Business Development Case Study: Frankfurt Pump Company Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/20

|18

|7380

|919

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study examines the Frankfurt Pump Company (FPC), a German manufacturer of high-pressure injection pumps. Founded in 1965, FPC initially focused on the oil and gas industry, achieving a dominant market position. The case details FPC's product lines, including various pump series and models, end-users such as oil and gas companies, car wash systems, and the reverse osmosis market. It also covers the aftermarket, distribution channels, pricing strategies, and the impact of frequent ownership changes. The analysis highlights challenges such as inefficient manufacturing, neglected customer relationships, and warranty issues, as well as the strategies implemented by the new management team. The case provides insights into market dynamics, competition, and the importance of adapting to changing market needs.

CONTENTS

ASSESSMENT CASE STUDY: FRANKFURT PUMP COMPANY GmbH..................................3

1. BACKGROUND..........................................................................................................3

2. PRODUCT LINES....................................................................................................... 4

3. END USERS...............................................................................................................7

4. THE AFTERMARKET..................................................................................................9

5. DISTRIBUTION........................................................................................................12

6. PRICING AND PROFIT MIX......................................................................................17

Reference

Zimmerman, A. & Blythe, J. (2013) Comprehensive Case: The Frankfurt Pump Company

GmbH (FPC) pp474-492 in Zimmerman & Blythe, Business to Business Marketing

Management A Global Perspective, Second Edition. Abingdon: Routledge.

version 2 (type edits only) 1

ASSESSMENT CASE STUDY: FRANKFURT PUMP COMPANY GmbH..................................3

1. BACKGROUND..........................................................................................................3

2. PRODUCT LINES....................................................................................................... 4

3. END USERS...............................................................................................................7

4. THE AFTERMARKET..................................................................................................9

5. DISTRIBUTION........................................................................................................12

6. PRICING AND PROFIT MIX......................................................................................17

Reference

Zimmerman, A. & Blythe, J. (2013) Comprehensive Case: The Frankfurt Pump Company

GmbH (FPC) pp474-492 in Zimmerman & Blythe, Business to Business Marketing

Management A Global Perspective, Second Edition. Abingdon: Routledge.

version 2 (type edits only) 1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ASSESSMENT CASE STUDY: FRANKFURT PUMP COMPANY GmbH

1. BACKGROUND

The Frankfurt Pump Company (FPC) was founded in 1965 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, by

Heinz Hoffman, a mechanical engineer. FPC initially manufactured specialty tools for the oil

and gas industry. The speciality tools provided capital for Hoffman to design and

manufacture a quality high-pressure patented pump. By the mid-1980s, the patented FPC

pump enjoyed a reputation as the best high-pressure injection pump available. The pump

was particularly well suited to the requirements of secondary oil and gas recovery with

steam injection. FPC soon captured a dominant market position in the oil and gas industry.

After Hoffman’s death in 1979 his son Frederick was in charge of the rapidly growing

company. However, Frederick had interests in car racing and sold the company in 1995 to a

group of 8 investors. The company’s growth and high profits continued, and its pump was

still considered the best quality high-pressure pump in 2000, when the company was sold for

a second time to a major coal company. In 2001, the coal company was losing money and

needed the income FPC Pump was generating. However, in 2003 the coal company sold FPC

for 2.5 times what it had paid for it. The buyer was one of the largest steel companies in the

United States. FPC Pump was again sold in 2008 to a large multinational integrated oil

company based in Europe. Division sales for 2008-2011 are shown in Exhibit 1.

FPCs pumps were regarded as the “standard of oil patch high pressure injection pumps.” The

pumps were widely recognized as the best engineered for high pressure steam injection and

corrosion problems in the oil fields. The company was managed by leading engineers.

The frequent buying and divesting of FPC Pump has many negative effects on the business.

Initially, the division was primarily bought as a financial “cash cow”, which meant it was

milked for cash, with little reinvestment. Much of the company’s manufacturing was

inefficient, and FPC was believed to be a high-cost producer. The new owners knew little

about the high-pressure injection pump business, which had no technical, manufacturing or

marketing unity with their other operations. Relationships with customers and distributors

were neglected. Especially when energy booms allowed FPC to ride the growth curve and

sell all it could produce.

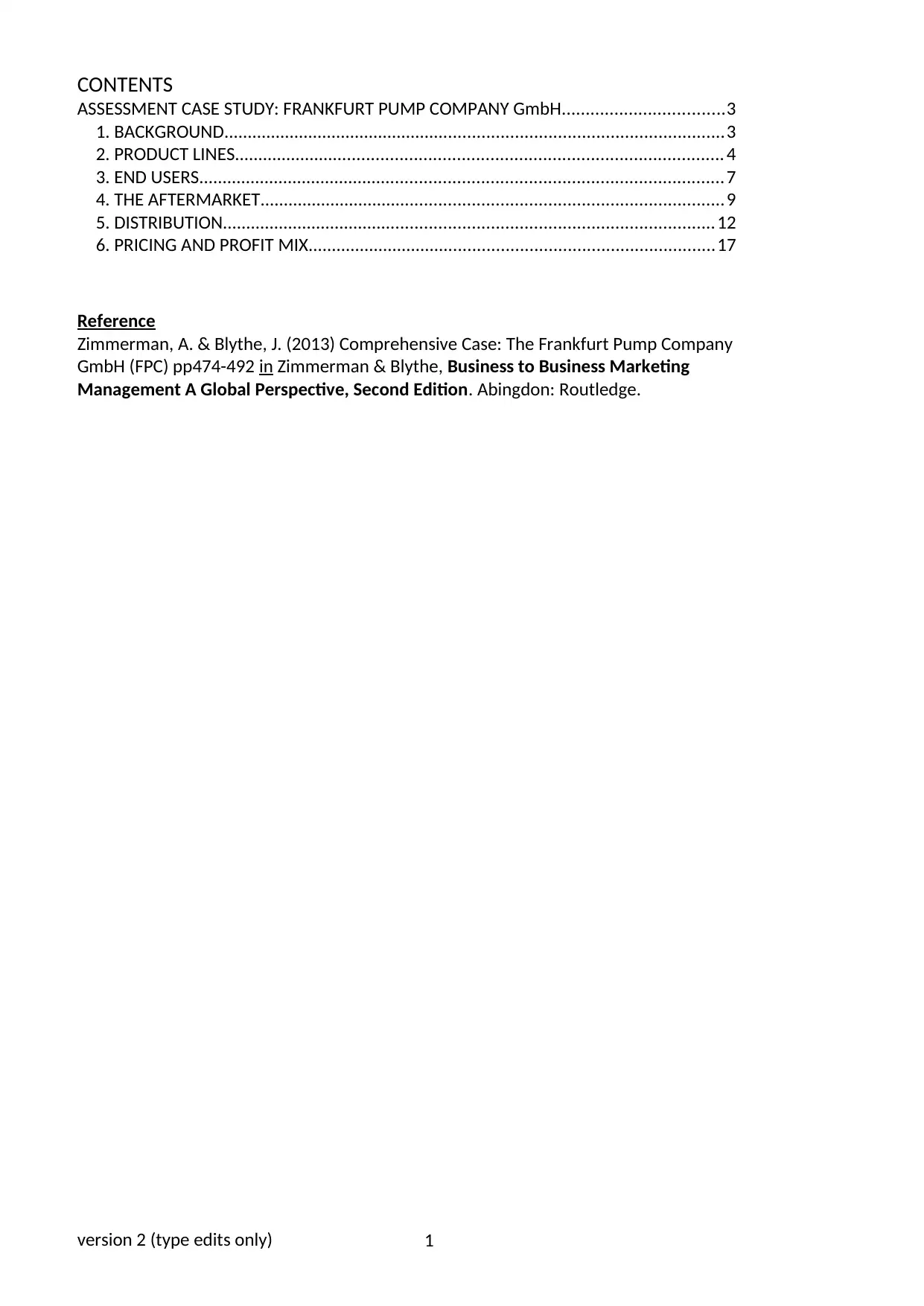

Exhibit 1 Divisional Sales by type of account (millions of Euros)

Account Type 2008 2009 2010 2011

Stocking Distributors 15.2 19.0 25.1 18.5

Non-stocking Distributors 4.1 5.2 7.3 4.1

Direct Sales 9.9 13.7 18.7 9.7

Interdivisional 1.1 1.0 1.4 2.3

Reverse Osmosis 0.6 0.9 1.2 2.4

30.9 39.8 53.7 37.0

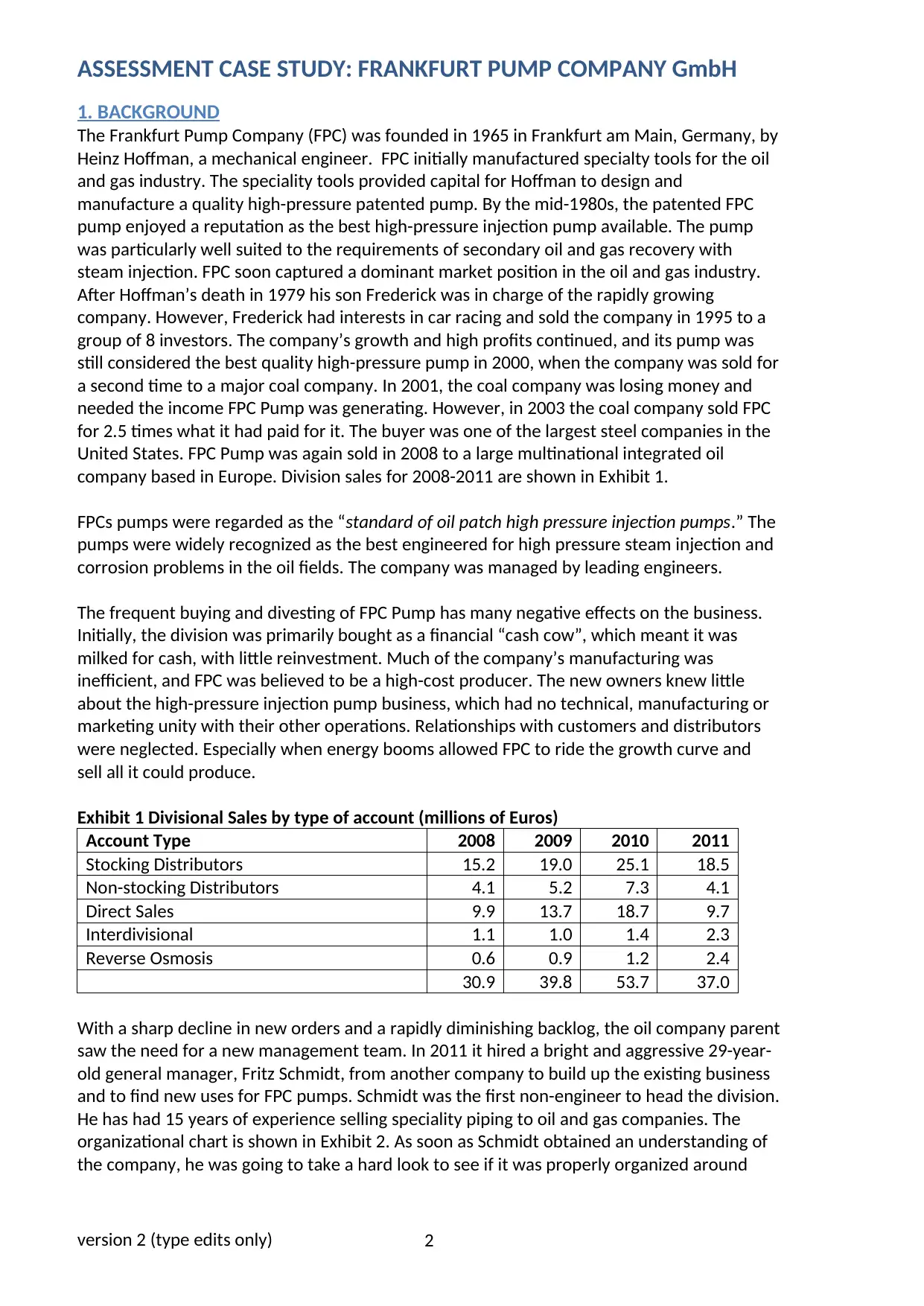

With a sharp decline in new orders and a rapidly diminishing backlog, the oil company parent

saw the need for a new management team. In 2011 it hired a bright and aggressive 29-year-

old general manager, Fritz Schmidt, from another company to build up the existing business

and to find new uses for FPC pumps. Schmidt was the first non-engineer to head the division.

He has had 15 years of experience selling speciality piping to oil and gas companies. The

organizational chart is shown in Exhibit 2. As soon as Schmidt obtained an understanding of

the company, he was going to take a hard look to see if it was properly organized around

version 2 (type edits only) 2

1. BACKGROUND

The Frankfurt Pump Company (FPC) was founded in 1965 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, by

Heinz Hoffman, a mechanical engineer. FPC initially manufactured specialty tools for the oil

and gas industry. The speciality tools provided capital for Hoffman to design and

manufacture a quality high-pressure patented pump. By the mid-1980s, the patented FPC

pump enjoyed a reputation as the best high-pressure injection pump available. The pump

was particularly well suited to the requirements of secondary oil and gas recovery with

steam injection. FPC soon captured a dominant market position in the oil and gas industry.

After Hoffman’s death in 1979 his son Frederick was in charge of the rapidly growing

company. However, Frederick had interests in car racing and sold the company in 1995 to a

group of 8 investors. The company’s growth and high profits continued, and its pump was

still considered the best quality high-pressure pump in 2000, when the company was sold for

a second time to a major coal company. In 2001, the coal company was losing money and

needed the income FPC Pump was generating. However, in 2003 the coal company sold FPC

for 2.5 times what it had paid for it. The buyer was one of the largest steel companies in the

United States. FPC Pump was again sold in 2008 to a large multinational integrated oil

company based in Europe. Division sales for 2008-2011 are shown in Exhibit 1.

FPCs pumps were regarded as the “standard of oil patch high pressure injection pumps.” The

pumps were widely recognized as the best engineered for high pressure steam injection and

corrosion problems in the oil fields. The company was managed by leading engineers.

The frequent buying and divesting of FPC Pump has many negative effects on the business.

Initially, the division was primarily bought as a financial “cash cow”, which meant it was

milked for cash, with little reinvestment. Much of the company’s manufacturing was

inefficient, and FPC was believed to be a high-cost producer. The new owners knew little

about the high-pressure injection pump business, which had no technical, manufacturing or

marketing unity with their other operations. Relationships with customers and distributors

were neglected. Especially when energy booms allowed FPC to ride the growth curve and

sell all it could produce.

Exhibit 1 Divisional Sales by type of account (millions of Euros)

Account Type 2008 2009 2010 2011

Stocking Distributors 15.2 19.0 25.1 18.5

Non-stocking Distributors 4.1 5.2 7.3 4.1

Direct Sales 9.9 13.7 18.7 9.7

Interdivisional 1.1 1.0 1.4 2.3

Reverse Osmosis 0.6 0.9 1.2 2.4

30.9 39.8 53.7 37.0

With a sharp decline in new orders and a rapidly diminishing backlog, the oil company parent

saw the need for a new management team. In 2011 it hired a bright and aggressive 29-year-

old general manager, Fritz Schmidt, from another company to build up the existing business

and to find new uses for FPC pumps. Schmidt was the first non-engineer to head the division.

He has had 15 years of experience selling speciality piping to oil and gas companies. The

organizational chart is shown in Exhibit 2. As soon as Schmidt obtained an understanding of

the company, he was going to take a hard look to see if it was properly organized around

version 2 (type edits only) 2

market opportunities. One of the first personnel changes Schmidt made was to dismiss the

marketing vice president and hire Greta Klaus, an engineer he had worked with 3 years

earlier.

Exhibit 2 FPC Pump Division Organisation

2. PRODUCT LINES

FPC was the largest manufacturer of high-pressure injection pumps. The pumps and parts

had been made at the original locations since 1970. As the company grew, adjacent land was

acquired and extensions added to the original building.

A centrifugal pump line FPC manufactured was usually selected for applications that require

high pressure. FPC’s pumps have a high volumetric efficiency and consumed less energy than

other types of pumps. The rated or recommended speed of pumps is important when a

design engineer selects a pump to go into a new installation. Most pump manufacturers use

the term “rated” speed interchangeably with “recommended” speed. The customer’s design

engineer selects a rated speed that will provide sufficient suction and discharge performance

in moving the material. The recommended speeds of the FPC lines of pumps are shown in

Exhibit 3.

version 2 (type edits only) 3

marketing vice president and hire Greta Klaus, an engineer he had worked with 3 years

earlier.

Exhibit 2 FPC Pump Division Organisation

2. PRODUCT LINES

FPC was the largest manufacturer of high-pressure injection pumps. The pumps and parts

had been made at the original locations since 1970. As the company grew, adjacent land was

acquired and extensions added to the original building.

A centrifugal pump line FPC manufactured was usually selected for applications that require

high pressure. FPC’s pumps have a high volumetric efficiency and consumed less energy than

other types of pumps. The rated or recommended speed of pumps is important when a

design engineer selects a pump to go into a new installation. Most pump manufacturers use

the term “rated” speed interchangeably with “recommended” speed. The customer’s design

engineer selects a rated speed that will provide sufficient suction and discharge performance

in moving the material. The recommended speeds of the FPC lines of pumps are shown in

Exhibit 3.

version 2 (type edits only) 3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

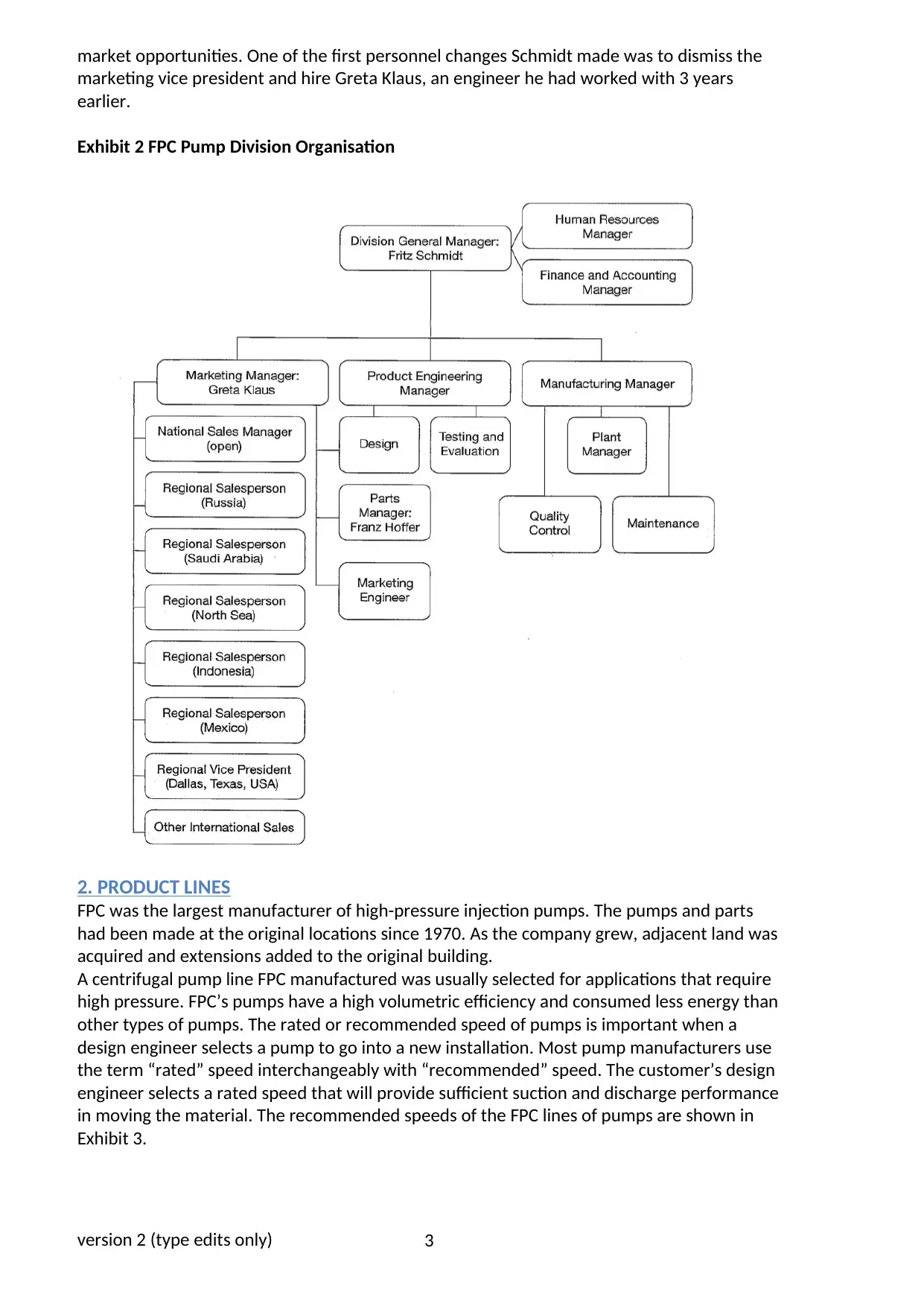

Exhibit 3. Recommended Speeds of FPC Pumps

Pump Series Stroke Recommended

Speed

Maximum Speed

E-10,E-50,E-100,E-100 2 3/16” 400RPM 500RPM

E-330, E-300 3 1/8” 400RPM 500RPM

E-125 3 1/2” 400RPM 500RPM

E-100 4 ½” 400RPM 500RPM

E-165 4 1/2” 360RPM 400RPM

E-160 6 1/8” 324RPM 360RPM

E-250,E-360,E-600 7 1/8” 324RPM 360RPM

Because FPC pumps were well engineered, they were often operated at much higher RPMs

than competitor’s pumps, which would fail or need parts more frequently, FPC pumps were

the only ones that held up in the severe operating conditions of the South African gold

mines. The head of engineering stated:

“Our pumps can be run at the highest RPMs with no problems. We use the

highest-quality Timken bearings and have the strongest crankshafts. A

helicopter literally drop-shipped one of our pumps into an oil-gathering

field in Kazakhstan with no damage whatsoever. Our 100% inspection is

another check to make sure no defects leave our shipping dock.”

FPC had 16 product lines or series, as shown in Exhibit 4. Within each of the 16 series there

were 2 or 3 different models, for a total of 48 different pumps. Exhibit 4 also shows the

quarterly shipments of all pumps for the 2009-11 period. One FPC oil field distributor

described FPC’s product line as:

“…the best and broadest in the industry. But at E12,000 to E100,000 per

pump, depending on the size, I can’t stock many of them. Some of them

are hot items and others rarely ever fit a customer’s steam injection

pumping requirements.”

Exhibit 4. 2009-2011 Quarterly Pump Unit Shipments

Note: the major difference among these product lines is the size of the basic design. The E-10

is the smallest model and the 3L is the largest.

Competition

In addition to FPC, 4 other companies produced high-pressure injection pumps. Two were

divisions of major steel companies that also owned large chains of oil field supply stores, The

third competitor Oilflo, was the only one that carried a full line which competed with FPC

version 2 (type edits only) 4

Pump Series Stroke Recommended

Speed

Maximum Speed

E-10,E-50,E-100,E-100 2 3/16” 400RPM 500RPM

E-330, E-300 3 1/8” 400RPM 500RPM

E-125 3 1/2” 400RPM 500RPM

E-100 4 ½” 400RPM 500RPM

E-165 4 1/2” 360RPM 400RPM

E-160 6 1/8” 324RPM 360RPM

E-250,E-360,E-600 7 1/8” 324RPM 360RPM

Because FPC pumps were well engineered, they were often operated at much higher RPMs

than competitor’s pumps, which would fail or need parts more frequently, FPC pumps were

the only ones that held up in the severe operating conditions of the South African gold

mines. The head of engineering stated:

“Our pumps can be run at the highest RPMs with no problems. We use the

highest-quality Timken bearings and have the strongest crankshafts. A

helicopter literally drop-shipped one of our pumps into an oil-gathering

field in Kazakhstan with no damage whatsoever. Our 100% inspection is

another check to make sure no defects leave our shipping dock.”

FPC had 16 product lines or series, as shown in Exhibit 4. Within each of the 16 series there

were 2 or 3 different models, for a total of 48 different pumps. Exhibit 4 also shows the

quarterly shipments of all pumps for the 2009-11 period. One FPC oil field distributor

described FPC’s product line as:

“…the best and broadest in the industry. But at E12,000 to E100,000 per

pump, depending on the size, I can’t stock many of them. Some of them

are hot items and others rarely ever fit a customer’s steam injection

pumping requirements.”

Exhibit 4. 2009-2011 Quarterly Pump Unit Shipments

Note: the major difference among these product lines is the size of the basic design. The E-10

is the smallest model and the 3L is the largest.

Competition

In addition to FPC, 4 other companies produced high-pressure injection pumps. Two were

divisions of major steel companies that also owned large chains of oil field supply stores, The

third competitor Oilflo, was the only one that carried a full line which competed with FPC

version 2 (type edits only) 4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

across the board. Oilflo was founded in the mid-1960s. Located in Dallas, Texas, it was a

privately held firm with sales believed to be about 35% less than FPC’s. The fourth

competitor was a UK manufacturer of industrial pumps that recently began selling in the oil

field market.

Many more competitors produced parts for high-pressure oil field pumps. In addition to the

four producers of pumps that also produced parts, there were 18-20 pump part suppliers.

Most of these were small 2-5 person firms. However, 4 of the parts firms were believed to be

E20-30m businesses. These suppliers were called parts pirates. The parts suppliers did little

or no service or repair work, but were essentially small machine shops that made standard

parts for the more popular models of high-pressure injection pumps.

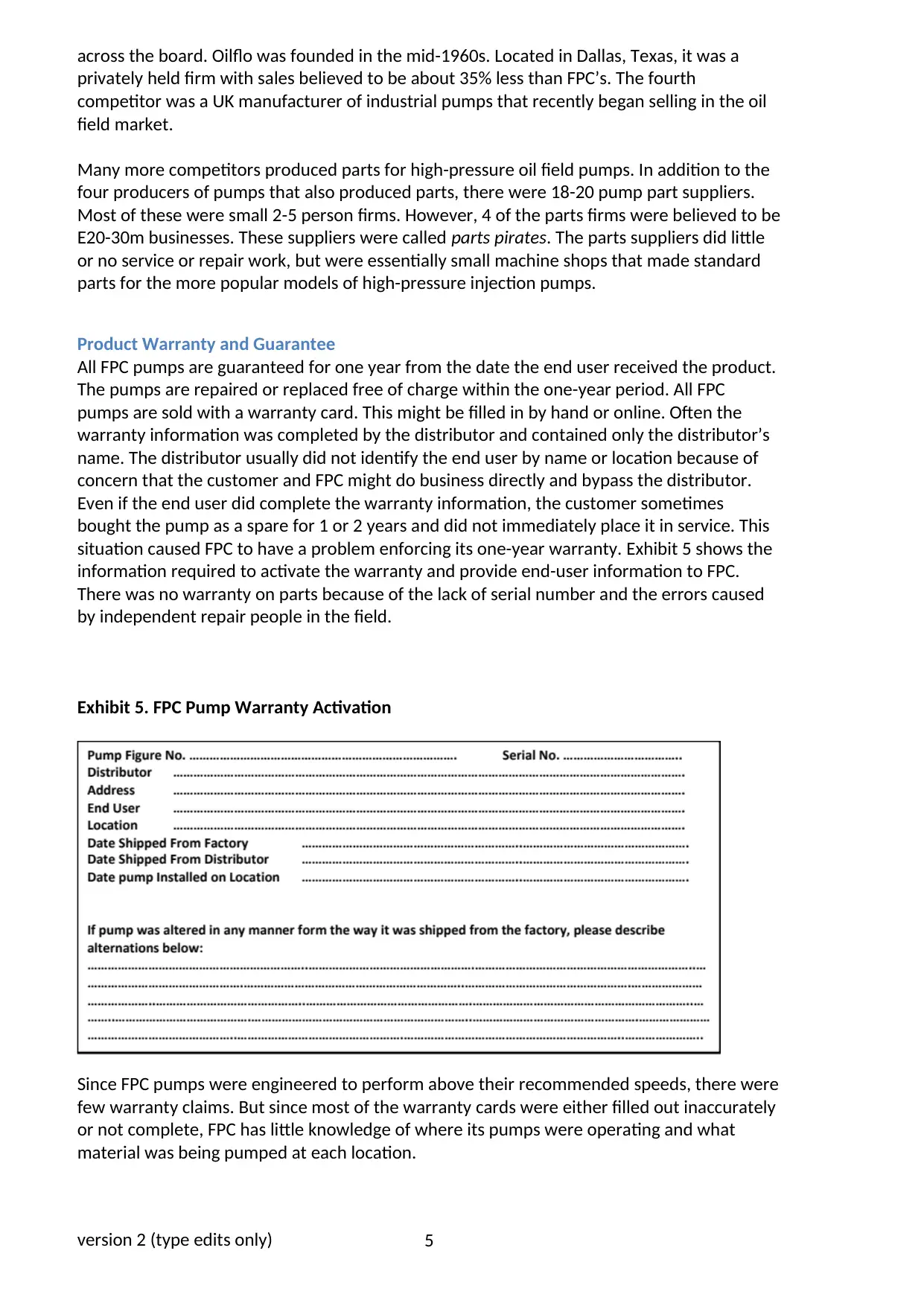

Product Warranty and Guarantee

All FPC pumps are guaranteed for one year from the date the end user received the product.

The pumps are repaired or replaced free of charge within the one-year period. All FPC

pumps are sold with a warranty card. This might be filled in by hand or online. Often the

warranty information was completed by the distributor and contained only the distributor’s

name. The distributor usually did not identify the end user by name or location because of

concern that the customer and FPC might do business directly and bypass the distributor.

Even if the end user did complete the warranty information, the customer sometimes

bought the pump as a spare for 1 or 2 years and did not immediately place it in service. This

situation caused FPC to have a problem enforcing its one-year warranty. Exhibit 5 shows the

information required to activate the warranty and provide end-user information to FPC.

There was no warranty on parts because of the lack of serial number and the errors caused

by independent repair people in the field.

Exhibit 5. FPC Pump Warranty Activation

Since FPC pumps were engineered to perform above their recommended speeds, there were

few warranty claims. But since most of the warranty cards were either filled out inaccurately

or not complete, FPC has little knowledge of where its pumps were operating and what

material was being pumped at each location.

version 2 (type edits only) 5

privately held firm with sales believed to be about 35% less than FPC’s. The fourth

competitor was a UK manufacturer of industrial pumps that recently began selling in the oil

field market.

Many more competitors produced parts for high-pressure oil field pumps. In addition to the

four producers of pumps that also produced parts, there were 18-20 pump part suppliers.

Most of these were small 2-5 person firms. However, 4 of the parts firms were believed to be

E20-30m businesses. These suppliers were called parts pirates. The parts suppliers did little

or no service or repair work, but were essentially small machine shops that made standard

parts for the more popular models of high-pressure injection pumps.

Product Warranty and Guarantee

All FPC pumps are guaranteed for one year from the date the end user received the product.

The pumps are repaired or replaced free of charge within the one-year period. All FPC

pumps are sold with a warranty card. This might be filled in by hand or online. Often the

warranty information was completed by the distributor and contained only the distributor’s

name. The distributor usually did not identify the end user by name or location because of

concern that the customer and FPC might do business directly and bypass the distributor.

Even if the end user did complete the warranty information, the customer sometimes

bought the pump as a spare for 1 or 2 years and did not immediately place it in service. This

situation caused FPC to have a problem enforcing its one-year warranty. Exhibit 5 shows the

information required to activate the warranty and provide end-user information to FPC.

There was no warranty on parts because of the lack of serial number and the errors caused

by independent repair people in the field.

Exhibit 5. FPC Pump Warranty Activation

Since FPC pumps were engineered to perform above their recommended speeds, there were

few warranty claims. But since most of the warranty cards were either filled out inaccurately

or not complete, FPC has little knowledge of where its pumps were operating and what

material was being pumped at each location.

version 2 (type edits only) 5

3. END USERS

Oil and Gas Systems

The largest current use of FPC pumps is in the oil and gas industry. Steam flooding was a

specific technique for which most FPC pumps were used in oil and exploration. Steam

flooding is a method of secondary oil recovery where steam is pumped down and forces

more oil out of the well. Steam flooding injection oil recovery systems always require a high-

pressure pump. Natural gas plants treat gas by taking the hydrogen sulphide and water out

of the gas. High-pressure injection pumps are used for this purpose. Natural gas by-products

like LPG are then injected into a pipeline, and high-pressure injection pumps are also use to

perform this task. A new and important market is hydraulic fracturing, known as ‘fracking’,

which requires pumping high-pressure water into underground natural gas reserves,

breaking up the rock and making the gas easier to extract. Many environmentalists have

expressed concerns about this method. There are claims of contamination of water and soil

in areas where extensive fracking has been used.

Car Wash Systems

Automated high-pressure car wash systems need high-pressure pumps. Two of the largest

automated car wash builders were located near FPC’s factory. In the late 1990’s FPC pumps

were designed into many of the original car wash equipment systems. FPC was a major

factor in the car wash pump market. But as the automatic car wash business became more

cost-sensitive, FPC lost most of the OEM business to lower-priced pumps and was

subsequently ‘designed out’ of most new systems. The average car wash system needs

water pumped at 700-800psi, whereas FPC pumps operated at 2,000psi. FPC’s engineering

manager stated:

“…we could have built low-pressure pumps for car washes, but we were more

interested in the high-pressure needs of oil and gas. We once had a committee to

rethink this market. We never had anyone do a study or take responsibility for the

car wash market. The pump we sold to car washes was the same one that went to

the oil and gas folks. We never had the car wash replacement pump or parts

business. Once in a while we’d get a phone call here in Frankfurt from one of the car

wash people, but we didn’t have distributors to serve that replacement market.

They do a lot of car washing in the snow and frost belt, where people take salt off

their cars. Those aren’t the same areas or distributors as where there are oil fields.

Furthermore, after we’d sell a pump to people who were building car washes, we

had no idea where they were shipping and installing the finished system, which

might later need parts or a replacement pump.”

Reverse Osmosis Market

FPC had had an interest in the reverse osmosis market for the last 15 years. Reverse osmosis

(RO) is a process in which salt or brackish water is pumped with high-pressure against a

membrane filter. The fresh water migrates to one side of the membrane, and the salt water

stays on the other side. The company that developed the membrane came to FPC for the

first pumps used to test the membranes. When the membrane producer’s design engineers

wrote technical papers in this area they referred to the FPC pumps. That helped establish

FPC’s name in the RO market, where high pressure was necessary. Some FPC pump sales had

been going to RO systems builders for the last 5 years, as shown in Exhibit 1. Since this was

also a different market for FPC, it did not have distributors that repaired pumps or supplied

version 2 (type edits only) 6

Oil and Gas Systems

The largest current use of FPC pumps is in the oil and gas industry. Steam flooding was a

specific technique for which most FPC pumps were used in oil and exploration. Steam

flooding is a method of secondary oil recovery where steam is pumped down and forces

more oil out of the well. Steam flooding injection oil recovery systems always require a high-

pressure pump. Natural gas plants treat gas by taking the hydrogen sulphide and water out

of the gas. High-pressure injection pumps are used for this purpose. Natural gas by-products

like LPG are then injected into a pipeline, and high-pressure injection pumps are also use to

perform this task. A new and important market is hydraulic fracturing, known as ‘fracking’,

which requires pumping high-pressure water into underground natural gas reserves,

breaking up the rock and making the gas easier to extract. Many environmentalists have

expressed concerns about this method. There are claims of contamination of water and soil

in areas where extensive fracking has been used.

Car Wash Systems

Automated high-pressure car wash systems need high-pressure pumps. Two of the largest

automated car wash builders were located near FPC’s factory. In the late 1990’s FPC pumps

were designed into many of the original car wash equipment systems. FPC was a major

factor in the car wash pump market. But as the automatic car wash business became more

cost-sensitive, FPC lost most of the OEM business to lower-priced pumps and was

subsequently ‘designed out’ of most new systems. The average car wash system needs

water pumped at 700-800psi, whereas FPC pumps operated at 2,000psi. FPC’s engineering

manager stated:

“…we could have built low-pressure pumps for car washes, but we were more

interested in the high-pressure needs of oil and gas. We once had a committee to

rethink this market. We never had anyone do a study or take responsibility for the

car wash market. The pump we sold to car washes was the same one that went to

the oil and gas folks. We never had the car wash replacement pump or parts

business. Once in a while we’d get a phone call here in Frankfurt from one of the car

wash people, but we didn’t have distributors to serve that replacement market.

They do a lot of car washing in the snow and frost belt, where people take salt off

their cars. Those aren’t the same areas or distributors as where there are oil fields.

Furthermore, after we’d sell a pump to people who were building car washes, we

had no idea where they were shipping and installing the finished system, which

might later need parts or a replacement pump.”

Reverse Osmosis Market

FPC had had an interest in the reverse osmosis market for the last 15 years. Reverse osmosis

(RO) is a process in which salt or brackish water is pumped with high-pressure against a

membrane filter. The fresh water migrates to one side of the membrane, and the salt water

stays on the other side. The company that developed the membrane came to FPC for the

first pumps used to test the membranes. When the membrane producer’s design engineers

wrote technical papers in this area they referred to the FPC pumps. That helped establish

FPC’s name in the RO market, where high pressure was necessary. Some FPC pump sales had

been going to RO systems builders for the last 5 years, as shown in Exhibit 1. Since this was

also a different market for FPC, it did not have distributors that repaired pumps or supplied

version 2 (type edits only) 6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

parts. A few replacement unit and part orders were received by telephone. About 90% of the

RO sales were direct, and not through distributors. The size and growth prospects of the

commercial RO market were not known to FPC.

Additional End Users

Over the years, a few FPC pumps have been sold as sewer cleaning pumps in municipal

waste systems. This was believed to be a very price-sensitive market. A long-time FPC

engineer stated:

“..we have received enquiries for a lot of strange applications that are foreign to

us. That’s how the car wash systems business came in, through the window. Since

the pumping of oil and gas is what we know best, other applications took a low

priority.”

The marketing manager, Greta Klaus, walked into the room, heard the last part of the

conversation and added:

“..we don’t even have good market data on the oil and gas market we are

supposed to know. I just wish we had market shares by geographic oil and gas

regions. Since we sell to distributors who build systems for oil and gas end users,

we don’t have enough contact and feedback from our ultimate customers. Our

distributors don’t know where many of the customers are either, especially if they

didn’t sell them the original pump, and we are really in the dark about the

location and size of the parts market for high-pressure injection pumps.”

Oil and Gas OEM Installations

The large oil companies have engineering departments that write specifications and

sometimes specify a brand to the pump distributor that builds the OEM system. The high-

pressure injection oil field pumping system typically consists of a pump, a diesel or electric

motor, and a V-belt chain drive all mounted on a “skid”. The specifying of the type and size

of pump is guided by what is being pumped, how much per day, and at what pressure. The

OEM system builder uses the end user’s technical performance parameters to select the

pump brand. The pump manufacturer had to call on both the end user and the OEM builder

to sell the system.

4. THE AFTERMARKET

The repair and replacement pump purchase was somewhat less formal than the OEM buying

decision. However, the larger oil company maintenance departments would frequently

specify the general type of pump and quantity desired and then put the business out to bid

for quotes. If a large end user has 20 pumps of one brand in an oil field, the twenty-first

would most likely be the same brand to reduce repair problems and the number of parts

needed. The smaller independent company maintenance departments usually bought one

pump at a time from the pump distributor they had bought from before. Normally they did

not ask for quotes from multiple distributors. They also did not plan the purchase and

usually waited until the last minute to repair or replace a pump. During the oil boom years,

customers did not have the time to conduct preventative maintenance on their high-

pressure injection pumping systems. They waited until the pressure fell or visible leaks

version 2 (type edits only) 7

RO sales were direct, and not through distributors. The size and growth prospects of the

commercial RO market were not known to FPC.

Additional End Users

Over the years, a few FPC pumps have been sold as sewer cleaning pumps in municipal

waste systems. This was believed to be a very price-sensitive market. A long-time FPC

engineer stated:

“..we have received enquiries for a lot of strange applications that are foreign to

us. That’s how the car wash systems business came in, through the window. Since

the pumping of oil and gas is what we know best, other applications took a low

priority.”

The marketing manager, Greta Klaus, walked into the room, heard the last part of the

conversation and added:

“..we don’t even have good market data on the oil and gas market we are

supposed to know. I just wish we had market shares by geographic oil and gas

regions. Since we sell to distributors who build systems for oil and gas end users,

we don’t have enough contact and feedback from our ultimate customers. Our

distributors don’t know where many of the customers are either, especially if they

didn’t sell them the original pump, and we are really in the dark about the

location and size of the parts market for high-pressure injection pumps.”

Oil and Gas OEM Installations

The large oil companies have engineering departments that write specifications and

sometimes specify a brand to the pump distributor that builds the OEM system. The high-

pressure injection oil field pumping system typically consists of a pump, a diesel or electric

motor, and a V-belt chain drive all mounted on a “skid”. The specifying of the type and size

of pump is guided by what is being pumped, how much per day, and at what pressure. The

OEM system builder uses the end user’s technical performance parameters to select the

pump brand. The pump manufacturer had to call on both the end user and the OEM builder

to sell the system.

4. THE AFTERMARKET

The repair and replacement pump purchase was somewhat less formal than the OEM buying

decision. However, the larger oil company maintenance departments would frequently

specify the general type of pump and quantity desired and then put the business out to bid

for quotes. If a large end user has 20 pumps of one brand in an oil field, the twenty-first

would most likely be the same brand to reduce repair problems and the number of parts

needed. The smaller independent company maintenance departments usually bought one

pump at a time from the pump distributor they had bought from before. Normally they did

not ask for quotes from multiple distributors. They also did not plan the purchase and

usually waited until the last minute to repair or replace a pump. During the oil boom years,

customers did not have the time to conduct preventative maintenance on their high-

pressure injection pumping systems. They waited until the pressure fell or visible leaks

version 2 (type edits only) 7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

occurred. A few large oil companies were now beginning to conduct preventative

maintenance on all their equipment.

When a high-pressure system breaks down the oil company needs a replacement pump or

part immediately because the cost of downtime can be between €6,000 -€15,000 per hour in

a secondary recovery well. Either the oil company’s maintenance personnel or an

independent pump service firm did the repair work. Approximately 70% of the repair work

was done by independent repair firms. Since competitive high-pressure units and parts were

interchangeable, the repair person did not have to specify original equipment and part brand

names.

OEM Pump Demand

The number of OEM oil pump installations is a function of the price of oil and the resulting

amount of exploration activity. The number of geophysical survey teams prospecting for oil

and gas is an early leading indicator of new oil and gas construction. The oil and gas

equipment repair market or aftermarket, however is more dependent on the number of in-

place and operating pumping jacks and offshore platforms. The demand for aftermarket

replacement equipment material and parts is considerably less cyclical than it is for items

going into oil and gas OEM equipment. When an independent repair firm inspected a faulty

high-pressure injection pump in the field, it usually informed the oil firm of the cost of the

needed repairs. As the cost of repairs approached the cost of a new pump, the repair firm

suggested that a new pump be installed. A pump repair was an oil firm maintenance expense

item, but a new pump was usually categorised as a capital equipment appropriation.

Pump and Component Parts Aftermarket

The size of the pump and component parts aftermarket depends on the in-place pump

population and age of each unit. Since FPC had the largest oil field population of any

manufacturer of high-pressure injection pumps, there was considerable potential for

replacement pumps and parts. Due to the incomplete warranty card information, FPC did

not have information on the location or age distribution of in-place units. To help FPC’s

planning, the engineering department had attempted to determine the average life of a

pump and the wear-out life for parts. But because of wide variances caused by differences in

viscosity, the chemical content of the crude oil, suction pressures and the RPMs at which the

oil firm operated the machine, it was very difficult to identify “average life” and recommend

repair and replacement schedules. However, it was common for FPC’s high-pressure

injection pumps to be in continuous operation for 20 to 35 years.

Pumping speeds, suction conditions and the nature of the fluid being pumped determined

the life of these parts. FPC produced nearly 800 parts, many of which were different sizes of

the same basic design. FPC’s wide product line created the need for a larger number of parts.

Most of the parts made by the five competitors were interchangeable. This

interchangeability also created an attractive opportunity for parts pirates and allowed

distributors to sell products to the parts pirates.

The fluid end parts were the major part of a pump repair bill. In a typical repair situation, 20-

30% of the cost was labour, with possibly some machine shop time, and the remaining 70-

80% was for parts, usually at the fluid end. For example, a purchase price of €15,000 for a

new high-pressure injection pump would require yearly fluid end parts costing between

€1,500-€3,200. The plungers would cost €450-€600 each, and a pump would have 3 or 5 of

version 2 (type edits only) 8

maintenance on all their equipment.

When a high-pressure system breaks down the oil company needs a replacement pump or

part immediately because the cost of downtime can be between €6,000 -€15,000 per hour in

a secondary recovery well. Either the oil company’s maintenance personnel or an

independent pump service firm did the repair work. Approximately 70% of the repair work

was done by independent repair firms. Since competitive high-pressure units and parts were

interchangeable, the repair person did not have to specify original equipment and part brand

names.

OEM Pump Demand

The number of OEM oil pump installations is a function of the price of oil and the resulting

amount of exploration activity. The number of geophysical survey teams prospecting for oil

and gas is an early leading indicator of new oil and gas construction. The oil and gas

equipment repair market or aftermarket, however is more dependent on the number of in-

place and operating pumping jacks and offshore platforms. The demand for aftermarket

replacement equipment material and parts is considerably less cyclical than it is for items

going into oil and gas OEM equipment. When an independent repair firm inspected a faulty

high-pressure injection pump in the field, it usually informed the oil firm of the cost of the

needed repairs. As the cost of repairs approached the cost of a new pump, the repair firm

suggested that a new pump be installed. A pump repair was an oil firm maintenance expense

item, but a new pump was usually categorised as a capital equipment appropriation.

Pump and Component Parts Aftermarket

The size of the pump and component parts aftermarket depends on the in-place pump

population and age of each unit. Since FPC had the largest oil field population of any

manufacturer of high-pressure injection pumps, there was considerable potential for

replacement pumps and parts. Due to the incomplete warranty card information, FPC did

not have information on the location or age distribution of in-place units. To help FPC’s

planning, the engineering department had attempted to determine the average life of a

pump and the wear-out life for parts. But because of wide variances caused by differences in

viscosity, the chemical content of the crude oil, suction pressures and the RPMs at which the

oil firm operated the machine, it was very difficult to identify “average life” and recommend

repair and replacement schedules. However, it was common for FPC’s high-pressure

injection pumps to be in continuous operation for 20 to 35 years.

Pumping speeds, suction conditions and the nature of the fluid being pumped determined

the life of these parts. FPC produced nearly 800 parts, many of which were different sizes of

the same basic design. FPC’s wide product line created the need for a larger number of parts.

Most of the parts made by the five competitors were interchangeable. This

interchangeability also created an attractive opportunity for parts pirates and allowed

distributors to sell products to the parts pirates.

The fluid end parts were the major part of a pump repair bill. In a typical repair situation, 20-

30% of the cost was labour, with possibly some machine shop time, and the remaining 70-

80% was for parts, usually at the fluid end. For example, a purchase price of €15,000 for a

new high-pressure injection pump would require yearly fluid end parts costing between

€1,500-€3,200. The plungers would cost €450-€600 each, and a pump would have 3 or 5 of

version 2 (type edits only) 8

them. Valves for the pumps would cost approximately €90 each, with 3 or 5 per pump.

Packing was €150 - €180 per pump. Every 2 or 3 years a major overhaul was usually needed.

Over a conservative 20-year pump life, it was common for the parts cost to be 2 or 3 times

the initial purchase cost.

Historically, all the major manufacturers of high-pressure injection pumps neglected the

parts market. As one FPC distributor stated:

“ The previous management at FPC was more interested in selling pumps or

metal tonnage rather than pursuing parts. Some producers saw the pump parts

business as a nuisance, and therefore let in the parts pirates. I never understood

why they all favoured the higher revenue but lower profit margin pump business

over the higher margin parts business”

Franz Hoffer is the manager of the aftermarket parts business. He is 59 years old and was an

FPC salesman for 29 years before taking this position. Hoffer is also independently wealthy

from the sale of his FPC stock in 1995 to the group of investors.

Parts ‘Pirates’

The higher profit margin in parts, the large pump population needing parts, and neglect by

the major pump producers attracted a large number of parts pirates to the injection pump

business. Only a few of the parts were protected by patents in various markets. Many pirates

were previously employed in the machine shops or sales areas of the pump sales and service

distributors. It was easy to enter the parts market, since it only required a machining tool,

usually a used one, and a small inventory of metal stock from which to machine parts. Most

were located in the centre of major oil field areas in simple structures with 2 or 3 employees.

One pump distributor described the parts pirates:

“these bootleggers are everywhere. Most were once pump repair service people

who saw the prices, profit and potential in the parts side of this business. They also

know where all the pumps are in the area. They sell to anyone. They literally have

little over their heads; often there is only an old barn or open shed with a roof to

shelter them from the sun. They play havoc with parts prices. We can’t buy parts

from FPC at the prices the parts pirates sell them for and still make an attractive

profit.”

The parts pirates were in many cases producing at 50-60% below FPC’s current costs, and an

increasing number of their parts were of excellent quality. A small number of the parts

pirates in the oil fields were beginning to do ump repair work, often working through the

night or the entire weekend to put a pump back in operation for an oil producer.

Since these independent parts suppliers were low-cost producers, they sold most of their

output to distributors at prices that were 30-50% below the prices distributors paid the 5

major producers. The pirates published parts substitution sheets to make it easy for

distributor counter people to substitute their products for the manufacturer’s items. The

situation encouraged many FPC distributors to stick with the lower-priced parts as well. The

pump producers often “shared the shelf” with competitive parts producers. FPC had no

policy or position on this common occurrence.

version 2 (type edits only) 9

Packing was €150 - €180 per pump. Every 2 or 3 years a major overhaul was usually needed.

Over a conservative 20-year pump life, it was common for the parts cost to be 2 or 3 times

the initial purchase cost.

Historically, all the major manufacturers of high-pressure injection pumps neglected the

parts market. As one FPC distributor stated:

“ The previous management at FPC was more interested in selling pumps or

metal tonnage rather than pursuing parts. Some producers saw the pump parts

business as a nuisance, and therefore let in the parts pirates. I never understood

why they all favoured the higher revenue but lower profit margin pump business

over the higher margin parts business”

Franz Hoffer is the manager of the aftermarket parts business. He is 59 years old and was an

FPC salesman for 29 years before taking this position. Hoffer is also independently wealthy

from the sale of his FPC stock in 1995 to the group of investors.

Parts ‘Pirates’

The higher profit margin in parts, the large pump population needing parts, and neglect by

the major pump producers attracted a large number of parts pirates to the injection pump

business. Only a few of the parts were protected by patents in various markets. Many pirates

were previously employed in the machine shops or sales areas of the pump sales and service

distributors. It was easy to enter the parts market, since it only required a machining tool,

usually a used one, and a small inventory of metal stock from which to machine parts. Most

were located in the centre of major oil field areas in simple structures with 2 or 3 employees.

One pump distributor described the parts pirates:

“these bootleggers are everywhere. Most were once pump repair service people

who saw the prices, profit and potential in the parts side of this business. They also

know where all the pumps are in the area. They sell to anyone. They literally have

little over their heads; often there is only an old barn or open shed with a roof to

shelter them from the sun. They play havoc with parts prices. We can’t buy parts

from FPC at the prices the parts pirates sell them for and still make an attractive

profit.”

The parts pirates were in many cases producing at 50-60% below FPC’s current costs, and an

increasing number of their parts were of excellent quality. A small number of the parts

pirates in the oil fields were beginning to do ump repair work, often working through the

night or the entire weekend to put a pump back in operation for an oil producer.

Since these independent parts suppliers were low-cost producers, they sold most of their

output to distributors at prices that were 30-50% below the prices distributors paid the 5

major producers. The pirates published parts substitution sheets to make it easy for

distributor counter people to substitute their products for the manufacturer’s items. The

situation encouraged many FPC distributors to stick with the lower-priced parts as well. The

pump producers often “shared the shelf” with competitive parts producers. FPC had no

policy or position on this common occurrence.

version 2 (type edits only) 9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The independent parts producers sold to 3 types of accounts. The bulk of their production

was sold to the same specialty pump producers FPC sold its pumps through. The parts

producers also sold a significant amount of their output to the 5 injection pressure pump

manufacturers. Finally, a small but increasing amount of the high-volume parts were sold by

the independents to the oil field supply houses. The oil field supply houses were considered

general stores in the oil production field, selling a wide range of maintenance and supply

items. They did little repair work and were essentially similar to a “walk-in auto supply

distributor”. Pump salespeople referred to the supply houses as “rope, dope and soap

stores”. FPC did not sell parts directly to the supply houses, but rather sold to its

distributors, who in turn were supposed to resell the high-volume items to the supply

houses. Some FPC distributors sold parts to supply houses on a consignment basis. When

Greta Klaus asked one FPC distributor why he sold parts to supply houses on consignment,

the distributor stated:

“It’s nice to have samples of what you’re selling. They only have our more popular

parts. They usually sell the samples and then we ship them more. This is no different

than what your non-stocking distributors do when they repeatedly sell the pump

demos you give them on consignment…”

The FPC distributors made relatively few parts sales to the supply houses. Since the FPC

distributors did not separately report pump and parts sales by account to FPC, the precise

amount of distributor sales of parts to supply houses was unknown.

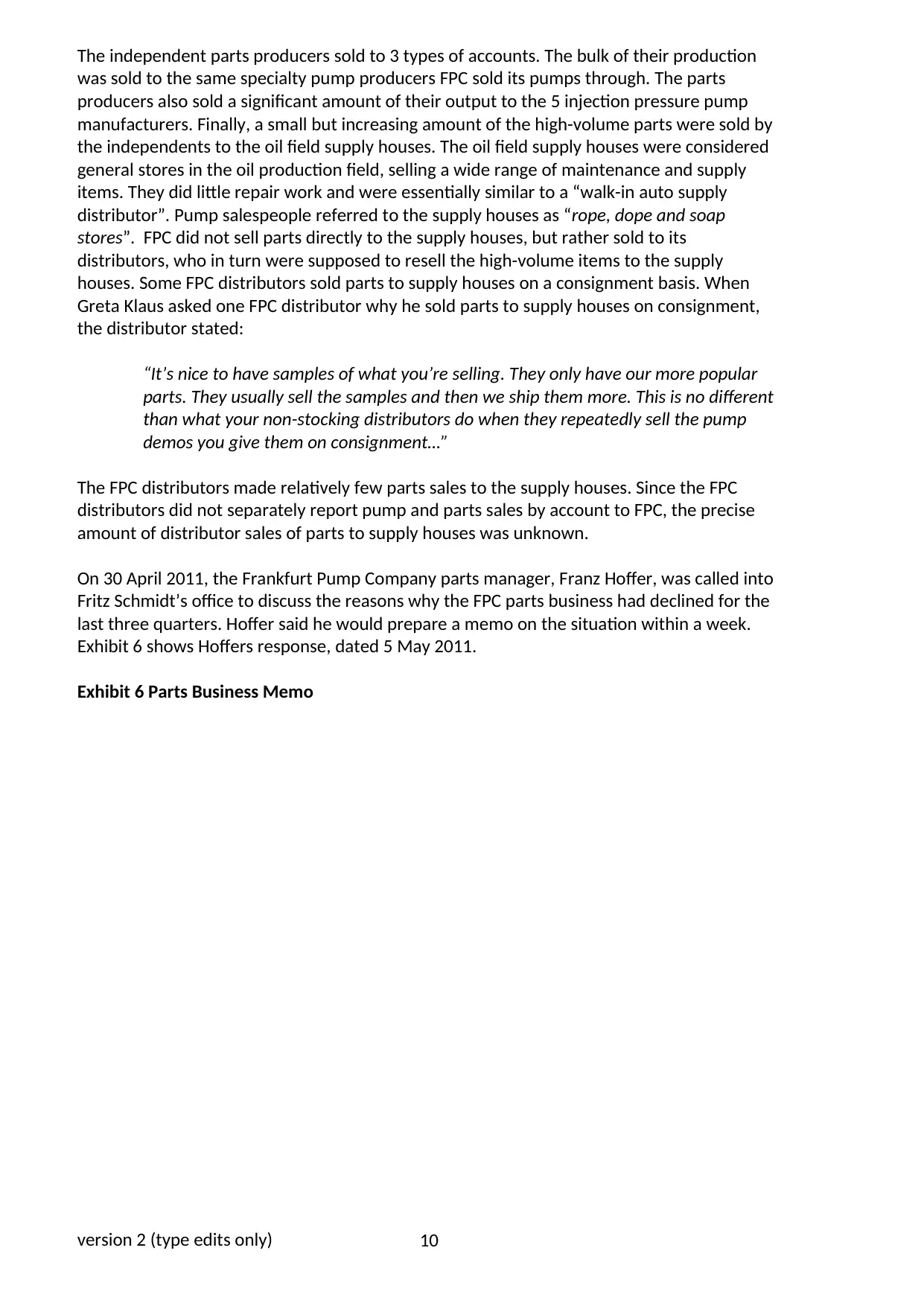

On 30 April 2011, the Frankfurt Pump Company parts manager, Franz Hoffer, was called into

Fritz Schmidt’s office to discuss the reasons why the FPC parts business had declined for the

last three quarters. Hoffer said he would prepare a memo on the situation within a week.

Exhibit 6 shows Hoffers response, dated 5 May 2011.

Exhibit 6 Parts Business Memo

version 2 (type edits only) 10

was sold to the same specialty pump producers FPC sold its pumps through. The parts

producers also sold a significant amount of their output to the 5 injection pressure pump

manufacturers. Finally, a small but increasing amount of the high-volume parts were sold by

the independents to the oil field supply houses. The oil field supply houses were considered

general stores in the oil production field, selling a wide range of maintenance and supply

items. They did little repair work and were essentially similar to a “walk-in auto supply

distributor”. Pump salespeople referred to the supply houses as “rope, dope and soap

stores”. FPC did not sell parts directly to the supply houses, but rather sold to its

distributors, who in turn were supposed to resell the high-volume items to the supply

houses. Some FPC distributors sold parts to supply houses on a consignment basis. When

Greta Klaus asked one FPC distributor why he sold parts to supply houses on consignment,

the distributor stated:

“It’s nice to have samples of what you’re selling. They only have our more popular

parts. They usually sell the samples and then we ship them more. This is no different

than what your non-stocking distributors do when they repeatedly sell the pump

demos you give them on consignment…”

The FPC distributors made relatively few parts sales to the supply houses. Since the FPC

distributors did not separately report pump and parts sales by account to FPC, the precise

amount of distributor sales of parts to supply houses was unknown.

On 30 April 2011, the Frankfurt Pump Company parts manager, Franz Hoffer, was called into

Fritz Schmidt’s office to discuss the reasons why the FPC parts business had declined for the

last three quarters. Hoffer said he would prepare a memo on the situation within a week.

Exhibit 6 shows Hoffers response, dated 5 May 2011.

Exhibit 6 Parts Business Memo

version 2 (type edits only) 10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5. DISTRIBUTION

FPC Sales Force

FPC GmbH had 6 salespeople who were responsible for both the pumps and parts sales in

their territories. The 6 were based in St.Petersburg, Russia; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Edinburgh,

Scotland; Jakarta, Indonesia; Mexico City, Mexico; Dallas, Texas USA. They were also

responsible for sales through distributors and sales served direct by FPC’s factory. The

salespeople spent most of their time calling on the direct accounts. They sometimes helped

FPC’s pump distributors call on end-use customers. FPC did not have an established policy

regarding which accounts should be sold direct or through a distributor. If a distributor

located a customer whose technical problems it was not able to solve or one geographically

outside its area, FPC did not compensate the distributor for the lead. FPC’s Scottish salesman

said:

version 2 (type edits only) 11

FPC Sales Force

FPC GmbH had 6 salespeople who were responsible for both the pumps and parts sales in

their territories. The 6 were based in St.Petersburg, Russia; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Edinburgh,

Scotland; Jakarta, Indonesia; Mexico City, Mexico; Dallas, Texas USA. They were also

responsible for sales through distributors and sales served direct by FPC’s factory. The

salespeople spent most of their time calling on the direct accounts. They sometimes helped

FPC’s pump distributors call on end-use customers. FPC did not have an established policy

regarding which accounts should be sold direct or through a distributor. If a distributor

located a customer whose technical problems it was not able to solve or one geographically

outside its area, FPC did not compensate the distributor for the lead. FPC’s Scottish salesman

said:

version 2 (type edits only) 11

“It really angers the distributors when we sell any account direct or don’t pay

them for a sale outside their geographic area. It causes some distributors to play

down our line and not pass on leads to us when they are not in their territory.

However, FPC does not have a history of taking a distributor account and selling

it direct. But an OEM, regardless of its annual purchase, can approach FPC and

usually be sold direct. There is no set rule.”

It took about 7-10 months for a new salesperson to learn the FPC line and trouble-shooting

expertise in oil and gas applications. The FPC salespeople were considered good trouble-

shooters and were known for constructing excellent technical seminars for design engineers

and maintenance personnel. The salespeople were paid on a combined base and

commission schedule for pump sales. The sale of parts was not in the quote or compensation

plan. Their quotas were set every year on aggregate pump sales, whether they were sold

through distributors or direct. FPC’s salespeople were paid a commission on what the

distributor bought. Some distributors believed this compensation method encouraged the

salespeople to overload distributors with pump inventories. Most of FPC’s stocking

distributors had large inventories. The marketing manager, division general manager and

marketing engineer each spent 15-20% of his or her time in the field working with customers

and distributors.

The FPC salespeople spent most of their time with direct OEM accounts. The marketing

manager, Greta Klaus, believes there was a need for a sales incentive system for both pumps

and parts, but she was not sure what the percentage should be between the two.

Pump Distributors

Greta Klaus described the typical FPC distributor as follows:

“Since FPC makes a high-quality technical pump, we need very specialized

distributors. These guys are both systems fabricators and component and parts

distributors. They provide engineering, fabrication, parts, replacement units, and

repair service for oil and gas operators. They can build a system for the customer

or sell the components to end users. They put the pumps, torque converters,

clutches, couplings, drive unit and controls on a platform or skid. They also sell

compressors, diesel and electric engines, and all that is needed to build the

system. Our pump distributors have engineers who go in and evaluate an end

user’s requirements and specifications before submitting a price quotation. The

fabricators, engineers and draftsmen work closely with the customer in all stages

of a job. Every situation is carefully analysed to assure that the proper

components are on the skid.

The fabricator’s engineers prepare a schematic flow and bills of material for each

job. On more complex projects, in-depth conferences are held between the

client’s engineering personnel and the fabricator’s engineers. The distributors

usually have testing facilities to test and break in the completed system.”

The speciality distributors usually had 1-3 outside salespeople and an inside salesperson. All

had a parts counter for walk-in business. One distributor described its business as follows:

version 2 (type edits only) 12

them for a sale outside their geographic area. It causes some distributors to play

down our line and not pass on leads to us when they are not in their territory.

However, FPC does not have a history of taking a distributor account and selling

it direct. But an OEM, regardless of its annual purchase, can approach FPC and

usually be sold direct. There is no set rule.”

It took about 7-10 months for a new salesperson to learn the FPC line and trouble-shooting

expertise in oil and gas applications. The FPC salespeople were considered good trouble-

shooters and were known for constructing excellent technical seminars for design engineers

and maintenance personnel. The salespeople were paid on a combined base and

commission schedule for pump sales. The sale of parts was not in the quote or compensation

plan. Their quotas were set every year on aggregate pump sales, whether they were sold

through distributors or direct. FPC’s salespeople were paid a commission on what the

distributor bought. Some distributors believed this compensation method encouraged the

salespeople to overload distributors with pump inventories. Most of FPC’s stocking

distributors had large inventories. The marketing manager, division general manager and

marketing engineer each spent 15-20% of his or her time in the field working with customers

and distributors.

The FPC salespeople spent most of their time with direct OEM accounts. The marketing

manager, Greta Klaus, believes there was a need for a sales incentive system for both pumps

and parts, but she was not sure what the percentage should be between the two.

Pump Distributors

Greta Klaus described the typical FPC distributor as follows:

“Since FPC makes a high-quality technical pump, we need very specialized

distributors. These guys are both systems fabricators and component and parts

distributors. They provide engineering, fabrication, parts, replacement units, and

repair service for oil and gas operators. They can build a system for the customer

or sell the components to end users. They put the pumps, torque converters,

clutches, couplings, drive unit and controls on a platform or skid. They also sell

compressors, diesel and electric engines, and all that is needed to build the

system. Our pump distributors have engineers who go in and evaluate an end

user’s requirements and specifications before submitting a price quotation. The

fabricators, engineers and draftsmen work closely with the customer in all stages

of a job. Every situation is carefully analysed to assure that the proper

components are on the skid.

The fabricator’s engineers prepare a schematic flow and bills of material for each

job. On more complex projects, in-depth conferences are held between the

client’s engineering personnel and the fabricator’s engineers. The distributors

usually have testing facilities to test and break in the completed system.”

The speciality distributors usually had 1-3 outside salespeople and an inside salesperson. All

had a parts counter for walk-in business. One distributor described its business as follows:

version 2 (type edits only) 12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 18

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.