DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.07.007

CITATIONS

16

READS

749

3 authors, including:

Kimberly Mathe

Oklahoma State University - Stillwater

19PUBLICATIONS210CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Lisa Slevitch

Oklahoma State University - Stillwater

24PUBLICATIONS245CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

International Journal of Hospitality Management 50 (2015) 46–54

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Hospitality Management

j o u r n a lh o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / i j h o s m a n

Applying mixed methods to identify what drives quick service

restaurant’s customer satisfaction at the unit-level

Kimberly Mathe-Souleka, Lisa Slevitchb,∗, Ioana Dallingerc

a Texas Tech University, College of Human Sciences, Department of Retailing, Hospitality and Institutional Management, United States

b School of Hotel and Restaurant Administration, Oklahoma State University, 210 HESW, Stillwater, OK 74078-6173, United States

c Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Virginia Tech University, 352 Wallace Hall, Virginia Tech, 295 West Campus Drive, Blacksburg,

VA 24061, United States

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 21 August 2014

Received in revised form 14 July 2015

Accepted 16 July 2015

Keywords:

Customer satisfaction

Kano’s model

Quick service restaurants

Performance optimization

Service quality

Product quality

a b s t r a c t

The current study addresses issues related to developing a set of criticalquality attributes. The pri-

mary research objective was to address drawbacks of importance–performance method and develop

a novel approach that identifies satisfaction drivers for unit-level quick service restaurant (QSR).The

new approach is based on synthesis of qualitative,PRCA, and importance grid methods.Basic (taste,

temperature, and accuracy), performance (friendliness) and excitement (cleanliness, speed, and ease of

understanding) factors were identified for a QSR context. The current findings help to resolve the problem

of performance optimization and identify an optimal set of QSR attributes to allocate resources.Taste,

temperature, and accuracy must be ensured as top priority. Then, friendliness should also be ensured and

only after that the resources should be allocated to cleanliness, speed, and ease of understanding. Gen-

eralizability of the findings is bounded by the fact that only one QSR chain was examined. Additionally,

only a limited number of QSR attributes was examined.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The foodservice industry is highly competitive, with 29% of all

restaurant sales coming from the quick service restaurant (QSR)

segment (QSR Magazine, 2012a). In such an environment, cus-

tomer satisfaction is considered to be a critical indicator for the

businesses’future; as high levels of customer satisfaction tend

to lead to loyalty, which in return leads to profits (Chen, 2012;

Matzler and Hinterhuber, 1998). Additionally, customer satisfac-

tion reduces price sensitivity, increases cross-buying, and increases

positive word-of-mouth (Matzler et al., 2004).

The widely accepted satisfaction-profit chain framework sug-

gests that profits stem from customer retention that arises from

high levels of customer satisfaction, which is achieved by delivering

quality product or service (Anderson and Mittal, 2000). The con-

ceptual logic underlying the satisfaction-profit chain stems from

the idea that by improving product or service attributes or quality,

customer satisfaction should increase. When customer satisfaction

increases based on attributes of the restaurant experience, this in

∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 405 744 7643; fax: +1 405 744 6299.

E-mail addresses: kim.mathe@okstate.edu (K. Mathe-Soulek),

lisa.slevitch@okstate.edu (L. Slevitch), kioana@vt.edu (I. Dallinger).

turn will lead to greater profitability, revisit intentions, customer

traffic, and sales (Gupta et al., 2007).

It should be noted that there has been little agreement on the

primary drivers of restaurant satisfaction,in large part because

each segment of the restaurant industry can have different expec-

tations of the product and service. What is commonly agreed

on, is that knowing and delivering the optimal set of product or

service attributes that produce the highest level of customer sat-

isfaction is crucial to the competitive edge of businesses (Mikuli´c

and Prebeˇzac, 2011). With this idea in mind, numerous attempts

have been made to identify critical service or product attributes

that generate customer satisfaction in order to stay abreast of

competitors (Deng et al., 2008). Customer satisfaction determi-

nants at an attribute level are generally operationalized through

the Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA). In this prominent

approach, a list of attributes is generated first, and then, customers

are asked to rate a product or service on the degree of how each

of the attributes is delivered. Also, consumers are asked to rate the

importance of each attribute. Finally, an overall score is computed

as a sum of individual attribute scores weighed by the level of their

importance (Martilla and James, 1977).

In spite of its dominance,the IPA method has numerous flaws

and can be misleading in attempts to identify an optimal set of prod-

uct or service features (Deng, 2007; Matzler et al., 2003; Oh, 2001).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.07.007

0278-4319/© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Hospitality Management

j o u r n a lh o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / i j h o s m a n

Applying mixed methods to identify what drives quick service

restaurant’s customer satisfaction at the unit-level

Kimberly Mathe-Souleka, Lisa Slevitchb,∗, Ioana Dallingerc

a Texas Tech University, College of Human Sciences, Department of Retailing, Hospitality and Institutional Management, United States

b School of Hotel and Restaurant Administration, Oklahoma State University, 210 HESW, Stillwater, OK 74078-6173, United States

c Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Virginia Tech University, 352 Wallace Hall, Virginia Tech, 295 West Campus Drive, Blacksburg,

VA 24061, United States

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 21 August 2014

Received in revised form 14 July 2015

Accepted 16 July 2015

Keywords:

Customer satisfaction

Kano’s model

Quick service restaurants

Performance optimization

Service quality

Product quality

a b s t r a c t

The current study addresses issues related to developing a set of criticalquality attributes. The pri-

mary research objective was to address drawbacks of importance–performance method and develop

a novel approach that identifies satisfaction drivers for unit-level quick service restaurant (QSR).The

new approach is based on synthesis of qualitative,PRCA, and importance grid methods.Basic (taste,

temperature, and accuracy), performance (friendliness) and excitement (cleanliness, speed, and ease of

understanding) factors were identified for a QSR context. The current findings help to resolve the problem

of performance optimization and identify an optimal set of QSR attributes to allocate resources.Taste,

temperature, and accuracy must be ensured as top priority. Then, friendliness should also be ensured and

only after that the resources should be allocated to cleanliness, speed, and ease of understanding. Gen-

eralizability of the findings is bounded by the fact that only one QSR chain was examined. Additionally,

only a limited number of QSR attributes was examined.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The foodservice industry is highly competitive, with 29% of all

restaurant sales coming from the quick service restaurant (QSR)

segment (QSR Magazine, 2012a). In such an environment, cus-

tomer satisfaction is considered to be a critical indicator for the

businesses’future; as high levels of customer satisfaction tend

to lead to loyalty, which in return leads to profits (Chen, 2012;

Matzler and Hinterhuber, 1998). Additionally, customer satisfac-

tion reduces price sensitivity, increases cross-buying, and increases

positive word-of-mouth (Matzler et al., 2004).

The widely accepted satisfaction-profit chain framework sug-

gests that profits stem from customer retention that arises from

high levels of customer satisfaction, which is achieved by delivering

quality product or service (Anderson and Mittal, 2000). The con-

ceptual logic underlying the satisfaction-profit chain stems from

the idea that by improving product or service attributes or quality,

customer satisfaction should increase. When customer satisfaction

increases based on attributes of the restaurant experience, this in

∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 405 744 7643; fax: +1 405 744 6299.

E-mail addresses: kim.mathe@okstate.edu (K. Mathe-Soulek),

lisa.slevitch@okstate.edu (L. Slevitch), kioana@vt.edu (I. Dallinger).

turn will lead to greater profitability, revisit intentions, customer

traffic, and sales (Gupta et al., 2007).

It should be noted that there has been little agreement on the

primary drivers of restaurant satisfaction,in large part because

each segment of the restaurant industry can have different expec-

tations of the product and service. What is commonly agreed

on, is that knowing and delivering the optimal set of product or

service attributes that produce the highest level of customer sat-

isfaction is crucial to the competitive edge of businesses (Mikuli´c

and Prebeˇzac, 2011). With this idea in mind, numerous attempts

have been made to identify critical service or product attributes

that generate customer satisfaction in order to stay abreast of

competitors (Deng et al., 2008). Customer satisfaction determi-

nants at an attribute level are generally operationalized through

the Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA). In this prominent

approach, a list of attributes is generated first, and then, customers

are asked to rate a product or service on the degree of how each

of the attributes is delivered. Also, consumers are asked to rate the

importance of each attribute. Finally, an overall score is computed

as a sum of individual attribute scores weighed by the level of their

importance (Martilla and James, 1977).

In spite of its dominance,the IPA method has numerous flaws

and can be misleading in attempts to identify an optimal set of prod-

uct or service features (Deng, 2007; Matzler et al., 2003; Oh, 2001).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.07.007

0278-4319/© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

K. Mathe-Soulek et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 50 (2015) 46–54 47

IPA does not provide clear definition for the concept of importance

and does not take into account whether the attribute is important

for its presence or its absence (Deng et al., 2008). Additionally, IPA’s

underlying assumption is that importance and performance are

two independent entities, however, numerous studies have con-

firmed that the relationship between attribute performance and

attribute importance was causal and attribute importance changed

as attribute performance did (Matzler et al., 2003; Oh, 2001; Oliver,

1997). Another one of the major IPA’s assumptions is that the cus-

tomer satisfaction function is linear and additive in nature, though

it was proven otherwise (Bartikowski and Llosa, 2003; Hui et al.,

2005; Matzler et al., 2004; Slevitch and Oh, 2010). Therefore, the IPA

approach is innately geared toward performance maximization, not

optimization, consequently, leaving the problem of optimal deploy-

ment of resources unaddressed (Chen,2012; Mittal et al., 1998).

More importantly, both academics and practitioners report that

equally investing in greater performance along all service attributes

in order to increase satisfaction would not be effective and does not

justify additional investments (Busacca and Padula, 2005; Cadotte

and Turgeon, 1988; Lin et al., 2010; Mittal et al., 1998).

As Oh (2001) states, hospitality academics and practitioners

continue to use IPA without giving critical considerations to its

conceptual and practical validities. Oh (2001) further suggests that

though easy applicability is always desirable, simplicity and conve-

nience should not be the predominant criteria when choosing and

applying a research method.Oh (2001) concludes that thorough

reassessment of IPA as a tool is necessary.

Therefore, the current study attempts to address the issues

raised by previous researchers with regard to IPA (Deng, 2007; Oh,

2001) and tackle the problem of a better method to identify sat-

isfaction determinants.Several alternatives,such as Kano et al.’s

model, PRCA, and qualitative approach, address many of the IPA’s

drawbacks (Chen, 2012). The main objective of this study is to syn-

thesize several existing methods that overcome shortcomings of

IPA as summarized by Oh (2001) and Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac (2011),

and to test them in the context of QSR – an area where intense

competition makes knowing satisfaction determinants a matter

of survival. More specifically, through mixed methods,this study

will examine unit-level QSR attributes rated by independent sets

of consumers. The significance of the current study is grounded

in utilizing a mixed methods design, which addresses some of the

limitations of the IPA method by providing a novel and useful tool

to assess attributes and their relationships to customer satisfaction.

The latter would have a significant practical significance, as the new

method would allow hospitality practitioners to truly define what

drives customer satisfaction and optimize their resource allocation.

A visual depiction of this research framework of mixed methods can

be seen in Fig. 1.

2. Literature review

Multiple attempts have been made to develop a better method of

identifying a critical set of quality attributes (Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac,

2011). Some studies have modified IPA with the basic frame-

work remaining largely the same, however several researchers

presented a framework that rectifies the flaws of the original

IPA model (Matzler et al., 2003). Methods that address issues of

performance–importance dependence and the asymmetric nature

of the customer satisfaction function stem from Kano’s Theory of

Attractive Quality,which is often referred as Kano’s model (Kano

et al., 1984). In turn, Kano’s theory is grounded into Herzberg’s work

on job satisfaction where Herzberg introduced two categories of

factors, hygiene and motivators, based on their dissimilar effect on

satisfaction (Herzberg, 1967).

The original Kano’s model distinguishes between five dif-

ferent quality attribute types: attractive,one-dimensional,basic

Fig. 1. Present study’s research framework adapted from Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac

(2011).

(must-be),indifference,and reverse.Each category influences cus-

tomer satisfaction differently. Inadequate performance on must-be

attributes leads to dissatisfaction while adequate performances

on these attributes has minimal or no effect on satisfaction.One-

dimensional attributes have equal impact on customer satisfaction

in cases of over- and under-fulfillment. Attractive attributes pro-

duce satisfaction in a fulfilled state, but result in minimal or no

impact when performance is low.

To categorize quality attributes, Kano et al. (1984) developed a

special questionnaire based on the critical incident technique (CIT).

The questionnaire contains pairs of questions for each attribute

of a given product or service. Each pair contains a question about

respondents’ feelings in the case of performance fulfillment (func-

tional question – how would you feel if food tastes good?) and

another question for a situation of under-fulfillment (dysfunctional

question – how would you feel if food does not taste good?). Then,

a special evaluation table is used to categorize attributes based on

response frequencies.

Though the Kano questionnaire remains the most appropriate

approach to identify original Kano categories,it is also found too

complex and difficult to implement in real world situations (Chen,

2012; Mikuli ´c and Prebeˇzac, 2011). As Chen (2012) states, it takes

much longer to respond to the Kano’s questionnaire than typical IPA

questionnaires,because two similar questions are asked for each

attribute and that tends to decrease the willingness of respondents

to complete the questionnaire. Additionally, respondents are easily

confused when required to envision opposite conditions (func-

tional and dysfunctional).

In attempts to overcome this problem, several researchers found

that regression methods provided a better fit for attribute catego-

rization (Busacca and Padula,2005; Lin et al., 2010; Löfgren and

Witell, 2008; Matzler et al., 2003; Ting and Chen, 2002; Vavra,

1997). The biggest operational advantage of these regression meth-

ods is that they apply data from attribute-level performance and

customer satisfaction measurement, which are far easier to collect

than answers to functional and dysfunctional questions suggested

by Kano et al. (1984). The present study utilizes three of the meth-

ods that fall under the critical incident technique method including

qualitative methods, penalty–reward contrast analysis (PRCA) and

the importance grid method.

IPA does not provide clear definition for the concept of importance

and does not take into account whether the attribute is important

for its presence or its absence (Deng et al., 2008). Additionally, IPA’s

underlying assumption is that importance and performance are

two independent entities, however, numerous studies have con-

firmed that the relationship between attribute performance and

attribute importance was causal and attribute importance changed

as attribute performance did (Matzler et al., 2003; Oh, 2001; Oliver,

1997). Another one of the major IPA’s assumptions is that the cus-

tomer satisfaction function is linear and additive in nature, though

it was proven otherwise (Bartikowski and Llosa, 2003; Hui et al.,

2005; Matzler et al., 2004; Slevitch and Oh, 2010). Therefore, the IPA

approach is innately geared toward performance maximization, not

optimization, consequently, leaving the problem of optimal deploy-

ment of resources unaddressed (Chen,2012; Mittal et al., 1998).

More importantly, both academics and practitioners report that

equally investing in greater performance along all service attributes

in order to increase satisfaction would not be effective and does not

justify additional investments (Busacca and Padula, 2005; Cadotte

and Turgeon, 1988; Lin et al., 2010; Mittal et al., 1998).

As Oh (2001) states, hospitality academics and practitioners

continue to use IPA without giving critical considerations to its

conceptual and practical validities. Oh (2001) further suggests that

though easy applicability is always desirable, simplicity and conve-

nience should not be the predominant criteria when choosing and

applying a research method.Oh (2001) concludes that thorough

reassessment of IPA as a tool is necessary.

Therefore, the current study attempts to address the issues

raised by previous researchers with regard to IPA (Deng, 2007; Oh,

2001) and tackle the problem of a better method to identify sat-

isfaction determinants.Several alternatives,such as Kano et al.’s

model, PRCA, and qualitative approach, address many of the IPA’s

drawbacks (Chen, 2012). The main objective of this study is to syn-

thesize several existing methods that overcome shortcomings of

IPA as summarized by Oh (2001) and Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac (2011),

and to test them in the context of QSR – an area where intense

competition makes knowing satisfaction determinants a matter

of survival. More specifically, through mixed methods,this study

will examine unit-level QSR attributes rated by independent sets

of consumers. The significance of the current study is grounded

in utilizing a mixed methods design, which addresses some of the

limitations of the IPA method by providing a novel and useful tool

to assess attributes and their relationships to customer satisfaction.

The latter would have a significant practical significance, as the new

method would allow hospitality practitioners to truly define what

drives customer satisfaction and optimize their resource allocation.

A visual depiction of this research framework of mixed methods can

be seen in Fig. 1.

2. Literature review

Multiple attempts have been made to develop a better method of

identifying a critical set of quality attributes (Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac,

2011). Some studies have modified IPA with the basic frame-

work remaining largely the same, however several researchers

presented a framework that rectifies the flaws of the original

IPA model (Matzler et al., 2003). Methods that address issues of

performance–importance dependence and the asymmetric nature

of the customer satisfaction function stem from Kano’s Theory of

Attractive Quality,which is often referred as Kano’s model (Kano

et al., 1984). In turn, Kano’s theory is grounded into Herzberg’s work

on job satisfaction where Herzberg introduced two categories of

factors, hygiene and motivators, based on their dissimilar effect on

satisfaction (Herzberg, 1967).

The original Kano’s model distinguishes between five dif-

ferent quality attribute types: attractive,one-dimensional,basic

Fig. 1. Present study’s research framework adapted from Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac

(2011).

(must-be),indifference,and reverse.Each category influences cus-

tomer satisfaction differently. Inadequate performance on must-be

attributes leads to dissatisfaction while adequate performances

on these attributes has minimal or no effect on satisfaction.One-

dimensional attributes have equal impact on customer satisfaction

in cases of over- and under-fulfillment. Attractive attributes pro-

duce satisfaction in a fulfilled state, but result in minimal or no

impact when performance is low.

To categorize quality attributes, Kano et al. (1984) developed a

special questionnaire based on the critical incident technique (CIT).

The questionnaire contains pairs of questions for each attribute

of a given product or service. Each pair contains a question about

respondents’ feelings in the case of performance fulfillment (func-

tional question – how would you feel if food tastes good?) and

another question for a situation of under-fulfillment (dysfunctional

question – how would you feel if food does not taste good?). Then,

a special evaluation table is used to categorize attributes based on

response frequencies.

Though the Kano questionnaire remains the most appropriate

approach to identify original Kano categories,it is also found too

complex and difficult to implement in real world situations (Chen,

2012; Mikuli ´c and Prebeˇzac, 2011). As Chen (2012) states, it takes

much longer to respond to the Kano’s questionnaire than typical IPA

questionnaires,because two similar questions are asked for each

attribute and that tends to decrease the willingness of respondents

to complete the questionnaire. Additionally, respondents are easily

confused when required to envision opposite conditions (func-

tional and dysfunctional).

In attempts to overcome this problem, several researchers found

that regression methods provided a better fit for attribute catego-

rization (Busacca and Padula,2005; Lin et al., 2010; Löfgren and

Witell, 2008; Matzler et al., 2003; Ting and Chen, 2002; Vavra,

1997). The biggest operational advantage of these regression meth-

ods is that they apply data from attribute-level performance and

customer satisfaction measurement, which are far easier to collect

than answers to functional and dysfunctional questions suggested

by Kano et al. (1984). The present study utilizes three of the meth-

ods that fall under the critical incident technique method including

qualitative methods, penalty–reward contrast analysis (PRCA) and

the importance grid method.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

48 K. Mathe-Soulek et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 50 (2015) 46–54

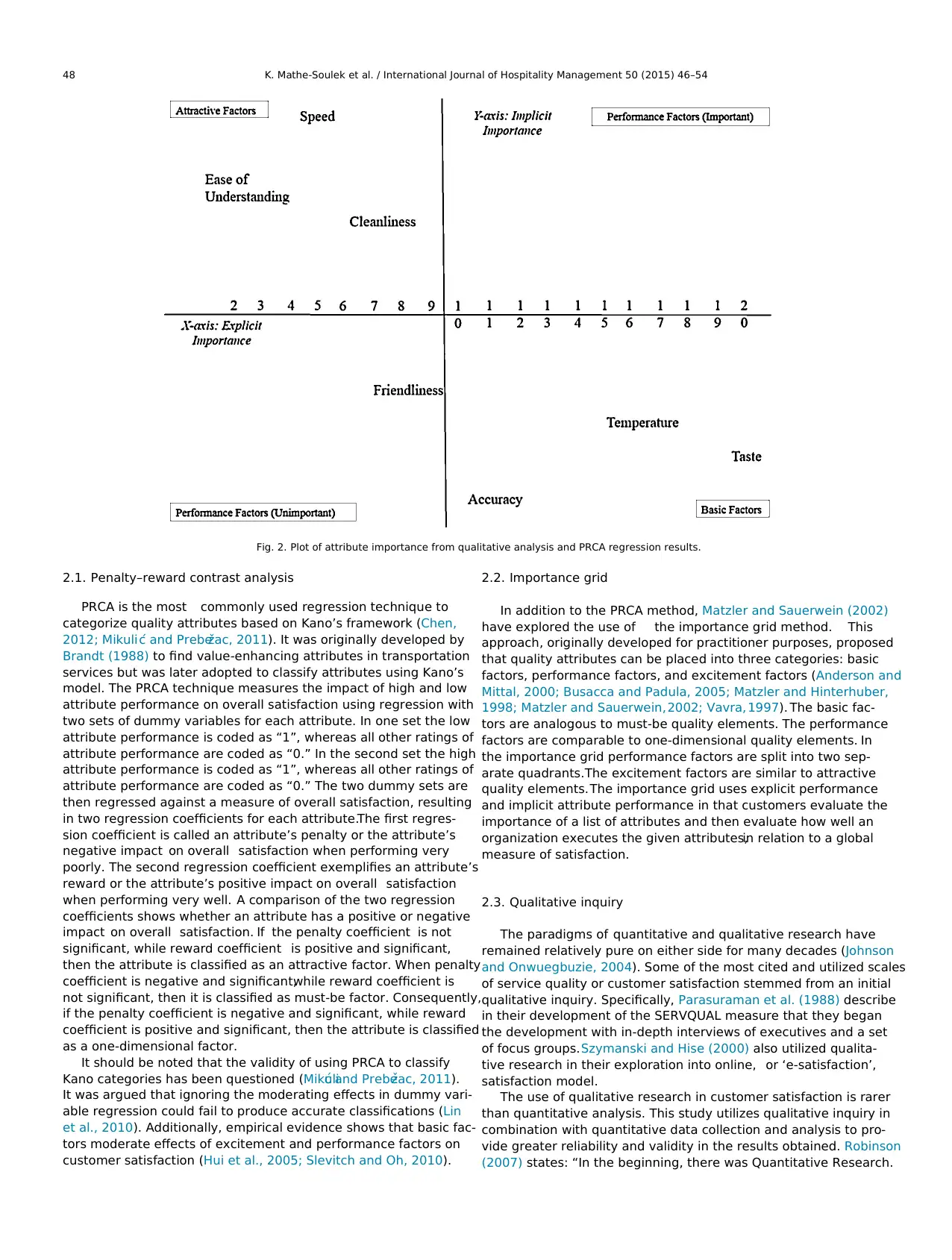

Fig. 2. Plot of attribute importance from qualitative analysis and PRCA regression results.

2.1. Penalty–reward contrast analysis

PRCA is the most commonly used regression technique to

categorize quality attributes based on Kano’s framework (Chen,

2012; Mikuli ´c and Prebeˇzac, 2011). It was originally developed by

Brandt (1988) to find value-enhancing attributes in transportation

services but was later adopted to classify attributes using Kano’s

model. The PRCA technique measures the impact of high and low

attribute performance on overall satisfaction using regression with

two sets of dummy variables for each attribute. In one set the low

attribute performance is coded as “1”, whereas all other ratings of

attribute performance are coded as “0.” In the second set the high

attribute performance is coded as “1”, whereas all other ratings of

attribute performance are coded as “0.” The two dummy sets are

then regressed against a measure of overall satisfaction, resulting

in two regression coefficients for each attribute.The first regres-

sion coefficient is called an attribute’s penalty or the attribute’s

negative impact on overall satisfaction when performing very

poorly. The second regression coefficient exemplifies an attribute’s

reward or the attribute’s positive impact on overall satisfaction

when performing very well. A comparison of the two regression

coefficients shows whether an attribute has a positive or negative

impact on overall satisfaction. If the penalty coefficient is not

significant, while reward coefficient is positive and significant,

then the attribute is classified as an attractive factor. When penalty

coefficient is negative and significant,while reward coefficient is

not significant, then it is classified as must-be factor. Consequently,

if the penalty coefficient is negative and significant, while reward

coefficient is positive and significant, then the attribute is classified

as a one-dimensional factor.

It should be noted that the validity of using PRCA to classify

Kano categories has been questioned (Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac, 2011).

It was argued that ignoring the moderating effects in dummy vari-

able regression could fail to produce accurate classifications (Lin

et al., 2010). Additionally, empirical evidence shows that basic fac-

tors moderate effects of excitement and performance factors on

customer satisfaction (Hui et al., 2005; Slevitch and Oh, 2010).

2.2. Importance grid

In addition to the PRCA method, Matzler and Sauerwein (2002)

have explored the use of the importance grid method. This

approach, originally developed for practitioner purposes, proposed

that quality attributes can be placed into three categories: basic

factors, performance factors, and excitement factors (Anderson and

Mittal, 2000; Busacca and Padula, 2005; Matzler and Hinterhuber,

1998; Matzler and Sauerwein,2002; Vavra, 1997). The basic fac-

tors are analogous to must-be quality elements. The performance

factors are comparable to one-dimensional quality elements. In

the importance grid performance factors are split into two sep-

arate quadrants.The excitement factors are similar to attractive

quality elements.The importance grid uses explicit performance

and implicit attribute performance in that customers evaluate the

importance of a list of attributes and then evaluate how well an

organization executes the given attributes,in relation to a global

measure of satisfaction.

2.3. Qualitative inquiry

The paradigms of quantitative and qualitative research have

remained relatively pure on either side for many decades (Johnson

and Onwuegbuzie, 2004). Some of the most cited and utilized scales

of service quality or customer satisfaction stemmed from an initial

qualitative inquiry. Specifically, Parasuraman et al. (1988) describe

in their development of the SERVQUAL measure that they began

the development with in-depth interviews of executives and a set

of focus groups.Szymanski and Hise (2000) also utilized qualita-

tive research in their exploration into online, or ‘e-satisfaction’,

satisfaction model.

The use of qualitative research in customer satisfaction is rarer

than quantitative analysis. This study utilizes qualitative inquiry in

combination with quantitative data collection and analysis to pro-

vide greater reliability and validity in the results obtained. Robinson

(2007) states: “In the beginning, there was Quantitative Research.

Fig. 2. Plot of attribute importance from qualitative analysis and PRCA regression results.

2.1. Penalty–reward contrast analysis

PRCA is the most commonly used regression technique to

categorize quality attributes based on Kano’s framework (Chen,

2012; Mikuli ´c and Prebeˇzac, 2011). It was originally developed by

Brandt (1988) to find value-enhancing attributes in transportation

services but was later adopted to classify attributes using Kano’s

model. The PRCA technique measures the impact of high and low

attribute performance on overall satisfaction using regression with

two sets of dummy variables for each attribute. In one set the low

attribute performance is coded as “1”, whereas all other ratings of

attribute performance are coded as “0.” In the second set the high

attribute performance is coded as “1”, whereas all other ratings of

attribute performance are coded as “0.” The two dummy sets are

then regressed against a measure of overall satisfaction, resulting

in two regression coefficients for each attribute.The first regres-

sion coefficient is called an attribute’s penalty or the attribute’s

negative impact on overall satisfaction when performing very

poorly. The second regression coefficient exemplifies an attribute’s

reward or the attribute’s positive impact on overall satisfaction

when performing very well. A comparison of the two regression

coefficients shows whether an attribute has a positive or negative

impact on overall satisfaction. If the penalty coefficient is not

significant, while reward coefficient is positive and significant,

then the attribute is classified as an attractive factor. When penalty

coefficient is negative and significant,while reward coefficient is

not significant, then it is classified as must-be factor. Consequently,

if the penalty coefficient is negative and significant, while reward

coefficient is positive and significant, then the attribute is classified

as a one-dimensional factor.

It should be noted that the validity of using PRCA to classify

Kano categories has been questioned (Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac, 2011).

It was argued that ignoring the moderating effects in dummy vari-

able regression could fail to produce accurate classifications (Lin

et al., 2010). Additionally, empirical evidence shows that basic fac-

tors moderate effects of excitement and performance factors on

customer satisfaction (Hui et al., 2005; Slevitch and Oh, 2010).

2.2. Importance grid

In addition to the PRCA method, Matzler and Sauerwein (2002)

have explored the use of the importance grid method. This

approach, originally developed for practitioner purposes, proposed

that quality attributes can be placed into three categories: basic

factors, performance factors, and excitement factors (Anderson and

Mittal, 2000; Busacca and Padula, 2005; Matzler and Hinterhuber,

1998; Matzler and Sauerwein,2002; Vavra, 1997). The basic fac-

tors are analogous to must-be quality elements. The performance

factors are comparable to one-dimensional quality elements. In

the importance grid performance factors are split into two sep-

arate quadrants.The excitement factors are similar to attractive

quality elements.The importance grid uses explicit performance

and implicit attribute performance in that customers evaluate the

importance of a list of attributes and then evaluate how well an

organization executes the given attributes,in relation to a global

measure of satisfaction.

2.3. Qualitative inquiry

The paradigms of quantitative and qualitative research have

remained relatively pure on either side for many decades (Johnson

and Onwuegbuzie, 2004). Some of the most cited and utilized scales

of service quality or customer satisfaction stemmed from an initial

qualitative inquiry. Specifically, Parasuraman et al. (1988) describe

in their development of the SERVQUAL measure that they began

the development with in-depth interviews of executives and a set

of focus groups.Szymanski and Hise (2000) also utilized qualita-

tive research in their exploration into online, or ‘e-satisfaction’,

satisfaction model.

The use of qualitative research in customer satisfaction is rarer

than quantitative analysis. This study utilizes qualitative inquiry in

combination with quantitative data collection and analysis to pro-

vide greater reliability and validity in the results obtained. Robinson

(2007) states: “In the beginning, there was Quantitative Research.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

K. Mathe-Soulek et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 50 (2015) 46–54 49

A few years later, there was Qualitative Research. And then, Mixed

Methods was born as a separate child of these parents” (p. 388). As

Creswell and Clark (2007) describe, there are generally four types

of designs in mixed methods: embedded, exploratory, triangulated,

and explanatory. The crux of this study focuses on the triangulated

approach,which utilizes different research approaches,methods,

and techniques in the same study (Hussey and Hussey, 1997;

Mangan et al., 2004).

The present study seeks to not only explore the PRCA method

in relation to QSR performance,but also proposes a new method

of performance planning that combines aspects of a qualitative

approach, the importance grid, and the regression results of the

PRCA, three of the primary methods Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac (2011)

suggest using for IPA classification. Consequently, the satisfaction

with the penalty and reward attributes in relation to the quad-

rants of the importance grid is assumed to better define customer

satisfaction. Since the method combines a qualitative approach

and quantitative approach, the results redefine the axes on which

attributes are plotted.

Applying Kano’s categorization in the QSR industry is impor-

tant because in addition to the fact that the categorization varies

between industries and market segments (Harrington et al., 2013;

Matzler et al., 2004), it also has a strong temporal dimension

(Mikuli ´c and Prebeˇzac, 2011). Customers’ perceptions of attributes

change over time forcing attributes to migrate from one category to

another. For example, current excitement factors can become basic

factors as a result of becoming industry norms. As Kano (2001)

and Oliver (1997) suggest, such shift happens due to competi-

tion as all competing products or services duplicate each other’s

features, thus creating new “musts” perceived by consumers. How-

ever, knowing to which category attributes belong in a particular

industry is important for resource optimization purposes and also

to build competitive advantage (Kano, 2001). It is particularly true

for the highly competitive QSR segment.

2.4. Other studies focusing on QSR and restaurant attributes

One of the most renowned instruments that measures service

quality, a dimension that predicts satisfaction in restaurants, is

the DINESERV instrument (Stevens et al., 1995), which has strong

theoretical underpinnings from the aforementioned SERVQUAL

instrument (Parasuraman et al., 1988). While these instruments

strongly focus on service related dimensions such as reliability,

assurance,responsiveness,and more (Stevens et al., 1995), the

QSR industry is unique in nature because the interaction with the

employee is often less than one minute (Mathe, 2011) making the

total customer experience from service,product, and operational

quality of upmost importance. Past studies have focused on what

drives QSR satisfaction and loyalty,but not all studies attempted

to capture drivers of customer satisfaction immediately after the

customer experience,but instead used a sample that was sepa-

rate from those who recently encountered a QSR dining experience

(Harrington et al., 2013; Reich et al., 2005).

In the QSR industry, one of the most common methods of deter-

mining guests’ level of satisfaction is through mystery shops, or

other inspection type system implemented by restaurant chains

(DiPietro et al., 2011). In the inspection type method of evalua-

tion that DiPietro et al. (2011) tested, the relationship between the

scores on quality, cleanliness, and service failed to achieve a signif-

icant relationship with performance in QSR restaurants.Because

the information obtained from inspection scores was from only

one source, the authors suggest that not all of restaurants perfor-

mance should be placed on inspection scores only. Therefore, using

another method of performance analysis,like that in the present

study, could help to verify or provide new insights into where a QSR

unit is succeeding, or failing. One of the newer trends in restaurants

and other retail locations is to print a 1–800 number or provide cus-

tomers with a web address to share experience feedback from their

encounter. A representative from Jack in the Box, a QSR company,

reports receiving survey feedback approximately every 25 s from

consumers based on their experience, and within an hour to hour

and a half managers from every level within a restaurant company

can see if a unit is experiencing a problem (KSDK, 2013). Based on

the prior review and discussion, the study addresses the question:

What attributes are relevant to QSR guest satisfaction, and how are

each of these attributes affecting guest satisfaction?

3. Methods

3.1. Qualitative phase

Previous Kano’s categorization instruments included items that

dealt with a fine dining or casual dining experience in which con-

sumers eat in a dining room. Because this study focuses on QSRs at

the unit level, the researcher(s) generated a list of attributes that

would be conducive to the drive-thru experience at a QSR through

qualitative research. At QSRs, drive-thru business accounts for

more than 50–70% of revenues (QSR Magazine, 2012b), and satis-

faction attributes have yet to be explored. Therefore, in the summer

of 2011, an online panel through Yahoo! was created to explore

customer perceptions of fast food restaurants through qualitative

data techniques suggested by Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac (2011). The

group consisted of 50 members,who were fast food users across

the United States. The group was first asked “What is your favorite

fast food restaurant and why?” to initiate a group discussion.For

each participant,they were required to answer the question and

reply to another participant.For their responses,the participants

were sent a $5 gift card of their selection. The second and third

questions focused on the crux of the research for this study in which

participants were asked “What factors are important to you when

visiting a fast food restaurant” and also “Recall your last unsatis-

factory restaurant experience; what went wrong?” Both questions

were asked to help with the IPA flaw focusing on the causality

of importance leading to performance,or performance leading to

importance. Of the 50 participants, 42 responded and received a $10

gift card to their choice of QSR.The responses from this question

were then entered into Nvivo9 qualitative data software and were

analyzed for themes. The 42 participants then received a survey and

were asked to rate the importance of the themes that were gener-

ated from their responses. A sample item included “How important

is the taste of food when visiting a QSR”, or “How important is

speed of service when visiting a QSR.” Based on work by Matzler

and Sauerwein (2002) consumers were then asked to allocate 100

points to each of the ten attributes. In order of most points earned

to least points earned the attributes were ranked in the following

order (average points in parentheses):

• Tastes good/tastes fresh (20)

• Low cost (19)

• Hot food (16)

• Convenient location (12)

• Accuracy (11)

• Friendly service (8)

• Clean (7)

• Speed service (5)

• Wide range of items to choose (3)

• Understanding through the speaker (2)

These attributes were then assessed in terms of operational

applicability and included the quantitative survey. For example, at

the store level for a national QSR chain, the individual unit would

A few years later, there was Qualitative Research. And then, Mixed

Methods was born as a separate child of these parents” (p. 388). As

Creswell and Clark (2007) describe, there are generally four types

of designs in mixed methods: embedded, exploratory, triangulated,

and explanatory. The crux of this study focuses on the triangulated

approach,which utilizes different research approaches,methods,

and techniques in the same study (Hussey and Hussey, 1997;

Mangan et al., 2004).

The present study seeks to not only explore the PRCA method

in relation to QSR performance,but also proposes a new method

of performance planning that combines aspects of a qualitative

approach, the importance grid, and the regression results of the

PRCA, three of the primary methods Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac (2011)

suggest using for IPA classification. Consequently, the satisfaction

with the penalty and reward attributes in relation to the quad-

rants of the importance grid is assumed to better define customer

satisfaction. Since the method combines a qualitative approach

and quantitative approach, the results redefine the axes on which

attributes are plotted.

Applying Kano’s categorization in the QSR industry is impor-

tant because in addition to the fact that the categorization varies

between industries and market segments (Harrington et al., 2013;

Matzler et al., 2004), it also has a strong temporal dimension

(Mikuli ´c and Prebeˇzac, 2011). Customers’ perceptions of attributes

change over time forcing attributes to migrate from one category to

another. For example, current excitement factors can become basic

factors as a result of becoming industry norms. As Kano (2001)

and Oliver (1997) suggest, such shift happens due to competi-

tion as all competing products or services duplicate each other’s

features, thus creating new “musts” perceived by consumers. How-

ever, knowing to which category attributes belong in a particular

industry is important for resource optimization purposes and also

to build competitive advantage (Kano, 2001). It is particularly true

for the highly competitive QSR segment.

2.4. Other studies focusing on QSR and restaurant attributes

One of the most renowned instruments that measures service

quality, a dimension that predicts satisfaction in restaurants, is

the DINESERV instrument (Stevens et al., 1995), which has strong

theoretical underpinnings from the aforementioned SERVQUAL

instrument (Parasuraman et al., 1988). While these instruments

strongly focus on service related dimensions such as reliability,

assurance,responsiveness,and more (Stevens et al., 1995), the

QSR industry is unique in nature because the interaction with the

employee is often less than one minute (Mathe, 2011) making the

total customer experience from service,product, and operational

quality of upmost importance. Past studies have focused on what

drives QSR satisfaction and loyalty,but not all studies attempted

to capture drivers of customer satisfaction immediately after the

customer experience,but instead used a sample that was sepa-

rate from those who recently encountered a QSR dining experience

(Harrington et al., 2013; Reich et al., 2005).

In the QSR industry, one of the most common methods of deter-

mining guests’ level of satisfaction is through mystery shops, or

other inspection type system implemented by restaurant chains

(DiPietro et al., 2011). In the inspection type method of evalua-

tion that DiPietro et al. (2011) tested, the relationship between the

scores on quality, cleanliness, and service failed to achieve a signif-

icant relationship with performance in QSR restaurants.Because

the information obtained from inspection scores was from only

one source, the authors suggest that not all of restaurants perfor-

mance should be placed on inspection scores only. Therefore, using

another method of performance analysis,like that in the present

study, could help to verify or provide new insights into where a QSR

unit is succeeding, or failing. One of the newer trends in restaurants

and other retail locations is to print a 1–800 number or provide cus-

tomers with a web address to share experience feedback from their

encounter. A representative from Jack in the Box, a QSR company,

reports receiving survey feedback approximately every 25 s from

consumers based on their experience, and within an hour to hour

and a half managers from every level within a restaurant company

can see if a unit is experiencing a problem (KSDK, 2013). Based on

the prior review and discussion, the study addresses the question:

What attributes are relevant to QSR guest satisfaction, and how are

each of these attributes affecting guest satisfaction?

3. Methods

3.1. Qualitative phase

Previous Kano’s categorization instruments included items that

dealt with a fine dining or casual dining experience in which con-

sumers eat in a dining room. Because this study focuses on QSRs at

the unit level, the researcher(s) generated a list of attributes that

would be conducive to the drive-thru experience at a QSR through

qualitative research. At QSRs, drive-thru business accounts for

more than 50–70% of revenues (QSR Magazine, 2012b), and satis-

faction attributes have yet to be explored. Therefore, in the summer

of 2011, an online panel through Yahoo! was created to explore

customer perceptions of fast food restaurants through qualitative

data techniques suggested by Mikuli´c and Prebeˇzac (2011). The

group consisted of 50 members,who were fast food users across

the United States. The group was first asked “What is your favorite

fast food restaurant and why?” to initiate a group discussion.For

each participant,they were required to answer the question and

reply to another participant.For their responses,the participants

were sent a $5 gift card of their selection. The second and third

questions focused on the crux of the research for this study in which

participants were asked “What factors are important to you when

visiting a fast food restaurant” and also “Recall your last unsatis-

factory restaurant experience; what went wrong?” Both questions

were asked to help with the IPA flaw focusing on the causality

of importance leading to performance,or performance leading to

importance. Of the 50 participants, 42 responded and received a $10

gift card to their choice of QSR.The responses from this question

were then entered into Nvivo9 qualitative data software and were

analyzed for themes. The 42 participants then received a survey and

were asked to rate the importance of the themes that were gener-

ated from their responses. A sample item included “How important

is the taste of food when visiting a QSR”, or “How important is

speed of service when visiting a QSR.” Based on work by Matzler

and Sauerwein (2002) consumers were then asked to allocate 100

points to each of the ten attributes. In order of most points earned

to least points earned the attributes were ranked in the following

order (average points in parentheses):

• Tastes good/tastes fresh (20)

• Low cost (19)

• Hot food (16)

• Convenient location (12)

• Accuracy (11)

• Friendly service (8)

• Clean (7)

• Speed service (5)

• Wide range of items to choose (3)

• Understanding through the speaker (2)

These attributes were then assessed in terms of operational

applicability and included the quantitative survey. For example, at

the store level for a national QSR chain, the individual unit would

50 K. Mathe-Soulek et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 50 (2015) 46–54

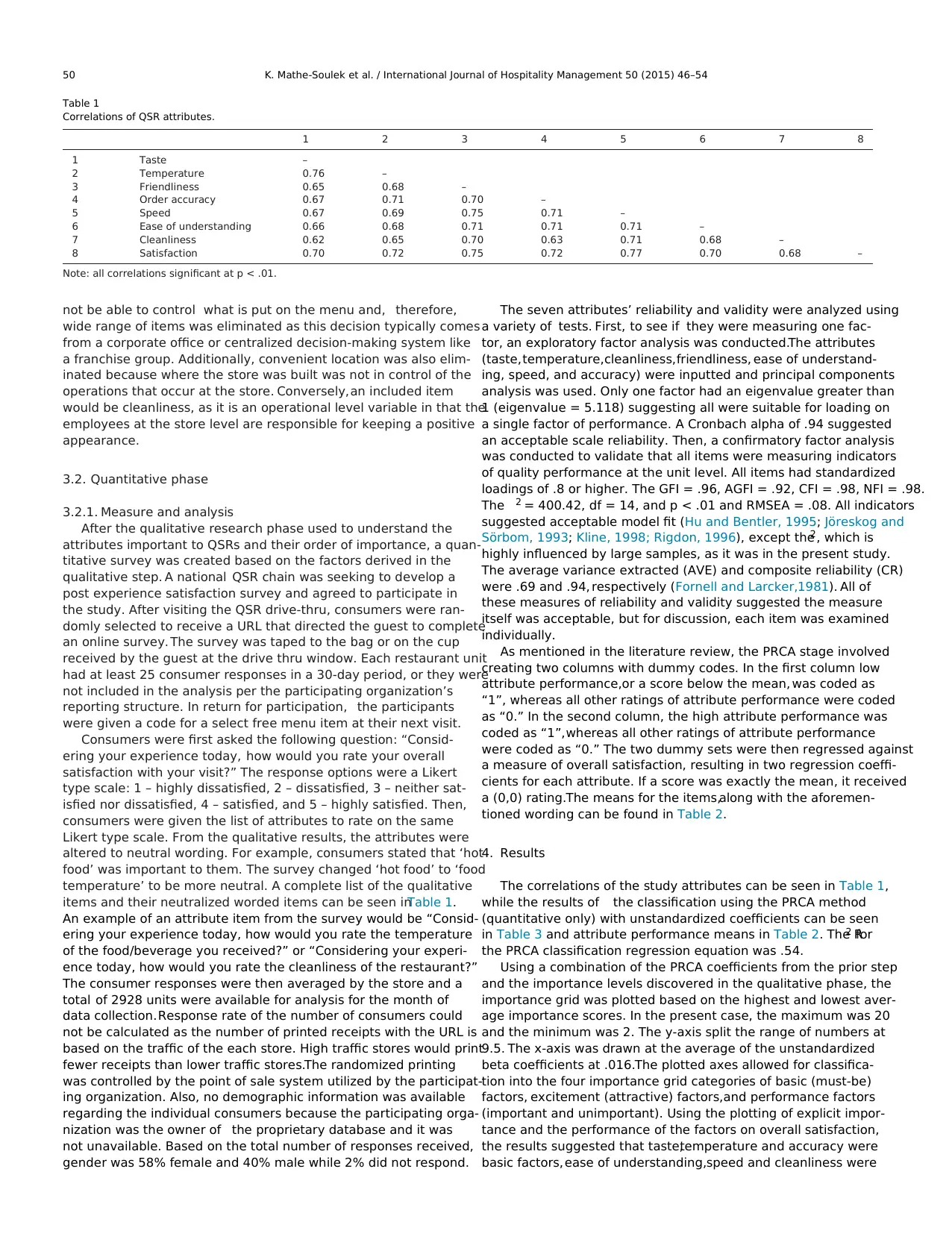

Table 1

Correlations of QSR attributes.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

1 Taste –

2 Temperature 0.76 –

3 Friendliness 0.65 0.68 –

4 Order accuracy 0.67 0.71 0.70 –

5 Speed 0.67 0.69 0.75 0.71 –

6 Ease of understanding 0.66 0.68 0.71 0.71 0.71 –

7 Cleanliness 0.62 0.65 0.70 0.63 0.71 0.68 –

8 Satisfaction 0.70 0.72 0.75 0.72 0.77 0.70 0.68 –

Note: all correlations significant at p < .01.

not be able to control what is put on the menu and, therefore,

wide range of items was eliminated as this decision typically comes

from a corporate office or centralized decision-making system like

a franchise group. Additionally, convenient location was also elim-

inated because where the store was built was not in control of the

operations that occur at the store. Conversely,an included item

would be cleanliness, as it is an operational level variable in that the

employees at the store level are responsible for keeping a positive

appearance.

3.2. Quantitative phase

3.2.1. Measure and analysis

After the qualitative research phase used to understand the

attributes important to QSRs and their order of importance, a quan-

titative survey was created based on the factors derived in the

qualitative step. A national QSR chain was seeking to develop a

post experience satisfaction survey and agreed to participate in

the study. After visiting the QSR drive-thru, consumers were ran-

domly selected to receive a URL that directed the guest to complete

an online survey. The survey was taped to the bag or on the cup

received by the guest at the drive thru window. Each restaurant unit

had at least 25 consumer responses in a 30-day period, or they were

not included in the analysis per the participating organization’s

reporting structure. In return for participation, the participants

were given a code for a select free menu item at their next visit.

Consumers were first asked the following question: “Consid-

ering your experience today, how would you rate your overall

satisfaction with your visit?” The response options were a Likert

type scale: 1 – highly dissatisfied, 2 – dissatisfied, 3 – neither sat-

isfied nor dissatisfied, 4 – satisfied, and 5 – highly satisfied. Then,

consumers were given the list of attributes to rate on the same

Likert type scale. From the qualitative results, the attributes were

altered to neutral wording. For example, consumers stated that ‘hot

food’ was important to them. The survey changed ‘hot food’ to ‘food

temperature’ to be more neutral. A complete list of the qualitative

items and their neutralized worded items can be seen inTable 1.

An example of an attribute item from the survey would be “Consid-

ering your experience today, how would you rate the temperature

of the food/beverage you received?” or “Considering your experi-

ence today, how would you rate the cleanliness of the restaurant?”

The consumer responses were then averaged by the store and a

total of 2928 units were available for analysis for the month of

data collection.Response rate of the number of consumers could

not be calculated as the number of printed receipts with the URL is

based on the traffic of the each store. High traffic stores would print

fewer receipts than lower traffic stores.The randomized printing

was controlled by the point of sale system utilized by the participat-

ing organization. Also, no demographic information was available

regarding the individual consumers because the participating orga-

nization was the owner of the proprietary database and it was

not unavailable. Based on the total number of responses received,

gender was 58% female and 40% male while 2% did not respond.

The seven attributes’ reliability and validity were analyzed using

a variety of tests. First, to see if they were measuring one fac-

tor, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted.The attributes

(taste,temperature,cleanliness,friendliness, ease of understand-

ing, speed, and accuracy) were inputted and principal components

analysis was used. Only one factor had an eigenvalue greater than

1 (eigenvalue = 5.118) suggesting all were suitable for loading on

a single factor of performance. A Cronbach alpha of .94 suggested

an acceptable scale reliability. Then, a confirmatory factor analysis

was conducted to validate that all items were measuring indicators

of quality performance at the unit level. All items had standardized

loadings of .8 or higher. The GFI = .96, AGFI = .92, CFI = .98, NFI = .98.

The 2 = 400.42, df = 14, and p < .01 and RMSEA = .08. All indicators

suggested acceptable model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1995; Jöreskog and

Sörbom, 1993; Kline, 1998; Rigdon, 1996), except the2, which is

highly influenced by large samples, as it was in the present study.

The average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR)

were .69 and .94, respectively (Fornell and Larcker,1981). All of

these measures of reliability and validity suggested the measure

itself was acceptable, but for discussion, each item was examined

individually.

As mentioned in the literature review, the PRCA stage involved

creating two columns with dummy codes. In the first column low

attribute performance,or a score below the mean, was coded as

“1”, whereas all other ratings of attribute performance were coded

as “0.” In the second column, the high attribute performance was

coded as “1”,whereas all other ratings of attribute performance

were coded as “0.” The two dummy sets were then regressed against

a measure of overall satisfaction, resulting in two regression coeffi-

cients for each attribute. If a score was exactly the mean, it received

a (0,0) rating.The means for the items,along with the aforemen-

tioned wording can be found in Table 2.

4. Results

The correlations of the study attributes can be seen in Table 1,

while the results of the classification using the PRCA method

(quantitative only) with unstandardized coefficients can be seen

in Table 3 and attribute performance means in Table 2. The R2 for

the PRCA classification regression equation was .54.

Using a combination of the PRCA coefficients from the prior step

and the importance levels discovered in the qualitative phase, the

importance grid was plotted based on the highest and lowest aver-

age importance scores. In the present case, the maximum was 20

and the minimum was 2. The y-axis split the range of numbers at

9.5. The x-axis was drawn at the average of the unstandardized

beta coefficients at .016.The plotted axes allowed for classifica-

tion into the four importance grid categories of basic (must-be)

factors, excitement (attractive) factors,and performance factors

(important and unimportant). Using the plotting of explicit impor-

tance and the performance of the factors on overall satisfaction,

the results suggested that taste,temperature and accuracy were

basic factors, ease of understanding,speed and cleanliness were

Table 1

Correlations of QSR attributes.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

1 Taste –

2 Temperature 0.76 –

3 Friendliness 0.65 0.68 –

4 Order accuracy 0.67 0.71 0.70 –

5 Speed 0.67 0.69 0.75 0.71 –

6 Ease of understanding 0.66 0.68 0.71 0.71 0.71 –

7 Cleanliness 0.62 0.65 0.70 0.63 0.71 0.68 –

8 Satisfaction 0.70 0.72 0.75 0.72 0.77 0.70 0.68 –

Note: all correlations significant at p < .01.

not be able to control what is put on the menu and, therefore,

wide range of items was eliminated as this decision typically comes

from a corporate office or centralized decision-making system like

a franchise group. Additionally, convenient location was also elim-

inated because where the store was built was not in control of the

operations that occur at the store. Conversely,an included item

would be cleanliness, as it is an operational level variable in that the

employees at the store level are responsible for keeping a positive

appearance.

3.2. Quantitative phase

3.2.1. Measure and analysis

After the qualitative research phase used to understand the

attributes important to QSRs and their order of importance, a quan-

titative survey was created based on the factors derived in the

qualitative step. A national QSR chain was seeking to develop a

post experience satisfaction survey and agreed to participate in

the study. After visiting the QSR drive-thru, consumers were ran-

domly selected to receive a URL that directed the guest to complete

an online survey. The survey was taped to the bag or on the cup

received by the guest at the drive thru window. Each restaurant unit

had at least 25 consumer responses in a 30-day period, or they were

not included in the analysis per the participating organization’s

reporting structure. In return for participation, the participants

were given a code for a select free menu item at their next visit.

Consumers were first asked the following question: “Consid-

ering your experience today, how would you rate your overall

satisfaction with your visit?” The response options were a Likert

type scale: 1 – highly dissatisfied, 2 – dissatisfied, 3 – neither sat-

isfied nor dissatisfied, 4 – satisfied, and 5 – highly satisfied. Then,

consumers were given the list of attributes to rate on the same

Likert type scale. From the qualitative results, the attributes were

altered to neutral wording. For example, consumers stated that ‘hot

food’ was important to them. The survey changed ‘hot food’ to ‘food

temperature’ to be more neutral. A complete list of the qualitative

items and their neutralized worded items can be seen inTable 1.

An example of an attribute item from the survey would be “Consid-

ering your experience today, how would you rate the temperature

of the food/beverage you received?” or “Considering your experi-

ence today, how would you rate the cleanliness of the restaurant?”

The consumer responses were then averaged by the store and a

total of 2928 units were available for analysis for the month of

data collection.Response rate of the number of consumers could

not be calculated as the number of printed receipts with the URL is

based on the traffic of the each store. High traffic stores would print

fewer receipts than lower traffic stores.The randomized printing

was controlled by the point of sale system utilized by the participat-

ing organization. Also, no demographic information was available

regarding the individual consumers because the participating orga-

nization was the owner of the proprietary database and it was

not unavailable. Based on the total number of responses received,

gender was 58% female and 40% male while 2% did not respond.

The seven attributes’ reliability and validity were analyzed using

a variety of tests. First, to see if they were measuring one fac-

tor, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted.The attributes

(taste,temperature,cleanliness,friendliness, ease of understand-

ing, speed, and accuracy) were inputted and principal components

analysis was used. Only one factor had an eigenvalue greater than

1 (eigenvalue = 5.118) suggesting all were suitable for loading on

a single factor of performance. A Cronbach alpha of .94 suggested

an acceptable scale reliability. Then, a confirmatory factor analysis

was conducted to validate that all items were measuring indicators

of quality performance at the unit level. All items had standardized

loadings of .8 or higher. The GFI = .96, AGFI = .92, CFI = .98, NFI = .98.

The 2 = 400.42, df = 14, and p < .01 and RMSEA = .08. All indicators

suggested acceptable model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1995; Jöreskog and

Sörbom, 1993; Kline, 1998; Rigdon, 1996), except the2, which is

highly influenced by large samples, as it was in the present study.

The average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR)

were .69 and .94, respectively (Fornell and Larcker,1981). All of

these measures of reliability and validity suggested the measure

itself was acceptable, but for discussion, each item was examined

individually.

As mentioned in the literature review, the PRCA stage involved

creating two columns with dummy codes. In the first column low

attribute performance,or a score below the mean, was coded as

“1”, whereas all other ratings of attribute performance were coded

as “0.” In the second column, the high attribute performance was

coded as “1”,whereas all other ratings of attribute performance

were coded as “0.” The two dummy sets were then regressed against

a measure of overall satisfaction, resulting in two regression coeffi-

cients for each attribute. If a score was exactly the mean, it received

a (0,0) rating.The means for the items,along with the aforemen-

tioned wording can be found in Table 2.

4. Results

The correlations of the study attributes can be seen in Table 1,

while the results of the classification using the PRCA method

(quantitative only) with unstandardized coefficients can be seen

in Table 3 and attribute performance means in Table 2. The R2 for

the PRCA classification regression equation was .54.

Using a combination of the PRCA coefficients from the prior step

and the importance levels discovered in the qualitative phase, the

importance grid was plotted based on the highest and lowest aver-

age importance scores. In the present case, the maximum was 20

and the minimum was 2. The y-axis split the range of numbers at

9.5. The x-axis was drawn at the average of the unstandardized

beta coefficients at .016.The plotted axes allowed for classifica-

tion into the four importance grid categories of basic (must-be)

factors, excitement (attractive) factors,and performance factors

(important and unimportant). Using the plotting of explicit impor-

tance and the performance of the factors on overall satisfaction,

the results suggested that taste,temperature and accuracy were

basic factors, ease of understanding,speed and cleanliness were

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

K. Mathe-Soulek et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 50 (2015) 46–54 51

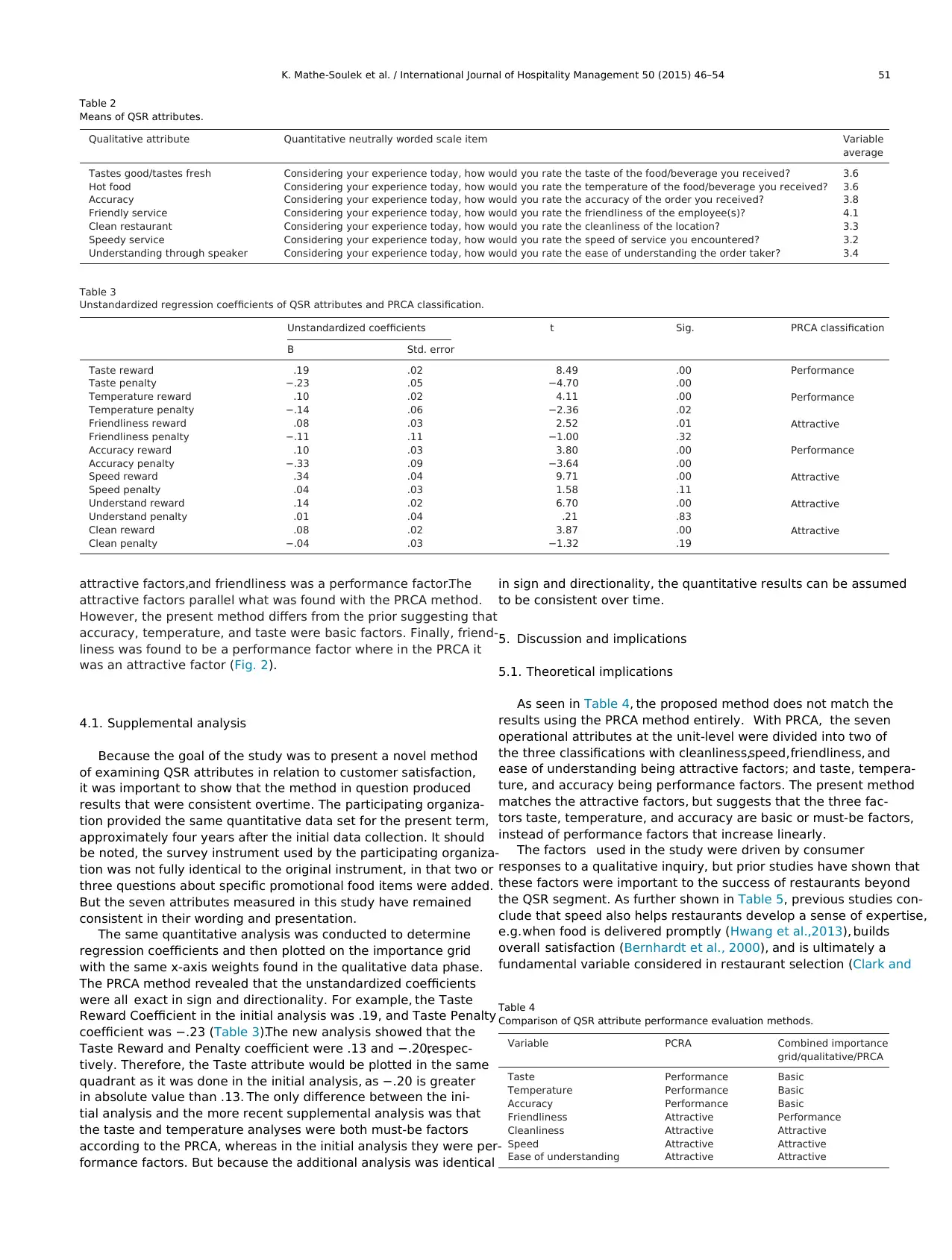

Table 2

Means of QSR attributes.

Qualitative attribute Quantitative neutrally worded scale item Variable

average

Tastes good/tastes fresh Considering your experience today, how would you rate the taste of the food/beverage you received? 3.6

Hot food Considering your experience today, how would you rate the temperature of the food/beverage you received? 3.6

Accuracy Considering your experience today, how would you rate the accuracy of the order you received? 3.8

Friendly service Considering your experience today, how would you rate the friendliness of the employee(s)? 4.1

Clean restaurant Considering your experience today, how would you rate the cleanliness of the location? 3.3

Speedy service Considering your experience today, how would you rate the speed of service you encountered? 3.2

Understanding through speaker Considering your experience today, how would you rate the ease of understanding the order taker? 3.4

Table 3

Unstandardized regression coefficients of QSR attributes and PRCA classification.

Unstandardized coefficients t Sig. PRCA classification

B Std. error

Taste reward .19 .02 8.49 .00 Performance

Taste penalty −.23 .05 −4.70 .00

Temperature reward .10 .02 4.11 .00 Performance

Temperature penalty −.14 .06 −2.36 .02

Friendliness reward .08 .03 2.52 .01 Attractive

Friendliness penalty −.11 .11 −1.00 .32

Accuracy reward .10 .03 3.80 .00 Performance

Accuracy penalty −.33 .09 −3.64 .00

Speed reward .34 .04 9.71 .00 Attractive

Speed penalty .04 .03 1.58 .11

Understand reward .14 .02 6.70 .00 Attractive

Understand penalty .01 .04 .21 .83

Clean reward .08 .02 3.87 .00 Attractive

Clean penalty −.04 .03 −1.32 .19

attractive factors,and friendliness was a performance factor.The

attractive factors parallel what was found with the PRCA method.

However, the present method differs from the prior suggesting that

accuracy, temperature, and taste were basic factors. Finally, friend-

liness was found to be a performance factor where in the PRCA it

was an attractive factor (Fig. 2).

4.1. Supplemental analysis

Because the goal of the study was to present a novel method

of examining QSR attributes in relation to customer satisfaction,

it was important to show that the method in question produced

results that were consistent overtime. The participating organiza-

tion provided the same quantitative data set for the present term,

approximately four years after the initial data collection. It should

be noted, the survey instrument used by the participating organiza-

tion was not fully identical to the original instrument, in that two or

three questions about specific promotional food items were added.

But the seven attributes measured in this study have remained

consistent in their wording and presentation.

The same quantitative analysis was conducted to determine

regression coefficients and then plotted on the importance grid

with the same x-axis weights found in the qualitative data phase.

The PRCA method revealed that the unstandardized coefficients

were all exact in sign and directionality. For example, the Taste

Reward Coefficient in the initial analysis was .19, and Taste Penalty

coefficient was −.23 (Table 3).The new analysis showed that the

Taste Reward and Penalty coefficient were .13 and −.20,respec-

tively. Therefore, the Taste attribute would be plotted in the same

quadrant as it was done in the initial analysis, as −.20 is greater

in absolute value than .13. The only difference between the ini-

tial analysis and the more recent supplemental analysis was that

the taste and temperature analyses were both must-be factors

according to the PRCA, whereas in the initial analysis they were per-

formance factors. But because the additional analysis was identical

in sign and directionality, the quantitative results can be assumed

to be consistent over time.

5. Discussion and implications

5.1. Theoretical implications

As seen in Table 4, the proposed method does not match the

results using the PRCA method entirely. With PRCA, the seven

operational attributes at the unit-level were divided into two of

the three classifications with cleanliness,speed,friendliness, and

ease of understanding being attractive factors; and taste, tempera-

ture, and accuracy being performance factors. The present method

matches the attractive factors, but suggests that the three fac-

tors taste, temperature, and accuracy are basic or must-be factors,

instead of performance factors that increase linearly.

The factors used in the study were driven by consumer

responses to a qualitative inquiry, but prior studies have shown that

these factors were important to the success of restaurants beyond

the QSR segment. As further shown in Table 5, previous studies con-

clude that speed also helps restaurants develop a sense of expertise,

e.g.when food is delivered promptly (Hwang et al.,2013), builds

overall satisfaction (Bernhardt et al., 2000), and is ultimately a

fundamental variable considered in restaurant selection (Clark and

Table 4

Comparison of QSR attribute performance evaluation methods.

Variable PCRA Combined importance

grid/qualitative/PRCA

Taste Performance Basic

Temperature Performance Basic

Accuracy Performance Basic

Friendliness Attractive Performance

Cleanliness Attractive Attractive

Speed Attractive Attractive

Ease of understanding Attractive Attractive

Table 2

Means of QSR attributes.

Qualitative attribute Quantitative neutrally worded scale item Variable

average

Tastes good/tastes fresh Considering your experience today, how would you rate the taste of the food/beverage you received? 3.6

Hot food Considering your experience today, how would you rate the temperature of the food/beverage you received? 3.6

Accuracy Considering your experience today, how would you rate the accuracy of the order you received? 3.8

Friendly service Considering your experience today, how would you rate the friendliness of the employee(s)? 4.1

Clean restaurant Considering your experience today, how would you rate the cleanliness of the location? 3.3

Speedy service Considering your experience today, how would you rate the speed of service you encountered? 3.2

Understanding through speaker Considering your experience today, how would you rate the ease of understanding the order taker? 3.4

Table 3

Unstandardized regression coefficients of QSR attributes and PRCA classification.

Unstandardized coefficients t Sig. PRCA classification

B Std. error

Taste reward .19 .02 8.49 .00 Performance

Taste penalty −.23 .05 −4.70 .00

Temperature reward .10 .02 4.11 .00 Performance

Temperature penalty −.14 .06 −2.36 .02

Friendliness reward .08 .03 2.52 .01 Attractive

Friendliness penalty −.11 .11 −1.00 .32

Accuracy reward .10 .03 3.80 .00 Performance

Accuracy penalty −.33 .09 −3.64 .00

Speed reward .34 .04 9.71 .00 Attractive

Speed penalty .04 .03 1.58 .11

Understand reward .14 .02 6.70 .00 Attractive

Understand penalty .01 .04 .21 .83

Clean reward .08 .02 3.87 .00 Attractive

Clean penalty −.04 .03 −1.32 .19

attractive factors,and friendliness was a performance factor.The

attractive factors parallel what was found with the PRCA method.

However, the present method differs from the prior suggesting that

accuracy, temperature, and taste were basic factors. Finally, friend-

liness was found to be a performance factor where in the PRCA it

was an attractive factor (Fig. 2).

4.1. Supplemental analysis

Because the goal of the study was to present a novel method

of examining QSR attributes in relation to customer satisfaction,

it was important to show that the method in question produced

results that were consistent overtime. The participating organiza-

tion provided the same quantitative data set for the present term,

approximately four years after the initial data collection. It should

be noted, the survey instrument used by the participating organiza-

tion was not fully identical to the original instrument, in that two or

three questions about specific promotional food items were added.

But the seven attributes measured in this study have remained

consistent in their wording and presentation.

The same quantitative analysis was conducted to determine

regression coefficients and then plotted on the importance grid

with the same x-axis weights found in the qualitative data phase.

The PRCA method revealed that the unstandardized coefficients

were all exact in sign and directionality. For example, the Taste

Reward Coefficient in the initial analysis was .19, and Taste Penalty

coefficient was −.23 (Table 3).The new analysis showed that the

Taste Reward and Penalty coefficient were .13 and −.20,respec-

tively. Therefore, the Taste attribute would be plotted in the same