Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes

Added on 2023-06-09

7 Pages9189 Words406 Views

Lincoln et al., J Palliative Care Med 2013, S3

DOI: 10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Research Article Open Access

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access journal

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management

in Primary Care: A Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’

Experiences and Attitudes

L Elizabeth Lincoln1,2 *, Linda Pellico3 , Robert Kerns 2,4,5 and Daren Anderson6

1 Department of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, USA

2 VA Connecticut Health Care System, USA

3 Yale University School of Nursing, USA

4 Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Yale University School of Medicine, USA

5 Department of Psychology, Yale University, USA

6 Community Health Center Inc., USA

Abstract

Objectives: Most patients with chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) are cared for, by primary care providers (PCPs).

While some of the barriers faced by PCPs have been described, there is little information about PCPs’ experience with

factors that facilitate CNCP care.

Design: The study design was descriptive and qualitative. Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Krippendorff’s thematic clustering technique was used to identify the repetitive themes regarding PCPs’ experiences

related to CNCP management.

Subjects: Respondents were PCPs (n=45) in the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in two academically affiliated

institutions and six community based sites.

Results: Eleven themes were identified across systems, personal/professional, and interpersonal domains.

Barriers included inadequate training, organizational impediments, clinical quandaries and the frustrations that

accompany them, issues related to share care among PCPs and specialists, antagonistic aspects of provider-patient

interactions, skepticism, and time factors. Facilitators included the intellectual satisfaction of solving difficult diagnostic

and management problems, the ability to develop keener communication skills, the rewards of healing and building

therapeutic alliances with patients, universal protocols, and the availability of complementary and alternative medicine

resources and multidisciplinary care.

Conclusion: PCPs experience substantial difficulties in caring for patients with pain while acknowledging certain

positive aspects. There is a need for strategies that mitigate the barriers to pain management while bolstering the

positive aspects to improve care and provider satisfaction.

*Corresponding author: L Elizabeth Lincoln, Instructor, Department of

Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital 55 Fruit

St, Yawkey 4B, Suite 4700 Boston, MA 02114, USA, Tel: 203-752-6168; E-mail:

llincoln2@partners.org

Received February 25, 2013; Accepted March 08, 2013; Published March 11,

2013

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators

to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A Qualitative Analysis

of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3:

001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Copyright: © 2013 Lincoln LE, et al. This is an open-access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original author and source are credited.

Keywords: Primary care; Chronic pain; Pain management; Primary

care providers; Ambulatory care

Introduction

Pain and effective pain care are among the most critical health

issues facing Americans. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine reported

that about one-third of all Americans experience persistent pain at an

annual cost of as much as $635 billion in medical treatment and lost

productivity. The report noted that military veterans are an especially

vulnerable group, with data documenting a particularly high prevalence

of pain and extraordinary rates of complexity associated with multiple

medical and mental health comorbidities [1].

Pain is the most common symptom reported by patients receiving

care in primary care, accounting for up to 40% of all visits to primary

care providers (PCPs) [2]. More than half of all patients who have

Chronic Non-Cancer Pain (CNCP) receive their care primarily from

PCPs [3]. Estimates suggest that as many as 50% of male veterans and

up to 75% of female veterans seen in Veteran’s Health Administration

(VHA) primary care settings report the presence of pain [4-6]. More

recent data suggest that the prevalence of CNCP, particularly painful

musculoskeletal disorders including chronic low back pain, is increasing

annually [7]. Cost effective strategies that improve the management of

CNCP in the primary care setting are needed to address the challenges

posed by this public health crisis.

The VHA has implemented a Stepped Care Model for Pain

Management (SCM-PM) as a national pain care strategy to meet the

needs of veterans [8]. The SCM-PM provides for effective assessment

and treatment of pain within primary care whenever possible, with

the capacity to escalate treatment options to include specialized care

and interdisciplinary approaches, if needed. Critical to the success of

the SCM-PM is the ability of PCPs and multidisciplinary primary care

teams to effectively access and manage most common pain conditions.

The SCM-PM is similar to that advocated by the American Academy

of Pain Medicine [9], and it was cited by the Institute of Medicine as a

potentially important model of care for persons with CNCP [1].

Unfortunately, the literature suggests that PCPs do not feel

adequately prepared to take on the role of frontline providers for

patients with CNCP. Although several studies have described PCPs’

attitudes and barriers to prescribing opioids for CNCP [10-14],

Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

P

a

I

I

i

a

t

i

v

e

C

a

r

e

&

M

e

d

i

c

i

n

e

ISSN: 2165-7386

DOI: 10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Research Article Open Access

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access journal

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management

in Primary Care: A Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’

Experiences and Attitudes

L Elizabeth Lincoln1,2 *, Linda Pellico3 , Robert Kerns 2,4,5 and Daren Anderson6

1 Department of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, USA

2 VA Connecticut Health Care System, USA

3 Yale University School of Nursing, USA

4 Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Yale University School of Medicine, USA

5 Department of Psychology, Yale University, USA

6 Community Health Center Inc., USA

Abstract

Objectives: Most patients with chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) are cared for, by primary care providers (PCPs).

While some of the barriers faced by PCPs have been described, there is little information about PCPs’ experience with

factors that facilitate CNCP care.

Design: The study design was descriptive and qualitative. Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Krippendorff’s thematic clustering technique was used to identify the repetitive themes regarding PCPs’ experiences

related to CNCP management.

Subjects: Respondents were PCPs (n=45) in the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in two academically affiliated

institutions and six community based sites.

Results: Eleven themes were identified across systems, personal/professional, and interpersonal domains.

Barriers included inadequate training, organizational impediments, clinical quandaries and the frustrations that

accompany them, issues related to share care among PCPs and specialists, antagonistic aspects of provider-patient

interactions, skepticism, and time factors. Facilitators included the intellectual satisfaction of solving difficult diagnostic

and management problems, the ability to develop keener communication skills, the rewards of healing and building

therapeutic alliances with patients, universal protocols, and the availability of complementary and alternative medicine

resources and multidisciplinary care.

Conclusion: PCPs experience substantial difficulties in caring for patients with pain while acknowledging certain

positive aspects. There is a need for strategies that mitigate the barriers to pain management while bolstering the

positive aspects to improve care and provider satisfaction.

*Corresponding author: L Elizabeth Lincoln, Instructor, Department of

Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital 55 Fruit

St, Yawkey 4B, Suite 4700 Boston, MA 02114, USA, Tel: 203-752-6168; E-mail:

llincoln2@partners.org

Received February 25, 2013; Accepted March 08, 2013; Published March 11,

2013

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators

to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A Qualitative Analysis

of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3:

001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Copyright: © 2013 Lincoln LE, et al. This is an open-access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original author and source are credited.

Keywords: Primary care; Chronic pain; Pain management; Primary

care providers; Ambulatory care

Introduction

Pain and effective pain care are among the most critical health

issues facing Americans. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine reported

that about one-third of all Americans experience persistent pain at an

annual cost of as much as $635 billion in medical treatment and lost

productivity. The report noted that military veterans are an especially

vulnerable group, with data documenting a particularly high prevalence

of pain and extraordinary rates of complexity associated with multiple

medical and mental health comorbidities [1].

Pain is the most common symptom reported by patients receiving

care in primary care, accounting for up to 40% of all visits to primary

care providers (PCPs) [2]. More than half of all patients who have

Chronic Non-Cancer Pain (CNCP) receive their care primarily from

PCPs [3]. Estimates suggest that as many as 50% of male veterans and

up to 75% of female veterans seen in Veteran’s Health Administration

(VHA) primary care settings report the presence of pain [4-6]. More

recent data suggest that the prevalence of CNCP, particularly painful

musculoskeletal disorders including chronic low back pain, is increasing

annually [7]. Cost effective strategies that improve the management of

CNCP in the primary care setting are needed to address the challenges

posed by this public health crisis.

The VHA has implemented a Stepped Care Model for Pain

Management (SCM-PM) as a national pain care strategy to meet the

needs of veterans [8]. The SCM-PM provides for effective assessment

and treatment of pain within primary care whenever possible, with

the capacity to escalate treatment options to include specialized care

and interdisciplinary approaches, if needed. Critical to the success of

the SCM-PM is the ability of PCPs and multidisciplinary primary care

teams to effectively access and manage most common pain conditions.

The SCM-PM is similar to that advocated by the American Academy

of Pain Medicine [9], and it was cited by the Institute of Medicine as a

potentially important model of care for persons with CNCP [1].

Unfortunately, the literature suggests that PCPs do not feel

adequately prepared to take on the role of frontline providers for

patients with CNCP. Although several studies have described PCPs’

attitudes and barriers to prescribing opioids for CNCP [10-14],

Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

P

a

I

I

i

a

t

i

v

e

C

a

r

e

&

M

e

d

i

c

i

n

e

ISSN: 2165-7386

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 2 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access journal

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

provided with a study information sheet and a paper copy of the three

survey questions. Open-ended questions were selected for this survey

because this tactic offers a less biased approach rather than forced

participant responses and it facilitates spontaneity from respondents

[21]. Participants were recruited at practice meetings, via mailings, and

e-mail. Non-respondents were contacted again through e-mail by one

of the study staff. Study questions were:

1. Describe some barriers that you feel limit your ability to

manage chronic pain.

2. Can you describe some of the positive aspects related to caring

for patients with chronic pain?

3. What are some of the negative aspects about caring for patients

with chronic pain?

The PCPs’ written comments were typed verbatim into an excel

spread sheet and verified as accurate by comparing them to the

original survey data. Respondents’ comments totaled nearly 3000

words; individual comments ranged from one word (“time”) to 55

words (average, 11 words). Rather than code responses by each survey

question, all data were merged in order to comprehend meaning in its

entirety without losing connections between the three survey probes.

Three of the four authors read the aggregated comments in entirety

and inductively coded the comments. An inductive approach was

used to analyze the data since there is fragmented knowledge related

to the phenomenon of PCPs’ experience with CNCP using qualitative

methodology [22]. In inductive coding, the text progresses from

specific to general, so that individual instances are discerned and then

related into a larger whole that describes the phenomenon of interest.

Content analysis using Krippendorff’s method [23] was used to identify

repetitive themes. Coding consisted of the authors separately selecting

exact words, passages, or sentences, noting unique comments as well

as recurrent passages related to the research questions. Data were

grouped according to Krippendorff’s analytical technique of clustering

to identify phrases and sentences that shared some characteristics. As

an example, statements such as “suspicion,” “lack of trust in the experts’

expertise,” and “many comfortable patients state their pain score is 10”

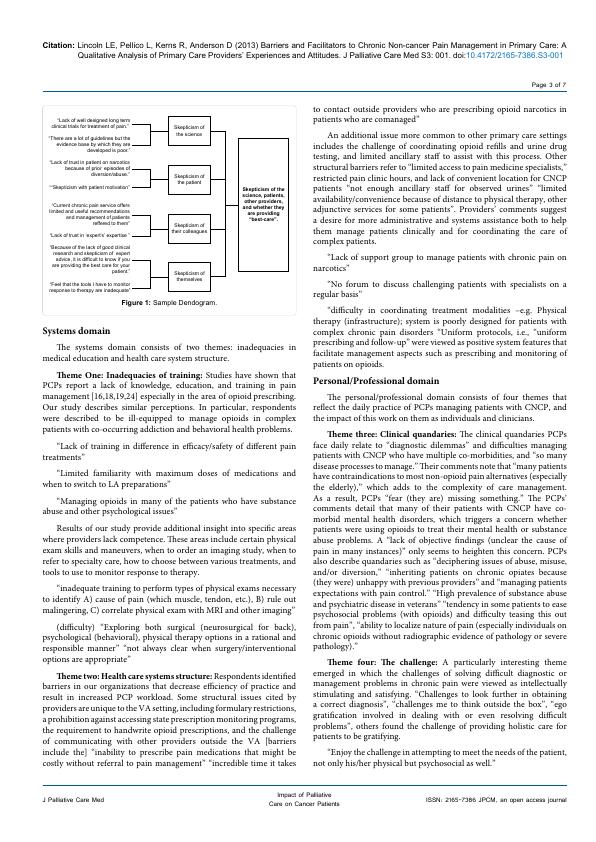

were categorized as skepticism. Dendrograms, or tree-like diagrams,

were then created to illustrate how data collapsed into clusters. An

example of a dendogram is presented in figure 1.

Authors consisted of a multidisciplinary team including a qualitative

nurse researcher, two primary care providers, and a pain psychologist.

The authors met frequently to discuss selection of passages, text

characteristics, and the transcripts were discussed line by line. Coding

among the researchers was reconciled to represent consensus about

the meaning of participant comments, and the construction of themes

was established by group consensus. An audit trail was created to

record personal reflections and to provide plausible interpretation and

evidence of consistency with the original data set. The audit trail was

shared with all authors. In addition, numerous participant quotes were

included in the results to enhance the credibility of our findings.

Results

Eleven themes were identified. The themes are artificially organized

into three domains as a taxonomy in which the reader can consider

the inter-relationships of the themes. They are: System, Personal/

Professional, and Interpersonal domains. Two of the eleven themes

interrelate across the three domains and therefore are described

separately.

few studies provide a broad overview of CNCP management from

a provider’s perspective. Previous surveys have shown that PCPs

have concerns about the prescribing of opioids and are fearful of

contributing to addiction. In addition, PCPs note the deficiency in

primary care education and training in pain management, and question

their capacity to provide optimal pain care [15-19]. Limitations of this

research include the fact that some of these studies targeted subsets of

the broader population of primary care patients with CNCP such as

patients having high rates of opioid utilization or addiction, or included

providers other than PCPs. More information is particularly needed

about the experiences and attitudes of PCPs serving the population

of veterans. There are even fewer studies using qualitative analysis

[17,19,20]. Qualitative research offers a method of inquiry that values

the identification of the human experience related to a phenomenon

of interest and may provide a more complete understanding of PCPs’

attitudes and experiences about pain management. Interestingly, to our

knowledge, no study has specifically inquired about the positive aspects

of pain management. While we know about some of the barriers to pain

care, there is relatively little information about factors that providers

feel facilitate the care of patients with chronic pain other than opioid

agreements and a strong therapeutic doctor-patient alliance [17,20].

Our objective in conducting this study was to further describe the

context of CNCP management in primary care by exploring PCPs’

experiences and viewpoints of barriers and facilitators using qualitative

analysis. We expected that the findings would highlight important

opportunities for improving the quality of chronic pain management

in primary care not previously identified. This study was part of a larger

research project to improve the care of veterans with chronic pain at

the VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) and its findings

will be used to promote knowledge uptake and inform system-wide

improvements in pain management across the VHA.

Methods

Setting

The primary care section of the VACHS provides medical care to

46,000 veterans. Primary care is provided by PCPs in two large academic

medical centers and six community based practices. Comprehensive

specialty care is available to all VACHS patients. Patients have access to

pain specialists who perform consultations and procedures, as well as

to an interdisciplinary pain center.

Sample

All PCPs (N=60) were invited to participate in the study by

completing a three item open response survey and a fifty item

knowledge questionnaire. Only results of the open response survey

are reported here. Forty-five PCPs participated, for a return rate of

75%. Respondents were 60% female and 40% male, with 40 Attending

Physicians, four Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs), and

one Physician Assistant (PA). Academic faculty numbered 26. Average

time in practice since graduation from training was 17 years. On

average, approximately five percent of each provider’s panel of patients

was being treated with prescription opioid medication.

Design

Survey questions were formed based upon current research

findings, overall aims of the study, and researchers’ experience treating

patients with chronic pain. This study was reviewed and approved by

the VACHS Human Studies Subcommittee, and the Yale University

School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. A waiver of written

informed consent was approved. All PCPs in the VACHS were

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 2 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access journal

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

provided with a study information sheet and a paper copy of the three

survey questions. Open-ended questions were selected for this survey

because this tactic offers a less biased approach rather than forced

participant responses and it facilitates spontaneity from respondents

[21]. Participants were recruited at practice meetings, via mailings, and

e-mail. Non-respondents were contacted again through e-mail by one

of the study staff. Study questions were:

1. Describe some barriers that you feel limit your ability to

manage chronic pain.

2. Can you describe some of the positive aspects related to caring

for patients with chronic pain?

3. What are some of the negative aspects about caring for patients

with chronic pain?

The PCPs’ written comments were typed verbatim into an excel

spread sheet and verified as accurate by comparing them to the

original survey data. Respondents’ comments totaled nearly 3000

words; individual comments ranged from one word (“time”) to 55

words (average, 11 words). Rather than code responses by each survey

question, all data were merged in order to comprehend meaning in its

entirety without losing connections between the three survey probes.

Three of the four authors read the aggregated comments in entirety

and inductively coded the comments. An inductive approach was

used to analyze the data since there is fragmented knowledge related

to the phenomenon of PCPs’ experience with CNCP using qualitative

methodology [22]. In inductive coding, the text progresses from

specific to general, so that individual instances are discerned and then

related into a larger whole that describes the phenomenon of interest.

Content analysis using Krippendorff’s method [23] was used to identify

repetitive themes. Coding consisted of the authors separately selecting

exact words, passages, or sentences, noting unique comments as well

as recurrent passages related to the research questions. Data were

grouped according to Krippendorff’s analytical technique of clustering

to identify phrases and sentences that shared some characteristics. As

an example, statements such as “suspicion,” “lack of trust in the experts’

expertise,” and “many comfortable patients state their pain score is 10”

were categorized as skepticism. Dendrograms, or tree-like diagrams,

were then created to illustrate how data collapsed into clusters. An

example of a dendogram is presented in figure 1.

Authors consisted of a multidisciplinary team including a qualitative

nurse researcher, two primary care providers, and a pain psychologist.

The authors met frequently to discuss selection of passages, text

characteristics, and the transcripts were discussed line by line. Coding

among the researchers was reconciled to represent consensus about

the meaning of participant comments, and the construction of themes

was established by group consensus. An audit trail was created to

record personal reflections and to provide plausible interpretation and

evidence of consistency with the original data set. The audit trail was

shared with all authors. In addition, numerous participant quotes were

included in the results to enhance the credibility of our findings.

Results

Eleven themes were identified. The themes are artificially organized

into three domains as a taxonomy in which the reader can consider

the inter-relationships of the themes. They are: System, Personal/

Professional, and Interpersonal domains. Two of the eleven themes

interrelate across the three domains and therefore are described

separately.

few studies provide a broad overview of CNCP management from

a provider’s perspective. Previous surveys have shown that PCPs

have concerns about the prescribing of opioids and are fearful of

contributing to addiction. In addition, PCPs note the deficiency in

primary care education and training in pain management, and question

their capacity to provide optimal pain care [15-19]. Limitations of this

research include the fact that some of these studies targeted subsets of

the broader population of primary care patients with CNCP such as

patients having high rates of opioid utilization or addiction, or included

providers other than PCPs. More information is particularly needed

about the experiences and attitudes of PCPs serving the population

of veterans. There are even fewer studies using qualitative analysis

[17,19,20]. Qualitative research offers a method of inquiry that values

the identification of the human experience related to a phenomenon

of interest and may provide a more complete understanding of PCPs’

attitudes and experiences about pain management. Interestingly, to our

knowledge, no study has specifically inquired about the positive aspects

of pain management. While we know about some of the barriers to pain

care, there is relatively little information about factors that providers

feel facilitate the care of patients with chronic pain other than opioid

agreements and a strong therapeutic doctor-patient alliance [17,20].

Our objective in conducting this study was to further describe the

context of CNCP management in primary care by exploring PCPs’

experiences and viewpoints of barriers and facilitators using qualitative

analysis. We expected that the findings would highlight important

opportunities for improving the quality of chronic pain management

in primary care not previously identified. This study was part of a larger

research project to improve the care of veterans with chronic pain at

the VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) and its findings

will be used to promote knowledge uptake and inform system-wide

improvements in pain management across the VHA.

Methods

Setting

The primary care section of the VACHS provides medical care to

46,000 veterans. Primary care is provided by PCPs in two large academic

medical centers and six community based practices. Comprehensive

specialty care is available to all VACHS patients. Patients have access to

pain specialists who perform consultations and procedures, as well as

to an interdisciplinary pain center.

Sample

All PCPs (N=60) were invited to participate in the study by

completing a three item open response survey and a fifty item

knowledge questionnaire. Only results of the open response survey

are reported here. Forty-five PCPs participated, for a return rate of

75%. Respondents were 60% female and 40% male, with 40 Attending

Physicians, four Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs), and

one Physician Assistant (PA). Academic faculty numbered 26. Average

time in practice since graduation from training was 17 years. On

average, approximately five percent of each provider’s panel of patients

was being treated with prescription opioid medication.

Design

Survey questions were formed based upon current research

findings, overall aims of the study, and researchers’ experience treating

patients with chronic pain. This study was reviewed and approved by

the VACHS Human Studies Subcommittee, and the Yale University

School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. A waiver of written

informed consent was approved. All PCPs in the VACHS were

Citation: Lincoln LE, Pellico L, Kerns R, Anderson D (2013) Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in Primary Care: A

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 3 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access journal

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

Systems domain

The systems domain consists of two themes: inadequacies in

medical education and health care system structure.

Theme One: Inadequacies of training: Studies have shown that

PCPs report a lack of knowledge, education, and training in pain

management [16,18,19,24] especially in the area of opioid prescribing.

Our study describes similar perceptions. In particular, respondents

were described to be ill-equipped to manage opioids in complex

patients with co-occurring addiction and behavioral health problems.

“Lack of training in difference in efficacy/safety of different pain

treatments”

“Limited familiarity with maximum doses of medications and

when to switch to LA preparations”

“Managing opioids in many of the patients who have substance

abuse and other psychological issues”

Results of our study provide additional insight into specific areas

where providers lack competence. These areas include certain physical

exam skills and maneuvers, when to order an imaging study, when to

refer to specialty care, how to choose between various treatments, and

tools to use to monitor response to therapy.

“inadequate training to perform types of physical exams necessary

to identify A) cause of pain (which muscle, tendon, etc.), B) rule out

malingering, C) correlate physical exam with MRI and other imaging”

(difficulty) “Exploring both surgical (neurosurgical for back),

psychological (behavioral), physical therapy options in a rational and

responsible manner” “not always clear when surgery/interventional

options are appropriate”

Theme two: Health care systems structure: Respondents identified

barriers in our organizations that decrease efficiency of practice and

result in increased PCP workload. Some structural issues cited by

providers are unique to the VA setting, including formulary restrictions,

a prohibition against accessing state prescription monitoring programs,

the requirement to handwrite opioid prescriptions, and the challenge

of communicating with other providers outside the VA [barriers

include the] “inability to prescribe pain medications that might be

costly without referral to pain management” “incredible time it takes

to contact outside providers who are prescribing opioid narcotics in

patients who are comanaged”

An additional issue more common to other primary care settings

includes the challenge of coordinating opioid refills and urine drug

testing, and limited ancillary staff to assist with this process. Other

structural barriers refer to “limited access to pain medicine specialists,”

restricted pain clinic hours, and lack of convenient location for CNCP

patients “not enough ancillary staff for observed urines” “limited

availability/convenience because of distance to physical therapy, other

adjunctive services for some patients”. Providers’ comments suggest

a desire for more administrative and systems assistance both to help

them manage patients clinically and for coordinating the care of

complex patients.

“Lack of support group to manage patients with chronic pain on

narcotics”

“No forum to discuss challenging patients with specialists on a

regular basis”

“difficulty in coordinating treatment modalities –e.g. Physical

therapy (infrastructure); system is poorly designed for patients with

complex chronic pain disorders “Uniform protocols, i.e., “uniform

prescribing and follow-up” were viewed as positive system features that

facilitate management aspects such as prescribing and monitoring of

patients on opioids.

Personal/Professional domain

The personal/professional domain consists of four themes that

reflect the daily practice of PCPs managing patients with CNCP, and

the impact of this work on them as individuals and clinicians.

Theme three: Clinical quandaries: The clinical quandaries PCPs

face daily relate to “diagnostic dilemmas” and difficulties managing

patients with CNCP who have multiple co-morbidities, and “so many

disease processes to manage.” Their comments note that “many patients

have contraindications to most non-opioid pain alternatives (especially

the elderly),” which adds to the complexity of care management.

As a result, PCPs “fear (they are) missing something.” The PCPs’

comments detail that many of their patients with CNCP have co-

morbid mental health disorders, which triggers a concern whether

patients were using opioids to treat their mental health or substance

abuse problems. A “lack of objective findings (unclear the cause of

pain in many instances)” only seems to heighten this concern. PCPs

also describe quandaries such as “deciphering issues of abuse, misuse,

and/or diversion,” “inheriting patients on chronic opiates because

(they were) unhappy with previous providers” and “managing patients

expectations with pain control.” “High prevalence of substance abuse

and psychiatric disease in veterans” “tendency in some patients to ease

psychosocial problems (with opioids) and difficulty teasing this out

from pain”, “ability to localize nature of pain (especially individuals on

chronic opioids without radiographic evidence of pathology or severe

pathology).”

Theme four: The challenge: A particularly interesting theme

emerged in which the challenges of solving difficult diagnostic or

management problems in chronic pain were viewed as intellectually

stimulating and satisfying. “Challenges to look further in obtaining

a correct diagnosis”, “challenges me to think outside the box”, “ego

gratification involved in dealing with or even resolving difficult

problems”, others found the challenge of providing holistic care for

patients to be gratifying.

“Enjoy the challenge in attempting to meet the needs of the patient,

not only his/her physical but psychosocial as well.”

Skepticism of the

science, patients,

other providers,

and whether they

are providing

“best-care”.

Skepticism of

the science

Skepticism of

the patient

Skepticism of

their colleagues

Skepticism of

themselves

“Lack of well designed long term

clinical trials for treatment of pain.”

“There are a lot of guidelines but the

evidence base by which they are

developed is poor.”

“Lack of trust in patient on narcotics

because of prior episodes of

diversion/abuse.”

““Skepticism with patient motivation”

“Current chronic pain service offers

limited and useful recommendations

and management of patients

reffered to them”

“Lack of trust in ‘expert’s’ expertise ”

“Because of the lack of good clinical

research and skepticism of expert

advice, it is difficult to know if you

are providing the best care for your

patient.”

“Feel that the tools I have to monitor

response to therapy are inadequate”

Figure 1: Sample Dendogram.

Qualitative Analysis of Primary Care Providers’ Experiences and Attitudes. J Palliative Care Med S3: 001. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-001

Page 3 of 7

J Palliative Care Med ISSN: 2165-7386 JPCM, an open access journal

Impact of Palliative

Care on Cancer Patients

Systems domain

The systems domain consists of two themes: inadequacies in

medical education and health care system structure.

Theme One: Inadequacies of training: Studies have shown that

PCPs report a lack of knowledge, education, and training in pain

management [16,18,19,24] especially in the area of opioid prescribing.

Our study describes similar perceptions. In particular, respondents

were described to be ill-equipped to manage opioids in complex

patients with co-occurring addiction and behavioral health problems.

“Lack of training in difference in efficacy/safety of different pain

treatments”

“Limited familiarity with maximum doses of medications and

when to switch to LA preparations”

“Managing opioids in many of the patients who have substance

abuse and other psychological issues”

Results of our study provide additional insight into specific areas

where providers lack competence. These areas include certain physical

exam skills and maneuvers, when to order an imaging study, when to

refer to specialty care, how to choose between various treatments, and

tools to use to monitor response to therapy.

“inadequate training to perform types of physical exams necessary

to identify A) cause of pain (which muscle, tendon, etc.), B) rule out

malingering, C) correlate physical exam with MRI and other imaging”

(difficulty) “Exploring both surgical (neurosurgical for back),

psychological (behavioral), physical therapy options in a rational and

responsible manner” “not always clear when surgery/interventional

options are appropriate”

Theme two: Health care systems structure: Respondents identified

barriers in our organizations that decrease efficiency of practice and

result in increased PCP workload. Some structural issues cited by

providers are unique to the VA setting, including formulary restrictions,

a prohibition against accessing state prescription monitoring programs,

the requirement to handwrite opioid prescriptions, and the challenge

of communicating with other providers outside the VA [barriers

include the] “inability to prescribe pain medications that might be

costly without referral to pain management” “incredible time it takes

to contact outside providers who are prescribing opioid narcotics in

patients who are comanaged”

An additional issue more common to other primary care settings

includes the challenge of coordinating opioid refills and urine drug

testing, and limited ancillary staff to assist with this process. Other

structural barriers refer to “limited access to pain medicine specialists,”

restricted pain clinic hours, and lack of convenient location for CNCP

patients “not enough ancillary staff for observed urines” “limited

availability/convenience because of distance to physical therapy, other

adjunctive services for some patients”. Providers’ comments suggest

a desire for more administrative and systems assistance both to help

them manage patients clinically and for coordinating the care of

complex patients.

“Lack of support group to manage patients with chronic pain on

narcotics”

“No forum to discuss challenging patients with specialists on a

regular basis”

“difficulty in coordinating treatment modalities –e.g. Physical

therapy (infrastructure); system is poorly designed for patients with

complex chronic pain disorders “Uniform protocols, i.e., “uniform

prescribing and follow-up” were viewed as positive system features that

facilitate management aspects such as prescribing and monitoring of

patients on opioids.

Personal/Professional domain

The personal/professional domain consists of four themes that

reflect the daily practice of PCPs managing patients with CNCP, and

the impact of this work on them as individuals and clinicians.

Theme three: Clinical quandaries: The clinical quandaries PCPs

face daily relate to “diagnostic dilemmas” and difficulties managing

patients with CNCP who have multiple co-morbidities, and “so many

disease processes to manage.” Their comments note that “many patients

have contraindications to most non-opioid pain alternatives (especially

the elderly),” which adds to the complexity of care management.

As a result, PCPs “fear (they are) missing something.” The PCPs’

comments detail that many of their patients with CNCP have co-

morbid mental health disorders, which triggers a concern whether

patients were using opioids to treat their mental health or substance

abuse problems. A “lack of objective findings (unclear the cause of

pain in many instances)” only seems to heighten this concern. PCPs

also describe quandaries such as “deciphering issues of abuse, misuse,

and/or diversion,” “inheriting patients on chronic opiates because

(they were) unhappy with previous providers” and “managing patients

expectations with pain control.” “High prevalence of substance abuse

and psychiatric disease in veterans” “tendency in some patients to ease

psychosocial problems (with opioids) and difficulty teasing this out

from pain”, “ability to localize nature of pain (especially individuals on

chronic opioids without radiographic evidence of pathology or severe

pathology).”

Theme four: The challenge: A particularly interesting theme

emerged in which the challenges of solving difficult diagnostic or

management problems in chronic pain were viewed as intellectually

stimulating and satisfying. “Challenges to look further in obtaining

a correct diagnosis”, “challenges me to think outside the box”, “ego

gratification involved in dealing with or even resolving difficult

problems”, others found the challenge of providing holistic care for

patients to be gratifying.

“Enjoy the challenge in attempting to meet the needs of the patient,

not only his/her physical but psychosocial as well.”

Skepticism of the

science, patients,

other providers,

and whether they

are providing

“best-care”.

Skepticism of

the science

Skepticism of

the patient

Skepticism of

their colleagues

Skepticism of

themselves

“Lack of well designed long term

clinical trials for treatment of pain.”

“There are a lot of guidelines but the

evidence base by which they are

developed is poor.”

“Lack of trust in patient on narcotics

because of prior episodes of

diversion/abuse.”

““Skepticism with patient motivation”

“Current chronic pain service offers

limited and useful recommendations

and management of patients

reffered to them”

“Lack of trust in ‘expert’s’ expertise ”

“Because of the lack of good clinical

research and skepticism of expert

advice, it is difficult to know if you

are providing the best care for your

patient.”

“Feel that the tools I have to monitor

response to therapy are inadequate”

Figure 1: Sample Dendogram.

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.

Related Documents

Role of Nurses in Cancer Care: A Qualitative Studylg...

|4

|1516

|417

Primary Health Care - NUR115 - Northern Health Hospitallg...

|6

|1453

|60

Informal Care Givers - PDFlg...

|4

|666

|67