PSYC105 Report: Road Safety Analysis - Cell Phones & Driving 2018

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/05

|11

|4556

|457

Report

AI Summary

This PSYC105 report investigates the impact of cell phone use, specifically talking and texting while driving, on road safety in Western Australia. The study utilizes a survey administered to young drivers, focusing on their driving experience, mobile phone habits, and attitudes towards safety messages. The research tests three hypotheses related to gain-framed versus loss-framed safety messages and the influence of issue involvement on intentions to engage in unsafe driving behaviors. Statistical analysis, including t-tests, is employed to evaluate the hypotheses, with findings discussed in terms of their implications for road safety interventions. The report provides demographic data on the respondents and details the frequency of cell phone use while driving, along with an assessment of cell phone addiction rates within the sample population.

RUNNING HEAD: PSYC105 REPORT 2018 1

PSYC105 Report 2018

Name

Institution

PSYC105 Report 2018

Name

Institution

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

PSYC105 REPORT 2018 2

PSYC105 report 2018

Introduction

Road transport, in the 21st century, is an obviously dangerous mode of transportation compared to

others like railways, air, and light rail, water. Cell phone distraction remains a major topic of interest

relative to increasing road carnage. Notwithstanding all the expensive campaigns and the media attention

designed for lowering the incidents, the statistics are shocking, with teens and young adults being the

most affected. People adore their smartphones (Miller & Miller, 2000). They can converse on the phone,

text, take photos and videos, check emails, access internet and do pretty much everything they used to do

using a clunky desktop computer (Cazzulino, Burke, Muller, Arbogast and Upperman, 2014). What

transpires when the cell phone addiction is escalated behind the wheel? This research investigated how

texting and phone calls while driving affected road safety in Western Australia, with the overall research

question: How do ordinary cell phones affect road safety? Besides, the study recommended some

measures to be adopted by the Australian government to curb the menace.

Research Method

The survey was randomly administered to the target participants from 1st-15th, September 2018

using Qualtrics® software. Initially, the survey was sent to 892 teens and young adult drivers, but only

343 responses were considered to be appropriate for use as the rest were incomplete. The 343 recorded

responses had met the screening standards: learners were not more than 26 years old, had a driver’s

license/permit, drove frequently and owned. The survey items were tested for reliability, and validity

using Cronbach’s alpha for each of the 15 constructs in the model.

Results

Descriptive statistics analysis that is mean, standard deviation, frequencies, range minimum and

maximum values and confidence intervals were completed SPSS (using Statistical Package for the Social

Sciences) version 22.0.

Demographics

PSYC105 report 2018

Introduction

Road transport, in the 21st century, is an obviously dangerous mode of transportation compared to

others like railways, air, and light rail, water. Cell phone distraction remains a major topic of interest

relative to increasing road carnage. Notwithstanding all the expensive campaigns and the media attention

designed for lowering the incidents, the statistics are shocking, with teens and young adults being the

most affected. People adore their smartphones (Miller & Miller, 2000). They can converse on the phone,

text, take photos and videos, check emails, access internet and do pretty much everything they used to do

using a clunky desktop computer (Cazzulino, Burke, Muller, Arbogast and Upperman, 2014). What

transpires when the cell phone addiction is escalated behind the wheel? This research investigated how

texting and phone calls while driving affected road safety in Western Australia, with the overall research

question: How do ordinary cell phones affect road safety? Besides, the study recommended some

measures to be adopted by the Australian government to curb the menace.

Research Method

The survey was randomly administered to the target participants from 1st-15th, September 2018

using Qualtrics® software. Initially, the survey was sent to 892 teens and young adult drivers, but only

343 responses were considered to be appropriate for use as the rest were incomplete. The 343 recorded

responses had met the screening standards: learners were not more than 26 years old, had a driver’s

license/permit, drove frequently and owned. The survey items were tested for reliability, and validity

using Cronbach’s alpha for each of the 15 constructs in the model.

Results

Descriptive statistics analysis that is mean, standard deviation, frequencies, range minimum and

maximum values and confidence intervals were completed SPSS (using Statistical Package for the Social

Sciences) version 22.0.

Demographics

PSYC105 REPORT 2018 3

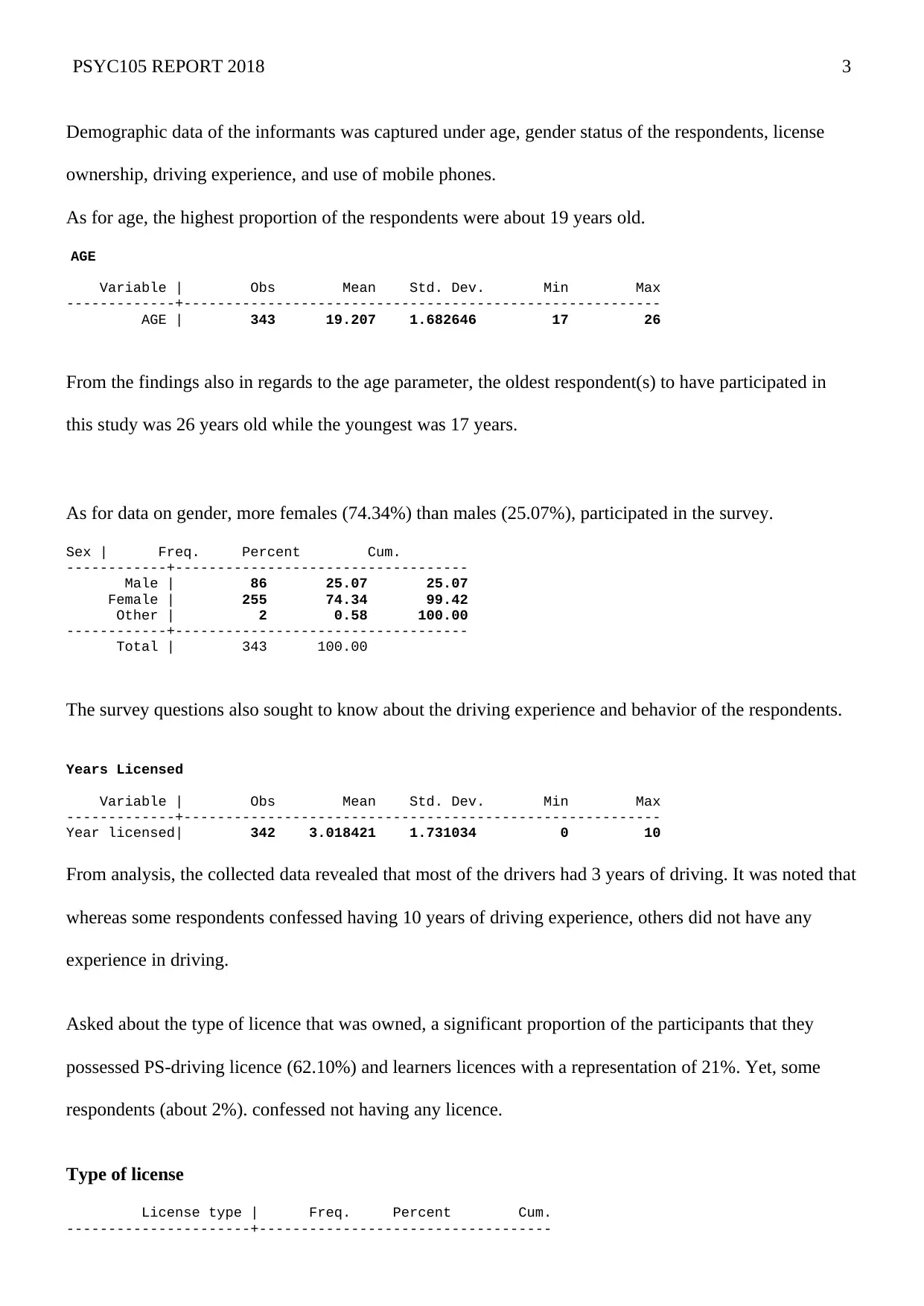

Demographic data of the informants was captured under age, gender status of the respondents, license

ownership, driving experience, and use of mobile phones.

As for age, the highest proportion of the respondents were about 19 years old.

AGE

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Dev. Min Max

-------------+---------------------------------------------------------

AGE | 343 19.207 1.682646 17 26

From the findings also in regards to the age parameter, the oldest respondent(s) to have participated in

this study was 26 years old while the youngest was 17 years.

As for data on gender, more females (74.34%) than males (25.07%), participated in the survey.

Sex | Freq. Percent Cum.

------------+-----------------------------------

Male | 86 25.07 25.07

Female | 255 74.34 99.42

Other | 2 0.58 100.00

------------+-----------------------------------

Total | 343 100.00

The survey questions also sought to know about the driving experience and behavior of the respondents.

Years Licensed

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Dev. Min Max

-------------+---------------------------------------------------------

Year licensed| 342 3.018421 1.731034 0 10

From analysis, the collected data revealed that most of the drivers had 3 years of driving. It was noted that

whereas some respondents confessed having 10 years of driving experience, others did not have any

experience in driving.

Asked about the type of licence that was owned, a significant proportion of the participants that they

possessed PS-driving licence (62.10%) and learners licences with a representation of 21%. Yet, some

respondents (about 2%). confessed not having any licence.

Type of license

License type | Freq. Percent Cum.

----------------------+-----------------------------------

Demographic data of the informants was captured under age, gender status of the respondents, license

ownership, driving experience, and use of mobile phones.

As for age, the highest proportion of the respondents were about 19 years old.

AGE

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Dev. Min Max

-------------+---------------------------------------------------------

AGE | 343 19.207 1.682646 17 26

From the findings also in regards to the age parameter, the oldest respondent(s) to have participated in

this study was 26 years old while the youngest was 17 years.

As for data on gender, more females (74.34%) than males (25.07%), participated in the survey.

Sex | Freq. Percent Cum.

------------+-----------------------------------

Male | 86 25.07 25.07

Female | 255 74.34 99.42

Other | 2 0.58 100.00

------------+-----------------------------------

Total | 343 100.00

The survey questions also sought to know about the driving experience and behavior of the respondents.

Years Licensed

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Dev. Min Max

-------------+---------------------------------------------------------

Year licensed| 342 3.018421 1.731034 0 10

From analysis, the collected data revealed that most of the drivers had 3 years of driving. It was noted that

whereas some respondents confessed having 10 years of driving experience, others did not have any

experience in driving.

Asked about the type of licence that was owned, a significant proportion of the participants that they

possessed PS-driving licence (62.10%) and learners licences with a representation of 21%. Yet, some

respondents (about 2%). confessed not having any licence.

Type of license

License type | Freq. Percent Cum.

----------------------+-----------------------------------

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

PSYC105 REPORT 2018 4

None | 6 1.75 1.75

Learners | 74 21.57 23.32

Ps | 213 62.10 85.42

Full or heavy vehicle | 43 12.54 97.96

Motorcycle | 7 2.04 100.00

----------------------+-----------------------------------

Total | 343 100.00

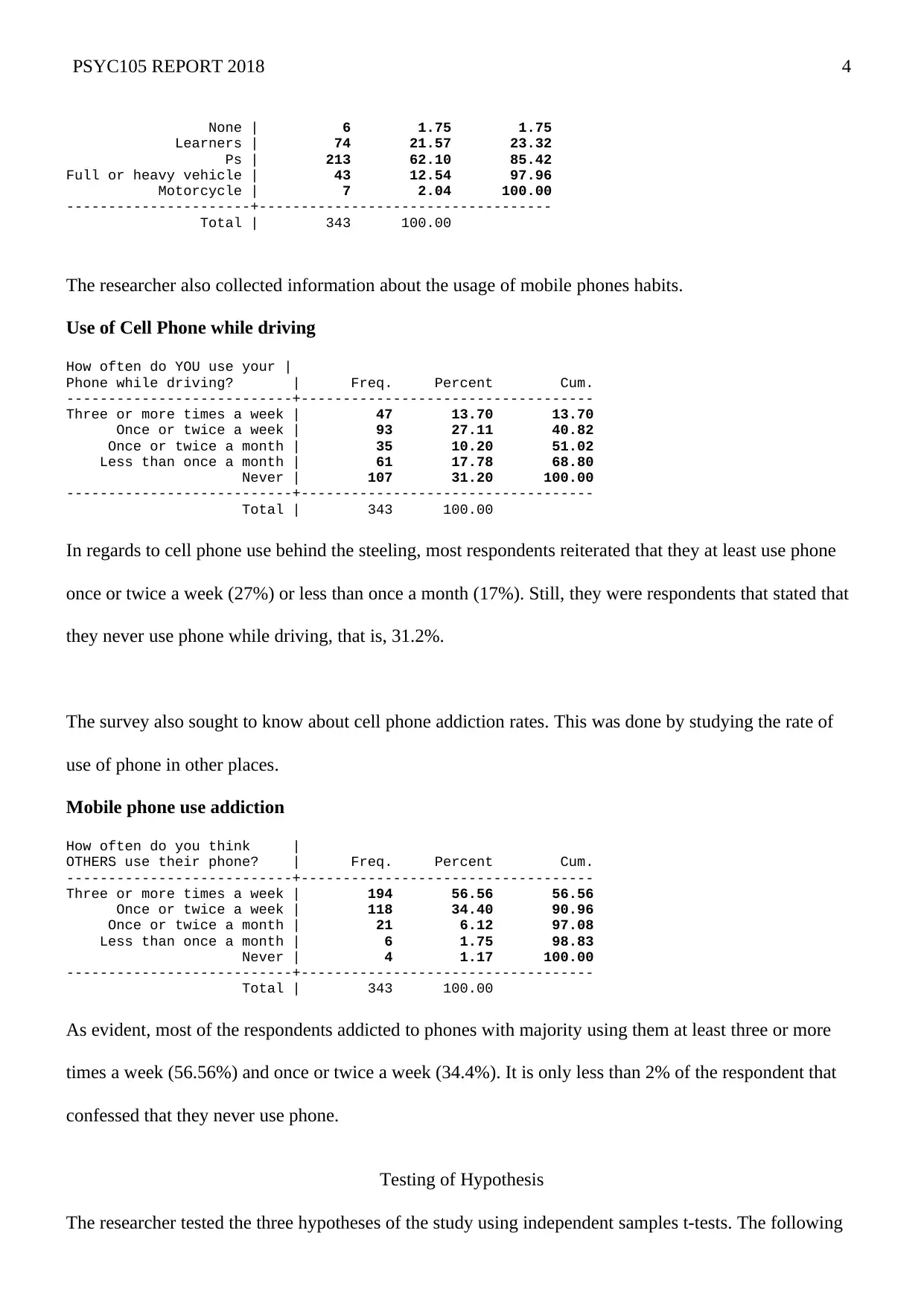

The researcher also collected information about the usage of mobile phones habits.

Use of Cell Phone while driving

How often do YOU use your |

Phone while driving? | Freq. Percent Cum.

---------------------------+-----------------------------------

Three or more times a week | 47 13.70 13.70

Once or twice a week | 93 27.11 40.82

Once or twice a month | 35 10.20 51.02

Less than once a month | 61 17.78 68.80

Never | 107 31.20 100.00

---------------------------+-----------------------------------

Total | 343 100.00

In regards to cell phone use behind the steeling, most respondents reiterated that they at least use phone

once or twice a week (27%) or less than once a month (17%). Still, they were respondents that stated that

they never use phone while driving, that is, 31.2%.

The survey also sought to know about cell phone addiction rates. This was done by studying the rate of

use of phone in other places.

Mobile phone use addiction

How often do you think |

OTHERS use their phone? | Freq. Percent Cum.

---------------------------+-----------------------------------

Three or more times a week | 194 56.56 56.56

Once or twice a week | 118 34.40 90.96

Once or twice a month | 21 6.12 97.08

Less than once a month | 6 1.75 98.83

Never | 4 1.17 100.00

---------------------------+-----------------------------------

Total | 343 100.00

As evident, most of the respondents addicted to phones with majority using them at least three or more

times a week (56.56%) and once or twice a week (34.4%). It is only less than 2% of the respondent that

confessed that they never use phone.

Testing of Hypothesis

The researcher tested the three hypotheses of the study using independent samples t-tests. The following

None | 6 1.75 1.75

Learners | 74 21.57 23.32

Ps | 213 62.10 85.42

Full or heavy vehicle | 43 12.54 97.96

Motorcycle | 7 2.04 100.00

----------------------+-----------------------------------

Total | 343 100.00

The researcher also collected information about the usage of mobile phones habits.

Use of Cell Phone while driving

How often do YOU use your |

Phone while driving? | Freq. Percent Cum.

---------------------------+-----------------------------------

Three or more times a week | 47 13.70 13.70

Once or twice a week | 93 27.11 40.82

Once or twice a month | 35 10.20 51.02

Less than once a month | 61 17.78 68.80

Never | 107 31.20 100.00

---------------------------+-----------------------------------

Total | 343 100.00

In regards to cell phone use behind the steeling, most respondents reiterated that they at least use phone

once or twice a week (27%) or less than once a month (17%). Still, they were respondents that stated that

they never use phone while driving, that is, 31.2%.

The survey also sought to know about cell phone addiction rates. This was done by studying the rate of

use of phone in other places.

Mobile phone use addiction

How often do you think |

OTHERS use their phone? | Freq. Percent Cum.

---------------------------+-----------------------------------

Three or more times a week | 194 56.56 56.56

Once or twice a week | 118 34.40 90.96

Once or twice a month | 21 6.12 97.08

Less than once a month | 6 1.75 98.83

Never | 4 1.17 100.00

---------------------------+-----------------------------------

Total | 343 100.00

As evident, most of the respondents addicted to phones with majority using them at least three or more

times a week (56.56%) and once or twice a week (34.4%). It is only less than 2% of the respondent that

confessed that they never use phone.

Testing of Hypothesis

The researcher tested the three hypotheses of the study using independent samples t-tests. The following

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

PSYC105 REPORT 2018 5

section details the results of the analysis.

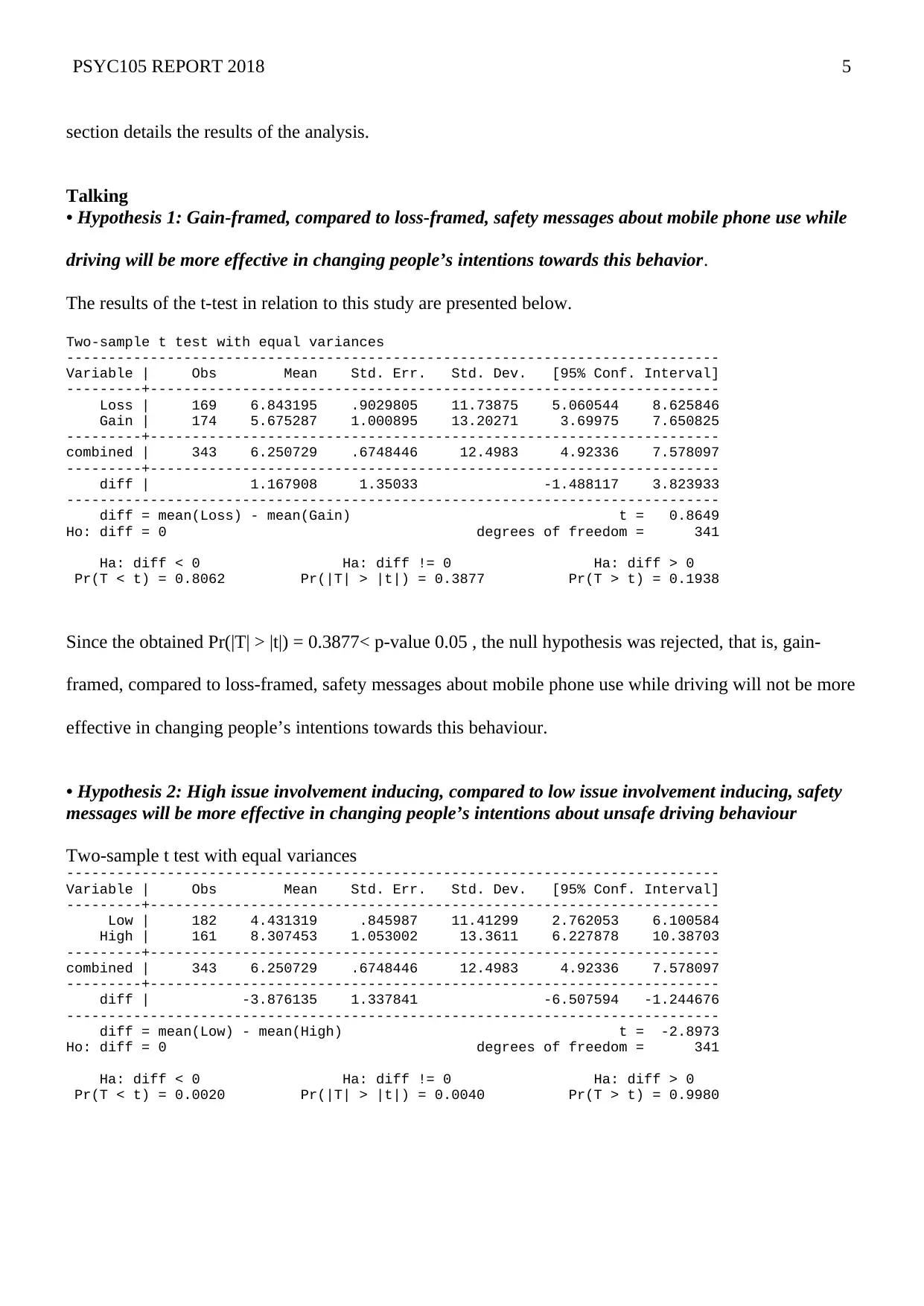

Talking

• Hypothesis 1: Gain-framed, compared to loss-framed, safety messages about mobile phone use while

driving will be more effective in changing people’s intentions towards this behavior.

The results of the t-test in relation to this study are presented below.

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Loss | 169 6.843195 .9029805 11.73875 5.060544 8.625846

Gain | 174 5.675287 1.000895 13.20271 3.69975 7.650825

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 343 6.250729 .6748446 12.4983 4.92336 7.578097

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | 1.167908 1.35033 -1.488117 3.823933

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Loss) - mean(Gain) t = 0.8649

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 341

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.8062 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.3877 Pr(T > t) = 0.1938

Since the obtained Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.3877< p-value 0.05 , the null hypothesis was rejected, that is, gain-

framed, compared to loss-framed, safety messages about mobile phone use while driving will not be more

effective in changing people’s intentions towards this behaviour.

• Hypothesis 2: High issue involvement inducing, compared to low issue involvement inducing, safety

messages will be more effective in changing people’s intentions about unsafe driving behaviour

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Low | 182 4.431319 .845987 11.41299 2.762053 6.100584

High | 161 8.307453 1.053002 13.3611 6.227878 10.38703

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 343 6.250729 .6748446 12.4983 4.92336 7.578097

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | -3.876135 1.337841 -6.507594 -1.244676

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Low) - mean(High) t = -2.8973

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 341

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.0020 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.0040 Pr(T > t) = 0.9980

section details the results of the analysis.

Talking

• Hypothesis 1: Gain-framed, compared to loss-framed, safety messages about mobile phone use while

driving will be more effective in changing people’s intentions towards this behavior.

The results of the t-test in relation to this study are presented below.

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Loss | 169 6.843195 .9029805 11.73875 5.060544 8.625846

Gain | 174 5.675287 1.000895 13.20271 3.69975 7.650825

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 343 6.250729 .6748446 12.4983 4.92336 7.578097

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | 1.167908 1.35033 -1.488117 3.823933

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Loss) - mean(Gain) t = 0.8649

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 341

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.8062 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.3877 Pr(T > t) = 0.1938

Since the obtained Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.3877< p-value 0.05 , the null hypothesis was rejected, that is, gain-

framed, compared to loss-framed, safety messages about mobile phone use while driving will not be more

effective in changing people’s intentions towards this behaviour.

• Hypothesis 2: High issue involvement inducing, compared to low issue involvement inducing, safety

messages will be more effective in changing people’s intentions about unsafe driving behaviour

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Low | 182 4.431319 .845987 11.41299 2.762053 6.100584

High | 161 8.307453 1.053002 13.3611 6.227878 10.38703

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 343 6.250729 .6748446 12.4983 4.92336 7.578097

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | -3.876135 1.337841 -6.507594 -1.244676

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Low) - mean(High) t = -2.8973

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 341

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.0020 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.0040 Pr(T > t) = 0.9980

PSYC105 REPORT 2018 6

From the results, Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.0040 < p-value 0.05 hence the null objective was rejected, that is, high

issue involvement inducing, compared to low issue involvement inducing, safety messages will not be

more effective in changing people’s intentions about unsafe driving behaviour.

• Hypothesis 3: Gain-framed safety messages about mobile phone use will be most effective when

paired with a high issue involvement inducing message

This hypothesis was subsequently tested as shown below.

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Loss | 81 8.37037 1.399095 12.59186 5.586082 11.15466

Gain | 80 8.24375 1.585037 14.177 5.088813 11.39869

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 161 8.307453 1.053002 13.3611 6.227878 10.38703

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | .1266204 2.112633 -4.045822 4.299063

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Loss) - mean(Gain) t = 0.0599

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 159

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.5239 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.9523 Pr(T > t) = 0.4761

Since the Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.9523 > p-value 0.05, the null hypothesis was accepted, that is, gain-framed

safety messages about mobile phone use will be most effective when paired with a high issue

involvement inducing message.

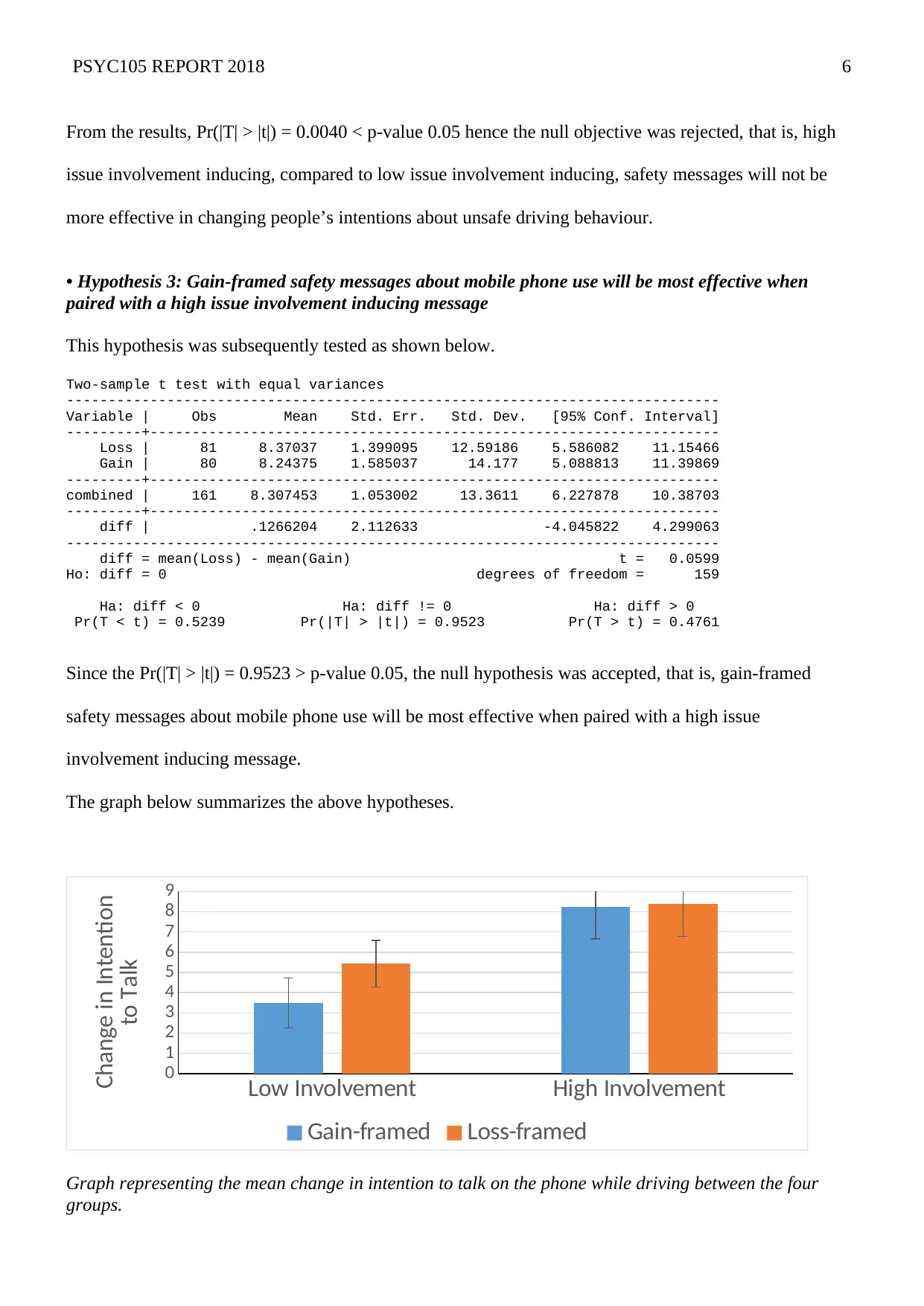

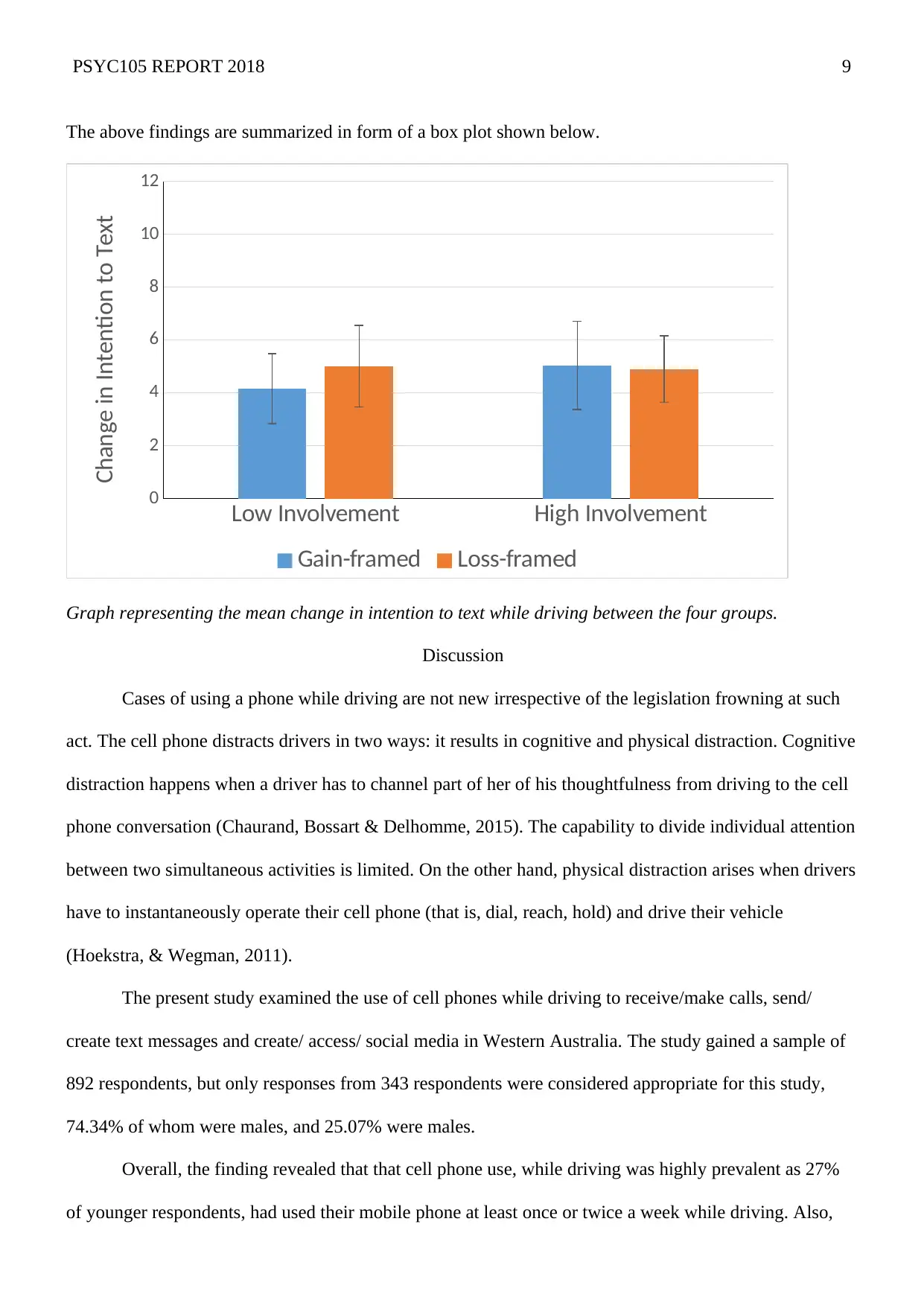

The graph below summarizes the above hypotheses.

Low Involvement High Involvement

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Gain-framed Loss-framed

Change in Intention

to Talk

Graph representing the mean change in intention to talk on the phone while driving between the four

groups.

From the results, Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.0040 < p-value 0.05 hence the null objective was rejected, that is, high

issue involvement inducing, compared to low issue involvement inducing, safety messages will not be

more effective in changing people’s intentions about unsafe driving behaviour.

• Hypothesis 3: Gain-framed safety messages about mobile phone use will be most effective when

paired with a high issue involvement inducing message

This hypothesis was subsequently tested as shown below.

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Loss | 81 8.37037 1.399095 12.59186 5.586082 11.15466

Gain | 80 8.24375 1.585037 14.177 5.088813 11.39869

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 161 8.307453 1.053002 13.3611 6.227878 10.38703

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | .1266204 2.112633 -4.045822 4.299063

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Loss) - mean(Gain) t = 0.0599

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 159

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.5239 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.9523 Pr(T > t) = 0.4761

Since the Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.9523 > p-value 0.05, the null hypothesis was accepted, that is, gain-framed

safety messages about mobile phone use will be most effective when paired with a high issue

involvement inducing message.

The graph below summarizes the above hypotheses.

Low Involvement High Involvement

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Gain-framed Loss-framed

Change in Intention

to Talk

Graph representing the mean change in intention to talk on the phone while driving between the four

groups.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

PSYC105 REPORT 2018 7

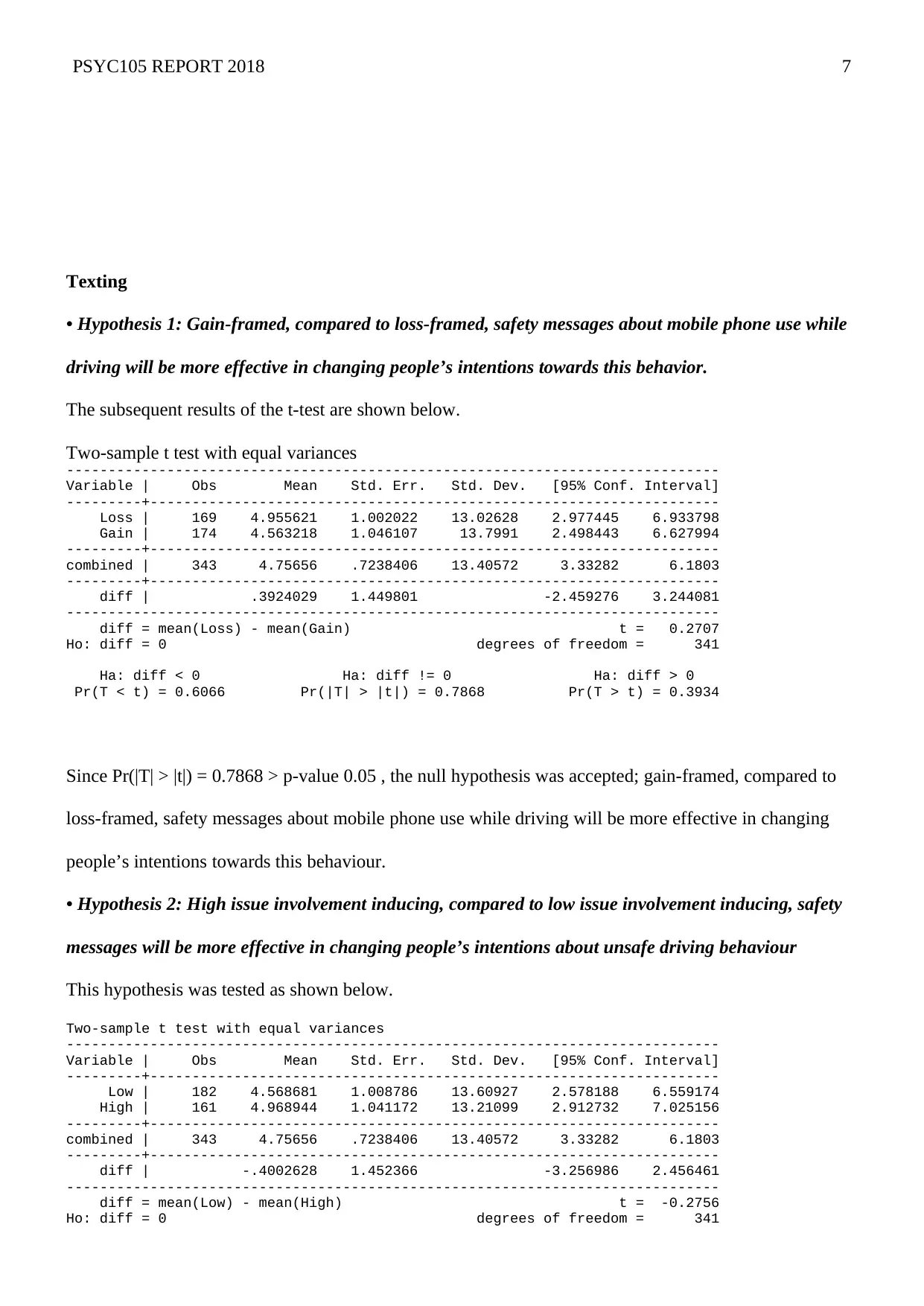

Texting

• Hypothesis 1: Gain-framed, compared to loss-framed, safety messages about mobile phone use while

driving will be more effective in changing people’s intentions towards this behavior.

The subsequent results of the t-test are shown below.

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Loss | 169 4.955621 1.002022 13.02628 2.977445 6.933798

Gain | 174 4.563218 1.046107 13.7991 2.498443 6.627994

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 343 4.75656 .7238406 13.40572 3.33282 6.1803

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | .3924029 1.449801 -2.459276 3.244081

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Loss) - mean(Gain) t = 0.2707

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 341

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.6066 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.7868 Pr(T > t) = 0.3934

Since Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.7868 > p-value 0.05 , the null hypothesis was accepted; gain-framed, compared to

loss-framed, safety messages about mobile phone use while driving will be more effective in changing

people’s intentions towards this behaviour.

• Hypothesis 2: High issue involvement inducing, compared to low issue involvement inducing, safety

messages will be more effective in changing people’s intentions about unsafe driving behaviour

This hypothesis was tested as shown below.

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Low | 182 4.568681 1.008786 13.60927 2.578188 6.559174

High | 161 4.968944 1.041172 13.21099 2.912732 7.025156

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 343 4.75656 .7238406 13.40572 3.33282 6.1803

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | -.4002628 1.452366 -3.256986 2.456461

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Low) - mean(High) t = -0.2756

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 341

Texting

• Hypothesis 1: Gain-framed, compared to loss-framed, safety messages about mobile phone use while

driving will be more effective in changing people’s intentions towards this behavior.

The subsequent results of the t-test are shown below.

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Loss | 169 4.955621 1.002022 13.02628 2.977445 6.933798

Gain | 174 4.563218 1.046107 13.7991 2.498443 6.627994

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 343 4.75656 .7238406 13.40572 3.33282 6.1803

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | .3924029 1.449801 -2.459276 3.244081

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Loss) - mean(Gain) t = 0.2707

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 341

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.6066 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.7868 Pr(T > t) = 0.3934

Since Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.7868 > p-value 0.05 , the null hypothesis was accepted; gain-framed, compared to

loss-framed, safety messages about mobile phone use while driving will be more effective in changing

people’s intentions towards this behaviour.

• Hypothesis 2: High issue involvement inducing, compared to low issue involvement inducing, safety

messages will be more effective in changing people’s intentions about unsafe driving behaviour

This hypothesis was tested as shown below.

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Low | 182 4.568681 1.008786 13.60927 2.578188 6.559174

High | 161 4.968944 1.041172 13.21099 2.912732 7.025156

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 343 4.75656 .7238406 13.40572 3.33282 6.1803

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | -.4002628 1.452366 -3.256986 2.456461

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Low) - mean(High) t = -0.2756

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 341

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

PSYC105 REPORT 2018 8

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.3915 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.7830 Pr(T > t) = 0.6085

From the results, Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.7830 > p-value 0.05, hence the null objective was accepted, that is, high

issue involvement inducing, compared to low issue involvement inducing, safety messages will be more

effective in changing people’s intentions about unsafe driving behaviour.

• Hypothesis 3: Gain-framed safety messages about mobile phone use will be most effective when

paired with a high issue involvement inducing message

The hypothesis was subsequently tested as shown below.

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Loss | 81 4.895062 1.259952 11.33956 2.387678 7.402445

Gain | 80 5.04375 1.670533 14.9417 1.718638 8.368862

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 161 4.968944 1.041172 13.21099 2.912732 7.025156

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | -.1486883 2.088889 -4.274236 3.976859

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Loss) - mean(Gain) t = -0.0712

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 159

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.4717 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.9433 Pr(T > t) = 0.5283

Since the Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.9523 > p-value 0.05, the null hypothesis accepted, that is, gain-framed safety

messages about mobile phone use will be most effective when paired with a high issue involvement

inducing message.

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.3915 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.7830 Pr(T > t) = 0.6085

From the results, Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.7830 > p-value 0.05, hence the null objective was accepted, that is, high

issue involvement inducing, compared to low issue involvement inducing, safety messages will be more

effective in changing people’s intentions about unsafe driving behaviour.

• Hypothesis 3: Gain-framed safety messages about mobile phone use will be most effective when

paired with a high issue involvement inducing message

The hypothesis was subsequently tested as shown below.

Two-sample t test with equal variances

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Variable | Obs Mean Std. Err. Std. Dev. [95% Conf. Interval]

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

Loss | 81 4.895062 1.259952 11.33956 2.387678 7.402445

Gain | 80 5.04375 1.670533 14.9417 1.718638 8.368862

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

combined | 161 4.968944 1.041172 13.21099 2.912732 7.025156

---------+--------------------------------------------------------------------

diff | -.1486883 2.088889 -4.274236 3.976859

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff = mean(Loss) - mean(Gain) t = -0.0712

Ho: diff = 0 degrees of freedom = 159

Ha: diff < 0 Ha: diff != 0 Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.4717 Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.9433 Pr(T > t) = 0.5283

Since the Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.9523 > p-value 0.05, the null hypothesis accepted, that is, gain-framed safety

messages about mobile phone use will be most effective when paired with a high issue involvement

inducing message.

PSYC105 REPORT 2018 9

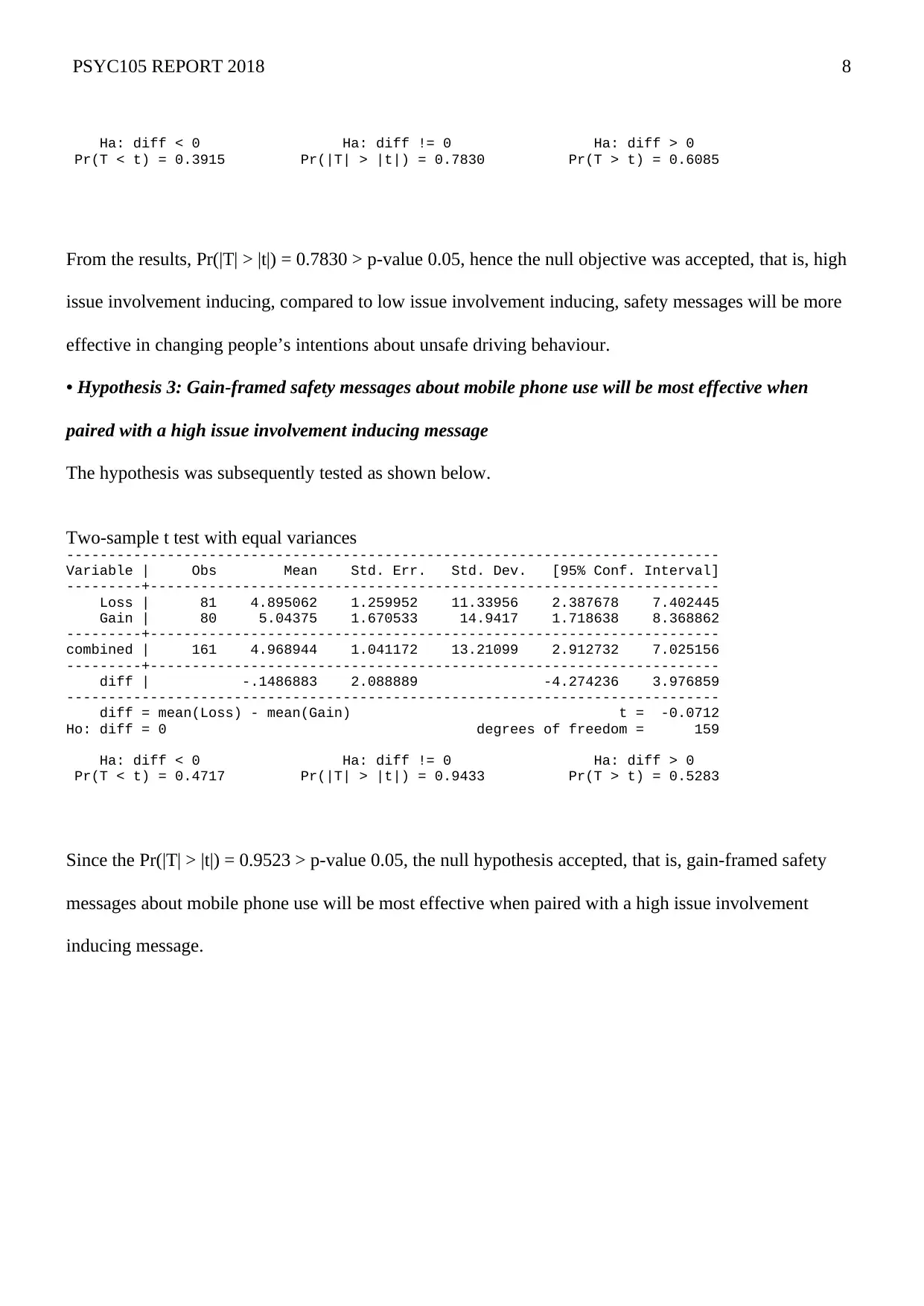

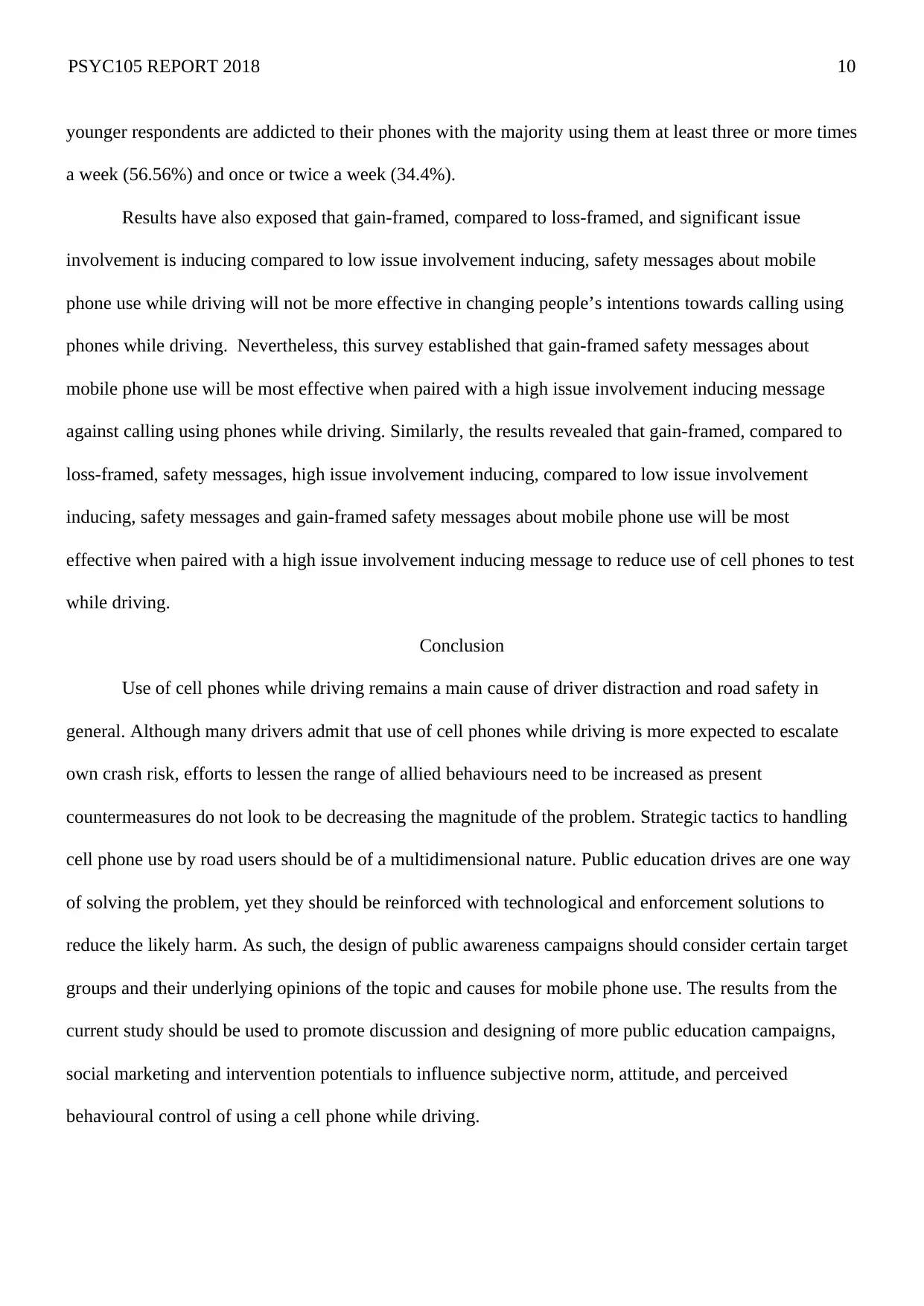

The above findings are summarized in form of a box plot shown below.

Low Involvement High Involvement

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Gain-framed Loss-framed

Change in Intention to Text

Graph representing the mean change in intention to text while driving between the four groups.

Discussion

Cases of using a phone while driving are not new irrespective of the legislation frowning at such

act. The cell phone distracts drivers in two ways: it results in cognitive and physical distraction. Cognitive

distraction happens when a driver has to channel part of her of his thoughtfulness from driving to the cell

phone conversation (Chaurand, Bossart & Delhomme, 2015). The capability to divide individual attention

between two simultaneous activities is limited. On the other hand, physical distraction arises when drivers

have to instantaneously operate their cell phone (that is, dial, reach, hold) and drive their vehicle

(Hoekstra, & Wegman, 2011).

The present study examined the use of cell phones while driving to receive/make calls, send/

create text messages and create/ access/ social media in Western Australia. The study gained a sample of

892 respondents, but only responses from 343 respondents were considered appropriate for this study,

74.34% of whom were males, and 25.07% were males.

Overall, the finding revealed that that cell phone use, while driving was highly prevalent as 27%

of younger respondents, had used their mobile phone at least once or twice a week while driving. Also,

The above findings are summarized in form of a box plot shown below.

Low Involvement High Involvement

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Gain-framed Loss-framed

Change in Intention to Text

Graph representing the mean change in intention to text while driving between the four groups.

Discussion

Cases of using a phone while driving are not new irrespective of the legislation frowning at such

act. The cell phone distracts drivers in two ways: it results in cognitive and physical distraction. Cognitive

distraction happens when a driver has to channel part of her of his thoughtfulness from driving to the cell

phone conversation (Chaurand, Bossart & Delhomme, 2015). The capability to divide individual attention

between two simultaneous activities is limited. On the other hand, physical distraction arises when drivers

have to instantaneously operate their cell phone (that is, dial, reach, hold) and drive their vehicle

(Hoekstra, & Wegman, 2011).

The present study examined the use of cell phones while driving to receive/make calls, send/

create text messages and create/ access/ social media in Western Australia. The study gained a sample of

892 respondents, but only responses from 343 respondents were considered appropriate for this study,

74.34% of whom were males, and 25.07% were males.

Overall, the finding revealed that that cell phone use, while driving was highly prevalent as 27%

of younger respondents, had used their mobile phone at least once or twice a week while driving. Also,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

PSYC105 REPORT 2018 10

younger respondents are addicted to their phones with the majority using them at least three or more times

a week (56.56%) and once or twice a week (34.4%).

Results have also exposed that gain-framed, compared to loss-framed, and significant issue

involvement is inducing compared to low issue involvement inducing, safety messages about mobile

phone use while driving will not be more effective in changing people’s intentions towards calling using

phones while driving. Nevertheless, this survey established that gain-framed safety messages about

mobile phone use will be most effective when paired with a high issue involvement inducing message

against calling using phones while driving. Similarly, the results revealed that gain-framed, compared to

loss-framed, safety messages, high issue involvement inducing, compared to low issue involvement

inducing, safety messages and gain-framed safety messages about mobile phone use will be most

effective when paired with a high issue involvement inducing message to reduce use of cell phones to test

while driving.

Conclusion

Use of cell phones while driving remains a main cause of driver distraction and road safety in

general. Although many drivers admit that use of cell phones while driving is more expected to escalate

own crash risk, efforts to lessen the range of allied behaviours need to be increased as present

countermeasures do not look to be decreasing the magnitude of the problem. Strategic tactics to handling

cell phone use by road users should be of a multidimensional nature. Public education drives are one way

of solving the problem, yet they should be reinforced with technological and enforcement solutions to

reduce the likely harm. As such, the design of public awareness campaigns should consider certain target

groups and their underlying opinions of the topic and causes for mobile phone use. The results from the

current study should be used to promote discussion and designing of more public education campaigns,

social marketing and intervention potentials to influence subjective norm, attitude, and perceived

behavioural control of using a cell phone while driving.

younger respondents are addicted to their phones with the majority using them at least three or more times

a week (56.56%) and once or twice a week (34.4%).

Results have also exposed that gain-framed, compared to loss-framed, and significant issue

involvement is inducing compared to low issue involvement inducing, safety messages about mobile

phone use while driving will not be more effective in changing people’s intentions towards calling using

phones while driving. Nevertheless, this survey established that gain-framed safety messages about

mobile phone use will be most effective when paired with a high issue involvement inducing message

against calling using phones while driving. Similarly, the results revealed that gain-framed, compared to

loss-framed, safety messages, high issue involvement inducing, compared to low issue involvement

inducing, safety messages and gain-framed safety messages about mobile phone use will be most

effective when paired with a high issue involvement inducing message to reduce use of cell phones to test

while driving.

Conclusion

Use of cell phones while driving remains a main cause of driver distraction and road safety in

general. Although many drivers admit that use of cell phones while driving is more expected to escalate

own crash risk, efforts to lessen the range of allied behaviours need to be increased as present

countermeasures do not look to be decreasing the magnitude of the problem. Strategic tactics to handling

cell phone use by road users should be of a multidimensional nature. Public education drives are one way

of solving the problem, yet they should be reinforced with technological and enforcement solutions to

reduce the likely harm. As such, the design of public awareness campaigns should consider certain target

groups and their underlying opinions of the topic and causes for mobile phone use. The results from the

current study should be used to promote discussion and designing of more public education campaigns,

social marketing and intervention potentials to influence subjective norm, attitude, and perceived

behavioural control of using a cell phone while driving.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

PSYC105 REPORT 2018 11

References

Cazzulino, F., Burke, R. V., Muller, V., Arbogast. H. & Upperman, J. S. (2014). Cell Phones and Young

Drivers: A systematic review regarding the association between psychological factors and prevention.

Traffic Injury Prevention, 15, 234-242.

Chaurand, N., Bossart, F. & Delhomme, P. (2015). A naturalistic study of the impact of message framing

on highway speeding. Transport Research Part F, 35, 37-44.

Hoekstra, T. & Wegman, F. (2011). Improving the effectiveness of road safety campaigns: Current and

new practices. IATSS Research, 34, 80-86.

Miller, M. G. & Miller. K. U. (2000). Promoting Safe Driving Behaviours: The influence of message

framing and issue involvement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30 (4), 853-866.

References

Cazzulino, F., Burke, R. V., Muller, V., Arbogast. H. & Upperman, J. S. (2014). Cell Phones and Young

Drivers: A systematic review regarding the association between psychological factors and prevention.

Traffic Injury Prevention, 15, 234-242.

Chaurand, N., Bossart, F. & Delhomme, P. (2015). A naturalistic study of the impact of message framing

on highway speeding. Transport Research Part F, 35, 37-44.

Hoekstra, T. & Wegman, F. (2011). Improving the effectiveness of road safety campaigns: Current and

new practices. IATSS Research, 34, 80-86.

Miller, M. G. & Miller. K. U. (2000). Promoting Safe Driving Behaviours: The influence of message

framing and issue involvement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30 (4), 853-866.

1 out of 11

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.