A Comprehensive Report on Australian Renewable Energy Policy

VerifiedAdded on 2020/04/07

|17

|4391

|31

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of Australia's current renewable energy policy landscape. It delves into key policy measures such as the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF), carbon pricing mechanisms (including its repeal), the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC), the Renewable Energy Target (RET), and tariff policies like Feed-in Tariffs (FiTs). The report examines the impact of these policies on the renewable energy industry, considering factors like government interventions, sectoral efficiency, and cost-effective solutions. It highlights the politicization and uncertainty surrounding the policy environment, the government's focus on reducing electricity costs, and the emphasis on market-driven solutions. The analysis also covers the role of ARENA and CEFC, the impact of ERF, and the changes to key policies since 2013. The report concludes with a discussion of the challenges and future implications for the renewable energy sector in Australia.

1

Australian Current Policy on Renewable Energy

Student’s Name:

Professor:

Course + Code:

Date

Australian Current Policy on Renewable Energy

Student’s Name:

Professor:

Course + Code:

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

Table of Contents

1.0 Introduction................................................................................................................................3

2.0 The current Australian renewable energy policy.......................................................................4

2.1 The Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF)..................................................................................7

2.2 Carbon pricing........................................................................................................................9

2.3 The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA)..........................................................9

2.4 The Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC).................................................................10

2.5 The Renewable Energy Target (RET).................................................................................11

2.6 Tariff policies and Feed in Tariffs (FiTs)............................................................................12

3.0 Conclusion...............................................................................................................................13

4.0 References................................................................................................................................15

Table of Contents

1.0 Introduction................................................................................................................................3

2.0 The current Australian renewable energy policy.......................................................................4

2.1 The Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF)..................................................................................7

2.2 Carbon pricing........................................................................................................................9

2.3 The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA)..........................................................9

2.4 The Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC).................................................................10

2.5 The Renewable Energy Target (RET).................................................................................11

2.6 Tariff policies and Feed in Tariffs (FiTs)............................................................................12

3.0 Conclusion...............................................................................................................................13

4.0 References................................................................................................................................15

3

1.0 Introduction

The renewable energy policy plays an increasingly pivotal role as Australia grapples with the

appropriate strategy of climate change as well as increasing penetration in renewables. The

renewable energy policy environment in the recent years has turned out to be highly politicized

and uncertain. The industrial implications are also significant, and the current Australian policy

on renewable energy has been taken through a period of rapid changes. Currently, there is

increasing concern on reduction of various interventions by the government, sectoral efficiency

and having least cost solutions incentivized since the review of the 2013 renewable energy policy

(Buckman & Diesendorf 2010, p.56). The priorities of government and the political parties as

well as polarity in perspectives have been caused by significant policy uncertainty, policy

responses and increased politicization of the climate change. The existing consensus, however,

maintains that there are inefficiencies in the Australian renewables and the energy sector. The

purpose of this paper is to carry out an examination of the key policy measures on renewable

energy as well as their impact on the industry's future.

The single largest sector contribution in Australia is realized from the electric power generation

that produces 33% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions (GHG emissions). From the year

2012 to 2013, fossil fuels approximately provide 87% of Australia's electricity compared to 13%

realized from the renewable sources (Elliston, Diesendorf & MacGill 2012, p. 89). As a result of

reduced demand for electricity in the National Electricity Market (NEM) of Australia and

variations in the generation mix, there has been approximately a 4% decrease in electric power

emissions from 2012-2013 to 2013-2014. Generation of renewable energy is predominantly

hydro though solar and wind has also been on the rise. Various environmental factors have

mostly caused variation in the hydro generation while a slow-down in the deployment of the

renewables has led to the increased production of the black coal generators. The successive

1.0 Introduction

The renewable energy policy plays an increasingly pivotal role as Australia grapples with the

appropriate strategy of climate change as well as increasing penetration in renewables. The

renewable energy policy environment in the recent years has turned out to be highly politicized

and uncertain. The industrial implications are also significant, and the current Australian policy

on renewable energy has been taken through a period of rapid changes. Currently, there is

increasing concern on reduction of various interventions by the government, sectoral efficiency

and having least cost solutions incentivized since the review of the 2013 renewable energy policy

(Buckman & Diesendorf 2010, p.56). The priorities of government and the political parties as

well as polarity in perspectives have been caused by significant policy uncertainty, policy

responses and increased politicization of the climate change. The existing consensus, however,

maintains that there are inefficiencies in the Australian renewables and the energy sector. The

purpose of this paper is to carry out an examination of the key policy measures on renewable

energy as well as their impact on the industry's future.

The single largest sector contribution in Australia is realized from the electric power generation

that produces 33% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions (GHG emissions). From the year

2012 to 2013, fossil fuels approximately provide 87% of Australia's electricity compared to 13%

realized from the renewable sources (Elliston, Diesendorf & MacGill 2012, p. 89). As a result of

reduced demand for electricity in the National Electricity Market (NEM) of Australia and

variations in the generation mix, there has been approximately a 4% decrease in electric power

emissions from 2012-2013 to 2013-2014. Generation of renewable energy is predominantly

hydro though solar and wind has also been on the rise. Various environmental factors have

mostly caused variation in the hydro generation while a slow-down in the deployment of the

renewables has led to the increased production of the black coal generators. The successive

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

Australian governments have been encouraged to transition away from the fossil fuel based

generation by increasing domestic and international concerns related to GHG emissions.

2.0 The current Australian renewable energy policy

The dramatic changes in renewable energy policy environment have been caused by a change of

the Australia’s federal government. Uncertainty has characterized the policy environment with

strategic priorities differing from one political party to the other and even within the ideologies

of the same parties (Byrnes et al. 2013, p.123). On both sides of politics, political uncertainty

over leadership at the federal level implies that a broader risk is a consequence of internal party

priorities. The focus of the new renewable energy policy environment is on the reduction of costs

of electricity, least cost energy production, ensuring the development of the extractive industries

in Australia such as gas sector is enhanced and allocative efficiency is realized. The energy

policy goals of the Australian government, as well as its political ideologies, have been set out in

a new Energy White Paper (Byrnes et al. 2013, p. 101). The White Paper concentrates on the

themes of the temporary Energy Green Paper like reduction of pressure on the energy expenses

for businesses and households. It also looks into the improvement of international

competitiveness, increased exports and removal of interventions which are considered

inappropriate and bars business innovation and competition.

The focus of the White Paper is on the themes of consumer cost reduction by increased

competition, facilitation of resource development and innovation through investment and

improved productivity in the use of energy (Yu & Halog 2015, p.141). As a result of productive

investment and market operation, the energy mix of Australia will grow in diversity over time.

Cost reflective tariff pricing enhances reduction of network investment driven by the peak loads

and related expenses as well as increased demand management. Uniform or regulated tariffs are

Australian governments have been encouraged to transition away from the fossil fuel based

generation by increasing domestic and international concerns related to GHG emissions.

2.0 The current Australian renewable energy policy

The dramatic changes in renewable energy policy environment have been caused by a change of

the Australia’s federal government. Uncertainty has characterized the policy environment with

strategic priorities differing from one political party to the other and even within the ideologies

of the same parties (Byrnes et al. 2013, p.123). On both sides of politics, political uncertainty

over leadership at the federal level implies that a broader risk is a consequence of internal party

priorities. The focus of the new renewable energy policy environment is on the reduction of costs

of electricity, least cost energy production, ensuring the development of the extractive industries

in Australia such as gas sector is enhanced and allocative efficiency is realized. The energy

policy goals of the Australian government, as well as its political ideologies, have been set out in

a new Energy White Paper (Byrnes et al. 2013, p. 101). The White Paper concentrates on the

themes of the temporary Energy Green Paper like reduction of pressure on the energy expenses

for businesses and households. It also looks into the improvement of international

competitiveness, increased exports and removal of interventions which are considered

inappropriate and bars business innovation and competition.

The focus of the White Paper is on the themes of consumer cost reduction by increased

competition, facilitation of resource development and innovation through investment and

improved productivity in the use of energy (Yu & Halog 2015, p.141). As a result of productive

investment and market operation, the energy mix of Australia will grow in diversity over time.

Cost reflective tariff pricing enhances reduction of network investment driven by the peak loads

and related expenses as well as increased demand management. Uniform or regulated tariffs are

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

predominantly used in Australia (Byrnes et al. 2013, p.146). Despite the associated benefits in

the approach relating to reduced pressure on network investment and reduced cross-subsidies, it

is apparent that there is limited recognition of the capacity for issues touching on equity. It is also

arguable that the function of the non-monetary signals for the behavior of electricity demand for

some of the users. The users of rural electricity benefiting from subsidized electricity resulting

from the high cost of local supply are likely to face vulnerability to the policies of cost-reflective

tariffs.

Direct policy discussion related to renewable energy has been relatively minimal over an

extended period. The focus of the policy is in large part on ensuring that a (reduced) target of

renewables is kept and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) and Australian Renewable

Energy Agency (ARENA) are abolished. The roles of these government agencies include

facilitation of access to finance and commercialization of the technologies of renewable energy

(Head et al. 2014, p.66). Despite emissions abatement being a priority, internalizing externalities

of the environment which include emissions generated from the fossil fuels is not prioritized.

Nevertheless, the low emission technologies have a policy support especially coal which

undergoes carbon capture and storage. The policy environment set up by the government intends

to be neutral technologically because given the insights into the needs of the market; the industry

best makes decisions regarding investment on the assets which are to be generated in the future

including the technological choice.

The view that price signals are diluted, competition shielded and energy markets distorted is

reflected by the focus on the provision of subsidies and removal of regulatory barriers (Sims,

Rogner & Gregory 2003, p.134). The market regulations and interventions should not stifle

competition and consumer choice but should instead highly encourage such aspects, and cost-

predominantly used in Australia (Byrnes et al. 2013, p.146). Despite the associated benefits in

the approach relating to reduced pressure on network investment and reduced cross-subsidies, it

is apparent that there is limited recognition of the capacity for issues touching on equity. It is also

arguable that the function of the non-monetary signals for the behavior of electricity demand for

some of the users. The users of rural electricity benefiting from subsidized electricity resulting

from the high cost of local supply are likely to face vulnerability to the policies of cost-reflective

tariffs.

Direct policy discussion related to renewable energy has been relatively minimal over an

extended period. The focus of the policy is in large part on ensuring that a (reduced) target of

renewables is kept and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) and Australian Renewable

Energy Agency (ARENA) are abolished. The roles of these government agencies include

facilitation of access to finance and commercialization of the technologies of renewable energy

(Head et al. 2014, p.66). Despite emissions abatement being a priority, internalizing externalities

of the environment which include emissions generated from the fossil fuels is not prioritized.

Nevertheless, the low emission technologies have a policy support especially coal which

undergoes carbon capture and storage. The policy environment set up by the government intends

to be neutral technologically because given the insights into the needs of the market; the industry

best makes decisions regarding investment on the assets which are to be generated in the future

including the technological choice.

The view that price signals are diluted, competition shielded and energy markets distorted is

reflected by the focus on the provision of subsidies and removal of regulatory barriers (Sims,

Rogner & Gregory 2003, p.134). The market regulations and interventions should not stifle

competition and consumer choice but should instead highly encourage such aspects, and cost-

6

benefit analysis is a primary requirement needed for such regulations. Definition of investment

outcomes is driven by the inherent focus on the use of the competitive energy markets. The

greater focus on the policy appears to be in the gas industry development, export of energy such

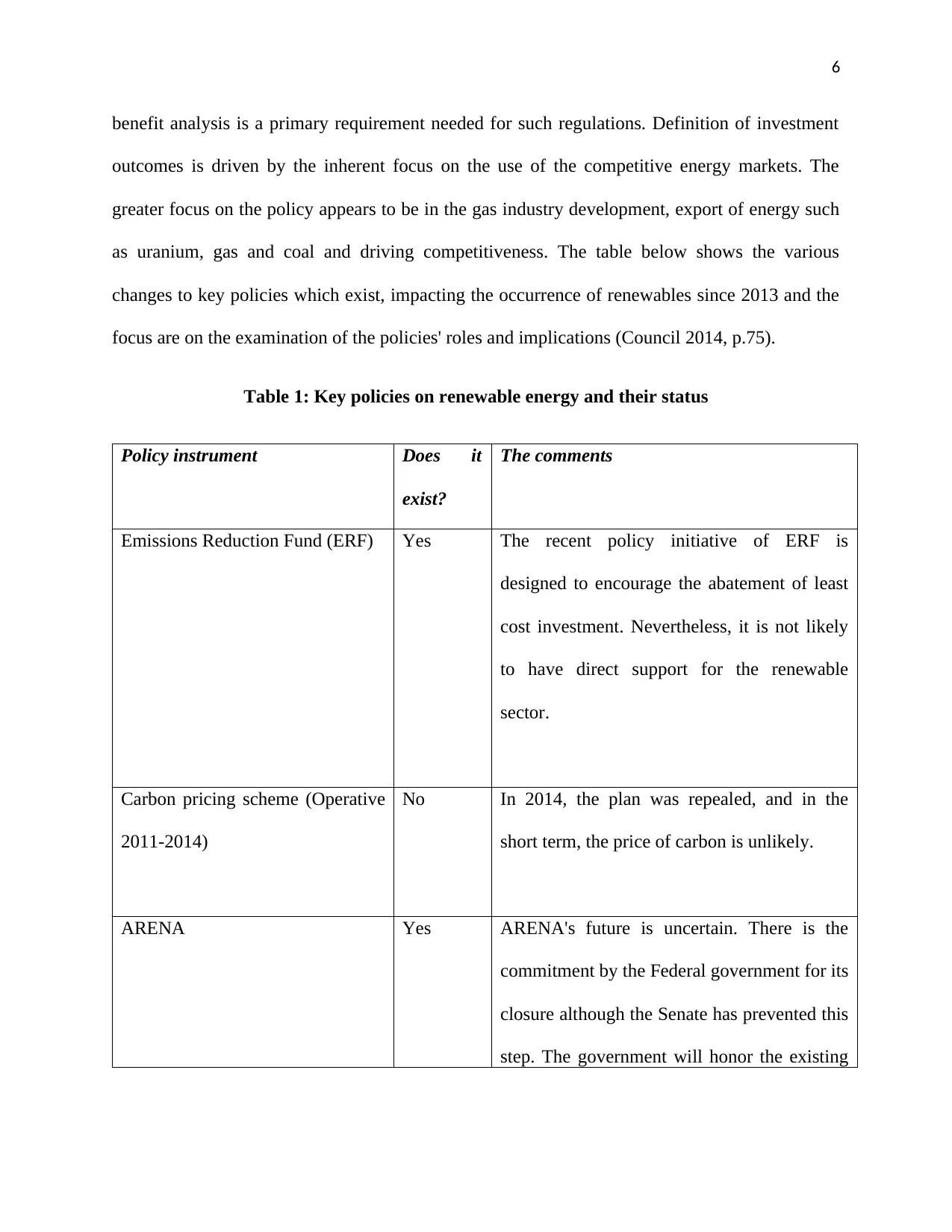

as uranium, gas and coal and driving competitiveness. The table below shows the various

changes to key policies which exist, impacting the occurrence of renewables since 2013 and the

focus are on the examination of the policies' roles and implications (Council 2014, p.75).

Table 1: Key policies on renewable energy and their status

Policy instrument Does it

exist?

The comments

Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) Yes The recent policy initiative of ERF is

designed to encourage the abatement of least

cost investment. Nevertheless, it is not likely

to have direct support for the renewable

sector.

Carbon pricing scheme (Operative

2011-2014)

No In 2014, the plan was repealed, and in the

short term, the price of carbon is unlikely.

ARENA Yes ARENA's future is uncertain. There is the

commitment by the Federal government for its

closure although the Senate has prevented this

step. The government will honor the existing

benefit analysis is a primary requirement needed for such regulations. Definition of investment

outcomes is driven by the inherent focus on the use of the competitive energy markets. The

greater focus on the policy appears to be in the gas industry development, export of energy such

as uranium, gas and coal and driving competitiveness. The table below shows the various

changes to key policies which exist, impacting the occurrence of renewables since 2013 and the

focus are on the examination of the policies' roles and implications (Council 2014, p.75).

Table 1: Key policies on renewable energy and their status

Policy instrument Does it

exist?

The comments

Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) Yes The recent policy initiative of ERF is

designed to encourage the abatement of least

cost investment. Nevertheless, it is not likely

to have direct support for the renewable

sector.

Carbon pricing scheme (Operative

2011-2014)

No In 2014, the plan was repealed, and in the

short term, the price of carbon is unlikely.

ARENA Yes ARENA's future is uncertain. There is the

commitment by the Federal government for its

closure although the Senate has prevented this

step. The government will honor the existing

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

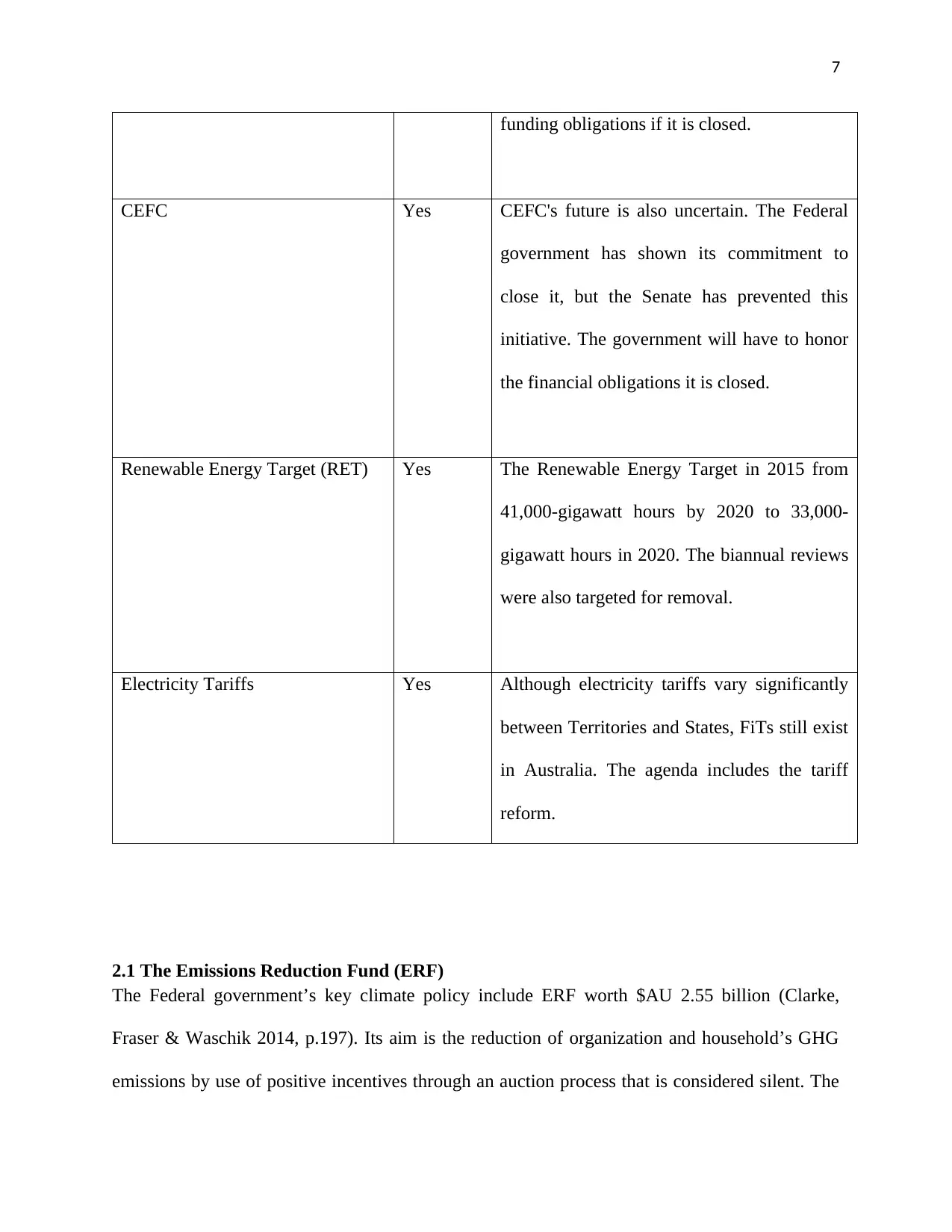

funding obligations if it is closed.

CEFC Yes CEFC's future is also uncertain. The Federal

government has shown its commitment to

close it, but the Senate has prevented this

initiative. The government will have to honor

the financial obligations it is closed.

Renewable Energy Target (RET) Yes The Renewable Energy Target in 2015 from

41,000-gigawatt hours by 2020 to 33,000-

gigawatt hours in 2020. The biannual reviews

were also targeted for removal.

Electricity Tariffs Yes Although electricity tariffs vary significantly

between Territories and States, FiTs still exist

in Australia. The agenda includes the tariff

reform.

2.1 The Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF)

The Federal government’s key climate policy include ERF worth $AU 2.55 billion (Clarke,

Fraser & Waschik 2014, p.197). Its aim is the reduction of organization and household’s GHG

emissions by use of positive incentives through an auction process that is considered silent. The

funding obligations if it is closed.

CEFC Yes CEFC's future is also uncertain. The Federal

government has shown its commitment to

close it, but the Senate has prevented this

initiative. The government will have to honor

the financial obligations it is closed.

Renewable Energy Target (RET) Yes The Renewable Energy Target in 2015 from

41,000-gigawatt hours by 2020 to 33,000-

gigawatt hours in 2020. The biannual reviews

were also targeted for removal.

Electricity Tariffs Yes Although electricity tariffs vary significantly

between Territories and States, FiTs still exist

in Australia. The agenda includes the tariff

reform.

2.1 The Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF)

The Federal government’s key climate policy include ERF worth $AU 2.55 billion (Clarke,

Fraser & Waschik 2014, p.197). Its aim is the reduction of organization and household’s GHG

emissions by use of positive incentives through an auction process that is considered silent. The

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

government has imposed a maximum bid price that remains undisclosed, and any project will not

be paid for if it goes above the set bid price. It is also committed to buying 80% of the emissions’

volume falling below the maximum bid price for every auction (Regulator 2015, p.176). The

carbon credits are paid at the bid price if the process is successful at the auction. The selection of

successful projects is solely based on the lowest bidder. This policy looks into directing

strategies of reducing emissions to the least cost projects and favoring minimal incremental

variations such as forestry and light replacement in industrial buildings over projects that are

more capital intensive (Walsh, Russell-Smith & Cowley 2014, p.131).

The core objective of this policy is to aid Australia in meeting its target of emission reduction of

5% below 2000 levels by the year 2020 through a scheme which ensures cheapest methods of

emissions reduction thus increasing productivity and reducing costs (Byrnes & Brown 2015,

p.202). ERF covers a non-exhaustive list of projects including:

Improvement of agricultural soils.

Reduction of waste coal mine gas.

Revegetation and reforestation.

Capturing the landfill gas.

Improvements in the efficiency of energy.

Use of technological development to reduce electricity generator emissions.

Since ERF is a new policy in Australia, it is not easy to carry out an assessment of the impact it

has on the renewable sector. Nevertheless, it is unlikely to be favorable to the deployment of

renewables given its focus and objectives on the efficiency of energy and the capture and storage

of emissions (Byrnes & Brown 2015, p.199). A significant support to the existing operations is

government has imposed a maximum bid price that remains undisclosed, and any project will not

be paid for if it goes above the set bid price. It is also committed to buying 80% of the emissions’

volume falling below the maximum bid price for every auction (Regulator 2015, p.176). The

carbon credits are paid at the bid price if the process is successful at the auction. The selection of

successful projects is solely based on the lowest bidder. This policy looks into directing

strategies of reducing emissions to the least cost projects and favoring minimal incremental

variations such as forestry and light replacement in industrial buildings over projects that are

more capital intensive (Walsh, Russell-Smith & Cowley 2014, p.131).

The core objective of this policy is to aid Australia in meeting its target of emission reduction of

5% below 2000 levels by the year 2020 through a scheme which ensures cheapest methods of

emissions reduction thus increasing productivity and reducing costs (Byrnes & Brown 2015,

p.202). ERF covers a non-exhaustive list of projects including:

Improvement of agricultural soils.

Reduction of waste coal mine gas.

Revegetation and reforestation.

Capturing the landfill gas.

Improvements in the efficiency of energy.

Use of technological development to reduce electricity generator emissions.

Since ERF is a new policy in Australia, it is not easy to carry out an assessment of the impact it

has on the renewable sector. Nevertheless, it is unlikely to be favorable to the deployment of

renewables given its focus and objectives on the efficiency of energy and the capture and storage

of emissions (Byrnes & Brown 2015, p.199). A significant support to the existing operations is

9

provided by the scheme though it does little as far as support of new households and businesses

without emissions’ track record to abate is concerned.

2.2 Carbon pricing

The previous labor government introduced the carbon pricing scheme to help in internalizing the

costs of carbon for the primary polluters. The fact that carbon pricing was removed in 2014 after

some negotiations is one of the major election scorecards for the current regime (Fahimnia et al.

2013, p.214). As a result, carbon price no longer exists in Australia unless the price is provided

by the ERF. However, forming part of the scheme were other measures which include CEFC and

ARENA, and they have not yet been removed. Some parts of Australian electorate have

exhibited hostility to pricing carbon meaning that the absence of global agreement, political

leadership, tax or a carbon trading scheme have largely contributed to such behaviors.

2.3 The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA)

The role of ARENA is fundamental to improve the increased supply of renewable energy and the

competitiveness of renewables (Sioshansi 2011, p.104). It is technology impious and focused on

the erosion of commercialization and technological barriers and sharing of knowledge. The

senate has thwarted the attempts by the Australian government to close ARENA. The agency has

continued to assess and fund projects despite its pending demise. At the time of its repeal, the

government has committed honoring the funds which are allocated by ARENA.

ARENA carries out an enabling function for initiatives and projects faced with

commercialization and technical challenges that hinder market support (Simpson & Clifton 2014,

p.188). Its focus is more on commercialization of technology rather than the approaches which

are utilized. Some projects especially in the remote communities are however faced with

multifaceted and complex commercialization changes and may not easily match the remit of

provided by the scheme though it does little as far as support of new households and businesses

without emissions’ track record to abate is concerned.

2.2 Carbon pricing

The previous labor government introduced the carbon pricing scheme to help in internalizing the

costs of carbon for the primary polluters. The fact that carbon pricing was removed in 2014 after

some negotiations is one of the major election scorecards for the current regime (Fahimnia et al.

2013, p.214). As a result, carbon price no longer exists in Australia unless the price is provided

by the ERF. However, forming part of the scheme were other measures which include CEFC and

ARENA, and they have not yet been removed. Some parts of Australian electorate have

exhibited hostility to pricing carbon meaning that the absence of global agreement, political

leadership, tax or a carbon trading scheme have largely contributed to such behaviors.

2.3 The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA)

The role of ARENA is fundamental to improve the increased supply of renewable energy and the

competitiveness of renewables (Sioshansi 2011, p.104). It is technology impious and focused on

the erosion of commercialization and technological barriers and sharing of knowledge. The

senate has thwarted the attempts by the Australian government to close ARENA. The agency has

continued to assess and fund projects despite its pending demise. At the time of its repeal, the

government has committed honoring the funds which are allocated by ARENA.

ARENA carries out an enabling function for initiatives and projects faced with

commercialization and technical challenges that hinder market support (Simpson & Clifton 2014,

p.188). Its focus is more on commercialization of technology rather than the approaches which

are utilized. Some projects especially in the remote communities are however faced with

multifaceted and complex commercialization changes and may not easily match the remit of

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

ARENA. The kind of risk that surrounds the future of ARENA is not conducive to the

deployment of renewables. The project development is resource and time intensive. The

incentive for resource and time allocation is most likely to lead to the reduction of particular

uncertainty concerning the future of ARENA.

2.4 The Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC)

The CEFC is a financier getting its funds from the government to aid in overcoming the funding

challenges which are associated with the development of clean energy including technologies on

low emissions and renewable energy. Its focus is on the provision of funds at a concessional rate

for projects on clean energy with a positive rate of return. The concession highly relies on the

benefits that do not emanate from within provided by the project and can be in the form of longer

duration, reduced costs and higher rate of risk (Hua, Oliphant & Hu 2016, p.45).

The Senate has barred the commitment by the Australian government to ensure CEFC is closed.

The reason for the closure of CEFC comes into sight to provide a reflection on the perception

that the government is not to provide funds if the profile of the project risk is unacceptable to the

private sector. The CEO of CEFC asserted that the willingness of private financier to take part in

the Australian market had been reduced by the uncertain and complex policy environment

(Martin & Rice 2015, p.97). Therefore, the CEFC’s role is critical due to this policy

environment. The availability of finance is restricted by the tendency to focus on established

businesses and the requirement for concessional market returns in an attempt to take charge of

the profile of credit risk. The large projects with lower transaction costs have high capacity to

attract finance from the CEFC specifically those that involve more established businesses. The

organizations which are less established with limited access to funding like smaller projects,

small businesses or community groups may not be included (Hua, Oliphant & Hu 2016, p.49).

ARENA. The kind of risk that surrounds the future of ARENA is not conducive to the

deployment of renewables. The project development is resource and time intensive. The

incentive for resource and time allocation is most likely to lead to the reduction of particular

uncertainty concerning the future of ARENA.

2.4 The Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC)

The CEFC is a financier getting its funds from the government to aid in overcoming the funding

challenges which are associated with the development of clean energy including technologies on

low emissions and renewable energy. Its focus is on the provision of funds at a concessional rate

for projects on clean energy with a positive rate of return. The concession highly relies on the

benefits that do not emanate from within provided by the project and can be in the form of longer

duration, reduced costs and higher rate of risk (Hua, Oliphant & Hu 2016, p.45).

The Senate has barred the commitment by the Australian government to ensure CEFC is closed.

The reason for the closure of CEFC comes into sight to provide a reflection on the perception

that the government is not to provide funds if the profile of the project risk is unacceptable to the

private sector. The CEO of CEFC asserted that the willingness of private financier to take part in

the Australian market had been reduced by the uncertain and complex policy environment

(Martin & Rice 2015, p.97). Therefore, the CEFC’s role is critical due to this policy

environment. The availability of finance is restricted by the tendency to focus on established

businesses and the requirement for concessional market returns in an attempt to take charge of

the profile of credit risk. The large projects with lower transaction costs have high capacity to

attract finance from the CEFC specifically those that involve more established businesses. The

organizations which are less established with limited access to funding like smaller projects,

small businesses or community groups may not be included (Hua, Oliphant & Hu 2016, p.49).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

Lack of products’ standardization, high costs of transactions, perceived risks of investment,

locational challenges, inability to acquire co-finance or complexity related to the alignment of

stakeholders are some of the causes for their exclusion.

2.5 The Renewable Energy Target (RET)

The aim of RET is the reduction of GHG emissions from the generation of electricity through the

provision of certificates for generation of renewable energy (Cludius, Forrest & MacGill 2014,

p.55). The large systems are given proper documentation based on the generated MWh while the

small systems which are less than 100 kW are provided with upfront payments. The electricity

retailers who are liable entities have to make purchases of a given number of certificates. This

policy is significant as it has played a key function in the facilitation of the deployment of

renewables and reduction of emissions in Australia. RET was reviewed in 2014 by the federal

government (Panel 2014, p.133) signaling its intention to have the target reduced and it was

concluded that:

Given the availability of abatement alternatives for lower cost emission, the cost to the

community of the RET has shot up.

RET is funded via a cross-subsidy by the consumers, electricity retailers and incumbent

generators.

The impact of RET on the prices of electricity is small.

Approximately $13 billion of the large-scale generation which is not required will be

developed given the changes in the electricity environment.

RET provides investment incentive in the production of renewable energy which is not

essential in meeting demand and not viable without subsidy by RET.

Lack of products’ standardization, high costs of transactions, perceived risks of investment,

locational challenges, inability to acquire co-finance or complexity related to the alignment of

stakeholders are some of the causes for their exclusion.

2.5 The Renewable Energy Target (RET)

The aim of RET is the reduction of GHG emissions from the generation of electricity through the

provision of certificates for generation of renewable energy (Cludius, Forrest & MacGill 2014,

p.55). The large systems are given proper documentation based on the generated MWh while the

small systems which are less than 100 kW are provided with upfront payments. The electricity

retailers who are liable entities have to make purchases of a given number of certificates. This

policy is significant as it has played a key function in the facilitation of the deployment of

renewables and reduction of emissions in Australia. RET was reviewed in 2014 by the federal

government (Panel 2014, p.133) signaling its intention to have the target reduced and it was

concluded that:

Given the availability of abatement alternatives for lower cost emission, the cost to the

community of the RET has shot up.

RET is funded via a cross-subsidy by the consumers, electricity retailers and incumbent

generators.

The impact of RET on the prices of electricity is small.

Approximately $13 billion of the large-scale generation which is not required will be

developed given the changes in the electricity environment.

RET provides investment incentive in the production of renewable energy which is not

essential in meeting demand and not viable without subsidy by RET.

12

The Federal government is committed to enabling the reduction of RET and initially set targets

of 26,000 GWh following the review of the RET. At the period RET of 41,000 GWh of

generation of renewable energy by 2020 was being written was reduced to approximately 33,000

GWh in 2015 (Stock 2015, p.111). This is a clear reflection of the contractual amount between

the two key players resulting from the protracted negotiations. Moreover, there has been

considerable confusion surrounding the involvement of wood waste as a source of renewables

and trade exemptions exposed in industries from the RET.

RET has played a crucial role in the facilitation of the deployment of the renewables in Australia.

If the reduced RET target is made efficient, it will assist in the reduction of uncertainty through

the provision of a floor target which is not likely to go down in the near future (Martin & Rice

2012, p.162). Significant reduction in the investment in the renewable energy especially for the

large-scale systems has been caused by the uncertainty that surrounds the RET.

2.6 Tariff policies and Feed in Tariffs (FiTs)

The Territory and the State have the responsibility of implementing the tariff policies. The FiTs

of the household have entirely gone down across all the States and Territories and are currently

low. As a result of information asymmetry regarding the impacts of network and capacity of

offsetting the wholesale price (Oliva, MacGill & Passey 2014, p.152), there is uncertainty in the

value of household PV that is under exportation to the grid. The regional DNSP in Western

Australia came up with a scheme with FiTs to a tune of $0.50/kWh (Byrnes et al. 2016: 210) for

the encouragement of the deployment particularly in the off-grid diesel networks although as a

result of a range of non-monetary and monetary barriers, there has been limited success. The

rationales behind reductions in FiT are twofold. First of all the household solar PV in the urban

areas is relatively cost competitive. Secondly, the declining revenue and the cost of network

The Federal government is committed to enabling the reduction of RET and initially set targets

of 26,000 GWh following the review of the RET. At the period RET of 41,000 GWh of

generation of renewable energy by 2020 was being written was reduced to approximately 33,000

GWh in 2015 (Stock 2015, p.111). This is a clear reflection of the contractual amount between

the two key players resulting from the protracted negotiations. Moreover, there has been

considerable confusion surrounding the involvement of wood waste as a source of renewables

and trade exemptions exposed in industries from the RET.

RET has played a crucial role in the facilitation of the deployment of the renewables in Australia.

If the reduced RET target is made efficient, it will assist in the reduction of uncertainty through

the provision of a floor target which is not likely to go down in the near future (Martin & Rice

2012, p.162). Significant reduction in the investment in the renewable energy especially for the

large-scale systems has been caused by the uncertainty that surrounds the RET.

2.6 Tariff policies and Feed in Tariffs (FiTs)

The Territory and the State have the responsibility of implementing the tariff policies. The FiTs

of the household have entirely gone down across all the States and Territories and are currently

low. As a result of information asymmetry regarding the impacts of network and capacity of

offsetting the wholesale price (Oliva, MacGill & Passey 2014, p.152), there is uncertainty in the

value of household PV that is under exportation to the grid. The regional DNSP in Western

Australia came up with a scheme with FiTs to a tune of $0.50/kWh (Byrnes et al. 2016: 210) for

the encouragement of the deployment particularly in the off-grid diesel networks although as a

result of a range of non-monetary and monetary barriers, there has been limited success. The

rationales behind reductions in FiT are twofold. First of all the household solar PV in the urban

areas is relatively cost competitive. Secondly, the declining revenue and the cost of network

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 17

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.