Research on Coping Strategies and Anxiety in Nurses during COVID-19

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/15

of Nurses during COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

This research aimed to investigate the effects of coping strategies on nurses' anxiety levels

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety is defined as "a disordered condition" of the body's

emotional sensitivity. During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, nurses in

COVID-19 wards, emergency departments, and fever clinics have served as healthcare system

gatekeepers while risking their own and families’ health and lives. Uncertain situations, working

for long hours, and fear of contracting the disease have increased the nurses' anxiety level. The

nurses serving in the COVID and emergency wards use several coping strategies to overcome

their anxiety. It is vital to understand the correlation between the coping strategies used by the

nurses and their anxiety levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. For this purpose, this study

employed a cross-sectional design and used Brief-COPE and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) for

data collection. The study sample consisted of 404 nurses working in the COVID-19 wards in 10

UK hospitals. The data was collected online and analysed with the help of SPSS (v. 25) by

running descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation analysis, and Regression analysis for

determining the relationship among the study variables. The study findings revealed that the

nurses' most commonly used coping strategy is problem-focused coping to overcome and bring

down their anxiety levels. Further results showed a positive relationship between the three

sub-scales of managing (problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping and avoidant coping)

and the nurses’ anxiety levels during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1

Paraphrase This Document

Abstract.......................................................................................................................................................1

Chapter One: Introduction...........................................................................................................................4

1.1Introduction and Background ............................................................................................................4

1.2 Rationale of the Research .................................................................................................................8

1.3 Research Aim, Objectives & Question................................................................................................8

1.4 Theoretical Framework......................................................................................................................9

1.5 Study Hypotheses..............................................................................................................................9

1.6 Outline of the Dissertation...............................................................................................................10

Chapter Two: Literature Review................................................................................................................10

2.1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................11

2.2 Anxiety.............................................................................................................................................11

2.3 Anxiety amongst Healthcare Professionals during COVID-19..........................................................13

2.4 Anxiety Levels of Nurses during COVID-19.......................................................................................16

2.5 Coping Strategies.............................................................................................................................18

2.5.1 Usage of COVID-19 protective measures .................................................................................18

2.5.2 Avoidance coping......................................................................................................................19

2.5.3 Role of social support................................................................................................................20

2.5.4 Faith-based practices................................................................................................................20

2.5.5 Psychological support...............................................................................................................21

2.5.6 Managerial support...................................................................................................................22

2.6 Research Gap...................................................................................................................................22

Chapter Three: Methods...........................................................................................................................23

3.1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................23

3.2 Study Design....................................................................................................................................24

3.3 Study Participants ...........................................................................................................................24

3.4 Research Tools.................................................................................................................................24

3.4.1Demographic questionnaire......................................................................................................24

3.4.3Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-Cope) (Dias et al., 2012)...........25

3.5 Procedure........................................................................................................................................26

3.6 Data Analysis....................................................................................................................................27

3.7 Ethical Considerations......................................................................................................................27

Chapter Four: Results................................................................................................................................28

4.1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................28

2

4.3 Demographic Results.......................................................................................................................29

4.4 Descriptive Statistics........................................................................................................................30

4.5 Inferential Analysis...........................................................................................................................35

4.5.1 Analysis of correlation between Brief-COPE (Coping Strategies) and SAS (Anxiety levels).......35

Chapter Five: Discussion............................................................................................................................38

5.1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................38

4.2 Discussion of Findings......................................................................................................................38

Chapter Six: Implications...........................................................................................................................46

6.1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................46

6.2 Implications.....................................................................................................................................46

6.2.1 Implications for theory..............................................................................................................46

6.2.1 Implications for nursing management......................................................................................47

6.3 Recommendations...........................................................................................................................48

Chapter Seven: Conclusion........................................................................................................................50

7.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................50

7.2 Summary of Research......................................................................................................................50

7.3 Limitations and Future Research Suggestions .................................................................................52

References ................................................................................................................................................53

Appendices................................................................................................................................................62

Appendix A............................................................................................................................................62

Demographic questionnaire..................................................................................................................62

Appendix B.................................................................................................................................................65

Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS)..........................................................................................................65

Appendix C.................................................................................................................................................66

Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-Cope).......................................................66

Chapter One: Introduction

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The outbreak of COVID-19 in December 2019 has been associated with innumerable challenges,

especially to the healthcare workers, as they occupy the frontline in dealing with COVID-19 pandemics

and are at increased risk of burdens led by COVID-19. Cases of mental health issues among these groups

of individuals are associated with the excessive workload and risk of transmitting the disease during

healthcare pandemics (World Health Organization [WHO] 2020a.) Unpreparedness to handle the surging

cases of the pandemic and emotional distress associated with the fear of infection concerns include the

fact that the disease is highly contagious with a low level of knowledge on the factors surrounding the

infection. The lack of established vaccines or treatments to handle the outbreak has also been another

concern (Pappa et al. 2020) for an extended period before the introduction of vaccines.

The World Health Organisation (WHO, 2020B) reports that nurses are the most prominent health

professionals in the health sector. They play a crucial role in public health emergencies in improving

public health even though COVID-19 has put more burden on health systems, and its impact is beyond

description. Nurses’ contributions and vigilance in health promotion during epidemic outbreaks like

influenza, Ebola, and Zika were seen in the past years. Currently, nurses are at the forefront of caring for

COVID-19 patients in acute care settings (WHO, 2020b.) In addition, they have been engaged together

with the interprofessional sectors, teams, and communities in this global pandemic preparedness and

response (American Academy of Nursing, 2018).

Nurses have proved to be the more excellent asset. In the past decades, nurses have been on the

frontline during major hits of infectious disease outbreaks, including “H1N1, Swine Flu, Severe Acute

Respiratory Syndrome SARS, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Ebola” (Ruiz-Fernandez et

al., 2020, p. 4321). Similarly, the study done by Jung and Jun (2020) has found that nurses have always

been the front liners and role models in infection control and prevention practices and public health

promotion. It has become apparent that nurses work all around the clock to provide hospital care to the

affected ones. Public health nurses are shifted to acute care settings. They lead a response team,

demonstrating skills and expertise in emergency preparedness, predictive modelling, hospital, and field

operations to deal with the pandemic. However, they are not exempted from experiencing accidental

outcomes such as exposure to outbreaks, occupational stress, lethargy, psychological fatigue, and

trauma (Jung & Jun 2020).

4

Paraphrase This Document

the disease globally, resulting in 1.9 million deaths worldwide. In Mexico, 21% of nurses have been

infected with COVID-19, whereas 45% were infected with COVID-19 in Iran. Both countries were hardly

hit by COVID-19, shown by the report of ICN (2021). Research has shown that at least 1 in 5 healthcare

workers are showing signs of depression and anxiety, whereas 4 in 10 workers are experiencing

insomnia and a higher rate of anxiety and depression among the female nursing staff and health workers

(Pappa et al., 2020).

According to a systematic literature review conducted by Pappa et al. (2020), “the uneven and increased

distribution of workload, physical exhaustion, lack of personal protective equipment, nosocomial

transmission” as well as “the need to make ethically difficult decisions on the rationing of care” have

posed a tremendous impact on “the physical and mental well-being of nurses” (p. 902). Isolation and

loss of social support, risks of infecting loved ones and relatives as well as rapid changes in the working

environment can further compromise the resilience of nurses leading them to be at a higher risk of

experiencing a variety of psychological effects, including “acute stress disorder, depression, post-

traumatic stress disorder, insomnia, irritability, anger, and emotional exhaustion following disease

outbreak” (Pappa et al., 2020, p. 902).

Ruiz-Fernandez et al. (2020) discovered that “the prevalence of depression (nurses: 30.30 percent vs.

physicians: 25.37 percent) and anxiety (nurses: 25.80 percent vs. doctors: 21.73 percent)” was

substantially greater among nurses in comparison to doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic (p. 4321).

Previous research has indicated that continuous usage of protective equipment, such as “surgical masks,

gloves, goggles, face shields, gowns, and N95 masks”, might result in physical issues like “skin lesions

and de novo PPE-associated headache” (Ruiz-Fernandez et al., 2020, p. 4321). Furthermore, reported

stress symptoms include decreased appetite or dyspepsia, exhaustion, sleeplessness, anxiety, frequent

sobbing, and even suicidal thoughts. It is hardly unexpected that junior and inexperienced nurses suffer

higher stress levels. The psychological crises can and will negatively influence nurses' safety and quality

of life in the long run (Ruiz-Fernandez et al., 2020).

It is essential to understand what the theories and literature say about nurses' experiences during the

crisis. Crisis refers to a decisive stage that bears critical consequences in the future of an individual or a

system. It also refers to an event or a situation perceived as an intolerable difficulty that exceeds

individuals' or people's available resources and coping mechanisms (Yeager & Roberts, 2015). Theories

have been used to explain nurses' and other healthcare professionals’ handling and managing the

5

was studied by various psychologists who came up with psychodynamic theories. They believed that

depression and other mental health issues resulted from inwardly directed anger, severe superego

demands, and the loss of self-esteem, among others. The psychodynamic theories handle a variety of

human behaviors and reactions to various issues affecting their day-to-day lives (Marčinko et al., 2020).

The psychodynamic processes are critical in gaining an in-depth understanding necessary for managing

individual and group mental health issues in times of crisis. Psychodynamic theories are being applied to

explain the general population's reaction to the current coronavirus pandemic situation. These include a

clearer understanding of behaviors such as spreading panic, stigmatization, defensive responses, and

socially disruptive behavior in times of such pandemics (Uji, 2020).

Csikszentmihalyi and Seligman (2000) defined positive psychology as a positive subjective experience

that builds positive individual qualities. The four personality traits that contribute to “positive

psychology are subjective well-being, optimism, happiness, and self-determination” (p. 6). These

subjective experiences refer to “what people think and how they feel about their lives to the cognitive

and affective conclusions they reach when they evaluate their existence” (Csikszentmihalyi & Seligman,

2000, p. 6). Positive psychology is different from humanistic psychology in that positive psychology

observes both strength and weakness as authentic and responsive to scientific understanding as

described by (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

The “need for competence, belongingness, and autonomy” are central to the self-determination theory

and are investigated within the approach. Researchers claim that personal well-being and social

development are greatly optimized (Csikszentmihalyi & Seligman, 2000, p. 6). Optimism is more involved

in cognitive, emotional, and motivational components, according to the article published by Peterson

(2000).

When viewed from the perspective of positive psychology, an optimistic employee has more likelihood

of practicing good habits and work ethics that promote their self-development than a pessimistic one.

Positive psychology is used in preventative and therapeutic strategies that promote positive traits,

creating positive subjective experiences. These experiences can be achieved through resilience. Fear of

uncertainty can lead to anxiety or depression among workers. Positivity builds strength and creates

solutions to the problems by opening the awareness level. Positive psychology helps the healthcare

worker become more resilient and persistent (Csikszentmihalyi & Seligman, 2000).

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

healthcare workers. For safe and continuous patient care, nurses´ health and safety play a crucial role in

controlling any disease outbreak. However, healthcare workers are under tremendous stress and

anxiety during the current pandemic (Cabarkapa et al., 2020). Hence, comprehensive support is needed

for health care workers and nurses during the pandemic crisis.

1.2 Rationale of the Research

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an ailment caused by coronavirus that causes “severe acute

respiratory syndrome.” COVID-19 is so infectious that by January 2022, it has infected over 298 million

individuals and killed over 5.47 million people worldwide. A significant frequency of a contagious viral

illness will strain any healthcare system and its employees. Healthcare personnel are in danger of

jeopardizing their health, catching the disease, and possibly becoming a source of disease in their

community while performing their professional tasks. The physical hazards are exacerbated by the

concurrent risk of mental health disorders. It is a terrible reality that more than 180,000 healthcare

professionals have died due to the coronavirus globally. Nurses on the front lines of giving life-saving

treatment to COVID-19 patients are at a significantly increased risk of mass traumatization. Their

psychological stress and anxiety are increasingly acknowledged as significant issues. Nurses face

enormous physical and mental stress and anxiety as a result of physical tiredness from “increased

workload,” the danger of transmitting the virus, particularly with an insufficient supply of “personal

protective equipment (PPE),” and the ethical quandary of “triaging patient care.” In response to the

COVID-19, millions of nurses work as COVID-19 front liners. A considerable proportion of nurses are in

psychological turmoil during outbreaks; hence there is an urgent need to establish support mechanisms

and enhance the possible interventions for the holistic well-being of nurses during the pandemic

situation. Therefore, understanding the burdens of COVID-19 and nurses' experiences during the

outbreak is crucial in policy formulation and interventions for maintaining their health and well-being.

1.3 Research Aim, Objectives & Question

The current research aimed to investigate the effects of coping strategies on nurses' anxiety levels

during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim was met by addressing the following research objectives:

7

Paraphrase This Document

2. To study the strategies adopted by the nurses to cope with the pandemic induced anxiety

3. To determine the correlation between the anxiety levels and coping strategies adopted by the

nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic

This study attempted to answer the following research question “What are the effects of coping

strategies adopted by the nurses on their anxiety levels during the COVID-19 pandemic?”

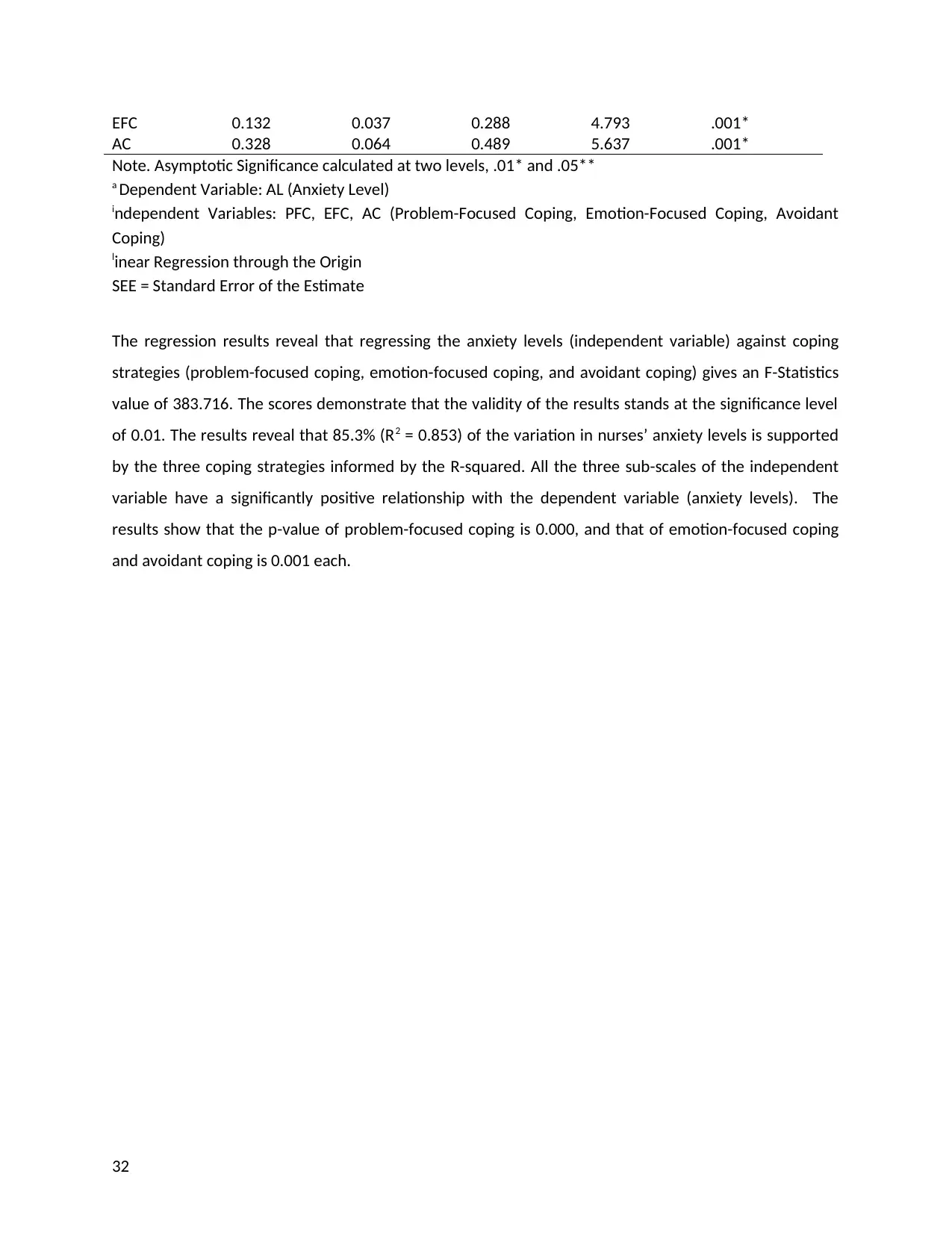

1.4 Theoretical Framework

The following figure presents the theoretical framework of this study. The correlation between overall

coping strategies (and the three sub-scales of coping strategies) and nurses’ anxiety levels was tested to

determine the effects of the coping strategies used by the nurses on their anxiety levels during the

COVID-19 pandemic. Coping strategies (“problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and

avoidant coping”) were the independent variable, and anxiety levels were the study's dependent

variable.

Figure 1.1 Theoretical framework

1.5 Study Hypotheses

The study attempted to test the following null hypothesis:

H0 = There is no effect of coping strategies on anxiety levels of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic

The study also tested the following alternate hypotheses

H1= The use of problem-focused coping has a positive correlation with the anxiety levels of nurses during

the COVID-19 pandemic

H2= The use of emotion-focused coping has a positive correlation with the anxiety levels of nurses during

the COVID-19 pandemic

8

COVID-19 pandemic

The use of (specific) coping strategies will correlate with lowering anxiety levels and vice versa.

1.6 Outline of the Dissertation

Chapter one has provided a background to the study; study rationale; theoretical framework; research

aim, objectives, and question; and an outline of the dissertation. Chapter two consists of a review of the

existing literature on the research problem and ends at identifying a research gap that will be filled by

meeting the objectives of the current study. Chapter three offers an account of the decisions made by

the researcher regarding the way the research was conducted, that is, research methods. The chapter

includes sections on the justification for research design, study population and sample size, research

instrument, an explanation of the research process, and a discussion of ethical aspects and reliability

and validity.

Chapter four presents the results of the study. Chapter five consists of a discussion on the findings of the

study. The implications of the study findings are examined in the context of the discipline in chapter six.

Implications for theory, policy, and practice are addressed, and policy and practice recommendations

are in chapter six. Chapter seven includes a critical examination of the study’s limitations and

suggestions for future research.

Chapter Two: Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

Since this study is concerned with anxiety levels and coping strategies employed by nurses during the

COVID-19 pandemic, this chapter begins with an elucidation of the notion of anxiety. It explores how

this phenomenon affects healthcare professionals during COVID-19 in general. The chapter then heads

on to look at nurses' anxiety levels during COVID-19. Finally, the coping strategies utilized by the nurses

to overcome anxiety are discussed in the light of existing literature on the notion. The chapter ends with

identifying a research gap that will be filled by addressing the objectives of the current study.

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Anxiety has been defined in a variety of ways, such as “a disturbed state” of the body’s emotional

reactivity (Johnson, 1951), arousal (Skubic, 1986), nervousness (Ekegami, 1970), neuroticism (Kane,

1970; Pikunas, 1969) unrealistic and unpleasant state of body and mind. In medical, terminology anxiety

is defined as “apprehension of danger accompanied by restlessness and feelings of oppression in the

epigastrium” (Crooks & Stein, 1988). A variety of psychological reactions such as increased heart rate,

rapid shallow berating, sweating, muscles tension, and drying of the mouth are associated with anxiety.

Fear and anxiety differ in one crucial respect that is “Fear has an obvious cause, and once that cause is

eliminated, the fear will subside; in contrast, anxiety is less clearly linked to specific events or stimuli.”

Therefore, it tends to be more pervasive and less responsive to environmental changes (Crooks & Stein,

1988).

Fear is usually defined as a rational, emotional reaction to danger or the anticipation of danger or harm

from a real objective stimulus in the external environment. Moreover, the magnitude of fear is directly

proportional to the amount of risk that evokes it that may be unknown to others. Furthermore, the

intensity of anxiety after the danger has been objectively measured. Pressure has a variety of types,

such as “trait anxiety, state anxiety manifest anxiety, chronic anxiety specific anxiety,” etc. Spielberger

(1966) was the first anxiety theorist to differentiate between state anxiety and trait anxiety. Burton

(1976) and Martens (1971) also supported these concepts.

Anxiety can emerge at various times about the presence of a potentially stressful situation. As an

emotional reaction, anxiety is innate and plays a crucial role in shaping human behavior. Lingis (1976)

argues that in all anxious anticipation “there is a sense of void” which produces a sense of vulnerability

(the bases for distress) as well as (a level of exhilaration). Anxiety therefore, is understood not as “a solid

core of substance” but as “a current of forces assembling and dissipating itself”. Anxiety has extremely

wide dimension as is clear from various definitions given, above. Like any other emotion, anxiety is a

psycho-physiological phenomenon on the one end of which lie numerous physiological actions reactions

raising the arousal and activation level of the body and on the other, stands, a feeling tone, a cognitive

state having far reaching consequences and effect on human psyche, seen as a mental label.

10

Paraphrase This Document

true, we cannot escape this notion because of the vital physiological changes during anxiety. Anxiety is

documented primarily as a psychological state; it nevertheless has such psychological indices as dry

mouth, clum palms, wet forehand, increased cardio-reaction, reaction faster metabolic activity, etc.

Anxiety affects the psychological and physiological working of organisms in numerous ways. Anxious

people, for example, are considered to have poor attention management. During heightened activity

(including anxiety), attention cannot be focused on a single component of the organism's movement,

which is chaotic and intense. Anxiety typically leads to a narrowing of the field of attention when

significant stimuli are ignored, which influences the individual's judgment. Loss of knowledge appears to

be processed by people experiencing immediate (state) anxiety or whose underlying personality system

is characterized by high levels of trait anxiety (Cratly, 1989).

Anxious people have been observed to be tight or highly strung. As a result, their performance in

activities requiring precise neuromuscular coordination is significantly worse than that of less worried

people and functions in a tension-free state of body and mind. Anxiety, in a nutshell, impairs muscle

function. Cratly (1989) correctly concludes that "anxiety" is not a physical vacuum but a complex of

sentiments, including low self-esteem, helplessness, sadness, or violent thoughts and acts. The chronic

destructive emotion associated with worry and psychological turmoil (an unavoidable effect of high

anxiety syndrome) eventually leads to psycho-somatic diseases. Logically equanimity between activation

arousal and anxiety may be convincing; realistically, it is not because anxiety is a much more complex

phenomenon than the body's general activation arousal physiological state.

Fear of the unknown raises anxiety in those with pre-existing mental health disorders and healthy

people. For example, “the 2001 anthrax letter assaults in the United States” resulted in psychological

illnesses and lowered public impression of infected personnel and responders’ health (North et al.,

2009). According to the Covid-19 mental health repercussions estimates, people’s emotional responses

would most likely consist of doubt and dread. Furthermore, undesirable social behaviors would typically

be motivated by inaccurate perceptions of danger and fear (Shigemura et al., 2020). These experiences

may lead to a wide range of public mental health concerns, such as “distress reactions (such as anger,

insomnia, or fear of illness even in those who have not been exposed), health risk behaviors (such as

social isolation or alcohol and tobacco abuse),” mental health disorders (such as anxiety disorders, post-

traumatic stress disorder, or stress), and lower perceived health (Shigemura et al., 2020).

11

The COVID-19 epidemic in December 2019 has been linked to a slew of issues, particularly for healthcare

personnel. They are on the front lines of dealing with COVID-19 pandemics and are more vulnerable to

COVID-19-related detriments. Cases of mental health issues among these groups of individuals are

associated with the excessive workload during healthcare pandemics (WHO, 2020a). Unpreparedness to

handle the surging cases of the pandemic and emotional distress related to the fear of infection

concerns include the fact that the disease is highly contagious with a low level of knowledge on the

factors surrounding the infection (Pappa et al. 2020).

Disease outbreaks, like the COVID-19 pandemic, are stressful events. Defined as a “state of uneasiness

or apprehension resulting from the anticipation of a real or perceived threatening event or situation”

(Spielberger, 2010, p. 1), during pandemics, anxiety is widespread among healthcare staff who are

directly involved in the care of infected patients. Furthermore, because of their direct interaction with

COVID-19 patients, healthcare providers are more vulnerable to “traumatic events such as patients’

suffering and death” (Pappa et al., 2020), which may exacerbate their anxiety. According to available

data, the prevalence of anxiety among healthcare providers varied from “22.6 to 36.3 percent” (Liu et

al., 2020), which was substantially higher than the general population. Nurses were shown to have the

most significant “anxiety levels and the highest prevalence of anxiety” among HCWs, ranging from “15%

to 92 percent” (Alwani et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). Anxiety levels were shown to be

high in multiple published research, specifically among female nurses (Alwani et al., 2020; Kaveh et al.,

2020).

During the COVID-19 epidemic, nurses were most concerned about being sick or unwittingly infecting

others (Mo et al., 2020). Other sources of anxiety amongst nurses were identified by Shanafelt et al.

(2020), including “a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), a fear of harboring the novel

coronavirus at work, a lack of access to COVID-19 testing, a fear of transmitting the virus at work, doubt

that their institution would support them if they became infected, a lack of access to childcare facilities

during the lockdown, a fear of being deployed in an unfamiliar ward or unit, and lack of accurate

information regarding the disease” (p. 2133).

Maintaining a well-engaged nursing staff is critical by implementing steps to decrease nurse anxiety and

its negative implications. Whereas a low level of fear might inspire and elicit enthusiasm in a person,

prolonged anxiety exposure can harm their physiopsychological health and work performance.

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

disturbances, and vomiting or nausea (e.g., Lee, 2020). Increased anxiety has also been linked to

impairment in several physical processes, “poor coping techniques (such as increased alcohol or drug

consumption), stress and sadness, and increased suicidal thoughts” (Lee et al., 2020). Moreover,

untreated anxiety can have a long-term impact on a nurse’s “work performance and job satisfaction”

that can lead to frequent absences and ultimate expenses (Labrague et al., 2018a; Lee et al., 2020).

It is critical to assist nurses in their “mental, psychological, and emotional health,” using evidence-based

strategies to successfully manage their worries or anxieties about COVID-19 (Catton, 2020). Nurses have

recognized “personal resilience and social and organizational support as critical variables in coping with

hardship and stress, helping them to preserve their mental and psychological health.” The ability of “a

person to 'bounce back' or recover quickly from a specific event, such as the COVID-19 pandemic”

(Cooper et al., 2020), as well as “support from colleagues, managers, friends, families, and the

organization” (Maben & Bridges, 2020, n.p.), can assist nurses in coping with the pandemic's burden.

However, no research has been done to see if and how coping strategies of problem-focused coping,

emotion-focused coping, and avoidant coping affect nurses’ anxiety levels. As a result, this research

aimed to investigate the causal links between these variables.

Many healthcare professionals are vulnerable to infection and mental health issues during an epidemic

of a new infectious illness (Xiang et al., 2020), as seen by the 2003 SARS outbreak. Nonetheless, given

that the Covid-19 pandemic is a worldwide phenomenon, it appears that paying attention to those

possible mental health issues is even more critical. Given the prevalence of mental health concerns that

arose during the 2003 SARS outbreak, China's National Health Commission issued a notification on

January 26, 2020, outlining the core principles for emergency psychological crisis treatments for the

Covid-19 (National Health Commission of China, 2020). Mental health treatments should be offered not

just for “patients with Covid-19 pneumonitis, close contacts, and suspected instances isolated at home,

but also for health professionals”, according to the notification. In the context of the Covid-19 epidemic,

it is critical to offer precise information to health professionals, including “regular and accurate updates

on the outbreak,” to alleviate their anxiety and concern. It's also critical to give mental health assistance

to medical practitioners (de Medeiros et al., 2020, n.p.).

2.4 Anxiety Levels of Nurses during COVID-19

13

Paraphrase This Document

the health sector. They play a vital role in public health emergencies in improving public health, even

though COVID-19 has put more burden on health systems, and its impact is beyond description. Nurses'

contributions and vigilance in health promotion during epidemic outbreaks like influenza, Ebola, and

Zika were seen in the past years. Currently, nurses are at the forefront of caring for COVID-19 patients in

acute care settings (World Health Organization, 2020b.) In addition, they are engaged together with the

interprofessional sectors, teams, and communities in this global pandemic preparedness and response

(American Academy of Nursing on Policy, 2018).

The burdens of the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to have both short- and long-term impacts on

healthcare workers, even though these healthcare workers are an essential asset and infrastructure of

the health sector. For safe and continuous patient care, nurses´ health and safety play a crucial role in

controlling any disease outbreak. However, healthcare workers are under tremendous stress and

anxiety during the current pandemic (Cabarkapa et al., 2020). Nurses are at high risk because of their

essential role in COVID-19 preventive and intervention activities, such as preventing, managing, and

isolating the infection. They spend a significant amount of time with patients and are on the frontlines

during this process (Choi et al., 2020; Mo et al., 2020). Nurses who work in direct contact with COVID-19

suspected or confirmed patients are under a lot of stress, even if they take safeguards ahead of time

(Cui et al., 2021). COVID-19 is more likely to infect healthcare professionals, such as nurses, than any

other group (Cui et al., 2021). COVID-19 is causing emotional and mental distress among nurses. Nurses

face not just physiological but also an insurmountable quantity of psychological challenges, resulting in

high levels of anxiety (Choi et al., 2020; Huang & Rong, 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Being vulnerable in the

face of the prospect of not only becoming sick but also infecting their family and others around them

while working in demanding settings under severe psychological stress is one of the most prominent

causes for increasing stress among nurses (Huang & Rong, 2020; Millar, 2020). Exposure to this stressful

circumstance raises the chance of death and can cause significant physical and mental health issues, as

well as behavioral difficulties (Burgdoff et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2019). This unstable

condition, in which dread and worry reign supreme, has a severe impact on job performance and the

lives of nurses.

According to a systematic literature review conducted by Pappa et al. (2020), “the uneven and increased

distribution of workload, physical exhaustion, lack of personal protective equipment, nosocomial

transmission” as well as “the need to make ethically difficult decisions on the rationing of care” have

14

social support, as well as the risk of infecting loved ones and relatives, as well as rapid changes in the

working environment, can further weaken nurses' resilience, putting them at risk for a variety of

psychological effects such as acute stress disorder, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, insomnia,

irritability, anger, and emotional exhaustion in the aftermath of a disease outbreak (Pappa et al., 2020).

Stelnicki et al. (2020) maintain that sudden changes in the nursing environment include concerns

associated with access to personal protective equipment, the risks of being exposed to the disease while

taking care of patients, and the unavailable rapid access to testing characteristics in many nations and

healthcare facilities. Uncertainties with the health care organizations and facilities' ability to take care of

nurses in case they contract the disease have also been a significant source of anxiety among nursing

professionals across the globe. Other causes of stress include the difficulties in the out-of-work lives of

nurses, such as access to childcare following the closure of schools and the increasing family and

personal needs due to increased pressure in the workplace. Nurses have also faced anxiety based on

internal arrangements in the workplace that may call for transfers into unfamiliar working spaces and

fields. It is due to the need to cover up the current gaps in the healthcare system. It is coupled with poor

access to up-to-date communication and information necessary for decision-making during patient care

(Stelnicki et al., 2020).

According to the studies of psychological and mental well-being of healthcare workers, the COVID-19

pandemic has shown an increase in anxiety, depression, and insomnia among nurses. It is associated

with an increased workload as the number of patients significantly rises, the inadequacy of personal

protective equipment, and the need to make ethical decisions despite the present dilemmas in the

workplace. These factors have been cited as typical in contributing to the mental and psychological

health issues facing nurses following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (Pappa et al., 2020). It is

likely to take a toll on the health and well-being of nurses. Fear and panic among the nursing staff have

posed a significant threat to their personal lives. As they seek to contain the pandemic and offer quality

care for all patients, nurses feel unsafe in the workplace, both physically and psychologically (Ho et al.,

2020). In the course of their duties, nurses are anxious about their own and their families' well-being.

Hence, fear and panic should be considered in nurse’s mental well-being in the management of

healthcare pandemics.

15

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The coping strategies as peer the reviewed literature used by nurses to cope with anxiety are: Usage of

COVID-19 protective measures, avoidance coping, the role of social support, faith-based practices,

psychological support, and management support.

2.5.1 Usage of COVID-19 protective measures

The employment of COVID-19 preventive measures was the first topic recognised in the literature as a

tactic nurse used during the COVID-19 pandemic. Protective measures can also be referred to as

preventative measures. The goal of these strategies is to limit the spread of COVID-19. As a result, public

cooperation with these measures is critical to managing the COVID-19 pandemic successfully, as Padidar

et al. (2021) noted. Several researchers discussed COVID-19 preventive methods (e.g., Ali et al., 2020;

Sheroun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Sheroun et al. (2020) conducted a cross-sectional online study

on nursing students. They discovered that the individuals were utilizing COVID-19 protective measures

in various ways, including “avoiding public places or events, washing or disinfecting hands more

frequently than usual, and avoiding public transportation such as buses and trains” (p. 285). Cai et al.

(2020) posit that the increased awareness of these preventative measures and a decrease in the number

of reported instances reduces the stress and anxiety of medical personnel such as nurses.

According to research conducted by Shahrour and Dardas (2020), the researchers have stressed the

need for nurse managers to actively safeguard the personal safety of their personnel by collaborating

closely with hospital administration to secure and deliver individual safety measures. Huang et al. (2020)

emphasise that the hospitals must provide “suitable medical protective equipment” and develop a wide

variety of treatments to prevent the transmission of infectious illnesses such as COVID-19 for creating “a

safe environment” in which COVID-19 can not spread. It promotes a positive environment and

safeguards nurses' safety, allowing them to continue giving the best possible patient care to win the

struggle against the COVID-19 epidemic. Contrary to this, Ali et al. (2020) found that “protective

measures” are not widely adopted as coping methods by all nurses. According to the study, only 75% of

participants reported using all stringent preventive measures, for instance, “protective gear, face masks,

and hand washing to lower their risk of infection” (p. 2057). According to Cui et al. (2021), nurses need

to be taught the techniques required to defend themselves against COVID-19. Enough comprehension of

COVID-19 might boost nurses' confidence, and adequate training must be provided (Zhang et al., 2020).

16

Paraphrase This Document

The avoidance technique was highlighted as a second theme in the literature as a method nurses utilize

in the wake of the COVID-19 epidemic. Avoidance in this context is referred to as “the act or habit of

withdrawing from or avoiding anything undesirable.” Only two reviewed papers mentioned nurses using

an avoidance strategy during the COVID-19 epidemic (Ali et al., 2020; Sheroun et al., 2020). Ali et al.

(2020) discovered that the majority of participants in an Alabama research reported: “avoiding media

coverage providing updates on COVID-19 infection and death rates” (p. 2057). However, according to Ali

et al. (2020), relying on an “avoidance strategy for nurses” may severely “limit their access to current

risk information, which may include improved research or more preventative measures” (p. 2057).

According to Sheroun et al. (2020), Erroneous news stories have also contributed to worry and panic.

2.5.3 Role of social support

Social support was recognised as a third topic in the literature reviewed by the researcher as a tactic

adopted by nurses during the COVID-19 epidemic. Social support is one of the most efficient ways for

people to cope with stressful circumstances, and according to Kim et al. (2008), it can come from a

spouse, family, friends, coworkers, or community members. Babore et al. (2020) conducted a prior study

on social support saw it as a “functional” method for dealing with difficult situations. Ali et al. (2020), Cai

et al. (2020), Gunawan et al. (2021), Shaohua et al. (2020), and Zhang et al. (2020) are five papers that

cited “social support “as a method employed by nurses for coping with the stress and anxiety during the

COVID-19 pandemic.

According to Gunawan et al. (2021), there is a need to provide support to the nurses at all times for

them to be satisfied with their work. Nurses’ stress reactions can be considerably decreased with social

backing (Shaohua et al., 2020). During the difficult stages of COVID-19, nurses, for example, place a

significant priority on family support (Cai et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Nurses are especially urged to

video connect with a loved one or get individual counseling at least once throughout their shift, as Ali et

al. (2020) reported.

2.5.4 Faith-based practices

Faith-based practices were recognised as a fourth theme in the reviewed literature as a tactic employed

by nurses during the COVID-19 epidemic. Only two of the nine publications included in the literature

17

19 outbreak (e.g., Munawar & Choudhry, 2020; Savitsky et al., 2020). To cope with the COVID-19

epidemic, “faith-based behaviors and belief systems are thought to play an important part in the lives of

health workers such as nurses” (Munawar & Choudhry, 2020, p. 289).

Coping is thought to be crucial in deciding “whether a stressful situation results in adaptive or

maladaptive effects” (Dardas & Ahmad, 2015, p. 7). Contrarily, Savitsky et al. (2020, p. 102809)

discovered that “the anxiety level of religious student nurses may increase” since living a religious

lifestyle was substantially hindered throughout the COVID-19 period due to strict limitations against

worshipping in “a mosque or synagogue and using a Mikveh (Jewish ritual bath).” The findings of the

existing studies indicate the gap that needs to be filled to aid nurses in maintaining their religious

practices and lifestyle throughout the COVID-19 epidemic.

2.5.5 Psychological support

Psychological support was highlighted as the sixth topic in the reviewed literature as a tactic utilized by

nurses during the COVID-19 epidemic. Psychological assistance alleviates emotional distress, allowing

beneficiaries to “rely on their resources sooner and cope more successfully with the challenges they

experience on the road to recovery” (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies,

2003, n.p.).

It is highlighted by Cole et al. (2020) that psychological assistance should try to treat “mental health

issues”s that have arisen as a result of trauma or other stressful events on the frontlines. Only four

papers addressed nurses using psychological assistance as a coping technique for the COVID-19

epidemic (e.g., Huang et al., 2020; Sheroun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). It was evidenced by Huang

et al. (2020) that hospitals in Anhui Province, China, “focus on providing psychological support to nurses

as well as training in coping skills” (n.p.). According to research conducted by Zhang et al. (2020), there is

a need to provide continual attention and psychological support on a timely basis. Management and

organizations that satisfy the demands of nurses, according to these writers, should give psychological

assistance. Sheroun et al. (2020) emphasized that offering psychological support and confidence to

nursing students helps them overcome stress, cope with the lockout, and do better in their studies.

According to Shaohua et al. (2020), hospital management must also “identify and address the root

causes of the nurses' psychological difficulties as soon as possible” (n.p.). Shaohua et al. (2020) further

stress that hospital administrators should encourage nurses to use good coping mechanisms and social

18

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

out further research on how various nurse groups are coping with anxiety and stress during the COVID-

19 pandemic.

2.5.6 Managerial support

The sixth and final topic highlighted as a method nurses adopt during the COVID-19 epidemic in the

reviewed literature is management assistance. Managers hold a crucial role in meeting the demands of

their staff. Only three studies have discussed management support as a nursing strategy during the

COVID-19 epidemic (Ali et al., 2020; Shaohua et al., 2020). According to the study conducted by Shaohua

et al. (2020), “management should pay close attention to nurses' job pressure and mental health in

combating COVID-19”. The researchers (Shaohua et al., 2020) also stress the need for management to

identify and address the root causes of the nurses' psychological difficulties as soon as possible.

Furthermore, hospital administrators should also encourage nurses to use good coping mechanisms and

social support to lower harmful psychological levels, as noted by Shaohua et al. (2020). Ali et al. (2020)

evidenced that “the role of hospital administration offered psychological support as a critical aspect in

nurses' capacity to overcome COVID-19 problems”. Shahrour and Dardas (2020) argue that nurse

managers may take the lead in adopting “stress-reduction methods for nurses by giving consecutive rest

days, rotating challenging patient assignments, coordinating support services, and being available to the

nursing staff” (p. 2134).

2.6 Research Gap

The review of the existing literature revealed that a few current studies had been conducted to

investigate the relationship between nurses’ stress, depression, and anxiety during the COVID-19

pandemic and the coping strategies to overcome these conditions. However, no study has been

conducted to date to investigate the effects of coping strategies on nurses' anxiety levels in the UK

during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of this study hope to fill this research gap.

19

Paraphrase This Document

3.1 Introduction

The present study is a quantitative research that investigates the effects of coping strategies used by

nurses on their anxiety levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. This chapter presents the methodological

framework adopted in the current study. The chapter comprises sections on research design, study

population, sample, and research process. Further, it sheds light on the tools used in this study to

achieve the objectives. In addition, this chapter explains the population selected for the study, the

sampling technique used to collect data, and data collection and analysis procedures. Lastly, it talks

about the ethical principles and considerations taken care of in this study.

3.2 Study Design

This study was quantitative. The researcher used a cross-sectional design that aimed to explore the

effects of coping strategies on nurses' anxiety levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. The basic rationale

for this design is to “collecting data to test hypotheses or to answer questions about people’s opinions

on some topic or issue” (Gay et al., 2012, p. 118). Online questionnaires were sent to the respondents.

3.3 Study Participants

The online questionnaires were sent to 500 nurses as the initial aim was to collect information from 500

nurses. The study population comprised nurses working in the COVID-19 wards in 10 UK hospitals. A

participation code was used to identify participants. However, 96 respondents did not correctly

complete the surveys and left certain areas blank, so these had to be eliminated, leaving the researcher

with 404 filled and finished questionnaires.

3.4 Research Tools

The following tools were used to measure the variables and establish a link between them in this study:

1. Demographic questionnaire

20

3. Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-Cope) (Dias et al., 2012)

Higher scores reflect higher construct values for each questionnaire measure.

Demographic questionnaire

The researcher created this questionnaire to collect information on the study respondents' backgrounds.

It gathered information on the nurses' demographic, social, and job-related aspects. The questionnaire

consisted of six items concerning the respondents’ age, gender, marital status, having children, work

experience in years, and working position (See Appendix A).

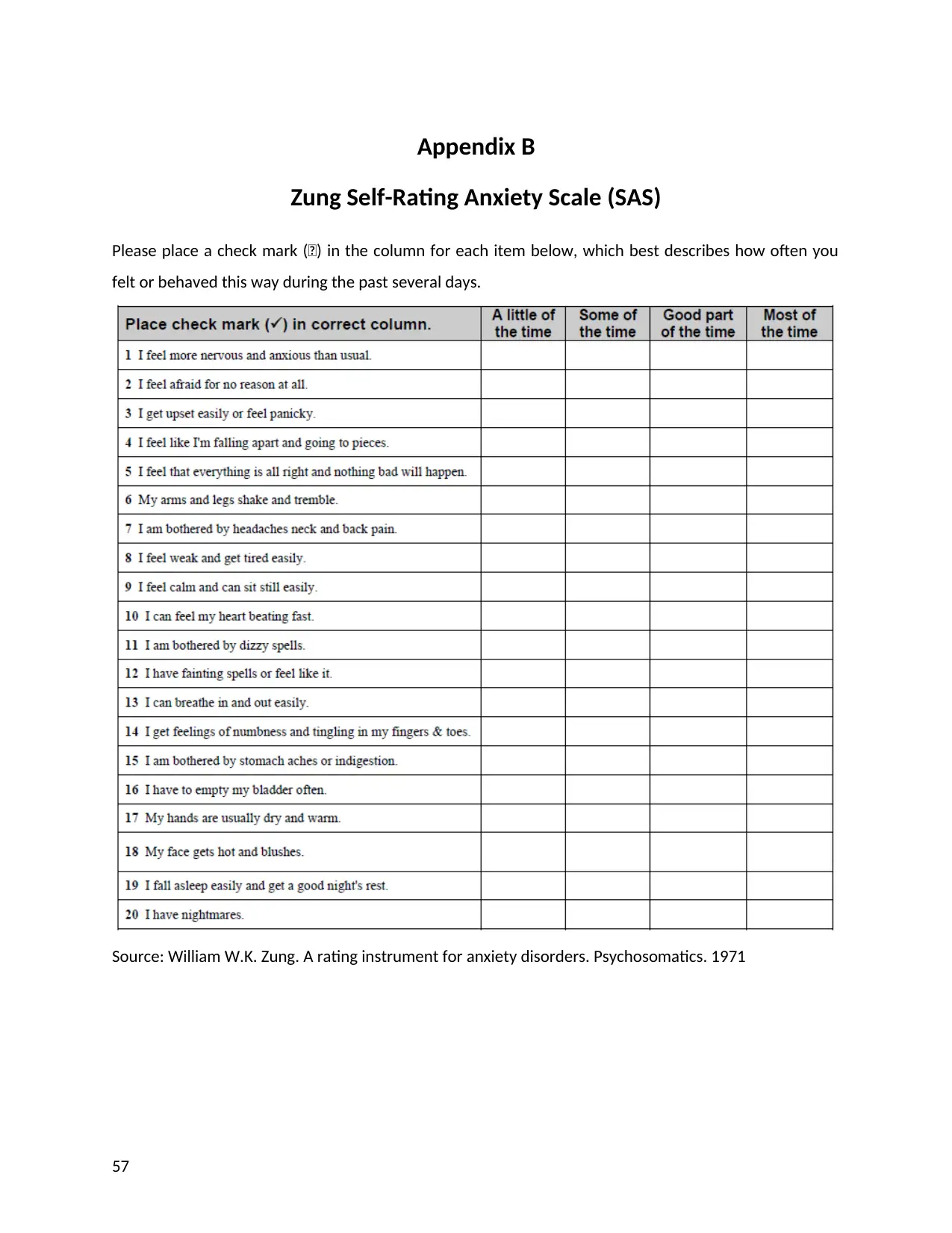

3.4.1 The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) (Zung, 1971)

The SAS (See Appendix B), developed by ZUNG in 1971, assesses degrees of anxiety. The scale has “20

items and a 4-point scoring method” to determine “the frequency of symptoms (1 = no or little time,

two = a small part of the time, three = a considerable amount of time, and four = most or all of the

time)”. Out of these items, 15 employ negative language (e.g., "I feel more worried and anxious than

usual"; "I feel terrified for no reason") and are rated on a scale of “1 to 4”. The last five items are graded

in reverse and utilize positive language (e.g., "I feel calm and sit still easily"; "I can breathe in and out

effortlessly"). The raw score is calculated by “adding the scores of all items,” The standard score is

calculated by “multiplying the raw score by 1.25”. The higher the standard SAS score, the greater the

amount of anxiety.

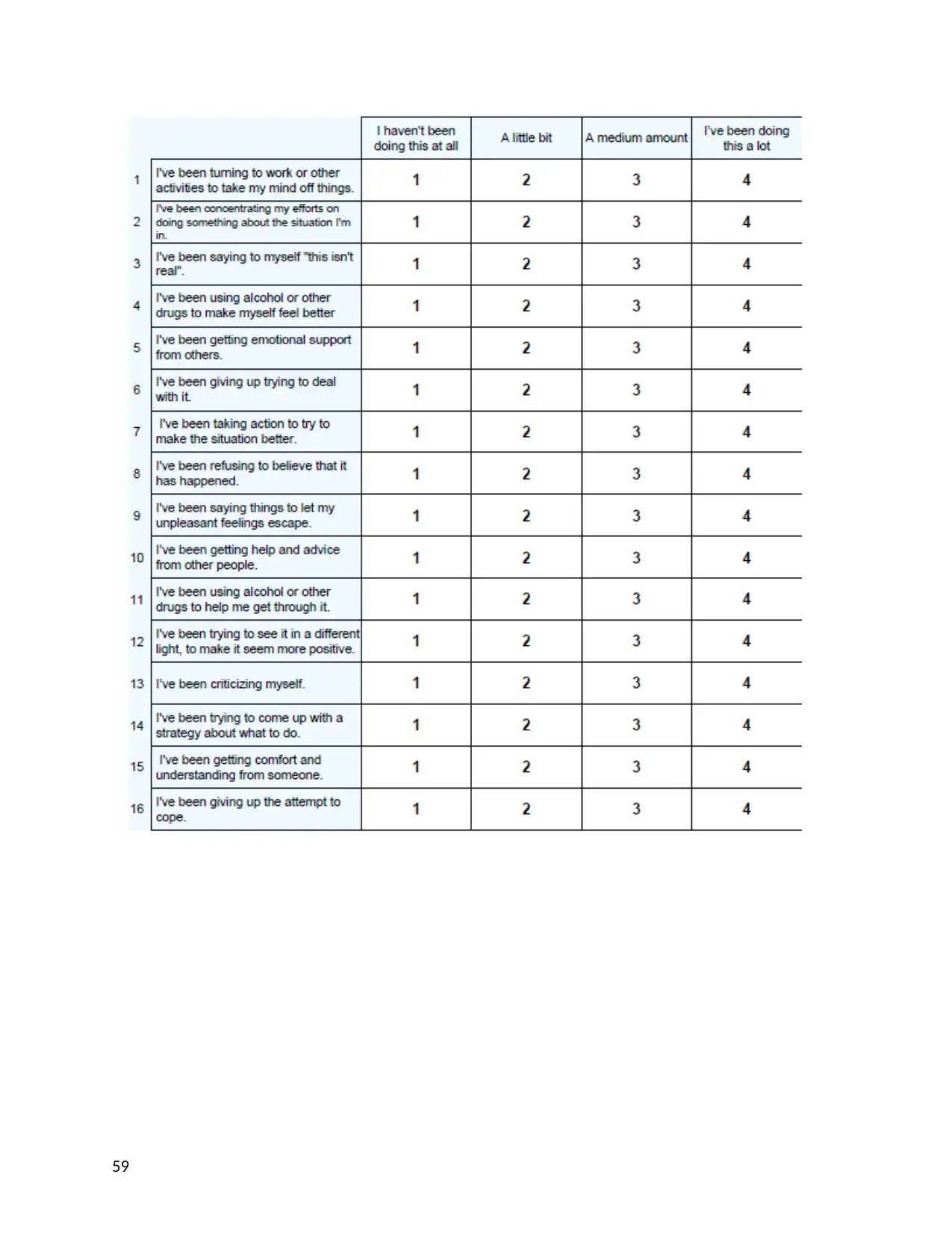

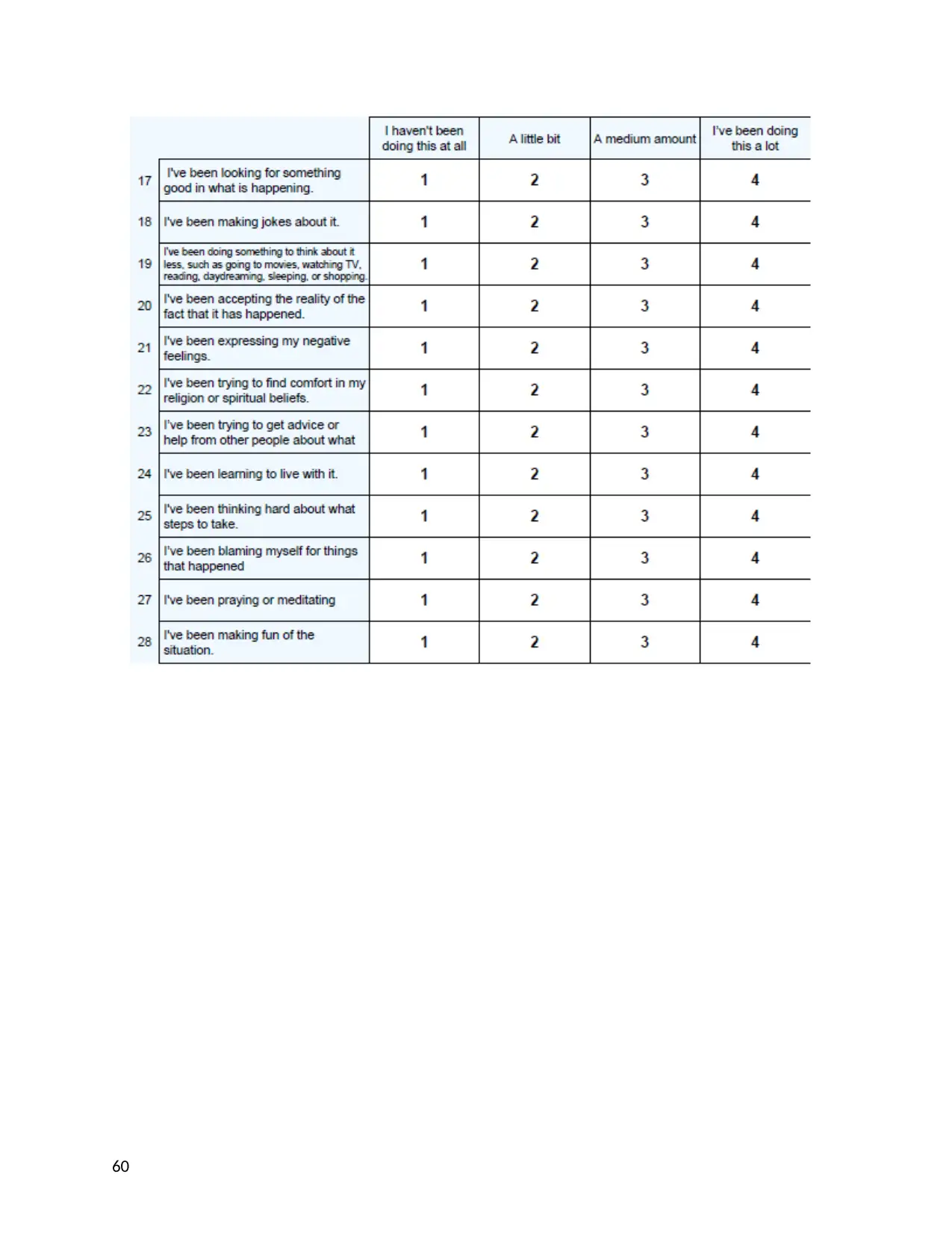

Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-Cope) (Dias et al., 2012)

"Coping" is defined broadly as an endeavor to reduce the suffering caused by unfavorable life situations.

The Brief-COPE (See Appendix C) is “a 28-item self-report questionnaire” designed to assess “successful

and inefficient coping strategies in the face of a stressful life event.” The Brief-Cope was created by Dias

et al. (2012) as a condensed “version of the original 60-item COPE scale” created by Carver et al. (1989),

which was theoretically drawn from several coping theories. Scores for three overarching coping

methods are reported as “average scores (sum of item scores divided by several items), reflecting the

extent to which the respondent has used that coping style.”

“1= I haven’t been doing this at all

2= A little bit

3= A medium amount

21

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

With scores on the following three subscales, the scale can indicate a person's following three principal

coping styles:

“Problem-Focussed Coping

Emotion-Focussed Coping

Avoidant Coping”

The three overarching coping styles are elucidated below:

Problem-Focused Coping: “(Items 2, 7, 10, 12, 14, 17, 23, 25)”

“A high score” suggests that coping mechanisms are being used to change stressful circumstances. It is

characterized by active coping, informational assistance, planning, and positive reframing. “High scores”

indicate psychological strength, tenacity, and a practical approach to problem resolution, in addition to a

penchant for positive outcomes.

Emotion-Focused Coping: “(Items 5, 9, 13, 15, 18, 20, 21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 28)”

Venting, emotional support, comedy, acceptance, self-blame, and religion are all characteristics of

emotion-focused coping. “A high score implies coping techniques to regulate emotions related to the

stressful circumstance.” High or low scores are not universally connected with psychological wellness or

ill health, but they can be used to generate a more comprehensive assessment of the respondent's

coping methods.

Avoidant Coping: “(Items 1, 3, 4, 6, 8, 11, 16, 19)”

Self-distraction, denial, drug abuse, and behavioral disengagement are all avoidant coping. “A high score

indicates that physical or cognitive attempts were made to disconnect from the stressor.” Low scores

are usually a sign of avoidant coping.

3.5 Procedure

The link to the online questionnaire was sent via email to the nursing officers at the ten selected

hospitals. The criteria for inclusion in the study were hospitals designated for treating COVID-19

patients, which permitted participation in the study. The nursing officers then invited eligible nurses of

22

Paraphrase This Document

clear and extensive explanations in the email regarding the goal, projected time necessary to fill and

complete the online questionnaires, confidentiality, and the opportunity to refuse to participate in the

study or to withdraw at any time without providing any reason. After getting ethical permission from the

University of Wolverhampton, data collection commenced. Participation was entirely optional and

voluntary. Participants' electronic permission (See Appendix A) was gained by asking them to click on

the "agree" button. The responses were confidential since they were not asked to share their names,

email addresses, and hospital names.

3.6 Data Analysis

SPSS version 25.0 was used to analyze the data (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The nurses' demographic,

social, and job-related variables and their reported degree of anxiety and coping mechanisms were

summarized and described using descriptive statistics. The link between coping techniques and

perceived anxiety levels was measured, and hypotheses were tested using Pearson’s correlation. The

correlation between coping strategies and reported anxiety levels was assessed using regression

analysis. Asymptotic values of 0.01 and 0.05 were considered significant.

3.7 Ethical Considerations

The researcher was responsible for adhering to ethical norms during data collection and reporting the

study's findings. The following ethical principles were taken care of:

The researcher obtained prior permission from the ethics committee of the university to

conduct the research and collect data from a human population and sample

The researcher briefed the participants on the aims and objectives of the current study through

an online information sheet

The researcher obtained the participants’ consent for participation in the study before data

collection on online consent forms

The study participants had the right to withdraw from participation in the study at any stage

without explaining the reason

23

participants

Chapter Four: Results

4.1 Introduction

The current research aimed to investigate the effects of coping strategies on nurses' anxiety levels

during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data were analysed with the IBM statistical program for social

sciences (SPSS) version 25. For each scale, descriptive statistics and reliability analysis were provided.

For evaluating the study hypotheses, correlation analysis and regression analysis were used to measure

the associations between the study variables, independent coping strategies, and dependent variables

of anxiety levels. Three sub-scales that is problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and

avoidant coping, were measured under the independent variable of coping strategies. The

asymptomatic value was estimated at two levels of significance, p≤0.01 and p≤0.05. This signifies that

“the probability of distribution of values occurring by chance is less than .01 or 1 in 100, and less

than .05 or 5 in 100” (Greasley, 2008, p. 671).

4.2 Reliability and Validity of the Data

Since the two scales used for this study are already established hierarchies, there was no need to test

their reliability. However, validity was confirmed in this study. The external reality, according to Cohen

et al. (2000, p. 107), is "the degree to which the results may be generalized [sic] to the wider

population.” External validity is associated with “generalizability.” It was kept by ensuring that the

sample size (n=404) was large enough to produce statistically significant findings. However, it was not

practicable to include all of the nurses in the United Kingdom. As a result, the sample was limited to

nurses from ten hospitals in the United Kingdom. It made it difficult to generalize the study's findings to

a more extensive selection of nurses working in the COVID wards in the UK.

Internal validity, in contrast, is "concerned with the extent to which explanations can be sustained by

the data" (Cohen et al., 2000, p 107). It was achieved by gathering data from three self-reporting

surveys, in which respondents filled out the questionnaires independently and gave the information on

24

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

guaranteeing safe data storage, and creating backup files.

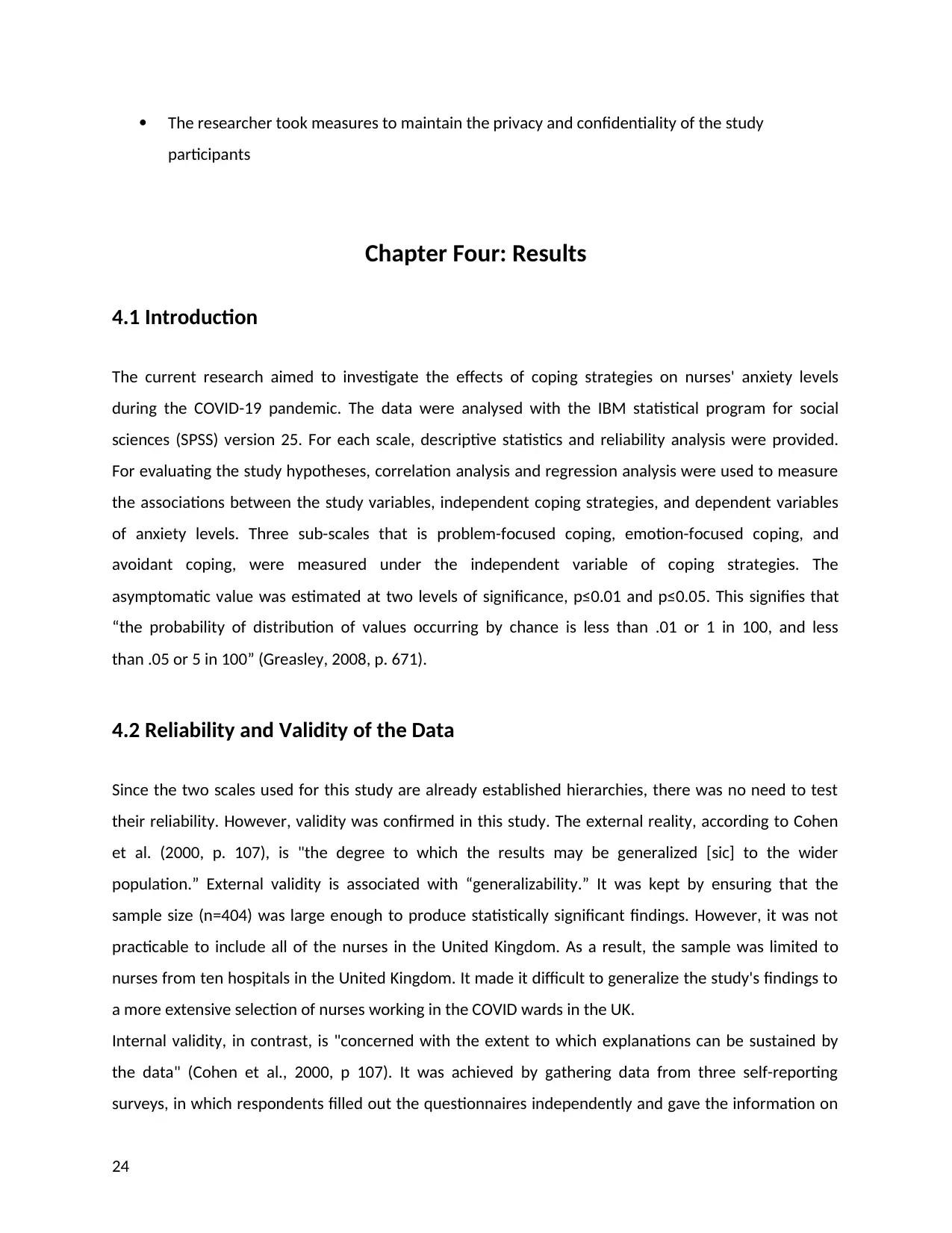

4.3 Demographic Results

The respondents to the questionnaires were nurses working in the COVID ward in 10 hospitals in the UK.

The online questionnaires were sent to 500 nurses. However, 96 respondents did not correctly complete

the surveys and left certain areas blank, so these had to be eliminated, leaving the researcher with 404

filled and finished questionnaires that resulted in a sound total return rate of 80.8 percent. The

demographic questionnaire consisted of 6 items developed to collect information on the respondents’

background comprising their age, gender, marital status, children's work experience as a nurse in years,

and working position as a nurse. Descriptive statistics were run to get the frequency and percentage of

the distribution of the study respondents across all the items of the demographic questionnaire. Table

4.1 shows a breakdown of the demographic questionnaire results.

Table 4.1 Demographic results

No. Categories Groups Frequency of

respondents

% Mean

1 Age 21-30 years

31-40 years

41-50 years

Above 50 years

36

214

109

45

9.0%

53.0%

26.9%

11.1%

38.56

2 Gender Male

Female

Other

72

324

8

17.8%

80.2%

2.0%

2.82

3 Marital status Married or in a

steady relationship

or civil union)

Married

Widowed

Divorced

Single

48

198

18

86

54

12.0

49.0

4.5

21.2

13.3

2.56

4 Have children Yes

No

335

69

82.9%

17.1%

1.99

5 Work experience as a nurse

in years

1-5 years

6-10 years

11-15 years

16-20 years

21-25 years

More than 25 years

24

153

125

86

13

3

5.9%

37.9%

31.0%

21.3%

3.2%

0.7%

2.9

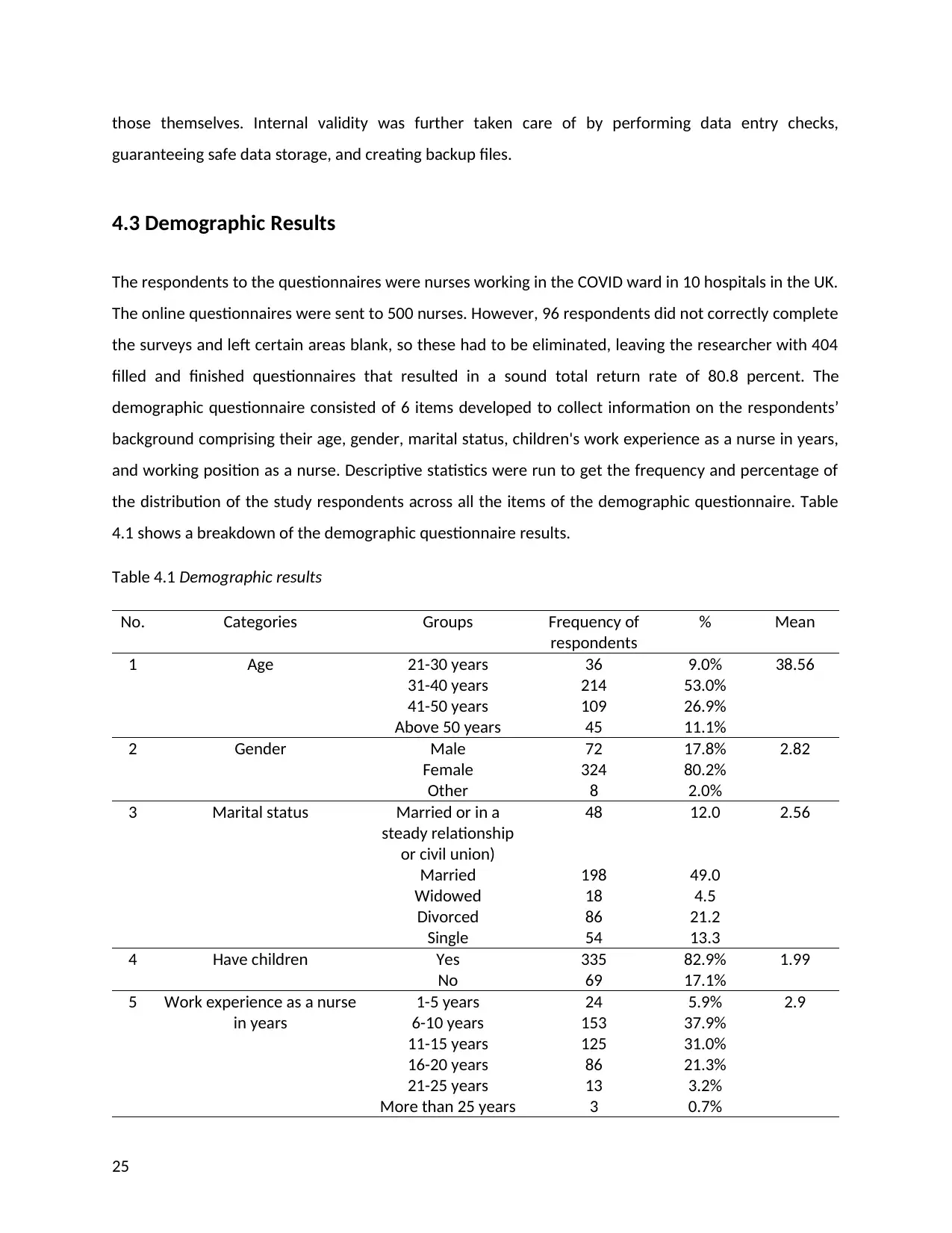

25

Paraphrase This Document

Second-line

286

118

70.8

29.2

1.86

The screened sample size (N=404) included 324 females (80.2%), 72 male (17.8%), and 8 undeclared

(2.0%). The majority of the study respondents were females. Only 13.3% of the respondents were single,

indicating that the major part of the sample was in a relationship, and 82.9% reported that they had

children. These findings show that most of the nurses in this study working in the COVID wards had

families and dependent children. The rest of the data reveals that a substantive percentage of the study

respondents had the nursing experience of 6-10 years (37.9%), 11-15 years (31.0%), and 16-20 years

(21.3%). Lastly, many of the nurses in this research reported that they worked as front-line nurses

(70.8%), which indicates that a major part of the current study respondents was working very close to

the COVID patients.

4.4 Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics were computed to address research objectives 1 & 2:

1. To explore the levels of pandemic induced anxiety amongst the nurses

2. To study the strategies adopted by the nurses to cope with the pandemic induced anxiety

Percentages of all the items in the questionnaires of the two scales that is SAS and Brief-COPE, were

examined. In addition, descriptive statistics (Mean and standard deviation) of the scores of the two

scales, SAS and Brief-Cope, were calculated to get the overall results (anxiety and coping strategies

scores).

Table 4.2 below presents the results in percentages for SAS.

Table 4.2 SAS percentage results

No

.

Items A little of

the time

%

Some of

the time

%

A good part

of the time

%

Most of

the time

%

1 I feel more nervous and anxious

than usual.

62.0% 16.2% 13.2% 8.6%

2 I feel afraid for no reason at all. 66.8% 15.3% 11.9% 6.0%

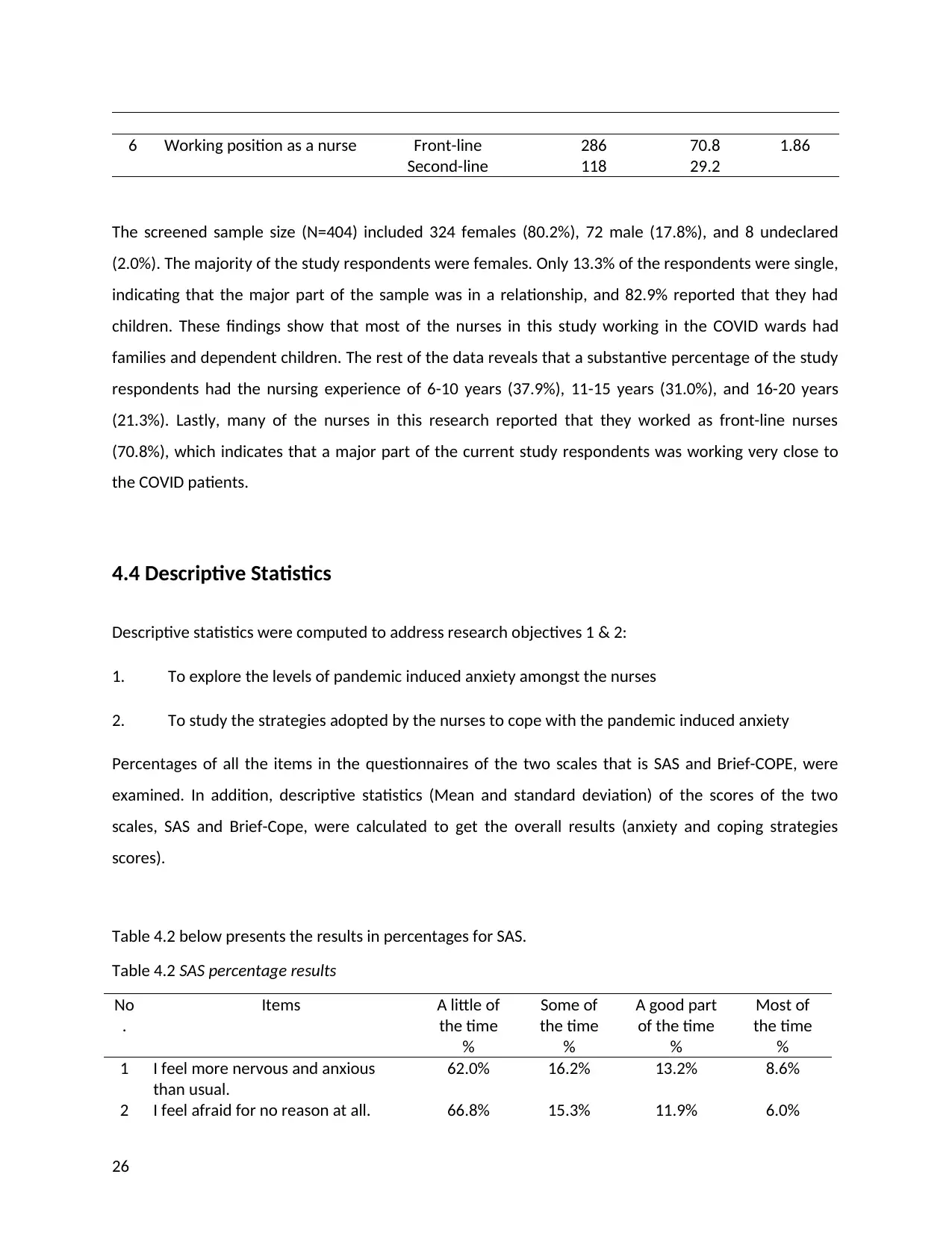

26

4 I feel like I'm falling apart and going

to pieces.

63.1% 18.9% 13.1% 4.9%

5 I feel that everything is all right and

nothing wrong will happen.

5.2% 4.8% 15.8% 74.2%

6 My arms and legs shake and

tremble.

68.8% 13.3% 10.9% 7.0%

7 I am bothered by headaches, neck

and back pain.

56.7% 24.3% 12.8% 6.2%

8 I feel weak and get tired quickly. 57.3% 28.6% 9.3% 4.8%

9 I feel calm and can sit still easily. 1.2% 8.7% 25.2% 64.9%

10 I can feel my heart beating fast. 60.1% 23.1% 10.1% 6.7%

11 I am bothered by dizzy spells. 41.5% 30.2% 18.2% 10.1%

12 I have fainting spells or feel like it. 61.1% 28.7% 7.2% 3.0%

13 I can breathe in and out quickly. 5.2% 11.1% 21.2% 62.5%

14 I get feelings of numbness and

tingling in my fingers & toes.

59.9% 26.7% 11.2% 2.2%

15 I am bothered by stomach aches or

indigestion.

52.5% 25.2% 17.6% 4.7%

16 I have to empty my bladder often. 58.8% 27.5% 10.6% 3.1%

17 My hands are usually dry and warm. 5.1% 10.4% 23.8% 60.7%

18 My face gets hot, and I blush. 54.9% 22.2% 18.3% 4.6%

19 I fall asleep quickly and get a good

night's rest.

4.7% 10.1% 26.1% 59.1%

20 I have nightmares 61.9% 23.7% 10.2% 4.2%

The results for SAS in table 4.2 indicate that the majority of the study respondents had low levels of

anxiety. However, approximately 4.0% to 5.0% of the respondents did show higher anxiety levels, overall

13.0% to 15.0% had moderate stress, and 22.0% to 24.0% had mild anxiety.

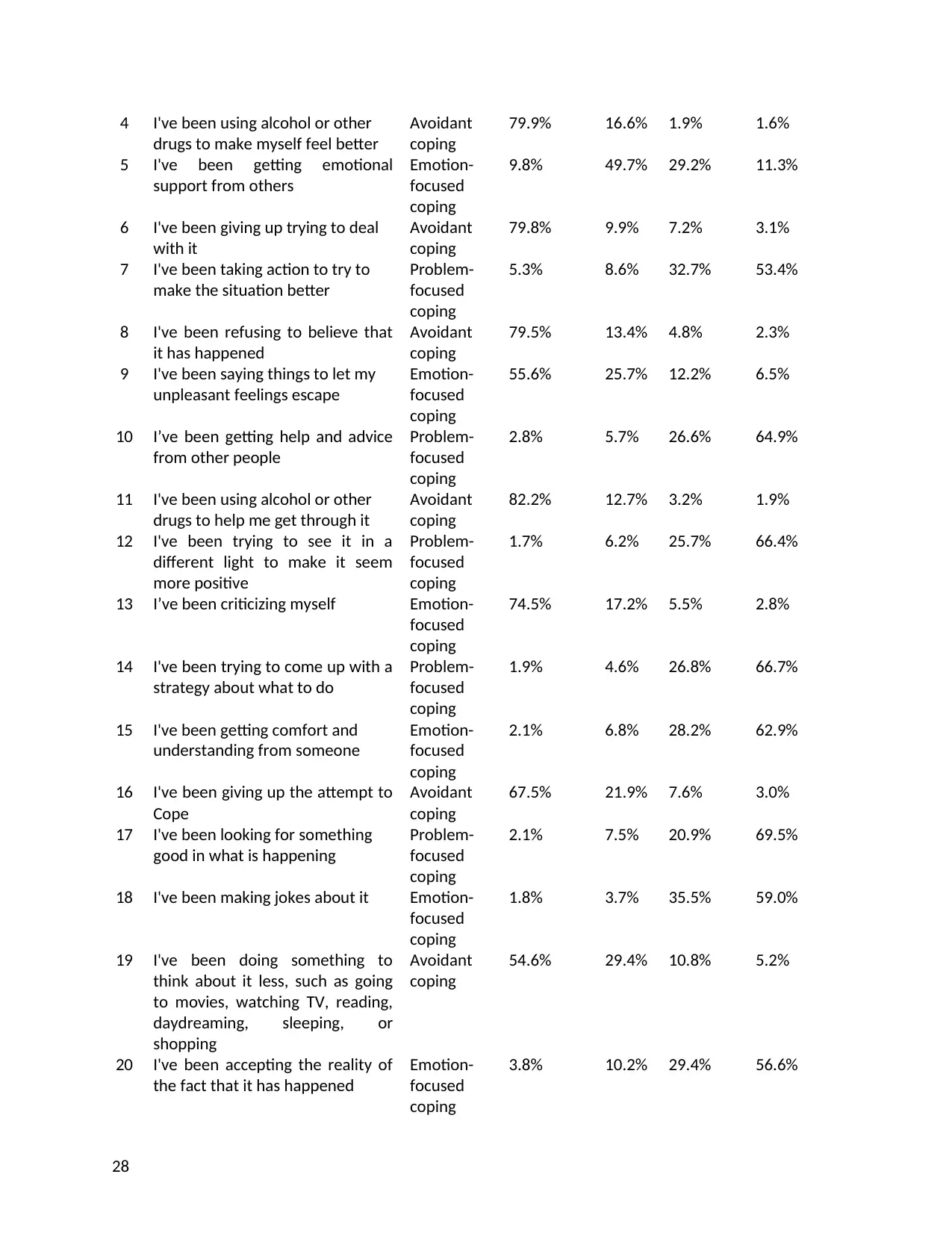

Table 4.3 below presents the percentage results for Brief-COPE.

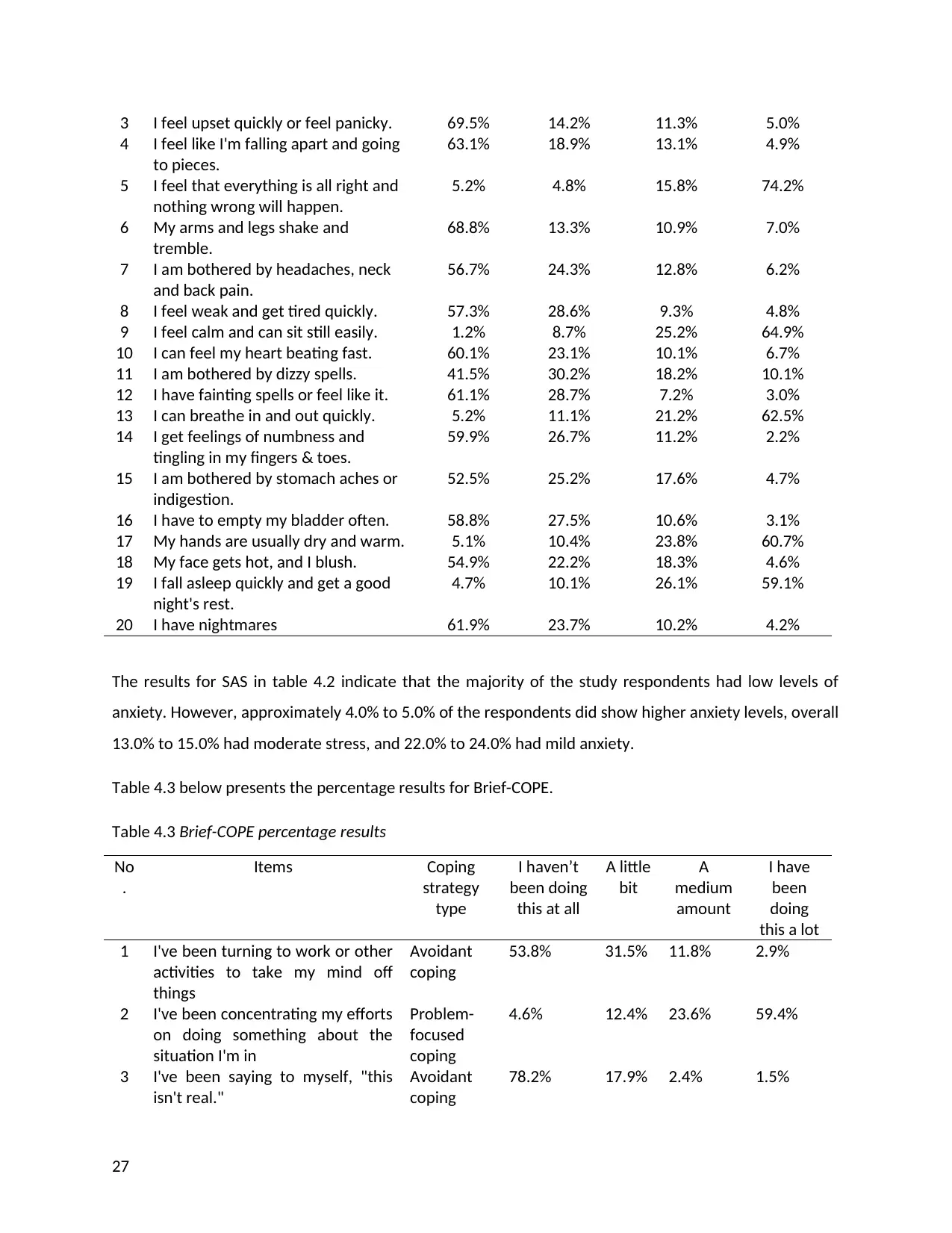

Table 4.3 Brief-COPE percentage results

No

.

Items Coping

strategy

type

I haven’t

been doing

this at all

A little

bit

A

medium

amount

I have

been

doing

this a lot

1 I've been turning to work or other

activities to take my mind off

things

Avoidant

coping

53.8% 31.5% 11.8% 2.9%

2 I've been concentrating my efforts

on doing something about the

situation I'm in

Problem-

focused

coping

4.6% 12.4% 23.6% 59.4%

3 I've been saying to myself, "this

isn't real."

Avoidant

coping

78.2% 17.9% 2.4% 1.5%

27

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

drugs to make myself feel better

Avoidant

coping

79.9% 16.6% 1.9% 1.6%

5 I've been getting emotional

support from others

Emotion-

focused

coping

9.8% 49.7% 29.2% 11.3%

6 I've been giving up trying to deal

with it

Avoidant

coping

79.8% 9.9% 7.2% 3.1%

7 I've been taking action to try to

make the situation better

Problem-

focused

coping

5.3% 8.6% 32.7% 53.4%

8 I've been refusing to believe that

it has happened

Avoidant

coping

79.5% 13.4% 4.8% 2.3%

9 I've been saying things to let my

unpleasant feelings escape

Emotion-

focused

coping

55.6% 25.7% 12.2% 6.5%

10 I’ve been getting help and advice

from other people

Problem-

focused

coping

2.8% 5.7% 26.6% 64.9%

11 I've been using alcohol or other

drugs to help me get through it

Avoidant

coping

82.2% 12.7% 3.2% 1.9%

12 I've been trying to see it in a

different light to make it seem

more positive

Problem-

focused

coping

1.7% 6.2% 25.7% 66.4%

13 I’ve been criticizing myself Emotion-

focused

coping

74.5% 17.2% 5.5% 2.8%

14 I've been trying to come up with a

strategy about what to do

Problem-

focused

coping

1.9% 4.6% 26.8% 66.7%

15 I've been getting comfort and

understanding from someone

Emotion-

focused

coping

2.1% 6.8% 28.2% 62.9%

16 I've been giving up the attempt to

Cope

Avoidant

coping

67.5% 21.9% 7.6% 3.0%

17 I've been looking for something

good in what is happening

Problem-

focused

coping

2.1% 7.5% 20.9% 69.5%

18 I've been making jokes about it Emotion-

focused

coping

1.8% 3.7% 35.5% 59.0%

19 I've been doing something to

think about it less, such as going

to movies, watching TV, reading,

daydreaming, sleeping, or

shopping

Avoidant

coping

54.6% 29.4% 10.8% 5.2%

20 I've been accepting the reality of

the fact that it has happened

Emotion-

focused

coping

3.8% 10.2% 29.4% 56.6%

28

Paraphrase This Document

Feelings

Emotion-

focused

coping

49.7% 30.9% 14.2% 5.2%

22 I've been trying to find comfort in

my religion or spiritual beliefs

Emotion-

focused

coping

4.3% 11.4% 33.5% 50.8%

23 I’ve been trying to get advice or

help from other people about

what

Problem-

focused

coping

2.3% 6.4% 21.1% 70.2%

24 I’ve been learning to live with it Emotion-

focused

coping

2.1% 8.4% 29.7% 59.8%

25 I've been thinking hard about

what steps to take

Problem-

focused

coping

1.6% 4.8% 23.7% 69.9%

26 I’ve been blaming myself for

things that happened

Emotion-

focused

coping

1.8% 3.6% 18.9% 75.7%

27 I’ve been praying or meditating Emotion-

focused

coping

3.3% 7.8% 26.4% 62.5%

28 I've been making fun of the

Situation

Emotion-

focused

coping

59.0% 29.6% 8.7% 2.7%

The overall results for Brief-COPE presented in table 4.3 reveal that a little more than half of the study

respondents used problem-focused coping, a little less than half of the respondents used emotion-

focused coping, and a small proportion of the respondents used avoidant coping strategies for

overcoming their anxiety levels induced by COVID-19 pandemic.

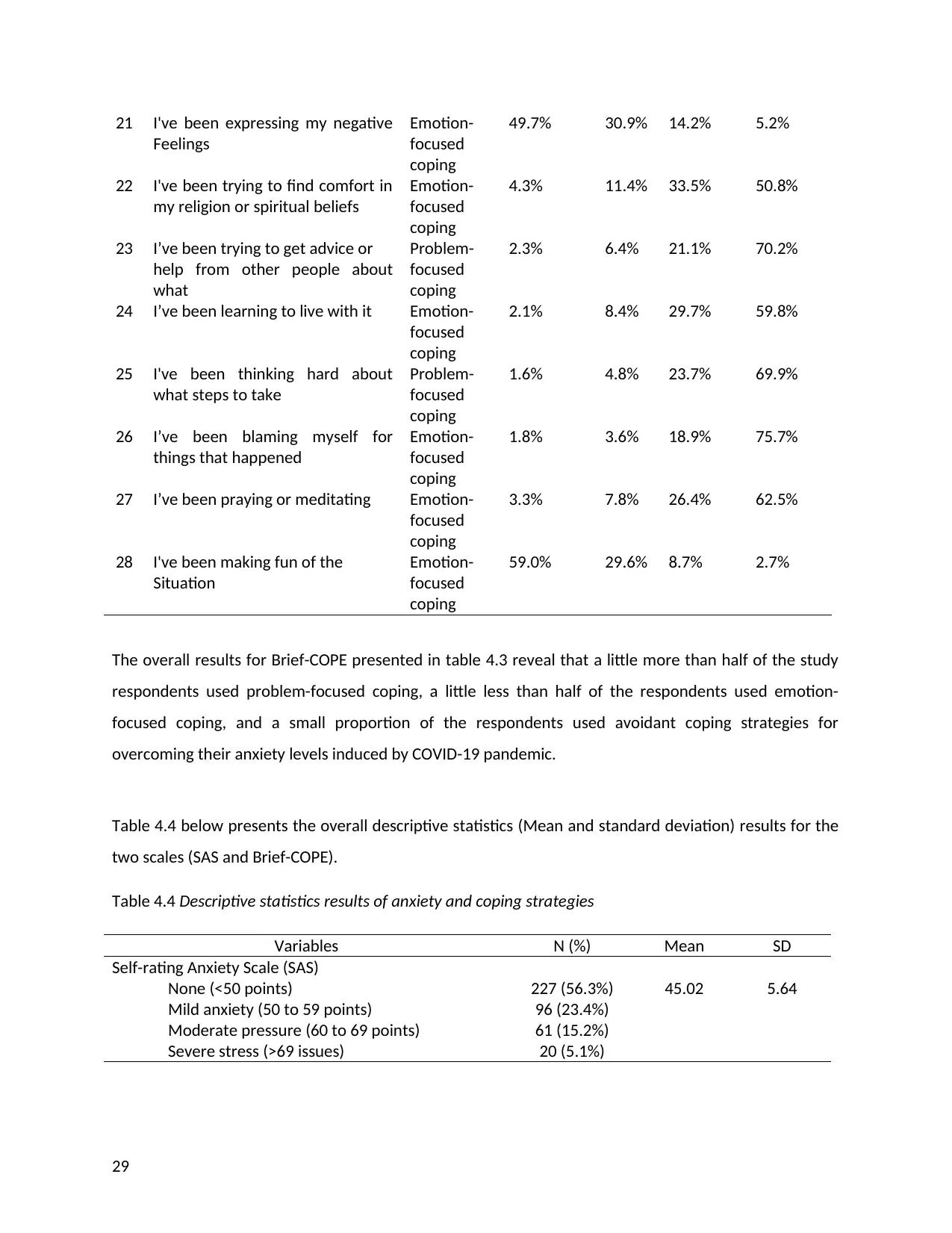

Table 4.4 below presents the overall descriptive statistics (Mean and standard deviation) results for the

two scales (SAS and Brief-COPE).

Table 4.4 Descriptive statistics results of anxiety and coping strategies

Variables N (%) Mean SD

Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS)

None (<50 points)

Mild anxiety (50 to 59 points)

Moderate pressure (60 to 69 points)

Severe stress (>69 issues)

227 (56.3%)

96 (23.4%)

61 (15.2%)

20 (5.1%)

45.02 5.64

29

(Brief-COPE)

Problem-focused coping

Emotion-focused coping

Avoidant coping

205 (50.7%)

166 (41.2%)

33 (8.1%)

1.96 0.75

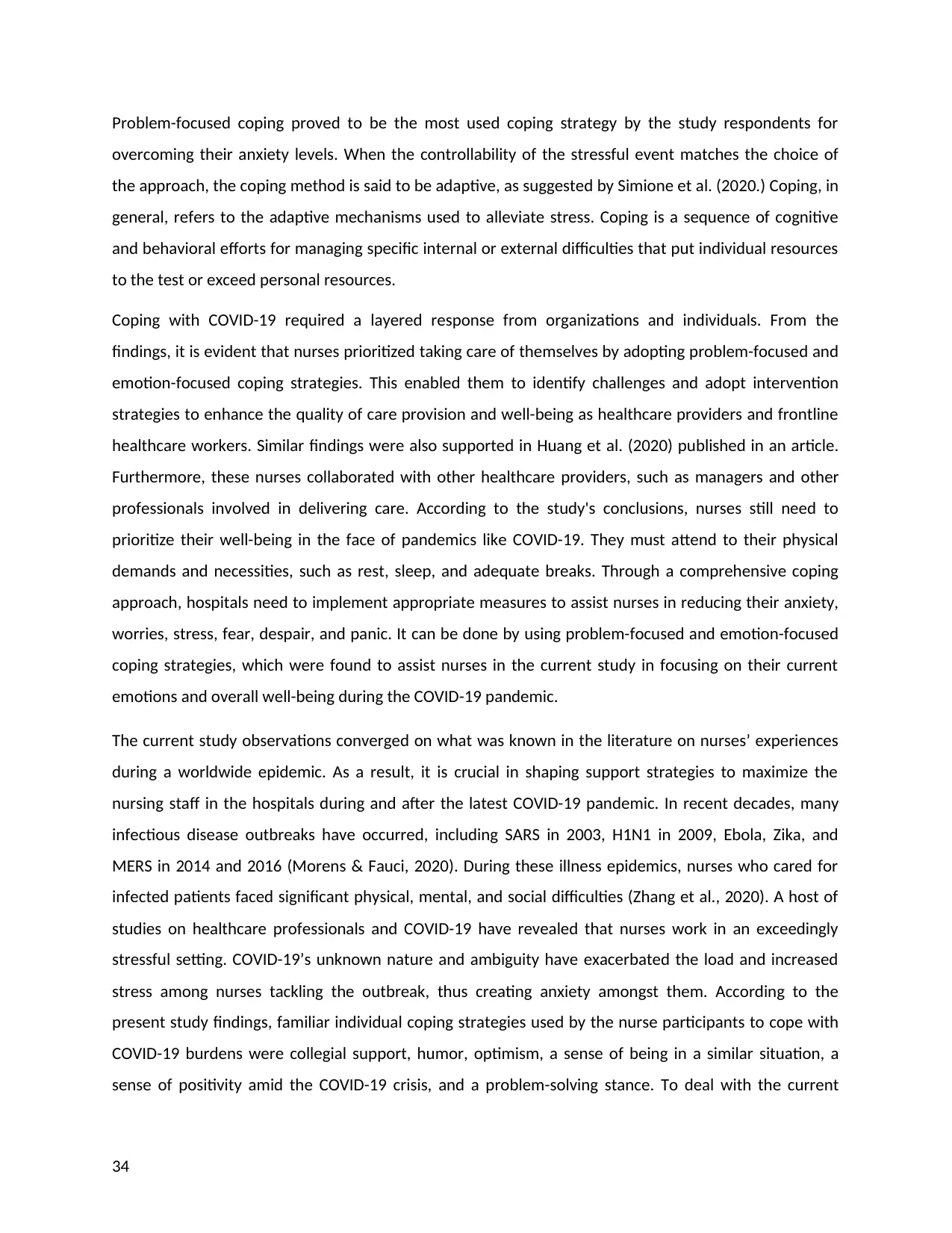

The overall descriptive statistics results show that among the study respondents, 227 (56.3%) reported

no anxiety symptoms, 96 (23.4%) reported mild anxiety level, 61 (15.2%) said moderate anxiety level

and 20 (5.1%) reported severe anxiety level. As far as coping strategies used by the study respondents

are concerned, 205 (50.7%) respondents used problem-focused coping, 166 (41.2%) used emotion-

focused coping, and 33 (8.1%) used avoidant coping strategies to overcome anxiety caused by working

in the COVID ward during COVID-19 pandemic. The results reveal that problem-focused coping is the

most frequently used coping strategy, with emotion-focused coping standing at number two most

preferred or used coping strategy employed by nurses to manage and reduce their anxiety levels during

COVID-19 pandemic while working in the COVID wards.

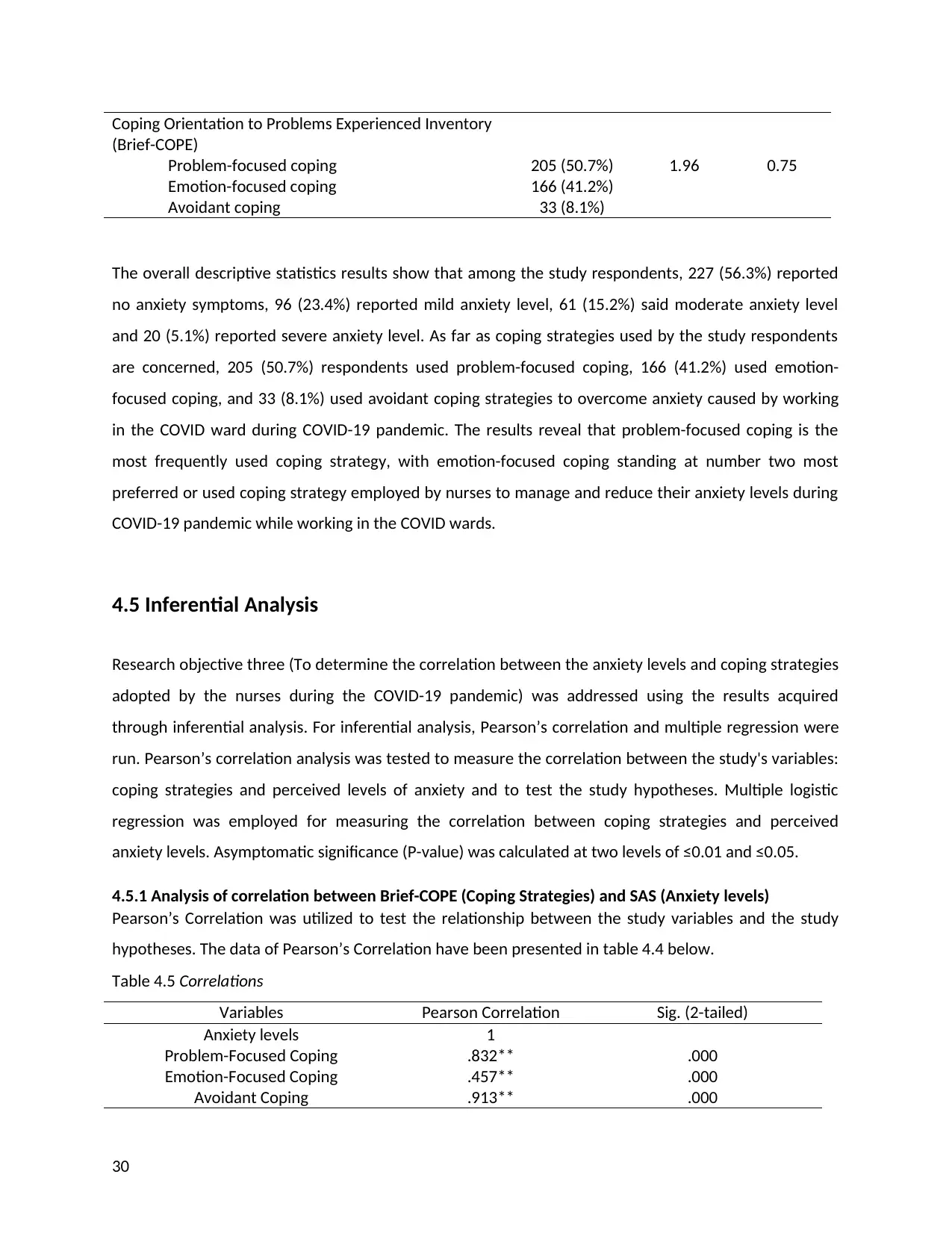

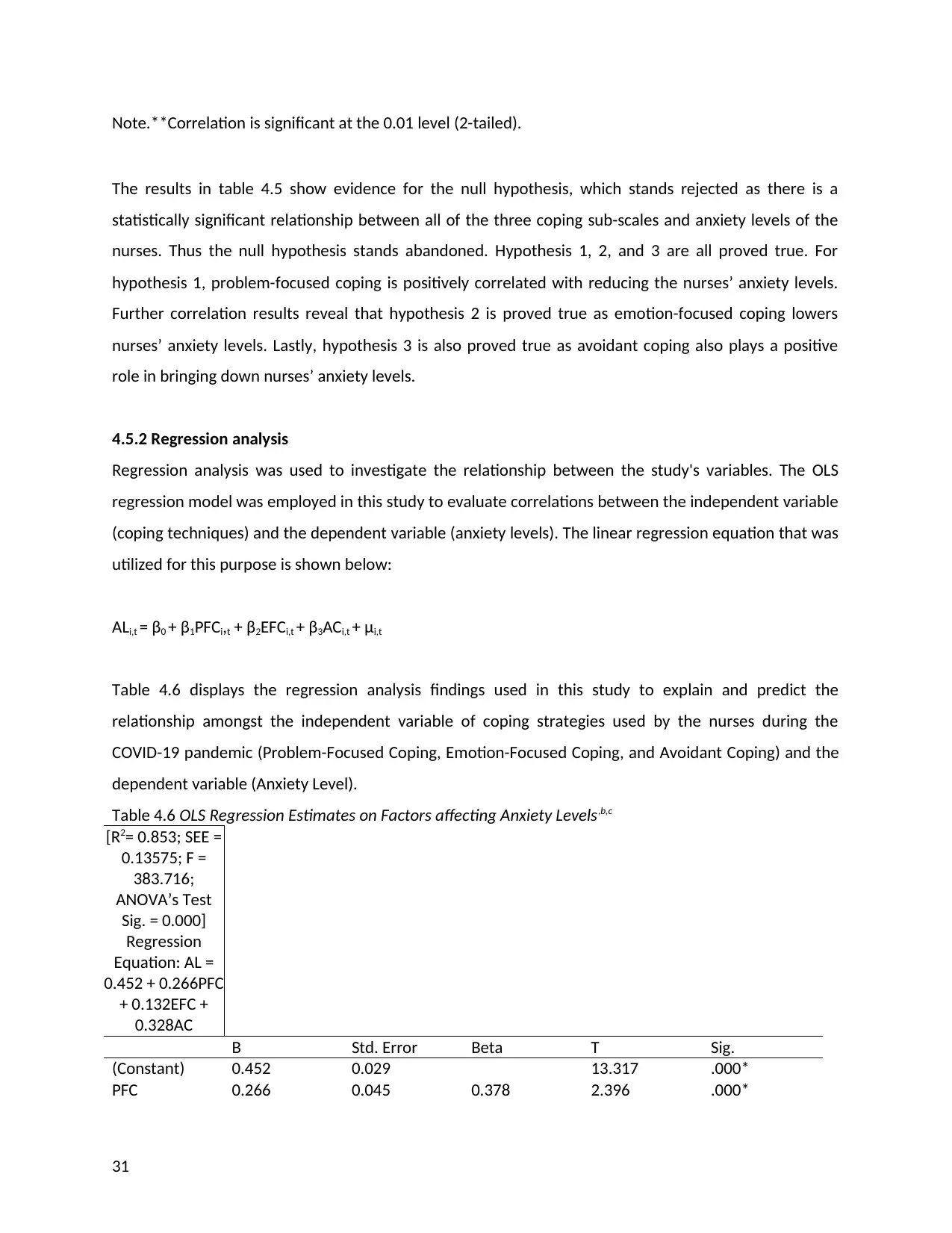

4.5 Inferential Analysis

Research objective three (To determine the correlation between the anxiety levels and coping strategies

adopted by the nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic) was addressed using the results acquired

through inferential analysis. For inferential analysis, Pearson’s correlation and multiple regression were

run. Pearson’s correlation analysis was tested to measure the correlation between the study's variables:

coping strategies and perceived levels of anxiety and to test the study hypotheses. Multiple logistic

regression was employed for measuring the correlation between coping strategies and perceived

anxiety levels. Asymptomatic significance (P-value) was calculated at two levels of ≤0.01 and ≤0.05.

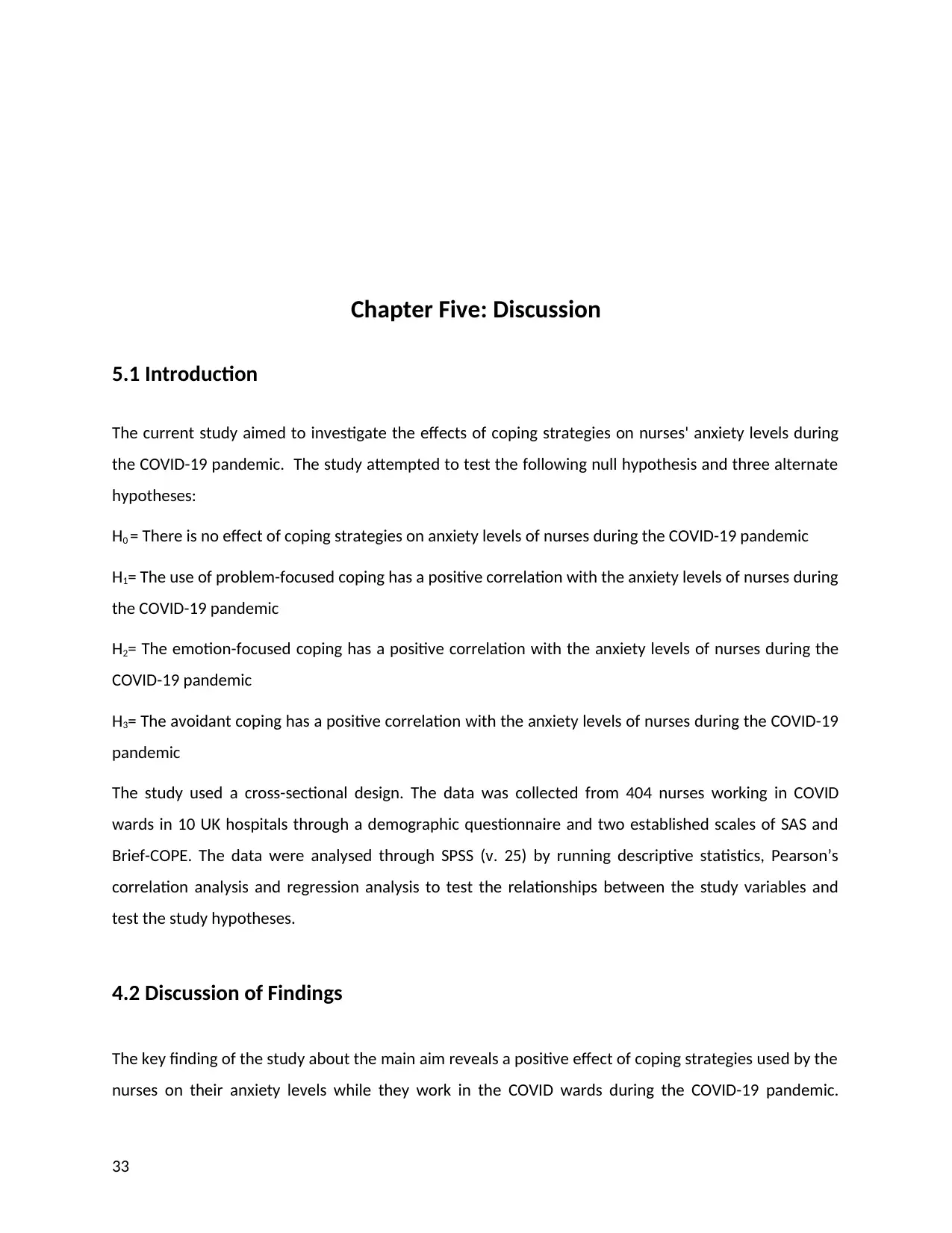

4.5.1 Analysis of correlation between Brief-COPE (Coping Strategies) and SAS (Anxiety levels)

Pearson’s Correlation was utilized to test the relationship between the study variables and the study

hypotheses. The data of Pearson’s Correlation have been presented in table 4.4 below.

Table 4.5 Correlations

Variables Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed)

Anxiety levels 1

Problem-Focused Coping .832** .000

Emotion-Focused Coping .457** .000

Avoidant Coping .913** .000

30

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The results in table 4.5 show evidence for the null hypothesis, which stands rejected as there is a

statistically significant relationship between all of the three coping sub-scales and anxiety levels of the