CVD Risk Factors: Income & Education

VerifiedAdded on 2020/04/13

|23

|4540

|370

AI Summary

This assignment analyzes the relationship between cardiovascular disease (CVD) and two key social determinants of health: income and education. It utilizes data from Statistics Canada's Canadian Community Health Survey to illustrate how these factors influence CVD prevalence among older adults. The analysis involves comparing rates of CVD across different income levels and educational qualifications, highlighting potential disparities. The assignment also references the World Health Organization's Social Determinants of Health model to provide a broader context for understanding the complex interplay between social factors and health outcomes.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Running head: CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 1

Cardiovascular Disease and Social Determinants

Name

Institution

Cardiovascular Disease and Social Determinants

Name

Institution

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 2

The Impacts of the Social Determinants of Health on Cardiovascular Disease in Older

Adults

Nearly six percent of Canadians were living with cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 2015;

a disease which has a mortality rate of 194.7 deaths per 100,000 (Public Health Agency of

Canada, 2017b). Older adults are one of many vulnerable populations in Canada and there are a

variety of factors that make them more vulnerable. This paper will explore how social

determinants of health (SDOH), specifically socioeconomic status, affects Canadian and

international multicultural older adult populations with (CVD), include a SDOH model, followed

by public health implications that arise as a result of this issue. We will examine why these

socioeconomic status may affect this vulnerable population and explore information about CVD.

For the purposes of this research, older adults are defined as individuals between the ages

of 55 and 79. According to Raphael (2016), there are many factors that make senior populations

more vulnerable or susceptible to higher mortality rates; those including, but are not limited to

SDOH such as personal health practices/coping, education, socioeconomic status (SES), gender,

and social support systems. When examining the rates of CVD in older adults a comparison will

be made between those of low and high SES. SES will be measured using household income and

The Impacts of the Social Determinants of Health on Cardiovascular Disease in Older

Adults

Nearly six percent of Canadians were living with cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 2015;

a disease which has a mortality rate of 194.7 deaths per 100,000 (Public Health Agency of

Canada, 2017b). Older adults are one of many vulnerable populations in Canada and there are a

variety of factors that make them more vulnerable. This paper will explore how social

determinants of health (SDOH), specifically socioeconomic status, affects Canadian and

international multicultural older adult populations with (CVD), include a SDOH model, followed

by public health implications that arise as a result of this issue. We will examine why these

socioeconomic status may affect this vulnerable population and explore information about CVD.

For the purposes of this research, older adults are defined as individuals between the ages

of 55 and 79. According to Raphael (2016), there are many factors that make senior populations

more vulnerable or susceptible to higher mortality rates; those including, but are not limited to

SDOH such as personal health practices/coping, education, socioeconomic status (SES), gender,

and social support systems. When examining the rates of CVD in older adults a comparison will

be made between those of low and high SES. SES will be measured using household income and

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 3

level of education. The writers of this paper believe that older adults that have a lower level of

education will have a higher rate of CVD disease due to diminished access or knowledge to

support and foundations to live or obtain a better quality of lifestyle. The writers also believe that

along with a lower level of education would contribute to a lower level of income, thus putting

older adults in a position to not obtain a healthier lifestyle and higher quality of living.

Cardiovascular diseases affect the heart and blood vessels and includes coronary heart

disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, rheumatic heart disease, congenital

heart disease, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (World Health Organization,

2017). CVD is a rampant problem for developing nations and is the number one cause of death

worldwide (World Health Organization, 2017). According to the Canadian Chronic Disease

Surveillance System (CCDSS) incident rates of heart attacks in the Canadian population for age

groups, 50 - 64 and 65-79 are 2.38% and 5.55%, respectively (Public Health Agency of Canada,

2017c). This is much higher than age groups 35 - 49, who were 0.61% of the population that

experience heart attacks (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017c). In the United States, 69.1%

of men and 67.9% of women aged 60 - 79 suffer from some form of CVD (American Heart

Association, 2016). Diseases of the heart are the lead cause of death for American women over

65 years old (American Heart Association, 2016).

CVD is commonly diagnosed by a physician in regular or emergency room visits. Data is

then collected through a variety of sampling methods. Specifically, the CCDSS collects data

based on health insurance registry databases that are linked to physician billing and hospital

level of education. The writers of this paper believe that older adults that have a lower level of

education will have a higher rate of CVD disease due to diminished access or knowledge to

support and foundations to live or obtain a better quality of lifestyle. The writers also believe that

along with a lower level of education would contribute to a lower level of income, thus putting

older adults in a position to not obtain a healthier lifestyle and higher quality of living.

Cardiovascular diseases affect the heart and blood vessels and includes coronary heart

disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, rheumatic heart disease, congenital

heart disease, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (World Health Organization,

2017). CVD is a rampant problem for developing nations and is the number one cause of death

worldwide (World Health Organization, 2017). According to the Canadian Chronic Disease

Surveillance System (CCDSS) incident rates of heart attacks in the Canadian population for age

groups, 50 - 64 and 65-79 are 2.38% and 5.55%, respectively (Public Health Agency of Canada,

2017c). This is much higher than age groups 35 - 49, who were 0.61% of the population that

experience heart attacks (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017c). In the United States, 69.1%

of men and 67.9% of women aged 60 - 79 suffer from some form of CVD (American Heart

Association, 2016). Diseases of the heart are the lead cause of death for American women over

65 years old (American Heart Association, 2016).

CVD is commonly diagnosed by a physician in regular or emergency room visits. Data is

then collected through a variety of sampling methods. Specifically, the CCDSS collects data

based on health insurance registry databases that are linked to physician billing and hospital

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 4

databases (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017a). Through this collection technique, errors

from self-reporting are avoided. Another common information data base is the Canadian

Community Health Survey (CCHS). A survey is provided to a cross-section of the country who

then are responsible for self-reporting (Statistics Canada, 2016). When self-reporting is used for

collecting information there is always a chance that respondents will be intentionally dishonest

or misunderstand a question and provide the wrong answer.

SES and education are SDOH that are the strongest predictors to affect CVD (Joffres et

al., 2013; Winkleby et al., 1992). SES reflects spending ability, housing, diet, and medical care

based on income, whereas education reflects skills for social, psychological, and economic

resources (Winkleby et al., 1992).

A healthy diet is essential for the prevention of CVD yet income can be a stumbling block as

much of heart disease medication costs are not covered under Medicare (Gucciardi et al., 2009).

Those with low income tend to lack insurance coverage that covers expensive medications such

as those for CVD, which are among the most expensive within Canada (Booth et al., 2012;

Campbell et al., 2012). Booth et al. (2012) found an increase in diabetes related mortality rates

between those of high and low SES especially in those over the age of 65. Woodward et al.

(2015) revealed that CVD is associated with lower SES. A community-based study from Turkey

revealed that unhealthy diet was associated with lower SES (OR = 3.31) and lower education

(OR=4.48) (Simsek et al., 2013).

databases (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017a). Through this collection technique, errors

from self-reporting are avoided. Another common information data base is the Canadian

Community Health Survey (CCHS). A survey is provided to a cross-section of the country who

then are responsible for self-reporting (Statistics Canada, 2016). When self-reporting is used for

collecting information there is always a chance that respondents will be intentionally dishonest

or misunderstand a question and provide the wrong answer.

SES and education are SDOH that are the strongest predictors to affect CVD (Joffres et

al., 2013; Winkleby et al., 1992). SES reflects spending ability, housing, diet, and medical care

based on income, whereas education reflects skills for social, psychological, and economic

resources (Winkleby et al., 1992).

A healthy diet is essential for the prevention of CVD yet income can be a stumbling block as

much of heart disease medication costs are not covered under Medicare (Gucciardi et al., 2009).

Those with low income tend to lack insurance coverage that covers expensive medications such

as those for CVD, which are among the most expensive within Canada (Booth et al., 2012;

Campbell et al., 2012). Booth et al. (2012) found an increase in diabetes related mortality rates

between those of high and low SES especially in those over the age of 65. Woodward et al.

(2015) revealed that CVD is associated with lower SES. A community-based study from Turkey

revealed that unhealthy diet was associated with lower SES (OR = 3.31) and lower education

(OR=4.48) (Simsek et al., 2013).

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 5

A lack of education can have profound effects in those with CVD. In developing countries, there

is often a gap in hypertension treatment for seniors due to lack of knowledge of what

hypertension is and preventative signs (Maurer & Ramos, 2015). Maurer & Ramos (2015) reveal

that low-cost treatment options for hypertension exist and could increase awareness in seniors.

Seniors of higher SES are associated with higher physical activity, greater nutritional habits and

lower risk of smoking compared to those of lower SES (Campbell et al., 2012). This means that

those of low SES are associated with increased use of healthcare services that have little impact

on poorer health outcomes and mortality (Campbell et al., 2012).

It's important to assess how determinants are measured. The studies referenced in this paper

directly evaluated income, education and CVD data utilizing census reports, self-reporting data

and medical records.

SES was measured using household income and level of education, any additional information

on education, income, and occupation was ascertained through questionnaires. For example, one

study measured income using the "median household income level of an individual’s

neighborhood of residence on 1, April, 2002 from the 2001 Canadian Census. Neighborhoods

were defined using small geographic units (dissemination areas) from Statistics Canada" (Booth

et al., 2012).

Woodward et al. (2015) measured education by using self-reported data, falling into one of three

groups. Group one had no completed education or completed only primary school. Group two

A lack of education can have profound effects in those with CVD. In developing countries, there

is often a gap in hypertension treatment for seniors due to lack of knowledge of what

hypertension is and preventative signs (Maurer & Ramos, 2015). Maurer & Ramos (2015) reveal

that low-cost treatment options for hypertension exist and could increase awareness in seniors.

Seniors of higher SES are associated with higher physical activity, greater nutritional habits and

lower risk of smoking compared to those of lower SES (Campbell et al., 2012). This means that

those of low SES are associated with increased use of healthcare services that have little impact

on poorer health outcomes and mortality (Campbell et al., 2012).

It's important to assess how determinants are measured. The studies referenced in this paper

directly evaluated income, education and CVD data utilizing census reports, self-reporting data

and medical records.

SES was measured using household income and level of education, any additional information

on education, income, and occupation was ascertained through questionnaires. For example, one

study measured income using the "median household income level of an individual’s

neighborhood of residence on 1, April, 2002 from the 2001 Canadian Census. Neighborhoods

were defined using small geographic units (dissemination areas) from Statistics Canada" (Booth

et al., 2012).

Woodward et al. (2015) measured education by using self-reported data, falling into one of three

groups. Group one had no completed education or completed only primary school. Group two

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 6

composed of people who completed secondary school; and lastly group three completed tertiary

education (university or college).

Booth et al. (2012) recorded "baseline CVD, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke, based on

relevant diagnostic codes from hospital discharge records. Co-morbidity was captured using

diagnostic codes listed in hospital records and physicians’ service claims from the year prior to

baseline to create distinct case-mix categories based on the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical

Groups case-mix system."

If blood pressure and cholesterol levels were used to determine CVD risk, they were obtained

using standard protocols as in Woodward et al. (2015) and Winkleby et al., (1992).

Specific Canadian Data

The CCHS is a cross-sectional study in Canada that measures rates of different health

outcomes in the country. The most recent complete survey data is from 2014. Based on the

survey design, the most efficient way to access the rates of CVD was by studying those who self-

reported having heart disease. Data was collected for those with heart disease and was then

compared to level of education and to person income. Only the data for those aged 55 to 79 was

analyzed.

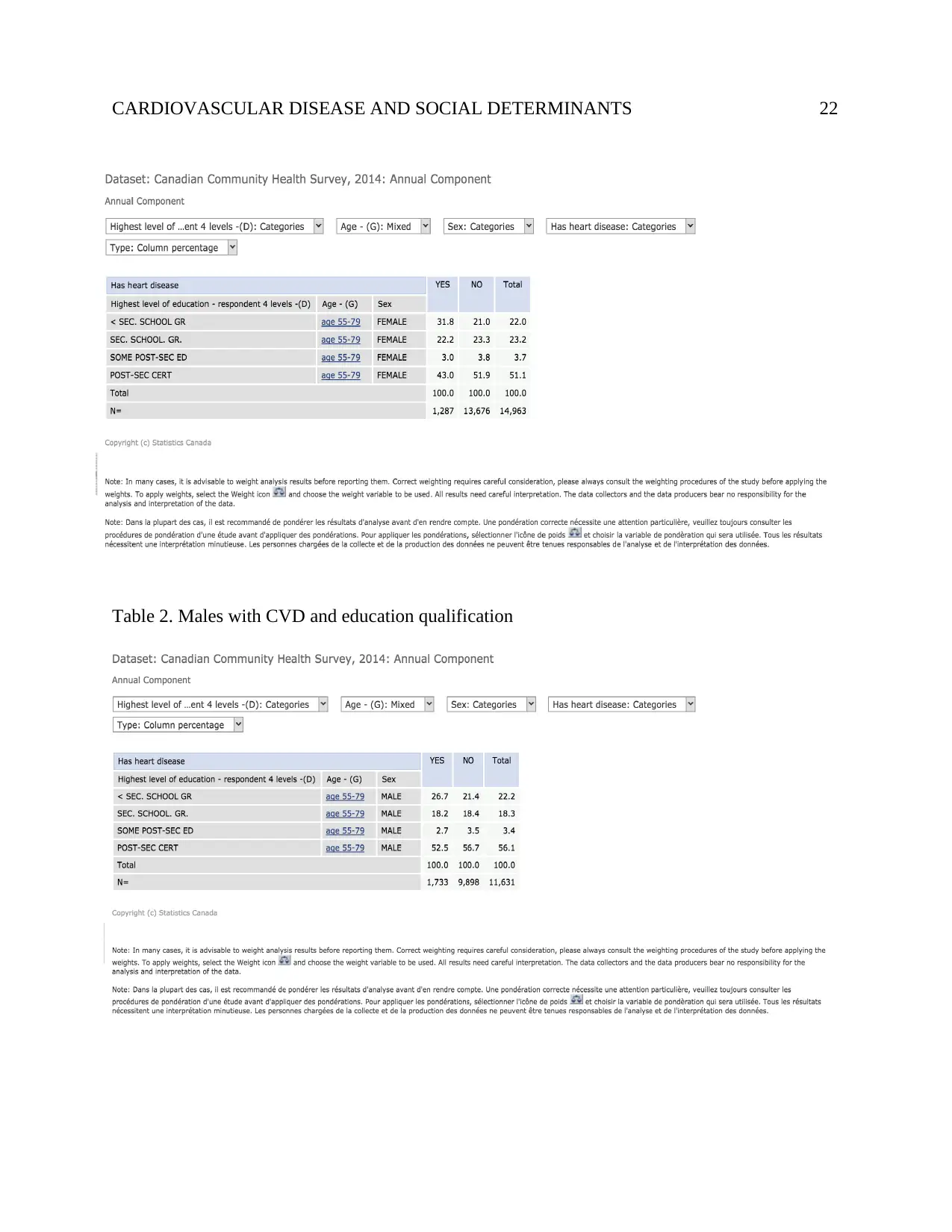

When studying the rates of heart disease in both older adult males and females it was

noted that the highest rates were in those that had completed post-secondary education followed

secondly by those who had not completed secondary education (Statistics Canada, 2016). It is

likely that there are confounding factors that create the high rates of heart disease in those with

composed of people who completed secondary school; and lastly group three completed tertiary

education (university or college).

Booth et al. (2012) recorded "baseline CVD, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke, based on

relevant diagnostic codes from hospital discharge records. Co-morbidity was captured using

diagnostic codes listed in hospital records and physicians’ service claims from the year prior to

baseline to create distinct case-mix categories based on the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical

Groups case-mix system."

If blood pressure and cholesterol levels were used to determine CVD risk, they were obtained

using standard protocols as in Woodward et al. (2015) and Winkleby et al., (1992).

Specific Canadian Data

The CCHS is a cross-sectional study in Canada that measures rates of different health

outcomes in the country. The most recent complete survey data is from 2014. Based on the

survey design, the most efficient way to access the rates of CVD was by studying those who self-

reported having heart disease. Data was collected for those with heart disease and was then

compared to level of education and to person income. Only the data for those aged 55 to 79 was

analyzed.

When studying the rates of heart disease in both older adult males and females it was

noted that the highest rates were in those that had completed post-secondary education followed

secondly by those who had not completed secondary education (Statistics Canada, 2016). It is

likely that there are confounding factors that create the high rates of heart disease in those with

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 7

the highest education level. In males, 26.7% of heart disease occurs in those with less than

secondary education, 18.2% in those who had completed secondary education, and only 2.7% of

those who had completed some post-secondary education (Statistics Canada, 2016). Similarly for

females, 31.8% of heart disease occurs in those with less than secondary education, 22.2% in

those who had completed secondary education, and only 3.0% of those who had completed some

post-secondary education (Statistics Canada, 2016). This data shows that to a certain extent, an

increase in education is correlated with a decrease in heart disease.

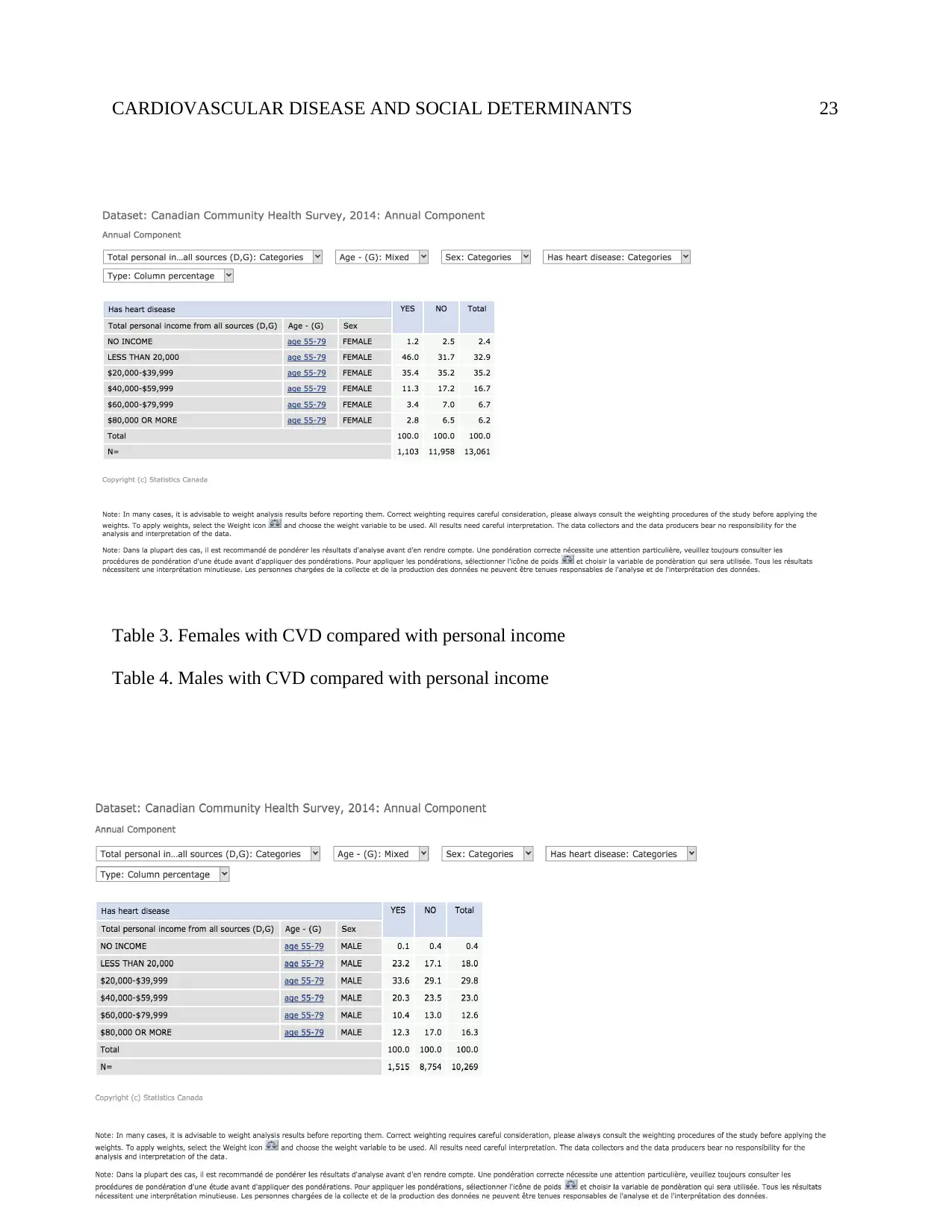

When comparing rates of heart disease to income levels it is found that those with

income rates less than $20,000 to $39,999 had significantly greater rates of heart disease

(Statistics Canada, 2016). For males, 23.2% of all heart disease occurs in those with less than

$20,000 income and 33.6% occurs among those with $20,000 to $39,000 income (Statistics

Canada, 2016). In females, 46% of all heart disease occurs in those with less than $20,000

income and 35.4% occurs among those with $20,000 to $39,000 income (Statistics Canada,

2016). In both male and female populations the rates continue to drop as income rises with rates

in the final category, income greater than $80,000, at 12.3% for males and 2.8% for females

(Statistics Canada, 2016). A very clear correlation can be noted between that of low income and

heart disease.

The Social Determinants of Health Model

The social determinants of health (SDOH) model (WHO, 2010) is the conceptual model

(refer to Appendix A) used to show how political, social and economic mechanisms strongly

the highest education level. In males, 26.7% of heart disease occurs in those with less than

secondary education, 18.2% in those who had completed secondary education, and only 2.7% of

those who had completed some post-secondary education (Statistics Canada, 2016). Similarly for

females, 31.8% of heart disease occurs in those with less than secondary education, 22.2% in

those who had completed secondary education, and only 3.0% of those who had completed some

post-secondary education (Statistics Canada, 2016). This data shows that to a certain extent, an

increase in education is correlated with a decrease in heart disease.

When comparing rates of heart disease to income levels it is found that those with

income rates less than $20,000 to $39,999 had significantly greater rates of heart disease

(Statistics Canada, 2016). For males, 23.2% of all heart disease occurs in those with less than

$20,000 income and 33.6% occurs among those with $20,000 to $39,000 income (Statistics

Canada, 2016). In females, 46% of all heart disease occurs in those with less than $20,000

income and 35.4% occurs among those with $20,000 to $39,000 income (Statistics Canada,

2016). In both male and female populations the rates continue to drop as income rises with rates

in the final category, income greater than $80,000, at 12.3% for males and 2.8% for females

(Statistics Canada, 2016). A very clear correlation can be noted between that of low income and

heart disease.

The Social Determinants of Health Model

The social determinants of health (SDOH) model (WHO, 2010) is the conceptual model

(refer to Appendix A) used to show how political, social and economic mechanisms strongly

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 8

influence an individual's’ socioeconomic position. In addition, there are three major factors

which influence an individual’s health, which are: material, psychosocial and biological and

behavioral factors (WHO, 2010). Material factors are things like housing, community

environment, and place of employment (WHO. 2010). Psychosocial factors are one’s family,

friends and social networks (WHO, 2010). Lastly, biological and behavioral factors are things

like lifestyle choices, genetics, nutrition, and personal health habits (WHO, 2010). All of these

factors affect an older adult’s ability to access health care and as a result influence their risk of

developing cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The SDOH model (WHO, 2010) specifically addresses the two determinants of health:

income and education which are related to an increase in CVD in older adults. Both income and

education fall under the category “material factors” because they are specifically related to

financial gain and the attainment of skill/s (WHO, 2010). Income is a major determinant of

health because it most directly measures material resources and also has a cumulative effect over

an individual’s life course as it’s the one socioeconomic indicator that can change the most

quickly, as income varies often (Havranek et al., 2015). Studies have shown that after

controlling other sociodemographic factors, there was a 40-50% decrease in mortality from CVD

with increasing family income (Havranek et al., 2015). The SDOH model discusses how several

factors result in low income increasing one’s risk of CVD and other illnesses, for example:

income inequality causes stress for those who make less money, resulting in poorer health;

income inequality results in fewer economic resources for poorer individuals resulting in less

influence an individual's’ socioeconomic position. In addition, there are three major factors

which influence an individual’s health, which are: material, psychosocial and biological and

behavioral factors (WHO, 2010). Material factors are things like housing, community

environment, and place of employment (WHO. 2010). Psychosocial factors are one’s family,

friends and social networks (WHO, 2010). Lastly, biological and behavioral factors are things

like lifestyle choices, genetics, nutrition, and personal health habits (WHO, 2010). All of these

factors affect an older adult’s ability to access health care and as a result influence their risk of

developing cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The SDOH model (WHO, 2010) specifically addresses the two determinants of health:

income and education which are related to an increase in CVD in older adults. Both income and

education fall under the category “material factors” because they are specifically related to

financial gain and the attainment of skill/s (WHO, 2010). Income is a major determinant of

health because it most directly measures material resources and also has a cumulative effect over

an individual’s life course as it’s the one socioeconomic indicator that can change the most

quickly, as income varies often (Havranek et al., 2015). Studies have shown that after

controlling other sociodemographic factors, there was a 40-50% decrease in mortality from CVD

with increasing family income (Havranek et al., 2015). The SDOH model discusses how several

factors result in low income increasing one’s risk of CVD and other illnesses, for example:

income inequality causes stress for those who make less money, resulting in poorer health;

income inequality results in fewer economic resources for poorer individuals resulting in less

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 9

treatment options; income inequality results in less money to invest in better social and economic

conditions leading to living in poorer neighborhoods and attending schools that are of lesser

quality resulting in poorer health outcomes (WHO, 2010).

Education is the second determinant of health that is linked with an increased risk of

CVD in older adults and the SDOH model addresses this as well (WHO, 2010). In Canada,

studies have shown a strong correlation between CVD and one’s level of education, CVD

morbidity and mortality rates have an increased risk when an individual has a lower level of

education (Kreatsoulas, 2010). Education is a life course determinant as it begins in early

childhood (influenced by one’s parents) and develops along the lifespan (WHO, 2010). The

knowledge and skills attained through education makes it easier to understand health messages

and make informed choices regarding health and well-being throughout one’s lifespan

(Kreatsoulas, 2010).

Overall, the SDOH model (Hosseini et al., 2017)) is able to show how the material

factors of both income and education are present as social determinants of health. When income

and education levels are reduced the risk of developing CVD is increased; on the contrary, when

income and education levels are higher, an older adult has a lifetime decreased risk of developing

CVD (Havranek et al., 2015).

Public Health Implications

treatment options; income inequality results in less money to invest in better social and economic

conditions leading to living in poorer neighborhoods and attending schools that are of lesser

quality resulting in poorer health outcomes (WHO, 2010).

Education is the second determinant of health that is linked with an increased risk of

CVD in older adults and the SDOH model addresses this as well (WHO, 2010). In Canada,

studies have shown a strong correlation between CVD and one’s level of education, CVD

morbidity and mortality rates have an increased risk when an individual has a lower level of

education (Kreatsoulas, 2010). Education is a life course determinant as it begins in early

childhood (influenced by one’s parents) and develops along the lifespan (WHO, 2010). The

knowledge and skills attained through education makes it easier to understand health messages

and make informed choices regarding health and well-being throughout one’s lifespan

(Kreatsoulas, 2010).

Overall, the SDOH model (Hosseini et al., 2017)) is able to show how the material

factors of both income and education are present as social determinants of health. When income

and education levels are reduced the risk of developing CVD is increased; on the contrary, when

income and education levels are higher, an older adult has a lifetime decreased risk of developing

CVD (Havranek et al., 2015).

Public Health Implications

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 10

Public Health interventions that target material factors (socioeconomic status and

education) from the Social Determinant of Health Model will help to decrease CVD in older

adults. Interventions that address socioeconomic status (SES) will uncover greater reasoning for

gaps in policies which will help to address physical activity, nutritional habits and smoking

habits (Campbell et al., 2012; Booth et al., 2012). Booth et al. (2012) suggests that interventions

that address SES will uncover that older adults with lower income are unable to pay for

expensive medications, especially due to lack of an insurance plans, thus policies need to address

this. Canadians with lower SES tend to use more healthcare services that have little impact on

CVD due to lack of income to obtain healthier lifestyle changes (Campbell et al., 2012).

Research suggests that there are gaps in awareness of pre-CVD symptoms and treatment (Joffres,

2013), especially within third world countries and low- middle income households (Maurer &

Ramos, 2015). Low-cost treatments exist for CVD management, but many older adults are

unaware of them (Maurer & Ramos, 2015). Many older adults are also unaware that they are

manifesting symptoms for CVD and interventions need to increase educational efforts especially

within small rural communities (Maurer & Ramos, 2015). Interventions that address the lack of

education to include incentives for healthcare professionals to screen older adults for

hypertension yearly will not only increase awareness but will also help to change unhealthy

behaviour (Maurer & Ramos, 2015; Campbell, 2012; Bloetzer et al., 2015). Research indicates

that plans for interventions have been made to increase CVD awareness in numerous countries,

Public Health interventions that target material factors (socioeconomic status and

education) from the Social Determinant of Health Model will help to decrease CVD in older

adults. Interventions that address socioeconomic status (SES) will uncover greater reasoning for

gaps in policies which will help to address physical activity, nutritional habits and smoking

habits (Campbell et al., 2012; Booth et al., 2012). Booth et al. (2012) suggests that interventions

that address SES will uncover that older adults with lower income are unable to pay for

expensive medications, especially due to lack of an insurance plans, thus policies need to address

this. Canadians with lower SES tend to use more healthcare services that have little impact on

CVD due to lack of income to obtain healthier lifestyle changes (Campbell et al., 2012).

Research suggests that there are gaps in awareness of pre-CVD symptoms and treatment (Joffres,

2013), especially within third world countries and low- middle income households (Maurer &

Ramos, 2015). Low-cost treatments exist for CVD management, but many older adults are

unaware of them (Maurer & Ramos, 2015). Many older adults are also unaware that they are

manifesting symptoms for CVD and interventions need to increase educational efforts especially

within small rural communities (Maurer & Ramos, 2015). Interventions that address the lack of

education to include incentives for healthcare professionals to screen older adults for

hypertension yearly will not only increase awareness but will also help to change unhealthy

behaviour (Maurer & Ramos, 2015; Campbell, 2012; Bloetzer et al., 2015). Research indicates

that plans for interventions have been made to increase CVD awareness in numerous countries,

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 11

but there seems to lack implementation and evaluation of programs (Maurer & Ramos, 2015;

Joffres et al., 2013).

England is leading in public health interventions by using government organizations to promote

and educate the public on the risk of salt and implementing a bonus payment initiative to general

practitioners to achieve targets for hypertension care (Joffres et al., 2013). The Public Health

Agency of Canada (PHAC) suggests that education efforts need to extend to hard to reach

populations such as Indigenous communities and healthcare professionals need to be conscience

of individuals who may not seem to be at risk (Campbell et al., 2012). The PHAC aso suggests

that policies need to be transparent and take an upstream approach through cabinet level

committees to include incentives for collaboration (Campbell et al., 2012).

Finland has implemented a sodium reduction strategy in 2010 that was very effective in treating

and controlling hypertension, reducing medical costs and preventing CVD disease earlier in

patients (Campbell et al., 2012). Policies that create supportive environments make healthy

choices easier by include reducing sodium in processed foods like Finland, restricting processed

trans fats, allowing low income households to afford healthy food and creating pricing policies to

restrict energy-dense foods (Campbell et al., 2012). Healthy interventions need to reflect

community needs (Campbell et al., 2012). Canada has implemented healthy food procurement

policies in public schools to remove soft drinks and junk food, but this could be taken a step

but there seems to lack implementation and evaluation of programs (Maurer & Ramos, 2015;

Joffres et al., 2013).

England is leading in public health interventions by using government organizations to promote

and educate the public on the risk of salt and implementing a bonus payment initiative to general

practitioners to achieve targets for hypertension care (Joffres et al., 2013). The Public Health

Agency of Canada (PHAC) suggests that education efforts need to extend to hard to reach

populations such as Indigenous communities and healthcare professionals need to be conscience

of individuals who may not seem to be at risk (Campbell et al., 2012). The PHAC aso suggests

that policies need to be transparent and take an upstream approach through cabinet level

committees to include incentives for collaboration (Campbell et al., 2012).

Finland has implemented a sodium reduction strategy in 2010 that was very effective in treating

and controlling hypertension, reducing medical costs and preventing CVD disease earlier in

patients (Campbell et al., 2012). Policies that create supportive environments make healthy

choices easier by include reducing sodium in processed foods like Finland, restricting processed

trans fats, allowing low income households to afford healthy food and creating pricing policies to

restrict energy-dense foods (Campbell et al., 2012). Healthy interventions need to reflect

community needs (Campbell et al., 2012). Canada has implemented healthy food procurement

policies in public schools to remove soft drinks and junk food, but this could be taken a step

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 12

further to implement this policy in health care facilities, workplaces, correctional institutions and

military bases (Campbell et al., 2012). The United Kingdom has implemented a total ban on junk

food ads during children’s programs and adult programs at peak watching times, which could

also be implemented in Canada to help prevent CVD earlier than in senior age (Campbell et al.,

2012).

Alternative programs not already discussed include community-linkage systems and

environmental approaches to prevent CVD. (Greenlund et al., 2012)

Greenlund et al., 2012, describe successful community programs such as the, Sickness

Prevention Achieved Through Regional Collaboration (SPARC) which coordinate with

community partners to deliver screening and preventative healthcare such as a set of

recommended immunization, cancer, and CVD screening services to older adults in places where

they can be easily accessed.

Environmental approaches include promoting healthy choices, availability, accessibility to

information, and resources for the entire population, not just high risk groups. For example the

Center for Disease Control (CDC) is working with restaurants and food manufactures to reduce

the amount of sodium in processed and restaurant foods. (Greenlund et al., 2012).

Historically these initiatives have been successful. In the past, government agencies and

the food industry have worked together to “address nutritional problems by fortifying foods with

minerals and vitamins (e.g., vitamin D fortification of milk to prevent rickets, niacin fortification

further to implement this policy in health care facilities, workplaces, correctional institutions and

military bases (Campbell et al., 2012). The United Kingdom has implemented a total ban on junk

food ads during children’s programs and adult programs at peak watching times, which could

also be implemented in Canada to help prevent CVD earlier than in senior age (Campbell et al.,

2012).

Alternative programs not already discussed include community-linkage systems and

environmental approaches to prevent CVD. (Greenlund et al., 2012)

Greenlund et al., 2012, describe successful community programs such as the, Sickness

Prevention Achieved Through Regional Collaboration (SPARC) which coordinate with

community partners to deliver screening and preventative healthcare such as a set of

recommended immunization, cancer, and CVD screening services to older adults in places where

they can be easily accessed.

Environmental approaches include promoting healthy choices, availability, accessibility to

information, and resources for the entire population, not just high risk groups. For example the

Center for Disease Control (CDC) is working with restaurants and food manufactures to reduce

the amount of sodium in processed and restaurant foods. (Greenlund et al., 2012).

Historically these initiatives have been successful. In the past, government agencies and

the food industry have worked together to “address nutritional problems by fortifying foods with

minerals and vitamins (e.g., vitamin D fortification of milk to prevent rickets, niacin fortification

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 13

of flour to prevent pellagra, and folic acid fortification of flour to prevent neural tube defects).”

(Greenlund et al., 2012).

Unfortunately these type of changes take time, lifestyle changes, and significant

resources and may require government subsidies to bring about change. The 2010 Healthy

Hunger-Free Kids Act costing approximately $10 billion annually (Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids

Act of 2010, n.d) is an example of a government initiative to reduce childhood obesity, a

preventative strategy against obesity, CVD, diabetes and various health related problems. The act

has both pros and cons and has been all but eliminated by the Trump administration. Successes

of the program include, “increased nutritional value, iron, calcium, vitamin A, vitamin C, and

protein nutrition” and decreased caloric intake, which benefited children with obesity (Cornish et

al., 2016). However the program also had its critics. Students complained about poor portion

sizes, bland food and a study published by the Harvard School of Public Health “discovered that

about 60 percent of vegetables and roughly 40 percent of fresh fruit are thrown away due to no

interest.” (Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, n.d)

Public health interventions are clearly beneficial for the reduced risk of CVD. It is imperative

that investments are made towards health education with a focus towards individuals from lower

income and socioeconomic households.

Conclusion and Summary

of flour to prevent pellagra, and folic acid fortification of flour to prevent neural tube defects).”

(Greenlund et al., 2012).

Unfortunately these type of changes take time, lifestyle changes, and significant

resources and may require government subsidies to bring about change. The 2010 Healthy

Hunger-Free Kids Act costing approximately $10 billion annually (Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids

Act of 2010, n.d) is an example of a government initiative to reduce childhood obesity, a

preventative strategy against obesity, CVD, diabetes and various health related problems. The act

has both pros and cons and has been all but eliminated by the Trump administration. Successes

of the program include, “increased nutritional value, iron, calcium, vitamin A, vitamin C, and

protein nutrition” and decreased caloric intake, which benefited children with obesity (Cornish et

al., 2016). However the program also had its critics. Students complained about poor portion

sizes, bland food and a study published by the Harvard School of Public Health “discovered that

about 60 percent of vegetables and roughly 40 percent of fresh fruit are thrown away due to no

interest.” (Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, n.d)

Public health interventions are clearly beneficial for the reduced risk of CVD. It is imperative

that investments are made towards health education with a focus towards individuals from lower

income and socioeconomic households.

Conclusion and Summary

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 14

Income and social determinants have generally determined the CVD prevalence in

Canada. It has been shown the CVD’s prevalence in high -income economies. Also, Canadians

with lower SES tend to use more healthcare services that have little impact on CVD due to lack

of income to obtain healthier lifestyle change. In Canada, it is expected that CVD will still be the

leading cause of death even by 2030. The CVD is a major issue in Canada since it accounts for

higher number of deaths than any other illness in the country. Because of the higher magnitude

of CVD in Canada, the studies are being directed towards the social determinants of health

(SDH). These are the risk factors “causes of causes”). Thus Canada wants to control the impacts

of social environment on people sharing a community as mechanism to reduce CVD prevalence.

The implications of this study is that Public Health interventions that target material factors

(socioeconomic status and education) from the Social Determinant of Health Model will help

decrease CVD in older adults. The future study should focus on interventions that address

socioeconomic status (SES) to uncover greater reasoning for gaps in policies. This will help

address physical activity, nutritional habits and smoking habits.

Income and social determinants have generally determined the CVD prevalence in

Canada. It has been shown the CVD’s prevalence in high -income economies. Also, Canadians

with lower SES tend to use more healthcare services that have little impact on CVD due to lack

of income to obtain healthier lifestyle change. In Canada, it is expected that CVD will still be the

leading cause of death even by 2030. The CVD is a major issue in Canada since it accounts for

higher number of deaths than any other illness in the country. Because of the higher magnitude

of CVD in Canada, the studies are being directed towards the social determinants of health

(SDH). These are the risk factors “causes of causes”). Thus Canada wants to control the impacts

of social environment on people sharing a community as mechanism to reduce CVD prevalence.

The implications of this study is that Public Health interventions that target material factors

(socioeconomic status and education) from the Social Determinant of Health Model will help

decrease CVD in older adults. The future study should focus on interventions that address

socioeconomic status (SES) to uncover greater reasoning for gaps in policies. This will help

address physical activity, nutritional habits and smoking habits.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 15

References

American Heart Association. (2016). Statistical Fact Sheet 2016 Update: Older Americans &

Cardiovascular Diseases. Retrieved from https://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-

public/@wcm/@sop/@smd/documents/downloadable/ucm_483970.pdf

Havranek, E. P., Mujahid, M. S., Barr, D. A., Blair, I. V., Cohen, M. S., Cruz-Flores, S., & ...

Yancy, C. W. (2015). Social Determinants of Risk and Outcomes for

Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation, 132(9), 873-898.

doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228

Hosseini, S., Arab, M., Emamgholipour, S., Rashidian, A., Monterzari A., & Zaboli, R. (2017).

Conceptual Models of Social Determinants of Health: A Narrative Review. Iranian

Journal of Public Health, 46(4), 435–446.

Kreatsoulas, C., & Anand, S. S. (2010). The impact of social determinants on cardiovascular

disease. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 26(Suppl C), 8C–13C.

References

American Heart Association. (2016). Statistical Fact Sheet 2016 Update: Older Americans &

Cardiovascular Diseases. Retrieved from https://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-

public/@wcm/@sop/@smd/documents/downloadable/ucm_483970.pdf

Havranek, E. P., Mujahid, M. S., Barr, D. A., Blair, I. V., Cohen, M. S., Cruz-Flores, S., & ...

Yancy, C. W. (2015). Social Determinants of Risk and Outcomes for

Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation, 132(9), 873-898.

doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228

Hosseini, S., Arab, M., Emamgholipour, S., Rashidian, A., Monterzari A., & Zaboli, R. (2017).

Conceptual Models of Social Determinants of Health: A Narrative Review. Iranian

Journal of Public Health, 46(4), 435–446.

Kreatsoulas, C., & Anand, S. S. (2010). The impact of social determinants on cardiovascular

disease. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 26(Suppl C), 8C–13C.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 16

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2017a). Canadian chronic disease surveillance system

methods report abridged version for v2015 and v2016 (Dementia, Including Alzheimer’s

Disease). Retrieved from

https://infobase.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ccdss-scsmc/data-tool/Methods

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2017b). The 2017 Canadian chronic disease indicators.

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada Research, Policy and

Practice, 37(8), 248-251. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-

aspc/documents/services/publications/health-promotion-chronic-disease-prevention-

canada-research-policy-practice/vol-37-no-8-2017/ar-03-eng.pdf

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2017c). Public health infobase: Canadian Chronic Disease

Surveillance System (CCDSS). Retrieved from https://infobase.phac-aspc.gc.ca/CCDSS-

SCSMC/data-tool/?

l=eng&HRs=00&DDLV=CDSAMI&DDLM=ASIR&1=M&2=F&DDLFrm=1999&DD

LTo=2012&=10&VIEW=2

Raphael, D. (2016). Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives. Toronto: Canadian

Scholars Press Inc.

Statistics Canada. (2016). Canadian Community Health Survey – Annual Component (CCHS).

Retrieved from http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?

Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3226

World Health Organization (WHO) 2010. A conceptual model framework for action on the

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2017a). Canadian chronic disease surveillance system

methods report abridged version for v2015 and v2016 (Dementia, Including Alzheimer’s

Disease). Retrieved from

https://infobase.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ccdss-scsmc/data-tool/Methods

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2017b). The 2017 Canadian chronic disease indicators.

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada Research, Policy and

Practice, 37(8), 248-251. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-

aspc/documents/services/publications/health-promotion-chronic-disease-prevention-

canada-research-policy-practice/vol-37-no-8-2017/ar-03-eng.pdf

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2017c). Public health infobase: Canadian Chronic Disease

Surveillance System (CCDSS). Retrieved from https://infobase.phac-aspc.gc.ca/CCDSS-

SCSMC/data-tool/?

l=eng&HRs=00&DDLV=CDSAMI&DDLM=ASIR&1=M&2=F&DDLFrm=1999&DD

LTo=2012&=10&VIEW=2

Raphael, D. (2016). Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives. Toronto: Canadian

Scholars Press Inc.

Statistics Canada. (2016). Canadian Community Health Survey – Annual Component (CCHS).

Retrieved from http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?

Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3226

World Health Organization (WHO) 2010. A conceptual model framework for action on the

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 17

Social determinants of health. Retrieved

from:http://www.who.int/social_determinants/corner/SDHDP2.pdf page 9

World Health Organization. (2017). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Retrieved from

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/

Table 1, 2 Statistics Canada. (2016). Canadian Community Health Survey, 2014: Annual

component [public-use microdata file]. Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada. Health Statistics

Division, Data Liberation Initiative [producer and distributor]. Retrieved From

http://odesi1.scholarsportal.info.ezproxy.lakeheadu.ca/webview/index.jsp?object=http%3A%2F

%2F142.150.190.11%3A80%2Fobj%2FfStudy%2Fcchs-82M0013-E-2014-Annual-

component&headers=http%3A%2F%2F142.150.190.11%3A80%2Fobj%2FfVariable%2Fcchs-

82M0013-E-2014-Annual-component_V100

Table 3, 4 Statistics Canada. (2016). Canadian Community Health Survey, 2014: Annual

component [public-use microdata file]. Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada. Health Statistics

Division, Data Liberation Initiative [producer and distributor]. Retrieved From

http://odesi1.scholarsportal.info.ezproxy.lakeheadu.ca/webview/index.jsp?object=http%3A%2F

Social determinants of health. Retrieved

from:http://www.who.int/social_determinants/corner/SDHDP2.pdf page 9

World Health Organization. (2017). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Retrieved from

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/

Table 1, 2 Statistics Canada. (2016). Canadian Community Health Survey, 2014: Annual

component [public-use microdata file]. Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada. Health Statistics

Division, Data Liberation Initiative [producer and distributor]. Retrieved From

http://odesi1.scholarsportal.info.ezproxy.lakeheadu.ca/webview/index.jsp?object=http%3A%2F

%2F142.150.190.11%3A80%2Fobj%2FfStudy%2Fcchs-82M0013-E-2014-Annual-

component&headers=http%3A%2F%2F142.150.190.11%3A80%2Fobj%2FfVariable%2Fcchs-

82M0013-E-2014-Annual-component_V100

Table 3, 4 Statistics Canada. (2016). Canadian Community Health Survey, 2014: Annual

component [public-use microdata file]. Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada. Health Statistics

Division, Data Liberation Initiative [producer and distributor]. Retrieved From

http://odesi1.scholarsportal.info.ezproxy.lakeheadu.ca/webview/index.jsp?object=http%3A%2F

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 18

%2F142.150.190.11%3A80%2Fobj%2FfStudy%2Fcchs-82M0013-E-2014-Annual-

component&headers=http%3A%2F%2F142.150.190.11%3A80%2Fobj%2FfVariable%2Fcchs-

82M0013-E-2014-Annual-component_V100

%2F142.150.190.11%3A80%2Fobj%2FfStudy%2Fcchs-82M0013-E-2014-Annual-

component&headers=http%3A%2F%2F142.150.190.11%3A80%2Fobj%2FfVariable%2Fcchs-

82M0013-E-2014-Annual-component_V100

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 19

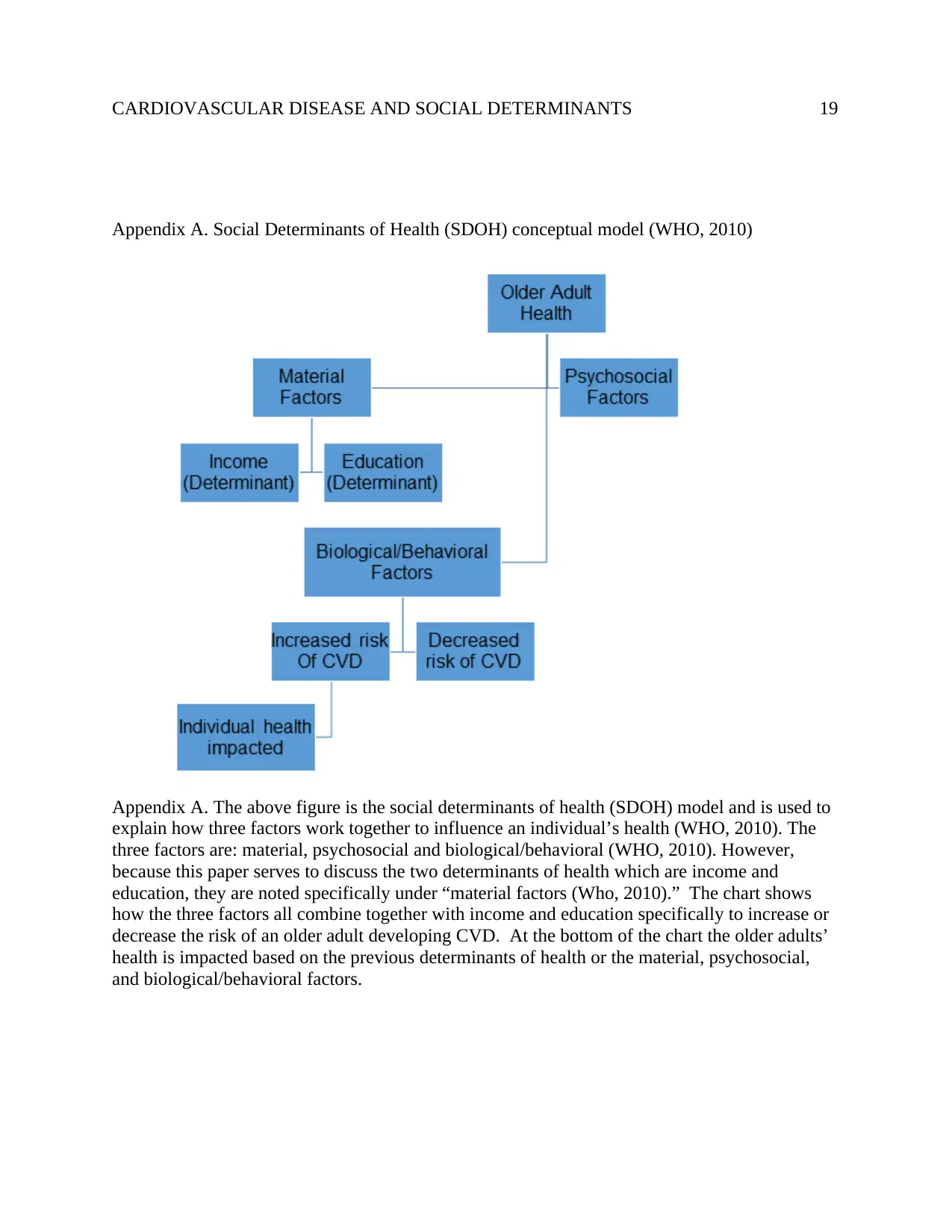

Appendix A. Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) conceptual model (WHO, 2010)

Appendix A. The above figure is the social determinants of health (SDOH) model and is used to

explain how three factors work together to influence an individual’s health (WHO, 2010). The

three factors are: material, psychosocial and biological/behavioral (WHO, 2010). However,

because this paper serves to discuss the two determinants of health which are income and

education, they are noted specifically under “material factors (Who, 2010).” The chart shows

how the three factors all combine together with income and education specifically to increase or

decrease the risk of an older adult developing CVD. At the bottom of the chart the older adults’

health is impacted based on the previous determinants of health or the material, psychosocial,

and biological/behavioral factors.

Appendix A. Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) conceptual model (WHO, 2010)

Appendix A. The above figure is the social determinants of health (SDOH) model and is used to

explain how three factors work together to influence an individual’s health (WHO, 2010). The

three factors are: material, psychosocial and biological/behavioral (WHO, 2010). However,

because this paper serves to discuss the two determinants of health which are income and

education, they are noted specifically under “material factors (Who, 2010).” The chart shows

how the three factors all combine together with income and education specifically to increase or

decrease the risk of an older adult developing CVD. At the bottom of the chart the older adults’

health is impacted based on the previous determinants of health or the material, psychosocial,

and biological/behavioral factors.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 20

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 21

Tables

Table 1. Females with CVD and education qualification

Tables

Table 1. Females with CVD and education qualification

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 22

Table 2. Males with CVD and education qualification

Table 2. Males with CVD and education qualification

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS 23

Table 3. Females with CVD compared with personal income

Table 4. Males with CVD compared with personal income

Table 3. Females with CVD compared with personal income

Table 4. Males with CVD compared with personal income

1 out of 23

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.