Transformational Leadership in Nursing: A Comprehensive Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/03/17

|10

|7653

|86

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a concept analysis of transformational leadership (TFL) within the nursing context, aiming to clarify its meaning and usage to improve patient outcomes and healthcare reform. The study, based on Walker and Avant’s concept analysis method, examines the existing literature from PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychINFO. It proposes a new operational definition for TFL, highlighting its role as both a leadership style and a set of teachable competencies. The analysis identifies defining attributes, model cases, and the influence of TFL on organizational culture and patient outcomes. The research underscores the importance of TFL in developing cultures of safety and improving healthcare performance, while also pointing out the need for further research to strengthen empirical referents and validate subscale measures. The report concludes that while TFL has been linked to high-performing teams and improved patient care, its mechanisms of influence remain unclear, suggesting that further research is warranted to clarify these connections.

CONCEPT ANALYSIS

Transformational leadership in nursing: a concept analysis

Shelly A. Fischer

Accepted for publication 5 May 2016

Correspondence to S.A. Fischer:

e-mail: sfische1@uwyo.edu

Shelly A. Fischer PhD RN NEA-BC FACHE

Assistant Professor

Fay W. Whitney School of Nursing,

University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming,

USA

F I S C H E R S . A .( 2 0 1 6 )Transformationalleadership in nursing:a concept analysis.

Journal of Advanced Nursing 72(11), 2644–2653. doi: 10.1111/jan.13049

Abstract

Aim. To analyse the concept of transformational leadership in the nursing context.

Background.Tasked with improving patientoutcomes while decreasing the costof

care provision,nurses need strategies for implementing reform in health care and one

promising strategy is transformational leadership. Exploration and greater

understanding oftransformationalleadership and the potentialit holds is integralto

performance improvement and patient safety.

Design.Concept analysis using Walker and Avant’s (2005) concept analysis method.

Data sources.PubMed, CINAHL and PsychINFO.

Methods.This report draws on extant literatureon transformationalleadership,

management,and nursing to effectively analyze the conceptof transformational

leadership in the nursing context.

Implicationsfor nursing.This report proposesa new operationaldefinition for

transformationalleadership and identifies modelcases and defining attributes that are

specificto the nursing context. The influenceof transformationalleadership on

organizationalculture and patientoutcomesis evident.Of particularinterestis the

finding that transformationalleadershipcan be defined as a set of teachable

competencies.However, the mechanism by which transformationalleadership

influences patient outcomes remains unclear.

Conclusion.Transformationalleadership in nursing hasbeen associated with high-

performing teams and improved patient care, but rarely has it been considered as a set

of competencies that can be taught.Also, further research is warranted to strengthen

empiricalreferents;this can be done by improving the operationaldefinition,reducing

ambiguity in key constructsand exploring the specific mechanismsby which

transformationalleadershipinfluenceshealthcareoutcomesto validate subscale

measures.

Keywords:concept analysis,healthcare reform,leadership,management,nursing,pa-

tient safety, performance improvement, practice environment, transformational

Introduction

Awarenessof undesirable patientsafety outcomesbecame

widespread in theUSA when the Instituteof Medicine

(Kohn et al.2000) reported that preventable medicalerror

led to nearly 100,000 deathsin the USA every year;

recently,James’(2013) analysis of the same data increased

the estimateto nearly 400,000 preventableUSA deaths

annually. While patient safety data from other countries are

2644 © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Transformational leadership in nursing: a concept analysis

Shelly A. Fischer

Accepted for publication 5 May 2016

Correspondence to S.A. Fischer:

e-mail: sfische1@uwyo.edu

Shelly A. Fischer PhD RN NEA-BC FACHE

Assistant Professor

Fay W. Whitney School of Nursing,

University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming,

USA

F I S C H E R S . A .( 2 0 1 6 )Transformationalleadership in nursing:a concept analysis.

Journal of Advanced Nursing 72(11), 2644–2653. doi: 10.1111/jan.13049

Abstract

Aim. To analyse the concept of transformational leadership in the nursing context.

Background.Tasked with improving patientoutcomes while decreasing the costof

care provision,nurses need strategies for implementing reform in health care and one

promising strategy is transformational leadership. Exploration and greater

understanding oftransformationalleadership and the potentialit holds is integralto

performance improvement and patient safety.

Design.Concept analysis using Walker and Avant’s (2005) concept analysis method.

Data sources.PubMed, CINAHL and PsychINFO.

Methods.This report draws on extant literatureon transformationalleadership,

management,and nursing to effectively analyze the conceptof transformational

leadership in the nursing context.

Implicationsfor nursing.This report proposesa new operationaldefinition for

transformationalleadership and identifies modelcases and defining attributes that are

specificto the nursing context. The influenceof transformationalleadership on

organizationalculture and patientoutcomesis evident.Of particularinterestis the

finding that transformationalleadershipcan be defined as a set of teachable

competencies.However, the mechanism by which transformationalleadership

influences patient outcomes remains unclear.

Conclusion.Transformationalleadership in nursing hasbeen associated with high-

performing teams and improved patient care, but rarely has it been considered as a set

of competencies that can be taught.Also, further research is warranted to strengthen

empiricalreferents;this can be done by improving the operationaldefinition,reducing

ambiguity in key constructsand exploring the specific mechanismsby which

transformationalleadershipinfluenceshealthcareoutcomesto validate subscale

measures.

Keywords:concept analysis,healthcare reform,leadership,management,nursing,pa-

tient safety, performance improvement, practice environment, transformational

Introduction

Awarenessof undesirable patientsafety outcomesbecame

widespread in theUSA when the Instituteof Medicine

(Kohn et al.2000) reported that preventable medicalerror

led to nearly 100,000 deathsin the USA every year;

recently,James’(2013) analysis of the same data increased

the estimateto nearly 400,000 preventableUSA deaths

annually. While patient safety data from other countries are

2644 © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

less available, researchers indicate that this concern is a glo-

bal one (Arulmaniet al.2007,Redwood et al.2011,Bates

2009).Public and government pressure is high for transfor-

mationalchange in health care to improve patientsafety

outcomes internationally. A prominent potentialsolution to

the patientsafety conundrum thathas emerged in recent

yearsis transformationalleadership (TFL),which encom-

passesthe leadership behavioursand characteristicsthat

positively influence organizationalperformance and patient

safety outcomes (Mullen & Kelloway 2009).While TFL is

not a universalremedy,TFL competencies can have a sali-

ent role in developing cultures of safety in the patient care

environment (Kohn et al.2000) and have been linked with

improved performance and outcomes in many measures of

healthcare performance (Howell& Avolio 1993, Wong &

Cummings 2007,Mullen & Kelloway 2009).Yet, the liter-

ature has not been clear as to how and when TFL positively

affects patientsafety outcomes in healthcare settings.This

article presentsa conceptanalysisof TFL in the nursing

context, including a discussionand applicationof the

results specific to nursing education,research and practice.

The application of TFL as a style and competencies in the

business arena is beyond the scope of this concept analysis.

Background

A concept analysisof TFL for nursing fillsan important

gap in knowledge on the theory and practice ofnursing.

According to Chinn and Kramer (2008), clarifying the

meaning ofa conceptis integralto theory development

and, subsequently,to practice and research thatis guided

and informed by it.In measuring healthcare performance,

factors associatedwith leadership styles have been

strongly linked to patientoutcomes.Among the mostuse-

ful measuresof healthcare performance are nursing satis-

faction, retention (Kleinman 2004,Casida & Pinto-Zipp

2008), patientsatisfaction (Raup 2008)and workgroup

effectiveness(Dunham-Taylor2000).Of particularimpor-

tance for healthcareperformanceand subsequentlyfor

patientoutcomes,are the wayshealthcare teamsare led.

A strong relationship has been establishedbetween

patientsafety processesand outcomeson one hand and

leadership on the other(Thompson et al.2005, Wong &

Cummings 2007). For example, the use of patient

restraintsand the occurrence ofimmobility complications

—two patientoutcomes thatare generally considered neg-

ative—areinverselyrelated to the level of relationship-

oriented leadership and nurse managers’yearsof experi-

ence (Anderson et al.2003).Much research suggeststhat

to improve patientoutcomes,we would do well to con-

sider how leadership is understoodand practiced in

healthcare contexts,particularly on nursing units.Further

research iswarranted to testtheoriesrelated to TFL and

patientcare outcomes.Conceptanalysis ofTFL is a logi-

cal first step to designing research thatmore fully assesses

the impactof TFL on patientoutcomes.

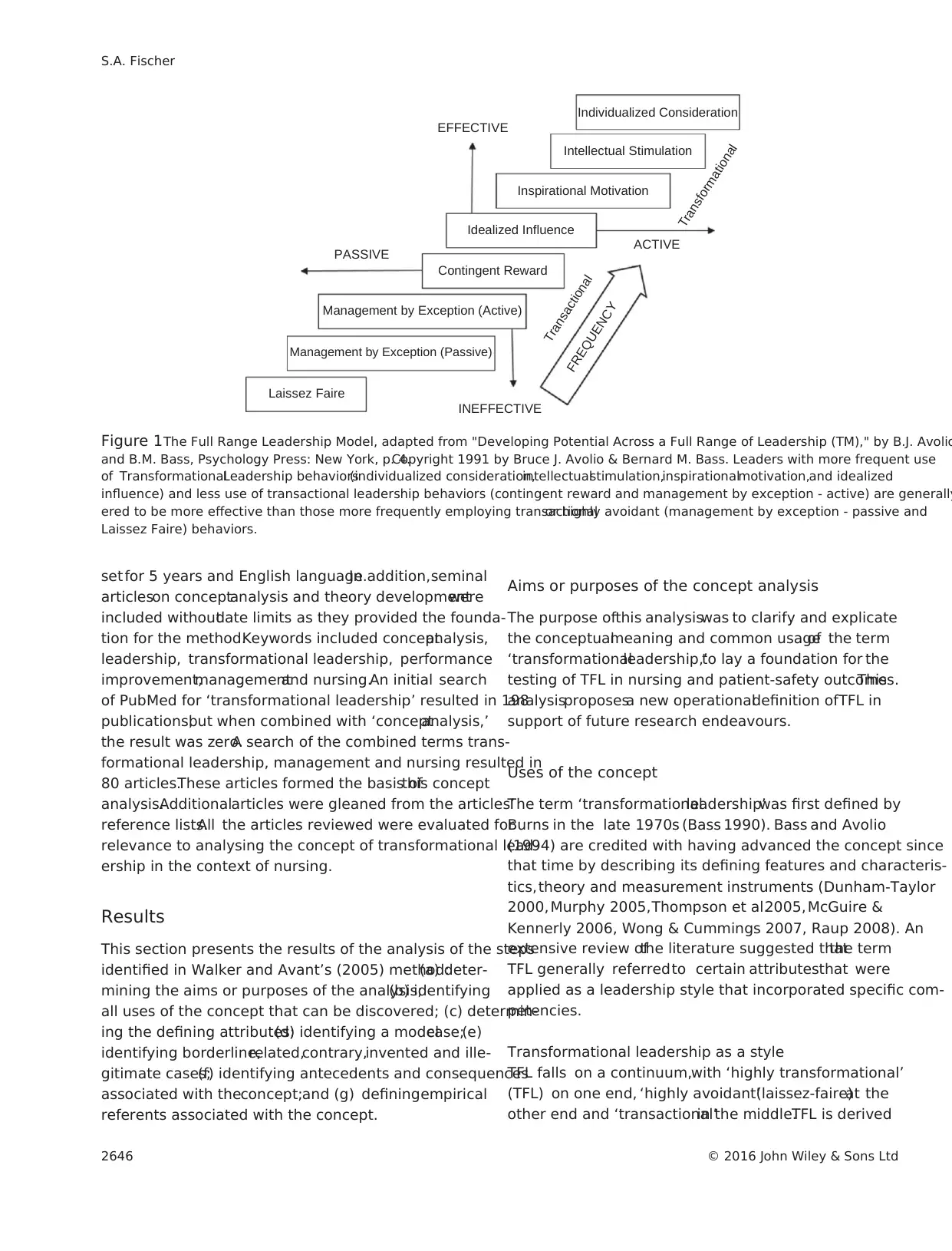

One example ofhow TFL can be tested as a conceptis

offered by Kanste et al.(2009),whose research explicates

Full-Range Leadership Theory in the contextof nursing.

Their findingsemphasize the value ofTFL in nursing in

relation to staff willingness to exert extra effort,perception

of leader effectiveness and leader job satisfaction.The Full-

Range Leadership Theorymodel, with TFL in bold, is

found in Figure 1.

Data sources

Databasessearchedfor the concept analysis of TFL

included PubMed,CINAHL and PsychINFO, with limits

Why is this research or review needed?

• Unprecedented reform isessentialto the survival of the

healthcare system and global economy.

• Healthcare reform isdependenton leaderswho think in

innovative ways and have the skills, attributes and courage

that enable them to implement rapid change.

• A full understanding ofthe conceptof transformational

leadership,including its meaning,usageand operational

definition,is essentialfor preparingcurrent and future

leaders to significantly improve the healthcare system.

What are the key findings?

• The term ‘transformational leadership’ has consistent usage

in the literature, yet it will benefit from an improved opera-

tional definition, as proposed in this report.

• Transformationalleadership is a leadership style as wellas

a set of competencies that can be taught.

• Transformational leadership is not a panacea for improving

patientoutcomes;it should be used in conjunction with

other leadership skillsto optimize the performance ofa

workgroup.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/

practice/research/education?

• This analysis creates a foundation for teaching these com-

petencies in practice and academic settings.

• The new operationaldefinition of transformationalleader-

ship should be tested and validated by expert opinion and

empirical research.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2645

JAN: CONCEPT ANALYSIS Transformational leadership

bal one (Arulmaniet al.2007,Redwood et al.2011,Bates

2009).Public and government pressure is high for transfor-

mationalchange in health care to improve patientsafety

outcomes internationally. A prominent potentialsolution to

the patientsafety conundrum thathas emerged in recent

yearsis transformationalleadership (TFL),which encom-

passesthe leadership behavioursand characteristicsthat

positively influence organizationalperformance and patient

safety outcomes (Mullen & Kelloway 2009).While TFL is

not a universalremedy,TFL competencies can have a sali-

ent role in developing cultures of safety in the patient care

environment (Kohn et al.2000) and have been linked with

improved performance and outcomes in many measures of

healthcare performance (Howell& Avolio 1993, Wong &

Cummings 2007,Mullen & Kelloway 2009).Yet, the liter-

ature has not been clear as to how and when TFL positively

affects patientsafety outcomes in healthcare settings.This

article presentsa conceptanalysisof TFL in the nursing

context, including a discussionand applicationof the

results specific to nursing education,research and practice.

The application of TFL as a style and competencies in the

business arena is beyond the scope of this concept analysis.

Background

A concept analysisof TFL for nursing fillsan important

gap in knowledge on the theory and practice ofnursing.

According to Chinn and Kramer (2008), clarifying the

meaning ofa conceptis integralto theory development

and, subsequently,to practice and research thatis guided

and informed by it.In measuring healthcare performance,

factors associatedwith leadership styles have been

strongly linked to patientoutcomes.Among the mostuse-

ful measuresof healthcare performance are nursing satis-

faction, retention (Kleinman 2004,Casida & Pinto-Zipp

2008), patientsatisfaction (Raup 2008)and workgroup

effectiveness(Dunham-Taylor2000).Of particularimpor-

tance for healthcareperformanceand subsequentlyfor

patientoutcomes,are the wayshealthcare teamsare led.

A strong relationship has been establishedbetween

patientsafety processesand outcomeson one hand and

leadership on the other(Thompson et al.2005, Wong &

Cummings 2007). For example, the use of patient

restraintsand the occurrence ofimmobility complications

—two patientoutcomes thatare generally considered neg-

ative—areinverselyrelated to the level of relationship-

oriented leadership and nurse managers’yearsof experi-

ence (Anderson et al.2003).Much research suggeststhat

to improve patientoutcomes,we would do well to con-

sider how leadership is understoodand practiced in

healthcare contexts,particularly on nursing units.Further

research iswarranted to testtheoriesrelated to TFL and

patientcare outcomes.Conceptanalysis ofTFL is a logi-

cal first step to designing research thatmore fully assesses

the impactof TFL on patientoutcomes.

One example ofhow TFL can be tested as a conceptis

offered by Kanste et al.(2009),whose research explicates

Full-Range Leadership Theory in the contextof nursing.

Their findingsemphasize the value ofTFL in nursing in

relation to staff willingness to exert extra effort,perception

of leader effectiveness and leader job satisfaction.The Full-

Range Leadership Theorymodel, with TFL in bold, is

found in Figure 1.

Data sources

Databasessearchedfor the concept analysis of TFL

included PubMed,CINAHL and PsychINFO, with limits

Why is this research or review needed?

• Unprecedented reform isessentialto the survival of the

healthcare system and global economy.

• Healthcare reform isdependenton leaderswho think in

innovative ways and have the skills, attributes and courage

that enable them to implement rapid change.

• A full understanding ofthe conceptof transformational

leadership,including its meaning,usageand operational

definition,is essentialfor preparingcurrent and future

leaders to significantly improve the healthcare system.

What are the key findings?

• The term ‘transformational leadership’ has consistent usage

in the literature, yet it will benefit from an improved opera-

tional definition, as proposed in this report.

• Transformationalleadership is a leadership style as wellas

a set of competencies that can be taught.

• Transformational leadership is not a panacea for improving

patientoutcomes;it should be used in conjunction with

other leadership skillsto optimize the performance ofa

workgroup.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/

practice/research/education?

• This analysis creates a foundation for teaching these com-

petencies in practice and academic settings.

• The new operationaldefinition of transformationalleader-

ship should be tested and validated by expert opinion and

empirical research.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2645

JAN: CONCEPT ANALYSIS Transformational leadership

set for 5 years and English language.In addition,seminal

articleson conceptanalysis and theory developmentwere

included withoutdate limits as they provided the founda-

tion for the method.Keywords included conceptanalysis,

leadership, transformational leadership, performance

improvement,managementand nursing.An initial search

of PubMed for ‘transformational leadership’ resulted in 198

publications,but when combined with ‘conceptanalysis,’

the result was zero.A search of the combined terms trans-

formational leadership, management and nursing resulted in

80 articles.These articles formed the basis ofthis concept

analysis.Additionalarticles were gleaned from the articles’

reference lists.All the articles reviewed were evaluated for

relevance to analysing the concept of transformational lead-

ership in the context of nursing.

Results

This section presents the results of the analysis of the steps

identified in Walker and Avant’s (2005) method:(a) deter-

mining the aims or purposes of the analysis;(b) identifying

all uses of the concept that can be discovered; (c) determin-

ing the defining attributes;(d) identifying a modelcase;(e)

identifying borderline,related,contrary,invented and ille-

gitimate cases;(f) identifying antecedents and consequences

associated with theconcept;and (g) definingempirical

referents associated with the concept.

Aims or purposes of the concept analysis

The purpose ofthis analysiswas to clarify and explicate

the conceptualmeaning and common usageof the term

‘transformationalleadership,’to lay a foundation for the

testing of TFL in nursing and patient-safety outcomes.This

analysisproposesa new operationaldefinition ofTFL in

support of future research endeavours.

Uses of the concept

The term ‘transformationalleadership’was first defined by

Burns in the late 1970s (Bass 1990). Bass and Avolio

(1994) are credited with having advanced the concept since

that time by describing its defining features and characteris-

tics,theory and measurement instruments (Dunham-Taylor

2000, Murphy 2005,Thompson et al.2005, McGuire &

Kennerly 2006, Wong & Cummings 2007, Raup 2008). An

extensive review ofthe literature suggested thatthe term

TFL generally referredto certain attributesthat were

applied as a leadership style that incorporated specific com-

petencies.

Transformational leadership as a style

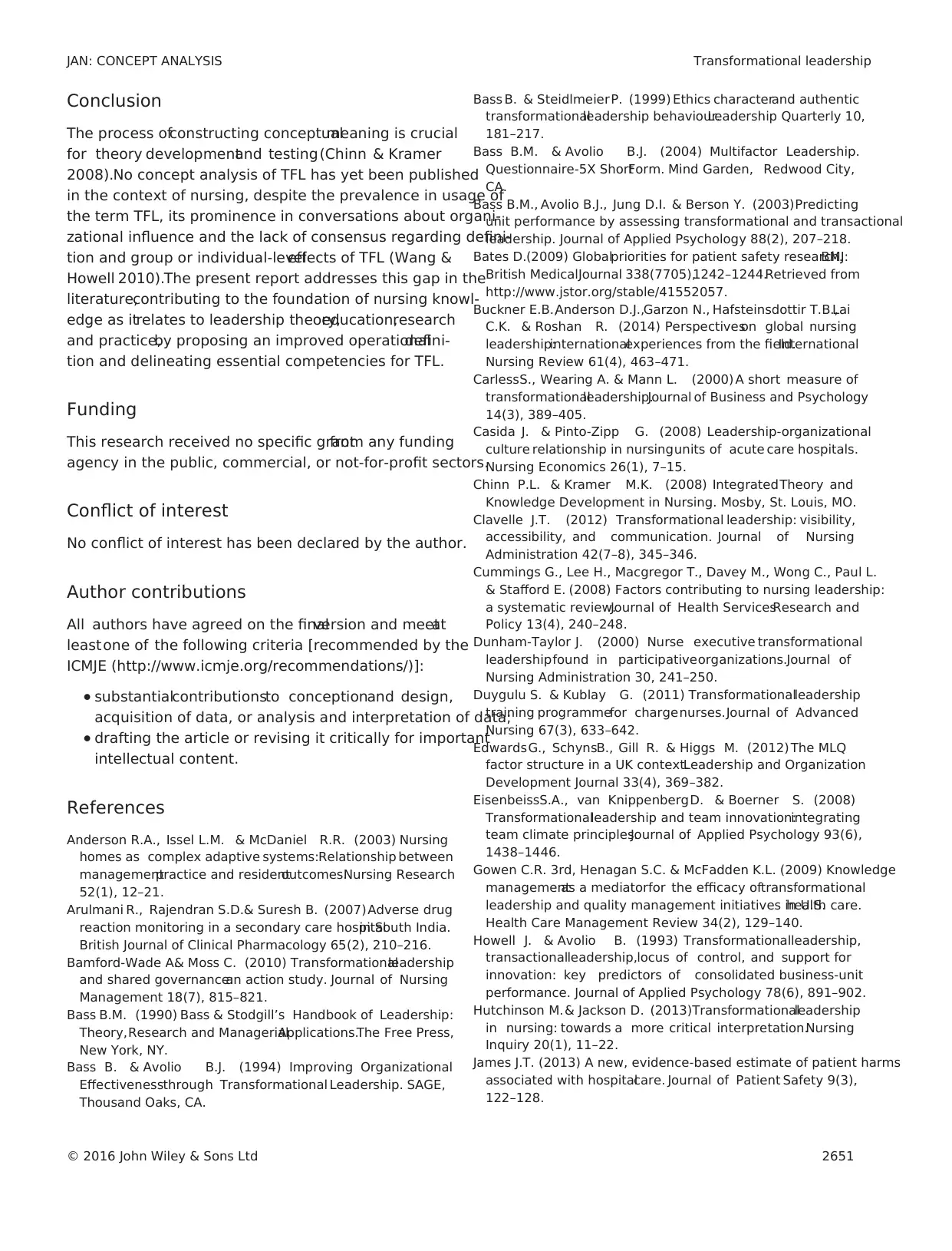

TFL falls on a continuum,with ‘highly transformational’

(TFL) on one end, ‘highly avoidant’(laissez-faire)at the

other end and ‘transactional’in the middle.TFL is derived

EFFECTIVE

PASSIVE

FREQUENCY

Transactional

Transformational

ACTIVE

INEFFECTIVE

Individualized Consideration

Intellectual Stimulation

Inspirational Motivation

Idealized Influence

Contingent Reward

Management by Exception (Active)

Management by Exception (Passive)

Laissez Faire

Figure 1The Full Range Leadership Model, adapted from "Developing Potential Across a Full Range of Leadership (TM)," by B.J. Avolio

and B.M. Bass, Psychology Press: New York, p. 4.Copyright 1991 by Bruce J. Avolio & Bernard M. Bass. Leaders with more frequent use

of TransformationalLeadership behaviors(individualized consideration,intellectualstimulation,inspirationalmotivation,and idealized

influence) and less use of transactional leadership behaviors (contingent reward and management by exception - active) are generally

ered to be more effective than those more frequently employing transactionalor highly avoidant (management by exception - passive and

Laissez Faire) behaviors.

2646 © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

S.A. Fischer

articleson conceptanalysis and theory developmentwere

included withoutdate limits as they provided the founda-

tion for the method.Keywords included conceptanalysis,

leadership, transformational leadership, performance

improvement,managementand nursing.An initial search

of PubMed for ‘transformational leadership’ resulted in 198

publications,but when combined with ‘conceptanalysis,’

the result was zero.A search of the combined terms trans-

formational leadership, management and nursing resulted in

80 articles.These articles formed the basis ofthis concept

analysis.Additionalarticles were gleaned from the articles’

reference lists.All the articles reviewed were evaluated for

relevance to analysing the concept of transformational lead-

ership in the context of nursing.

Results

This section presents the results of the analysis of the steps

identified in Walker and Avant’s (2005) method:(a) deter-

mining the aims or purposes of the analysis;(b) identifying

all uses of the concept that can be discovered; (c) determin-

ing the defining attributes;(d) identifying a modelcase;(e)

identifying borderline,related,contrary,invented and ille-

gitimate cases;(f) identifying antecedents and consequences

associated with theconcept;and (g) definingempirical

referents associated with the concept.

Aims or purposes of the concept analysis

The purpose ofthis analysiswas to clarify and explicate

the conceptualmeaning and common usageof the term

‘transformationalleadership,’to lay a foundation for the

testing of TFL in nursing and patient-safety outcomes.This

analysisproposesa new operationaldefinition ofTFL in

support of future research endeavours.

Uses of the concept

The term ‘transformationalleadership’was first defined by

Burns in the late 1970s (Bass 1990). Bass and Avolio

(1994) are credited with having advanced the concept since

that time by describing its defining features and characteris-

tics,theory and measurement instruments (Dunham-Taylor

2000, Murphy 2005,Thompson et al.2005, McGuire &

Kennerly 2006, Wong & Cummings 2007, Raup 2008). An

extensive review ofthe literature suggested thatthe term

TFL generally referredto certain attributesthat were

applied as a leadership style that incorporated specific com-

petencies.

Transformational leadership as a style

TFL falls on a continuum,with ‘highly transformational’

(TFL) on one end, ‘highly avoidant’(laissez-faire)at the

other end and ‘transactional’in the middle.TFL is derived

EFFECTIVE

PASSIVE

FREQUENCY

Transactional

Transformational

ACTIVE

INEFFECTIVE

Individualized Consideration

Intellectual Stimulation

Inspirational Motivation

Idealized Influence

Contingent Reward

Management by Exception (Active)

Management by Exception (Passive)

Laissez Faire

Figure 1The Full Range Leadership Model, adapted from "Developing Potential Across a Full Range of Leadership (TM)," by B.J. Avolio

and B.M. Bass, Psychology Press: New York, p. 4.Copyright 1991 by Bruce J. Avolio & Bernard M. Bass. Leaders with more frequent use

of TransformationalLeadership behaviors(individualized consideration,intellectualstimulation,inspirationalmotivation,and idealized

influence) and less use of transactional leadership behaviors (contingent reward and management by exception - active) are generally

ered to be more effective than those more frequently employing transactionalor highly avoidant (management by exception - passive and

Laissez Faire) behaviors.

2646 © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

S.A. Fischer

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

from the Full Range Leadership Theory (Bass& Avolio

1994)and in it, followerstend to characterize leadersas

being ‘charismatic,visionary and loyal’(van Oyen Force

2005, p.338). TFL is a ‘high impact’(Shirey 2006, p. 282)

style that typically empowerssubordinates,resultingin

greater job satisfaction and sense ofautonomy (Kleinman

2004). Another term commonly associated with TFL is

‘participative’leadership(Casida & Pinto-Zipp 2008).

Other descriptors for transformationalleaders include ‘au-

thentic, genuine, trustworthy, reliable and believable’

(Shirey 2006, p. 280).

Transformational leadership as a set of competencies

Substantialevidence suggests thattransformationalleaders

are not born, but developed.Key competenciescan be

achievedthrough training, education and professional

development(Welford 2002,Murphy 2005, McGuire &

Kennerly 2006).Thompson (2012)identified specific skills

as essentialfor the transformationalleader to master,such

as learning to work with othersin an empowering way,

facilitating growth and learning ofstaff, translating evi-

dence into practiceand practiceinto evidence,critical

reflection and communication,problem-solving and deci-

sion-making.

Defining attributes

The defining attributes and behaviours associated with TFL

were identified by Bass and Avolio (1994)as the ‘five I’s’:

idealized influence (attributed), idealized influence

(behavioural),inspirationalmotivation,intellectualstimula-

tion and individualconsideration.In anothersynthesisof

TFL’s defining attributes,Kouzes and Posner (2008) identi-

fied the transformationalleader’sfive habitualpractices:

modelling the way,inspiring a shared vision,challenging

the process,enabling othersto act and encouraging the

heart.These authors were frequently cited for their work

towards describing and measuring traits, characteristics and

behaviourstypical of the transformationalleader. Still,

additionalwork on the measurementof transformational

leadership may need to be done,given the criticism levelled

towards the currentdefinition and constructsrelated to

transformational leadership.

Critics of TFL measuresdisagree with the notion that

attributes of TFL were well-defined or described.One such

author, Yukl (1999), stated thatconceptualweaknesses

keep instrumentsfrom effectively measuring ordescribing

leadership.The most fundamentalweaknessidentified is

that of ‘ambiguous constructs’(Yukl 1999).This criticism

is supported by the facts thatno conceptanalysis ofTFL

has yet been published and thattheredoes seem to be

ambiguity in the defining attributes ofTFL. For example,

previouswork has not clearly established how attributes

were identified,nor is there theoreticalrationale for differ-

entiating among them.

Additional criticismsby Yukl (1999) includethe con-

tention thatthe processesinherentto TFL have not been

sufficientlydescribed,limiting conditionshave not been

adequately specified and behaviours known to be essential

to certain stylesof leadership have been omitted.Similar

concerns regarding TFL are voiced by Hutchinson

(Hutchinson & Jackson 2013) and by Eisenbeisset al.

(2008),who identify and substantiate four fatalflaws with

TFL, going so far as to recommend abandonment of prior

definitions ofthe conceptand ‘starting over’with concep-

tual clarification, operational definition, theory development

and empiricalreferentdesign and testing.The fatal flaws

inherentto the TFL concept and measures,according to

Eisenbeiss (2008), include conceptual ambiguity, inadequate

causalmodelling to support justifiable and credible antece-

dents, lacking operationaldefinition (distinctfrom out-

comes and consequencesof the leadershipstyle) and

empirical referents that are invalid due to lacking specificity

and distinction from otheraspectsor typesof leadership.

According to the above-referenced critics,lack of concep-

tual clarity weakensthe foundation fordefinition,theory

development and operational measure design and testing.

Model case

An exemplar ofTFL is a leader who demonstrates caring

about his or her followers and passion about the mission of

the group.The leader’s followers feelwarmth and security

in their relationships with their leader (attributed idealized

influence),as wellas trust.The leader models ethicalbeha-

viours and is known for honesty and integrity (behavioural

idealized influence).He or she prioritizes personaland pro-

fessionaldevelopmentfor him- or herselfand followers.

Decisions are value-based, which motivates and inspires fol-

lowers to excel (inspirational motivation).

Considerthe hypotheticalcaseof Kathy, a model for

TFL. Kathy was a Master’s prepared nurseleaderwho

had benefitted greatly from innate attributesof charisma

and visionary thinking,as well as from a mentor who

taughther the foundationalcompetenciesof TFL. Kathy

began as the new Director of Nursing for a recently

opened skilled nursingfacility. At the time she started

work at the facility,members ofthe nursing staff,having

suffered a very difficultagency start-up underthe direc-

tion of an autocratic leader,were confused,yet fearfulto

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2647

JAN: CONCEPT ANALYSIS Transformational leadership

1994)and in it, followerstend to characterize leadersas

being ‘charismatic,visionary and loyal’(van Oyen Force

2005, p.338). TFL is a ‘high impact’(Shirey 2006, p. 282)

style that typically empowerssubordinates,resultingin

greater job satisfaction and sense ofautonomy (Kleinman

2004). Another term commonly associated with TFL is

‘participative’leadership(Casida & Pinto-Zipp 2008).

Other descriptors for transformationalleaders include ‘au-

thentic, genuine, trustworthy, reliable and believable’

(Shirey 2006, p. 280).

Transformational leadership as a set of competencies

Substantialevidence suggests thattransformationalleaders

are not born, but developed.Key competenciescan be

achievedthrough training, education and professional

development(Welford 2002,Murphy 2005, McGuire &

Kennerly 2006).Thompson (2012)identified specific skills

as essentialfor the transformationalleader to master,such

as learning to work with othersin an empowering way,

facilitating growth and learning ofstaff, translating evi-

dence into practiceand practiceinto evidence,critical

reflection and communication,problem-solving and deci-

sion-making.

Defining attributes

The defining attributes and behaviours associated with TFL

were identified by Bass and Avolio (1994)as the ‘five I’s’:

idealized influence (attributed), idealized influence

(behavioural),inspirationalmotivation,intellectualstimula-

tion and individualconsideration.In anothersynthesisof

TFL’s defining attributes,Kouzes and Posner (2008) identi-

fied the transformationalleader’sfive habitualpractices:

modelling the way,inspiring a shared vision,challenging

the process,enabling othersto act and encouraging the

heart.These authors were frequently cited for their work

towards describing and measuring traits, characteristics and

behaviourstypical of the transformationalleader. Still,

additionalwork on the measurementof transformational

leadership may need to be done,given the criticism levelled

towards the currentdefinition and constructsrelated to

transformational leadership.

Critics of TFL measuresdisagree with the notion that

attributes of TFL were well-defined or described.One such

author, Yukl (1999), stated thatconceptualweaknesses

keep instrumentsfrom effectively measuring ordescribing

leadership.The most fundamentalweaknessidentified is

that of ‘ambiguous constructs’(Yukl 1999).This criticism

is supported by the facts thatno conceptanalysis ofTFL

has yet been published and thattheredoes seem to be

ambiguity in the defining attributes ofTFL. For example,

previouswork has not clearly established how attributes

were identified,nor is there theoreticalrationale for differ-

entiating among them.

Additional criticismsby Yukl (1999) includethe con-

tention thatthe processesinherentto TFL have not been

sufficientlydescribed,limiting conditionshave not been

adequately specified and behaviours known to be essential

to certain stylesof leadership have been omitted.Similar

concerns regarding TFL are voiced by Hutchinson

(Hutchinson & Jackson 2013) and by Eisenbeisset al.

(2008),who identify and substantiate four fatalflaws with

TFL, going so far as to recommend abandonment of prior

definitions ofthe conceptand ‘starting over’with concep-

tual clarification, operational definition, theory development

and empiricalreferentdesign and testing.The fatal flaws

inherentto the TFL concept and measures,according to

Eisenbeiss (2008), include conceptual ambiguity, inadequate

causalmodelling to support justifiable and credible antece-

dents, lacking operationaldefinition (distinctfrom out-

comes and consequencesof the leadershipstyle) and

empirical referents that are invalid due to lacking specificity

and distinction from otheraspectsor typesof leadership.

According to the above-referenced critics,lack of concep-

tual clarity weakensthe foundation fordefinition,theory

development and operational measure design and testing.

Model case

An exemplar ofTFL is a leader who demonstrates caring

about his or her followers and passion about the mission of

the group.The leader’s followers feelwarmth and security

in their relationships with their leader (attributed idealized

influence),as wellas trust.The leader models ethicalbeha-

viours and is known for honesty and integrity (behavioural

idealized influence).He or she prioritizes personaland pro-

fessionaldevelopmentfor him- or herselfand followers.

Decisions are value-based, which motivates and inspires fol-

lowers to excel (inspirational motivation).

Considerthe hypotheticalcaseof Kathy, a model for

TFL. Kathy was a Master’s prepared nurseleaderwho

had benefitted greatly from innate attributesof charisma

and visionary thinking,as well as from a mentor who

taughther the foundationalcompetenciesof TFL. Kathy

began as the new Director of Nursing for a recently

opened skilled nursingfacility. At the time she started

work at the facility,members ofthe nursing staff,having

suffered a very difficultagency start-up underthe direc-

tion of an autocratic leader,were confused,yet fearfulto

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2647

JAN: CONCEPT ANALYSIS Transformational leadership

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

speak of problemsor requestclarification.As a result,

the care they delivered wasdisorganized and proneto

error. Growth in occupancy wasslow and businesssuf-

fered.Kathy gathered the staffand quickly sized up the

problem (emotionalintelligence).She knew that,without

intervention,this nursing facility would continue to pro-

vide marginalcare,if it even keptits doors open.Kathy

already knew what she hoped for (visionary):a place

where people who needed supportin everyday tasksfelt

cared for. She began to meetregularly with staffas a

group to lay the foundation for team building (collabora-

tion) and with individuals to getto know them and their

personalinterestsand to develop trust(communication).

Kathy used humour,passion and her warm smile and

sparkling eyes to help even the mostfearfuland hurtsee

possibilities(enthusiasm).Soon, hallwayswere filled with

laughteramong staffand residentsas daily tasksbecame

organized and routine.In meetings,Kathy would align

requests for projectsupportwith the personalinterests of

the staff,create goalsto be achieved and assure thatthe

staff had what they needed to complete the project(em-

powerment).Staff membersnew to project management

were gently guided and coachedto achieve goals and

learn skills in the process (mentoring).Staff became confi-

dent, competent,happy providerswho promoted ‘their’

facility at every turn. The reputation of the facility

became justwhat Kathy had hoped forand in no time,

was filled to capacity with a waiting list and became

financially sound with ready reserves.Through the use of

TFL, Kathy successfullytransformedthe organization,

resulting in greatbenefitto the agency,staff and most

importantly its stakeholders,the patients and families.

Borderline, related, contrary, invented and illegitimate

cases

A concept analysis can be further developed by contrasting

the conceptbeing analysed with cases thatare borderline,

related,contrary,invented and/or illegitimate (Walker and

Avant (2005). The literature search yielded examples for all

case types, except for the invented case.

Borderline and related cases

An example of a borderline or related case is aesthetic lead-

ership (Mannix et al.2015).Like TFL, this is a ‘follower-

oriented’leadership modelthat is characterized by vision-

ary, action-orientedleadershipcharacteristicsand beha-

viours.However,whereas TFL emerges from the attributes

and behaviours ofthe leader,aesthetic leadership emerges

exclusively from the perceptionsof the follower.Another

related leadership modelis that of congruentleadership

(Mannix et al. 2015),which is associated with the Situa-

tionalLeadership theory.Congruent leadership is like TFL

in that both involve modifyingleadership behaviourto

accommodate and inspire the group at hand; however, con-

gruentleadership does notdrive change in followers,nor

does it encourage innovation and creativity,both of which

are key characteristics of TFL.

Contrary cases

In addition to noting borderline and related cases, contrast-

ing the conceptbeing analysed with contrary cases further

explicatesthe concept.TFL can be contrasted with other

typesof leadership,such as transactionalleadership and

laissez-faireleadership,as well as with trait theory and

pseudo-transformational leadership.

Transactionalleadership is characterized by active man-

agementby exception,passive managementby exception

and the use of contingent rewards. Active and passive man-

agementby exception are defined as leadership behaviours

that are reactivewhen mistakesare made or thingsgo

wrong (Kanste et al.2009),in contrastwith TFL’s proac-

tive, preventive approach. Contingent rewards represent the

recognition offered to a follower following the achievement

of a specific goal,a sort of economic exchange.Several

studies (Kleinman 2004, Raup 2008, van Oyen Force 2005)

show a significantrelationship between contingentreward

leadership behavioursand staff RN job satisfaction and

retention,although someresearchers(Murphy 2005) are

critical of transactionalleadership,positing thatthis style

‘lacksvision for the future and endorsesonly changesof

smallmagnitude thatare predicated on policy and proce-

dure rather than organizationalor cultural change’(p.

130). By contrast, TFL is generally promoted in the nursing

contextfor its encouragementof behavioursthat inspire,

engageand motivatefollowers to completelytransform

staid organizationalprocesses and culture (Suliman 2009).

Effectiveleadersmay demonstrateboth transformational

and transactionalleadership characteristics (Lindholm et al.

2000, Bass et al. 2003). Some will say that the group needs

and the situation at hand should dictate the leadership style

used (Kleinman 2004), while others have identified relation-

ship between leader and follower, as well as tasks and goals

established as determinants of the most effective leadership

approach (Murphy2005). TFL does not substitutefor

transactional leadership, but rather complements and poten-

tiates it (Murphy 2005) by assuring that both management

and leadership functions are appropriately tended.

Another contrary leadership style mentioned above,lais-

sez-faire leadership,is characterized by behaviours that are

2648 © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

S.A. Fischer

the care they delivered wasdisorganized and proneto

error. Growth in occupancy wasslow and businesssuf-

fered.Kathy gathered the staffand quickly sized up the

problem (emotionalintelligence).She knew that,without

intervention,this nursing facility would continue to pro-

vide marginalcare,if it even keptits doors open.Kathy

already knew what she hoped for (visionary):a place

where people who needed supportin everyday tasksfelt

cared for. She began to meetregularly with staffas a

group to lay the foundation for team building (collabora-

tion) and with individuals to getto know them and their

personalinterestsand to develop trust(communication).

Kathy used humour,passion and her warm smile and

sparkling eyes to help even the mostfearfuland hurtsee

possibilities(enthusiasm).Soon, hallwayswere filled with

laughteramong staffand residentsas daily tasksbecame

organized and routine.In meetings,Kathy would align

requests for projectsupportwith the personalinterests of

the staff,create goalsto be achieved and assure thatthe

staff had what they needed to complete the project(em-

powerment).Staff membersnew to project management

were gently guided and coachedto achieve goals and

learn skills in the process (mentoring).Staff became confi-

dent, competent,happy providerswho promoted ‘their’

facility at every turn. The reputation of the facility

became justwhat Kathy had hoped forand in no time,

was filled to capacity with a waiting list and became

financially sound with ready reserves.Through the use of

TFL, Kathy successfullytransformedthe organization,

resulting in greatbenefitto the agency,staff and most

importantly its stakeholders,the patients and families.

Borderline, related, contrary, invented and illegitimate

cases

A concept analysis can be further developed by contrasting

the conceptbeing analysed with cases thatare borderline,

related,contrary,invented and/or illegitimate (Walker and

Avant (2005). The literature search yielded examples for all

case types, except for the invented case.

Borderline and related cases

An example of a borderline or related case is aesthetic lead-

ership (Mannix et al.2015).Like TFL, this is a ‘follower-

oriented’leadership modelthat is characterized by vision-

ary, action-orientedleadershipcharacteristicsand beha-

viours.However,whereas TFL emerges from the attributes

and behaviours ofthe leader,aesthetic leadership emerges

exclusively from the perceptionsof the follower.Another

related leadership modelis that of congruentleadership

(Mannix et al. 2015),which is associated with the Situa-

tionalLeadership theory.Congruent leadership is like TFL

in that both involve modifyingleadership behaviourto

accommodate and inspire the group at hand; however, con-

gruentleadership does notdrive change in followers,nor

does it encourage innovation and creativity,both of which

are key characteristics of TFL.

Contrary cases

In addition to noting borderline and related cases, contrast-

ing the conceptbeing analysed with contrary cases further

explicatesthe concept.TFL can be contrasted with other

typesof leadership,such as transactionalleadership and

laissez-faireleadership,as well as with trait theory and

pseudo-transformational leadership.

Transactionalleadership is characterized by active man-

agementby exception,passive managementby exception

and the use of contingent rewards. Active and passive man-

agementby exception are defined as leadership behaviours

that are reactivewhen mistakesare made or thingsgo

wrong (Kanste et al.2009),in contrastwith TFL’s proac-

tive, preventive approach. Contingent rewards represent the

recognition offered to a follower following the achievement

of a specific goal,a sort of economic exchange.Several

studies (Kleinman 2004, Raup 2008, van Oyen Force 2005)

show a significantrelationship between contingentreward

leadership behavioursand staff RN job satisfaction and

retention,although someresearchers(Murphy 2005) are

critical of transactionalleadership,positing thatthis style

‘lacksvision for the future and endorsesonly changesof

smallmagnitude thatare predicated on policy and proce-

dure rather than organizationalor cultural change’(p.

130). By contrast, TFL is generally promoted in the nursing

contextfor its encouragementof behavioursthat inspire,

engageand motivatefollowers to completelytransform

staid organizationalprocesses and culture (Suliman 2009).

Effectiveleadersmay demonstrateboth transformational

and transactionalleadership characteristics (Lindholm et al.

2000, Bass et al. 2003). Some will say that the group needs

and the situation at hand should dictate the leadership style

used (Kleinman 2004), while others have identified relation-

ship between leader and follower, as well as tasks and goals

established as determinants of the most effective leadership

approach (Murphy2005). TFL does not substitutefor

transactional leadership, but rather complements and poten-

tiates it (Murphy 2005) by assuring that both management

and leadership functions are appropriately tended.

Another contrary leadership style mentioned above,lais-

sez-faire leadership,is characterized by behaviours that are

2648 © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

S.A. Fischer

true to the English translation ofthe phrase from French:

‘let it be’ (Perkel 2002). This style tends to be ‘hands off’ at

best and at its worst means having a leader who intention-

ally avoids engagement and decision-making.Levels of lais-

sez-faire characteristics and behaviours are inversely related

to willingness of staff to exert greater effort,perception of

leader effectiveness and satisfaction with the leader (Kanste

et al. 2009), contrasting theessentialeffecton followers

attributed to TFL.

On a more theoreticallevel,TFL also stands in contrast

with trait theory.While TFL aligns with Full Range and

SituationalLeadership theories,discussed above,TFL does

not comportwith trait theory’s claim thatleaders possess

inherenttraits enabling them to assume leadership roles;

trait theory further posits that,based on the identification

of certain traits,personalitiesand characteristics,one can

predict whether a person willbe a leader (Cummings et al.

2008).While trait theory holds thatleaders are born,not

made,substantialevidence exists to support TFL as a com-

petency that can be taught (Gowen et al. 2009, Duygulu &

Kublay 2011).

Illegitimate cases

Having identified borderline,related and contrarycases

associated with the concept of TFL,it is important to rec-

ognize illegitimate exemplars ofTFL. All transformational

leaders have in common the power to influence people,but

they do not universally possess good intentions (Hutchinson

& Jackson 2013,Tourish 2013).Cult leaders like Charles

Manson or Jim Jones are illegitimate cases of TFL.Differ-

entiating illegitimate cases of TFL is important for guarding

against inadvertent development of leaders who do not pri-

oritize ethicalintention and good faith efforts in their lead-

ership practice.

Another example of an illegitimate case of TFL is that of

Pseudo-TransformationalLeadership.First identified by

Bass and Steidlmeier (1999),this leadership style is charac-

terized by many of the same traits as TFL,but the leader’s

intentions emerge from self-interestand unethicalmotives.

The capacityto influence others, when undergirded by

malevolence,becomesmanipulativerather than inspira-

tional. The magnitude ofunethicalintentand severity of

impact on followers serveto define Pseudo-Transforma-

tional Leadership as an illegitimate example of TFL.

While substantialevidencedemonstratesthe strengths

and positive influencesof TFL on the work environment,

culture, performanceand outcomes,many authors are

quick to caution that one should not conclude that TFL is

a panacea.Welford (2002) emphasizesthat despitethe

value of TFL as a style,no one leadership style is effective

in all situations.This is consistentwith the view of Fie-

dler,who for this reason developed the SituationalLeader-

ship theory (Murphy 2005), described above.Lindholm

et al. (2000)also notesthat the mosteffective leadership

profile is one thatcan be adapted to differentsituations,

as does Jones (2006).

Antecedents and consequences

Despite the extensive research related to TFL,few antece-

dents have yet been proposed:leader identity (Johnson

et al. 2012),emotionalintelligence and socialskills (Tycz-

kowskiet al.2015).However,the competencies considered

essentialto TFL could be construed as antecedents,includ-

ing communication, collaboration, coaching skills and men-

toring skills(O’Brien et al.2008, Clavelle 2012,Buckner

et al. 2014).Most research related to antecedents suggests

that further study is warranted.Much more attention has

been paid to the consequences or outcomes of TFL.

In terms of consequences,TFL is known to have signifi-

cant effects on followers,organizations and leaders them-

selves.Most notably for followers,TFL has the effectof

inspiring and motivating, leading them to grow and develop

personallyand professionally(Bamford-Wade& Moss

2010).These followers tend to feelmore valued (McGuire

& Kennerly 2006) and their performance is enhanced as a

resultof increased self-efficacy and engagement(Salanova

et al.2011).This effect likely results from a greater invest-

ment in coaching and mentoring on the part of the transfor-

mational leader (Koerner & Bunkers 1992).

TFL followers and the leaders themselves enjoy multiple

benefits while the organization reaps tremendous outcomes

in loyalty and commitment from these followers.Increased

loyalty and commitmentto the organization,along with

improved job satisfaction and morale,all resultin signifi-

cant reductionsin turnover and greaterjob performance

(Leach 2005),giving the organization an overallcompeti-

tive advantage.TFL predicts performance even when per-

sonality characteristic variablesare controlled (Basset al.

2003).

Empirical referents

Severalempiricalreferents have been proposed for measur-

ing TFL. The most common instrument for measuring TFL

is the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ),devel-

oped by Bass and Avolio (2004).This 45-item,self-report

questionnaire measuresa range of leadership behaviours.

The 12 subscales of the MLQ measure each of the defining

attributes of leadership,as wellas attributes categorized as

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2649

JAN: CONCEPT ANALYSIS Transformational leadership

‘let it be’ (Perkel 2002). This style tends to be ‘hands off’ at

best and at its worst means having a leader who intention-

ally avoids engagement and decision-making.Levels of lais-

sez-faire characteristics and behaviours are inversely related

to willingness of staff to exert greater effort,perception of

leader effectiveness and satisfaction with the leader (Kanste

et al. 2009), contrasting theessentialeffecton followers

attributed to TFL.

On a more theoreticallevel,TFL also stands in contrast

with trait theory.While TFL aligns with Full Range and

SituationalLeadership theories,discussed above,TFL does

not comportwith trait theory’s claim thatleaders possess

inherenttraits enabling them to assume leadership roles;

trait theory further posits that,based on the identification

of certain traits,personalitiesand characteristics,one can

predict whether a person willbe a leader (Cummings et al.

2008).While trait theory holds thatleaders are born,not

made,substantialevidence exists to support TFL as a com-

petency that can be taught (Gowen et al. 2009, Duygulu &

Kublay 2011).

Illegitimate cases

Having identified borderline,related and contrarycases

associated with the concept of TFL,it is important to rec-

ognize illegitimate exemplars ofTFL. All transformational

leaders have in common the power to influence people,but

they do not universally possess good intentions (Hutchinson

& Jackson 2013,Tourish 2013).Cult leaders like Charles

Manson or Jim Jones are illegitimate cases of TFL.Differ-

entiating illegitimate cases of TFL is important for guarding

against inadvertent development of leaders who do not pri-

oritize ethicalintention and good faith efforts in their lead-

ership practice.

Another example of an illegitimate case of TFL is that of

Pseudo-TransformationalLeadership.First identified by

Bass and Steidlmeier (1999),this leadership style is charac-

terized by many of the same traits as TFL,but the leader’s

intentions emerge from self-interestand unethicalmotives.

The capacityto influence others, when undergirded by

malevolence,becomesmanipulativerather than inspira-

tional. The magnitude ofunethicalintentand severity of

impact on followers serveto define Pseudo-Transforma-

tional Leadership as an illegitimate example of TFL.

While substantialevidencedemonstratesthe strengths

and positive influencesof TFL on the work environment,

culture, performanceand outcomes,many authors are

quick to caution that one should not conclude that TFL is

a panacea.Welford (2002) emphasizesthat despitethe

value of TFL as a style,no one leadership style is effective

in all situations.This is consistentwith the view of Fie-

dler,who for this reason developed the SituationalLeader-

ship theory (Murphy 2005), described above.Lindholm

et al. (2000)also notesthat the mosteffective leadership

profile is one thatcan be adapted to differentsituations,

as does Jones (2006).

Antecedents and consequences

Despite the extensive research related to TFL,few antece-

dents have yet been proposed:leader identity (Johnson

et al. 2012),emotionalintelligence and socialskills (Tycz-

kowskiet al.2015).However,the competencies considered

essentialto TFL could be construed as antecedents,includ-

ing communication, collaboration, coaching skills and men-

toring skills(O’Brien et al.2008, Clavelle 2012,Buckner

et al. 2014).Most research related to antecedents suggests

that further study is warranted.Much more attention has

been paid to the consequences or outcomes of TFL.

In terms of consequences,TFL is known to have signifi-

cant effects on followers,organizations and leaders them-

selves.Most notably for followers,TFL has the effectof

inspiring and motivating, leading them to grow and develop

personallyand professionally(Bamford-Wade& Moss

2010).These followers tend to feelmore valued (McGuire

& Kennerly 2006) and their performance is enhanced as a

resultof increased self-efficacy and engagement(Salanova

et al.2011).This effect likely results from a greater invest-

ment in coaching and mentoring on the part of the transfor-

mational leader (Koerner & Bunkers 1992).

TFL followers and the leaders themselves enjoy multiple

benefits while the organization reaps tremendous outcomes

in loyalty and commitment from these followers.Increased

loyalty and commitmentto the organization,along with

improved job satisfaction and morale,all resultin signifi-

cant reductionsin turnover and greaterjob performance

(Leach 2005),giving the organization an overallcompeti-

tive advantage.TFL predicts performance even when per-

sonality characteristic variablesare controlled (Basset al.

2003).

Empirical referents

Severalempiricalreferents have been proposed for measur-

ing TFL. The most common instrument for measuring TFL

is the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ),devel-

oped by Bass and Avolio (2004).This 45-item,self-report

questionnaire measuresa range of leadership behaviours.

The 12 subscales of the MLQ measure each of the defining

attributes of leadership,as wellas attributes categorized as

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2649

JAN: CONCEPT ANALYSIS Transformational leadership

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

transactionaland laissez-faire,in addition to generalattri-

butesof extra effort, effectivenessand satisfaction.The

MLQ has been used extensively in health care and other

industries, despite ongoing challenges to its factor structure;

studies have repeatedly failed to replicate the original factor

structure (Edwards et al.2012).Less frequently used mea-

suresfor TFL include the Leadership PracticesInventory

(Kouzes & Posner 2008) and the GlobalTransformational

Leadership Scale (Carless et al.2000).All of the scales in

use have been criticized forthe ambiguity oftheir con-

structs and the high correlations among subscales (Hutchin-

son & Jackson 2013). In nursing leadership studies, the use

of the MLQ and LPI scales is allegedly suspect due to fre-

quent methodologicaldesign weaknesses(Hutchinson &

Jackson 2013).

Summary of results

This concept analysis has reviewed the established definition

of TFL, in addition to the common use of the term in busi-

ness and social/psychologicalscience theory.Severallimita-

tions and criticismsof the common usageof TFL have

emerged,primarily due to conceptualambiguity and theo-

reticalweaknesses.The concept has neither a strong opera-

tional definition, nor clearly identified underlying

constructs.Further definition of TFL and concept clarifica-

tion will benefit theory development and future research.

Discussion

The literature search for this conceptanalysis revealed an

abundance of literature related to TFL in the nursing context;

many research studies document and explore the outcomes

and importance ofthis leadership style.‘Transformational

leadership’is a term that is frequently used in nursing

research and publications and is increasingly used in verbal

communication in the health care and business setting.By

and large, researchers have accepted and put to use the work

of Bass and Avolio (Bass 1990) that specifies,differentiates

and definesthe attributes,characteristicsand behaviours

associated with TFL.Researchers consistently express that

further research is needed to more fully explicate how TFL

influences leaders, followers and outcomes.

Limitations

One of the challengesto a comprehensive conceptanaly-

sis, especially in the healthcare context,is the field’s ever-

changing landscape.The healthcare environmentis facing

such rapid change that there are ongoing shifts in meaning

and usage of existing verbiage,as new constructs and lan-

guageare created to describenew structuresand pro-

cesses.

Theoretical implications

An important theoretical implication that emerges from this

conceptanalysisis the questionable validity ofthe com-

monly used operationaldefinition ofthe term ‘transforma-

tional leadership.’TFL is definedby Bass and Avolio

(2004)as ‘a type ofleadership style thatleads to positive

changes in those who follow.’Leaderswho use this style

‘are generally energetic, enthusiastic and passionate [as well

as] . . .concerned and involved in the process [and] focused

on helping every member of the group succeed as well’(p.

25). A problem with this definition is that it defines Trans-

formationalLeadership on the basis of what it does,rather

than what it is.For a full understanding of the meaning of

the term,it is essentialto develop a definition based on the

traits and characteristics of the leader, rather than based on

the impact on followers.

Future research

Ample opportunitiesexist to develop and testleadership

models.This conceptanalysiscreatesa foundation for

future research by proposing a new definition of TFL,one

that is distinctfrom the antecedentsand consequencesof

the concept. The proposed definition is as follows:

Transformationalleadership isan integrativestyle of

leadership as wellas a setof competencies.The Transfor-

mationalLeadership style isidentified by an enthusiastic,

emotionally mature,visionary and courageous lifelong lear-

ner who inspires and motivates by empowering and devel-

oping followers. Competencies essential to the

transformational leader include emotional intelligence, com-

munication, collaboration, coaching and mentoring.

This definition identifiesthe traits,antecedentsand the

consequences of the two faces of TFL: a set of competencies

and a leadership style.

Implications for nursing practice

This concept analysis bolsters nursing theory, research, edu-

cation and practice at a time when nursing leaders are posi-

tioned to becomemore prominentplayersin healthcare

reform and policy development.A growing responsibility

for expansion of practice requires strong and effective lead-

ership skills and an understanding of transformational lead-

ership will benefit this skill development and practice.

2650 © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

S.A. Fischer

butesof extra effort, effectivenessand satisfaction.The

MLQ has been used extensively in health care and other

industries, despite ongoing challenges to its factor structure;

studies have repeatedly failed to replicate the original factor

structure (Edwards et al.2012).Less frequently used mea-

suresfor TFL include the Leadership PracticesInventory

(Kouzes & Posner 2008) and the GlobalTransformational

Leadership Scale (Carless et al.2000).All of the scales in

use have been criticized forthe ambiguity oftheir con-

structs and the high correlations among subscales (Hutchin-

son & Jackson 2013). In nursing leadership studies, the use

of the MLQ and LPI scales is allegedly suspect due to fre-

quent methodologicaldesign weaknesses(Hutchinson &

Jackson 2013).

Summary of results

This concept analysis has reviewed the established definition

of TFL, in addition to the common use of the term in busi-

ness and social/psychologicalscience theory.Severallimita-

tions and criticismsof the common usageof TFL have

emerged,primarily due to conceptualambiguity and theo-

reticalweaknesses.The concept has neither a strong opera-

tional definition, nor clearly identified underlying

constructs.Further definition of TFL and concept clarifica-

tion will benefit theory development and future research.

Discussion

The literature search for this conceptanalysis revealed an

abundance of literature related to TFL in the nursing context;

many research studies document and explore the outcomes

and importance ofthis leadership style.‘Transformational

leadership’is a term that is frequently used in nursing

research and publications and is increasingly used in verbal

communication in the health care and business setting.By

and large, researchers have accepted and put to use the work

of Bass and Avolio (Bass 1990) that specifies,differentiates

and definesthe attributes,characteristicsand behaviours

associated with TFL.Researchers consistently express that

further research is needed to more fully explicate how TFL

influences leaders, followers and outcomes.

Limitations

One of the challengesto a comprehensive conceptanaly-

sis, especially in the healthcare context,is the field’s ever-

changing landscape.The healthcare environmentis facing

such rapid change that there are ongoing shifts in meaning

and usage of existing verbiage,as new constructs and lan-

guageare created to describenew structuresand pro-

cesses.

Theoretical implications

An important theoretical implication that emerges from this

conceptanalysisis the questionable validity ofthe com-

monly used operationaldefinition ofthe term ‘transforma-

tional leadership.’TFL is definedby Bass and Avolio

(2004)as ‘a type ofleadership style thatleads to positive

changes in those who follow.’Leaderswho use this style

‘are generally energetic, enthusiastic and passionate [as well

as] . . .concerned and involved in the process [and] focused

on helping every member of the group succeed as well’(p.

25). A problem with this definition is that it defines Trans-

formationalLeadership on the basis of what it does,rather

than what it is.For a full understanding of the meaning of

the term,it is essentialto develop a definition based on the

traits and characteristics of the leader, rather than based on

the impact on followers.

Future research

Ample opportunitiesexist to develop and testleadership

models.This conceptanalysiscreatesa foundation for

future research by proposing a new definition of TFL,one

that is distinctfrom the antecedentsand consequencesof

the concept. The proposed definition is as follows:

Transformationalleadership isan integrativestyle of

leadership as wellas a setof competencies.The Transfor-

mationalLeadership style isidentified by an enthusiastic,

emotionally mature,visionary and courageous lifelong lear-

ner who inspires and motivates by empowering and devel-

oping followers. Competencies essential to the

transformational leader include emotional intelligence, com-

munication, collaboration, coaching and mentoring.

This definition identifiesthe traits,antecedentsand the

consequences of the two faces of TFL: a set of competencies

and a leadership style.

Implications for nursing practice

This concept analysis bolsters nursing theory, research, edu-

cation and practice at a time when nursing leaders are posi-

tioned to becomemore prominentplayersin healthcare

reform and policy development.A growing responsibility

for expansion of practice requires strong and effective lead-

ership skills and an understanding of transformational lead-

ership will benefit this skill development and practice.

2650 © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

S.A. Fischer

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Conclusion

The process ofconstructing conceptualmeaning is crucial

for theory developmentand testing(Chinn & Kramer

2008).No concept analysis of TFL has yet been published

in the context of nursing, despite the prevalence in usage of

the term TFL, its prominence in conversations about organi-

zational influence and the lack of consensus regarding defini-

tion and group or individual-leveleffects of TFL (Wang &

Howell 2010).The present report addresses this gap in the

literature,contributing to the foundation of nursing knowl-

edge as itrelates to leadership theory,education,research

and practice,by proposing an improved operationaldefini-

tion and delineating essential competencies for TFL.

Funding

This research received no specific grantfrom any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the author.

Author contributions

All authors have agreed on the finalversion and meetat

least one of the following criteria [recommended by the

ICMJE (http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/)]:

•substantialcontributionsto conceptionand design,

acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

•drafting the article or revising it critically for important

intellectual content.

References

Anderson R.A., Issel L.M. & McDaniel R.R. (2003) Nursing

homes as complex adaptive systems:Relationship between

managementpractice and residentoutcomes.Nursing Research

52(1), 12–21.

Arulmani R., Rajendran S.D.& Suresh B. (2007)Adverse drug

reaction monitoring in a secondary care hospitalin South India.

British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 65(2), 210–216.

Bamford-Wade A.& Moss C. (2010) Transformationalleadership

and shared governance:an action study. Journal of Nursing

Management 18(7), 815–821.

Bass B.M. (1990) Bass & Stodgill’s Handbook of Leadership:

Theory,Research and ManagerialApplications.The Free Press,

New York, NY.

Bass B. & Avolio B.J. (1994) Improving Organizational

Effectivenessthrough Transformational Leadership. SAGE,

Thousand Oaks, CA.

Bass B. & SteidlmeierP. (1999) Ethics characterand authentic

transformationalleadership behaviour.Leadership Quarterly 10,

181–217.

Bass B.M. & Avolio B.J. (2004) Multifactor Leadership.

Questionnaire-5X ShortForm. Mind Garden, Redwood City,

CA.

Bass B.M., Avolio B.J., Jung D.I. & Berson Y. (2003)Predicting

unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional

leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology 88(2), 207–218.

Bates D.(2009) Globalpriorities for patient safety research.BMJ:

British MedicalJournal 338(7705),1242–1244.Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/41552057.

Buckner E.B.,Anderson D.J.,Garzon N., Hafsteinsdottir T.B.,Lai

C.K. & Roshan R. (2014) Perspectiveson global nursing

leadership:internationalexperiences from the field.International

Nursing Review 61(4), 463–471.

CarlessS., Wearing A. & Mann L. (2000) A short measure of

transformationalleadership.Journal of Business and Psychology

14(3), 389–405.

Casida J. & Pinto-Zipp G. (2008) Leadership-organizational

culture relationship in nursingunits of acute care hospitals.

Nursing Economics 26(1), 7–15.

Chinn P.L. & Kramer M.K. (2008) IntegratedTheory and

Knowledge Development in Nursing. Mosby, St. Louis, MO.

Clavelle J.T. (2012) Transformational leadership: visibility,

accessibility, and communication. Journal of Nursing

Administration 42(7–8), 345–346.

Cummings G., Lee H., Macgregor T., Davey M., Wong C., Paul L.

& Stafford E. (2008) Factors contributing to nursing leadership:

a systematic review.Journal of Health ServicesResearch and

Policy 13(4), 240–248.

Dunham-Taylor J. (2000) Nurse executive transformational

leadershipfound in participativeorganizations.Journal of

Nursing Administration 30, 241–250.

Duygulu S. & Kublay G. (2011) Transformationalleadership

training programmefor chargenurses.Journal of Advanced

Nursing 67(3), 633–642.

EdwardsG., SchynsB., Gill R. & Higgs M. (2012) The MLQ

factor structure in a UK context.Leadership and Organization

Development Journal 33(4), 369–382.

EisenbeissS.A., van KnippenbergD. & Boerner S. (2008)

Transformationalleadership and team innovation:integrating

team climate principles.Journal of Applied Psychology 93(6),

1438–1446.

Gowen C.R. 3rd, Henagan S.C. & McFadden K.L. (2009) Knowledge

managementas a mediatorfor the efficacy oftransformational

leadership and quality management initiatives in U.S.health care.

Health Care Management Review 34(2), 129–140.

Howell J. & Avolio B. (1993) Transformationalleadership,

transactionalleadership,locus of control, and support for

innovation: key predictors of consolidated business-unit

performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 78(6), 891–902.

Hutchinson M.& Jackson D. (2013)Transformationalleadership

in nursing: towards a more critical interpretation.Nursing

Inquiry 20(1), 11–22.

James J.T. (2013) A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms

associated with hospitalcare. Journal of Patient Safety 9(3),

122–128.

© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2651

JAN: CONCEPT ANALYSIS Transformational leadership

The process ofconstructing conceptualmeaning is crucial

for theory developmentand testing(Chinn & Kramer

2008).No concept analysis of TFL has yet been published

in the context of nursing, despite the prevalence in usage of

the term TFL, its prominence in conversations about organi-

zational influence and the lack of consensus regarding defini-

tion and group or individual-leveleffects of TFL (Wang &

Howell 2010).The present report addresses this gap in the

literature,contributing to the foundation of nursing knowl-

edge as itrelates to leadership theory,education,research

and practice,by proposing an improved operationaldefini-

tion and delineating essential competencies for TFL.

Funding

This research received no specific grantfrom any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the author.

Author contributions

All authors have agreed on the finalversion and meetat

least one of the following criteria [recommended by the

ICMJE (http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/)]:

•substantialcontributionsto conceptionand design,

acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

•drafting the article or revising it critically for important

intellectual content.

References

Anderson R.A., Issel L.M. & McDaniel R.R. (2003) Nursing

homes as complex adaptive systems:Relationship between

managementpractice and residentoutcomes.Nursing Research

52(1), 12–21.

Arulmani R., Rajendran S.D.& Suresh B. (2007)Adverse drug

reaction monitoring in a secondary care hospitalin South India.

British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 65(2), 210–216.

Bamford-Wade A.& Moss C. (2010) Transformationalleadership

and shared governance:an action study. Journal of Nursing

Management 18(7), 815–821.

Bass B.M. (1990) Bass & Stodgill’s Handbook of Leadership:

Theory,Research and ManagerialApplications.The Free Press,

New York, NY.

Bass B. & Avolio B.J. (1994) Improving Organizational

Effectivenessthrough Transformational Leadership. SAGE,

Thousand Oaks, CA.

Bass B. & SteidlmeierP. (1999) Ethics characterand authentic

transformationalleadership behaviour.Leadership Quarterly 10,