Closing The Gap: A Strategy for Reducing Child Mortality Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/05

|8

|2101

|259

AI Summary

Closing the Gap is a strategy of the government which performs the function of reducing the disadvantages among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in terms of child mortality, life expectancy, educational achievement, access to early childhood education and employment outcomes. This essay is focused on ‘closing the gap’ target related to child mortality and discusses a strategy for keeping the target on track.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

RUNNING HEAD: Closing The Gap

Closing The Gap

Closing The Gap

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Closing The Gap 1

Closing the Gap is a strategy of the government which performs the function of reducing the

disadvantages among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in terms of child mortality,

life expectancy, educational achievement, access to early childhood education and employment

outcomes. The basic purpose of this strategy is to bring the required improvements in the lives of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians (Boyle & Eades, 2016). Australian government

has made formal commitments for the purpose of achieving health equalities within a period of

25 years. Measurable targets have been set by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG)

for monitoring change and improvements in the wellbeing and health of Torres Strait Islander

and Aboriginal Australians. In the context of child mortality, the target is to halve the gap in

child mortality by the year 2018. Closing the gap targets for child mortality will play an

important role for improving the health by adopting a holistic approach. Remote community

members wish to see a health growth of their children but are continuously facing barriers to

access nutritious and affordable food. They will be offered the needed access to health services

which will improve their health over a period of time (Marmot, 2011). This essay is focused on

‘closing the gap’ target related to child mortality and discusses a strategy for keeping the target

on track.

Child mortality can be defined as the death of children who are under 14 years of age and

includes under 5 mortality, neonatal mortality and mortality of children between the age of 5 and

14. The 2016 Indigenous child mortality rate (0- 4 year old) was within the range such that it can

easily meet its target by the year2018 (Doyle, 2015). In other words, it can be said that the target

is on track. This can be depicted by the figure below:

Closing the Gap is a strategy of the government which performs the function of reducing the

disadvantages among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in terms of child mortality,

life expectancy, educational achievement, access to early childhood education and employment

outcomes. The basic purpose of this strategy is to bring the required improvements in the lives of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians (Boyle & Eades, 2016). Australian government

has made formal commitments for the purpose of achieving health equalities within a period of

25 years. Measurable targets have been set by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG)

for monitoring change and improvements in the wellbeing and health of Torres Strait Islander

and Aboriginal Australians. In the context of child mortality, the target is to halve the gap in

child mortality by the year 2018. Closing the gap targets for child mortality will play an

important role for improving the health by adopting a holistic approach. Remote community

members wish to see a health growth of their children but are continuously facing barriers to

access nutritious and affordable food. They will be offered the needed access to health services

which will improve their health over a period of time (Marmot, 2011). This essay is focused on

‘closing the gap’ target related to child mortality and discusses a strategy for keeping the target

on track.

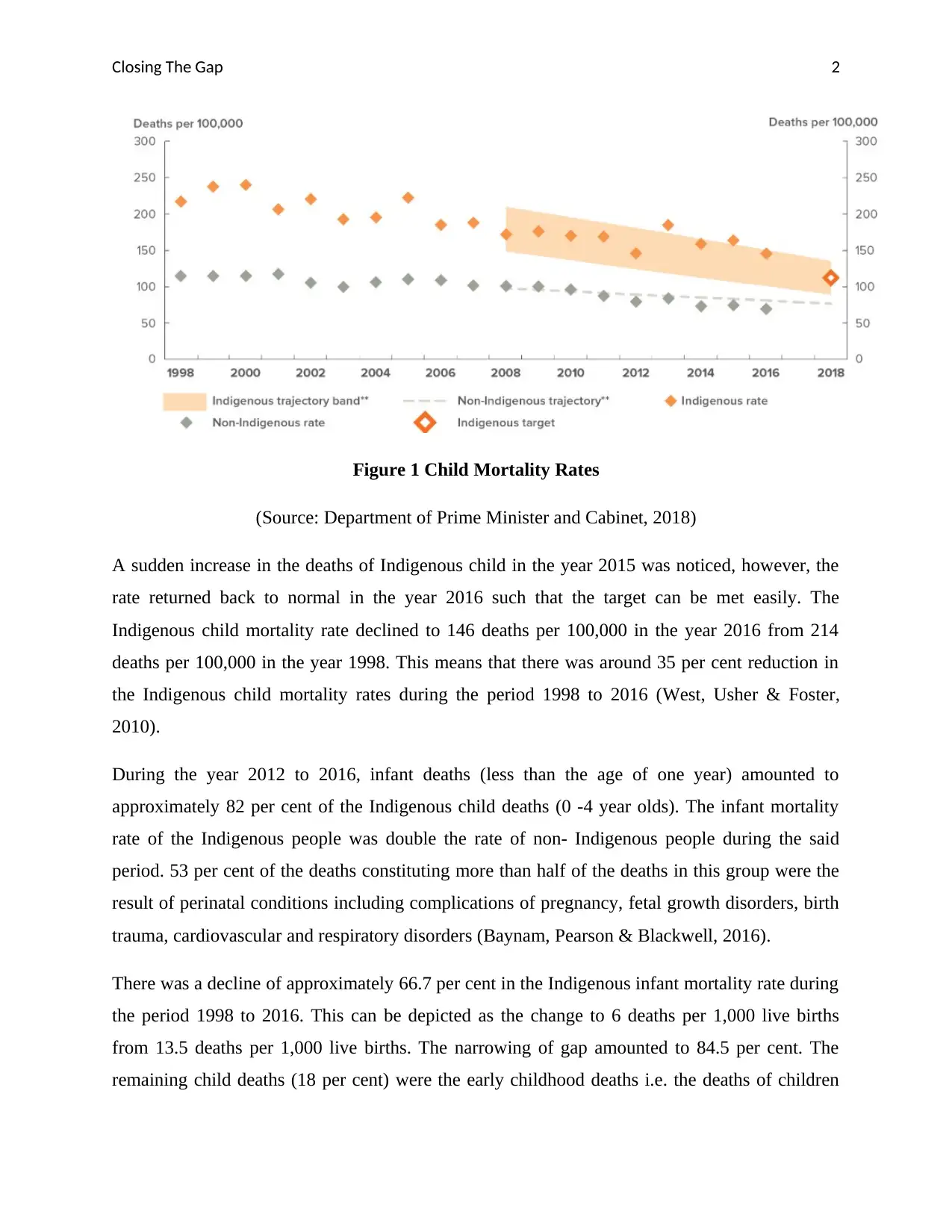

Child mortality can be defined as the death of children who are under 14 years of age and

includes under 5 mortality, neonatal mortality and mortality of children between the age of 5 and

14. The 2016 Indigenous child mortality rate (0- 4 year old) was within the range such that it can

easily meet its target by the year2018 (Doyle, 2015). In other words, it can be said that the target

is on track. This can be depicted by the figure below:

Closing The Gap 2

Figure 1 Child Mortality Rates

(Source: Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2018)

A sudden increase in the deaths of Indigenous child in the year 2015 was noticed, however, the

rate returned back to normal in the year 2016 such that the target can be met easily. The

Indigenous child mortality rate declined to 146 deaths per 100,000 in the year 2016 from 214

deaths per 100,000 in the year 1998. This means that there was around 35 per cent reduction in

the Indigenous child mortality rates during the period 1998 to 2016 (West, Usher & Foster,

2010).

During the year 2012 to 2016, infant deaths (less than the age of one year) amounted to

approximately 82 per cent of the Indigenous child deaths (0 -4 year olds). The infant mortality

rate of the Indigenous people was double the rate of non- Indigenous people during the said

period. 53 per cent of the deaths constituting more than half of the deaths in this group were the

result of perinatal conditions including complications of pregnancy, fetal growth disorders, birth

trauma, cardiovascular and respiratory disorders (Baynam, Pearson & Blackwell, 2016).

There was a decline of approximately 66.7 per cent in the Indigenous infant mortality rate during

the period 1998 to 2016. This can be depicted as the change to 6 deaths per 1,000 live births

from 13.5 deaths per 1,000 live births. The narrowing of gap amounted to 84.5 per cent. The

remaining child deaths (18 per cent) were the early childhood deaths i.e. the deaths of children

Figure 1 Child Mortality Rates

(Source: Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2018)

A sudden increase in the deaths of Indigenous child in the year 2015 was noticed, however, the

rate returned back to normal in the year 2016 such that the target can be met easily. The

Indigenous child mortality rate declined to 146 deaths per 100,000 in the year 2016 from 214

deaths per 100,000 in the year 1998. This means that there was around 35 per cent reduction in

the Indigenous child mortality rates during the period 1998 to 2016 (West, Usher & Foster,

2010).

During the year 2012 to 2016, infant deaths (less than the age of one year) amounted to

approximately 82 per cent of the Indigenous child deaths (0 -4 year olds). The infant mortality

rate of the Indigenous people was double the rate of non- Indigenous people during the said

period. 53 per cent of the deaths constituting more than half of the deaths in this group were the

result of perinatal conditions including complications of pregnancy, fetal growth disorders, birth

trauma, cardiovascular and respiratory disorders (Baynam, Pearson & Blackwell, 2016).

There was a decline of approximately 66.7 per cent in the Indigenous infant mortality rate during

the period 1998 to 2016. This can be depicted as the change to 6 deaths per 1,000 live births

from 13.5 deaths per 1,000 live births. The narrowing of gap amounted to 84.5 per cent. The

remaining child deaths (18 per cent) were the early childhood deaths i.e. the deaths of children

Closing The Gap 3

between the ages of 1- 4 years. The early childhood mortality rate was noticed to be highly

fluctuated during 1998 to 2016 (Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2018).

Perinatal conditions are regarded as the single largest cause of Indigenous child mortality and

accounted for 43.5 per cent of Indigenous child deaths during the year 2012 to 2016. This cause

also resulted in 42.7 per cent of the child mortality gap between non- Indigenous and Indigenous.

Child mortality is also the result of various other causes such as ill- defined and sudden

conditions like Sudden Infant Death Syndrome that result in 17.9 per cent of the deaths and

injury and poisoning (12 per cent) and congenital malformation (12.2 per cent of 0- 4 year old

deaths) (Martin, 2017).

The target is on track because the government is making the use of certain strategies for this

purpose. The Australian Government has introduced a number of programs in order to prioritize

investment in maternal and child health. For example, $ 94 million funding is being invested for

the Better Start to Life approach over 3 years starting from July 2015. This will lead to the

expansion of two existing programs i.e. New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services

Programme and the Australian Nurse Family Partnership Programme (Pritchard & Wallace,

2015).

A number of early childhood initiatives are funded by the Indigenous Advancement Strategy

(IAS) for the purpose of supporting parents, young mothers and families including parenting

classes, facilitated playgroups, outreach and home visiting programs. Skills and knowledge of

the Indigenous parents are enhanced with the help of these activities along with promoting

healthy development of children. New Directions: Mothers and Babies Service (NDMBS)

program has facilitated its expansion to 124 sites from 85 sites. Moreover, further expansion of

the program has been planned for additional 12 sites which will make the total to 136 sites.

Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal children along with their mothers are continuously being

supported by NDMBS. The program is providing postnatal and antenatal care access to children

and their mothers along with assistance and practical advice with breast feeding, standard

information regarding body care, parenting and nutrition, infections and immunization,

monitoring of developmental milestones, health checks and treatments for children before

attending school (Fraser, Sidebotham, Frederick, Covington & Mitchell, 2014).

between the ages of 1- 4 years. The early childhood mortality rate was noticed to be highly

fluctuated during 1998 to 2016 (Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2018).

Perinatal conditions are regarded as the single largest cause of Indigenous child mortality and

accounted for 43.5 per cent of Indigenous child deaths during the year 2012 to 2016. This cause

also resulted in 42.7 per cent of the child mortality gap between non- Indigenous and Indigenous.

Child mortality is also the result of various other causes such as ill- defined and sudden

conditions like Sudden Infant Death Syndrome that result in 17.9 per cent of the deaths and

injury and poisoning (12 per cent) and congenital malformation (12.2 per cent of 0- 4 year old

deaths) (Martin, 2017).

The target is on track because the government is making the use of certain strategies for this

purpose. The Australian Government has introduced a number of programs in order to prioritize

investment in maternal and child health. For example, $ 94 million funding is being invested for

the Better Start to Life approach over 3 years starting from July 2015. This will lead to the

expansion of two existing programs i.e. New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services

Programme and the Australian Nurse Family Partnership Programme (Pritchard & Wallace,

2015).

A number of early childhood initiatives are funded by the Indigenous Advancement Strategy

(IAS) for the purpose of supporting parents, young mothers and families including parenting

classes, facilitated playgroups, outreach and home visiting programs. Skills and knowledge of

the Indigenous parents are enhanced with the help of these activities along with promoting

healthy development of children. New Directions: Mothers and Babies Service (NDMBS)

program has facilitated its expansion to 124 sites from 85 sites. Moreover, further expansion of

the program has been planned for additional 12 sites which will make the total to 136 sites.

Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal children along with their mothers are continuously being

supported by NDMBS. The program is providing postnatal and antenatal care access to children

and their mothers along with assistance and practical advice with breast feeding, standard

information regarding body care, parenting and nutrition, infections and immunization,

monitoring of developmental milestones, health checks and treatments for children before

attending school (Fraser, Sidebotham, Frederick, Covington & Mitchell, 2014).

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Closing The Gap 4

It is suggested that Australian Government should undertake the integrated management of

childhood illness (IMCI) for under 5 year old children. This strategy will act as the integrated

approach to health of children and will focus on their well- being. It will further aim at reducing

illness, death and disability along with promoting improved development and growth of children

under the age of 5 years. Both curative and preventive elements will be included in this strategy

the implementation of which will be facilitated by communities, families and health facilities.

The strategy will be based on three main components namely bringing improvement in the

overall health system, improving health practices of the community and family and improving

skills related to case management of the health care staff. This strategy is also promoted by the

World Health Organization for the reduction of child mortality. The progress of the target will be

on track as the strategy will help in promoting the accurate and timely identification of childhood

illness and ensuring the treatments for all the major illnesses, increases the speed of referrals of

severely ill children and supports the counselling of caretakers. Appropriate care seeking

behaviors are promoted in the home setting along with preventive care, improved nutrition and

accurate implementation of prescribed care (World Health Organization, 2015).

Coordination will be required among the current health programmes and services for the

effective implementation of IMCI strategy for improving the health and reducing child mortality.

It will further require working closely with ministries of health and local government for the

purpose of planning and adapting the principles of approach to the given circumstances.

Furthermore, support mechanisms will need to be developed within communities such that

diseases can be prevented and families can be supported while caring for their sick children and

getting them to hospitals and clinics when required. For this, care should be upgraded in the local

clinics by way of provided training to the health workers such that they can examine and treat

children through new methods. Upgraded care will also be made possible with the help of this

strategy by ensuring the availability of simple equipment and appropriate low- cost medicines

(Morawska, Calam & Fraser, 2015).

Therefore, it can be concluded that currently, closing the gap target to halve the child mortality

gap by the year 2018 is on track. The period between the year 1998 and 2016 led to a great

decline in the Indigenous child mortality rates by 35 per cent. Furthermore, narrowing of the gap

has been noticed (by 32 per cent). However, slow progress is being observed since the 2008

It is suggested that Australian Government should undertake the integrated management of

childhood illness (IMCI) for under 5 year old children. This strategy will act as the integrated

approach to health of children and will focus on their well- being. It will further aim at reducing

illness, death and disability along with promoting improved development and growth of children

under the age of 5 years. Both curative and preventive elements will be included in this strategy

the implementation of which will be facilitated by communities, families and health facilities.

The strategy will be based on three main components namely bringing improvement in the

overall health system, improving health practices of the community and family and improving

skills related to case management of the health care staff. This strategy is also promoted by the

World Health Organization for the reduction of child mortality. The progress of the target will be

on track as the strategy will help in promoting the accurate and timely identification of childhood

illness and ensuring the treatments for all the major illnesses, increases the speed of referrals of

severely ill children and supports the counselling of caretakers. Appropriate care seeking

behaviors are promoted in the home setting along with preventive care, improved nutrition and

accurate implementation of prescribed care (World Health Organization, 2015).

Coordination will be required among the current health programmes and services for the

effective implementation of IMCI strategy for improving the health and reducing child mortality.

It will further require working closely with ministries of health and local government for the

purpose of planning and adapting the principles of approach to the given circumstances.

Furthermore, support mechanisms will need to be developed within communities such that

diseases can be prevented and families can be supported while caring for their sick children and

getting them to hospitals and clinics when required. For this, care should be upgraded in the local

clinics by way of provided training to the health workers such that they can examine and treat

children through new methods. Upgraded care will also be made possible with the help of this

strategy by ensuring the availability of simple equipment and appropriate low- cost medicines

(Morawska, Calam & Fraser, 2015).

Therefore, it can be concluded that currently, closing the gap target to halve the child mortality

gap by the year 2018 is on track. The period between the year 1998 and 2016 led to a great

decline in the Indigenous child mortality rates by 35 per cent. Furthermore, narrowing of the gap

has been noticed (by 32 per cent). However, slow progress is being observed since the 2008

Closing The Gap 5

target baseline. It is further expected that the past improvements in the key drivers of maternal

and child health will lead to future gains as well. The strategies currently used by the Australian

Government prioritize investment in maternal and child health. It is suggested that Australian

Government should undertake the integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) for under

5 year old children. This strategy will act as the integrated approach to health of children and will

focus on their well- being.

target baseline. It is further expected that the past improvements in the key drivers of maternal

and child health will lead to future gains as well. The strategies currently used by the Australian

Government prioritize investment in maternal and child health. It is suggested that Australian

Government should undertake the integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) for under

5 year old children. This strategy will act as the integrated approach to health of children and will

focus on their well- being.

Closing The Gap 6

References

Baynam, G. S., Pearson, G., & Blackwell, J. (2016). Translating Aboriginal genomics—four

letters Closing the Gap. The Medical journal of Australia, 205(8), 379.

Boyle, J., & Eades, S. (2016). Closing the gap in Aboriginal women's reproductive health: some

progress, but still a long way to go. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics

and Gynaecology, 56(3), 223-224.

Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. (2018). INFANCY AND EARLY CHILDHOOD.

Retrieved September 16, 2018 from https://closingthegap.pmc.gov.au/infancy-and-early-

childhood

Doyle, K. E. (2015). Australian Aboriginal peoples and evidence-based policies: closing the gap

in social interventions. Journal of evidence-informed social work, 12(2), 166-174.

Fraser, J., Sidebotham, P., Frederick, J., Covington, T., & Mitchell, E. A. (2014). Learning from

child death review in the USA, England, Australia, and New Zealand. The

Lancet, 384(9946), 894-903.

Marmot, M. (2011). Social determinants and the health of Indigenous Australians. Med J

Aust, 194(10), 512-3.

Martin, W. (2017). Passing the buck-Has the diffusion of responsibility for Aboriginal people in

our federation impeded closing the gap?. Brief, 44(9), 28.

Morawska, A., Calam, R., & Fraser, J. (2015). Parenting interventions for childhood chronic

illness: A review and recommendations for intervention design and delivery. Journal of

Child Health Care, 19(1), 5-17.

Pritchard, C., & Wallace, M. S. (2015). Comparing UK and other western countries' health

expenditure, relative poverty and child mortality: are British children doubly

disadvantaged?. Children & Society, 29(5), 462-472.

References

Baynam, G. S., Pearson, G., & Blackwell, J. (2016). Translating Aboriginal genomics—four

letters Closing the Gap. The Medical journal of Australia, 205(8), 379.

Boyle, J., & Eades, S. (2016). Closing the gap in Aboriginal women's reproductive health: some

progress, but still a long way to go. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics

and Gynaecology, 56(3), 223-224.

Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. (2018). INFANCY AND EARLY CHILDHOOD.

Retrieved September 16, 2018 from https://closingthegap.pmc.gov.au/infancy-and-early-

childhood

Doyle, K. E. (2015). Australian Aboriginal peoples and evidence-based policies: closing the gap

in social interventions. Journal of evidence-informed social work, 12(2), 166-174.

Fraser, J., Sidebotham, P., Frederick, J., Covington, T., & Mitchell, E. A. (2014). Learning from

child death review in the USA, England, Australia, and New Zealand. The

Lancet, 384(9946), 894-903.

Marmot, M. (2011). Social determinants and the health of Indigenous Australians. Med J

Aust, 194(10), 512-3.

Martin, W. (2017). Passing the buck-Has the diffusion of responsibility for Aboriginal people in

our federation impeded closing the gap?. Brief, 44(9), 28.

Morawska, A., Calam, R., & Fraser, J. (2015). Parenting interventions for childhood chronic

illness: A review and recommendations for intervention design and delivery. Journal of

Child Health Care, 19(1), 5-17.

Pritchard, C., & Wallace, M. S. (2015). Comparing UK and other western countries' health

expenditure, relative poverty and child mortality: are British children doubly

disadvantaged?. Children & Society, 29(5), 462-472.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Closing The Gap 7

West, R., Usher, K., & Foster, K. (2010). Increased numbers of Australian Indigenous nurses

would make a significant contribution to ‘closing the gap’in Indigenous health: What is

getting in the way?. Contemporary Nurse, 36(1-2), 121-130.

World Health Organization. (2015). MDG 4: reduce child mortality. Retrieved September 16,

2018 from http://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/child_mortality/

en/

West, R., Usher, K., & Foster, K. (2010). Increased numbers of Australian Indigenous nurses

would make a significant contribution to ‘closing the gap’in Indigenous health: What is

getting in the way?. Contemporary Nurse, 36(1-2), 121-130.

World Health Organization. (2015). MDG 4: reduce child mortality. Retrieved September 16,

2018 from http://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/child_mortality/

en/

1 out of 8

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.