Clinical Investigations: Fall Prevention Programs in Nursing Homes

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/04

|11

|8369

|400

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the characteristics and effectiveness of fall prevention programs in nursing homes. The study analyzed 13 randomized controlled trials, evaluating single, multiple, and multifactorial interventions. The primary outcomes were the number of falls, fallers, and recurrent fallers. The meta-analysis revealed that multifactorial interventions significantly reduced falls and recurrent fallers, while single or multiple interventions did not show significant effects. Training and education components showed a harmful effect by increasing the number of falls. The research found that fall prevention interventions significantly reduced the number of recurrent fallers by 21%. The study emphasizes the importance of tailored, multifactorial approaches in preventing falls among nursing home residents, providing valuable insights for improving patient care and reducing fall-related injuries. This analysis contributes to evidence-based practice in geriatric care and the development of more effective fall prevention strategies.

CLINICAL INVESTIGATIONS

Characteristics and Effectiveness of Fall Prevention Programs

Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of

Randomized Controlled Trials

Ellen Vlaeyen, MSN,a Joke Coussement, MSN,a,b Greet Leysens, MSN,a Elisa Van der Elst, MSN,a

Kim Delbaere, MPT, PhD,c Dirk Cambier, MPT, PhD,d Kris Denhaerynck, MSN, PhD,e

Stefan Goemaere, MD,f Arlette Wertelaers, MD,g Fabienne Dobbels, PhD,a

Eddy Dejaeger, MD, PhD,h and Koen Milisen, MSN, PhD,a,h on behalf of the Center of Expertise

for Fall and Fracture Prevention Flanders

OBJECTIVES: To determine characteristics and effective-

ness of prevention programs on fall-related outcomes in a

defined setting.

DESIGN: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

SETTING: A clearly described subgroup of nursing homes

defined as residentialfacilities thatprovide 24-hour-a-day

surveillance,personalcare, and limited clinicalcare for

persons who are typically elderly and infirm.

PARTICIPANTS: Nursing home residents (N = 22,915).

MEASUREMENTS: The primary outcomes were number

of falls, fallers, and recurrent fallers.

RESULTS: Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria.

Six fall prevention programswere single (one interven-

tion componentprovided to the residents),one was mul-

tiple (two or more intervention components not

customized to individualfall risk), and six were multi-

factorial(two or more intervention componentscustom-

ized to each resident’sfall risk). Meta-analysisfound

significantlyfewer recurrentfallers in the intervention

groups(4 studies,relative risk (RR) = 0.79,95% confi-

dence interval(CI) = 0.65–0.97)but no significanteffect

of the interventionon fallers (6 studies, RR = 0.97,

95% CI = 0.84–1.11) or falls (10 studies,RR = 0.93,

95% CI = 0.76–1.13).Multifactorialinterventions signifi-

cantly reduced falls (4 studies, RR = 0.67, 95%

CI = 0.55–0.82)and the numberof recurrentfallers (4

studies,RR = 0.79, CI = 0.65–0.97),whereassingle or

multiple interventionsdid not. Training and education

showed a significantharmful effect in the intervention

groups on the number of falls (2 studies, RR = 1.29,

95% CI = 1.23–1.36).

CONCLUSION: This meta-analysisfailed to reveal a

significant effect of fall prevention interventions on falls or

fallers but,for the firsttime,showed thatfall prevention

interventions significantly reduced the number of recurrent

fallers by 21%. J Am Geriatr Soc 63:211–221, 2015.

Key words: accidentalfalls; prevention;multifactorial

interventions;residentialaged care facilities; meta-

analysis

Nursing home residents have a high risk of falling. The

average fallincidence is estimated to be 1.6 falls per

bed per year,with almosthalf of residentsfalling more

than once a year.1–3 Falls in nursing homes often lead to

serious injuries,with for example,an estimated hip frac-

ture incidencerate of 4% annually.3–5 Previousstudies

showed that, within 1 year after a fall-related hip fracture,

12% of residents incur a new fracture,and 31% die as a

result.5,6 Apart from the physicalburden,falls often have

psychologicalconsequencessuch as fear of falling and

poor quality of life.Falls also have a significant economic

burden.7,8

The Prevention ofFalls Network Europe (ProFaNE)

taxonomy divides fall prevention programs into three types:

single programs, which include one intervention component

From theaDepartment of Public Health and Primary Care, Health Services

and Nursing Research, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium;bVzw Rusthuizen

Zusters van Berlaar, Berlaar, Belgium;cNeuroscience Research Australia,

University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia;dRehabilitation

Sciences and Physiotherapy, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium;eInstitute

of Nursing Science, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland;fUnit for

Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease, Department of Rheumatology

and Endocrinology, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium;gDomus

Medica, Society of Flemish General Practitioners, Antwerpen, Belgium;

and hDivision of Geriatric Medicine, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven,

Belgium.

Address correspondence to Koen Milisen, KU Leuven, Department of

Public Health and Primary Care, Health Services and Nursing Research,

Kapucijnenvoer 35, 4th floor, P.B. 7001, Leuven 3000, Belgium.

E-mail: koen.milisen@med.kuleuven.be

DOI: 10.1111/jgs.13254

JAGS 63:211–221, 2015

© 2015, Copyright the Authors

Journal compilation © 2015, The American Geriatrics Society 0002-8614/15/$15.00

Characteristics and Effectiveness of Fall Prevention Programs

Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of

Randomized Controlled Trials

Ellen Vlaeyen, MSN,a Joke Coussement, MSN,a,b Greet Leysens, MSN,a Elisa Van der Elst, MSN,a

Kim Delbaere, MPT, PhD,c Dirk Cambier, MPT, PhD,d Kris Denhaerynck, MSN, PhD,e

Stefan Goemaere, MD,f Arlette Wertelaers, MD,g Fabienne Dobbels, PhD,a

Eddy Dejaeger, MD, PhD,h and Koen Milisen, MSN, PhD,a,h on behalf of the Center of Expertise

for Fall and Fracture Prevention Flanders

OBJECTIVES: To determine characteristics and effective-

ness of prevention programs on fall-related outcomes in a

defined setting.

DESIGN: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

SETTING: A clearly described subgroup of nursing homes

defined as residentialfacilities thatprovide 24-hour-a-day

surveillance,personalcare, and limited clinicalcare for

persons who are typically elderly and infirm.

PARTICIPANTS: Nursing home residents (N = 22,915).

MEASUREMENTS: The primary outcomes were number

of falls, fallers, and recurrent fallers.

RESULTS: Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria.

Six fall prevention programswere single (one interven-

tion componentprovided to the residents),one was mul-

tiple (two or more intervention components not

customized to individualfall risk), and six were multi-

factorial(two or more intervention componentscustom-

ized to each resident’sfall risk). Meta-analysisfound

significantlyfewer recurrentfallers in the intervention

groups(4 studies,relative risk (RR) = 0.79,95% confi-

dence interval(CI) = 0.65–0.97)but no significanteffect

of the interventionon fallers (6 studies, RR = 0.97,

95% CI = 0.84–1.11) or falls (10 studies,RR = 0.93,

95% CI = 0.76–1.13).Multifactorialinterventions signifi-

cantly reduced falls (4 studies, RR = 0.67, 95%

CI = 0.55–0.82)and the numberof recurrentfallers (4

studies,RR = 0.79, CI = 0.65–0.97),whereassingle or

multiple interventionsdid not. Training and education

showed a significantharmful effect in the intervention

groups on the number of falls (2 studies, RR = 1.29,

95% CI = 1.23–1.36).

CONCLUSION: This meta-analysisfailed to reveal a

significant effect of fall prevention interventions on falls or

fallers but,for the firsttime,showed thatfall prevention

interventions significantly reduced the number of recurrent

fallers by 21%. J Am Geriatr Soc 63:211–221, 2015.

Key words: accidentalfalls; prevention;multifactorial

interventions;residentialaged care facilities; meta-

analysis

Nursing home residents have a high risk of falling. The

average fallincidence is estimated to be 1.6 falls per

bed per year,with almosthalf of residentsfalling more

than once a year.1–3 Falls in nursing homes often lead to

serious injuries,with for example,an estimated hip frac-

ture incidencerate of 4% annually.3–5 Previousstudies

showed that, within 1 year after a fall-related hip fracture,

12% of residents incur a new fracture,and 31% die as a

result.5,6 Apart from the physicalburden,falls often have

psychologicalconsequencessuch as fear of falling and

poor quality of life.Falls also have a significant economic

burden.7,8

The Prevention ofFalls Network Europe (ProFaNE)

taxonomy divides fall prevention programs into three types:

single programs, which include one intervention component

From theaDepartment of Public Health and Primary Care, Health Services

and Nursing Research, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium;bVzw Rusthuizen

Zusters van Berlaar, Berlaar, Belgium;cNeuroscience Research Australia,

University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia;dRehabilitation

Sciences and Physiotherapy, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium;eInstitute

of Nursing Science, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland;fUnit for

Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease, Department of Rheumatology

and Endocrinology, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium;gDomus

Medica, Society of Flemish General Practitioners, Antwerpen, Belgium;

and hDivision of Geriatric Medicine, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven,

Belgium.

Address correspondence to Koen Milisen, KU Leuven, Department of

Public Health and Primary Care, Health Services and Nursing Research,

Kapucijnenvoer 35, 4th floor, P.B. 7001, Leuven 3000, Belgium.

E-mail: koen.milisen@med.kuleuven.be

DOI: 10.1111/jgs.13254

JAGS 63:211–221, 2015

© 2015, Copyright the Authors

Journal compilation © 2015, The American Geriatrics Society 0002-8614/15/$15.00

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

provided to all residents (e.g., supervised exercises); multiple

programs, which include two or more intervention compo-

nents provided to all residents (e.g., supervised exercise and

staff training);and multifactorialprograms,which include

two or more customized intervention components that tar-

get each resident’s fall risk profile.9 No conclusive evidence

exists on the effectiveness offall prevention programs in

nursing homes, partly because of differing study

approaches.10–16 For example,five of sevenpublished

reviewsused a narrativeapproach,10–14 one of which

reviewed only multifactorialinterventions.13 Two recent

systematic reviews15,16 used a meta-analyticalmethod and

reported no effectof any type of intervention,with the

exception of one single intervention that showed improve-

ment in number of falls and fallers after supplementing resi-

dents’ diets with vitamin D.15

These reviews did not distinguish between fallers and

recurrentfallers.This is a missed opportunity,given the

high frequency ofrecurrentfallers and their influence on

the total numberof falls. Furthermore,previousreviews

compared studies thatused heterogeneous groups ofresi-

dents from various care settings that had major differences

in care intensity or used vague terminology to define the

care settings (e.g.,residentialor nursing care facilities,13,15

nursing homes,10–12 care homes,16 and long-term care

facilities14). This could partly explain why evidenceon

effective fallprevention strategies in nursing homes is less

conclusive than reviewsspecifically focusing on a more-

clear-cut delineatedpopulation of community-dwelling

elderly adults.17

The current review aimed to determine the characteris-

tics and effectiveness of single, multiple, and multifactorial

fall prevention programson the numberof falls, fallers,

and recurrentfallers in older personswho permanently

reside in a nursing home.A nursing home was defined as

“a residentialfacility thatprovides 24-hour-a-day surveil-

lance,personalcare,and limited clinicalcare for persons

who are typically elderly and infirm” and excluded post-

hospitalskilled nursing care,rehabilitation,and long-term

care for younger people with illnesses,injuries,functional

disabilities, or cognitive impairment.7

METHODS

The review protocol was registeredon PROSPERO

(CRD42011001687)18 and conducted in concordance with

PRISMA guidelines.19,20

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search wasconducted in multiple

databases (MEDLINE,EMBASE, Cochrane CentralRegis-

ter of Controlled Trials,PEDro, CINAHL, SportDiscus),

restricting the search to articlespublished from database

inception to September2013. Depending on the selected

database,Medical SubjectHeadings,a thesaurus,or free

text was combined with theBoolean operators“AND/

OR” to build a search strategy.Search terms were “acci-

dental falls,” “falls,” “faller*,” “aged,” “older,” “elderly,”

“nursing homes,” “residential facilities,” “long-term care,”

“institutionalization,” “residential*,” and “prevention and

control.”

Relevantstudieswere identifiedusing three steps.

First, two independentreviewers(EV, JC) conducted an

initial study selection based on title and abstract.Second,

three reviewers (EV,JC, KM) obtained and examined full-

text copies ofall articles meeting initialselection criteria.

Disagreementwas resolved through discussion with three

additional reviewers (GL, EVdE, ED). Third, reference lists

of articles meeting the inclusion criteria were screened for

additional relevant papers.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies had to meet the following criteria.

Setting

The study had to be conducted in a nursing home,as

defined previously;7 other kinds of residential care facilities

were excluded. If the setting was in doubt, an attempt was

made to contact the authors for clarification. When studies

included nursing homes and other facilities (e.g.,assisted

living facilities),the study was included only when sepa-

rate results for the nursing home population were available

in the article.

Design

The study had to be an original or a priori secondary

analysisof individual-levelor cluster randomized con-

trolled trials (RCT).

Objective

The intervention had to include single,multiple,or multi-

factorial fall preventionprogramsdesignedto prevent

falls.

Outcomes

The study had to examine intervention effecton number

of falls, fallers, or recurrentfallers. The term “faller”

included all residents sustaining at least one fall during the

intervention or follow-up period.In the same way,recur-

rent fallers were defined asresidentssustaining two or

more falls.

Duration

The duration from the start of the intervention (including

follow-up) had to be 6 months or longer.

Language

Only publicationsin English, French,German,or Dutch

were considered.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The methodologicalquality of each study wasassessed

using the Cochrane methodologicalquality assessment

scheme(Table 1).21 One loss-to-follow-up criterion was

added and evaluated according to the question:“Were the

majority of participants stillin the sample atthe end of

the study?” Majority was operationally defined as 80% or

higher.

212 VLAEYEN ET AL. FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 JAGS

programs, which include two or more intervention compo-

nents provided to all residents (e.g., supervised exercise and

staff training);and multifactorialprograms,which include

two or more customized intervention components that tar-

get each resident’s fall risk profile.9 No conclusive evidence

exists on the effectiveness offall prevention programs in

nursing homes, partly because of differing study

approaches.10–16 For example,five of sevenpublished

reviewsused a narrativeapproach,10–14 one of which

reviewed only multifactorialinterventions.13 Two recent

systematic reviews15,16 used a meta-analyticalmethod and

reported no effectof any type of intervention,with the

exception of one single intervention that showed improve-

ment in number of falls and fallers after supplementing resi-

dents’ diets with vitamin D.15

These reviews did not distinguish between fallers and

recurrentfallers.This is a missed opportunity,given the

high frequency ofrecurrentfallers and their influence on

the total numberof falls. Furthermore,previousreviews

compared studies thatused heterogeneous groups ofresi-

dents from various care settings that had major differences

in care intensity or used vague terminology to define the

care settings (e.g.,residentialor nursing care facilities,13,15

nursing homes,10–12 care homes,16 and long-term care

facilities14). This could partly explain why evidenceon

effective fallprevention strategies in nursing homes is less

conclusive than reviewsspecifically focusing on a more-

clear-cut delineatedpopulation of community-dwelling

elderly adults.17

The current review aimed to determine the characteris-

tics and effectiveness of single, multiple, and multifactorial

fall prevention programson the numberof falls, fallers,

and recurrentfallers in older personswho permanently

reside in a nursing home.A nursing home was defined as

“a residentialfacility thatprovides 24-hour-a-day surveil-

lance,personalcare,and limited clinicalcare for persons

who are typically elderly and infirm” and excluded post-

hospitalskilled nursing care,rehabilitation,and long-term

care for younger people with illnesses,injuries,functional

disabilities, or cognitive impairment.7

METHODS

The review protocol was registeredon PROSPERO

(CRD42011001687)18 and conducted in concordance with

PRISMA guidelines.19,20

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search wasconducted in multiple

databases (MEDLINE,EMBASE, Cochrane CentralRegis-

ter of Controlled Trials,PEDro, CINAHL, SportDiscus),

restricting the search to articlespublished from database

inception to September2013. Depending on the selected

database,Medical SubjectHeadings,a thesaurus,or free

text was combined with theBoolean operators“AND/

OR” to build a search strategy.Search terms were “acci-

dental falls,” “falls,” “faller*,” “aged,” “older,” “elderly,”

“nursing homes,” “residential facilities,” “long-term care,”

“institutionalization,” “residential*,” and “prevention and

control.”

Relevantstudieswere identifiedusing three steps.

First, two independentreviewers(EV, JC) conducted an

initial study selection based on title and abstract.Second,

three reviewers (EV,JC, KM) obtained and examined full-

text copies ofall articles meeting initialselection criteria.

Disagreementwas resolved through discussion with three

additional reviewers (GL, EVdE, ED). Third, reference lists

of articles meeting the inclusion criteria were screened for

additional relevant papers.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies had to meet the following criteria.

Setting

The study had to be conducted in a nursing home,as

defined previously;7 other kinds of residential care facilities

were excluded. If the setting was in doubt, an attempt was

made to contact the authors for clarification. When studies

included nursing homes and other facilities (e.g.,assisted

living facilities),the study was included only when sepa-

rate results for the nursing home population were available

in the article.

Design

The study had to be an original or a priori secondary

analysisof individual-levelor cluster randomized con-

trolled trials (RCT).

Objective

The intervention had to include single,multiple,or multi-

factorial fall preventionprogramsdesignedto prevent

falls.

Outcomes

The study had to examine intervention effecton number

of falls, fallers, or recurrentfallers. The term “faller”

included all residents sustaining at least one fall during the

intervention or follow-up period.In the same way,recur-

rent fallers were defined asresidentssustaining two or

more falls.

Duration

The duration from the start of the intervention (including

follow-up) had to be 6 months or longer.

Language

Only publicationsin English, French,German,or Dutch

were considered.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The methodologicalquality of each study wasassessed

using the Cochrane methodologicalquality assessment

scheme(Table 1).21 One loss-to-follow-up criterion was

added and evaluated according to the question:“Were the

majority of participants stillin the sample atthe end of

the study?” Majority was operationally defined as 80% or

higher.

212 VLAEYEN ET AL. FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 JAGS

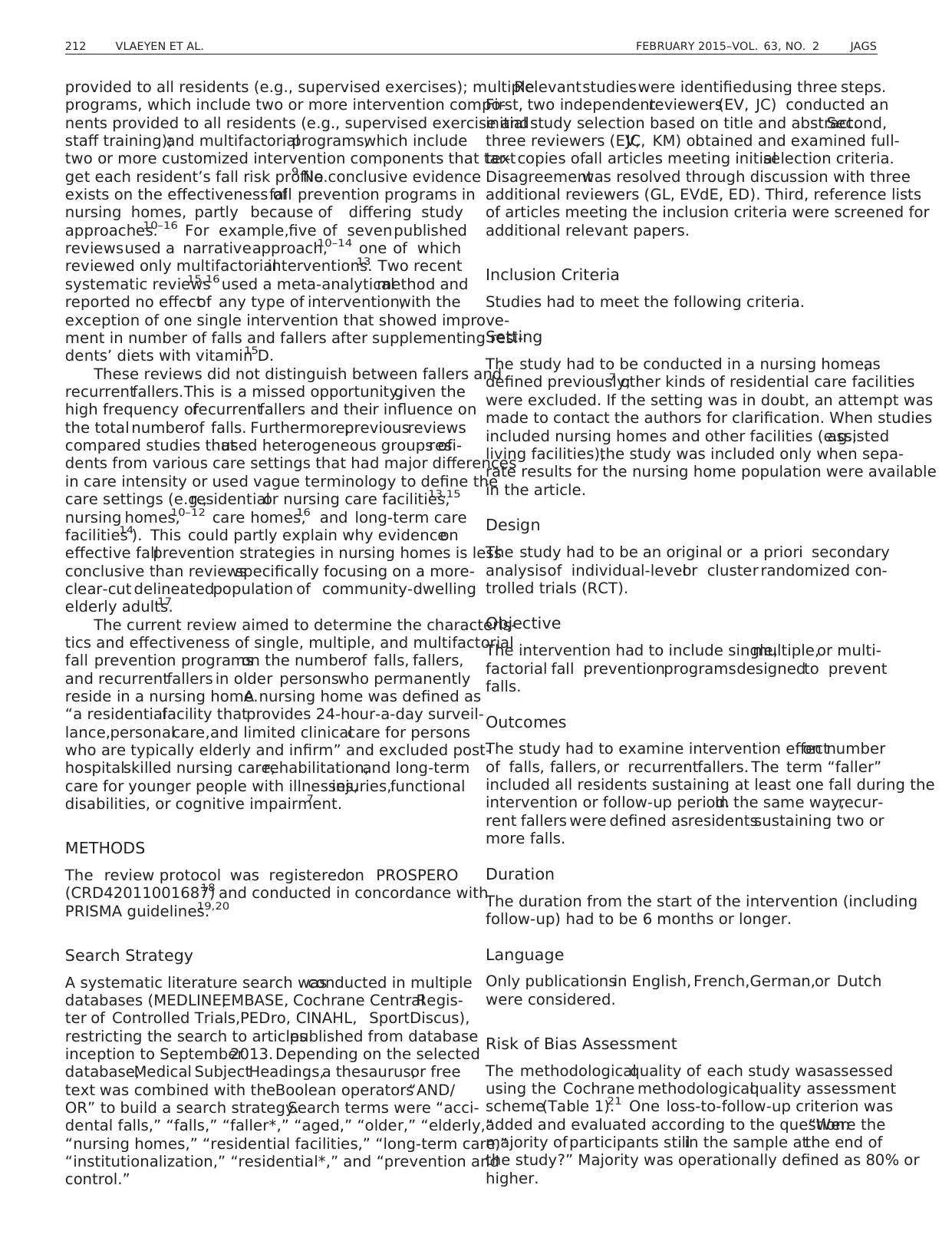

Table 1. Methodological Quality

Study

Fall Incident

Clearly

Defined and

Related to

Staff

Inclusion and

Exclusion

Criteria

Clearly

Defined

Blinded

Randomization

Treatment and

Control Groups

Comparable at

Baseline

Identical

Standard Care

Programs for

Both Groups

Blinded

Treatment

Providers

Blinded

Outcome

Assessors

Blinded

Subjects

Identical

Ascertainment

of Outcomes

Intention-

to-Treat

Analysis

Loss

to

Follow-

Upa

Total

Score

(0–22)

Becker34b 1 2 2 1 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 12

Cox27 0 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 6

Dyer36 0 2 2 1 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 11

Kerse37 2 2 2 2 0 0 2 0 2 2 0 14

Lapane29 1 2 0 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 6

Law31 0 2 2 2 0 0 1 0 2 2 0 11

McMurdo38 1 2 1 2 0 0 2 0 2 2 0 12

Neyens39 0 2 2 2 0 0 0 0 2 2 0 10

Patterson30 0 2 2 1 0 0 1 0 2 1 0 9

Rapp35b 1 2 2 2 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 9

Ray40 1 2 2 2 0 0 2 0 2 2 0 13

Schnelle33 1 2 2 2 0 0 2 0 2 0 0 11

Schoenfelder32 1 2 0 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 2 8

Ward28 0 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 2 2 0 7

Scores: 0 = not meeting the criterion, mentioned but unclear, or not mentioned; 1 = partially meeting the criterion; 2 = completely meeting the criterion.

a

Were the majority (≥80%) of participants still in the sample at the end of the study? Loss-to-follow-up was defined as participants who died, became terminally ill, or moved out of the nursing home d

study or follow-up period.

b

Same intervention described in both articles.

JAGS FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 EFFECT OF FALL PREVENTION IN NURSING HOMES 213

Study

Fall Incident

Clearly

Defined and

Related to

Staff

Inclusion and

Exclusion

Criteria

Clearly

Defined

Blinded

Randomization

Treatment and

Control Groups

Comparable at

Baseline

Identical

Standard Care

Programs for

Both Groups

Blinded

Treatment

Providers

Blinded

Outcome

Assessors

Blinded

Subjects

Identical

Ascertainment

of Outcomes

Intention-

to-Treat

Analysis

Loss

to

Follow-

Upa

Total

Score

(0–22)

Becker34b 1 2 2 1 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 12

Cox27 0 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 6

Dyer36 0 2 2 1 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 11

Kerse37 2 2 2 2 0 0 2 0 2 2 0 14

Lapane29 1 2 0 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 6

Law31 0 2 2 2 0 0 1 0 2 2 0 11

McMurdo38 1 2 1 2 0 0 2 0 2 2 0 12

Neyens39 0 2 2 2 0 0 0 0 2 2 0 10

Patterson30 0 2 2 1 0 0 1 0 2 1 0 9

Rapp35b 1 2 2 2 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 9

Ray40 1 2 2 2 0 0 2 0 2 2 0 13

Schnelle33 1 2 2 2 0 0 2 0 2 0 0 11

Schoenfelder32 1 2 0 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 2 8

Ward28 0 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 2 2 0 7

Scores: 0 = not meeting the criterion, mentioned but unclear, or not mentioned; 1 = partially meeting the criterion; 2 = completely meeting the criterion.

a

Were the majority (≥80%) of participants still in the sample at the end of the study? Loss-to-follow-up was defined as participants who died, became terminally ill, or moved out of the nursing home d

study or follow-up period.

b

Same intervention described in both articles.

JAGS FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 EFFECT OF FALL PREVENTION IN NURSING HOMES 213

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Five reviewers (EV,JC, KD, ED, KM) independently

scored methodologicalquality on a scale ranging from 0

to 2, depending on whether the criterion was not fulfilled

or not mentioned (0),partially met (1),or completely met

(2). The totalscore ranged between 0 and 22,with higher

scores indicating better quality. Disagreement was resolved

through discussion and consensus.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Data were synthesized to collate and summarize individual

study results.One reviewer (EV) collected data on charac-

teristics and effectiveness ofthe fall prevention programs.

Two reviewers (GL, EV & E) independently confirmed the

accuracy ofthe data synthesis.The ProFaNE taxonomy

for fall prevention interventions was used to classify and

describe the intervention programs.9 The programswere

categorized according to the ProFaNE taxonomy: interven-

tion type (single,multiple,or multifactorial) and interven-

tion component(e.g.,exercise,medication).9 Effectiveness

was classified according to outcome.For number offalls,

the relative risk offalls per residentyears was calculated

(ratio of the number of falls per resident year in the inter-

vention group to number offalls per residentyear in the

control group). For number of fallers and recurrent fallers,

the relativerisk was calculated (ratio ofproportion of

(recurrent)fallersin intervention group to corresponding

proportion in control group).

Effect size pooling was followed by regression analyses

using a random effectsapproach.22 Publication biaswas

checked using the trim and fillmethod,which alertsfor

publication bias ifmore than three studies on the funnel

plot are estimated to be concealed (assuming b > 0.80 and

a = 0.05).23,24 Heterogeneityof variance tests were

used to examinewhetherbetween-study variability was

significantly differentfrom 0 using weighted error sum of

squares Q.25 Calculated I² parameters reflected the propor-

tion of between-study variability to total variability.26

An a priori subgroup analysis was conducted accord-

ing to ProFaNE intervention type (single,multiple,multi-

factorial) and to determineany possible effects the

intervention mighthave had on residentswith dementia.

For the latter analysis, dementia was converted into a cate-

gorical variable,based on the methodology thatOliver

and colleagues used.16 Studies were categorized into three

groups ranging from 1 to 3 according to the prevalence of

dementia,with 1 being assigned to studies with less than

40% prevalence,2 being assigned to studies with a preva-

lence between 40% to 69%, and 3 being assigned to stud-

ies with 70% or more of residentswith dementia being

included in the study.Studies with an unspecified number

of participants with dementia were excluded from the sub-

group analysis.Regression analyseswere conducted to

determinewhetherdementia prevalencepredicted effect

size in this subgroup analysis.

RESULTS

Selected Studies

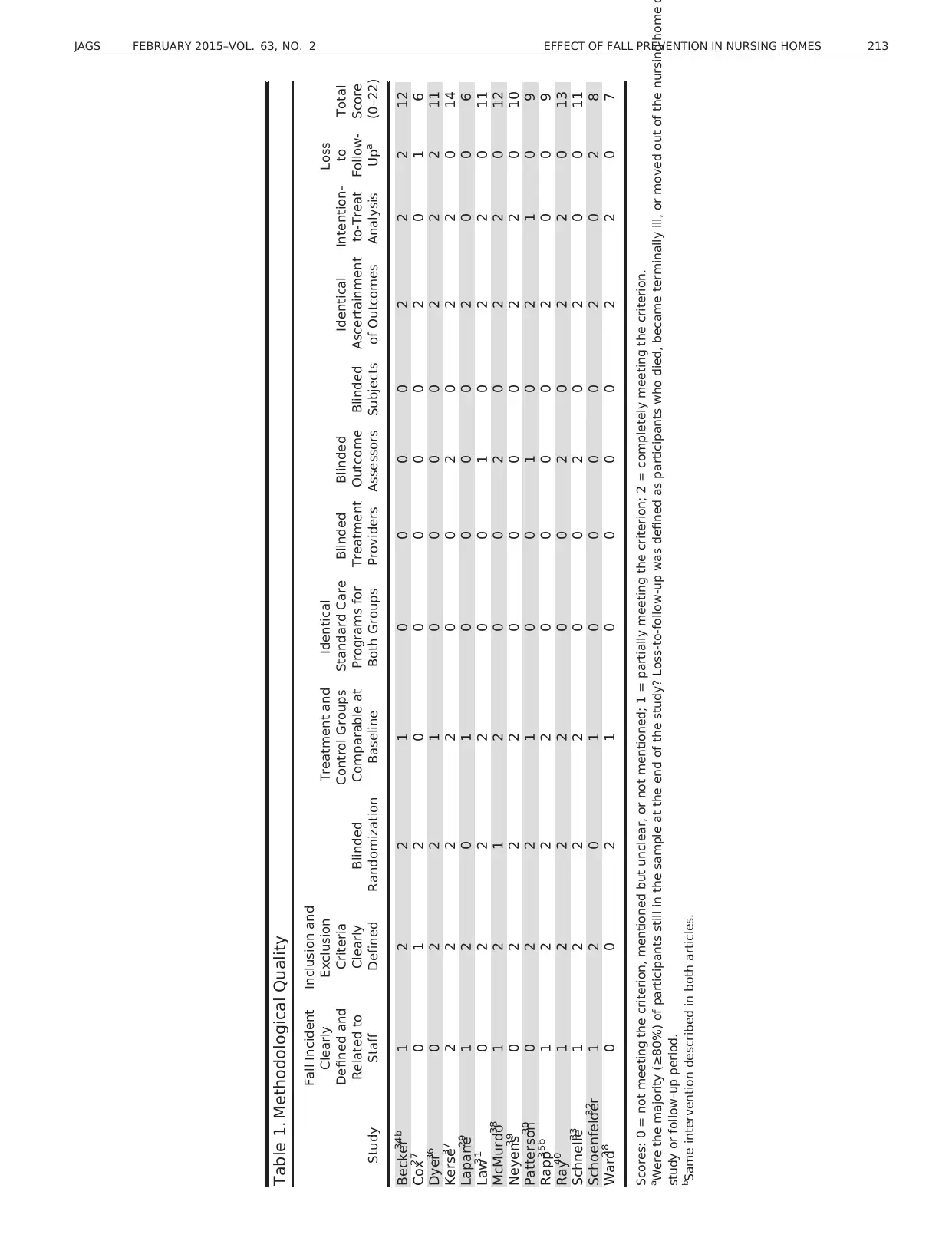

Figure 1 summarizes the results ofthe differentsteps for

identifying appropriatearticlesfor review.19,20 Fourteen

articles, describing 13 studies, met the inclusion criteria.27–40

Two studies34,35 were combined as one study in the meta-

analysis because they reported data on the same cohort of

individuals.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Overallquality scores ranged from 6 to 14 (Table 1).The

definition of a fall was reported in eight studies,29,32–

35,37,38,40

but in only one study was the definition clearly

explained to the staffcollecting and reporting the data.37

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were clearly defined in all

but two studies.27,28 None of the included studieshad

identical standard care programs for both intervention and

control groups, neither did they employ treatment blinding

for the treatment providers or participants. Outcome asses-

sors were blinded in fourstudies.33,37,38,40Eight studies

used intention-to-treatanalysis.28,31,34,36–40

The majority

of participants were stillin the sample atthe end ofthe

study in three studies.32,34,36

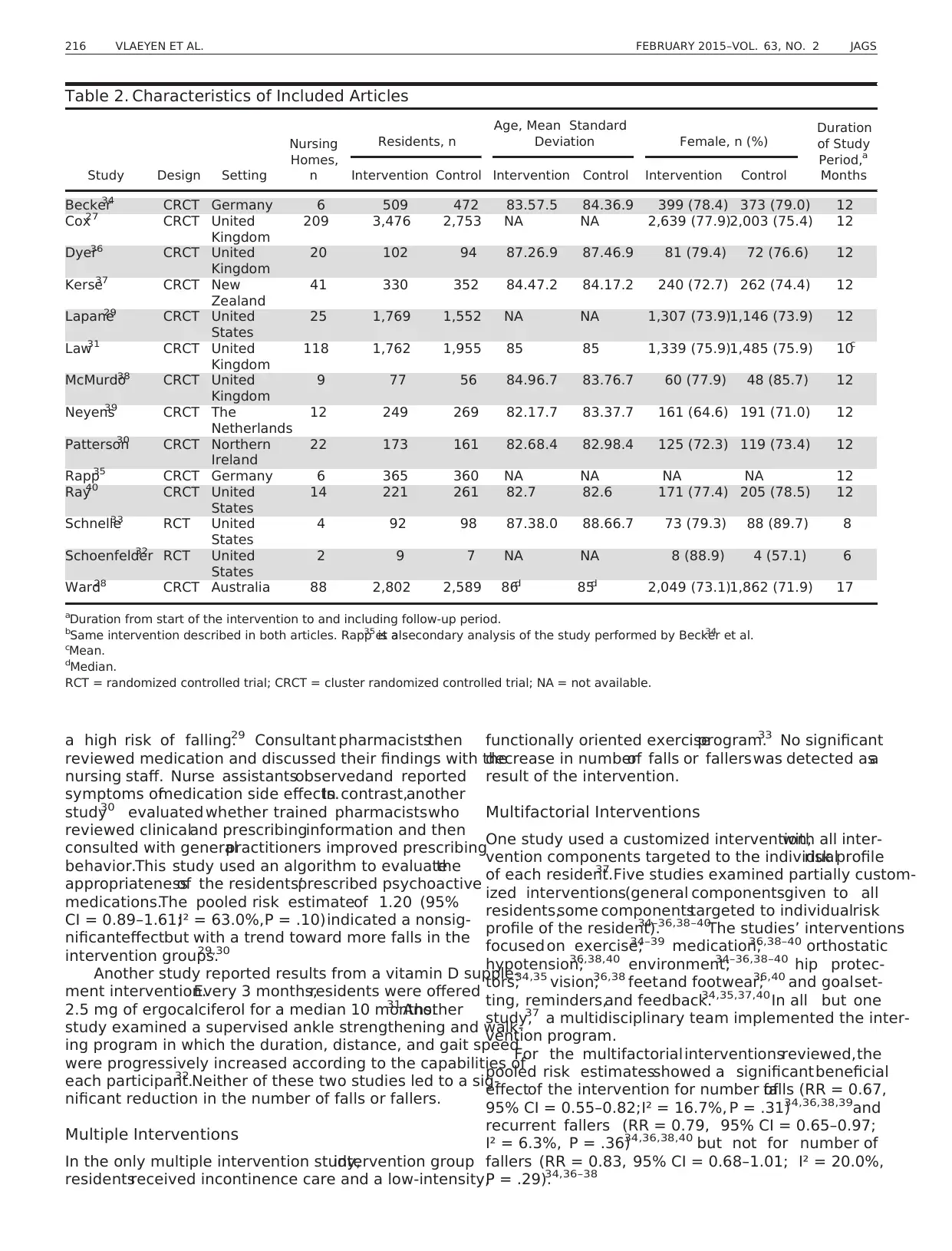

Study Characteristics

Seven studieswere conducted in Europe,27,30,31,34–36,38,39

four of which were in the United Kingdom.27,31,36,38

Four

were conducted in the United States29,32,33,40and two in

Australia/Oceania28,37 (Table 2). Follow-up ranged from

6 to 17 months. Two studieswere categorized asbeing

individualRCTs,32,33and 12 were cluster RCTs.27–31,34–40

With regard to ProFaNE intervention type,there were six

single,27–32 one multiple,33 and six multifactorial34–40 fall

prevention programs (Table 3).The included articles had

22,915 residents,with an overall mean age range of82

to 88.

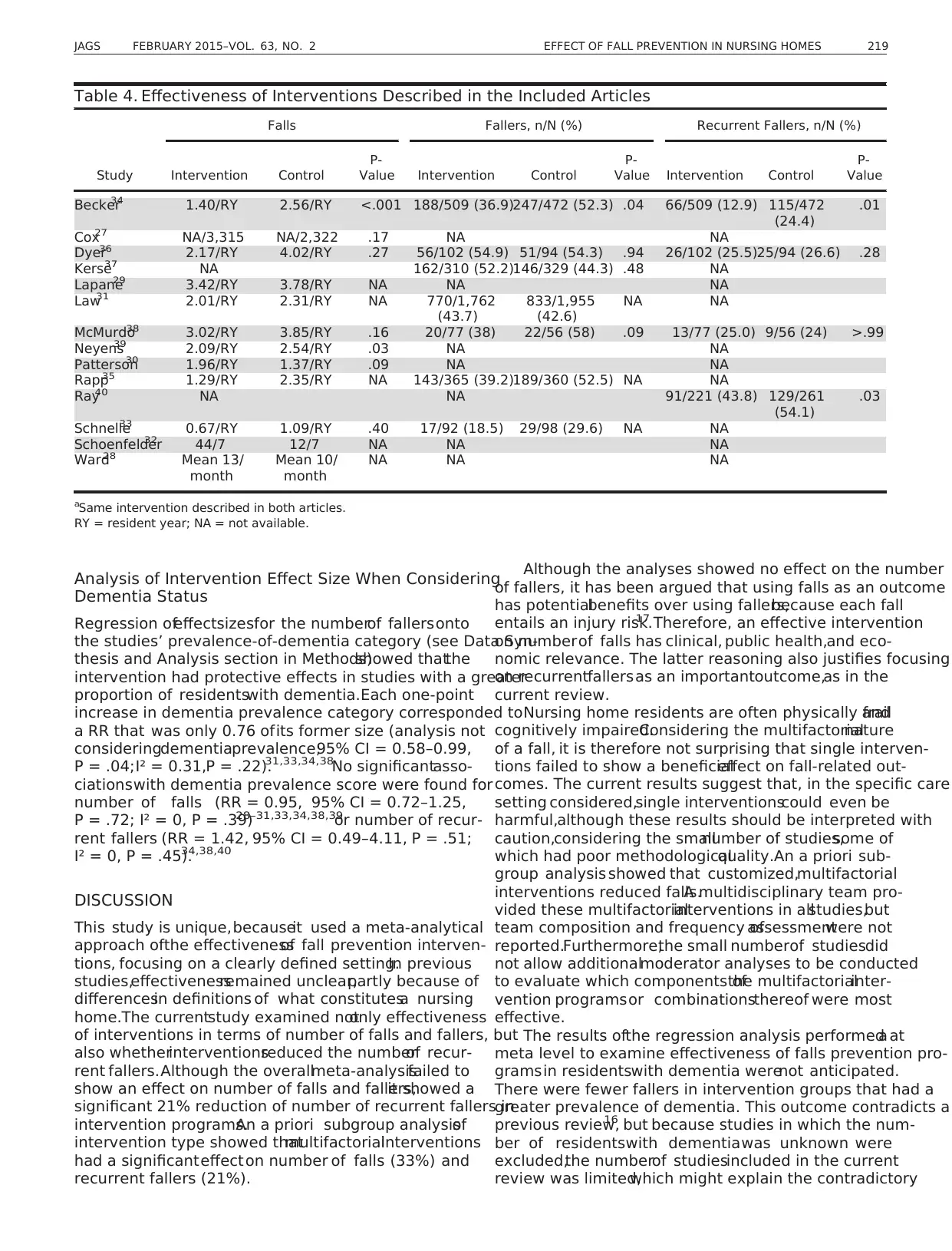

Overall Effects on Number of Falls, Fallers, and

Recurrent Fallers

The number of falls was reported in 12 studies

(Table 4).27–36,38,39In nine studies,the intervention and

control groupsdid not differ significantly in numberof

falls.27–33,36,38Two multifactorial studies34,39 showed a

significant decrease in falls of 36% and 45%,respectively,

over a 12-month period for the intervention groups.An a

priori secondarysubgroup analysis35 of one study34

showed thatthe effectwas only significantin cognitively

impaired residents(relative risk (RR) = 0.49,95% confi-

denceinterval (CI) = 0.35–0.69)and not in cognitively

intact residents (hazard rate (HR) = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.68–

1.22). Pooled data from 10 studies showed no effect

on number of falls (RR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.76–1.13;

I² = 89.8%, P < .001).27–31,33,34,36,38,39

Seven studies assessed the number of fallers as an out-

come measure,31,33–38of which two multifactorialstudies

showed significantly fewer fallers in the intervention group

than in the control group. These two studies reported

25%34 and 30%35 fewer fallers,although the pooled risk

estimatesfailed to demonstratea beneficialeffect of

the intervention on numberof fallers (RR = 0.97,95%

CI = 0.84–1.11; I² = 47.9%, P = .09).31,33,34,36–38

The number ofrecurrentfallers was assessed in four

multifactorialstudies.34,36,38,40One study34 described a

214 VLAEYEN ET AL. FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 JAGS

scored methodologicalquality on a scale ranging from 0

to 2, depending on whether the criterion was not fulfilled

or not mentioned (0),partially met (1),or completely met

(2). The totalscore ranged between 0 and 22,with higher

scores indicating better quality. Disagreement was resolved

through discussion and consensus.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Data were synthesized to collate and summarize individual

study results.One reviewer (EV) collected data on charac-

teristics and effectiveness ofthe fall prevention programs.

Two reviewers (GL, EV & E) independently confirmed the

accuracy ofthe data synthesis.The ProFaNE taxonomy

for fall prevention interventions was used to classify and

describe the intervention programs.9 The programswere

categorized according to the ProFaNE taxonomy: interven-

tion type (single,multiple,or multifactorial) and interven-

tion component(e.g.,exercise,medication).9 Effectiveness

was classified according to outcome.For number offalls,

the relative risk offalls per residentyears was calculated

(ratio of the number of falls per resident year in the inter-

vention group to number offalls per residentyear in the

control group). For number of fallers and recurrent fallers,

the relativerisk was calculated (ratio ofproportion of

(recurrent)fallersin intervention group to corresponding

proportion in control group).

Effect size pooling was followed by regression analyses

using a random effectsapproach.22 Publication biaswas

checked using the trim and fillmethod,which alertsfor

publication bias ifmore than three studies on the funnel

plot are estimated to be concealed (assuming b > 0.80 and

a = 0.05).23,24 Heterogeneityof variance tests were

used to examinewhetherbetween-study variability was

significantly differentfrom 0 using weighted error sum of

squares Q.25 Calculated I² parameters reflected the propor-

tion of between-study variability to total variability.26

An a priori subgroup analysis was conducted accord-

ing to ProFaNE intervention type (single,multiple,multi-

factorial) and to determineany possible effects the

intervention mighthave had on residentswith dementia.

For the latter analysis, dementia was converted into a cate-

gorical variable,based on the methodology thatOliver

and colleagues used.16 Studies were categorized into three

groups ranging from 1 to 3 according to the prevalence of

dementia,with 1 being assigned to studies with less than

40% prevalence,2 being assigned to studies with a preva-

lence between 40% to 69%, and 3 being assigned to stud-

ies with 70% or more of residentswith dementia being

included in the study.Studies with an unspecified number

of participants with dementia were excluded from the sub-

group analysis.Regression analyseswere conducted to

determinewhetherdementia prevalencepredicted effect

size in this subgroup analysis.

RESULTS

Selected Studies

Figure 1 summarizes the results ofthe differentsteps for

identifying appropriatearticlesfor review.19,20 Fourteen

articles, describing 13 studies, met the inclusion criteria.27–40

Two studies34,35 were combined as one study in the meta-

analysis because they reported data on the same cohort of

individuals.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Overallquality scores ranged from 6 to 14 (Table 1).The

definition of a fall was reported in eight studies,29,32–

35,37,38,40

but in only one study was the definition clearly

explained to the staffcollecting and reporting the data.37

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were clearly defined in all

but two studies.27,28 None of the included studieshad

identical standard care programs for both intervention and

control groups, neither did they employ treatment blinding

for the treatment providers or participants. Outcome asses-

sors were blinded in fourstudies.33,37,38,40Eight studies

used intention-to-treatanalysis.28,31,34,36–40

The majority

of participants were stillin the sample atthe end ofthe

study in three studies.32,34,36

Study Characteristics

Seven studieswere conducted in Europe,27,30,31,34–36,38,39

four of which were in the United Kingdom.27,31,36,38

Four

were conducted in the United States29,32,33,40and two in

Australia/Oceania28,37 (Table 2). Follow-up ranged from

6 to 17 months. Two studieswere categorized asbeing

individualRCTs,32,33and 12 were cluster RCTs.27–31,34–40

With regard to ProFaNE intervention type,there were six

single,27–32 one multiple,33 and six multifactorial34–40 fall

prevention programs (Table 3).The included articles had

22,915 residents,with an overall mean age range of82

to 88.

Overall Effects on Number of Falls, Fallers, and

Recurrent Fallers

The number of falls was reported in 12 studies

(Table 4).27–36,38,39In nine studies,the intervention and

control groupsdid not differ significantly in numberof

falls.27–33,36,38Two multifactorial studies34,39 showed a

significant decrease in falls of 36% and 45%,respectively,

over a 12-month period for the intervention groups.An a

priori secondarysubgroup analysis35 of one study34

showed thatthe effectwas only significantin cognitively

impaired residents(relative risk (RR) = 0.49,95% confi-

denceinterval (CI) = 0.35–0.69)and not in cognitively

intact residents (hazard rate (HR) = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.68–

1.22). Pooled data from 10 studies showed no effect

on number of falls (RR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.76–1.13;

I² = 89.8%, P < .001).27–31,33,34,36,38,39

Seven studies assessed the number of fallers as an out-

come measure,31,33–38of which two multifactorialstudies

showed significantly fewer fallers in the intervention group

than in the control group. These two studies reported

25%34 and 30%35 fewer fallers,although the pooled risk

estimatesfailed to demonstratea beneficialeffect of

the intervention on numberof fallers (RR = 0.97,95%

CI = 0.84–1.11; I² = 47.9%, P = .09).31,33,34,36–38

The number ofrecurrentfallers was assessed in four

multifactorialstudies.34,36,38,40One study34 described a

214 VLAEYEN ET AL. FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 JAGS

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

significant 44% reduction in the number of recurrent fallers

for the intervention group.In another study,40 the mean

proportion of recurrent fallers was 19% lower in the inter-

vention facilities than in the controlfacilities.The pooled

estimate showed significantly fewer recurrent fallers in the

intervention groups than in the control groups (RR = 0.79,

95% CI = 0.65–0.97; I² = 6.3%, P = .36).34,36,38,40

Because

only four of 13 included studies assessed recurrent fallers as

an outcome measure, an additional sensitivity analysis was

performed for the three studies34,36,38that also reported on

the outcomes“falls” and “fallers” (the other study40

reported only recurrentfallers)to determine whether the

results for those two outcomes were concordantwith the

outcome for “recurrent fallers.” Pooled data showed a sig-

nificant effect of intervention on number of falls

(RR = 0.64,95% CI = 0.50–0.81;I² = 24.1%, P = .27)

and a nonsignificant effect on number of fallers (RR = 0.82,

95% CI = 0.67–1.01; I² = 18.6%, P = .29).

The trim-and-fillanalysis did notrevealany publica-

tion bias for the above analyses.23

Characteristics and Effects of Different Types of

Interventions

Single Interventions

Two studies examined the effect of staff training and educa-

tion that focused on dissemination of information on falls

prevention,27,28fall risk assessment and potential modifica-

tions of risk factors,27,28and postfall management review.28

Pooled risk estimates showed that the intervention groups

had significantlymore falls than the control group

(RR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.23–1.36; I² = 0%, P = .49).27,28

Two other studies evaluatedmedicationinterven-

tions.29,30 One used health information technologyto

analyze medication use in order to identify residents with

Potentially relevant articles identified and screened for retrieval

(n = 1,131)

Articles excluded on the basis of title and abstract (total n = 1,022)

- Setting: not conducted in a nursing home (n = 244)

- Study design: no original/preplanned secondary analyses of RCT (n = 348)

- Study objective: not designed to prevent falls (n = 402)

- No relevant outcomes on number of falls, fallers, or recurrent fallers (n = 19)

- Duration from the start of the intervention was less than 6 months (n = 2)

- Language: not English, French, German, or Dutch (n = 7)

Articles retrieved for full-text assessment of eligibility

(n = 109)

Articles excluded based on application of inclusion criteria (total n = 95)

- Setting: not conducted in a nursing home (n = 22)

- Study design: no original/preplanned secondary analyses of RCT (n = 38)

- Study objective: not designed to prevent falls (n = 28)

- No relevant outcomes on number of falls, fallers, or recurrent fallers (n = 3)

- Duration from the start of the intervention was less than 6 months (n = 3)

- Language: not English, French, German, or Dutch (n = 1)

Articles included in the manuscript for analysis (qualitative synthesis)

(n = 14)

Combined search results of all electronic databases: (total n = 1,424)

- MEDLINE (n = 574)

- EMBASE (n = 269)

- CINAHL (n = 90)

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (n = 304)

- SportDiscus (n = 85)

- PEDro (n = 102)

Excluded duplicates (n = 293)

Articles excluded for meta-analyses (n = 1)

- Rapp et al.35 reported a preplanned secondary analysis of Becker et al .34

and was excluded for the meta-analyses

Studies included in meta-analysis (quantitative synthesis)

(n = 13)

Additional articles by manual search of references (n = 0)

Figure 1.Flow diagram of study selection. RCT = randomized controlled trial.

JAGS FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 EFFECT OF FALL PREVENTION IN NURSING HOMES 215

for the intervention group.In another study,40 the mean

proportion of recurrent fallers was 19% lower in the inter-

vention facilities than in the controlfacilities.The pooled

estimate showed significantly fewer recurrent fallers in the

intervention groups than in the control groups (RR = 0.79,

95% CI = 0.65–0.97; I² = 6.3%, P = .36).34,36,38,40

Because

only four of 13 included studies assessed recurrent fallers as

an outcome measure, an additional sensitivity analysis was

performed for the three studies34,36,38that also reported on

the outcomes“falls” and “fallers” (the other study40

reported only recurrentfallers)to determine whether the

results for those two outcomes were concordantwith the

outcome for “recurrent fallers.” Pooled data showed a sig-

nificant effect of intervention on number of falls

(RR = 0.64,95% CI = 0.50–0.81;I² = 24.1%, P = .27)

and a nonsignificant effect on number of fallers (RR = 0.82,

95% CI = 0.67–1.01; I² = 18.6%, P = .29).

The trim-and-fillanalysis did notrevealany publica-

tion bias for the above analyses.23

Characteristics and Effects of Different Types of

Interventions

Single Interventions

Two studies examined the effect of staff training and educa-

tion that focused on dissemination of information on falls

prevention,27,28fall risk assessment and potential modifica-

tions of risk factors,27,28and postfall management review.28

Pooled risk estimates showed that the intervention groups

had significantlymore falls than the control group

(RR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.23–1.36; I² = 0%, P = .49).27,28

Two other studies evaluatedmedicationinterven-

tions.29,30 One used health information technologyto

analyze medication use in order to identify residents with

Potentially relevant articles identified and screened for retrieval

(n = 1,131)

Articles excluded on the basis of title and abstract (total n = 1,022)

- Setting: not conducted in a nursing home (n = 244)

- Study design: no original/preplanned secondary analyses of RCT (n = 348)

- Study objective: not designed to prevent falls (n = 402)

- No relevant outcomes on number of falls, fallers, or recurrent fallers (n = 19)

- Duration from the start of the intervention was less than 6 months (n = 2)

- Language: not English, French, German, or Dutch (n = 7)

Articles retrieved for full-text assessment of eligibility

(n = 109)

Articles excluded based on application of inclusion criteria (total n = 95)

- Setting: not conducted in a nursing home (n = 22)

- Study design: no original/preplanned secondary analyses of RCT (n = 38)

- Study objective: not designed to prevent falls (n = 28)

- No relevant outcomes on number of falls, fallers, or recurrent fallers (n = 3)

- Duration from the start of the intervention was less than 6 months (n = 3)

- Language: not English, French, German, or Dutch (n = 1)

Articles included in the manuscript for analysis (qualitative synthesis)

(n = 14)

Combined search results of all electronic databases: (total n = 1,424)

- MEDLINE (n = 574)

- EMBASE (n = 269)

- CINAHL (n = 90)

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (n = 304)

- SportDiscus (n = 85)

- PEDro (n = 102)

Excluded duplicates (n = 293)

Articles excluded for meta-analyses (n = 1)

- Rapp et al.35 reported a preplanned secondary analysis of Becker et al .34

and was excluded for the meta-analyses

Studies included in meta-analysis (quantitative synthesis)

(n = 13)

Additional articles by manual search of references (n = 0)

Figure 1.Flow diagram of study selection. RCT = randomized controlled trial.

JAGS FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 EFFECT OF FALL PREVENTION IN NURSING HOMES 215

a high risk of falling.29 Consultant pharmaciststhen

reviewed medication and discussed their findings with the

nursing staff. Nurse assistantsobservedand reported

symptoms ofmedication side effects.In contrast,another

study30 evaluated whether trained pharmacistswho

reviewed clinicaland prescribinginformation and then

consulted with generalpractitioners improved prescribing

behavior.This study used an algorithm to evaluatethe

appropriatenessof the residents’prescribed psychoactive

medications.The pooled risk estimateof 1.20 (95%

CI = 0.89–1.61;I² = 63.0%,P = .10)indicated a nonsig-

nificanteffectbut with a trend toward more falls in the

intervention groups.29,30

Another study reported results from a vitamin D supple-

ment intervention.Every 3 months,residents were offered

2.5 mg of ergocalciferol for a median 10 months.31 Another

study examined a supervised ankle strengthening and walk-

ing program in which the duration, distance, and gait speed

were progressively increased according to the capabilities of

each participant.32 Neither of these two studies led to a sig-

nificant reduction in the number of falls or fallers.

Multiple Interventions

In the only multiple intervention study,intervention group

residentsreceived incontinence care and a low-intensity,

functionally oriented exerciseprogram.33 No significant

decrease in numberof falls or fallerswas detected asa

result of the intervention.

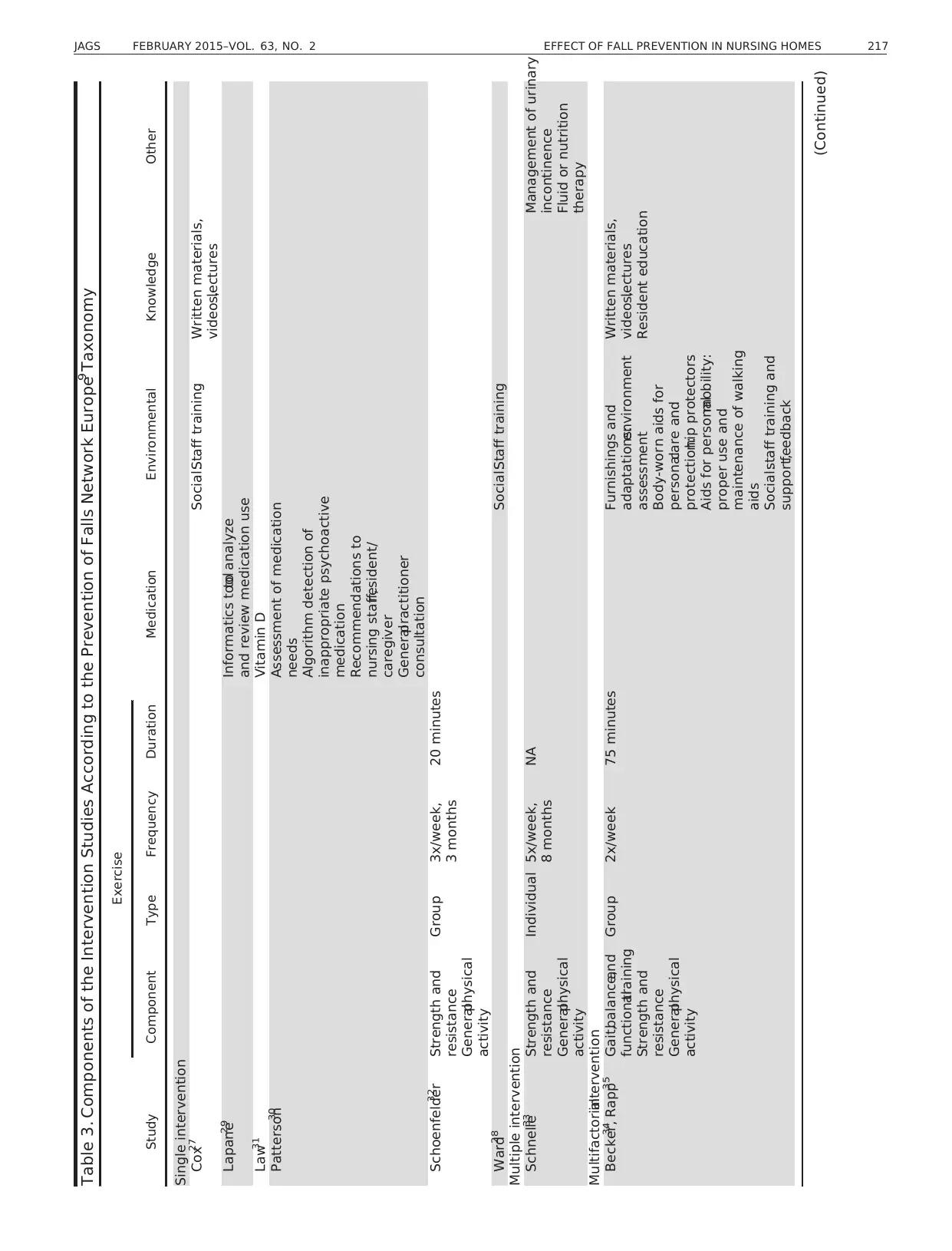

Multifactorial Interventions

One study used a customized intervention,with all inter-

vention components targeted to the individualrisk profile

of each resident.37 Five studies examined partially custom-

ized interventions(general componentsgiven to all

residents,some componentstargeted to individualrisk

profile of the resident).34–36,38–40

The studies’ interventions

focused on exercise;34–39 medication;36,38–40 orthostatic

hypotension;36,38,40 environment;34–36,38–40 hip protec-

tors;34,35 vision;36,38 feetand footwear;36,40 and goalset-

ting, reminders,and feedback.34,35,37,40In all but one

study,37 a multidisciplinary team implemented the inter-

vention program.

For the multifactorialinterventionsreviewed,the

pooled risk estimatesshowed a significantbeneficial

effectof the intervention for number offalls (RR = 0.67,

95% CI = 0.55–0.82;I² = 16.7%, P = .31)34,36,38,39and

recurrent fallers (RR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.65–0.97;

I² = 6.3%, P = .36)34,36,38,40 but not for number of

fallers (RR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.68–1.01; I² = 20.0%,

P = .29).34,36–38

Table 2. Characteristics of Included Articles

Study Design Setting

Nursing

Homes,

n

Residents, n

Age, Mean Standard

Deviation Female, n (%)

Duration

of Study

Period,a

MonthsIntervention Control Intervention Control Intervention Control

Becker34 CRCT Germany 6 509 472 83.57.5 84.36.9 399 (78.4) 373 (79.0) 12

Cox27 CRCT United

Kingdom

209 3,476 2,753 NA NA 2,639 (77.9)2,003 (75.4) 12

Dyer36 CRCT United

Kingdom

20 102 94 87.26.9 87.46.9 81 (79.4) 72 (76.6) 12

Kerse37 CRCT New

Zealand

41 330 352 84.47.2 84.17.2 240 (72.7) 262 (74.4) 12

Lapane29 CRCT United

States

25 1,769 1,552 NA NA 1,307 (73.9)1,146 (73.9) 12

Law31 CRCT United

Kingdom

118 1,762 1,955 85 85 1,339 (75.9)1,485 (75.9) 10c

McMurdo38 CRCT United

Kingdom

9 77 56 84.96.7 83.76.7 60 (77.9) 48 (85.7) 12

Neyens39 CRCT The

Netherlands

12 249 269 82.17.7 83.37.7 161 (64.6) 191 (71.0) 12

Patterson30 CRCT Northern

Ireland

22 173 161 82.68.4 82.98.4 125 (72.3) 119 (73.4) 12

Rapp35 CRCT Germany 6 365 360 NA NA NA NA 12

Ray40 CRCT United

States

14 221 261 82.7 82.6 171 (77.4) 205 (78.5) 12

Schnelle33 RCT United

States

4 92 98 87.38.0 88.66.7 73 (79.3) 88 (89.7) 8

Schoenfelder32 RCT United

States

2 9 7 NA NA 8 (88.9) 4 (57.1) 6

Ward28 CRCT Australia 88 2,802 2,589 86d 85d 2,049 (73.1)1,862 (71.9) 17

aDuration from start of the intervention to and including follow-up period.

bSame intervention described in both articles. Rapp et al.35 is a secondary analysis of the study performed by Becker et al.34

cMean.

dMedian.

RCT = randomized controlled trial; CRCT = cluster randomized controlled trial; NA = not available.

216 VLAEYEN ET AL. FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 JAGS

reviewed medication and discussed their findings with the

nursing staff. Nurse assistantsobservedand reported

symptoms ofmedication side effects.In contrast,another

study30 evaluated whether trained pharmacistswho

reviewed clinicaland prescribinginformation and then

consulted with generalpractitioners improved prescribing

behavior.This study used an algorithm to evaluatethe

appropriatenessof the residents’prescribed psychoactive

medications.The pooled risk estimateof 1.20 (95%

CI = 0.89–1.61;I² = 63.0%,P = .10)indicated a nonsig-

nificanteffectbut with a trend toward more falls in the

intervention groups.29,30

Another study reported results from a vitamin D supple-

ment intervention.Every 3 months,residents were offered

2.5 mg of ergocalciferol for a median 10 months.31 Another

study examined a supervised ankle strengthening and walk-

ing program in which the duration, distance, and gait speed

were progressively increased according to the capabilities of

each participant.32 Neither of these two studies led to a sig-

nificant reduction in the number of falls or fallers.

Multiple Interventions

In the only multiple intervention study,intervention group

residentsreceived incontinence care and a low-intensity,

functionally oriented exerciseprogram.33 No significant

decrease in numberof falls or fallerswas detected asa

result of the intervention.

Multifactorial Interventions

One study used a customized intervention,with all inter-

vention components targeted to the individualrisk profile

of each resident.37 Five studies examined partially custom-

ized interventions(general componentsgiven to all

residents,some componentstargeted to individualrisk

profile of the resident).34–36,38–40

The studies’ interventions

focused on exercise;34–39 medication;36,38–40 orthostatic

hypotension;36,38,40 environment;34–36,38–40 hip protec-

tors;34,35 vision;36,38 feetand footwear;36,40 and goalset-

ting, reminders,and feedback.34,35,37,40In all but one

study,37 a multidisciplinary team implemented the inter-

vention program.

For the multifactorialinterventionsreviewed,the

pooled risk estimatesshowed a significantbeneficial

effectof the intervention for number offalls (RR = 0.67,

95% CI = 0.55–0.82;I² = 16.7%, P = .31)34,36,38,39and

recurrent fallers (RR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.65–0.97;

I² = 6.3%, P = .36)34,36,38,40 but not for number of

fallers (RR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.68–1.01; I² = 20.0%,

P = .29).34,36–38

Table 2. Characteristics of Included Articles

Study Design Setting

Nursing

Homes,

n

Residents, n

Age, Mean Standard

Deviation Female, n (%)

Duration

of Study

Period,a

MonthsIntervention Control Intervention Control Intervention Control

Becker34 CRCT Germany 6 509 472 83.57.5 84.36.9 399 (78.4) 373 (79.0) 12

Cox27 CRCT United

Kingdom

209 3,476 2,753 NA NA 2,639 (77.9)2,003 (75.4) 12

Dyer36 CRCT United

Kingdom

20 102 94 87.26.9 87.46.9 81 (79.4) 72 (76.6) 12

Kerse37 CRCT New

Zealand

41 330 352 84.47.2 84.17.2 240 (72.7) 262 (74.4) 12

Lapane29 CRCT United

States

25 1,769 1,552 NA NA 1,307 (73.9)1,146 (73.9) 12

Law31 CRCT United

Kingdom

118 1,762 1,955 85 85 1,339 (75.9)1,485 (75.9) 10c

McMurdo38 CRCT United

Kingdom

9 77 56 84.96.7 83.76.7 60 (77.9) 48 (85.7) 12

Neyens39 CRCT The

Netherlands

12 249 269 82.17.7 83.37.7 161 (64.6) 191 (71.0) 12

Patterson30 CRCT Northern

Ireland

22 173 161 82.68.4 82.98.4 125 (72.3) 119 (73.4) 12

Rapp35 CRCT Germany 6 365 360 NA NA NA NA 12

Ray40 CRCT United

States

14 221 261 82.7 82.6 171 (77.4) 205 (78.5) 12

Schnelle33 RCT United

States

4 92 98 87.38.0 88.66.7 73 (79.3) 88 (89.7) 8

Schoenfelder32 RCT United

States

2 9 7 NA NA 8 (88.9) 4 (57.1) 6

Ward28 CRCT Australia 88 2,802 2,589 86d 85d 2,049 (73.1)1,862 (71.9) 17

aDuration from start of the intervention to and including follow-up period.

bSame intervention described in both articles. Rapp et al.35 is a secondary analysis of the study performed by Becker et al.34

cMean.

dMedian.

RCT = randomized controlled trial; CRCT = cluster randomized controlled trial; NA = not available.

216 VLAEYEN ET AL. FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 JAGS

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Table 3. Components of the Intervention Studies According to the Prevention of Falls Network Europe Taxonomy9

Study

Exercise

Medication Environmental Knowledge OtherComponent Type Frequency Duration

Single intervention

Cox27 Social:Staff training Written materials,

videos,lectures

Lapane29 Informatics toolto analyze

and review medication use

Law31 Vitamin D

Patterson30 Assessment of medication

needs

Algorithm detection of

inappropriate psychoactive

medication

Recommendations to

nursing staff,resident/

caregiver

Generalpractitioner

consultation

Schoenfelder32 Strength and

resistance

Generalphysical

activity

Group 3x/week,

3 months

20 minutes

Ward28 Social:Staff training

Multiple intervention

Schnelle33 Strength and

resistance

Generalphysical

activity

Individual 5x/week,

8 months

NA Management of urinary

incontinence

Fluid or nutrition

therapy

Multifactorialintervention

Becker34

, Rapp35 Gait,balance,and

functionaltraining

Strength and

resistance

Generalphysical

activity

Group 2x/week 75 minutes Furnishings and

adaptations:environment

assessment

Body-worn aids for

personalcare and

protection:hip protectors

Aids for personalmobility:

proper use and

maintenance of walking

aids

Social:staff training and

support,feedback

Written materials,

videos,lectures

Resident education

(Continued)

JAGS FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 EFFECT OF FALL PREVENTION IN NURSING HOMES 217

Study

Exercise

Medication Environmental Knowledge OtherComponent Type Frequency Duration

Single intervention

Cox27 Social:Staff training Written materials,

videos,lectures

Lapane29 Informatics toolto analyze

and review medication use

Law31 Vitamin D

Patterson30 Assessment of medication

needs

Algorithm detection of

inappropriate psychoactive

medication

Recommendations to

nursing staff,resident/

caregiver

Generalpractitioner

consultation

Schoenfelder32 Strength and

resistance

Generalphysical

activity

Group 3x/week,

3 months

20 minutes

Ward28 Social:Staff training

Multiple intervention

Schnelle33 Strength and

resistance

Generalphysical

activity

Individual 5x/week,

8 months

NA Management of urinary

incontinence

Fluid or nutrition

therapy

Multifactorialintervention

Becker34

, Rapp35 Gait,balance,and

functionaltraining

Strength and

resistance

Generalphysical

activity

Group 2x/week 75 minutes Furnishings and

adaptations:environment

assessment

Body-worn aids for

personalcare and

protection:hip protectors

Aids for personalmobility:

proper use and

maintenance of walking

aids

Social:staff training and

support,feedback

Written materials,

videos,lectures

Resident education

(Continued)

JAGS FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 EFFECT OF FALL PREVENTION IN NURSING HOMES 217

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

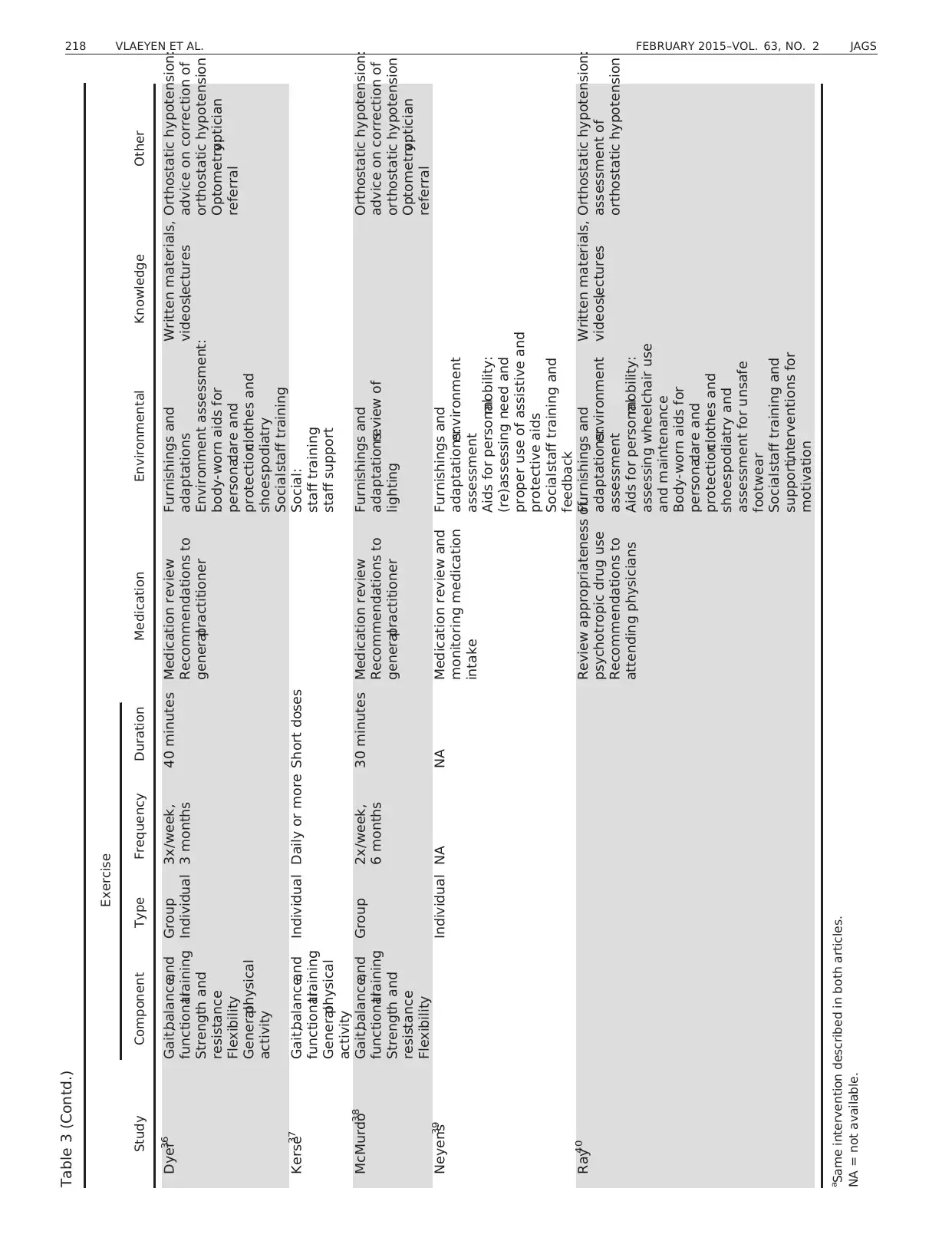

Table 3 (Contd.)

Study

Exercise

Medication Environmental Knowledge OtherComponent Type Frequency Duration

Dyer36 Gait,balance,and

functionaltraining

Strength and

resistance

Flexibility

Generalphysical

activity

Group

Individual

3x/week,

3 months

40 minutes Medication review

Recommendations to

generalpractitioner

Furnishings and

adaptations

Environment assessment:

body-worn aids for

personalcare and

protection:clothes and

shoes:podiatry

Social:staff training

Written materials,

videos,lectures

Orthostatic hypotension:

advice on correction of

orthostatic hypotension

Optometry:optician

referral

Kerse37 Gait,balance,and

functionaltraining

Generalphysical

activity

Individual Daily or more Short doses Social:

staff training

staff support

McMurdo38 Gait,balance,and

functionaltraining

Strength and

resistance

Flexibility

Group 2x/week,

6 months

30 minutes Medication review

Recommendations to

generalpractitioner

Furnishings and

adaptations:review of

lighting

Orthostatic hypotension:

advice on correction of

orthostatic hypotension

Optometry:optician

referral

Neyens39 Individual NA NA Medication review and

monitoring medication

intake

Furnishings and

adaptations:environment

assessment

Aids for personalmobility:

(re)assessing need and

proper use of assistive and

protective aids

Social:staff training and

feedback

Ray40 Review appropriateness of

psychotropic drug use

Recommendations to

attending physicians

Furnishings and

adaptations:environment

assessment

Aids for personalmobility:

assessing wheelchair use

and maintenance

Body-worn aids for

personalcare and

protection:clothes and

shoes:podiatry and

assessment for unsafe

footwear

Social:staff training and

support,interventions for

motivation

Written materials,

videos,lectures

Orthostatic hypotension:

assessment of

orthostatic hypotension

a

Same intervention described in both articles.

NA = not available.

218 VLAEYEN ET AL. FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 JAGS

Study

Exercise

Medication Environmental Knowledge OtherComponent Type Frequency Duration

Dyer36 Gait,balance,and

functionaltraining

Strength and

resistance

Flexibility

Generalphysical

activity

Group

Individual

3x/week,

3 months

40 minutes Medication review

Recommendations to

generalpractitioner

Furnishings and

adaptations

Environment assessment:

body-worn aids for

personalcare and

protection:clothes and

shoes:podiatry

Social:staff training

Written materials,

videos,lectures

Orthostatic hypotension:

advice on correction of

orthostatic hypotension

Optometry:optician

referral

Kerse37 Gait,balance,and

functionaltraining

Generalphysical

activity

Individual Daily or more Short doses Social:

staff training

staff support

McMurdo38 Gait,balance,and

functionaltraining

Strength and

resistance

Flexibility

Group 2x/week,

6 months

30 minutes Medication review

Recommendations to

generalpractitioner

Furnishings and

adaptations:review of

lighting

Orthostatic hypotension:

advice on correction of

orthostatic hypotension

Optometry:optician

referral

Neyens39 Individual NA NA Medication review and

monitoring medication

intake

Furnishings and

adaptations:environment

assessment

Aids for personalmobility:

(re)assessing need and

proper use of assistive and

protective aids

Social:staff training and

feedback

Ray40 Review appropriateness of

psychotropic drug use

Recommendations to

attending physicians

Furnishings and

adaptations:environment

assessment

Aids for personalmobility:

assessing wheelchair use

and maintenance

Body-worn aids for

personalcare and

protection:clothes and

shoes:podiatry and

assessment for unsafe

footwear

Social:staff training and

support,interventions for

motivation

Written materials,

videos,lectures

Orthostatic hypotension:

assessment of

orthostatic hypotension

a

Same intervention described in both articles.

NA = not available.

218 VLAEYEN ET AL. FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 JAGS

Analysis of Intervention Effect Size When Considering

Dementia Status

Regression ofeffectsizesfor the numberof fallersonto

the studies’ prevalence-of-dementia category (see Data Syn-

thesis and Analysis section in Methods)showed thatthe

intervention had protective effects in studies with a greater

proportion of residentswith dementia.Each one-point

increase in dementia prevalence category corresponded to

a RR that was only 0.76 ofits former size (analysis not

consideringdementiaprevalence;95% CI = 0.58–0.99,

P = .04;I² = 0.31,P = .22).31,33,34,38No significantasso-

ciationswith dementia prevalence score were found for

number of falls (RR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.72–1.25,

P = .72; I² = 0, P = .39)28–31,33,34,38,39

or number of recur-

rent fallers (RR = 1.42, 95% CI = 0.49–4.11, P = .51;

I² = 0, P = .45).34,38,40

DISCUSSION

This study is unique,becauseit used a meta-analytical

approach ofthe effectivenessof fall prevention interven-

tions, focusing on a clearly defined setting.In previous

studies,effectivenessremained unclear,partly because of

differencesin definitions of what constitutesa nursing

home.The currentstudy examined notonly effectiveness

of interventions in terms of number of falls and fallers, but

also whetherinterventionsreduced the numberof recur-

rent fallers.Although the overallmeta-analysisfailed to

show an effect on number of falls and fallers,it showed a

significant 21% reduction of number of recurrent fallers in

intervention programs.An a priori subgroup analysisof

intervention type showed thatmultifactorialinterventions

had a significanteffecton number of falls (33%) and

recurrent fallers (21%).

Although the analyses showed no effect on the number

of fallers, it has been argued that using falls as an outcome

has potentialbenefits over using fallers,because each fall

entails an injury risk.17 Therefore, an effective intervention

on numberof falls has clinical, public health,and eco-

nomic relevance. The latter reasoning also justifies focusing

on recurrentfallersas an importantoutcome,as in the

current review.

Nursing home residents are often physically frailand

cognitively impaired.Considering the multifactorialnature

of a fall, it is therefore not surprising that single interven-

tions failed to show a beneficialeffect on fall-related out-

comes. The current results suggest that, in the specific care

setting considered,single interventionscould even be

harmful,although these results should be interpreted with

caution,considering the smallnumber of studies,some of

which had poor methodologicalquality.An a priori sub-

group analysis showed that customized,multifactorial

interventions reduced falls.A multidisciplinary team pro-

vided these multifactorialinterventions in allstudies,but

team composition and frequency ofassessmentwere not

reported.Furthermore,the small numberof studiesdid

not allow additionalmoderator analyses to be conducted

to evaluate which components ofthe multifactorialinter-

vention programsor combinationsthereof were most

effective.

The results ofthe regression analysis performed ata

meta level to examine effectiveness of falls prevention pro-

gramsin residentswith dementia werenot anticipated.

There were fewer fallers in intervention groups that had a

greater prevalence of dementia. This outcome contradicts a

previous review,16 but because studies in which the num-

ber of residentswith dementiawas unknown were

excluded,the numberof studiesincluded in the current

review was limited,which might explain the contradictory

Table 4. Effectiveness of Interventions Described in the Included Articles

Study

Falls Fallers, n/N (%) Recurrent Fallers, n/N (%)

Intervention Control

P-

Value Intervention Control

P-

Value Intervention Control

P-

Value

Becker34 1.40/RY 2.56/RY <.001 188/509 (36.9)247/472 (52.3) .04 66/509 (12.9) 115/472

(24.4)

.01

Cox27 NA/3,315 NA/2,322 .17 NA NA

Dyer36 2.17/RY 4.02/RY .27 56/102 (54.9) 51/94 (54.3) .94 26/102 (25.5)25/94 (26.6) .28

Kerse37 NA 162/310 (52.2)146/329 (44.3) .48 NA

Lapane29 3.42/RY 3.78/RY NA NA NA

Law31 2.01/RY 2.31/RY NA 770/1,762

(43.7)

833/1,955

(42.6)

NA NA

McMurdo38 3.02/RY 3.85/RY .16 20/77 (38) 22/56 (58) .09 13/77 (25.0) 9/56 (24) >.99

Neyens39 2.09/RY 2.54/RY .03 NA NA

Patterson30 1.96/RY 1.37/RY .09 NA NA

Rapp35 1.29/RY 2.35/RY NA 143/365 (39.2)189/360 (52.5) NA NA

Ray40 NA NA 91/221 (43.8) 129/261

(54.1)

.03

Schnelle33 0.67/RY 1.09/RY .40 17/92 (18.5) 29/98 (29.6) NA NA

Schoenfelder32 44/7 12/7 NA NA NA

Ward28 Mean 13/

month

Mean 10/

month

NA NA NA

aSame intervention described in both articles.

RY = resident year; NA = not available.

JAGS FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 EFFECT OF FALL PREVENTION IN NURSING HOMES 219

Dementia Status

Regression ofeffectsizesfor the numberof fallersonto

the studies’ prevalence-of-dementia category (see Data Syn-

thesis and Analysis section in Methods)showed thatthe

intervention had protective effects in studies with a greater

proportion of residentswith dementia.Each one-point

increase in dementia prevalence category corresponded to

a RR that was only 0.76 ofits former size (analysis not

consideringdementiaprevalence;95% CI = 0.58–0.99,

P = .04;I² = 0.31,P = .22).31,33,34,38No significantasso-

ciationswith dementia prevalence score were found for

number of falls (RR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.72–1.25,

P = .72; I² = 0, P = .39)28–31,33,34,38,39

or number of recur-

rent fallers (RR = 1.42, 95% CI = 0.49–4.11, P = .51;

I² = 0, P = .45).34,38,40

DISCUSSION

This study is unique,becauseit used a meta-analytical

approach ofthe effectivenessof fall prevention interven-

tions, focusing on a clearly defined setting.In previous

studies,effectivenessremained unclear,partly because of

differencesin definitions of what constitutesa nursing

home.The currentstudy examined notonly effectiveness

of interventions in terms of number of falls and fallers, but

also whetherinterventionsreduced the numberof recur-

rent fallers.Although the overallmeta-analysisfailed to

show an effect on number of falls and fallers,it showed a

significant 21% reduction of number of recurrent fallers in

intervention programs.An a priori subgroup analysisof

intervention type showed thatmultifactorialinterventions

had a significanteffecton number of falls (33%) and

recurrent fallers (21%).

Although the analyses showed no effect on the number

of fallers, it has been argued that using falls as an outcome

has potentialbenefits over using fallers,because each fall

entails an injury risk.17 Therefore, an effective intervention

on numberof falls has clinical, public health,and eco-

nomic relevance. The latter reasoning also justifies focusing

on recurrentfallersas an importantoutcome,as in the

current review.

Nursing home residents are often physically frailand

cognitively impaired.Considering the multifactorialnature

of a fall, it is therefore not surprising that single interven-

tions failed to show a beneficialeffect on fall-related out-

comes. The current results suggest that, in the specific care

setting considered,single interventionscould even be

harmful,although these results should be interpreted with

caution,considering the smallnumber of studies,some of

which had poor methodologicalquality.An a priori sub-

group analysis showed that customized,multifactorial

interventions reduced falls.A multidisciplinary team pro-

vided these multifactorialinterventions in allstudies,but

team composition and frequency ofassessmentwere not

reported.Furthermore,the small numberof studiesdid

not allow additionalmoderator analyses to be conducted

to evaluate which components ofthe multifactorialinter-

vention programsor combinationsthereof were most

effective.

The results ofthe regression analysis performed ata

meta level to examine effectiveness of falls prevention pro-

gramsin residentswith dementia werenot anticipated.

There were fewer fallers in intervention groups that had a

greater prevalence of dementia. This outcome contradicts a

previous review,16 but because studies in which the num-

ber of residentswith dementiawas unknown were

excluded,the numberof studiesincluded in the current

review was limited,which might explain the contradictory

Table 4. Effectiveness of Interventions Described in the Included Articles

Study

Falls Fallers, n/N (%) Recurrent Fallers, n/N (%)

Intervention Control

P-

Value Intervention Control

P-

Value Intervention Control

P-

Value

Becker34 1.40/RY 2.56/RY <.001 188/509 (36.9)247/472 (52.3) .04 66/509 (12.9) 115/472

(24.4)

.01

Cox27 NA/3,315 NA/2,322 .17 NA NA

Dyer36 2.17/RY 4.02/RY .27 56/102 (54.9) 51/94 (54.3) .94 26/102 (25.5)25/94 (26.6) .28

Kerse37 NA 162/310 (52.2)146/329 (44.3) .48 NA

Lapane29 3.42/RY 3.78/RY NA NA NA

Law31 2.01/RY 2.31/RY NA 770/1,762

(43.7)

833/1,955

(42.6)

NA NA

McMurdo38 3.02/RY 3.85/RY .16 20/77 (38) 22/56 (58) .09 13/77 (25.0) 9/56 (24) >.99

Neyens39 2.09/RY 2.54/RY .03 NA NA

Patterson30 1.96/RY 1.37/RY .09 NA NA

Rapp35 1.29/RY 2.35/RY NA 143/365 (39.2)189/360 (52.5) NA NA

Ray40 NA NA 91/221 (43.8) 129/261

(54.1)

.03

Schnelle33 0.67/RY 1.09/RY .40 17/92 (18.5) 29/98 (29.6) NA NA

Schoenfelder32 44/7 12/7 NA NA NA

Ward28 Mean 13/

month

Mean 10/

month

NA NA NA

aSame intervention described in both articles.

RY = resident year; NA = not available.

JAGS FEBRUARY 2015–VOL. 63, NO. 2 EFFECT OF FALL PREVENTION IN NURSING HOMES 219

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

finding.In addition,the lack of objective measurement of

dementia in the included studies prevents firm conclusions

from being drawn.

Some methodological aspects deserve further attention.

First, inherent to this type of research, high loss to follow-

up caused by death or sudden illness and difficulty main-

taining blinding of participantsor treatmentproviders

results in poor overall methodologicalquality of the

included studies.Second,although this review is the first

to suggest that it is possible to reduce the number of recur-

rent fallers in nursing homes,only four studies were eligi-

ble for this analysis.One might wonder whetherthis

significant finding is not the result of multiple testing,but

the subsequent sensitivity analysis results for falls and fal-

lers are concordantwith the effectsize for recurrentfal-

lers, which suggeststhat some unique featuresof those

studies and not random chance might have influenced the

effecton recurrentfallers.More specifically,all included

studiesused a customized,multifactorialapproach con-

ducted by multidisciplinary teams;included an environ-

mentalassessmentand adaptation component;and had a

minimum follow-up of 12 months,as recommended in

ProFaNE.9 This approach wasalso found to be more

effectivein a priori subgroup analyses,although more

research is needed to confirm these findings and to better

understand which components are responsible for this sig-

nificant reduction in recurrent fallers.

Third, despite verifying with the authors of the origi-

nal articlesthat their research setting met,or failed to

meet,the “nursing home” definition,7 this definition is not

as refined and explicit as it could be. For example, it could

be interpreted in different ways.For example,what is the

meaning of “limited care”? This further points toward an

overalllack of a robust conceptualdefinition of what con-

stitutes a nursing home.

Fourth,fall-related outcomes were often inconsistently

reported, and vague definitions were sometimes used. More

specifically, fall definitions were often extended with one or

more specifications,such as “regardless/whateverthe

cause,”34,35 “whether or not an injury resulted,”29 or “the

potentialfor injury exists.”32 The same problem arose for

recurrentfallers.Definitionsvaried from specifying more

than one fall to more than three falls within the last