Identifying barriers to evidence-based practice adoption: A focus group study

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/15

|7

|6485

|260

AI Summary

This study examines nurse’s views relative to the adoption of EBP in a specific community hospital setting. Themes identified included institutional and/or cultural barriers, lack of knowledge, lack of motivation, time management, physician and patient factors, and limited access to up-to-date user-friendly technology and computer systems.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

www.sciedu.ca/cns Clinical Nursing Studies 2015, Vol. 3, No. 2

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Identifying barriers to evidence-based practice

adoption:A focus group study

LeilaniTacia∗1, Karen Biskupski1, Alfred Pheley1, Rebecca H. Lehto2

1Allegiance Health System, Jackson, MI, United States

2Michigan State University College of Nursing, East Lansing, MI, United States

Received:January 3, 2015 Accepted:January 28, 2015 Online Published:February 4, 2015

DOI: 10.5430/cns.v3n2p90 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/cns.v3n2p90

Abstract

Objectives: The promotion of evidence-based practice (EBP) to ensure that the best scientific evidence, clinician expertise, and

patient advocacy are used in health care delivery is an important leadership role of advanced practice nurses. While there has

been much progress in advancing EBP, there are many hospital systems in the United States and other parts of the world that

have yet to integrate an EBP framework. A focus group study was conducted to examine nurse’s views relative to the adoption

of EBP in a specific community hospital setting.

Methods: Design: A focus group design was used. Setting: A Midwestern United States rural community hospital. Sample:

Four nurse practitioners, three nurse administrators/managers, and eleven inpatient direct care nurses.Three focus groups were

conducted. Data were analyzed using qualitative methodology.

Results: Themes identified included institutional and/or cultural barriers, lack of knowledge, lack of motivation, time manage-

ment, physician and patient factors, and limited access to up-to-date user-friendly technology and computer systems.

Conclusions: Engaging a participatory approach, findings provide strategy to consider when developing programs to expose

nurses to EBP and for the translation of current standards into clinical practice. Building infrastructure to sustain and support

EBP via leadership; time provision; access and support for continuing education; and collaborative integration of team members

will guide the development of clinical environments that promote EBP.

Key Words:Clinical nurse specialist, Evidence-based practice, Community hospital

1 Introduction

Use of evidence-based practices ensures the best scientific

evidence, clinician expertise, and patient advocacy are used

in health care delivery. Promotion of evidence-based prac-

tice (EBP) is an important leadership role of clinical nurse

specialists.[1–3] Practicing nurses must be prepared to for-

mulate questions, critically assess practice, and evaluate re-

search, clinical guidelines, and levels of evidence. [4] De-

spite substantive development and systems in place to pro-

mote EBP, many hospital systems internationally have yet

to integrate an evidence-based model of care. [1, 5] Barriers

to successful implementation arise from multiple factors in-

cluding varying education and clinical experiences of nurs-

ing staff, and a lack of understanding about its’ importance

to optimal high quality patient care.[3, 6, 7]

Focus group research allows researchers to generate data

that provides insight into the unique personal experiences

and views of participants. [8–10] Such data can be used by

∗Correspondence: Leilani Tacia; Email: leilani.tacia@allegiancehealth.org; Address: Allegiance Health System, Jackson, MI, United States.

90 ISSN 2324-7940 E-ISSN 2324-7959

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Identifying barriers to evidence-based practice

adoption:A focus group study

LeilaniTacia∗1, Karen Biskupski1, Alfred Pheley1, Rebecca H. Lehto2

1Allegiance Health System, Jackson, MI, United States

2Michigan State University College of Nursing, East Lansing, MI, United States

Received:January 3, 2015 Accepted:January 28, 2015 Online Published:February 4, 2015

DOI: 10.5430/cns.v3n2p90 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/cns.v3n2p90

Abstract

Objectives: The promotion of evidence-based practice (EBP) to ensure that the best scientific evidence, clinician expertise, and

patient advocacy are used in health care delivery is an important leadership role of advanced practice nurses. While there has

been much progress in advancing EBP, there are many hospital systems in the United States and other parts of the world that

have yet to integrate an EBP framework. A focus group study was conducted to examine nurse’s views relative to the adoption

of EBP in a specific community hospital setting.

Methods: Design: A focus group design was used. Setting: A Midwestern United States rural community hospital. Sample:

Four nurse practitioners, three nurse administrators/managers, and eleven inpatient direct care nurses.Three focus groups were

conducted. Data were analyzed using qualitative methodology.

Results: Themes identified included institutional and/or cultural barriers, lack of knowledge, lack of motivation, time manage-

ment, physician and patient factors, and limited access to up-to-date user-friendly technology and computer systems.

Conclusions: Engaging a participatory approach, findings provide strategy to consider when developing programs to expose

nurses to EBP and for the translation of current standards into clinical practice. Building infrastructure to sustain and support

EBP via leadership; time provision; access and support for continuing education; and collaborative integration of team members

will guide the development of clinical environments that promote EBP.

Key Words:Clinical nurse specialist, Evidence-based practice, Community hospital

1 Introduction

Use of evidence-based practices ensures the best scientific

evidence, clinician expertise, and patient advocacy are used

in health care delivery. Promotion of evidence-based prac-

tice (EBP) is an important leadership role of clinical nurse

specialists.[1–3] Practicing nurses must be prepared to for-

mulate questions, critically assess practice, and evaluate re-

search, clinical guidelines, and levels of evidence. [4] De-

spite substantive development and systems in place to pro-

mote EBP, many hospital systems internationally have yet

to integrate an evidence-based model of care. [1, 5] Barriers

to successful implementation arise from multiple factors in-

cluding varying education and clinical experiences of nurs-

ing staff, and a lack of understanding about its’ importance

to optimal high quality patient care.[3, 6, 7]

Focus group research allows researchers to generate data

that provides insight into the unique personal experiences

and views of participants. [8–10] Such data can be used by

∗Correspondence: Leilani Tacia; Email: leilani.tacia@allegiancehealth.org; Address: Allegiance Health System, Jackson, MI, United States.

90 ISSN 2324-7940 E-ISSN 2324-7959

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

www.sciedu.ca/cns Clinical Nursing Studies 2015, Vol. 3, No. 2

clinical nurse specialists in the development of targeted

strategies to respond to particular problems that challenge

specific clinical settings.[8, 9] This focus group study exam-

ined nursing staff perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs regard-

ing the adoption of EBP in a community hospital system

recognized to be early in its transition to evidenced based

care.

1.1 Background and significance

Wider adoption of EBP is yet needed to improve quality,

safety, and promote effective care that can positively im-

pact patient outcomes. [2, 11–13] Sparked by several Institute

of Medicine reports published since 2001 focusing broadly

on healthcare quality and redesigning systems to ensure pa-

tients receive safe, effective, patient centered, timely, effi-

cient and equitable care, much progress has been made in

developing systems to support EBP.[13] However, only in the

past decade has EBP been incorporated into nursing curric-

ula, and many practicing nurses still lack knowledge about

implementation.[3] As a result, patients across the United

States and other parts of the world may still receive care that

is not based on current scientific evidence, including health

care that may be unnecessary or have negative effects.[14]

While there have been advancements, translation of re-

search into practice settings, incorporation of clinical prac-

tice guidelines to promote high quality care, and system-

atically changing institutional culture remain serious pub-

lic health issues for some hospital systems. [5, 15] It is rec-

ognized that lag time from translating evidence to practice

can take anywhere from eight to thirty years. [16, 17] Several

well-accepted inpatient practice guidelines exist for pain,

diabetes care, wound healing, and heart failure manage-

ment, and have been incorporated into the medical record

and into patient care. Patients experiencing these condi-

tions, however, may still experience preventable adverse

outcomes.[2, 11]

Previous reports of attitudes and knowledge of nurses to-

wards EBP demonstrates a wide range of awareness, re-

sources, and implementation.[17] While nurses may be pos-

itive about EBP, this does not translate into implementa-

tion.[18, 19] Studies suggest that consistent educational pro-

grams may help build positive attitudes and knowledge, and

nursing leadership is critical to promoting a positive EBP

climate.[7, 12, 17, 20]

The application of EBP can be challenging and requires col-

laboration and teamwork among nurses practicing in various

roles.[13, 19] While organizational culture is critical to ensur-

ing that a best practice climate is fostered, successful EBP

requires more than positive leadership.[21] At the foundation

is a well-prepared workforce that moves the institution for-

ward.[17] Nurses in advanced roles are recognized as critical

to leading a cultural shift that promotes EBP in the hospi-

tal environment and across the scope of health care inter-

nationally.[7] A recognized participatory approach to facili-

tate change and buy-in is to involve the stakeholders such as

practicing nurses in the early development of a project. [19]

Therefore, the focus group methodology was considered a

possible tool for better understanding the challenges of EBP

implementation in a specific practice environment.

1.2 Theoreticalframework

The Advancing Research and Clinical Practice through

Close Collaboration (ARCC) Model was developed to im-

prove integration of research and clinical practices in acute

and community health care settings. [22] The AARC model

was conceptualized as a broad systematic strategy incorpo-

rating EBP mentorship, reliable information, and support to

overcome institutional barriers. [22] The model further em-

phasizes the importance of change. An important step to

EBP adoption is to conduct an organizational assessment

of implementation readiness for personal and institutional

change.[23]

The purpose of the study was to examine nurses’ per-

ceptions, attitudes, and beliefs about EBP using focus

groups. While limited clinical research has used focus group

methodology, the established approach permits participants

with shared background to discuss perspectives in a format

where they can exchange meaningful information that leads

to common themes. [8, 24, 25] Study objectives included to:

1) gain an understanding of EBP perceptions based on prac-

tice environments and educational backgrounds; 2) explore

specific barriers to EBP implementation unique to the spe-

cific cultural paradigm; and 3) elicit recommendations to

enhance promotion of EBP. Such appraisal of nurse percep-

tions and experiences will be instrumental in guiding tar-

geted strategies to promote best practice in the respective

hospital culture. Further, the approach may be applicable to

clinical nurse specialists promoting such progress in other

unique practice settings.

2 Methods

The hospital Institutional Review Board approved all study

procedures prior to the beginning of participant recruitment

and study implementation.

2.1 Setting and sample

Three focus groups were conducted, coordinated by a site

clinical nurse specialist with support from an academic part-

nership with a local university that has strong community

involvement. The aim of the academic partnership was to

assist with promotion and adoption of an evidenced-based

practice culture and to foster nurse-led clinical research.

Study participants were recruited from a community hos-

pital located in the Mid-western region of the United States.

Aiming to maximize variation in perspectives and views, in-

cluded in the study were registered nursing staff with ad-

Published by Sciedu Press 91

clinical nurse specialists in the development of targeted

strategies to respond to particular problems that challenge

specific clinical settings.[8, 9] This focus group study exam-

ined nursing staff perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs regard-

ing the adoption of EBP in a community hospital system

recognized to be early in its transition to evidenced based

care.

1.1 Background and significance

Wider adoption of EBP is yet needed to improve quality,

safety, and promote effective care that can positively im-

pact patient outcomes. [2, 11–13] Sparked by several Institute

of Medicine reports published since 2001 focusing broadly

on healthcare quality and redesigning systems to ensure pa-

tients receive safe, effective, patient centered, timely, effi-

cient and equitable care, much progress has been made in

developing systems to support EBP.[13] However, only in the

past decade has EBP been incorporated into nursing curric-

ula, and many practicing nurses still lack knowledge about

implementation.[3] As a result, patients across the United

States and other parts of the world may still receive care that

is not based on current scientific evidence, including health

care that may be unnecessary or have negative effects.[14]

While there have been advancements, translation of re-

search into practice settings, incorporation of clinical prac-

tice guidelines to promote high quality care, and system-

atically changing institutional culture remain serious pub-

lic health issues for some hospital systems. [5, 15] It is rec-

ognized that lag time from translating evidence to practice

can take anywhere from eight to thirty years. [16, 17] Several

well-accepted inpatient practice guidelines exist for pain,

diabetes care, wound healing, and heart failure manage-

ment, and have been incorporated into the medical record

and into patient care. Patients experiencing these condi-

tions, however, may still experience preventable adverse

outcomes.[2, 11]

Previous reports of attitudes and knowledge of nurses to-

wards EBP demonstrates a wide range of awareness, re-

sources, and implementation.[17] While nurses may be pos-

itive about EBP, this does not translate into implementa-

tion.[18, 19] Studies suggest that consistent educational pro-

grams may help build positive attitudes and knowledge, and

nursing leadership is critical to promoting a positive EBP

climate.[7, 12, 17, 20]

The application of EBP can be challenging and requires col-

laboration and teamwork among nurses practicing in various

roles.[13, 19] While organizational culture is critical to ensur-

ing that a best practice climate is fostered, successful EBP

requires more than positive leadership.[21] At the foundation

is a well-prepared workforce that moves the institution for-

ward.[17] Nurses in advanced roles are recognized as critical

to leading a cultural shift that promotes EBP in the hospi-

tal environment and across the scope of health care inter-

nationally.[7] A recognized participatory approach to facili-

tate change and buy-in is to involve the stakeholders such as

practicing nurses in the early development of a project. [19]

Therefore, the focus group methodology was considered a

possible tool for better understanding the challenges of EBP

implementation in a specific practice environment.

1.2 Theoreticalframework

The Advancing Research and Clinical Practice through

Close Collaboration (ARCC) Model was developed to im-

prove integration of research and clinical practices in acute

and community health care settings. [22] The AARC model

was conceptualized as a broad systematic strategy incorpo-

rating EBP mentorship, reliable information, and support to

overcome institutional barriers. [22] The model further em-

phasizes the importance of change. An important step to

EBP adoption is to conduct an organizational assessment

of implementation readiness for personal and institutional

change.[23]

The purpose of the study was to examine nurses’ per-

ceptions, attitudes, and beliefs about EBP using focus

groups. While limited clinical research has used focus group

methodology, the established approach permits participants

with shared background to discuss perspectives in a format

where they can exchange meaningful information that leads

to common themes. [8, 24, 25] Study objectives included to:

1) gain an understanding of EBP perceptions based on prac-

tice environments and educational backgrounds; 2) explore

specific barriers to EBP implementation unique to the spe-

cific cultural paradigm; and 3) elicit recommendations to

enhance promotion of EBP. Such appraisal of nurse percep-

tions and experiences will be instrumental in guiding tar-

geted strategies to promote best practice in the respective

hospital culture. Further, the approach may be applicable to

clinical nurse specialists promoting such progress in other

unique practice settings.

2 Methods

The hospital Institutional Review Board approved all study

procedures prior to the beginning of participant recruitment

and study implementation.

2.1 Setting and sample

Three focus groups were conducted, coordinated by a site

clinical nurse specialist with support from an academic part-

nership with a local university that has strong community

involvement. The aim of the academic partnership was to

assist with promotion and adoption of an evidenced-based

practice culture and to foster nurse-led clinical research.

Study participants were recruited from a community hos-

pital located in the Mid-western region of the United States.

Aiming to maximize variation in perspectives and views, in-

cluded in the study were registered nursing staff with ad-

Published by Sciedu Press 91

www.sciedu.ca/cns Clinical Nursing Studies 2015, Vol. 3, No. 2

vanced practice roles (such as nurse practitioners, clinical

nurse specialists), administrative managerial roles, and in-

patient direct care providers. Participants in each focus

group coincided with the proportion of associated numbers

of registered nursing personnel in the respective practice

categories at the identified institution. Thus, there were

fewer advanced practice nurses and management nurses

who were included compared to numbers of nurses who

provided direct bedside care. The three focus groups con-

sisted of registered nurses in the following roles: advanced

practice nurses (APN) (n = 4), nursing managers and/or ad-

ministrators (n = 3), and inpatient direct care nurses (n =

11). The APN’s were masters’ degree prepared, the admin-

istrator/managers group were bachelors’ degree prepared,

and 9 of the 11 inpatient direct care nurses (82%) were as-

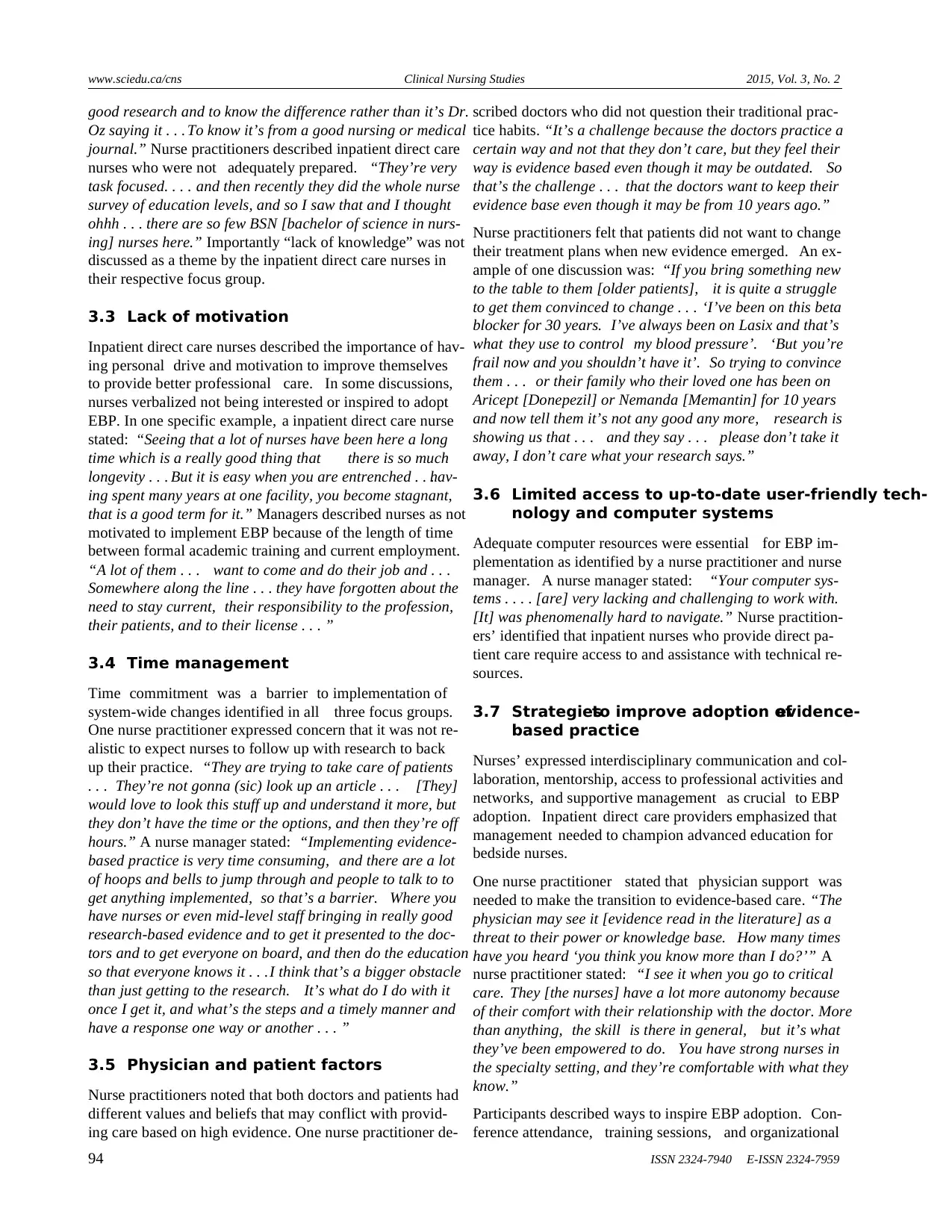

sociate degree prepared. Table 1 provides sample demo-

graphic data.

Table 1: Focus group nurse participant characteristics

Advanced practice nurses (N = 4) Administrators/Managers (N = 3) Staff nurses (N = 11)

Age range (Median; Range) M = 50; 37-62 years M = 45; 27-57 years M = 36; 20-55 years

Years of nursing experience (Mean

± Standard deviation; Range) 26.75 ± 10.69; 16-41 years 18.0 ± 19.16; 5-40 years 6.45 ± 5.57; 1-19 years

Sex N (%) Female = 3 (75%) Female = 3 (100%) Female = 9 (82%)

Work Environment N (%)

Inpatient N = 0 N = 3 (100%) N = 11 (100%)

Outpatient N = 3 (75%) N = 0 N = 0

Both N = 1 (25%) N = 0 N = 0

Shift Worked N (%)

Days N = 3 (75%) N = 3 (100%) N = 6 (55%)

Nights N = 0 N = 0 N = 5 (45%)

Variable (Days/evenings) N = 1 (25%) N = 0 N = 0

Education Background N (%)

Associates N = 0 N = 0 N = 9 (82%)

Bachelor of Science N = 0 N = 3 (100%) N = 2 (18%)

Master of Science N = 4 (100%) N = 0 N = 0

2.2 Data collection

Nurses were recruited for specific groups based on job title

and work roles via email and flyer distribution. Established

focus group rules included the voluntary nature of participa-

tion and use of audio recording. In addition, group conduct

rules including the importance of strict confidentiality, re-

spect for alternative viewpoints, the need to ensure that all

participants had the chance to share perspectives, and use

of first names only during discussions were incorporated.

Each focus group was conducted in the same conference

room and informed consent was obtained from all partici-

pants. Each focus group was completed within a two-hour

time frame. Refreshments were provided and participants

were free to leave early, as needed. A doctoral prepared

nurse scientist familiar with focus group methodology who

was aligned with the academic partnership institution mod-

erated each session using the pre-established questions and

probes (see Table 2). Also participating in focus group co-

ordination and conduct were the site principal investigators,

a master’s degree prepared clinical nurse specialist and a

bachelor’s prepared nurse manager. While the nurse scien-

tist who moderated the focus groups did not know the partic-

ipants, the site principal investigators had previous personal

interactions with some participants working in the same or-

ganization. It is understood in qualitative methodology that

researchers bring inherent bias based on their personal view-

points and background into the study dynamic. In this line,

site investigators worked to facilitate a nonthreatening sup-

portive atmosphere and reflective dialogue among the fo-

cus group participants while avoiding interjecting personal

opinions and interpretation.

92 ISSN 2324-7940 E-ISSN 2324-7959

vanced practice roles (such as nurse practitioners, clinical

nurse specialists), administrative managerial roles, and in-

patient direct care providers. Participants in each focus

group coincided with the proportion of associated numbers

of registered nursing personnel in the respective practice

categories at the identified institution. Thus, there were

fewer advanced practice nurses and management nurses

who were included compared to numbers of nurses who

provided direct bedside care. The three focus groups con-

sisted of registered nurses in the following roles: advanced

practice nurses (APN) (n = 4), nursing managers and/or ad-

ministrators (n = 3), and inpatient direct care nurses (n =

11). The APN’s were masters’ degree prepared, the admin-

istrator/managers group were bachelors’ degree prepared,

and 9 of the 11 inpatient direct care nurses (82%) were as-

sociate degree prepared. Table 1 provides sample demo-

graphic data.

Table 1: Focus group nurse participant characteristics

Advanced practice nurses (N = 4) Administrators/Managers (N = 3) Staff nurses (N = 11)

Age range (Median; Range) M = 50; 37-62 years M = 45; 27-57 years M = 36; 20-55 years

Years of nursing experience (Mean

± Standard deviation; Range) 26.75 ± 10.69; 16-41 years 18.0 ± 19.16; 5-40 years 6.45 ± 5.57; 1-19 years

Sex N (%) Female = 3 (75%) Female = 3 (100%) Female = 9 (82%)

Work Environment N (%)

Inpatient N = 0 N = 3 (100%) N = 11 (100%)

Outpatient N = 3 (75%) N = 0 N = 0

Both N = 1 (25%) N = 0 N = 0

Shift Worked N (%)

Days N = 3 (75%) N = 3 (100%) N = 6 (55%)

Nights N = 0 N = 0 N = 5 (45%)

Variable (Days/evenings) N = 1 (25%) N = 0 N = 0

Education Background N (%)

Associates N = 0 N = 0 N = 9 (82%)

Bachelor of Science N = 0 N = 3 (100%) N = 2 (18%)

Master of Science N = 4 (100%) N = 0 N = 0

2.2 Data collection

Nurses were recruited for specific groups based on job title

and work roles via email and flyer distribution. Established

focus group rules included the voluntary nature of participa-

tion and use of audio recording. In addition, group conduct

rules including the importance of strict confidentiality, re-

spect for alternative viewpoints, the need to ensure that all

participants had the chance to share perspectives, and use

of first names only during discussions were incorporated.

Each focus group was conducted in the same conference

room and informed consent was obtained from all partici-

pants. Each focus group was completed within a two-hour

time frame. Refreshments were provided and participants

were free to leave early, as needed. A doctoral prepared

nurse scientist familiar with focus group methodology who

was aligned with the academic partnership institution mod-

erated each session using the pre-established questions and

probes (see Table 2). Also participating in focus group co-

ordination and conduct were the site principal investigators,

a master’s degree prepared clinical nurse specialist and a

bachelor’s prepared nurse manager. While the nurse scien-

tist who moderated the focus groups did not know the partic-

ipants, the site principal investigators had previous personal

interactions with some participants working in the same or-

ganization. It is understood in qualitative methodology that

researchers bring inherent bias based on their personal view-

points and background into the study dynamic. In this line,

site investigators worked to facilitate a nonthreatening sup-

portive atmosphere and reflective dialogue among the fo-

cus group participants while avoiding interjecting personal

opinions and interpretation.

92 ISSN 2324-7940 E-ISSN 2324-7959

www.sciedu.ca/cns Clinical Nursing Studies 2015, Vol. 3, No. 2

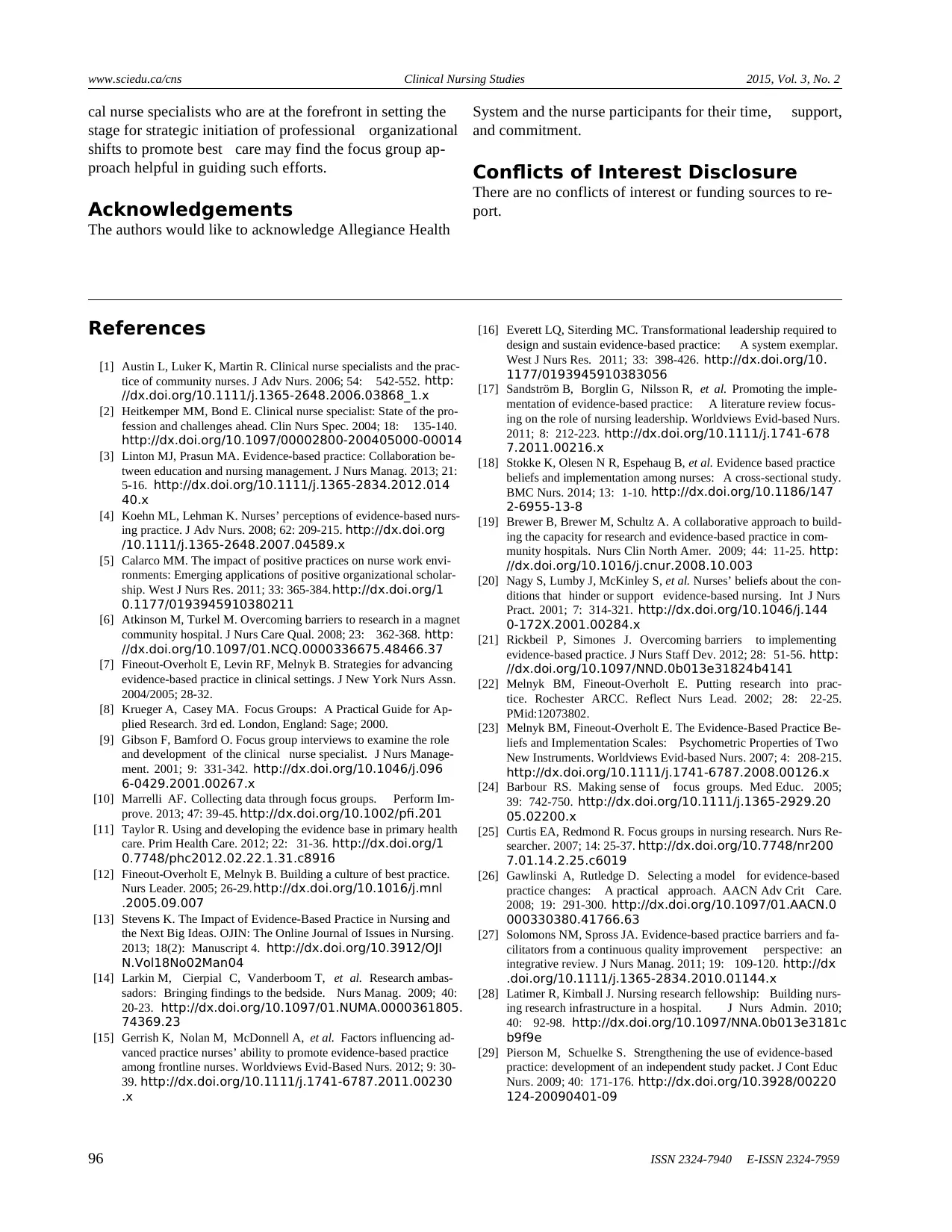

Table 2: Examples of focus group questions and sub-probes

Focus Group Content Questions Sub-Probes (If not mentioned, ask)

Research Objective 1 Where did you first learn about

evidence-based practice?

1. Education program

2. Previous work setting and experience

Research Objective 2

What barriers have you encountered

related to implementing

evidence-based practice?

1. Do you feel that evidence- based practice is supported in your work setting?

2. What are some examples?

3. Are there any patient-related factors that are barriers (“Can you tell us more if

‘yes’ only response)?

4. Are there any staff-related factors that are barriers (“Can you tell us more if

‘yes’ only response”)?

5. Do you have access to evidence-based practice resources? (“Can you tell us

more if ‘yes’ only response”).

6. Do you have sufficient knowledge of evidence-based practice to incorporate it

into your practice (“Can you tell us more if ‘yes’ only response”)?

7. How do you know whether evidence- based practice is effective?

Research Objective 3

What recommendations do you

have relative to promoting

evidence-based practice in your

work setting?

1. What types of resources would you need to foster evidence- based practice in

your work environment?

2. What are things the institution could do to foster evidence-based practice in

your work environment?

3. What are things you and your co-workers could do to foster evidence-based

practice in your work environment?

2.3 Data analysis

Using procedures established by Krueger and Casey[8, 25] the

tapes were transcribed verbatim. Transcriptions were re-

viewed for accuracy and independently examined by the in-

vestigators. Analysis was applied towards the recognition

and modification of major themes and sub-themes. [8, 24, 25]

Data were compared across the three focus group encoun-

ters with focused attention to group similarities and differ-

ences. Content categories were developed, and agreement

related to content was obtained following the two indepen-

dent reviews and follow-up discussions among study inves-

tigators.

3 Results

Six factors were identified as challenges to EBP adoption:

institutional and/or cultural barriers, lack of knowledge, lack

of motivation, time management, physician and patient fac-

tors, and limited access to up to date, user-friendly technol-

ogy and computer systems. Nurses also discussed strategies

to improve adoption of EBP. Specific examples of the major

themes are provided in the following paragraphs.

3.1 Institutionaland/or culturalbarriers

Members of the three groups identified cultural factors

within the institution and the need to promote system-wide

hospital change as being significant barriers. One nurse

practitioner described the culture as being one that did not

demand best practice from the nurses. “I think in places that

back up their practice with evidence, there’s this culture of

learning and of ‘we want it to be the most current and up

to date’. That’s when you hear guys walking around hall-

ways and quoting [EBP from] studies, and we don’t have

that here so there has to be a culture change.”

An inpatient direct care nurse described that the importance

of professional advancement among nurses was undermined

because of cultural attitudes of the hospital system. “I . . .

wanted my specialty in oncology and my preceptor said,

why? You’re not going to get any more money . . .You know

[named hospital] doesn’t care if you’ve got that. I said I’m

doing it for me. I want to explain to my patient why the OCN

[oncology certified nurse] is behind my name.”

Nurse practitioners discussed traditional norms and a strong

tendency to fall back on habits rather then base practice on

current evidence. One nurse practitioner stated, “When you

bring it [EBP] up to the nurses, if you ask them why you

do it this way . . . They say it’s because we’ve always done

it. When you look at the whole, it’s more of a process is-

sue . . . because that’s how we’ve always done it than an

actual task itself.” Another nurse practitioner stated, “There

are some things we do that we blatantly say, ‘there is no ev-

idence for this, we’re just going to do it.’ Some of that is

because ‘guys’ are a little stodgy and stuck in their way and

its’ always worked this way before, so it’s obviously good

practice. It’s the way we’ve always done it, and there’s no

clear evidence to contradict this and there is a comfort level

there in doing this, so that actually inhibits in varying de-

grees our ability to tackle this . . . ”

3.2 Lack of knowledge

Nurse practitioners and nurse managers felt that many in-

patient direct care nurses did not have a basic knowledge

of EBP. Further, these nurses may not be able to recognize

criteria that reflect high quality research. “I think it’s a chal-

lenge . . . to really grasp where to look because it’s so easy

to Google something. But to know what is truly supported by

Published by Sciedu Press 93

Table 2: Examples of focus group questions and sub-probes

Focus Group Content Questions Sub-Probes (If not mentioned, ask)

Research Objective 1 Where did you first learn about

evidence-based practice?

1. Education program

2. Previous work setting and experience

Research Objective 2

What barriers have you encountered

related to implementing

evidence-based practice?

1. Do you feel that evidence- based practice is supported in your work setting?

2. What are some examples?

3. Are there any patient-related factors that are barriers (“Can you tell us more if

‘yes’ only response)?

4. Are there any staff-related factors that are barriers (“Can you tell us more if

‘yes’ only response”)?

5. Do you have access to evidence-based practice resources? (“Can you tell us

more if ‘yes’ only response”).

6. Do you have sufficient knowledge of evidence-based practice to incorporate it

into your practice (“Can you tell us more if ‘yes’ only response”)?

7. How do you know whether evidence- based practice is effective?

Research Objective 3

What recommendations do you

have relative to promoting

evidence-based practice in your

work setting?

1. What types of resources would you need to foster evidence- based practice in

your work environment?

2. What are things the institution could do to foster evidence-based practice in

your work environment?

3. What are things you and your co-workers could do to foster evidence-based

practice in your work environment?

2.3 Data analysis

Using procedures established by Krueger and Casey[8, 25] the

tapes were transcribed verbatim. Transcriptions were re-

viewed for accuracy and independently examined by the in-

vestigators. Analysis was applied towards the recognition

and modification of major themes and sub-themes. [8, 24, 25]

Data were compared across the three focus group encoun-

ters with focused attention to group similarities and differ-

ences. Content categories were developed, and agreement

related to content was obtained following the two indepen-

dent reviews and follow-up discussions among study inves-

tigators.

3 Results

Six factors were identified as challenges to EBP adoption:

institutional and/or cultural barriers, lack of knowledge, lack

of motivation, time management, physician and patient fac-

tors, and limited access to up to date, user-friendly technol-

ogy and computer systems. Nurses also discussed strategies

to improve adoption of EBP. Specific examples of the major

themes are provided in the following paragraphs.

3.1 Institutionaland/or culturalbarriers

Members of the three groups identified cultural factors

within the institution and the need to promote system-wide

hospital change as being significant barriers. One nurse

practitioner described the culture as being one that did not

demand best practice from the nurses. “I think in places that

back up their practice with evidence, there’s this culture of

learning and of ‘we want it to be the most current and up

to date’. That’s when you hear guys walking around hall-

ways and quoting [EBP from] studies, and we don’t have

that here so there has to be a culture change.”

An inpatient direct care nurse described that the importance

of professional advancement among nurses was undermined

because of cultural attitudes of the hospital system. “I . . .

wanted my specialty in oncology and my preceptor said,

why? You’re not going to get any more money . . .You know

[named hospital] doesn’t care if you’ve got that. I said I’m

doing it for me. I want to explain to my patient why the OCN

[oncology certified nurse] is behind my name.”

Nurse practitioners discussed traditional norms and a strong

tendency to fall back on habits rather then base practice on

current evidence. One nurse practitioner stated, “When you

bring it [EBP] up to the nurses, if you ask them why you

do it this way . . . They say it’s because we’ve always done

it. When you look at the whole, it’s more of a process is-

sue . . . because that’s how we’ve always done it than an

actual task itself.” Another nurse practitioner stated, “There

are some things we do that we blatantly say, ‘there is no ev-

idence for this, we’re just going to do it.’ Some of that is

because ‘guys’ are a little stodgy and stuck in their way and

its’ always worked this way before, so it’s obviously good

practice. It’s the way we’ve always done it, and there’s no

clear evidence to contradict this and there is a comfort level

there in doing this, so that actually inhibits in varying de-

grees our ability to tackle this . . . ”

3.2 Lack of knowledge

Nurse practitioners and nurse managers felt that many in-

patient direct care nurses did not have a basic knowledge

of EBP. Further, these nurses may not be able to recognize

criteria that reflect high quality research. “I think it’s a chal-

lenge . . . to really grasp where to look because it’s so easy

to Google something. But to know what is truly supported by

Published by Sciedu Press 93

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

www.sciedu.ca/cns Clinical Nursing Studies 2015, Vol. 3, No. 2

good research and to know the difference rather than it’s Dr.

Oz saying it . . . To know it’s from a good nursing or medical

journal.” Nurse practitioners described inpatient direct care

nurses who were not adequately prepared. “They’re very

task focused. . . . and then recently they did the whole nurse

survey of education levels, and so I saw that and I thought

ohhh . . . there are so few BSN [bachelor of science in nurs-

ing] nurses here.” Importantly “lack of knowledge” was not

discussed as a theme by the inpatient direct care nurses in

their respective focus group.

3.3 Lack of motivation

Inpatient direct care nurses described the importance of hav-

ing personal drive and motivation to improve themselves

to provide better professional care. In some discussions,

nurses verbalized not being interested or inspired to adopt

EBP. In one specific example, a inpatient direct care nurse

stated: “Seeing that a lot of nurses have been here a long

time which is a really good thing that there is so much

longevity . . . But it is easy when you are entrenched . . .hav-

ing spent many years at one facility, you become stagnant,

that is a good term for it.” Managers described nurses as not

motivated to implement EBP because of the length of time

between formal academic training and current employment.

“A lot of them . . . want to come and do their job and . . .

Somewhere along the line . . . they have forgotten about the

need to stay current, their responsibility to the profession,

their patients, and to their license . . . ”

3.4 Time management

Time commitment was a barrier to implementation of

system-wide changes identified in all three focus groups.

One nurse practitioner expressed concern that it was not re-

alistic to expect nurses to follow up with research to back

up their practice. “They are trying to take care of patients

. . . They’re not gonna (sic) look up an article . . . [They]

would love to look this stuff up and understand it more, but

they don’t have the time or the options, and then they’re off

hours.” A nurse manager stated: “Implementing evidence-

based practice is very time consuming, and there are a lot

of hoops and bells to jump through and people to talk to to

get anything implemented, so that’s a barrier. Where you

have nurses or even mid-level staff bringing in really good

research-based evidence and to get it presented to the doc-

tors and to get everyone on board, and then do the education

so that everyone knows it . . .I think that’s a bigger obstacle

than just getting to the research. It’s what do I do with it

once I get it, and what’s the steps and a timely manner and

have a response one way or another . . . ”

3.5 Physician and patient factors

Nurse practitioners noted that both doctors and patients had

different values and beliefs that may conflict with provid-

ing care based on high evidence. One nurse practitioner de-

scribed doctors who did not question their traditional prac-

tice habits. “It’s a challenge because the doctors practice a

certain way and not that they don’t care, but they feel their

way is evidence based even though it may be outdated. So

that’s the challenge . . . that the doctors want to keep their

evidence base even though it may be from 10 years ago.”

Nurse practitioners felt that patients did not want to change

their treatment plans when new evidence emerged. An ex-

ample of one discussion was: “If you bring something new

to the table to them [older patients], it is quite a struggle

to get them convinced to change . . . ‘I’ve been on this beta

blocker for 30 years. I’ve always been on Lasix and that’s

what they use to control my blood pressure’. ‘But you’re

frail now and you shouldn’t have it’. So trying to convince

them . . . or their family who their loved one has been on

Aricept [Donepezil] or Nemanda [Memantin] for 10 years

and now tell them it’s not any good any more, research is

showing us that . . . and they say . . . please don’t take it

away, I don’t care what your research says.”

3.6 Limited access to up-to-date user-friendly tech-

nology and computer systems

Adequate computer resources were essential for EBP im-

plementation as identified by a nurse practitioner and nurse

manager. A nurse manager stated: “Your computer sys-

tems . . . . [are] very lacking and challenging to work with.

[It] was phenomenally hard to navigate.” Nurse practition-

ers’ identified that inpatient nurses who provide direct pa-

tient care require access to and assistance with technical re-

sources.

3.7 Strategiesto improve adoption ofevidence-

based practice

Nurses’ expressed interdisciplinary communication and col-

laboration, mentorship, access to professional activities and

networks, and supportive management as crucial to EBP

adoption. Inpatient direct care providers emphasized that

management needed to champion advanced education for

bedside nurses.

One nurse practitioner stated that physician support was

needed to make the transition to evidence-based care. “The

physician may see it [evidence read in the literature] as a

threat to their power or knowledge base. How many times

have you heard ‘you think you know more than I do?’” A

nurse practitioner stated: “I see it when you go to critical

care. They [the nurses] have a lot more autonomy because

of their comfort with their relationship with the doctor. More

than anything, the skill is there in general, but it’s what

they’ve been empowered to do. You have strong nurses in

the specialty setting, and they’re comfortable with what they

know.”

Participants described ways to inspire EBP adoption. Con-

ference attendance, training sessions, and organizational

94 ISSN 2324-7940 E-ISSN 2324-7959

good research and to know the difference rather than it’s Dr.

Oz saying it . . . To know it’s from a good nursing or medical

journal.” Nurse practitioners described inpatient direct care

nurses who were not adequately prepared. “They’re very

task focused. . . . and then recently they did the whole nurse

survey of education levels, and so I saw that and I thought

ohhh . . . there are so few BSN [bachelor of science in nurs-

ing] nurses here.” Importantly “lack of knowledge” was not

discussed as a theme by the inpatient direct care nurses in

their respective focus group.

3.3 Lack of motivation

Inpatient direct care nurses described the importance of hav-

ing personal drive and motivation to improve themselves

to provide better professional care. In some discussions,

nurses verbalized not being interested or inspired to adopt

EBP. In one specific example, a inpatient direct care nurse

stated: “Seeing that a lot of nurses have been here a long

time which is a really good thing that there is so much

longevity . . . But it is easy when you are entrenched . . .hav-

ing spent many years at one facility, you become stagnant,

that is a good term for it.” Managers described nurses as not

motivated to implement EBP because of the length of time

between formal academic training and current employment.

“A lot of them . . . want to come and do their job and . . .

Somewhere along the line . . . they have forgotten about the

need to stay current, their responsibility to the profession,

their patients, and to their license . . . ”

3.4 Time management

Time commitment was a barrier to implementation of

system-wide changes identified in all three focus groups.

One nurse practitioner expressed concern that it was not re-

alistic to expect nurses to follow up with research to back

up their practice. “They are trying to take care of patients

. . . They’re not gonna (sic) look up an article . . . [They]

would love to look this stuff up and understand it more, but

they don’t have the time or the options, and then they’re off

hours.” A nurse manager stated: “Implementing evidence-

based practice is very time consuming, and there are a lot

of hoops and bells to jump through and people to talk to to

get anything implemented, so that’s a barrier. Where you

have nurses or even mid-level staff bringing in really good

research-based evidence and to get it presented to the doc-

tors and to get everyone on board, and then do the education

so that everyone knows it . . .I think that’s a bigger obstacle

than just getting to the research. It’s what do I do with it

once I get it, and what’s the steps and a timely manner and

have a response one way or another . . . ”

3.5 Physician and patient factors

Nurse practitioners noted that both doctors and patients had

different values and beliefs that may conflict with provid-

ing care based on high evidence. One nurse practitioner de-

scribed doctors who did not question their traditional prac-

tice habits. “It’s a challenge because the doctors practice a

certain way and not that they don’t care, but they feel their

way is evidence based even though it may be outdated. So

that’s the challenge . . . that the doctors want to keep their

evidence base even though it may be from 10 years ago.”

Nurse practitioners felt that patients did not want to change

their treatment plans when new evidence emerged. An ex-

ample of one discussion was: “If you bring something new

to the table to them [older patients], it is quite a struggle

to get them convinced to change . . . ‘I’ve been on this beta

blocker for 30 years. I’ve always been on Lasix and that’s

what they use to control my blood pressure’. ‘But you’re

frail now and you shouldn’t have it’. So trying to convince

them . . . or their family who their loved one has been on

Aricept [Donepezil] or Nemanda [Memantin] for 10 years

and now tell them it’s not any good any more, research is

showing us that . . . and they say . . . please don’t take it

away, I don’t care what your research says.”

3.6 Limited access to up-to-date user-friendly tech-

nology and computer systems

Adequate computer resources were essential for EBP im-

plementation as identified by a nurse practitioner and nurse

manager. A nurse manager stated: “Your computer sys-

tems . . . . [are] very lacking and challenging to work with.

[It] was phenomenally hard to navigate.” Nurse practition-

ers’ identified that inpatient nurses who provide direct pa-

tient care require access to and assistance with technical re-

sources.

3.7 Strategiesto improve adoption ofevidence-

based practice

Nurses’ expressed interdisciplinary communication and col-

laboration, mentorship, access to professional activities and

networks, and supportive management as crucial to EBP

adoption. Inpatient direct care providers emphasized that

management needed to champion advanced education for

bedside nurses.

One nurse practitioner stated that physician support was

needed to make the transition to evidence-based care. “The

physician may see it [evidence read in the literature] as a

threat to their power or knowledge base. How many times

have you heard ‘you think you know more than I do?’” A

nurse practitioner stated: “I see it when you go to critical

care. They [the nurses] have a lot more autonomy because

of their comfort with their relationship with the doctor. More

than anything, the skill is there in general, but it’s what

they’ve been empowered to do. You have strong nurses in

the specialty setting, and they’re comfortable with what they

know.”

Participants described ways to inspire EBP adoption. Con-

ference attendance, training sessions, and organizational

94 ISSN 2324-7940 E-ISSN 2324-7959

www.sciedu.ca/cns Clinical Nursing Studies 2015, Vol. 3, No. 2

support for education (conference reimbursement, incen-

tives) were viewed as inspirational. “Trying to bring back

information when you go to conference that’s different, that

people are doing in other places . . . That exposure and to

share that information I think is important . . . I mean you

can read it in your journals, but it’s a lot more interesting

when you meet the people whose names are behind the arti-

cle in the journal.”

4 Discussion

While EBP has become an integral component of optimal

patient care, nursing professionals practicing in many hospi-

tal systems globally continue to experience barriers to pro-

motion of evidence-based care. In this study, focus group

discussions were used to elicit perspectives regarding pro-

fessional and institutional barriers related to EBP adoption.

In line with other studies, [18, 20, 26, 27] participants identified

limited resources as a primary concern to EBP implemen-

tation. Specific barriers included time, access to quality in-

formation, knowledge to translate evidence to practice, and

interdisciplinary collaboration. Task-based care may divert

nurses’ attention away from questioning traditional prac-

tices considering best practice alternatives.[7, 12]

Professional development to gain EBP knowledge is recog-

nized as the nurse’s best preparation for providing clinical

care that optimizes patient outcomes.[28] There may be less

incentive to aspire professionally in cultures where there is

a perception that there will not be managerial support and

recognition.[4, 7, 18] Similar to other studies, opportunities

and institutional support to attend conferences, further edu-

cation, and gain advanced training were viewed as important

factors to inspire EBP adoption.[27, 29]

Nurses’ in the focus groups identified that medical doctors

can be resistant to change. Collaborative relationships with

inter-disciplinary staff are integral to ensure that the patients

receive care based on the best available evidence.[16] Strate-

gic context-sensitive initiatives are needed to ensure that all

team members (inpatient direct care nurses, doctors, man-

agement, nurses in advanced roles, etc.) recognize a com-

mon mission and their accountability in ensuring that pa-

tients receive care based on best evidence. Although chal-

lenging, team-oriented methods to enhance communication

and to promote strong relationships among staff are essen-

tial to lead organizational change. Early foundations can be

laid with a motivated nurse research council to familiarize

nurses with clinical research and the benefits of EBP. [17, 28]

Evidence-based fellowships that attract motivated clinical

nurses to lead change and inspire practice settings to ask

questions and be resourceful are increasingly seen as an es-

sential tool to motivate change. [28] With trained mentors

familiarized with the cultural setting, such innovative pro-

grams can serve as a bridge to bring real-world research to

the bedside to improve patient care quality. [28] In environ-

ments where the majority of inpatient direct care nurses are

associate degree prepared, there is an increased need for mo-

tivated clinical nurses to provide guidance and mentorship

to their colleagues.

The focus group approach limits the nurse researcher to

small convenience samples of participants for institutional

representation. Along this vein, the nurses who participated

in the focus groups may have consisted of those inspired to

make practice changes or who wanted to express disgruntle-

ment. Further, given most (82%) of the nurses providing

inpatient direct care who participated were associate degree

prepared nurses’, they may have lacked formal EBP educa-

tional preparation. It is recognized that focus group formats

may limit discussion if there are informal leaders among

participants.[8, 10] For example, alternate perspectives may

not emerge if members were cautious of raising contrary

opinions. Focus group findings are not meant to be transfer-

able to other populations or situations, but identify unique

themes addressable to the specific cultural setting.[5, 10] Im-

portantly, clinical nurse specialists may find the focus group

format helpful to gain valuable information about barriers

in their respective work sites, while promoting a participa-

tory approach that makes nurses feel that their perspectives

are valuable. Limitations of focus group methodology in-

clude that groups require participant trust, information can

be withheld and/or be aligned with what the participants

think the facilitator wants to hear, and data may be limited

by “group think” that confines the discourse to one perspec-

tive.[10] Another limitation of this study is that only one fo-

cus group was conducted with each of the respective groups

of nurses. It is plausible that more information could have

been gleaned by conducting further focus groups with dif-

ferent groups of participants. Thus, future studies of this

nature should involve more sessions to ensure that all the

essential information, or data saturation, is attained.

5 Conclusions

The focus group findings provide important context-specific

information relative to staff readiness to adopt EBP. While

the presence of pro-active nurse practitioners who have

training and familiarity with EBP and are strengths, these

advanced practice nurses tended to be negative in their at-

titudes about the potential of staff nurses to move forward

with a practice guided by evidence. Importantly, however,

nurses who with advanced training have the clinical skills

and experience to partner in promoting and facilitating EBP

for clinical nurses. [15, 27] It is recognized that hospital cul-

ture that stimulates ongoing inquiry and utilization of the

best available evidence guides care towards optimizing pa-

tient outcomes. Building infrastructure to sustain and sup-

port EBP via leadership; the provision of time; access to and

support for continuing education; and collaborative integra-

tion of team members will guide the development of clinical

environments that promote EBP at the patient level. Clini-

Published by Sciedu Press 95

support for education (conference reimbursement, incen-

tives) were viewed as inspirational. “Trying to bring back

information when you go to conference that’s different, that

people are doing in other places . . . That exposure and to

share that information I think is important . . . I mean you

can read it in your journals, but it’s a lot more interesting

when you meet the people whose names are behind the arti-

cle in the journal.”

4 Discussion

While EBP has become an integral component of optimal

patient care, nursing professionals practicing in many hospi-

tal systems globally continue to experience barriers to pro-

motion of evidence-based care. In this study, focus group

discussions were used to elicit perspectives regarding pro-

fessional and institutional barriers related to EBP adoption.

In line with other studies, [18, 20, 26, 27] participants identified

limited resources as a primary concern to EBP implemen-

tation. Specific barriers included time, access to quality in-

formation, knowledge to translate evidence to practice, and

interdisciplinary collaboration. Task-based care may divert

nurses’ attention away from questioning traditional prac-

tices considering best practice alternatives.[7, 12]

Professional development to gain EBP knowledge is recog-

nized as the nurse’s best preparation for providing clinical

care that optimizes patient outcomes.[28] There may be less

incentive to aspire professionally in cultures where there is

a perception that there will not be managerial support and

recognition.[4, 7, 18] Similar to other studies, opportunities

and institutional support to attend conferences, further edu-

cation, and gain advanced training were viewed as important

factors to inspire EBP adoption.[27, 29]

Nurses’ in the focus groups identified that medical doctors

can be resistant to change. Collaborative relationships with

inter-disciplinary staff are integral to ensure that the patients

receive care based on the best available evidence.[16] Strate-

gic context-sensitive initiatives are needed to ensure that all

team members (inpatient direct care nurses, doctors, man-

agement, nurses in advanced roles, etc.) recognize a com-

mon mission and their accountability in ensuring that pa-

tients receive care based on best evidence. Although chal-

lenging, team-oriented methods to enhance communication

and to promote strong relationships among staff are essen-

tial to lead organizational change. Early foundations can be

laid with a motivated nurse research council to familiarize

nurses with clinical research and the benefits of EBP. [17, 28]

Evidence-based fellowships that attract motivated clinical

nurses to lead change and inspire practice settings to ask

questions and be resourceful are increasingly seen as an es-

sential tool to motivate change. [28] With trained mentors

familiarized with the cultural setting, such innovative pro-

grams can serve as a bridge to bring real-world research to

the bedside to improve patient care quality. [28] In environ-

ments where the majority of inpatient direct care nurses are

associate degree prepared, there is an increased need for mo-

tivated clinical nurses to provide guidance and mentorship

to their colleagues.

The focus group approach limits the nurse researcher to

small convenience samples of participants for institutional

representation. Along this vein, the nurses who participated

in the focus groups may have consisted of those inspired to

make practice changes or who wanted to express disgruntle-

ment. Further, given most (82%) of the nurses providing

inpatient direct care who participated were associate degree

prepared nurses’, they may have lacked formal EBP educa-

tional preparation. It is recognized that focus group formats

may limit discussion if there are informal leaders among

participants.[8, 10] For example, alternate perspectives may

not emerge if members were cautious of raising contrary

opinions. Focus group findings are not meant to be transfer-

able to other populations or situations, but identify unique

themes addressable to the specific cultural setting.[5, 10] Im-

portantly, clinical nurse specialists may find the focus group

format helpful to gain valuable information about barriers

in their respective work sites, while promoting a participa-

tory approach that makes nurses feel that their perspectives

are valuable. Limitations of focus group methodology in-

clude that groups require participant trust, information can

be withheld and/or be aligned with what the participants

think the facilitator wants to hear, and data may be limited

by “group think” that confines the discourse to one perspec-

tive.[10] Another limitation of this study is that only one fo-

cus group was conducted with each of the respective groups

of nurses. It is plausible that more information could have

been gleaned by conducting further focus groups with dif-

ferent groups of participants. Thus, future studies of this

nature should involve more sessions to ensure that all the

essential information, or data saturation, is attained.

5 Conclusions

The focus group findings provide important context-specific

information relative to staff readiness to adopt EBP. While

the presence of pro-active nurse practitioners who have

training and familiarity with EBP and are strengths, these

advanced practice nurses tended to be negative in their at-

titudes about the potential of staff nurses to move forward

with a practice guided by evidence. Importantly, however,

nurses who with advanced training have the clinical skills

and experience to partner in promoting and facilitating EBP

for clinical nurses. [15, 27] It is recognized that hospital cul-

ture that stimulates ongoing inquiry and utilization of the

best available evidence guides care towards optimizing pa-

tient outcomes. Building infrastructure to sustain and sup-

port EBP via leadership; the provision of time; access to and

support for continuing education; and collaborative integra-

tion of team members will guide the development of clinical

environments that promote EBP at the patient level. Clini-

Published by Sciedu Press 95

www.sciedu.ca/cns Clinical Nursing Studies 2015, Vol. 3, No. 2

cal nurse specialists who are at the forefront in setting the

stage for strategic initiation of professional organizational

shifts to promote best care may find the focus group ap-

proach helpful in guiding such efforts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Allegiance Health

System and the nurse participants for their time, support,

and commitment.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest or funding sources to re-

port.

References

[1] Austin L, Luker K, Martin R. Clinical nurse specialists and the prac-

tice of community nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2006; 54: 542-552. http:

//dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03868_1.x

[2] Heitkemper MM, Bond E. Clinical nurse specialist: State of the pro-

fession and challenges ahead. Clin Nurs Spec. 2004; 18: 135-140.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002800-200405000-00014

[3] Linton MJ, Prasun MA. Evidence-based practice: Collaboration be-

tween education and nursing management. J Nurs Manag. 2013; 21:

5-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.014

40.x

[4] Koehn ML, Lehman K. Nurses’ perceptions of evidence-based nurs-

ing practice. J Adv Nurs. 2008; 62: 209-215. http://dx.doi.org

/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04589.x

[5] Calarco MM. The impact of positive practices on nurse work envi-

ronments: Emerging applications of positive organizational scholar-

ship. West J Nurs Res. 2011; 33: 365-384.http://dx.doi.org/1

0.1177/0193945910380211

[6] Atkinson M, Turkel M. Overcoming barriers to research in a magnet

community hospital. J Nurs Care Qual. 2008; 23: 362-368. http:

//dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.NCQ.0000336675.48466.37

[7] Fineout-Overholt E, Levin RF, Melnyk B. Strategies for advancing

evidence-based practice in clinical settings. J New York Nurs Assn.

2004/2005; 28-32.

[8] Krueger A, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Ap-

plied Research. 3rd ed. London, England: Sage; 2000.

[9] Gibson F, Bamford O. Focus group interviews to examine the role

and development of the clinical nurse specialist. J Nurs Manage-

ment. 2001; 9: 331-342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.096

6-0429.2001.00267.x

[10] Marrelli AF. Collecting data through focus groups. Perform Im-

prove. 2013; 47: 39-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pfi.201

[11] Taylor R. Using and developing the evidence base in primary health

care. Prim Health Care. 2012; 22: 31-36. http://dx.doi.org/1

0.7748/phc2012.02.22.1.31.c8916

[12] Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk B. Building a culture of best practice.

Nurs Leader. 2005; 26-29.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl

.2005.09.007

[13] Stevens K. The Impact of Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and

the Next Big Ideas. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing.

2013; 18(2): Manuscript 4. http://dx.doi.org/10.3912/OJI

N.Vol18No02Man04

[14] Larkin M, Cierpial C, Vanderboom T, et al. Research ambas-

sadors: Bringing findings to the bedside. Nurs Manag. 2009; 40:

20-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000361805.

74369.23

[15] Gerrish K, Nolan M, McDonnell A, et al. Factors influencing ad-

vanced practice nurses’ ability to promote evidence-based practice

among frontline nurses. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2012; 9: 30-

39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00230

.x

[16] Everett LQ, Siterding MC. Transformational leadership required to

design and sustain evidence-based practice: A system exemplar.

West J Nurs Res. 2011; 33: 398-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.

1177/0193945910383056

[17] Sandström B, Borglin G, Nilsson R, et al. Promoting the imple-

mentation of evidence-based practice: A literature review focus-

ing on the role of nursing leadership. Worldviews Evid-based Nurs.

2011; 8: 212-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-678

7.2011.00216.x

[18] Stokke K, Olesen N R, Espehaug B, et al. Evidence based practice

beliefs and implementation among nurses: A cross-sectional study.

BMC Nurs. 2014; 13: 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/147

2-6955-13-8

[19] Brewer B, Brewer M, Schultz A. A collaborative approach to build-

ing the capacity for research and evidence-based practice in com-

munity hospitals. Nurs Clin North Amer. 2009; 44: 11-25. http:

//dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2008.10.003

[20] Nagy S, Lumby J, McKinley S, et al. Nurses’ beliefs about the con-

ditions that hinder or support evidence-based nursing. Int J Nurs

Pract. 2001; 7: 314-321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.144

0-172X.2001.00284.x

[21] Rickbeil P, Simones J. Overcoming barriers to implementing

evidence-based practice. J Nurs Staff Dev. 2012; 28: 51-56. http:

//dx.doi.org/10.1097/NND.0b013e31824b4141

[22] Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Putting research into prac-

tice. Rochester ARCC. Reflect Nurs Lead. 2002; 28: 22-25.

PMid:12073802.

[23] Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. The Evidence-Based Practice Be-

liefs and Implementation Scales: Psychometric Properties of Two

New Instruments. Worldviews Evid-based Nurs. 2007; 4: 208-215.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00126.x

[24] Barbour RS. Making sense of focus groups. Med Educ. 2005;

39: 742-750. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.20

05.02200.x

[25] Curtis EA, Redmond R. Focus groups in nursing research. Nurs Re-

searcher. 2007; 14: 25-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.7748/nr200

7.01.14.2.25.c6019

[26] Gawlinski A, Rutledge D. Selecting a model for evidence-based

practice changes: A practical approach. AACN Adv Crit Care.

2008; 19: 291-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.AACN.0

000330380.41766.63

[27] Solomons NM, Spross JA. Evidence-based practice barriers and fa-

cilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an

integrative review. J Nurs Manag. 2011; 19: 109-120. http://dx

.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01144.x

[28] Latimer R, Kimball J. Nursing research fellowship: Building nurs-

ing research infrastructure in a hospital. J Nurs Admin. 2010;

40: 92-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181c

b9f9e

[29] Pierson M, Schuelke S. Strengthening the use of evidence-based

practice: development of an independent study packet. J Cont Educ

Nurs. 2009; 40: 171-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/00220

124-20090401-09

96 ISSN 2324-7940 E-ISSN 2324-7959

cal nurse specialists who are at the forefront in setting the

stage for strategic initiation of professional organizational

shifts to promote best care may find the focus group ap-

proach helpful in guiding such efforts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Allegiance Health

System and the nurse participants for their time, support,

and commitment.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest or funding sources to re-

port.

References

[1] Austin L, Luker K, Martin R. Clinical nurse specialists and the prac-

tice of community nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2006; 54: 542-552. http:

//dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03868_1.x

[2] Heitkemper MM, Bond E. Clinical nurse specialist: State of the pro-

fession and challenges ahead. Clin Nurs Spec. 2004; 18: 135-140.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002800-200405000-00014

[3] Linton MJ, Prasun MA. Evidence-based practice: Collaboration be-

tween education and nursing management. J Nurs Manag. 2013; 21:

5-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.014

40.x

[4] Koehn ML, Lehman K. Nurses’ perceptions of evidence-based nurs-

ing practice. J Adv Nurs. 2008; 62: 209-215. http://dx.doi.org

/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04589.x

[5] Calarco MM. The impact of positive practices on nurse work envi-

ronments: Emerging applications of positive organizational scholar-

ship. West J Nurs Res. 2011; 33: 365-384.http://dx.doi.org/1

0.1177/0193945910380211

[6] Atkinson M, Turkel M. Overcoming barriers to research in a magnet

community hospital. J Nurs Care Qual. 2008; 23: 362-368. http:

//dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.NCQ.0000336675.48466.37

[7] Fineout-Overholt E, Levin RF, Melnyk B. Strategies for advancing

evidence-based practice in clinical settings. J New York Nurs Assn.

2004/2005; 28-32.

[8] Krueger A, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Ap-

plied Research. 3rd ed. London, England: Sage; 2000.

[9] Gibson F, Bamford O. Focus group interviews to examine the role

and development of the clinical nurse specialist. J Nurs Manage-

ment. 2001; 9: 331-342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.096

6-0429.2001.00267.x

[10] Marrelli AF. Collecting data through focus groups. Perform Im-

prove. 2013; 47: 39-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pfi.201

[11] Taylor R. Using and developing the evidence base in primary health

care. Prim Health Care. 2012; 22: 31-36. http://dx.doi.org/1

0.7748/phc2012.02.22.1.31.c8916

[12] Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk B. Building a culture of best practice.

Nurs Leader. 2005; 26-29.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl

.2005.09.007

[13] Stevens K. The Impact of Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and

the Next Big Ideas. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing.

2013; 18(2): Manuscript 4. http://dx.doi.org/10.3912/OJI

N.Vol18No02Man04

[14] Larkin M, Cierpial C, Vanderboom T, et al. Research ambas-

sadors: Bringing findings to the bedside. Nurs Manag. 2009; 40:

20-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000361805.

74369.23

[15] Gerrish K, Nolan M, McDonnell A, et al. Factors influencing ad-

vanced practice nurses’ ability to promote evidence-based practice

among frontline nurses. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2012; 9: 30-

39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00230

.x

[16] Everett LQ, Siterding MC. Transformational leadership required to

design and sustain evidence-based practice: A system exemplar.

West J Nurs Res. 2011; 33: 398-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.

1177/0193945910383056

[17] Sandström B, Borglin G, Nilsson R, et al. Promoting the imple-

mentation of evidence-based practice: A literature review focus-

ing on the role of nursing leadership. Worldviews Evid-based Nurs.

2011; 8: 212-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-678

7.2011.00216.x

[18] Stokke K, Olesen N R, Espehaug B, et al. Evidence based practice

beliefs and implementation among nurses: A cross-sectional study.

BMC Nurs. 2014; 13: 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/147

2-6955-13-8

[19] Brewer B, Brewer M, Schultz A. A collaborative approach to build-

ing the capacity for research and evidence-based practice in com-

munity hospitals. Nurs Clin North Amer. 2009; 44: 11-25. http:

//dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2008.10.003

[20] Nagy S, Lumby J, McKinley S, et al. Nurses’ beliefs about the con-

ditions that hinder or support evidence-based nursing. Int J Nurs

Pract. 2001; 7: 314-321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.144

0-172X.2001.00284.x

[21] Rickbeil P, Simones J. Overcoming barriers to implementing

evidence-based practice. J Nurs Staff Dev. 2012; 28: 51-56. http:

//dx.doi.org/10.1097/NND.0b013e31824b4141

[22] Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Putting research into prac-

tice. Rochester ARCC. Reflect Nurs Lead. 2002; 28: 22-25.

PMid:12073802.

[23] Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. The Evidence-Based Practice Be-

liefs and Implementation Scales: Psychometric Properties of Two

New Instruments. Worldviews Evid-based Nurs. 2007; 4: 208-215.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00126.x

[24] Barbour RS. Making sense of focus groups. Med Educ. 2005;

39: 742-750. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.20

05.02200.x

[25] Curtis EA, Redmond R. Focus groups in nursing research. Nurs Re-

searcher. 2007; 14: 25-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.7748/nr200

7.01.14.2.25.c6019

[26] Gawlinski A, Rutledge D. Selecting a model for evidence-based

practice changes: A practical approach. AACN Adv Crit Care.

2008; 19: 291-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.AACN.0

000330380.41766.63

[27] Solomons NM, Spross JA. Evidence-based practice barriers and fa-

cilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an

integrative review. J Nurs Manag. 2011; 19: 109-120. http://dx

.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01144.x

[28] Latimer R, Kimball J. Nursing research fellowship: Building nurs-

ing research infrastructure in a hospital. J Nurs Admin. 2010;

40: 92-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181c

b9f9e

[29] Pierson M, Schuelke S. Strengthening the use of evidence-based

practice: development of an independent study packet. J Cont Educ

Nurs. 2009; 40: 171-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/00220

124-20090401-09

96 ISSN 2324-7940 E-ISSN 2324-7959

1 out of 7

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com