Business and Marketing Ethics

VerifiedAdded on 2022/04/20

|19

|11873

|23

AI Summary

Marketing ethics is a subset of applied ethics concerned with the moral principles that guide the operation and regulation of marketing. In numerous instances, marketing ethics (advertising and promotion ethics) and media and public relations ethics overlap.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

ABSTRACT. Marketing ethics is normally marketed

as a sub-specialization of business ethics. In this paper,

marketing ethics serves as an umbrella term for

advertising, PR and sales ethics and as an example of

professionalethics.To structurethe paper,four

approachesare distinguished, with a focus on typical

professional conflicts, codes, roles or climates respec-

tively. Since the moral climate approach is more

inclusive than the other approaches, the last part of

the paper deals mainly with moral climates, within

the above-mentioned marketing sub-professions.

KEY WORDS: advertising ethics, business ethics

approaches, codes of ethics, ethical climate, marketing

ethics, moral climate, professional ethics, public rela-

tions ethics, real estate agent ethics, role morality

Introduction

“‘Ethics’ most often refersto a domain of

inquiry, a discipline, in which matters of right

and wrong, good and evil, virtue and vice, are

systematically examined. ‘Morality’, by contrast,

is most often used to refer not to a discipline

but to patterns of thought and action that are

actually operative in everyday life. In this sense,

morality is what the discipline of ethics is about.

And so business morality is what business ethics

is about” (Goodpaster,1992, p. 111). This

quotation offers a simple and fruitful entrance

into a discipline. Questions about moral accept-

ability in business contexts and others can b

asked (and answered) descriptively or critically. A

descriptive(or empirical,or social science)

question could be whatgiven individuals and

groups themselves actually do accept as right or

wrong. Such a question cannot be answered

without empirical data. A critical (or normative,

or ethics) question would focus on why choices,

consequences, or system states are acceptable (

not). Such questions cannot be answered withou

good reasons, arguments, and criteria. Ideally

asking and answering do not stop before the fact

are clear (enough) and good (enough) reasons ar

found and offered, or before at least good enoug

discussion procedures are followed.1

Marketing ethics

A preliminary portrait of marketing ethics could

simply extend the above quotation. Marketing

ethics examines systematically marketing and

marketing morality, related to 4P-issues such as

unsafe products, deceptive pricing, deceptive

advertising or bribery, discrimination in distrib-

ution (cf. Smith and Quelch, 1993, p. 13). Other

issues are related to exploitation of consume

weakness (see ibid., p. 30) or using PR for pre-

venting critical journalism and public debate. If

business ethics as an academic field is about mo

criticism and self-criticismof businessand

business education, this would include criticism

and self-criticism of marketing as well, as its mos

out-going and aggressive part, with its specific

Business and Marketing

Ethics as Professional Ethics.

Concepts, Approaches

and Typologies Johannes Brinkmann

Journal of Business Ethics41: 159–177, 2002.

© 2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

Johannes Brinkmann, Norwegian School of Management

BI, Oslo, Norway, is originally a sociologist. He has

published several articles in the Journal of Business

Ethics, Teaching Business Ethics, Business Ethics: A

European Review as well as two books about business

ethics (1993, 2001, in Norwegian).

as a sub-specialization of business ethics. In this paper,

marketing ethics serves as an umbrella term for

advertising, PR and sales ethics and as an example of

professionalethics.To structurethe paper,four

approachesare distinguished, with a focus on typical

professional conflicts, codes, roles or climates respec-

tively. Since the moral climate approach is more

inclusive than the other approaches, the last part of

the paper deals mainly with moral climates, within

the above-mentioned marketing sub-professions.

KEY WORDS: advertising ethics, business ethics

approaches, codes of ethics, ethical climate, marketing

ethics, moral climate, professional ethics, public rela-

tions ethics, real estate agent ethics, role morality

Introduction

“‘Ethics’ most often refersto a domain of

inquiry, a discipline, in which matters of right

and wrong, good and evil, virtue and vice, are

systematically examined. ‘Morality’, by contrast,

is most often used to refer not to a discipline

but to patterns of thought and action that are

actually operative in everyday life. In this sense,

morality is what the discipline of ethics is about.

And so business morality is what business ethics

is about” (Goodpaster,1992, p. 111). This

quotation offers a simple and fruitful entrance

into a discipline. Questions about moral accept-

ability in business contexts and others can b

asked (and answered) descriptively or critically. A

descriptive(or empirical,or social science)

question could be whatgiven individuals and

groups themselves actually do accept as right or

wrong. Such a question cannot be answered

without empirical data. A critical (or normative,

or ethics) question would focus on why choices,

consequences, or system states are acceptable (

not). Such questions cannot be answered withou

good reasons, arguments, and criteria. Ideally

asking and answering do not stop before the fact

are clear (enough) and good (enough) reasons ar

found and offered, or before at least good enoug

discussion procedures are followed.1

Marketing ethics

A preliminary portrait of marketing ethics could

simply extend the above quotation. Marketing

ethics examines systematically marketing and

marketing morality, related to 4P-issues such as

unsafe products, deceptive pricing, deceptive

advertising or bribery, discrimination in distrib-

ution (cf. Smith and Quelch, 1993, p. 13). Other

issues are related to exploitation of consume

weakness (see ibid., p. 30) or using PR for pre-

venting critical journalism and public debate. If

business ethics as an academic field is about mo

criticism and self-criticismof businessand

business education, this would include criticism

and self-criticism of marketing as well, as its mos

out-going and aggressive part, with its specific

Business and Marketing

Ethics as Professional Ethics.

Concepts, Approaches

and Typologies Johannes Brinkmann

Journal of Business Ethics41: 159–177, 2002.

© 2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

Johannes Brinkmann, Norwegian School of Management

BI, Oslo, Norway, is originally a sociologist. He has

published several articles in the Journal of Business

Ethics, Teaching Business Ethics, Business Ethics: A

European Review as well as two books about business

ethics (1993, 2001, in Norwegian).

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

tools and tricks and its specific acceptable and

unacceptable choices and consequences.

Marketing ethics markets itself as a research

and teaching specialty on its own. There are ded-

icated textbooks (e.g. Laczniak and Murphy,

1985, 1993; Smith and Quelch, 1993; Chonko,

1995); there are dedicated journal issues (e.g.

Journal of Business Ethics, April 1991#4, January

1999#1,February 2000#3-1issuesor the

International Marketing Review 1995#4, or the

European Journal of Marketing May 1996 special

issue on marketing and social responsibility). In

addition, a few independent articles can be

mentioned,in particular the Tsalikis and

Fritzsche review article published in 1989, the

widely quoted Hunt and Vitell framework papers

of 1986 and 1993, Smith’s introduction chapter

to Smith and Quelch, 1993, or the recent article

of Murphy, 2002).

Professional ethics

Judging from business ethics textbooks, journals

and conferences, marketing ethics is normally

treated as a more or less independent sub-

specialization of business ethics. In this paper,

marketing is dealt with as a profession or, more

precisely,as a common denominatoracross

several sub-professions, i.e. as identifiable com-

petence types or “. . . occupations which have

certain shared characteristics . . . Whether or not

an occupation is more or less professionalized

depends on how thoroughly it manifests these

characteristics.” (Callahan, 1988, p. 26) Some of

such characteristics are basic and indispensable,

e.g. “extensive intellectual training”, “importance

to the organized functioning of society”. Others

are less basic but still useful for typological

distinctions, such as certification, prestige, control

bodies (cf. Appelbaum and Lawton, 1990; Bayles,

1989; Callahan, 1988; Goldman, 1980; Windt

et al., 1989). Another way of defining a profes-

sion could be with reference to the specific stake-

holder-relations and societal functions which are

supposedto be served:clients’ or patients’

welfare, their health, rights, interests etc.

Compared with the traditional, established

professions such as law or medicine, marketing

is almost without tradition, a second-rate or

semi-profession. In such a context, the “exten-

sive intellectual training” criterion is less prob-

lematic (assuming the university-level program

offered and followed are not second rate) tha

the “societal importance” or “basic value refer-

ence” criterion. To most people, health and

justice are “more” basic ideals and values than

keeping market economiesgoing. Looking

skeptically from outside, there is almost a suspi-

cion that marketers’ references to values and

ideals are a marketing trick, an oxymoron, a trial

to instrumentalize ethics, both as a medium

professionalization and as an indicator of claimed

professionalism.

Professional ethics can also be derived, simply,

as a combination of the ethics and profession

concepts referred to above, or developed from a

textbook review (see in general once more

Appelbaum and Lawton, 1990; Bayles, 1989;

Callahan, 1988; Goldman, 1980; Windt et al.,

1989 as well as Flores, 1988; Kultgen, 1988;

Lebacqz, 1985).

Business and marketing ethics as professional et

According to the businessethics literature,

looking at business and marketing ethics as pro-

fessional ethics, at “professions in business and

professions as business” (DeGeorge, 1995, pp

454-471), would be an example of macro or

meso level businessethics,2 in terms of

Goodpaster’s (1992) or Enderle’s (1996) three-

level-distinctions.3 There are a number of

arguments in favor of such a focus on a profes-

sions level as a homogeneous and fruitful level

for theory development, empirical and practical

work:

• a professions approach builds more than any

other approach on a unity of education and

practice, as a mix of studies, work life

experience and training (and often some

continued education, too);

• the professions level is relatively homoge-

neous as a subculture and perhaps more

power-freethan companies(a power-

freedom which could qualify it as a poten-

tial discourse ethics arena);

160 Johannes Brinkmann

unacceptable choices and consequences.

Marketing ethics markets itself as a research

and teaching specialty on its own. There are ded-

icated textbooks (e.g. Laczniak and Murphy,

1985, 1993; Smith and Quelch, 1993; Chonko,

1995); there are dedicated journal issues (e.g.

Journal of Business Ethics, April 1991#4, January

1999#1,February 2000#3-1issuesor the

International Marketing Review 1995#4, or the

European Journal of Marketing May 1996 special

issue on marketing and social responsibility). In

addition, a few independent articles can be

mentioned,in particular the Tsalikis and

Fritzsche review article published in 1989, the

widely quoted Hunt and Vitell framework papers

of 1986 and 1993, Smith’s introduction chapter

to Smith and Quelch, 1993, or the recent article

of Murphy, 2002).

Professional ethics

Judging from business ethics textbooks, journals

and conferences, marketing ethics is normally

treated as a more or less independent sub-

specialization of business ethics. In this paper,

marketing is dealt with as a profession or, more

precisely,as a common denominatoracross

several sub-professions, i.e. as identifiable com-

petence types or “. . . occupations which have

certain shared characteristics . . . Whether or not

an occupation is more or less professionalized

depends on how thoroughly it manifests these

characteristics.” (Callahan, 1988, p. 26) Some of

such characteristics are basic and indispensable,

e.g. “extensive intellectual training”, “importance

to the organized functioning of society”. Others

are less basic but still useful for typological

distinctions, such as certification, prestige, control

bodies (cf. Appelbaum and Lawton, 1990; Bayles,

1989; Callahan, 1988; Goldman, 1980; Windt

et al., 1989). Another way of defining a profes-

sion could be with reference to the specific stake-

holder-relations and societal functions which are

supposedto be served:clients’ or patients’

welfare, their health, rights, interests etc.

Compared with the traditional, established

professions such as law or medicine, marketing

is almost without tradition, a second-rate or

semi-profession. In such a context, the “exten-

sive intellectual training” criterion is less prob-

lematic (assuming the university-level program

offered and followed are not second rate) tha

the “societal importance” or “basic value refer-

ence” criterion. To most people, health and

justice are “more” basic ideals and values than

keeping market economiesgoing. Looking

skeptically from outside, there is almost a suspi-

cion that marketers’ references to values and

ideals are a marketing trick, an oxymoron, a trial

to instrumentalize ethics, both as a medium

professionalization and as an indicator of claimed

professionalism.

Professional ethics can also be derived, simply,

as a combination of the ethics and profession

concepts referred to above, or developed from a

textbook review (see in general once more

Appelbaum and Lawton, 1990; Bayles, 1989;

Callahan, 1988; Goldman, 1980; Windt et al.,

1989 as well as Flores, 1988; Kultgen, 1988;

Lebacqz, 1985).

Business and marketing ethics as professional et

According to the businessethics literature,

looking at business and marketing ethics as pro-

fessional ethics, at “professions in business and

professions as business” (DeGeorge, 1995, pp

454-471), would be an example of macro or

meso level businessethics,2 in terms of

Goodpaster’s (1992) or Enderle’s (1996) three-

level-distinctions.3 There are a number of

arguments in favor of such a focus on a profes-

sions level as a homogeneous and fruitful level

for theory development, empirical and practical

work:

• a professions approach builds more than any

other approach on a unity of education and

practice, as a mix of studies, work life

experience and training (and often some

continued education, too);

• the professions level is relatively homoge-

neous as a subculture and perhaps more

power-freethan companies(a power-

freedom which could qualify it as a poten-

tial discourse ethics arena);

160 Johannes Brinkmann

• often, there exist professional codes which

identify crucial stakeholders,important

moral conflicts and correct handling of such

conflicts;

• professional colleagues represent probably

the most important reference group of pro-

fessionals;

• professionalorganizationshave often a

positive attitude towards organization-wide

studies such as surveys;

• professionalsamplescan be fruitful as

matched samples in cross-cultural compar-

isons.

After such a conceptual introduction, the rest of

this paper offers empirical illustrations from

survey answers from Norwegian marketing prac-

titioners, or more precisely from advertising,

public relations and real-estate practitioners, so

to speak sub-specializations of marketing.4 To a

certain extent, the presentation will be compar-

ative, i.e. raise questions of similarities and dif-

ferences within marketing as a broader field. For

systematic reasons, the presentation is split into

four approaches, focusing on typical professional

conflicts, codes, roles and climates respectively

(assuming that such a four-fold distinction also

is of general interest for professional and business

ethics).

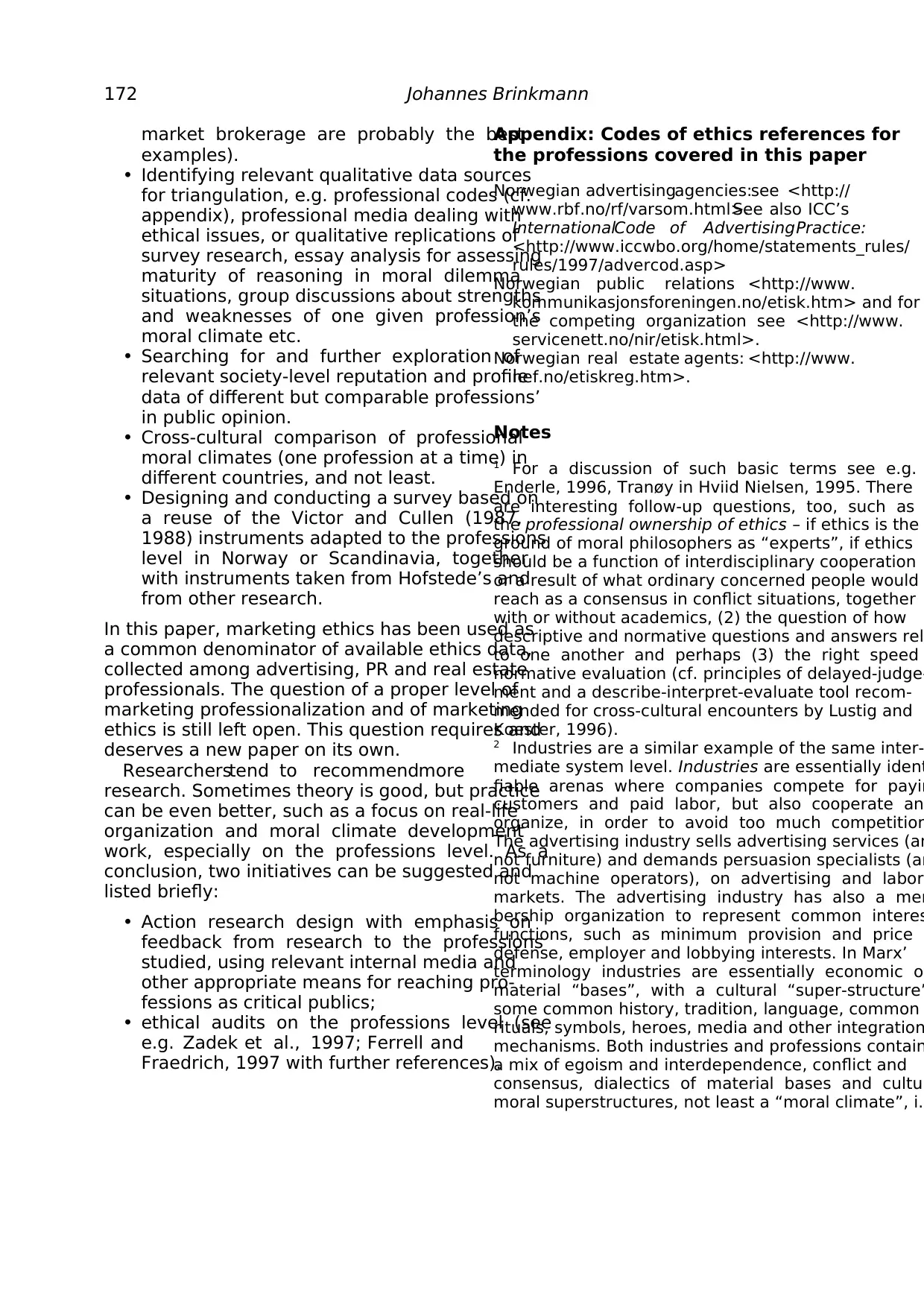

Four approaches to professional ethics

A moral conflict approach

Ethics is probably quite an abstract issue to most

business professionals unless they face a really

urgent and threatening conflict or dilemma. Such

a conflict experience, however, can create an

equally urgent demand for “some” ethics as

conflict settlement help, e.g. in the format of

guidelines or check-list-like rules of procedure.

Consistently, one could understand professional

ethics primarily as a discipline that helps to analyze,

handle and prevent conflict in professional contexts,

by addressing or introducing a moral dimension. In

other words, the relevance of professional ethics

restswith its conflict-consciousness.5 Or: If

professionals do not perceive any moral conflicts

or dilemmas, why bother, and if professionals

demand specific conflict management help, why

not focus on moral conflicts?

To begin with, a few conceptual distinctions

and some ideas can be outlined, including refer-

ences to how such professional moral conflict

could be approached empirically. When studying

a profession, a company, an industry or a work

group, one can look at types, frequency or per-

ceived seriousness of value and interest conflicts

In such cases, one uses a tendency or a property

concept of conflict, where conflict describes a

system or actor relationship state, e.g. a compe-

tition climate or a moral climate.6 One can also

talk of the (one) conflict x, taking place in socio-

cultural context y, during time-span z. In this

case, conflict is studied as a specific time-space-

unit.7 Conflicts-as-units can be seen as manifes-

tations of conflict tendencies, or in the above

terminology, of conflict-as-system-property. In

most professional work situations, there is at leas

some latent conflict. Such latent conflict “man-

ifests” itself from time to time in more or less

open conflict processes or episodes. This aga

“illustrates” that some conflict is natural in every

organization.8

Business life is full of conflict. This is why a

conflict approach to professional ethics is partic-

ularly convincing for business professions. The

market mechanism as such institutionalizes a

conflict of interest between sellers and buyer

employers and employees, among competitors

and other stakeholders. Ideally, markets represen

transparent, fair and productive competition and

in practice hopefully at least some competition.

At first glance, conflicts about values and moralit

issues do not fit into he model. In practice they

are perhaps as ubiquitous as conflicts of interest

and often much harder to handle constructively,

especially if they contain clear dilemmas of the

catch 22-type, i.e. situations with disputable

solutions only. Most business ethics cases, at lea

in textbook presentation format, contain more

or less complex authentic conflicts with at least

one moral issue and without any easy self-eviden

solution.9 After exposure to a raw case descrip-

tion10 students are usually invited to identify and

clarify main issues, parties and stakeholders,

options and wisest solutions. Independently of

size, such dilemmas are normally constructed as

Business and Marketing Ethics as Professional Ethics 161

identify crucial stakeholders,important

moral conflicts and correct handling of such

conflicts;

• professional colleagues represent probably

the most important reference group of pro-

fessionals;

• professionalorganizationshave often a

positive attitude towards organization-wide

studies such as surveys;

• professionalsamplescan be fruitful as

matched samples in cross-cultural compar-

isons.

After such a conceptual introduction, the rest of

this paper offers empirical illustrations from

survey answers from Norwegian marketing prac-

titioners, or more precisely from advertising,

public relations and real-estate practitioners, so

to speak sub-specializations of marketing.4 To a

certain extent, the presentation will be compar-

ative, i.e. raise questions of similarities and dif-

ferences within marketing as a broader field. For

systematic reasons, the presentation is split into

four approaches, focusing on typical professional

conflicts, codes, roles and climates respectively

(assuming that such a four-fold distinction also

is of general interest for professional and business

ethics).

Four approaches to professional ethics

A moral conflict approach

Ethics is probably quite an abstract issue to most

business professionals unless they face a really

urgent and threatening conflict or dilemma. Such

a conflict experience, however, can create an

equally urgent demand for “some” ethics as

conflict settlement help, e.g. in the format of

guidelines or check-list-like rules of procedure.

Consistently, one could understand professional

ethics primarily as a discipline that helps to analyze,

handle and prevent conflict in professional contexts,

by addressing or introducing a moral dimension. In

other words, the relevance of professional ethics

restswith its conflict-consciousness.5 Or: If

professionals do not perceive any moral conflicts

or dilemmas, why bother, and if professionals

demand specific conflict management help, why

not focus on moral conflicts?

To begin with, a few conceptual distinctions

and some ideas can be outlined, including refer-

ences to how such professional moral conflict

could be approached empirically. When studying

a profession, a company, an industry or a work

group, one can look at types, frequency or per-

ceived seriousness of value and interest conflicts

In such cases, one uses a tendency or a property

concept of conflict, where conflict describes a

system or actor relationship state, e.g. a compe-

tition climate or a moral climate.6 One can also

talk of the (one) conflict x, taking place in socio-

cultural context y, during time-span z. In this

case, conflict is studied as a specific time-space-

unit.7 Conflicts-as-units can be seen as manifes-

tations of conflict tendencies, or in the above

terminology, of conflict-as-system-property. In

most professional work situations, there is at leas

some latent conflict. Such latent conflict “man-

ifests” itself from time to time in more or less

open conflict processes or episodes. This aga

“illustrates” that some conflict is natural in every

organization.8

Business life is full of conflict. This is why a

conflict approach to professional ethics is partic-

ularly convincing for business professions. The

market mechanism as such institutionalizes a

conflict of interest between sellers and buyer

employers and employees, among competitors

and other stakeholders. Ideally, markets represen

transparent, fair and productive competition and

in practice hopefully at least some competition.

At first glance, conflicts about values and moralit

issues do not fit into he model. In practice they

are perhaps as ubiquitous as conflicts of interest

and often much harder to handle constructively,

especially if they contain clear dilemmas of the

catch 22-type, i.e. situations with disputable

solutions only. Most business ethics cases, at lea

in textbook presentation format, contain more

or less complex authentic conflicts with at least

one moral issue and without any easy self-eviden

solution.9 After exposure to a raw case descrip-

tion10 students are usually invited to identify and

clarify main issues, parties and stakeholders,

options and wisest solutions. Independently of

size, such dilemmas are normally constructed as

Business and Marketing Ethics as Professional Ethics 161

a hopeless choice between contradictory respon-

sibilities where at least one legitimate stakeholder

will be hurt. The follow-up question is often in

the format of “what would you do if you were

person X, or which conflict party would you side

with, and how would you justify your choice?”

Both in teaching and not least in research,

such abbreviated conflict descriptions are of

interest as a format of asking questions and as

catalysts for discussion.11 In several pilot survey

studies in different Norwegian business profes-

sions perceived moral conflict frequencies and

conflict seriousness were used as a questionnaire

opening. As indicated already, business ethics can

be an abstract issue for most ordinary business

people unless it is experienced in the format of

urgent and threatening conflicts and dilemmas. If

this is so, references to typical conflicts, their fre-

quency and perceived seriousness represent good

warm-up questions for survey research about

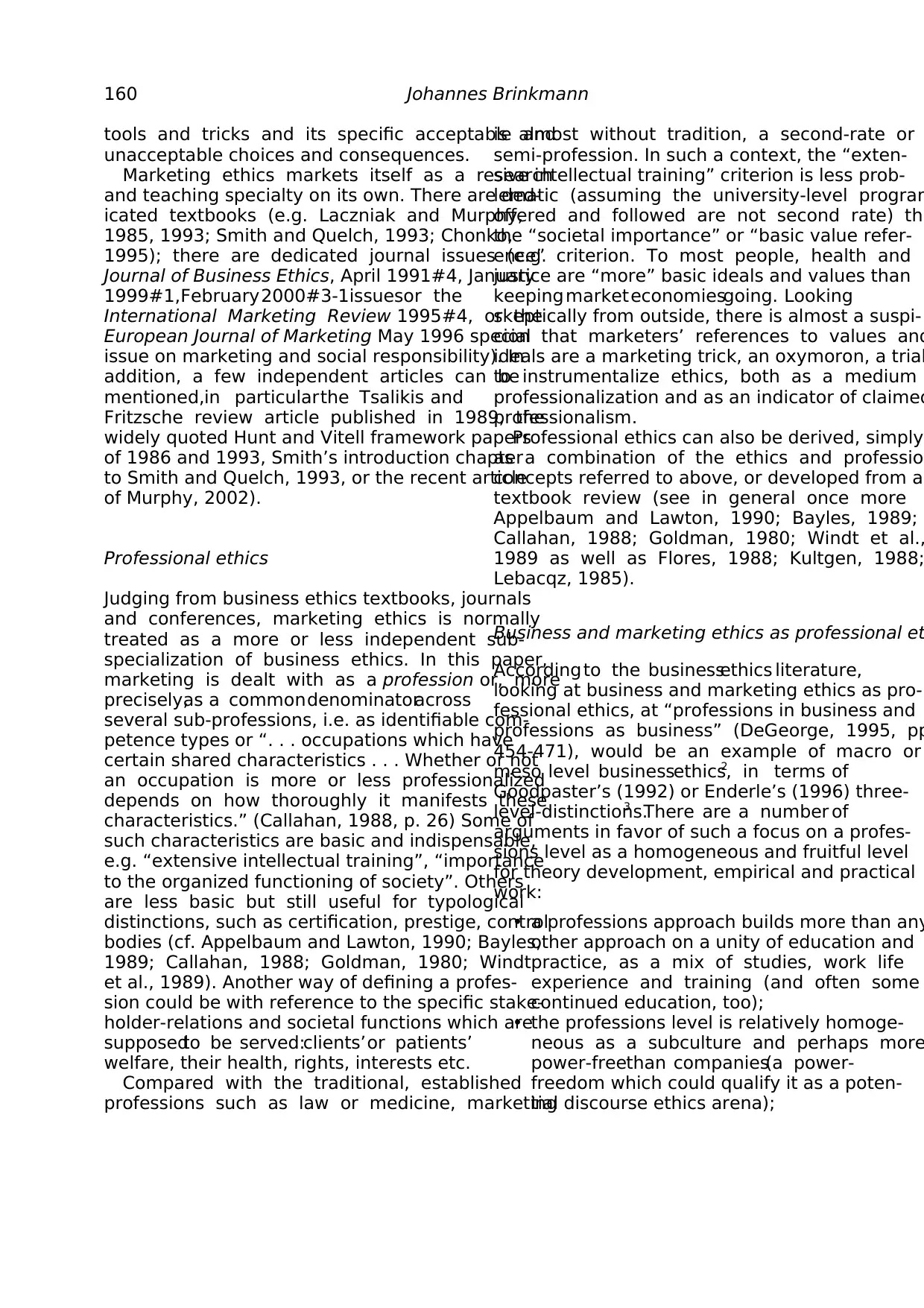

professional ethics. Exhibit 1 lists answer fre-

quencies from the mentioned studies, with areas

of conflict ranked by seriousnessamong

Norwegian real-estate agents, advertising and PR

professionals.

The relative strength of a conflict approach

results from its focus on the importance of acute

professional ethics conflicts as attention-getters,

turning latent contradictions and challenges into

manifest issues which must be dealt with. One

could almost say that a conflict approach tends

towards a deliberate conflict bias and a criticism

of a value consensus bias. Or, in other words, a

weakness could be a focus on conflict events at

the expense of conflict contexts and on serious

acute conflicts even if they represent an excep-

tion rather than normal business life.

A professional code approach

A professional code approach could reason that

professional ethics is a question of developin

implementing an appropriate rule-set– for conflict

handling and for addressing desirable or unde-

sirable behavior. Reading published professional

codes can be a fruitful point of departure for

learning about the real and ideal morality of

given profession.Such codes draw mapsof

expected conflicts, expected or suggested solu-

tions and, perhaps, predictable sanctions. Codes

try to exploit the positive functions of legal

regulation by institutionalizing rules and laws

which are valid for organization members who

accept the rules by signature when joining o

when passing exams. There are often collegiate

bodies that handle complaints and implement th

code, while annual meetings could function as

legislative bodies. On the other hand, negative

functions of legal regulation apply to codes, too.

Forms tend to become important at the expense

of content, external sanctions tend to replace

162 Johannes Brinkmann

EXHIBIT 1

The six most serious types of professional conflict according to the three subsamples

(in parenthesis per cents ranking the type first, second and third)

Advertising professionals PR and Information professionals Real Estate Agents

Quality of work under time Superiors (42) Relations to property buyers (39)

pressure (48)

Client relationships (41) Quality of work under time Relations to property sellers (38)

pressure (40)

Personal/private ethics (37)12 Media (32) Quality of work under time

pressure (38)

Environmental considerations (32)Public debate (31) Incomplete truth (32)

Consumers (34) Critical journalism (30) Caring for weaker parties (27)

Colleagues (23) Colleagues (21) Personal/private ethics (20)

sibilities where at least one legitimate stakeholder

will be hurt. The follow-up question is often in

the format of “what would you do if you were

person X, or which conflict party would you side

with, and how would you justify your choice?”

Both in teaching and not least in research,

such abbreviated conflict descriptions are of

interest as a format of asking questions and as

catalysts for discussion.11 In several pilot survey

studies in different Norwegian business profes-

sions perceived moral conflict frequencies and

conflict seriousness were used as a questionnaire

opening. As indicated already, business ethics can

be an abstract issue for most ordinary business

people unless it is experienced in the format of

urgent and threatening conflicts and dilemmas. If

this is so, references to typical conflicts, their fre-

quency and perceived seriousness represent good

warm-up questions for survey research about

professional ethics. Exhibit 1 lists answer fre-

quencies from the mentioned studies, with areas

of conflict ranked by seriousnessamong

Norwegian real-estate agents, advertising and PR

professionals.

The relative strength of a conflict approach

results from its focus on the importance of acute

professional ethics conflicts as attention-getters,

turning latent contradictions and challenges into

manifest issues which must be dealt with. One

could almost say that a conflict approach tends

towards a deliberate conflict bias and a criticism

of a value consensus bias. Or, in other words, a

weakness could be a focus on conflict events at

the expense of conflict contexts and on serious

acute conflicts even if they represent an excep-

tion rather than normal business life.

A professional code approach

A professional code approach could reason that

professional ethics is a question of developin

implementing an appropriate rule-set– for conflict

handling and for addressing desirable or unde-

sirable behavior. Reading published professional

codes can be a fruitful point of departure for

learning about the real and ideal morality of

given profession.Such codes draw mapsof

expected conflicts, expected or suggested solu-

tions and, perhaps, predictable sanctions. Codes

try to exploit the positive functions of legal

regulation by institutionalizing rules and laws

which are valid for organization members who

accept the rules by signature when joining o

when passing exams. There are often collegiate

bodies that handle complaints and implement th

code, while annual meetings could function as

legislative bodies. On the other hand, negative

functions of legal regulation apply to codes, too.

Forms tend to become important at the expense

of content, external sanctions tend to replace

162 Johannes Brinkmann

EXHIBIT 1

The six most serious types of professional conflict according to the three subsamples

(in parenthesis per cents ranking the type first, second and third)

Advertising professionals PR and Information professionals Real Estate Agents

Quality of work under time Superiors (42) Relations to property buyers (39)

pressure (48)

Client relationships (41) Quality of work under time Relations to property sellers (38)

pressure (40)

Personal/private ethics (37)12 Media (32) Quality of work under time

pressure (38)

Environmental considerations (32)Public debate (31) Incomplete truth (32)

Consumers (34) Critical journalism (30) Caring for weaker parties (27)

Colleagues (23) Colleagues (21) Personal/private ethics (20)

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

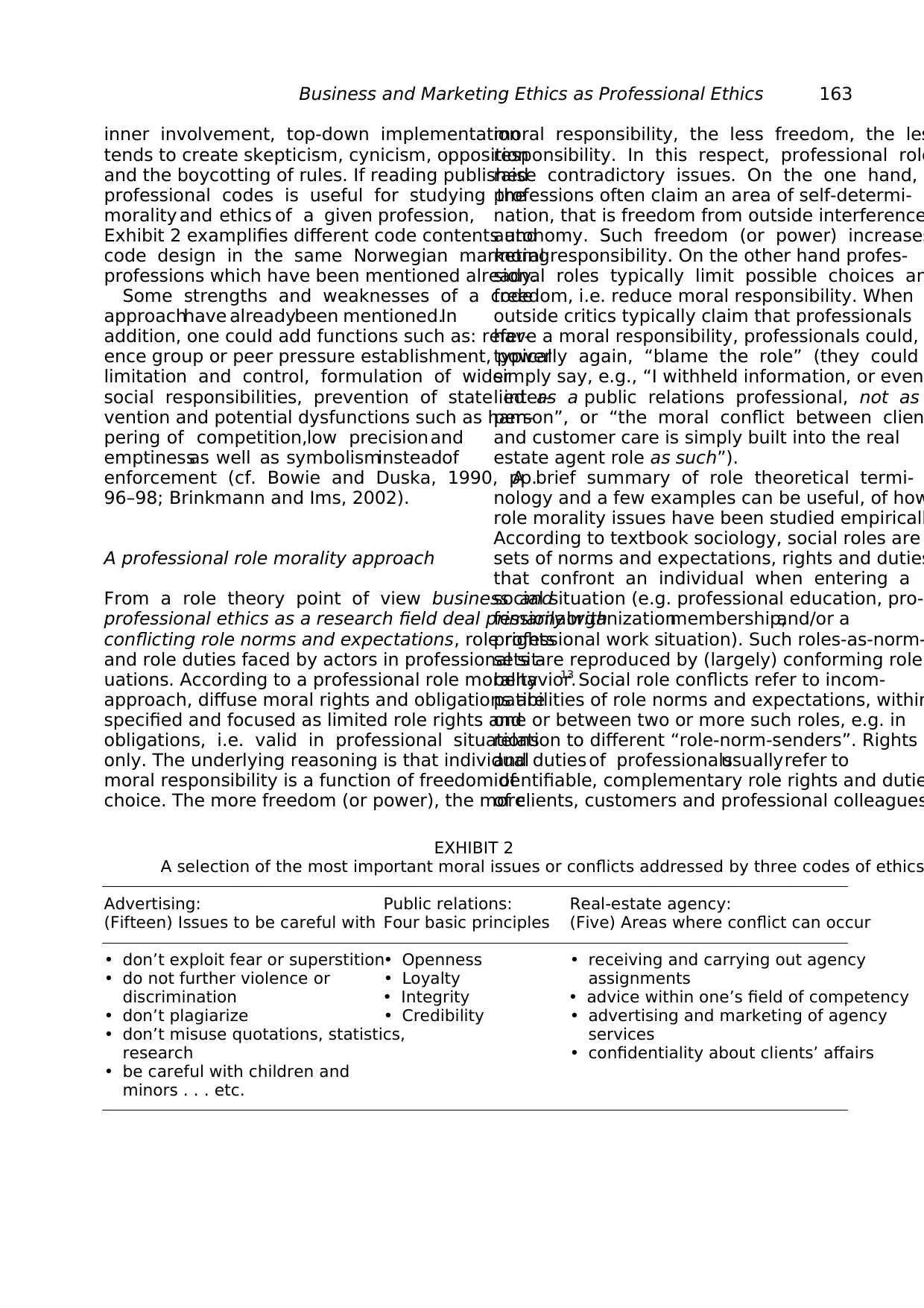

inner involvement, top-down implementation

tends to create skepticism, cynicism, opposition

and the boycotting of rules. If reading published

professional codes is useful for studying the

morality and ethics of a given profession,

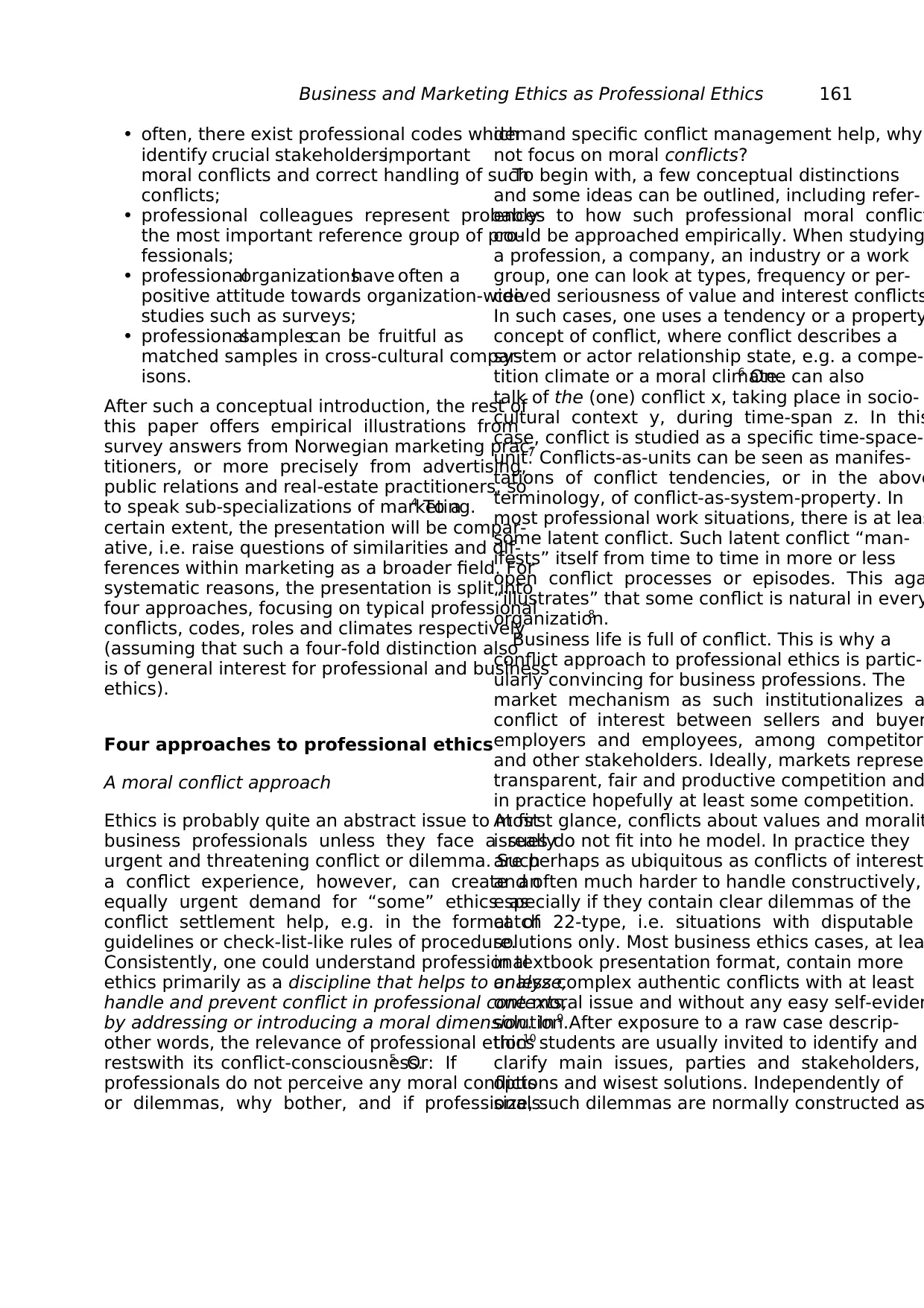

Exhibit 2 examplifies different code contents and

code design in the same Norwegian marketing

professions which have been mentioned already.

Some strengths and weaknesses of a code

approachhave alreadybeen mentioned.In

addition, one could add functions such as: refer-

ence group or peer pressure establishment, power

limitation and control, formulation of wider

social responsibilities, prevention of state inter-

vention and potential dysfunctions such as ham-

pering of competition,low precision and

emptinessas well as symbolisminsteadof

enforcement (cf. Bowie and Duska, 1990, pp.

96–98; Brinkmann and Ims, 2002).

A professional role morality approach

From a role theory point of view business and

professional ethics as a research field deal primarily with

conflicting role norms and expectations, role rights

and role duties faced by actors in professional sit-

uations. According to a professional role morality

approach, diffuse moral rights and obligations are

specified and focused as limited role rights and

obligations, i.e. valid in professional situations

only. The underlying reasoning is that individual

moral responsibility is a function of freedom of

choice. The more freedom (or power), the more

moral responsibility, the less freedom, the les

responsibility. In this respect, professional role

raise contradictory issues. On the one hand,

professions often claim an area of self-determi-

nation, that is freedom from outside interference

autonomy. Such freedom (or power) increases

moral responsibility. On the other hand profes-

sional roles typically limit possible choices an

freedom, i.e. reduce moral responsibility. When

outside critics typically claim that professionals

have a moral responsibility, professionals could,

typically again, “blame the role” (they could

simply say, e.g., “I withheld information, or even

lied as a public relations professional, not as

person”, or “the moral conflict between clien

and customer care is simply built into the real

estate agent role as such”).

A brief summary of role theoretical termi-

nology and a few examples can be useful, of how

role morality issues have been studied empiricall

According to textbook sociology, social roles are

sets of norms and expectations, rights and duties

that confront an individual when entering a

social situation (e.g. professional education, pro-

fessionalorganizationmembership,and/or a

professional work situation). Such roles-as-norm-

sets are reproduced by (largely) conforming role

behavior.13 Social role conflicts refer to incom-

patibilities of role norms and expectations, within

one or between two or more such roles, e.g. in

relation to different “role-norm-senders”. Rights

and duties of professionalsusually refer to

identifiable, complementary role rights and dutie

of clients, customers and professional colleagues

Business and Marketing Ethics as Professional Ethics 163

EXHIBIT 2

A selection of the most important moral issues or conflicts addressed by three codes of ethics

Advertising: Public relations: Real-estate agency:

(Fifteen) Issues to be careful with Four basic principles (Five) Areas where conflict can occur

• don’t exploit fear or superstition• Openness • receiving and carrying out agency

• do not further violence or • Loyalty assignments

discrimination • Integrity • advice within one’s field of competency

• don’t plagiarize • Credibility • advertising and marketing of agency

• don’t misuse quotations, statistics, services

research • confidentiality about clients’ affairs

• be careful with children and

minors . . . etc.

tends to create skepticism, cynicism, opposition

and the boycotting of rules. If reading published

professional codes is useful for studying the

morality and ethics of a given profession,

Exhibit 2 examplifies different code contents and

code design in the same Norwegian marketing

professions which have been mentioned already.

Some strengths and weaknesses of a code

approachhave alreadybeen mentioned.In

addition, one could add functions such as: refer-

ence group or peer pressure establishment, power

limitation and control, formulation of wider

social responsibilities, prevention of state inter-

vention and potential dysfunctions such as ham-

pering of competition,low precision and

emptinessas well as symbolisminsteadof

enforcement (cf. Bowie and Duska, 1990, pp.

96–98; Brinkmann and Ims, 2002).

A professional role morality approach

From a role theory point of view business and

professional ethics as a research field deal primarily with

conflicting role norms and expectations, role rights

and role duties faced by actors in professional sit-

uations. According to a professional role morality

approach, diffuse moral rights and obligations are

specified and focused as limited role rights and

obligations, i.e. valid in professional situations

only. The underlying reasoning is that individual

moral responsibility is a function of freedom of

choice. The more freedom (or power), the more

moral responsibility, the less freedom, the les

responsibility. In this respect, professional role

raise contradictory issues. On the one hand,

professions often claim an area of self-determi-

nation, that is freedom from outside interference

autonomy. Such freedom (or power) increases

moral responsibility. On the other hand profes-

sional roles typically limit possible choices an

freedom, i.e. reduce moral responsibility. When

outside critics typically claim that professionals

have a moral responsibility, professionals could,

typically again, “blame the role” (they could

simply say, e.g., “I withheld information, or even

lied as a public relations professional, not as

person”, or “the moral conflict between clien

and customer care is simply built into the real

estate agent role as such”).

A brief summary of role theoretical termi-

nology and a few examples can be useful, of how

role morality issues have been studied empiricall

According to textbook sociology, social roles are

sets of norms and expectations, rights and duties

that confront an individual when entering a

social situation (e.g. professional education, pro-

fessionalorganizationmembership,and/or a

professional work situation). Such roles-as-norm-

sets are reproduced by (largely) conforming role

behavior.13 Social role conflicts refer to incom-

patibilities of role norms and expectations, within

one or between two or more such roles, e.g. in

relation to different “role-norm-senders”. Rights

and duties of professionalsusually refer to

identifiable, complementary role rights and dutie

of clients, customers and professional colleagues

Business and Marketing Ethics as Professional Ethics 163

EXHIBIT 2

A selection of the most important moral issues or conflicts addressed by three codes of ethics

Advertising: Public relations: Real-estate agency:

(Fifteen) Issues to be careful with Four basic principles (Five) Areas where conflict can occur

• don’t exploit fear or superstition• Openness • receiving and carrying out agency

• do not further violence or • Loyalty assignments

discrimination • Integrity • advice within one’s field of competency

• don’t plagiarize • Credibility • advertising and marketing of agency

• don’t misuse quotations, statistics, services

research • confidentiality about clients’ affairs

• be careful with children and

minors . . . etc.

Moral role conflict scenarios represent popular

simplifications of complex situations, not least

with their connotation of replaceable rather than

unique individuals. Furthermore, from a role

theory point of view single decisions and the

single norms related to them are less interesting

than recurring situations where norms are clus-

tered as social roles and where professionals are

supposed to conform to roles as a mix of norms

rather than with single norms. As a consequence,

a professional who enters situations which typi-

cally trigger norms and expectations appears

rather as a reactive, conflict-handling role player

than as a subject with free choices.

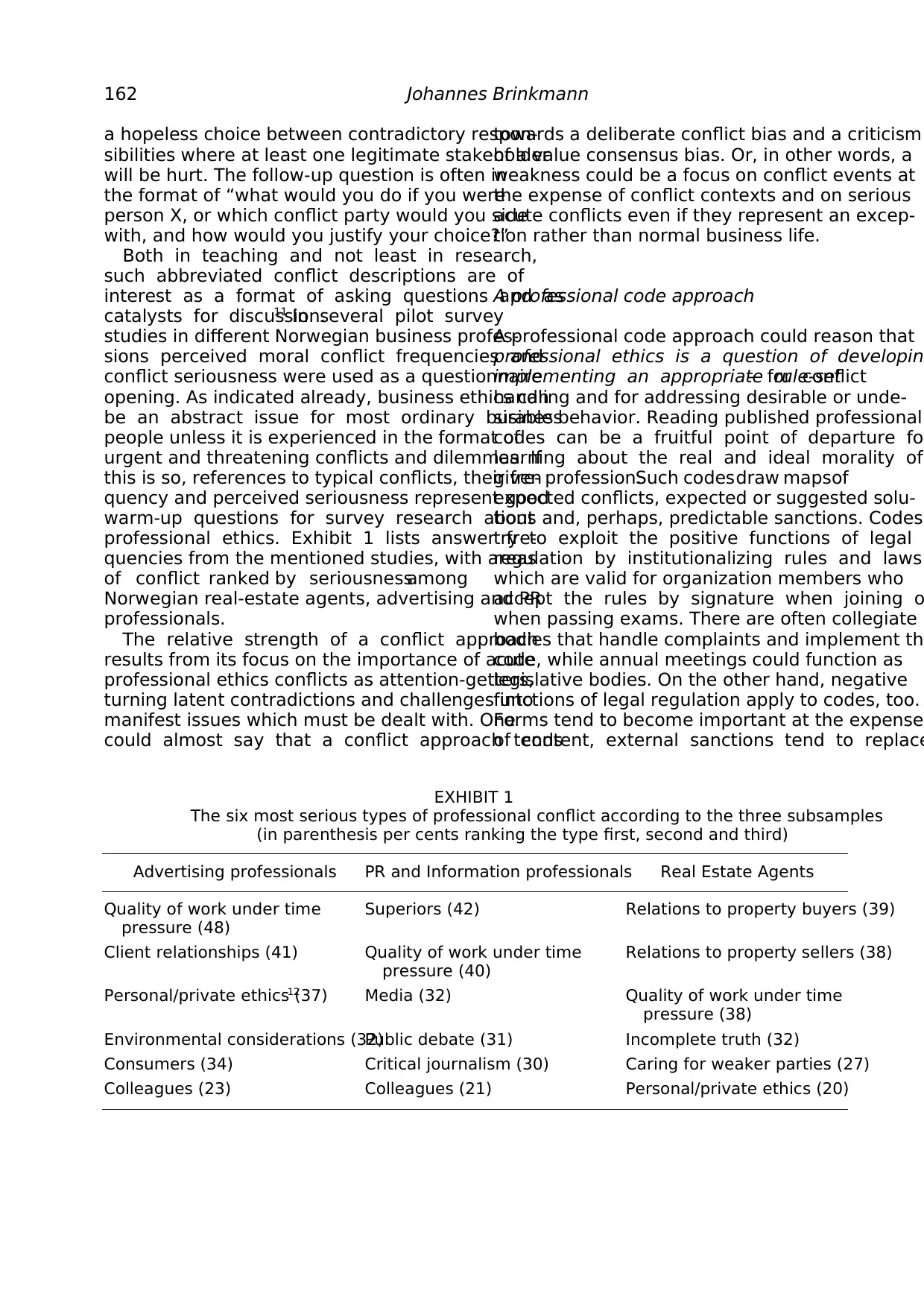

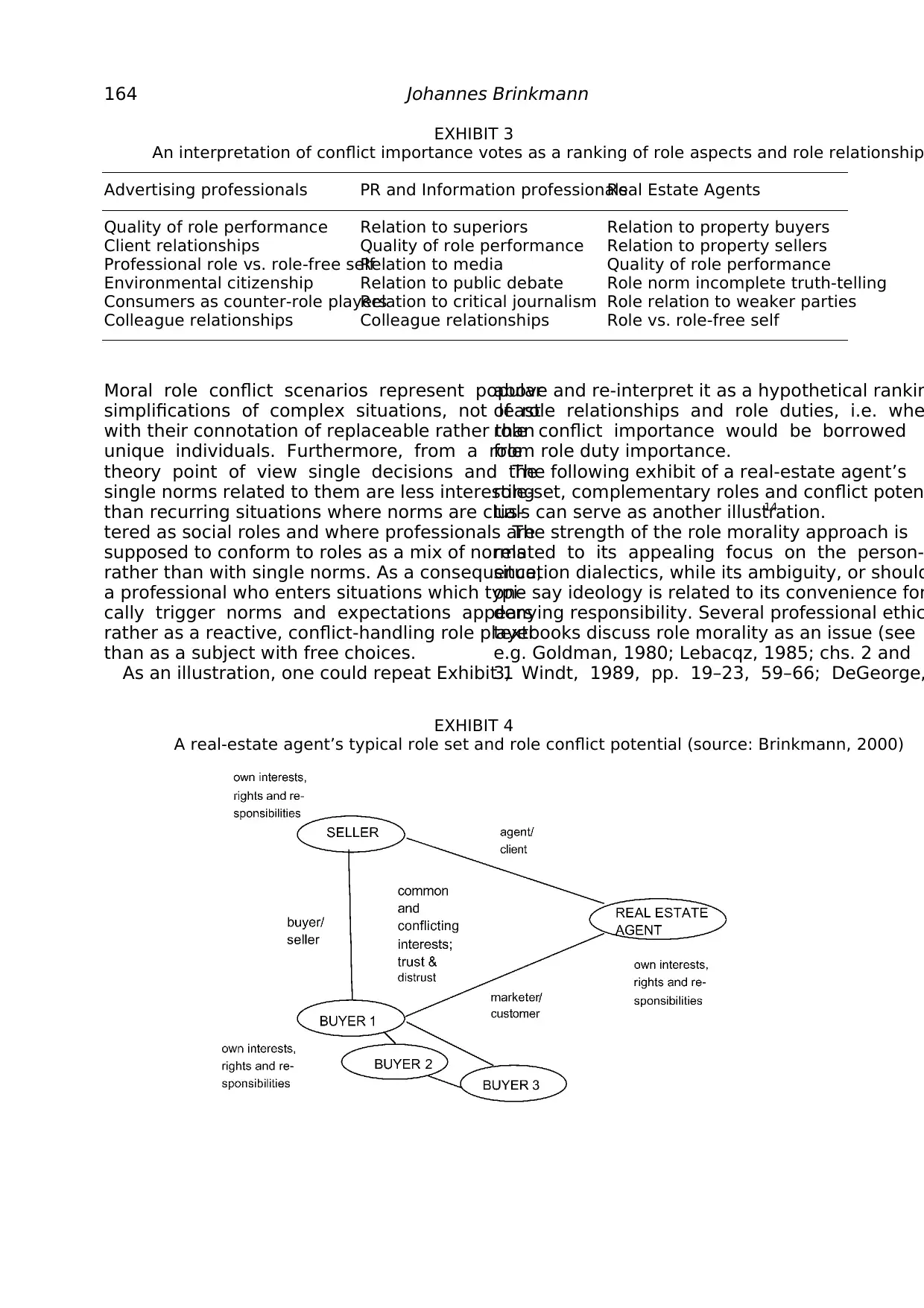

As an illustration, one could repeat Exhibit 1

above and re-interpret it as a hypothetical rankin

of role relationships and role duties, i.e. whe

role conflict importance would be borrowed

from role duty importance.

The following exhibit of a real-estate agent’s

role-set, complementary roles and conflict poten

tials can serve as another illustration.14

The strength of the role morality approach is

related to its appealing focus on the person-

situation dialectics, while its ambiguity, or should

one say ideology is related to its convenience for

denying responsibility. Several professional ethic

textbooks discuss role morality as an issue (see

e.g. Goldman, 1980; Lebacqz, 1985; chs. 2 and

3, Windt, 1989, pp. 19–23, 59–66; DeGeorge,

164 Johannes Brinkmann

EXHIBIT 3

An interpretation of conflict importance votes as a ranking of role aspects and role relationship

Advertising professionals PR and Information professionalsReal Estate Agents

Quality of role performance Relation to superiors Relation to property buyers

Client relationships Quality of role performance Relation to property sellers

Professional role vs. role-free selfRelation to media Quality of role performance

Environmental citizenship Relation to public debate Role norm incomplete truth-telling

Consumers as counter-role playersRelation to critical journalism Role relation to weaker parties

Colleague relationships Colleague relationships Role vs. role-free self

EXHIBIT 4

A real-estate agent’s typical role set and role conflict potential (source: Brinkmann, 2000)

simplifications of complex situations, not least

with their connotation of replaceable rather than

unique individuals. Furthermore, from a role

theory point of view single decisions and the

single norms related to them are less interesting

than recurring situations where norms are clus-

tered as social roles and where professionals are

supposed to conform to roles as a mix of norms

rather than with single norms. As a consequence,

a professional who enters situations which typi-

cally trigger norms and expectations appears

rather as a reactive, conflict-handling role player

than as a subject with free choices.

As an illustration, one could repeat Exhibit 1

above and re-interpret it as a hypothetical rankin

of role relationships and role duties, i.e. whe

role conflict importance would be borrowed

from role duty importance.

The following exhibit of a real-estate agent’s

role-set, complementary roles and conflict poten

tials can serve as another illustration.14

The strength of the role morality approach is

related to its appealing focus on the person-

situation dialectics, while its ambiguity, or should

one say ideology is related to its convenience for

denying responsibility. Several professional ethic

textbooks discuss role morality as an issue (see

e.g. Goldman, 1980; Lebacqz, 1985; chs. 2 and

3, Windt, 1989, pp. 19–23, 59–66; DeGeorge,

164 Johannes Brinkmann

EXHIBIT 3

An interpretation of conflict importance votes as a ranking of role aspects and role relationship

Advertising professionals PR and Information professionalsReal Estate Agents

Quality of role performance Relation to superiors Relation to property buyers

Client relationships Quality of role performance Relation to property sellers

Professional role vs. role-free selfRelation to media Quality of role performance

Environmental citizenship Relation to public debate Role norm incomplete truth-telling

Consumers as counter-role playersRelation to critical journalism Role relation to weaker parties

Colleague relationships Colleague relationships Role vs. role-free self

EXHIBIT 4

A real-estate agent’s typical role set and role conflict potential (source: Brinkmann, 2000)

1995, pp. 120–122), or with one quotation

instead of many: “Special roles . . . seem clearly

to create special moral rights and duties. But the

question then arises as to the source and scope

of these rights and duties. And these questions

involve asking whether and, if so, how the

constraints of ordinary morality apply to the

professionals in their professional roles. (. . . The

question has been raised, JB) whether it is

morally permissible for those in business roles to

radically separate their occupational roles from

their roles as ordinary moral agents – that is,

agents bound by the strictures . . . that normally

bind persons . . .” (Callahan, 1988, pp. 49–50).

Among more in-depth philosophical discus-

sions of role morality15 Applbaum’s monograph

(1999) deservesspecial attention,with its

thorough examination of the ambiguities of role

morality,referringto executioner,insurance

doctor, defense lawyer roles and others. The last

few pages of his book represent an excellent

summary of issues: “. . . Though roles ordinarily

cannot permit what is forbidden,they can

require what is permitted. Professional roles are

powerful obligators. Nothing I have said here

should be taken to argue for the weakening of

the moral commitments that tie professionals to

their legitimate and just professional role oblig-

ations. But neither consent nor some version of

the fair-play principle can bind an actor to an

illegitimate or unjust role. Montaigne is wrong:

lawyers and financiers, politicians and public

servants are responsible for the vice and stupidity

of their trades, and should refuse to practice them

in vicious and stupid ways . . .” (1999, p. 259)16

A moral climate approach

Without understanding the parts there is no

understanding of the whole and vice versa.

Instead of departing from professional conflict

or professional codes or professional roles one can

depart from the climate or culture which they

are elements of and which is made up of their

interdependence and interaction. The last one

of four approaches to professional ethics could be

called a moral climate approach.17 In the present

paper, moral climate is suggested as a wide

umbrella term for a profession’s normative socia

ization environment. Moral climate as a social-

ization medium consists essentially of role norms

which are learned by future members (“antici-

patory” socialization) and by new members, from

normative and comparative reference groups.

Climate shapes people, but people shape climate

too. Moral climates are produced and reproduced

by their members and their practices.18 As an

umbrella term, moral climate repeats classic soc

science references such as “collective conscience

(E. Durkheim), “ideology” in a neutral and

negative sense (K. Marx), or “value rationality”

(M. Weber). If there is any ambiguity of the

concept “moral climate” this is due to different

connotations of “moral” and “morality”19 (with

the question of formal vs. informal norms being

of special interest. In the business ethics litera-

ture, moral or ethical climate has been suggested

as a theoretical, empirically measurable concept

(see e.g. Wimbush and Shepard, 1994; Wimbush

et al., 1997; Vidaver-Cohen, 1998; or Fritzsche,

2000 with newer references). Derived from a

work climate definition, moral climate has been

defined as “stable, psychologically meaningful

shared perceptions employees hold concerning

ethical procedures and policies existing in their

organizations” (cf. Wimbush and Shepard, 1994,

p. 636; cf. also with lengthy elaboration Victor

and Cullen, 1987, pp. 52–57 or 1988, pp.

101–104). Ideally, the moral climate in a given

profession would be reconstructed from a com-

bination of several different data sources and

types – such as history, media, observation o

professional board meetings or annual gathering

professional codes of ethics, group interviews.20

Such qualitative data could then be combined

with representative survey data, collected with

standard instruments, such as the ECQ referred

to below.

The strongest argument in favor of a mora

climate approach is probably its holism.21 Its

weakness is related to its dependency on ind

vidual internalization and to its possible value

consensus bias.

The introductory remarks of this section sug-

gested four approaches as alternative points

departurerather than as mutuallyexclusive

choices. Since the approaches are different, they

Business and Marketing Ethics as Professional Ethics 165

instead of many: “Special roles . . . seem clearly

to create special moral rights and duties. But the

question then arises as to the source and scope

of these rights and duties. And these questions

involve asking whether and, if so, how the

constraints of ordinary morality apply to the

professionals in their professional roles. (. . . The

question has been raised, JB) whether it is

morally permissible for those in business roles to

radically separate their occupational roles from

their roles as ordinary moral agents – that is,

agents bound by the strictures . . . that normally

bind persons . . .” (Callahan, 1988, pp. 49–50).

Among more in-depth philosophical discus-

sions of role morality15 Applbaum’s monograph

(1999) deservesspecial attention,with its

thorough examination of the ambiguities of role

morality,referringto executioner,insurance

doctor, defense lawyer roles and others. The last

few pages of his book represent an excellent

summary of issues: “. . . Though roles ordinarily

cannot permit what is forbidden,they can

require what is permitted. Professional roles are

powerful obligators. Nothing I have said here

should be taken to argue for the weakening of

the moral commitments that tie professionals to

their legitimate and just professional role oblig-

ations. But neither consent nor some version of

the fair-play principle can bind an actor to an

illegitimate or unjust role. Montaigne is wrong:

lawyers and financiers, politicians and public

servants are responsible for the vice and stupidity

of their trades, and should refuse to practice them

in vicious and stupid ways . . .” (1999, p. 259)16

A moral climate approach

Without understanding the parts there is no

understanding of the whole and vice versa.

Instead of departing from professional conflict

or professional codes or professional roles one can

depart from the climate or culture which they

are elements of and which is made up of their

interdependence and interaction. The last one

of four approaches to professional ethics could be

called a moral climate approach.17 In the present

paper, moral climate is suggested as a wide

umbrella term for a profession’s normative socia

ization environment. Moral climate as a social-

ization medium consists essentially of role norms

which are learned by future members (“antici-

patory” socialization) and by new members, from

normative and comparative reference groups.

Climate shapes people, but people shape climate

too. Moral climates are produced and reproduced

by their members and their practices.18 As an

umbrella term, moral climate repeats classic soc

science references such as “collective conscience

(E. Durkheim), “ideology” in a neutral and

negative sense (K. Marx), or “value rationality”

(M. Weber). If there is any ambiguity of the

concept “moral climate” this is due to different

connotations of “moral” and “morality”19 (with

the question of formal vs. informal norms being

of special interest. In the business ethics litera-

ture, moral or ethical climate has been suggested

as a theoretical, empirically measurable concept

(see e.g. Wimbush and Shepard, 1994; Wimbush

et al., 1997; Vidaver-Cohen, 1998; or Fritzsche,

2000 with newer references). Derived from a

work climate definition, moral climate has been

defined as “stable, psychologically meaningful

shared perceptions employees hold concerning

ethical procedures and policies existing in their

organizations” (cf. Wimbush and Shepard, 1994,

p. 636; cf. also with lengthy elaboration Victor

and Cullen, 1987, pp. 52–57 or 1988, pp.

101–104). Ideally, the moral climate in a given

profession would be reconstructed from a com-

bination of several different data sources and

types – such as history, media, observation o

professional board meetings or annual gathering

professional codes of ethics, group interviews.20

Such qualitative data could then be combined

with representative survey data, collected with

standard instruments, such as the ECQ referred

to below.

The strongest argument in favor of a mora

climate approach is probably its holism.21 Its

weakness is related to its dependency on ind

vidual internalization and to its possible value

consensus bias.

The introductory remarks of this section sug-

gested four approaches as alternative points

departurerather than as mutuallyexclusive

choices. Since the approaches are different, they

Business and Marketing Ethics as Professional Ethics 165

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

can be complementary and combined. (Moral

climates can prevent and handle moral conflict

and can be learned by newcomers together with

rules and roles. Climates are more or less depen-

dent on ethical codes. Role players produce and

reproduce moral climates. Many moral conflicts

can be understoodas role conflicts, codes

describe role rights and duties, etc.) A moral

climate approach is probably better at including

the other approaches. Therefore, the rest of the

paper deals mainly with empiricalor pre-

empiricalpresentationsof moral climates–

within three marketing sub-professions (without

negating, however, the potential use of the other

approaches, alone or combined).

Typologies and comparisons

Typologies and comparisons relate to one another

as hens to eggs. Typologies are primarily useful

for comparisons, and comparisons require criteria

to compare by.22 In this section of the paper and

the following one some possible comparison

criteria are presented, that is several typologies

using and inviting a comparative approach.

Typologies can be useful for describing and

understanding professional ethics in general and

their professional moral climate in particular, i.e.

as a variety of different possible climate types, in

this case on the professions level. Typologies

(“ideal typologies”, in Max Weber’s terminology)

are in essence second order concepts, made up

by a combination of criteria, dimensions or

concepts. Such typologies can also and not least

function as bridge builders between theory and

empirical research, either before data collection

as a first guide towards instrument development,

or after data collection as useful ingredient of da

summary and data interpretation work.

A first example could be to compare profes-

sions and their moral climate by moral maturity.

Ranking individualsby moral maturityand

assessing moral development is problematic but

popular, both in everyday life and in ethics

research. R. E. Reidenbach and D. P. Robin have

suggestedtransferringthe classic Kohlberg

classification scheme of individual moral maturity

levels to the corporation or organization level.

Their distinction could be applied to professional

organizations as well, with its assumed con-

tinuum of amoral, legalistic, responsive, emergin

ethical and developedethical climates(see

Reidenbach and Robin, 1991, with a model on

p. 274). As in the well-known Kohlberg-scheme

with its three level-types and six stage-types, the

type names matter less than the maturity dimen

sion as such, as an invitation to benchmarking.

A way of following up such a line of thinking

could be so-called ethical auditing, i.e. an eval-

uation of given organizations,in terms of

predefined moral responsibility criteria (cf. e.g

Ferrell and Fraedrich, 1997, pp. 118–126,

181–187 with further references, or Zadek et al.,

1997; Bak, 1996; van Luijk, 2000; Andriof

and McIntosh, 2001, chs. 14–16 or e.g.

http://www.accountability.org.uk/).

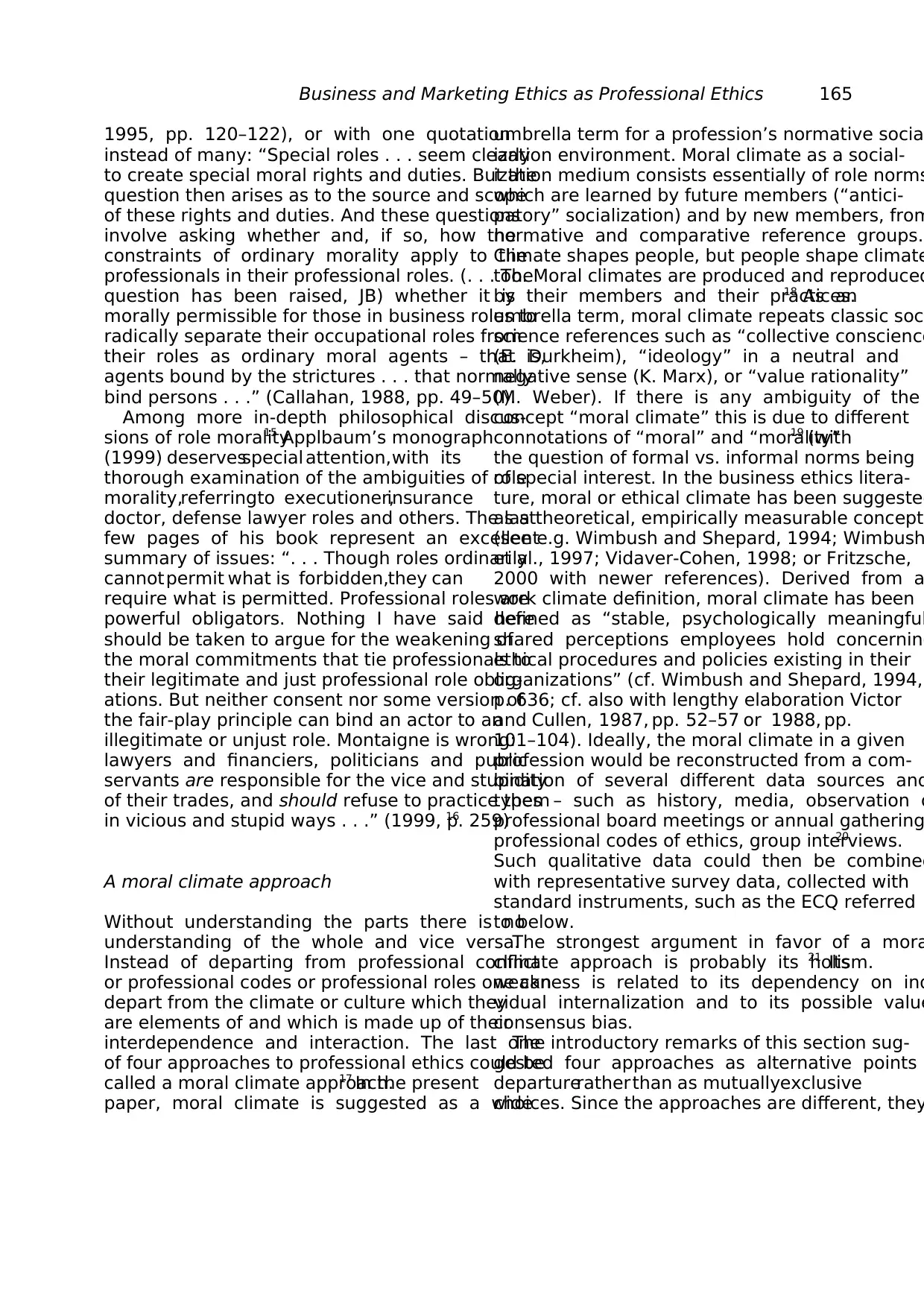

In another example, three ethics types and

three referencegroup levels are combined,

resulting in nine theoretical “ethical climate

types” (see Exhibit 5, suggested by Victor an

Cullen, 1988, p. 104). Such a typology (with

certain similarities to the mentioned Reidenbach

and Robin typology example) is also a good

example for possible bridge building to empir-

ical research.23

166 Johannes Brinkmann

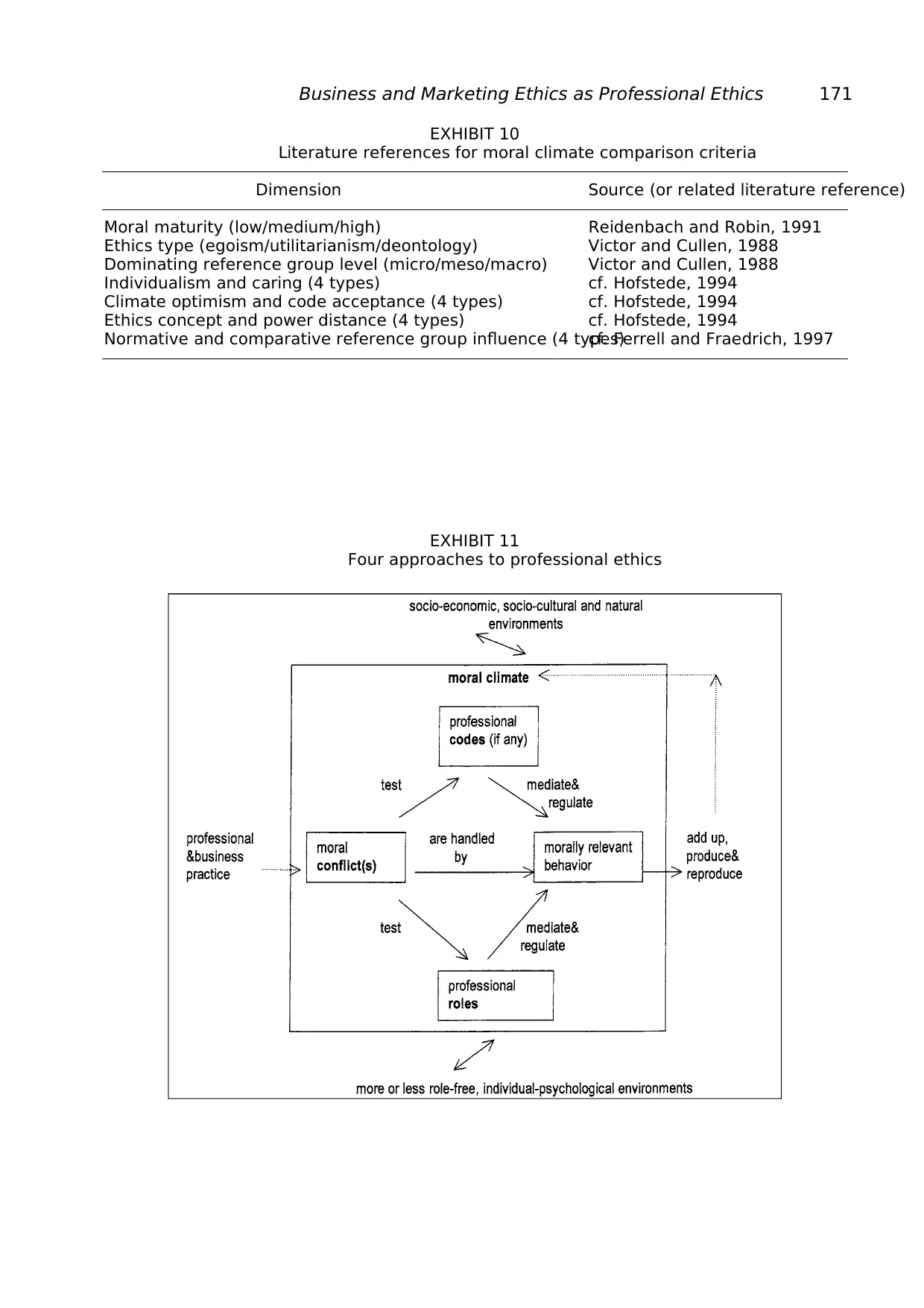

EXHIBIT 5

Nine moral climate types by guiding principle (slightly modified from Victor and Cullen, 1988)

A Macro B Meso (local) C Micro

3 Deontology (principle) Laws and professional Organization rules and Personal morality

codes procedures

2 Utilitarianism (benevolence)Social responsibility Team interest Friendship

1 Egoism Efficiency Organization profit Self-interest

climates can prevent and handle moral conflict

and can be learned by newcomers together with

rules and roles. Climates are more or less depen-

dent on ethical codes. Role players produce and

reproduce moral climates. Many moral conflicts

can be understoodas role conflicts, codes

describe role rights and duties, etc.) A moral

climate approach is probably better at including

the other approaches. Therefore, the rest of the

paper deals mainly with empiricalor pre-

empiricalpresentationsof moral climates–

within three marketing sub-professions (without

negating, however, the potential use of the other

approaches, alone or combined).

Typologies and comparisons

Typologies and comparisons relate to one another

as hens to eggs. Typologies are primarily useful

for comparisons, and comparisons require criteria

to compare by.22 In this section of the paper and

the following one some possible comparison

criteria are presented, that is several typologies

using and inviting a comparative approach.

Typologies can be useful for describing and

understanding professional ethics in general and

their professional moral climate in particular, i.e.

as a variety of different possible climate types, in

this case on the professions level. Typologies

(“ideal typologies”, in Max Weber’s terminology)

are in essence second order concepts, made up

by a combination of criteria, dimensions or

concepts. Such typologies can also and not least

function as bridge builders between theory and

empirical research, either before data collection

as a first guide towards instrument development,

or after data collection as useful ingredient of da

summary and data interpretation work.

A first example could be to compare profes-

sions and their moral climate by moral maturity.

Ranking individualsby moral maturityand

assessing moral development is problematic but

popular, both in everyday life and in ethics

research. R. E. Reidenbach and D. P. Robin have

suggestedtransferringthe classic Kohlberg

classification scheme of individual moral maturity

levels to the corporation or organization level.

Their distinction could be applied to professional

organizations as well, with its assumed con-

tinuum of amoral, legalistic, responsive, emergin

ethical and developedethical climates(see

Reidenbach and Robin, 1991, with a model on

p. 274). As in the well-known Kohlberg-scheme

with its three level-types and six stage-types, the

type names matter less than the maturity dimen

sion as such, as an invitation to benchmarking.

A way of following up such a line of thinking

could be so-called ethical auditing, i.e. an eval-

uation of given organizations,in terms of

predefined moral responsibility criteria (cf. e.g

Ferrell and Fraedrich, 1997, pp. 118–126,

181–187 with further references, or Zadek et al.,

1997; Bak, 1996; van Luijk, 2000; Andriof

and McIntosh, 2001, chs. 14–16 or e.g.

http://www.accountability.org.uk/).

In another example, three ethics types and

three referencegroup levels are combined,

resulting in nine theoretical “ethical climate

types” (see Exhibit 5, suggested by Victor an

Cullen, 1988, p. 104). Such a typology (with

certain similarities to the mentioned Reidenbach

and Robin typology example) is also a good

example for possible bridge building to empir-

ical research.23

166 Johannes Brinkmann

EXHIBIT 5

Nine moral climate types by guiding principle (slightly modified from Victor and Cullen, 1988)

A Macro B Meso (local) C Micro

3 Deontology (principle) Laws and professional Organization rules and Personal morality

codes procedures

2 Utilitarianism (benevolence)Social responsibility Team interest Friendship

1 Egoism Efficiency Organization profit Self-interest

Further (empirical) illustrations

The concepts, distinctions and other points pre-

sented so far can be illustrated by a number of

typologies, using easily accessible data. The data

were originally collected in several Norwegian

industries and professions, between 1993 and

1996, for covering other research questions.24

The following figures are presented in a similar

two-dimensional format as G. Hofstede’s (1994)

and F. Trompenaars’ (1993) “maps” of organiza-

tion culture types in different countries. For

instance, according to Hofstede, Norway’s and

Scandinavia’s typical organization climate would

have a medium score on individualism and a

medium low score on power distance, or, in

another diagram, low masculinity and low to

very low uncertaintyavoidancescores(see

Hofstede’s tables and maps, 1994, pp. 54, 123).

Average U.S. climates would score low on cen-

tralism and medium on formalism (Trompenaars,

1993, p. 161). Hofstede-like coordinate maps

have become famous and popular because of

their intuitive appeal, but should rather be read

as fruitful hypotheses worthy of further research.

They should not be read as confirmed hypotheses.

The following maps are based on pilot data (or

pilot reuse of data) and can have a similar

function.25

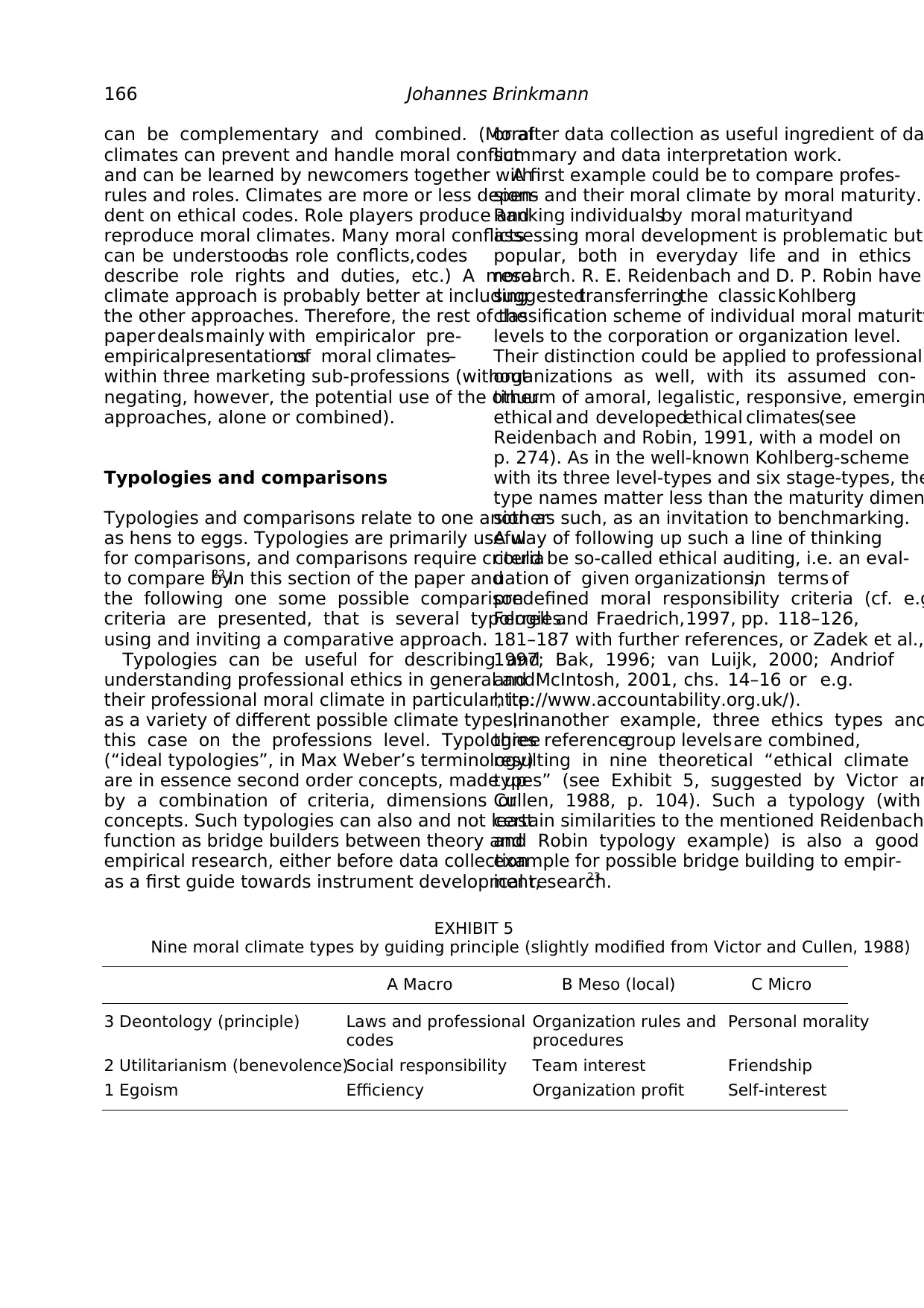

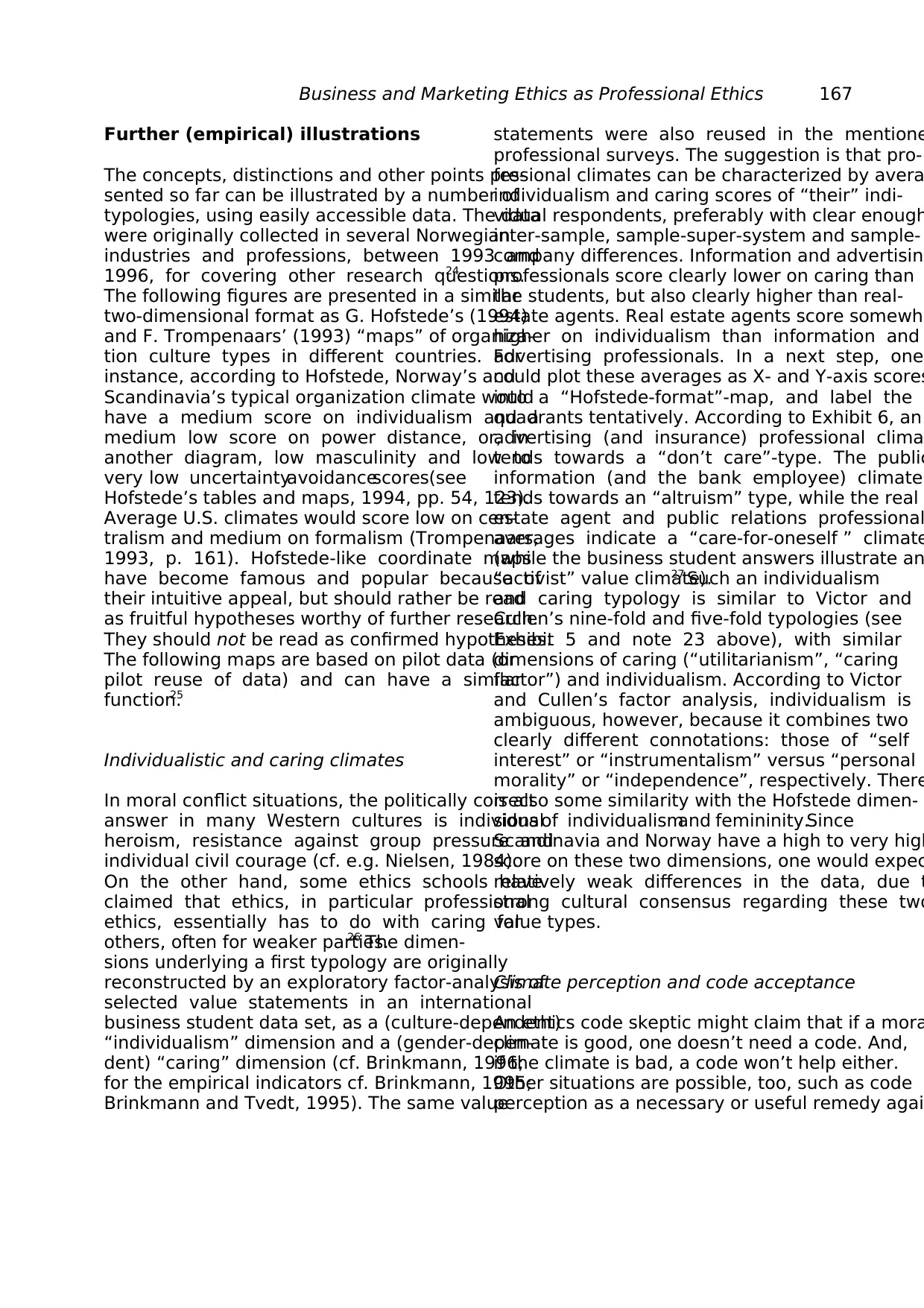

Individualistic and caring climates

In moral conflict situations, the politically correct

answer in many Western cultures is individual

heroism, resistance against group pressure and

individual civil courage (cf. e.g. Nielsen, 1984).

On the other hand, some ethics schools have

claimed that ethics, in particular professional

ethics, essentially has to do with caring for

others, often for weaker parties.26 The dimen-

sions underlying a first typology are originally

reconstructed by an exploratory factor-analysis of

selected value statements in an international

business student data set, as a (culture-dependent)

“individualism” dimension and a (gender-depen-

dent) “caring” dimension (cf. Brinkmann, 1996;

for the empirical indicators cf. Brinkmann, 1995;

Brinkmann and Tvedt, 1995). The same value

statements were also reused in the mentione

professional surveys. The suggestion is that pro-

fessional climates can be characterized by avera

individualism and caring scores of “their” indi-

vidual respondents, preferably with clear enough

inter-sample, sample-super-system and sample-

company differences. Information and advertising

professionals score clearly lower on caring than

the students, but also clearly higher than real-

estate agents. Real estate agents score somewha

higher on individualism than information and

advertising professionals. In a next step, one

could plot these averages as X- and Y-axis scores

into a “Hofstede-format”-map, and label the

quadrants tentatively. According to Exhibit 6, an

advertising (and insurance) professional clima

tends towards a “don’t care”-type. The public

information (and the bank employee) climate

tends towards an “altruism” type, while the real

estate agent and public relations professional

averages indicate a “care-for-oneself ” climate

(while the business student answers illustrate an

“activist” value climate).27 Such an individualism

and caring typology is similar to Victor and

Cullen’s nine-fold and five-fold typologies (see

Exhibit 5 and note 23 above), with similar

dimensions of caring (“utilitarianism”, “caring

factor”) and individualism. According to Victor

and Cullen’s factor analysis, individualism is

ambiguous, however, because it combines two

clearly different connotations: those of “self

interest” or “instrumentalism” versus “personal

morality” or “independence”, respectively. There

is also some similarity with the Hofstede dimen-

sions of individualismand femininity.Since

Scandinavia and Norway have a high to very high

score on these two dimensions, one would expec

relatively weak differences in the data, due t

strong cultural consensus regarding these two

value types.

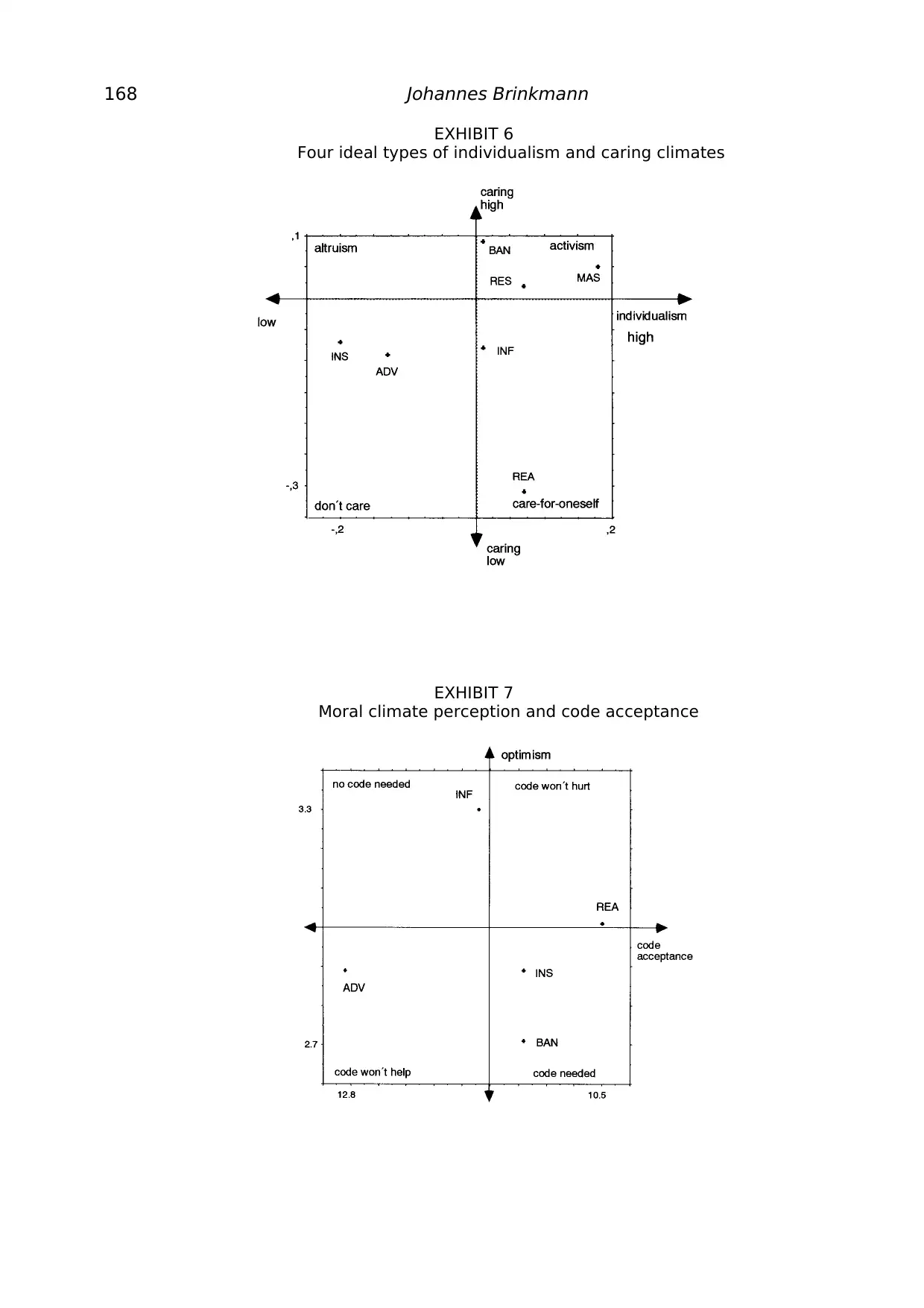

Climate perception and code acceptance

An ethics code skeptic might claim that if a mora

climate is good, one doesn’t need a code. And,

if the climate is bad, a code won’t help either.

Other situations are possible, too, such as code

perception as a necessary or useful remedy agai

Business and Marketing Ethics as Professional Ethics 167

The concepts, distinctions and other points pre-

sented so far can be illustrated by a number of

typologies, using easily accessible data. The data

were originally collected in several Norwegian

industries and professions, between 1993 and

1996, for covering other research questions.24

The following figures are presented in a similar

two-dimensional format as G. Hofstede’s (1994)

and F. Trompenaars’ (1993) “maps” of organiza-

tion culture types in different countries. For

instance, according to Hofstede, Norway’s and

Scandinavia’s typical organization climate would

have a medium score on individualism and a

medium low score on power distance, or, in

another diagram, low masculinity and low to

very low uncertaintyavoidancescores(see

Hofstede’s tables and maps, 1994, pp. 54, 123).

Average U.S. climates would score low on cen-

tralism and medium on formalism (Trompenaars,

1993, p. 161). Hofstede-like coordinate maps

have become famous and popular because of

their intuitive appeal, but should rather be read

as fruitful hypotheses worthy of further research.

They should not be read as confirmed hypotheses.

The following maps are based on pilot data (or

pilot reuse of data) and can have a similar

function.25

Individualistic and caring climates

In moral conflict situations, the politically correct

answer in many Western cultures is individual

heroism, resistance against group pressure and

individual civil courage (cf. e.g. Nielsen, 1984).

On the other hand, some ethics schools have

claimed that ethics, in particular professional

ethics, essentially has to do with caring for

others, often for weaker parties.26 The dimen-

sions underlying a first typology are originally

reconstructed by an exploratory factor-analysis of

selected value statements in an international

business student data set, as a (culture-dependent)

“individualism” dimension and a (gender-depen-

dent) “caring” dimension (cf. Brinkmann, 1996;

for the empirical indicators cf. Brinkmann, 1995;

Brinkmann and Tvedt, 1995). The same value

statements were also reused in the mentione

professional surveys. The suggestion is that pro-

fessional climates can be characterized by avera

individualism and caring scores of “their” indi-

vidual respondents, preferably with clear enough

inter-sample, sample-super-system and sample-

company differences. Information and advertising

professionals score clearly lower on caring than

the students, but also clearly higher than real-

estate agents. Real estate agents score somewha

higher on individualism than information and

advertising professionals. In a next step, one

could plot these averages as X- and Y-axis scores

into a “Hofstede-format”-map, and label the

quadrants tentatively. According to Exhibit 6, an

advertising (and insurance) professional clima

tends towards a “don’t care”-type. The public

information (and the bank employee) climate

tends towards an “altruism” type, while the real

estate agent and public relations professional

averages indicate a “care-for-oneself ” climate

(while the business student answers illustrate an

“activist” value climate).27 Such an individualism

and caring typology is similar to Victor and

Cullen’s nine-fold and five-fold typologies (see

Exhibit 5 and note 23 above), with similar

dimensions of caring (“utilitarianism”, “caring

factor”) and individualism. According to Victor

and Cullen’s factor analysis, individualism is

ambiguous, however, because it combines two

clearly different connotations: those of “self

interest” or “instrumentalism” versus “personal

morality” or “independence”, respectively. There

is also some similarity with the Hofstede dimen-

sions of individualismand femininity.Since

Scandinavia and Norway have a high to very high

score on these two dimensions, one would expec

relatively weak differences in the data, due t

strong cultural consensus regarding these two

value types.

Climate perception and code acceptance

An ethics code skeptic might claim that if a mora

climate is good, one doesn’t need a code. And,

if the climate is bad, a code won’t help either.

Other situations are possible, too, such as code

perception as a necessary or useful remedy agai

Business and Marketing Ethics as Professional Ethics 167

168 Johannes Brinkmann

EXHIBIT 7

Moral climate perception and code acceptance

EXHIBIT 6

Four ideal types of individualism and caring climates

EXHIBIT 7

Moral climate perception and code acceptance

EXHIBIT 6

Four ideal types of individualism and caring climates

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Business and Marketing Ethics as Professional Ethics 169

EXHIBIT 8

Ethical individualism and power distance

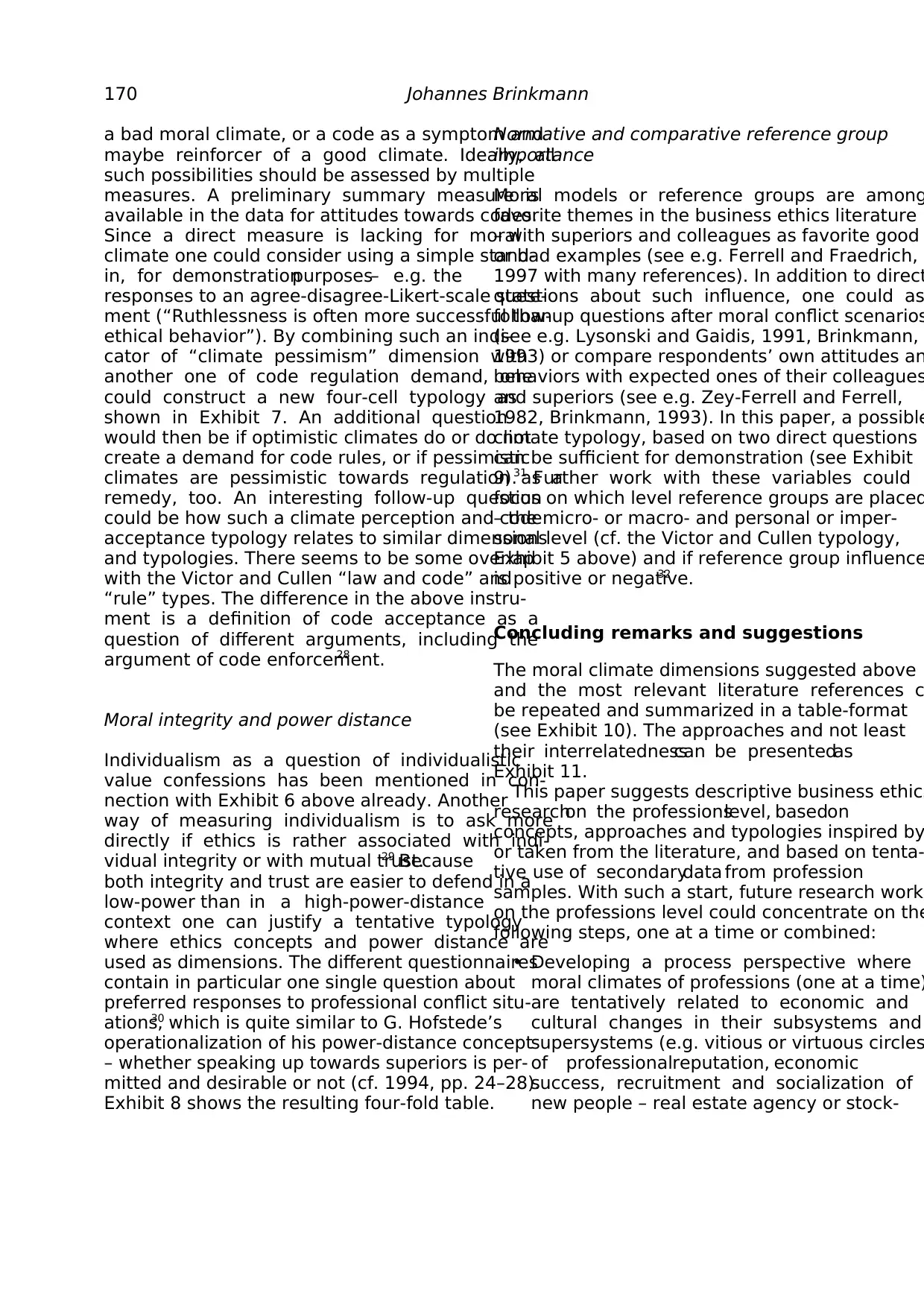

EXHIBIT 9

Normative and comparative reference group importance

EXHIBIT 8

Ethical individualism and power distance

EXHIBIT 9

Normative and comparative reference group importance

170 Johannes Brinkmann

a bad moral climate, or a code as a symptom and

maybe reinforcer of a good climate. Ideally, all

such possibilities should be assessed by multiple

measures. A preliminary summary measure is

available in the data for attitudes towards codes.

Since a direct measure is lacking for moral

climate one could consider using a simple stand-

in, for demonstrationpurposes– e.g. the

responses to an agree-disagree-Likert-scale state-

ment (“Ruthlessness is often more successful than

ethical behavior”). By combining such an indi-

cator of “climate pessimism” dimension with

another one of code regulation demand, one

could construct a new four-cell typology as

shown in Exhibit 7. An additional question

would then be if optimistic climates do or do not

create a demand for code rules, or if pessimistic

climates are pessimistic towards regulation as a

remedy, too. An interesting follow-up question

could be how such a climate perception and code

acceptance typology relates to similar dimensions

and typologies. There seems to be some overlap

with the Victor and Cullen “law and code” and

“rule” types. The difference in the above instru-

ment is a definition of code acceptance as a

question of different arguments, including the

argument of code enforcement.28

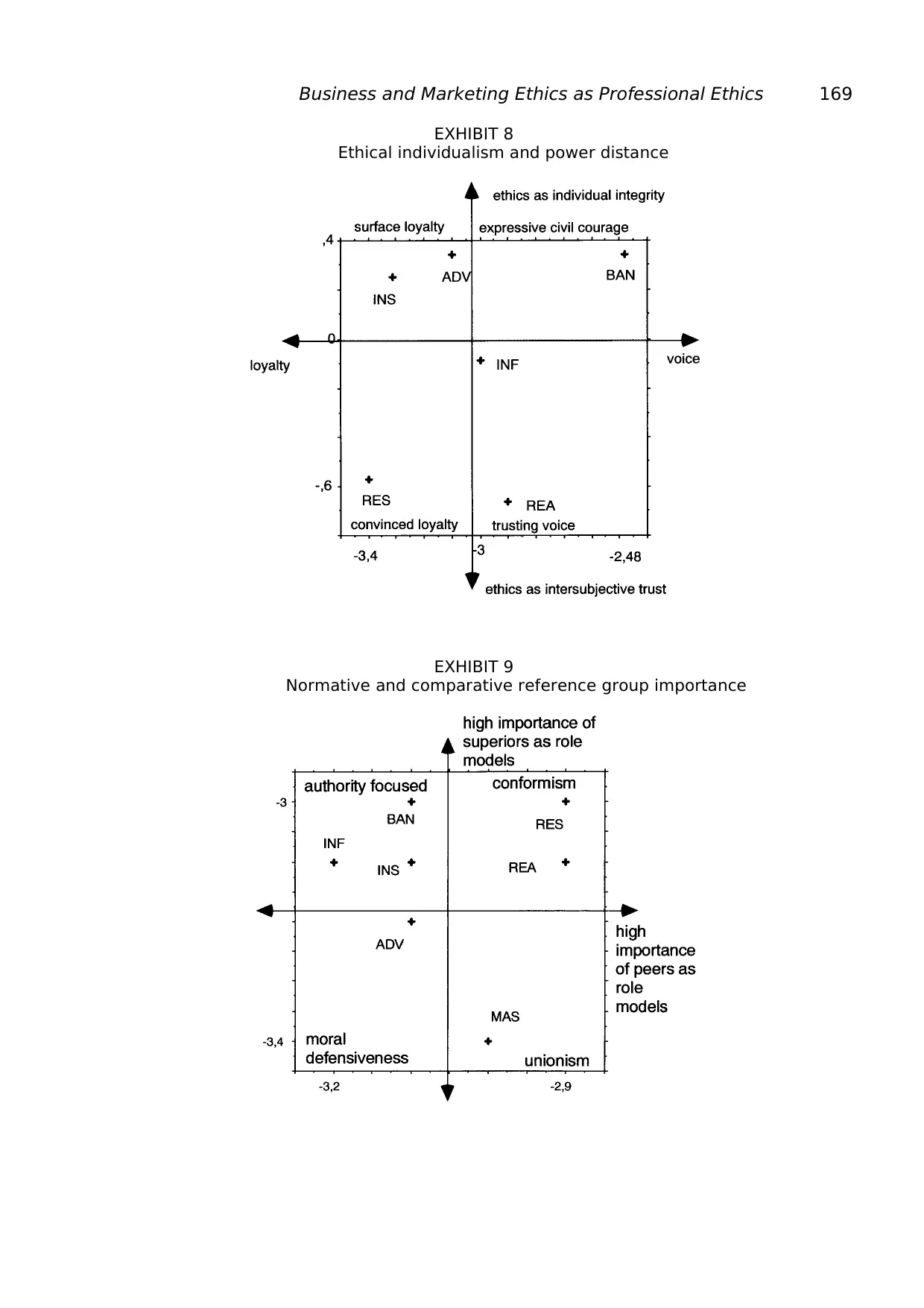

Moral integrity and power distance

Individualism as a question of individualistic

value confessions has been mentioned in con-

nection with Exhibit 6 above already. Another

way of measuring individualism is to ask more

directly if ethics is rather associated with indi-

vidual integrity or with mutual trust.29 Because

both integrity and trust are easier to defend in a

low-power than in a high-power-distance

context one can justify a tentative typology

where ethics concepts and power distance are

used as dimensions. The different questionnaires

contain in particular one single question about

preferred responses to professional conflict situ-

ations,30 which is quite similar to G. Hofstede’s

operationalization of his power-distance concept