Critical Thinking in Nursing: A Scoping Review of Literature

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/21

|11

|7829

|441

Report

AI Summary

This research paper presents a scoping review of the literature on critical thinking (CT) in nursing, analyzing studies published between January 1999 and June 2013. The review identified 90 relevant studies from a total of 1518, highlighting a growing interest in CT concepts, dimensions, and training strategies within nursing education. The study primarily investigated CT in university settings, using various measurement instruments. The review recommends further research on CT among working professionals, the development of evaluative instruments linked to conceptual models, and the identification of strategies to promote CT in nursing care. The analysis reveals that the majority of studies originated from the USA and focused on nursing students, with descriptive studies being the most common design. The research underscores the importance of CT in improving clinical reasoning, judgment, and decision-making within the healthcare environment, emphasizing the need for continued exploration and development in both educational and professional contexts.

R E S E A R C H P A P E R

Critical thinking in nursing: Scoping

of the literature

Esperanza Zuriguel Pérez RN

PhD Student, Hospital Vall d’Hebron, University School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barce

Maria Teresa Lluch Canut RN PhD

Professor, University School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Anna Falcó Pegueroles RN MHSc PhD

Professor, University School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Montserrat Puig Llobet RN PhD

Professor, University School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Carmen Moreno Arroyo RN

Professor, University School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Juan Roldán Merino RN PhD

Professor, Sant Joan de Deu School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Associate Professor, Rovira i Virigili University, Tarragona, Spain

Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Sp

Accepted for publication March 2014

Zuriguel Pérez E, Lluch Canut MT, Falcó Pegueroles A, Puig Llobet M, Moreno Arroyo C, Roldán

International Journal of Nursing Practice 2014; ••: ••–••

Critical thinking in nursing: Scoping review of the literature

This article seeks to analyse the current state of scientific knowledge concerning critical thinking i

used consisted of a scoping review of the main scientific databases using an applied search strate

published from January 1999 to June 2013 were identified, of which 90 met the inclusion criteria. T

is that critical thinking in nursing is experiencing a growing interest in the study of both its concep

as in the development of training strategies to further its development among both students and p

the analysis reveals that critical thinking has been investigated principally in the university setting

models, with a variety of instruments used for its measurement. We recommend (i) the investigat

among working professionals, (ii) the designing of evaluative instruments linked to conceptual mo

cation of strategies to promote critical thinking in the context of providing nursing care.

Key words:critical thinking, nurses, nursing, nursing education, systematic review.

Correspondence:Esperanza ZuriguelPérez,HospitalValld’Hebron,Passeig de la Valld’Hebron,119-129 08035 Barcelona,Spain.Email:

ezurigue@vhebron.net

bs_bs_banner

International Journal of Nursing Practice 2014; ••: ••–••

doi:10.1111/ijn.12347 © 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Critical thinking in nursing: Scoping

of the literature

Esperanza Zuriguel Pérez RN

PhD Student, Hospital Vall d’Hebron, University School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barce

Maria Teresa Lluch Canut RN PhD

Professor, University School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Anna Falcó Pegueroles RN MHSc PhD

Professor, University School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Montserrat Puig Llobet RN PhD

Professor, University School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Carmen Moreno Arroyo RN

Professor, University School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Juan Roldán Merino RN PhD

Professor, Sant Joan de Deu School of Nursing, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Associate Professor, Rovira i Virigili University, Tarragona, Spain

Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Sp

Accepted for publication March 2014

Zuriguel Pérez E, Lluch Canut MT, Falcó Pegueroles A, Puig Llobet M, Moreno Arroyo C, Roldán

International Journal of Nursing Practice 2014; ••: ••–••

Critical thinking in nursing: Scoping review of the literature

This article seeks to analyse the current state of scientific knowledge concerning critical thinking i

used consisted of a scoping review of the main scientific databases using an applied search strate

published from January 1999 to June 2013 were identified, of which 90 met the inclusion criteria. T

is that critical thinking in nursing is experiencing a growing interest in the study of both its concep

as in the development of training strategies to further its development among both students and p

the analysis reveals that critical thinking has been investigated principally in the university setting

models, with a variety of instruments used for its measurement. We recommend (i) the investigat

among working professionals, (ii) the designing of evaluative instruments linked to conceptual mo

cation of strategies to promote critical thinking in the context of providing nursing care.

Key words:critical thinking, nurses, nursing, nursing education, systematic review.

Correspondence:Esperanza ZuriguelPérez,HospitalValld’Hebron,Passeig de la Valld’Hebron,119-129 08035 Barcelona,Spain.Email:

ezurigue@vhebron.net

bs_bs_banner

International Journal of Nursing Practice 2014; ••: ••–••

doi:10.1111/ijn.12347 © 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

INTRODUCTION

Critical thinking (CT) is a cognitive process that includes

rational analysis of information to facilitate clinical reason-

ing, judgment and decision-making.1 The complexity and

ever-changing nature of the health-care workplace, along

with the need for care centred on the patient in tandem

with practice based on evidence, combine to highlight CT

as a competence of great importance in education and in

professional practice.

Severalinternationalorganizationshave putforward

initiatives to pay greater attention to CT. For example,

the National League for Nurses2 included CT as a specific

criterion in the accreditation of academic programs. For

its part,theJointCommission forAccreditation for

Healthcare Organizations3 included CT among its norms

as a key skill in nursing.

CT is particularly important in the nursing profession,

given itspotentialimpactupon the care thatpatients

receive.The capacityof thenursingprofessionalto

achieve improvements in the quality of care depends, in

large measure, upon developing CT skills so as to improve

diagnostic decisions.4

CT is a process that can be explored and then assimi-

lated during both the educational period and the profes-

sionalcareer that follows. Nevertheless, some problems

associated with itremain to be resolved,such asthe

ambiguous nature of the concept, measurement of it and

strategies for better developing it.

The present article reports on a review of studies

lished in the past 14 years, with the aim of analysin

current state of knowledge regarding CT in nursing.

METHODS

We carried out a scoping review of the scientific lite

ture on CT in nursing and related concepts,following

the guidelines set forth in the PRISMA standard5 (Pre-

ferredReportingItemsfor SystematicReviewsand

Meta-Analyses).Studieswere identified principally by

means ofsystematic conventionalsearches ofelectronic

databases. Various combinations of the following m

subject headings (MeSH) were used: ‘criticalthinking’,

‘problem solving’, ‘decision-making’, ‘judgment’, ‘c

petence’ and ‘nursing’. The search strategy was car

out in MEDLINE,CINAHL, LILACSand Cochrane

Library Plus.Table 1 presentsthe search strategy that

was used.

In addition,a secondary search wascarried outby

reviewing the bibliographic references cited in the s

thatwere included.The language forthe review was

English, and the publications considered ran from Ja

1999 to June 2013. The review was limited to origin

articles.The search strategy was notrestricted by any

particular research design. Figure 1 illustrates the s

procedure that was followed.

Some 1518 referenceswere obtained,of which 93

were eliminated as duplicates. A process of discrim

Table 1 Strategy for bibliographic search

MEDLINE CINAHL Cochrane Library Plus LILACS

#1: ‘critical thinking’

#2: ‘nursing’

#3: #2 AND # 3

#4: ‘nursing [majr]’

#5: (‘thinking [majr]’ OR ‘clinical

competence/standards [MeSH]’)

OR ‘nursing care/standard [MeSH]’

#6: (#4) AND #5

#7: (‘thinking [MeSH]’ OR ‘clinical

competence/standards [MeSH]’)

or ‘nursing care/standard’

#8: ‘nurses [MeSH]’

#9: #7 AND #8

#1: ‘critical thinking’

#2: ‘nursing care’

#3: ‘clinical competence’

#4: #1 AND #2

#5: #1 AND #3

#6: #1 AND #2 AND #3

#1: ‘critical thinking’

AND ‘nurs*’

#1: ‘critical thinking’

#2: ‘nursing’

#3: ‘critical thinking’

AND ‘nursing’

#4: ‘clinical judgment’

AND ‘nurs*’

2 E Zuriguel Pérez et al.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Critical thinking (CT) is a cognitive process that includes

rational analysis of information to facilitate clinical reason-

ing, judgment and decision-making.1 The complexity and

ever-changing nature of the health-care workplace, along

with the need for care centred on the patient in tandem

with practice based on evidence, combine to highlight CT

as a competence of great importance in education and in

professional practice.

Severalinternationalorganizationshave putforward

initiatives to pay greater attention to CT. For example,

the National League for Nurses2 included CT as a specific

criterion in the accreditation of academic programs. For

its part,theJointCommission forAccreditation for

Healthcare Organizations3 included CT among its norms

as a key skill in nursing.

CT is particularly important in the nursing profession,

given itspotentialimpactupon the care thatpatients

receive.The capacityof thenursingprofessionalto

achieve improvements in the quality of care depends, in

large measure, upon developing CT skills so as to improve

diagnostic decisions.4

CT is a process that can be explored and then assimi-

lated during both the educational period and the profes-

sionalcareer that follows. Nevertheless, some problems

associated with itremain to be resolved,such asthe

ambiguous nature of the concept, measurement of it and

strategies for better developing it.

The present article reports on a review of studies

lished in the past 14 years, with the aim of analysin

current state of knowledge regarding CT in nursing.

METHODS

We carried out a scoping review of the scientific lite

ture on CT in nursing and related concepts,following

the guidelines set forth in the PRISMA standard5 (Pre-

ferredReportingItemsfor SystematicReviewsand

Meta-Analyses).Studieswere identified principally by

means ofsystematic conventionalsearches ofelectronic

databases. Various combinations of the following m

subject headings (MeSH) were used: ‘criticalthinking’,

‘problem solving’, ‘decision-making’, ‘judgment’, ‘c

petence’ and ‘nursing’. The search strategy was car

out in MEDLINE,CINAHL, LILACSand Cochrane

Library Plus.Table 1 presentsthe search strategy that

was used.

In addition,a secondary search wascarried outby

reviewing the bibliographic references cited in the s

thatwere included.The language forthe review was

English, and the publications considered ran from Ja

1999 to June 2013. The review was limited to origin

articles.The search strategy was notrestricted by any

particular research design. Figure 1 illustrates the s

procedure that was followed.

Some 1518 referenceswere obtained,of which 93

were eliminated as duplicates. A process of discrim

Table 1 Strategy for bibliographic search

MEDLINE CINAHL Cochrane Library Plus LILACS

#1: ‘critical thinking’

#2: ‘nursing’

#3: #2 AND # 3

#4: ‘nursing [majr]’

#5: (‘thinking [majr]’ OR ‘clinical

competence/standards [MeSH]’)

OR ‘nursing care/standard [MeSH]’

#6: (#4) AND #5

#7: (‘thinking [MeSH]’ OR ‘clinical

competence/standards [MeSH]’)

or ‘nursing care/standard’

#8: ‘nurses [MeSH]’

#9: #7 AND #8

#1: ‘critical thinking’

#2: ‘nursing care’

#3: ‘clinical competence’

#4: #1 AND #2

#5: #1 AND #3

#6: #1 AND #2 AND #3

#1: ‘critical thinking’

AND ‘nurs*’

#1: ‘critical thinking’

#2: ‘nursing’

#3: ‘critical thinking’

AND ‘nursing’

#4: ‘clinical judgment’

AND ‘nurs*’

2 E Zuriguel Pérez et al.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

was then carried out by means of analysis of the titles and

abstracts of the remaining 1425 citations. The 155 docu-

ments that passed this filter were then subjected to further

screening based on a reading of the complete text, which

led to the elimination of an additional50 papers. In the

end 90 articles were included in the review.

Analysis was carried out in two stages. First, descrip-

tive aspectsof the studieswere analysed,and then a

topical analysis of the studies was carried out.

The variablesstudied included the productivity and

methodological characteristics of the sample.

The productivity characteristics included the following:

•Number of articles by year

•Country oforigin ofthe study,with 13 categories:

USA, Sweden, UK, Turkey, the Netherlands, Canada,

Australia,China,Korea,Iran,South Africa,Mexico

and Jordan

The methodologicalcharacteristicsincludedthe

following:

•Study design type,with six categories:descriptive,

quasi-experimental,experimental,qualitative,mixed

methodology, analysis

•Sample type, with four categories: nursing students,

working nurses, nursing teachers, nursing managers

•Sample size, defined by the range between lowest

highest values

•Aim of the study, with four categories according to

main topic ofthe study:evaluation ofstrategies for

advancing CT, evaluation of the components of CT

nursing students and working nurses, perception o

in students, analysis of the factors that influence C

For this last category the following subcategories w

identified:workplace,clinicalcompetence,nursing

process, self-sufficiency, clinicaljudgment, diagnostic

precision

RESULTS

Description of the studies

Analysis of the annual distribution of publications on

revealed increasing interest in this subject in recent

with a notable surge of production in the year 2010,

be seen in the details of the MEDLINE search by pub

tion date (Fig. 2).

In terms ofthe country oforigin ofthe studies, the

majority were carried out in the USA (n = 66; 73.3%

Europe was the second most productive source of ar

(n = 20; 22.2%), divided among Sweden (n = 7; 7.7%

the UK (n = 6; 6.6%), Turkey (n = 5; 5.5%) and the

Number of citations identified in the

databases

(n =1510)

MEDLINE

(n =1297)

Cochrane

(n = 10)

CINAHL

(n = 200)

LILACS

(n = 3)

Number of citations identified in

the secondary search

(n = 8)

Number of duplicate citations

eliminated (n = 93)

Number of citations screened

(n = 1425)

Citations eliminated following

analysis of title and abstract

(n = 1285)

Articles with complete text

analyzed

(n = 140)

Articles excluded following

analysis of complete text

(n = 50)

Articles included in the review

(n = 90)

Reasons for exclusion

The subject is not the aim of the review (n = 43)

Not found in due time (n = 2)

Not relevant (n = 5)

Screening IdentificationEligibilityInclusion

Figure 1.Flowchartof the resultsof the

search according to the PRISMA standard.

Critical thinking in nursing 3

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

abstracts of the remaining 1425 citations. The 155 docu-

ments that passed this filter were then subjected to further

screening based on a reading of the complete text, which

led to the elimination of an additional50 papers. In the

end 90 articles were included in the review.

Analysis was carried out in two stages. First, descrip-

tive aspectsof the studieswere analysed,and then a

topical analysis of the studies was carried out.

The variablesstudied included the productivity and

methodological characteristics of the sample.

The productivity characteristics included the following:

•Number of articles by year

•Country oforigin ofthe study,with 13 categories:

USA, Sweden, UK, Turkey, the Netherlands, Canada,

Australia,China,Korea,Iran,South Africa,Mexico

and Jordan

The methodologicalcharacteristicsincludedthe

following:

•Study design type,with six categories:descriptive,

quasi-experimental,experimental,qualitative,mixed

methodology, analysis

•Sample type, with four categories: nursing students,

working nurses, nursing teachers, nursing managers

•Sample size, defined by the range between lowest

highest values

•Aim of the study, with four categories according to

main topic ofthe study:evaluation ofstrategies for

advancing CT, evaluation of the components of CT

nursing students and working nurses, perception o

in students, analysis of the factors that influence C

For this last category the following subcategories w

identified:workplace,clinicalcompetence,nursing

process, self-sufficiency, clinicaljudgment, diagnostic

precision

RESULTS

Description of the studies

Analysis of the annual distribution of publications on

revealed increasing interest in this subject in recent

with a notable surge of production in the year 2010,

be seen in the details of the MEDLINE search by pub

tion date (Fig. 2).

In terms ofthe country oforigin ofthe studies, the

majority were carried out in the USA (n = 66; 73.3%

Europe was the second most productive source of ar

(n = 20; 22.2%), divided among Sweden (n = 7; 7.7%

the UK (n = 6; 6.6%), Turkey (n = 5; 5.5%) and the

Number of citations identified in the

databases

(n =1510)

MEDLINE

(n =1297)

Cochrane

(n = 10)

CINAHL

(n = 200)

LILACS

(n = 3)

Number of citations identified in

the secondary search

(n = 8)

Number of duplicate citations

eliminated (n = 93)

Number of citations screened

(n = 1425)

Citations eliminated following

analysis of title and abstract

(n = 1285)

Articles with complete text

analyzed

(n = 140)

Articles excluded following

analysis of complete text

(n = 50)

Articles included in the review

(n = 90)

Reasons for exclusion

The subject is not the aim of the review (n = 43)

Not found in due time (n = 2)

Not relevant (n = 5)

Screening IdentificationEligibilityInclusion

Figure 1.Flowchartof the resultsof the

search according to the PRISMA standard.

Critical thinking in nursing 3

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Netherlands (n = 2; 2.2%). Other studies were carried

out in Canada (n = 7; 7.7%), Australia (n = 4; 4.4%),

China (n = 5; 5.5%), Korea (n = 1; 1.1%), Iran (n = 1;

1.1%),South Africa(n = 1;1.1%),Mexico (n = 1;

1.1%) and Jordan (n = 1; 1.1%).

In terms of the type of study design, the percentages

were as follows:the greatestnumber were descriptive

(n = 32; 35.5%), geared toward evaluating educational

strategies for advancing CT, measuring CT skills in stu-

dentsand analysingfactorsrelated to CT.In lesser

numberswere quasi-experimentalstudies(n = 10;

11.5%), experimental studies (n = 6; 6.6%) and studies

with mixed methodology (n = 5;5.5%).These design

typeswere used to evaluate the impactof educational

initiatives on the CT skills of students. Next were quali-

tative studies (n = 17; 18.8%), which focused principally

on exploring the perception of CT in students.

Finally,analyticalarticles (n = 20;22.2%) explored

various aspects of CT.

As to the populations under study, CT was examined

mainly in nursing studentsamplesatvariousstagesof

training(n = 42;48.8%)and lessso in samplesof

workingnurses(n = 16;17.7%),nursingteachers

(n = 3; 3.3%) and nursing managers (n = 1; 1.1%).

Sample size ranged from 6 to 2144, depending on the

research design (Table 2).

Regarding the main topics of the studies, the following

focuses of interest were identified: (i) evaluation of strat-

egiesfor promoting CT in the field ofeducation,(ii)

evaluation of the CT of students or nurses by means of

variousmeasuring instruments,(iii) exploration ofthe

perception of CT in students and (iv) analysis of several

factors related to CT and their influence upon the results,

such astheworkplace,clinicalcompetence,nursing

Figure 2.Distribution of the recovered bibliographic references by

year of publication (January 1999–June 2013). Source: MEDLINE.

Table 2 Type of population studied and range of sample size by research design

Descriptive (n = 27)† Quasi-experimental

(n = 10)†

Experimental (n = 6)† Qualitative (n = 17)† Mixed methodology

(n = 5)†

n (%) SR n (%) SR n (%) SR n (%) SR n (%) SR

Nursing students‡ 19 (70.3) 120–350 9 (90.0) 13–163 3 (50.0) 31–100 — 11 (68.7) 7–36 3 (60.0) 8–53

Working nurses§ 7¶ (2.5) 14–2144 1 (10.0) 58 3 (50.0) 95–249 4 (25.0) 8–19 1 (20.0) 31

Nursing teachers — — — — — — 2 (12.5) 6–12 1 (20.0) 6–11

Nursing managers1†† (3.7) 12 — — — — — — — —

† Number of studies in which sample type is specified.‡ Students at different levels of studies.§ Nurses with varying levels of expertise.¶ In one study the sample included students and

working nurses.†† In one study the sample included working nurses and nursing managers. SR, sample range.

4 E Zuriguel Pérez et al.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

out in Canada (n = 7; 7.7%), Australia (n = 4; 4.4%),

China (n = 5; 5.5%), Korea (n = 1; 1.1%), Iran (n = 1;

1.1%),South Africa(n = 1;1.1%),Mexico (n = 1;

1.1%) and Jordan (n = 1; 1.1%).

In terms of the type of study design, the percentages

were as follows:the greatestnumber were descriptive

(n = 32; 35.5%), geared toward evaluating educational

strategies for advancing CT, measuring CT skills in stu-

dentsand analysingfactorsrelated to CT.In lesser

numberswere quasi-experimentalstudies(n = 10;

11.5%), experimental studies (n = 6; 6.6%) and studies

with mixed methodology (n = 5;5.5%).These design

typeswere used to evaluate the impactof educational

initiatives on the CT skills of students. Next were quali-

tative studies (n = 17; 18.8%), which focused principally

on exploring the perception of CT in students.

Finally,analyticalarticles (n = 20;22.2%) explored

various aspects of CT.

As to the populations under study, CT was examined

mainly in nursing studentsamplesatvariousstagesof

training(n = 42;48.8%)and lessso in samplesof

workingnurses(n = 16;17.7%),nursingteachers

(n = 3; 3.3%) and nursing managers (n = 1; 1.1%).

Sample size ranged from 6 to 2144, depending on the

research design (Table 2).

Regarding the main topics of the studies, the following

focuses of interest were identified: (i) evaluation of strat-

egiesfor promoting CT in the field ofeducation,(ii)

evaluation of the CT of students or nurses by means of

variousmeasuring instruments,(iii) exploration ofthe

perception of CT in students and (iv) analysis of several

factors related to CT and their influence upon the results,

such astheworkplace,clinicalcompetence,nursing

Figure 2.Distribution of the recovered bibliographic references by

year of publication (January 1999–June 2013). Source: MEDLINE.

Table 2 Type of population studied and range of sample size by research design

Descriptive (n = 27)† Quasi-experimental

(n = 10)†

Experimental (n = 6)† Qualitative (n = 17)† Mixed methodology

(n = 5)†

n (%) SR n (%) SR n (%) SR n (%) SR n (%) SR

Nursing students‡ 19 (70.3) 120–350 9 (90.0) 13–163 3 (50.0) 31–100 — 11 (68.7) 7–36 3 (60.0) 8–53

Working nurses§ 7¶ (2.5) 14–2144 1 (10.0) 58 3 (50.0) 95–249 4 (25.0) 8–19 1 (20.0) 31

Nursing teachers — — — — — — 2 (12.5) 6–12 1 (20.0) 6–11

Nursing managers1†† (3.7) 12 — — — — — — — —

† Number of studies in which sample type is specified.‡ Students at different levels of studies.§ Nurses with varying levels of expertise.¶ In one study the sample included students and

working nurses.†† In one study the sample included working nurses and nursing managers. SR, sample range.

4 E Zuriguel Pérez et al.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

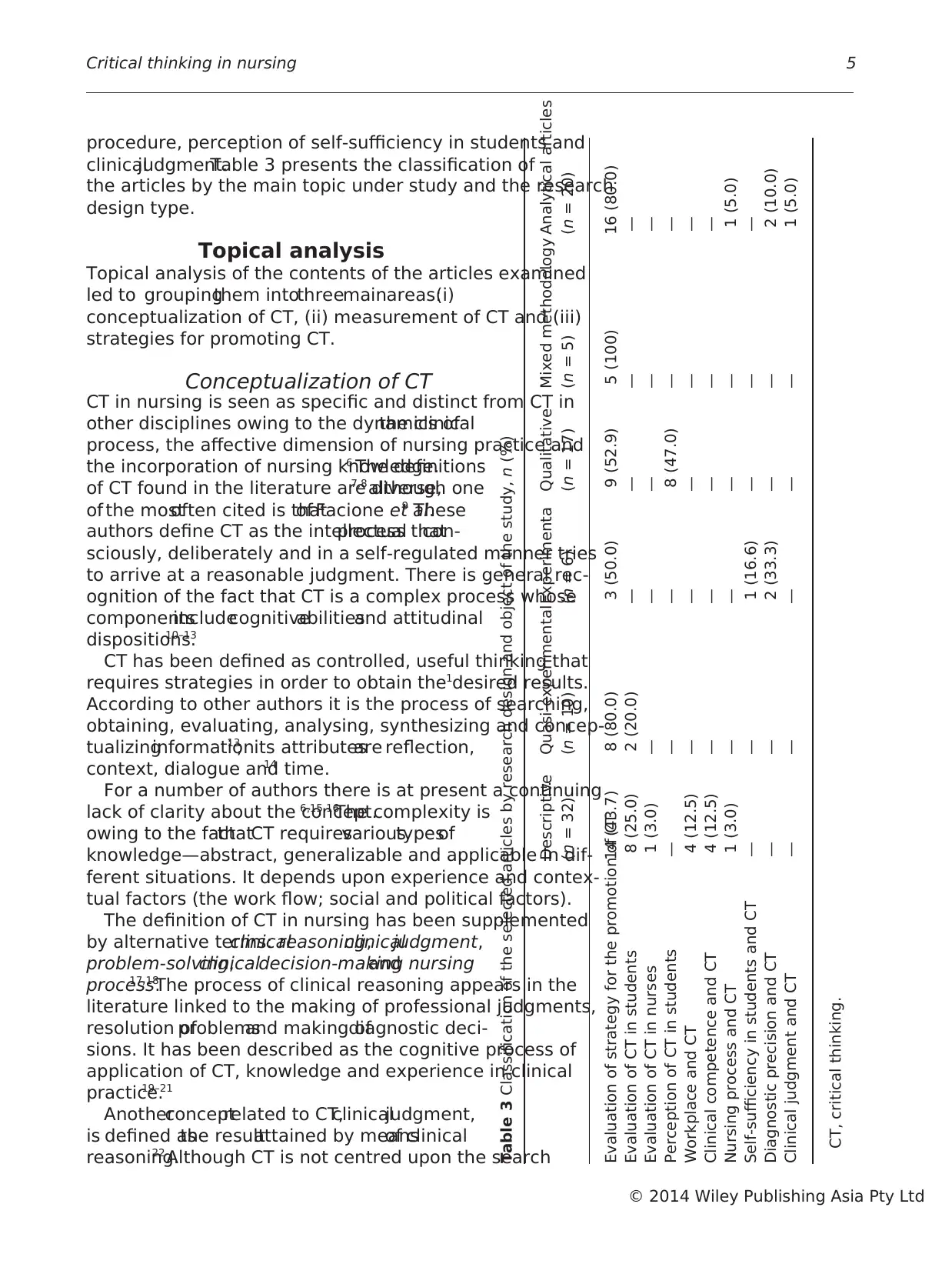

procedure, perception of self-sufficiency in students and

clinicaljudgment.Table 3 presents the classification of

the articles by the main topic under study and the research

design type.

Topical analysis

Topical analysis of the contents of the articles examined

led to groupingthem intothreemainareas:(i)

conceptualization of CT, (ii) measurement of CT and (iii)

strategies for promoting CT.

Conceptualization of CT

CT in nursing is seen as specific and distinct from CT in

other disciplines owing to the dynamics ofthe clinical

process, the affective dimension of nursing practice and

the incorporation of nursing knowledge.6 The definitions

of CT found in the literature are diverse,7,8although one

of the mostoften cited is thatof Facione et al.9 These

authors define CT as the intellectualprocess thatcon-

sciously, deliberately and in a self-regulated manner tries

to arrive at a reasonable judgment. There is general rec-

ognition of the fact that CT is a complex process whose

componentsincludecognitiveabilitiesand attitudinal

dispositions.10–13

CT has been defined as controlled, useful thinking that

requires strategies in order to obtain the desired results.1

According to other authors it is the process of searching,

obtaining, evaluating, analysing, synthesizing and concep-

tualizinginformation13

; its attributesare reflection,

context, dialogue and time.14

For a number of authors there is at present a continuing

lack of clarity about the concept.6,15,16

The complexity is

owing to the factthatCT requiresvarioustypesof

knowledge—abstract, generalizable and applicable in dif-

ferent situations. It depends upon experience and contex-

tual factors (the work flow; social and political factors).

The definition of CT in nursing has been supplemented

by alternative terms:clinicalreasoning,clinicaljudgment,

problem-solving,clinicaldecision-makingand nursing

process.17,18

The process of clinical reasoning appears in the

literature linked to the making of professional judgments,

resolution ofproblemsand making ofdiagnostic deci-

sions. It has been described as the cognitive process of

application of CT, knowledge and experience in clinical

practice.19–21

Anotherconceptrelated to CT,clinicaljudgment,

is defined asthe resultattained by meansof clinical

reasoning.22 Although CT is not centred upon the search

Table 3 Classification of the selected articles by research design and object of the study, n (%)

Descriptive

(n = 32)

Quasi-experimental

(n = 10)

Experimenta

(n = 6)

Qualitative

(n = 17)

Mixed methodology

(n = 5)

Analytical articles

(n = 20)

Evaluation of strategy for the promotion of CT14 (43.7) 8 (80.0) 3 (50.0) 9 (52.9) 5 (100) 16 (80.0)

Evaluation of CT in students 8 (25.0) 2 (20.0) — — — —

Evaluation of CT in nurses 1 (3.0) — — — — —

Perception of CT in students — — — 8 (47.0) — —

Workplace and CT 4 (12.5) — — — — —

Clinical competence and CT 4 (12.5) — — — — —

Nursing process and CT 1 (3.0) — — — — 1 (5.0)

Self-sufficiency in students and CT — — 1 (16.6) — — —

Diagnostic precision and CT — — 2 (33.3) — — 2 (10.0)

Clinical judgment and CT — — — — — 1 (5.0)

CT, critical thinking.

Critical thinking in nursing 5

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

clinicaljudgment.Table 3 presents the classification of

the articles by the main topic under study and the research

design type.

Topical analysis

Topical analysis of the contents of the articles examined

led to groupingthem intothreemainareas:(i)

conceptualization of CT, (ii) measurement of CT and (iii)

strategies for promoting CT.

Conceptualization of CT

CT in nursing is seen as specific and distinct from CT in

other disciplines owing to the dynamics ofthe clinical

process, the affective dimension of nursing practice and

the incorporation of nursing knowledge.6 The definitions

of CT found in the literature are diverse,7,8although one

of the mostoften cited is thatof Facione et al.9 These

authors define CT as the intellectualprocess thatcon-

sciously, deliberately and in a self-regulated manner tries

to arrive at a reasonable judgment. There is general rec-

ognition of the fact that CT is a complex process whose

componentsincludecognitiveabilitiesand attitudinal

dispositions.10–13

CT has been defined as controlled, useful thinking that

requires strategies in order to obtain the desired results.1

According to other authors it is the process of searching,

obtaining, evaluating, analysing, synthesizing and concep-

tualizinginformation13

; its attributesare reflection,

context, dialogue and time.14

For a number of authors there is at present a continuing

lack of clarity about the concept.6,15,16

The complexity is

owing to the factthatCT requiresvarioustypesof

knowledge—abstract, generalizable and applicable in dif-

ferent situations. It depends upon experience and contex-

tual factors (the work flow; social and political factors).

The definition of CT in nursing has been supplemented

by alternative terms:clinicalreasoning,clinicaljudgment,

problem-solving,clinicaldecision-makingand nursing

process.17,18

The process of clinical reasoning appears in the

literature linked to the making of professional judgments,

resolution ofproblemsand making ofdiagnostic deci-

sions. It has been described as the cognitive process of

application of CT, knowledge and experience in clinical

practice.19–21

Anotherconceptrelated to CT,clinicaljudgment,

is defined asthe resultattained by meansof clinical

reasoning.22 Although CT is not centred upon the search

Table 3 Classification of the selected articles by research design and object of the study, n (%)

Descriptive

(n = 32)

Quasi-experimental

(n = 10)

Experimenta

(n = 6)

Qualitative

(n = 17)

Mixed methodology

(n = 5)

Analytical articles

(n = 20)

Evaluation of strategy for the promotion of CT14 (43.7) 8 (80.0) 3 (50.0) 9 (52.9) 5 (100) 16 (80.0)

Evaluation of CT in students 8 (25.0) 2 (20.0) — — — —

Evaluation of CT in nurses 1 (3.0) — — — — —

Perception of CT in students — — — 8 (47.0) — —

Workplace and CT 4 (12.5) — — — — —

Clinical competence and CT 4 (12.5) — — — — —

Nursing process and CT 1 (3.0) — — — — 1 (5.0)

Self-sufficiency in students and CT — — 1 (16.6) — — —

Diagnostic precision and CT — — 2 (33.3) — — 2 (10.0)

Clinical judgment and CT — — — — — 1 (5.0)

CT, critical thinking.

Critical thinking in nursing 5

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

for a response, the resolution of problems seeks to obtain a

result.13,17,23,24

CT facilitatesthe making ofdecisions,

understood as the systematic process ofevaluating and

deciding that contributes to obtaining a desired result.19

Another concept linked with CT is the nursing process.

This is a cognitive process that involves the use of CT skills

to obtain desired results. The nursing process constitutes

the basis of CT skills in nursing.25,26

Measuring CT

Six standardized instruments for evaluating CT in nursing

studentsand working nurseshave been identified:the

CaliforniaCriticalThinkingDispositionInventory

(CCTDI),the CaliforniaCriticalThinking SkillsTest

(CCTST), the Health Science Reasoning Test (HSRT), the

Watson–Glaser CriticalThinking Appraisal(WGCTA),

thePerformance-Based DevelopmentSystem (PBDS)

and the CriticalThinking Diagnostic(CTD).Table 4

presents the measuring instruments.

In the studiesusinga quantitativemethodology

(n = 53; 5.8%), the CCTDI27 was the most frequently

used instrument (n = 8; 15.0%) for examining the dispo-

sition of nursing students,28–31

working nurses,32,33

nursing

managers7 and nursing teachers.34

The CCTST35(n = 4; 7.5%) was used to measure the

CT skillsof nursing students,36,37postgraduate nursing

students38 and recently graduated nurses.39

The HSRT,40designed to evaluate the CT skills of stu-

dents and professionals in the health sciences, was used in

one study (n = 1; 1.8%) for construct validation.21

Other research studies (n = 4; 7.5%) have employed

the WGCTA41 as an instrument in the evaluation of the

CT skillsof studentsamples42 and ofworking nurse

samples.23,43,44

With the aim ofjointly analysing disposition and CT

skill,someauthorshaveusedtheCCTDI andthe

CCTST15,34,45–47

(n = 5;9.4%),offering as a resultthe

positive correlation between the two instruments. Others

have used the CCTDI and the WGTCA48,49

(n = 2; 3.7%)

without,however,finding statistically significantrela-

tions. The studies that used the CCTDI and the HSRT50–52

(n = 3; 9.6%) did not provide information on the corre-

lation between the two instruments.

Finally, there are two instruments that were used to

evaluate nursing competence in terms ofCT skills, the

PBDS53 (n = 1; 1.8%) and the CTD54 (n = 1; 1.8%).

It will be noted that several instruments are frequently

combined in the same study in order to analyse factors

influencingCT, such as expertise,55 educational

level,23,50,56

failure to rescue,56 self-confidence,50,57

learn-

ing style,19 self-esteem,52 work complexity,57 levelof

anxiety,58 job satisfaction59 and diagnostic precision.32,60

Faced with the choice ofinstruments,some authors

have opted for using alternative methods ofevaluation,

suchas therubric,61,62 theconceptmap,63 thecase

study64,65

and the questionnaire.57,66,67

From theyear2000 onward,variousresearchers

focusedtheirattentionon an evaluationof CT by

meansof qualitativemethods,usingsemistructured

interviews,68–70group discussions,62 online discussions71

and questionnaires.72,73

Strategies for promoting CT

There is interest in developing postgraduate and m

training programs that include specific strategies fo

development of CT skills in nursing students. The m

frequently analysed strategies are simulations usin

tomicalmodels, questioning, group dynamics, reflecti

diaries, the creating of concept maps and teaching

focused on reasoning.

Studies thathave used simulation as a didactic tech-

nique have posted good results in the development

skillsand dispositionsin nursing students74–78 and in

working nurses,56 with the exception of two studies that

failed to find significantresultsfollowing exposure to

simulation.79 Other studies have linked simulation with

the development of clinical judgment,61especially follow-

ing post-simulation debriefings.80

The use of questioning as a didactic technique en

ages reflection and stimulates CT in students6,81,82

and in

inexperienced nurses.65,83

Group dynamics encourages the development ofCT

skillsin students6 without,however,showingany

improvement among working nurses.36

The reflective diary is reported to be an effective

egy for increasing CT skillsin students6,57,65in thatit

encourages reflection, the assimilation ofnewly learned

material and the creation of new knowledge.

The concept map is an analytical tool that helps i

synthesizing, organizing and prioritizing of data in a

sequence. Some studies opted for using the concep

to encourage the development of CT skills, which b

positive results among both students37,67,80

and beginning

nurses.66

The use ofeducationalmodels focused on reasoning

provedeffectivein developingCT skills.Examples

6 E Zuriguel Pérez et al.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

result.13,17,23,24

CT facilitatesthe making ofdecisions,

understood as the systematic process ofevaluating and

deciding that contributes to obtaining a desired result.19

Another concept linked with CT is the nursing process.

This is a cognitive process that involves the use of CT skills

to obtain desired results. The nursing process constitutes

the basis of CT skills in nursing.25,26

Measuring CT

Six standardized instruments for evaluating CT in nursing

studentsand working nurseshave been identified:the

CaliforniaCriticalThinkingDispositionInventory

(CCTDI),the CaliforniaCriticalThinking SkillsTest

(CCTST), the Health Science Reasoning Test (HSRT), the

Watson–Glaser CriticalThinking Appraisal(WGCTA),

thePerformance-Based DevelopmentSystem (PBDS)

and the CriticalThinking Diagnostic(CTD).Table 4

presents the measuring instruments.

In the studiesusinga quantitativemethodology

(n = 53; 5.8%), the CCTDI27 was the most frequently

used instrument (n = 8; 15.0%) for examining the dispo-

sition of nursing students,28–31

working nurses,32,33

nursing

managers7 and nursing teachers.34

The CCTST35(n = 4; 7.5%) was used to measure the

CT skillsof nursing students,36,37postgraduate nursing

students38 and recently graduated nurses.39

The HSRT,40designed to evaluate the CT skills of stu-

dents and professionals in the health sciences, was used in

one study (n = 1; 1.8%) for construct validation.21

Other research studies (n = 4; 7.5%) have employed

the WGCTA41 as an instrument in the evaluation of the

CT skillsof studentsamples42 and ofworking nurse

samples.23,43,44

With the aim ofjointly analysing disposition and CT

skill,someauthorshaveusedtheCCTDI andthe

CCTST15,34,45–47

(n = 5;9.4%),offering as a resultthe

positive correlation between the two instruments. Others

have used the CCTDI and the WGTCA48,49

(n = 2; 3.7%)

without,however,finding statistically significantrela-

tions. The studies that used the CCTDI and the HSRT50–52

(n = 3; 9.6%) did not provide information on the corre-

lation between the two instruments.

Finally, there are two instruments that were used to

evaluate nursing competence in terms ofCT skills, the

PBDS53 (n = 1; 1.8%) and the CTD54 (n = 1; 1.8%).

It will be noted that several instruments are frequently

combined in the same study in order to analyse factors

influencingCT, such as expertise,55 educational

level,23,50,56

failure to rescue,56 self-confidence,50,57

learn-

ing style,19 self-esteem,52 work complexity,57 levelof

anxiety,58 job satisfaction59 and diagnostic precision.32,60

Faced with the choice ofinstruments,some authors

have opted for using alternative methods ofevaluation,

suchas therubric,61,62 theconceptmap,63 thecase

study64,65

and the questionnaire.57,66,67

From theyear2000 onward,variousresearchers

focusedtheirattentionon an evaluationof CT by

meansof qualitativemethods,usingsemistructured

interviews,68–70group discussions,62 online discussions71

and questionnaires.72,73

Strategies for promoting CT

There is interest in developing postgraduate and m

training programs that include specific strategies fo

development of CT skills in nursing students. The m

frequently analysed strategies are simulations usin

tomicalmodels, questioning, group dynamics, reflecti

diaries, the creating of concept maps and teaching

focused on reasoning.

Studies thathave used simulation as a didactic tech-

nique have posted good results in the development

skillsand dispositionsin nursing students74–78 and in

working nurses,56 with the exception of two studies that

failed to find significantresultsfollowing exposure to

simulation.79 Other studies have linked simulation with

the development of clinical judgment,61especially follow-

ing post-simulation debriefings.80

The use of questioning as a didactic technique en

ages reflection and stimulates CT in students6,81,82

and in

inexperienced nurses.65,83

Group dynamics encourages the development ofCT

skillsin students6 without,however,showingany

improvement among working nurses.36

The reflective diary is reported to be an effective

egy for increasing CT skillsin students6,57,65in thatit

encourages reflection, the assimilation ofnewly learned

material and the creation of new knowledge.

The concept map is an analytical tool that helps i

synthesizing, organizing and prioritizing of data in a

sequence. Some studies opted for using the concep

to encourage the development of CT skills, which b

positive results among both students37,67,80

and beginning

nurses.66

The use ofeducationalmodels focused on reasoning

provedeffectivein developingCT skills.Examples

6 E Zuriguel Pérez et al.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Table 4 Description of the instruments used to measure critical thinking.

Instrument Dimensions and items Scoring scale Means of

administering

Time (min)

to administer

Psychometric characteristics

California Critical Thinking Disposition

Inventory, Facione & Facione (1992)27

7 dimensions (75 items)

• Search for truth

• Mental breadth

• Willingness to analyse

• Willingness to systematize

• Self-confidence in reasoning

• Curiosity

• Cognitive maturity

Six-point Likert Self-reporting 15–20 Internal consistency: α = 0.90,27α = 0.7127

;

α = 0.7430(Danish); α = 0.8729(Arabic)

Content validity confirmed by panel of experts27

California Critical Thinking Skills Test

(Forms A and B),

Facione (1990)

5 dimensions (34 items)

• Analysis

• Evaluation

• Inference

• Deductive reasoning

• Inductive reasoning

Multiple choice; context:

everyday situations.

Self-reporting 45 Internal consistency: Forms A and B KR-20 = 0.70,35

0.8435

Content validity confirmed by panel of experts32

Health Science Reasoning Test, Facione (2006)40 dimensions (33 items)

• Analysis

• Evaluation

• Inference

• Deductive reasoning

• Inductive reasoning

Multiple choice; context:

health science situations.

Self-reporting 50 Internal consistency: KR-20 = 0.8140

Content validity confirmed by panel of experts40

Watson–Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal

(Forms A and B), Watson and Glaser (1991)41

5 dimensions (long version 80 items, short

version 40 items)

• Inference

• Recognition of assumptions

• Deduction

• Interpretation

• Evaluation of arguments

Multiple choice Self-reporting 45 Internal consistency: Forms A and B α = 0.45, 0.6941

;

α = 0.8544

, 0.7144 (Taiwan version)

Correlation coefficient: Forms A and B 0.21, 0.5041

Perfomance-Based Development

System, Del Bueno (1990)53

3 dimensions

• CT skills

• Interpersonal skills

• Technical skills

Responses in

narrative form

Vignettes 240 Equivalence reliability: 94%53

Critical Thinking Diagnostic, Berkow et al. (2011)54 5 dimensions (25 items)

• Problem recognition

• Clinical decision-making

• Prioritization

• Clinical application

• Reflection

Six-point Likert Self-reporting 15 Internal consistency: α = 0.9754

Correlation coefficient: 0.9354

Content validity confirmed by panel of experts54

KR-20, Kuder–Richardson; α, Cronbach’s alpha.

Critical thinking in nursing 7

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Instrument Dimensions and items Scoring scale Means of

administering

Time (min)

to administer

Psychometric characteristics

California Critical Thinking Disposition

Inventory, Facione & Facione (1992)27

7 dimensions (75 items)

• Search for truth

• Mental breadth

• Willingness to analyse

• Willingness to systematize

• Self-confidence in reasoning

• Curiosity

• Cognitive maturity

Six-point Likert Self-reporting 15–20 Internal consistency: α = 0.90,27α = 0.7127

;

α = 0.7430(Danish); α = 0.8729(Arabic)

Content validity confirmed by panel of experts27

California Critical Thinking Skills Test

(Forms A and B),

Facione (1990)

5 dimensions (34 items)

• Analysis

• Evaluation

• Inference

• Deductive reasoning

• Inductive reasoning

Multiple choice; context:

everyday situations.

Self-reporting 45 Internal consistency: Forms A and B KR-20 = 0.70,35

0.8435

Content validity confirmed by panel of experts32

Health Science Reasoning Test, Facione (2006)40 dimensions (33 items)

• Analysis

• Evaluation

• Inference

• Deductive reasoning

• Inductive reasoning

Multiple choice; context:

health science situations.

Self-reporting 50 Internal consistency: KR-20 = 0.8140

Content validity confirmed by panel of experts40

Watson–Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal

(Forms A and B), Watson and Glaser (1991)41

5 dimensions (long version 80 items, short

version 40 items)

• Inference

• Recognition of assumptions

• Deduction

• Interpretation

• Evaluation of arguments

Multiple choice Self-reporting 45 Internal consistency: Forms A and B α = 0.45, 0.6941

;

α = 0.8544

, 0.7144 (Taiwan version)

Correlation coefficient: Forms A and B 0.21, 0.5041

Perfomance-Based Development

System, Del Bueno (1990)53

3 dimensions

• CT skills

• Interpersonal skills

• Technical skills

Responses in

narrative form

Vignettes 240 Equivalence reliability: 94%53

Critical Thinking Diagnostic, Berkow et al. (2011)54 5 dimensions (25 items)

• Problem recognition

• Clinical decision-making

• Prioritization

• Clinical application

• Reflection

Six-point Likert Self-reporting 15 Internal consistency: α = 0.9754

Correlation coefficient: 0.9354

Content validity confirmed by panel of experts54

KR-20, Kuder–Richardson; α, Cronbach’s alpha.

Critical thinking in nursing 7

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

include the Developing Nurses’ Thinking Model,60Struc-

tured Observation and Assessmentof Practice,55 Paul’s

Modelof CriticalThinking,84 and the ClinicalJudgment

Model.85

Learning based on problems86,87was introduced into

nurse training as a method for promoting the develop-

ment of CT, the acquisition of knowledge and the devel-

opmentof the ability to resolve problemsand make

decisions.However,the resultsof a recentsystematic

review yielded no evidence of improvement in CT among

nursing students.88

Furthermore, orientation programs have yielded satis-

factory results in the developmentof CT skills among

nurses starting out in their careers.59

Finally,some studies have provided evidence ofthe

contribution of information technology and communica-

tion technology in fostering CT.71,89

DISCUSSION

The presentscoping review ofthe conceptof CT in

nursing and related concepts has clearly shown this to be

an area of interest in nursing, even though it has turned up

a number of difficulties in researching the topic.

Regarding the conceptualization of CT, we found, as

have other previous reviews,90,91

that there is no univer-

sally accepted conceptualframework for describing and

evaluating CT in nursing.The studies suggestthatthe

conceptualization ofCT needsto be consolidated and

adapted beyond the merely theoreticalto the current

health-care system and the clinical environment. There is

a need for clarification of the terminology related to CT

used in the literature.

As for the measurement of CT, we found, as did prior

reviews,92,93 thatthecurrentlyavailablestandardized

instrumentsare notsensitive formeasurementin the

nursing discipline.

CT hasbeen identified asan essentialelementin

nursing practice, yet there is little evidence that there is

regular evaluation of CT competence.

CT applied to clinical practice encourages professional

activity based on evidence and advances those aspects of

the profession related to competence. The acquisition of

CT skills, in bringing about safer, more competent care,

could serve to improve diagnostic precision and decision-

making, yielding more favorable outcomes for patients.

Nevertheless,ourreview ofthe literature hasshown

there to be only a limited number ofstudies exploring

CT in clinicalpractice.It mightbe the casethat

optimized CT skills improve the quality of patient ca

but the exact relation between CT and outcomes re

unclear.

Finally,asto the strategiesfor advancing CT,we

found, as have other researchers, inconsistent conc

regarding the evaluation ofteaching and learning strat-

egies for nursing students.48 This might be owing to the

complexity of the construct and to the lack of a con

modelof CT that would permit its evaluation in allits

dimensions. The nursing profession has not adopted

evaluation standard for CT,which makesit extremely

difficultto generalize results.In orderto be able to

improve CT skills in the clinical setting specific stre

and weaknesses need to be identified.

The challenge for the future of research into CT li

focusing on the developmentof models and evaluation

instruments that are specific to the discipline of nur

and in analysing those factors that encourage and t

that inhibit the acquisition of CT, so as to develop s

egies to foster CT in clinical practice.

REFERENCES

1 Alfaro-LeFevre R. CriticalThinking, ClinicalReasoning, and

ClinicalJudgment:A PracticalApproach, 5th edn. St. Louis,

MO, USA: Saunders/Elsevier, 2013.

2 NationalLeague for Nursing. Criteria and Guidelines for

Evaluation ofBaccalaureateNursing Programs.Washington,

DC: Councilof Baccalaureate and HigherDegree Pro-

grams, National League for Nursing, 1991.

3 Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Orga

zations; Joint Commission on Accreditation ofHospitals.

Accreditation ManualforHospitals.Oakbrook Terrace,IL,

USA: The Joint Commission, 1993.

4 Lunney M. CriticalThinking to Achieve Positive Health Out

comes: Nursing Case Studies and Analyses. Ames, IA,

Wiley & Sons, 2013.

5 Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA stat

ment for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analy

studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explan

and elaboration.BMJ(ClinicalResearch Ed.)2009;339:

b2700.

6 TwibellR, Ryan M,Hermiz M.Faculty perceptionsof

critical thinking in student clinical experiences. The Jo

of Nursing Education 2005; 44: 71–79.

7 ZoriS, Morrison B. Criticalthinking in nurse managers.

Nursing Economic$ 2009; 27: 75–79, 98.

8 RiddellT. Criticalassumptions: Thinking critically about

critical thinking. The Journal of Nursing Education 200

121–126.

8 E Zuriguel Pérez et al.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

tured Observation and Assessmentof Practice,55 Paul’s

Modelof CriticalThinking,84 and the ClinicalJudgment

Model.85

Learning based on problems86,87was introduced into

nurse training as a method for promoting the develop-

ment of CT, the acquisition of knowledge and the devel-

opmentof the ability to resolve problemsand make

decisions.However,the resultsof a recentsystematic

review yielded no evidence of improvement in CT among

nursing students.88

Furthermore, orientation programs have yielded satis-

factory results in the developmentof CT skills among

nurses starting out in their careers.59

Finally,some studies have provided evidence ofthe

contribution of information technology and communica-

tion technology in fostering CT.71,89

DISCUSSION

The presentscoping review ofthe conceptof CT in

nursing and related concepts has clearly shown this to be

an area of interest in nursing, even though it has turned up

a number of difficulties in researching the topic.

Regarding the conceptualization of CT, we found, as

have other previous reviews,90,91

that there is no univer-

sally accepted conceptualframework for describing and

evaluating CT in nursing.The studies suggestthatthe

conceptualization ofCT needsto be consolidated and

adapted beyond the merely theoreticalto the current

health-care system and the clinical environment. There is

a need for clarification of the terminology related to CT

used in the literature.

As for the measurement of CT, we found, as did prior

reviews,92,93 thatthecurrentlyavailablestandardized

instrumentsare notsensitive formeasurementin the

nursing discipline.

CT hasbeen identified asan essentialelementin

nursing practice, yet there is little evidence that there is

regular evaluation of CT competence.

CT applied to clinical practice encourages professional

activity based on evidence and advances those aspects of

the profession related to competence. The acquisition of

CT skills, in bringing about safer, more competent care,

could serve to improve diagnostic precision and decision-

making, yielding more favorable outcomes for patients.

Nevertheless,ourreview ofthe literature hasshown

there to be only a limited number ofstudies exploring

CT in clinicalpractice.It mightbe the casethat

optimized CT skills improve the quality of patient ca

but the exact relation between CT and outcomes re

unclear.

Finally,asto the strategiesfor advancing CT,we

found, as have other researchers, inconsistent conc

regarding the evaluation ofteaching and learning strat-

egies for nursing students.48 This might be owing to the

complexity of the construct and to the lack of a con

modelof CT that would permit its evaluation in allits

dimensions. The nursing profession has not adopted

evaluation standard for CT,which makesit extremely

difficultto generalize results.In orderto be able to

improve CT skills in the clinical setting specific stre

and weaknesses need to be identified.

The challenge for the future of research into CT li

focusing on the developmentof models and evaluation

instruments that are specific to the discipline of nur

and in analysing those factors that encourage and t

that inhibit the acquisition of CT, so as to develop s

egies to foster CT in clinical practice.

REFERENCES

1 Alfaro-LeFevre R. CriticalThinking, ClinicalReasoning, and

ClinicalJudgment:A PracticalApproach, 5th edn. St. Louis,

MO, USA: Saunders/Elsevier, 2013.

2 NationalLeague for Nursing. Criteria and Guidelines for

Evaluation ofBaccalaureateNursing Programs.Washington,

DC: Councilof Baccalaureate and HigherDegree Pro-

grams, National League for Nursing, 1991.

3 Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Orga

zations; Joint Commission on Accreditation ofHospitals.

Accreditation ManualforHospitals.Oakbrook Terrace,IL,

USA: The Joint Commission, 1993.

4 Lunney M. CriticalThinking to Achieve Positive Health Out

comes: Nursing Case Studies and Analyses. Ames, IA,

Wiley & Sons, 2013.

5 Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA stat

ment for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analy

studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explan

and elaboration.BMJ(ClinicalResearch Ed.)2009;339:

b2700.

6 TwibellR, Ryan M,Hermiz M.Faculty perceptionsof

critical thinking in student clinical experiences. The Jo

of Nursing Education 2005; 44: 71–79.

7 ZoriS, Morrison B. Criticalthinking in nurse managers.

Nursing Economic$ 2009; 27: 75–79, 98.

8 RiddellT. Criticalassumptions: Thinking critically about

critical thinking. The Journal of Nursing Education 200

121–126.

8 E Zuriguel Pérez et al.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

9 Facione NC,Facione PA,Sanchez CA.Criticalthinking

disposition as a measure of competent clinical judgment: The

development of the California Critical Thinking Disposition

Inventory. The Journal of Nursing Education 1994; 33: 345–350.

10 Simpson E,Courtney M.A framework guiding critical

thinkingthroughreflectivejournaldocumentation:A

Middle Eastern experience. InternationalJournalofNursing

Practice 2007; 13: 203–208.

11 Allen GD,Rubenfeld MG,SchefferBK. Reliability of

assessment of critical thinking. Journal of Professional Nursing

2004; 20: 15–22.

12 Scheffer BK,Rubenfeld MG.A consensusstatementon

critical thinking in nursing. The Journal of Nursing Education

2000; 39: 352–359.

13 Özkahraman S¸, Yıldırım B. An overview of critical thinking

in nursing and education.American InternationalJournalof

Contemporary Research 2011; 1: 190–196.

14 Forneris SG. Exploring the attributes of critical thinking: A

conceptualbasis.InternationalJournalofNursing Education

Scholarship 2004; 181: 1548–1923.

15 Ravert P. Patient simulator sessions and criticalthinking.

The Journal of Nursing Education 2008; 47: 557–562.

16 Raymond-Seniuk C, Profetto-McGrath J. Can one learn to

think critically? A philosophicalexploration. Open Nursing

Journal 2011; 5: 45–51.

17 Turner P. Critical thinking in nursing education and prac-

tice as defined in the literature. Nursing Education Perspectives

2005; 26: 272–277.

18 EdwardsSL. Criticalthinking:A two-phase framework.

Nurse Education in Practice 2007; 7: 303–314.

19 Gillespie M,Peterson BL.Helping novice nursesmake

effective clinicaldecisions: The situated clinicaldecision-

making framework. Nursing Education Perspectives 2009; 30:

164–170.

20 Carr SM. A framework for understanding clinical reasoning

in community nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2004; 13:

850–857.

21 Huhn K, Black L, Jensen GM, Deutsch JE. Construct valid-

ity of the Health Science Reasoning Test. JournalofAllied

Health 2011; 40: 181–186.

22 Tanner CA. Thinking like a nurse: A research-based model

of clinical judgment in nursing. The Journal of Nursing Edu-

cation 2006; 45: 204–211.

23 Gloudemans HA, Schalk RMJD, Reynaert W. The relation-

ship between critical thinking skills and self-efficacy beliefs

in mentalhealth nurses. Nurse Education Today 2012; 33:

275–280.

24 Kataoka-Yahiro M, Saylor C. A critical thinking model for

nursing judgment. The Journal of Nursing Education1994; 33:

351–356.

25 Yildirim B,Ozkahraman S.Criticalthinking in nursing

process and education. International Journal of Humanities and

Social Science 2011; 1: 257–262.

26 Chabeli MM. Faciliting critical thinking within the nursin

processframework:A literaturereview.HealthSA

Gesondheid 2007; 12: 69–90.

27 Facione P, Facione N, Giancarlo CF. The California Critic

Thinking Disposition Inventory: CCTDI Test Manual. Mill

CA, USA: California Academic Press, 1992.

28 Stewart S, Dempsey LF. A longitudinal study of baccala

reate nursing students’criticalthinking dispositions.The

Journal of Nursing Education 2005; 44: 81–84.

29 Suliman WA. Criticalthinking and learning styles ofstu-

dents in conventional and accelerated programmes. Int

tional Nursing Review 2006; 53: 73–79.

30 Walsh CM,Seldomridge LA.Criticalthinking:Back to

square two. The Journal of Nursing Education 2006; 45

219.

31 Atay S, Karabacak U. Care plans using concept maps a

their effects on the critical thinking dispositions of nurs

students. InternationalJournalofNursing Practice 2012; 18:

233–239.

32 Wangensteen S, Johansson IS, Björkström ME, Nordströ

G. Research utilisation and criticalthinking among newly

graduated nurses: Predictors for research use. A quanti

tive cross-sectionalstudy. JournalofClinicalNursing 2011;

20: 2436–2447.

33 Wangensteen S, Johansson IS, Björkström ME, Nordströ

G. Criticalthinking dispositions among newly graduated

nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2010; 66: 2170–21

34 Raymond CL, Profetto-McGrath J. Nurse educators’ criti

calthinking: Reflection and measurement. Nurse Educat

in Practice 2005; 5: 209–217.

35 Facione PA. The California Critical Thinking Skills Test:

Level. Technical Report 1: Experimental Validation and

Validity.Millbrae,CA, USA:California Academic Press,

1990.

36 Sinatra-Wilhelm T. Nursing care plans versus concept m

in the enhancementof criticalthinking skillsin nursing

students enrolled in a baccalaureate nursing program.

tive Nursing 2012; 18: 78–84.

37 WheelerLA, CollinsSKR. The influenceof concept

mapping on criticalthinking in baccalaureate nursing stu-

dents. Journal of Professional Nursing 2003; 19: 339–34

38 RogalSM, Young J. Exploring criticalthinking in critical

care nursing education: A pilot study. Journal of Continu

Education in Nursing 2008; 39: 28–33.

39 Sorensen HAJ,Yankech LR.Precepting in the fastlane:

Improving critical thinking in new graduate nurses. Jour

of Continuing Education in Nursing 2008; 39: 208–216.

40 Facione N, Facione P. The Health Sciences Reasoning T

HSRT.Millbrae,CA, USA:CaliforniaAcademic Press,

2006.

41 Watson G,GlaserEM. Watson–GlaserCriticalThinking

Appraisal: British Manual: Forms A, B and C. San Anton

USA: Psychological Corporation, 1991.

Critical thinking in nursing 9

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

disposition as a measure of competent clinical judgment: The

development of the California Critical Thinking Disposition

Inventory. The Journal of Nursing Education 1994; 33: 345–350.

10 Simpson E,Courtney M.A framework guiding critical

thinkingthroughreflectivejournaldocumentation:A

Middle Eastern experience. InternationalJournalofNursing

Practice 2007; 13: 203–208.

11 Allen GD,Rubenfeld MG,SchefferBK. Reliability of

assessment of critical thinking. Journal of Professional Nursing

2004; 20: 15–22.

12 Scheffer BK,Rubenfeld MG.A consensusstatementon

critical thinking in nursing. The Journal of Nursing Education

2000; 39: 352–359.

13 Özkahraman S¸, Yıldırım B. An overview of critical thinking

in nursing and education.American InternationalJournalof

Contemporary Research 2011; 1: 190–196.

14 Forneris SG. Exploring the attributes of critical thinking: A

conceptualbasis.InternationalJournalofNursing Education

Scholarship 2004; 181: 1548–1923.

15 Ravert P. Patient simulator sessions and criticalthinking.

The Journal of Nursing Education 2008; 47: 557–562.

16 Raymond-Seniuk C, Profetto-McGrath J. Can one learn to

think critically? A philosophicalexploration. Open Nursing

Journal 2011; 5: 45–51.

17 Turner P. Critical thinking in nursing education and prac-

tice as defined in the literature. Nursing Education Perspectives

2005; 26: 272–277.

18 EdwardsSL. Criticalthinking:A two-phase framework.

Nurse Education in Practice 2007; 7: 303–314.

19 Gillespie M,Peterson BL.Helping novice nursesmake

effective clinicaldecisions: The situated clinicaldecision-

making framework. Nursing Education Perspectives 2009; 30:

164–170.

20 Carr SM. A framework for understanding clinical reasoning

in community nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2004; 13:

850–857.

21 Huhn K, Black L, Jensen GM, Deutsch JE. Construct valid-

ity of the Health Science Reasoning Test. JournalofAllied

Health 2011; 40: 181–186.

22 Tanner CA. Thinking like a nurse: A research-based model

of clinical judgment in nursing. The Journal of Nursing Edu-

cation 2006; 45: 204–211.

23 Gloudemans HA, Schalk RMJD, Reynaert W. The relation-

ship between critical thinking skills and self-efficacy beliefs

in mentalhealth nurses. Nurse Education Today 2012; 33:

275–280.

24 Kataoka-Yahiro M, Saylor C. A critical thinking model for

nursing judgment. The Journal of Nursing Education1994; 33:

351–356.

25 Yildirim B,Ozkahraman S.Criticalthinking in nursing

process and education. International Journal of Humanities and

Social Science 2011; 1: 257–262.

26 Chabeli MM. Faciliting critical thinking within the nursin

processframework:A literaturereview.HealthSA

Gesondheid 2007; 12: 69–90.

27 Facione P, Facione N, Giancarlo CF. The California Critic

Thinking Disposition Inventory: CCTDI Test Manual. Mill

CA, USA: California Academic Press, 1992.

28 Stewart S, Dempsey LF. A longitudinal study of baccala

reate nursing students’criticalthinking dispositions.The

Journal of Nursing Education 2005; 44: 81–84.

29 Suliman WA. Criticalthinking and learning styles ofstu-

dents in conventional and accelerated programmes. Int

tional Nursing Review 2006; 53: 73–79.

30 Walsh CM,Seldomridge LA.Criticalthinking:Back to

square two. The Journal of Nursing Education 2006; 45

219.

31 Atay S, Karabacak U. Care plans using concept maps a

their effects on the critical thinking dispositions of nurs

students. InternationalJournalofNursing Practice 2012; 18:

233–239.

32 Wangensteen S, Johansson IS, Björkström ME, Nordströ

G. Research utilisation and criticalthinking among newly

graduated nurses: Predictors for research use. A quanti

tive cross-sectionalstudy. JournalofClinicalNursing 2011;

20: 2436–2447.

33 Wangensteen S, Johansson IS, Björkström ME, Nordströ

G. Criticalthinking dispositions among newly graduated

nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2010; 66: 2170–21

34 Raymond CL, Profetto-McGrath J. Nurse educators’ criti

calthinking: Reflection and measurement. Nurse Educat

in Practice 2005; 5: 209–217.

35 Facione PA. The California Critical Thinking Skills Test:

Level. Technical Report 1: Experimental Validation and

Validity.Millbrae,CA, USA:California Academic Press,

1990.

36 Sinatra-Wilhelm T. Nursing care plans versus concept m

in the enhancementof criticalthinking skillsin nursing

students enrolled in a baccalaureate nursing program.

tive Nursing 2012; 18: 78–84.

37 WheelerLA, CollinsSKR. The influenceof concept

mapping on criticalthinking in baccalaureate nursing stu-

dents. Journal of Professional Nursing 2003; 19: 339–34

38 RogalSM, Young J. Exploring criticalthinking in critical

care nursing education: A pilot study. Journal of Continu

Education in Nursing 2008; 39: 28–33.

39 Sorensen HAJ,Yankech LR.Precepting in the fastlane:

Improving critical thinking in new graduate nurses. Jour

of Continuing Education in Nursing 2008; 39: 208–216.

40 Facione N, Facione P. The Health Sciences Reasoning T

HSRT.Millbrae,CA, USA:CaliforniaAcademic Press,

2006.

41 Watson G,GlaserEM. Watson–GlaserCriticalThinking

Appraisal: British Manual: Forms A, B and C. San Anton

USA: Psychological Corporation, 1991.

Critical thinking in nursing 9

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

42 Bauwens EE, Gerhard GG. The use of the Watson–Glaser

Critical Thinking Appraisal to predict success in a baccalau-

reate nursing program.TheJournalof Nursing Education

1987; 26: 278–281.

43 Howenstein MA, Bilodeau K, Brogna MJ, Good G. Factors

associated with criticalthinking among nurses.Journalof

Continuing Education in Nursing 1996; 27: 100–103.

44 Chang MJ, Chang Y-J, Kuo S-H, Yang Y-H, Chou F-H.

Relationships between criticalthinking ability and nursing

competence in clinicalnurses.JournalofClinicalNursing

2011; 20: 3224–3232.

45 Profetto-McGrath J.The relationship ofcriticalthinking

skillsand criticalthinking dispositionsof baccalaureate

nursing students. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2003; 43: 569–

577.

46 Shin K, Jung DY, Shin S, Kim MS. Critical thinking dispo-

sitionsand skillsof senior nursing studentsin associate,

baccalaureate,and RN-to-BSN programs.TheJournalof

Nursing Education 2006; 45: 233–237.

47 May BA, Edell V, Butell S, Doughty J, Langford C. Critical

thinking and clinical competence: A study of their relation-

ship in BSN seniors. The Journal of Nursing Education 1999;

38: 100–110.

48 Walsh CM, Seldomridge LA. Measuring criticalthinking:

One step forward, one step back. Nurse Educator 2006; 31:

159–162.

49 Feng R-C, Chen M-J, Chen M-C, Pai Y-C. Critical thinking

competence and disposition of clinical nurses in a medical

center. J Nurs Res 2010; 18: 77–87.

50 Shinnick MA, Woo M, Evangelista LS. Predictors of knowl-

edge gains using simulation in the education of prelicensure

nursing students.JournalofProfessionalNursing 2012;28:

41–47.

51 Paans W, Sermeus W, Nieweg RM, Krijnen WP, van der

Schans CP. Do knowledge, knowledge sources and reason-

ing skillsaffecttheaccuracyof nursingdiagnoses?A

randomised study. BMC Nursing 2012; 11: 11.

52 Paans W, Sermeus W, Nieweg R, van der Schans C. Deter-

minants of the accuracy of nursing diagnoses: Influence of

ready knowledge, knowledge sources, disposition toward

critical thinking, and reasoning skills. Journal of Professional

Nursing 2010; 26: 232–241.

53 Del Bueno DJ. Experience, education, and nurses’ ability to

make clinical judgments. Nursing and Health Care 1990; 11:

290–294.

54 Berkow S, Virkstis K, Stewart J, Aronson S, Donohue M.

Assessing individualfrontline nurse criticalthinking.The

Journal of Nursing Administration 2011; 41: 168–171.

55 Levett-Jones T, Gersbach J, Arthur C, Roche J. Implement-

ing a clinical competency assessment model that promotes

critical reflection and ensures nursing graduates’ readiness

for professionalpractice. Nurse Education in Practice 2011;

11: 64–69.

56 Schubert CR. Effect ofsimulation on nursing knowledge

and criticalthinking in failure to rescue events. Journalof

Continuing Education in Nursing 2012; 43: 467–471.

57 Marchigiano G, Eduljee N, Harvey K. Developing critic

thinking skills from clinicalassignments: A pilot study on

nursingstudents’self-reportedperceptions.Journalof

Nursing Management 2011; 19: 143–152.

58 Suliman WA, HalabiJ. Critical thinking, self-esteem, and

state anxiety ofnursing students.NurseEducation Today

2007; 27: 162–168.

59 Kaddoura MA. Effect of the Essentials of Critical Care

entation (ECCO) program on the development of nurse

criticalthinking skills.Journalof Continuing Education in

Nursing 2010; 41: 424–432.

60 Tesoro MG. Effects of using the Developing Nurses’ Th

ing Modelon nursing students’diagnostic accuracy.The

Journal of Nursing Education 2012; 51: 436–443.

61 Lasater K. Clinicaljudgment development: Using simula-

tion to create an assessment rubric. The JournalofNursing

Education 2007; 46: 496–503.

62 Lasater K, Nielsen A. The influence of concept-based l

ing activities on students’ clinicaljudgment development.

The Journal of Nursing Education 2009; 48: 441–446.

63 Wilgis M, McConnell J. Concept mapping: An education

strategy to improve graduate nurses’ critical thinking

during a hospital orientation program. Journal of Conti

Education in Nursing 2008; 39: 119–126.

64 Sedlak CA.Criticalthinking ofbeginning baccalaureate

nursing students during the first clinical nursing cours

Journal of Nursing Education 1997; 36: 11–18.

65 Forneris SG, Peden-McAlpine C. Evaluation of a reflect

learning intervention to improve critical thinking in no

nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2007; 57: 410–42

66 KhosravaniS, ManoochehriH, Memarian R. Developing

critical thinking skills in nursing students by group dyn

ics.InternetJournalofAdvanced Nursing Practice2005;7:

1–14.

67 Ellermann CR,Kataoka-Yahiro MR,Wong LC.Logic

modelsused to enhance criticalthinking.TheJournalof

Nursing Education 2006; 45: 220–227.

68 Walthew PJ. Conceptions of critical thinking held by nu

educators. The Journal of Nursing Education 2004; 43

411.

69 Chan ZCY. Critical thinking and creativity in nursing: L

ners’ perspectives. Nurse Education Today 2013; 33:

70 Lechasseur K, Lazure G, Guilbert L. Knowledge mobiliz

by a critical thinking process deployed by nursing stud

in practicalcare situations: A qualitative study. Journalof

Advanced Nursing 2011; 67: 1930–1940.

71 Leppa CJ. Assessing student critical thinking through o

discussions. Nurse Educator 2004; 29: 156–160.

72 Raterink G. Critical thinking: Reported enhancers and

riersby nursesin long-term care:Implicationsfor staff

10 E Zuriguel Pérez et al.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Critical Thinking Appraisal to predict success in a baccalau-