Attribution Theory in Organizational Sciences: A Meta-Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/03

|19

|15768

|206

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a meta-analysis of attribution theory in the organizational sciences, examining its predictive power on workplace outcomes. The study, published in The Academy of Management Perspectives, analyzes existing research to determine the significance of attributions in shaping employee behavior, leadership, and motivation. The authors focus on attributional dimensions like locus of causality, stability, and controllability, linking them to various organizational phenomena. The research highlights the underutilization of attribution theory in organizational studies compared to social psychology and aims to address the debate on its efficacy. Findings suggest that attributions have consistent effect sizes, comparable to other predictor variables, emphasizing their importance in understanding and managing organizational outcomes. The report concludes with suggestions for expanding attributional research to optimize its contribution to organizational sciences, emphasizing the need for further exploration of its role in various contexts.

S Y M P O S I U M

ATTRIBUTION THEORY IN THE ORGANIZATIONAL

SCIENCES: THE ROAD TRAVELED AND THE PATH AHEAD

PAUL HARVEY

University of New Hampshire

KRISTEN MADISON

Mississippi State University

MARK MARTINKO

University of Queensland

T. RUSSELL CROOK

TAMARA A. CROOK

University of Tennessee

Individuals make attributions when they infer causes aboutparticular outcomes.

Several narrative reviews of attributional research have concluded that attributions

matter in the workplace,but note that attribution theory has been underutilized in

organizational research. To examine the predictive power of attributions in organiza-

tional contexts, we present a meta-analysis of existing attribution theory research. Our

findings suggest that attributions have consistently demonstrated effect sizes that are

comparable to more commonly utilized predictor variables of workplace outcomes.

Expanding on these findings,we argue that attributions are an integral part of indi-

viduals’ cognitive processes that are associated with critical organizational outcomes.

We conclude with suggestions to help expand and optimize the contribution of attri-

butional research to understanding and managing organizational outcomes.

In his seminal work on attribution theory, Heider

(1958)characterized people as naive psychologists

with an innate interest in understanding the causes of

successesand failures. Causal explanations,as

Heider asserted, enable individuals to make sense of

their world and control their environments.Re-

searching how people think about causation helps us

to better understand how and why people engage in

both productive and counterproductiveorganiza-

tional behaviors (Luthans & Church, 2002). For exam-

ple, attributionalprocesses can help explain what

causes an employee’s aggression (e.g., Douglas & Mar-

tinko, 2001; Spector, 2011), an applicant’s interview

success (e.g., Ashkanasy, 1989; Silvester, Anderson-

Gough, Anderson, & Mohamed, 2002), a leader’s be-

havior (e.g., Campbell & Swift, 2006; Green & Liden,

1980),and many otherorganizationalphenomena

(see Martinko, Douglas, & Harvey, 2006, for a review).

The topic of attributions emerged with Heider’s

(1958) work and evolved to become a dominant the-

ory in social psychology in subsequent decades, par-

ticularly after the works of Kelley (1967, 1971, 1973)

and Weiner (1985, 1986, 1995, 2004). The breadth of

phenomena to which attribution theory can be ap-

plied, including learned helplessness, depression, re-

ward/punishmentdecisions, and motivation, has

driven its widespread adoption by social psycholo-

gists (Reisenzein & Rudolph, 2008). By contrast, it has

been asserted that attribution theory has been unde-

rutilized and underappreciated in the organizational

sciences (Martinko, Harvey, & Dasborough, 2011).

We thank the entire editorial team for their help and

guidance throughout the process.We also thank the re-

viewers for the developmentalnature of their reviews

and the help they offered.

娀 The Academy of Management Perspectives

2014, Vol. 28, No. 2, 128–146.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0175

128

Copyright of the Academy of Management, all rights reserved. Contents may not be copied, emailed, posted to a listserv, or otherwise transmitted without the copyright holder’s ex

written permission. Users may print, download, or email articles for individual use only.

ATTRIBUTION THEORY IN THE ORGANIZATIONAL

SCIENCES: THE ROAD TRAVELED AND THE PATH AHEAD

PAUL HARVEY

University of New Hampshire

KRISTEN MADISON

Mississippi State University

MARK MARTINKO

University of Queensland

T. RUSSELL CROOK

TAMARA A. CROOK

University of Tennessee

Individuals make attributions when they infer causes aboutparticular outcomes.

Several narrative reviews of attributional research have concluded that attributions

matter in the workplace,but note that attribution theory has been underutilized in

organizational research. To examine the predictive power of attributions in organiza-

tional contexts, we present a meta-analysis of existing attribution theory research. Our

findings suggest that attributions have consistently demonstrated effect sizes that are

comparable to more commonly utilized predictor variables of workplace outcomes.

Expanding on these findings,we argue that attributions are an integral part of indi-

viduals’ cognitive processes that are associated with critical organizational outcomes.

We conclude with suggestions to help expand and optimize the contribution of attri-

butional research to understanding and managing organizational outcomes.

In his seminal work on attribution theory, Heider

(1958)characterized people as naive psychologists

with an innate interest in understanding the causes of

successesand failures. Causal explanations,as

Heider asserted, enable individuals to make sense of

their world and control their environments.Re-

searching how people think about causation helps us

to better understand how and why people engage in

both productive and counterproductiveorganiza-

tional behaviors (Luthans & Church, 2002). For exam-

ple, attributionalprocesses can help explain what

causes an employee’s aggression (e.g., Douglas & Mar-

tinko, 2001; Spector, 2011), an applicant’s interview

success (e.g., Ashkanasy, 1989; Silvester, Anderson-

Gough, Anderson, & Mohamed, 2002), a leader’s be-

havior (e.g., Campbell & Swift, 2006; Green & Liden,

1980),and many otherorganizationalphenomena

(see Martinko, Douglas, & Harvey, 2006, for a review).

The topic of attributions emerged with Heider’s

(1958) work and evolved to become a dominant the-

ory in social psychology in subsequent decades, par-

ticularly after the works of Kelley (1967, 1971, 1973)

and Weiner (1985, 1986, 1995, 2004). The breadth of

phenomena to which attribution theory can be ap-

plied, including learned helplessness, depression, re-

ward/punishmentdecisions, and motivation, has

driven its widespread adoption by social psycholo-

gists (Reisenzein & Rudolph, 2008). By contrast, it has

been asserted that attribution theory has been unde-

rutilized and underappreciated in the organizational

sciences (Martinko, Harvey, & Dasborough, 2011).

We thank the entire editorial team for their help and

guidance throughout the process.We also thank the re-

viewers for the developmentalnature of their reviews

and the help they offered.

娀 The Academy of Management Perspectives

2014, Vol. 28, No. 2, 128–146.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0175

128

Copyright of the Academy of Management, all rights reserved. Contents may not be copied, emailed, posted to a listserv, or otherwise transmitted without the copyright holder’s ex

written permission. Users may print, download, or email articles for individual use only.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

In support of this argument,Martinko and col-

leagues (2011) compared the two fields and found

nearly six times as many attributional articles pub-

lished in psychology journals as in management

journals.Additionally, as of this writing,a search

of Google Scholar shows more than 7,000 citations

of Kelley’s and Weiner’s works, but only 9% of

those are found in business-related disciplines.

Even accounting for the difference in the number of

journals between the two fields,the magnitude of

this disconnect is surprising,especially consider-

ing the similarity in interpersonal phenomena

studied in both fields.

The recognition of a disconnect between the use

of attribution theory in the organizational sciences

versus the social psychology literature is not new.

As far back as 1995,Martinko (p. 11) commented

that in an examination of organizational behavior

texts “attribution theory as a theoreticalbody of

work was frequently ignored.” Nevertheless,after

viewing the body of research thathad been con-

ducted in the organizational sciences, Weiner

(1995,p. 5) was optimistic with regard to the po-

tential of attribution theory and commented that

“putting attribution theory in the context of organ-

izational behavior should be of great benefit.”

To make the potentialcontributions of attribu-

tion theory to the organizational sciences more sa-

lient, two comprehensive conceptual reviews were

conducted.A review by Martinko and colleagues

(2006) provided an overview of research in

industrial/organizationalpsychology.The review

concluded that the research “unequivocally docu-

ments thatattributions play a significantrole in

behaviors associated with the topics that are central

to [industrial/organizationalpsychology]such as

individual differences,counterproductive behav-

ior, leader/member interactions,impression man-

agement, conflict resolution, training, selection in-

terviewing, and performance appraisal” (p. 174). A

second review by Martinko,Harvey, and Douglas

(2007) arrived at a similar conclusion based on an

examination of attributional studies in the realm of

leadership research. Given this conclusion, the au-

thors noted that they were puzzled as to why attri-

bution theory had not emerged as a major theory of

workplace outcomes.

Both reviews attributed this gap in theory at least

in part to earlier criticisms of attribution theory by

Mitchell (1982) and Lord (1995).Mitchell argued

that attributions accounted for only a small propor-

tion of the variance in causal explanations. In short,

he asserted that attributions might matter, but prob-

ably not very much.Lord (1995) asserted that the

rational information-processing modelsuggested

by attribution theory was unrealistic and that peo-

ple generally rely on more efficient cognitive schema

and implicit assumptions when forming causal per-

ceptions. Martinko and colleagues (2006) countered

these criticisms, asserting that they had been overgen-

eralized and misinterpreted by subsequent research-

ers. Indeed, it has long been recognized that routine

or unimportantoutcomes are less likely to invoke

detailed causal search processes than events that are

unexpected and personally relevant (e.g., Lord, 1995;

Weiner, 1986).

More recent process models,such as that pro-

posed by Douglas, Kiewitz, Martinko, Harvey, Kim,

and Chun (2008), suggest that the degree of cogni-

tive elaboration devoted to attributional analyses of

outcomes varies depending on the nature ofthe

trigger event as well as individual difference factors

(e.g., need for cognition). Thus, empirical studies of

attributions,including those analyzed here,typi-

cally consider attributions in response to trigger

events that are of sufficient personal relevance to

invoke attributional searches. Although it is some-

what speculative to suggest that the underutiliza-

tion of attribution theory in the organizational sci-

ences as compared to social psychology has been

driven primarily by these critiques and their sub-

sequent interpretations by other scholars,it is no-

table thatthe use of attributionalperspectives in

organizational research appeared to taper off after

their publication.

Given the debate about whether attributions mat-

ter, and whether attribution theory has been unde-

rutilized in the organizationalsciences,there are

lingering questions about the efficacy of attribution

theory. Our objective in this study, therefore, is to

shed light on this debate by exploring whether and

to what extent attributions are related to important

workplace outcomes.We do so through a meta-

analysis.Meta-analysis allows researchers to esti-

mate the size of relationships found in a body of

research (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004). If relationships

exist, meta-analysis furnishes an estimate ofthe

magnitudes (i.e.,effectsizes) while ensuring that

the estimates account for important study artifacts

such as sampling and measurement error (Hunter &

Schmidt, 2004).

Applying meta-analysis to key attribution–work-

place outcome relationships appears to be an ap-

propriate and timely way to inform the debate re-

garding the utility and contribution of attribution

theory to understanding the causes and conse-

2014 129Harvey, Madison, Martinko, Russell Crook, and Crook

leagues (2011) compared the two fields and found

nearly six times as many attributional articles pub-

lished in psychology journals as in management

journals.Additionally, as of this writing,a search

of Google Scholar shows more than 7,000 citations

of Kelley’s and Weiner’s works, but only 9% of

those are found in business-related disciplines.

Even accounting for the difference in the number of

journals between the two fields,the magnitude of

this disconnect is surprising,especially consider-

ing the similarity in interpersonal phenomena

studied in both fields.

The recognition of a disconnect between the use

of attribution theory in the organizational sciences

versus the social psychology literature is not new.

As far back as 1995,Martinko (p. 11) commented

that in an examination of organizational behavior

texts “attribution theory as a theoreticalbody of

work was frequently ignored.” Nevertheless,after

viewing the body of research thathad been con-

ducted in the organizational sciences, Weiner

(1995,p. 5) was optimistic with regard to the po-

tential of attribution theory and commented that

“putting attribution theory in the context of organ-

izational behavior should be of great benefit.”

To make the potentialcontributions of attribu-

tion theory to the organizational sciences more sa-

lient, two comprehensive conceptual reviews were

conducted.A review by Martinko and colleagues

(2006) provided an overview of research in

industrial/organizationalpsychology.The review

concluded that the research “unequivocally docu-

ments thatattributions play a significantrole in

behaviors associated with the topics that are central

to [industrial/organizationalpsychology]such as

individual differences,counterproductive behav-

ior, leader/member interactions,impression man-

agement, conflict resolution, training, selection in-

terviewing, and performance appraisal” (p. 174). A

second review by Martinko,Harvey, and Douglas

(2007) arrived at a similar conclusion based on an

examination of attributional studies in the realm of

leadership research. Given this conclusion, the au-

thors noted that they were puzzled as to why attri-

bution theory had not emerged as a major theory of

workplace outcomes.

Both reviews attributed this gap in theory at least

in part to earlier criticisms of attribution theory by

Mitchell (1982) and Lord (1995).Mitchell argued

that attributions accounted for only a small propor-

tion of the variance in causal explanations. In short,

he asserted that attributions might matter, but prob-

ably not very much.Lord (1995) asserted that the

rational information-processing modelsuggested

by attribution theory was unrealistic and that peo-

ple generally rely on more efficient cognitive schema

and implicit assumptions when forming causal per-

ceptions. Martinko and colleagues (2006) countered

these criticisms, asserting that they had been overgen-

eralized and misinterpreted by subsequent research-

ers. Indeed, it has long been recognized that routine

or unimportantoutcomes are less likely to invoke

detailed causal search processes than events that are

unexpected and personally relevant (e.g., Lord, 1995;

Weiner, 1986).

More recent process models,such as that pro-

posed by Douglas, Kiewitz, Martinko, Harvey, Kim,

and Chun (2008), suggest that the degree of cogni-

tive elaboration devoted to attributional analyses of

outcomes varies depending on the nature ofthe

trigger event as well as individual difference factors

(e.g., need for cognition). Thus, empirical studies of

attributions,including those analyzed here,typi-

cally consider attributions in response to trigger

events that are of sufficient personal relevance to

invoke attributional searches. Although it is some-

what speculative to suggest that the underutiliza-

tion of attribution theory in the organizational sci-

ences as compared to social psychology has been

driven primarily by these critiques and their sub-

sequent interpretations by other scholars,it is no-

table thatthe use of attributionalperspectives in

organizational research appeared to taper off after

their publication.

Given the debate about whether attributions mat-

ter, and whether attribution theory has been unde-

rutilized in the organizationalsciences,there are

lingering questions about the efficacy of attribution

theory. Our objective in this study, therefore, is to

shed light on this debate by exploring whether and

to what extent attributions are related to important

workplace outcomes.We do so through a meta-

analysis.Meta-analysis allows researchers to esti-

mate the size of relationships found in a body of

research (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004). If relationships

exist, meta-analysis furnishes an estimate ofthe

magnitudes (i.e.,effectsizes) while ensuring that

the estimates account for important study artifacts

such as sampling and measurement error (Hunter &

Schmidt, 2004).

Applying meta-analysis to key attribution–work-

place outcome relationships appears to be an ap-

propriate and timely way to inform the debate re-

garding the utility and contribution of attribution

theory to understanding the causes and conse-

2014 129Harvey, Madison, Martinko, Russell Crook, and Crook

quences of organizational behaviors. Thus, a goal of

our meta-analytic assessmentof key attributional

relationships is to estimate not only whether attri-

butions matter,but also the extent to which they

matter. Appendix A reports the papers included in

our analyses;Appendix B describes our method-

ological approach in more detail.

If we find that attribution processes do not mat-

ter, we can conclude that researchers have rightly

ignored the role of attributions in the workplace.

However, if we find that attributions do matter, and

matter substantially (i.e.,have strong effects),we

can conclude that researchers have erred in ignor-

ing the role of attributions in the workplace and

hopefully describe new contexts and research ar-

eas—such as macro-level inquiry—that present

new terrain for the theory.

ATTRIBUTIONAL DIMENSIONS AND

WORKPLACE OUTCOMES

Before discussing our meta-analysis, we first re-

view the attributional dimensions that are linked to

workplace outcomes. As Weiner (1986) explained,

attributions generally vary along severalunderly-

ing dimensions. Although several dimensions have

been identified,our search of the extant literature

suggested thatwithin the organizationalsciences

the most commonly studied are the locus of cau-

sality, stability, and controllability dimensions

identified by Weiner (1985).We therefore focus

on studies of these dimensions in the present

meta-analysis.

Locus of Causality

The most commonly studied attributional di-

mension by far is locus of causality, which refers to

whether the perceived cause of an outcome is in-

ternal or external. In the case of attributions made

for one’s own outcomes (i.e.,self-attributions),an

internal attribution occurs when the cause is per-

ceived to reflect some characteristic of the person

such as effort or ability. For example, an employee

who misses a deadline and believes that this out-

come is due to his or her own lack of effort or

ability is making an internal attribution. An exter-

nal attribution for the same outcome might take the

form of blaming coworkers or a supervisor for the

missed deadline. Similarly, when observing others’

outcomes (i.e., social attributions), internal attribu-

tions refer to dispositional or behavioral character-

istics (e.g., effort or ability) of the person being

observed, whereas external attributions refer to sit-

uational factors that are often beyond the observed

individual’s control.

Weiner (1985) observed that the locus dimension

was particularly relevant to the emotional re-

sponses individuals form in response to trigger

events.His widely cited achievementmotivation

model (Weiner, 1985) suggeststhat individuals

form attributions in response to trigger events,

which, as noted above,typically take the form of

outcomes thatare negative,surprising, or unex-

pected (e.g., an unexpectedly poor evaluation).

When personally relevantnegative outcomes are

attributed to internalfactors (e.g.,insufficient ef-

fort), Weiner’s framework indicates that self-fo-

cused emotions such as guilt and shame are likely.

Conversely, when these outcomes are attributed to

external causes (e.g., a biased supervisor), emotions

such as anger and frustration typically follow.

Weiner’s modelalso accommodates positive out-

comes and suggests thatinternal attributions for

these events promote feelings ofpride, whereas

external attributions are associated with gratitude

and other externally focused positive emotions.

Understanding the relationship between attribu-

tions and emotions is important because it is the

affective response to attributions thatis thought

to shape behavioral reactions to trigger events

(Weiner, 1985).For example,research has shown

that the locus of an attribution for negative work-

place outcomes can influence the choice between

passive and aggressive behavioral responses (e.g.,

Douglas & Martinko, 2001).

The locus dimension is also relevant to leader–

member relationships and interactions. Conceptual

and empirical studies indicate that when supervi-

sors and employees conflict in their attributions for

negative outcomes,interpersonalconflict and di-

minished evaluations of relationship quality occur

(e.g., Ashkanasy, 1989, 1995; Green & Mitchell,

1979; Martinko, Moss, Douglas, & Borkowski, 2007).

This effect is particularly likely when the attribu-

tional conflict leads each party to blame the other for

negative outcomes orwhen each claims personal

credit for desirable outcomes.

The locus of an attribution can also influence

reward and punishmentdecisions. As one might

expect, there is evidence that employees are more

likely to be rewarded for high levels of performance

when the supervisor attributes the performance to

internal characteristics,such as the employees’

ability, rather than to external factors (Johnson,

Erez, Kiker, & Motowidlo, 2002). Similarly, punish-

130 MayThe Academy of Management Perspectives

our meta-analytic assessmentof key attributional

relationships is to estimate not only whether attri-

butions matter,but also the extent to which they

matter. Appendix A reports the papers included in

our analyses;Appendix B describes our method-

ological approach in more detail.

If we find that attribution processes do not mat-

ter, we can conclude that researchers have rightly

ignored the role of attributions in the workplace.

However, if we find that attributions do matter, and

matter substantially (i.e.,have strong effects),we

can conclude that researchers have erred in ignor-

ing the role of attributions in the workplace and

hopefully describe new contexts and research ar-

eas—such as macro-level inquiry—that present

new terrain for the theory.

ATTRIBUTIONAL DIMENSIONS AND

WORKPLACE OUTCOMES

Before discussing our meta-analysis, we first re-

view the attributional dimensions that are linked to

workplace outcomes. As Weiner (1986) explained,

attributions generally vary along severalunderly-

ing dimensions. Although several dimensions have

been identified,our search of the extant literature

suggested thatwithin the organizationalsciences

the most commonly studied are the locus of cau-

sality, stability, and controllability dimensions

identified by Weiner (1985).We therefore focus

on studies of these dimensions in the present

meta-analysis.

Locus of Causality

The most commonly studied attributional di-

mension by far is locus of causality, which refers to

whether the perceived cause of an outcome is in-

ternal or external. In the case of attributions made

for one’s own outcomes (i.e.,self-attributions),an

internal attribution occurs when the cause is per-

ceived to reflect some characteristic of the person

such as effort or ability. For example, an employee

who misses a deadline and believes that this out-

come is due to his or her own lack of effort or

ability is making an internal attribution. An exter-

nal attribution for the same outcome might take the

form of blaming coworkers or a supervisor for the

missed deadline. Similarly, when observing others’

outcomes (i.e., social attributions), internal attribu-

tions refer to dispositional or behavioral character-

istics (e.g., effort or ability) of the person being

observed, whereas external attributions refer to sit-

uational factors that are often beyond the observed

individual’s control.

Weiner (1985) observed that the locus dimension

was particularly relevant to the emotional re-

sponses individuals form in response to trigger

events.His widely cited achievementmotivation

model (Weiner, 1985) suggeststhat individuals

form attributions in response to trigger events,

which, as noted above,typically take the form of

outcomes thatare negative,surprising, or unex-

pected (e.g., an unexpectedly poor evaluation).

When personally relevantnegative outcomes are

attributed to internalfactors (e.g.,insufficient ef-

fort), Weiner’s framework indicates that self-fo-

cused emotions such as guilt and shame are likely.

Conversely, when these outcomes are attributed to

external causes (e.g., a biased supervisor), emotions

such as anger and frustration typically follow.

Weiner’s modelalso accommodates positive out-

comes and suggests thatinternal attributions for

these events promote feelings ofpride, whereas

external attributions are associated with gratitude

and other externally focused positive emotions.

Understanding the relationship between attribu-

tions and emotions is important because it is the

affective response to attributions thatis thought

to shape behavioral reactions to trigger events

(Weiner, 1985).For example,research has shown

that the locus of an attribution for negative work-

place outcomes can influence the choice between

passive and aggressive behavioral responses (e.g.,

Douglas & Martinko, 2001).

The locus dimension is also relevant to leader–

member relationships and interactions. Conceptual

and empirical studies indicate that when supervi-

sors and employees conflict in their attributions for

negative outcomes,interpersonalconflict and di-

minished evaluations of relationship quality occur

(e.g., Ashkanasy, 1989, 1995; Green & Mitchell,

1979; Martinko, Moss, Douglas, & Borkowski, 2007).

This effect is particularly likely when the attribu-

tional conflict leads each party to blame the other for

negative outcomes orwhen each claims personal

credit for desirable outcomes.

The locus of an attribution can also influence

reward and punishmentdecisions. As one might

expect, there is evidence that employees are more

likely to be rewarded for high levels of performance

when the supervisor attributes the performance to

internal characteristics,such as the employees’

ability, rather than to external factors (Johnson,

Erez, Kiker, & Motowidlo, 2002). Similarly, punish-

130 MayThe Academy of Management Perspectives

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ments are more likely when undesirable outcomes

are attributed to internal employee characteristics

or behaviors,such as insufficient effort (Wood &

Mitchell, 1981).

Stability

The stability dimension of attributions refers to

the perceived variability or permanence of a causal

factor. To illustrate, a person’s intelligence is typi-

cally viewed as a relatively stable factor,whereas

effort level is more variable (Weiner, Frieze, Kukla,

Reed, Rest, & Rosenbaum,1971).Unlike locus of

causality, the stability dimension is rarely studied

separately from other dimensions. More com-

monly, researchers examine the locus and stability

dimensions in tandem. This design is logical in that

the stability of a cause can attenuate or exacerbate

the emotional and behavioral responsesdriven

by the locus of the attribution.More specifically,

perceptions ofcausal stability help shape a per-

son’s expectations for future outcomes,and these

expectations can soften or amplify the emotional

response to a trigger event (Weiner, 1985). For ex-

ample, if an employee attributes a poor evaluation

to a lack of ability (an internal and relatively stable

cause) the individual is likely to experience shame,

given that a lack of ability is likely to cause similar

problems in the future.This shame, in turn, can

promote withdrawal behaviors (Hall, Hladkyi,

Perry, & Ruthig, 2004).If the evaluation is attrib-

uted to insufficient effort (an internal and unstable

cause),the employee is more likely to experience

guilt and a motivation to exert more effort in the

future.

The perceived stability of a cause is also likely to

help shape leader–memberrelationship quality

and reward/punishmentdecisions. As described

above, the negative impact of attributions that tar-

get blame for undesirable outcomes on one’s super-

visor or subordinate is often weaker if the attribu-

tion is unstable rather than stable in nature. This is

because unstable attributions reduce the expecta-

tion that similar outcomes will occur in the future.

This attenuating effect has been shown to reduce

the frequency and severity of punishments for un-

desirable workplace outcomes (Wood & Mitch-

ell, 1981).

Controllability

Of the three attributional dimensions included in

this analysis, controllability has received the small-

est amount of research attention.Controllability

refers to the extent to which an observer perceives

the cause of an outcome to be under someone’s

volition (Weiner, 1985).Factors such as luck and

task difficulty are generally perceived to be uncon-

trollable,whereas effort and,to a much lesser ex-

tent, ability are viewed as controllable factors.

As these examples suggest, there is some overlap

between the controllability dimension and the lo-

cus and stability dimensions.For instance,effort,

which is usually viewed as internal and unstable, is

most often seen as controllable, whereas task diffi-

culty, which is seen as external and stable, is most

often viewed as uncontrollable. As such, controlla-

bility has been linked to a number of the same

affective and leadership outcomes thatthe other

dimensions predict,albeit in a smaller number of

studies. This overlap might explain why controlla-

bility has received less attention than the other two

dimensions. Nonetheless,there was a sufficient

amountof research on controllability as a stand-

alone dimension to warrant inclusion in our

analysis.

A META-ANALYTIC REVIEW OF

ATTRIBUTIONAL RESEARCH IN THE

ORGANIZATIONAL SCIENCES

The reviews and observations discussed atthe

outset of this article argue that attribution theory

has been underutilized by scholars in the organiza-

tional sciences.Although conceptual reviews and

articles have attempted to address these issues, we

believe that a meta-analytic assessment summariz-

ing the predictive power of attributions in organi-

zational research is beneficialin showcasing the

utility of attribution theory.In particular, our as-

sessment is intended to help ease concerns stem-

ming from various interpretationsof Mitchell’s

(1982) aforementioned criticism regarding effect

sizes that may have caused some scholars to ignore

the predictive potential of attribution theory.Ad-

ditionally, a meta-analytic study allows us to pres-

ent an overview of the nomological network of

attribution theory, which can help scholars identify

gaps in the existing empirical literature.

To this end, we meta-analyze relationships be-

tween the attributional dimensions of locus, stabil-

ity, and controllability and four categories of work-

place outcome variables.These include affective

outcomes (e.g., discrete emotions such as anger and

sympathy,attitudes such as job satisfaction,emo-

tional evaluations such as self-esteem),perfor-

2014 131Harvey, Madison, Martinko, Russell Crook, and Crook

are attributed to internal employee characteristics

or behaviors,such as insufficient effort (Wood &

Mitchell, 1981).

Stability

The stability dimension of attributions refers to

the perceived variability or permanence of a causal

factor. To illustrate, a person’s intelligence is typi-

cally viewed as a relatively stable factor,whereas

effort level is more variable (Weiner, Frieze, Kukla,

Reed, Rest, & Rosenbaum,1971).Unlike locus of

causality, the stability dimension is rarely studied

separately from other dimensions. More com-

monly, researchers examine the locus and stability

dimensions in tandem. This design is logical in that

the stability of a cause can attenuate or exacerbate

the emotional and behavioral responsesdriven

by the locus of the attribution.More specifically,

perceptions ofcausal stability help shape a per-

son’s expectations for future outcomes,and these

expectations can soften or amplify the emotional

response to a trigger event (Weiner, 1985). For ex-

ample, if an employee attributes a poor evaluation

to a lack of ability (an internal and relatively stable

cause) the individual is likely to experience shame,

given that a lack of ability is likely to cause similar

problems in the future.This shame, in turn, can

promote withdrawal behaviors (Hall, Hladkyi,

Perry, & Ruthig, 2004).If the evaluation is attrib-

uted to insufficient effort (an internal and unstable

cause),the employee is more likely to experience

guilt and a motivation to exert more effort in the

future.

The perceived stability of a cause is also likely to

help shape leader–memberrelationship quality

and reward/punishmentdecisions. As described

above, the negative impact of attributions that tar-

get blame for undesirable outcomes on one’s super-

visor or subordinate is often weaker if the attribu-

tion is unstable rather than stable in nature. This is

because unstable attributions reduce the expecta-

tion that similar outcomes will occur in the future.

This attenuating effect has been shown to reduce

the frequency and severity of punishments for un-

desirable workplace outcomes (Wood & Mitch-

ell, 1981).

Controllability

Of the three attributional dimensions included in

this analysis, controllability has received the small-

est amount of research attention.Controllability

refers to the extent to which an observer perceives

the cause of an outcome to be under someone’s

volition (Weiner, 1985).Factors such as luck and

task difficulty are generally perceived to be uncon-

trollable,whereas effort and,to a much lesser ex-

tent, ability are viewed as controllable factors.

As these examples suggest, there is some overlap

between the controllability dimension and the lo-

cus and stability dimensions.For instance,effort,

which is usually viewed as internal and unstable, is

most often seen as controllable, whereas task diffi-

culty, which is seen as external and stable, is most

often viewed as uncontrollable. As such, controlla-

bility has been linked to a number of the same

affective and leadership outcomes thatthe other

dimensions predict,albeit in a smaller number of

studies. This overlap might explain why controlla-

bility has received less attention than the other two

dimensions. Nonetheless,there was a sufficient

amountof research on controllability as a stand-

alone dimension to warrant inclusion in our

analysis.

A META-ANALYTIC REVIEW OF

ATTRIBUTIONAL RESEARCH IN THE

ORGANIZATIONAL SCIENCES

The reviews and observations discussed atthe

outset of this article argue that attribution theory

has been underutilized by scholars in the organiza-

tional sciences.Although conceptual reviews and

articles have attempted to address these issues, we

believe that a meta-analytic assessment summariz-

ing the predictive power of attributions in organi-

zational research is beneficialin showcasing the

utility of attribution theory.In particular, our as-

sessment is intended to help ease concerns stem-

ming from various interpretationsof Mitchell’s

(1982) aforementioned criticism regarding effect

sizes that may have caused some scholars to ignore

the predictive potential of attribution theory.Ad-

ditionally, a meta-analytic study allows us to pres-

ent an overview of the nomological network of

attribution theory, which can help scholars identify

gaps in the existing empirical literature.

To this end, we meta-analyze relationships be-

tween the attributional dimensions of locus, stabil-

ity, and controllability and four categories of work-

place outcome variables.These include affective

outcomes (e.g., discrete emotions such as anger and

sympathy,attitudes such as job satisfaction,emo-

tional evaluations such as self-esteem),perfor-

2014 131Harvey, Madison, Martinko, Russell Crook, and Crook

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

mance outcomes (e.g., task performance, effort lev-

els), leader–member relationship quality outcomes

(e.g., leader-memberexchange [LMX]ratings,per-

ceived managerial trustworthiness, conflict between

employees and supervisors), and reward/punishment

decisions (e.g., award allocation decisions, intent to

punish subordinates).As discussed in the previous

section, attributions have been linked to each of these

outcomes in organizational research.Further,these

categories allow a logical categorization of most stud-

ies identified for inclusion in the analysis.Within

each of these outcome categories we examine the

predictive power ofattributions.Although attribu-

tional variables have also been conceptualized as out-

come variables (e.g.,attributions ofresponsibility;

Weiner, 1995), this body of research has not yet ma-

tured to the point where enough studies are available

for a meta-analytic assessment.

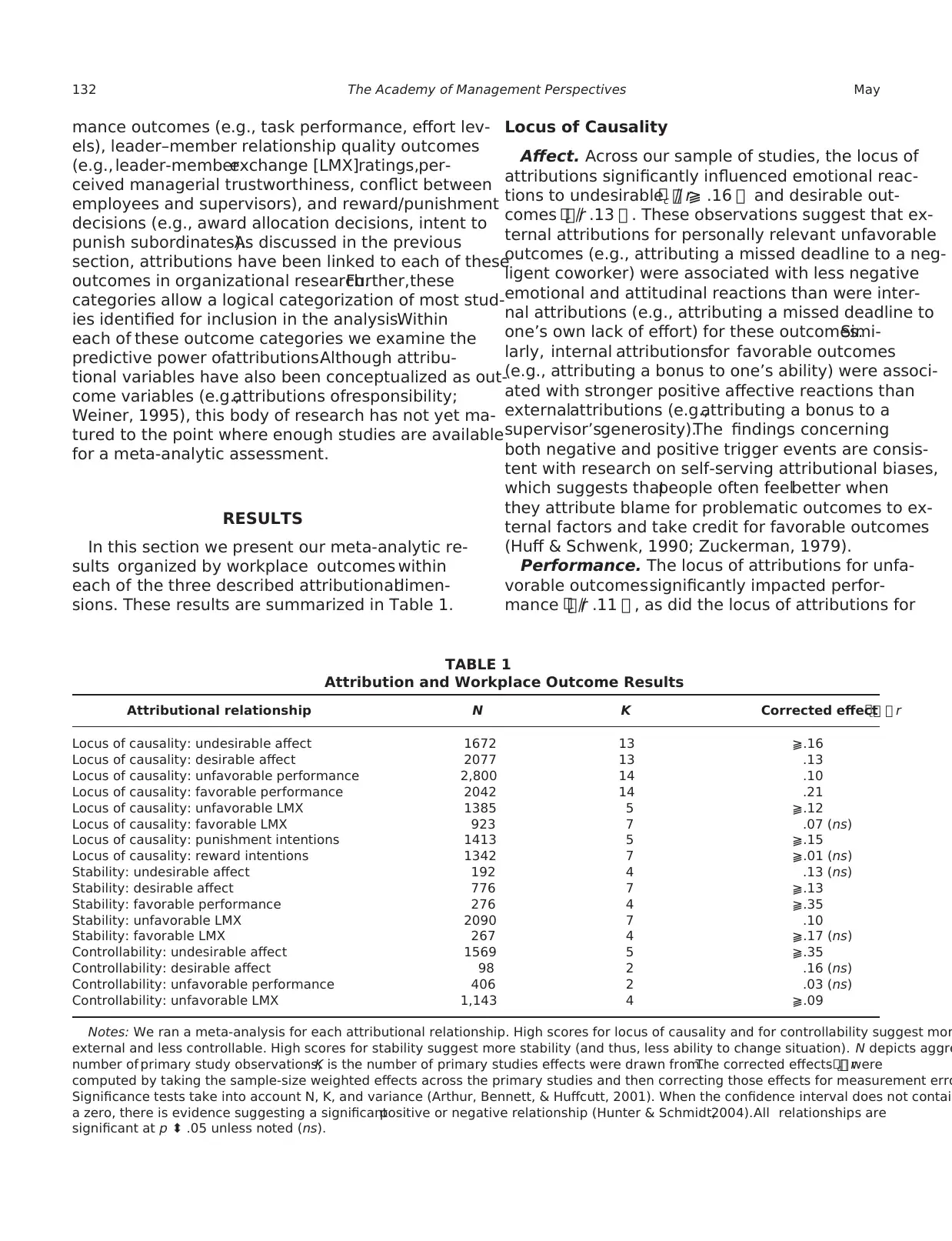

RESULTS

In this section we present our meta-analytic re-

sults organized by workplace outcomes within

each of the three described attributionaldimen-

sions. These results are summarized in Table 1.

Locus of Causality

Affect. Across our sample of studies, the locus of

attributions significantly influenced emotional reac-

tions to undesirable 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .16 娀 and desirable out-

comes 娀 rc ⫽ .13 娀 . These observations suggest that ex-

ternal attributions for personally relevant unfavorable

outcomes (e.g., attributing a missed deadline to a neg-

ligent coworker) were associated with less negative

emotional and attitudinal reactions than were inter-

nal attributions (e.g., attributing a missed deadline to

one’s own lack of effort) for these outcomes.Simi-

larly, internal attributionsfor favorable outcomes

(e.g., attributing a bonus to one’s ability) were associ-

ated with stronger positive affective reactions than

externalattributions (e.g.,attributing a bonus to a

supervisor’sgenerosity).The findings concerning

both negative and positive trigger events are consis-

tent with research on self-serving attributional biases,

which suggests thatpeople often feelbetter when

they attribute blame for problematic outcomes to ex-

ternal factors and take credit for favorable outcomes

(Huff & Schwenk, 1990; Zuckerman, 1979).

Performance. The locus of attributions for unfa-

vorable outcomessignificantly impacted perfor-

mance 娀 rc ⫽ .11 娀 , as did the locus of attributions for

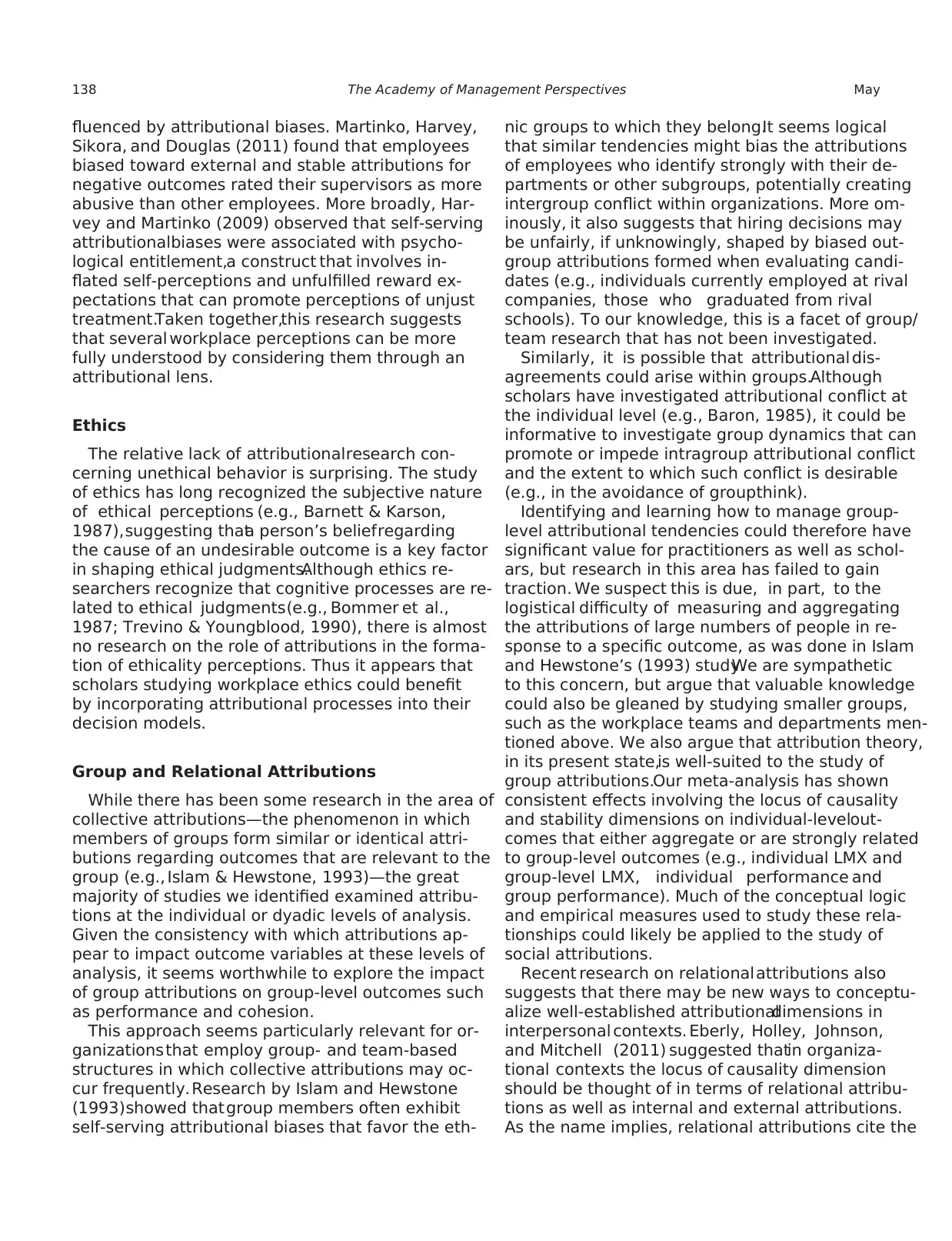

TABLE 1

Attribution and Workplace Outcome Results

Attributional relationship N K Corrected effect 娀 rc娀

Locus of causality: undesirable affect 1672 13 ⫺.16

Locus of causality: desirable affect 2077 13 .13

Locus of causality: unfavorable performance 2,800 14 .10

Locus of causality: favorable performance 2042 14 .21

Locus of causality: unfavorable LMX 1385 5 ⫺.12

Locus of causality: favorable LMX 923 7 .07 (ns)

Locus of causality: punishment intentions 1413 5 ⫺.15

Locus of causality: reward intentions 1342 7 ⫺.01 (ns)

Stability: undesirable affect 192 4 .13 (ns)

Stability: desirable affect 776 7 ⫺.13

Stability: favorable performance 276 4 ⫺.35

Stability: unfavorable LMX 2090 7 .10

Stability: favorable LMX 267 4 ⫺.17 (ns)

Controllability: undesirable affect 1569 5 ⫺.35

Controllability: desirable affect 98 2 .16 (ns)

Controllability: unfavorable performance 406 2 .03 (ns)

Controllability: unfavorable LMX 1,143 4 ⫺.09

Notes: We ran a meta-analysis for each attributional relationship. High scores for locus of causality and for controllability suggest mor

external and less controllable. High scores for stability suggest more stability (and thus, less ability to change situation). N depicts aggre

number of primary study observations;K is the number of primary studies effects were drawn from.The corrected effects 娀 rc娀 were

computed by taking the sample-size weighted effects across the primary studies and then correcting those effects for measurement erro

Significance tests take into account N, K, and variance (Arthur, Bennett, & Huffcutt, 2001). When the confidence interval does not contain

a zero, there is evidence suggesting a significantpositive or negative relationship (Hunter & Schmidt,2004).All relationships are

significant at p ⬍ .05 unless noted (ns).

132 MayThe Academy of Management Perspectives

els), leader–member relationship quality outcomes

(e.g., leader-memberexchange [LMX]ratings,per-

ceived managerial trustworthiness, conflict between

employees and supervisors), and reward/punishment

decisions (e.g., award allocation decisions, intent to

punish subordinates).As discussed in the previous

section, attributions have been linked to each of these

outcomes in organizational research.Further,these

categories allow a logical categorization of most stud-

ies identified for inclusion in the analysis.Within

each of these outcome categories we examine the

predictive power ofattributions.Although attribu-

tional variables have also been conceptualized as out-

come variables (e.g.,attributions ofresponsibility;

Weiner, 1995), this body of research has not yet ma-

tured to the point where enough studies are available

for a meta-analytic assessment.

RESULTS

In this section we present our meta-analytic re-

sults organized by workplace outcomes within

each of the three described attributionaldimen-

sions. These results are summarized in Table 1.

Locus of Causality

Affect. Across our sample of studies, the locus of

attributions significantly influenced emotional reac-

tions to undesirable 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .16 娀 and desirable out-

comes 娀 rc ⫽ .13 娀 . These observations suggest that ex-

ternal attributions for personally relevant unfavorable

outcomes (e.g., attributing a missed deadline to a neg-

ligent coworker) were associated with less negative

emotional and attitudinal reactions than were inter-

nal attributions (e.g., attributing a missed deadline to

one’s own lack of effort) for these outcomes.Simi-

larly, internal attributionsfor favorable outcomes

(e.g., attributing a bonus to one’s ability) were associ-

ated with stronger positive affective reactions than

externalattributions (e.g.,attributing a bonus to a

supervisor’sgenerosity).The findings concerning

both negative and positive trigger events are consis-

tent with research on self-serving attributional biases,

which suggests thatpeople often feelbetter when

they attribute blame for problematic outcomes to ex-

ternal factors and take credit for favorable outcomes

(Huff & Schwenk, 1990; Zuckerman, 1979).

Performance. The locus of attributions for unfa-

vorable outcomessignificantly impacted perfor-

mance 娀 rc ⫽ .11 娀 , as did the locus of attributions for

TABLE 1

Attribution and Workplace Outcome Results

Attributional relationship N K Corrected effect 娀 rc娀

Locus of causality: undesirable affect 1672 13 ⫺.16

Locus of causality: desirable affect 2077 13 .13

Locus of causality: unfavorable performance 2,800 14 .10

Locus of causality: favorable performance 2042 14 .21

Locus of causality: unfavorable LMX 1385 5 ⫺.12

Locus of causality: favorable LMX 923 7 .07 (ns)

Locus of causality: punishment intentions 1413 5 ⫺.15

Locus of causality: reward intentions 1342 7 ⫺.01 (ns)

Stability: undesirable affect 192 4 .13 (ns)

Stability: desirable affect 776 7 ⫺.13

Stability: favorable performance 276 4 ⫺.35

Stability: unfavorable LMX 2090 7 .10

Stability: favorable LMX 267 4 ⫺.17 (ns)

Controllability: undesirable affect 1569 5 ⫺.35

Controllability: desirable affect 98 2 .16 (ns)

Controllability: unfavorable performance 406 2 .03 (ns)

Controllability: unfavorable LMX 1,143 4 ⫺.09

Notes: We ran a meta-analysis for each attributional relationship. High scores for locus of causality and for controllability suggest mor

external and less controllable. High scores for stability suggest more stability (and thus, less ability to change situation). N depicts aggre

number of primary study observations;K is the number of primary studies effects were drawn from.The corrected effects 娀 rc娀 were

computed by taking the sample-size weighted effects across the primary studies and then correcting those effects for measurement erro

Significance tests take into account N, K, and variance (Arthur, Bennett, & Huffcutt, 2001). When the confidence interval does not contain

a zero, there is evidence suggesting a significantpositive or negative relationship (Hunter & Schmidt,2004).All relationships are

significant at p ⬍ .05 unless noted (ns).

132 MayThe Academy of Management Perspectives

favorable outcomes 娀 rc ⫽ .21 娀 .This suggests that

external attributions for personally relevant unfa-

vorable events were associated with increases in

negative self- and leader-reported performance rat-

ings, whereas internal attributions for positive out-

comes were positively related to performance rat-

ings. The latter finding is consistent with research

indicating that internal attributions for desirable

outcomes,such as attributing a job offer to one’s

own abilities and experience,promote self-confi-

dence and efficacy (Silver, Mitchell, & Gist, 1995)—

which, in turn, can lead to improved performance

levels (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Consistent with

this perspective, the .21 corrected r also suggests that

external attributions for desirable outcomes, such as

attributing a job offer to luck,were detrimental (or,

more accurately,less beneficial)to performance.

More peculiar is the finding that the apparent recip-

rocal of this tendency, externalizing rather than inter-

nalizing blame for negative outcomes, was also detri-

mental to performance.

A possible reconciliation of these findings might

be found in Harvey and Martinko’s (2009) argu-

ment that erroneously attributing undesirable out-

comes to external factors could prevent employees

from accurately evaluating and remedying their

performance weaknesses.The observation that in-

dividuals tend to be more objective when forming

attributions for positive outcomes is also relevant

(Huff & Schwenk,1990).Thus, it may be that the

internal attributions for desirable outcomesare

more accurate than the external attributions for un-

desirable events.In this case we would expect

the self-efficacy gains from internalizing positive

events to provide a legitimate source of confidence

that can fuel performance increases,whereas the

self-efficacy protection provided by external attri-

butions for negative events might attenuate motiva-

tion for performance improvements.

Leader–member relationship valuations. Exter-

nal attributions for unfavorable events (e.g.,em-

ployees attributing a poor raise to a biased super-

visor or to economic factors) were associated with a

significant improvementin leader–memberrela-

tionship quality rating 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .12 娀 , indicating a

decrease in negative evaluationsof relationship

quality) across our sample of studies. This is a

somewhat surprising finding, given that the super-

visor is often thought to be a common targetof

employees’external attributions (Harvey & Mar-

tinko, 2009). By contrast, if employees attribute

negative outcomes to externalfactors otherthan

their supervisors (e.g., economic factors), the find-

ing appears more intuitive.This relationship sug-

gests thatthese non-supervisor–targeted external

attributions by subjects may be more common than

we had expected.

Employees’ internal attributions for favorable

events were more strongly associated with im-

provements in leader–member relationship quality

娀 rc ⫽ .07 娀 than were external attributions. Although

we might have expected externalattributions for

these outcomesto improve relationship quality

more strongly than internal attributions if the

leader was the targetof the externalattributions,

the aforementioned findings concerning negative

outcomes again suggestthat employees consider

several other external factors when forming these

attributions.

Reward/punishment decisions. Attributional stud-

ies on reward and punishment decisions generally

look at leaders’ attributions for subordinate perfor-

mance.These attributions differ from the self-fo-

cused attributions studied in the context of affec-

tive responses,performance,and leader–member

relationships in that they are social attributions

that consider observers’(usually leaders’) attribu-

tions for other people’s (usually subordinates’) out-

comes.In these studies,internal attributions refer

to causal factors that are internal to the employee

being observed (e.g., ability, effort), whereas exter-

nal attributions refer to factors outside the employ-

ee’s control (e.g.,task difficulty, bad luck). Corre-

lations from these studies were coded such that

higher scores denote external attributions. Predict-

ably, results suggested that external attributions for

employees’negative outcomes(generally opera-

tionalized as poor performance)were associated

with lower punishment intentions 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .15 娀 . A

significant relationship between locus attributions

for favorable outcomes and reward decisions

was not observed.

Stability

Affect.As noted above, the locus dimension,

rather than the stability dimension, is generally

thought to impact affective outcomes. Not surpris-

ingly then, the results did not indicate that stable

attributions for unfavorable eventswere signifi-

cantly associated with increases ordecreases in

affective outcomes.A significant relationship be-

tween stable attributions for positive events and

affective responses was observed,indicating that

stable attributions were associated with lower lev-

2014 133Harvey, Madison, Martinko, Russell Crook, and Crook

external attributions for personally relevant unfa-

vorable events were associated with increases in

negative self- and leader-reported performance rat-

ings, whereas internal attributions for positive out-

comes were positively related to performance rat-

ings. The latter finding is consistent with research

indicating that internal attributions for desirable

outcomes,such as attributing a job offer to one’s

own abilities and experience,promote self-confi-

dence and efficacy (Silver, Mitchell, & Gist, 1995)—

which, in turn, can lead to improved performance

levels (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Consistent with

this perspective, the .21 corrected r also suggests that

external attributions for desirable outcomes, such as

attributing a job offer to luck,were detrimental (or,

more accurately,less beneficial)to performance.

More peculiar is the finding that the apparent recip-

rocal of this tendency, externalizing rather than inter-

nalizing blame for negative outcomes, was also detri-

mental to performance.

A possible reconciliation of these findings might

be found in Harvey and Martinko’s (2009) argu-

ment that erroneously attributing undesirable out-

comes to external factors could prevent employees

from accurately evaluating and remedying their

performance weaknesses.The observation that in-

dividuals tend to be more objective when forming

attributions for positive outcomes is also relevant

(Huff & Schwenk,1990).Thus, it may be that the

internal attributions for desirable outcomesare

more accurate than the external attributions for un-

desirable events.In this case we would expect

the self-efficacy gains from internalizing positive

events to provide a legitimate source of confidence

that can fuel performance increases,whereas the

self-efficacy protection provided by external attri-

butions for negative events might attenuate motiva-

tion for performance improvements.

Leader–member relationship valuations. Exter-

nal attributions for unfavorable events (e.g.,em-

ployees attributing a poor raise to a biased super-

visor or to economic factors) were associated with a

significant improvementin leader–memberrela-

tionship quality rating 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .12 娀 , indicating a

decrease in negative evaluationsof relationship

quality) across our sample of studies. This is a

somewhat surprising finding, given that the super-

visor is often thought to be a common targetof

employees’external attributions (Harvey & Mar-

tinko, 2009). By contrast, if employees attribute

negative outcomes to externalfactors otherthan

their supervisors (e.g., economic factors), the find-

ing appears more intuitive.This relationship sug-

gests thatthese non-supervisor–targeted external

attributions by subjects may be more common than

we had expected.

Employees’ internal attributions for favorable

events were more strongly associated with im-

provements in leader–member relationship quality

娀 rc ⫽ .07 娀 than were external attributions. Although

we might have expected externalattributions for

these outcomesto improve relationship quality

more strongly than internal attributions if the

leader was the targetof the externalattributions,

the aforementioned findings concerning negative

outcomes again suggestthat employees consider

several other external factors when forming these

attributions.

Reward/punishment decisions. Attributional stud-

ies on reward and punishment decisions generally

look at leaders’ attributions for subordinate perfor-

mance.These attributions differ from the self-fo-

cused attributions studied in the context of affec-

tive responses,performance,and leader–member

relationships in that they are social attributions

that consider observers’(usually leaders’) attribu-

tions for other people’s (usually subordinates’) out-

comes.In these studies,internal attributions refer

to causal factors that are internal to the employee

being observed (e.g., ability, effort), whereas exter-

nal attributions refer to factors outside the employ-

ee’s control (e.g.,task difficulty, bad luck). Corre-

lations from these studies were coded such that

higher scores denote external attributions. Predict-

ably, results suggested that external attributions for

employees’negative outcomes(generally opera-

tionalized as poor performance)were associated

with lower punishment intentions 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .15 娀 . A

significant relationship between locus attributions

for favorable outcomes and reward decisions

was not observed.

Stability

Affect.As noted above, the locus dimension,

rather than the stability dimension, is generally

thought to impact affective outcomes. Not surpris-

ingly then, the results did not indicate that stable

attributions for unfavorable eventswere signifi-

cantly associated with increases ordecreases in

affective outcomes.A significant relationship be-

tween stable attributions for positive events and

affective responses was observed,indicating that

stable attributions were associated with lower lev-

2014 133Harvey, Madison, Martinko, Russell Crook, and Crook

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

els of unfavorable affective reactions than unstable

attributions 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .13 娀 .

Performance.Across the sample of studies,we

observed a significant positive association between

stable attributions for favorable outcomes and per-

formance 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .35; note that the sign is negative

because a high score indicates poor performance).

Only one study in our sample investigated the re-

lationship between stable attributions for undesir-

able outcomes and poor performance, so this cate-

gory was not included in the analysis.

Leader–member relationship evaluations.Our

findings concerning leader–memberrelationship

outcomes and stability indicated that stable attri-

butions for unfavorable events were associated

with an increase in reports of poor relationship

quality 娀 rc ⫽ .10 娀 . This is logical because if a cause

is deemed to be stable, it follows that the employee

views the leader as incapable or unwilling to rem-

edy the situation.The stability of attributions for

favorable outcomes was unrelated to leader–mem-

ber relationship quality.

Reward/punishmentdecisions.An insufficient

number of published studies on the relationship

between stability attributions and reward/punish-

ment decisions were identified to perform a meta-

analysis on this relationship.

Controllability

Affect.The attribution of negative outcomes to

personally controllable causes was associated with

reduced levels of negative emotions and attitudes

娀 rc ⫺⫽ .35 娀 . This is consistent with the notion that

controllable causes can frequently be avoided in

the future and are therefore less likely to provoke

negative affective reactions (Aquino,Douglas, &

Martinko, 2004).Although our sample of observa-

tions for this relationship was small, no significant

association between the controllability dimension

and affective outcomes was observed in the context

of positive trigger events.

Performance.Very few studies have investi-

gated the relationship between controllability attri-

butions and performance. Only two studies in our

sample investigated this relationship,both in the

context of negative trigger events, and did not sug-

gest any significant associations.

Leader–member relationship evaluations.Per-

ceived controllability was associated with a slight

decrease in reports of unfavorable leader–member

relationship quality 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .09 娀 . Not surprisingly,

this suggeststhat leader–memberrelationships

did not suffer when employees perceived that they

personally controlled the causes of an undesirable

outcome. Conversely, the correlation suggests that

a slight worsening of leader–member relationship

quality occurred when the cause was seen as be-

yond the employees’control. Only one study ex-

amined this relationship in the context of desirable

outcomes, so meta-analysis was not possible.

Reward/punishmentdecisions.An insufficient

number of published studies on the relationship

between controllability attributionsand reward/

punishment decisions were identified to perform a

meta-analysis on this relationship.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to provide

an empirical investigation into the importance and

impact of attributions on organizational outcomes.

We begin this section with a brief comparison of

our findings against those of other predictor vari-

ables that are frequently used in organizational re-

search. We then discuss implications of our analy-

sis for the future of attributional research.

Locus of Causality

Across our sample of studies we found that the

most commonly studied attributionaldimension,

locus of causality,consistently showed a signifi-

cant influence on each of the outcome variables

included in the analysis. The average magnitude of

the effects was .14. Aguinis, Gottfredson, and

Wright (2011) asserted that perhaps the best way to

interpret the magnitude of effect sizes is to put

them into the context of other relationships as-

sessed via meta-analysis. Our review suggests that

this predictive power is on par with that shown by

other predictors of similar outcome variables.

As an illustration, we use the job performance

outcome studied here (locus rc ⫽ .16). Cohen-

Charesh and Spector’s (2001) meta-analysis of jus-

tice perceptions indicated average weighted corre-

lation coefficients of .13, .45, and .16 between

distributive, procedural,and interactionaljustice

perceptions, respectively, and work performance in

field studies. In laboratory studies,their analysis

indicated a mean weighted correlation of .05 (non-

significant) between distributive justice percep-

tions and performance and .11 between procedural

justice perceptions and performance. Similarly,

Barrick and Mount (1991) observed corrected cor-

relations of .10, ⫺.04, ⫺.05, .17, and .00 when

134 MayThe Academy of Management Perspectives

attributions 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .13 娀 .

Performance.Across the sample of studies,we

observed a significant positive association between

stable attributions for favorable outcomes and per-

formance 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .35; note that the sign is negative

because a high score indicates poor performance).

Only one study in our sample investigated the re-

lationship between stable attributions for undesir-

able outcomes and poor performance, so this cate-

gory was not included in the analysis.

Leader–member relationship evaluations.Our

findings concerning leader–memberrelationship

outcomes and stability indicated that stable attri-

butions for unfavorable events were associated

with an increase in reports of poor relationship

quality 娀 rc ⫽ .10 娀 . This is logical because if a cause

is deemed to be stable, it follows that the employee

views the leader as incapable or unwilling to rem-

edy the situation.The stability of attributions for

favorable outcomes was unrelated to leader–mem-

ber relationship quality.

Reward/punishmentdecisions.An insufficient

number of published studies on the relationship

between stability attributions and reward/punish-

ment decisions were identified to perform a meta-

analysis on this relationship.

Controllability

Affect.The attribution of negative outcomes to

personally controllable causes was associated with

reduced levels of negative emotions and attitudes

娀 rc ⫺⫽ .35 娀 . This is consistent with the notion that

controllable causes can frequently be avoided in

the future and are therefore less likely to provoke

negative affective reactions (Aquino,Douglas, &

Martinko, 2004).Although our sample of observa-

tions for this relationship was small, no significant

association between the controllability dimension

and affective outcomes was observed in the context

of positive trigger events.

Performance.Very few studies have investi-

gated the relationship between controllability attri-

butions and performance. Only two studies in our

sample investigated this relationship,both in the

context of negative trigger events, and did not sug-

gest any significant associations.

Leader–member relationship evaluations.Per-

ceived controllability was associated with a slight

decrease in reports of unfavorable leader–member

relationship quality 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .09 娀 . Not surprisingly,

this suggeststhat leader–memberrelationships

did not suffer when employees perceived that they

personally controlled the causes of an undesirable

outcome. Conversely, the correlation suggests that

a slight worsening of leader–member relationship

quality occurred when the cause was seen as be-

yond the employees’control. Only one study ex-

amined this relationship in the context of desirable

outcomes, so meta-analysis was not possible.

Reward/punishmentdecisions.An insufficient

number of published studies on the relationship

between controllability attributionsand reward/

punishment decisions were identified to perform a

meta-analysis on this relationship.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to provide

an empirical investigation into the importance and

impact of attributions on organizational outcomes.

We begin this section with a brief comparison of

our findings against those of other predictor vari-

ables that are frequently used in organizational re-

search. We then discuss implications of our analy-

sis for the future of attributional research.

Locus of Causality

Across our sample of studies we found that the

most commonly studied attributionaldimension,

locus of causality,consistently showed a signifi-

cant influence on each of the outcome variables

included in the analysis. The average magnitude of

the effects was .14. Aguinis, Gottfredson, and

Wright (2011) asserted that perhaps the best way to

interpret the magnitude of effect sizes is to put

them into the context of other relationships as-

sessed via meta-analysis. Our review suggests that

this predictive power is on par with that shown by

other predictors of similar outcome variables.

As an illustration, we use the job performance

outcome studied here (locus rc ⫽ .16). Cohen-

Charesh and Spector’s (2001) meta-analysis of jus-

tice perceptions indicated average weighted corre-

lation coefficients of .13, .45, and .16 between

distributive, procedural,and interactionaljustice

perceptions, respectively, and work performance in

field studies. In laboratory studies,their analysis

indicated a mean weighted correlation of .05 (non-

significant) between distributive justice percep-

tions and performance and .11 between procedural

justice perceptions and performance. Similarly,

Barrick and Mount (1991) observed corrected cor-

relations of .10, ⫺.04, ⫺.05, .17, and .00 when

134 MayThe Academy of Management Perspectives

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

examining the impactof Big Five personality di-

mensions of extroversion, emotional stability,

agreeableness,conscientiousness,and openness,

respectively,to experience on performance mea-

sures.In their analysis of the impact of core self-

evaluation components on performance, Judge and

Bono (2001) observed corrected correlations of .26,

.29, .22, and .19 for self-esteem, self-efficacy, locus

of control, and emotional stability, respectively,

and performance. A meta-analysis by Gernster and

Day (1997) showed a corrected correlation coeffi-

cient of .11 between LMX and objective perfor-

mance ratings.

Based on this comparison, the effect sizes of the

locus of causality dimension fall within what ap-

pears to be a range that is acceptable to most schol-

ars, as evidenced by the frequency with which jus-

tice perceptions, core self-evaluation, the Big Five

personality traits, and LMX are studied as predictor

variables in the organizational sciences. A compar-

ison against predictors of the other outcome vari-

ables studied here indicated a similar pattern:

Some predictors show larger effects and some show

smaller effects, but in most cases attributional pre-

dictors demonstrated effectsizes comparable to

those of variables thatare utilized far more fre-

quently than attributionalvariables by organiza-

tional researchers.

Stability

Although the number and scope of studies exam-

ining the impact of the stability dimension were

limited compared to the locus of causality studies,

we observed significant associations between this

dimension and affect, performance,and leader–

member relationship evaluations. The average cor-

rected correlation coefficient of these relationships

was .18. Using the comparisons reported in the

previous section,this effect size again appears to

compare favorably with more frequently studied

predictor variables. It is also worth reiterating that

the locus and stability dimensions are often studied

together,a combination that could explain still

more variance than the two dimensions explain

individually.

Controllability

The relatively small number of studies using the

controllability dimension limited the scope of our

analysis but indicated that it was a relevant predic-

tor of affective outcomes and leader–member eval-

uations.Again, the magnitude of the observed ef-

fects 娀 rc ⫺⫽ .35 and ⫺⫽ .07, respectively) appears

comparable to other predictors thatare far more

commonly used by organizational scholars.

THE PATH AHEAD

The underlying theme of our findings, consistent

with the conclusions of earlier conceptual reviews,

is that attribution theory has significant predictive

power that is similar or equal to other theories that

attempt to predict and explain workplace phenom-

ena. Thus attribution theory adds an important

piece of predictive power to the arsenal of frame-

works and constructs available to organizational

researchers.Nevertheless,it appears thatattribu-

tion theory has been underutilized compared to

other theories,suggesting thatthere is ample op-

portunity for scholars to add to our understanding

of workplace behaviorby using an attributional

perspective.

The four categoriesof outcome variables in-

cluded in our analysis have been reasonably well

examined through an attributional lens,but there

are numerous other avenues for new outcomes to

be explored.In fact, as social psychologists have

observed, causal perceptions arguably influence al-

most every aspectof a person’s behavior.Thus,

there are probably very few workplace behaviors

and outcomes that cannot be investigated from an

attributional perspective. Although space consid-

erations limit our ability to discuss all the poten-

tial areas where attribution theory can be ex-

tended, we will highlight those that appear

particularly promising. These potentialareas in-

clude examining additional attributional dimensions,

expanding attribution theory across new topical ar-

eas,investigating temporal effects,and introducing

attribution theory in the macro domain.

Additional Attributional Dimensions

In the areas of organizational science where at-

tribution theory has been utilized,we observed a

narrow focus on the locus of causality and,to a

lesser extent,the stability and controllability di-

mensions. While our analysis suggests that this fo-

cus is not unwarranted, we also note that there are

other dimensions such as intentionality and global-

ity that likely have additional explanatory power.

While these dimensions have received some empir-

ical attention, the number of studies was too small

to include in our analysis.

2014 135Harvey, Madison, Martinko, Russell Crook, and Crook

mensions of extroversion, emotional stability,

agreeableness,conscientiousness,and openness,

respectively,to experience on performance mea-

sures.In their analysis of the impact of core self-

evaluation components on performance, Judge and