Lonsdaleite vs. Diamond: Strength and Stiffness Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/18

|4

|4346

|54

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on first-principles calculations, investigates the mechanical properties of lonsdaleite, a hexagonal form of carbon, and compares them to those of diamond. The study reveals that lonsdaleite exhibits superior compressive strength, Young's modulus, and stiffness compared to diamond. The research explores the material's elastic stiffness, bulk modulus, compressive strength, and tensile strength. The findings suggest that lonsdaleite is a stronger and stiffer naturally occurring substance. The report analyzes stress-strain curves to determine the compressive and tensile strengths along different orientations. The study highlights the potential of lonsdaleite for various applications due to its exceptional mechanical properties. The report also includes a comparison of the stiffness matrix components and bulk modulus, demonstrating lonsdaleite's enhanced uniaxial strength properties. The results indicate that lonsdaleite could be a significant advancement in material science, offering a combination of properties that rivals or surpasses those of diamond.

Lonsdaleite – A material stronger and stiffer than diamond

Li Qingkun,a,⇑ Sun Yi,b Li Zhiyuanc and Zhou Yua

aInstitute for Advanced Ceramics, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, People’s Republic of China

bThe Department of Astronautics Science and Mechanics, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, People’s Republi

cInstitute of Electronic Engineering, Heilongjiang University, Harbin 150080, People’s Republic of China

Received 26 March 2011; accepted 9 April 2011

Available online 13 April 2011

Based on first-principles calculations, we demonstrate that lonsdaleite exhibits many excellent static mechanical proper

instance, the compressive strength, coefficient of stiffness and Young’s modulus of lonsdaleite all exceed the correspondin

diamond. Moreover, the bulk modulus of lonsdaleite is as good as that of diamond, and its tensile strength is similar to tha

mond. Therefore, our results suggest that lonsdaleite is a stronger and stiffer naturally occurring substance than diamond

Ó 2011 Acta Materialia Inc. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Lonsdaleite; Diamond; Stress–rupture density functions; Carbon

Diamond, a naturally occurring substance, is not

only considered to be the hardest material known [1–3],

but also presents excellent compressive strength [4,5], ten-

sile strength [3,5–7],Young’s modulus [1,8,9]and bulk

modulus [10].Over the past decade,there have been a

numberof reportsof materialsthat exhibithardness

and stiffnessclose to thatof diamond.For example,

experiments showed that cubic and wurtzite BN nano-

composites exhibit high hardness of 85 GPa [11],close

to the 70–100 GPa of diamond [12,13]. Theoretical and

experimental results demonstrated that C3N 4 exhibits a

hardness ofabout 85 GPa,rivalling thatof diamond

[14]. Composite materials created by mixing particles of

barium titanate and tin show high viscoelastic modulus

(Young’s modulus) close to 10,000 GPa [8], significantly

greater than the Young’s modulus of diamond,

1207 GPa [7]. Acetylenic molecular rods have a Young’s

modulus around 40 times larger than that of diamond

[1]. Although the new records of mechanicalproperties

were gradually reported, it is still difficult to find a mate-

rial with a combination of mechanical properties that riv-

als or exceeds that of diamond.

Lonsdaleite (hexagonal diamond), a natural substance

[15], has been attracting much attention because of its po-

tential excellent mechanical properties [3,16]. Lonsdaleite

is a carbon-based materialwith a hexagonalcrystallo-

graphic structure [3,17], and can be synthesized like dia-

mond under high static pressure and high temperature

[18]. A recent theoretical analysis has predicted lonsdale-

ite to have a higher indentation strength than diamond

[3], which meansthat lonsdaleitemight exhibit the

much-sought-after combination mechanical properties.

In this work, the mechanical properties of lonsdaleite,

including stiffness matrix, Young’s modulus, bulk mod-

ulus, compressive strength and tensile strength,have

been carefully calculated by a first-principles method.

Based on an analysis of the crystallographic structure,

we discuss the origin of lonsdaleite’s excellent mechani-

cal properties. Furthermore, the prospects for the appli-

cation of lonsdaleite are also discussed.

The structure-optimization and mechanical-property

calculations for lonsdaleite were performed using the CA-

STEP package based on the first-principles norm-con-

serving pseudopotentialapproach [19,20].For all the

calculations,the exchange–correlation potentialof the

generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Per-

dew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) density functional [21] was

used. The energy-cutoff was set at 600 eV, and the maxi-

mum energy tolerancefor geometryoptimization

was <1.0 105 eV. For the structure-optimization and

mechanical-propertycalculationsof lonsdaleite,6

8 6 Monkhorst–Pack K-points [22]were adopted in

an 8-atom rectangularsolid supercell.Corresponding

calculations for diamond as a reference materialwere

performed,using either 6 8 6 Monkhorst–Pack

K-points [22]in a 12-atom rectangular solid supercell,

or 8 8 8 Monkhorst–Pack K-points in a 4-atom cu-

bic supercell according to the orientation of the diamond.

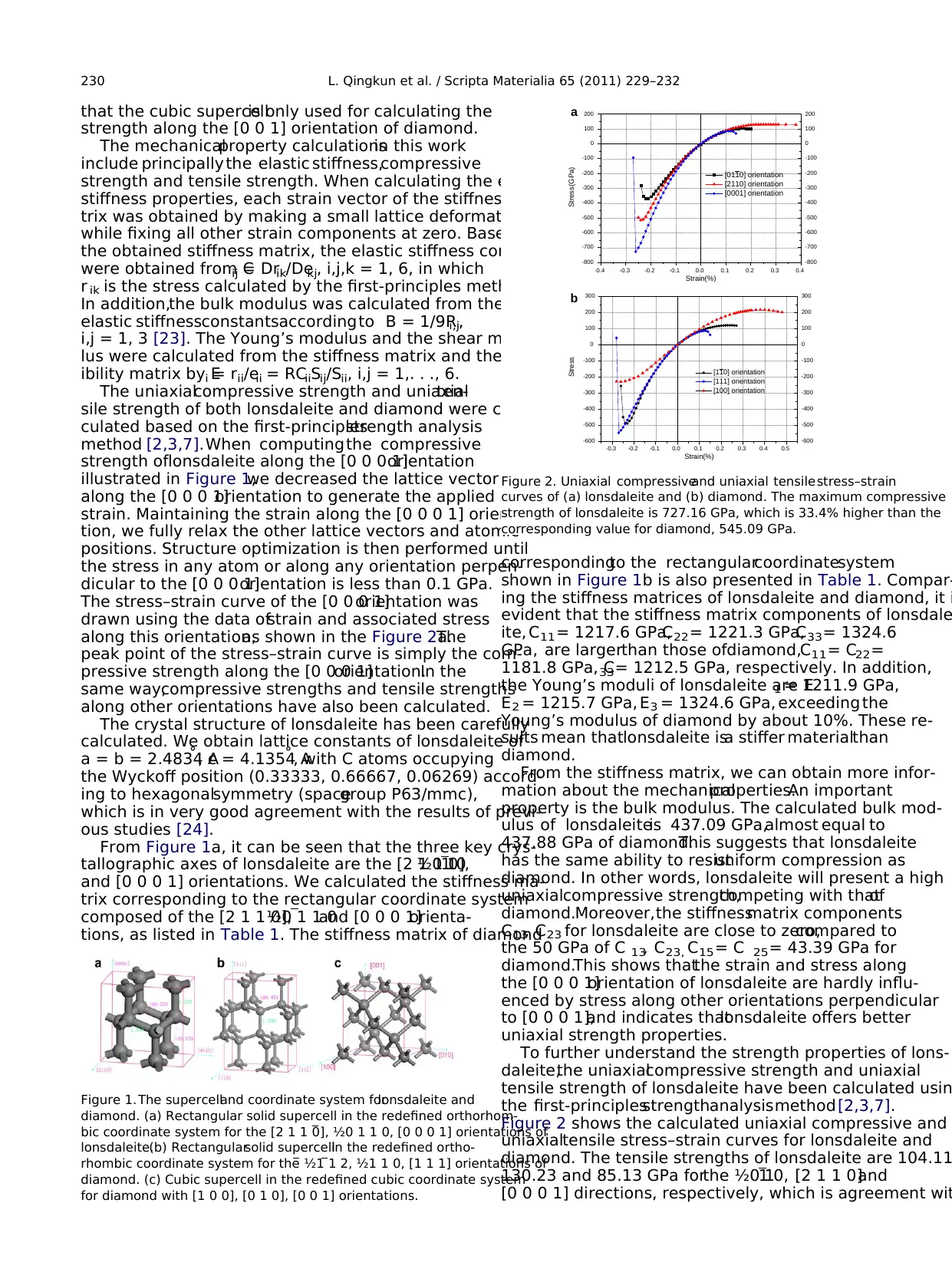

These supercellsof lonsdaleiteand diamond are

illustrated in Figure 1a–c, respectively. It should be noted

1359-6462/$ - see front matter Ó 2011 Acta Materialia Inc. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2011.04.013

⇑Corresponding author.Tel.: +086 045186419560;fax: +086 451

86403725; e-mail: liqingkun@hit.edu.cn

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Scripta Materialia 65 (2011) 229–232

www.elsevier.com/locate/scriptamat

Li Qingkun,a,⇑ Sun Yi,b Li Zhiyuanc and Zhou Yua

aInstitute for Advanced Ceramics, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, People’s Republic of China

bThe Department of Astronautics Science and Mechanics, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, People’s Republi

cInstitute of Electronic Engineering, Heilongjiang University, Harbin 150080, People’s Republic of China

Received 26 March 2011; accepted 9 April 2011

Available online 13 April 2011

Based on first-principles calculations, we demonstrate that lonsdaleite exhibits many excellent static mechanical proper

instance, the compressive strength, coefficient of stiffness and Young’s modulus of lonsdaleite all exceed the correspondin

diamond. Moreover, the bulk modulus of lonsdaleite is as good as that of diamond, and its tensile strength is similar to tha

mond. Therefore, our results suggest that lonsdaleite is a stronger and stiffer naturally occurring substance than diamond

Ó 2011 Acta Materialia Inc. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Lonsdaleite; Diamond; Stress–rupture density functions; Carbon

Diamond, a naturally occurring substance, is not

only considered to be the hardest material known [1–3],

but also presents excellent compressive strength [4,5], ten-

sile strength [3,5–7],Young’s modulus [1,8,9]and bulk

modulus [10].Over the past decade,there have been a

numberof reportsof materialsthat exhibithardness

and stiffnessclose to thatof diamond.For example,

experiments showed that cubic and wurtzite BN nano-

composites exhibit high hardness of 85 GPa [11],close

to the 70–100 GPa of diamond [12,13]. Theoretical and

experimental results demonstrated that C3N 4 exhibits a

hardness ofabout 85 GPa,rivalling thatof diamond

[14]. Composite materials created by mixing particles of

barium titanate and tin show high viscoelastic modulus

(Young’s modulus) close to 10,000 GPa [8], significantly

greater than the Young’s modulus of diamond,

1207 GPa [7]. Acetylenic molecular rods have a Young’s

modulus around 40 times larger than that of diamond

[1]. Although the new records of mechanicalproperties

were gradually reported, it is still difficult to find a mate-

rial with a combination of mechanical properties that riv-

als or exceeds that of diamond.

Lonsdaleite (hexagonal diamond), a natural substance

[15], has been attracting much attention because of its po-

tential excellent mechanical properties [3,16]. Lonsdaleite

is a carbon-based materialwith a hexagonalcrystallo-

graphic structure [3,17], and can be synthesized like dia-

mond under high static pressure and high temperature

[18]. A recent theoretical analysis has predicted lonsdale-

ite to have a higher indentation strength than diamond

[3], which meansthat lonsdaleitemight exhibit the

much-sought-after combination mechanical properties.

In this work, the mechanical properties of lonsdaleite,

including stiffness matrix, Young’s modulus, bulk mod-

ulus, compressive strength and tensile strength,have

been carefully calculated by a first-principles method.

Based on an analysis of the crystallographic structure,

we discuss the origin of lonsdaleite’s excellent mechani-

cal properties. Furthermore, the prospects for the appli-

cation of lonsdaleite are also discussed.

The structure-optimization and mechanical-property

calculations for lonsdaleite were performed using the CA-

STEP package based on the first-principles norm-con-

serving pseudopotentialapproach [19,20].For all the

calculations,the exchange–correlation potentialof the

generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Per-

dew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) density functional [21] was

used. The energy-cutoff was set at 600 eV, and the maxi-

mum energy tolerancefor geometryoptimization

was <1.0 105 eV. For the structure-optimization and

mechanical-propertycalculationsof lonsdaleite,6

8 6 Monkhorst–Pack K-points [22]were adopted in

an 8-atom rectangularsolid supercell.Corresponding

calculations for diamond as a reference materialwere

performed,using either 6 8 6 Monkhorst–Pack

K-points [22]in a 12-atom rectangular solid supercell,

or 8 8 8 Monkhorst–Pack K-points in a 4-atom cu-

bic supercell according to the orientation of the diamond.

These supercellsof lonsdaleiteand diamond are

illustrated in Figure 1a–c, respectively. It should be noted

1359-6462/$ - see front matter Ó 2011 Acta Materialia Inc. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2011.04.013

⇑Corresponding author.Tel.: +086 045186419560;fax: +086 451

86403725; e-mail: liqingkun@hit.edu.cn

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Scripta Materialia 65 (2011) 229–232

www.elsevier.com/locate/scriptamat

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

that the cubic supercellis only used for calculating the

strength along the [0 0 1] orientation of diamond.

The mechanicalproperty calculationsin this work

include principally the elastic stiffness,compressive

strength and tensile strength. When calculating the elastic

stiffness properties, each strain vector of the stiffness ma-

trix was obtained by making a small lattice deformation,

while fixing all other strain components at zero. Based on

the obtained stiffness matrix, the elastic stiffness constants

were obtained from Cij = Drik/Dekj, i,j,k = 1, 6, in which

r ik is the stress calculated by the first-principles method.

In addition,the bulk modulus was calculated from the

elastic stiffnessconstantsaccordingto B = 1/9Ri,j,

i,j = 1, 3 [23]. The Young’s modulus and the shear modu-

lus were calculated from the stiffness matrix and the flex-

ibility matrix by Ei = r ii/eii = RCiiSij/Sii, i,j = 1,. . ., 6.

The uniaxialcompressive strength and uniaxialten-

sile strength of both lonsdaleite and diamond were cal-

culated based on the first-principlesstrength analysis

method [2,3,7].When computingthe compressive

strength oflonsdaleite along the [0 0 0 1]orientation

illustrated in Figure 1,we decreased the lattice vector

along the [0 0 0 1]orientation to generate the applied

strain. Maintaining the strain along the [0 0 0 1] orienta-

tion, we fully relax the other lattice vectors and atomic

positions. Structure optimization is then performed until

the stress in any atom or along any orientation perpen-

dicular to the [0 0 0 1]orientation is less than 0.1 GPa.

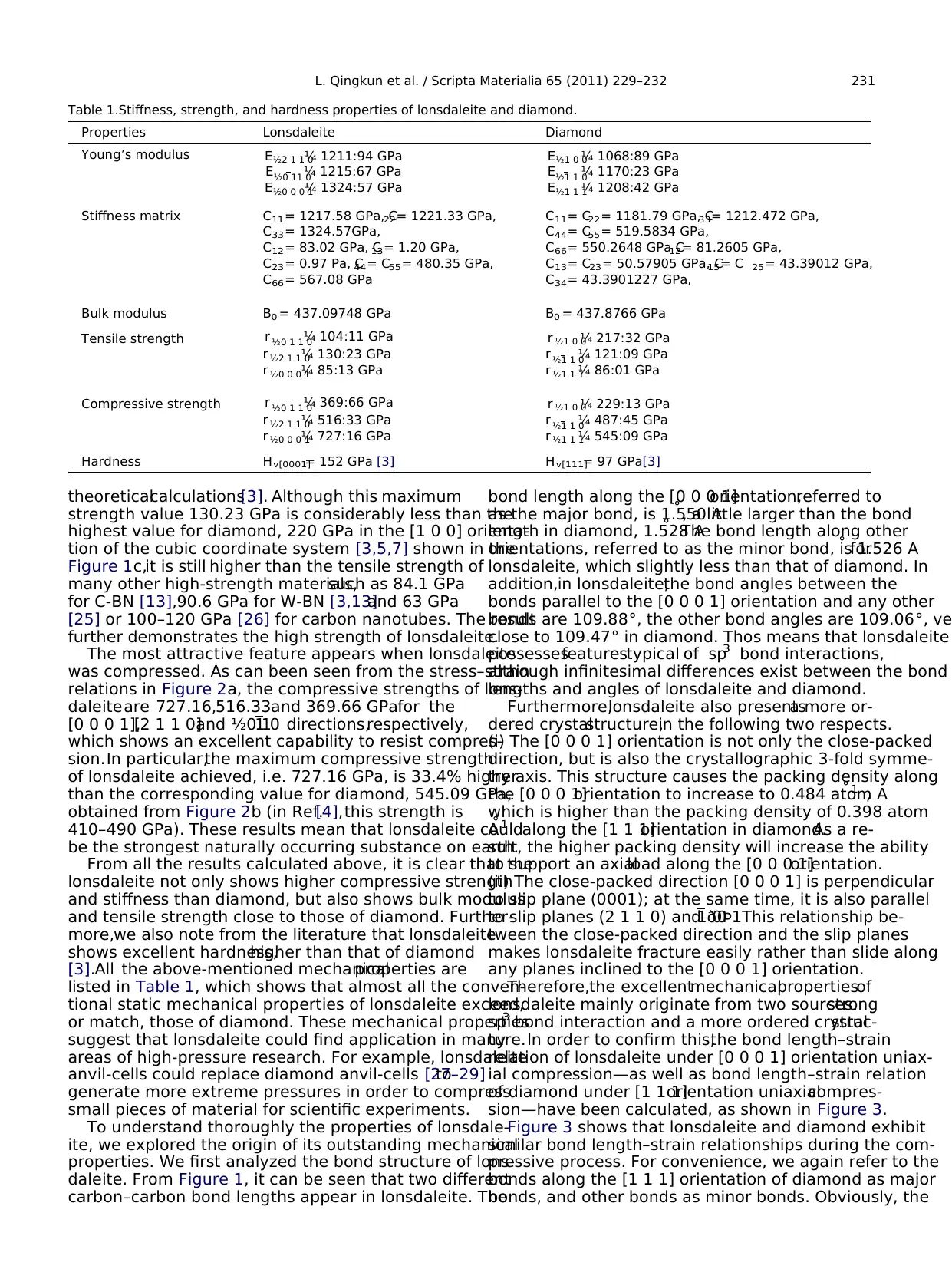

The stress–strain curve of the [0 0 0 1]orientation was

drawn using the data ofstrain and associated stress

along this orientation,as shown in the Figure 2a.The

peak point of the stress–strain curve is simply the com-

pressive strength along the [0 0 0 1]orientation.In the

same way,compressive strengths and tensile strengths

along other orientations have also been calculated.

The crystal structure of lonsdaleite has been carefully

calculated. We obtain lattice constants of lonsdaleite of

a = b = 2.4834 A˚, c = 4.1354 A˚, with C atoms occupying

the Wyckoff position (0.33333, 0.66667, 0.06269) accord-

ing to hexagonalsymmetry (spacegroup P63/mmc),

which is in very good agreement with the results of previ-

ous studies [24].

From Figure 1a, it can be seen that the three key crys-

tallographic axes of lonsdaleite are the [2 1 1 0],½0 11 0

and [0 0 0 1] orientations. We calculated the stiffness ma-

trix corresponding to the rectangular coordinate system

composed of the [2 1 1 0],½0 1 1 0and [0 0 0 1]orienta-

tions, as listed in Table 1. The stiffness matrix of diamond

correspondingto the rectangularcoordinatesystem

shown in Figure 1b is also presented in Table 1. Compar-

ing the stiffness matrices of lonsdaleite and diamond, it i

evident that the stiffness matrix components of lonsdale

ite, C 11= 1217.6 GPa,C 22= 1221.3 GPa,C 33= 1324.6

GPa, are largerthan those ofdiamond,C 11= C22=

1181.8 GPa, C33= 1212.5 GPa, respectively. In addition,

the Young’s moduli of lonsdaleite are E1 = 1211.9 GPa,

E 2 = 1215.7 GPa, E 3 = 1324.6 GPa, exceeding the

Young’s modulus of diamond by about 10%. These re-

sults mean thatlonsdaleite isa stiffer materialthan

diamond.

From the stiffness matrix, we can obtain more infor-

mation about the mechanicalproperties.An important

property is the bulk modulus. The calculated bulk mod-

ulus of lonsdaleiteis 437.09 GPa,almost equal to

437.88 GPa of diamond.This suggests that lonsdaleite

has the same ability to resistuniform compression as

diamond. In other words, lonsdaleite will present a high

uniaxialcompressive strength,competing with thatof

diamond.Moreover,the stiffnessmatrix components

C 13, C 23 for lonsdaleite are close to zero,compared to

the 50 GPa of C 13, C 23, C 15= C 25= 43.39 GPa for

diamond.This shows thatthe strain and stress along

the [0 0 0 1]orientation of lonsdaleite are hardly influ-

enced by stress along other orientations perpendicular

to [0 0 0 1],and indicates thatlonsdaleite offers better

uniaxial strength properties.

To further understand the strength properties of lons-

daleite,the uniaxialcompressive strength and uniaxial

tensile strength of lonsdaleite have been calculated usin

the first-principlesstrengthanalysismethod [2,3,7].

Figure 2 shows the calculated uniaxial compressive and

uniaxialtensile stress–strain curves for lonsdaleite and

diamond. The tensile strengths of lonsdaleite are 104.11

130.23 and 85.13 GPa forthe ½0 11 0, [2 1 1 0]and

[0 0 0 1] directions, respectively, which is agreement wit

Figure 1.The supercelland coordinate system forlonsdaleite and

diamond. (a) Rectangular solid supercell in the redefined orthorhom-

bic coordinate system for the [2 1 1 0], ½0 1 1 0, [0 0 0 1] orientations of

lonsdaleite.(b) Rectangularsolid supercellin the redefined ortho-

rhombic coordinate system for the ½1 1 2, ½1 1 0, [1 1 1] orientations of

diamond. (c) Cubic supercell in the redefined cubic coordinate system

for diamond with [1 0 0], [0 1 0], [0 0 1] orientations.

-0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4

-800

-700

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

-800

-700

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

[0110] orientation

[2110] orientation

[0001] orientation

Stress(GPa)

Strain(%)

-0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

300

[110] orientation

[111] orientation

Stress

Strain(%)

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

300

[100] orientation

a

b

Figure 2. Uniaxial compressiveand uniaxial tensilestress–strain

curves of (a) lonsdaleite and (b) diamond. The maximum compressive

strength of lonsdaleite is 727.16 GPa, which is 33.4% higher than the

corresponding value for diamond, 545.09 GPa.

230 L. Qingkun et al. / Scripta Materialia 65 (2011) 229–232

strength along the [0 0 1] orientation of diamond.

The mechanicalproperty calculationsin this work

include principally the elastic stiffness,compressive

strength and tensile strength. When calculating the elastic

stiffness properties, each strain vector of the stiffness ma-

trix was obtained by making a small lattice deformation,

while fixing all other strain components at zero. Based on

the obtained stiffness matrix, the elastic stiffness constants

were obtained from Cij = Drik/Dekj, i,j,k = 1, 6, in which

r ik is the stress calculated by the first-principles method.

In addition,the bulk modulus was calculated from the

elastic stiffnessconstantsaccordingto B = 1/9Ri,j,

i,j = 1, 3 [23]. The Young’s modulus and the shear modu-

lus were calculated from the stiffness matrix and the flex-

ibility matrix by Ei = r ii/eii = RCiiSij/Sii, i,j = 1,. . ., 6.

The uniaxialcompressive strength and uniaxialten-

sile strength of both lonsdaleite and diamond were cal-

culated based on the first-principlesstrength analysis

method [2,3,7].When computingthe compressive

strength oflonsdaleite along the [0 0 0 1]orientation

illustrated in Figure 1,we decreased the lattice vector

along the [0 0 0 1]orientation to generate the applied

strain. Maintaining the strain along the [0 0 0 1] orienta-

tion, we fully relax the other lattice vectors and atomic

positions. Structure optimization is then performed until

the stress in any atom or along any orientation perpen-

dicular to the [0 0 0 1]orientation is less than 0.1 GPa.

The stress–strain curve of the [0 0 0 1]orientation was

drawn using the data ofstrain and associated stress

along this orientation,as shown in the Figure 2a.The

peak point of the stress–strain curve is simply the com-

pressive strength along the [0 0 0 1]orientation.In the

same way,compressive strengths and tensile strengths

along other orientations have also been calculated.

The crystal structure of lonsdaleite has been carefully

calculated. We obtain lattice constants of lonsdaleite of

a = b = 2.4834 A˚, c = 4.1354 A˚, with C atoms occupying

the Wyckoff position (0.33333, 0.66667, 0.06269) accord-

ing to hexagonalsymmetry (spacegroup P63/mmc),

which is in very good agreement with the results of previ-

ous studies [24].

From Figure 1a, it can be seen that the three key crys-

tallographic axes of lonsdaleite are the [2 1 1 0],½0 11 0

and [0 0 0 1] orientations. We calculated the stiffness ma-

trix corresponding to the rectangular coordinate system

composed of the [2 1 1 0],½0 1 1 0and [0 0 0 1]orienta-

tions, as listed in Table 1. The stiffness matrix of diamond

correspondingto the rectangularcoordinatesystem

shown in Figure 1b is also presented in Table 1. Compar-

ing the stiffness matrices of lonsdaleite and diamond, it i

evident that the stiffness matrix components of lonsdale

ite, C 11= 1217.6 GPa,C 22= 1221.3 GPa,C 33= 1324.6

GPa, are largerthan those ofdiamond,C 11= C22=

1181.8 GPa, C33= 1212.5 GPa, respectively. In addition,

the Young’s moduli of lonsdaleite are E1 = 1211.9 GPa,

E 2 = 1215.7 GPa, E 3 = 1324.6 GPa, exceeding the

Young’s modulus of diamond by about 10%. These re-

sults mean thatlonsdaleite isa stiffer materialthan

diamond.

From the stiffness matrix, we can obtain more infor-

mation about the mechanicalproperties.An important

property is the bulk modulus. The calculated bulk mod-

ulus of lonsdaleiteis 437.09 GPa,almost equal to

437.88 GPa of diamond.This suggests that lonsdaleite

has the same ability to resistuniform compression as

diamond. In other words, lonsdaleite will present a high

uniaxialcompressive strength,competing with thatof

diamond.Moreover,the stiffnessmatrix components

C 13, C 23 for lonsdaleite are close to zero,compared to

the 50 GPa of C 13, C 23, C 15= C 25= 43.39 GPa for

diamond.This shows thatthe strain and stress along

the [0 0 0 1]orientation of lonsdaleite are hardly influ-

enced by stress along other orientations perpendicular

to [0 0 0 1],and indicates thatlonsdaleite offers better

uniaxial strength properties.

To further understand the strength properties of lons-

daleite,the uniaxialcompressive strength and uniaxial

tensile strength of lonsdaleite have been calculated usin

the first-principlesstrengthanalysismethod [2,3,7].

Figure 2 shows the calculated uniaxial compressive and

uniaxialtensile stress–strain curves for lonsdaleite and

diamond. The tensile strengths of lonsdaleite are 104.11

130.23 and 85.13 GPa forthe ½0 11 0, [2 1 1 0]and

[0 0 0 1] directions, respectively, which is agreement wit

Figure 1.The supercelland coordinate system forlonsdaleite and

diamond. (a) Rectangular solid supercell in the redefined orthorhom-

bic coordinate system for the [2 1 1 0], ½0 1 1 0, [0 0 0 1] orientations of

lonsdaleite.(b) Rectangularsolid supercellin the redefined ortho-

rhombic coordinate system for the ½1 1 2, ½1 1 0, [1 1 1] orientations of

diamond. (c) Cubic supercell in the redefined cubic coordinate system

for diamond with [1 0 0], [0 1 0], [0 0 1] orientations.

-0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4

-800

-700

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

-800

-700

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

[0110] orientation

[2110] orientation

[0001] orientation

Stress(GPa)

Strain(%)

-0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

300

[110] orientation

[111] orientation

Stress

Strain(%)

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

300

[100] orientation

a

b

Figure 2. Uniaxial compressiveand uniaxial tensilestress–strain

curves of (a) lonsdaleite and (b) diamond. The maximum compressive

strength of lonsdaleite is 727.16 GPa, which is 33.4% higher than the

corresponding value for diamond, 545.09 GPa.

230 L. Qingkun et al. / Scripta Materialia 65 (2011) 229–232

theoreticalcalculations[3]. Although this maximum

strength value 130.23 GPa is considerably less than the

highest value for diamond, 220 GPa in the [1 0 0] orienta-

tion of the cubic coordinate system [3,5,7] shown in the

Figure 1c,it is still higher than the tensile strength of

many other high-strength materials,such as 84.1 GPa

for C-BN [13],90.6 GPa for W-BN [3,13]and 63 GPa

[25] or 100–120 GPa [26] for carbon nanotubes. The result

further demonstrates the high strength of lonsdaleite.

The most attractive feature appears when lonsdaleite

was compressed. As can been seen from the stress–strain

relations in Figure 2a, the compressive strengths of lons-

daleiteare 727.16,516.33and 369.66 GPafor the

[0 0 0 1],[2 1 1 0]and ½0 11 0 directions,respectively,

which shows an excellent capability to resist compres-

sion.In particular,the maximum compressive strength

of lonsdaleite achieved, i.e. 727.16 GPa, is 33.4% higher

than the corresponding value for diamond, 545.09 GPa,

obtained from Figure 2b (in Ref.[4],this strength is

410–490 GPa). These results mean that lonsdaleite could

be the strongest naturally occurring substance on earth.

From all the results calculated above, it is clear that the

lonsdaleite not only shows higher compressive strength

and stiffness than diamond, but also shows bulk modulus

and tensile strength close to those of diamond. Further-

more,we also note from the literature that lonsdaleite

shows excellent hardness,higher than that of diamond

[3].All the above-mentioned mechanicalproperties are

listed in Table 1, which shows that almost all the conven-

tional static mechanical properties of lonsdaleite exceed,

or match, those of diamond. These mechanical properties

suggest that lonsdaleite could find application in many

areas of high-pressure research. For example, lonsdaleite

anvil-cells could replace diamond anvil-cells [27–29]to

generate more extreme pressures in order to compress

small pieces of material for scientific experiments.

To understand thoroughly the properties of lonsdale-

ite, we explored the origin of its outstanding mechanical

properties. We first analyzed the bond structure of lons-

daleite. From Figure 1, it can be seen that two different

carbon–carbon bond lengths appear in lonsdaleite. The

bond length along the [0 0 0 1]orientation,referred to

as the major bond, is 1.550 A˚, a little larger than the bond

length in diamond, 1.528 A˚. The bond length along other

orientations, referred to as the minor bond, is 1.526 A˚ for

lonsdaleite, which slightly less than that of diamond. In

addition,in lonsdaleite,the bond angles between the

bonds parallel to the [0 0 0 1] orientation and any other

bonds are 109.88°, the other bond angles are 109.06°, ve

close to 109.47° in diamond. Thos means that lonsdaleite

possessesfeaturestypical of sp3 bond interactions,

although infinitesimal differences exist between the bond

lengths and angles of lonsdaleite and diamond.

Furthermore,lonsdaleite also presentsa more or-

dered crystalstructure,in the following two respects.

(i) The [0 0 0 1] orientation is not only the close-packed

direction, but is also the crystallographic 3-fold symme-

try axis. This structure causes the packing density along

the [0 0 0 1]orientation to increase to 0.484 atom A˚ 1 ,

which is higher than the packing density of 0.398 atom

A˚ 1 along the [1 1 1]orientation in diamond.As a re-

sult, the higher packing density will increase the ability

to support an axialload along the [0 0 0 1]orientation.

(ii) The close-packed direction [0 0 0 1] is perpendicular

to slip plane (0001); at the same time, it is also parallel

to slip planes (2 1 1 0) and ð0 11 0Þ. This relationship be-

tween the close-packed direction and the slip planes

makes lonsdaleite fracture easily rather than slide along

any planes inclined to the [0 0 0 1] orientation.

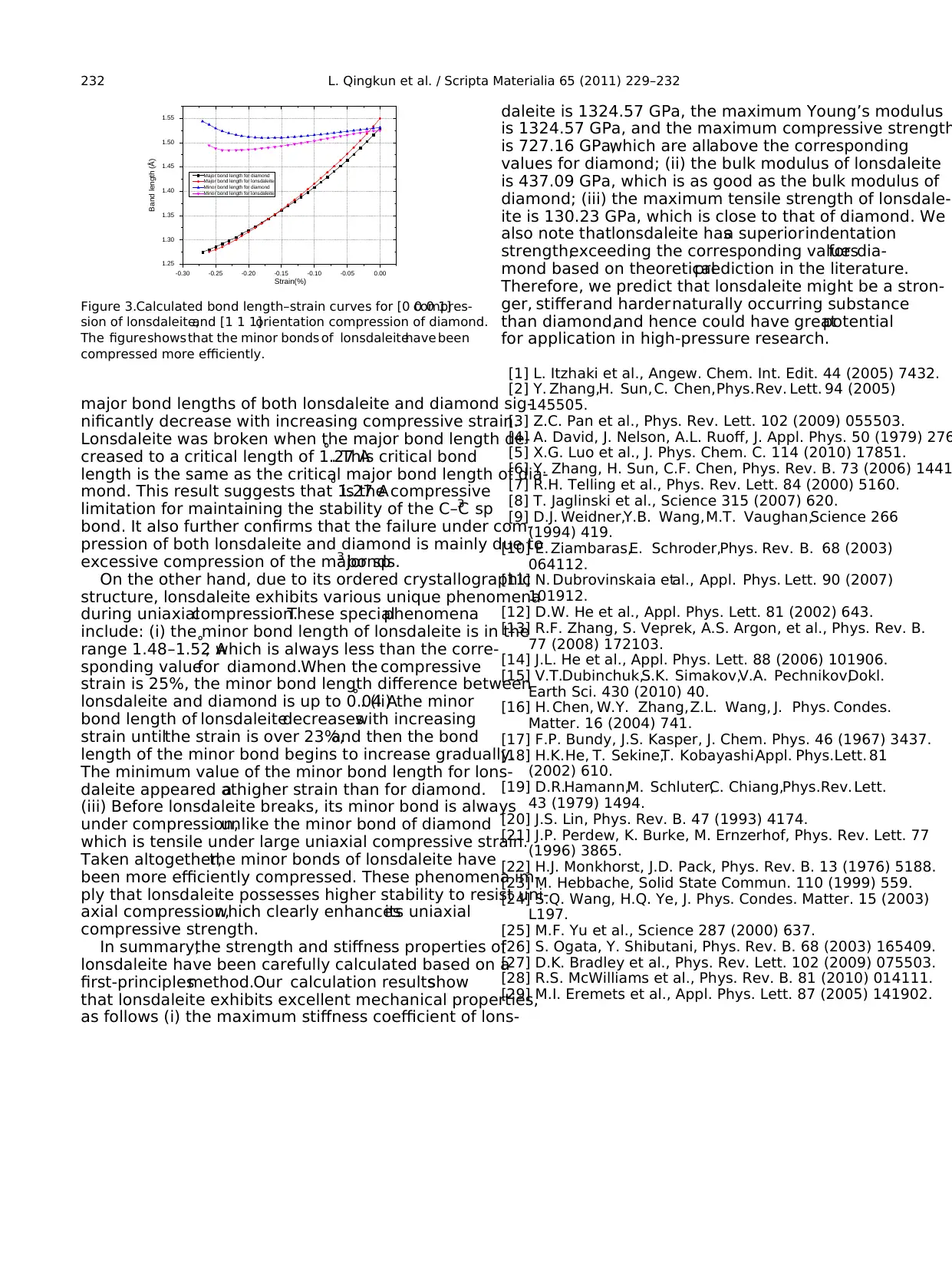

Therefore,the excellentmechanicalpropertiesof

lonsdaleite mainly originate from two sources:strong

sp3 bond interaction and a more ordered crystalstruc-

ture.In order to confirm this,the bond length–strain

relation of lonsdaleite under [0 0 0 1] orientation uniax-

ial compression—as well as bond length–strain relation

of diamond under [1 1 1]orientation uniaxialcompres-

sion—have been calculated, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows that lonsdaleite and diamond exhibit

similar bond length–strain relationships during the com-

pressive process. For convenience, we again refer to the

bonds along the [1 1 1] orientation of diamond as major

bonds, and other bonds as minor bonds. Obviously, the

Table 1.Stiffness, strength, and hardness properties of lonsdaleite and diamond.

Properties Lonsdaleite Diamond

Young’s modulus E½2 1 1 0¼ 1211:94 GPa

E½0 11 0

¼ 1215:67 GPa

E½0 0 0 1¼ 1324:57 GPa

E½1 0 0¼ 1068:89 GPa

E½1 1 0

¼ 1170:23 GPa

E½1 1 1¼ 1208:42 GPa

Stiffness matrix C 11= 1217.58 GPa, C22= 1221.33 GPa,

C 33= 1324.57GPa,

C 12= 83.02 GPa, C13= 1.20 GPa,

C 23= 0.97 Pa, C44= C55= 480.35 GPa,

C 66= 567.08 GPa

C 11= C22= 1181.79 GPa, C33= 1212.472 GPa,

C 44= C55= 519.5834 GPa,

C 66= 550.2648 GPa C12= 81.2605 GPa,

C 13= C23= 50.57905 GPa, C15= C 25= 43.39012 GPa,

C 34= 43.3901227 GPa,

Bulk modulus B0 = 437.09748 GPa B0 = 437.8766 GPa

Tensile strength r ½0 1 1 0

¼ 104:11 GPa

r ½2 1 1 0¼ 130:23 GPa

r ½0 0 0 1¼ 85:13 GPa

r ½1 0 0¼ 217:32 GPa

r ½1 1 0

¼ 121:09 GPa

r ½1 1 1¼ 86:01 GPa

Compressive strength r ½0 1 1 0

¼ 369:66 GPa

r ½2 1 1 0¼ 516:33 GPa

r ½0 0 0 1¼ 727:16 GPa

r ½1 0 0¼ 229:13 GPa

r ½1 1 0

¼ 487:45 GPa

r ½1 1 1¼ 545:09 GPa

Hardness H v[0001]= 152 GPa [3] H v[111]= 97 GPa[3]

L. Qingkun et al. / Scripta Materialia 65 (2011) 229–232 231

strength value 130.23 GPa is considerably less than the

highest value for diamond, 220 GPa in the [1 0 0] orienta-

tion of the cubic coordinate system [3,5,7] shown in the

Figure 1c,it is still higher than the tensile strength of

many other high-strength materials,such as 84.1 GPa

for C-BN [13],90.6 GPa for W-BN [3,13]and 63 GPa

[25] or 100–120 GPa [26] for carbon nanotubes. The result

further demonstrates the high strength of lonsdaleite.

The most attractive feature appears when lonsdaleite

was compressed. As can been seen from the stress–strain

relations in Figure 2a, the compressive strengths of lons-

daleiteare 727.16,516.33and 369.66 GPafor the

[0 0 0 1],[2 1 1 0]and ½0 11 0 directions,respectively,

which shows an excellent capability to resist compres-

sion.In particular,the maximum compressive strength

of lonsdaleite achieved, i.e. 727.16 GPa, is 33.4% higher

than the corresponding value for diamond, 545.09 GPa,

obtained from Figure 2b (in Ref.[4],this strength is

410–490 GPa). These results mean that lonsdaleite could

be the strongest naturally occurring substance on earth.

From all the results calculated above, it is clear that the

lonsdaleite not only shows higher compressive strength

and stiffness than diamond, but also shows bulk modulus

and tensile strength close to those of diamond. Further-

more,we also note from the literature that lonsdaleite

shows excellent hardness,higher than that of diamond

[3].All the above-mentioned mechanicalproperties are

listed in Table 1, which shows that almost all the conven-

tional static mechanical properties of lonsdaleite exceed,

or match, those of diamond. These mechanical properties

suggest that lonsdaleite could find application in many

areas of high-pressure research. For example, lonsdaleite

anvil-cells could replace diamond anvil-cells [27–29]to

generate more extreme pressures in order to compress

small pieces of material for scientific experiments.

To understand thoroughly the properties of lonsdale-

ite, we explored the origin of its outstanding mechanical

properties. We first analyzed the bond structure of lons-

daleite. From Figure 1, it can be seen that two different

carbon–carbon bond lengths appear in lonsdaleite. The

bond length along the [0 0 0 1]orientation,referred to

as the major bond, is 1.550 A˚, a little larger than the bond

length in diamond, 1.528 A˚. The bond length along other

orientations, referred to as the minor bond, is 1.526 A˚ for

lonsdaleite, which slightly less than that of diamond. In

addition,in lonsdaleite,the bond angles between the

bonds parallel to the [0 0 0 1] orientation and any other

bonds are 109.88°, the other bond angles are 109.06°, ve

close to 109.47° in diamond. Thos means that lonsdaleite

possessesfeaturestypical of sp3 bond interactions,

although infinitesimal differences exist between the bond

lengths and angles of lonsdaleite and diamond.

Furthermore,lonsdaleite also presentsa more or-

dered crystalstructure,in the following two respects.

(i) The [0 0 0 1] orientation is not only the close-packed

direction, but is also the crystallographic 3-fold symme-

try axis. This structure causes the packing density along

the [0 0 0 1]orientation to increase to 0.484 atom A˚ 1 ,

which is higher than the packing density of 0.398 atom

A˚ 1 along the [1 1 1]orientation in diamond.As a re-

sult, the higher packing density will increase the ability

to support an axialload along the [0 0 0 1]orientation.

(ii) The close-packed direction [0 0 0 1] is perpendicular

to slip plane (0001); at the same time, it is also parallel

to slip planes (2 1 1 0) and ð0 11 0Þ. This relationship be-

tween the close-packed direction and the slip planes

makes lonsdaleite fracture easily rather than slide along

any planes inclined to the [0 0 0 1] orientation.

Therefore,the excellentmechanicalpropertiesof

lonsdaleite mainly originate from two sources:strong

sp3 bond interaction and a more ordered crystalstruc-

ture.In order to confirm this,the bond length–strain

relation of lonsdaleite under [0 0 0 1] orientation uniax-

ial compression—as well as bond length–strain relation

of diamond under [1 1 1]orientation uniaxialcompres-

sion—have been calculated, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows that lonsdaleite and diamond exhibit

similar bond length–strain relationships during the com-

pressive process. For convenience, we again refer to the

bonds along the [1 1 1] orientation of diamond as major

bonds, and other bonds as minor bonds. Obviously, the

Table 1.Stiffness, strength, and hardness properties of lonsdaleite and diamond.

Properties Lonsdaleite Diamond

Young’s modulus E½2 1 1 0¼ 1211:94 GPa

E½0 11 0

¼ 1215:67 GPa

E½0 0 0 1¼ 1324:57 GPa

E½1 0 0¼ 1068:89 GPa

E½1 1 0

¼ 1170:23 GPa

E½1 1 1¼ 1208:42 GPa

Stiffness matrix C 11= 1217.58 GPa, C22= 1221.33 GPa,

C 33= 1324.57GPa,

C 12= 83.02 GPa, C13= 1.20 GPa,

C 23= 0.97 Pa, C44= C55= 480.35 GPa,

C 66= 567.08 GPa

C 11= C22= 1181.79 GPa, C33= 1212.472 GPa,

C 44= C55= 519.5834 GPa,

C 66= 550.2648 GPa C12= 81.2605 GPa,

C 13= C23= 50.57905 GPa, C15= C 25= 43.39012 GPa,

C 34= 43.3901227 GPa,

Bulk modulus B0 = 437.09748 GPa B0 = 437.8766 GPa

Tensile strength r ½0 1 1 0

¼ 104:11 GPa

r ½2 1 1 0¼ 130:23 GPa

r ½0 0 0 1¼ 85:13 GPa

r ½1 0 0¼ 217:32 GPa

r ½1 1 0

¼ 121:09 GPa

r ½1 1 1¼ 86:01 GPa

Compressive strength r ½0 1 1 0

¼ 369:66 GPa

r ½2 1 1 0¼ 516:33 GPa

r ½0 0 0 1¼ 727:16 GPa

r ½1 0 0¼ 229:13 GPa

r ½1 1 0

¼ 487:45 GPa

r ½1 1 1¼ 545:09 GPa

Hardness H v[0001]= 152 GPa [3] H v[111]= 97 GPa[3]

L. Qingkun et al. / Scripta Materialia 65 (2011) 229–232 231

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

major bond lengths of both lonsdaleite and diamond sig-

nificantly decrease with increasing compressive strain.

Lonsdaleite was broken when the major bond length de-

creased to a critical length of 1.27 A˚. This critical bond

length is the same as the critical major bond length of dia-

mond. This result suggests that 1.27 A˚ is the compressive

limitation for maintaining the stability of the C–C sp3

bond. It also further confirms that the failure under com-

pression of both lonsdaleite and diamond is mainly due to

excessive compression of the major sp3 bonds.

On the other hand, due to its ordered crystallographic

structure, lonsdaleite exhibits various unique phenomena

during uniaxialcompression.These specialphenomena

include: (i) the minor bond length of lonsdaleite is in the

range 1.48–1.52 A˚, which is always less than the corre-

sponding valuefor diamond.When the compressive

strain is 25%, the minor bond length difference between

lonsdaleite and diamond is up to 0.04 A˚. (ii) the minor

bond length of lonsdaleitedecreaseswith increasing

strain untilthe strain is over 23%,and then the bond

length of the minor bond begins to increase gradually.

The minimum value of the minor bond length for lons-

daleite appeared ata higher strain than for diamond.

(iii) Before lonsdaleite breaks, its minor bond is always

under compression,unlike the minor bond of diamond

which is tensile under large uniaxial compressive strain.

Taken altogether,the minor bonds of lonsdaleite have

been more efficiently compressed. These phenomena im-

ply that lonsdaleite possesses higher stability to resist uni-

axial compression,which clearly enhancesits uniaxial

compressive strength.

In summary,the strength and stiffness properties of

lonsdaleite have been carefully calculated based on a

first-principlesmethod.Our calculation resultsshow

that lonsdaleite exhibits excellent mechanical properties,

as follows (i) the maximum stiffness coefficient of lons-

daleite is 1324.57 GPa, the maximum Young’s modulus

is 1324.57 GPa, and the maximum compressive strength

is 727.16 GPa,which are allabove the corresponding

values for diamond; (ii) the bulk modulus of lonsdaleite

is 437.09 GPa, which is as good as the bulk modulus of

diamond; (iii) the maximum tensile strength of lonsdale-

ite is 130.23 GPa, which is close to that of diamond. We

also note thatlonsdaleite hasa superiorindentation

strength,exceeding the corresponding valuesfor dia-

mond based on theoreticalprediction in the literature.

Therefore, we predict that lonsdaleite might be a stron-

ger, stifferand hardernaturally occurring substance

than diamond,and hence could have greatpotential

for application in high-pressure research.

[1] L. Itzhaki et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 44 (2005) 7432.

[2] Y. Zhang,H. Sun, C. Chen,Phys.Rev. Lett. 94 (2005)

145505.

[3] Z.C. Pan et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 102 (2009) 055503.

[4] A. David, J. Nelson, A.L. Ruoff, J. Appl. Phys. 50 (1979) 276

[5] X.G. Luo et al., J. Phys. Chem. C. 114 (2010) 17851.

[6] Y. Zhang, H. Sun, C.F. Chen, Phys. Rev. B. 73 (2006) 1441

[7] R.H. Telling et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 84 (2000) 5160.

[8] T. Jaglinski et al., Science 315 (2007) 620.

[9] D.J. Weidner,Y.B. Wang,M.T. Vaughan,Science 266

(1994) 419.

[10] E. Ziambaras,E. Schroder,Phys. Rev. B. 68 (2003)

064112.

[11] N. Dubrovinskaia etal., Appl. Phys. Lett. 90 (2007)

101912.

[12] D.W. He et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. 81 (2002) 643.

[13] R.F. Zhang, S. Veprek, A.S. Argon, et al., Phys. Rev. B.

77 (2008) 172103.

[14] J.L. He et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. 88 (2006) 101906.

[15] V.T.Dubinchuk,S.K. Simakov,V.A. Pechnikov,Dokl.

Earth Sci. 430 (2010) 40.

[16] H. Chen, W.Y. Zhang,Z.L. Wang, J. Phys. Condes.

Matter. 16 (2004) 741.

[17] F.P. Bundy, J.S. Kasper, J. Chem. Phys. 46 (1967) 3437.

[18] H.K.He, T. Sekine,T. Kobayashi,Appl. Phys.Lett. 81

(2002) 610.

[19] D.R.Hamann,M. Schluter,C. Chiang,Phys.Rev. Lett.

43 (1979) 1494.

[20] J.S. Lin, Phys. Rev. B. 47 (1993) 4174.

[21] J.P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzerhof, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77

(1996) 3865.

[22] H.J. Monkhorst, J.D. Pack, Phys. Rev. B. 13 (1976) 5188.

[23] M. Hebbache, Solid State Commun. 110 (1999) 559.

[24] S.Q. Wang, H.Q. Ye, J. Phys. Condes. Matter. 15 (2003)

L197.

[25] M.F. Yu et al., Science 287 (2000) 637.

[26] S. Ogata, Y. Shibutani, Phys. Rev. B. 68 (2003) 165409.

[27] D.K. Bradley et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 102 (2009) 075503.

[28] R.S. McWilliams et al., Phys. Rev. B. 81 (2010) 014111.

[29] M.I. Eremets et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. 87 (2005) 141902.

-0.30 -0.25 -0.20 -0.15 -0.10 -0.05 0.00

1.25

1.30

1.35

1.40

1.45

1.50

1.55

Band length (Å)

Strain(%)

Major bond length for diamond

Major bond length for lonsdaleite

Minor bond length for diamond

Minor bond length for lonsdaleite

Figure 3.Calculated bond length–strain curves for [0 0 0 1]compres-

sion of lonsdaleite,and [1 1 1]orientation compression of diamond.

The figureshowsthat the minor bonds of lonsdaleitehave been

compressed more efficiently.

232 L. Qingkun et al. / Scripta Materialia 65 (2011) 229–232

nificantly decrease with increasing compressive strain.

Lonsdaleite was broken when the major bond length de-

creased to a critical length of 1.27 A˚. This critical bond

length is the same as the critical major bond length of dia-

mond. This result suggests that 1.27 A˚ is the compressive

limitation for maintaining the stability of the C–C sp3

bond. It also further confirms that the failure under com-

pression of both lonsdaleite and diamond is mainly due to

excessive compression of the major sp3 bonds.

On the other hand, due to its ordered crystallographic

structure, lonsdaleite exhibits various unique phenomena

during uniaxialcompression.These specialphenomena

include: (i) the minor bond length of lonsdaleite is in the

range 1.48–1.52 A˚, which is always less than the corre-

sponding valuefor diamond.When the compressive

strain is 25%, the minor bond length difference between

lonsdaleite and diamond is up to 0.04 A˚. (ii) the minor

bond length of lonsdaleitedecreaseswith increasing

strain untilthe strain is over 23%,and then the bond

length of the minor bond begins to increase gradually.

The minimum value of the minor bond length for lons-

daleite appeared ata higher strain than for diamond.

(iii) Before lonsdaleite breaks, its minor bond is always

under compression,unlike the minor bond of diamond

which is tensile under large uniaxial compressive strain.

Taken altogether,the minor bonds of lonsdaleite have

been more efficiently compressed. These phenomena im-

ply that lonsdaleite possesses higher stability to resist uni-

axial compression,which clearly enhancesits uniaxial

compressive strength.

In summary,the strength and stiffness properties of

lonsdaleite have been carefully calculated based on a

first-principlesmethod.Our calculation resultsshow

that lonsdaleite exhibits excellent mechanical properties,

as follows (i) the maximum stiffness coefficient of lons-

daleite is 1324.57 GPa, the maximum Young’s modulus

is 1324.57 GPa, and the maximum compressive strength

is 727.16 GPa,which are allabove the corresponding

values for diamond; (ii) the bulk modulus of lonsdaleite

is 437.09 GPa, which is as good as the bulk modulus of

diamond; (iii) the maximum tensile strength of lonsdale-

ite is 130.23 GPa, which is close to that of diamond. We

also note thatlonsdaleite hasa superiorindentation

strength,exceeding the corresponding valuesfor dia-

mond based on theoreticalprediction in the literature.

Therefore, we predict that lonsdaleite might be a stron-

ger, stifferand hardernaturally occurring substance

than diamond,and hence could have greatpotential

for application in high-pressure research.

[1] L. Itzhaki et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 44 (2005) 7432.

[2] Y. Zhang,H. Sun, C. Chen,Phys.Rev. Lett. 94 (2005)

145505.

[3] Z.C. Pan et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 102 (2009) 055503.

[4] A. David, J. Nelson, A.L. Ruoff, J. Appl. Phys. 50 (1979) 276

[5] X.G. Luo et al., J. Phys. Chem. C. 114 (2010) 17851.

[6] Y. Zhang, H. Sun, C.F. Chen, Phys. Rev. B. 73 (2006) 1441

[7] R.H. Telling et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 84 (2000) 5160.

[8] T. Jaglinski et al., Science 315 (2007) 620.

[9] D.J. Weidner,Y.B. Wang,M.T. Vaughan,Science 266

(1994) 419.

[10] E. Ziambaras,E. Schroder,Phys. Rev. B. 68 (2003)

064112.

[11] N. Dubrovinskaia etal., Appl. Phys. Lett. 90 (2007)

101912.

[12] D.W. He et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. 81 (2002) 643.

[13] R.F. Zhang, S. Veprek, A.S. Argon, et al., Phys. Rev. B.

77 (2008) 172103.

[14] J.L. He et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. 88 (2006) 101906.

[15] V.T.Dubinchuk,S.K. Simakov,V.A. Pechnikov,Dokl.

Earth Sci. 430 (2010) 40.

[16] H. Chen, W.Y. Zhang,Z.L. Wang, J. Phys. Condes.

Matter. 16 (2004) 741.

[17] F.P. Bundy, J.S. Kasper, J. Chem. Phys. 46 (1967) 3437.

[18] H.K.He, T. Sekine,T. Kobayashi,Appl. Phys.Lett. 81

(2002) 610.

[19] D.R.Hamann,M. Schluter,C. Chiang,Phys.Rev. Lett.

43 (1979) 1494.

[20] J.S. Lin, Phys. Rev. B. 47 (1993) 4174.

[21] J.P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzerhof, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77

(1996) 3865.

[22] H.J. Monkhorst, J.D. Pack, Phys. Rev. B. 13 (1976) 5188.

[23] M. Hebbache, Solid State Commun. 110 (1999) 559.

[24] S.Q. Wang, H.Q. Ye, J. Phys. Condes. Matter. 15 (2003)

L197.

[25] M.F. Yu et al., Science 287 (2000) 637.

[26] S. Ogata, Y. Shibutani, Phys. Rev. B. 68 (2003) 165409.

[27] D.K. Bradley et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 102 (2009) 075503.

[28] R.S. McWilliams et al., Phys. Rev. B. 81 (2010) 014111.

[29] M.I. Eremets et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. 87 (2005) 141902.

-0.30 -0.25 -0.20 -0.15 -0.10 -0.05 0.00

1.25

1.30

1.35

1.40

1.45

1.50

1.55

Band length (Å)

Strain(%)

Major bond length for diamond

Major bond length for lonsdaleite

Minor bond length for diamond

Minor bond length for lonsdaleite

Figure 3.Calculated bond length–strain curves for [0 0 0 1]compres-

sion of lonsdaleite,and [1 1 1]orientation compression of diamond.

The figureshowsthat the minor bonds of lonsdaleitehave been

compressed more efficiently.

232 L. Qingkun et al. / Scripta Materialia 65 (2011) 229–232

1 out of 4

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.