Analyzing Cannabis Legalization Proposals: A Canadian Critique

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/14

|6

|8397

|500

Literature Review

AI Summary

This paper presents a critical review of cannabis legalization proposals in Canada, focusing on an editorial that advocates for legalization with strict controls. It challenges claims made in favor of legalization, particularly regarding the elimination of prohibition-related harms and the effectiveness of regulatory controls. The critique argues that evidence supporting these claims is weak and that early experiences in other jurisdictions suggest increased cannabis use among adolescents. It questions the suitability of alcohol regulation as a model for cannabis control and emphasizes the need for comprehensive knowledge about the individual and social consequences of both drug use and control measures. The review suggests decriminalization as a more appropriate initial step until sufficient knowledge is acquired to make informed decisions about legalization.

Commentary

A critique of cannabis legalization proposals in Canada

[3_TD$DIFF]Harold [6_TD$DIFF]Kalant

Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology,University of Toronto Medical Sciences Building,1 King’s College Circle Toronto,ON, Canada M5S 1A8

Introduction

The editorial by Cre´pault, Rehm & Fischer (p.1 of this issue)

provides a detailed description of the origins and rationale of a

CAMH document entitled Cannabis Policy Framework (Cre´pault,

2014),referred to below as the CPF.As described in the editorial,

the CPF concluded with a recommendation for legalization of non-

medical use of cannabis,with reliance on strict application of

regulations to prevent access to cannabis by underage users who

are most vulnerable to its adverse effects on health and social

functioning. As the editorial explains, the CPF grew out of an earlier

document from the Addiction Research Foundation (ARF)that

called for a public health approach to cannabis policy and for

decriminalization of possession for personal use (Addiction

Research Foundation, 1997). This recommendation was also made

in the LeDain Commission Report (Canadian Government,1972),

and was maintained in CAMH statements that preceded the CPF. It

is therefore useful to examine the reasons that led to the changed

recommendation in the CPF and other recent similar publications

(Haden & Emerson,2014; Spithoff,Emerson,& Spithoff,2015).

Among the important considerations mentioned in the editorial

are the following:

social harms caused by prohibition, and by its inequitable

application,

the relative modesty of the health harms attributable to cannabis

use in the majority of users,

costliness and ineffectiveness of prohibition,combined with its

deterrence of public health measures aimed at prevention and

treatment of drug-induced harm,

superior ability of legalization to prevent harm to vulnerable

groups by the use of regulatory controls that cannot be

implemented under decriminalization,

the risk that decriminalization could actually encourage the

production and distribution of cannabis.

International Journal of Drug Policy 34 (2016) 5–10

A R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:

Received 11 November 2015

Received in revised form 27 April 2016

Accepted 9 May 2016

Keywords:

Cannabis policy

Legalization

Decriminalization

Harms caused by prohibition

Harms to adolescent users

Cost-benefit assessment

A B S T R A C T

An editorial in this issue describes a cannabis policy framework document issued by a major Canadian

research centre,calling for legalization of non-medical use under strict controls to prevent increase in

use, especially by adolescents and young adults who are most vulnerable to adverse effects of cannabis

claims that such a system would eliminate the severe personal, social and monetary costs of prohibition

diminish the illicit market, and provide more humane management of cannabis use disorders. It claims

that experience with regulation of alcohol and tobacco will enable a system based on public health

principles to control access of youth to cannabis without the harm caused by prohibition.

The present critique argues that the claims made against decriminalization and for legalization are

unsupported,or even contradicted,by solid evidence.Early experience in other jurisdictions suggests

that legalization increases use by adolescents and its attendant harms. Regulation of alcohol use does n

provide a good model for cannabis controls because there is widespread alcohol use and harm among

adolescents and young adults.Government monopolies of alcoholsale have been used primarily as

sources of revenue rather than for guarding public health, and no reason has been offered to believe the

would act differently with respect to cannabis.

Good policy decisions require extensive unbiased information about the individual and social benefits

and costs of both drug use and proposed control measures, and value judgments about the benefit/harm

balance of each option. Important parts of the necessary knowledge about cannabis are not yet availabl

so that the value judgments are not yet possible. Therefore,a better case can be made for eliminating

some of the harms of prohibition by decriminalization of cannabis possession and deferring decision

about legalization until the necessary knowledge has been acquired.

ß 2016 Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

E-mail address: harold.kalant@utoronto.ca.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Drug Policy

j o u r n a lh o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / d r u g p o

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.05.002

0955-3959/ß 2016 Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

A critique of cannabis legalization proposals in Canada

[3_TD$DIFF]Harold [6_TD$DIFF]Kalant

Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology,University of Toronto Medical Sciences Building,1 King’s College Circle Toronto,ON, Canada M5S 1A8

Introduction

The editorial by Cre´pault, Rehm & Fischer (p.1 of this issue)

provides a detailed description of the origins and rationale of a

CAMH document entitled Cannabis Policy Framework (Cre´pault,

2014),referred to below as the CPF.As described in the editorial,

the CPF concluded with a recommendation for legalization of non-

medical use of cannabis,with reliance on strict application of

regulations to prevent access to cannabis by underage users who

are most vulnerable to its adverse effects on health and social

functioning. As the editorial explains, the CPF grew out of an earlier

document from the Addiction Research Foundation (ARF)that

called for a public health approach to cannabis policy and for

decriminalization of possession for personal use (Addiction

Research Foundation, 1997). This recommendation was also made

in the LeDain Commission Report (Canadian Government,1972),

and was maintained in CAMH statements that preceded the CPF. It

is therefore useful to examine the reasons that led to the changed

recommendation in the CPF and other recent similar publications

(Haden & Emerson,2014; Spithoff,Emerson,& Spithoff,2015).

Among the important considerations mentioned in the editorial

are the following:

social harms caused by prohibition, and by its inequitable

application,

the relative modesty of the health harms attributable to cannabis

use in the majority of users,

costliness and ineffectiveness of prohibition,combined with its

deterrence of public health measures aimed at prevention and

treatment of drug-induced harm,

superior ability of legalization to prevent harm to vulnerable

groups by the use of regulatory controls that cannot be

implemented under decriminalization,

the risk that decriminalization could actually encourage the

production and distribution of cannabis.

International Journal of Drug Policy 34 (2016) 5–10

A R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:

Received 11 November 2015

Received in revised form 27 April 2016

Accepted 9 May 2016

Keywords:

Cannabis policy

Legalization

Decriminalization

Harms caused by prohibition

Harms to adolescent users

Cost-benefit assessment

A B S T R A C T

An editorial in this issue describes a cannabis policy framework document issued by a major Canadian

research centre,calling for legalization of non-medical use under strict controls to prevent increase in

use, especially by adolescents and young adults who are most vulnerable to adverse effects of cannabis

claims that such a system would eliminate the severe personal, social and monetary costs of prohibition

diminish the illicit market, and provide more humane management of cannabis use disorders. It claims

that experience with regulation of alcohol and tobacco will enable a system based on public health

principles to control access of youth to cannabis without the harm caused by prohibition.

The present critique argues that the claims made against decriminalization and for legalization are

unsupported,or even contradicted,by solid evidence.Early experience in other jurisdictions suggests

that legalization increases use by adolescents and its attendant harms. Regulation of alcohol use does n

provide a good model for cannabis controls because there is widespread alcohol use and harm among

adolescents and young adults.Government monopolies of alcoholsale have been used primarily as

sources of revenue rather than for guarding public health, and no reason has been offered to believe the

would act differently with respect to cannabis.

Good policy decisions require extensive unbiased information about the individual and social benefits

and costs of both drug use and proposed control measures, and value judgments about the benefit/harm

balance of each option. Important parts of the necessary knowledge about cannabis are not yet availabl

so that the value judgments are not yet possible. Therefore,a better case can be made for eliminating

some of the harms of prohibition by decriminalization of cannabis possession and deferring decision

about legalization until the necessary knowledge has been acquired.

ß 2016 Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

E-mail address: harold.kalant@utoronto.ca.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Drug Policy

j o u r n a lh o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / d r u g p o

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.05.002

0955-3959/ß 2016 Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The validity of the model proposed in the CPF and reproduced

verbatim in the editorial can be assessed by examining the

available evidence concerning these and some related issues.

Is prohibition ineffective or a failure?

Prohibition has indeed failed to prevent all use of the drug, but

this is not a reasonable expectation.No prohibition, whether of

something as minor as smoking too close to a hospital entrance, as

common as exceeding speed limits,or as grave as murder, is

expected to be 100% effective. All one can reasonably expect from

prohibition of any undesirable behavior is that it asserts society’s

disapproval,and makes the disapproved behavior substantially

less frequent than it would otherwise be.

Prohibition of alcohol in North America in the 1920s and early

1930s did markedly reduce consumption and public intoxication

(Dills, Jacobson,& Miron, 2005) as well as the death rate from

alcoholic cirrhosis (Dills & Miron, 2004). However, it also had

various socially harmful consequences such as the growth of

bootlegging and organized crime,corruption of police forces,loss

of employment in alcohol-related industries and loss of important

tax revenues (Blocker,2006). It deprived millions of moderate

drinkers of what was for most of them a harmless pleasure,and

possibly of alleged health benefits of moderate consumption

(Kalant & Poikolainen, 1999). Therefore, prohibition did work, but

at the cost of important social harms. One must make a value

judgment as to whether the costs to society outweighed the

benefits,but that is not the same as saying that prohibition was

ineffective.

Neither can one say that cannabis prohibition is ineffective if

use is significantly less than it would be under legalization.The

percentage ofpast-year users ofcannabis among the Canadian

general population in 2012 was only 10% while that of the legal

drug alcohol was 78% (Health Canada, 2014). A recent study found

that 10% of US high school students who had not yet used

marijuana intended to use it if it became legal,and 18% of those

who had already used it declared intention to use more frequently

(Palamar, Ompad, & Petkova, 2014). These probably represent

minimum increases, because when the more decisive users

increase consumption,their attitudes and behaviors affect other

members of their peer groups to act similarly (Keyes et al.,2011;

Salvy,Pedersen,Miles, Tucker,& D’Amico,2014).

Greater permissiveness in the United States has been accom-

panied by a doubling of rates of use and of use disorders from

2002 to 2012 (Hasin et al.,2015).American states that adopted

very poorly controlled medical marijuana laws (MML) tantamount

to legalization had higher rates of marijuana use, abuse and

dependence than states without such laws,even among adoles-

cents who were not eligible for medical permits (Cerda`, Wall,

Keyes, Galea, & Hasin, 2012; Wall et al., 2011). ‘‘Medical’’

marijuana was deviated to illicit use in non-MML states

(Thurstone, Lieberman, & Schmiege, 2011), a risk that also applies

to legalization in Colorado (RMHIDTA,2015). In contrast, Choo

et al. (2014) did not find increased use by adolescents in states

adopting MML, and Masten and Guenzburger (2014) found that

some MML states experienced a significant increase in cannabis-

related traffic fatalities while other MML states did not.Until the

difference between the results of these studies can be explained, it

is unwarranted to argue that we know how to prevent increased

use after legalization.

Preliminary evidence to date indicates that in Colorado

cannabis use among 12 17, 18 25, and over-26 age groups

increased by between 17% and 63% in the 2 years after legalization

compared to the 2 years before,while national averages for the

same groups were either unchanged or lower (RMHIDTA,2016).

We will not know for some years yet whether the increases were

temporary or permanent, nor the resulting social costs in terms of

school and work performance, physical and mental health,

automobile accidents and deaths,etc. Without such knowledge,

there is no factual basis for saying that legalization is a better policy

for society than prohibition or decriminalization. Legalization is in

harmony with the democratic ideal of restricting individual liberty

of action only when necessary for the common good,but judging

what constitutes the common good requires comprehensive

knowledge of the consequences of each policy option,which we

do not yet have.

Does cannabis prohibition impose serious personal harms on

society that would be removed by legalization?

The editorial refers only briefly to the social harms caused by

prohibition of cannabis,but the CPF states that ‘‘Around 60,000

Canadians are arrested for simple possession ofcannabis every

year’’. The figure is based on data from Statistics Canada

(2014).This statement,combined with the CPF reference to only

the maximum possible sentences provided for in the law, gives the

impression that large numbers of Canadians suffer severe penalties

every year for simple possession of cannabis under the present

prohibition. However, Statistics Canada records all cannabis

incident reports by the police in each province, regardless of

whether cannabis possession is the principal object of the incident

or only a minor accompaniment to other more serious charges, and

the statistics give no indication of the outcomes.

In contrast,Pauls, Plecas,Cohen,& Haarhoff (2012),with the

help of the RCMP, had access to the complete files (names

removed) of all case reports in British Columbia over a 3-year

period and were able to separate them into subgroups according to

the nature of the charges and the outcomes. The results present a

dramatically different picture from that implied by the CPF.In

2011, of 22,561 files coded for marijuana possession in British

Columbia, 4,355 were dropped because of insufficient evidence. Of

the 18,206 cases in which possession was demonstrated, the great

majority were let off without being charged, e.g. with a warning or

simply a decision not to proceed. In 4,257 cases charges were laid,

but in most cases the possession charge was a minor addition to

charges of more serious crimes such as trafficking, violence,

impaired driving or others.Of the 249 charged only with simple

possession, one-third had the charges dropped and did not come to

trial. Of those that came to trial, only 42 were convicted, the others

being acquitted, discharged, or directed to treatment. Finally, only

seven of those convicted were sentenced to jail for 114 days, and

these were all repeat offenders with long criminal histories. Very

similar proportions of outcomes were found in each of 2009,

2010 and 2011. It is clear, therefore, that in British Columbia very

few people accused only of simple possession of marijuana actually

come to trial, and extremely few are convicted and fined or jailed.

Correspondingly detailed figures forOntario and for all of

Canada are not available. However, in Ontario in 2013 there were

17,641 reported incidents of cannabis possession; of these 8,045

were cleared without charges, 8,706 led to charges, and 890 were

not yet cleared (CANSIM, 2013). Among detained youth,1,281

were charged whereas 3,804 youths were released without

charges.Generally,similar figures were found for Canada as a

whole (Boyce, 2013). These figures are proportionally very

different from those prevalent in the United States, though federal

law in both countries prohibits non-medical use of cannabis.The

difference demonstrates that the manner of enforcement,rather

than prohibition per se,determines the magnitude of the social

cost. The foregoing discussion does not in any way deny the

seriousness of arrests and criminal records for simple possession of

cannabis,but in the weighing of costs and benefits of different

policy options,the size of the problem matters.There is a clear

H. Kalant / International Journal of Drug Policy 34 (2016) 5–106

verbatim in the editorial can be assessed by examining the

available evidence concerning these and some related issues.

Is prohibition ineffective or a failure?

Prohibition has indeed failed to prevent all use of the drug, but

this is not a reasonable expectation.No prohibition, whether of

something as minor as smoking too close to a hospital entrance, as

common as exceeding speed limits,or as grave as murder, is

expected to be 100% effective. All one can reasonably expect from

prohibition of any undesirable behavior is that it asserts society’s

disapproval,and makes the disapproved behavior substantially

less frequent than it would otherwise be.

Prohibition of alcohol in North America in the 1920s and early

1930s did markedly reduce consumption and public intoxication

(Dills, Jacobson,& Miron, 2005) as well as the death rate from

alcoholic cirrhosis (Dills & Miron, 2004). However, it also had

various socially harmful consequences such as the growth of

bootlegging and organized crime,corruption of police forces,loss

of employment in alcohol-related industries and loss of important

tax revenues (Blocker,2006). It deprived millions of moderate

drinkers of what was for most of them a harmless pleasure,and

possibly of alleged health benefits of moderate consumption

(Kalant & Poikolainen, 1999). Therefore, prohibition did work, but

at the cost of important social harms. One must make a value

judgment as to whether the costs to society outweighed the

benefits,but that is not the same as saying that prohibition was

ineffective.

Neither can one say that cannabis prohibition is ineffective if

use is significantly less than it would be under legalization.The

percentage ofpast-year users ofcannabis among the Canadian

general population in 2012 was only 10% while that of the legal

drug alcohol was 78% (Health Canada, 2014). A recent study found

that 10% of US high school students who had not yet used

marijuana intended to use it if it became legal,and 18% of those

who had already used it declared intention to use more frequently

(Palamar, Ompad, & Petkova, 2014). These probably represent

minimum increases, because when the more decisive users

increase consumption,their attitudes and behaviors affect other

members of their peer groups to act similarly (Keyes et al.,2011;

Salvy,Pedersen,Miles, Tucker,& D’Amico,2014).

Greater permissiveness in the United States has been accom-

panied by a doubling of rates of use and of use disorders from

2002 to 2012 (Hasin et al.,2015).American states that adopted

very poorly controlled medical marijuana laws (MML) tantamount

to legalization had higher rates of marijuana use, abuse and

dependence than states without such laws,even among adoles-

cents who were not eligible for medical permits (Cerda`, Wall,

Keyes, Galea, & Hasin, 2012; Wall et al., 2011). ‘‘Medical’’

marijuana was deviated to illicit use in non-MML states

(Thurstone, Lieberman, & Schmiege, 2011), a risk that also applies

to legalization in Colorado (RMHIDTA,2015). In contrast, Choo

et al. (2014) did not find increased use by adolescents in states

adopting MML, and Masten and Guenzburger (2014) found that

some MML states experienced a significant increase in cannabis-

related traffic fatalities while other MML states did not.Until the

difference between the results of these studies can be explained, it

is unwarranted to argue that we know how to prevent increased

use after legalization.

Preliminary evidence to date indicates that in Colorado

cannabis use among 12 17, 18 25, and over-26 age groups

increased by between 17% and 63% in the 2 years after legalization

compared to the 2 years before,while national averages for the

same groups were either unchanged or lower (RMHIDTA,2016).

We will not know for some years yet whether the increases were

temporary or permanent, nor the resulting social costs in terms of

school and work performance, physical and mental health,

automobile accidents and deaths,etc. Without such knowledge,

there is no factual basis for saying that legalization is a better policy

for society than prohibition or decriminalization. Legalization is in

harmony with the democratic ideal of restricting individual liberty

of action only when necessary for the common good,but judging

what constitutes the common good requires comprehensive

knowledge of the consequences of each policy option,which we

do not yet have.

Does cannabis prohibition impose serious personal harms on

society that would be removed by legalization?

The editorial refers only briefly to the social harms caused by

prohibition of cannabis,but the CPF states that ‘‘Around 60,000

Canadians are arrested for simple possession ofcannabis every

year’’. The figure is based on data from Statistics Canada

(2014).This statement,combined with the CPF reference to only

the maximum possible sentences provided for in the law, gives the

impression that large numbers of Canadians suffer severe penalties

every year for simple possession of cannabis under the present

prohibition. However, Statistics Canada records all cannabis

incident reports by the police in each province, regardless of

whether cannabis possession is the principal object of the incident

or only a minor accompaniment to other more serious charges, and

the statistics give no indication of the outcomes.

In contrast,Pauls, Plecas,Cohen,& Haarhoff (2012),with the

help of the RCMP, had access to the complete files (names

removed) of all case reports in British Columbia over a 3-year

period and were able to separate them into subgroups according to

the nature of the charges and the outcomes. The results present a

dramatically different picture from that implied by the CPF.In

2011, of 22,561 files coded for marijuana possession in British

Columbia, 4,355 were dropped because of insufficient evidence. Of

the 18,206 cases in which possession was demonstrated, the great

majority were let off without being charged, e.g. with a warning or

simply a decision not to proceed. In 4,257 cases charges were laid,

but in most cases the possession charge was a minor addition to

charges of more serious crimes such as trafficking, violence,

impaired driving or others.Of the 249 charged only with simple

possession, one-third had the charges dropped and did not come to

trial. Of those that came to trial, only 42 were convicted, the others

being acquitted, discharged, or directed to treatment. Finally, only

seven of those convicted were sentenced to jail for 114 days, and

these were all repeat offenders with long criminal histories. Very

similar proportions of outcomes were found in each of 2009,

2010 and 2011. It is clear, therefore, that in British Columbia very

few people accused only of simple possession of marijuana actually

come to trial, and extremely few are convicted and fined or jailed.

Correspondingly detailed figures forOntario and for all of

Canada are not available. However, in Ontario in 2013 there were

17,641 reported incidents of cannabis possession; of these 8,045

were cleared without charges, 8,706 led to charges, and 890 were

not yet cleared (CANSIM, 2013). Among detained youth,1,281

were charged whereas 3,804 youths were released without

charges.Generally,similar figures were found for Canada as a

whole (Boyce, 2013). These figures are proportionally very

different from those prevalent in the United States, though federal

law in both countries prohibits non-medical use of cannabis.The

difference demonstrates that the manner of enforcement,rather

than prohibition per se,determines the magnitude of the social

cost. The foregoing discussion does not in any way deny the

seriousness of arrests and criminal records for simple possession of

cannabis,but in the weighing of costs and benefits of different

policy options,the size of the problem matters.There is a clear

H. Kalant / International Journal of Drug Policy 34 (2016) 5–106

need for full and accurate nationwide information,which we do

not yet have.

Statistics Canada does indicate that over 699,000 Canadians

have criminal records as a result of convictions on charges of

cannabis possession, many of which occurred decades ago during

their adolescence before the Youth Criminal Justice Act came into

effect. This is certainly an important harmful effect of prohibition

of cannabis possession, and either legalization or decriminalization

would prevent it from happening in the future.However,neither

would undo the harm to those who already have criminal records.

A legislated amnesty would be required, but this could be done in

connection with decriminalization or even with continued

prohibition,and is not necessarily linked to legalization.

As in the United States, some Canadian provinces show greater

severity of application of cannabis prohibition than others.That

could just as logically call for federal government action to impose

uniform moderate sentencing rules across the country as for

legalization of cannabis use.

Does prohibition of cannabis impede the application of

measures to reduce drug-related harm to health?

The editorial’s statement to this effect is more cautious than the

CPF statement that ‘‘The law enforcement focus ofprohibition

drives cannabis users away from prevention,risk reduction and

treatment services’’,for which it cites no supporting literature. In

fact, prohibition of cannabis possession is not necessarily in

conflict with treatment of dependent persons.Diversion of cases

from the justice to the health care system has been occurring with

increasing frequency in Australia (Feeney, Connor, Young, Tucker,

& McPherson,2005),Portugal (Hughes & Stevens,2010),Canada

(Pauls et al[7_TD$DIFF]., 2012) and the UK and elsewhere in Europe (Hamilton,

Lloyd,Monaghan,& Paton,2014) where possession is still illegal.

Are adolescents and young adults especially vulnerable to the

adverse effects of cannabis on health and wellbeing?

The editorial asserts that harms caused to most users by

cannabis are relatively modest,significantly less than those for

tobacco or alcohol. It does say ‘‘at the levels and patterns of use by

most adult cannabis users’’, and this is an important qualification,

because the use of cannabis in Canada, as noted earlier, is much less

than that of alcohol. It has long been recognized that the extent of

harm caused by a drug is proportional to its use (CANYS,2009;

Hughes et al.,2014).If cannabis legalization should prove to be

followed by an important increase in its use, as discussed

elsewhere in this commentary, the difference between the extent

of harms caused by alcohol and by cannabis would almost certainly

be considerably reduced.

A more important reservation even now relates to harms

caused to young users. Both the editorial and the CPF do discuss

the potentially serious effects of cannabis use by adolescents on

mental health and maturation of cognitive functions (Hall &

Degenhardt, 2007). The importance of this topic for policy

considerations warrants a more detailed consideration. The

Dunedin study in New Zealand followed a birth cohort of over

1400 newborns through childhood, adolescence,young adult-

hood and into early middle age. Histories and mental and

physical examinations were repeated at intervals throughout

the study, measuring among many other things the effects of

early acquisition of drug-taking behavior and its maintenance or

cessation (Milne et al., 2009). A thorough analysis of the

Dunedin results (Meier et al.,2012) demonstrated that children

who did not acquire cannabis-taking behavior had a smallbut

significant increase in age-adjusted intelligence score from age

13 to age 38. Those who began cannabis use during adolescence

had a decrease in IQ at age 38, which was more marked the

earlier they had begun use, and the more intensively and

persistently they used.Similar findings were obtained in other

cohort studies (Silins, Horwood, Patton, Fergusson,& Olsson,

2014).

All tested domains of cognitive functioning were affected, and

the effect was recognizable in everyday living,including poor

school performance, higher drop-out rates, and subsequent

restriction of career possibilities.It could not be explained by

decreased years ofschooling, persistent drug presence in the

body, socioeconomic status, or other potential confounders.

Cessation of use was followed by recovery of cognitive functions

in those who began use as young adults,but not in those who

began early in adolescence. The findings are consistent with

experimental studies showing that cannabinoids prevent mature

synapse formation in maturing brain pathways involved in

‘‘executive functioning’’ (Kalant, 2014), and that the same chronic

cannabis regimen (with dosage adjusted for body mass) that

caused permanent impairment of learning and memory in

adolescent rats did not do so in mature adult rats (Stiglick &

Kalant, 1985).

A clinical diagnosis of cannabis dependency by DSM-IV criteria

was found in about 8 10% ofadult users,but in about 16% of

adolescent users (Anthony,2006).A prospective 3-year study of

young adult frequent users, aged 18 to 30 years at baseline, found a

37% cumulative incidence of dependence (van der Pol et al., 2012).

The risk of future lung cancer in heavy cannabis users of military

conscription age represents another type ofvulnerability (Call-

aghan,Allebeck,& Sidorchuk,2013).

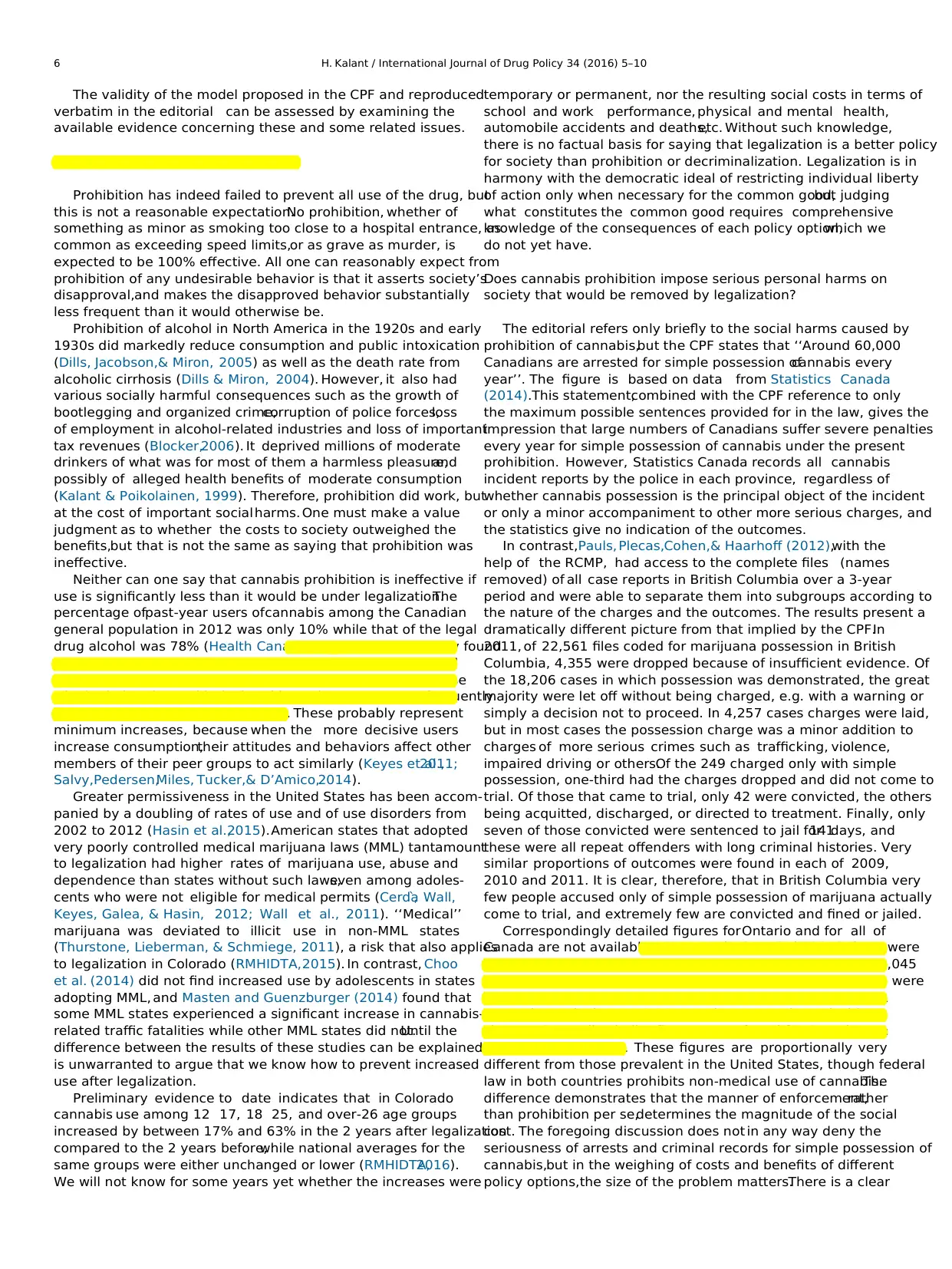

These findings are especially significantfor cannabis policy

decisions because adolescents and young adults are dispropor-

tionately represented among cannabis users.By combining the

provincial statistics of the population age distribution in 2013

(Ontario Ministry of Finance,2014) with the percentages of past-

year users in different age groups as shown in the CPF,one can

estimate that 43% of users are adolescents and young adults

(Table 1).

}

}

Table 1

Calculation of approximate numbers of cannabis users in Ontario population groups below and above 25 years of age in 2013.

Age group Adjusted Population Subtotals* % past-year users Number of users Totals

12 14 298,240 23% 68,595[4_TD$DIFF]

720,72115 19 871,460 30% 261,438

[1_TD$DIFF]2025 967,000 40.4% 390,668

26 29 962,600 40.4% 388,890[5_TD$DIFF]

1,102,294

30 39 1,825,900 17.3% 315,881

[2_TD$DIFF]4049 1,988,000 8.4% 166,992

50 74 3,907,300 5.9% 230,531

* The population totals in the Provincial data are given in 5-year age groups, but the percentages of cannabis users in the CPF document are given by school grades

begin at about age 12 years, and by decade in those above 20 years of age. The adjustments are attempts to reconcile the age groups with the corresponding percen

users.

H. Kalant / International Journal of Drug Policy 34 (2016) 5–10 7

not yet have.

Statistics Canada does indicate that over 699,000 Canadians

have criminal records as a result of convictions on charges of

cannabis possession, many of which occurred decades ago during

their adolescence before the Youth Criminal Justice Act came into

effect. This is certainly an important harmful effect of prohibition

of cannabis possession, and either legalization or decriminalization

would prevent it from happening in the future.However,neither

would undo the harm to those who already have criminal records.

A legislated amnesty would be required, but this could be done in

connection with decriminalization or even with continued

prohibition,and is not necessarily linked to legalization.

As in the United States, some Canadian provinces show greater

severity of application of cannabis prohibition than others.That

could just as logically call for federal government action to impose

uniform moderate sentencing rules across the country as for

legalization of cannabis use.

Does prohibition of cannabis impede the application of

measures to reduce drug-related harm to health?

The editorial’s statement to this effect is more cautious than the

CPF statement that ‘‘The law enforcement focus ofprohibition

drives cannabis users away from prevention,risk reduction and

treatment services’’,for which it cites no supporting literature. In

fact, prohibition of cannabis possession is not necessarily in

conflict with treatment of dependent persons.Diversion of cases

from the justice to the health care system has been occurring with

increasing frequency in Australia (Feeney, Connor, Young, Tucker,

& McPherson,2005),Portugal (Hughes & Stevens,2010),Canada

(Pauls et al[7_TD$DIFF]., 2012) and the UK and elsewhere in Europe (Hamilton,

Lloyd,Monaghan,& Paton,2014) where possession is still illegal.

Are adolescents and young adults especially vulnerable to the

adverse effects of cannabis on health and wellbeing?

The editorial asserts that harms caused to most users by

cannabis are relatively modest,significantly less than those for

tobacco or alcohol. It does say ‘‘at the levels and patterns of use by

most adult cannabis users’’, and this is an important qualification,

because the use of cannabis in Canada, as noted earlier, is much less

than that of alcohol. It has long been recognized that the extent of

harm caused by a drug is proportional to its use (CANYS,2009;

Hughes et al.,2014).If cannabis legalization should prove to be

followed by an important increase in its use, as discussed

elsewhere in this commentary, the difference between the extent

of harms caused by alcohol and by cannabis would almost certainly

be considerably reduced.

A more important reservation even now relates to harms

caused to young users. Both the editorial and the CPF do discuss

the potentially serious effects of cannabis use by adolescents on

mental health and maturation of cognitive functions (Hall &

Degenhardt, 2007). The importance of this topic for policy

considerations warrants a more detailed consideration. The

Dunedin study in New Zealand followed a birth cohort of over

1400 newborns through childhood, adolescence,young adult-

hood and into early middle age. Histories and mental and

physical examinations were repeated at intervals throughout

the study, measuring among many other things the effects of

early acquisition of drug-taking behavior and its maintenance or

cessation (Milne et al., 2009). A thorough analysis of the

Dunedin results (Meier et al.,2012) demonstrated that children

who did not acquire cannabis-taking behavior had a smallbut

significant increase in age-adjusted intelligence score from age

13 to age 38. Those who began cannabis use during adolescence

had a decrease in IQ at age 38, which was more marked the

earlier they had begun use, and the more intensively and

persistently they used.Similar findings were obtained in other

cohort studies (Silins, Horwood, Patton, Fergusson,& Olsson,

2014).

All tested domains of cognitive functioning were affected, and

the effect was recognizable in everyday living,including poor

school performance, higher drop-out rates, and subsequent

restriction of career possibilities.It could not be explained by

decreased years ofschooling, persistent drug presence in the

body, socioeconomic status, or other potential confounders.

Cessation of use was followed by recovery of cognitive functions

in those who began use as young adults,but not in those who

began early in adolescence. The findings are consistent with

experimental studies showing that cannabinoids prevent mature

synapse formation in maturing brain pathways involved in

‘‘executive functioning’’ (Kalant, 2014), and that the same chronic

cannabis regimen (with dosage adjusted for body mass) that

caused permanent impairment of learning and memory in

adolescent rats did not do so in mature adult rats (Stiglick &

Kalant, 1985).

A clinical diagnosis of cannabis dependency by DSM-IV criteria

was found in about 8 10% ofadult users,but in about 16% of

adolescent users (Anthony,2006).A prospective 3-year study of

young adult frequent users, aged 18 to 30 years at baseline, found a

37% cumulative incidence of dependence (van der Pol et al., 2012).

The risk of future lung cancer in heavy cannabis users of military

conscription age represents another type ofvulnerability (Call-

aghan,Allebeck,& Sidorchuk,2013).

These findings are especially significantfor cannabis policy

decisions because adolescents and young adults are dispropor-

tionately represented among cannabis users.By combining the

provincial statistics of the population age distribution in 2013

(Ontario Ministry of Finance,2014) with the percentages of past-

year users in different age groups as shown in the CPF,one can

estimate that 43% of users are adolescents and young adults

(Table 1).

}

}

Table 1

Calculation of approximate numbers of cannabis users in Ontario population groups below and above 25 years of age in 2013.

Age group Adjusted Population Subtotals* % past-year users Number of users Totals

12 14 298,240 23% 68,595[4_TD$DIFF]

720,72115 19 871,460 30% 261,438

[1_TD$DIFF]2025 967,000 40.4% 390,668

26 29 962,600 40.4% 388,890[5_TD$DIFF]

1,102,294

30 39 1,825,900 17.3% 315,881

[2_TD$DIFF]4049 1,988,000 8.4% 166,992

50 74 3,907,300 5.9% 230,531

* The population totals in the Provincial data are given in 5-year age groups, but the percentages of cannabis users in the CPF document are given by school grades

begin at about age 12 years, and by decade in those above 20 years of age. The adjustments are attempts to reconcile the age groups with the corresponding percen

users.

H. Kalant / International Journal of Drug Policy 34 (2016) 5–10 7

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Would legalization plus strict regulation effectively prevent

access to cannabis by underage users?

The claim that alcohol and tobacco control measures provide a

good model for controlling youth access to cannabis after

legalization (Pacula,Kilmer, Wagenaar,Chaloupka,& Caulkins,

2014; Room, 2014) is also contrary to experience. Alcohol

continues to be widely used by Ontario students at all age levels

examined (Boak, Hamilton, Adlaf, & Mann, 2013), despite

regulations against its sale or distribution to minors.Past-year

use was reported by almost 10% of Grade 7 students (1213 years

old), increasing to 74% of Grade 12 students. About 67% reported

drinking at least once a week, 20% reported binge-drinking within

the past month and 18% reported getting intoxicated in the same

period.

Among fatally injured drivers in Canada in the period 2000 to

2007, 17.4% ofthose aged 19 years or less tested positive for

alcohol,18.6% for drugs (predominantly cannabis) and about 14%

for both alcohol and drugs (Beasley,Beirness,& Porath-Waller,

2011). Similarly high and growing percentages report driving

under the influence of alcohol or cannabis,and even more report

being passengers in vehicles operated by alcohol- or cannabis-

impaired drivers (Adlaf, Mann, & Paglia, 2003). These figures

become more disturbing when viewed againstthe increase in

cannabis-related driverfatalities seen in Colorado after broad

commercialization of ‘‘medicalmarijuana’’(Salomonsen-Sautel,

Min, Sakai,Thurstone,& Hopfer,2014).Such statistics of alcohol

use,binge drinking and driving while intoxicated among under-

age users in Ontario can hardly be considered evidence for the

efficacy of current alcohol regulations in preventing access to

alcohol by those considered to be at too great a risk to be allowed to

use it. It is therefore puzzling that the CPF, as cited in the editorial,

without presenting any supporting evidence assumes that

regulation would be successfulin preventing access of under-

age users to cannabis after legalization.

Would legalization of cannabis, combined with regulation,

significantly reduce the illicit market and its associated

dangers?

As the CPF states,experience with alcoholand tobacco has

shown that price is an important determinant of per capita

consumption and of the numbers of those who suffer serious harm

from excessive consumption (Guindon,2014; Her, Giesbrecht,

Room,& Rehm,1999; Wakefield & Chaloupka,2000).Most adult

users would probably prefer to buy legal cannabis even if the price

is somewhat higher than the street price,but if the regulations

prevent sales to underage users,they would have no incentive to

stop purchasing from their accustomed illicit sources. Moreover, if

the price for legal cannabis is made significantly lower to undercut

the black market, the levels of use, especially by young people with

more limited financial resources, are likely to increase even further

rather than decrease (Anderson, 2007; Caulkins, Kilmer, MacCoun,

Pacula,& Reuter,2012; Osterberg,2011).

Tobacco presents a better model than alcohol for comparison

with legalized cannabis, because the reduction of use by the

population at large has been achieved without use ofcriminal

sanctions,by a sustained campaign of public education on health

consequences of smoking (Wakefield & Chaloupka, 2000), compa-

rable to that which led to a marked decrease of alcoholuse in

France.But we do not yet appear to have developed an effective

approach with respect to cannabis comparable to that with

tobacco, especially for adolescents. A study of high school students

in the United States ongoing since 1976 has shown that likelihood

of marijuana use was inversely related to the percentages of

students in specific birth cohorts who disapproved of use and who

believed the information about its perceived dangers. Use among

the student population as a whole has gone through two cycles of

rising and falling, but the determinants of attitude in different birth

cohorts are not yet understood (Keyes et al.,2011).Use among

Canadian youth is currently decreasing,but until we know how

their attitudes are determined,and how to direct these so as to

build a health-conscious approach to cannabis use among them,

we cannot count on continued decrease of use.

The editorial and the CPF set out some very good recommenda-

tions for controlling the levelof use of legal cannabis: prohibit

marketing and advertising, limit density of sales outlets and hours

of sale, set maximum permissible concentration of THC, and some

would add setting maximum amount per sale. But other

recommendations lack substance, such as the proposal that pricing

policy should limit demand while minimizing the opportunity for

continuation of lucrative black markets. Limiting demand calls for

higher prices, yet higher prices encourage competition from lower-

priced black markets. The authors offer no way of dealing with this

incompatibility,or of selecting an optimal target price.

Does the possibility of deriving additional government

resources through taxation of legalized cannabis represent a

significant gain for society?

A major reason advanced by politicians who favor legalization

of cannabis is the possibility ofgaining a major new source of

revenue,comparable to that from the sale of alcohol,to support

increasingly expensive public health, education and social

programs.However, alcohol consumption generates very high

social and economic costs, possibly greater than the revenue

derived from the production and sale of alcohol (Rehm et al., 2007).

The CPF advances no reason why this would not also be true of

legal cannabis sale by a government monopoly.A very limited

analysis of some of the costs attributable to cannabis under the

present legal prohibition (Fischer, Imtiaz, Rudzinski, & Rehm,

2016) shows the need for much more extensive investigation of

this question. The CPF speaks of a need to avoid a financial

incentive for a government monopoly to increase cannabis sales.

This is idealistic but surely rather naive. Experience with the

Canadian provincial government monopolies of sales of spirits and

imported wines, with their sophisticated marketing activities and

maximized opportunities for access, does not offer any reason for

believing that sales practices with cannabis would be different.

Would legalization of cannabis reduce greatly the costs of

police and court work caused by the current policy of

prohibition?

The CPF states (p.11) that legalization ‘‘would eliminate the

more than $1 billion Canada spends annually to enforce cannabis

possession laws’’.However, other estimates are substantially

lower. One article quotes a Department of Justice budget for the

drug control strategy for all of Canada as $528 million for the

period 2012 2017, or about $106 million a year, and a Simon

Fraser University estimate of $10.5 to $18.5 million as the annual

cost for British Columbia (MacQueen,2013).

More importantly, if the British Columbia findings on the

disposition of cannabis possession incidents are representative of

Canada as a whole (which remains to be determined), there would

appear to be very little police or court time devoted to enforcing

the law against possession alone. The great majority of possession

charges were add-ons in cases in which the accused were detained

for other offences. If cannabis had been legal, the police would still

have had to expend the same effort in detaining and charging them

for the principal offences,and the courts would still have had to

deal with those principal charges. Under legalization, illicit

H. Kalant / International Journal of Drug Policy 34 (2016) 5–108

access to cannabis by underage users?

The claim that alcohol and tobacco control measures provide a

good model for controlling youth access to cannabis after

legalization (Pacula,Kilmer, Wagenaar,Chaloupka,& Caulkins,

2014; Room, 2014) is also contrary to experience. Alcohol

continues to be widely used by Ontario students at all age levels

examined (Boak, Hamilton, Adlaf, & Mann, 2013), despite

regulations against its sale or distribution to minors.Past-year

use was reported by almost 10% of Grade 7 students (1213 years

old), increasing to 74% of Grade 12 students. About 67% reported

drinking at least once a week, 20% reported binge-drinking within

the past month and 18% reported getting intoxicated in the same

period.

Among fatally injured drivers in Canada in the period 2000 to

2007, 17.4% ofthose aged 19 years or less tested positive for

alcohol,18.6% for drugs (predominantly cannabis) and about 14%

for both alcohol and drugs (Beasley,Beirness,& Porath-Waller,

2011). Similarly high and growing percentages report driving

under the influence of alcohol or cannabis,and even more report

being passengers in vehicles operated by alcohol- or cannabis-

impaired drivers (Adlaf, Mann, & Paglia, 2003). These figures

become more disturbing when viewed againstthe increase in

cannabis-related driverfatalities seen in Colorado after broad

commercialization of ‘‘medicalmarijuana’’(Salomonsen-Sautel,

Min, Sakai,Thurstone,& Hopfer,2014).Such statistics of alcohol

use,binge drinking and driving while intoxicated among under-

age users in Ontario can hardly be considered evidence for the

efficacy of current alcohol regulations in preventing access to

alcohol by those considered to be at too great a risk to be allowed to

use it. It is therefore puzzling that the CPF, as cited in the editorial,

without presenting any supporting evidence assumes that

regulation would be successfulin preventing access of under-

age users to cannabis after legalization.

Would legalization of cannabis, combined with regulation,

significantly reduce the illicit market and its associated

dangers?

As the CPF states,experience with alcoholand tobacco has

shown that price is an important determinant of per capita

consumption and of the numbers of those who suffer serious harm

from excessive consumption (Guindon,2014; Her, Giesbrecht,

Room,& Rehm,1999; Wakefield & Chaloupka,2000).Most adult

users would probably prefer to buy legal cannabis even if the price

is somewhat higher than the street price,but if the regulations

prevent sales to underage users,they would have no incentive to

stop purchasing from their accustomed illicit sources. Moreover, if

the price for legal cannabis is made significantly lower to undercut

the black market, the levels of use, especially by young people with

more limited financial resources, are likely to increase even further

rather than decrease (Anderson, 2007; Caulkins, Kilmer, MacCoun,

Pacula,& Reuter,2012; Osterberg,2011).

Tobacco presents a better model than alcohol for comparison

with legalized cannabis, because the reduction of use by the

population at large has been achieved without use ofcriminal

sanctions,by a sustained campaign of public education on health

consequences of smoking (Wakefield & Chaloupka, 2000), compa-

rable to that which led to a marked decrease of alcoholuse in

France.But we do not yet appear to have developed an effective

approach with respect to cannabis comparable to that with

tobacco, especially for adolescents. A study of high school students

in the United States ongoing since 1976 has shown that likelihood

of marijuana use was inversely related to the percentages of

students in specific birth cohorts who disapproved of use and who

believed the information about its perceived dangers. Use among

the student population as a whole has gone through two cycles of

rising and falling, but the determinants of attitude in different birth

cohorts are not yet understood (Keyes et al.,2011).Use among

Canadian youth is currently decreasing,but until we know how

their attitudes are determined,and how to direct these so as to

build a health-conscious approach to cannabis use among them,

we cannot count on continued decrease of use.

The editorial and the CPF set out some very good recommenda-

tions for controlling the levelof use of legal cannabis: prohibit

marketing and advertising, limit density of sales outlets and hours

of sale, set maximum permissible concentration of THC, and some

would add setting maximum amount per sale. But other

recommendations lack substance, such as the proposal that pricing

policy should limit demand while minimizing the opportunity for

continuation of lucrative black markets. Limiting demand calls for

higher prices, yet higher prices encourage competition from lower-

priced black markets. The authors offer no way of dealing with this

incompatibility,or of selecting an optimal target price.

Does the possibility of deriving additional government

resources through taxation of legalized cannabis represent a

significant gain for society?

A major reason advanced by politicians who favor legalization

of cannabis is the possibility ofgaining a major new source of

revenue,comparable to that from the sale of alcohol,to support

increasingly expensive public health, education and social

programs.However, alcohol consumption generates very high

social and economic costs, possibly greater than the revenue

derived from the production and sale of alcohol (Rehm et al., 2007).

The CPF advances no reason why this would not also be true of

legal cannabis sale by a government monopoly.A very limited

analysis of some of the costs attributable to cannabis under the

present legal prohibition (Fischer, Imtiaz, Rudzinski, & Rehm,

2016) shows the need for much more extensive investigation of

this question. The CPF speaks of a need to avoid a financial

incentive for a government monopoly to increase cannabis sales.

This is idealistic but surely rather naive. Experience with the

Canadian provincial government monopolies of sales of spirits and

imported wines, with their sophisticated marketing activities and

maximized opportunities for access, does not offer any reason for

believing that sales practices with cannabis would be different.

Would legalization of cannabis reduce greatly the costs of

police and court work caused by the current policy of

prohibition?

The CPF states (p.11) that legalization ‘‘would eliminate the

more than $1 billion Canada spends annually to enforce cannabis

possession laws’’.However, other estimates are substantially

lower. One article quotes a Department of Justice budget for the

drug control strategy for all of Canada as $528 million for the

period 2012 2017, or about $106 million a year, and a Simon

Fraser University estimate of $10.5 to $18.5 million as the annual

cost for British Columbia (MacQueen,2013).

More importantly, if the British Columbia findings on the

disposition of cannabis possession incidents are representative of

Canada as a whole (which remains to be determined), there would

appear to be very little police or court time devoted to enforcing

the law against possession alone. The great majority of possession

charges were add-ons in cases in which the accused were detained

for other offences. If cannabis had been legal, the police would still

have had to expend the same effort in detaining and charging them

for the principal offences,and the courts would still have had to

deal with those principal charges. Under legalization, illicit

H. Kalant / International Journal of Drug Policy 34 (2016) 5–108

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

production and trafficking would stillbe criminal offences,and

would still consume police and court time.It is therefore unclear

that very large economies to the justice system would be produced

by legalization of cannabis.

Is decriminalization a half measure, subject to manipulation by

police bias?

The editorial,like the CPF,refers to decriminalization as a half

measure because of three alleged flaws.The first is that ‘‘it may

encourage the production and distribution of cannabis’’,but no

evidence is offered to support this conjecture. Indeed the

decriminalization systems adopted in Portugal, Australia and

some American states did not increase use and may even have

reduced use and drug-related harms (Hughes & Stevens,2010;

Hughes & Stevens, 2012; Single, Christie, & Ali, 2000). The second

‘‘flaw’’ is that decriminalization ‘‘does not address the health

harms of cannabis use’’.The authors themselves have correctly

stated that legalization also does not address these harms, and that

specific regulatory mechanisms must be adopted for that purpose.

The Portuguese decriminalization system has adopted other

mechanisms to address these harms,including education,admo-

nition, and referral to treatment.

The third ‘‘flaw’’ is police bias in enforcement of the law under

decriminalization and inequality of imposition of penalties against

different subgroups of the population.This concern may well be

legitimate. However, the document does not discuss the possibility

that police bias could also persist after legalization,in relation to

prosecution for illicit production and trafficking.It also does not

examine alternative methods of dealing with this problem, such as

educational and administrative approaches to altering the police

culture, nor does it compare alternatives with respect to their costs

and benefits.

Discussion

Legalization of nonmedical use of cannabis and strict regulation

of its potency,price and accessibility represents an idealthat a

democratic society might well aim at, because it proposes the least

restriction of personal freedom compatible with the protection of

those most vulnerable to the adverse effects of cannabis use. Over a

15 year period Canadian public support of legalization gradually

rose to 37% in 2014 (Ipsos Reid, 2014). In 2015, it rose more rapidly,

in tandem with the popularity of Liberal Party leader Justin

Trudeau, as stated in the editorial. After his endorsementof

legalization a 2015 Ipsos-Reid poll found 65% in favour of

decriminalization, but the wording of the question was compatible

with legalization rather than decriminalization.It is difficult to

judge whether this shift of public opinion represents a ‘‘celebrity

effect’’,uncertainty of the meanings of the terms,a progressive

movement away from laws considered oppressive, or ‘‘normaliza-

tion’’ of cannabis use (Parker, Williams, & Aldridge, 2002), as a large

majority in that poll did not consider marijuana laws to be a high

priority matter.

Sound policy decisions require at least two essential elements:

(1) complete, objective, unbiased presentation of the facts

concerning the policy matter under review,including both what

we know and what we do not yet know,and scientifically based

predictions about the most probable consequences of the various

policy options; (2) value judgments that classify the various facts

and projections as good or bad,beneficialor harmful, useful or

useless,for society as a whole. It is also necessary to assign

quantitative weights – how good or bad, how beneficial or harmful

– so that the various policy options can be compared with respect to

their overall contribution to harm reduction and society’s wellbeing

(Kalant & Kalant,1971; Shanahan,Gerard,& Ritter,2014).

As set out in the preceding sections, we lack major portions of

the necessary evidence for making such a rational choice.

Therefore, any decision to legalize cannabis in Canada now cannot

really be ‘‘evidence-based’’and must rest primarily on broader

social values,ideals and hopes rather than on a thorough cost-

benefit accounting.A strong argument can be made for decrimi-

nalizing possession of cannabis for personal use, while monitoring

closely the effects of legalization,both beneficial and harmful,in

other states or countries that have already adopted it. A system of

legalization and strict controls could possibly work to the benefit of

society, but only if we find effective solutions to the problems set

out above before making changes that may cost society more than

it gains.

References

Addiction Research Foundation (1997).Cannabis.Health and Public Policy Retrieved

April 21, 2016,from http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/about_camh/influencing_-

public_policy/Documents/Cannabis%20HealthPublicPolicy1997.pdf.

Adlaf, E. M., Mann, R. E., & Paglia, A. (2003). Drinking, cannabis use and driving among

Ontario students.CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal,168,565–566.

Anderson, P. (2007). A safe, sensible and social AHRSE: new Labour and alcohol policy.

Addiction,102,1515–1521.

Anthony, J. C. (2006). The epidemiology of cannabis dependence. In R. A. Roffman & R. S

Stephens (Eds.),Cannabis dependence: its nature,consequences treatment (pp.58–

195).Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beasley,E. E., Beirness,D. J., & Porath-Waller,A. J. (2011).A comparison of drug- and

alcohol-involved motor vehicle driver fatalities.Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Sub-

stance Abuse.

Blocker,J. S.,Jr. (2006).Did Prohibition really work? Alcohol prohibition as a public

health innovation.American Journal of Public Health,96,233–243.

Boak,A., Hamilton,H. A., Adlaf,E. N., & Mann,R. E. (2013).Drug Use Among Ontario

Students 19772013. CAMH Research Document Series No. 36 ISBN: 978-1-77114-

167-3.

Boyce, J. (2013). Adult criminal court statistics in Canada 2011/2012, Table 5 and Chart 1

Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.ISSN 1209-6393.(Juristat).

Callaghan,R. C., Allebeck,P., & Sidorchuk,A. (2013).Marijuana use and risk of lung

cancer: a 40-year cohort study.Cancer Causes & Control,24,1811–1820.

Canadian Government Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs (1972).

Ottawa: Information Canada.

CANSIM (2013).Table 252-0051.Incident-based crime statistics,by detailed violations,

Ontario. Retrieved 2 November 2014 from http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/

a01?lang=eng.

CANYS – Council on Addictions of New York State (2009).Alcoholconsumption and

alcohol-related problems.Retrieved 29 October 2014 from http://www.canys.net/

images/ConsumptionBrief%20-%20Final%20-%206.29.09.pdf.

Caulkins,J. P., Kilmer, B., MacCoun,R. J., Pacula,R. L., & Reuter,P. (2012). Design

considerations for legalizing cannabis: lessons inspired by analysis of California’s

Proposition 19.Addiction,107,865–871.

Cerda`, M., Wall, M., Keyes, K. M., Galea, S., & Hasin, D. (2012). Medical marijuana laws in

50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization ofmedical

marijuana and marijuana use,abuse and dependence.Drug and AlcoholDepen-

dence,120,22–27.

Choo, E. K., Benz, M., Zaller, N., Warren, O., Rising, K. L., & McConnell, K. J. (2014). The

impact of state medical marijuana legislation on adolescent marijuana use. Journal

of Adolescent Health,55,160–166.

Cre´pault,J.-F. (2014).Cannabis Policy Framework.CAMH Research Document Series No.

40,October 2014.Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Dills, A. K., Jacobson,M., & Miron, J. A. (2005).The effect of alcoholprohibition on

alcohol consumption: evidence from drunkenness arrests.Economics Letters,86,

279–284.

Dills, A. K.,& Miron, J. A. (2004).Alcohol prohibition and cirrhosis.American Law and

Economics Reviews,6(2),2185–2318.http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aler/ahh003

Feeney, G. F. X., Connor, J. P., Young, R. M., Tucker, J., & McPherson, A. (2005). Cannabis

dependence and mental health perception amongst people diverted by police after

arrest for cannabis-related offending behaviour in Australia. Criminal Behaviour &

Mental Health,15,249–260.

Fischer,B., Imtiaz, S.,Rudzinski,K., & Rehm,J. ([36_TD$DIFF]2016).Crude estimates of cannabis-

attributable mortality and morbidity in Canada -implications for public health

focused intervention priorities. Journal of Public Health, [37_TD$DIFF]38(January (28)

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdv005

Guindon, G. E. (2014). The impact of tobacco prices on smoking onset: a methodologi-

cal review.Tobacco Control,23(2),e5.

Haden,M., & Emerson,B. (2014).A vision for cannabis regulation: a public health

approach based on lessons learned from the regulation of alcoholand tobacco.

Open Medicine,8(2),1–16.

Hall, W., & Degenhardt,L. (2007). Prevalence and correlates ofcannabis use in

developed and developing countries.Current Opinion in Psychiatry,20,393–397.

Hamilton, I., Lloyd, C., Monaghan,M. P., & Paton,K. (2014).The emerging cannabis

treatment population.Drugs and Alcohol Today,14.159-153.Retrieved at http://

eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/82720/17/Cannabis%20Treatment.pdf.

H. Kalant / International Journal of Drug Policy 34 (2016) 5–10 9

would still consume police and court time.It is therefore unclear

that very large economies to the justice system would be produced

by legalization of cannabis.

Is decriminalization a half measure, subject to manipulation by

police bias?

The editorial,like the CPF,refers to decriminalization as a half

measure because of three alleged flaws.The first is that ‘‘it may

encourage the production and distribution of cannabis’’,but no

evidence is offered to support this conjecture. Indeed the

decriminalization systems adopted in Portugal, Australia and

some American states did not increase use and may even have

reduced use and drug-related harms (Hughes & Stevens,2010;

Hughes & Stevens, 2012; Single, Christie, & Ali, 2000). The second

‘‘flaw’’ is that decriminalization ‘‘does not address the health

harms of cannabis use’’.The authors themselves have correctly

stated that legalization also does not address these harms, and that

specific regulatory mechanisms must be adopted for that purpose.

The Portuguese decriminalization system has adopted other

mechanisms to address these harms,including education,admo-

nition, and referral to treatment.

The third ‘‘flaw’’ is police bias in enforcement of the law under

decriminalization and inequality of imposition of penalties against

different subgroups of the population.This concern may well be

legitimate. However, the document does not discuss the possibility

that police bias could also persist after legalization,in relation to

prosecution for illicit production and trafficking.It also does not

examine alternative methods of dealing with this problem, such as

educational and administrative approaches to altering the police

culture, nor does it compare alternatives with respect to their costs

and benefits.

Discussion

Legalization of nonmedical use of cannabis and strict regulation

of its potency,price and accessibility represents an idealthat a

democratic society might well aim at, because it proposes the least

restriction of personal freedom compatible with the protection of

those most vulnerable to the adverse effects of cannabis use. Over a

15 year period Canadian public support of legalization gradually

rose to 37% in 2014 (Ipsos Reid, 2014). In 2015, it rose more rapidly,

in tandem with the popularity of Liberal Party leader Justin

Trudeau, as stated in the editorial. After his endorsementof

legalization a 2015 Ipsos-Reid poll found 65% in favour of

decriminalization, but the wording of the question was compatible

with legalization rather than decriminalization.It is difficult to

judge whether this shift of public opinion represents a ‘‘celebrity

effect’’,uncertainty of the meanings of the terms,a progressive

movement away from laws considered oppressive, or ‘‘normaliza-

tion’’ of cannabis use (Parker, Williams, & Aldridge, 2002), as a large

majority in that poll did not consider marijuana laws to be a high

priority matter.

Sound policy decisions require at least two essential elements:

(1) complete, objective, unbiased presentation of the facts

concerning the policy matter under review,including both what

we know and what we do not yet know,and scientifically based

predictions about the most probable consequences of the various

policy options; (2) value judgments that classify the various facts

and projections as good or bad,beneficialor harmful, useful or

useless,for society as a whole. It is also necessary to assign

quantitative weights – how good or bad, how beneficial or harmful

– so that the various policy options can be compared with respect to

their overall contribution to harm reduction and society’s wellbeing

(Kalant & Kalant,1971; Shanahan,Gerard,& Ritter,2014).

As set out in the preceding sections, we lack major portions of

the necessary evidence for making such a rational choice.

Therefore, any decision to legalize cannabis in Canada now cannot

really be ‘‘evidence-based’’and must rest primarily on broader

social values,ideals and hopes rather than on a thorough cost-

benefit accounting.A strong argument can be made for decrimi-

nalizing possession of cannabis for personal use, while monitoring

closely the effects of legalization,both beneficial and harmful,in

other states or countries that have already adopted it. A system of

legalization and strict controls could possibly work to the benefit of

society, but only if we find effective solutions to the problems set

out above before making changes that may cost society more than

it gains.

References

Addiction Research Foundation (1997).Cannabis.Health and Public Policy Retrieved

April 21, 2016,from http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/about_camh/influencing_-

public_policy/Documents/Cannabis%20HealthPublicPolicy1997.pdf.

Adlaf, E. M., Mann, R. E., & Paglia, A. (2003). Drinking, cannabis use and driving among

Ontario students.CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal,168,565–566.

Anderson, P. (2007). A safe, sensible and social AHRSE: new Labour and alcohol policy.

Addiction,102,1515–1521.

Anthony, J. C. (2006). The epidemiology of cannabis dependence. In R. A. Roffman & R. S

Stephens (Eds.),Cannabis dependence: its nature,consequences treatment (pp.58–

195).Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beasley,E. E., Beirness,D. J., & Porath-Waller,A. J. (2011).A comparison of drug- and

alcohol-involved motor vehicle driver fatalities.Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Sub-

stance Abuse.

Blocker,J. S.,Jr. (2006).Did Prohibition really work? Alcohol prohibition as a public

health innovation.American Journal of Public Health,96,233–243.

Boak,A., Hamilton,H. A., Adlaf,E. N., & Mann,R. E. (2013).Drug Use Among Ontario

Students 19772013. CAMH Research Document Series No. 36 ISBN: 978-1-77114-

167-3.

Boyce, J. (2013). Adult criminal court statistics in Canada 2011/2012, Table 5 and Chart 1

Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.ISSN 1209-6393.(Juristat).

Callaghan,R. C., Allebeck,P., & Sidorchuk,A. (2013).Marijuana use and risk of lung

cancer: a 40-year cohort study.Cancer Causes & Control,24,1811–1820.

Canadian Government Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs (1972).

Ottawa: Information Canada.

CANSIM (2013).Table 252-0051.Incident-based crime statistics,by detailed violations,

Ontario. Retrieved 2 November 2014 from http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/

a01?lang=eng.

CANYS – Council on Addictions of New York State (2009).Alcoholconsumption and

alcohol-related problems.Retrieved 29 October 2014 from http://www.canys.net/

images/ConsumptionBrief%20-%20Final%20-%206.29.09.pdf.

Caulkins,J. P., Kilmer, B., MacCoun,R. J., Pacula,R. L., & Reuter,P. (2012). Design

considerations for legalizing cannabis: lessons inspired by analysis of California’s

Proposition 19.Addiction,107,865–871.

Cerda`, M., Wall, M., Keyes, K. M., Galea, S., & Hasin, D. (2012). Medical marijuana laws in

50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization ofmedical

marijuana and marijuana use,abuse and dependence.Drug and AlcoholDepen-

dence,120,22–27.

Choo, E. K., Benz, M., Zaller, N., Warren, O., Rising, K. L., & McConnell, K. J. (2014). The

impact of state medical marijuana legislation on adolescent marijuana use. Journal

of Adolescent Health,55,160–166.

Cre´pault,J.-F. (2014).Cannabis Policy Framework.CAMH Research Document Series No.

40,October 2014.Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Dills, A. K., Jacobson,M., & Miron, J. A. (2005).The effect of alcoholprohibition on

alcohol consumption: evidence from drunkenness arrests.Economics Letters,86,

279–284.

Dills, A. K.,& Miron, J. A. (2004).Alcohol prohibition and cirrhosis.American Law and

Economics Reviews,6(2),2185–2318.http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aler/ahh003

Feeney, G. F. X., Connor, J. P., Young, R. M., Tucker, J., & McPherson, A. (2005). Cannabis

dependence and mental health perception amongst people diverted by police after

arrest for cannabis-related offending behaviour in Australia. Criminal Behaviour &

Mental Health,15,249–260.

Fischer,B., Imtiaz, S.,Rudzinski,K., & Rehm,J. ([36_TD$DIFF]2016).Crude estimates of cannabis-

attributable mortality and morbidity in Canada -implications for public health

focused intervention priorities. Journal of Public Health, [37_TD$DIFF]38(January (28)

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdv005

Guindon, G. E. (2014). The impact of tobacco prices on smoking onset: a methodologi-

cal review.Tobacco Control,23(2),e5.

Haden,M., & Emerson,B. (2014).A vision for cannabis regulation: a public health

approach based on lessons learned from the regulation of alcoholand tobacco.

Open Medicine,8(2),1–16.