The Technology Acceptance Model E-Commerce Extension: A Conceptual Framework

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/26

|7

|4165

|62

AI Summary

This study suggests the extension of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) for its application in the E-commerce field. The extended TAM is expected to better explain actual behavior in E-commerce environments than the original TAM.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Procedia Economics and Finance 26 ( 2015 ) 1000 – 1006

2212-5671 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Peer-review under responsibility of Academic World Research and Education Center

doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00922-3

ScienceDirect

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

4th World Conference on Business, Economics and Management, WCBEM

The Technology Acceptance Model E-Commerce Extension: A

Conceptual Framework

Rima Fayada*, David Paperb

aAssistant Professor, Lebanese University, IUT, Saida, Lebanon

bProfessor, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA

Abstract

Electronic-commerce has become an important channel for conducting business. Researchers as well as market executives are

trying to better understand online consumer behavior. One model used by researchers to understand behavior in the information

systems field in general is the technology acceptance model (TAM). The TAM variables are perceived usefulness, perceived ease

of use, and intentions. In this study, we suggest the extension of the TAM for its application in the E-commerce field. The

original TAM will be extended, by adding four predictor variables. The four predictor variables are process satisfaction, outcome

satisfaction, expectations, and E-commerce use. In addition, the TAM will be extended by measuring actual behavior as opposed

to measuring intentions as a substitute for actual behavior in previous TAM application studies. We suggest measuring actual use

variable in terms of four criterion variables, namely, purchase, access number, access total time, and access average time. The

extended TAM is expected to better explain actual behavior in E-commerce environments than the original TAM.

© 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V.

Peer-review under responsibility of Academic World Research and Education Center.

Keywords: Technology Acceptance Model; User Satisfaction; Process Satisfaction; Outcome Satisfaction; Intentions; Actual Behavior;

Behavioral Expectations; E-commerce

* Rima Fayad. Tel.: (961)-71-734473

E-mail address: rima.fayyad@ul.edu.lb

© 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Peer-review under responsibility of Academic World Research and Education Center

2212-5671 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Peer-review under responsibility of Academic World Research and Education Center

doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00922-3

ScienceDirect

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

4th World Conference on Business, Economics and Management, WCBEM

The Technology Acceptance Model E-Commerce Extension: A

Conceptual Framework

Rima Fayada*, David Paperb

aAssistant Professor, Lebanese University, IUT, Saida, Lebanon

bProfessor, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA

Abstract

Electronic-commerce has become an important channel for conducting business. Researchers as well as market executives are

trying to better understand online consumer behavior. One model used by researchers to understand behavior in the information

systems field in general is the technology acceptance model (TAM). The TAM variables are perceived usefulness, perceived ease

of use, and intentions. In this study, we suggest the extension of the TAM for its application in the E-commerce field. The

original TAM will be extended, by adding four predictor variables. The four predictor variables are process satisfaction, outcome

satisfaction, expectations, and E-commerce use. In addition, the TAM will be extended by measuring actual behavior as opposed

to measuring intentions as a substitute for actual behavior in previous TAM application studies. We suggest measuring actual use

variable in terms of four criterion variables, namely, purchase, access number, access total time, and access average time. The

extended TAM is expected to better explain actual behavior in E-commerce environments than the original TAM.

© 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V.

Peer-review under responsibility of Academic World Research and Education Center.

Keywords: Technology Acceptance Model; User Satisfaction; Process Satisfaction; Outcome Satisfaction; Intentions; Actual Behavior;

Behavioral Expectations; E-commerce

* Rima Fayad. Tel.: (961)-71-734473

E-mail address: rima.fayyad@ul.edu.lb

© 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Peer-review under responsibility of Academic World Research and Education Center

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1001Rima Fayad and David Paper / Procedia Economics and Finance 26 ( 2015 ) 1000 – 1006

1. Introduction

Electronic-commerce (E-commerce) is defined as all aspects of business and market processes enabled by the

Internet. E-commerce is rapidly becoming a viable means of condu cting business, as evidenced by the tremendous

amounts of money spent online. The United States online retail sales are estimated to reach $278.9 billion in 2015 as

reported by Forrester Research (Mulpuru, 2011). As a result, the economic impact of E-commerce is increasing

exponentially. Web based companies, Net Enabled Organizations (NEO), and researchers are still trying to

understand and predict online consumer behavior; therefore, research in this area is needed.

Information systems (IS) researchers have explored online con sumer behavior in terms of online shopping

adoption (Bhattacherjee, 2001; Gefen, Karahanna, & Straub, 200 3b; Gefen & Straub, 2000; Koch, Toker, & Brulez,

2011; Koufaris, 2002). The most widely referenced adoption model in IS research is Davis’s (1989) technology

acceptance model (TAM) (Gefen & Straub, 2000). The TAM is an adaptation of the theory of reasoned action

(TRA) (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) for predicting IS adoption (Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw,

1989). The TAM has two elements, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU), that are correlated

with the decision to adopt a new technology (Davis, 1989). Although designed to explain new technology adoption,

not specifically E-commerce behavior, researchers have recently u sed the TAM to explore Internet consumer

behavior (Bhattacherjee, 2001; Gefen et al., 2003; Gefen & Straub, 2000; Koch, et al., 2011; Koufaris, 2002).

We argue that the TAM in its current form cannot be used to fully explain online consumer behavior as E-

commerce adoption is considerably different from new tech nology adoption in an organization. One difference is

that the decision to buy online is voluntary, while the decision to use new software in an organization is typically

mandated by organizational policy. Also, shopping online is one choice among alternatives (e.g. shopping in a

conventional store) for the shopper, while more often than not there is no choice among different software or

systems mandated by an organization. Although the use of the TAM, as it was originally conceived, is not likely to

lead to a full explanation of online consumer behavior, an E-commerce specific, extended TAM may prove useful in

explaining such behavior. Hence, there is a need to extend the TAM to serve as an E-commerce adoption model.

2. Theoretical Background

Before developing our model we examined the published body of knowledge about the topic. Our review and

evaluation of the literature are presented in the following section. Based on that evaluation and grounded in the

literature, our new TAM extending variables are identified.

2.1. The Theory of Reasoned Action

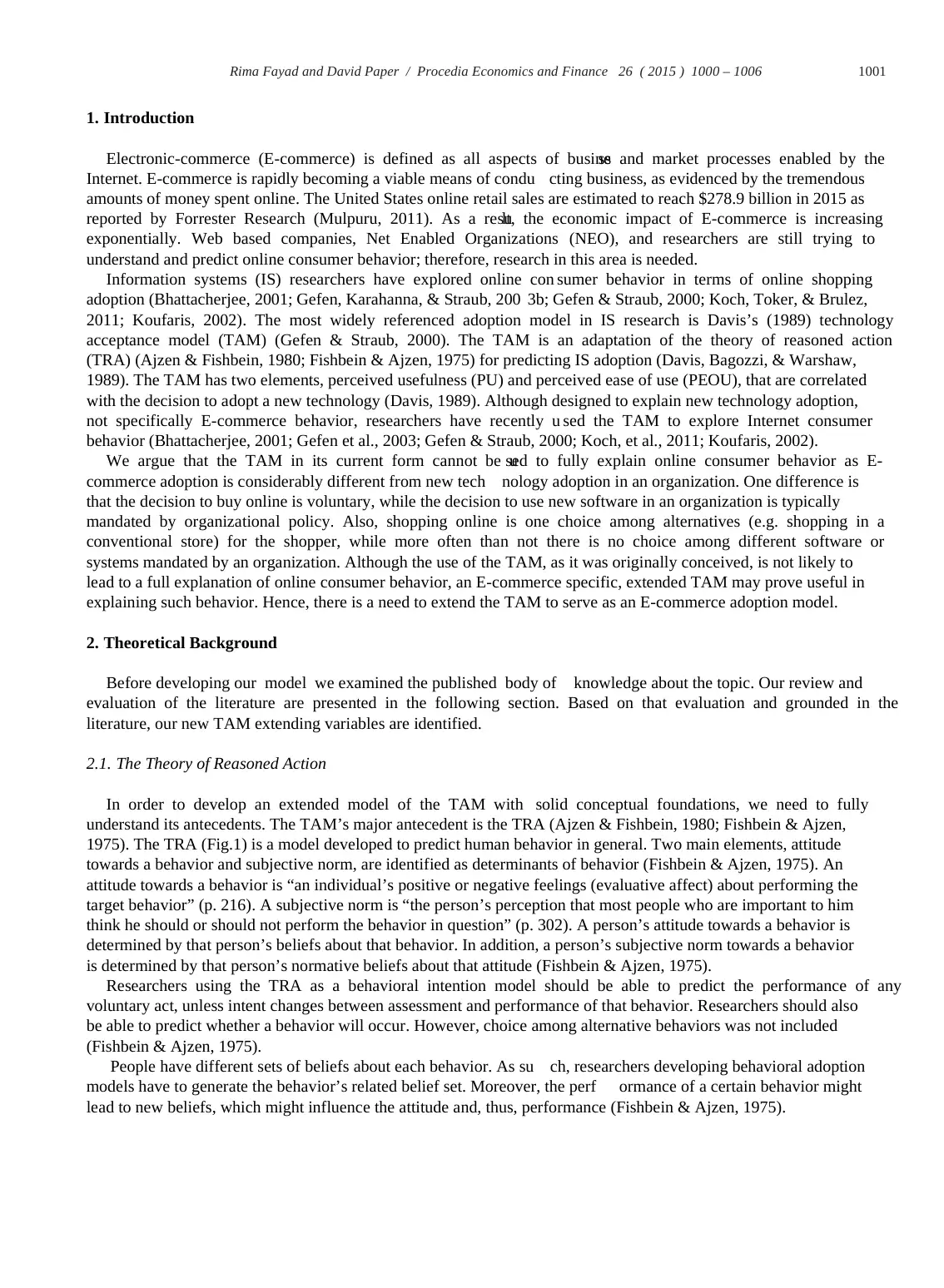

In order to develop an extended model of the TAM with solid conceptual foundations, we need to fully

understand its antecedents. The TAM’s major antecedent is the TRA (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen,

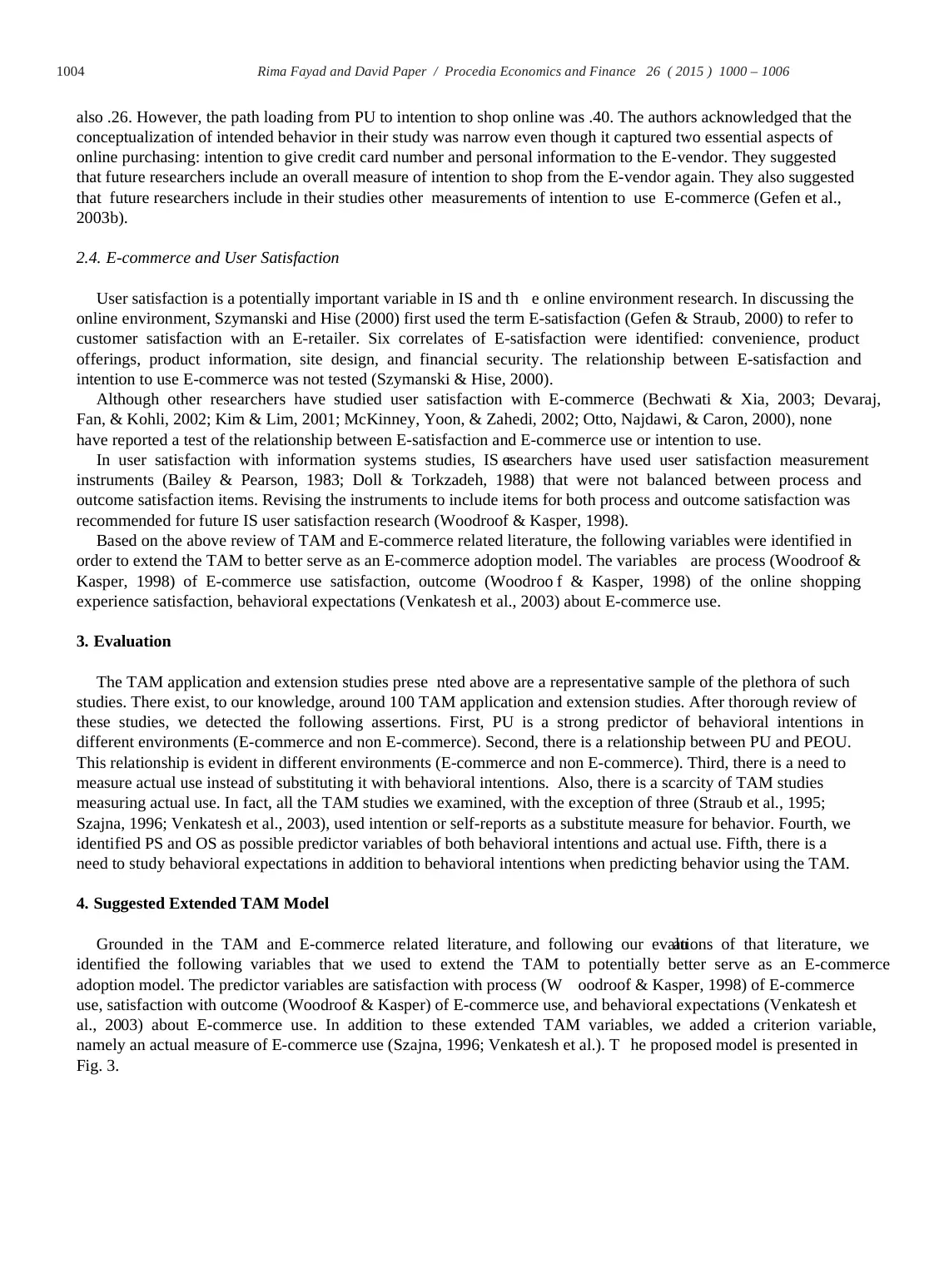

1975). The TRA (Fig.1) is a model developed to predict human behavior in general. Two main elements, attitude

towards a behavior and subjective norm, are identified as determinants of behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). An

attitude towards a behavior is “an individual’s positive or negative feelings (evaluative affect) about performing the

target behavior” (p. 216). A subjective norm is “the person’s perception that most people who are important to him

think he should or should not perform the behavior in question” (p. 302). A person’s attitude towards a behavior is

determined by that person’s beliefs about that behavior. In addition, a person’s subjective norm towards a behavior

is determined by that person’s normative beliefs about that attitude (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

Researchers using the TRA as a behavioral intention model should be able to predict the performance of any

voluntary act, unless intent changes between assessment and performance of that behavior. Researchers should also

be able to predict whether a behavior will occur. However, choice among alternative behaviors was not included

(Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

People have different sets of beliefs about each behavior. As su ch, researchers developing behavioral adoption

models have to generate the behavior’s related belief set. Moreover, the perf ormance of a certain behavior might

lead to new beliefs, which might influence the attitude and, thus, performance (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

1. Introduction

Electronic-commerce (E-commerce) is defined as all aspects of business and market processes enabled by the

Internet. E-commerce is rapidly becoming a viable means of condu cting business, as evidenced by the tremendous

amounts of money spent online. The United States online retail sales are estimated to reach $278.9 billion in 2015 as

reported by Forrester Research (Mulpuru, 2011). As a result, the economic impact of E-commerce is increasing

exponentially. Web based companies, Net Enabled Organizations (NEO), and researchers are still trying to

understand and predict online consumer behavior; therefore, research in this area is needed.

Information systems (IS) researchers have explored online con sumer behavior in terms of online shopping

adoption (Bhattacherjee, 2001; Gefen, Karahanna, & Straub, 200 3b; Gefen & Straub, 2000; Koch, Toker, & Brulez,

2011; Koufaris, 2002). The most widely referenced adoption model in IS research is Davis’s (1989) technology

acceptance model (TAM) (Gefen & Straub, 2000). The TAM is an adaptation of the theory of reasoned action

(TRA) (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) for predicting IS adoption (Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw,

1989). The TAM has two elements, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU), that are correlated

with the decision to adopt a new technology (Davis, 1989). Although designed to explain new technology adoption,

not specifically E-commerce behavior, researchers have recently u sed the TAM to explore Internet consumer

behavior (Bhattacherjee, 2001; Gefen et al., 2003; Gefen & Straub, 2000; Koch, et al., 2011; Koufaris, 2002).

We argue that the TAM in its current form cannot be used to fully explain online consumer behavior as E-

commerce adoption is considerably different from new tech nology adoption in an organization. One difference is

that the decision to buy online is voluntary, while the decision to use new software in an organization is typically

mandated by organizational policy. Also, shopping online is one choice among alternatives (e.g. shopping in a

conventional store) for the shopper, while more often than not there is no choice among different software or

systems mandated by an organization. Although the use of the TAM, as it was originally conceived, is not likely to

lead to a full explanation of online consumer behavior, an E-commerce specific, extended TAM may prove useful in

explaining such behavior. Hence, there is a need to extend the TAM to serve as an E-commerce adoption model.

2. Theoretical Background

Before developing our model we examined the published body of knowledge about the topic. Our review and

evaluation of the literature are presented in the following section. Based on that evaluation and grounded in the

literature, our new TAM extending variables are identified.

2.1. The Theory of Reasoned Action

In order to develop an extended model of the TAM with solid conceptual foundations, we need to fully

understand its antecedents. The TAM’s major antecedent is the TRA (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen,

1975). The TRA (Fig.1) is a model developed to predict human behavior in general. Two main elements, attitude

towards a behavior and subjective norm, are identified as determinants of behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). An

attitude towards a behavior is “an individual’s positive or negative feelings (evaluative affect) about performing the

target behavior” (p. 216). A subjective norm is “the person’s perception that most people who are important to him

think he should or should not perform the behavior in question” (p. 302). A person’s attitude towards a behavior is

determined by that person’s beliefs about that behavior. In addition, a person’s subjective norm towards a behavior

is determined by that person’s normative beliefs about that attitude (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

Researchers using the TRA as a behavioral intention model should be able to predict the performance of any

voluntary act, unless intent changes between assessment and performance of that behavior. Researchers should also

be able to predict whether a behavior will occur. However, choice among alternative behaviors was not included

(Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

People have different sets of beliefs about each behavior. As su ch, researchers developing behavioral adoption

models have to generate the behavior’s related belief set. Moreover, the perf ormance of a certain behavior might

lead to new beliefs, which might influence the attitude and, thus, performance (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

1002 Rima Fayad and David Paper / Procedia Economics and Finance 26 ( 2015 ) 1000 – 1006

Fig. 1. The Theory of Reasoned Action

A meta-analysis of past TRA research was conducted by Sheppard, Hartwick, and Warshaw (1988) to investigate

the relationship between intention to perform a behavior and the actual behavior. The research reports on the TRA

were published in the Journal of Consumer Research, the Journal of Marketing, the Journal of Marketing Research,

Advances in Consumer Research, the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the Journal of Experimental

Social Psychology, the Journal of Social Psychology, the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, and the Journal of

Applied Psychology prior to 1987. Studies were rejected if the authors had failed to measure all the variables in the

TRA, or did not include bivariate/multivariate correlation, or did not use measures that corresponded with the

behavior/intention that was studied. Sheppard and his associates reported that the TRA was effective in predicting

different behaviors (e.g., study a few hours, go to a weekend job, or write a letter). The frequency-weighted-average

correlation was 0.53 for the intention/behavior relationship, and 0.66 for the (attitudes and subjective

norm)/intention. They also reported that behavior was predicted using the TRA even in situations that fell outside

the boundary conditions set for the model (e.g., behavior involving an explicit choice among alternatives) (Sheppard

et al.). Thus, the robustness of the TRA was established.

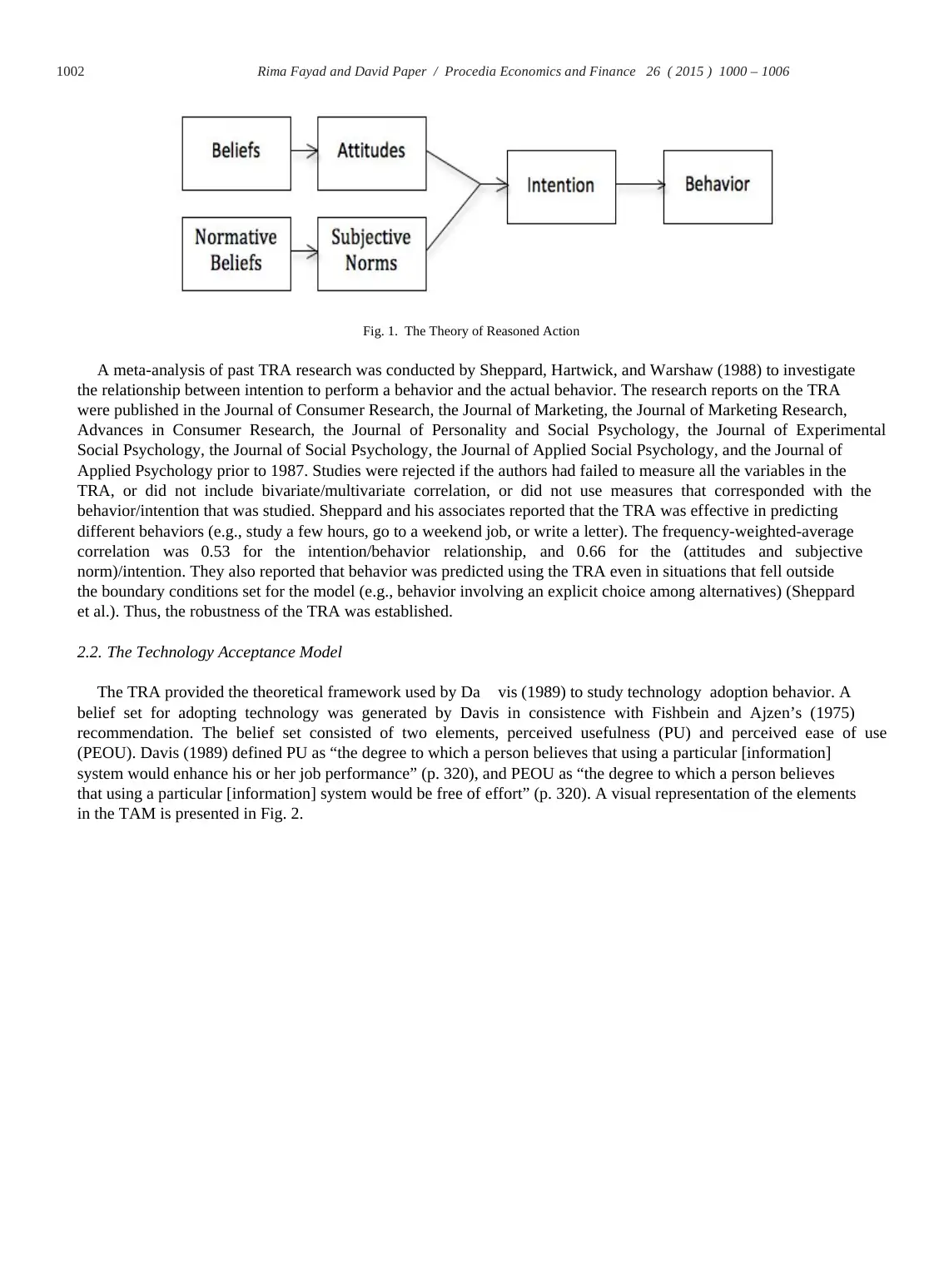

2.2. The Technology Acceptance Model

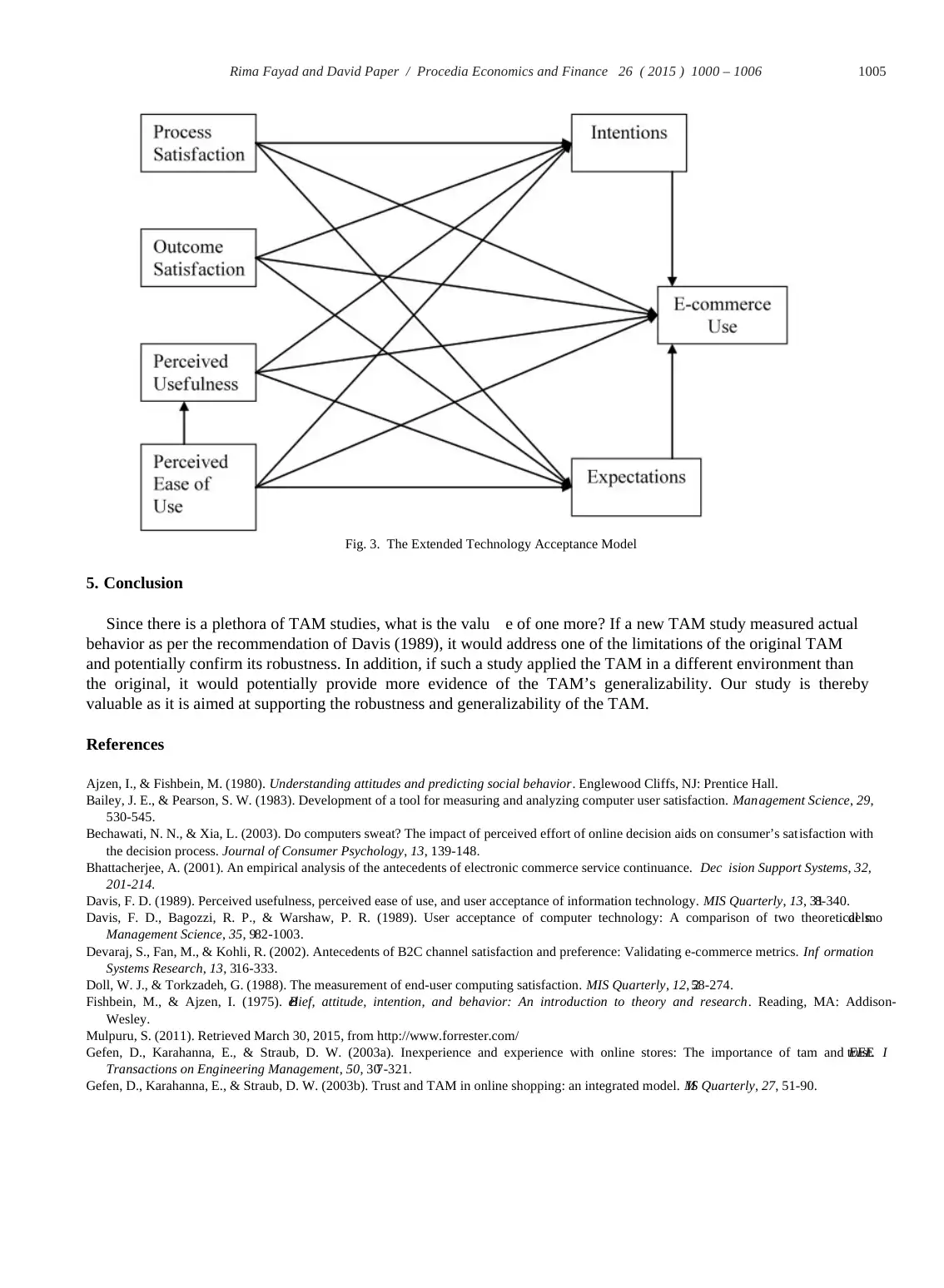

The TRA provided the theoretical framework used by Da vis (1989) to study technology adoption behavior. A

belief set for adopting technology was generated by Davis in consistence with Fishbein and Ajzen’s (1975)

recommendation. The belief set consisted of two elements, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use

(PEOU). Davis (1989) defined PU as “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular [information]

system would enhance his or her job performance” (p. 320), and PEOU as “the degree to which a person believes

that using a particular [information] system would be free of effort” (p. 320). A visual representation of the elements

in the TAM is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1. The Theory of Reasoned Action

A meta-analysis of past TRA research was conducted by Sheppard, Hartwick, and Warshaw (1988) to investigate

the relationship between intention to perform a behavior and the actual behavior. The research reports on the TRA

were published in the Journal of Consumer Research, the Journal of Marketing, the Journal of Marketing Research,

Advances in Consumer Research, the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the Journal of Experimental

Social Psychology, the Journal of Social Psychology, the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, and the Journal of

Applied Psychology prior to 1987. Studies were rejected if the authors had failed to measure all the variables in the

TRA, or did not include bivariate/multivariate correlation, or did not use measures that corresponded with the

behavior/intention that was studied. Sheppard and his associates reported that the TRA was effective in predicting

different behaviors (e.g., study a few hours, go to a weekend job, or write a letter). The frequency-weighted-average

correlation was 0.53 for the intention/behavior relationship, and 0.66 for the (attitudes and subjective

norm)/intention. They also reported that behavior was predicted using the TRA even in situations that fell outside

the boundary conditions set for the model (e.g., behavior involving an explicit choice among alternatives) (Sheppard

et al.). Thus, the robustness of the TRA was established.

2.2. The Technology Acceptance Model

The TRA provided the theoretical framework used by Da vis (1989) to study technology adoption behavior. A

belief set for adopting technology was generated by Davis in consistence with Fishbein and Ajzen’s (1975)

recommendation. The belief set consisted of two elements, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use

(PEOU). Davis (1989) defined PU as “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular [information]

system would enhance his or her job performance” (p. 320), and PEOU as “the degree to which a person believes

that using a particular [information] system would be free of effort” (p. 320). A visual representation of the elements

in the TAM is presented in Fig. 2.

1003Rima Fayad and David Paper / Procedia Economics and Finance 26 ( 2015 ) 1000 – 1006

Fig. 2. The Technology Acceptance Model

2.3. TAM Application and Extension Studies

Other studies with the purpose of apply ing and/or extending the TAM followed. In a study to apply the TAM in a

computer technology adoption instance while comparing it to the TRA, the relationship between PU and PEOU

(specific beliefs about technology adoption in the TAM) and attitudes (elements in the TRA) was tested (Davis et al.,

1989). PU scores were associated with reported intentions to use an information system. In addition, PU scores were

strongly related to reported intentions to use the system because in the work environment, intention to use a system

may be based on anticipated performance outcome irrespective of an overall attitude towards the system. Employees

might have a negative attitude towards a system, but yet use it because they perceive it to be advantageous in terms

of job performance (Davis et al., 1989).

In another study to evaluate the TAM (Szajna, 1996) subjects’ PU, PEOU, intentions to use an email system, as

well as self-reported usage were measured. In addition, actual usage of was measured as the number of computer

logs of messages sent. PU scores explained 52% of the variance in reported intention to use the electronic mail

system. Reported intention to use the system scores explained 32% of the variance in subjects’ self-reported usage

of the electronic mail system and only 6% of the variance in actual usage of the system. Warning was raised against

the substitution of self-reported usage for actual usage of information systems in future research (Szajna, 1996).

In a study with the purpose of reviewing user acceptance models (TAM and TRA among them) and formulating a

unified model of technology use, (Venkatesh, Morris, Davis and Davis, 2003) a measure of intention to use a

technology to predict adoption of that technology was employed. A longitudinal study of four new technologies at

four different organizations was conducted for both voluntary and mandatory use. Reported intention to use the

technology explained 59% of the variance in subjects’ self-predicted use of the technology. The authors suggested

that the behavioral expectations (Warshaw & Davis, 1985) about usage should be studied in future technology

adoption research in order to account for additional variance in behavior. They also recommended that researchers

study the relationship between user acceptance of the technology and the outcomes of technology usage. Little or no

research has been conducted to address this relationship, they reported. They also suggested that technology

adoption be studied in non-organizational settings, namely E-commerce (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

In research on E-commerce, the TAM was applied and extended (Kou faris, 2002) by adding consumer shopping

enjoyment to PU and PEOU as predictors of intention to return to a web site for future shopping. PU, PEOU, and

shopping enjoyment scores explained 54% of the variance in intention to return to the web site for future shopping.

This study confirmed, in E-commerce, the previous TAM research results concerning the importance of PU in

predicting intentions to use a system (Koufaris, 2002).

The TAM was extended by adding consumer trust in the electronic vendor (E-vendor) as a determinant of

intention to shop online (Gefen et al., 2003b). Intention to use E-commerce was defined as the intention of the

subject to provide his or her credit card numbers and personal information to the E-vendor. Actual shopping

behavior was not measured. PU was a stronger predictor of intended E-commerce use than was PEOU or trust. The

path loading from consumer trust to intention to shop online was .26. The path loading from PEOU to intention was

Fig. 2. The Technology Acceptance Model

2.3. TAM Application and Extension Studies

Other studies with the purpose of apply ing and/or extending the TAM followed. In a study to apply the TAM in a

computer technology adoption instance while comparing it to the TRA, the relationship between PU and PEOU

(specific beliefs about technology adoption in the TAM) and attitudes (elements in the TRA) was tested (Davis et al.,

1989). PU scores were associated with reported intentions to use an information system. In addition, PU scores were

strongly related to reported intentions to use the system because in the work environment, intention to use a system

may be based on anticipated performance outcome irrespective of an overall attitude towards the system. Employees

might have a negative attitude towards a system, but yet use it because they perceive it to be advantageous in terms

of job performance (Davis et al., 1989).

In another study to evaluate the TAM (Szajna, 1996) subjects’ PU, PEOU, intentions to use an email system, as

well as self-reported usage were measured. In addition, actual usage of was measured as the number of computer

logs of messages sent. PU scores explained 52% of the variance in reported intention to use the electronic mail

system. Reported intention to use the system scores explained 32% of the variance in subjects’ self-reported usage

of the electronic mail system and only 6% of the variance in actual usage of the system. Warning was raised against

the substitution of self-reported usage for actual usage of information systems in future research (Szajna, 1996).

In a study with the purpose of reviewing user acceptance models (TAM and TRA among them) and formulating a

unified model of technology use, (Venkatesh, Morris, Davis and Davis, 2003) a measure of intention to use a

technology to predict adoption of that technology was employed. A longitudinal study of four new technologies at

four different organizations was conducted for both voluntary and mandatory use. Reported intention to use the

technology explained 59% of the variance in subjects’ self-predicted use of the technology. The authors suggested

that the behavioral expectations (Warshaw & Davis, 1985) about usage should be studied in future technology

adoption research in order to account for additional variance in behavior. They also recommended that researchers

study the relationship between user acceptance of the technology and the outcomes of technology usage. Little or no

research has been conducted to address this relationship, they reported. They also suggested that technology

adoption be studied in non-organizational settings, namely E-commerce (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

In research on E-commerce, the TAM was applied and extended (Kou faris, 2002) by adding consumer shopping

enjoyment to PU and PEOU as predictors of intention to return to a web site for future shopping. PU, PEOU, and

shopping enjoyment scores explained 54% of the variance in intention to return to the web site for future shopping.

This study confirmed, in E-commerce, the previous TAM research results concerning the importance of PU in

predicting intentions to use a system (Koufaris, 2002).

The TAM was extended by adding consumer trust in the electronic vendor (E-vendor) as a determinant of

intention to shop online (Gefen et al., 2003b). Intention to use E-commerce was defined as the intention of the

subject to provide his or her credit card numbers and personal information to the E-vendor. Actual shopping

behavior was not measured. PU was a stronger predictor of intended E-commerce use than was PEOU or trust. The

path loading from consumer trust to intention to shop online was .26. The path loading from PEOU to intention was

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1004 Rima Fayad and David Paper / Procedia Economics and Finance 26 ( 2015 ) 1000 – 1006

also .26. However, the path loading from PU to intention to shop online was .40. The authors acknowledged that the

conceptualization of intended behavior in their study was narrow even though it captured two essential aspects of

online purchasing: intention to give credit card number and personal information to the E-vendor. They suggested

that future researchers include an overall measure of intention to shop from the E-vendor again. They also suggested

that future researchers include in their studies other measurements of intention to use E-commerce (Gefen et al.,

2003b).

2.4. E-commerce and User Satisfaction

User satisfaction is a potentially important variable in IS and th e online environment research. In discussing the

online environment, Szymanski and Hise (2000) first used the term E-satisfaction (Gefen & Straub, 2000) to refer to

customer satisfaction with an E-retailer. Six correlates of E-satisfaction were identified: convenience, product

offerings, product information, site design, and financial security. The relationship between E-satisfaction and

intention to use E-commerce was not tested (Szymanski & Hise, 2000).

Although other researchers have studied user satisfaction with E-commerce (Bechwati & Xia, 2003; Devaraj,

Fan, & Kohli, 2002; Kim & Lim, 2001; McKinney, Yoon, & Zahedi, 2002; Otto, Najdawi, & Caron, 2000), none

have reported a test of the relationship between E-satisfaction and E-commerce use or intention to use.

In user satisfaction with information systems studies, IS researchers have used user satisfaction measurement

instruments (Bailey & Pearson, 1983; Doll & Torkzadeh, 1988) that were not balanced between process and

outcome satisfaction items. Revising the instruments to include items for both process and outcome satisfaction was

recommended for future IS user satisfaction research (Woodroof & Kasper, 1998).

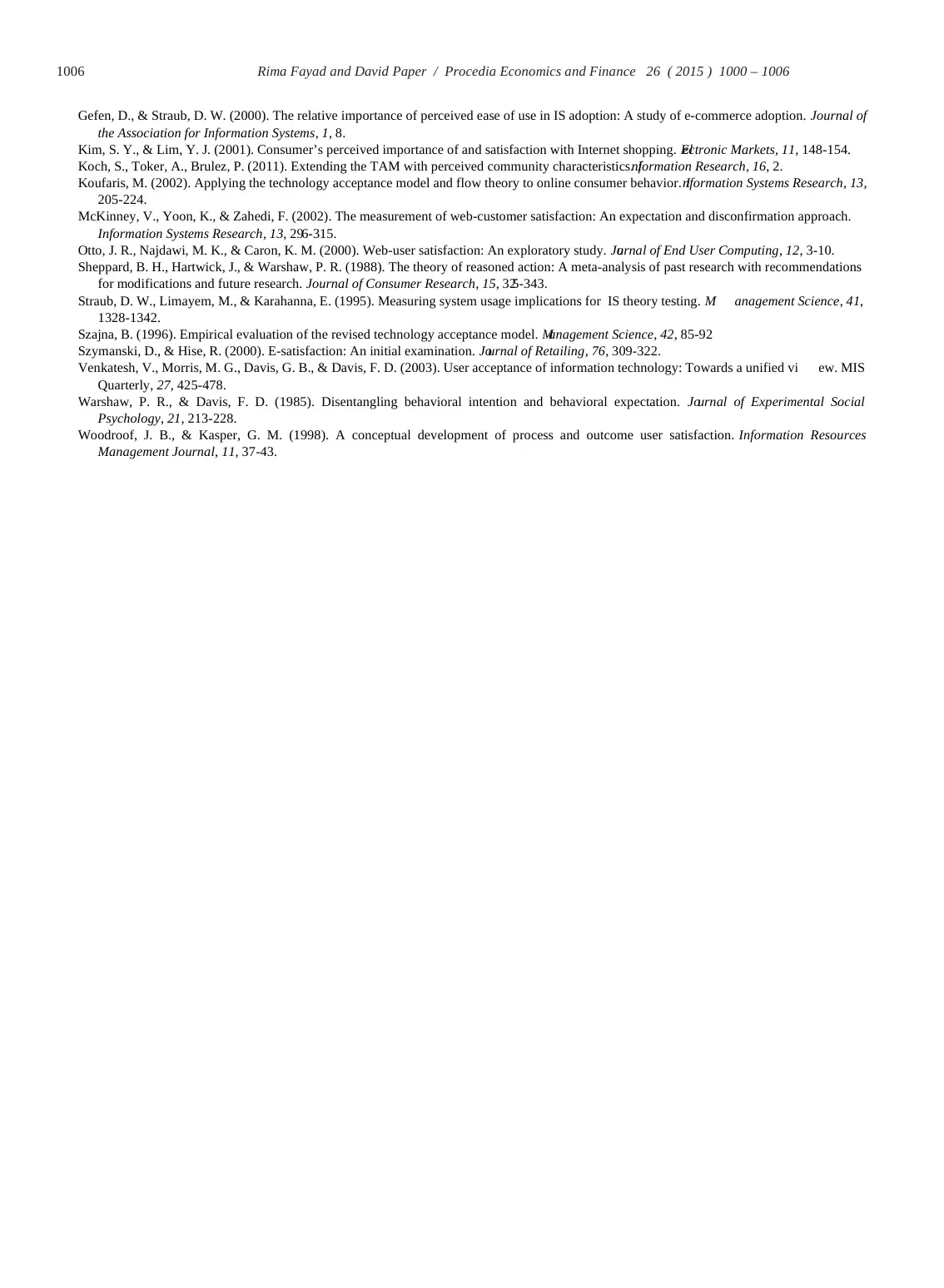

Based on the above review of TAM and E-commerce related literature, the following variables were identified in

order to extend the TAM to better serve as an E-commerce adoption model. The variables are process (Woodroof &

Kasper, 1998) of E-commerce use satisfaction, outcome (Woodroo f & Kasper, 1998) of the online shopping

experience satisfaction, behavioral expectations (Venkatesh et al., 2003) about E-commerce use.

3. Evaluation

The TAM application and extension studies prese nted above are a representative sample of the plethora of such

studies. There exist, to our knowledge, around 100 TAM application and extension studies. After thorough review of

these studies, we detected the following assertions. First, PU is a strong predictor of behavioral intentions in

different environments (E-commerce and non E-commerce). Second, there is a relationship between PU and PEOU.

This relationship is evident in different environments (E-commerce and non E-commerce). Third, there is a need to

measure actual use instead of substituting it with behavioral intentions. Also, there is a scarcity of TAM studies

measuring actual use. In fact, all the TAM studies we examined, with the exception of three (Straub et al., 1995;

Szajna, 1996; Venkatesh et al., 2003), used intention or self-reports as a substitute measure for behavior. Fourth, we

identified PS and OS as possible predictor variables of both behavioral intentions and actual use. Fifth, there is a

need to study behavioral expectations in addition to behavioral intentions when predicting behavior using the TAM.

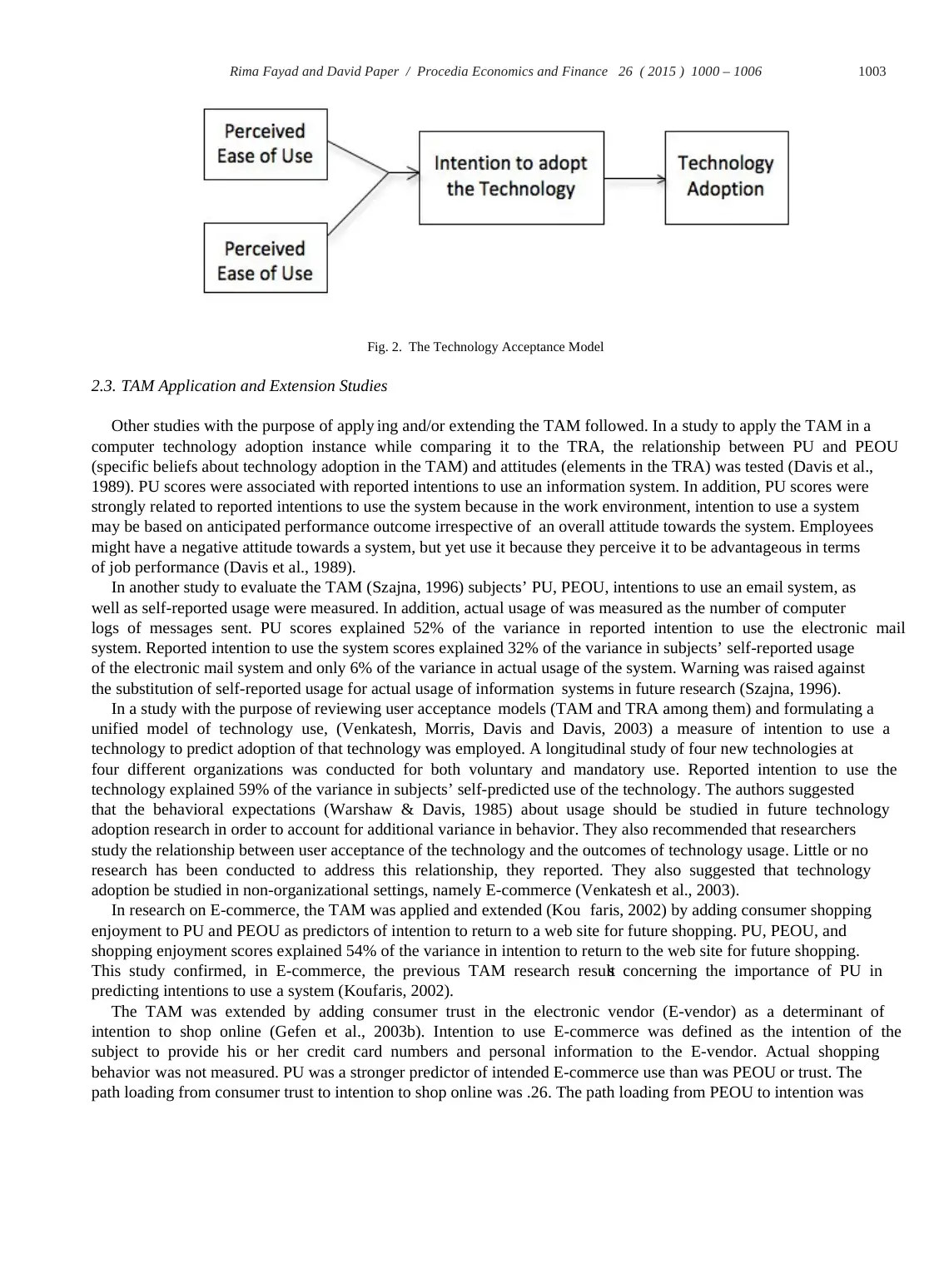

4. Suggested Extended TAM Model

Grounded in the TAM and E-commerce related literature, and following our evaluations of that literature, we

identified the following variables that we used to extend the TAM to potentially better serve as an E-commerce

adoption model. The predictor variables are satisfaction with process (W oodroof & Kasper, 1998) of E-commerce

use, satisfaction with outcome (Woodroof & Kasper) of E-commerce use, and behavioral expectations (Venkatesh et

al., 2003) about E-commerce use. In addition to these extended TAM variables, we added a criterion variable,

namely an actual measure of E-commerce use (Szajna, 1996; Venkatesh et al.). T he proposed model is presented in

Fig. 3.

also .26. However, the path loading from PU to intention to shop online was .40. The authors acknowledged that the

conceptualization of intended behavior in their study was narrow even though it captured two essential aspects of

online purchasing: intention to give credit card number and personal information to the E-vendor. They suggested

that future researchers include an overall measure of intention to shop from the E-vendor again. They also suggested

that future researchers include in their studies other measurements of intention to use E-commerce (Gefen et al.,

2003b).

2.4. E-commerce and User Satisfaction

User satisfaction is a potentially important variable in IS and th e online environment research. In discussing the

online environment, Szymanski and Hise (2000) first used the term E-satisfaction (Gefen & Straub, 2000) to refer to

customer satisfaction with an E-retailer. Six correlates of E-satisfaction were identified: convenience, product

offerings, product information, site design, and financial security. The relationship between E-satisfaction and

intention to use E-commerce was not tested (Szymanski & Hise, 2000).

Although other researchers have studied user satisfaction with E-commerce (Bechwati & Xia, 2003; Devaraj,

Fan, & Kohli, 2002; Kim & Lim, 2001; McKinney, Yoon, & Zahedi, 2002; Otto, Najdawi, & Caron, 2000), none

have reported a test of the relationship between E-satisfaction and E-commerce use or intention to use.

In user satisfaction with information systems studies, IS researchers have used user satisfaction measurement

instruments (Bailey & Pearson, 1983; Doll & Torkzadeh, 1988) that were not balanced between process and

outcome satisfaction items. Revising the instruments to include items for both process and outcome satisfaction was

recommended for future IS user satisfaction research (Woodroof & Kasper, 1998).

Based on the above review of TAM and E-commerce related literature, the following variables were identified in

order to extend the TAM to better serve as an E-commerce adoption model. The variables are process (Woodroof &

Kasper, 1998) of E-commerce use satisfaction, outcome (Woodroo f & Kasper, 1998) of the online shopping

experience satisfaction, behavioral expectations (Venkatesh et al., 2003) about E-commerce use.

3. Evaluation

The TAM application and extension studies prese nted above are a representative sample of the plethora of such

studies. There exist, to our knowledge, around 100 TAM application and extension studies. After thorough review of

these studies, we detected the following assertions. First, PU is a strong predictor of behavioral intentions in

different environments (E-commerce and non E-commerce). Second, there is a relationship between PU and PEOU.

This relationship is evident in different environments (E-commerce and non E-commerce). Third, there is a need to

measure actual use instead of substituting it with behavioral intentions. Also, there is a scarcity of TAM studies

measuring actual use. In fact, all the TAM studies we examined, with the exception of three (Straub et al., 1995;

Szajna, 1996; Venkatesh et al., 2003), used intention or self-reports as a substitute measure for behavior. Fourth, we

identified PS and OS as possible predictor variables of both behavioral intentions and actual use. Fifth, there is a

need to study behavioral expectations in addition to behavioral intentions when predicting behavior using the TAM.

4. Suggested Extended TAM Model

Grounded in the TAM and E-commerce related literature, and following our evaluations of that literature, we

identified the following variables that we used to extend the TAM to potentially better serve as an E-commerce

adoption model. The predictor variables are satisfaction with process (W oodroof & Kasper, 1998) of E-commerce

use, satisfaction with outcome (Woodroof & Kasper) of E-commerce use, and behavioral expectations (Venkatesh et

al., 2003) about E-commerce use. In addition to these extended TAM variables, we added a criterion variable,

namely an actual measure of E-commerce use (Szajna, 1996; Venkatesh et al.). T he proposed model is presented in

Fig. 3.

1005Rima Fayad and David Paper / Procedia Economics and Finance 26 ( 2015 ) 1000 – 1006

Fig. 3. The Extended Technology Acceptance Model

5. Conclusion

Since there is a plethora of TAM studies, what is the valu e of one more? If a new TAM study measured actual

behavior as per the recommendation of Davis (1989), it would address one of the limitations of the original TAM

and potentially confirm its robustness. In addition, if such a study applied the TAM in a different environment than

the original, it would potentially provide more evidence of the TAM’s generalizability. Our study is thereby

valuable as it is aimed at supporting the robustness and generalizability of the TAM.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bailey, J. E., & Pearson, S. W. (1983). Development of a tool for measuring and analyzing computer user satisfaction. Management Science, 29,

530-545.

Bechawati, N. N., & Xia, L. (2003). Do computers sweat? The impact of perceived effort of online decision aids on consumer’s sat isfaction with

the decision process. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13, 139-148.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). An empirical analysis of the antecedents of electronic commerce service continuance. Dec ision Support Systems, 32,

201-214.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13, 318-340.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models.

Management Science, 35, 982-1003.

Devaraj, S., Fan, M., & Kohli, R. (2002). Antecedents of B2C channel satisfaction and preference: Validating e-commerce metrics. Inf ormation

Systems Research, 13, 316-333.

Doll, W. J., & Torkzadeh, G. (1988). The measurement of end-user computing satisfaction. MIS Quarterly, 12, 258-274.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-

Wesley.

Mulpuru, S. (2011). Retrieved March 30, 2015, from http://www.forrester.com/

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003a). Inexperience and experience with online stores: The importance of tam and trust. IEEE

Transactions on Engineering Management, 50, 307-321.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003b). Trust and TAM in online shopping: an integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27, 51-90.

Fig. 3. The Extended Technology Acceptance Model

5. Conclusion

Since there is a plethora of TAM studies, what is the valu e of one more? If a new TAM study measured actual

behavior as per the recommendation of Davis (1989), it would address one of the limitations of the original TAM

and potentially confirm its robustness. In addition, if such a study applied the TAM in a different environment than

the original, it would potentially provide more evidence of the TAM’s generalizability. Our study is thereby

valuable as it is aimed at supporting the robustness and generalizability of the TAM.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bailey, J. E., & Pearson, S. W. (1983). Development of a tool for measuring and analyzing computer user satisfaction. Management Science, 29,

530-545.

Bechawati, N. N., & Xia, L. (2003). Do computers sweat? The impact of perceived effort of online decision aids on consumer’s sat isfaction with

the decision process. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13, 139-148.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). An empirical analysis of the antecedents of electronic commerce service continuance. Dec ision Support Systems, 32,

201-214.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13, 318-340.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models.

Management Science, 35, 982-1003.

Devaraj, S., Fan, M., & Kohli, R. (2002). Antecedents of B2C channel satisfaction and preference: Validating e-commerce metrics. Inf ormation

Systems Research, 13, 316-333.

Doll, W. J., & Torkzadeh, G. (1988). The measurement of end-user computing satisfaction. MIS Quarterly, 12, 258-274.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-

Wesley.

Mulpuru, S. (2011). Retrieved March 30, 2015, from http://www.forrester.com/

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003a). Inexperience and experience with online stores: The importance of tam and trust. IEEE

Transactions on Engineering Management, 50, 307-321.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003b). Trust and TAM in online shopping: an integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27, 51-90.

1006 Rima Fayad and David Paper / Procedia Economics and Finance 26 ( 2015 ) 1000 – 1006

Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (2000). The relative importance of perceived ease of use in IS adoption: A study of e-commerce adoption. Journal of

the Association for Information Systems, 1, 8.

Kim, S. Y., & Lim, Y. J. (2001). Consumer’s perceived importance of and satisfaction with Internet shopping. Electronic Markets, 11, 148-154.

Koch, S., Toker, A., Brulez, P. (2011). Extending the TAM with perceived community characteristics. Information Research, 16, 2.

Koufaris, M. (2002). Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to online consumer behavior. Information Systems Research, 13,

205-224.

McKinney, V., Yoon, K., & Zahedi, F. (2002). The measurement of web-customer satisfaction: An expectation and disconfirmation approach.

Information Systems Research, 13, 296-315.

Otto, J. R., Najdawi, M. K., & Caron, K. M. (2000). Web-user satisfaction: An exploratory study. Journal of End User Computing, 12, 3-10.

Sheppard, B. H., Hartwick, J., & Warshaw, P. R. (1988). The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recommendations

for modifications and future research. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 325-343.

Straub, D. W., Limayem, M., & Karahanna, E. (1995). Measuring system usage implications for IS theory testing. M anagement Science, 41,

1328-1342.

Szajna, B. (1996). Empirical evaluation of the revised technology acceptance model. Management Science, 42, 85-92

Szymanski, D., & Hise, R. (2000). E-satisfaction: An initial examination. Journal of Retailing, 76, 309-322.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Towards a unified vi ew. MIS

Quarterly, 27, 425-478.

Warshaw, P. R., & Davis, F. D. (1985). Disentangling behavioral intention and behavioral expectation. Journal of Experimental Social

Psychology, 21, 213-228.

Woodroof, J. B., & Kasper, G. M. (1998). A conceptual development of process and outcome user satisfaction. Information Resources

Management Journal, 11, 37-43.

Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (2000). The relative importance of perceived ease of use in IS adoption: A study of e-commerce adoption. Journal of

the Association for Information Systems, 1, 8.

Kim, S. Y., & Lim, Y. J. (2001). Consumer’s perceived importance of and satisfaction with Internet shopping. Electronic Markets, 11, 148-154.

Koch, S., Toker, A., Brulez, P. (2011). Extending the TAM with perceived community characteristics. Information Research, 16, 2.

Koufaris, M. (2002). Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to online consumer behavior. Information Systems Research, 13,

205-224.

McKinney, V., Yoon, K., & Zahedi, F. (2002). The measurement of web-customer satisfaction: An expectation and disconfirmation approach.

Information Systems Research, 13, 296-315.

Otto, J. R., Najdawi, M. K., & Caron, K. M. (2000). Web-user satisfaction: An exploratory study. Journal of End User Computing, 12, 3-10.

Sheppard, B. H., Hartwick, J., & Warshaw, P. R. (1988). The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recommendations

for modifications and future research. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 325-343.

Straub, D. W., Limayem, M., & Karahanna, E. (1995). Measuring system usage implications for IS theory testing. M anagement Science, 41,

1328-1342.

Szajna, B. (1996). Empirical evaluation of the revised technology acceptance model. Management Science, 42, 85-92

Szymanski, D., & Hise, R. (2000). E-satisfaction: An initial examination. Journal of Retailing, 76, 309-322.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Towards a unified vi ew. MIS

Quarterly, 27, 425-478.

Warshaw, P. R., & Davis, F. D. (1985). Disentangling behavioral intention and behavioral expectation. Journal of Experimental Social

Psychology, 21, 213-228.

Woodroof, J. B., & Kasper, G. M. (1998). A conceptual development of process and outcome user satisfaction. Information Resources

Management Journal, 11, 37-43.

1 out of 7

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.