E-commerce success model Information 2022

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/25

|58

|22954

|28

AI Summary

Please develop a table of at least 25 articles Citation Research objectives Methodology Findings Conclusion/Future research Find answers to these questions 1- what are the important infrastructure needed in a company and a country to make e-commerce work 2- success factors for e-commerce adoption 3- e-commerce in airlines 4- code sharing 5- competiteve advantage 6- the personalization through e- commerce all those related chapter 2

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Accepted Manuscript

Title: The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The

integration of the commitment-trust theory and e-commerce

success model

Author: Wei-Tsong Wang Yi-Shun Wang En-Ru Liu

PII: S0378-7206(16)30003-9

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.im.2016.01.006

Reference: INFMAN 2877

To appear in: INFMAN

Received date: 16-3-2015

Revised date: 19-1-2016

Accepted date: 31-1-2016

Please cite this article as: W.-T. Wang, Y.-S. Wang, E.-R. Liu, The stickiness

intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment-trust

theory and e-commerce success model, Information and Management (2016),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.01.006

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication.

As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript.

The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof

before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process

errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that

apply to the journal pertain.

Title: The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The

integration of the commitment-trust theory and e-commerce

success model

Author: Wei-Tsong Wang Yi-Shun Wang En-Ru Liu

PII: S0378-7206(16)30003-9

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.im.2016.01.006

Reference: INFMAN 2877

To appear in: INFMAN

Received date: 16-3-2015

Revised date: 19-1-2016

Accepted date: 31-1-2016

Please cite this article as: W.-T. Wang, Y.-S. Wang, E.-R. Liu, The stickiness

intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment-trust

theory and e-commerce success model, Information and Management (2016),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.01.006

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication.

As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript.

The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof

before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process

errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that

apply to the journal pertain.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Page 1 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

1

Title:

The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment-trust

theory and e-commerce success model.

Authors:

Wei-Tsong Wang (Corresponding author)

Associate Professor, Department of Industrial and Information Management,

National Cheng Kung University,

1st University Road, Tainan 701, Taiwan;

Tel: +886-6-2757575 ext.53122; Fax: +886-6-2362162

wtwang@mail.ncku.edu.tw

Yi-Shun Wang

Professor, Department of Information Management,

National Changhua University of Education,

No.2, Shi-Da Road, Changhua City 500, Taiwan

Tel: +886-4-7232105 ext.7331; Fax: +886-4-7211162

yswang@cc.ncue.edu.tw

En-Ru Liu

Institute of Industrial and Information Management,

National Cheng Kung University,

1st University Road, Tainan 701, Taiwan

Accepted Manuscript

1

Title:

The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment-trust

theory and e-commerce success model.

Authors:

Wei-Tsong Wang (Corresponding author)

Associate Professor, Department of Industrial and Information Management,

National Cheng Kung University,

1st University Road, Tainan 701, Taiwan;

Tel: +886-6-2757575 ext.53122; Fax: +886-6-2362162

wtwang@mail.ncku.edu.tw

Yi-Shun Wang

Professor, Department of Information Management,

National Changhua University of Education,

No.2, Shi-Da Road, Changhua City 500, Taiwan

Tel: +886-4-7232105 ext.7331; Fax: +886-4-7211162

yswang@cc.ncue.edu.tw

En-Ru Liu

Institute of Industrial and Information Management,

National Cheng Kung University,

1st University Road, Tainan 701, Taiwan

Page 2 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

2

Tel: +886-6-2757575 ext.53120-109; Fax: +886-6-2362162

p80511427@gmail.com

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback

on this paper. The authors also thank the administrators of the online forums and websites

studied for their support and the survey respondents for providing valuable data. This

research was funded by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan [grant number: MOST

103-2410-H-006-043].

Accepted Manuscript

2

Tel: +886-6-2757575 ext.53120-109; Fax: +886-6-2362162

p80511427@gmail.com

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback

on this paper. The authors also thank the administrators of the online forums and websites

studied for their support and the survey respondents for providing valuable data. This

research was funded by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan [grant number: MOST

103-2410-H-006-043].

Page 3 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

3

The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment-trust

theory and e-commerce success model

Abstract:

The success of consumer-to-business (C2B) group-buying websites (GBWs) relies heavily on

consumers’ relationships with the GBWs, a topic not yet adequately investigated in the existing

literature. Additionally, there is a transition from the technical and/or transactional views in

e-commerce studies to a relational view. However, such studies have focused on

business-to-consumer contexts. By integrating the e-commerce success model and commitment-trust

theory, we developed a model of GBW stickiness, which is examined using data collected from 280

GBW users. The results indicated that relationship commitment, trust, and satisfaction were key

determinants of stickiness intention. Theoretical and practical implications are also discussed.

Keywords: group-buying, D&M IS success model, e-commerce success model,commitment-trust

theory, relationship commitment.

1. Introduction

Online group-buying is considered to be a unique, innovative, and especially interesting online

consumer-to-business (C2B) business model, because it enables buyers to obtain volume discounts

and helps sellers to effectively sell a considerable number of items [57, 58, 59]. The main idea of this

business model to is to recruit enough people with the same needs to generate a sufficient volume of

orders to create the leverage needed to acquire a lower transaction price [57]. In the late 1990s,

Mobshop (originally known as Accompany.com) and Mercata.com were the first two group-buying

websites (GBWs), and these companies and some others GBWs were able to attract a large amount of

venture capital funding [57]. Unfortunately, these companies soon went out of business in the early

2000s for various reasons, including rapid expansion, fierce competition, and an inability to articulate

Accepted Manuscript

3

The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment-trust

theory and e-commerce success model

Abstract:

The success of consumer-to-business (C2B) group-buying websites (GBWs) relies heavily on

consumers’ relationships with the GBWs, a topic not yet adequately investigated in the existing

literature. Additionally, there is a transition from the technical and/or transactional views in

e-commerce studies to a relational view. However, such studies have focused on

business-to-consumer contexts. By integrating the e-commerce success model and commitment-trust

theory, we developed a model of GBW stickiness, which is examined using data collected from 280

GBW users. The results indicated that relationship commitment, trust, and satisfaction were key

determinants of stickiness intention. Theoretical and practical implications are also discussed.

Keywords: group-buying, D&M IS success model, e-commerce success model,commitment-trust

theory, relationship commitment.

1. Introduction

Online group-buying is considered to be a unique, innovative, and especially interesting online

consumer-to-business (C2B) business model, because it enables buyers to obtain volume discounts

and helps sellers to effectively sell a considerable number of items [57, 58, 59]. The main idea of this

business model to is to recruit enough people with the same needs to generate a sufficient volume of

orders to create the leverage needed to acquire a lower transaction price [57]. In the late 1990s,

Mobshop (originally known as Accompany.com) and Mercata.com were the first two group-buying

websites (GBWs), and these companies and some others GBWs were able to attract a large amount of

venture capital funding [57]. Unfortunately, these companies soon went out of business in the early

2000s for various reasons, including rapid expansion, fierce competition, and an inability to articulate

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Page 4 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

4

promising revenue models [13]. Surprisingly, group-buying businesses have been trying to make a

comeback in recent years [58], and the number of GBWs is rapidly increasing around the globe,

particularly in East Asia [57]. Recent statistics indicate that by 2015, revenue for the online

group-buying market will reach 4.17 billion dollars in the United States. Managers of many

commercial websites have put efforts into developing their own group-buying business models by

providing group-buying functions on their websites (such as Yahoo!) or by merging with foreign

group-buying websites to pursue foreign markets (such as Groupon’s merger with Atlaspost.com to

enter the Asian online group-buying market) [16]. These developments suggestthat although this

business model has not yet proven to be a long-term success, it appears to have a bright future.

However, as the size of the online group-buying market continues to grow, the accompanying

competition has made it increasingly difficult for GBWs to retain their customers [16]. Some statistics

indicate that in the first quarter of 2012, more than 70% (approximately 4,000) of the GBWs in China

went out of business or switched to other online business models because of consumer dissatisfaction

and difficulties in building consumer loyalty. Online group-buying activities tend to face risk- and

trust-related issues that significantly affect online consumers’ participation intention to and that are

not present in other online retailing mechanisms [58]. For example, compared to other online

transaction mechanisms, consumers of online group-buying activities are more uncertain about the

final purchasing price or whether the group-buying initiatives will succeed, because an insufficient

number of group-buying participants may lead to a relatively higher purchasing price or even a failed

group-buying initiative. Participants may also suffer from financial losses because of the

incompetence of the online group-buying intermediaries in preventing deceitful behaviors.

Consequently, the risk and trust issues related to online group-buying deserve close examination from

a relational perspective.

Despite the practical relevance outlined above, the findings of the extent information system (IS)

literature are insufficient in terms of offering a holistic theoretical ground for understanding consumer

intentions regarding the use of GBWs. While electronic commerce (e-commerce) professionals find it

Accepted Manuscript

4

promising revenue models [13]. Surprisingly, group-buying businesses have been trying to make a

comeback in recent years [58], and the number of GBWs is rapidly increasing around the globe,

particularly in East Asia [57]. Recent statistics indicate that by 2015, revenue for the online

group-buying market will reach 4.17 billion dollars in the United States. Managers of many

commercial websites have put efforts into developing their own group-buying business models by

providing group-buying functions on their websites (such as Yahoo!) or by merging with foreign

group-buying websites to pursue foreign markets (such as Groupon’s merger with Atlaspost.com to

enter the Asian online group-buying market) [16]. These developments suggestthat although this

business model has not yet proven to be a long-term success, it appears to have a bright future.

However, as the size of the online group-buying market continues to grow, the accompanying

competition has made it increasingly difficult for GBWs to retain their customers [16]. Some statistics

indicate that in the first quarter of 2012, more than 70% (approximately 4,000) of the GBWs in China

went out of business or switched to other online business models because of consumer dissatisfaction

and difficulties in building consumer loyalty. Online group-buying activities tend to face risk- and

trust-related issues that significantly affect online consumers’ participation intention to and that are

not present in other online retailing mechanisms [58]. For example, compared to other online

transaction mechanisms, consumers of online group-buying activities are more uncertain about the

final purchasing price or whether the group-buying initiatives will succeed, because an insufficient

number of group-buying participants may lead to a relatively higher purchasing price or even a failed

group-buying initiative. Participants may also suffer from financial losses because of the

incompetence of the online group-buying intermediaries in preventing deceitful behaviors.

Consequently, the risk and trust issues related to online group-buying deserve close examination from

a relational perspective.

Despite the practical relevance outlined above, the findings of the extent information system (IS)

literature are insufficient in terms of offering a holistic theoretical ground for understanding consumer

intentions regarding the use of GBWs. While electronic commerce (e-commerce) professionals find it

Page 5 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

5

increasingly difficult to motivate online consumers to stick to a specific website, significant efforts

have been made to evaluate the success of e-commerce websites from technical/IS and/or

transactional perspectives [80, 109, 117]. The technical/IS view, which is also referred to as the

socio-technical view, presumes that issues related to the user adoption of IS/websites are to be

investigated by primarily considering how the design and use of IS/websites can fit with

organizational objectives by being an integral part of organizational communication, cooperation, and

operational arrangement mechanisms (i.e., the social/organizational role of IS)[50]. Additionally,

Petter et al. [94] indicate that considerations related to consumer benefits (i.e., the transactional view)

and consumer use of e-commerce systems (i.e., the technical view) are essential in assessing the

success of IS in various contexts.

However, in addition to the technical perspective, there has been a transition from a transactional

view, which emphasizes the post-purchase satisfaction paradigm, to a relational view, which

emphasizes the importance of social and psychological factors (e.g., trust and commitment), in

studies of the interactions between online consumers and e-commerce websites [72]. Satisfaction

alone may not always guarantee repatronage or the continued use of an e-commerce website [57, 93].

When consumers have convenient access to alternative online vendors that have features that are

similar to or indistinguishable from their original online vendors, satisfaction may not be enough to

prevent these consumers from switching to these alternatives [72]. Consequently, the formation of a

relational bond is critical to discouraging the switching behaviors of online consumers [16].

Additionally, Zhou et al. [119] argue that satisfaction (i.e., a transactional factor) is backward-looking

and more transitory than commitment, and reflects a response to day-to-day events and contextual

changes. In contrast, commitment (i.e., a relational factor) is forward-looking and more enduring over

time in influencing individuals’ behavioral intentions, free from the influences of short-term changes

in situational elements. To sum up, while the transactional view focuses on the one-time provision of

various benefits and favorable experiences to online consumers during the interactions they have with

e-vendors/websites, the relational view primarily emphasizes the development and maintenance of

Accepted Manuscript

5

increasingly difficult to motivate online consumers to stick to a specific website, significant efforts

have been made to evaluate the success of e-commerce websites from technical/IS and/or

transactional perspectives [80, 109, 117]. The technical/IS view, which is also referred to as the

socio-technical view, presumes that issues related to the user adoption of IS/websites are to be

investigated by primarily considering how the design and use of IS/websites can fit with

organizational objectives by being an integral part of organizational communication, cooperation, and

operational arrangement mechanisms (i.e., the social/organizational role of IS)[50]. Additionally,

Petter et al. [94] indicate that considerations related to consumer benefits (i.e., the transactional view)

and consumer use of e-commerce systems (i.e., the technical view) are essential in assessing the

success of IS in various contexts.

However, in addition to the technical perspective, there has been a transition from a transactional

view, which emphasizes the post-purchase satisfaction paradigm, to a relational view, which

emphasizes the importance of social and psychological factors (e.g., trust and commitment), in

studies of the interactions between online consumers and e-commerce websites [72]. Satisfaction

alone may not always guarantee repatronage or the continued use of an e-commerce website [57, 93].

When consumers have convenient access to alternative online vendors that have features that are

similar to or indistinguishable from their original online vendors, satisfaction may not be enough to

prevent these consumers from switching to these alternatives [72]. Consequently, the formation of a

relational bond is critical to discouraging the switching behaviors of online consumers [16].

Additionally, Zhou et al. [119] argue that satisfaction (i.e., a transactional factor) is backward-looking

and more transitory than commitment, and reflects a response to day-to-day events and contextual

changes. In contrast, commitment (i.e., a relational factor) is forward-looking and more enduring over

time in influencing individuals’ behavioral intentions, free from the influences of short-term changes

in situational elements. To sum up, while the transactional view focuses on the one-time provision of

various benefits and favorable experiences to online consumers during the interactions they have with

e-vendors/websites, the relational view primarily emphasizes the development and maintenance of

Page 6 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

6

sustainable and favorable relationships between online consumers and e-vendors/websites through

personalized social and psychological exchanges [72, 102].

Commitment-trust theory [86] enables researchers to consider the formation and the effects of

the relational bond between two exchange parties by proposing relationship commitment and trust as

key factors that influence the consumers’ attitudes toward a particular business. Commitment-trust

theory has drawn the attention of e-commerce researchers [53, 72, 87, 106]. However, e-commerce

studies that adopt the relational view primarily focus on business-to-consumer (B2C) or

business-to-business (B2B) contexts and emphasize the effects of trust on consumer behaviors [2, 62,

103]. Very few of these studies focus on C2B contexts, such as consumer-initiated online

group-buying transactions [16, 63, 104], particularly from the perspective of relationship

commitments among the various parties. Consequently, the interesting and important issue of why

some GBWs fail while others survive deserves to be investigated by specific research efforts using

theoretical analysis [15]. With that motivation, this study aims to address the following research

question (RQ):

RQ: What factors affect online consumers’ intention to stick with a specific GBW for participating in

online group-buying activities?

To answer this question, the primary purposes of this study are thus twofold. First, the transition

from the technical and/or transactional views to a relational view indicates that the key to the success

of e-commerce websites lies not only in customer satisfaction, but also in the relational attachments

of online customers to these websites. Consequently,this study develops a theoretical model to

evaluate the success of e-commerce websites by integrating the technical, transactional, and relational

views using the commitment-trust theory [86] and e-commerce success model [109] as the theoretical

basis. In addition to the emphasis on the importance of relationship commitment and trust in

predicting volitional user behavior of online services,the proposed set of antecedents (e.g., cost-,

benefits-, and value-related factors) of commitment-trust theory implicitly incorporate the notion of

the transactional view. This makes the commitment-trust theory an appropriate theory that

Accepted Manuscript

6

sustainable and favorable relationships between online consumers and e-vendors/websites through

personalized social and psychological exchanges [72, 102].

Commitment-trust theory [86] enables researchers to consider the formation and the effects of

the relational bond between two exchange parties by proposing relationship commitment and trust as

key factors that influence the consumers’ attitudes toward a particular business. Commitment-trust

theory has drawn the attention of e-commerce researchers [53, 72, 87, 106]. However, e-commerce

studies that adopt the relational view primarily focus on business-to-consumer (B2C) or

business-to-business (B2B) contexts and emphasize the effects of trust on consumer behaviors [2, 62,

103]. Very few of these studies focus on C2B contexts, such as consumer-initiated online

group-buying transactions [16, 63, 104], particularly from the perspective of relationship

commitments among the various parties. Consequently, the interesting and important issue of why

some GBWs fail while others survive deserves to be investigated by specific research efforts using

theoretical analysis [15]. With that motivation, this study aims to address the following research

question (RQ):

RQ: What factors affect online consumers’ intention to stick with a specific GBW for participating in

online group-buying activities?

To answer this question, the primary purposes of this study are thus twofold. First, the transition

from the technical and/or transactional views to a relational view indicates that the key to the success

of e-commerce websites lies not only in customer satisfaction, but also in the relational attachments

of online customers to these websites. Consequently,this study develops a theoretical model to

evaluate the success of e-commerce websites by integrating the technical, transactional, and relational

views using the commitment-trust theory [86] and e-commerce success model [109] as the theoretical

basis. In addition to the emphasis on the importance of relationship commitment and trust in

predicting volitional user behavior of online services,the proposed set of antecedents (e.g., cost-,

benefits-, and value-related factors) of commitment-trust theory implicitly incorporate the notion of

the transactional view. This makes the commitment-trust theory an appropriate theory that

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Page 7 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

7

complements the transactional view from a relational marketing perspective. Additionally, the

e-commerce success model, by integrating the technical/IS and transactional views, depicts

individuals’ perceptions regarding their interactions with the IS/websites, which resemble their

evaluation of their relationships with the IS/websites. This feature makes the e-commerce success

model an important theoretical base for this study in terms of integrating the technical, transactional,

and relational views by complementing the insufficiency of the commitment-trust theory in terms of

capturing the antecedents of commitment and trust that are associated with online business contexts.

Second, relatively few studies have empirically examined issues related to customer retention in

online C2B contexts. Consequently, this study empirically examines the proposed model in the

context of online group-buying activities via GBWs.

This study contributes to both the emerging online group-buying literature and general

e-commerce literature in a number of ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, this study is among

the first to provide an integrated theoretical insights into understanding online consumers’ stickiness

intention regarding GBWs by incorporating antecedent and intervening factors that are critical to the

online group-buying context from technical, transactional, and relational perspectives. Second, while

the e-commerce success model has been frequently applied to studies of post-purchase adoption in

various e-commerce contexts [20, 105, 109], our findings contribute to this model by adopting and

validating it in the online group-buying (C2B) context. Finally, although the commitment-trust theory

has been partially applied to e-commerce studies [62, 72, 87, 103, 106], this study applied it to

simultaneously investigate the effects of relationship commitment and trust on consumers’ intention

regarding the use of GBWs, thus extending its applicability.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1 Online group-buying

The core concept of online group-buying is that gathering a group of consumers with the same

Accepted Manuscript

7

complements the transactional view from a relational marketing perspective. Additionally, the

e-commerce success model, by integrating the technical/IS and transactional views, depicts

individuals’ perceptions regarding their interactions with the IS/websites, which resemble their

evaluation of their relationships with the IS/websites. This feature makes the e-commerce success

model an important theoretical base for this study in terms of integrating the technical, transactional,

and relational views by complementing the insufficiency of the commitment-trust theory in terms of

capturing the antecedents of commitment and trust that are associated with online business contexts.

Second, relatively few studies have empirically examined issues related to customer retention in

online C2B contexts. Consequently, this study empirically examines the proposed model in the

context of online group-buying activities via GBWs.

This study contributes to both the emerging online group-buying literature and general

e-commerce literature in a number of ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, this study is among

the first to provide an integrated theoretical insights into understanding online consumers’ stickiness

intention regarding GBWs by incorporating antecedent and intervening factors that are critical to the

online group-buying context from technical, transactional, and relational perspectives. Second, while

the e-commerce success model has been frequently applied to studies of post-purchase adoption in

various e-commerce contexts [20, 105, 109], our findings contribute to this model by adopting and

validating it in the online group-buying (C2B) context. Finally, although the commitment-trust theory

has been partially applied to e-commerce studies [62, 72, 87, 103, 106], this study applied it to

simultaneously investigate the effects of relationship commitment and trust on consumers’ intention

regarding the use of GBWs, thus extending its applicability.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1 Online group-buying

The core concept of online group-buying is that gathering a group of consumers with the same

Page 8 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

8

needs and then leveraging their collective bargaining power to lower the prices for the products or

services of interest [57]. The bargaining power thus grows with the number of consumers in a group.

Demand aggregation and volume discounting are thus key features of this business model [3]. The

primary value proposition of online group-buying to consumers is making a deal at a lower price by

connecting and uniting individuals who share the same needs on certain products/services in a

specific timeframe via the Internet to use their collective bargaining power to negotiate with the

sellers, and thus get volume discounts that were traditionally the privilege of bulk buyers [60, 78].

Additionally, sellers who participate in group-buying activities can be benefited by creating leverage

to reduce the cost of acquiring customers, which makes it possible to create a win-win situations for

both buyers and sellers [57].

Although the online group-buying model has been used in B2B contexts, its primary use is in the

purchase activities of end consumers, and the process is mostly accomplished via online

intermediaries. Online group-buying opportunities can either be marketer-initiated transactions, which

include merchant-initiated transactions and independent-third-party-initiated transactions, or

consumer-initiated transactions [16, 58, 63]. Consumer-initiated transactions are the most popular

forms of online group-buying, and this type of transaction is considered to represent a C2B business

model [13, 14]. In a consumer-initiated transaction, a consumer (i.e., the initiator), as the

representative of a group of consumers with the same needs, must actively negotiate with multiple

sellers for a discounted price on the product of interest, which is similar to asking sellers to bid on a

product for a group of potential buyers. Quantity discount is the major motivation of this

group-buying activity, and the pricing of this quantity order may either be a proposal sent by sellers or

the results of the negotiation process between the initiator and the sellers [13]. In this process, the

initiator may continue to put efforts into recruiting more consumers to join this shopping group, via

the use of online intermediaries, to meet the quantity requirement of a particular seller that is offering

the most favorable quantity discount. Eventually, if the quantity requirement is met before a specified

deadline, the shopping group closes the deal with this particular seller and a group-buying transaction

Accepted Manuscript

8

needs and then leveraging their collective bargaining power to lower the prices for the products or

services of interest [57]. The bargaining power thus grows with the number of consumers in a group.

Demand aggregation and volume discounting are thus key features of this business model [3]. The

primary value proposition of online group-buying to consumers is making a deal at a lower price by

connecting and uniting individuals who share the same needs on certain products/services in a

specific timeframe via the Internet to use their collective bargaining power to negotiate with the

sellers, and thus get volume discounts that were traditionally the privilege of bulk buyers [60, 78].

Additionally, sellers who participate in group-buying activities can be benefited by creating leverage

to reduce the cost of acquiring customers, which makes it possible to create a win-win situations for

both buyers and sellers [57].

Although the online group-buying model has been used in B2B contexts, its primary use is in the

purchase activities of end consumers, and the process is mostly accomplished via online

intermediaries. Online group-buying opportunities can either be marketer-initiated transactions, which

include merchant-initiated transactions and independent-third-party-initiated transactions, or

consumer-initiated transactions [16, 58, 63]. Consumer-initiated transactions are the most popular

forms of online group-buying, and this type of transaction is considered to represent a C2B business

model [13, 14]. In a consumer-initiated transaction, a consumer (i.e., the initiator), as the

representative of a group of consumers with the same needs, must actively negotiate with multiple

sellers for a discounted price on the product of interest, which is similar to asking sellers to bid on a

product for a group of potential buyers. Quantity discount is the major motivation of this

group-buying activity, and the pricing of this quantity order may either be a proposal sent by sellers or

the results of the negotiation process between the initiator and the sellers [13]. In this process, the

initiator may continue to put efforts into recruiting more consumers to join this shopping group, via

the use of online intermediaries, to meet the quantity requirement of a particular seller that is offering

the most favorable quantity discount. Eventually, if the quantity requirement is met before a specified

deadline, the shopping group closes the deal with this particular seller and a group-buying transaction

Page 9 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

9

is completed. This study focuses on consumer-initiated group-buying transactions.

The online group-buying mechanism is different from that of the traditional quantity discounts for

two main reasons [15, 58, 78]. One is that in a traditional quantity discount situation the seller sets its

own optimal discount quantity and price, while in a group-buying context the price is determined

based on the total quantity of the product/service that all the participating buyers want to buy. The

other is related to the special dynamics of the online group-buying model. In a traditional quantity

discount situation, individual buyers place their own orders based on the information provided by the

seller. However, in a group-buying context in which price is dynamic and uncertain (depending on the

collective bargaining power of the buyer group at the deadline of the group-buying activity), one

buyer’s order would affect the other buyers’ benefits from their participation of the group-buying

activity. Therefore, on many occasions potential buyers may not participate in an online group-buying

activity unless they see evidence that other buyers are participating enthusiastically, and that the

quantity discount threshold they desire is highly likely to be reached.

Online group-buying behaviors are also different from those of group bargaining or negotiations.

For example, negotiations among groups of companies tend to involve multifaceted issues, and thus

different negotiation strategies and decision rules may be applied based on the situations [8].

Additionally, individual members of a group may join the group for diverse motivations,and thus

integrative agreements that can maximize the joint benefits of the individual members in a group may

be mostly elusive [8]. Moreover, consumer groups that are formed on group-buying websites are

relatively unstable compared to traditional social or consumer cooperatives [63]. Consumers’ lack of

access and time to repeatedly interact with one another to develop personal relationships or a group

identity may contribute to the instability of these consumer groups. Thus, relying primarily on

group-related factors that apply to groups in online communities/social networking websites, such as

sense of belonging and group identity, may not be effective enough to help GBWs retain their

consumers. It is thus important for GBWs to develop relationships with individual consumers.

Additionally, consumers who participate in online group-buying activities tend to seek positive

Accepted Manuscript

9

is completed. This study focuses on consumer-initiated group-buying transactions.

The online group-buying mechanism is different from that of the traditional quantity discounts for

two main reasons [15, 58, 78]. One is that in a traditional quantity discount situation the seller sets its

own optimal discount quantity and price, while in a group-buying context the price is determined

based on the total quantity of the product/service that all the participating buyers want to buy. The

other is related to the special dynamics of the online group-buying model. In a traditional quantity

discount situation, individual buyers place their own orders based on the information provided by the

seller. However, in a group-buying context in which price is dynamic and uncertain (depending on the

collective bargaining power of the buyer group at the deadline of the group-buying activity), one

buyer’s order would affect the other buyers’ benefits from their participation of the group-buying

activity. Therefore, on many occasions potential buyers may not participate in an online group-buying

activity unless they see evidence that other buyers are participating enthusiastically, and that the

quantity discount threshold they desire is highly likely to be reached.

Online group-buying behaviors are also different from those of group bargaining or negotiations.

For example, negotiations among groups of companies tend to involve multifaceted issues, and thus

different negotiation strategies and decision rules may be applied based on the situations [8].

Additionally, individual members of a group may join the group for diverse motivations,and thus

integrative agreements that can maximize the joint benefits of the individual members in a group may

be mostly elusive [8]. Moreover, consumer groups that are formed on group-buying websites are

relatively unstable compared to traditional social or consumer cooperatives [63]. Consumers’ lack of

access and time to repeatedly interact with one another to develop personal relationships or a group

identity may contribute to the instability of these consumer groups. Thus, relying primarily on

group-related factors that apply to groups in online communities/social networking websites, such as

sense of belonging and group identity, may not be effective enough to help GBWs retain their

consumers. It is thus important for GBWs to develop relationships with individual consumers.

Additionally, consumers who participate in online group-buying activities tend to seek positive

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Page 10 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

10

relationships with sellers, intermediary websites, and other consumers to reduce the uncertainties and

risks associated with online group-buying activities [58].

The social psychology literature suggests that frequent, favorable interpersonal interactions help

to reduce uncertainty and increase trust in others in a social context, and thus promote the emergence

of groups (i.e., social structures) [114]. Additionally, research finds that reciprocal exchanges tend to

enable and increase trust in others members of a group, and thus result in strong ties/relational bonds

among group members [85]. Different forms and levels of uncertainty may exist in different exchange

conditions, and thus may lead to different relationships and social structures among stakeholders in

the exchanges [64]. The arguments above indicate the need to specifically examine the effects of the

relationships among stakeholders in an online group-buying context on the use of the GBWs.In

summary, online group-buying is considered a unique online transaction method that deserves to be

investigated in its own right with regard to key success factors.

Most of the existing empirical studies of user behaviors of GBWs take a multi-perspective

approach for conceptualizing and explaining the use of GBWs, as summarized in Appendix A.

Despite the contributions of these previous studies, most of them do not investigate the users’

intention to use GBWs by simultaneously adoptions the technical, transactional, and relational

perspectives, except for the works of Lang et al. [68] and Yeh et al. [116]. However, the contribution

of those two studies are limited, because they neither incorporate the key factors of the three indicated

conceptual perspectives (e.g., system-related quality factors, satisfaction, and relationship

commitment) nor provide a reasonable nomological structure for explaining the interactions and

relationships between the key technical, transactional, and relational factors that they adopt for

comprehending GBW users’ intentions. Additionally, although some of these prior studies adopt the

incorporate some relational factors for investigating the use of GBWs, they are inadequate to offer

nuanced insights into users’ stickiness intention with GBWs from a relational perspective for two

reasons. One is that while some of those studies highlight the importance of investigating the use of

GBWs from a relational perspective, they primarily focus on how the relationships among members

Accepted Manuscript

10

relationships with sellers, intermediary websites, and other consumers to reduce the uncertainties and

risks associated with online group-buying activities [58].

The social psychology literature suggests that frequent, favorable interpersonal interactions help

to reduce uncertainty and increase trust in others in a social context, and thus promote the emergence

of groups (i.e., social structures) [114]. Additionally, research finds that reciprocal exchanges tend to

enable and increase trust in others members of a group, and thus result in strong ties/relational bonds

among group members [85]. Different forms and levels of uncertainty may exist in different exchange

conditions, and thus may lead to different relationships and social structures among stakeholders in

the exchanges [64]. The arguments above indicate the need to specifically examine the effects of the

relationships among stakeholders in an online group-buying context on the use of the GBWs.In

summary, online group-buying is considered a unique online transaction method that deserves to be

investigated in its own right with regard to key success factors.

Most of the existing empirical studies of user behaviors of GBWs take a multi-perspective

approach for conceptualizing and explaining the use of GBWs, as summarized in Appendix A.

Despite the contributions of these previous studies, most of them do not investigate the users’

intention to use GBWs by simultaneously adoptions the technical, transactional, and relational

perspectives, except for the works of Lang et al. [68] and Yeh et al. [116]. However, the contribution

of those two studies are limited, because they neither incorporate the key factors of the three indicated

conceptual perspectives (e.g., system-related quality factors, satisfaction, and relationship

commitment) nor provide a reasonable nomological structure for explaining the interactions and

relationships between the key technical, transactional, and relational factors that they adopt for

comprehending GBW users’ intentions. Additionally, although some of these prior studies adopt the

incorporate some relational factors for investigating the use of GBWs, they are inadequate to offer

nuanced insights into users’ stickiness intention with GBWs from a relational perspective for two

reasons. One is that while some of those studies highlight the importance of investigating the use of

GBWs from a relational perspective, they primarily focus on how the relationships among members

Page 11 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

11

of the buyers’ groups may influence their behaviors regarding the use of GBWs. The influence of the

relationships between online consumers and GBWs on the consumers’ intentions regarding the use of

GBWs remains an under-researched topic. The other is that research indicates that relationship

commitment and trust are vital for differentiating relational exchanges from pure economic exchanges,

and are thus considered to be critical factors for determining pro-relationship behaviors and

motivations [72, 86]. While a number of previous studies have leveraged the relational view to

investigate consumers’ adoption/post-adoption behavior with respect to GBWs, they comprehend the

building and development of such relationships as the consequence of interpersonal trust and various

forms of social influences. The important role of relationship commitment is unfortunately

overlooked, resulting in a conceptual gap in the current understanding of why online consumers stick

with a GBW given the fact that the use of GBWs are not as indispensable to today’s online users as

other types of websites, such as online portals [119].

2.2 E-commerce success model

DeLone and McLean’s [26, 27, 28] original and updated Information Systems Success models

(D&M ISS models) are among the most widely used for evaluating the degree of IS success because

of their comprehensiveness. The original D&M ISS model includes six dimensions: system quality,

information quality, user satisfaction, system use, individual impact, and organizational impact [26].

To meet the needs of academic assessments of IS success in response to changes in the role of such

systems, DeLone and McLean [27] proposed an updated D&M ISS model. This updated model

differs from the original in three ways: it adds a new dimension of service quality to the original

dimensions of system quality and information quality to more comprehensively evaluate the overall

quality of information systems; it includes the dimension of intention to use as an alternative to

system use in the contexts of non-mandatory system use (i.e. e-commerce); and it groups all the

impact measures (i.e., individual and organizational impacts) into a single impact/benefit dimension

called net benefit.

Accepted Manuscript

11

of the buyers’ groups may influence their behaviors regarding the use of GBWs. The influence of the

relationships between online consumers and GBWs on the consumers’ intentions regarding the use of

GBWs remains an under-researched topic. The other is that research indicates that relationship

commitment and trust are vital for differentiating relational exchanges from pure economic exchanges,

and are thus considered to be critical factors for determining pro-relationship behaviors and

motivations [72, 86]. While a number of previous studies have leveraged the relational view to

investigate consumers’ adoption/post-adoption behavior with respect to GBWs, they comprehend the

building and development of such relationships as the consequence of interpersonal trust and various

forms of social influences. The important role of relationship commitment is unfortunately

overlooked, resulting in a conceptual gap in the current understanding of why online consumers stick

with a GBW given the fact that the use of GBWs are not as indispensable to today’s online users as

other types of websites, such as online portals [119].

2.2 E-commerce success model

DeLone and McLean’s [26, 27, 28] original and updated Information Systems Success models

(D&M ISS models) are among the most widely used for evaluating the degree of IS success because

of their comprehensiveness. The original D&M ISS model includes six dimensions: system quality,

information quality, user satisfaction, system use, individual impact, and organizational impact [26].

To meet the needs of academic assessments of IS success in response to changes in the role of such

systems, DeLone and McLean [27] proposed an updated D&M ISS model. This updated model

differs from the original in three ways: it adds a new dimension of service quality to the original

dimensions of system quality and information quality to more comprehensively evaluate the overall

quality of information systems; it includes the dimension of intention to use as an alternative to

system use in the contexts of non-mandatory system use (i.e. e-commerce); and it groups all the

impact measures (i.e., individual and organizational impacts) into a single impact/benefit dimension

called net benefit.

Page 12 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

12

However, the literature has also noted the challenges and difficulties in using the D&M ISS

model. For example, in addition to providing information to customers, e-commerce systems are

expected to serve transactional purposes, including transaction processing and the provision of online

pre- and post-sales service [105]. Consequently, it is important to consider critical transactional

factors, such as customer satisfaction, fairness, perceived benefits/sacrifices, and loyalty-related

factors, when measuring the success of e-commerce systems. Additionally, it may be necessary to

respecify the relationships among the quality measures in the D&M ISS model and the additional

factors adopted to measure the success of e-commerce systems with reference to specific research

contexts [76, 117].

Wang [109] identifies three major defects of the primary versions of the D&M ISS model. First, the

construct of net benefit in the revised D&M ISS model [27] is too general and is difficult to define. In

the traditional marketing literature, perceived value is conceptualized as involving a consumer’s

evaluation of the ratio of the perceived gain (benefit) and perceived sacrifice (cost) of a transaction,

and is thus considered to be a key strategic construct for explaining repeat purchases, brand loyalty,

and relationship commitment [92]. Wang [109] argues that perceived value reflects a wide range of

costs and benefits of the use of an e-commerce system, and is a key net-benefit variable for

explaining the effects of online customers’ first-hand experiences with e-commerce systems on their

perceptions, such as the level of satisfaction, and on other e-commerce system success measures (e.g.,

loyalty-related constructs) in post-use situations, as done in existing e-commerce studies [4, 20, 77].

The second defect is that DeLone and McLean’s [27] did not attempt to reconcile their updated D&M

ISS model with the perspective of system use behaviors adopted in other IS studies, such as Davis et

al.’s [25] Technology Acceptance Model and Seddon’s [99] reformulation of the original D&M ISS

model, to deepen the theoretical perspective [109]. The last defect is that the nomological structure of

the updated D&M ISS model does not fully comply with the classic quality-value-satisfaction-loyalty

paradigm in the traditional marketing and consumer behavior literature [6, 23, 41, 91, 92].

Consequently, to eliminate those defects, Wang [109] proposes an e-commerce success model

Accepted Manuscript

12

However, the literature has also noted the challenges and difficulties in using the D&M ISS

model. For example, in addition to providing information to customers, e-commerce systems are

expected to serve transactional purposes, including transaction processing and the provision of online

pre- and post-sales service [105]. Consequently, it is important to consider critical transactional

factors, such as customer satisfaction, fairness, perceived benefits/sacrifices, and loyalty-related

factors, when measuring the success of e-commerce systems. Additionally, it may be necessary to

respecify the relationships among the quality measures in the D&M ISS model and the additional

factors adopted to measure the success of e-commerce systems with reference to specific research

contexts [76, 117].

Wang [109] identifies three major defects of the primary versions of the D&M ISS model. First, the

construct of net benefit in the revised D&M ISS model [27] is too general and is difficult to define. In

the traditional marketing literature, perceived value is conceptualized as involving a consumer’s

evaluation of the ratio of the perceived gain (benefit) and perceived sacrifice (cost) of a transaction,

and is thus considered to be a key strategic construct for explaining repeat purchases, brand loyalty,

and relationship commitment [92]. Wang [109] argues that perceived value reflects a wide range of

costs and benefits of the use of an e-commerce system, and is a key net-benefit variable for

explaining the effects of online customers’ first-hand experiences with e-commerce systems on their

perceptions, such as the level of satisfaction, and on other e-commerce system success measures (e.g.,

loyalty-related constructs) in post-use situations, as done in existing e-commerce studies [4, 20, 77].

The second defect is that DeLone and McLean’s [27] did not attempt to reconcile their updated D&M

ISS model with the perspective of system use behaviors adopted in other IS studies, such as Davis et

al.’s [25] Technology Acceptance Model and Seddon’s [99] reformulation of the original D&M ISS

model, to deepen the theoretical perspective [109]. The last defect is that the nomological structure of

the updated D&M ISS model does not fully comply with the classic quality-value-satisfaction-loyalty

paradigm in the traditional marketing and consumer behavior literature [6, 23, 41, 91, 92].

Consequently, to eliminate those defects, Wang [109] proposes an e-commerce success model

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Page 13 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

13

based on the appraisal/beliefs emotional response/attitudes coping responses/behaviors framework

[6, 70]. System quality, information quality, service quality, and perceived value represent beliefs,

customer satisfaction refers to attitudes, and intention to reuse is a behavioral measure. The unique

merit of this model is its integration of the technical (system quality factors) and the transactional

(perceived value and customer satisfaction) views into a single model that can provide researchers

with a comprehensive theoretical basis for investigating e-commerce system success.

2.3 Commitment-trust theory

Consumers who have a positive relationship with an online vendor tend to develop a perception

of high switching costs, which may lead to the formation of long-term commitment and loyalty to the

online vendor [2, 16, 103].In contrast to the transactional view, which focuses on the short-term

provision of tangible and/or intangible benefits to attract and satisfy customers, the relational view

emphasizes the development of long-term relationships between online vendors/intermediaries and

consumers [72]. Thus, this view provides a better explanation of customer retention and loyalty.

The commitment-trust theory [86] focuses on explaining the development of long-term

relationship between exchanges parties [72]. This central premise of this theory is the simultaneous

adoption of relationship commitment and trust as inseparable criticalfactors for the forming and

maintaining business relationships between exchange parties. This theory also considers relationship

commitment and trust as the key mediators between five antecedent variables (relationship

termination costs, relationship benefits, shared values, communication, and opportunistic behavior)

and five outcome variables (acquiescence, propensity to leave, cooperation, functional conflict, and

decision-making uncertainty) for relationship development. This theory proposes that trust directly

influences relationship commitment because trust between two parties helps to reduce the

vulnerability that the parties perceive when they commit to an exchange relationship.

Trust is fundamental in e-commerce environments and has a number of commonalities [10]. First,

trust differs at different individual/group levels. Thus, trust cannot be applied across individual or

Accepted Manuscript

13

based on the appraisal/beliefs emotional response/attitudes coping responses/behaviors framework

[6, 70]. System quality, information quality, service quality, and perceived value represent beliefs,

customer satisfaction refers to attitudes, and intention to reuse is a behavioral measure. The unique

merit of this model is its integration of the technical (system quality factors) and the transactional

(perceived value and customer satisfaction) views into a single model that can provide researchers

with a comprehensive theoretical basis for investigating e-commerce system success.

2.3 Commitment-trust theory

Consumers who have a positive relationship with an online vendor tend to develop a perception

of high switching costs, which may lead to the formation of long-term commitment and loyalty to the

online vendor [2, 16, 103].In contrast to the transactional view, which focuses on the short-term

provision of tangible and/or intangible benefits to attract and satisfy customers, the relational view

emphasizes the development of long-term relationships between online vendors/intermediaries and

consumers [72]. Thus, this view provides a better explanation of customer retention and loyalty.

The commitment-trust theory [86] focuses on explaining the development of long-term

relationship between exchanges parties [72]. This central premise of this theory is the simultaneous

adoption of relationship commitment and trust as inseparable criticalfactors for the forming and

maintaining business relationships between exchange parties. This theory also considers relationship

commitment and trust as the key mediators between five antecedent variables (relationship

termination costs, relationship benefits, shared values, communication, and opportunistic behavior)

and five outcome variables (acquiescence, propensity to leave, cooperation, functional conflict, and

decision-making uncertainty) for relationship development. This theory proposes that trust directly

influences relationship commitment because trust between two parties helps to reduce the

vulnerability that the parties perceive when they commit to an exchange relationship.

Trust is fundamental in e-commerce environments and has a number of commonalities [10]. First,

trust differs at different individual/group levels. Thus, trust cannot be applied across individual or

Page 14 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

14

group settings. Second, researchers can view trust as a domain-specific psychological state that is

influenced by exogenous social factors in a given context, and that is relatively stable and insensitive

to situational stimuli. Finally, trust is clearly different from, but antecedent to, behavior.

With reference to the characteristics of e-commerce consumers’ actions, McKnight and Chervany

[84] propose an interdisciplinary typology of trust that includes four concepts: disposition to trust,

institution-based trust, trusting beliefs, and trusting intention. Disposition to trust refers to one’s trust

in general others, and institutional-based trust means one’s trust is context-specific, and that one feels

trust irrespective of the specific individuals in that context. This indicates that both disposition to trust

and institutional-based trust are not entity-specific. However, trusting beliefs and intentions are

individual-specific and cross-situational, which means that one trusts a specific individual/entity

across various situations/contexts [84]. Correspondingly, disposition to trust and institutional-based

trust are better treated as antecedents of trusting beliefs and intentions, and thus indirectly affect

trust-related behaviors via trusting beliefs and intentions [35]. This discussion implies that the

concept of trusting beliefs is more suitable for this study, because it helps researchers appropriately

investigate how online consumers’ trust in a specific website/online vendor influences their

interactions with the website/vendor across different e-commerce situations/contexts. We thus treat

trust as an aggregation of multiple dimensions of trusting beliefs [10, 29].The adoption of this

perspective of trusting beliefs enables researchers to understand the role of trust in e-commerce

settings from a more holistic view by referring to both cognitive and affective components of trust [10,

36].

Based on the above discussion, we thus identified trust as a second-order formative construct

measured by the three first-order sub-constructs of ability, benevolence, and integrity [10, 37, 80, 84].

First, a trustor’s belief in the ability of a trustee tends to be based on two primary forms of beliefs,

which are whether the trustee is competent at performing the tasks that need to be done, and whether

the trustee has access to knowledge required to perform the intended tasks, and thus is

domain-specific [10]. Consequently, e-commerce consumers’ trust in the ability of a specific website

Accepted Manuscript

14

group settings. Second, researchers can view trust as a domain-specific psychological state that is

influenced by exogenous social factors in a given context, and that is relatively stable and insensitive

to situational stimuli. Finally, trust is clearly different from, but antecedent to, behavior.

With reference to the characteristics of e-commerce consumers’ actions, McKnight and Chervany

[84] propose an interdisciplinary typology of trust that includes four concepts: disposition to trust,

institution-based trust, trusting beliefs, and trusting intention. Disposition to trust refers to one’s trust

in general others, and institutional-based trust means one’s trust is context-specific, and that one feels

trust irrespective of the specific individuals in that context. This indicates that both disposition to trust

and institutional-based trust are not entity-specific. However, trusting beliefs and intentions are

individual-specific and cross-situational, which means that one trusts a specific individual/entity

across various situations/contexts [84]. Correspondingly, disposition to trust and institutional-based

trust are better treated as antecedents of trusting beliefs and intentions, and thus indirectly affect

trust-related behaviors via trusting beliefs and intentions [35]. This discussion implies that the

concept of trusting beliefs is more suitable for this study, because it helps researchers appropriately

investigate how online consumers’ trust in a specific website/online vendor influences their

interactions with the website/vendor across different e-commerce situations/contexts. We thus treat

trust as an aggregation of multiple dimensions of trusting beliefs [10, 29].The adoption of this

perspective of trusting beliefs enables researchers to understand the role of trust in e-commerce

settings from a more holistic view by referring to both cognitive and affective components of trust [10,

36].

Based on the above discussion, we thus identified trust as a second-order formative construct

measured by the three first-order sub-constructs of ability, benevolence, and integrity [10, 37, 80, 84].

First, a trustor’s belief in the ability of a trustee tends to be based on two primary forms of beliefs,

which are whether the trustee is competent at performing the tasks that need to be done, and whether

the trustee has access to knowledge required to perform the intended tasks, and thus is

domain-specific [10]. Consequently, e-commerce consumers’ trust in the ability of a specific website

Page 15 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

15

can be viewed as the consumers’ belief in the website’s competence to provide its customers with

goods and transaction-related services in an appropriate and satisfactory manner [84].

Additionally, a trustor’s belief in a trustee’s benevolence means that the trustor believes that the

trustee actually cares about the trustor and will not do any intentional harm to the trustor, beyond the

trustee’s own benefit motives [37]. Benevolence thus embeds the elements of faith and altruism in a

trusting relationship, which reduces uncertainty and the perceived threats of the others’ opportunistic

behaviors [10]. Consequently, e-commerce consumers’ trust in the benevolence of a specific website

indicates that the consumers believe that this website will act in its customers’ best interests, not just

its own, when conducting a transaction [88].

Finally, a trustor’s belief in the integrity of a trustee means that the trustor believes that the trustee

will always follow a set of appropriate, accepted rules of conduct [36]. Focusing on a trustor’s belief

in a trustee’s domain ability is insufficient to understand the nature of trust-building between the two

parties, and thus researchers must take into considerations how much the trustor is confident that the

trustee will perform the intended behavior with integrity [10]. Consequently, e-commerce consumers’

trust in an online vendor’s integrity means that they believe the online vendor will fulfill its promises

and ethical obligations regarding a transaction by adhering to accepted rules.

Relationship commitment is one entity’s belief that its ongoing relationship with another entity is

important and beneficial, and thus that it is worth making a significant effort to ensure the

continuance of this relationship indefinitely [86]. Relationship commitment, as the outcome of

long-term satisfactory interactions between two exchange parties, would lead one party to assume that

no other exchange partners would provide similar benefits to those of its current exchange party, and

the partner would be less likely to shift to alternative exchange parties [31]. The concept of

relationship commitment has its root in the social psychology studies that primarily discuss the

development of interpersonal relationships/bonds, and how they influence the social power of an

individual in a relationship [82]. Commitment is critical to distinguishing social from economic

exchange theories, because the latter assumes that entities in a social exchange network make

Accepted Manuscript

15

can be viewed as the consumers’ belief in the website’s competence to provide its customers with

goods and transaction-related services in an appropriate and satisfactory manner [84].

Additionally, a trustor’s belief in a trustee’s benevolence means that the trustor believes that the

trustee actually cares about the trustor and will not do any intentional harm to the trustor, beyond the

trustee’s own benefit motives [37]. Benevolence thus embeds the elements of faith and altruism in a

trusting relationship, which reduces uncertainty and the perceived threats of the others’ opportunistic

behaviors [10]. Consequently, e-commerce consumers’ trust in the benevolence of a specific website

indicates that the consumers believe that this website will act in its customers’ best interests, not just

its own, when conducting a transaction [88].

Finally, a trustor’s belief in the integrity of a trustee means that the trustor believes that the trustee

will always follow a set of appropriate, accepted rules of conduct [36]. Focusing on a trustor’s belief

in a trustee’s domain ability is insufficient to understand the nature of trust-building between the two

parties, and thus researchers must take into considerations how much the trustor is confident that the

trustee will perform the intended behavior with integrity [10]. Consequently, e-commerce consumers’

trust in an online vendor’s integrity means that they believe the online vendor will fulfill its promises

and ethical obligations regarding a transaction by adhering to accepted rules.

Relationship commitment is one entity’s belief that its ongoing relationship with another entity is

important and beneficial, and thus that it is worth making a significant effort to ensure the

continuance of this relationship indefinitely [86]. Relationship commitment, as the outcome of

long-term satisfactory interactions between two exchange parties, would lead one party to assume that

no other exchange partners would provide similar benefits to those of its current exchange party, and

the partner would be less likely to shift to alternative exchange parties [31]. The concept of

relationship commitment has its root in the social psychology studies that primarily discuss the

development of interpersonal relationships/bonds, and how they influence the social power of an

individual in a relationship [82]. Commitment is critical to distinguishing social from economic

exchange theories, because the latter assumes that entities in a social exchange network make

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Page 16 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

16

exchange decisions based primarily on rationality and do not develop longitudinal commitments to

one another [21]. Additionally, commitment is part of the endogenous process in a social exchange

network, because frequent exchanges increase individual entities’ knowledge of the others, resulting

in less uncertainty and trust in the others, thus leading to the formation of commitment between

exchanges parties [69]. Consequently, commitment and trust are key factors that shape the behavioral

patterns of exchanges between entities [64, 114].

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1 The integrated research model for examining group-buying website success

The construct of use/intention to use is a worthwhile alternative IS success measure in some

contexts in which system use is mostly voluntary [27, 28]. However, it may be difficult to

operationalize this construct, because it may represent different meanings, including a proxy of the

net benefit from system use, future system use, and an event in a process leading to an individual or

organizational impact, and may thus not an appropriate measure of system success [99]. However, the

construct of intention to reuse reflects online consumers’ intentions of future use, which is similar to

the construct of customer loyalty, and is thus a more appropriate system success/net benefit measure

in e-commerce contexts [109]. Previous marketing and e-commerce studies tend to conceptualize

loyalty, as an outcome variable, from two primary aspects: behavioral and attitudinal/psychological

loyalty [11, 90]. Behavioral loyalty refers to repeated purchases/repatronage, while attitudinal loyalty

refers to the degree of dispositional preference toward an entity [11]. Prior studies tend to measure

behavioral loyalty using factors including repurchase intentions and customers’ share of spending

with a brand/seller, and attitudinal/psychological loyalty using factors including preference and

voluntary positive word-of-mouth [11, 90]. Behavioral loyalty is a state that includes a consumer’s

deeply held commitment to repurchase, which is likely to be converted to readiness to act and then

later lead to actual repurchases [89].

Accepted Manuscript

16

exchange decisions based primarily on rationality and do not develop longitudinal commitments to

one another [21]. Additionally, commitment is part of the endogenous process in a social exchange

network, because frequent exchanges increase individual entities’ knowledge of the others, resulting

in less uncertainty and trust in the others, thus leading to the formation of commitment between

exchanges parties [69]. Consequently, commitment and trust are key factors that shape the behavioral

patterns of exchanges between entities [64, 114].

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1 The integrated research model for examining group-buying website success

The construct of use/intention to use is a worthwhile alternative IS success measure in some

contexts in which system use is mostly voluntary [27, 28]. However, it may be difficult to

operationalize this construct, because it may represent different meanings, including a proxy of the

net benefit from system use, future system use, and an event in a process leading to an individual or

organizational impact, and may thus not an appropriate measure of system success [99]. However, the

construct of intention to reuse reflects online consumers’ intentions of future use, which is similar to

the construct of customer loyalty, and is thus a more appropriate system success/net benefit measure

in e-commerce contexts [109]. Previous marketing and e-commerce studies tend to conceptualize

loyalty, as an outcome variable, from two primary aspects: behavioral and attitudinal/psychological

loyalty [11, 90]. Behavioral loyalty refers to repeated purchases/repatronage, while attitudinal loyalty

refers to the degree of dispositional preference toward an entity [11]. Prior studies tend to measure

behavioral loyalty using factors including repurchase intentions and customers’ share of spending

with a brand/seller, and attitudinal/psychological loyalty using factors including preference and

voluntary positive word-of-mouth [11, 90]. Behavioral loyalty is a state that includes a consumer’s

deeply held commitment to repurchase, which is likely to be converted to readiness to act and then

later lead to actual repurchases [89].

Page 17 of 57

Accepted Manuscript

17

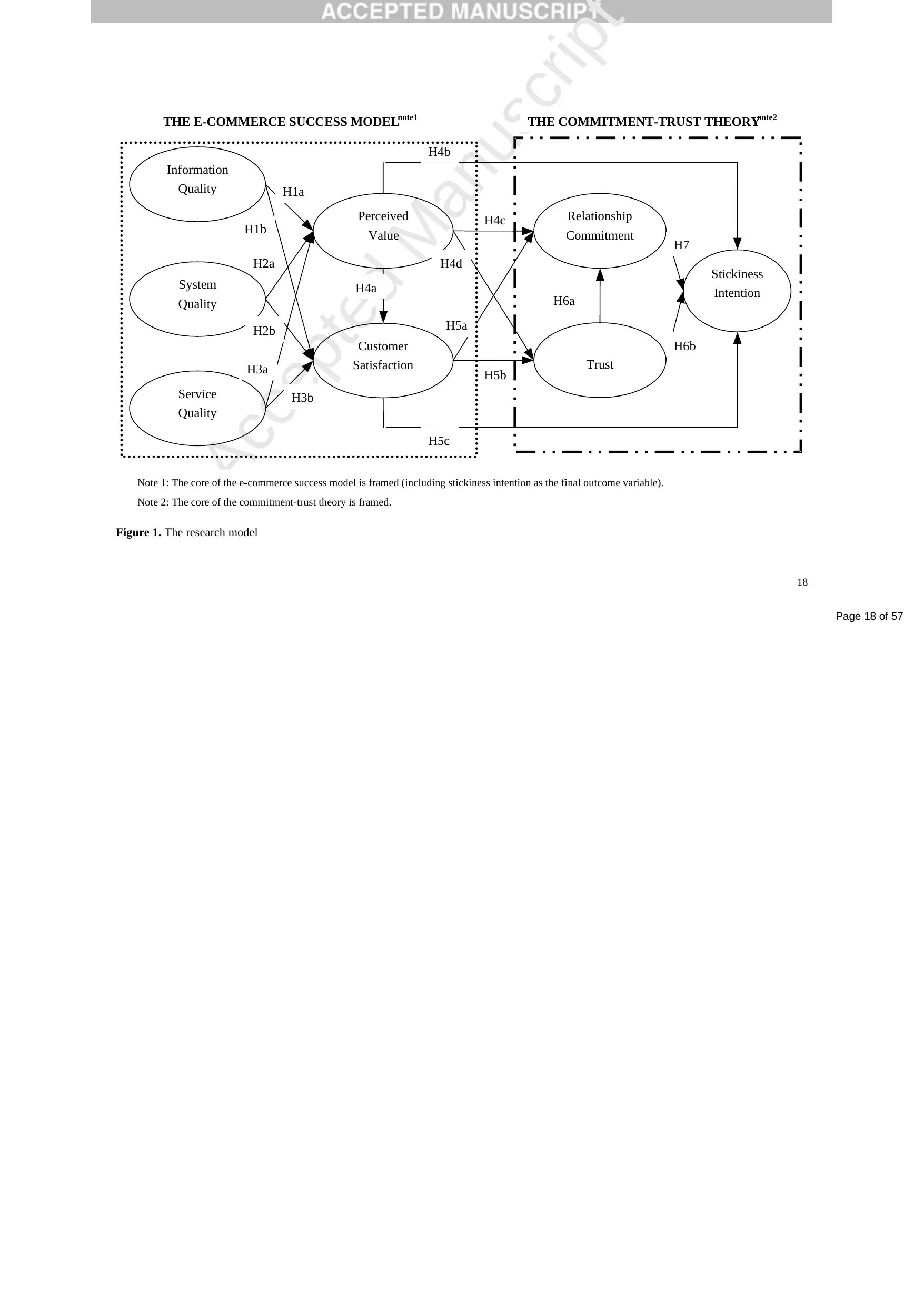

Based on our previous discussion of loyalty, we use stickiness intentions as the surrogate for

behavioral loyalty to an online GBW, and define this construct from the user’s side as repeated visits

to and use of a preferred website because of a deeply held commitment to continuously using it. We

thus consider stickiness intentions to be the users’ intentions to make the use of a website part of their

normal activities or an embedded routine when they consider their participation in online

group-buying activities [72]. Additionally, user commitment has been increasing recognized as a key

predictor of volitional and continued use of organizational systems/IT applications in general and

web-based online services among IS researchers [119]. The definition of stickiness intention enables

us to develop our research model (see Table 1 and Figure 1) based on commitment-trust theory [86]

and the e-commerce success model [109], because it serves as a bridge that connects the relational

view with the technical and transactional views in the context of website use .

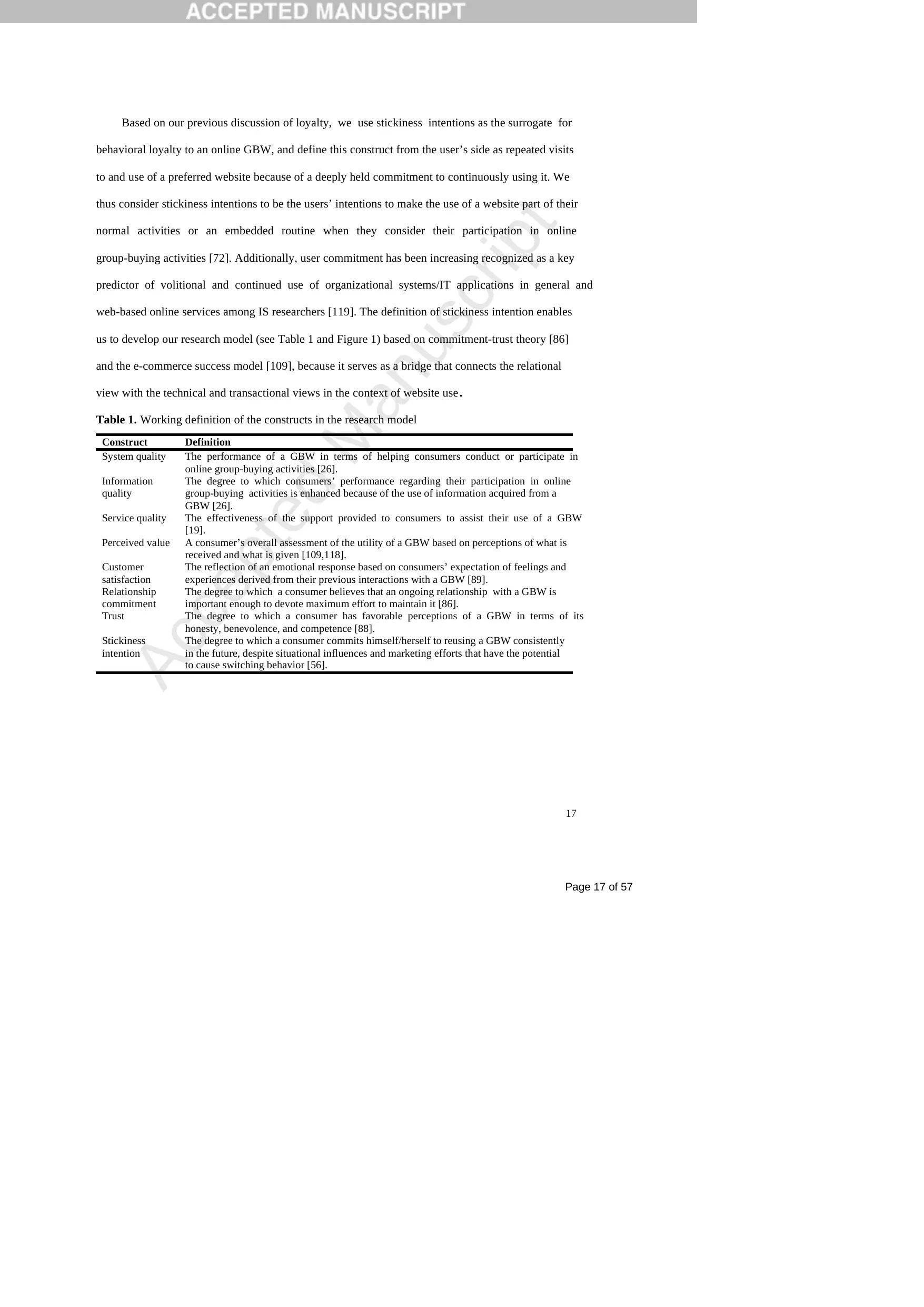

Table 1. Working definition of the constructs in the research model

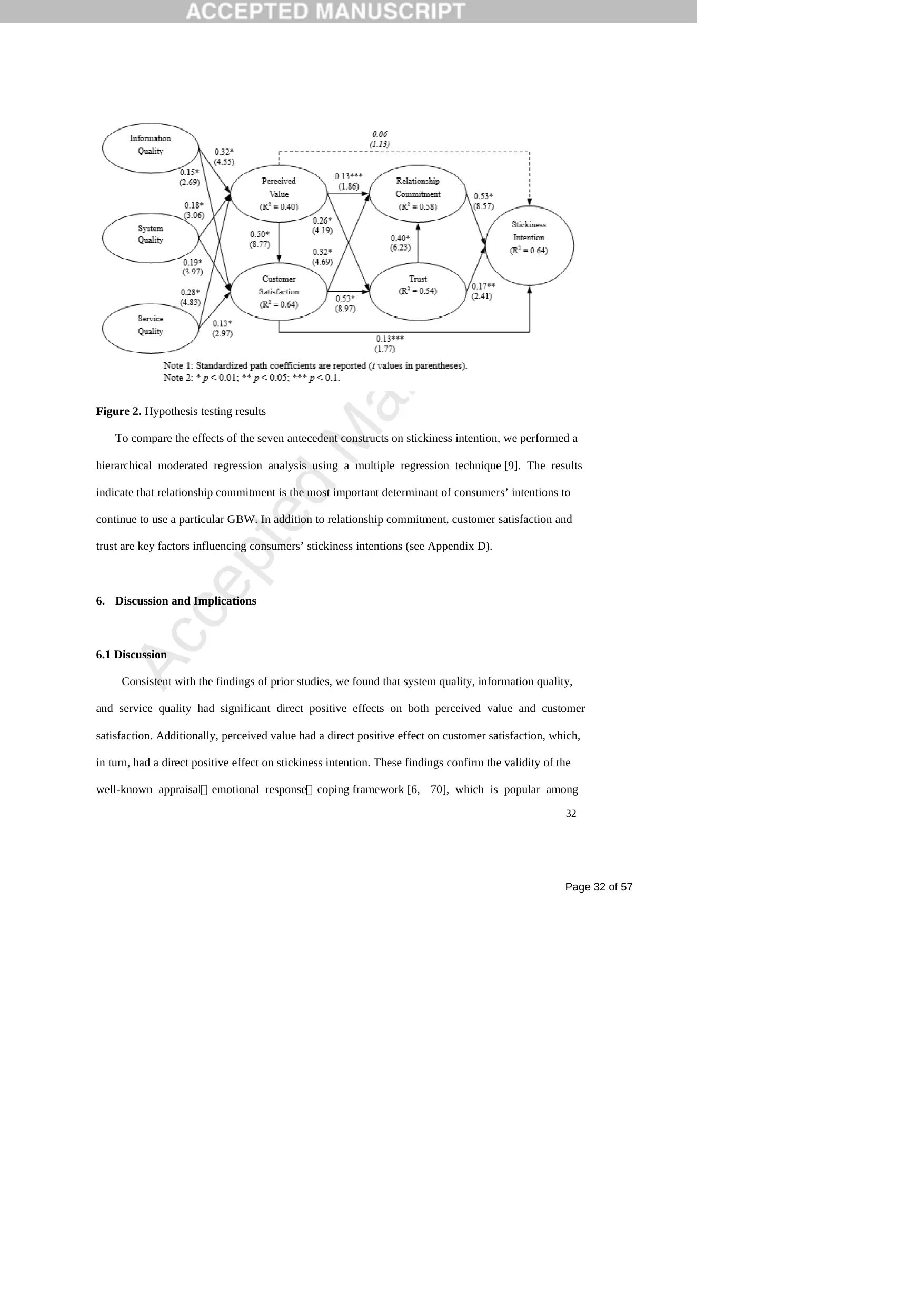

Construct Definition