The Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids—An International Cross-Sectional Survey on Administration Forms

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|13

|10581

|87

AI Summary

The survey presented here was performed by the International Association for Cannabinoid Medicines (IACM), and is meant to contribute to the understanding of cannabinoid-based medicine by asking patients who used cannabis or cannabinoids detailed questions about their experiences with different methods of intake. The survey was completed by 953 participants from 31 countries, making this the largest international survey on a wide variety of users of cannabinoid-based medicine performed so far.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

This article was downloaded by: [University of Saskatchewan Library]

On: 20 September 2013, At: 05:31

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujpd20

The Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

International Cross-Sectional Survey on Administ

Forms

Arno Hazekamp Ph.D.

a f , Mark A. Ware M.D.

b , Kirsten R. Muller-Vahl M.D.

c , Donald

Abrams M.D.

d & Franjo Grotenhermen M.D.

e

a Head of Research and Development at Bedrocan BV, The Netherlands; Department of

Metabolomics, Faculty of Science , Leiden University , Leiden , The Netherlands

b Departments of Family Medicine and Anesthesia , McGill University , Montreal , QC ,

Canada

c Clinic of Psychiatry, Social Psychiatry and Psychotherapy , Hannover Medical School ,

Hannover , Germany

d Division of Hematology-Oncology, San Francisco General Hospital , University of Califor

San Francisco , CA

e Nova-institut , Huerth , Germany

f Head of Research and Development at Bedrocan BV , The Netherlands

Published online: 02 Aug 2013.

To cite this article: Arno Hazekamp Ph.D. , Mark A. Ware M.D. , Kirsten R. Muller-Vahl M.D. , Donald Abrams M.D. & F

Grotenhermen M.D. (2013) The Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids—An International Cross-Sectional Survey

Administration Forms, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45:3, 199-210, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2013.805976

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2013.805976

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained

in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the

Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and

are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and

should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for

any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of

the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic

reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://

www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

On: 20 September 2013, At: 05:31

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujpd20

The Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

International Cross-Sectional Survey on Administ

Forms

Arno Hazekamp Ph.D.

a f , Mark A. Ware M.D.

b , Kirsten R. Muller-Vahl M.D.

c , Donald

Abrams M.D.

d & Franjo Grotenhermen M.D.

e

a Head of Research and Development at Bedrocan BV, The Netherlands; Department of

Metabolomics, Faculty of Science , Leiden University , Leiden , The Netherlands

b Departments of Family Medicine and Anesthesia , McGill University , Montreal , QC ,

Canada

c Clinic of Psychiatry, Social Psychiatry and Psychotherapy , Hannover Medical School ,

Hannover , Germany

d Division of Hematology-Oncology, San Francisco General Hospital , University of Califor

San Francisco , CA

e Nova-institut , Huerth , Germany

f Head of Research and Development at Bedrocan BV , The Netherlands

Published online: 02 Aug 2013.

To cite this article: Arno Hazekamp Ph.D. , Mark A. Ware M.D. , Kirsten R. Muller-Vahl M.D. , Donald Abrams M.D. & F

Grotenhermen M.D. (2013) The Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids—An International Cross-Sectional Survey

Administration Forms, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45:3, 199-210, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2013.805976

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2013.805976

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained

in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the

Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and

are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and

should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for

any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of

the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic

reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://

www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45 (3), 199–210, 2013

Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0279-1072 print / 2159-9777 online

DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2013.805976

The Medicinal Use of Cannabis and

Cannabinoids—An International

Cross-Sectional Survey on

Administration Forms

Arno Hazekamp, Ph.D.a; Mark A. Ware, M.D.b; Kirsten R. Muller-Vahl, M.D.c; Donald Abrams, M.D.d

& Franjo Grotenhermen, M.D.e

Abstract — Cannabinoids, including tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol, are the most important

active constituents of the cannabis plant. Over recent years, cannabinoid-based medicines (CBMs)

have become increasingly available to patients in many countries, both as pharmaceutical products and

as herbal cannabis (marijuana). While there seems to be a demand for multiple cannabinoid-based ther-

apeutic products, specifically for symptomatic amelioration in chronic diseases, therapeutic effects of

different CBMs have only been directly compared in a few clinical studies. The survey presented here

was performed by the International Association for Cannabinoid Medicines (IACM), and is meant to

contribute to the understanding of cannabinoid-based medicine by asking patients who used cannabis

or cannabinoids detailed questions about their experiences with different methods of intake. The survey

was completed by 953 participants from 31 countries, making this the largest international survey on

a wide variety of users of cannabinoid-based medicine performed so far. In general, herbal non-phar-

maceutical CBMs received higher appreciation scores by participants than pharmaceutical products

containing cannabinoids. However, the number of patients who reported experience with pharma-

ceutical products was low, limiting conclusions on preferences. Nevertheless, the reported data may

be useful for further development of safe and effective medications based on cannabis and single

cannabinoids.

Keywords — administration form, cannabinoids, cannabis, comparative study, survey

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, cannabinoid-based medicines (CBMs)

have become increasingly available to patients in many

countries. These include several pharmaceutical prepara-

tions containing pure cannabinoids or cannabis extracts,

aHead of Research and Development at Bedrocan BV, The

Netherlands; Department of Plant Metabolomics, Faculty of Science,

Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands.

bDepartments of Family Medicine and Anesthesia, McGill

University, Montreal, QC, Canada.

cClinic of Psychiatry, Social Psychiatry and Psychotherapy,

Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany.

dDivision of Hematology-Oncology, San Francisco General

Hospital, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

eNova-institut, Huerth, Germany.

Please address correspondence to Arno Hazekamp, Ph.D.,

Department of Plant Metabolomics, Faculty of Science, Leiden

University, Sylviusweg 72, 2333BE, Leiden, The Netherlands; email:

ahazekamp@bedrocan.nl

as well as herbal cannabis (marijuana) products. The

most commonly prescribed cannabinoid-based medicines

are dronabinol (marketed as Marinol ® since 1986, Abbott

Products Inc.) and nabilone (marketed as Cesamet ® since

1981, Valeant Pharmaceuticals International). Dronabinol

is the INN (international non-proprietary name) of the nat-

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 199 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0279-1072 print / 2159-9777 online

DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2013.805976

The Medicinal Use of Cannabis and

Cannabinoids—An International

Cross-Sectional Survey on

Administration Forms

Arno Hazekamp, Ph.D.a; Mark A. Ware, M.D.b; Kirsten R. Muller-Vahl, M.D.c; Donald Abrams, M.D.d

& Franjo Grotenhermen, M.D.e

Abstract — Cannabinoids, including tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol, are the most important

active constituents of the cannabis plant. Over recent years, cannabinoid-based medicines (CBMs)

have become increasingly available to patients in many countries, both as pharmaceutical products and

as herbal cannabis (marijuana). While there seems to be a demand for multiple cannabinoid-based ther-

apeutic products, specifically for symptomatic amelioration in chronic diseases, therapeutic effects of

different CBMs have only been directly compared in a few clinical studies. The survey presented here

was performed by the International Association for Cannabinoid Medicines (IACM), and is meant to

contribute to the understanding of cannabinoid-based medicine by asking patients who used cannabis

or cannabinoids detailed questions about their experiences with different methods of intake. The survey

was completed by 953 participants from 31 countries, making this the largest international survey on

a wide variety of users of cannabinoid-based medicine performed so far. In general, herbal non-phar-

maceutical CBMs received higher appreciation scores by participants than pharmaceutical products

containing cannabinoids. However, the number of patients who reported experience with pharma-

ceutical products was low, limiting conclusions on preferences. Nevertheless, the reported data may

be useful for further development of safe and effective medications based on cannabis and single

cannabinoids.

Keywords — administration form, cannabinoids, cannabis, comparative study, survey

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, cannabinoid-based medicines (CBMs)

have become increasingly available to patients in many

countries. These include several pharmaceutical prepara-

tions containing pure cannabinoids or cannabis extracts,

aHead of Research and Development at Bedrocan BV, The

Netherlands; Department of Plant Metabolomics, Faculty of Science,

Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands.

bDepartments of Family Medicine and Anesthesia, McGill

University, Montreal, QC, Canada.

cClinic of Psychiatry, Social Psychiatry and Psychotherapy,

Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany.

dDivision of Hematology-Oncology, San Francisco General

Hospital, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

eNova-institut, Huerth, Germany.

Please address correspondence to Arno Hazekamp, Ph.D.,

Department of Plant Metabolomics, Faculty of Science, Leiden

University, Sylviusweg 72, 2333BE, Leiden, The Netherlands; email:

ahazekamp@bedrocan.nl

as well as herbal cannabis (marijuana) products. The

most commonly prescribed cannabinoid-based medicines

are dronabinol (marketed as Marinol ® since 1986, Abbott

Products Inc.) and nabilone (marketed as Cesamet ® since

1981, Valeant Pharmaceuticals International). Dronabinol

is the INN (international non-proprietary name) of the nat-

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 199 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

Hazekamp et al. Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

ural cannabinoid (-)-trans-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol,

usually abbreviated THC (WHO 2006). It may be extracted

from the plant, gained by isomerization of cannabidiol

(CBD), or manufactured synthetically. Marinol® is a syn-

thetic form of THC dissolved in sesame oil and prepared

in gelatin capsules, while nabilone is a synthetic ago-

nist of the human cannabinoid receptor (CB1), structurally

derived from a major human metabolite of THC. Both

products are registered for the symptomatic treatment of

nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy,

while dronabinol is also approved for treating anorexia and

cachexia related to HIV / AIDS. The patent on Marinol ®

expired in 2011, and an authorized generic version has

become available from Watson Pharmaceuticals. A generic

formulation of nabilone is now available in Canada from

Pharmascience Inc. In Germany, generic THC is supplied

by two companies (THC Pharm and Bionorica Ethics)

from which pharmacies can prepare capsules and solu-

tions (in oil or alcohol). The alcoholic solutions of THC

can either be used orally or inhaled by using a vapor-

izer (IACM 2009). About 7.5 kg of THC is delivered by

German pharmacies per year (WHO 2006).

Nabiximols (marketed as Sativex® since 2005 by

GW Pharmaceuticals, UK, and partners) is a sublingually

administered oromucosal spray based on a mixture of

two distinct standardized cannabis extracts. Its principal

active components are the plant-derived cannabinoids THC

and CBD. Sativex is currently registered in Canada, the

UK, Spain, Germany, Denmark, and New Zealand to treat

spasticity due to multiple sclerosis. In Canada, it is also

approved for the relief of neuropathic pain and advanced

cancer pain. Further approval is expected in other European

countries, based on the European Mutual Recognition

Procedure (GW Pharmaceuticals 2012).

Parallel to the development of pharmaceutical CBMs,

the number of countries providing a legal source of

medicinal-grade cannabis to chronically ill patients has

been growing as well. Canada (since 2001) and The

Netherlands (since 2003) have had government-run pro-

grams for the last decade, where quality-controlled herbal

cannabis is supplied by the specialized companies Prairie

Plant Systems Inc. and Bedrocan BV, respectively. Several

other countries are now setting up their own program

(Israel, Czech Republic) or importing products from the

Dutch program (Italy, Finland, Germany). In the US, the

number of states that introduced laws to permit the med-

ical use of cannabis has grown to 18 plus the District of

Columbia (DC), even though these state-level initiatives are

still prohibited by the federal government (IACM 2012).

In general, CBMs are used for symptomatic treat-

ment of chronic diseases refractory to standard treat-

ments. Because multiple biologically active cannabinoids

have been identified (including THC, CBD, tetrahy-

drocannabivarin (THCV) and THC-acid (THCA)), and

because CBMs can be administered in multiple ways (oral,

sublingual, inhaled), there seems to be a demand for multi-

ple cannabinoid-based therapeutic products. Nevertheless,

therapeutic effects of different CBMs have only been

directly compared in a few clinical studies. Most of these

studies compared an unregistered oral cannabis extract

(Cannador®) to Marinol ® (Zajicek 2003; 2005; Killestein

2002; Freeman 2006; Strasser 2006), while a few oth-

ers compared smoked cannabis to Marinol® (Haney 2005;

2007). The survey presented here was designed to con-

tribute to the understanding of cannabinoid-based medicine

by asking patients to compare the effects of different CBMs

and different administration forms. To the best of our

knowledge, this survey represents the largest systematic

study on actual patient experiences with cannabinoid-based

medicines currently available anywhere.

METHODOLOGY

We conducted an international, web-based, cross-

sectional survey to describe patients’ perceptions of dif-

ferent modes of administration for cannabinoid-based

medicines (complete survey available from first author).

The study was designed and conducted by the International

Association for Cannabinoid Medicines (IACM), which

has the goal to “advance knowledge on cannabis,

cannabinoids, the endocannabinoid system, and related

topics especially with regard to their therapeutic potential.”

The survey was posted on the official IACM website (http:/

/www.cannabis-med.org) from August 2009 until January

2010 in five different languages: English, French, Spanish,

German, and Dutch. To improve recruitment, the sur-

vey was brought to the attention of the approximately

5500 recipients of the IACM biweekly electronic newslet-

ter. The survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Hannover Medical School, Germany.

Subjects were a self-selected “availability sample” of

visitors to the IACM website; eligible subjects needed

to have experience with at least two different CBMs or

administration forms to be included. Participants remained

anonymous and received no financial compensation.

The survey consisted of 21 structured (fixed) ques-

tions that were answered by yes / no responses, multiple

choice lists, and rating scales. In addition, two open-

ended questions allowed remarks, comments, and sugges-

tions. Information collected included demographics, details

on medical condition and symptoms, medical treatment,

cannabis-use patterns, and methods of former and cur-

rent intake of cannabis or cannabinoids. Participants were

asked to rate their personal experience with different modes

of delivery using Likert scale-style responses. Only com-

pleted surveys were included for final evaluation.

Participants were asked to evaluate different cannabis

administration forms, including: smoking of cannabis

(Smoking); inhalation of cannabis with a vaporizer

(Vaporizer); oral use of cannabis as a tea (Tea); oral use

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 200 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

ural cannabinoid (-)-trans-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol,

usually abbreviated THC (WHO 2006). It may be extracted

from the plant, gained by isomerization of cannabidiol

(CBD), or manufactured synthetically. Marinol® is a syn-

thetic form of THC dissolved in sesame oil and prepared

in gelatin capsules, while nabilone is a synthetic ago-

nist of the human cannabinoid receptor (CB1), structurally

derived from a major human metabolite of THC. Both

products are registered for the symptomatic treatment of

nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy,

while dronabinol is also approved for treating anorexia and

cachexia related to HIV / AIDS. The patent on Marinol ®

expired in 2011, and an authorized generic version has

become available from Watson Pharmaceuticals. A generic

formulation of nabilone is now available in Canada from

Pharmascience Inc. In Germany, generic THC is supplied

by two companies (THC Pharm and Bionorica Ethics)

from which pharmacies can prepare capsules and solu-

tions (in oil or alcohol). The alcoholic solutions of THC

can either be used orally or inhaled by using a vapor-

izer (IACM 2009). About 7.5 kg of THC is delivered by

German pharmacies per year (WHO 2006).

Nabiximols (marketed as Sativex® since 2005 by

GW Pharmaceuticals, UK, and partners) is a sublingually

administered oromucosal spray based on a mixture of

two distinct standardized cannabis extracts. Its principal

active components are the plant-derived cannabinoids THC

and CBD. Sativex is currently registered in Canada, the

UK, Spain, Germany, Denmark, and New Zealand to treat

spasticity due to multiple sclerosis. In Canada, it is also

approved for the relief of neuropathic pain and advanced

cancer pain. Further approval is expected in other European

countries, based on the European Mutual Recognition

Procedure (GW Pharmaceuticals 2012).

Parallel to the development of pharmaceutical CBMs,

the number of countries providing a legal source of

medicinal-grade cannabis to chronically ill patients has

been growing as well. Canada (since 2001) and The

Netherlands (since 2003) have had government-run pro-

grams for the last decade, where quality-controlled herbal

cannabis is supplied by the specialized companies Prairie

Plant Systems Inc. and Bedrocan BV, respectively. Several

other countries are now setting up their own program

(Israel, Czech Republic) or importing products from the

Dutch program (Italy, Finland, Germany). In the US, the

number of states that introduced laws to permit the med-

ical use of cannabis has grown to 18 plus the District of

Columbia (DC), even though these state-level initiatives are

still prohibited by the federal government (IACM 2012).

In general, CBMs are used for symptomatic treat-

ment of chronic diseases refractory to standard treat-

ments. Because multiple biologically active cannabinoids

have been identified (including THC, CBD, tetrahy-

drocannabivarin (THCV) and THC-acid (THCA)), and

because CBMs can be administered in multiple ways (oral,

sublingual, inhaled), there seems to be a demand for multi-

ple cannabinoid-based therapeutic products. Nevertheless,

therapeutic effects of different CBMs have only been

directly compared in a few clinical studies. Most of these

studies compared an unregistered oral cannabis extract

(Cannador®) to Marinol ® (Zajicek 2003; 2005; Killestein

2002; Freeman 2006; Strasser 2006), while a few oth-

ers compared smoked cannabis to Marinol® (Haney 2005;

2007). The survey presented here was designed to con-

tribute to the understanding of cannabinoid-based medicine

by asking patients to compare the effects of different CBMs

and different administration forms. To the best of our

knowledge, this survey represents the largest systematic

study on actual patient experiences with cannabinoid-based

medicines currently available anywhere.

METHODOLOGY

We conducted an international, web-based, cross-

sectional survey to describe patients’ perceptions of dif-

ferent modes of administration for cannabinoid-based

medicines (complete survey available from first author).

The study was designed and conducted by the International

Association for Cannabinoid Medicines (IACM), which

has the goal to “advance knowledge on cannabis,

cannabinoids, the endocannabinoid system, and related

topics especially with regard to their therapeutic potential.”

The survey was posted on the official IACM website (http:/

/www.cannabis-med.org) from August 2009 until January

2010 in five different languages: English, French, Spanish,

German, and Dutch. To improve recruitment, the sur-

vey was brought to the attention of the approximately

5500 recipients of the IACM biweekly electronic newslet-

ter. The survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Hannover Medical School, Germany.

Subjects were a self-selected “availability sample” of

visitors to the IACM website; eligible subjects needed

to have experience with at least two different CBMs or

administration forms to be included. Participants remained

anonymous and received no financial compensation.

The survey consisted of 21 structured (fixed) ques-

tions that were answered by yes / no responses, multiple

choice lists, and rating scales. In addition, two open-

ended questions allowed remarks, comments, and sugges-

tions. Information collected included demographics, details

on medical condition and symptoms, medical treatment,

cannabis-use patterns, and methods of former and cur-

rent intake of cannabis or cannabinoids. Participants were

asked to rate their personal experience with different modes

of delivery using Likert scale-style responses. Only com-

pleted surveys were included for final evaluation.

Participants were asked to evaluate different cannabis

administration forms, including: smoking of cannabis

(Smoking); inhalation of cannabis with a vaporizer

(Vaporizer); oral use of cannabis as a tea (Tea); oral use

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 200 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

Hazekamp et al. Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

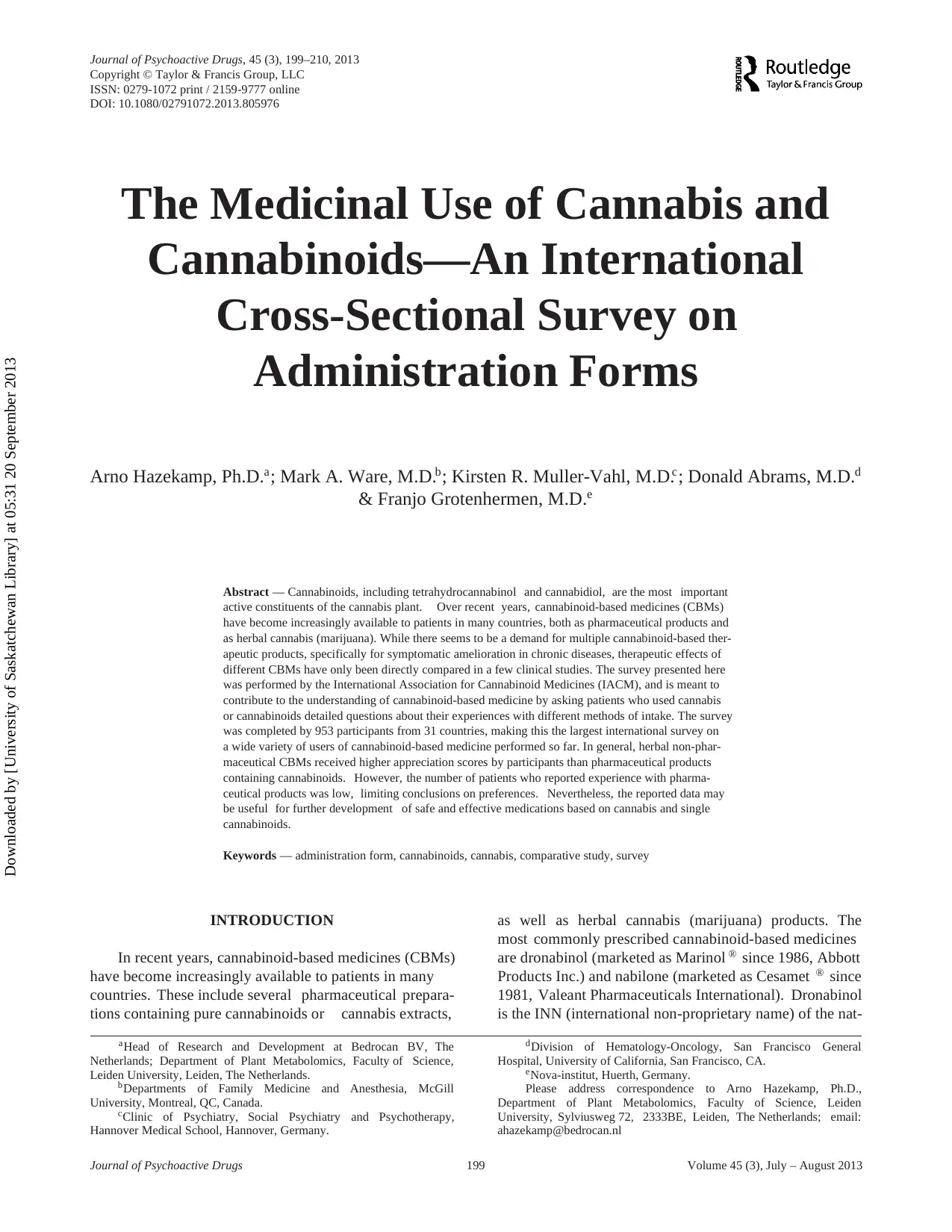

TABLE 1

(a) Methods of Ingestion Ever Tried (Multiple Answers Possible), Most Preferred Method of Intake; (B)

Expressed as Total Number of Participants; and (C) Expressed as Percentage of All Users

Smoking

Vaporizer

Tea

Food/Tinc

Dronabinol

Nabilone

THC vap

Nabiximols

Other

GROUP 1 GROUP 2 OTHER

a) Ever tried (N=) 827 450 213 571 74 14 28 7 69

b) Preference (N=) 599 225 23 75 17 1 1 4 8

c) Satisfied users (%) 72.4 50.0 10.8 13.1 23.0 7.1 3.6 57.1 11.6

GROUP 1 GROUP 2

of cannabis in baked goods/ cannabis tincture (Food/ Tinc.);

oral use of dronabinol/ Marinol® (Dronabinol); oral use of

nabilone/ Cesamet® (Nabilone); inhalation of dronabinol

with a vaporizer (THC vap.); and oromucosal administra-

tion of Sativex ® (Nabiximols). To facilitate discussion of

the results in this article, administration forms were divided

into two distinct groups: Group 1 covers herbal cannabis

(marijuana)-based products that were prepared by patients

themselves; Group 2 includes the pharmaceutical prepa-

rations with known content of cannabinoids in a defined

administration form (see Table 1). All remaining responses

were grouped under “other.” This practical classification

will be used throughout the discussion of results.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographics

The survey was completed by 953 participants, of

whom 614 (64%) were male and 339 (36%) were female.

The mean age was 40.7 years old (range 14–76) with the

following distribution: ≤20 years old (7.9%); 21–30 years

(20.1%); 31–40 years (20.7%); 41–50 years (20.8%); 51–

60 years (24.1%); 61–70 years (5.8%); >70 years (0.6%).

Participants responded from 31 countries, with the

most common nationalities represented being the USA

(38.5% of participants), Germany (16.6%), France (7.9%),

Canada (7.5%), The Netherlands (5.5%), and Spain (5.1%).

Participants from the USA were additionally asked for their

state of residence. The top five states, representing 72% of

US participants, all have medical marijuana laws (IACM

2012) and were California (36.2% of all US subjects),

Oregon (18.5%), Washington (7.6%), Michigan (3.7%),

and Colorado (3.5%). In total, participants from 40 US

states were included in the survey.

Modes of Delivery

When asked what types of inhaled or oral CBMs had

been used, subjects could score all answers that apply.

Results are shown in Table 1a. Of 953 participants, 903

(94.8%) reported having tried at least one form of inhaled

administration of CBMs, while 653 (68.5%) had experi-

ence with some form of oral or sublingual administration.

About 5% of participants indicated experience with topical

use of CBMs, which included lotions, oils, and skin creams

containing powdered cannabis or extracts.

Of the 903 individuals who indicated the use of inhaled

CBMs, 827 (91.6%) had tried smoking cannabis herb or

resin (hashish). When asked if tobacco was added when

smoking cannabis, the responses were: always 16.6%;

often 15.2%; sometimes 16.3%; never 51.8%. A distinction

between North American and European subjects became

apparent: of the 425 North American participants who used

inhaled CBMs, 52.7% never used tobacco and only 2.6%

always, while among the 410 European participants 14.1%

never used tobacco and 29.0% always did so. While the use

of tobacco is not encouraged, it may be relevant to study

whether the addition of tobacco in these cases is merely a

matter of habit or taste, or has an actual pharmacokinetic

interaction with cannabis. One study has suggested that the

co-administration of tobacco with cannabis releases rela-

tively more THC from cannabis when smoked (Van der

Kooy 2009).

As an alternative to smoking, cannabis constituents

can be inhaled by using a vaporizer, which volatizes

components such as THC, CBD, and terpenes, but with

significant reduction of pyrolytic byproducts (Hazekamp

2006). Of the 903 individuals with experience in inhal-

ing cannabinoids, 450 (49.8%) had used a vaporizer in

combination with cannabis herb or resin, while 28 had

used a vaporizer to inhale some form of pure THC (likely

dissolved in alcohol or another solvent). Although many

different types and brands of vaporizers are commer-

cially available, almost half (227) of those using a vapor-

izer had tried the Volcano ® vaporizer (Storz & Bickel

GmbH, Germany). Another 201 subjects indicated they

used another brand of vaporizer, while 30 selected the

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 201 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

TABLE 1

(a) Methods of Ingestion Ever Tried (Multiple Answers Possible), Most Preferred Method of Intake; (B)

Expressed as Total Number of Participants; and (C) Expressed as Percentage of All Users

Smoking

Vaporizer

Tea

Food/Tinc

Dronabinol

Nabilone

THC vap

Nabiximols

Other

GROUP 1 GROUP 2 OTHER

a) Ever tried (N=) 827 450 213 571 74 14 28 7 69

b) Preference (N=) 599 225 23 75 17 1 1 4 8

c) Satisfied users (%) 72.4 50.0 10.8 13.1 23.0 7.1 3.6 57.1 11.6

GROUP 1 GROUP 2

of cannabis in baked goods/ cannabis tincture (Food/ Tinc.);

oral use of dronabinol/ Marinol® (Dronabinol); oral use of

nabilone/ Cesamet® (Nabilone); inhalation of dronabinol

with a vaporizer (THC vap.); and oromucosal administra-

tion of Sativex ® (Nabiximols). To facilitate discussion of

the results in this article, administration forms were divided

into two distinct groups: Group 1 covers herbal cannabis

(marijuana)-based products that were prepared by patients

themselves; Group 2 includes the pharmaceutical prepa-

rations with known content of cannabinoids in a defined

administration form (see Table 1). All remaining responses

were grouped under “other.” This practical classification

will be used throughout the discussion of results.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographics

The survey was completed by 953 participants, of

whom 614 (64%) were male and 339 (36%) were female.

The mean age was 40.7 years old (range 14–76) with the

following distribution: ≤20 years old (7.9%); 21–30 years

(20.1%); 31–40 years (20.7%); 41–50 years (20.8%); 51–

60 years (24.1%); 61–70 years (5.8%); >70 years (0.6%).

Participants responded from 31 countries, with the

most common nationalities represented being the USA

(38.5% of participants), Germany (16.6%), France (7.9%),

Canada (7.5%), The Netherlands (5.5%), and Spain (5.1%).

Participants from the USA were additionally asked for their

state of residence. The top five states, representing 72% of

US participants, all have medical marijuana laws (IACM

2012) and were California (36.2% of all US subjects),

Oregon (18.5%), Washington (7.6%), Michigan (3.7%),

and Colorado (3.5%). In total, participants from 40 US

states were included in the survey.

Modes of Delivery

When asked what types of inhaled or oral CBMs had

been used, subjects could score all answers that apply.

Results are shown in Table 1a. Of 953 participants, 903

(94.8%) reported having tried at least one form of inhaled

administration of CBMs, while 653 (68.5%) had experi-

ence with some form of oral or sublingual administration.

About 5% of participants indicated experience with topical

use of CBMs, which included lotions, oils, and skin creams

containing powdered cannabis or extracts.

Of the 903 individuals who indicated the use of inhaled

CBMs, 827 (91.6%) had tried smoking cannabis herb or

resin (hashish). When asked if tobacco was added when

smoking cannabis, the responses were: always 16.6%;

often 15.2%; sometimes 16.3%; never 51.8%. A distinction

between North American and European subjects became

apparent: of the 425 North American participants who used

inhaled CBMs, 52.7% never used tobacco and only 2.6%

always, while among the 410 European participants 14.1%

never used tobacco and 29.0% always did so. While the use

of tobacco is not encouraged, it may be relevant to study

whether the addition of tobacco in these cases is merely a

matter of habit or taste, or has an actual pharmacokinetic

interaction with cannabis. One study has suggested that the

co-administration of tobacco with cannabis releases rela-

tively more THC from cannabis when smoked (Van der

Kooy 2009).

As an alternative to smoking, cannabis constituents

can be inhaled by using a vaporizer, which volatizes

components such as THC, CBD, and terpenes, but with

significant reduction of pyrolytic byproducts (Hazekamp

2006). Of the 903 individuals with experience in inhal-

ing cannabinoids, 450 (49.8%) had used a vaporizer in

combination with cannabis herb or resin, while 28 had

used a vaporizer to inhale some form of pure THC (likely

dissolved in alcohol or another solvent). Although many

different types and brands of vaporizers are commer-

cially available, almost half (227) of those using a vapor-

izer had tried the Volcano ® vaporizer (Storz & Bickel

GmbH, Germany). Another 201 subjects indicated they

used another brand of vaporizer, while 30 selected the

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 201 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Hazekamp et al. Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

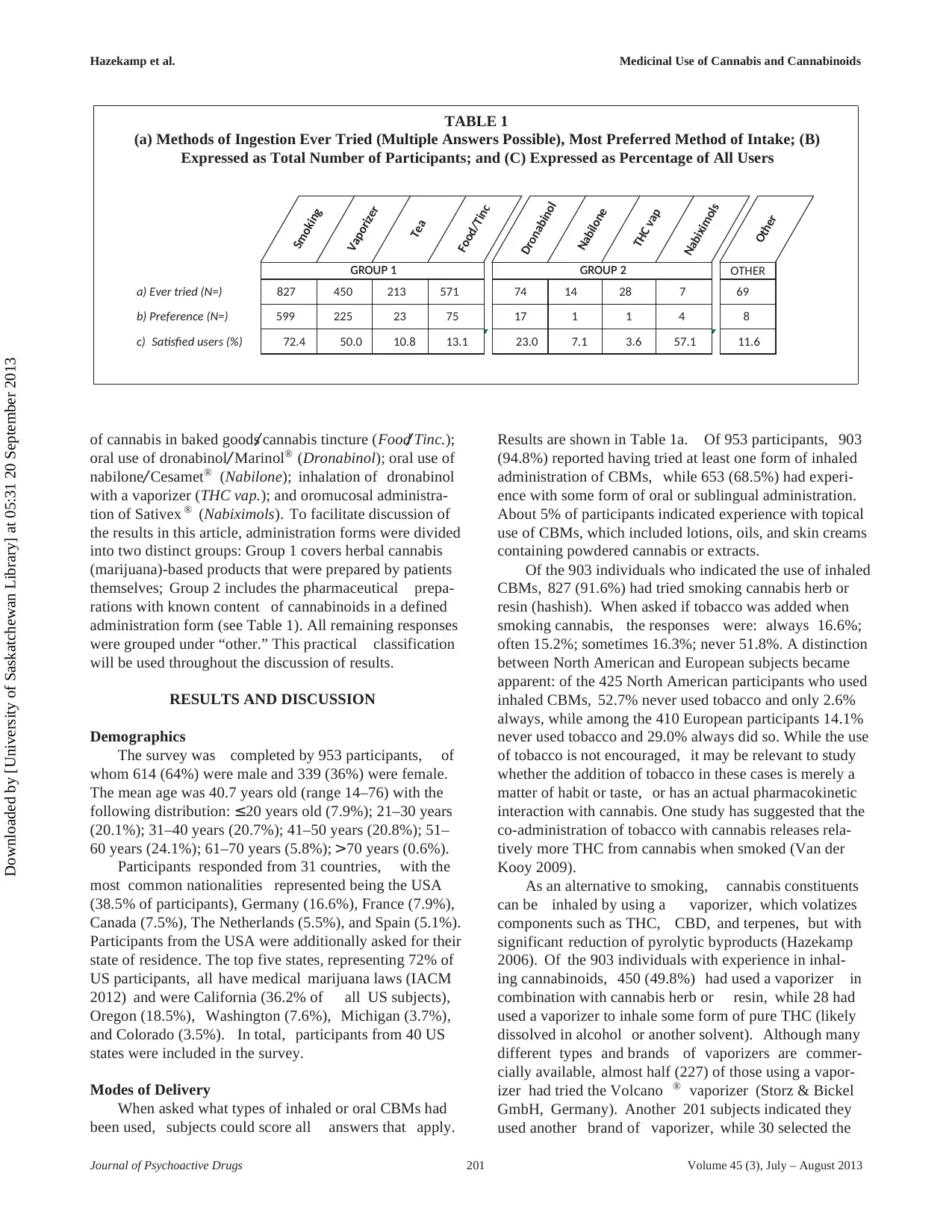

FIGURE 1

Preferred Mode of Administration for Subjects in Each of the Top 5 Symptoms

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

% of participants

chronic pain (N = 278)

anxiety (N = 175)

loss of appetite and/or

weight (N = 102)

depression (N = 50)

insomnia or sleeping

disorder (N = 49)

answer “does not apply,” which could indicate they assem-

bled their own device for vaporizing.

Of the 653 participants who indicated experience with

oral or sublingual forms of CBM, 571 subjects (87.4%)

had used herbal cannabis in foods, baked goods, or tinc-

tures. Another 231 subjects (35.4%) had used cannabis

prepared as a tea. Fewer participants had experience with

dronabinol (74; 11.3%), nabilone (14; 2.1%), or nabiximols

(7; 1.1%).

Subjects were asked which method of intake they

would prefer, if given a single choice. Preferences are

shown in Table 1b. While 97% chose an herbal CBM

(Group 1) to treat their medical condition, this may reflect

the fact that many patients have not had the opportunity

to try any of the pharmaceutical preparations covered by

the survey. We therefore compared the total number of

users of each CBM to the number of subjects who would

choose that particular CBM as their preference. The result-

ing percentage (Table 1c) may be loosely regarded as a

“satisfaction-score,” independent of the number of patients

who have actually tried each product.

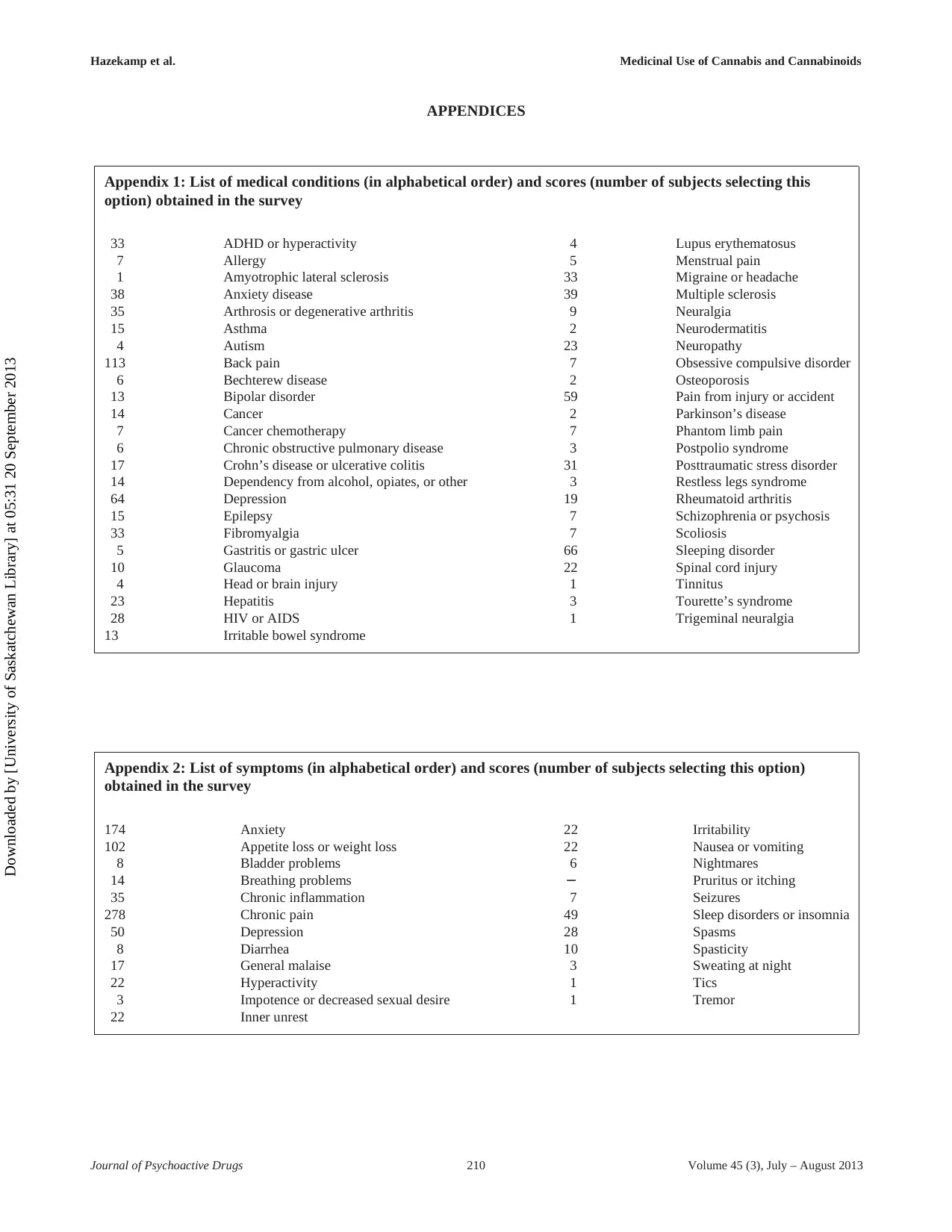

Medical Condition

Participants were asked to select from a list of 47 med-

ical conditions the main condition or disease for which

they seek symptomatic relief by using CBMs. The results,

as shown in Appendix 1, indicated that participants used

CBMs for a wide variety of medical conditions. The top

five conditions were back pain (11.9%), sleeping disorder

(6.9%), depression (6.7%), pain resulting from injury or

accident (6.2%), and multiple sclerosis (4.1%). Eighty par-

ticipants (8.4%) marked “other.” Most participants (80.4%)

indicated they were, or had been, under medical treatment

by a doctor for their particular condition.

Participants were also asked to select the main symp-

tom for which they sought relief by using CBMs from a

list of 22 options. The top five consisted of chronic pain

(29.2%), anxiety (18.3%), loss of appetite and / or weight

(10.7%), depression (5.2%), and insomnia or sleeping dis-

order (5.1%) (see Appendix 2). While chronic pain and

loss of appetite and / or weight are specifically targeted

indications of pharmaceutical products such as Marinol

and Sativex, anxiety, depression, and insomnia have not

yet been targeted as indications for pharmaceutical drug

development.

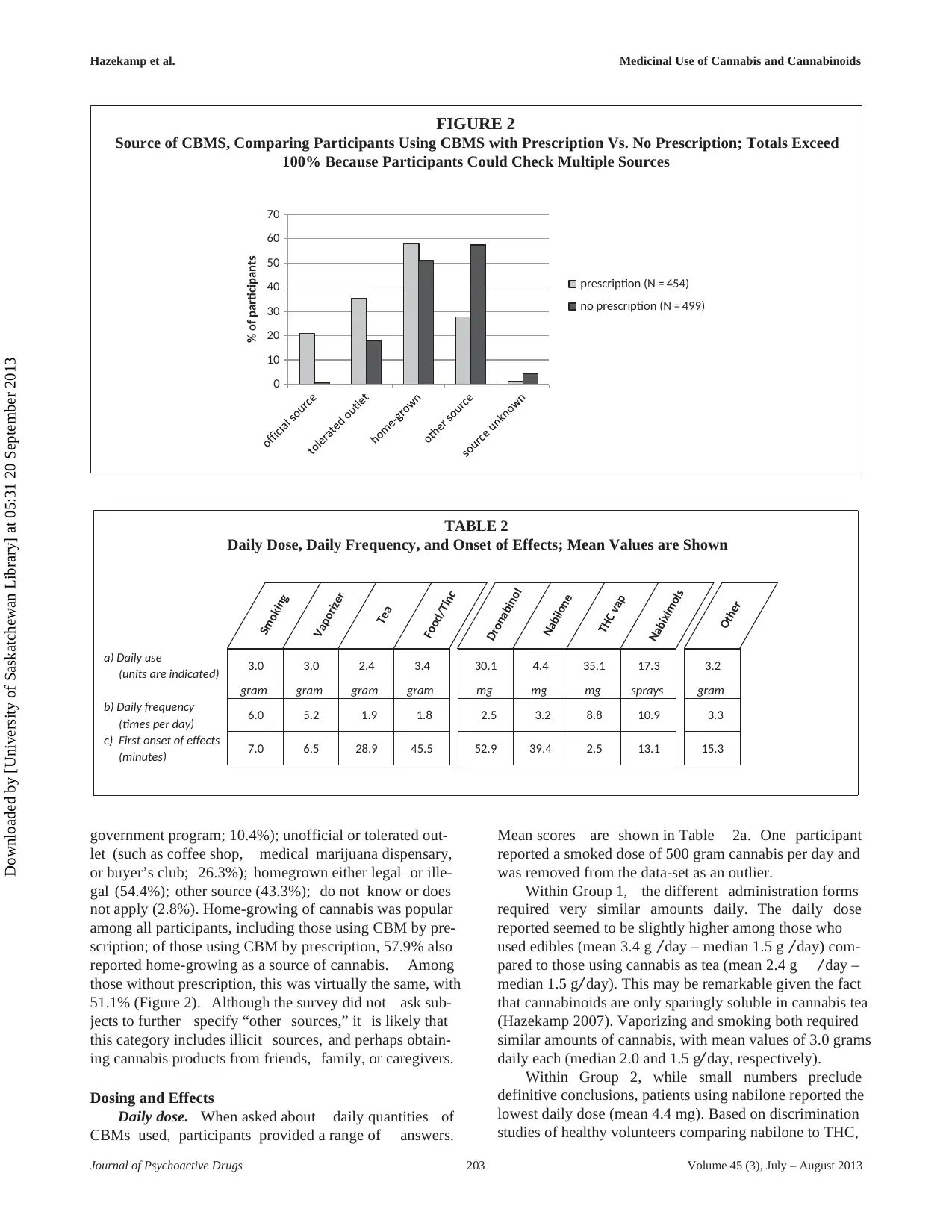

Although a variety of conditions and symptoms were

covered in this survey, we found no clear differences

between perceived symptomatic amelioration and preferred

method of intake. This is visualized in Figure 1, where the

top five symptoms represent 69% of participants.

Background of CBM Use

Of 953 participants, 87.4% were current users of

CBMs, while the remaining 12.6% had used it in the past.

Most participants (76.5%) indicated having used cannabis

products prior to the onset of their medical condition. When

asked how long CBMs had been used for medical purposes,

14.5% responded they used it less than one year, 32.8%

used it for one to five years, and 52.7% had used it for over

five years. In about half of the cases (47.6%), a medical pro-

fessional was (or had been) involved in recommending or

prescribing the therapeutic use of cannabinoids. This may

be dependent on the country of origin of participants, as

many countries do not allow the medical use of cannabis or

cannabinoids in any form, so it may be difficult for patients

to find a medical professional to be involved.

When asked where they obtained their CBMs,

participants reported official sources (such as pharmacy or

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 202 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

FIGURE 1

Preferred Mode of Administration for Subjects in Each of the Top 5 Symptoms

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

% of participants

chronic pain (N = 278)

anxiety (N = 175)

loss of appetite and/or

weight (N = 102)

depression (N = 50)

insomnia or sleeping

disorder (N = 49)

answer “does not apply,” which could indicate they assem-

bled their own device for vaporizing.

Of the 653 participants who indicated experience with

oral or sublingual forms of CBM, 571 subjects (87.4%)

had used herbal cannabis in foods, baked goods, or tinc-

tures. Another 231 subjects (35.4%) had used cannabis

prepared as a tea. Fewer participants had experience with

dronabinol (74; 11.3%), nabilone (14; 2.1%), or nabiximols

(7; 1.1%).

Subjects were asked which method of intake they

would prefer, if given a single choice. Preferences are

shown in Table 1b. While 97% chose an herbal CBM

(Group 1) to treat their medical condition, this may reflect

the fact that many patients have not had the opportunity

to try any of the pharmaceutical preparations covered by

the survey. We therefore compared the total number of

users of each CBM to the number of subjects who would

choose that particular CBM as their preference. The result-

ing percentage (Table 1c) may be loosely regarded as a

“satisfaction-score,” independent of the number of patients

who have actually tried each product.

Medical Condition

Participants were asked to select from a list of 47 med-

ical conditions the main condition or disease for which

they seek symptomatic relief by using CBMs. The results,

as shown in Appendix 1, indicated that participants used

CBMs for a wide variety of medical conditions. The top

five conditions were back pain (11.9%), sleeping disorder

(6.9%), depression (6.7%), pain resulting from injury or

accident (6.2%), and multiple sclerosis (4.1%). Eighty par-

ticipants (8.4%) marked “other.” Most participants (80.4%)

indicated they were, or had been, under medical treatment

by a doctor for their particular condition.

Participants were also asked to select the main symp-

tom for which they sought relief by using CBMs from a

list of 22 options. The top five consisted of chronic pain

(29.2%), anxiety (18.3%), loss of appetite and / or weight

(10.7%), depression (5.2%), and insomnia or sleeping dis-

order (5.1%) (see Appendix 2). While chronic pain and

loss of appetite and / or weight are specifically targeted

indications of pharmaceutical products such as Marinol

and Sativex, anxiety, depression, and insomnia have not

yet been targeted as indications for pharmaceutical drug

development.

Although a variety of conditions and symptoms were

covered in this survey, we found no clear differences

between perceived symptomatic amelioration and preferred

method of intake. This is visualized in Figure 1, where the

top five symptoms represent 69% of participants.

Background of CBM Use

Of 953 participants, 87.4% were current users of

CBMs, while the remaining 12.6% had used it in the past.

Most participants (76.5%) indicated having used cannabis

products prior to the onset of their medical condition. When

asked how long CBMs had been used for medical purposes,

14.5% responded they used it less than one year, 32.8%

used it for one to five years, and 52.7% had used it for over

five years. In about half of the cases (47.6%), a medical pro-

fessional was (or had been) involved in recommending or

prescribing the therapeutic use of cannabinoids. This may

be dependent on the country of origin of participants, as

many countries do not allow the medical use of cannabis or

cannabinoids in any form, so it may be difficult for patients

to find a medical professional to be involved.

When asked where they obtained their CBMs,

participants reported official sources (such as pharmacy or

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 202 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

Hazekamp et al. Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

FIGURE 2

Source of CBMS, Comparing Participants Using CBMS with Prescription Vs. No Prescription; Totals Exceed

100% Because Participants Could Check Multiple Sources

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

% of participants

prescription (N = 454)

no prescription (N = 499)

TABLE 2

Daily Dose, Daily Frequency, and Onset of Effects; Mean Values are Shown

Smoking

Vaporizer

Tea

Food/Tinc

Dronabinol

Nabilone

THC vap

Nabiximols

Other

a) Daily use

(units are indicated) 3.0 3.0 2.4 3.4 30.1 4.4 35.1 17.3 3.2

gram gram gram gram mg mg mg sprays gram

b) Daily frequency

(times per day) 6.0 5.2 1.9 1.8 2.5 3.2 8.8 10.9 3.3

c) First onset of effects

(minutes) 7.0 6.5 28.9 45.5 52.9 39.4 2.5 13.1 15.3

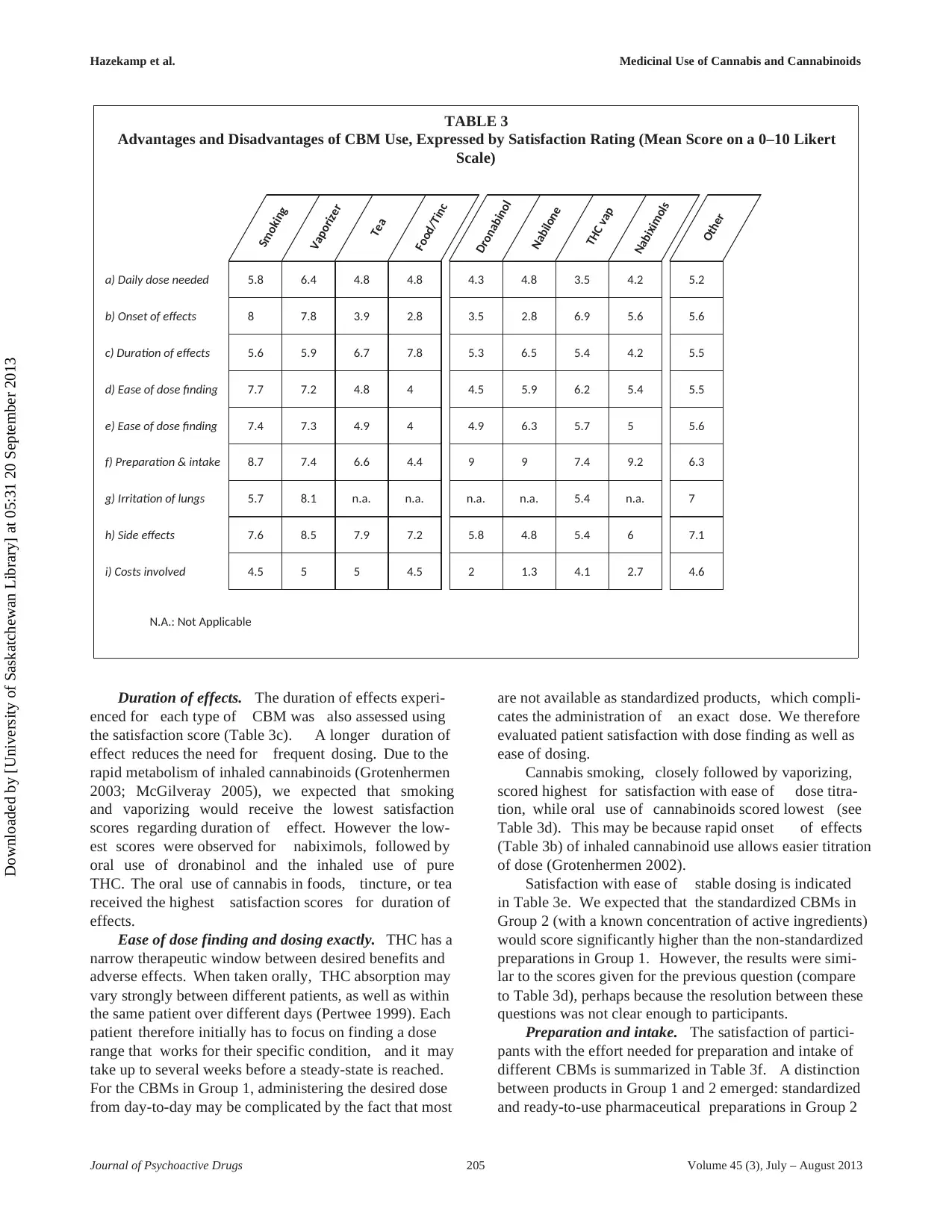

government program; 10.4%); unofficial or tolerated out-

let (such as coffee shop, medical marijuana dispensary,

or buyer’s club; 26.3%); homegrown either legal or ille-

gal (54.4%); other source (43.3%); do not know or does

not apply (2.8%). Home-growing of cannabis was popular

among all participants, including those using CBM by pre-

scription; of those using CBM by prescription, 57.9% also

reported home-growing as a source of cannabis. Among

those without prescription, this was virtually the same, with

51.1% (Figure 2). Although the survey did not ask sub-

jects to further specify “other sources,” it is likely that

this category includes illicit sources, and perhaps obtain-

ing cannabis products from friends, family, or caregivers.

Dosing and Effects

Daily dose. When asked about daily quantities of

CBMs used, participants provided a range of answers.

Mean scores are shown in Table 2a. One participant

reported a smoked dose of 500 gram cannabis per day and

was removed from the data-set as an outlier.

Within Group 1, the different administration forms

required very similar amounts daily. The daily dose

reported seemed to be slightly higher among those who

used edibles (mean 3.4 g / day – median 1.5 g / day) com-

pared to those using cannabis as tea (mean 2.4 g / day –

median 1.5 g/ day). This may be remarkable given the fact

that cannabinoids are only sparingly soluble in cannabis tea

(Hazekamp 2007). Vaporizing and smoking both required

similar amounts of cannabis, with mean values of 3.0 grams

daily each (median 2.0 and 1.5 g/ day, respectively).

Within Group 2, while small numbers preclude

definitive conclusions, patients using nabilone reported the

lowest daily dose (mean 4.4 mg). Based on discrimination

studies of healthy volunteers comparing nabilone to THC,

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 203 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

FIGURE 2

Source of CBMS, Comparing Participants Using CBMS with Prescription Vs. No Prescription; Totals Exceed

100% Because Participants Could Check Multiple Sources

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

% of participants

prescription (N = 454)

no prescription (N = 499)

TABLE 2

Daily Dose, Daily Frequency, and Onset of Effects; Mean Values are Shown

Smoking

Vaporizer

Tea

Food/Tinc

Dronabinol

Nabilone

THC vap

Nabiximols

Other

a) Daily use

(units are indicated) 3.0 3.0 2.4 3.4 30.1 4.4 35.1 17.3 3.2

gram gram gram gram mg mg mg sprays gram

b) Daily frequency

(times per day) 6.0 5.2 1.9 1.8 2.5 3.2 8.8 10.9 3.3

c) First onset of effects

(minutes) 7.0 6.5 28.9 45.5 52.9 39.4 2.5 13.1 15.3

government program; 10.4%); unofficial or tolerated out-

let (such as coffee shop, medical marijuana dispensary,

or buyer’s club; 26.3%); homegrown either legal or ille-

gal (54.4%); other source (43.3%); do not know or does

not apply (2.8%). Home-growing of cannabis was popular

among all participants, including those using CBM by pre-

scription; of those using CBM by prescription, 57.9% also

reported home-growing as a source of cannabis. Among

those without prescription, this was virtually the same, with

51.1% (Figure 2). Although the survey did not ask sub-

jects to further specify “other sources,” it is likely that

this category includes illicit sources, and perhaps obtain-

ing cannabis products from friends, family, or caregivers.

Dosing and Effects

Daily dose. When asked about daily quantities of

CBMs used, participants provided a range of answers.

Mean scores are shown in Table 2a. One participant

reported a smoked dose of 500 gram cannabis per day and

was removed from the data-set as an outlier.

Within Group 1, the different administration forms

required very similar amounts daily. The daily dose

reported seemed to be slightly higher among those who

used edibles (mean 3.4 g / day – median 1.5 g / day) com-

pared to those using cannabis as tea (mean 2.4 g / day –

median 1.5 g/ day). This may be remarkable given the fact

that cannabinoids are only sparingly soluble in cannabis tea

(Hazekamp 2007). Vaporizing and smoking both required

similar amounts of cannabis, with mean values of 3.0 grams

daily each (median 2.0 and 1.5 g/ day, respectively).

Within Group 2, while small numbers preclude

definitive conclusions, patients using nabilone reported the

lowest daily dose (mean 4.4 mg). Based on discrimination

studies of healthy volunteers comparing nabilone to THC,

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 203 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

Hazekamp et al. Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

it may be estimated that 1 mg of nabilone equals about

7-8 mg of THC (Lile 2011; Bedi 2012). For nabiximols,

when converting the number of sprays to total dose of THC

and CBD (2.7/ 2.5 mg per spray, respectively), the reported

daily dose of cannabinoids was a mean of 46 mg THC and

43 mg CBD per day.

Number of intakes. CBM preparations were further

evaluated according to the number of daily doses used

to treat the symptoms or condition of the participants.

Mean values are shown in Table 2b. Oral use of cannabis

in the form of tea, together with baked products or tinc-

ture, required the fewest intakes, with little less than two

administrations daily. Smoking and vaporizing cannabis

required a higher number of intakes, with an average of

five to six administrations daily. Oral cannabinoids are

known to have a longer, although more erratic, duration of

effect (Grotenhermen 2003; McGilveray 2005). As a result,

cannabis smokers may use more doses per day because

they are able to titrate to desired effect with multiple

smaller doses that have rapid onset. The sublingual product

nabiximols required the highest number of administrations

(mean 10.9) per day.

First onset of effects. The time needed to first onset

of effects is an important pharmacodynamic consideration

of a medicine. Together with total duration of effect, it has

a major impact on how quickly patients attain drug effi-

cacy, and therefore may influence adherence to the drug

regimen. The survey therefore asked how long it took on

average before first therapeutic effects became apparent

using the different preparations. Mean scores are shown

in Table 2c. Comparing CBMs in Group 1, subjects using

inhalation (smoking and vaporizing) reported a first effect

after about seven minutes. This is in agreement with a study

(Abrams 2007) which showed that smoking and vaporiz-

ing the same quantity of cannabis, respectively, resulted in

similar blood serum levels of THC over time. Although

tea and baked goods / tincture are both taken orally, sub-

jects using cannabis as tea reported more rapid onset of

effect (mean 29 min.) than other oral preparations (mean

46 min.). Uptake of cannabinoids can be significantly

delayed depending on the nature of the food present in

the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. For example, fatty foods can

significantly delay absorption (Grotenhermen 2002).

Subjects using vaporizers reported the onset of effects

more rapidly with pure THC (mean 2.5 min) than

herbal cannabis (mean 6.5 min). It is possible that

non-cannabinoid constituents present in the plant, such

as terpenes, delay or modulate the onset of effects of

cannabinoids (Russo 2011). Patients using nabilone or

dronabinol reported the longest time before first onset of

effect, likely due to the delay in GI absorption, resulting

in similar scores compared to cannabis taken in food or

as a tincture. Participants using nabiximols experienced

first effects after an average of 13 minutes, suggesting that

nabiximols may be absorbed (at least in part) sublingually,

speeding up the process of absorption of cannabinoids.

Advantages of Different Modes of Delivery

Subjects were asked to compare their satisfaction with

nine parameters regarding their experience using differ-

ent modes of delivery. These parameters included: dose

needed, onset of effect, duration of effect, ease of dose find-

ing, ease of exact dosing, ease of preparation and intake,

irritation of lungs (if applicable), side-effects, and cost

involved. The satisfaction rating scale ranged from 0 to 10,

with 0 representing absolutely no satisfaction and 10 rep-

resenting perfect satisfaction by the participant. A total

number of 4414 ratings were obtained. The results are

shown in Table 3.

Daily dose needed. The highest rating of dose sat-

isfaction (representing “only low dose needed”) was

obtained for inhalation of herbal cannabis with a vapor-

izer (6.4), closely followed by smoking (5.8). The inhala-

tion of pure THC, using a vaporizer, received the

lowest score. This is notable, since laboratory stud-

ies have shown pure THC to evaporate more effi-

ciently (at the same temperature) than an equivalent

amount of THC present in herbal material (Hazekamp

2006). The use of products in Group 2 (range 3.5

– 4.8) scored consistently lower in dose satisfaction

than plant-based preparations in Group 1 (range 4.8 –

6.4).

The lower scores for Group 2 may be related to the fact

that these pharmaceutical preparations are generally per-

ceived as more costly than the preparations in Group 1 (see

section on “cost” below), which may subjectively add to the

sense of needing “too much” for a single dose. It should be

noted that the dose units are different between Groups 1 and

2 (gram versus milligram), and that the herbal cannabis

mentioned in the majority of cases has no standardized or

known chemical composition.

Onset of effects. Participants were asked to rate their

satisfaction with the time needed before first (therapeutic)

effects became apparent. The faster the first onset of effects,

the higher CBMs are scored on this scale (Table 3b). Note

that this scoring system assumed that rapid onset of effect

is always more satisfactory, which may not always be the

case for chronic stable conditions.

The highest satisfaction scores for onset of action

was obtained for smoking (8.0), vaporizing of herbal

cannabis (7.8), and inhaled administration of pure THC

(6.9). Indeed, the inhaled administration of cannabinoids

is known to be the most rapid way to induce measurable

serum levels of cannabinoids (Grotenhermen 2003). The

obtained results are compatible with Table 2c, where these

three inhaled administration forms all showed first effects

in less than 10 minutes. The administration forms with low-

est scores were all oral preparations with slow GI absorp-

tion and potential first-pass effects by liver metabolism.

Nabiximols received an intermediate score, suggesting that

patients experience pharmacodynamic effects of oromu-

cosal administration of cannabinoids somewhere between

inhaled and oral administration forms.

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 204 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

it may be estimated that 1 mg of nabilone equals about

7-8 mg of THC (Lile 2011; Bedi 2012). For nabiximols,

when converting the number of sprays to total dose of THC

and CBD (2.7/ 2.5 mg per spray, respectively), the reported

daily dose of cannabinoids was a mean of 46 mg THC and

43 mg CBD per day.

Number of intakes. CBM preparations were further

evaluated according to the number of daily doses used

to treat the symptoms or condition of the participants.

Mean values are shown in Table 2b. Oral use of cannabis

in the form of tea, together with baked products or tinc-

ture, required the fewest intakes, with little less than two

administrations daily. Smoking and vaporizing cannabis

required a higher number of intakes, with an average of

five to six administrations daily. Oral cannabinoids are

known to have a longer, although more erratic, duration of

effect (Grotenhermen 2003; McGilveray 2005). As a result,

cannabis smokers may use more doses per day because

they are able to titrate to desired effect with multiple

smaller doses that have rapid onset. The sublingual product

nabiximols required the highest number of administrations

(mean 10.9) per day.

First onset of effects. The time needed to first onset

of effects is an important pharmacodynamic consideration

of a medicine. Together with total duration of effect, it has

a major impact on how quickly patients attain drug effi-

cacy, and therefore may influence adherence to the drug

regimen. The survey therefore asked how long it took on

average before first therapeutic effects became apparent

using the different preparations. Mean scores are shown

in Table 2c. Comparing CBMs in Group 1, subjects using

inhalation (smoking and vaporizing) reported a first effect

after about seven minutes. This is in agreement with a study

(Abrams 2007) which showed that smoking and vaporiz-

ing the same quantity of cannabis, respectively, resulted in

similar blood serum levels of THC over time. Although

tea and baked goods / tincture are both taken orally, sub-

jects using cannabis as tea reported more rapid onset of

effect (mean 29 min.) than other oral preparations (mean

46 min.). Uptake of cannabinoids can be significantly

delayed depending on the nature of the food present in

the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. For example, fatty foods can

significantly delay absorption (Grotenhermen 2002).

Subjects using vaporizers reported the onset of effects

more rapidly with pure THC (mean 2.5 min) than

herbal cannabis (mean 6.5 min). It is possible that

non-cannabinoid constituents present in the plant, such

as terpenes, delay or modulate the onset of effects of

cannabinoids (Russo 2011). Patients using nabilone or

dronabinol reported the longest time before first onset of

effect, likely due to the delay in GI absorption, resulting

in similar scores compared to cannabis taken in food or

as a tincture. Participants using nabiximols experienced

first effects after an average of 13 minutes, suggesting that

nabiximols may be absorbed (at least in part) sublingually,

speeding up the process of absorption of cannabinoids.

Advantages of Different Modes of Delivery

Subjects were asked to compare their satisfaction with

nine parameters regarding their experience using differ-

ent modes of delivery. These parameters included: dose

needed, onset of effect, duration of effect, ease of dose find-

ing, ease of exact dosing, ease of preparation and intake,

irritation of lungs (if applicable), side-effects, and cost

involved. The satisfaction rating scale ranged from 0 to 10,

with 0 representing absolutely no satisfaction and 10 rep-

resenting perfect satisfaction by the participant. A total

number of 4414 ratings were obtained. The results are

shown in Table 3.

Daily dose needed. The highest rating of dose sat-

isfaction (representing “only low dose needed”) was

obtained for inhalation of herbal cannabis with a vapor-

izer (6.4), closely followed by smoking (5.8). The inhala-

tion of pure THC, using a vaporizer, received the

lowest score. This is notable, since laboratory stud-

ies have shown pure THC to evaporate more effi-

ciently (at the same temperature) than an equivalent

amount of THC present in herbal material (Hazekamp

2006). The use of products in Group 2 (range 3.5

– 4.8) scored consistently lower in dose satisfaction

than plant-based preparations in Group 1 (range 4.8 –

6.4).

The lower scores for Group 2 may be related to the fact

that these pharmaceutical preparations are generally per-

ceived as more costly than the preparations in Group 1 (see

section on “cost” below), which may subjectively add to the

sense of needing “too much” for a single dose. It should be

noted that the dose units are different between Groups 1 and

2 (gram versus milligram), and that the herbal cannabis

mentioned in the majority of cases has no standardized or

known chemical composition.

Onset of effects. Participants were asked to rate their

satisfaction with the time needed before first (therapeutic)

effects became apparent. The faster the first onset of effects,

the higher CBMs are scored on this scale (Table 3b). Note

that this scoring system assumed that rapid onset of effect

is always more satisfactory, which may not always be the

case for chronic stable conditions.

The highest satisfaction scores for onset of action

was obtained for smoking (8.0), vaporizing of herbal

cannabis (7.8), and inhaled administration of pure THC

(6.9). Indeed, the inhaled administration of cannabinoids

is known to be the most rapid way to induce measurable

serum levels of cannabinoids (Grotenhermen 2003). The

obtained results are compatible with Table 2c, where these

three inhaled administration forms all showed first effects

in less than 10 minutes. The administration forms with low-

est scores were all oral preparations with slow GI absorp-

tion and potential first-pass effects by liver metabolism.

Nabiximols received an intermediate score, suggesting that

patients experience pharmacodynamic effects of oromu-

cosal administration of cannabinoids somewhere between

inhaled and oral administration forms.

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 204 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Hazekamp et al. Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

TABLE 3

Advantages and Disadvantages of CBM Use, Expressed by Satisfaction Rating (Mean Score on a 0–10 Likert

Scale)

Smoking

Vaporizer

Tea

Food/Tinc

Dronabinol

Nabilone

THC vap

Nabiximols

Other

a) Daily dose needed 5.8 6.4 4.8 4.8 4.3 4.8 3.5 4.2 5.2

b) Onset of effects 8 7.8 3.9 2.8 3.5 2.8 6.9 5.6 5.6

c) Duration of effects 5.6 5.9 6.7 7.8 5.3 6.5 5.4 4.2 5.5

d) Ease of dose finding 7.7 7.2 4.8 4 4.5 5.9 6.2 5.4 5.5

e) Ease of dose finding 7.4 7.3 4.9 4 4.9 6.3 5.7 5 5.6

f) Preparation & intake 8.7 7.4 6.6 4.4 9 9 7.4 9.2 6.3

g) Irritation of lungs 5.7 8.1 n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 5.4 n.a. 7

h) Side effects 7.6 8.5 7.9 7.2 5.8 4.8 5.4 6 7.1

i) Costs involved

N.A.: Not Applicable

4.5 5 5 4.5 2 1.3 4.1 2.7 4.6

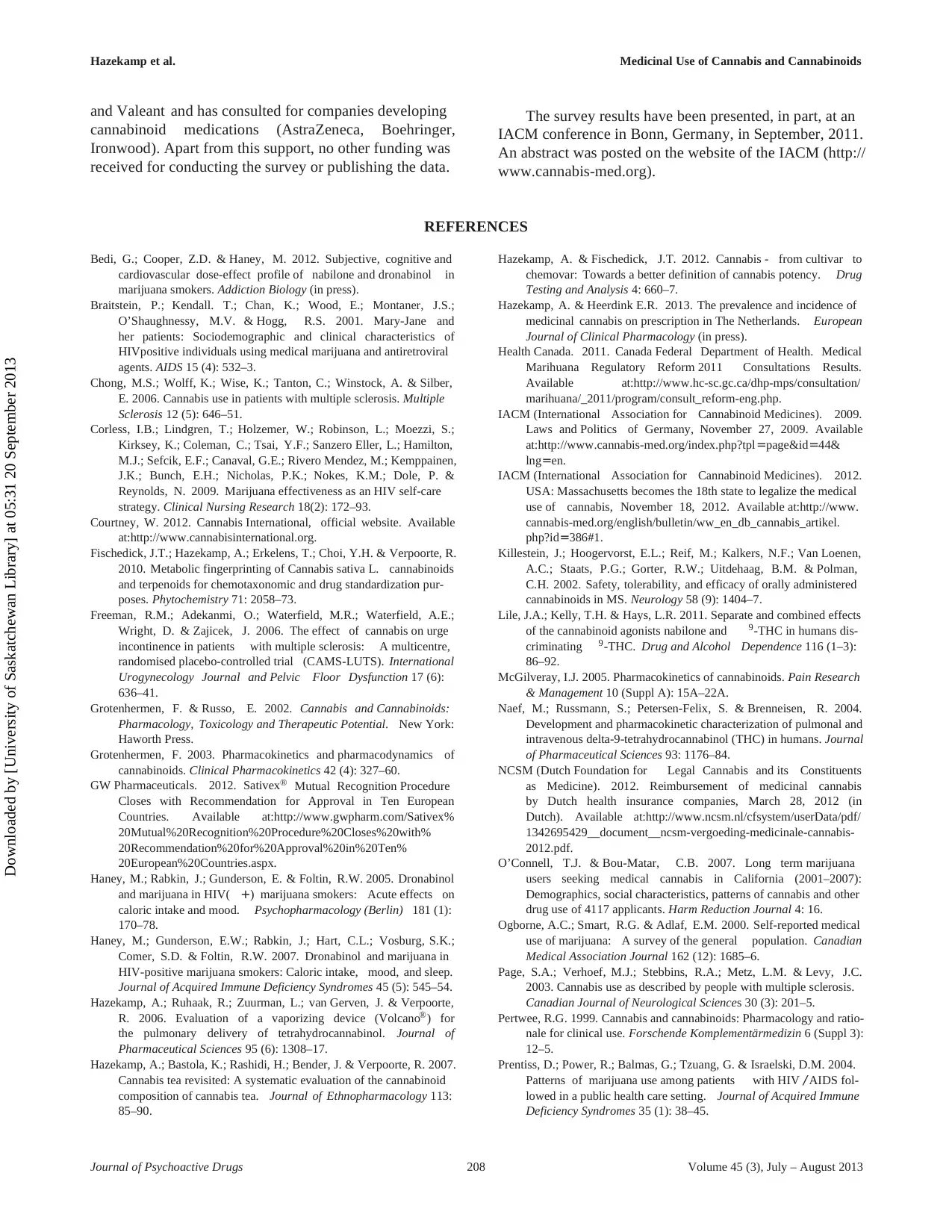

Duration of effects. The duration of effects experi-

enced for each type of CBM was also assessed using

the satisfaction score (Table 3c). A longer duration of

effect reduces the need for frequent dosing. Due to the

rapid metabolism of inhaled cannabinoids (Grotenhermen

2003; McGilveray 2005), we expected that smoking

and vaporizing would receive the lowest satisfaction

scores regarding duration of effect. However the low-

est scores were observed for nabiximols, followed by

oral use of dronabinol and the inhaled use of pure

THC. The oral use of cannabis in foods, tincture, or tea

received the highest satisfaction scores for duration of

effects.

Ease of dose finding and dosing exactly. THC has a

narrow therapeutic window between desired benefits and

adverse effects. When taken orally, THC absorption may

vary strongly between different patients, as well as within

the same patient over different days (Pertwee 1999). Each

patient therefore initially has to focus on finding a dose

range that works for their specific condition, and it may

take up to several weeks before a steady-state is reached.

For the CBMs in Group 1, administering the desired dose

from day-to-day may be complicated by the fact that most

are not available as standardized products, which compli-

cates the administration of an exact dose. We therefore

evaluated patient satisfaction with dose finding as well as

ease of dosing.

Cannabis smoking, closely followed by vaporizing,

scored highest for satisfaction with ease of dose titra-

tion, while oral use of cannabinoids scored lowest (see

Table 3d). This may be because rapid onset of effects

(Table 3b) of inhaled cannabinoid use allows easier titration

of dose (Grotenhermen 2002).

Satisfaction with ease of stable dosing is indicated

in Table 3e. We expected that the standardized CBMs in

Group 2 (with a known concentration of active ingredients)

would score significantly higher than the non-standardized

preparations in Group 1. However, the results were simi-

lar to the scores given for the previous question (compare

to Table 3d), perhaps because the resolution between these

questions was not clear enough to participants.

Preparation and intake. The satisfaction of partici-

pants with the effort needed for preparation and intake of

different CBMs is summarized in Table 3f. A distinction

between products in Group 1 and 2 emerged: standardized

and ready-to-use pharmaceutical preparations in Group 2

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 205 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

TABLE 3

Advantages and Disadvantages of CBM Use, Expressed by Satisfaction Rating (Mean Score on a 0–10 Likert

Scale)

Smoking

Vaporizer

Tea

Food/Tinc

Dronabinol

Nabilone

THC vap

Nabiximols

Other

a) Daily dose needed 5.8 6.4 4.8 4.8 4.3 4.8 3.5 4.2 5.2

b) Onset of effects 8 7.8 3.9 2.8 3.5 2.8 6.9 5.6 5.6

c) Duration of effects 5.6 5.9 6.7 7.8 5.3 6.5 5.4 4.2 5.5

d) Ease of dose finding 7.7 7.2 4.8 4 4.5 5.9 6.2 5.4 5.5

e) Ease of dose finding 7.4 7.3 4.9 4 4.9 6.3 5.7 5 5.6

f) Preparation & intake 8.7 7.4 6.6 4.4 9 9 7.4 9.2 6.3

g) Irritation of lungs 5.7 8.1 n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 5.4 n.a. 7

h) Side effects 7.6 8.5 7.9 7.2 5.8 4.8 5.4 6 7.1

i) Costs involved

N.A.: Not Applicable

4.5 5 5 4.5 2 1.3 4.1 2.7 4.6

Duration of effects. The duration of effects experi-

enced for each type of CBM was also assessed using

the satisfaction score (Table 3c). A longer duration of

effect reduces the need for frequent dosing. Due to the

rapid metabolism of inhaled cannabinoids (Grotenhermen

2003; McGilveray 2005), we expected that smoking

and vaporizing would receive the lowest satisfaction

scores regarding duration of effect. However the low-

est scores were observed for nabiximols, followed by

oral use of dronabinol and the inhaled use of pure

THC. The oral use of cannabis in foods, tincture, or tea

received the highest satisfaction scores for duration of

effects.

Ease of dose finding and dosing exactly. THC has a

narrow therapeutic window between desired benefits and

adverse effects. When taken orally, THC absorption may

vary strongly between different patients, as well as within

the same patient over different days (Pertwee 1999). Each

patient therefore initially has to focus on finding a dose

range that works for their specific condition, and it may

take up to several weeks before a steady-state is reached.

For the CBMs in Group 1, administering the desired dose

from day-to-day may be complicated by the fact that most

are not available as standardized products, which compli-

cates the administration of an exact dose. We therefore

evaluated patient satisfaction with dose finding as well as

ease of dosing.

Cannabis smoking, closely followed by vaporizing,

scored highest for satisfaction with ease of dose titra-

tion, while oral use of cannabinoids scored lowest (see

Table 3d). This may be because rapid onset of effects

(Table 3b) of inhaled cannabinoid use allows easier titration

of dose (Grotenhermen 2002).

Satisfaction with ease of stable dosing is indicated

in Table 3e. We expected that the standardized CBMs in

Group 2 (with a known concentration of active ingredients)

would score significantly higher than the non-standardized

preparations in Group 1. However, the results were simi-

lar to the scores given for the previous question (compare

to Table 3d), perhaps because the resolution between these

questions was not clear enough to participants.

Preparation and intake. The satisfaction of partici-

pants with the effort needed for preparation and intake of

different CBMs is summarized in Table 3f. A distinction

between products in Group 1 and 2 emerged: standardized

and ready-to-use pharmaceutical preparations in Group 2

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 205 Volume 45 (3), July – August 2013

Downloaded by [University of Saskatchewan Library] at 05:31 20 September 2013

Hazekamp et al. Medicinal Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

scored generally higher than the herbal cannabis-based

preparations in Group 1. One notable exception is the

smoked use of cannabis, which receives a high score.

A possible reason may be that most participants had pre-

vious experience with smoking cannabis, before as well as

during onset of their illness. It is likely that those partic-

ipants are familiar with preparing cannabis cigarettes and

therefore do not find it bothersome to do so when they get

ill. It is also possible that participants conveniently used a

pipe or bong to inhale herbal cannabis (not evaluated in this

study). The low score for baked products or tincture may be

due to the extended time needed to prepare such products.

With baked products specifically, limited shelf-life stability

may also play a role.

Irritation of the lungs. Satisfaction with lung irri-

tation (Table 3g; low scores suggest more irritation) is

only relevant for inhaled preparations. While smoking and

vaporizing herbal cannabis received similar scores in previ-

ous questions, the advantage of vaporizing (score 8.1) over

smoking (score 5.7) now becomes more obvious. This

advantage was not recognized for using the vaporizer with

pure THC, which scored similar to smoking. Although

pyrolytic by-products of combustion may be responsible

for pulmonary irritation, it seems that THC alone is also

capable of this (Tashkin 1977; Naef 2004). Higher satisfac-

tion with vaporized cannabis compared to THC alone may

be due to the presence of non-THC constituents, including

anti-inflammatory terpenes that protect the lungs from irri-

tation (Russo 2011). Another potential cause of irritation

from pure THC preparations may be the presence of resid-

ual solvents (e.g., ethanol) that are needed to solubilize the

sticky pure THC (Žuškin 1981).

Side-effects. Participants were asked to rate their

satisfaction with side-effects experienced with the different

CBMs (Table 3h). Unfortunately, the survey did not ask

more explicitly what side-effects were experienced, as

this could have added significantly to our understanding

of CBMs in a large population. Here, more than for any

other parameter that we assessed, the differences between

preparations in Group 1 and 2 were very distinct. The

herbal cannabis-based products received mean scores in

the range of 7.2 – 8.5 (meaning high overall satisfaction

with side-effect profiles), while the pharmaceutical prepa-

rations scored notably lower with a range of 4.8 – 6.0.

The major reason for this may be that the majority of

herbal cannabis users (76%) admitted to using cannabis

products before onset of their condition, potentially giving

them more experience with these CBMs and, hence, with

their potential side-effects. The lowest satisfaction with

side-effects was reported with the use of nabilone, even

though the average daily dose of nabilone reported by

subjects (4.4 mg; Table 2) was well below the maximum

of 3 mg twice daily suggested by the product monograph.

Vaporizing cannabis had the highest side-effect satisfaction

score (score 8.5), which was higher than that reported for

smoking (score 7.6).

Costs involved. For chronically ill patients, disabil-

ity and unemployment render “cost” to be an important

factor in CBM use. Overall, low satisfaction ratings were

observed for all products (highest mean score was 5.0; see

Table 3i), suggesting that the cost of using CBMs is a major

issue for patients everywhere.

Open Questions

In order to assess what the perfect CBM would look

like, if participants could develop their own product, the

survey concluded with two open-ended questions. A total

of 375 suggestions were obtained (39.3% response).

A tincture based on whole cannabis was found to be

the most popular choice for a new product to be developed,

mainly because it can be used in a multitude of ways: as

oral drops, in baking and tea, and for vaporizing as well

as smoking. According to participants, this allows for max-

imal flexibility of using cannabinoids throughout the day.

Furthermore, a tincture can be used discretely in public