Tax Avoidance and Evasion Strategies

VerifiedAdded on 2020/02/18

|12

|3257

|64

AI Summary

This assignment delves into the complexities of tax avoidance and evasion. It examines different strategies employed by individuals and businesses to minimize their tax liabilities legally. The discussion encompasses relevant case studies, legislation, and international accounting standards. Furthermore, it explores the blurred lines between tax avoidance and evasion, highlighting the ethical implications associated with these practices.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 1

TAXATION THEORY, PRACTICE, AND LAW

Student’s Name

Name of the Course

Professor’s Name

Name of the University

City

Date

TAXATION THEORY, PRACTICE, AND LAW

Student’s Name

Name of the Course

Professor’s Name

Name of the University

City

Date

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 2

Question 1

According to the Internal Revenue Service’s (2017) items owned by an individual meant for

personal use or for investment purposes can be thought of as capital assets. Capital assets include

land, buildings, jewellery, household fixtures and furnishings, securities (bonds, equity, mutual

funds, bank deposits, debentures, life insurance) trademarks, vehicles, patents, plants and

machinery (Dave, 2017). Upon the sale of a capital asset, the amount realised from the sale less

the adjusted basis in the asset is either a capital gain or capital loss (Internal Revenue Service,

2017). When the asset is disposed of at an amount greater than the acquisition cost, then a capital

gain is realised, in circumstances where the disposal price is less than the acquisition cost, then a

capital loss arises.

The Australian Taxation Office (2017a) computes net capital gains and net capital losses as

follows

Net Capital Gain = Sum of all Capital Gains realised within the fiscal year (amounts

arising from managed funds and trusts are added here) – Sum

of Capital Losses (net capital losses arising from prior periods is

added to the current capital losses) – Capital Gains arising

from discounts in tax and concessions given to small businesses

Net Capital Loss = Sum of Capital Losses (including losses realised in prior periods) –

Sum of Capital Gains

When computing capital gains and capital losses some factors are taken into considerations.

Capital gains or losses on collectables which include items like paintings and antiques of values

equivalent to or less than $500 are disregarded. Capital losses associated with collectables can

Question 1

According to the Internal Revenue Service’s (2017) items owned by an individual meant for

personal use or for investment purposes can be thought of as capital assets. Capital assets include

land, buildings, jewellery, household fixtures and furnishings, securities (bonds, equity, mutual

funds, bank deposits, debentures, life insurance) trademarks, vehicles, patents, plants and

machinery (Dave, 2017). Upon the sale of a capital asset, the amount realised from the sale less

the adjusted basis in the asset is either a capital gain or capital loss (Internal Revenue Service,

2017). When the asset is disposed of at an amount greater than the acquisition cost, then a capital

gain is realised, in circumstances where the disposal price is less than the acquisition cost, then a

capital loss arises.

The Australian Taxation Office (2017a) computes net capital gains and net capital losses as

follows

Net Capital Gain = Sum of all Capital Gains realised within the fiscal year (amounts

arising from managed funds and trusts are added here) – Sum

of Capital Losses (net capital losses arising from prior periods is

added to the current capital losses) – Capital Gains arising

from discounts in tax and concessions given to small businesses

Net Capital Loss = Sum of Capital Losses (including losses realised in prior periods) –

Sum of Capital Gains

When computing capital gains and capital losses some factors are taken into considerations.

Capital gains or losses on collectables which include items like paintings and antiques of values

equivalent to or less than $500 are disregarded. Capital losses associated with collectables can

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 3

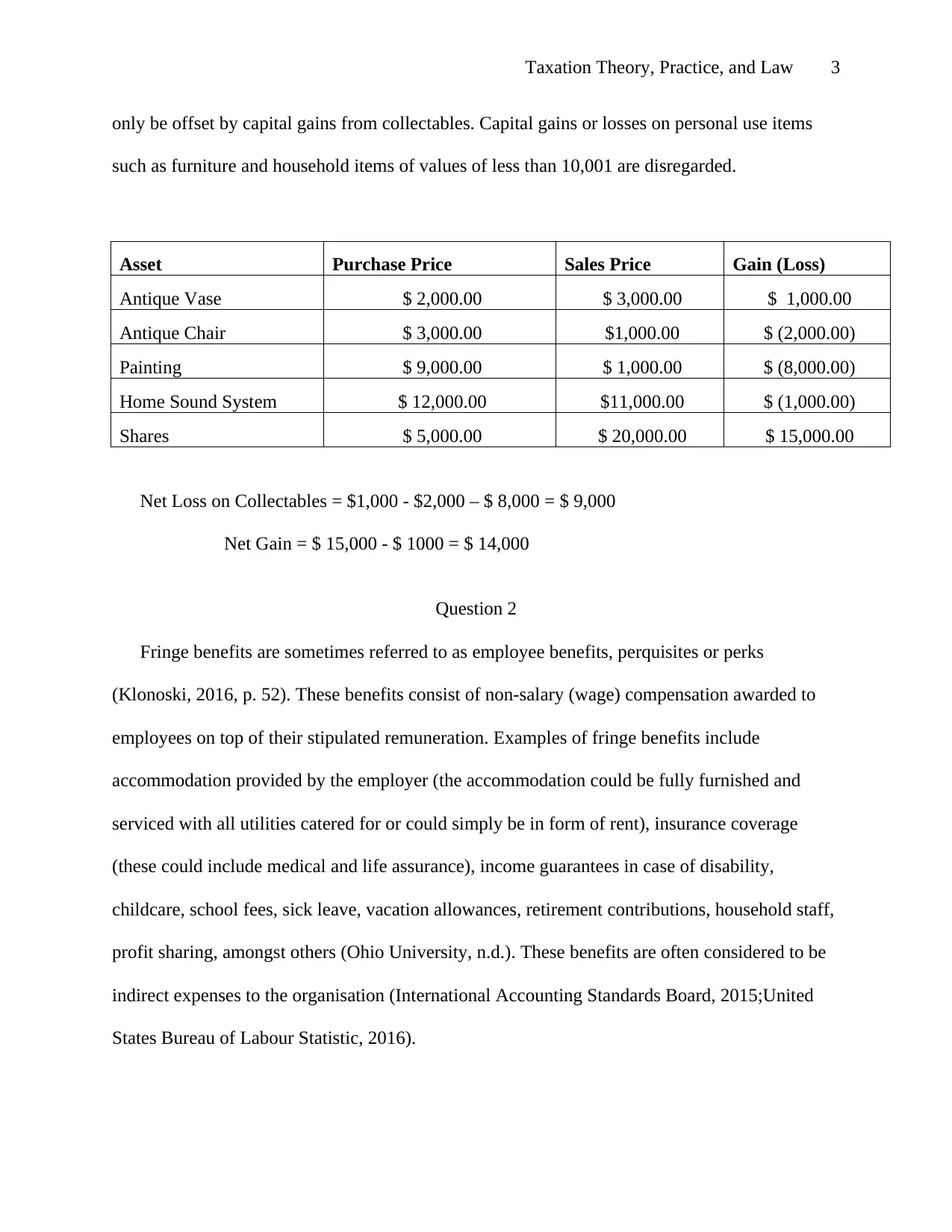

only be offset by capital gains from collectables. Capital gains or losses on personal use items

such as furniture and household items of values of less than 10,001 are disregarded.

Asset Purchase Price Sales Price Gain (Loss)

Antique Vase $ 2,000.00 $ 3,000.00 $ 1,000.00

Antique Chair $ 3,000.00 $1,000.00 $ (2,000.00)

Painting $ 9,000.00 $ 1,000.00 $ (8,000.00)

Home Sound System $ 12,000.00 $11,000.00 $ (1,000.00)

Shares $ 5,000.00 $ 20,000.00 $ 15,000.00

Net Loss on Collectables = $1,000 - $2,000 – $ 8,000 = $ 9,000

Net Gain = $ 15,000 - $ 1000 = $ 14,000

Question 2

Fringe benefits are sometimes referred to as employee benefits, perquisites or perks

(Klonoski, 2016, p. 52). These benefits consist of non-salary (wage) compensation awarded to

employees on top of their stipulated remuneration. Examples of fringe benefits include

accommodation provided by the employer (the accommodation could be fully furnished and

serviced with all utilities catered for or could simply be in form of rent), insurance coverage

(these could include medical and life assurance), income guarantees in case of disability,

childcare, school fees, sick leave, vacation allowances, retirement contributions, household staff,

profit sharing, amongst others (Ohio University, n.d.). These benefits are often considered to be

indirect expenses to the organisation (International Accounting Standards Board, 2015;United

States Bureau of Labour Statistic, 2016).

only be offset by capital gains from collectables. Capital gains or losses on personal use items

such as furniture and household items of values of less than 10,001 are disregarded.

Asset Purchase Price Sales Price Gain (Loss)

Antique Vase $ 2,000.00 $ 3,000.00 $ 1,000.00

Antique Chair $ 3,000.00 $1,000.00 $ (2,000.00)

Painting $ 9,000.00 $ 1,000.00 $ (8,000.00)

Home Sound System $ 12,000.00 $11,000.00 $ (1,000.00)

Shares $ 5,000.00 $ 20,000.00 $ 15,000.00

Net Loss on Collectables = $1,000 - $2,000 – $ 8,000 = $ 9,000

Net Gain = $ 15,000 - $ 1000 = $ 14,000

Question 2

Fringe benefits are sometimes referred to as employee benefits, perquisites or perks

(Klonoski, 2016, p. 52). These benefits consist of non-salary (wage) compensation awarded to

employees on top of their stipulated remuneration. Examples of fringe benefits include

accommodation provided by the employer (the accommodation could be fully furnished and

serviced with all utilities catered for or could simply be in form of rent), insurance coverage

(these could include medical and life assurance), income guarantees in case of disability,

childcare, school fees, sick leave, vacation allowances, retirement contributions, household staff,

profit sharing, amongst others (Ohio University, n.d.). These benefits are often considered to be

indirect expenses to the organisation (International Accounting Standards Board, 2015;United

States Bureau of Labour Statistic, 2016).

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 4

According to the Austrian Tax Office (2017b), the taxes on these fringe benefits are paid by

the employer. As such the employer withholds tax obligations that arise from benefits conferred

to the company’s directors, current employees, potential employees, and past employees. An

employer for purposes of taxes includes sole traders, partnerships, corporations, unincorporated

organisations, governments, non-government organisations, and trustees. The fringe benefits tax

is payable irrespective of whether or not the employee is liable to pay other categories of taxes.

The term loan encompasses situations whereby the employee owes the employer a given

amount and on the day the debt falls due the employee fails to retire the debt. The amount that

remains unpaid is considered as a loan. The loan advanced to Brain can be considered as a loan

fringe benefit. A loan fringe benefit is defined as a loan provided by the employer to the

employee at an interest-free rate or a low-interest rate (this is a rate that is lower than the

benchmark rate) [Inland Revenue, 2016]. In Australia, instead of the market rate of interest, the

statutory interest rate determined by the Reserve Bank of Australia is used as the benchmark rate.

In April 2016, the published rate was 5.65% (Australia Tax Office, 2017b). The value of the

loan fringe benefit that is taxable on the loan given to Brain is calculated as follows:

Step 1: Computation of value of the loan fringe benefits that is taxable without consideration

of the deductible rule

Value of Loan Fringe Benefit that is Taxable = Benchmark (Statutory) interest on the

loan – Actual interest charged on

the loan

Statutory Interest on the Loan = 5.65% x $ 1,000, 000 = $ 56,500

Actual Interest Paid on Loan = 1% x $ 1,000, 000 = $ 10,000

Value of Loan Fringe Benefit that is Taxable = $ 56,500 -$ 10,000 = $ 46,500

According to the Austrian Tax Office (2017b), the taxes on these fringe benefits are paid by

the employer. As such the employer withholds tax obligations that arise from benefits conferred

to the company’s directors, current employees, potential employees, and past employees. An

employer for purposes of taxes includes sole traders, partnerships, corporations, unincorporated

organisations, governments, non-government organisations, and trustees. The fringe benefits tax

is payable irrespective of whether or not the employee is liable to pay other categories of taxes.

The term loan encompasses situations whereby the employee owes the employer a given

amount and on the day the debt falls due the employee fails to retire the debt. The amount that

remains unpaid is considered as a loan. The loan advanced to Brain can be considered as a loan

fringe benefit. A loan fringe benefit is defined as a loan provided by the employer to the

employee at an interest-free rate or a low-interest rate (this is a rate that is lower than the

benchmark rate) [Inland Revenue, 2016]. In Australia, instead of the market rate of interest, the

statutory interest rate determined by the Reserve Bank of Australia is used as the benchmark rate.

In April 2016, the published rate was 5.65% (Australia Tax Office, 2017b). The value of the

loan fringe benefit that is taxable on the loan given to Brain is calculated as follows:

Step 1: Computation of value of the loan fringe benefits that is taxable without consideration

of the deductible rule

Value of Loan Fringe Benefit that is Taxable = Benchmark (Statutory) interest on the

loan – Actual interest charged on

the loan

Statutory Interest on the Loan = 5.65% x $ 1,000, 000 = $ 56,500

Actual Interest Paid on Loan = 1% x $ 1,000, 000 = $ 10,000

Value of Loan Fringe Benefit that is Taxable = $ 56,500 -$ 10,000 = $ 46,500

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 5

Step 2: Computation of Value of Loan Fringe Benefit that is Taxable with consideration of the

deductible rule

According to taxation laws, the employee is entitled to a deduction on the interest charged on

the part of the debt that is used to generate income. Thus Brian gets a deduction for the 40%

used for income producing purposes. The computations are given as follows:

Income Tax Deductible to Employee at Statutory Rate = (5.65% x $ 1,000, 000) 40% = $ 22,600

Income Tax Deductible to Employee at Actual Interest Rate = (1% x $ 1,000,000)40% = $ 4,000

Value of Loan Fringe Benefit that is Taxable may be reduced by = $ 22, 600 - $ 4,000

= $ 18, 600

Value of Loan Fringe Benefit that is Taxable with consideration of the deductible rule =

$ 46,500 - $18,600 = $ 27,900

According to the provisions of tax regulations where an employee under the terms and

conditions of the loan is allowed to make interest payments less frequently than every six

months, the employee is considered at the end of every six months as having been loaned

separately at a nil rate of interest any amount that remains unpaid (Australian Taxation Office,

2017b). Therefore, if Brain pays the interest at the end of three years, it will be assumed that the

rate of interest was nil. Therefore, the taxable value of loan fringe benefit will increase.

Taxable Value of Debt Waiver Fringe Benefits

A debt waiver fringe benefit occurs in situations where the employer releases the employee

from the requirement to repay or reimburse the money lent. In situations where the debt is

waived for reasons of default and the amount cannot be recovered, there is no debt waiver fringe

benefit (Australia Taxation Office, 2017a). In certain situations, the employer can voluntarily

release the employee from the obligation to repay the loan. In such a situation, if the employer is

Step 2: Computation of Value of Loan Fringe Benefit that is Taxable with consideration of the

deductible rule

According to taxation laws, the employee is entitled to a deduction on the interest charged on

the part of the debt that is used to generate income. Thus Brian gets a deduction for the 40%

used for income producing purposes. The computations are given as follows:

Income Tax Deductible to Employee at Statutory Rate = (5.65% x $ 1,000, 000) 40% = $ 22,600

Income Tax Deductible to Employee at Actual Interest Rate = (1% x $ 1,000,000)40% = $ 4,000

Value of Loan Fringe Benefit that is Taxable may be reduced by = $ 22, 600 - $ 4,000

= $ 18, 600

Value of Loan Fringe Benefit that is Taxable with consideration of the deductible rule =

$ 46,500 - $18,600 = $ 27,900

According to the provisions of tax regulations where an employee under the terms and

conditions of the loan is allowed to make interest payments less frequently than every six

months, the employee is considered at the end of every six months as having been loaned

separately at a nil rate of interest any amount that remains unpaid (Australian Taxation Office,

2017b). Therefore, if Brain pays the interest at the end of three years, it will be assumed that the

rate of interest was nil. Therefore, the taxable value of loan fringe benefit will increase.

Taxable Value of Debt Waiver Fringe Benefits

A debt waiver fringe benefit occurs in situations where the employer releases the employee

from the requirement to repay or reimburse the money lent. In situations where the debt is

waived for reasons of default and the amount cannot be recovered, there is no debt waiver fringe

benefit (Australia Taxation Office, 2017a). In certain situations, the employer can voluntarily

release the employee from the obligation to repay the loan. In such a situation, if the employer is

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 6

able to demonstrate that the release was unrelated to the employment relationship, then a debt

waiver fringe benefit does not arise (Australia Taxation Office, 2017b).

The taxable value of the debt waiver fringe benefit is the total sum that is waived. If the bank

decided not to charge Brain interest on the loan a taxable waiver of fringe benefit would arise.

This is computed as follows:

Taxable Value of the Debt Waiver Fringe Benefit = 1% x $ 1,000, 000 x 3years

= $ 30,000

Question 3

A joint tenancy occurs where two or more persons pool their resources together and use

them to purchase property (Find Law Team, 2017). In a joint tenancy there are no severable

shares. For example for a married couple such as Jack and Jill if one person dies, then the

remaining spouse will receive all the rights of survivorship. The joint tenancy has four

characteristics

(i) Joint Ownership – every entity in the joint tenancy arrangement has the right to

every aspect of the property. There are no individual rights not just individually

(ii) Joint Interest – Every individual in the joint tenancy agreement has similar

interest and rights in the property of the same nature and to the same extent.

(iii) Same Point in Time – All the rights and interest of the tenants are vested at the

same point in time

(iv) Unity of Title – all the rights and duties are based on the same deed.

For taxation purposes in joint tenancy, all the parties in the agreement hold an equal interest

in the property (Australia Taxation Office, 2017c). As such the agreement between Jack and Jill

able to demonstrate that the release was unrelated to the employment relationship, then a debt

waiver fringe benefit does not arise (Australia Taxation Office, 2017b).

The taxable value of the debt waiver fringe benefit is the total sum that is waived. If the bank

decided not to charge Brain interest on the loan a taxable waiver of fringe benefit would arise.

This is computed as follows:

Taxable Value of the Debt Waiver Fringe Benefit = 1% x $ 1,000, 000 x 3years

= $ 30,000

Question 3

A joint tenancy occurs where two or more persons pool their resources together and use

them to purchase property (Find Law Team, 2017). In a joint tenancy there are no severable

shares. For example for a married couple such as Jack and Jill if one person dies, then the

remaining spouse will receive all the rights of survivorship. The joint tenancy has four

characteristics

(i) Joint Ownership – every entity in the joint tenancy arrangement has the right to

every aspect of the property. There are no individual rights not just individually

(ii) Joint Interest – Every individual in the joint tenancy agreement has similar

interest and rights in the property of the same nature and to the same extent.

(iii) Same Point in Time – All the rights and interest of the tenants are vested at the

same point in time

(iv) Unity of Title – all the rights and duties are based on the same deed.

For taxation purposes in joint tenancy, all the parties in the agreement hold an equal interest

in the property (Australia Taxation Office, 2017c). As such the agreement between Jack and Jill

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 7

to divide the rental income and rental losses in proportions that are not equal has no effect for

income tax purposes. Jack and Jill must thus include half of the net loss in their taxable incomes.

For purposes of computing capital gains or capital loss tax, the joint tenants are considered to

be tenants in common which means that they have an equal interest in the asset. Therefore, both

Jack and Jill have an equal share in the capital loss or gain when the capital gains tax is being

computed. When the property is sold the capital loss or gain is split equally between them.

Question 4

The case of Inland Revenue Commissioners v. Duke of Westminster [1936] commonly

referred to as the Duke of Westminster case is often cited as an example of tax avoidance.

During the court proceedings, it was established that the Duke of Westminster hired a gardener

who was paid from the Duke’s immense post-tax income. In order to reduce his tax liability, the

Duke instead of paying the gardener a wage wrote a covenant stipulating that he would pay the

gardener an amount equal to the wage that he had previously paid. The tax laws and regulations

that prevailed at that time allowed the Duke to claim a deduction on his taxable income for the

amount paid in the covenant. Overall, the actions of the Duke reduced his income tax and surtax

liability. However, the Inland Revenue Commissioner maintained that the computations and acts

of the Duke of Westminster were nothing more than tax evasion. The court ruled in the favour of

the Duke. In the judgement, Lord Tomlin held that

Every man is entitled if he can to arrange his affairs so that the tax attaching

under the appropriate Acts is less than it otherwise would be. If he

succeeds in ordering them so as to secure that result, then, however

unappreciative the Commissioners of Inland Revenue or his fellow

taxpayers may be of his ingenuity, he cannot be compelled to pay an

to divide the rental income and rental losses in proportions that are not equal has no effect for

income tax purposes. Jack and Jill must thus include half of the net loss in their taxable incomes.

For purposes of computing capital gains or capital loss tax, the joint tenants are considered to

be tenants in common which means that they have an equal interest in the asset. Therefore, both

Jack and Jill have an equal share in the capital loss or gain when the capital gains tax is being

computed. When the property is sold the capital loss or gain is split equally between them.

Question 4

The case of Inland Revenue Commissioners v. Duke of Westminster [1936] commonly

referred to as the Duke of Westminster case is often cited as an example of tax avoidance.

During the court proceedings, it was established that the Duke of Westminster hired a gardener

who was paid from the Duke’s immense post-tax income. In order to reduce his tax liability, the

Duke instead of paying the gardener a wage wrote a covenant stipulating that he would pay the

gardener an amount equal to the wage that he had previously paid. The tax laws and regulations

that prevailed at that time allowed the Duke to claim a deduction on his taxable income for the

amount paid in the covenant. Overall, the actions of the Duke reduced his income tax and surtax

liability. However, the Inland Revenue Commissioner maintained that the computations and acts

of the Duke of Westminster were nothing more than tax evasion. The court ruled in the favour of

the Duke. In the judgement, Lord Tomlin held that

Every man is entitled if he can to arrange his affairs so that the tax attaching

under the appropriate Acts is less than it otherwise would be. If he

succeeds in ordering them so as to secure that result, then, however

unappreciative the Commissioners of Inland Revenue or his fellow

taxpayers may be of his ingenuity, he cannot be compelled to pay an

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 8

increased tax (Inland Revenue Commissioners v. Duke of Westminster

[1936])

The ruling by Lord Tomlin implies that entities that have tax liabilities may take actions or

make arrangement to reduce their tax burden within the perimeters established by the laws.

Where an entity succeeds in reducing their tax liability and avoid the tax burden, the revenue

authority and the fellow tax payer even thought they feel they are being treated unfairly cannot

force the entity to pay an increased tax which might be the original amount (Steven, 2013, p. 17).

This case established the principle that an individual is entitled to within the legal statute

organise their accounts so as to limit their tax liability (Adams, 2011).

Relevance of Tax Evasion Principle in Australia

From 1915, the Federal Income Tax laws in Australia have contained a general anti-

avoidance provision (Bloom, 2015). The aim of the general anti-avoidance provisions was to

ensure an equitable tax regime in which the individual tax payers was unable to avoid the

payment of full tax liability by use of superficial or contrived arrangements. The provisions

added to the complexity of the tax laws and resulted in increased compliance costs for tax

payers. However, some of the provisions were successfully challenged in court (Bloom, 2015).

Following the raft of ruling against the commissioner, amendments were made to the general

anti-avoidance provisions in 1936 through the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (McLaren, 2008,

pp. 144-151). Part IVA was added to the act in 1981 in order to enhance the anti-avoidance

provisions.

Part IVA allows the Commissioner of Taxation wider discretion on items to include in the

taxpayer’s assessable income (Xynas, 2011, pp. 5-8). The provisions prevented the erosion of the

income tax base and did away with gaps that allowed for non-genuine reductions. These

increased tax (Inland Revenue Commissioners v. Duke of Westminster

[1936])

The ruling by Lord Tomlin implies that entities that have tax liabilities may take actions or

make arrangement to reduce their tax burden within the perimeters established by the laws.

Where an entity succeeds in reducing their tax liability and avoid the tax burden, the revenue

authority and the fellow tax payer even thought they feel they are being treated unfairly cannot

force the entity to pay an increased tax which might be the original amount (Steven, 2013, p. 17).

This case established the principle that an individual is entitled to within the legal statute

organise their accounts so as to limit their tax liability (Adams, 2011).

Relevance of Tax Evasion Principle in Australia

From 1915, the Federal Income Tax laws in Australia have contained a general anti-

avoidance provision (Bloom, 2015). The aim of the general anti-avoidance provisions was to

ensure an equitable tax regime in which the individual tax payers was unable to avoid the

payment of full tax liability by use of superficial or contrived arrangements. The provisions

added to the complexity of the tax laws and resulted in increased compliance costs for tax

payers. However, some of the provisions were successfully challenged in court (Bloom, 2015).

Following the raft of ruling against the commissioner, amendments were made to the general

anti-avoidance provisions in 1936 through the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (McLaren, 2008,

pp. 144-151). Part IVA was added to the act in 1981 in order to enhance the anti-avoidance

provisions.

Part IVA allows the Commissioner of Taxation wider discretion on items to include in the

taxpayer’s assessable income (Xynas, 2011, pp. 5-8). The provisions prevented the erosion of the

income tax base and did away with gaps that allowed for non-genuine reductions. These

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 9

provisions were enhanced by the rulings in FCT v. Spotless Services Ltd [1986] commonly

referred to as the Spotless Case. In that case, the High Court of Australia held that even if the tax

payer is able to prove that a transaction is genuine, that in itself does not provide grounds for tax

avoidance (Xynas, 2011, pp. 5-14). According to the court, a transaction has to make sense,

where the transaction does not make sense without the tax benefit, then Part IVA applies.

The government of Australia has continued to formulate and implement statutes to reduce tax

avoidance while balancing the interests of the government and those of the taxpayers. Thus, the

principles established in the IRC v the Duke of Westminster [1936] is relevant today but the

scope of administration has been reducing.

Question 5

The issue of assessment of taxation for primary production and forestry is given by Taxation

Ruling 95/6 (TR95/6). The aim of the ruling is to indicate the tax burden from the business of

forest operations and the transaction relating to timber by persons in the business of forest

operation and persons not engaged in the business of forest operations but having transactions

involving forestry and/ or timber. The ruling expressly indicates which receipts obtained from

the sale of timber constitute assessable income, whether or not the tax payer’s primary business

is forestry or not (Australian Taxation Office, 2010). According to the ruling, the disposal of

trees by the taxpayer means that the amount realised from the sale of the trees should be added in

the taxpayer’s assessable income as provided for under the Income Tax Act 36(1). Therefore, the

receipts by Bill for the timber are assessed as income and as such result in a tax burden.

According to section 55 of TR 95/6 the accessible income includes: proceeds from the sale of

standing trees, royalties earned in exchange for granting another party the right to fell and

provisions were enhanced by the rulings in FCT v. Spotless Services Ltd [1986] commonly

referred to as the Spotless Case. In that case, the High Court of Australia held that even if the tax

payer is able to prove that a transaction is genuine, that in itself does not provide grounds for tax

avoidance (Xynas, 2011, pp. 5-14). According to the court, a transaction has to make sense,

where the transaction does not make sense without the tax benefit, then Part IVA applies.

The government of Australia has continued to formulate and implement statutes to reduce tax

avoidance while balancing the interests of the government and those of the taxpayers. Thus, the

principles established in the IRC v the Duke of Westminster [1936] is relevant today but the

scope of administration has been reducing.

Question 5

The issue of assessment of taxation for primary production and forestry is given by Taxation

Ruling 95/6 (TR95/6). The aim of the ruling is to indicate the tax burden from the business of

forest operations and the transaction relating to timber by persons in the business of forest

operation and persons not engaged in the business of forest operations but having transactions

involving forestry and/ or timber. The ruling expressly indicates which receipts obtained from

the sale of timber constitute assessable income, whether or not the tax payer’s primary business

is forestry or not (Australian Taxation Office, 2010). According to the ruling, the disposal of

trees by the taxpayer means that the amount realised from the sale of the trees should be added in

the taxpayer’s assessable income as provided for under the Income Tax Act 36(1). Therefore, the

receipts by Bill for the timber are assessed as income and as such result in a tax burden.

According to section 55 of TR 95/6 the accessible income includes: proceeds from the sale of

standing trees, royalties earned in exchange for granting another party the right to fell and

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 10

remove timber, and profits from isolated transactions. The lump sum amount received by Brian

can be considered as a royalty and thus assessable income.

remove timber, and profits from isolated transactions. The lump sum amount received by Brian

can be considered as a royalty and thus assessable income.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 11

References

Adams, J. (2011). What is the difference between tax avoidance and tax evasion? Tax Insider,

Available at https://www.taxinsider.co.uk/680-

What_is_The_Difference_Between_Tax_Avoidance_and_Tax_Evasion.html (Accessed 8

September 2017).

Australian Tax Office (2010). Taxation ruling: TR 95/6. Available at:

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?docid=txr/tr956/nat/ato/00001 (Accessed: 8

September 2017).

Australian Tax Office (2017a.) Working out your net capital gain or loss. Available at:

https://www.ato.gov.au/General/Capital-gains-tax/Working-out-your-capital-gain-or-loss/

Working-out-your-net-capital-gain-or-loss/ (Accessed: 8 September 2017).

Australian Tax Office (2017b). Fringe benefit tax a guide for employers. Available at:

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=SAV%2FFBTGEMP%2F00002 (Accessed

8 September 2017).

Australian Taxation Office (2017c). Co-ownership of rental properties. Available at:

https://www.ato.gov.au/Forms/Rental-properties-2013-14/?page=5 (Accessed 8 September

2017).

Bloom D. (2015) ‘Tax avoidance: A view from the dark side’, Annual Tax Lecture , Melbourne

Law School, 15 August.

Dave, R. (2017) ‘How to calculate short-term and long-term capital gains and tax on these,’

Economic Times, 28 August [Online]. Available at:

conomictimes.indiatimes.com/wealth/tax/how-to-calculate-short-term-and-long-term-capital-

gains-and-tax-on-these/articleshow/60230745.cms (Accessed: 7 September 2017).

Inland Revenue Commissioner v. Duke of Westminster [1936] AC 1 (19 TC 490).

Inland Revenue (2016) Low interest loan and fringe benefit tax. Available at

http://www.ird.govt.nz/fringe-benefit-tax/fbt-types/fbt-low-interest-loans/low-interest-loans-

fbt.html (Accessed 8 September 2017).

International Accounting Standards Board (2015) IAS 19: Employee benefits. Available at:

http://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-19-employee-benefits/ (Accessed 8

September 2017).

Internal Revenue Services (2017) Capital gains and losses. Available at:

https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc409.html (Accessed: 7 September 2017).

Klonoski, R. (2016) ‘Defining Employee Benefits: A Managerial Perspective’, International

Journal of Human Resource Studies, 6(2), pp. 52–72.

References

Adams, J. (2011). What is the difference between tax avoidance and tax evasion? Tax Insider,

Available at https://www.taxinsider.co.uk/680-

What_is_The_Difference_Between_Tax_Avoidance_and_Tax_Evasion.html (Accessed 8

September 2017).

Australian Tax Office (2010). Taxation ruling: TR 95/6. Available at:

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?docid=txr/tr956/nat/ato/00001 (Accessed: 8

September 2017).

Australian Tax Office (2017a.) Working out your net capital gain or loss. Available at:

https://www.ato.gov.au/General/Capital-gains-tax/Working-out-your-capital-gain-or-loss/

Working-out-your-net-capital-gain-or-loss/ (Accessed: 8 September 2017).

Australian Tax Office (2017b). Fringe benefit tax a guide for employers. Available at:

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=SAV%2FFBTGEMP%2F00002 (Accessed

8 September 2017).

Australian Taxation Office (2017c). Co-ownership of rental properties. Available at:

https://www.ato.gov.au/Forms/Rental-properties-2013-14/?page=5 (Accessed 8 September

2017).

Bloom D. (2015) ‘Tax avoidance: A view from the dark side’, Annual Tax Lecture , Melbourne

Law School, 15 August.

Dave, R. (2017) ‘How to calculate short-term and long-term capital gains and tax on these,’

Economic Times, 28 August [Online]. Available at:

conomictimes.indiatimes.com/wealth/tax/how-to-calculate-short-term-and-long-term-capital-

gains-and-tax-on-these/articleshow/60230745.cms (Accessed: 7 September 2017).

Inland Revenue Commissioner v. Duke of Westminster [1936] AC 1 (19 TC 490).

Inland Revenue (2016) Low interest loan and fringe benefit tax. Available at

http://www.ird.govt.nz/fringe-benefit-tax/fbt-types/fbt-low-interest-loans/low-interest-loans-

fbt.html (Accessed 8 September 2017).

International Accounting Standards Board (2015) IAS 19: Employee benefits. Available at:

http://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-19-employee-benefits/ (Accessed 8

September 2017).

Internal Revenue Services (2017) Capital gains and losses. Available at:

https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc409.html (Accessed: 7 September 2017).

Klonoski, R. (2016) ‘Defining Employee Benefits: A Managerial Perspective’, International

Journal of Human Resource Studies, 6(2), pp. 52–72.

Taxation Theory, Practice, and Law 12

Mclaren J. (2008). ‘The distinction between tax avoidance and tax evasion has been blurred in

Australia. Why has it happened?’, Journal of the Australia Tax Teachers Association, 3(2), pp

141-163.

Ohio University (n.d.) 10 benefits business offer employees. Available at:

http://onlinemasters.ohio.edu/10-items-business-offer-infographic/?g=infographics&t=mba

(Accessed 8 September 2017).

FCT v Spotless Services Ltd [1986] 34 ATR 183.

Stevens, P. (2013) ‘The changing limits of acceptable tax avoidance,’ Tax Journal, [Online].

Available at: https://www.taxjournal.com/articles/changing-limits-acceptable-tax-avoidance-

11012013 (Accessed 8 September 2017).

United States Bureau of Labour Statistics (2016) Glossary. Available at:

https://www.bls.gov/bls/glossary.htm#B (Accessed 8 September 2017).

Xynas, L. (2011) ‘Tax planning, avoidance and evasion in Australia 1970-2010: The regulatory

responses and taxpayer compliance’, Revenue Law Journal, 20(1), pp. 1-37.

Mclaren J. (2008). ‘The distinction between tax avoidance and tax evasion has been blurred in

Australia. Why has it happened?’, Journal of the Australia Tax Teachers Association, 3(2), pp

141-163.

Ohio University (n.d.) 10 benefits business offer employees. Available at:

http://onlinemasters.ohio.edu/10-items-business-offer-infographic/?g=infographics&t=mba

(Accessed 8 September 2017).

FCT v Spotless Services Ltd [1986] 34 ATR 183.

Stevens, P. (2013) ‘The changing limits of acceptable tax avoidance,’ Tax Journal, [Online].

Available at: https://www.taxjournal.com/articles/changing-limits-acceptable-tax-avoidance-

11012013 (Accessed 8 September 2017).

United States Bureau of Labour Statistics (2016) Glossary. Available at:

https://www.bls.gov/bls/glossary.htm#B (Accessed 8 September 2017).

Xynas, L. (2011) ‘Tax planning, avoidance and evasion in Australia 1970-2010: The regulatory

responses and taxpayer compliance’, Revenue Law Journal, 20(1), pp. 1-37.

1 out of 12

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.