MGMT20143: Analyzing Charles Tyrwhitt's Business Model Canvas

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/09

|35

|16843

|152

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study deconstructs Charles Tyrwhitt's business model using the Business Model Canvas framework, analyzing key elements that contributed to its impact on Australian fashion retailing. The analysis relies on publicly available information, highlighting Charles Tyrwhitt's reliance on direct mail order techniques, online order capture, and challenges related to inventory management and store expansion. The report suggests a shift towards a job-to-be-done customer segmentation model, a better understanding of disruptive innovation, and a strategic focus on successful markets. The study concludes with recommendations for reshaping the business model to avoid disruption and achieve future growth, including a halt to UK store growth and a focus on applying lessons learned in successful markets like Germany and Australia to new regions like Scandinavia.

City, University of London Institutional Repository

Citation: Aversa, P., Haefliger, S., Rossi, A. & Baden-Fuller, C. (2015). From Business

Model to Business Modelling: Modularity and Manipulation. Business Models and Modelling,

33, pp. 151-185. doi: 10.1108/S0742-332220150000033022

This is the draft version of the paper.

This version of the publication may differ from the final published

version.

Permanent repository link: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/13976/

Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S0742-332220150000033022

Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research

outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience.

Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright

holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and

linked to.

City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ publications@city.ac.uk

City Research Online

Citation: Aversa, P., Haefliger, S., Rossi, A. & Baden-Fuller, C. (2015). From Business

Model to Business Modelling: Modularity and Manipulation. Business Models and Modelling,

33, pp. 151-185. doi: 10.1108/S0742-332220150000033022

This is the draft version of the paper.

This version of the publication may differ from the final published

version.

Permanent repository link: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/13976/

Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S0742-332220150000033022

Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research

outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience.

Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright

holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and

linked to.

City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ publications@city.ac.uk

City Research Online

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 1

1

From Business Model to Business Modeling:

Modularity and Manipulation

Paolo Aversa

Cass Business School, City University London

Stefan Haefliger

Cass Business School, City University London

Alessandro Rossi

DEM, Università degli Studi di Trento

Charles Baden-Fuller

Cass Business School, City University London

Abstract

The concept of modularity has gained considerable traction in technology studies as a way to

conceive, describe and innovate complex systems, such as product design or organizational

structures. In the recent literature, technological modularity has often been intertwined with

business model innovation, and scholarship has started investigating how modularity in

technology affects changes in business models, both at the cognitive and activity system

levels. Yet we still lack a theoretical definition of what modularity is in the business model

domain. Business model innovation also encompasses different possibilities of modeling

businesses, which are not clearly understood nor classified. We ask when, how and if

modularity theory can be extended to business models in order to enable effective and

efficient modeling. We distinguish theoretically between modularity for technology and for

business models, and investigate the key processes of modularization and manipulation. We

introduce the basic operations of business modeling via modular operators adapted from the

technological modularity domain, using iconic examples to develop an analogical reasoning

between modularity in technology and in business models. Finally, we discuss opportunities

for using modularity theory to foster the understanding of business models and modeling, and

develop a challenging research agenda for future investigations.

Keywords: business model, modeling, cognition, modularity, manipulation, decomposability

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 1

1

From Business Model to Business Modeling:

Modularity and Manipulation

Paolo Aversa

Cass Business School, City University London

Stefan Haefliger

Cass Business School, City University London

Alessandro Rossi

DEM, Università degli Studi di Trento

Charles Baden-Fuller

Cass Business School, City University London

Abstract

The concept of modularity has gained considerable traction in technology studies as a way to

conceive, describe and innovate complex systems, such as product design or organizational

structures. In the recent literature, technological modularity has often been intertwined with

business model innovation, and scholarship has started investigating how modularity in

technology affects changes in business models, both at the cognitive and activity system

levels. Yet we still lack a theoretical definition of what modularity is in the business model

domain. Business model innovation also encompasses different possibilities of modeling

businesses, which are not clearly understood nor classified. We ask when, how and if

modularity theory can be extended to business models in order to enable effective and

efficient modeling. We distinguish theoretically between modularity for technology and for

business models, and investigate the key processes of modularization and manipulation. We

introduce the basic operations of business modeling via modular operators adapted from the

technological modularity domain, using iconic examples to develop an analogical reasoning

between modularity in technology and in business models. Finally, we discuss opportunities

for using modularity theory to foster the understanding of business models and modeling, and

develop a challenging research agenda for future investigations.

Keywords: business model, modeling, cognition, modularity, manipulation, decomposability

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 2

2

From Business Model to Business Modeling:

Modularity and Manipulation

Introduction

A business model represents a business enterprise’s essential value creation and capture

activities in reduced and abstract form (Teece, 2010). Such models are, first of all, cognitive

devices that mediate between managerial thinking and engagement in economic activities

(Baden-Fuller & Morgan, 2010; Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, 2002; Martins, Rindova &

Greenbaum, 2015), and so represent complex economic environments in simplified forms,

facilitating reasoning and communication to third parties. While economists work with

sophisticated mathematical representations, simpler tools - such as lists or maps - are often

employed as models in the management field (for a taxonomy see French, Maule &

Papamichail, 2009; or see Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010 for a business model 'canvas'). The

business model, specifically, has recently gained widespread interest and application among

scholars and managers as a helpful tool for both thinking about and creating systems of value

creation, delivery and capture (for a review see Zott, Amit & Massa, 2011).

Business models can be represented in many forms, and employing a particular style of

representation can affect the associated thinking processes and thus the model’s functionality

(Martins et al., 2015). However, several recent scholarly representations of business models -

despite being grounded in different theoretical premises - have in common the fact that they

are conceived as combinations of sub-categories populated by consistent elements (see

among others the classifications by Baden-Fuller & Mangematin, 2013; Demil & Lecocq,

2010; Massa & Tucci, 2013; Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010; Zott & Amit, 2010). Also, the

popularity of tools such as the ‘business model canvas’ (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010)

among practitioners seems to suggest that even managers are at ease with representing

business models as simplified systems of interconnected elements. Thus we start from the

situation where a model for business is considered relevant and useful (Morgan, 2012), and

cognitive efforts to represent “business models as models” (Baden-Fuller & Morgan, 2010)

are important in order for the role of business models as “manipulable instruments” (i.e.,

instruments that can be voluntarily shaped and changed to gather insight) to be enacted.

These in turn can be helpful in assisting scholarly and managerial reflection both on what a

firm does (or could do) to create and capture value, and on how it can be modeled and

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 2

2

From Business Model to Business Modeling:

Modularity and Manipulation

Introduction

A business model represents a business enterprise’s essential value creation and capture

activities in reduced and abstract form (Teece, 2010). Such models are, first of all, cognitive

devices that mediate between managerial thinking and engagement in economic activities

(Baden-Fuller & Morgan, 2010; Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, 2002; Martins, Rindova &

Greenbaum, 2015), and so represent complex economic environments in simplified forms,

facilitating reasoning and communication to third parties. While economists work with

sophisticated mathematical representations, simpler tools - such as lists or maps - are often

employed as models in the management field (for a taxonomy see French, Maule &

Papamichail, 2009; or see Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010 for a business model 'canvas'). The

business model, specifically, has recently gained widespread interest and application among

scholars and managers as a helpful tool for both thinking about and creating systems of value

creation, delivery and capture (for a review see Zott, Amit & Massa, 2011).

Business models can be represented in many forms, and employing a particular style of

representation can affect the associated thinking processes and thus the model’s functionality

(Martins et al., 2015). However, several recent scholarly representations of business models -

despite being grounded in different theoretical premises - have in common the fact that they

are conceived as combinations of sub-categories populated by consistent elements (see

among others the classifications by Baden-Fuller & Mangematin, 2013; Demil & Lecocq,

2010; Massa & Tucci, 2013; Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010; Zott & Amit, 2010). Also, the

popularity of tools such as the ‘business model canvas’ (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010)

among practitioners seems to suggest that even managers are at ease with representing

business models as simplified systems of interconnected elements. Thus we start from the

situation where a model for business is considered relevant and useful (Morgan, 2012), and

cognitive efforts to represent “business models as models” (Baden-Fuller & Morgan, 2010)

are important in order for the role of business models as “manipulable instruments” (i.e.,

instruments that can be voluntarily shaped and changed to gather insight) to be enacted.

These in turn can be helpful in assisting scholarly and managerial reflection both on what a

firm does (or could do) to create and capture value, and on how it can be modeled and

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 3

3

innovated to fit changing technological or market conditions (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger,

2013).

In this paper, we refer to business modeling as the set of cognitive actions aimed at

representing (complex) business activities in a parsimonious, simplified form (i.e., a business

model), as well as to the set of activities that cognitively manipulate the business model to

evaluate alternative ways in which it could be designed. These activities are the antecedents

of business model innovation, which - however radical or incremental - often constitute a

change in a business model that is commonly perceived as useful in its representation, and

which scholars often connect to an opportunity for performance enhancement (Zott & Amit,

2007, 2008). Once implemented, business model innovation may lead on to sustainable

business operations, or it may fail: but we leave it to past and future research as well as

management practice to engage with the perils of execution. Beyond this, what is noteworthy

here is that scholars seem to share a growing interest in the underlying idea of modeling a

business model, which is tightly connected to other popular concepts such as business model

innovation (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013; Chesbrough, 2010; Gambardella & McGahan,

2010), renewal (Chesbrough, 2010), evolution (Doz & Kosonen, 2010), and design (Demil &

Lecocq, 2010; Zott & Amit, 2010). This growing stream of research reflects the importance

of understanding the underlying dynamics related to business model experimentation and

manipulation, which often represent the most common option for firms needing to respond to

changing environments or fierce competition.

Despite the fact that scholars have provided multiple suggestions as to how to represent

business models, surprisingly little is known about the different ways in which such models

can be manipulated and how such actions can help change existing business models, even

though there has been much interest in manipulation as a tool to support experimentation,

innovation, and performance (Zott & Amit, 2007, 2010), and in manipulability as a

fundamental property of any model (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013; Baden-Fuller &

Morgan, 2010). As an instrument for reasoning, the business model supports fundamental

management decisions for both early-stage and mature businesses; but while the idea of the

application of business models as a way to design new startup ventures has taken hold easily

(Gambardella & McGahan, 2010; Zott & Amit, 2007), such inquiry appears to have been

more difficult (and thus less investigated) in the realms of mature firms, where issues of

endogeneity, inertia, and complexity can pose additional problems. Hence, it is even more

valuable to consider the business model as a cognitive and analytical tool to play with

alternative scenarios for existing businesses, and to model various possible outcomes of

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 3

3

innovated to fit changing technological or market conditions (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger,

2013).

In this paper, we refer to business modeling as the set of cognitive actions aimed at

representing (complex) business activities in a parsimonious, simplified form (i.e., a business

model), as well as to the set of activities that cognitively manipulate the business model to

evaluate alternative ways in which it could be designed. These activities are the antecedents

of business model innovation, which - however radical or incremental - often constitute a

change in a business model that is commonly perceived as useful in its representation, and

which scholars often connect to an opportunity for performance enhancement (Zott & Amit,

2007, 2008). Once implemented, business model innovation may lead on to sustainable

business operations, or it may fail: but we leave it to past and future research as well as

management practice to engage with the perils of execution. Beyond this, what is noteworthy

here is that scholars seem to share a growing interest in the underlying idea of modeling a

business model, which is tightly connected to other popular concepts such as business model

innovation (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013; Chesbrough, 2010; Gambardella & McGahan,

2010), renewal (Chesbrough, 2010), evolution (Doz & Kosonen, 2010), and design (Demil &

Lecocq, 2010; Zott & Amit, 2010). This growing stream of research reflects the importance

of understanding the underlying dynamics related to business model experimentation and

manipulation, which often represent the most common option for firms needing to respond to

changing environments or fierce competition.

Despite the fact that scholars have provided multiple suggestions as to how to represent

business models, surprisingly little is known about the different ways in which such models

can be manipulated and how such actions can help change existing business models, even

though there has been much interest in manipulation as a tool to support experimentation,

innovation, and performance (Zott & Amit, 2007, 2010), and in manipulability as a

fundamental property of any model (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013; Baden-Fuller &

Morgan, 2010). As an instrument for reasoning, the business model supports fundamental

management decisions for both early-stage and mature businesses; but while the idea of the

application of business models as a way to design new startup ventures has taken hold easily

(Gambardella & McGahan, 2010; Zott & Amit, 2007), such inquiry appears to have been

more difficult (and thus less investigated) in the realms of mature firms, where issues of

endogeneity, inertia, and complexity can pose additional problems. Hence, it is even more

valuable to consider the business model as a cognitive and analytical tool to play with

alternative scenarios for existing businesses, and to model various possible outcomes of

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 4

4

strategic decisions. Also, despite the increasing interest in phenomena related to business

model innovation, as well as their paramount importance, we still lack a clear understanding

of the basic options for change in existing business models. In this study we tackle this

important aspect by investigating the following research question: How can we systematically

understand and classify the manipulations of a business model?

To respond to this question, we borrow from the theory of complex systems, and in particular

from Simon (1962), who viewed modular systems as the result of deliberate human activity:

i.e., that artifacts and social systems are conceived of as being composed of other subsystems.

Attempts at modeling a new instantiation of an existing business model necessarily encounter

the difficulties of modularization and manipulation as well as the opportunities and

limitations of decomposability and information hiding. To follow this theoretical perspective,

we consider the business model as a system of interconnected parts, which stand for sub-

categories populated by constituent elements, such as a business’ monetization mechanisms.

Our approach resonates with previous themes in the business model literature. As Massa and

Tucci (2013) highlight, the level of abstraction of business model representations among

scholars and practitioners varies between being more or less granular (i.e., including more or

less elements, depending on the level of analysis), but the different classifications still tend to

remain consistently represented in terms of the inter-relatedness of their elements. We

suggest that this system approach offers a basis to understand how business models might

change and, particularly, how firms might conceive such innovations as, for instance, the

move from ‘product’ to ‘multi-sided platform’ business models, or from vertically integrated

towards networked arrangements.

Other contributions in the strategic management literature on the economies of substitution

(Garud & Kumaraswamy, 1993, 1995) follow a similar logic: economies of substitution

“exist when the cost of designing a higher-performance system through the partial retention

of existing components is lower than the cost of designing the system afresh” (Garud &

Kumaraswamy, 1993: 362). Modularization reduces costly transactions that prevent the

benefits of modular systems from materializing (Garud & Kumaraswamy, 1995: 96).

Modular designs - when possible and effectively implemented - allow for the achievement of

greater system flexibility, along with the benefits coming from increased division of labor

and specialization (Garud & Kumaraswamy, 1995). Moreover, components of modular

systems can be mixed and matched in specific system designs, both to allow for larger

product variety via element recombination (Devetag & Zaninotto, 2001), or to increase the

overall value of existing solutions (Langlois & Robertson, 1992). In other words, elements in

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 4

4

strategic decisions. Also, despite the increasing interest in phenomena related to business

model innovation, as well as their paramount importance, we still lack a clear understanding

of the basic options for change in existing business models. In this study we tackle this

important aspect by investigating the following research question: How can we systematically

understand and classify the manipulations of a business model?

To respond to this question, we borrow from the theory of complex systems, and in particular

from Simon (1962), who viewed modular systems as the result of deliberate human activity:

i.e., that artifacts and social systems are conceived of as being composed of other subsystems.

Attempts at modeling a new instantiation of an existing business model necessarily encounter

the difficulties of modularization and manipulation as well as the opportunities and

limitations of decomposability and information hiding. To follow this theoretical perspective,

we consider the business model as a system of interconnected parts, which stand for sub-

categories populated by constituent elements, such as a business’ monetization mechanisms.

Our approach resonates with previous themes in the business model literature. As Massa and

Tucci (2013) highlight, the level of abstraction of business model representations among

scholars and practitioners varies between being more or less granular (i.e., including more or

less elements, depending on the level of analysis), but the different classifications still tend to

remain consistently represented in terms of the inter-relatedness of their elements. We

suggest that this system approach offers a basis to understand how business models might

change and, particularly, how firms might conceive such innovations as, for instance, the

move from ‘product’ to ‘multi-sided platform’ business models, or from vertically integrated

towards networked arrangements.

Other contributions in the strategic management literature on the economies of substitution

(Garud & Kumaraswamy, 1993, 1995) follow a similar logic: economies of substitution

“exist when the cost of designing a higher-performance system through the partial retention

of existing components is lower than the cost of designing the system afresh” (Garud &

Kumaraswamy, 1993: 362). Modularization reduces costly transactions that prevent the

benefits of modular systems from materializing (Garud & Kumaraswamy, 1995: 96).

Modular designs - when possible and effectively implemented - allow for the achievement of

greater system flexibility, along with the benefits coming from increased division of labor

and specialization (Garud & Kumaraswamy, 1995). Moreover, components of modular

systems can be mixed and matched in specific system designs, both to allow for larger

product variety via element recombination (Devetag & Zaninotto, 2001), or to increase the

overall value of existing solutions (Langlois & Robertson, 1992). In other words, elements in

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 5

5

modular designs show high degrees of manipulability, which enable efficient and effective

experimentation in terms of novel, innovative configurations. If we can conceive of business

models in terms of the principles of modularity, the notion of manipulability can facilitate

changes in their design, which may lead to significant innovation for firms.

Since its very early days, the business model debate has been tightly intertwined with

technology and innovation (Amit & Zott, 2001; Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013;

Chesbrough, 2010; Gambardella & McGahan, 2010), particularly, the discussion of how the

diffusion of the Internet allowed firms to introduce new business models or innovate their

existing ones (Amit & Zott, 2001; Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013). For instance, the degree

of modularity embedded in many information-intensive artifacts - such as ICT-based

products and services (Yoo, Boland Jr, Lyytinen & Majchrzak, 2012) - has promoted the

emergence of platform business models, also referred to as multi-sided business models

(Rochet & Tirole, 2003; 2006). These allow different sides of a market to be connected via

multiple technological platforms and technological domains (consider for example how

Amazon, Google, or Airbnb platforms engage with different categories of users in

exchanging goods, services, or other scarce resources, e.g., customer attention). Thus

technological modularity has remained at the very core of the business model debate, and

scholars have paid increasing attention to the benefits of modular technologies for business

model innovation, to the point of starting to question whether business models themselves

can actually be modular, and how their modularity might be related to the modularity of their

enabling technologies (Bonina & Liebenau, 2015; Kodama, 2004; Parmatier, 2015).

Modularity in technologies may or may not foster modularity at the business model

level: but it is not our goal here to investigate whether modularity in a technology triggers

modularity in a business model, but rather to investigate how we can conceive and change

business models using ideas of modularity and manipulation (i.e., voluntary change), whether

or not technological change is involved. This is particularly important because, despite the

principles of manipulation and modularity in modeling being a common theme in the

literature of business models, we still lack a clear theoretical distinction between modularity

theory as applied to technologies vs. as applied to business models. In these regards, we argue

that scholarship needs to address three aspects promptly: (1) defining what modularity means

in business model terms (and, by implication, how it might or might not differ from

modularity in technology); (2) understanding what are the cognitive processes supporting

business modeling in modular terms, and how the cognitive reasoning involved relates to real

world activities; (3) identifying the boundary conditions that determine whether modularity

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 5

5

modular designs show high degrees of manipulability, which enable efficient and effective

experimentation in terms of novel, innovative configurations. If we can conceive of business

models in terms of the principles of modularity, the notion of manipulability can facilitate

changes in their design, which may lead to significant innovation for firms.

Since its very early days, the business model debate has been tightly intertwined with

technology and innovation (Amit & Zott, 2001; Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013;

Chesbrough, 2010; Gambardella & McGahan, 2010), particularly, the discussion of how the

diffusion of the Internet allowed firms to introduce new business models or innovate their

existing ones (Amit & Zott, 2001; Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013). For instance, the degree

of modularity embedded in many information-intensive artifacts - such as ICT-based

products and services (Yoo, Boland Jr, Lyytinen & Majchrzak, 2012) - has promoted the

emergence of platform business models, also referred to as multi-sided business models

(Rochet & Tirole, 2003; 2006). These allow different sides of a market to be connected via

multiple technological platforms and technological domains (consider for example how

Amazon, Google, or Airbnb platforms engage with different categories of users in

exchanging goods, services, or other scarce resources, e.g., customer attention). Thus

technological modularity has remained at the very core of the business model debate, and

scholars have paid increasing attention to the benefits of modular technologies for business

model innovation, to the point of starting to question whether business models themselves

can actually be modular, and how their modularity might be related to the modularity of their

enabling technologies (Bonina & Liebenau, 2015; Kodama, 2004; Parmatier, 2015).

Modularity in technologies may or may not foster modularity at the business model

level: but it is not our goal here to investigate whether modularity in a technology triggers

modularity in a business model, but rather to investigate how we can conceive and change

business models using ideas of modularity and manipulation (i.e., voluntary change), whether

or not technological change is involved. This is particularly important because, despite the

principles of manipulation and modularity in modeling being a common theme in the

literature of business models, we still lack a clear theoretical distinction between modularity

theory as applied to technologies vs. as applied to business models. In these regards, we argue

that scholarship needs to address three aspects promptly: (1) defining what modularity means

in business model terms (and, by implication, how it might or might not differ from

modularity in technology); (2) understanding what are the cognitive processes supporting

business modeling in modular terms, and how the cognitive reasoning involved relates to real

world activities; (3) identifying the boundary conditions that determine whether modularity

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 6

6

theory can be applied to business models and modeling. Finally, we suggest that modularity

is a viable theory to inquire into business models due to its own constituting logics that have

also allowed its previous application to organizational contexts (see for example Brusoni,

Marengo, Prencipe & Valente, 2007; Brusoni & Prencipe, 2001a).

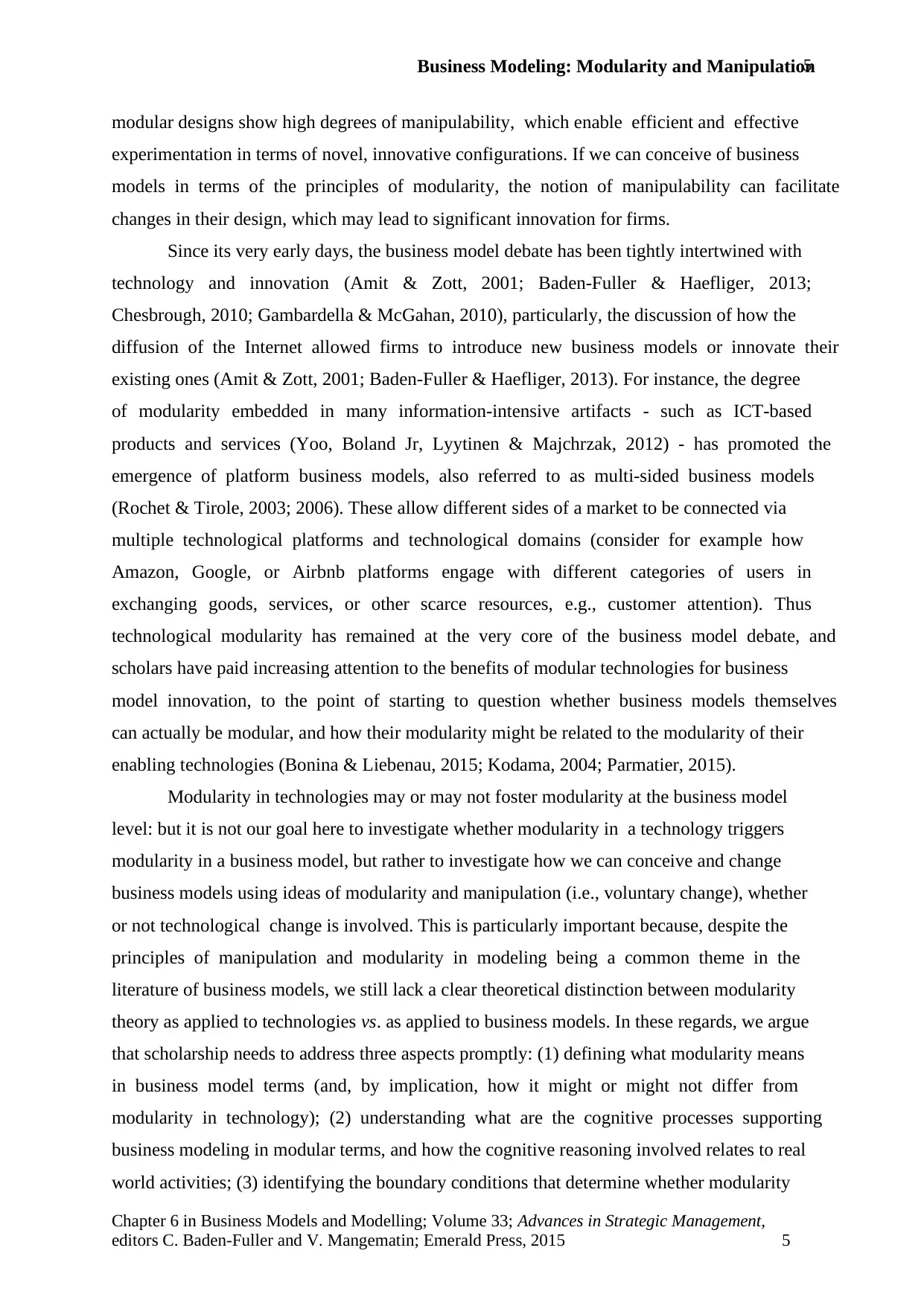

We characterize our approach to business models as one that focuses on cognitive

modeling, rather than real world execution. Business modeling can be divided into three

phases (see Table 1). Thinking is the cognitive effort to inquire into the business, and usually

corresponds to the individual effort of cognitively understanding a business. Articulating is

the individual cognitive effort to represent the business in a parsimonious and simplified

model, so that it may be conveniently shared with other stakeholders, whose interactions may

affect the model representation itself. The articulation phase may involve considering

possible modifications to the original business model, achieved via cognitive manipulation - a

phase in which individuals and groups cognitively ‘tinker’ with possible alternatives to

optimize their business model. Finally, the doing phase implies a series of decisions and

routines to translate the cognitive model into a set of activities in the real world of business,

which involves grappling with the messy details of technology. Table 1 refers to the complex

challenges managers face when designing a business model.

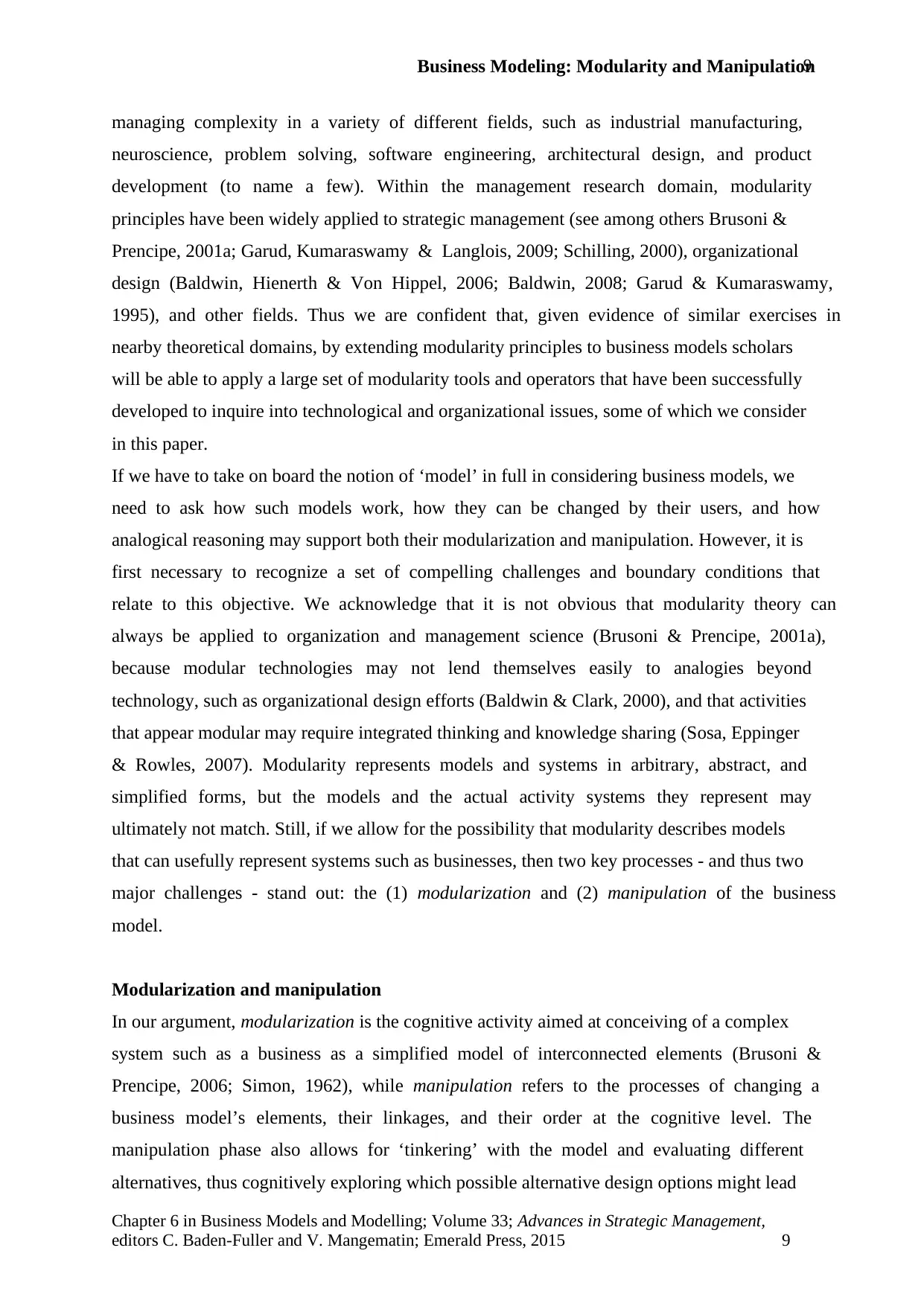

Table 1: Business model thinking, articulating, doing: challenges for a modularity

perspective

Thinking Articulating Doing

Focus of process Perspective Representation and change Execution in action

Actors involved Individual Collective within the firm

(stakeholders, managers,

board)

Collective within and

outside the firm

Relevant input Data on organization

and environment

Simplification and

representation;

options/alternatives

Decisions, actions and

routines

Translation Identification,

reflection, analysis and

deconstruction

Calibration, extrapolation,

simplification, sharing,

evaluation of the alternative

options, simulation

Sense making and

sense giving

Challenges for

modularity theory

Identification of what

composes a business

(cognitive exercise)

Modularization and

manipulation of the

business model elements

representing the processes

to create and capture value

(cognitive and theoretical

exercise)

Implementation of

activity systems that

lead to business results

(real world exercise)

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 6

6

theory can be applied to business models and modeling. Finally, we suggest that modularity

is a viable theory to inquire into business models due to its own constituting logics that have

also allowed its previous application to organizational contexts (see for example Brusoni,

Marengo, Prencipe & Valente, 2007; Brusoni & Prencipe, 2001a).

We characterize our approach to business models as one that focuses on cognitive

modeling, rather than real world execution. Business modeling can be divided into three

phases (see Table 1). Thinking is the cognitive effort to inquire into the business, and usually

corresponds to the individual effort of cognitively understanding a business. Articulating is

the individual cognitive effort to represent the business in a parsimonious and simplified

model, so that it may be conveniently shared with other stakeholders, whose interactions may

affect the model representation itself. The articulation phase may involve considering

possible modifications to the original business model, achieved via cognitive manipulation - a

phase in which individuals and groups cognitively ‘tinker’ with possible alternatives to

optimize their business model. Finally, the doing phase implies a series of decisions and

routines to translate the cognitive model into a set of activities in the real world of business,

which involves grappling with the messy details of technology. Table 1 refers to the complex

challenges managers face when designing a business model.

Table 1: Business model thinking, articulating, doing: challenges for a modularity

perspective

Thinking Articulating Doing

Focus of process Perspective Representation and change Execution in action

Actors involved Individual Collective within the firm

(stakeholders, managers,

board)

Collective within and

outside the firm

Relevant input Data on organization

and environment

Simplification and

representation;

options/alternatives

Decisions, actions and

routines

Translation Identification,

reflection, analysis and

deconstruction

Calibration, extrapolation,

simplification, sharing,

evaluation of the alternative

options, simulation

Sense making and

sense giving

Challenges for

modularity theory

Identification of what

composes a business

(cognitive exercise)

Modularization and

manipulation of the

business model elements

representing the processes

to create and capture value

(cognitive and theoretical

exercise)

Implementation of

activity systems that

lead to business results

(real world exercise)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 7

7

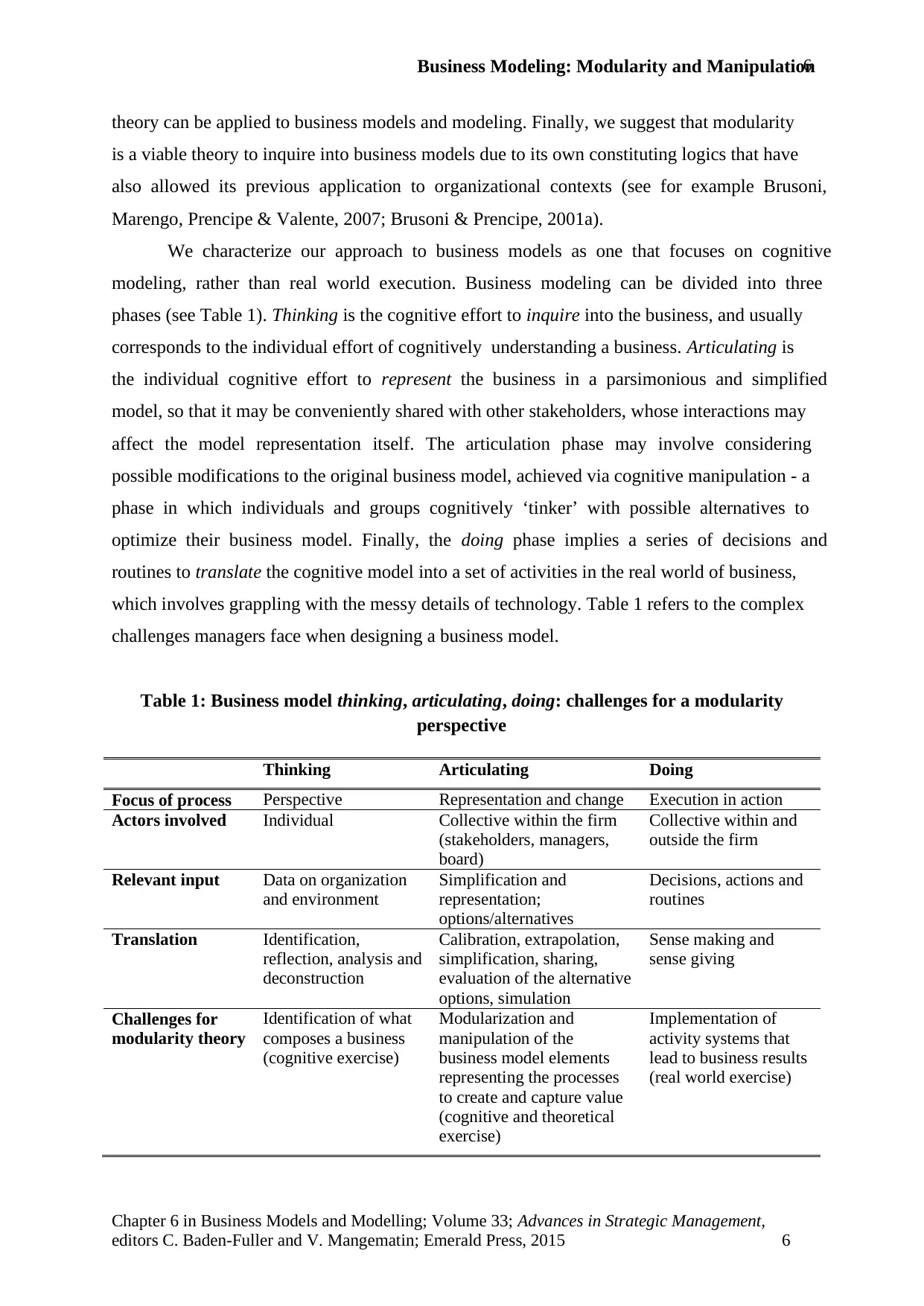

Our paper proceeds by considering the concept of elements (i.e., components of a

system/mode) as well as the constituting principles of modularity theory. Specifically, we

consider two key notions of the business model construct: first, the modularization of the

business model - which includes the possibility of representing a model via a set of

interconnected elements. And second, we consider the manipulation of those interconnected

elements – and so ‘inquiring into’ the challenges of modeling a business model. We also

consider the benefits and risks of two basic properties of modular models, namely

decomposability (Simon, 1962), and information hiding (Parnas, 1972).

Once the necessary principles are identified, we then tackle the thorny problem of

understanding and classifying business model changes (i.e., manipulations) through

modularity operators. To substantiate this abstract reasoning more fully, we first define these

operators according to modularity theory (Baldwin & Clark, 2000; Parnas, 1972), and show

how they have been originally applied to examples within the technology domain. Second,

following analogical reasoning (Gavetti, Levinthal & Rivkin, 2005; Martins et al., 2015), we

identify iconic examples of innovation in the business model domain and, by appreciating the

salient changes, identify the types of changes that are analogous to change cases in

technology. In particular, we follow three general constituting elements of the business model

(i.e., value creation, delivery, and capture) and the changes they undergo that are comparable

to our technology architecture examples, and make reference to current practical issues. We

generalize our arguments with a series of propositions that extract cognitive operators

explaining business model change. By applying modularity operators to business model

change, we are thus able to advance a precise classification of business model changes, which

can help both scholars and practitioners inquiring into different types of manipulations.

Finally, we ask how modularity may further help scholars respond to questions from the

contemporary business model research domain. We conclude with a set of suggestions for

future contributions, which represent a challenging research agenda whose trajectory points

to the intersection of business models, modeling, and modularity.

Modularity Theory and the Business Model

Essentially, modularity can be viewed both as an organizing strategy for understanding and

representing complex systems - such as artifact architectures or organization structures - in

terms of a series of self-contained and interlinked subsystems, variously labeled as “parts”

“components”, “elements” or “modules” (Baldwin & Clark, 2000; Baldwin & Clark, 2003;

Brusoni et al., 2007; Brusoni & Prencipe, 2001a). A system is more or less modular

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 7

7

Our paper proceeds by considering the concept of elements (i.e., components of a

system/mode) as well as the constituting principles of modularity theory. Specifically, we

consider two key notions of the business model construct: first, the modularization of the

business model - which includes the possibility of representing a model via a set of

interconnected elements. And second, we consider the manipulation of those interconnected

elements – and so ‘inquiring into’ the challenges of modeling a business model. We also

consider the benefits and risks of two basic properties of modular models, namely

decomposability (Simon, 1962), and information hiding (Parnas, 1972).

Once the necessary principles are identified, we then tackle the thorny problem of

understanding and classifying business model changes (i.e., manipulations) through

modularity operators. To substantiate this abstract reasoning more fully, we first define these

operators according to modularity theory (Baldwin & Clark, 2000; Parnas, 1972), and show

how they have been originally applied to examples within the technology domain. Second,

following analogical reasoning (Gavetti, Levinthal & Rivkin, 2005; Martins et al., 2015), we

identify iconic examples of innovation in the business model domain and, by appreciating the

salient changes, identify the types of changes that are analogous to change cases in

technology. In particular, we follow three general constituting elements of the business model

(i.e., value creation, delivery, and capture) and the changes they undergo that are comparable

to our technology architecture examples, and make reference to current practical issues. We

generalize our arguments with a series of propositions that extract cognitive operators

explaining business model change. By applying modularity operators to business model

change, we are thus able to advance a precise classification of business model changes, which

can help both scholars and practitioners inquiring into different types of manipulations.

Finally, we ask how modularity may further help scholars respond to questions from the

contemporary business model research domain. We conclude with a set of suggestions for

future contributions, which represent a challenging research agenda whose trajectory points

to the intersection of business models, modeling, and modularity.

Modularity Theory and the Business Model

Essentially, modularity can be viewed both as an organizing strategy for understanding and

representing complex systems - such as artifact architectures or organization structures - in

terms of a series of self-contained and interlinked subsystems, variously labeled as “parts”

“components”, “elements” or “modules” (Baldwin & Clark, 2000; Baldwin & Clark, 2003;

Brusoni et al., 2007; Brusoni & Prencipe, 2001a). A system is more or less modular

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 8

8

depending on the possibility that it could be decomposed into loosely coupled components,

and modularization can be seen as the process by which a system is structured according to a

modular design, or could be redesigned to achieve a higher degree of modularity (see Table 2

for a summary of the relevant definitions).

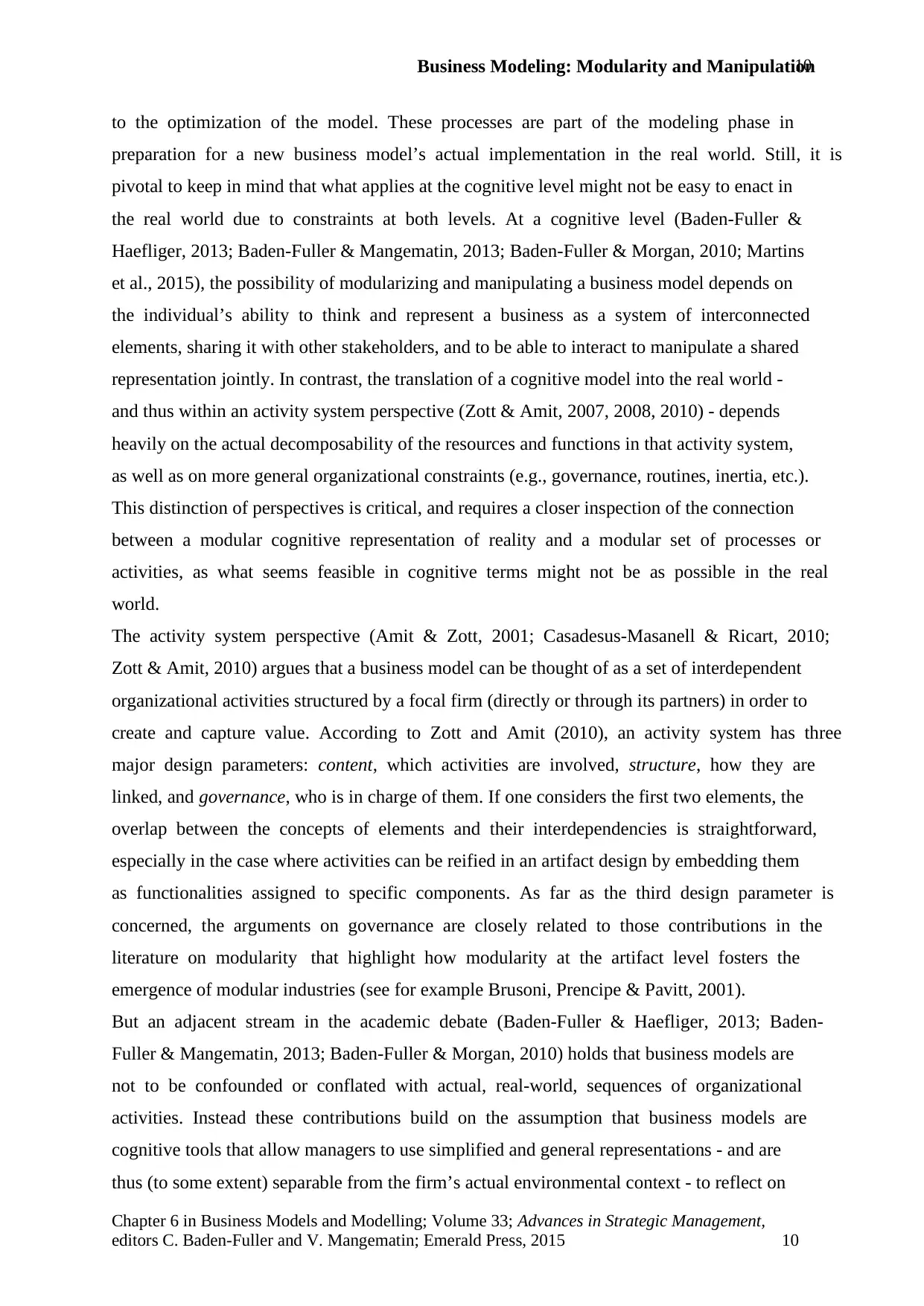

Table 2: Modularity in technology

Term Category Definition Example

Module Object A (conditionally) self-

contained subsystem

A PC is composed of several modules

such as CPU, hard disk, RAM, DVD

reader, video card, etc.

Modular Attribute The character of a system The PC architecture is modular in that

its subsystems can be recombined

according to various configurations

Modularity Pattern The degree to which a

complex system can be

conceived in terms of

subsystems

The PC modularity allows to extend

products life span by upgrading

individual components

Modularization Process The act of structuring (or

restructuring) a system in

modular terms

The history of computing is

characterized by the increasing

modularization of product designs

(e.g., the shift from mini-computers to

PCs)

It is important to acknowledge that our understanding of systems and modularity borrows

heavily from the original work of Simon (e.g., Simon, 1962) on modeling complex systems

and their decomposability. Simon’s contribution suggested that modeling is most fruitful if

the model of the system can be simplified and decomposed into parts. This allows

components that are less crucial to be put into ‘black boxes’ to focus more clearly on core

elements and thus facilitate their manipulation (for an appreciation of how and why Simon

influenced our thinking, see Boumans, 2009; Morgan, 1991). Following this line of

reasoning, we stress the cognitive nature of modeling activities, which implies that the actual

possibility of manipulating a model lies, above all, in the actors’ understanding of its

components and their interdependencies, rather than in the actual properties of the elements

and the model.

Similarly, current management theory draws heavily on Simon’s work, but also borrows from

more recent modularity theory (Baldwin & Clark, 2000) using an intellectual process of

analogical reasoning that also allows us to transfer approaches and toolkits based on the

theory of modularity (e.g., modular operators) from the technological to the business model

domain. In fact, modularity has risen to the level of being seen as a dominant paradigm for

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 8

8

depending on the possibility that it could be decomposed into loosely coupled components,

and modularization can be seen as the process by which a system is structured according to a

modular design, or could be redesigned to achieve a higher degree of modularity (see Table 2

for a summary of the relevant definitions).

Table 2: Modularity in technology

Term Category Definition Example

Module Object A (conditionally) self-

contained subsystem

A PC is composed of several modules

such as CPU, hard disk, RAM, DVD

reader, video card, etc.

Modular Attribute The character of a system The PC architecture is modular in that

its subsystems can be recombined

according to various configurations

Modularity Pattern The degree to which a

complex system can be

conceived in terms of

subsystems

The PC modularity allows to extend

products life span by upgrading

individual components

Modularization Process The act of structuring (or

restructuring) a system in

modular terms

The history of computing is

characterized by the increasing

modularization of product designs

(e.g., the shift from mini-computers to

PCs)

It is important to acknowledge that our understanding of systems and modularity borrows

heavily from the original work of Simon (e.g., Simon, 1962) on modeling complex systems

and their decomposability. Simon’s contribution suggested that modeling is most fruitful if

the model of the system can be simplified and decomposed into parts. This allows

components that are less crucial to be put into ‘black boxes’ to focus more clearly on core

elements and thus facilitate their manipulation (for an appreciation of how and why Simon

influenced our thinking, see Boumans, 2009; Morgan, 1991). Following this line of

reasoning, we stress the cognitive nature of modeling activities, which implies that the actual

possibility of manipulating a model lies, above all, in the actors’ understanding of its

components and their interdependencies, rather than in the actual properties of the elements

and the model.

Similarly, current management theory draws heavily on Simon’s work, but also borrows from

more recent modularity theory (Baldwin & Clark, 2000) using an intellectual process of

analogical reasoning that also allows us to transfer approaches and toolkits based on the

theory of modularity (e.g., modular operators) from the technological to the business model

domain. In fact, modularity has risen to the level of being seen as a dominant paradigm for

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 9

9

managing complexity in a variety of different fields, such as industrial manufacturing,

neuroscience, problem solving, software engineering, architectural design, and product

development (to name a few). Within the management research domain, modularity

principles have been widely applied to strategic management (see among others Brusoni &

Prencipe, 2001a; Garud, Kumaraswamy & Langlois, 2009; Schilling, 2000), organizational

design (Baldwin, Hienerth & Von Hippel, 2006; Baldwin, 2008; Garud & Kumaraswamy,

1995), and other fields. Thus we are confident that, given evidence of similar exercises in

nearby theoretical domains, by extending modularity principles to business models scholars

will be able to apply a large set of modularity tools and operators that have been successfully

developed to inquire into technological and organizational issues, some of which we consider

in this paper.

If we have to take on board the notion of ‘model’ in full in considering business models, we

need to ask how such models work, how they can be changed by their users, and how

analogical reasoning may support both their modularization and manipulation. However, it is

first necessary to recognize a set of compelling challenges and boundary conditions that

relate to this objective. We acknowledge that it is not obvious that modularity theory can

always be applied to organization and management science (Brusoni & Prencipe, 2001a),

because modular technologies may not lend themselves easily to analogies beyond

technology, such as organizational design efforts (Baldwin & Clark, 2000), and that activities

that appear modular may require integrated thinking and knowledge sharing (Sosa, Eppinger

& Rowles, 2007). Modularity represents models and systems in arbitrary, abstract, and

simplified forms, but the models and the actual activity systems they represent may

ultimately not match. Still, if we allow for the possibility that modularity describes models

that can usefully represent systems such as businesses, then two key processes - and thus two

major challenges - stand out: the (1) modularization and (2) manipulation of the business

model.

Modularization and manipulation

In our argument, modularization is the cognitive activity aimed at conceiving of a complex

system such as a business as a simplified model of interconnected elements (Brusoni &

Prencipe, 2006; Simon, 1962), while manipulation refers to the processes of changing a

business model’s elements, their linkages, and their order at the cognitive level. The

manipulation phase also allows for ‘tinkering’ with the model and evaluating different

alternatives, thus cognitively exploring which possible alternative design options might lead

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 9

9

managing complexity in a variety of different fields, such as industrial manufacturing,

neuroscience, problem solving, software engineering, architectural design, and product

development (to name a few). Within the management research domain, modularity

principles have been widely applied to strategic management (see among others Brusoni &

Prencipe, 2001a; Garud, Kumaraswamy & Langlois, 2009; Schilling, 2000), organizational

design (Baldwin, Hienerth & Von Hippel, 2006; Baldwin, 2008; Garud & Kumaraswamy,

1995), and other fields. Thus we are confident that, given evidence of similar exercises in

nearby theoretical domains, by extending modularity principles to business models scholars

will be able to apply a large set of modularity tools and operators that have been successfully

developed to inquire into technological and organizational issues, some of which we consider

in this paper.

If we have to take on board the notion of ‘model’ in full in considering business models, we

need to ask how such models work, how they can be changed by their users, and how

analogical reasoning may support both their modularization and manipulation. However, it is

first necessary to recognize a set of compelling challenges and boundary conditions that

relate to this objective. We acknowledge that it is not obvious that modularity theory can

always be applied to organization and management science (Brusoni & Prencipe, 2001a),

because modular technologies may not lend themselves easily to analogies beyond

technology, such as organizational design efforts (Baldwin & Clark, 2000), and that activities

that appear modular may require integrated thinking and knowledge sharing (Sosa, Eppinger

& Rowles, 2007). Modularity represents models and systems in arbitrary, abstract, and

simplified forms, but the models and the actual activity systems they represent may

ultimately not match. Still, if we allow for the possibility that modularity describes models

that can usefully represent systems such as businesses, then two key processes - and thus two

major challenges - stand out: the (1) modularization and (2) manipulation of the business

model.

Modularization and manipulation

In our argument, modularization is the cognitive activity aimed at conceiving of a complex

system such as a business as a simplified model of interconnected elements (Brusoni &

Prencipe, 2006; Simon, 1962), while manipulation refers to the processes of changing a

business model’s elements, their linkages, and their order at the cognitive level. The

manipulation phase also allows for ‘tinkering’ with the model and evaluating different

alternatives, thus cognitively exploring which possible alternative design options might lead

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 10

10

to the optimization of the model. These processes are part of the modeling phase in

preparation for a new business model’s actual implementation in the real world. Still, it is

pivotal to keep in mind that what applies at the cognitive level might not be easy to enact in

the real world due to constraints at both levels. At a cognitive level (Baden-Fuller &

Haefliger, 2013; Baden-Fuller & Mangematin, 2013; Baden-Fuller & Morgan, 2010; Martins

et al., 2015), the possibility of modularizing and manipulating a business model depends on

the individual’s ability to think and represent a business as a system of interconnected

elements, sharing it with other stakeholders, and to be able to interact to manipulate a shared

representation jointly. In contrast, the translation of a cognitive model into the real world -

and thus within an activity system perspective (Zott & Amit, 2007, 2008, 2010) - depends

heavily on the actual decomposability of the resources and functions in that activity system,

as well as on more general organizational constraints (e.g., governance, routines, inertia, etc.).

This distinction of perspectives is critical, and requires a closer inspection of the connection

between a modular cognitive representation of reality and a modular set of processes or

activities, as what seems feasible in cognitive terms might not be as possible in the real

world.

The activity system perspective (Amit & Zott, 2001; Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010;

Zott & Amit, 2010) argues that a business model can be thought of as a set of interdependent

organizational activities structured by a focal firm (directly or through its partners) in order to

create and capture value. According to Zott and Amit (2010), an activity system has three

major design parameters: content, which activities are involved, structure, how they are

linked, and governance, who is in charge of them. If one considers the first two elements, the

overlap between the concepts of elements and their interdependencies is straightforward,

especially in the case where activities can be reified in an artifact design by embedding them

as functionalities assigned to specific components. As far as the third design parameter is

concerned, the arguments on governance are closely related to those contributions in the

literature on modularity that highlight how modularity at the artifact level fosters the

emergence of modular industries (see for example Brusoni, Prencipe & Pavitt, 2001).

But an adjacent stream in the academic debate (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013; Baden-

Fuller & Mangematin, 2013; Baden-Fuller & Morgan, 2010) holds that business models are

not to be confounded or conflated with actual, real-world, sequences of organizational

activities. Instead these contributions build on the assumption that business models are

cognitive tools that allow managers to use simplified and general representations - and are

thus (to some extent) separable from the firm’s actual environmental context - to reflect on

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 10

10

to the optimization of the model. These processes are part of the modeling phase in

preparation for a new business model’s actual implementation in the real world. Still, it is

pivotal to keep in mind that what applies at the cognitive level might not be easy to enact in

the real world due to constraints at both levels. At a cognitive level (Baden-Fuller &

Haefliger, 2013; Baden-Fuller & Mangematin, 2013; Baden-Fuller & Morgan, 2010; Martins

et al., 2015), the possibility of modularizing and manipulating a business model depends on

the individual’s ability to think and represent a business as a system of interconnected

elements, sharing it with other stakeholders, and to be able to interact to manipulate a shared

representation jointly. In contrast, the translation of a cognitive model into the real world -

and thus within an activity system perspective (Zott & Amit, 2007, 2008, 2010) - depends

heavily on the actual decomposability of the resources and functions in that activity system,

as well as on more general organizational constraints (e.g., governance, routines, inertia, etc.).

This distinction of perspectives is critical, and requires a closer inspection of the connection

between a modular cognitive representation of reality and a modular set of processes or

activities, as what seems feasible in cognitive terms might not be as possible in the real

world.

The activity system perspective (Amit & Zott, 2001; Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010;

Zott & Amit, 2010) argues that a business model can be thought of as a set of interdependent

organizational activities structured by a focal firm (directly or through its partners) in order to

create and capture value. According to Zott and Amit (2010), an activity system has three

major design parameters: content, which activities are involved, structure, how they are

linked, and governance, who is in charge of them. If one considers the first two elements, the

overlap between the concepts of elements and their interdependencies is straightforward,

especially in the case where activities can be reified in an artifact design by embedding them

as functionalities assigned to specific components. As far as the third design parameter is

concerned, the arguments on governance are closely related to those contributions in the

literature on modularity that highlight how modularity at the artifact level fosters the

emergence of modular industries (see for example Brusoni, Prencipe & Pavitt, 2001).

But an adjacent stream in the academic debate (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013; Baden-

Fuller & Mangematin, 2013; Baden-Fuller & Morgan, 2010) holds that business models are

not to be confounded or conflated with actual, real-world, sequences of organizational

activities. Instead these contributions build on the assumption that business models are

cognitive tools that allow managers to use simplified and general representations - and are

thus (to some extent) separable from the firm’s actual environmental context - to reflect on

Business Modeling: Modularity and Manipulation

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 11

11

the essence of their business, and to make meaningful inferences in terms of cause-effect

relationships between their various constituent parts. Following this line of reasoning, we

need to distinguish between the organizational domain and its modularity and the business

model representations in the managers’ minds - that is, the distinction between real world and

cognitive representations.

Our argument heeds the complexity involved in understanding the nature of the

relations between the elements that allows for their manipulation. In order to be seen and

understood as a modular design, and thus be manipulated, considering a business as a system

of interconnected components also needs a higher level of abstraction that entails a series of

cognitive steps, such as: (1) understanding which functionalities are involved in the business

model as a whole; (2) assigning these functionalities to the various business model elements;

(3) discerning which of those elements are the focus of attention, and appreciating the

interactions between them; and (4) decoupling their interdependencies, as much as possible.

None of this can be taken for granted: the cognitive part of this process - which is bounded by

the individual’s rationality - might not be aligned with the actual configuration of resources

and activities in the real world. Modularization is a useful practice that prepares the ground

for, but does not necessarily guarantee, manipulation. The actor might not be able to

manipulate the system in its current state, either because of cognitive limitations on their

logical skills or because of actual real world constraints.

Undertaking modeling is not trivial. We know that many managers find manipulating

models difficult. Although they recognize the importance of the value creation, value capture,

and value delivery elements as a narrative of their businesses, they typically try to model

everything at once, and are not able to fully articulate how those individual parts interact and

how they contribute to their firm’s performance. Not being able to focus on what is core to

their business, and then to conceptualize a business model in terms of a limited number of

sub-elements (and embrace the principles of modularity) appears to inhibit understanding,

and thus manipulation. As in the case of the design of complex artifacts, it is therefore

important to note that embracing modularity is the result of a deliberate problem-solving

approach, where a complex phenomenon is tackled by decomposing it into quasi-independent

sub-components or sub-problems.

Choosing the locus of attention

All in all, while comprehensible and relatively straightforward as an idea, actually creating

and adopting representations is not a trivial task. Choosing the focus of attention and the level

Chapter 6 in Business Models and Modelling; Volume 33; Advances in Strategic Management,

editors C. Baden-Fuller and V. Mangematin; Emerald Press, 2015 11

11

the essence of their business, and to make meaningful inferences in terms of cause-effect

relationships between their various constituent parts. Following this line of reasoning, we

need to distinguish between the organizational domain and its modularity and the business

model representations in the managers’ minds - that is, the distinction between real world and

cognitive representations.

Our argument heeds the complexity involved in understanding the nature of the

relations between the elements that allows for their manipulation. In order to be seen and

understood as a modular design, and thus be manipulated, considering a business as a system

of interconnected components also needs a higher level of abstraction that entails a series of

cognitive steps, such as: (1) understanding which functionalities are involved in the business

model as a whole; (2) assigning these functionalities to the various business model elements;

(3) discerning which of those elements are the focus of attention, and appreciating the

interactions between them; and (4) decoupling their interdependencies, as much as possible.

None of this can be taken for granted: the cognitive part of this process - which is bounded by

the individual’s rationality - might not be aligned with the actual configuration of resources

and activities in the real world. Modularization is a useful practice that prepares the ground

for, but does not necessarily guarantee, manipulation. The actor might not be able to

manipulate the system in its current state, either because of cognitive limitations on their

logical skills or because of actual real world constraints.

Undertaking modeling is not trivial. We know that many managers find manipulating

models difficult. Although they recognize the importance of the value creation, value capture,

and value delivery elements as a narrative of their businesses, they typically try to model

everything at once, and are not able to fully articulate how those individual parts interact and

how they contribute to their firm’s performance. Not being able to focus on what is core to

their business, and then to conceptualize a business model in terms of a limited number of

sub-elements (and embrace the principles of modularity) appears to inhibit understanding,

and thus manipulation. As in the case of the design of complex artifacts, it is therefore

important to note that embracing modularity is the result of a deliberate problem-solving

approach, where a complex phenomenon is tackled by decomposing it into quasi-independent

sub-components or sub-problems.

Choosing the locus of attention

All in all, while comprehensible and relatively straightforward as an idea, actually creating

and adopting representations is not a trivial task. Choosing the focus of attention and the level

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 35

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.