Copyright Protection under the Copyright Act 1968 (Act)

24 Pages12602 Words70 Views

Added on 2021-10-01

About This Document

The chapter discusses the various definitions of corporate governance, reviews the main objective of the corporation and explains how corporate governance problems change with ownership and control concentration. LEARNING OUTCOMES After reading this chapter, you should be able to: 1 Contrast the different definitions of corporate governance 2 Critically review the principal-agent model 3 Discuss the agency problems of equity and debt 4 Explain the corporate governance problem that prevails in countries where corporate ownership and control are concentrated 5 Distinguish between ownership and control - Introduction While

Copyright Protection under the Copyright Act 1968 (Act)

Added on 2021-10-01

ShareRelated Documents

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA

WARNING

This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of

Murdoch University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1968 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further

reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright

protection under the Act.

Do not remove this notice

Course of Study:

(BUS284) Comparative Corporate Governance and International Operations

Title of work:

International corporate governance (2012)

Section:

Chapter 1: Defining corporate governance and key theoretical models pp. 3--24

Author/editor of work:

Goergen, Marc

Author of section:

Marc Goergen

Name of Publisher:

Pearson

WARNING

This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of

Murdoch University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1968 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further

reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright

protection under the Act.

Do not remove this notice

Course of Study:

(BUS284) Comparative Corporate Governance and International Operations

Title of work:

International corporate governance (2012)

Section:

Chapter 1: Defining corporate governance and key theoretical models pp. 3--24

Author/editor of work:

Goergen, Marc

Author of section:

Marc Goergen

Name of Publisher:

Pearson

PART I

Introduction to Corporate Governance

Introduction to Corporate Governance

Defining corporate governance and key

theoretical models

- Chapter aims

This chapter aims to introduce you to the subject area of corporate governance. The

chapter discusses the various definitions of corporate governance, reviews the main

objective of the corporation and explains how corporate governance problems

change with ownership and control concentration. The chapter also introduces

the main theories underpinning corporate governance. While the book focuses on

stock-exchange listed corporations, this chapter also discusses alternative forms of

organisations such as mutual organisations and partnerships.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Contrast the different definitions of corporate governance

2 Critically review the principal-agent model

3 Discuss the agency problems of equity and debt

4 Explain the corporate governance problem that prevails in countries

where corporate ownership and control are concentrated

5 Distinguish between ownership and control

- Introduction

While this chapter will briefly review alternative forms of organisation and own

ership, the focus of this book is on stock-exchange listed firms. These firms are

typically in the form of stock corporations, i.e. they have equity stocks or shares

outstanding which trade on a recognised stock exchange. Stocks or shares are cer

tificates of ownership and they also frequently have control rights, i.e. voting

rights which enable their holders, the shareholders, to vote at the annual gen

eral shareholders' meeting (AGM). One of the important rights that voting shares

confer to their holders is the right to appoint the members of the board of direc

tors. The board of directors is the ultimate governing body within the corporation.

Its role, and in particular the role of the non-executive directors on the board, is

to look after the interests of all the shareholders as well as sometimes those of other

stakeholders such as the corporation's employees or banks. More precisely, the

non-executives' role is to monitor the firm's top management, including the execu

tive directors which are the other type of directors sitting on the firm's board.1

theoretical models

- Chapter aims

This chapter aims to introduce you to the subject area of corporate governance. The

chapter discusses the various definitions of corporate governance, reviews the main

objective of the corporation and explains how corporate governance problems

change with ownership and control concentration. The chapter also introduces

the main theories underpinning corporate governance. While the book focuses on

stock-exchange listed corporations, this chapter also discusses alternative forms of

organisations such as mutual organisations and partnerships.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Contrast the different definitions of corporate governance

2 Critically review the principal-agent model

3 Discuss the agency problems of equity and debt

4 Explain the corporate governance problem that prevails in countries

where corporate ownership and control are concentrated

5 Distinguish between ownership and control

- Introduction

While this chapter will briefly review alternative forms of organisation and own

ership, the focus of this book is on stock-exchange listed firms. These firms are

typically in the form of stock corporations, i.e. they have equity stocks or shares

outstanding which trade on a recognised stock exchange. Stocks or shares are cer

tificates of ownership and they also frequently have control rights, i.e. voting

rights which enable their holders, the shareholders, to vote at the annual gen

eral shareholders' meeting (AGM). One of the important rights that voting shares

confer to their holders is the right to appoint the members of the board of direc

tors. The board of directors is the ultimate governing body within the corporation.

Its role, and in particular the role of the non-executive directors on the board, is

to look after the interests of all the shareholders as well as sometimes those of other

stakeholders such as the corporation's employees or banks. More precisely, the

non-executives' role is to monitor the firm's top management, including the execu

tive directors which are the other type of directors sitting on the firm's board.1

4 C H APTER 1 • DEFINING CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND KEY TH EORETICAL MODELS

While in the US non-executives are referred to as (independent or outside) directors

and executives are referred to as officers, this book adopts the internationally used

terminology of non-executive and executive directors.

- Defining corporate governance

Most definitions of corporate governance are based on implicit, if not explicit,

assumptions about what should be the main objective of the corporation. However,

there is no universal agreement as to what the main objective of a corporation

should be and this objective is likely to depend on a country's culture and elec

toral system and its government's political orientation as well as the country's legal

system. Chapter 4 of Part II will shed more light on how these cultural, political

and institutional factors may explain differences in corporate governance and con

trol across countries.

Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny define corporate governance as:

'the ways in which suppliers of fi.nance to corporations assure themselves of getting a

return on their investment. '2

Basing themselves on Oliver Williamson's work,3 Shleifer and Vishny's defini

tion clearly assumes that the main objective of the corporation is to maximise the

returns to the shareholders (as well as the debtholders). They justify their focus

by the argument that the investments in the firm by the providers of finance are

typically sunk funds, i.e. funds that the latter are likely to lose if the corporation

runs into trouble. On the contrary,-the corporation's other stakeholders, such as

its employees, suppliers and customers, can easily walk away from the corpora

tion without losing their investments. For example, an employee should be able to

find a job in another firm which values her human capital. While the providers of

finance lose the capital they have invested in the corporation, the employee does

not lose her human capital if the firm fails. Hence, the providers of finance, and

in particular the shareholders, are the residual risk bearers or the residual claim

a nts to the firm's assets. In other words, if the firm gets into financial distress, the

claims of all the stakeholders other than the shareholders will be met first before

the claims of the latter can be met. Typically when the firm is in financial distress,

the firm's assets are insufficient to meet all of the claims it is facing and the share

holders will lose their initial investment. In contrast, the other claimants will walk

away with all or at least some of their capital.

In contrast to Shleifer and Vishny, Sarah Worthington argues that there is noth

ing in the legal status of a shareholder that justifies the focus on shareholder value

maximisation.4 Paddy Ireland goes one step further, arguing that corporate assets

should no longer be considered to be the private property of the shareholders but

rather as common property given that they are 'the product of the collective labour

of many generations' (p. 56).5 Marc Goergen and Luc Renneboog suggest a defini

tion which allows for differences across firms in terms of the actors or stakeholders

whose interests the corporation focuses on. According to their definition,

'[a] corporate governance system is the combination of mechanisms which ensure that

the management (the agent) runs the fi.rm for the benefi.t of one or several stakehold

ers (principals). Such stakeholders may cover shareholders, creditors, suppliers, clients,

employees and other parties with whom the fi.rm conducts its business.'6

While in the US non-executives are referred to as (independent or outside) directors

and executives are referred to as officers, this book adopts the internationally used

terminology of non-executive and executive directors.

- Defining corporate governance

Most definitions of corporate governance are based on implicit, if not explicit,

assumptions about what should be the main objective of the corporation. However,

there is no universal agreement as to what the main objective of a corporation

should be and this objective is likely to depend on a country's culture and elec

toral system and its government's political orientation as well as the country's legal

system. Chapter 4 of Part II will shed more light on how these cultural, political

and institutional factors may explain differences in corporate governance and con

trol across countries.

Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny define corporate governance as:

'the ways in which suppliers of fi.nance to corporations assure themselves of getting a

return on their investment. '2

Basing themselves on Oliver Williamson's work,3 Shleifer and Vishny's defini

tion clearly assumes that the main objective of the corporation is to maximise the

returns to the shareholders (as well as the debtholders). They justify their focus

by the argument that the investments in the firm by the providers of finance are

typically sunk funds, i.e. funds that the latter are likely to lose if the corporation

runs into trouble. On the contrary,-the corporation's other stakeholders, such as

its employees, suppliers and customers, can easily walk away from the corpora

tion without losing their investments. For example, an employee should be able to

find a job in another firm which values her human capital. While the providers of

finance lose the capital they have invested in the corporation, the employee does

not lose her human capital if the firm fails. Hence, the providers of finance, and

in particular the shareholders, are the residual risk bearers or the residual claim

a nts to the firm's assets. In other words, if the firm gets into financial distress, the

claims of all the stakeholders other than the shareholders will be met first before

the claims of the latter can be met. Typically when the firm is in financial distress,

the firm's assets are insufficient to meet all of the claims it is facing and the share

holders will lose their initial investment. In contrast, the other claimants will walk

away with all or at least some of their capital.

In contrast to Shleifer and Vishny, Sarah Worthington argues that there is noth

ing in the legal status of a shareholder that justifies the focus on shareholder value

maximisation.4 Paddy Ireland goes one step further, arguing that corporate assets

should no longer be considered to be the private property of the shareholders but

rather as common property given that they are 'the product of the collective labour

of many generations' (p. 56).5 Marc Goergen and Luc Renneboog suggest a defini

tion which allows for differences across firms in terms of the actors or stakeholders

whose interests the corporation focuses on. According to their definition,

'[a] corporate governance system is the combination of mechanisms which ensure that

the management (the agent) runs the fi.rm for the benefi.t of one or several stakehold

ers (principals). Such stakeholders may cover shareholders, creditors, suppliers, clients,

employees and other parties with whom the fi.rm conducts its business.'6

-

1.2 DEFINING CORPORORATE GOVERNANCE 5

While Shleifer and Vishny's definition largely reflects the focus of the typi

cal American or British stock-exchange listed corporation, managers of most

Continental European firms also tend to take into account the interests of the

corporation's other stakeholders when running the firm. Although this statement

dates back more than 40 years and may now appear somewhat stereotypical, it nev

ertheless is a good illustration of what is frequently still managers' attitude outside

the Anglo-American world. The chief executive officer (CEO) of the German car

maker Volkswagen AG stated the following.

'Why should I care about the shareholders, who I see once a year at the general meet

ing. It is much more important that I care about the employees; I see them every day.17

Further, in Germany corporate law explicitly includes other stakeholder interests in

the firm's objective function. Indeed, the German Co-determination Law of 1976

requires firms with more than 2,000 workers to have 50% of employee representa

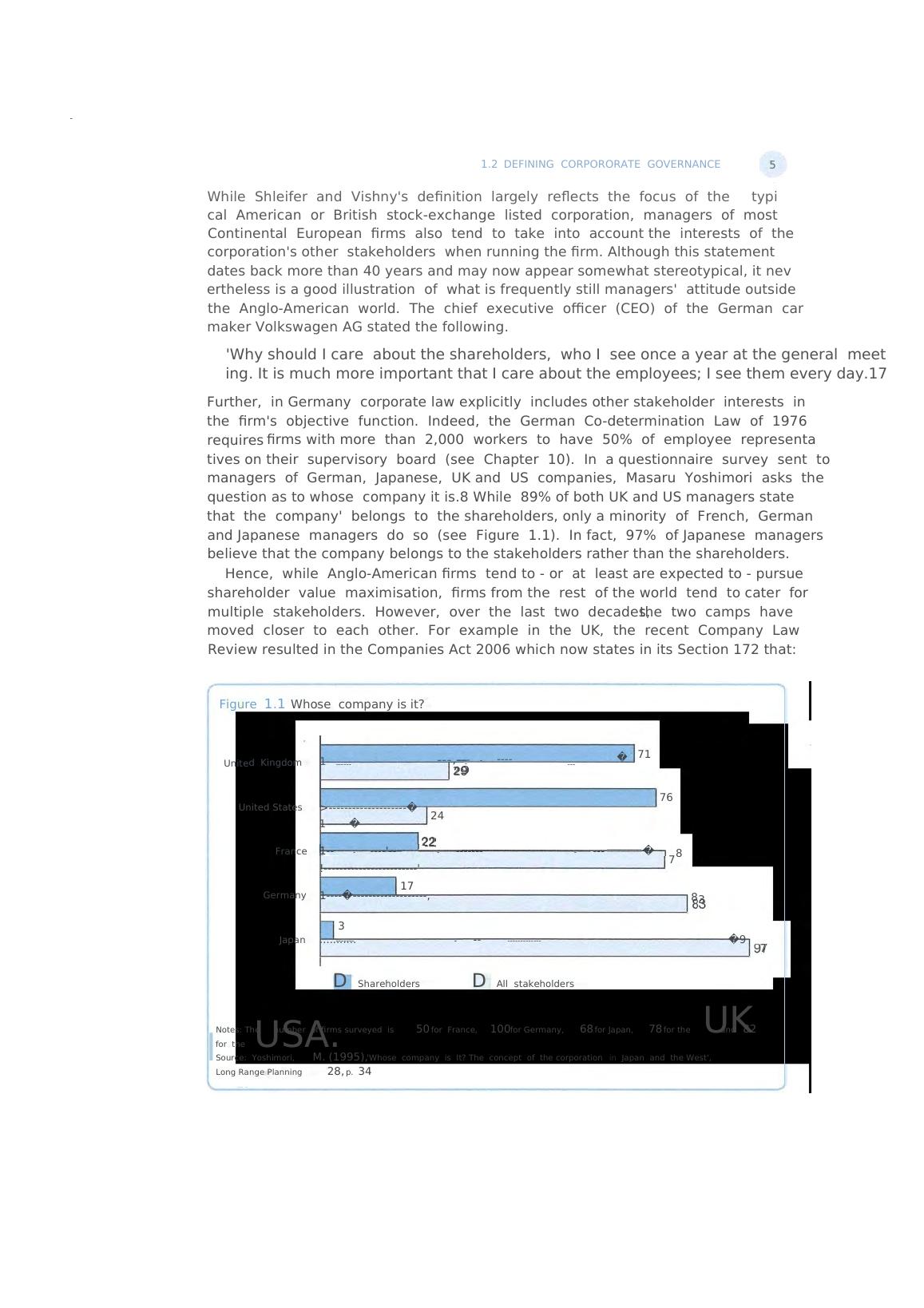

tives on their supervisory board (see Chapter 10). In a questionnaire survey sent to

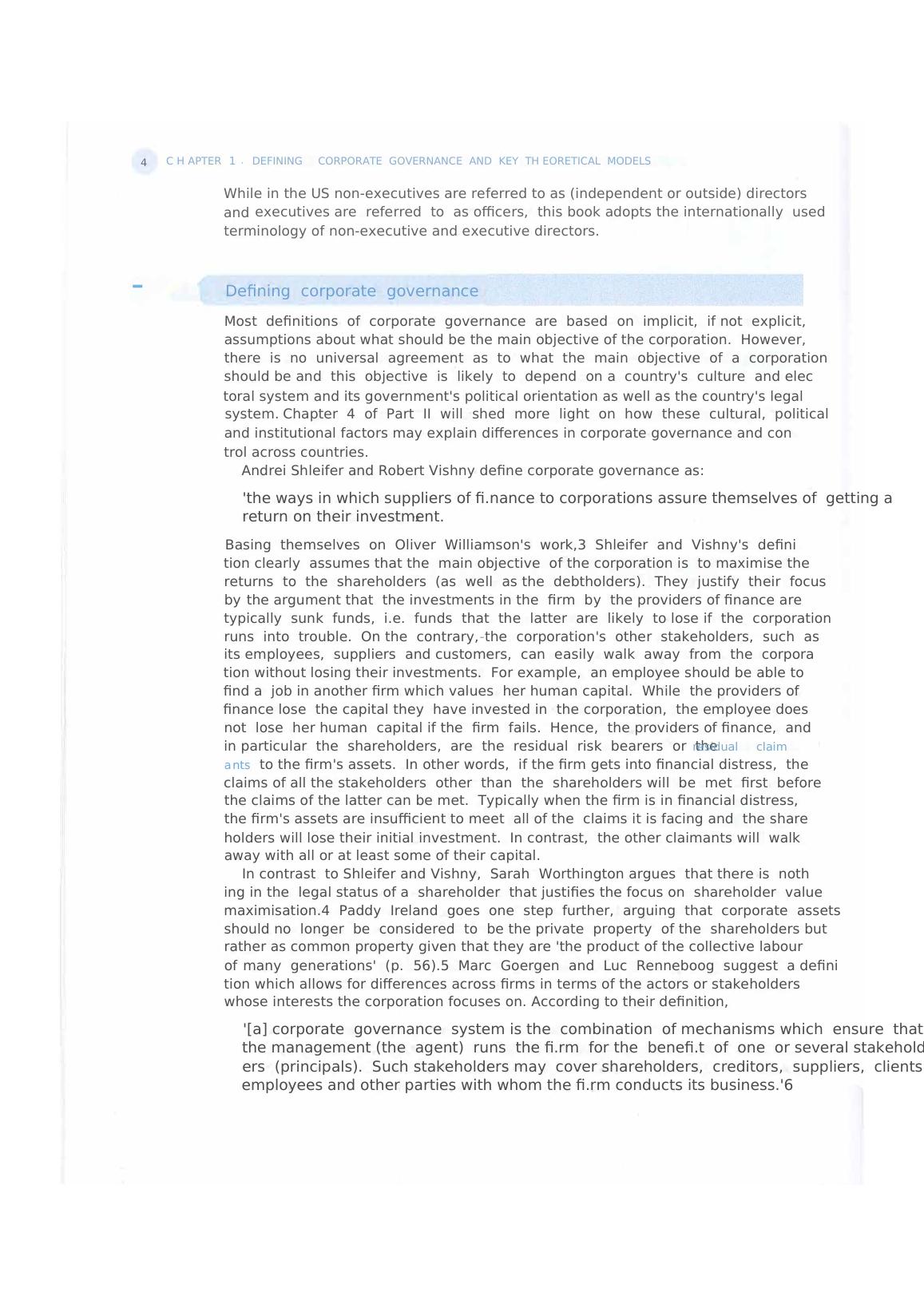

managers of German, Japanese, UK and US companies, Masaru Yoshimori asks the

question as to whose company it is.8 While 89% of both UK and US managers state

that the company' belongs to the shareholders, only a minority of French, German

and Japanese managers do so (see Figure 1.1). In fact, 97% of Japanese managers

believe that the company belongs to the stakeholders rather than the shareholders.

Hence, while Anglo-American firms tend to - or at least are expected to - pursue

shareholder value maximisation, firms from the rest of the world tend to cater for

multiple stakeholders. However, over the last two decades, the two camps have

moved closer to each other. For example in the UK, the recent Company Law

Review resulted in the Companies Act 2006 which now states in its Section 172 that:

Figure 1.1 Whose company is it?

71 United Kingdom 1- ------ ---,--

2

-

9- - ---- --- �

76 United States >--------------------� 24 1------�

22 France 1-- - ----'-- - ------- - --- � 78

!------------------------'

17 Germany 1----�-------------------, 83

3

Japan ........... ------- - -- ------------- �9 7

D Shareholders D All stakeholders

Notes: The number of firms surveyed is 50 for France, 100 for Germany, 68 for Japan, 78 for the UK and 82

for the USA. l Source: Yoshimori, M. (1995), 'Whose company is It? The concept of the corporation in Japan and the West',

Long Range Planning 28, p. 34

-- -

1.2 DEFINING CORPORORATE GOVERNANCE 5

While Shleifer and Vishny's definition largely reflects the focus of the typi

cal American or British stock-exchange listed corporation, managers of most

Continental European firms also tend to take into account the interests of the

corporation's other stakeholders when running the firm. Although this statement

dates back more than 40 years and may now appear somewhat stereotypical, it nev

ertheless is a good illustration of what is frequently still managers' attitude outside

the Anglo-American world. The chief executive officer (CEO) of the German car

maker Volkswagen AG stated the following.

'Why should I care about the shareholders, who I see once a year at the general meet

ing. It is much more important that I care about the employees; I see them every day.17

Further, in Germany corporate law explicitly includes other stakeholder interests in

the firm's objective function. Indeed, the German Co-determination Law of 1976

requires firms with more than 2,000 workers to have 50% of employee representa

tives on their supervisory board (see Chapter 10). In a questionnaire survey sent to

managers of German, Japanese, UK and US companies, Masaru Yoshimori asks the

question as to whose company it is.8 While 89% of both UK and US managers state

that the company' belongs to the shareholders, only a minority of French, German

and Japanese managers do so (see Figure 1.1). In fact, 97% of Japanese managers

believe that the company belongs to the stakeholders rather than the shareholders.

Hence, while Anglo-American firms tend to - or at least are expected to - pursue

shareholder value maximisation, firms from the rest of the world tend to cater for

multiple stakeholders. However, over the last two decades, the two camps have

moved closer to each other. For example in the UK, the recent Company Law

Review resulted in the Companies Act 2006 which now states in its Section 172 that:

Figure 1.1 Whose company is it?

71 United Kingdom 1- ------ ---,--

2

-

9- - ---- --- �

76 United States >--------------------� 24 1------�

22 France 1-- - ----'-- - ------- - --- � 78

!------------------------'

17 Germany 1----�-------------------, 83

3

Japan ........... ------- - -- ------------- �9 7

D Shareholders D All stakeholders

Notes: The number of firms surveyed is 50 for France, 100 for Germany, 68 for Japan, 78 for the UK and 82

for the USA. l Source: Yoshimori, M. (1995), 'Whose company is It? The concept of the corporation in Japan and the West',

Long Range Planning 28, p. 34

-- -

6 C H APTER 1 • DEFINING CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND KEY TH EORETICAL MODELS

'Directors should also recognise, as the circumstances require, the company's need to

foster relationships with its employees, customers and suppliers, its need to maintain its

business reputation, and its need to consider the company's impact on the community

and the working environment.'

Nevertheless, company directors must act bona "fide in accordance to what would

most likely promote the success of the company for the benefit of the collective

body of shareholders. In other words, while directors are expected to take into

account the interests of other stakeholders, they should only do so if this is in the

long-term interest of the company, and ultimately its shareholders, i.e. its owners.

Hence, the principle of shareholder primacy is still pretty much intact in the

UK and also the USA. At the same time, Continental Europe has moved closer to

the shareholder-oriented system of corporate governance. In particular, European

Union (EU) law has moved the law of its 27 member states closer to UK law. An

example is the 2004 EU Takeovers Directive which was largely modelled on the

UK City Code on Mergers and Takeovers (see Chapter 7 for details). In turn, recent

pressure on (large) corporations to behave socially responsibly has moved stake

holder considerations to the forefront.

A more neutral and less politically charged definition of corporate governance is

that the latter deals with conflicts of interests between

• the providers of finance and the managers;

• the shareholders and the stakeholders;

• different types of shareholders (mainly the large shareholder and the minority

shareholders);

and the prevention or mitigation of these conflicts of interests. This is the defini

tion which is adopted in this book. Another important advantage of this definition

is that it can be applied to a variety of corporate governance systems. More pre

cisely, this definition does not assume that problems of corporate governance are

limited to the failure of the management to look after the interests of the firm's

shareholders, but it also covers other possible corporate governance problems ·

which are more likely to emerge in countries where corporations are characterised

by concentrated ownership and control. These corporate governance problems nor

mally consist of conflicts of interests between the firm's large shareholder and its

minority shareholders.

One of the first codes of best practice on corporate governance, if not even the

very first one, was the Cadbury Report which was issued in 1992 in the United

Kingdom.9 The Cadbury Report defines corporate governance as 'the system by

which companies are directed and controlled'. However, in the following sentences

the Report then goes on to mention what it considers to be the crucial role of

boards of directors in corporate governance:

'Boards of directors are responsible for the governance of their companies. The share

holders' role in governance is to appoint the directors and the auditors and to satisty

themselves that an appropriate governance structure is in place. The responsibilities of

the board include setting the company's strategic aims, providing the leadership to put

them into effect, supervising the management of the business and reporting to share

holders on their stewardship. The board's actions are subject to laws, regulations and

the shareholders in general meeting.'

'Directors should also recognise, as the circumstances require, the company's need to

foster relationships with its employees, customers and suppliers, its need to maintain its

business reputation, and its need to consider the company's impact on the community

and the working environment.'

Nevertheless, company directors must act bona "fide in accordance to what would

most likely promote the success of the company for the benefit of the collective

body of shareholders. In other words, while directors are expected to take into

account the interests of other stakeholders, they should only do so if this is in the

long-term interest of the company, and ultimately its shareholders, i.e. its owners.

Hence, the principle of shareholder primacy is still pretty much intact in the

UK and also the USA. At the same time, Continental Europe has moved closer to

the shareholder-oriented system of corporate governance. In particular, European

Union (EU) law has moved the law of its 27 member states closer to UK law. An

example is the 2004 EU Takeovers Directive which was largely modelled on the

UK City Code on Mergers and Takeovers (see Chapter 7 for details). In turn, recent

pressure on (large) corporations to behave socially responsibly has moved stake

holder considerations to the forefront.

A more neutral and less politically charged definition of corporate governance is

that the latter deals with conflicts of interests between

• the providers of finance and the managers;

• the shareholders and the stakeholders;

• different types of shareholders (mainly the large shareholder and the minority

shareholders);

and the prevention or mitigation of these conflicts of interests. This is the defini

tion which is adopted in this book. Another important advantage of this definition

is that it can be applied to a variety of corporate governance systems. More pre

cisely, this definition does not assume that problems of corporate governance are

limited to the failure of the management to look after the interests of the firm's

shareholders, but it also covers other possible corporate governance problems ·

which are more likely to emerge in countries where corporations are characterised

by concentrated ownership and control. These corporate governance problems nor

mally consist of conflicts of interests between the firm's large shareholder and its

minority shareholders.

One of the first codes of best practice on corporate governance, if not even the

very first one, was the Cadbury Report which was issued in 1992 in the United

Kingdom.9 The Cadbury Report defines corporate governance as 'the system by

which companies are directed and controlled'. However, in the following sentences

the Report then goes on to mention what it considers to be the crucial role of

boards of directors in corporate governance:

'Boards of directors are responsible for the governance of their companies. The share

holders' role in governance is to appoint the directors and the auditors and to satisty

themselves that an appropriate governance structure is in place. The responsibilities of

the board include setting the company's strategic aims, providing the leadership to put

them into effect, supervising the management of the business and reporting to share

holders on their stewardship. The board's actions are subject to laws, regulations and

the shareholders in general meeting.'

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.

Related Documents

Islamic Corporate Governance and Financial Products in Australialg...

|8

|2262

|487

Political and Government Connections on Corporate Boards in Australialg...

|43

|13221

|19

Literature Review: Legal System in Saudi Arabialg...

|9

|2186

|360

ASA 701 Audit Report on NAB Banklg...

|14

|3186

|108