Comprehensive Review of The Evidence Regarding The Effectiveness of Community

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/08

|14

|11076

|22

AI Summary

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

VIEWPOINTSPAPERS

journal of

health

global

Henry B Perry1,

Bahie M Rassekh2,

Sundeep Gupta3,

Jess Wilhelm1,

Paul A Freeman4,5

1 Department of International

Health, Johns Hopkins

Bloomberg School of

Public Health, Baltimore,

Maryland, USA

2 The World Bank,

Washington DC, USA

3 Medical Epidemiologist,

Lusaka, Zambia

4 Independent consultant,

Seattle, Washington, USA

5 Department of Global

Health, University of

Washington, Seattle,

Washington, USA

Correspondence to:

Henry Perry

Room E8537

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg

School of Public Health

615 North Wolfe St.

Baltimore, MD 21205

USA

hperry2@jhu.edu

Comprehensive review of the evidence regar

effectiveness of community–based primary h

care in improving maternal, neonatal and chi

1. rationale, methods and database descripti

Background Community–based primary health care (CBPHC) is an approach u

health programs to extend preventive and curative health services beyond hea

into communities and even down to households. Evidence of the effectiveness o

in improving maternal, neonatal and child health (MNCH) has been summarized

ers, but our review gives gives particular attention to not only the effectiveness

interventions but also their delivery strategies at the community level along wit

uity effects. This is the first article in a series that summarizes and analyzes the

of programs, projects, and research studies (referred to collectively as projects)

CBPHC to improve MNCH in low– and middle–income countries. The review add

the following questions: (1) What kinds of projects were implemented? (2) Wha

outcomes of these projects? (3) What kinds of implementation strategies were u

What are the implications of these findings?

Methods 12 166 reports were identified through a search of articles in the Nat

of Medicine database (PubMed). In addition, reports in the gray literature (avail

but not published in a peer–reviewed journal) were also reviewed. Reports that

the implementation of one or more community–based interventions or an integ

ect in which an assessment of the effectiveness of the project was carried out q

inclusion in the review. Outcome measures that qualified for inclusion in the rev

population–based indicators that defined some aspect of health status: changes

tion coverage of evidence–based interventions or changes in serious morbidity,

tional status, or in mortality.

Results 700 assessments qualified for inclusion in the review. Two independen

completed a data extraction form for each assessment. A third reviewer compa

data extraction forms and resolved any differences. The maternal interventions

cerned education about warning signs of pregnancy and safe delivery; promotio

provision of antenatal care; promotion and/or provision of safe delivery by a tra

tendant, screening and treatment for HIV infection and other maternal infection

planning, and; HIV prevention and treatment. The neonatal and child health inte

that were assessed concerned promotion or provision of good nutrition and imm

promotion of healthy household behaviors and appropriate utilization of health

agnosis and treatment of acute neonatal and child illness; and provision and/or

of safe water, sanitation and hygiene. Two–thirds of assessments (63.0%) were

implementing three or fewer interventions in relatively small populations for rel

periods; half of the assessments involved fewer than 5000 women or children, a

of the assessments were for projects lasting less than 3 years. One–quarter (26

projects were from three countries in South Asia: India, Bangladesh and Nepal.

of reports has grown markedly during the past decade. A small number of fund

ed most of the assessments, led by the United States Agency for International D

The reviewers judged the methodology for 90% of the assessments to be adequ

Conclusions The evidence regarding the effectiveness of community–based in

to improve the health of mothers, neonates, and children younger than 5 years

growing rapidly. The database created for this review serves as the basis for a s

cles that follow this one on the effectiveness of CBPHC in improving MNCH publ

the Journal of Global Health. These findings, guide this review, that are included

paper in this series, will help to provide the rationale for building stronger comm

based platforms for delivering evidence–based interventions in high–mortality,

constrained settings.

Electronic supplementary material:

The online version of this article contains supplementary material.

www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901 1 June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901

journal of

health

global

Henry B Perry1,

Bahie M Rassekh2,

Sundeep Gupta3,

Jess Wilhelm1,

Paul A Freeman4,5

1 Department of International

Health, Johns Hopkins

Bloomberg School of

Public Health, Baltimore,

Maryland, USA

2 The World Bank,

Washington DC, USA

3 Medical Epidemiologist,

Lusaka, Zambia

4 Independent consultant,

Seattle, Washington, USA

5 Department of Global

Health, University of

Washington, Seattle,

Washington, USA

Correspondence to:

Henry Perry

Room E8537

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg

School of Public Health

615 North Wolfe St.

Baltimore, MD 21205

USA

hperry2@jhu.edu

Comprehensive review of the evidence regar

effectiveness of community–based primary h

care in improving maternal, neonatal and chi

1. rationale, methods and database descripti

Background Community–based primary health care (CBPHC) is an approach u

health programs to extend preventive and curative health services beyond hea

into communities and even down to households. Evidence of the effectiveness o

in improving maternal, neonatal and child health (MNCH) has been summarized

ers, but our review gives gives particular attention to not only the effectiveness

interventions but also their delivery strategies at the community level along wit

uity effects. This is the first article in a series that summarizes and analyzes the

of programs, projects, and research studies (referred to collectively as projects)

CBPHC to improve MNCH in low– and middle–income countries. The review add

the following questions: (1) What kinds of projects were implemented? (2) Wha

outcomes of these projects? (3) What kinds of implementation strategies were u

What are the implications of these findings?

Methods 12 166 reports were identified through a search of articles in the Nat

of Medicine database (PubMed). In addition, reports in the gray literature (avail

but not published in a peer–reviewed journal) were also reviewed. Reports that

the implementation of one or more community–based interventions or an integ

ect in which an assessment of the effectiveness of the project was carried out q

inclusion in the review. Outcome measures that qualified for inclusion in the rev

population–based indicators that defined some aspect of health status: changes

tion coverage of evidence–based interventions or changes in serious morbidity,

tional status, or in mortality.

Results 700 assessments qualified for inclusion in the review. Two independen

completed a data extraction form for each assessment. A third reviewer compa

data extraction forms and resolved any differences. The maternal interventions

cerned education about warning signs of pregnancy and safe delivery; promotio

provision of antenatal care; promotion and/or provision of safe delivery by a tra

tendant, screening and treatment for HIV infection and other maternal infection

planning, and; HIV prevention and treatment. The neonatal and child health inte

that were assessed concerned promotion or provision of good nutrition and imm

promotion of healthy household behaviors and appropriate utilization of health

agnosis and treatment of acute neonatal and child illness; and provision and/or

of safe water, sanitation and hygiene. Two–thirds of assessments (63.0%) were

implementing three or fewer interventions in relatively small populations for rel

periods; half of the assessments involved fewer than 5000 women or children, a

of the assessments were for projects lasting less than 3 years. One–quarter (26

projects were from three countries in South Asia: India, Bangladesh and Nepal.

of reports has grown markedly during the past decade. A small number of fund

ed most of the assessments, led by the United States Agency for International D

The reviewers judged the methodology for 90% of the assessments to be adequ

Conclusions The evidence regarding the effectiveness of community–based in

to improve the health of mothers, neonates, and children younger than 5 years

growing rapidly. The database created for this review serves as the basis for a s

cles that follow this one on the effectiveness of CBPHC in improving MNCH publ

the Journal of Global Health. These findings, guide this review, that are included

paper in this series, will help to provide the rationale for building stronger comm

based platforms for delivering evidence–based interventions in high–mortality,

constrained settings.

Electronic supplementary material:

The online version of this article contains supplementary material.

www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901 1 June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

VIEWPOINTSPAPERS

Perry et al.

The evidence that community–based interventions can improve maternal, neonatal and child

(MNCH) has been steadily growing over the past several decades [1–3]. Nonetheless, comm

primary health care (CBPHC) as an approach for engaging communities and delivering healt

tions to communities and even down to each household remains an underdeveloped compon

systems in most resource–constrained settings. Except for immunizations and vitamin A sup

tion, population coverage levels of evidence–based MNCH interventions in the countries with

world’s maternal, neonatal and child deaths remains around 50% or less [4]. The evidence r

effectiveness of individual interventions provided at the community level continues to grow.

stand in a moment of time in which the era of the United Nations’ Millennium Development G

ended (2000–2015) and the era of the Sustainable Development Goals has begun (2015–203

now is an opportune time to take stock of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of comm

approaches in improving MNCH and the approaches that have been used to achieve effectiv

Even though major gains have been made around the world in reducing maternal, neonatal,

mortality (MNCH), 8.8 million maternal deaths, stillbirths, neonatal deaths, and deaths of chi

months of age occur each year, mostly from readily preventable or treatable conditions [5].

the 75 countries with 97% of the world’s maternal, perinatal, neonatal and child deaths were

achieve both Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 4 (which called for a two–thirds reduction

der–5 mortality by the year 2015 compared to 1990 levels) and MDG 5 (which called for a th

ters reduction of maternal mortality) [6]. One of the important reasons for this disappointing

the failure to implement and scale up evidence–based community–based interventions.

To date, there has been limited attention given to systematically accumulating and analyzin

range of evidence regarding the effectiveness of CBPHC in improving MNCH, although excel

maries of portions of this evidence do exist [1–3,7–17]. In addition, there appears to be a reb

al primary health care more generally, especially in light of the upcoming 40th anniversary of the signing

of the Declaration of Alma–Ata at the International Conference on Primary Health Care at Alm

zakhstan in 1978, sponsored by the World Health Organization and UNICEF [18]. This article

of a series that highlights the findings of a comprehensive review and analysis of this eviden

and middle–income countries (LMICs).

The context

The global primary health care movement began in the 1960s following the recognition that

were not improving the health of the populations they were serving. At that time, a series of

populations served by hospital–oriented Christian medical mission programs around the wor

strated that the people who had easy access to and used the hospital regularly were no hea

people who did not [19]. This led to the formation of the Christian Medical Commission (CMC

World Council of Churches, which provided a framework and a forum for new thinking about

grams can best improve the health of people in high–mortality, resource–constrained setting

1970s, these discussions involved global health visionaries of their time, including Dame Nit

Jack Bryant, Carl Taylor, and William Foege, all of whom were members of the CMC, and high

ficials at the World Health Organization (WHO), including Halfdan Mahler, then Director–Gen

Ken Newell, Director of Strengthening of Health Services at WHO [20,21]. One of the fruits o

cussions was the seminal WHO publication, Health by the People [22]. This book described a

successful pioneering CBPHC projects around the world and laid the groundwork for the 197

tional Conference on Primary Health Care at Alma–Ata, Kazakhstan and the now renowned D

of Alma–Ata, which called for Health for All by the Year 2000 through primary health care [2

Article V of the 1978 Declaration of Alma–Ata states the following [24]:

“Governments have a responsibility for the health of their people that can be fulfilled only b

equate health and social measures. A main social target of governments, international organ

world community in the coming decades should be the attainment by all peoples of the worl

a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. Pri

the key to attaining this target as part of development in the spirit of social justice.”

The broad concept of primary health care articulated in this Declaration was much more tha

ery of medical services at primary health care centers. Primary health care, as defined by th

of Alma–Ata, involves providing preventive, promotive, curative, and rehabilitative health ca

as close to the community as possible by members of a health team, including community h

June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901 2 www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901

Perry et al.

The evidence that community–based interventions can improve maternal, neonatal and child

(MNCH) has been steadily growing over the past several decades [1–3]. Nonetheless, comm

primary health care (CBPHC) as an approach for engaging communities and delivering healt

tions to communities and even down to each household remains an underdeveloped compon

systems in most resource–constrained settings. Except for immunizations and vitamin A sup

tion, population coverage levels of evidence–based MNCH interventions in the countries with

world’s maternal, neonatal and child deaths remains around 50% or less [4]. The evidence r

effectiveness of individual interventions provided at the community level continues to grow.

stand in a moment of time in which the era of the United Nations’ Millennium Development G

ended (2000–2015) and the era of the Sustainable Development Goals has begun (2015–203

now is an opportune time to take stock of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of comm

approaches in improving MNCH and the approaches that have been used to achieve effectiv

Even though major gains have been made around the world in reducing maternal, neonatal,

mortality (MNCH), 8.8 million maternal deaths, stillbirths, neonatal deaths, and deaths of chi

months of age occur each year, mostly from readily preventable or treatable conditions [5].

the 75 countries with 97% of the world’s maternal, perinatal, neonatal and child deaths were

achieve both Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 4 (which called for a two–thirds reduction

der–5 mortality by the year 2015 compared to 1990 levels) and MDG 5 (which called for a th

ters reduction of maternal mortality) [6]. One of the important reasons for this disappointing

the failure to implement and scale up evidence–based community–based interventions.

To date, there has been limited attention given to systematically accumulating and analyzin

range of evidence regarding the effectiveness of CBPHC in improving MNCH, although excel

maries of portions of this evidence do exist [1–3,7–17]. In addition, there appears to be a reb

al primary health care more generally, especially in light of the upcoming 40th anniversary of the signing

of the Declaration of Alma–Ata at the International Conference on Primary Health Care at Alm

zakhstan in 1978, sponsored by the World Health Organization and UNICEF [18]. This article

of a series that highlights the findings of a comprehensive review and analysis of this eviden

and middle–income countries (LMICs).

The context

The global primary health care movement began in the 1960s following the recognition that

were not improving the health of the populations they were serving. At that time, a series of

populations served by hospital–oriented Christian medical mission programs around the wor

strated that the people who had easy access to and used the hospital regularly were no hea

people who did not [19]. This led to the formation of the Christian Medical Commission (CMC

World Council of Churches, which provided a framework and a forum for new thinking about

grams can best improve the health of people in high–mortality, resource–constrained setting

1970s, these discussions involved global health visionaries of their time, including Dame Nit

Jack Bryant, Carl Taylor, and William Foege, all of whom were members of the CMC, and high

ficials at the World Health Organization (WHO), including Halfdan Mahler, then Director–Gen

Ken Newell, Director of Strengthening of Health Services at WHO [20,21]. One of the fruits o

cussions was the seminal WHO publication, Health by the People [22]. This book described a

successful pioneering CBPHC projects around the world and laid the groundwork for the 197

tional Conference on Primary Health Care at Alma–Ata, Kazakhstan and the now renowned D

of Alma–Ata, which called for Health for All by the Year 2000 through primary health care [2

Article V of the 1978 Declaration of Alma–Ata states the following [24]:

“Governments have a responsibility for the health of their people that can be fulfilled only b

equate health and social measures. A main social target of governments, international organ

world community in the coming decades should be the attainment by all peoples of the worl

a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. Pri

the key to attaining this target as part of development in the spirit of social justice.”

The broad concept of primary health care articulated in this Declaration was much more tha

ery of medical services at primary health care centers. Primary health care, as defined by th

of Alma–Ata, involves providing preventive, promotive, curative, and rehabilitative health ca

as close to the community as possible by members of a health team, including community h

June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901 2 www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901

VIEWPOINTSPAPERS

CBPHC, rationale, methods and database descrip

ers and traditional practitioners, and it broadened the concept even further by calling for p

care to also address the primary causes of ill–health through inter–sectoral collaboration, c

ticipation, and reduction of inequities.

Over the past three decades since the Declaration of Alma–Ata, major progress has been m

ing child and maternal mortality throughout the world. The number of children dying befor

age has declined from 18.9 million in 1960 [25] to 5.9 million in 2015 [26] despite the fact

ber of births each year has increased from 96 million in 1960 [25] to 139 million in 2015 [2

al under–5 mortality rate has declined from 148 per 1000 live births in 1970 [25] to 43 in 2

Over the past 25 years, the global under–5 mortality rate globally has fallen by 53% [26], f

the 67% required to reach the Millennium Development Goal for 2015. Reductions in mate

ity have also been important but more gradual. The number of maternal deaths declined fr

in 1990 to 303 000 in 2015 [28], and the global maternal mortality ratio fell by 44% during

[28], far less than the 75% required to achieve the Millennium Development Goal.

Although evidence about the effectiveness of specific community–based interventions is ge

documented, evidence about the total range of CBPHC interventions for MNCH, their effect

these interventions are actually delivered in practice (particularly in combination with othe

tions), and the conditions that appear to be important for achieving success are less summ

the heart of what our review is about.

Our review begins with the premises that (1) further strengthening CBPHC by expanding th

coverage of evidence–based interventions has the potential to accelerate progress in endin

child and maternal deaths, and (2) CBPHC has the potential for providing an entry point for

a more comprehensive primary health care system in resource–constrained settings that c

systems to more effectively improve population health and, at the same time, more effecti

needs and expectations of local people for medical care.

There is now, more than ever, a need for evaluation of what works and for “systematic sha

practices and greater sharing of new information” [29]. As an editorial in The Lancet [30] o

“Evaluation must now become the top priority in global health. Currently, it is only an after

scale–up in global health investments during the past decade has not been matched by an

evaluation…. [Evaluation] will not only sustain interest in global health. It will improve qual

ing, enhance efficiency, and build capacity for understanding why some programmes work

Evaluation matters. Evaluation is science.”

This series provides an opportunity to summarize, review and analyze the evidence regard

tiveness of CBPHC in improving the health of mothers and their children, to draw conclusio

the findings from this review, and to suggest next steps in research, policy and program im

Background of the review

In the early 1990s, Dr John Wyon (now deceased) and Dr Henry Perry organized panels at t

meetings of the American Public Health Association (APHA) to highlight the contributions o

improving the health of geographically–defined populations. As a result of support and enc

from the International Health Section at APHA and from APHA staff, a Working Group on CB

the International Health Section was established in 1997. For two decades now, the Workin

been holding day–long annual workshops on themes related to CBPHC. One of these works

the publication of a book on CBPHC [31]. As the evidence continued to mount regarding th

of CBPHC in improving health, the Working Group decided that a comprehensive review wa

Thus, beginning in 2005, the Working Group created a Task Force for the Review of the Ev

PHC in Improving Child Health, with Henry Perry and Paul Freeman serving as Co–Chairs. W

as a small volunteer effort by Perry and Freeman and others has now, more than a decade

over 150 people and not only APHA but also the World Health Organization, UNICEF, the W

the US Agency for International Development, Future Generations (the NGO where Dr Perr

ployed at the outset of the review), and most recently the Gates Foundation.

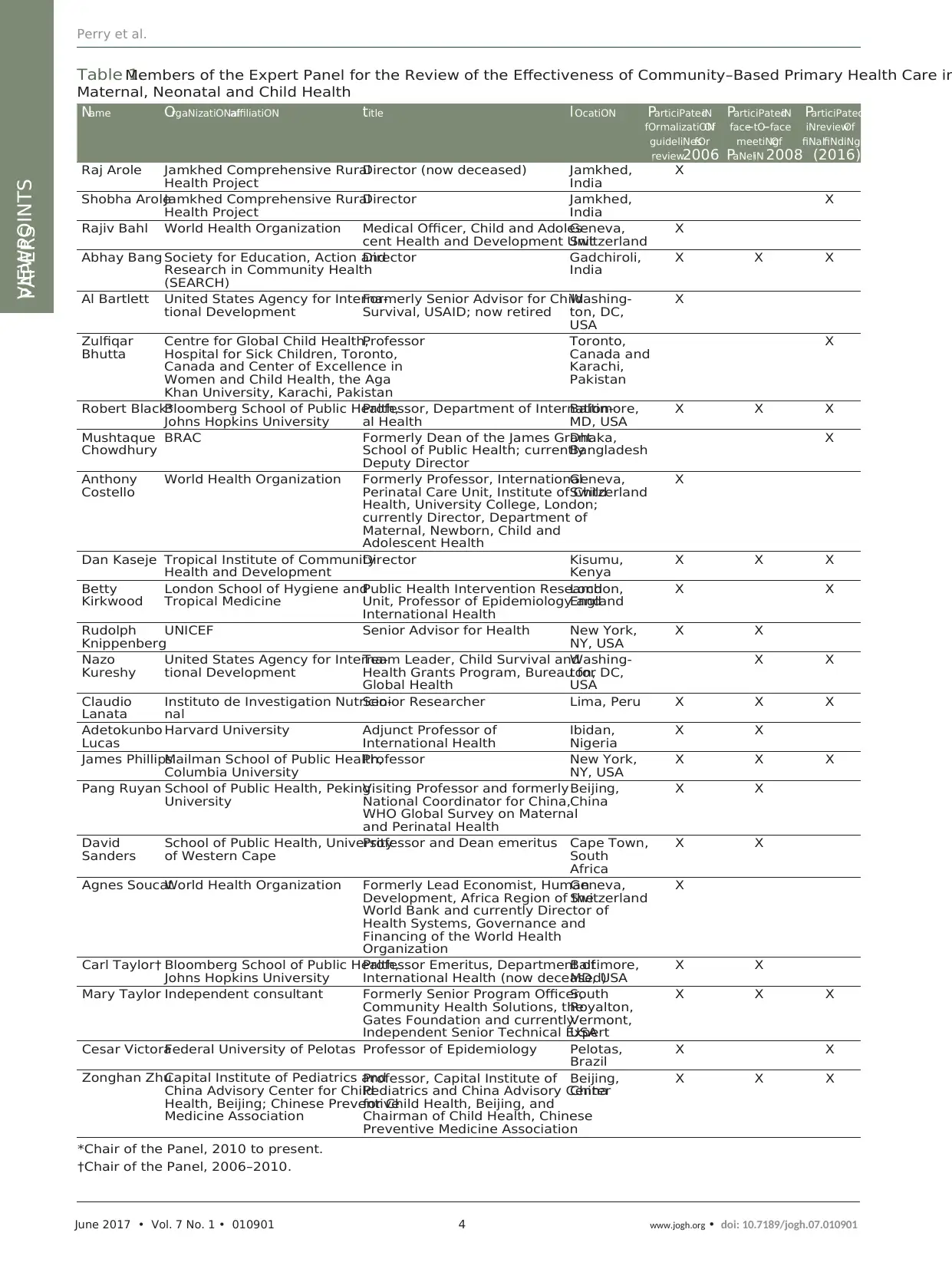

Following an initial small grant from the World Health Organization in 2006, an Expert Pane

ated under the chairmanship of Dr Carl Taylor, then Professor Emeritus of International He

Johns Hopkins University (Table 1). This group participated in the initial design of the revie

later met face to face at UNICEF Headquarters in 2008 to discuss preliminary findings of th

www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901 3 June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901

CBPHC, rationale, methods and database descrip

ers and traditional practitioners, and it broadened the concept even further by calling for p

care to also address the primary causes of ill–health through inter–sectoral collaboration, c

ticipation, and reduction of inequities.

Over the past three decades since the Declaration of Alma–Ata, major progress has been m

ing child and maternal mortality throughout the world. The number of children dying befor

age has declined from 18.9 million in 1960 [25] to 5.9 million in 2015 [26] despite the fact

ber of births each year has increased from 96 million in 1960 [25] to 139 million in 2015 [2

al under–5 mortality rate has declined from 148 per 1000 live births in 1970 [25] to 43 in 2

Over the past 25 years, the global under–5 mortality rate globally has fallen by 53% [26], f

the 67% required to reach the Millennium Development Goal for 2015. Reductions in mate

ity have also been important but more gradual. The number of maternal deaths declined fr

in 1990 to 303 000 in 2015 [28], and the global maternal mortality ratio fell by 44% during

[28], far less than the 75% required to achieve the Millennium Development Goal.

Although evidence about the effectiveness of specific community–based interventions is ge

documented, evidence about the total range of CBPHC interventions for MNCH, their effect

these interventions are actually delivered in practice (particularly in combination with othe

tions), and the conditions that appear to be important for achieving success are less summ

the heart of what our review is about.

Our review begins with the premises that (1) further strengthening CBPHC by expanding th

coverage of evidence–based interventions has the potential to accelerate progress in endin

child and maternal deaths, and (2) CBPHC has the potential for providing an entry point for

a more comprehensive primary health care system in resource–constrained settings that c

systems to more effectively improve population health and, at the same time, more effecti

needs and expectations of local people for medical care.

There is now, more than ever, a need for evaluation of what works and for “systematic sha

practices and greater sharing of new information” [29]. As an editorial in The Lancet [30] o

“Evaluation must now become the top priority in global health. Currently, it is only an after

scale–up in global health investments during the past decade has not been matched by an

evaluation…. [Evaluation] will not only sustain interest in global health. It will improve qual

ing, enhance efficiency, and build capacity for understanding why some programmes work

Evaluation matters. Evaluation is science.”

This series provides an opportunity to summarize, review and analyze the evidence regard

tiveness of CBPHC in improving the health of mothers and their children, to draw conclusio

the findings from this review, and to suggest next steps in research, policy and program im

Background of the review

In the early 1990s, Dr John Wyon (now deceased) and Dr Henry Perry organized panels at t

meetings of the American Public Health Association (APHA) to highlight the contributions o

improving the health of geographically–defined populations. As a result of support and enc

from the International Health Section at APHA and from APHA staff, a Working Group on CB

the International Health Section was established in 1997. For two decades now, the Workin

been holding day–long annual workshops on themes related to CBPHC. One of these works

the publication of a book on CBPHC [31]. As the evidence continued to mount regarding th

of CBPHC in improving health, the Working Group decided that a comprehensive review wa

Thus, beginning in 2005, the Working Group created a Task Force for the Review of the Ev

PHC in Improving Child Health, with Henry Perry and Paul Freeman serving as Co–Chairs. W

as a small volunteer effort by Perry and Freeman and others has now, more than a decade

over 150 people and not only APHA but also the World Health Organization, UNICEF, the W

the US Agency for International Development, Future Generations (the NGO where Dr Perr

ployed at the outset of the review), and most recently the Gates Foundation.

Following an initial small grant from the World Health Organization in 2006, an Expert Pane

ated under the chairmanship of Dr Carl Taylor, then Professor Emeritus of International He

Johns Hopkins University (Table 1). This group participated in the initial design of the revie

later met face to face at UNICEF Headquarters in 2008 to discuss preliminary findings of th

www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901 3 June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901

VIEWPOINTSPAPERS

Table 1.Members of the Expert Panel for the Review of the Effectiveness of Community–Based Primary Health Care in

Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health

Name OrgaNizatiONalaffiliatiON title lOcatiON ParticiPatediN

fOrmalizatiONOf

guideliNesfOr

review2006

ParticiPatediN

face–tO–face

meetiNgOf

PaNeliN 2008

ParticiPated

iNreviewOf

fiNalfiNdiNgs

(2016)

Raj Arole Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural

Health Project

Director (now deceased) Jamkhed,

India

X

Shobha AroleJamkhed Comprehensive Rural

Health Project

Director Jamkhed,

India

X

Rajiv Bahl World Health Organization Medical Officer, Child and Adoles-

cent Health and Development Unit

Geneva,

Switzerland

X

Abhay Bang Society for Education, Action and

Research in Community Health

(SEARCH)

Director Gadchiroli,

India

X X X

Al Bartlett United States Agency for Interna-

tional Development

Formerly Senior Advisor for Child

Survival, USAID; now retired

Washing-

ton, DC,

USA

X

Zulfiqar

Bhutta

Centre for Global Child Health,

Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto,

Canada and Center of Excellence in

Women and Child Health, the Aga

Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

Professor Toronto,

Canada and

Karachi,

Pakistan

X

Robert Black*Bloomberg School of Public Health,

Johns Hopkins University

Professor, Department of Internation-

al Health

Baltimore,

MD, USA

X X X

Mushtaque

Chowdhury

BRAC Formerly Dean of the James Grant

School of Public Health; currently

Deputy Director

Dhaka,

Bangladesh

X

Anthony

Costello

World Health Organization Formerly Professor, International

Perinatal Care Unit, Institute of Child

Health, University College, London;

currently Director, Department of

Maternal, Newborn, Child and

Adolescent Health

Geneva,

Switzerland

X

Dan Kaseje Tropical Institute of Community

Health and Development

Director Kisumu,

Kenya

X X X

Betty

Kirkwood

London School of Hygiene and

Tropical Medicine

Public Health Intervention Research

Unit, Professor of Epidemiology and

International Health

London,

England

X X

Rudolph

Knippenberg

UNICEF Senior Advisor for Health New York,

NY, USA

X X

Nazo

Kureshy

United States Agency for Interna-

tional Development

Team Leader, Child Survival and

Health Grants Program, Bureau for

Global Health

Washing-

ton, DC,

USA

X X

Claudio

Lanata

Instituto de Investigation Nutricio-

nal

Senior Researcher Lima, Peru X X X

Adetokunbo

Lucas

Harvard University Adjunct Professor of

International Health

Ibidan,

Nigeria

X X

James PhillipsMailman School of Public Health,

Columbia University

Professor New York,

NY, USA

X X X

Pang Ruyan School of Public Health, Peking

University

Visiting Professor and formerly

National Coordinator for China,

WHO Global Survey on Maternal

and Perinatal Health

Beijing,

China

X X

David

Sanders

School of Public Health, University

of Western Cape

Professor and Dean emeritus Cape Town,

South

Africa

X X

Agnes SoucatWorld Health Organization Formerly Lead Economist, Human

Development, Africa Region of the

World Bank and currently Director of

Health Systems, Governance and

Financing of the World Health

Organization

Geneva,

Switzerland

X

Carl Taylor† Bloomberg School of Public Health,

Johns Hopkins University

Professor Emeritus, Department of

International Health (now deceased)

Baltimore,

MD, USA

X X

Mary Taylor Independent consultant Formerly Senior Program Officer,

Community Health Solutions, the

Gates Foundation and currently

Independent Senior Technical Expert

South

Royalton,

Vermont,

USA

X X X

Cesar VictoraFederal University of Pelotas Professor of Epidemiology Pelotas,

Brazil

X X

Zonghan ZhuCapital Institute of Pediatrics and

China Advisory Center for Child

Health, Beijing; Chinese Preventive

Medicine Association

Professor, Capital Institute of

Pediatrics and China Advisory Center

for Child Health, Beijing, and

Chairman of Child Health, Chinese

Preventive Medicine Association

Beijing,

China

X X X

*Chair of the Panel, 2010 to present.

†Chair of the Panel, 2006–2010.

Perry et al.

June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901 4 www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901

Table 1.Members of the Expert Panel for the Review of the Effectiveness of Community–Based Primary Health Care in

Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health

Name OrgaNizatiONalaffiliatiON title lOcatiON ParticiPatediN

fOrmalizatiONOf

guideliNesfOr

review2006

ParticiPatediN

face–tO–face

meetiNgOf

PaNeliN 2008

ParticiPated

iNreviewOf

fiNalfiNdiNgs

(2016)

Raj Arole Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural

Health Project

Director (now deceased) Jamkhed,

India

X

Shobha AroleJamkhed Comprehensive Rural

Health Project

Director Jamkhed,

India

X

Rajiv Bahl World Health Organization Medical Officer, Child and Adoles-

cent Health and Development Unit

Geneva,

Switzerland

X

Abhay Bang Society for Education, Action and

Research in Community Health

(SEARCH)

Director Gadchiroli,

India

X X X

Al Bartlett United States Agency for Interna-

tional Development

Formerly Senior Advisor for Child

Survival, USAID; now retired

Washing-

ton, DC,

USA

X

Zulfiqar

Bhutta

Centre for Global Child Health,

Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto,

Canada and Center of Excellence in

Women and Child Health, the Aga

Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

Professor Toronto,

Canada and

Karachi,

Pakistan

X

Robert Black*Bloomberg School of Public Health,

Johns Hopkins University

Professor, Department of Internation-

al Health

Baltimore,

MD, USA

X X X

Mushtaque

Chowdhury

BRAC Formerly Dean of the James Grant

School of Public Health; currently

Deputy Director

Dhaka,

Bangladesh

X

Anthony

Costello

World Health Organization Formerly Professor, International

Perinatal Care Unit, Institute of Child

Health, University College, London;

currently Director, Department of

Maternal, Newborn, Child and

Adolescent Health

Geneva,

Switzerland

X

Dan Kaseje Tropical Institute of Community

Health and Development

Director Kisumu,

Kenya

X X X

Betty

Kirkwood

London School of Hygiene and

Tropical Medicine

Public Health Intervention Research

Unit, Professor of Epidemiology and

International Health

London,

England

X X

Rudolph

Knippenberg

UNICEF Senior Advisor for Health New York,

NY, USA

X X

Nazo

Kureshy

United States Agency for Interna-

tional Development

Team Leader, Child Survival and

Health Grants Program, Bureau for

Global Health

Washing-

ton, DC,

USA

X X

Claudio

Lanata

Instituto de Investigation Nutricio-

nal

Senior Researcher Lima, Peru X X X

Adetokunbo

Lucas

Harvard University Adjunct Professor of

International Health

Ibidan,

Nigeria

X X

James PhillipsMailman School of Public Health,

Columbia University

Professor New York,

NY, USA

X X X

Pang Ruyan School of Public Health, Peking

University

Visiting Professor and formerly

National Coordinator for China,

WHO Global Survey on Maternal

and Perinatal Health

Beijing,

China

X X

David

Sanders

School of Public Health, University

of Western Cape

Professor and Dean emeritus Cape Town,

South

Africa

X X

Agnes SoucatWorld Health Organization Formerly Lead Economist, Human

Development, Africa Region of the

World Bank and currently Director of

Health Systems, Governance and

Financing of the World Health

Organization

Geneva,

Switzerland

X

Carl Taylor† Bloomberg School of Public Health,

Johns Hopkins University

Professor Emeritus, Department of

International Health (now deceased)

Baltimore,

MD, USA

X X

Mary Taylor Independent consultant Formerly Senior Program Officer,

Community Health Solutions, the

Gates Foundation and currently

Independent Senior Technical Expert

South

Royalton,

Vermont,

USA

X X X

Cesar VictoraFederal University of Pelotas Professor of Epidemiology Pelotas,

Brazil

X X

Zonghan ZhuCapital Institute of Pediatrics and

China Advisory Center for Child

Health, Beijing; Chinese Preventive

Medicine Association

Professor, Capital Institute of

Pediatrics and China Advisory Center

for Child Health, Beijing, and

Chairman of Child Health, Chinese

Preventive Medicine Association

Beijing,

China

X X X

*Chair of the Panel, 2010 to present.

†Chair of the Panel, 2006–2010.

Perry et al.

June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901 4 www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

VIEWPOINTSPAPERS

ter Dr Taylor’s death in 2010, the Panel reconvened under the leadership of Dr Robert Blac

International Health at Johns Hopkins, and has participated in the final set of recommendat

stitute the final article in this series [32].

When the review began in 2006, the focus was exclusively on child health (that is, the hea

in their first 5 years of life). With support from USAID and the Gates Foundation between 2

it became possible to expand the scope of the review to maternal health. Thus, we have no

overall effort a review of the effectiveness of CBPHC in improving MNCH.

Goals of the review

The goal of this review is to summarize the evidence regarding what can be achieved thro

nity–based approaches to improve MNCH. The health of mothers, neonates and children as

outcome is defined here for our purposes as the level of mortality, serious morbidity, nutrit

or coverage of proven interventions for mothers, neonates and children in a geographically

ulation. The review focuses on interventions and approaches that are carried out beyond t

health facilities that serve populations of mothers, neonates and children living in geograp

areas.

The review consists of an analysis of documents describing research studies, field projects

(collectively referred to in this series as projects) that have assessed the impact of CBPHC

together, the findings comprise a comprehensive overview of the global evidence in using

prove MNCH. In addition, the review describes the strategies used to deliver community–b

tions and the role of the community and community health workers in implementing these

In addition, the review seeks to understand the context of the projects – where they were i

and by whom, where the funding came from, for how long, what size of population was ser

project, and what additional contextual factors might have influenced the project outcome

the methodological quality of the assessment.

The questions which the review seeks to answer are:

• How strong is the evidence that CBPHC can improve MNCH in geographically defined po

sustain that improvement?

• What specific CBPHC activities improve MNCH?

• What conditions (including those within the local health system) facilitate the effectivene

and what community–based approaches appear to be most effective?

• What characteristics do effective CBPHC activities share?

• What program elements are correlated with improvements in child and maternal health?

• How strong is the evidence that partnerships between communities and health systems

order to improve child and maternal health?

• How strong is the evidence that CBPHC can promote equity?

• What general lessons can be drawn from the findings of this review?

• What additional research is needed?

• How can successful community–based approaches for improving MNCH be scaled up to

national levels within the context of serious financial and human resource constraints?

• What are the implications for local, national and global health policy, for program implem

for donors?

METHODS

The Task Force and the Expert Panel agreed on the following definition of CBPHC:

CBPHC is a process through which health programs and communities work together to imp

and control disease. CBPHC includes the promotion of key behaviors at the household leve

the provision of health care and health services outside of health facilities at the communi

can (and of course should) connect to existing health services, health programs, and healt

at static facilities (including health centers and hospitals) and be closely integrated with th

CBPHC, rationale, methods and database descrip

www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901 5 June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901

ter Dr Taylor’s death in 2010, the Panel reconvened under the leadership of Dr Robert Blac

International Health at Johns Hopkins, and has participated in the final set of recommendat

stitute the final article in this series [32].

When the review began in 2006, the focus was exclusively on child health (that is, the hea

in their first 5 years of life). With support from USAID and the Gates Foundation between 2

it became possible to expand the scope of the review to maternal health. Thus, we have no

overall effort a review of the effectiveness of CBPHC in improving MNCH.

Goals of the review

The goal of this review is to summarize the evidence regarding what can be achieved thro

nity–based approaches to improve MNCH. The health of mothers, neonates and children as

outcome is defined here for our purposes as the level of mortality, serious morbidity, nutrit

or coverage of proven interventions for mothers, neonates and children in a geographically

ulation. The review focuses on interventions and approaches that are carried out beyond t

health facilities that serve populations of mothers, neonates and children living in geograp

areas.

The review consists of an analysis of documents describing research studies, field projects

(collectively referred to in this series as projects) that have assessed the impact of CBPHC

together, the findings comprise a comprehensive overview of the global evidence in using

prove MNCH. In addition, the review describes the strategies used to deliver community–b

tions and the role of the community and community health workers in implementing these

In addition, the review seeks to understand the context of the projects – where they were i

and by whom, where the funding came from, for how long, what size of population was ser

project, and what additional contextual factors might have influenced the project outcome

the methodological quality of the assessment.

The questions which the review seeks to answer are:

• How strong is the evidence that CBPHC can improve MNCH in geographically defined po

sustain that improvement?

• What specific CBPHC activities improve MNCH?

• What conditions (including those within the local health system) facilitate the effectivene

and what community–based approaches appear to be most effective?

• What characteristics do effective CBPHC activities share?

• What program elements are correlated with improvements in child and maternal health?

• How strong is the evidence that partnerships between communities and health systems

order to improve child and maternal health?

• How strong is the evidence that CBPHC can promote equity?

• What general lessons can be drawn from the findings of this review?

• What additional research is needed?

• How can successful community–based approaches for improving MNCH be scaled up to

national levels within the context of serious financial and human resource constraints?

• What are the implications for local, national and global health policy, for program implem

for donors?

METHODS

The Task Force and the Expert Panel agreed on the following definition of CBPHC:

CBPHC is a process through which health programs and communities work together to imp

and control disease. CBPHC includes the promotion of key behaviors at the household leve

the provision of health care and health services outside of health facilities at the communi

can (and of course should) connect to existing health services, health programs, and healt

at static facilities (including health centers and hospitals) and be closely integrated with th

CBPHC, rationale, methods and database descrip

www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901 5 June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901

VIEWPOINTSPAPERS

CBPHC involves improving the health of a geographically defined population through outreac

of health facilities. CBPHC does not include health care provided at a health facility unless th

munity involvement and associated services beyond the facility.

CBPHC also includes multi–sectoral approaches to health improvement beyond the provision

services per se, including programs that seek to improve (directly or indirectly) education, in

trition, living standards, and empowerment.

CBPHC programs may or may not collaborate with governmental or private health care prog

may be comprehensive in scope, highly selective, or somewhere in between; and they may

part of a program which includes the provision of services at health facilities.

CBPHC includes the following three different types of interventions:

• Health communication with individuals, families and communities;

• Social mobilization and community involvement for planning, delivering, evaluating and u

services; and

• Provision of health care in the community, including preventive services (eg, immunizatio

tive services (eg, community–based treatment of pneumonia).

Types of assessments of maternal, neonatal and child health interve

qualifying for review

The Task Force sought documents that described community–based programs, projects and

studies that carried out assessments of changes in MNCH indicators in such a way that any c

served could reasonably be attributed to CBPHC program interventions. At least one of the f

come indicators was required to be present in order for the assessment to be included in the

Maternal health

• Change in the population coverage of one or more evidence–based interventions (utilizati

tal care, delivery by a trained attendant, delivery in a health facility, clean delivery, and po

• Change in nutritional status

• Change in the incidence or in the outcome of serious, life–threatening morbidity (such as

sia, eclampsia, sepsis, hemorrhage); or,

• Change in mortality.

Neonatal and child health

• Change in the population coverage of one or more evidence–based interventions (clean d

propriate care during the neonatal period; appropriate infant and young child feeding, inclu

propriate breastfeeding; immunizations; vitamin A supplementation; appropriate preventio

ia with insecticide–treated bed nets and intermittent preventive therapy; appropriate hand

appropriate treatment of drinking water, appropriate sanitation; appropriate treatment of p

diarrhea and malaria;

• Change in nutritional status (as measured by anthropometry, anemia, or assessment of m

deficiency);

• Change in the incidence or in the outcome of serious but non–life–threatening morbidity (

choma, which can result in blindness);

• Change in the incidence or in the outcome of serious, life–threatening morbidity (such as

diarrhea, malaria, and low–birth weight); or,

• Change in mortality (perinatal, neonatal, infant, 1–4–year, and under–5 mortality);

In addition, the review included an analysis of available documentation concerning the degre

improvements in child health obtained by CBPHC approaches were equitable.

Document retrieval

The principal inclusion criteria for the literature review were: (1) a report describing the CBP

for a defined geographic population and (2) a description of the findings of an assessment o

effect on maternal, neonatal or child health as defined above. The focus was on the effective

gram interventions on the health of all mothers and/or children in a geographically defined a

Perry et al.

June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901 6 www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901

CBPHC involves improving the health of a geographically defined population through outreac

of health facilities. CBPHC does not include health care provided at a health facility unless th

munity involvement and associated services beyond the facility.

CBPHC also includes multi–sectoral approaches to health improvement beyond the provision

services per se, including programs that seek to improve (directly or indirectly) education, in

trition, living standards, and empowerment.

CBPHC programs may or may not collaborate with governmental or private health care prog

may be comprehensive in scope, highly selective, or somewhere in between; and they may

part of a program which includes the provision of services at health facilities.

CBPHC includes the following three different types of interventions:

• Health communication with individuals, families and communities;

• Social mobilization and community involvement for planning, delivering, evaluating and u

services; and

• Provision of health care in the community, including preventive services (eg, immunizatio

tive services (eg, community–based treatment of pneumonia).

Types of assessments of maternal, neonatal and child health interve

qualifying for review

The Task Force sought documents that described community–based programs, projects and

studies that carried out assessments of changes in MNCH indicators in such a way that any c

served could reasonably be attributed to CBPHC program interventions. At least one of the f

come indicators was required to be present in order for the assessment to be included in the

Maternal health

• Change in the population coverage of one or more evidence–based interventions (utilizati

tal care, delivery by a trained attendant, delivery in a health facility, clean delivery, and po

• Change in nutritional status

• Change in the incidence or in the outcome of serious, life–threatening morbidity (such as

sia, eclampsia, sepsis, hemorrhage); or,

• Change in mortality.

Neonatal and child health

• Change in the population coverage of one or more evidence–based interventions (clean d

propriate care during the neonatal period; appropriate infant and young child feeding, inclu

propriate breastfeeding; immunizations; vitamin A supplementation; appropriate preventio

ia with insecticide–treated bed nets and intermittent preventive therapy; appropriate hand

appropriate treatment of drinking water, appropriate sanitation; appropriate treatment of p

diarrhea and malaria;

• Change in nutritional status (as measured by anthropometry, anemia, or assessment of m

deficiency);

• Change in the incidence or in the outcome of serious but non–life–threatening morbidity (

choma, which can result in blindness);

• Change in the incidence or in the outcome of serious, life–threatening morbidity (such as

diarrhea, malaria, and low–birth weight); or,

• Change in mortality (perinatal, neonatal, infant, 1–4–year, and under–5 mortality);

In addition, the review included an analysis of available documentation concerning the degre

improvements in child health obtained by CBPHC approaches were equitable.

Document retrieval

The principal inclusion criteria for the literature review were: (1) a report describing the CBP

for a defined geographic population and (2) a description of the findings of an assessment o

effect on maternal, neonatal or child health as defined above. The focus was on the effective

gram interventions on the health of all mothers and/or children in a geographically defined a

Perry et al.

June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901 6 www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901

VIEWPOINTSPAPERS

in some cases (eg, in studies of maternal–to–child

HIV transmission), the focus was on a subset of

mothers and their children in a geographically de

fined area.

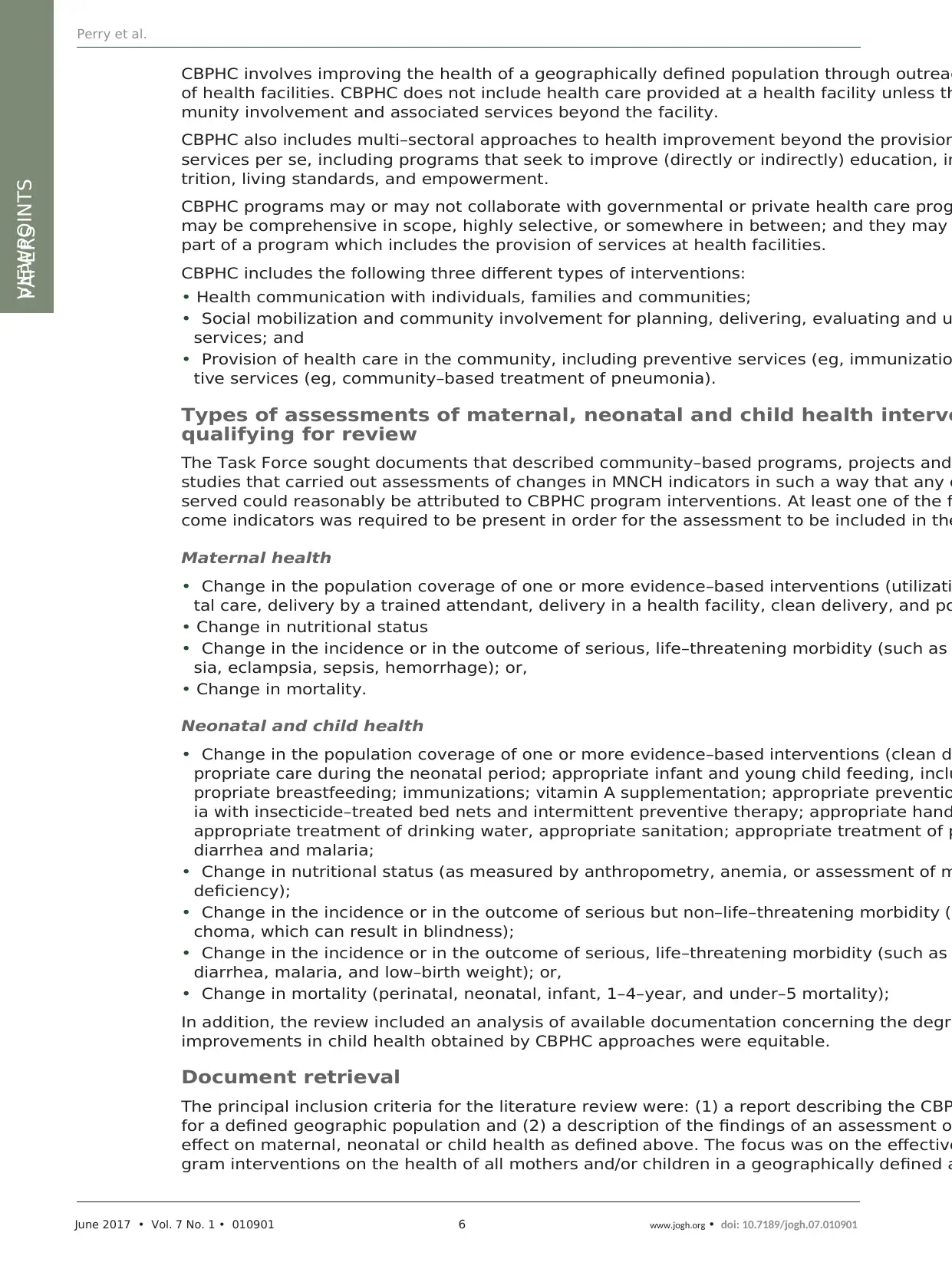

Key terms for “maternal health,” “child health

“community health,” and “developing countries”

related terms were identified to create a search q

(see Tables S1 and S2 in Online Supplementary

Document). The United States National Library o

Medicine’s PubMed database was searched period

cally up until 31 December 2015 using these two

queries, yielding 7890 articles on maternal health

and 4276 articles on neonatal or child health (Fig

ure 1). The articles were screened separately by

members of the study team. Assessments of the e

fectiveness of CBPHC in which the outcomes were

improvements in neurological, emotional or psych

logical development of children were not included

unless the reports also included one or more of th

other neonatal or child health outcome measures

mentioned above.

In addition to the PubMed search, broadcasts wer

sent out on widely used global health listservs, in

cluding those of the Global Health Council, the

American Public Health Association, the Collabora

tion and Resources Group for Child Health (the

CORE Group), the World Federation of Public

Health Associations, and the Association of Schoo

of Public Health asking for information about docu

ments, reports, and published articles which migh

qualify for the review. Finally, the Task Force con-

tacted knowledgeable persons in the field for their suggestions for documents to be includ

members of the Expert Panel. Documents not published in peer–reviewed scientific journal

cluded if they met the criteria for review, if they provided an adequate description of the in

and if they had a satisfactory form of evaluation. A total of 152 assessments met the criter

ternal health review and 548 for the neonatal/child health review (Figure 1).

Table S3 in Online Supplementary Document contains a bibliography with the referenc

with these 700 assessments. The bibliography also indicates which references were in the

review, in the child health review (and which of these were included in the analyses for ne

and child health), and the equity review. There are a number of cases in which a single ass

database is derived from more than one document. All of these references are included in

phy. Thus, when in Figure 1 above we refer to the number of articles/reports, there are a

of cases in which we have combined the various articles/reports associated with a single a

counted this as only one assessment.

Of the 33 maternal health assessments and the 115 neonatal/child health assessments inc

view that were not identified through PubMed, most (16 and 80, respectively) were project

of child survival projects funded by the USAID Child Survival and Health Grants Program an

mented by US–based non–governmental organizations. These are listed separately in Table

Supplementary Document. Other assessments that were not identified through PubMed

tions from other sources, books, or book chapters.

The document review process

Two data extraction forms were prepared through an iterative process. The extraction form

child health assessments and the form for maternal health assessments were identical exc

terventions carried out. These forms are contained in Appendices S5 and S6 in Online Sup

Figure 1.Selection process of assessments of the effectiveness of commu-

nity-based primary health care (CBPHC).

CBPHC, rationale, methods and database descrip

www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901 7 June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901

in some cases (eg, in studies of maternal–to–child

HIV transmission), the focus was on a subset of

mothers and their children in a geographically de

fined area.

Key terms for “maternal health,” “child health

“community health,” and “developing countries”

related terms were identified to create a search q

(see Tables S1 and S2 in Online Supplementary

Document). The United States National Library o

Medicine’s PubMed database was searched period

cally up until 31 December 2015 using these two

queries, yielding 7890 articles on maternal health

and 4276 articles on neonatal or child health (Fig

ure 1). The articles were screened separately by

members of the study team. Assessments of the e

fectiveness of CBPHC in which the outcomes were

improvements in neurological, emotional or psych

logical development of children were not included

unless the reports also included one or more of th

other neonatal or child health outcome measures

mentioned above.

In addition to the PubMed search, broadcasts wer

sent out on widely used global health listservs, in

cluding those of the Global Health Council, the

American Public Health Association, the Collabora

tion and Resources Group for Child Health (the

CORE Group), the World Federation of Public

Health Associations, and the Association of Schoo

of Public Health asking for information about docu

ments, reports, and published articles which migh

qualify for the review. Finally, the Task Force con-

tacted knowledgeable persons in the field for their suggestions for documents to be includ

members of the Expert Panel. Documents not published in peer–reviewed scientific journal

cluded if they met the criteria for review, if they provided an adequate description of the in

and if they had a satisfactory form of evaluation. A total of 152 assessments met the criter

ternal health review and 548 for the neonatal/child health review (Figure 1).

Table S3 in Online Supplementary Document contains a bibliography with the referenc

with these 700 assessments. The bibliography also indicates which references were in the

review, in the child health review (and which of these were included in the analyses for ne

and child health), and the equity review. There are a number of cases in which a single ass

database is derived from more than one document. All of these references are included in

phy. Thus, when in Figure 1 above we refer to the number of articles/reports, there are a

of cases in which we have combined the various articles/reports associated with a single a

counted this as only one assessment.

Of the 33 maternal health assessments and the 115 neonatal/child health assessments inc

view that were not identified through PubMed, most (16 and 80, respectively) were project

of child survival projects funded by the USAID Child Survival and Health Grants Program an

mented by US–based non–governmental organizations. These are listed separately in Table

Supplementary Document. Other assessments that were not identified through PubMed

tions from other sources, books, or book chapters.

The document review process

Two data extraction forms were prepared through an iterative process. The extraction form

child health assessments and the form for maternal health assessments were identical exc

terventions carried out. These forms are contained in Appendices S5 and S6 in Online Sup

Figure 1.Selection process of assessments of the effectiveness of commu-

nity-based primary health care (CBPHC).

CBPHC, rationale, methods and database descrip

www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901 7 June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

VIEWPOINTSPAPERS

Document. Both forms were developed with the purpose of extracting all possible informat

regarding how the interventions were implemented at the community level and what the rol

munity was in implementation.

Two independent reviewers each completed a Data Extraction Form for each assessment th

for the review. A third reviewer provided quality control and resolved any difference observe

reviews, and the final summative review was transferred to an EPI INFO database (version 3

Info, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA). The names of th

ers, many of whom worked on a volunteer basis, are shown in the acknowledgment section;

and professional titles are contained in Table S7 in Online Supplementary Document.

Comment on terminology used

The assessments included in our review were carried out for field studies, projects, and prog

employed one or more CBPHC interventions for improving maternal, neonatal and/or child h

is a heterogeneous group of assessments in the sense that they range from (1) research rep

the efficacy of single interventions over a short period of time in a highly supervised and we

field setting to (2) assessments of programs which provided a comprehensive array of health

opment programs over a long period of time in more typical field setting. When referring to

of community–level activities as a whole, they should properly be referred to as “research st

projects/programs” but for practicality’s sake we will refer to them throughout this series sim

ects,” and the evaluations of their effectiveness as “assessments.”

Database description

An electronic database describing 700 assessments of the effectiveness of CBPHC in improv

was queried using EPI INFO version 3.5.4 and STATA version 14 (StatCorp LLC, College Statio

USA). For the purpose of this review, the 39 assessments with both maternal and child healt

have been counted as separate assessments in our analysis. Overall, 78.8% of assessments

articles published in peer–reviewed journals, 4.0% are some other type of publication (mostl

reports not available on the internet), and 12.7% are either from the gray literature (availab

ternet) or unpublished project evaluations.

Over three–fourths (78.4%) of the assessments included in our review were carried out in ru

at least in part, while 16.9% and 11.1% were carried out exclusively in an urban or peri–urba

respectively.

Among the 700 assessments in our data set, a small proportion contained data from more th

try. Thus, altogether, 786 country–specific assessments were identified. India, Bangladesh, a

the largest number of assessments (86, 77, and 47, respectively). 49.0% of the country–spe

ments came from Africa WHO Region, 28.5% from the South–East Asia Region, and 9.7% fro

icas (Table 2 and Table S8 in Online Supplementary Document). 8.6% of reports assess

in a single community, 38.1% in a set of communities not encompassing an entire health dis

province), 37.5% at the district (or sub–province) level, 7.5% at the provincial/state level, 3.7

tional level, and 3.2% at a multinational level.

The implementing and facilitating organizations for these projects were primarily private ent

universities and research organizations), often working with governments at the national, pr

local level (Table 3). While communities were — by definition — involved in all of these proj

only 4.3% of assessments were local communities the only identified implementers. Those w

implemented projects at the local level were community health workers (CHWs), local comm

bers, research workers, and government health staff.

Half (49.3%) of the assessments are of projects serving 5000 or fewer women and children.

assessments are based on data derived from projects reaching more than 25 000 women an

61.9% of the projects had begun since 2000. Almost half (46.3%) of projects were less than

duration and almost two–thirds (62.9%) were implemented for less than 3 years. Among the

and child health assessments, 51.6% were of only one intervention, and 87.4% were of four

terventions. On the other hand, among the maternal health assessments three–quarters (75

ed five or more interventions.

Our review includes 16 assessments of projects that were completed before 1980. The earlie

scribes the health impact of an integrated primary health care project in South Africa led by

Perry et al.

June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901 8 www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901

Document. Both forms were developed with the purpose of extracting all possible informat

regarding how the interventions were implemented at the community level and what the rol

munity was in implementation.

Two independent reviewers each completed a Data Extraction Form for each assessment th

for the review. A third reviewer provided quality control and resolved any difference observe

reviews, and the final summative review was transferred to an EPI INFO database (version 3

Info, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA). The names of th

ers, many of whom worked on a volunteer basis, are shown in the acknowledgment section;

and professional titles are contained in Table S7 in Online Supplementary Document.

Comment on terminology used

The assessments included in our review were carried out for field studies, projects, and prog

employed one or more CBPHC interventions for improving maternal, neonatal and/or child h

is a heterogeneous group of assessments in the sense that they range from (1) research rep

the efficacy of single interventions over a short period of time in a highly supervised and we

field setting to (2) assessments of programs which provided a comprehensive array of health

opment programs over a long period of time in more typical field setting. When referring to

of community–level activities as a whole, they should properly be referred to as “research st

projects/programs” but for practicality’s sake we will refer to them throughout this series sim

ects,” and the evaluations of their effectiveness as “assessments.”

Database description

An electronic database describing 700 assessments of the effectiveness of CBPHC in improv

was queried using EPI INFO version 3.5.4 and STATA version 14 (StatCorp LLC, College Statio

USA). For the purpose of this review, the 39 assessments with both maternal and child healt

have been counted as separate assessments in our analysis. Overall, 78.8% of assessments

articles published in peer–reviewed journals, 4.0% are some other type of publication (mostl

reports not available on the internet), and 12.7% are either from the gray literature (availab

ternet) or unpublished project evaluations.

Over three–fourths (78.4%) of the assessments included in our review were carried out in ru

at least in part, while 16.9% and 11.1% were carried out exclusively in an urban or peri–urba

respectively.

Among the 700 assessments in our data set, a small proportion contained data from more th

try. Thus, altogether, 786 country–specific assessments were identified. India, Bangladesh, a

the largest number of assessments (86, 77, and 47, respectively). 49.0% of the country–spe

ments came from Africa WHO Region, 28.5% from the South–East Asia Region, and 9.7% fro

icas (Table 2 and Table S8 in Online Supplementary Document). 8.6% of reports assess

in a single community, 38.1% in a set of communities not encompassing an entire health dis

province), 37.5% at the district (or sub–province) level, 7.5% at the provincial/state level, 3.7

tional level, and 3.2% at a multinational level.

The implementing and facilitating organizations for these projects were primarily private ent

universities and research organizations), often working with governments at the national, pr

local level (Table 3). While communities were — by definition — involved in all of these proj

only 4.3% of assessments were local communities the only identified implementers. Those w

implemented projects at the local level were community health workers (CHWs), local comm

bers, research workers, and government health staff.

Half (49.3%) of the assessments are of projects serving 5000 or fewer women and children.

assessments are based on data derived from projects reaching more than 25 000 women an

61.9% of the projects had begun since 2000. Almost half (46.3%) of projects were less than

duration and almost two–thirds (62.9%) were implemented for less than 3 years. Among the

and child health assessments, 51.6% were of only one intervention, and 87.4% were of four

terventions. On the other hand, among the maternal health assessments three–quarters (75

ed five or more interventions.

Our review includes 16 assessments of projects that were completed before 1980. The earlie

scribes the health impact of an integrated primary health care project in South Africa led by

Perry et al.

June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901 8 www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901

VIEWPOINTSPAPERS

in the 1940s and published in 1952 [33]. The next earliest report concerns the effectivenes

toxoid immunization in Columbia, South America, published in 1966 [34].

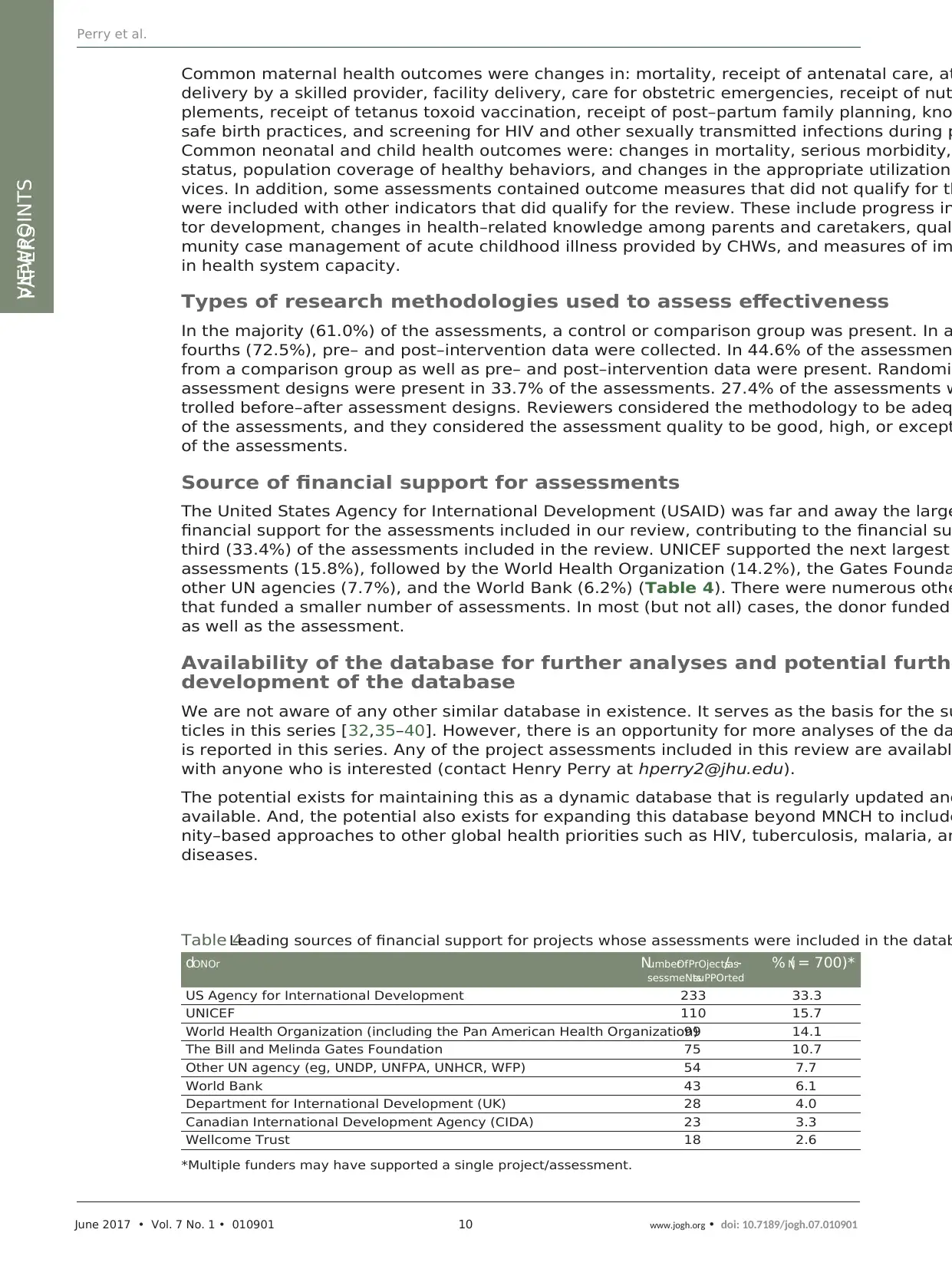

Number of assessments completed ove

time

There has been a rapid growth in the number of asse

ments published between 1980 and 2015, but partic

larly in the period 2001–2011, the decade following t

establishment of the Millennium Development Goals

(MDGs) (Figure 2). The surge in publications is pres

both for maternal and for child/neonatal health studi

(data not shown). In the five years from 2011 until th

end of 2015 when the assessment retrieval ended, t

was a slight decline in the number of publications.

Types of outcomes assessed

We identified a total of 239 outcomes measured in t

700 assessments included in the review: 56 materna

outcomes and 183 neonatal/child outcomes (see Tab

S7 and S8 in Online Supplementary Documen

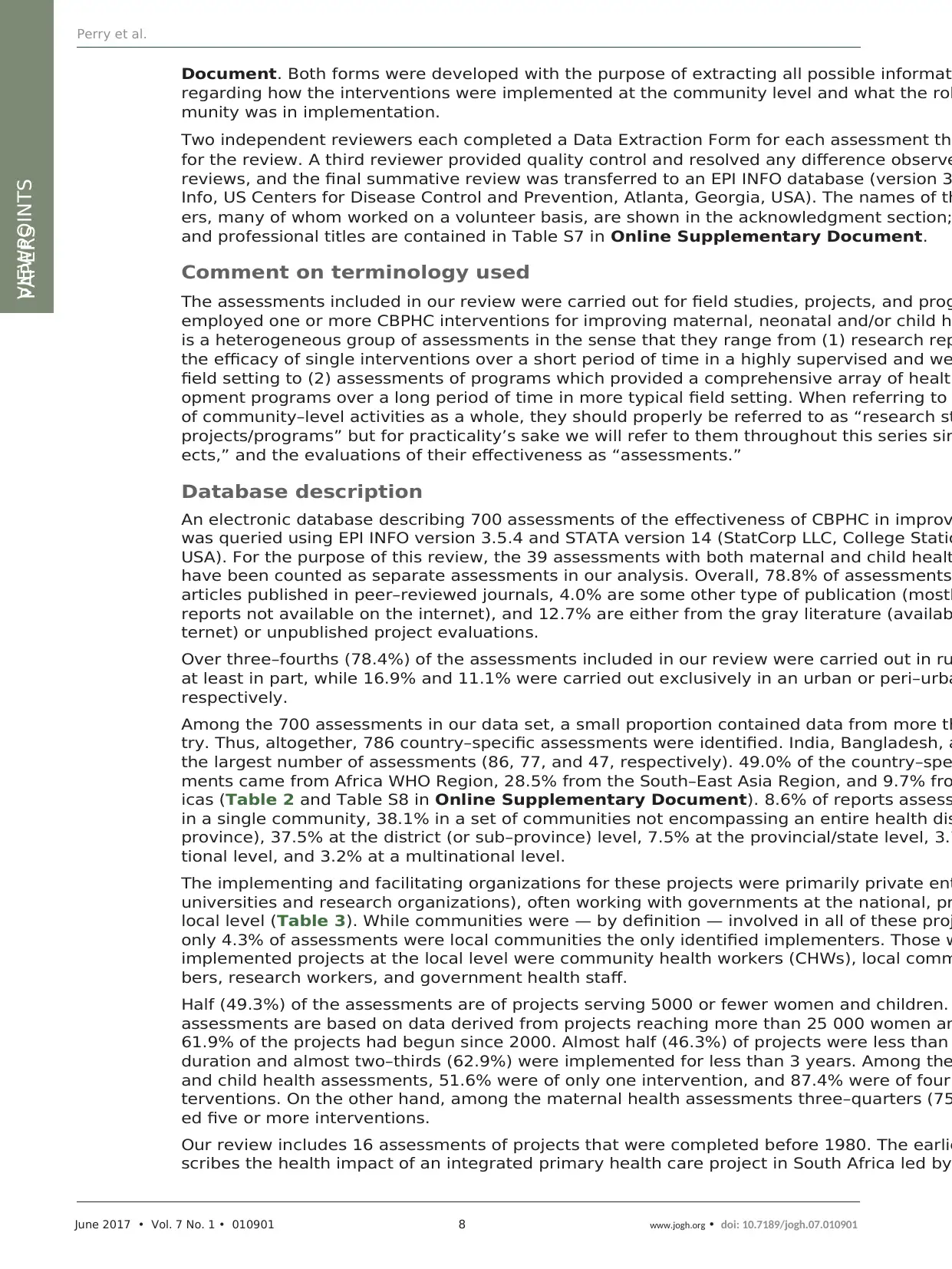

Table 2.Number of assessments of the effectiveness of community–based primary health care in impr

maternal, neonatal and child health by region and the countries with the greatest number of assess

wHO regiON Number % (N = 786)* cOuNtry Number % (N = 786)*

Africa 385 49.0% India 86 10.9

South–East Asia 224 28.5% Bangladesh 77 9.8

Americas 76 9.7% Nepal 47 6.0

Eastern Mediterranean 61 7.8% Ghana 36 4.6

Western Pacific 37 4.7% Pakistan 35 4.5

Europe 4 0.5% Uganda 34 4.3

Total 786* 100.0% Tanzania 30 3.8

Ethiopia 28 3.6

Kenya 27 3.4

Malawi 19 2.4

*The total number of countries listed here exceeds the number of assessments because some assessments were

tiple countries.

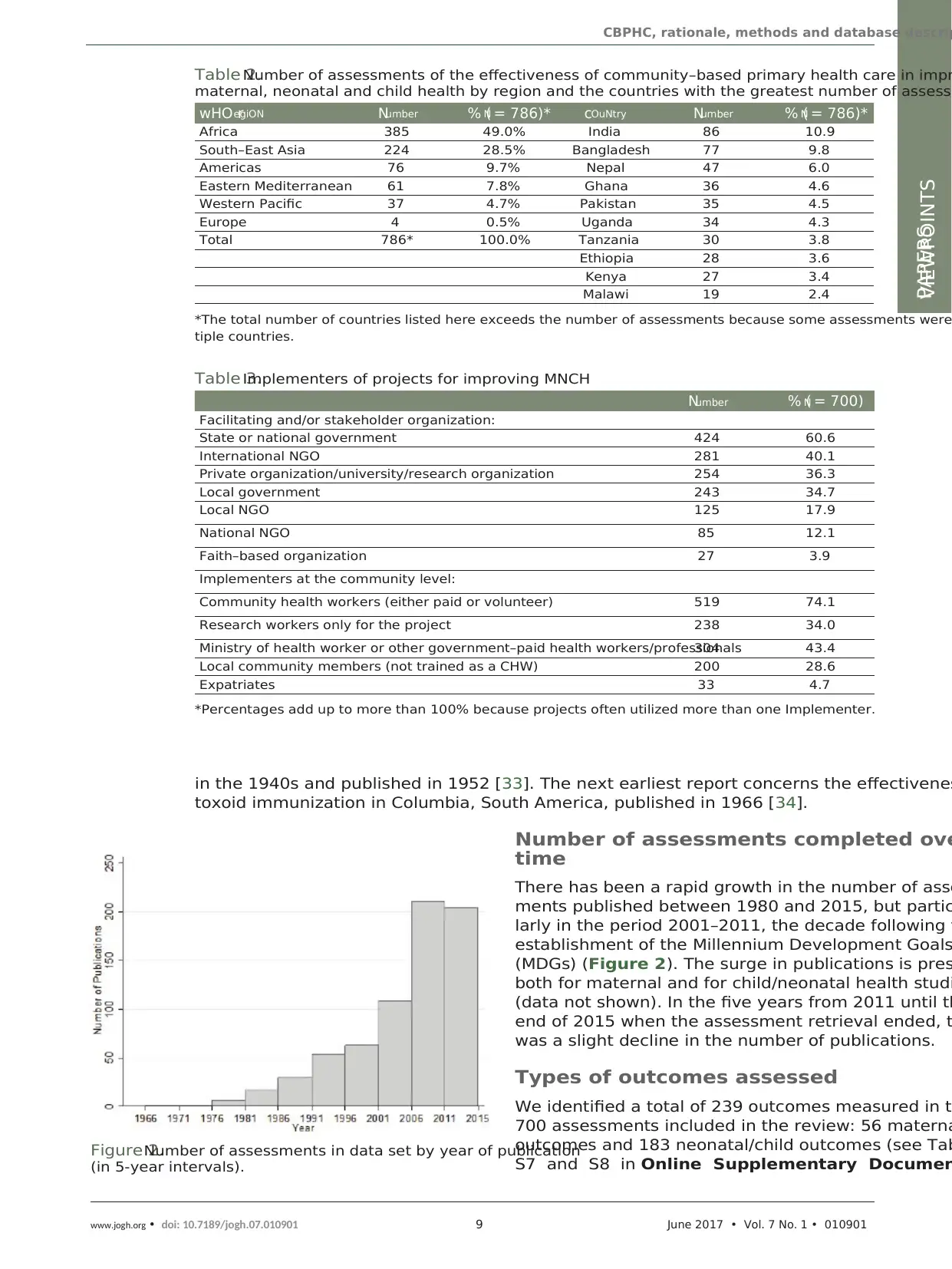

Table 3.Implementers of projects for improving MNCH

Number % (N = 700)

Facilitating and/or stakeholder organization:

State or national government 424 60.6

International NGO 281 40.1

Private organization/university/research organization 254 36.3

Local government 243 34.7

Local NGO 125 17.9

National NGO 85 12.1

Faith–based organization 27 3.9

Implementers at the community level:

Community health workers (either paid or volunteer) 519 74.1

Research workers only for the project 238 34.0

Ministry of health worker or other government–paid health workers/professionals304 43.4

Local community members (not trained as a CHW) 200 28.6

Expatriates 33 4.7

*Percentages add up to more than 100% because projects often utilized more than one Implementer.

Figure 2.Number of assessments in data set by year of publication

(in 5-year intervals).

CBPHC, rationale, methods and database descrip

www.jogh.org • doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010901 9 June 2017 • Vol. 7 No. 1 • 010901

in the 1940s and published in 1952 [33]. The next earliest report concerns the effectivenes

toxoid immunization in Columbia, South America, published in 1966 [34].

Number of assessments completed ove

time

There has been a rapid growth in the number of asse

ments published between 1980 and 2015, but partic

larly in the period 2001–2011, the decade following t

establishment of the Millennium Development Goals

(MDGs) (Figure 2). The surge in publications is pres

both for maternal and for child/neonatal health studi

(data not shown). In the five years from 2011 until th

end of 2015 when the assessment retrieval ended, t

was a slight decline in the number of publications.

Types of outcomes assessed

We identified a total of 239 outcomes measured in t

700 assessments included in the review: 56 materna

outcomes and 183 neonatal/child outcomes (see Tab

S7 and S8 in Online Supplementary Documen

Table 2.Number of assessments of the effectiveness of community–based primary health care in impr

maternal, neonatal and child health by region and the countries with the greatest number of assess

wHO regiON Number % (N = 786)* cOuNtry Number % (N = 786)*

Africa 385 49.0% India 86 10.9

South–East Asia 224 28.5% Bangladesh 77 9.8

Americas 76 9.7% Nepal 47 6.0

Eastern Mediterranean 61 7.8% Ghana 36 4.6

Western Pacific 37 4.7% Pakistan 35 4.5

Europe 4 0.5% Uganda 34 4.3

Total 786* 100.0% Tanzania 30 3.8

Ethiopia 28 3.6

Kenya 27 3.4

Malawi 19 2.4

*The total number of countries listed here exceeds the number of assessments because some assessments were

tiple countries.

Table 3.Implementers of projects for improving MNCH

Number % (N = 700)

Facilitating and/or stakeholder organization:

State or national government 424 60.6

International NGO 281 40.1

Private organization/university/research organization 254 36.3

Local government 243 34.7

Local NGO 125 17.9

National NGO 85 12.1

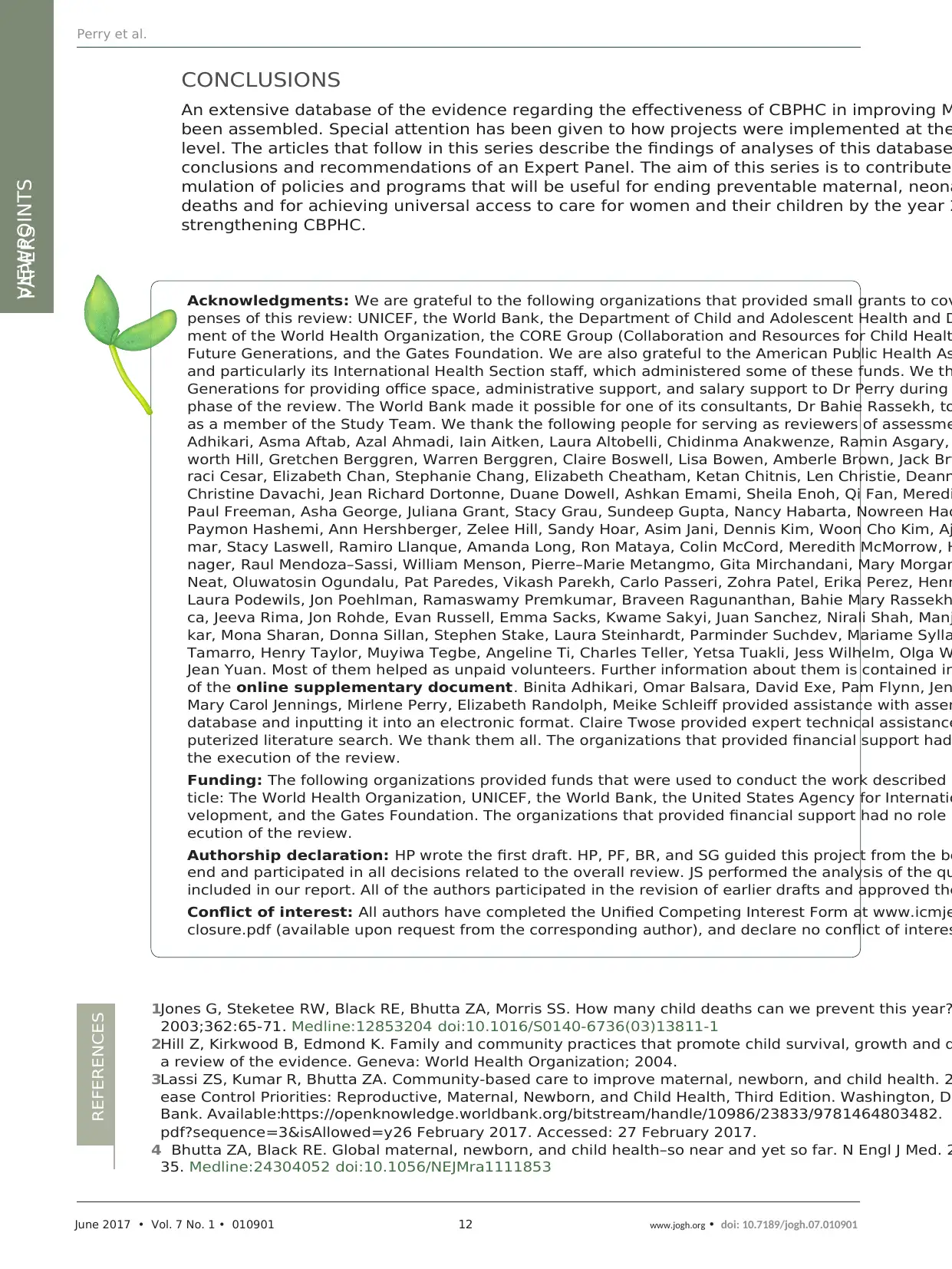

Faith–based organization 27 3.9