Dairy Industry Sustainability Challenges

VerifiedAdded on 2020/03/07

|12

|3415

|114

AI Summary

This assignment delves into the pressing sustainability challenges confronting the dairy industry. It examines key issues such as environmental impact, resource management, animal welfare, and economic viability. The analysis draws upon various research studies and reports to highlight the drivers, barriers, and potential solutions for enhancing the sustainability of dairy production systems.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 1

STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT OF THE AUSTRALIAN DAIRY INDUSTRY

by (Name):

Course:

Tutor:

College:

City/State:

Date:

STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT OF THE AUSTRALIAN DAIRY INDUSTRY

by (Name):

Course:

Tutor:

College:

City/State:

Date:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 2

Introduction

The Australian Dairy industry has contributed massively to the country’s economy

with numerous jobs created on dairy farms among other sectors. Indeed, the $13 billion sector

is an important cornerstone to the wellbeing of majority of the Australians. According to

Gourley et al. (2012), Dairy, in terms of farm gate value has a large export value with

approximately 35% of the country’s dairy production exported annually.

However, increased international competition particularly from countries such as the

U.S and New Zealand means that the sector is currently experiencing a consistent decline

(Chapman et al., 2014). This is evident from the closure of some processing plants, and this

has weaken the individual ability of such companies to sufficiently pay dairy farmers.

As such, this report examines the competitive environment of the Australian dairy

industry, and this will entail a special insight into the dairy crisis that has engulfed the

country. The report further explores the strategic landscape that will include an analysis of

the Porter’s Five Forces within the Australian Dairy Industry. Moreover the report provides a

comprehensive competitive advantage and quantitative analysis of the Australian Dairy

industry.

Competitive environment: Understanding the Australian dairy crisis

The Australian dairy crisis started when the two major processing companies, Murray

Goulbun and Fonterra announced unexpected and backdated price cuts. This decision

affected most of the Australian farmers especially from the Southern regions whose only

source of income had been disrupted (McDowell and Nash, 2012). Most of these farmers

relied on the expanding Asian markets especially the Chinese increased demand for powder

milk products.

Tracing background of the crisis

Introduction

The Australian Dairy industry has contributed massively to the country’s economy

with numerous jobs created on dairy farms among other sectors. Indeed, the $13 billion sector

is an important cornerstone to the wellbeing of majority of the Australians. According to

Gourley et al. (2012), Dairy, in terms of farm gate value has a large export value with

approximately 35% of the country’s dairy production exported annually.

However, increased international competition particularly from countries such as the

U.S and New Zealand means that the sector is currently experiencing a consistent decline

(Chapman et al., 2014). This is evident from the closure of some processing plants, and this

has weaken the individual ability of such companies to sufficiently pay dairy farmers.

As such, this report examines the competitive environment of the Australian dairy

industry, and this will entail a special insight into the dairy crisis that has engulfed the

country. The report further explores the strategic landscape that will include an analysis of

the Porter’s Five Forces within the Australian Dairy Industry. Moreover the report provides a

comprehensive competitive advantage and quantitative analysis of the Australian Dairy

industry.

Competitive environment: Understanding the Australian dairy crisis

The Australian dairy crisis started when the two major processing companies, Murray

Goulbun and Fonterra announced unexpected and backdated price cuts. This decision

affected most of the Australian farmers especially from the Southern regions whose only

source of income had been disrupted (McDowell and Nash, 2012). Most of these farmers

relied on the expanding Asian markets especially the Chinese increased demand for powder

milk products.

Tracing background of the crisis

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 3

In essence, the Ukraine conflict is directly linked to the global milk crisis that also

affected the Australian farmers. This was particularly true after the Malaysian Airlines flight

MH17 was allegedly shot down by Russian backed rebels in Crimea killing everybody on

board. The result was a protracted trade war which saw Russia slapped with numerous

sanctions from the European Union and the U.S (Buys et al., 2014). Russia reacted by

banning all imports from Western dairy companies from coming into the country.

The Australian dairy farmers were greatly affected by this decision taken by Russian

government. This is because milk and dairy products from the European Union and the U.S

started flooding markets that were initially dominated by Australian companies. To be

precise, dairy products from the EU that were initially branded for the Russian markets had to

be rebranded and sold locally and to other new markets such as Asia (Buys et al., 2014).

The outcome was a flooded market with dairy products which prompted major processing

companies to slash their prices to remain competitive. As a result of the Russian ban of

European dairy products, the EU embarked on its long-term objective of eradicating reliance

on dairy production by exploring other viable alternatives and substitutes (Von Keyserlingk

et al., 2013). The EU also removed the milk quotas further propelling a storm that was

already ravaging the Australian dairy industry.

The increased stockpiles of cheese and milk powder among other related products

meant that production had outstripped demand. Prices of dairy products fell and this meant

that farmers were paid less for their commodities. The Chinese market which the Australian

farmers targeted also had a stretched supply of dairy products (Lees et al., 2012).

Correspondingly, New Zealand’s decision to halt the building of milk dehydrators and

explore other feasible production options further affected the Australian Milk industry

(Tiwari et al, 2012). The country reasoned that the reducing global powder milk prices was

bad for the economy and could easily affect other sectors if it was not adequately contained.

In essence, the Ukraine conflict is directly linked to the global milk crisis that also

affected the Australian farmers. This was particularly true after the Malaysian Airlines flight

MH17 was allegedly shot down by Russian backed rebels in Crimea killing everybody on

board. The result was a protracted trade war which saw Russia slapped with numerous

sanctions from the European Union and the U.S (Buys et al., 2014). Russia reacted by

banning all imports from Western dairy companies from coming into the country.

The Australian dairy farmers were greatly affected by this decision taken by Russian

government. This is because milk and dairy products from the European Union and the U.S

started flooding markets that were initially dominated by Australian companies. To be

precise, dairy products from the EU that were initially branded for the Russian markets had to

be rebranded and sold locally and to other new markets such as Asia (Buys et al., 2014).

The outcome was a flooded market with dairy products which prompted major processing

companies to slash their prices to remain competitive. As a result of the Russian ban of

European dairy products, the EU embarked on its long-term objective of eradicating reliance

on dairy production by exploring other viable alternatives and substitutes (Von Keyserlingk

et al., 2013). The EU also removed the milk quotas further propelling a storm that was

already ravaging the Australian dairy industry.

The increased stockpiles of cheese and milk powder among other related products

meant that production had outstripped demand. Prices of dairy products fell and this meant

that farmers were paid less for their commodities. The Chinese market which the Australian

farmers targeted also had a stretched supply of dairy products (Lees et al., 2012).

Correspondingly, New Zealand’s decision to halt the building of milk dehydrators and

explore other feasible production options further affected the Australian Milk industry

(Tiwari et al, 2012). The country reasoned that the reducing global powder milk prices was

bad for the economy and could easily affect other sectors if it was not adequately contained.

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 4

The effects of the Australian milk crisis

The immediate effect of the Australian milk crisis was a reduction in farmers’

incomes with most farmers struggling to keep afloat. Companies such as Murray Goulburn

started diversifying into other nutritional product such as soy milk to sustain their competitive

advantage (McDowell and Nash, 2012). The company was also forced to cut milk prices for

Australian farmers and significantly re-evaluate its profit forecast. Notably, the decision by

Murray Goulburn and Fonterra companies to cut prices exerted the biggest blow to the

Australian dairy industry.

Strategic landscape: Effects of the Porter’s Five Forces within the Australian Dairy

Industry

Threat of competitive rivalry

There are numerous firms that are currently operating in the Australian dairy industry.

As such, there is a comparatively higher level of competitive rivalry in this particular

industry. The companies’ market share vary significantly depending on individual operational

prowess among other market factors (Roberts et al., 2012). With the industry recording

tremendous growth over the last few decades, dairy companies in the sector must upgrade

their products if they are to sustain the fierce global competitions.

According to Klerkx and Nettle (2013), most dairy product consumers relates high

price to better quality and nutritious products, and companies operating in the industry must

comply with such market requirements. Moreover, given the fierce competitive rivalry, most

Australian dairy companies are currently focusing on the development of after-sale service,

and include setting up free health clubs that provides nutrition information and advice to their

consumers among other related consultancy service.

Suppliers’ bargaining power

The effects of the Australian milk crisis

The immediate effect of the Australian milk crisis was a reduction in farmers’

incomes with most farmers struggling to keep afloat. Companies such as Murray Goulburn

started diversifying into other nutritional product such as soy milk to sustain their competitive

advantage (McDowell and Nash, 2012). The company was also forced to cut milk prices for

Australian farmers and significantly re-evaluate its profit forecast. Notably, the decision by

Murray Goulburn and Fonterra companies to cut prices exerted the biggest blow to the

Australian dairy industry.

Strategic landscape: Effects of the Porter’s Five Forces within the Australian Dairy

Industry

Threat of competitive rivalry

There are numerous firms that are currently operating in the Australian dairy industry.

As such, there is a comparatively higher level of competitive rivalry in this particular

industry. The companies’ market share vary significantly depending on individual operational

prowess among other market factors (Roberts et al., 2012). With the industry recording

tremendous growth over the last few decades, dairy companies in the sector must upgrade

their products if they are to sustain the fierce global competitions.

According to Klerkx and Nettle (2013), most dairy product consumers relates high

price to better quality and nutritious products, and companies operating in the industry must

comply with such market requirements. Moreover, given the fierce competitive rivalry, most

Australian dairy companies are currently focusing on the development of after-sale service,

and include setting up free health clubs that provides nutrition information and advice to their

consumers among other related consultancy service.

Suppliers’ bargaining power

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 5

There is relatively higher bargaining power of the suppliers in the Australian dairy

industry. This is because most of the dairy farms in the country are specialized and produce

in large scale. This implies that farmers can produce larger quantity of milk and control the

quality and supply in the country and global markets (McDowell and Nash, 2012). This has

strengthened the bargaining power of most farmers operating in this industry. Most of the

farmers in the industry also have the requisite management experience, as well as large-scale

farms that can facilitate and sustain higher production.

Most of the country’s dairy products are consumed locally, and this has really

plummeted the growth of the industry (Cary and Roberts, 2011). With the increase in demand

for Australian milk products from some Asia countries, the industry’s competitive capacity

especially in the global markets is set to improve. Moreover, most companies in the industry

possess the inherent ability to control milk purchase contracts based on quality and quantity

of their dairy products (Roberts et al., 2012). However, the recent dairy crisis in the country

have exposed the local dairy industry in a flaccid position that if not adequately addressed

will significantly affect the industry’s long-term survival.

The consumers’ bargaining power

Consumers in the Australian dairy industry have higher bargaining power. This can be

accredited to the large number of companies that are currently operating in the industry

(McDowell and Nash, 2012). Also, there are numerous dairy products that are available in the

market soaring the consumers’ options. Most dairy product consumers are not swayed by

commodity prices. Quality, product variation and the power of the brand are some of the

most important consumer purchase determinants (Nettle, Brightling and Hope, 2013).

The industry also have numerous direct customers such as dairy products’ distribution

agents, pharmaceutical stores and nutrition clubs in most parts of Australia (Roberts et al.,

2012). These are some of the important players that are significantly influencing the purchase

There is relatively higher bargaining power of the suppliers in the Australian dairy

industry. This is because most of the dairy farms in the country are specialized and produce

in large scale. This implies that farmers can produce larger quantity of milk and control the

quality and supply in the country and global markets (McDowell and Nash, 2012). This has

strengthened the bargaining power of most farmers operating in this industry. Most of the

farmers in the industry also have the requisite management experience, as well as large-scale

farms that can facilitate and sustain higher production.

Most of the country’s dairy products are consumed locally, and this has really

plummeted the growth of the industry (Cary and Roberts, 2011). With the increase in demand

for Australian milk products from some Asia countries, the industry’s competitive capacity

especially in the global markets is set to improve. Moreover, most companies in the industry

possess the inherent ability to control milk purchase contracts based on quality and quantity

of their dairy products (Roberts et al., 2012). However, the recent dairy crisis in the country

have exposed the local dairy industry in a flaccid position that if not adequately addressed

will significantly affect the industry’s long-term survival.

The consumers’ bargaining power

Consumers in the Australian dairy industry have higher bargaining power. This can be

accredited to the large number of companies that are currently operating in the industry

(McDowell and Nash, 2012). Also, there are numerous dairy products that are available in the

market soaring the consumers’ options. Most dairy product consumers are not swayed by

commodity prices. Quality, product variation and the power of the brand are some of the

most important consumer purchase determinants (Nettle, Brightling and Hope, 2013).

The industry also have numerous direct customers such as dairy products’ distribution

agents, pharmaceutical stores and nutrition clubs in most parts of Australia (Roberts et al.,

2012). These are some of the important players that are significantly influencing the purchase

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 6

decisions of some consumers (Henry et al., 2012). The numerous dairy product distribution

points have further expanded consumer options strengthening their respective bargaining

powers.

Substitute products

Dairy products remains to be an instrumental nutritional supplement that is relatively

hard to substitute. As such, the threat of alternative nutritious products is medium. The only

threat to the Australian dairy industry is the control of global market share given the increase

in global competitions. Also, other products such as soy milk and cereal beverages such as

cocoa and coffee possess serious market threat to liquid dairy products (Cary and Roberts,

2011).

New market entrants

Venturing into the dairy industry requires large capital investment and adherence to

strict operational standards. For example, large capital is required to facilitate Moreover,

companies operating in the industry are majorly characterised by stability in growth, higher

profits and larger market shares. As such, any company willing to venture into this market

must be ready to overcome such aggressive market competition and requirements (Roberts et

al., 2012). The industry stresses mostly on product quality, therefore, capturing customer

loyalty may prove difficult especially for new competitors. Correspondingly, most of the

production and distribution channels in the Australian dairy market are full. This implies that

new market entrants must invest heavily to gain some control of the market that is currently

dominated by firms such as Murray Goulburn and Fonterra farmer.

Competitive Advantage Quantitative Analysis

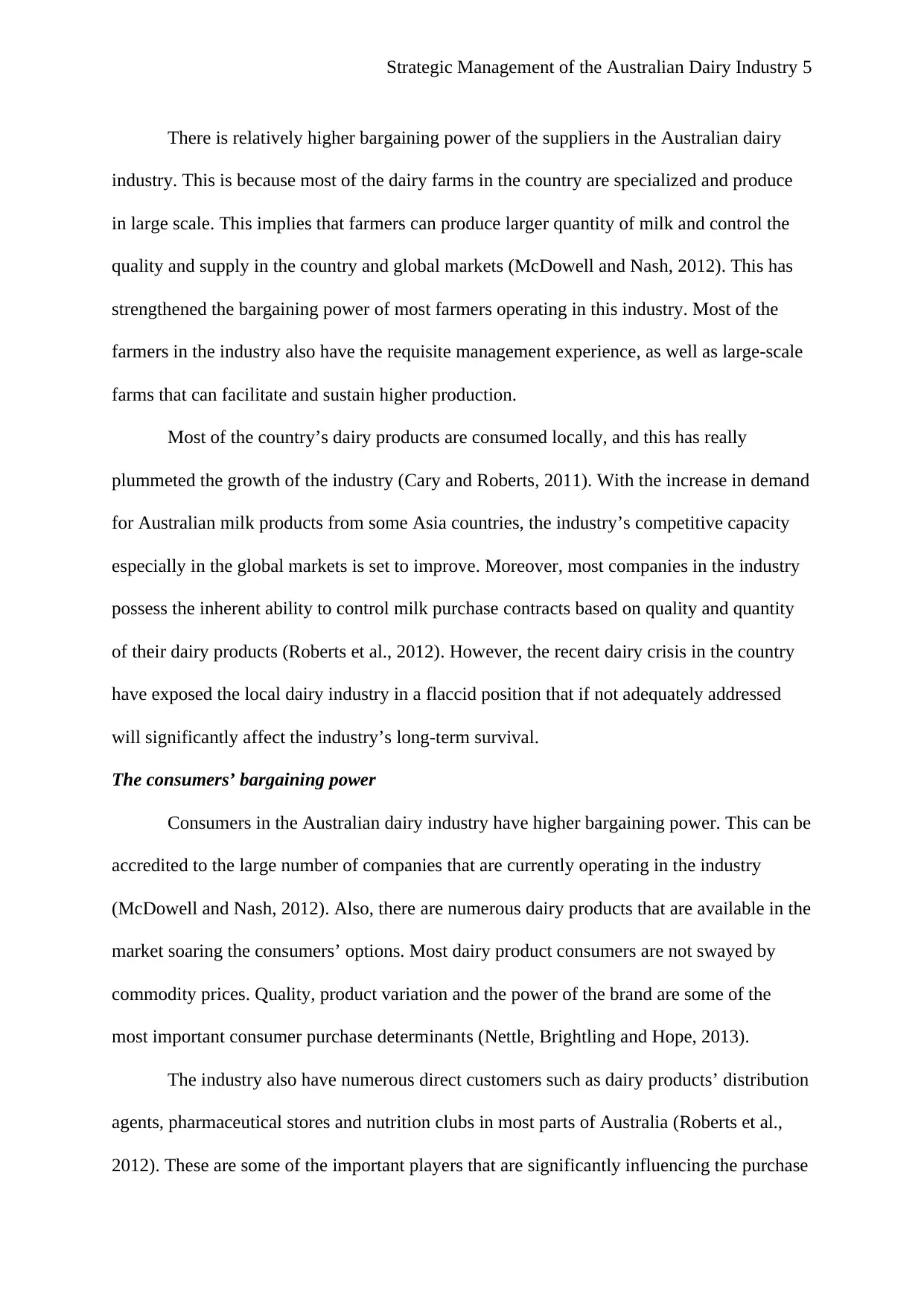

The Australian Dairy industry is greatly affected by international competition. The

table below shows the world dairy industry production from 2013-2016. Global production of

decisions of some consumers (Henry et al., 2012). The numerous dairy product distribution

points have further expanded consumer options strengthening their respective bargaining

powers.

Substitute products

Dairy products remains to be an instrumental nutritional supplement that is relatively

hard to substitute. As such, the threat of alternative nutritious products is medium. The only

threat to the Australian dairy industry is the control of global market share given the increase

in global competitions. Also, other products such as soy milk and cereal beverages such as

cocoa and coffee possess serious market threat to liquid dairy products (Cary and Roberts,

2011).

New market entrants

Venturing into the dairy industry requires large capital investment and adherence to

strict operational standards. For example, large capital is required to facilitate Moreover,

companies operating in the industry are majorly characterised by stability in growth, higher

profits and larger market shares. As such, any company willing to venture into this market

must be ready to overcome such aggressive market competition and requirements (Roberts et

al., 2012). The industry stresses mostly on product quality, therefore, capturing customer

loyalty may prove difficult especially for new competitors. Correspondingly, most of the

production and distribution channels in the Australian dairy market are full. This implies that

new market entrants must invest heavily to gain some control of the market that is currently

dominated by firms such as Murray Goulburn and Fonterra farmer.

Competitive Advantage Quantitative Analysis

The Australian Dairy industry is greatly affected by international competition. The

table below shows the world dairy industry production from 2013-2016. Global production of

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 7

dairy products is currently up with the production growth estimated to increase especially in

from developed countries.

2013 2014 2015 2016

Total production output (millions tons) 700.1 652.4 723.1 699.6

Total trade volume (millions tons) 50.4 41.5 40.4 53.4

Demand of developing nations (kg/person/year) 66.5 67.8 71.5 63.7

Demand of developed countries

(kg/person/year)

246 214 256.2 245

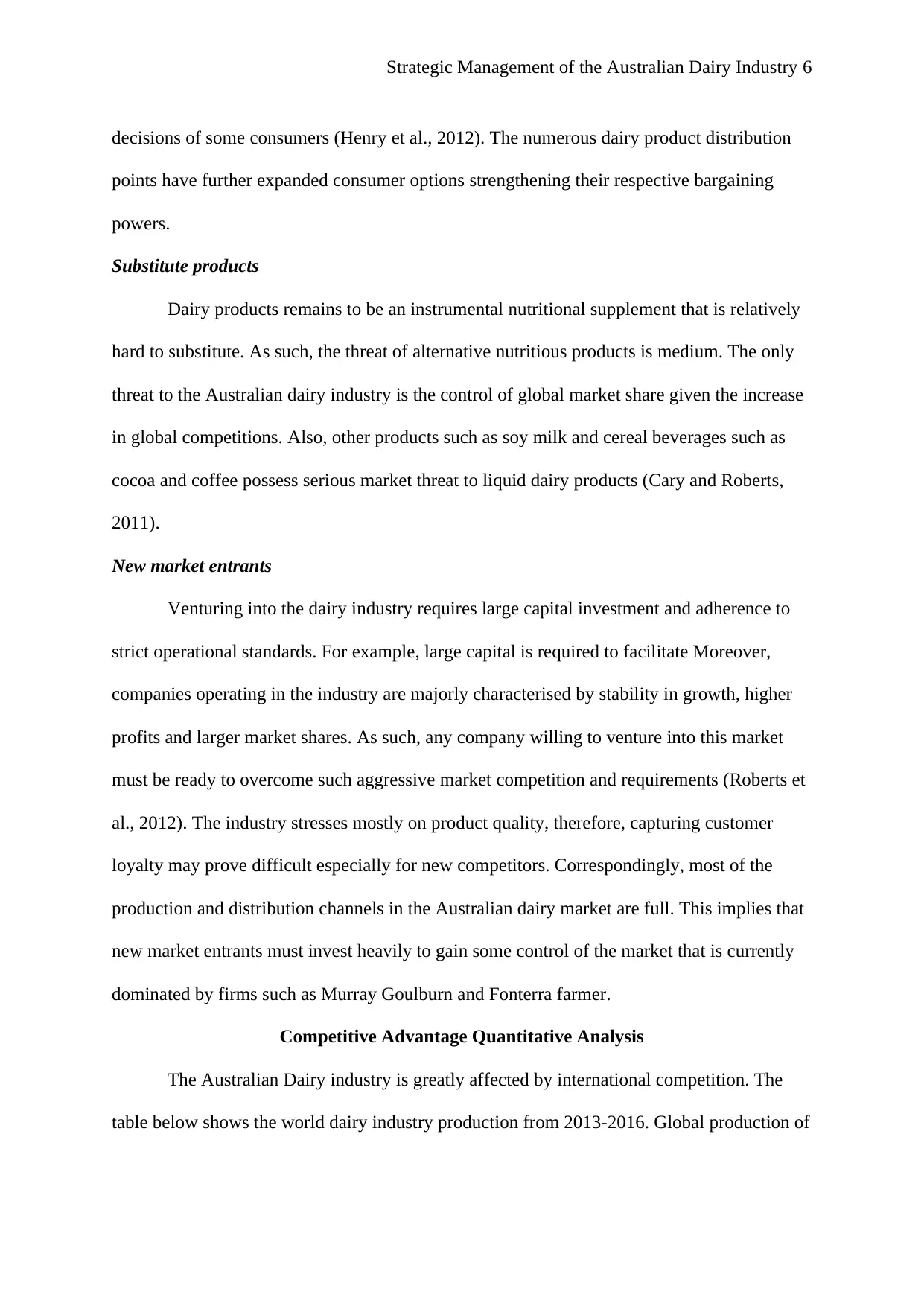

During the 2015 Australian dairy crisis, there was an increase in production and

supply of daily products, but the consumption of such products was limited especially in

Russia (Bardsley and Pech, 2012). The table below also shows the contribution and position

of the Australian dairy industry both locally and in the global markets.

Total number of dairy farms 6,400

Number of people employed on farms 24,750

Number of people employed in processing firms 19,000

People working directly working dairy 43,750

Share of national milk production 100%

Total value of milk leaving farms $3.8 m

Contribution of the dairy farms to the Australian

economy

$2.9 b

Value of dairy products exported $2.8b

Volume of dairy products exported 800000 tonnes

dairy products is currently up with the production growth estimated to increase especially in

from developed countries.

2013 2014 2015 2016

Total production output (millions tons) 700.1 652.4 723.1 699.6

Total trade volume (millions tons) 50.4 41.5 40.4 53.4

Demand of developing nations (kg/person/year) 66.5 67.8 71.5 63.7

Demand of developed countries

(kg/person/year)

246 214 256.2 245

During the 2015 Australian dairy crisis, there was an increase in production and

supply of daily products, but the consumption of such products was limited especially in

Russia (Bardsley and Pech, 2012). The table below also shows the contribution and position

of the Australian dairy industry both locally and in the global markets.

Total number of dairy farms 6,400

Number of people employed on farms 24,750

Number of people employed in processing firms 19,000

People working directly working dairy 43,750

Share of national milk production 100%

Total value of milk leaving farms $3.8 m

Contribution of the dairy farms to the Australian

economy

$2.9 b

Value of dairy products exported $2.8b

Volume of dairy products exported 800000 tonnes

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 8

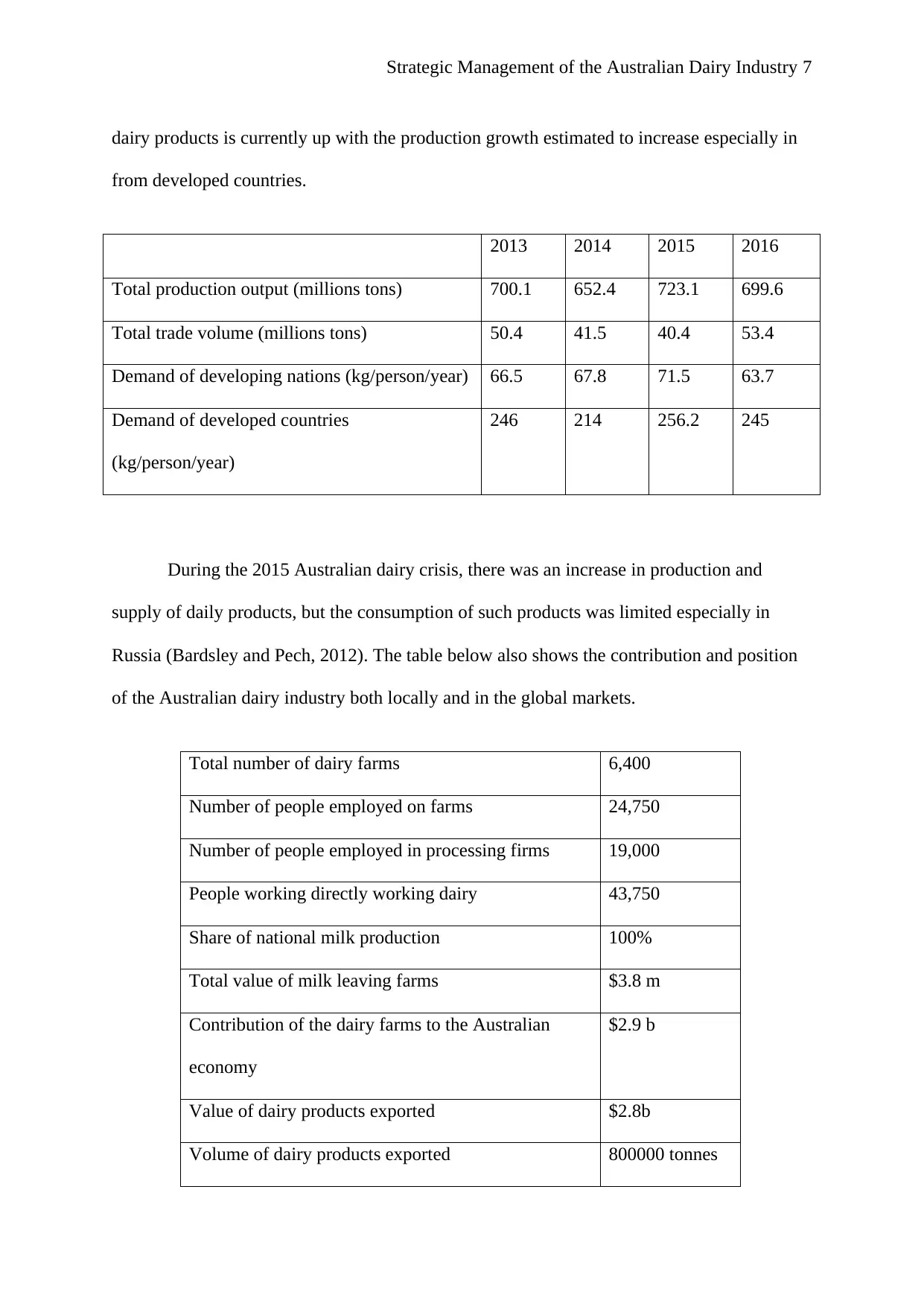

Notably, Australia contribute approximately 6% of the global milk production with

the U.S, European Union and New Zealand leading the pack. Most of Australia’s dairy

products are sold locally given its relatively large local consumer base (McDowell and Nash,

2012). Also, the country export most of its products to some parts of Asia, the Americas, EU

and Africa. The country also receives dairy products imports especially cheese from the U.S

and New Zealand exposing the industry to global competition.

Furthermore, the most popular dairy product that are locally consumed include milk,

cheese, butter and yoghurt as shown in the table below.

Dairy product Consumption per capita

Milk 102 litres

Cheese 13 kg

Butter 4 kg

Yoghurt 7 kg

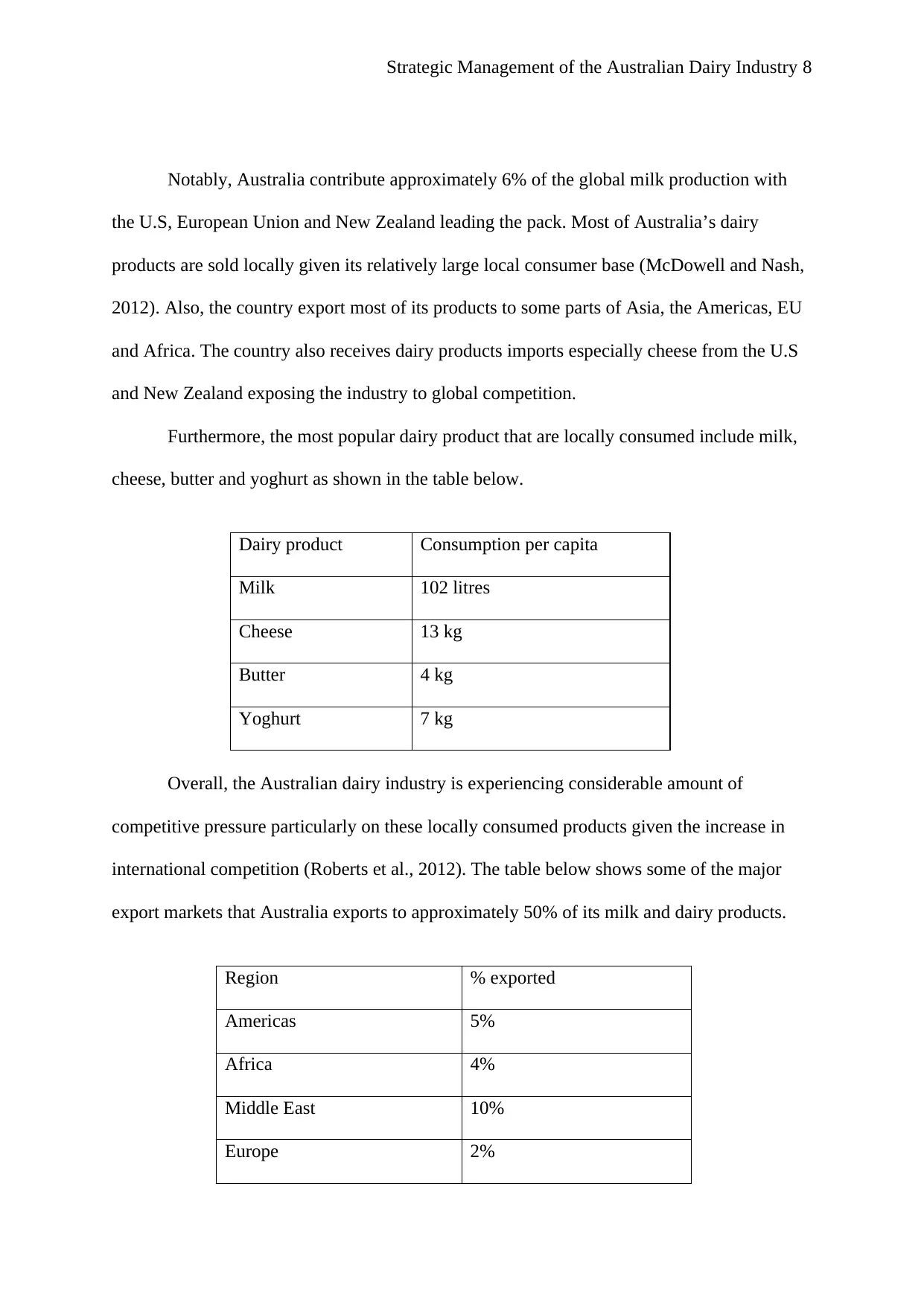

Overall, the Australian dairy industry is experiencing considerable amount of

competitive pressure particularly on these locally consumed products given the increase in

international competition (Roberts et al., 2012). The table below shows some of the major

export markets that Australia exports to approximately 50% of its milk and dairy products.

Region % exported

Americas 5%

Africa 4%

Middle East 10%

Europe 2%

Notably, Australia contribute approximately 6% of the global milk production with

the U.S, European Union and New Zealand leading the pack. Most of Australia’s dairy

products are sold locally given its relatively large local consumer base (McDowell and Nash,

2012). Also, the country export most of its products to some parts of Asia, the Americas, EU

and Africa. The country also receives dairy products imports especially cheese from the U.S

and New Zealand exposing the industry to global competition.

Furthermore, the most popular dairy product that are locally consumed include milk,

cheese, butter and yoghurt as shown in the table below.

Dairy product Consumption per capita

Milk 102 litres

Cheese 13 kg

Butter 4 kg

Yoghurt 7 kg

Overall, the Australian dairy industry is experiencing considerable amount of

competitive pressure particularly on these locally consumed products given the increase in

international competition (Roberts et al., 2012). The table below shows some of the major

export markets that Australia exports to approximately 50% of its milk and dairy products.

Region % exported

Americas 5%

Africa 4%

Middle East 10%

Europe 2%

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 9

South East Asia 30%

Japan 19%

Other parts of Asia 24%

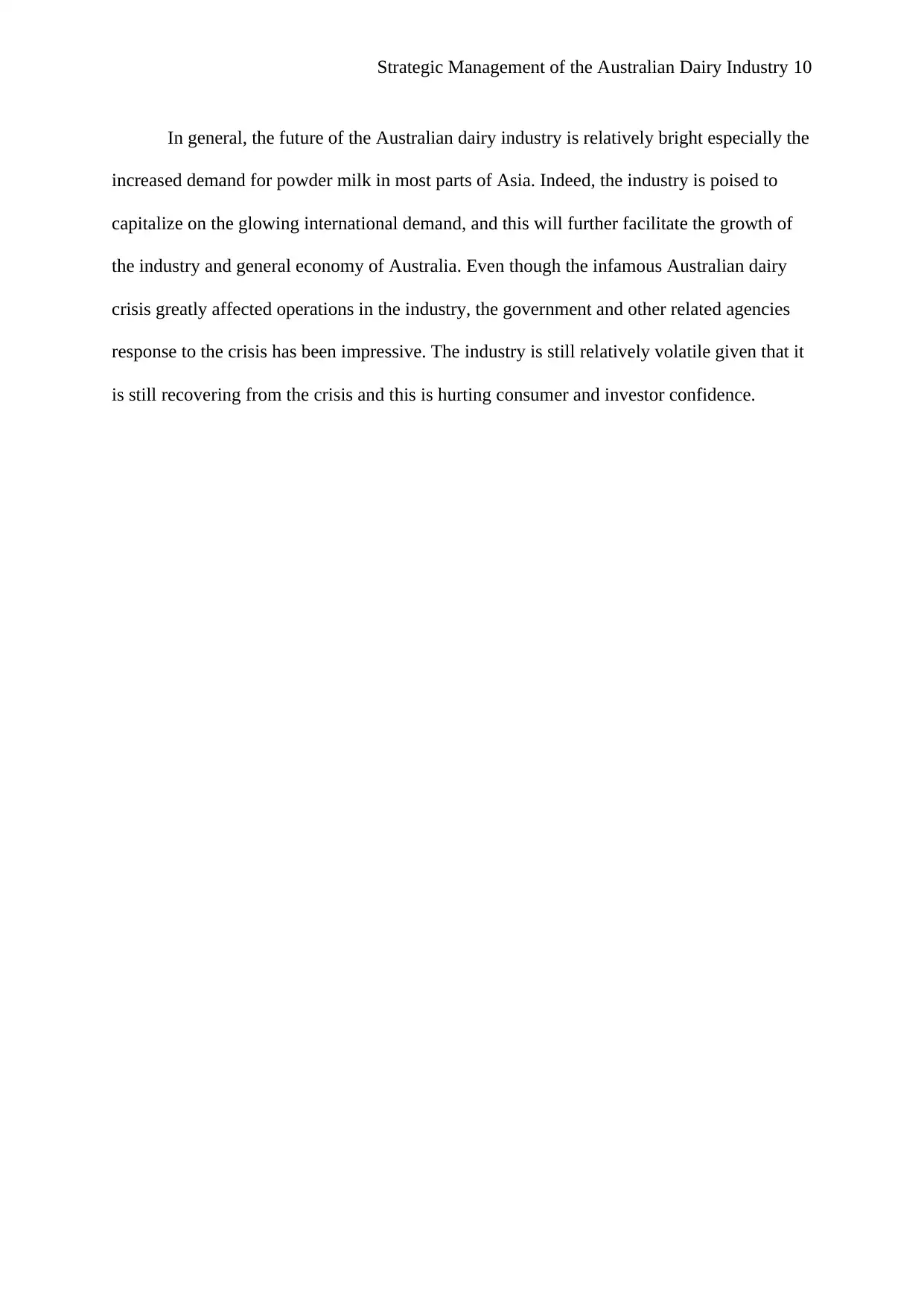

The figure above also shows that the Australian dairy products are majorly exported.

This can be accredited to intense domestic competitions and lower local prices (Nettle,

Brightling and Hope, 2013). However, being a relatively liberal sector, the Australian dairy

industry has for a very long time been able to brace global competitions. This can be

accredited to the country’s efficient production methods and development of strong herd

genetics with comparatively high milk production (McDowell and Nash, 2012).

Therefore, the industry is poised for strong export growth given the increasing

demand for dairy products from some countries in Asia. Australia is currently the third

largest exporter of dairy products after the EU and New Zealand with about 10% global

market share. By country, Australia’s major export destinations include China and Malaysia.

Conclusion

South East Asia 30%

Japan 19%

Other parts of Asia 24%

The figure above also shows that the Australian dairy products are majorly exported.

This can be accredited to intense domestic competitions and lower local prices (Nettle,

Brightling and Hope, 2013). However, being a relatively liberal sector, the Australian dairy

industry has for a very long time been able to brace global competitions. This can be

accredited to the country’s efficient production methods and development of strong herd

genetics with comparatively high milk production (McDowell and Nash, 2012).

Therefore, the industry is poised for strong export growth given the increasing

demand for dairy products from some countries in Asia. Australia is currently the third

largest exporter of dairy products after the EU and New Zealand with about 10% global

market share. By country, Australia’s major export destinations include China and Malaysia.

Conclusion

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 10

In general, the future of the Australian dairy industry is relatively bright especially the

increased demand for powder milk in most parts of Asia. Indeed, the industry is poised to

capitalize on the glowing international demand, and this will further facilitate the growth of

the industry and general economy of Australia. Even though the infamous Australian dairy

crisis greatly affected operations in the industry, the government and other related agencies

response to the crisis has been impressive. The industry is still relatively volatile given that it

is still recovering from the crisis and this is hurting consumer and investor confidence.

In general, the future of the Australian dairy industry is relatively bright especially the

increased demand for powder milk in most parts of Asia. Indeed, the industry is poised to

capitalize on the glowing international demand, and this will further facilitate the growth of

the industry and general economy of Australia. Even though the infamous Australian dairy

crisis greatly affected operations in the industry, the government and other related agencies

response to the crisis has been impressive. The industry is still relatively volatile given that it

is still recovering from the crisis and this is hurting consumer and investor confidence.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 11

References

Arvanitoyannis, I.S. (2010) Waste management for the food industries. Academic Press.

Bardsley, D.K. and Pech, P. (2012) ‘Defining spaces of resilience within the neoliberal

paradigm: could French land use classifications guide support for risk management within an

Australian regional context?,’ Human ecology, 40(1), pp.129-143.

Buys, L., Mengersen, K., Johnson, S., van Buuren, N. and Chauvin, A. (2014) ‘Creating a

Sustainability Scorecard as a predictive tool for measuring the complex social, economic and

environmental impacts of industries, a case study: Assessing the viability and sustainability

of the dairy industry,’ Journal of environmental management, 133, pp.184-192.

Cary, J. and Roberts, A. (2011) ‘The limitations of environmental management systems in

Australian agriculture,’ Journal of Environmental Management, 92(3), pp.878-885.

Chapman, D.F., Hill, J., Tharmaraj, J., Beca, D., Kenny, S.N. and Jacobs, J.L. (2014)

‘Increasing home-grown forage consumption and profit in non-irrigated dairy systems. 1.

Rationale, systems design and management,’ Animal Production Science, 54(3), pp.221-233.

Chapman, D.F., Kenny, S.N. and Lane, N. (2011) ‘Pasture and forage crop systems for non-

irrigated dairy farms in southern Australia: 3. Estimated economic value of additional home-

grown feed,’ Agricultural Systems, 104(8), pp.589-599.

Cuganesan, S., Guthrie, J. and Ward, L. (2010) ‘Examining CSR disclosure strategies within

the Australian food and beverage industry,’ In Accounting Forum (Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 169-

183). Elsevier.

Gourley, C.J., Dougherty, W.J., Weaver, D.M., Aarons, S.R., Awty, I.M., Gibson, D.M.,

Hannah, M.C., Smith, A.P. and Peverill, K.I. (2012) ‘Farm-scale nitrogen, phosphorus,

potassium and sulfur balances and use efficiencies on Australian dairy farms,’ Animal

Production Science, 52(10), pp.929-944.

References

Arvanitoyannis, I.S. (2010) Waste management for the food industries. Academic Press.

Bardsley, D.K. and Pech, P. (2012) ‘Defining spaces of resilience within the neoliberal

paradigm: could French land use classifications guide support for risk management within an

Australian regional context?,’ Human ecology, 40(1), pp.129-143.

Buys, L., Mengersen, K., Johnson, S., van Buuren, N. and Chauvin, A. (2014) ‘Creating a

Sustainability Scorecard as a predictive tool for measuring the complex social, economic and

environmental impacts of industries, a case study: Assessing the viability and sustainability

of the dairy industry,’ Journal of environmental management, 133, pp.184-192.

Cary, J. and Roberts, A. (2011) ‘The limitations of environmental management systems in

Australian agriculture,’ Journal of Environmental Management, 92(3), pp.878-885.

Chapman, D.F., Hill, J., Tharmaraj, J., Beca, D., Kenny, S.N. and Jacobs, J.L. (2014)

‘Increasing home-grown forage consumption and profit in non-irrigated dairy systems. 1.

Rationale, systems design and management,’ Animal Production Science, 54(3), pp.221-233.

Chapman, D.F., Kenny, S.N. and Lane, N. (2011) ‘Pasture and forage crop systems for non-

irrigated dairy farms in southern Australia: 3. Estimated economic value of additional home-

grown feed,’ Agricultural Systems, 104(8), pp.589-599.

Cuganesan, S., Guthrie, J. and Ward, L. (2010) ‘Examining CSR disclosure strategies within

the Australian food and beverage industry,’ In Accounting Forum (Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 169-

183). Elsevier.

Gourley, C.J., Dougherty, W.J., Weaver, D.M., Aarons, S.R., Awty, I.M., Gibson, D.M.,

Hannah, M.C., Smith, A.P. and Peverill, K.I. (2012) ‘Farm-scale nitrogen, phosphorus,

potassium and sulfur balances and use efficiencies on Australian dairy farms,’ Animal

Production Science, 52(10), pp.929-944.

Strategic Management of the Australian Dairy Industry 12

Henry, B., Charmley, E., Eckard, R., Gaughan, J.B. and Hegarty, R. (2012) ‘Livestock

production in a changing climate: adaptation and mitigation research in Australia,’ Crop and

Pasture Science, 63(3), pp.191-202.

Kaine, G. and Cowan, L. (2011) ‘Using general systems theory to understand how farmers

manage variability,’ Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 28(3), pp.231-244.

Klerkx, L. and Nettle, R. (2013) ‘Achievements and challenges of innovation co-production

support initiatives in the Australian and Dutch dairy sectors: a comparative study,’ Food

Policy, 40, pp.74-89.

Lee, J.M., Matthew, C., Thom, E.R. and Chapman, D.F. (2012) ‘Perennial ryegrass breeding

in New Zealand: a dairy industry perspective,’ Crop and Pasture Science, 63(2), pp.107-127.

Massoud, M.A., Fayad, R., El-Fadel, M. and Kamleh, R. (2010) ‘Drivers, barriers and

incentives to implementing environmental management systems in the food industry: A case

of Lebanon,’ Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(3), pp.200-209.

McDowell, R.W. and Nash, D. (2012) ‘A review of the cost-effectiveness and suitability of

mitigation strategies to prevent phosphorus loss from dairy farms in New Zealand and

Australia,’ Journal of Environmental Quality, 41(3), pp.680-693.

McLachlan, R. (2013) ‘Deep and Persistent Disadvantage in Australia-Productivity

Commission Staff Working Paper,’

Nettle, R., Brightling, P. and Hope, A. (2013) ‘How programme teams progress agricultural

innovation in the Australian dairy industry,’ The Journal of Agricultural Education and

Extension, 19(3), pp.271-290.

Nettle, R., Paine, M. and Penry, J. (2010) ‘Aligning farm decision making and genetic

information systems to improve animal production: methodology and findings from the

Australian dairy industry,’ Animal Production Science, 50(6), pp.429-434.

Henry, B., Charmley, E., Eckard, R., Gaughan, J.B. and Hegarty, R. (2012) ‘Livestock

production in a changing climate: adaptation and mitigation research in Australia,’ Crop and

Pasture Science, 63(3), pp.191-202.

Kaine, G. and Cowan, L. (2011) ‘Using general systems theory to understand how farmers

manage variability,’ Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 28(3), pp.231-244.

Klerkx, L. and Nettle, R. (2013) ‘Achievements and challenges of innovation co-production

support initiatives in the Australian and Dutch dairy sectors: a comparative study,’ Food

Policy, 40, pp.74-89.

Lee, J.M., Matthew, C., Thom, E.R. and Chapman, D.F. (2012) ‘Perennial ryegrass breeding

in New Zealand: a dairy industry perspective,’ Crop and Pasture Science, 63(2), pp.107-127.

Massoud, M.A., Fayad, R., El-Fadel, M. and Kamleh, R. (2010) ‘Drivers, barriers and

incentives to implementing environmental management systems in the food industry: A case

of Lebanon,’ Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(3), pp.200-209.

McDowell, R.W. and Nash, D. (2012) ‘A review of the cost-effectiveness and suitability of

mitigation strategies to prevent phosphorus loss from dairy farms in New Zealand and

Australia,’ Journal of Environmental Quality, 41(3), pp.680-693.

McLachlan, R. (2013) ‘Deep and Persistent Disadvantage in Australia-Productivity

Commission Staff Working Paper,’

Nettle, R., Brightling, P. and Hope, A. (2013) ‘How programme teams progress agricultural

innovation in the Australian dairy industry,’ The Journal of Agricultural Education and

Extension, 19(3), pp.271-290.

Nettle, R., Paine, M. and Penry, J. (2010) ‘Aligning farm decision making and genetic

information systems to improve animal production: methodology and findings from the

Australian dairy industry,’ Animal Production Science, 50(6), pp.429-434.

1 out of 12

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.