Customer Satisfaction Measurement in Hospitality Enterprises: A Review

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|24

|21730

|16

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes the article "Customer satisfaction and its measurement in hospitality enterprises" by Abraham Pizam and Taylor Ellis, published in the International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. The article emphasizes customer satisfaction as a critical factor for success in the hospitality and tourism industries. It explores various methods for measuring customer satisfaction, including surveys and questionnaires, and discusses the importance of understanding customer expectations and requirements. The report delves into different theories of customer satisfaction, such as expectancy disconfirmation theory, and examines how these theories apply to the hospitality sector. It highlights the significance of a customer-oriented corporate culture and the challenges in implementing effective customer satisfaction measurement programs, while also considering global and cross-cultural issues impacting customer satisfaction. The article underscores the shift towards prioritizing customer value delivery and provides valuable insights for hospitality businesses aiming to enhance customer satisfaction and achieve sustainable competitive advantages.

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

Customer satisfaction and its measurement in hospitality enterprises

Abraham Pizam, Taylor Ellis,

Article information:

To cite this document:

Abraham Pizam, Taylor Ellis, (1999) "Customer satisfaction and its measurement in hospitality enterprises", International

Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 11 Issue: 7, pp.326-339, https://doi.org/10.1108/09596119910293231

Permanent link to this document:

https://doi.org/10.1108/09596119910293231

Downloaded on: 11 April 2019, At: 21:12 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 87 other documents.

To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 48209 times since 2006*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

(2011),"Hospitality quality: new directions and new challenges", International Journal of Contemporary

Hospitality Management, Vol. 23 Iss 4 pp. 463-478 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111111129986">https://

doi.org/10.1108/09596111111129986</a>

(2005),"Service innovation and customer choices in the hospitality industry", Managing Service Quality: An

International Journal, Vol. 15 Iss 6 pp. 555-576 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520510634023">https://

doi.org/10.1108/09604520510634023</a>

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emerald-srm:414810 []

For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service

information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Plea

visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portf

more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of

products and additional customer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication

Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

Customer satisfaction and its measurement in hospitality enterprises

Abraham Pizam, Taylor Ellis,

Article information:

To cite this document:

Abraham Pizam, Taylor Ellis, (1999) "Customer satisfaction and its measurement in hospitality enterprises", International

Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 11 Issue: 7, pp.326-339, https://doi.org/10.1108/09596119910293231

Permanent link to this document:

https://doi.org/10.1108/09596119910293231

Downloaded on: 11 April 2019, At: 21:12 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 87 other documents.

To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 48209 times since 2006*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

(2011),"Hospitality quality: new directions and new challenges", International Journal of Contemporary

Hospitality Management, Vol. 23 Iss 4 pp. 463-478 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111111129986">https://

doi.org/10.1108/09596111111129986</a>

(2005),"Service innovation and customer choices in the hospitality industry", Managing Service Quality: An

International Journal, Vol. 15 Iss 6 pp. 555-576 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520510634023">https://

doi.org/10.1108/09604520510634023</a>

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emerald-srm:414810 []

For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service

information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Plea

visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portf

more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of

products and additional customer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication

Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Customer satisfaction and its measurement in

hospitality enterprises

Abraham Pizam

Department of Hospitality Management, University of Central Florida, Orlando,

Florida, USA

Taylor Ellis

Department of Hospitality Management, University of Central Florida, Orlando,

Florida, USA

Measuring service quality via

customer satisfaction

Customer satisfaction is the leading criterion

for determining the quality that is actually

delivered to customers through the product/

service and by the accompanying servicing

(Vavra, 1997). Simply stated, customer satis-

faction is essential for corporate survival.

Several studies have found that it costs about

five times as much in time, money and

resources to attract a new customer as it does

to retain an existing customer (Naumann,

1995). This creates the challenge of main-

taining high levels of service, awareness of

customer expectations and improvement in

services and product.

Knowledge of customer expectations and

requirements, Hayes states, is essential for

two reasons ± it provides understanding of

how the customer defines quality of service

and products, and facilitates the development

of a customer satisfaction questionnaires

(Hayes, 1997, p. 7). Furthermore, customer

satisfaction is recognized as of great impor-

tance to all commercial firms because of its

influence on repeat purchases and word-of-

mouth recommendations (Berkman and

Gilson, 1986).

Satisfaction, reinforces positive attitudes

toward the brand, leading to a greater like-

lihood that the same brand will be purchased

again ... dissatisfaction leads to negative

brand attitudes and lessens the likelihood of

buying the same brand again (Assael, 1987,

p. 47).

Or as others put it:

...if consumers are satisfied with a product or

brand, they will be more likely to continue to

purchase and use it and to tell others of their

favorable experience with it ... if they are

dissatisfied, they will be more likely to switch

brands and complain to manufacturers,

retailers, and other consumers about the

product (Peter and Olson, 1987, p. 512).

Satisfaction of customers also happens to be

the cheapest means of promotion. Various

researchers have found this ratio to range

from about 10 to 1 (Knutson, 1988, p. 17) to 5 to

1 (Naumann, 1995, p. 22).

There are several ways to assess the

quality of services and customer satisfaction

through subjective, or soft, measures of

quality, which focus on perceptions and

attitudes of the customer rather than more

concrete objective criteria. These soft mea-

sures include customer satisfaction surveys

and questionnaires to determine customer

attitudes and perceptions of the quality of the

service they are receiving (Hayes, 1997, p. 2).

Because the extent to which goods or services

meet the customer's needs and requirements

is the index by which quality is determined,

customers' perceptions of service is vital in

identifying customer needs and satisfaction.

To be successful, a customer satisfaction

measurement (CSM) programme must come

from and be incorporated into the firm's

corporate culture (Naumann, 1995, p. 12). In

today's competitive environment one of the

most important goals of corporate cultures is

retaining and satisfying current and past

customers. Experience shows that only

``consumer oriented'' corporations can

achieve this goal. These companies focus on

the needs and wants of specific target groups

and then work hard to maximize satisfaction

with the product or service being offered

(Vavra, 1997, p. 12). Instead of waiting for

customer complaints to let them know when

something isn't satisfactory or wrong, a

The current issue and fulltext archive of this journalis availableat

http://www.emerald-library.com

[ 326 ]

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [ 1999] 326±339

# MCB University Press

[ISSN 0959-6119]

Keywords

Customer satisfaction,

Service quality,

Hospitality industry.

Abstract

Reviews and discusses the topic

of customer satisfaction and its

application to the hospitality and

tourism industries. Defines the

concept and analyzes its impor-

tance to services in general and to

hospitality/tourism services in

particular. Following a discussion

on the dimensions and attributes

of satisfaction, lists the main

methods of measuring satisfaction

and concludes with a review of

globaland cross-cultural issues

that affect satisfaction.

This article is partially

based on a previous article

published by one of the

current authors, Abraham

Pizam, and titled:

``Monitoring customer

satisfaction'', in Davis, B.E.

and Lockwood, A.J. (Eds),

Food and Beverage

Management: A Selection of

Readings, London,

Butterworth Heinemann,

1994, pp. 231-47.

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

hospitality enterprises

Abraham Pizam

Department of Hospitality Management, University of Central Florida, Orlando,

Florida, USA

Taylor Ellis

Department of Hospitality Management, University of Central Florida, Orlando,

Florida, USA

Measuring service quality via

customer satisfaction

Customer satisfaction is the leading criterion

for determining the quality that is actually

delivered to customers through the product/

service and by the accompanying servicing

(Vavra, 1997). Simply stated, customer satis-

faction is essential for corporate survival.

Several studies have found that it costs about

five times as much in time, money and

resources to attract a new customer as it does

to retain an existing customer (Naumann,

1995). This creates the challenge of main-

taining high levels of service, awareness of

customer expectations and improvement in

services and product.

Knowledge of customer expectations and

requirements, Hayes states, is essential for

two reasons ± it provides understanding of

how the customer defines quality of service

and products, and facilitates the development

of a customer satisfaction questionnaires

(Hayes, 1997, p. 7). Furthermore, customer

satisfaction is recognized as of great impor-

tance to all commercial firms because of its

influence on repeat purchases and word-of-

mouth recommendations (Berkman and

Gilson, 1986).

Satisfaction, reinforces positive attitudes

toward the brand, leading to a greater like-

lihood that the same brand will be purchased

again ... dissatisfaction leads to negative

brand attitudes and lessens the likelihood of

buying the same brand again (Assael, 1987,

p. 47).

Or as others put it:

...if consumers are satisfied with a product or

brand, they will be more likely to continue to

purchase and use it and to tell others of their

favorable experience with it ... if they are

dissatisfied, they will be more likely to switch

brands and complain to manufacturers,

retailers, and other consumers about the

product (Peter and Olson, 1987, p. 512).

Satisfaction of customers also happens to be

the cheapest means of promotion. Various

researchers have found this ratio to range

from about 10 to 1 (Knutson, 1988, p. 17) to 5 to

1 (Naumann, 1995, p. 22).

There are several ways to assess the

quality of services and customer satisfaction

through subjective, or soft, measures of

quality, which focus on perceptions and

attitudes of the customer rather than more

concrete objective criteria. These soft mea-

sures include customer satisfaction surveys

and questionnaires to determine customer

attitudes and perceptions of the quality of the

service they are receiving (Hayes, 1997, p. 2).

Because the extent to which goods or services

meet the customer's needs and requirements

is the index by which quality is determined,

customers' perceptions of service is vital in

identifying customer needs and satisfaction.

To be successful, a customer satisfaction

measurement (CSM) programme must come

from and be incorporated into the firm's

corporate culture (Naumann, 1995, p. 12). In

today's competitive environment one of the

most important goals of corporate cultures is

retaining and satisfying current and past

customers. Experience shows that only

``consumer oriented'' corporations can

achieve this goal. These companies focus on

the needs and wants of specific target groups

and then work hard to maximize satisfaction

with the product or service being offered

(Vavra, 1997, p. 12). Instead of waiting for

customer complaints to let them know when

something isn't satisfactory or wrong, a

The current issue and fulltext archive of this journalis availableat

http://www.emerald-library.com

[ 326 ]

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [ 1999] 326±339

# MCB University Press

[ISSN 0959-6119]

Keywords

Customer satisfaction,

Service quality,

Hospitality industry.

Abstract

Reviews and discusses the topic

of customer satisfaction and its

application to the hospitality and

tourism industries. Defines the

concept and analyzes its impor-

tance to services in general and to

hospitality/tourism services in

particular. Following a discussion

on the dimensions and attributes

of satisfaction, lists the main

methods of measuring satisfaction

and concludes with a review of

globaland cross-cultural issues

that affect satisfaction.

This article is partially

based on a previous article

published by one of the

current authors, Abraham

Pizam, and titled:

``Monitoring customer

satisfaction'', in Davis, B.E.

and Lockwood, A.J. (Eds),

Food and Beverage

Management: A Selection of

Readings, London,

Butterworth Heinemann,

1994, pp. 231-47.

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

``consumer oriented'' corporate culture, seeks

continuous feedback from its customers

through repeated customer satisfaction

measurements (Vavra, 1997, p. 13).

In reality, application of CSM often does

not accomplish the objectives of the

researcher or company. The reasons for this

shortfall are numerous. First, organizations

often set customer satisfaction goals without

any clear understanding of their current

customers' satisfaction levels (Dutka, 1994).

Second, The companies that do measure

customer satisfaction, don't always act on the

results obtained (Dutka, 1994). Finally, as

organizations become more experienced with

CSM, problems become increasingly appar-

ent. For example, Jones and Sasser (1995)

indicate that satisfaction data does not

always correlate highly with organizational

performance. This was supported by

customers who responded that they were

satisfied with the organization, yet

purchased goods and services elsewhere.

Finding a strong relationship between

satisfaction scores and performance does not

ensure economic success. In the long run the

level of satisfaction may decline, customers'

attitudes and desires change, and new

competition may emerge.

Quality may no longer provide a clear

competitive advantage. Butz and Goodstein

(1996), found that increasing numbers of

managers reported that product innovation

and quality no longer provided the basis for a

competitive advantage. Because of this

situation, the search for a competitive

advantage has shifted from internal

processes and structure to markets and

customers. As a result there has been an

increasing number of organizations that are

reorienting strategy toward superior value

delivery (Band, 1991; Day, 1990; Gale, 1994;

Naumann, 1995). These authors usually cite

one or more of the following four kinds of

evidence to support their position:

(1) Widely publicized success stories (e.g.

AT&T, Federal Express, Xerox, Eastman

Chemical Company);

(2) analysis of profit impact of marketing

strategy (PIMS) data that shows a strong

relationship between quality, market

share, and profitability (Gale, 1994);

(3) studies finding a positive relationship

between market orientation and organi-

zational performance (Jaworski and

Kohli, 1993; Narver and Slater, 1990); and

(4) analyses of costs demonstrating that

customer retention is substantially less

expensive than customer acquisition

(Birch, 1990). Because of all the over-

whelming number of authors encouraging

organizations to provide customer value,

the question becomes how to do it? This

paper will provide valid methods that an

organization can use to measure the value

it provides to its customers.

What is customer satisfaction?

Social psychologists, marketing researchers,

and students of consumer behaviour, have

extensively studied the concepts of customer

satisfaction and dissatisfaction. The increas-

ing importance of quality in both service and

manufacturing industries has also created a

proliferation of research, with more than

15,000 academic and trade articles having

been published on the topic of customer

satisfaction in the past two decades (Peterson

and Wilson, 1992). Several conferences have

been devoted to the subject and extensive

literature reviews have been published (Day,

1977; Hunt, 1977; LaTour and Peat, 1979;

Smart, 1982; Ross, et al., 1987, Barsky, 1992:

Oh and Parks, 1997) The result of all this

research has been the development of nine

distinct theories of customer satisfaction.

The majority of these theories are based on

cognitive psychology, some have received

moderate attention, while other theories

have been introduced without any empirical

research. The nine theories include:

1 expectancy disconfirmation;

2 assimilation or cognitive dissonance;

3 contrast;

4 assimilation-contrast;

5 equity;

6 attribution;

7 comparison-level;

8 generalized negativity; and

9 value-precept (Oh and Parks, 1997).

Recently, numerous researchers have

attempted to apply CS theories developed by

consumer behaviourists in the areas of lod-

ging (Barsky, 1992; Barsky and Labagh, 1992;

Saleh and Ryan, 1991; Ekinci and Riley, 1998),

restaurant (Dube et al., 1994; Bojanic and

Rosen, 1994; Lee and Hing, 1995; Oh and

Jeong, 1996), foodservice (Almanza et al.,

1994), and tourism (Pizam and Milman, 1993;

Danaher and Arweiler, 1996; Ryan and Cliff,

1997; Hudson and Shepard, 1998) in order to

investigate CS applicability to the hospitality

and tourism industries.

Customer satisfaction is a psychological

concept that involves the feeling of well-being

and pleasure that results from obtaining

what one hopes for and expects from an

appealing product and/or service (WTO,

1985). While there are a variety of approaches

to the explanation of customer satisfaction/

dissatisfaction, the most widely used is the

one proposed by Richard Oliver who has

[ 327 ]

Abraham Pizam and

Taylor Ellis

Customer satisfaction and its

measurement in hospitality

enterprises

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [1999] 326±339

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

continuous feedback from its customers

through repeated customer satisfaction

measurements (Vavra, 1997, p. 13).

In reality, application of CSM often does

not accomplish the objectives of the

researcher or company. The reasons for this

shortfall are numerous. First, organizations

often set customer satisfaction goals without

any clear understanding of their current

customers' satisfaction levels (Dutka, 1994).

Second, The companies that do measure

customer satisfaction, don't always act on the

results obtained (Dutka, 1994). Finally, as

organizations become more experienced with

CSM, problems become increasingly appar-

ent. For example, Jones and Sasser (1995)

indicate that satisfaction data does not

always correlate highly with organizational

performance. This was supported by

customers who responded that they were

satisfied with the organization, yet

purchased goods and services elsewhere.

Finding a strong relationship between

satisfaction scores and performance does not

ensure economic success. In the long run the

level of satisfaction may decline, customers'

attitudes and desires change, and new

competition may emerge.

Quality may no longer provide a clear

competitive advantage. Butz and Goodstein

(1996), found that increasing numbers of

managers reported that product innovation

and quality no longer provided the basis for a

competitive advantage. Because of this

situation, the search for a competitive

advantage has shifted from internal

processes and structure to markets and

customers. As a result there has been an

increasing number of organizations that are

reorienting strategy toward superior value

delivery (Band, 1991; Day, 1990; Gale, 1994;

Naumann, 1995). These authors usually cite

one or more of the following four kinds of

evidence to support their position:

(1) Widely publicized success stories (e.g.

AT&T, Federal Express, Xerox, Eastman

Chemical Company);

(2) analysis of profit impact of marketing

strategy (PIMS) data that shows a strong

relationship between quality, market

share, and profitability (Gale, 1994);

(3) studies finding a positive relationship

between market orientation and organi-

zational performance (Jaworski and

Kohli, 1993; Narver and Slater, 1990); and

(4) analyses of costs demonstrating that

customer retention is substantially less

expensive than customer acquisition

(Birch, 1990). Because of all the over-

whelming number of authors encouraging

organizations to provide customer value,

the question becomes how to do it? This

paper will provide valid methods that an

organization can use to measure the value

it provides to its customers.

What is customer satisfaction?

Social psychologists, marketing researchers,

and students of consumer behaviour, have

extensively studied the concepts of customer

satisfaction and dissatisfaction. The increas-

ing importance of quality in both service and

manufacturing industries has also created a

proliferation of research, with more than

15,000 academic and trade articles having

been published on the topic of customer

satisfaction in the past two decades (Peterson

and Wilson, 1992). Several conferences have

been devoted to the subject and extensive

literature reviews have been published (Day,

1977; Hunt, 1977; LaTour and Peat, 1979;

Smart, 1982; Ross, et al., 1987, Barsky, 1992:

Oh and Parks, 1997) The result of all this

research has been the development of nine

distinct theories of customer satisfaction.

The majority of these theories are based on

cognitive psychology, some have received

moderate attention, while other theories

have been introduced without any empirical

research. The nine theories include:

1 expectancy disconfirmation;

2 assimilation or cognitive dissonance;

3 contrast;

4 assimilation-contrast;

5 equity;

6 attribution;

7 comparison-level;

8 generalized negativity; and

9 value-precept (Oh and Parks, 1997).

Recently, numerous researchers have

attempted to apply CS theories developed by

consumer behaviourists in the areas of lod-

ging (Barsky, 1992; Barsky and Labagh, 1992;

Saleh and Ryan, 1991; Ekinci and Riley, 1998),

restaurant (Dube et al., 1994; Bojanic and

Rosen, 1994; Lee and Hing, 1995; Oh and

Jeong, 1996), foodservice (Almanza et al.,

1994), and tourism (Pizam and Milman, 1993;

Danaher and Arweiler, 1996; Ryan and Cliff,

1997; Hudson and Shepard, 1998) in order to

investigate CS applicability to the hospitality

and tourism industries.

Customer satisfaction is a psychological

concept that involves the feeling of well-being

and pleasure that results from obtaining

what one hopes for and expects from an

appealing product and/or service (WTO,

1985). While there are a variety of approaches

to the explanation of customer satisfaction/

dissatisfaction, the most widely used is the

one proposed by Richard Oliver who has

[ 327 ]

Abraham Pizam and

Taylor Ellis

Customer satisfaction and its

measurement in hospitality

enterprises

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [1999] 326±339

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

developed the expectancy disconfirmation

theory (Oliver, 1980). According to this

theory, which has been tested and confirmed

in several studies (Oliver and DeSarbo, 1988;

Tse and Wilton, 1988), customers purchase

goods and services with pre-purchase expec-

tations about anticipated performance. Once

the product or service has been purchased

and used, outcomes are compared against

expectations. When outcome matches expec-

tations, confirmation occurs. Discon-

firmation occurs when there are differences

between expectations and outcomes.

Negative disconfirmation occurs when

product/service performance is less than

expected. Positive disconfirmation occurs

when product/service performance is better

than expected. Satisfaction is caused by

confirmation or positive disconfirmation of

consumer expectations, and dissatisfaction is

caused by negative disconfirmation of

consumer expectations.

Customer satisfaction can also be defined

as satisfaction based on an outcome or a

process. Vavra's (1997, p. 4) outcome defini-

tion of customer satisfaction characterizes

satisfaction as the end-state resulting from

the experience of consumption. This end

state may be a cognitive state of reward, an

emotional response to an experience or a

comparison of rewards and costs to the

anticipated consequences. Vavra also puts

forth a definition of customer satisfaction

based as a process, emphasizing the percep-

tual, evaluative and psychological processes

contributing to customer satisfaction (1997,

p. 4). In this definition, assessment of satis-

faction is made during the service delivery

process.

A minority of researchers perceive the

satisfaction process to be subjective in ex-

pectations but objective in the perceptions of

the product attributes, or outcome. Thus,

Klaus (1985, p. 21) defines satisfaction as ``the

customer's subjective evaluation of a

consumption experience, based on some

relationship between the customer's percep-

tions and objective attributes of the product''.

Others point out that both what is perceived

(outcome) and what is expected are subjec-

tive and therefore psychological phenomena -

not reality (Maister, 1985). The importance of

the subjective nature of the process cannot be

overstated. Since both expectations and

perceptions are psychological phenomena,

they are both susceptible to external influ-

ences and manipulation. As an illustration of

how expectations can be explicitly manipu-

lated Sasser et al. (1979, p. 89) note that:

``Some restaurants follow the practice of

promising guests a waiting time in excess of

the ``expected time''. If people are willing to

agree to wait this length of time, they are

quite pleased to be seated earlier, thus

starting the meal with a more positive

feeling'' (Maister, 1985, p.114). An example of

creating low customer expectations is a

restaurant in Orlando, Florida, which calls

itself Warm Beer & Lousy Food. Once a

customer has experienced a reasonable meal

at the above restaurant he/she is pleasantly

surprised and comes out very satisfied.

Manipulating perceptions of outcome is also

a common practice in some hotels where

front office clerks mention nonchalantly that

a particular suite in the hotel is a favorite of a

famous personality. The intention here is to

influence the perception of the customer and

suggest that the hotel must be good since an

``expert'' regularly frequents it.

Satisfaction is not a universal phenomenon

and not everyone gets the same satisfaction

out of the same hospitality experience. The

reason is that customers have different

needs, objectives and past experiences that

influence their expectations. To a student on

a limited budget, a lunch composed of fast

food items at the crowded and noisy school

cafeteria may be a highly satisfying experi-

ence, while the same experience may be

perceived as totally dissatisfying to an

affluent executive discussing a business

transaction. The same customer may also

have different needs and expectations on

different meal occasions, or at different times

of the day (Davis and Stone, 1985, p. 31). The

student in our previous example will not be

highly satisfied when his college friends take

him out for a ``birthday'' meal celebration at

the school cafeteria. Therefore it is important

to gain a clear idea of the customer needs and

objectives that correspond to different kinds

of satisfactions. This necessitates the

segmentation of the market, because no

service or product can offer everyone the

same degree of satisfaction (WTO, 1985).

To recapitulate what we have established

by now is that an individual's satisfaction

with outcomes received from a hospitality

experience results from a comparison of

these outcomes with expectations. Expecta-

tions can be described as a mutable internal

standard which is based on a multitude of

factors including needs, objectives, past

personal or vicarious experiences with the

same establishment restaurant, with similar

establishments, and the availability of alter-

natives (i.e. are there any other establish-

ments in town?). This view is supported by

Mazursky who suggests that:

Experiences beyond those with the focal

brands may lead to different normative

standards employed by consumers in evalu-

ating performance. Possible norms, according

[ 328 ]

Abraham Pizam and

Taylor Ellis

Customer satisfaction and its

measurement in hospitality

enterprises

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [1999] 326±339

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

theory (Oliver, 1980). According to this

theory, which has been tested and confirmed

in several studies (Oliver and DeSarbo, 1988;

Tse and Wilton, 1988), customers purchase

goods and services with pre-purchase expec-

tations about anticipated performance. Once

the product or service has been purchased

and used, outcomes are compared against

expectations. When outcome matches expec-

tations, confirmation occurs. Discon-

firmation occurs when there are differences

between expectations and outcomes.

Negative disconfirmation occurs when

product/service performance is less than

expected. Positive disconfirmation occurs

when product/service performance is better

than expected. Satisfaction is caused by

confirmation or positive disconfirmation of

consumer expectations, and dissatisfaction is

caused by negative disconfirmation of

consumer expectations.

Customer satisfaction can also be defined

as satisfaction based on an outcome or a

process. Vavra's (1997, p. 4) outcome defini-

tion of customer satisfaction characterizes

satisfaction as the end-state resulting from

the experience of consumption. This end

state may be a cognitive state of reward, an

emotional response to an experience or a

comparison of rewards and costs to the

anticipated consequences. Vavra also puts

forth a definition of customer satisfaction

based as a process, emphasizing the percep-

tual, evaluative and psychological processes

contributing to customer satisfaction (1997,

p. 4). In this definition, assessment of satis-

faction is made during the service delivery

process.

A minority of researchers perceive the

satisfaction process to be subjective in ex-

pectations but objective in the perceptions of

the product attributes, or outcome. Thus,

Klaus (1985, p. 21) defines satisfaction as ``the

customer's subjective evaluation of a

consumption experience, based on some

relationship between the customer's percep-

tions and objective attributes of the product''.

Others point out that both what is perceived

(outcome) and what is expected are subjec-

tive and therefore psychological phenomena -

not reality (Maister, 1985). The importance of

the subjective nature of the process cannot be

overstated. Since both expectations and

perceptions are psychological phenomena,

they are both susceptible to external influ-

ences and manipulation. As an illustration of

how expectations can be explicitly manipu-

lated Sasser et al. (1979, p. 89) note that:

``Some restaurants follow the practice of

promising guests a waiting time in excess of

the ``expected time''. If people are willing to

agree to wait this length of time, they are

quite pleased to be seated earlier, thus

starting the meal with a more positive

feeling'' (Maister, 1985, p.114). An example of

creating low customer expectations is a

restaurant in Orlando, Florida, which calls

itself Warm Beer & Lousy Food. Once a

customer has experienced a reasonable meal

at the above restaurant he/she is pleasantly

surprised and comes out very satisfied.

Manipulating perceptions of outcome is also

a common practice in some hotels where

front office clerks mention nonchalantly that

a particular suite in the hotel is a favorite of a

famous personality. The intention here is to

influence the perception of the customer and

suggest that the hotel must be good since an

``expert'' regularly frequents it.

Satisfaction is not a universal phenomenon

and not everyone gets the same satisfaction

out of the same hospitality experience. The

reason is that customers have different

needs, objectives and past experiences that

influence their expectations. To a student on

a limited budget, a lunch composed of fast

food items at the crowded and noisy school

cafeteria may be a highly satisfying experi-

ence, while the same experience may be

perceived as totally dissatisfying to an

affluent executive discussing a business

transaction. The same customer may also

have different needs and expectations on

different meal occasions, or at different times

of the day (Davis and Stone, 1985, p. 31). The

student in our previous example will not be

highly satisfied when his college friends take

him out for a ``birthday'' meal celebration at

the school cafeteria. Therefore it is important

to gain a clear idea of the customer needs and

objectives that correspond to different kinds

of satisfactions. This necessitates the

segmentation of the market, because no

service or product can offer everyone the

same degree of satisfaction (WTO, 1985).

To recapitulate what we have established

by now is that an individual's satisfaction

with outcomes received from a hospitality

experience results from a comparison of

these outcomes with expectations. Expecta-

tions can be described as a mutable internal

standard which is based on a multitude of

factors including needs, objectives, past

personal or vicarious experiences with the

same establishment restaurant, with similar

establishments, and the availability of alter-

natives (i.e. are there any other establish-

ments in town?). This view is supported by

Mazursky who suggests that:

Experiences beyond those with the focal

brands may lead to different normative

standards employed by consumers in evalu-

ating performance. Possible norms, according

[ 328 ]

Abraham Pizam and

Taylor Ellis

Customer satisfaction and its

measurement in hospitality

enterprises

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [1999] 326±339

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

to this view, include perceived best brand, the

most recently used brand, a brand used by a

reference person, products competing for the

same needs, and the like (p. 338).

Changes in satisfaction with the meal

experience may result from changes in the

perception of the actual quality of outcomes

received, or from changes in the expectations

against which these outcomes are compared.

Alterations in the expectations can result

from change in needs (i.e. hungry versus full;

tired versus rested) change of objectives (i.e.

business trip vs leisure trip), new personal or

vicarious experiences (i.e. recently had a

superb hospitality experience at another

hotel) and any other influences that make

salient a particular quality of outcomes (i.e.

it's a very hot day and the restaurant is not

air conditioned) (McCallum and Harrison,

1985).

Past research in customer satisfaction and

service quality has resulted in increasing

research efforts to look at new ways to

evaluate these concepts. Historically, the

assumption has been that a linear relation-

ship exists between satisfaction/dissatis-

faction and disconfirmation or performance

evaluations. Researchers such as Oliva et al.

(1992) proposed a catastrophe model theoriz-

ing the nature of the relationship of satis-

faction with transaction costs and brand

loyalty. This theory hypothesizes that satis-

faction and dissatisfaction occur at different

points, specifically these behaviours are

associated with transaction costs and brand

loyalty and are not monotonic. Research by

various authors (Cronin and Taylor, 1992;

Oliver and Swan, 1989; Cadotte et al., 1987)

using structural modelling, found underlying

causal dynamics among Customer Service

model constructs. The result of this discovery

is that CS researchers must, determine a

generalizable causal relationship among

model constructs and identify a representa-

tive parsimonious CS structural model.

The components of satisfaction

Unlike material products or pure services,

most hospitality experiences are an amalgam

of products and services. Therefore it is

possible to say that satisfaction with a

hospitality experience such as a hotel stay or

a restaurant meal is a sum total of satis-

factions with the individual elements or

attributes of all the products and services

that make up the experience.

There is no uniformity of opinion among

marketing experts as to the classification of

the elements in service encounters. Reuland

et al. (1985, p. 142) suggest that hospitality

services consist of a harmonious mixture of

three elements: the material product in a

narrow sense which in the case of a restau-

rant is the food and beverages; the behaviour

and attitude of the employees who are

responsible for hosting the guest, serving the

meal and beverages and who come in direct

contact with the guests, and the environ-

ment, such as the building, the layout, the

furnishing, the lighting in the restaurant, etc.

Czepiel et al. (1985) on the other hand,

suggest that satisfaction with a service is a

function of satisfaction with two independent

elements. The functional element, i.e. the

food and beverage in a restaurant, and the

performance-delivery element, i.e. the

service. To prove the independence of the two

elements from each other, the authors claim

that restaurant clients are quite capable of

having responses to each element that differ

one from the other: ``The service was great,

the food poor'' or conversely... (p. 13).

Davis and Stone (1985, p.29) divide the

service encounter into two elements: direct

and indirect services. For example, direct

services may be the actual check-in/check-

out process in hotels, while the indirect

services include the provision of parking

facilities, concierge, public telephones for

guests' use, etc.

Lovelock (1985) divides the service attri-

butes into two groups: core and secondary.

Airline service provides a good example, with

customers first making inquiries and reser-

vations, then checking in their baggage,

getting seat assignments, being checked at the

gate, receiving on-board service in flight, and

retrieving their baggage at the destination

airport. Each of these activities is an opera-

tions task that is secondary to the core

product of physically transporting passengers

and their bags between two airports. But

these secondary tasks have a greater poten-

tial to generate customer dissatisfaction if

performed poorly (p. 272).

In a restaurant situation Lovelock's core will

be composed of the food and beverage, while

his secondary will be composed of everything

else, including service, environment, etc.

Lewis (1987), too, classifies the service

encounter attributes in two groups: essential

and subsidiary. The essential attributes are

identical to Czepiel's functional, Davis and

Stone's direct, Reuland and colleagues' pro-

duct, and Lovelock's core, i.e. the food and

beverage in the meal experience. On the

other hand Lewis's subsidiary attributes are

more comprehensive than either Davis and

Stone's indirect, Czepiel's performance-

delivery, or Lovelock's secondary, and

include such factors as: accessibility,

convenience of location, availability and

timing and flexibility, as well as interactions

[ 329 ]

Abraham Pizam and

Taylor Ellis

Customer satisfaction and its

measurement in hospitality

enterprises

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [1999] 326±339

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

most recently used brand, a brand used by a

reference person, products competing for the

same needs, and the like (p. 338).

Changes in satisfaction with the meal

experience may result from changes in the

perception of the actual quality of outcomes

received, or from changes in the expectations

against which these outcomes are compared.

Alterations in the expectations can result

from change in needs (i.e. hungry versus full;

tired versus rested) change of objectives (i.e.

business trip vs leisure trip), new personal or

vicarious experiences (i.e. recently had a

superb hospitality experience at another

hotel) and any other influences that make

salient a particular quality of outcomes (i.e.

it's a very hot day and the restaurant is not

air conditioned) (McCallum and Harrison,

1985).

Past research in customer satisfaction and

service quality has resulted in increasing

research efforts to look at new ways to

evaluate these concepts. Historically, the

assumption has been that a linear relation-

ship exists between satisfaction/dissatis-

faction and disconfirmation or performance

evaluations. Researchers such as Oliva et al.

(1992) proposed a catastrophe model theoriz-

ing the nature of the relationship of satis-

faction with transaction costs and brand

loyalty. This theory hypothesizes that satis-

faction and dissatisfaction occur at different

points, specifically these behaviours are

associated with transaction costs and brand

loyalty and are not monotonic. Research by

various authors (Cronin and Taylor, 1992;

Oliver and Swan, 1989; Cadotte et al., 1987)

using structural modelling, found underlying

causal dynamics among Customer Service

model constructs. The result of this discovery

is that CS researchers must, determine a

generalizable causal relationship among

model constructs and identify a representa-

tive parsimonious CS structural model.

The components of satisfaction

Unlike material products or pure services,

most hospitality experiences are an amalgam

of products and services. Therefore it is

possible to say that satisfaction with a

hospitality experience such as a hotel stay or

a restaurant meal is a sum total of satis-

factions with the individual elements or

attributes of all the products and services

that make up the experience.

There is no uniformity of opinion among

marketing experts as to the classification of

the elements in service encounters. Reuland

et al. (1985, p. 142) suggest that hospitality

services consist of a harmonious mixture of

three elements: the material product in a

narrow sense which in the case of a restau-

rant is the food and beverages; the behaviour

and attitude of the employees who are

responsible for hosting the guest, serving the

meal and beverages and who come in direct

contact with the guests, and the environ-

ment, such as the building, the layout, the

furnishing, the lighting in the restaurant, etc.

Czepiel et al. (1985) on the other hand,

suggest that satisfaction with a service is a

function of satisfaction with two independent

elements. The functional element, i.e. the

food and beverage in a restaurant, and the

performance-delivery element, i.e. the

service. To prove the independence of the two

elements from each other, the authors claim

that restaurant clients are quite capable of

having responses to each element that differ

one from the other: ``The service was great,

the food poor'' or conversely... (p. 13).

Davis and Stone (1985, p.29) divide the

service encounter into two elements: direct

and indirect services. For example, direct

services may be the actual check-in/check-

out process in hotels, while the indirect

services include the provision of parking

facilities, concierge, public telephones for

guests' use, etc.

Lovelock (1985) divides the service attri-

butes into two groups: core and secondary.

Airline service provides a good example, with

customers first making inquiries and reser-

vations, then checking in their baggage,

getting seat assignments, being checked at the

gate, receiving on-board service in flight, and

retrieving their baggage at the destination

airport. Each of these activities is an opera-

tions task that is secondary to the core

product of physically transporting passengers

and their bags between two airports. But

these secondary tasks have a greater poten-

tial to generate customer dissatisfaction if

performed poorly (p. 272).

In a restaurant situation Lovelock's core will

be composed of the food and beverage, while

his secondary will be composed of everything

else, including service, environment, etc.

Lewis (1987), too, classifies the service

encounter attributes in two groups: essential

and subsidiary. The essential attributes are

identical to Czepiel's functional, Davis and

Stone's direct, Reuland and colleagues' pro-

duct, and Lovelock's core, i.e. the food and

beverage in the meal experience. On the

other hand Lewis's subsidiary attributes are

more comprehensive than either Davis and

Stone's indirect, Czepiel's performance-

delivery, or Lovelock's secondary, and

include such factors as: accessibility,

convenience of location, availability and

timing and flexibility, as well as interactions

[ 329 ]

Abraham Pizam and

Taylor Ellis

Customer satisfaction and its

measurement in hospitality

enterprises

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [1999] 326±339

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

with those providing the service and with

other customers. It is equivalent to a

combination of the behaviour and environ-

ment elements in the Reuland et al. model.

Yet other researchers support the idea that

the service encounter attributes are situa-

tion-specific and as such cannot be classified

into universal elements. For example,

Fiebelkorn (1985) doing a study at Citibank

found that overall satisfaction with Citibank

as one of the customer's banks (or his bank

only) is based on satisfaction with the last

encounter with the bank in five main areas:

teller encounter, platform encounter, ATM

(automatic teller machines) encounter,

phone encounter, problem encounter. He

then concludes that ``the common thread

running through all five service-encounter

types is that customers want: prompt service

by people who know what to do and how to do

it, and who care about them as valued

customers'' (Fiebelkorn, 1985, p. 185).

Dimensions of satisfaction

In service organizations, the assessment of

the quality of a service is made during the

actual delivery of the service ± usually an

encounter between the customer and a

service contact person. Parasuraman et al.

(1985, 1988, 1991) identified the following five

generic dimensions of service quality

(SERVQUAL) that must be present in the

service delivery in order for it to result in

customer satisfaction:

. Reliability ± the ability to perform the

promised services dependably and

accurately.

. Responsiveness ± the willingness to help

customers and provide prompt service.

. Assurance ± the knowledge and courtesy of

employees as well as their ability to

convey trust and confidence.

. Empathy ± the provision of caring,

individualized attention to customers, and

. Tangibles, the appearance of physical

facilities, equipment, personnel and

communication materials.

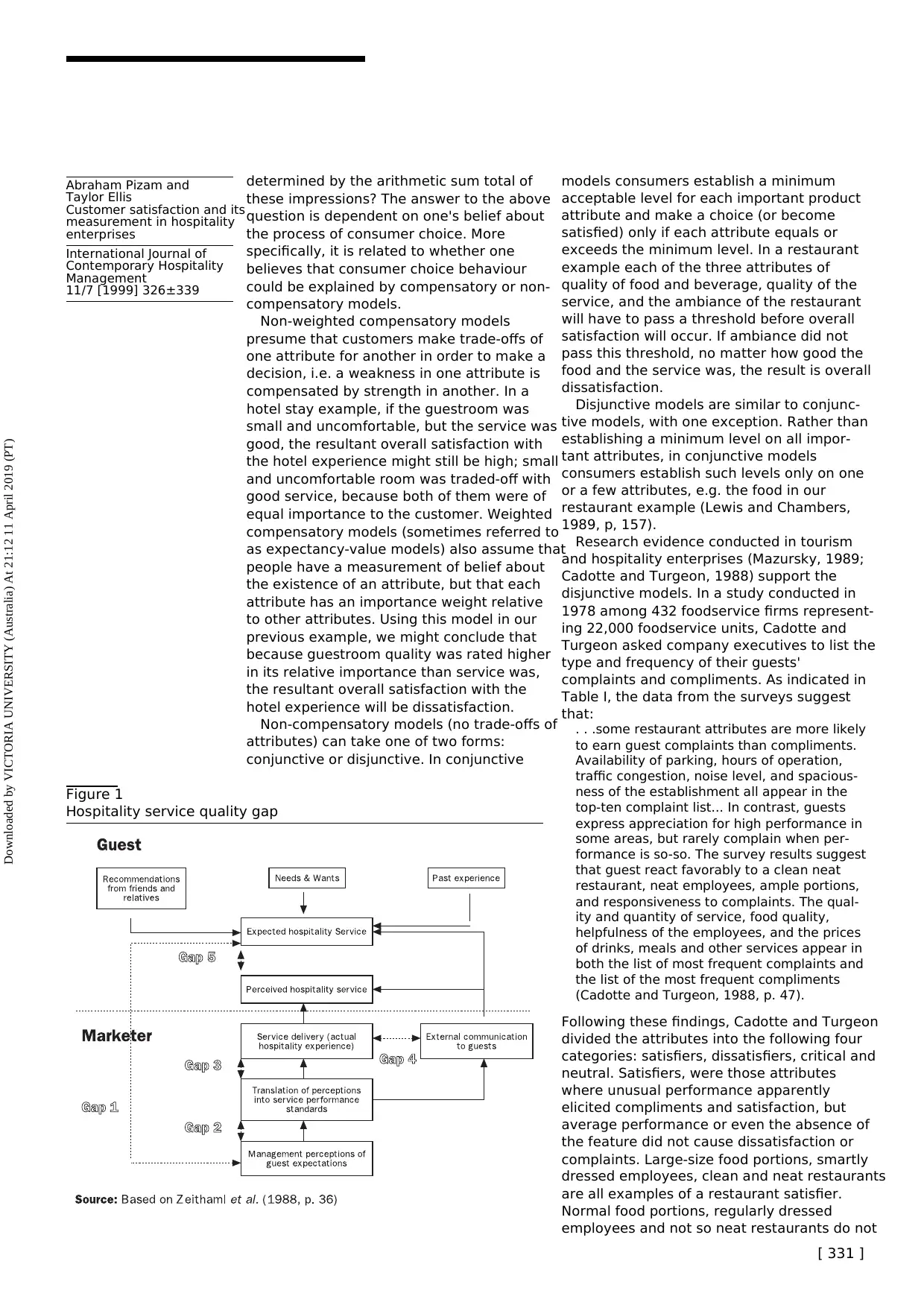

The model conceptualizes service quality as a

gap between customer's expectations (E) and

the perception of the service providers'

performance (P). According to Parasuraman

et al. (1985), service quality should be

measured by subtracting customer's percep-

tion scores from customer expectation scores

(Q = P ± E). The greater the positive score

represents the greater the positive amount of

service quality or visa versa.

The gap that may exist between the custo-

mers' expected and perceived service is not

only a measure of the quality of the service,

but is also a determinant of customer

satisfaction/dissatisfaction. Measuring the

gap between expected and perceived service

is a routine method of utilizing customer

feedback. Zeithaml et al., (1988) suggested a

model that details the gaps between customer

expectations and the actual service delivered.

(see Figure 1). Vavra (1997, p. 91) identified a

sixth gap namely the difference between the

customers' desired service and their expected

service.

Since its introduction in 1988, SERVQUAL

has been used in hundreds of studies includ-

ing numerous studies in the hospitality and

tourism industries (Fick and Ritchie, 1991;

Saleh and Ryan, 1991; Luk et al., 1993; Bojanic

and Rosen, 1994; Lee and Hing, 1995; Ryan

and Cliff, 1997). SERVQUAL was also used by

Knutson et al. (1991) to create a lodging-

specific instrument called LODGSERV which

is a 26 item index designed to measure

consumer expectations for service quality in

the hotel experience. LODGSERV, however,

is not as popular among hospitality and

tourism researchers as SERVQUAL and was

used only in a limited number of studies (i.e.

Patton et al., 1994; Ekinci et al., 1998).

But SERVQUAL has also been seriously

criticized (Carman, 1990; Finn and Lamb,

1991; Babakus and Boller, 1992; Brown et al.,

1993; Smith, 1995). The main criticisms of the

model relate to the application of expecta-

tions and the gap scoring. First, the concep-

tualization of expectation as a comparison

standard in the model is a difficult concept to

quantify. Second, if the variables are difficult

to quantify then, by implication, the gap

score becomes that much less secure as a

measurement. Third, some methodological

issues arise. Finally, doubt has been

expressed as to the universal quality of the

dimensions. (Eckinci and Riley, 1998, p. 355)

Overall satisfaction vs satisfaction

with individual attributes

In the previous section we indicated that it is

possible to say that satisfaction with a

hospitality experience is a sum total of

satisfactions with the individual elements or

attributes of all the products and services

that make up the experience. Though super-

ficially the above statement makes sense, in

reality the matter is more compounded. The

question that we have to ask ourselves is

whether when customers experience the

attributes of the hospitality experience they

form a set of independent impressions on

each and compare those with the expecta-

tions of the same attributes. And, is the

resultant overall level of satisfaction

[ 330 ]

Abraham Pizam and

Taylor Ellis

Customer satisfaction and its

measurement in hospitality

enterprises

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [1999] 326±339

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

other customers. It is equivalent to a

combination of the behaviour and environ-

ment elements in the Reuland et al. model.

Yet other researchers support the idea that

the service encounter attributes are situa-

tion-specific and as such cannot be classified

into universal elements. For example,

Fiebelkorn (1985) doing a study at Citibank

found that overall satisfaction with Citibank

as one of the customer's banks (or his bank

only) is based on satisfaction with the last

encounter with the bank in five main areas:

teller encounter, platform encounter, ATM

(automatic teller machines) encounter,

phone encounter, problem encounter. He

then concludes that ``the common thread

running through all five service-encounter

types is that customers want: prompt service

by people who know what to do and how to do

it, and who care about them as valued

customers'' (Fiebelkorn, 1985, p. 185).

Dimensions of satisfaction

In service organizations, the assessment of

the quality of a service is made during the

actual delivery of the service ± usually an

encounter between the customer and a

service contact person. Parasuraman et al.

(1985, 1988, 1991) identified the following five

generic dimensions of service quality

(SERVQUAL) that must be present in the

service delivery in order for it to result in

customer satisfaction:

. Reliability ± the ability to perform the

promised services dependably and

accurately.

. Responsiveness ± the willingness to help

customers and provide prompt service.

. Assurance ± the knowledge and courtesy of

employees as well as their ability to

convey trust and confidence.

. Empathy ± the provision of caring,

individualized attention to customers, and

. Tangibles, the appearance of physical

facilities, equipment, personnel and

communication materials.

The model conceptualizes service quality as a

gap between customer's expectations (E) and

the perception of the service providers'

performance (P). According to Parasuraman

et al. (1985), service quality should be

measured by subtracting customer's percep-

tion scores from customer expectation scores

(Q = P ± E). The greater the positive score

represents the greater the positive amount of

service quality or visa versa.

The gap that may exist between the custo-

mers' expected and perceived service is not

only a measure of the quality of the service,

but is also a determinant of customer

satisfaction/dissatisfaction. Measuring the

gap between expected and perceived service

is a routine method of utilizing customer

feedback. Zeithaml et al., (1988) suggested a

model that details the gaps between customer

expectations and the actual service delivered.

(see Figure 1). Vavra (1997, p. 91) identified a

sixth gap namely the difference between the

customers' desired service and their expected

service.

Since its introduction in 1988, SERVQUAL

has been used in hundreds of studies includ-

ing numerous studies in the hospitality and

tourism industries (Fick and Ritchie, 1991;

Saleh and Ryan, 1991; Luk et al., 1993; Bojanic

and Rosen, 1994; Lee and Hing, 1995; Ryan

and Cliff, 1997). SERVQUAL was also used by

Knutson et al. (1991) to create a lodging-

specific instrument called LODGSERV which

is a 26 item index designed to measure

consumer expectations for service quality in

the hotel experience. LODGSERV, however,

is not as popular among hospitality and

tourism researchers as SERVQUAL and was

used only in a limited number of studies (i.e.

Patton et al., 1994; Ekinci et al., 1998).

But SERVQUAL has also been seriously

criticized (Carman, 1990; Finn and Lamb,

1991; Babakus and Boller, 1992; Brown et al.,

1993; Smith, 1995). The main criticisms of the

model relate to the application of expecta-

tions and the gap scoring. First, the concep-

tualization of expectation as a comparison

standard in the model is a difficult concept to

quantify. Second, if the variables are difficult

to quantify then, by implication, the gap

score becomes that much less secure as a

measurement. Third, some methodological

issues arise. Finally, doubt has been

expressed as to the universal quality of the

dimensions. (Eckinci and Riley, 1998, p. 355)

Overall satisfaction vs satisfaction

with individual attributes

In the previous section we indicated that it is

possible to say that satisfaction with a

hospitality experience is a sum total of

satisfactions with the individual elements or

attributes of all the products and services

that make up the experience. Though super-

ficially the above statement makes sense, in

reality the matter is more compounded. The

question that we have to ask ourselves is

whether when customers experience the

attributes of the hospitality experience they

form a set of independent impressions on

each and compare those with the expecta-

tions of the same attributes. And, is the

resultant overall level of satisfaction

[ 330 ]

Abraham Pizam and

Taylor Ellis

Customer satisfaction and its

measurement in hospitality

enterprises

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [1999] 326±339

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

determined by the arithmetic sum total of

these impressions? The answer to the above

question is dependent on one's belief about

the process of consumer choice. More

specifically, it is related to whether one

believes that consumer choice behaviour

could be explained by compensatory or non-

compensatory models.

Non-weighted compensatory models

presume that customers make trade-offs of

one attribute for another in order to make a

decision, i.e. a weakness in one attribute is

compensated by strength in another. In a

hotel stay example, if the guestroom was

small and uncomfortable, but the service was

good, the resultant overall satisfaction with

the hotel experience might still be high; small

and uncomfortable room was traded-off with

good service, because both of them were of

equal importance to the customer. Weighted

compensatory models (sometimes referred to

as expectancy-value models) also assume that

people have a measurement of belief about

the existence of an attribute, but that each

attribute has an importance weight relative

to other attributes. Using this model in our

previous example, we might conclude that

because guestroom quality was rated higher

in its relative importance than service was,

the resultant overall satisfaction with the

hotel experience will be dissatisfaction.

Non-compensatory models (no trade-offs of

attributes) can take one of two forms:

conjunctive or disjunctive. In conjunctive

models consumers establish a minimum

acceptable level for each important product

attribute and make a choice (or become

satisfied) only if each attribute equals or

exceeds the minimum level. In a restaurant

example each of the three attributes of

quality of food and beverage, quality of the

service, and the ambiance of the restaurant

will have to pass a threshold before overall

satisfaction will occur. If ambiance did not

pass this threshold, no matter how good the

food and the service was, the result is overall

dissatisfaction.

Disjunctive models are similar to conjunc-

tive models, with one exception. Rather than

establishing a minimum level on all impor-

tant attributes, in conjunctive models

consumers establish such levels only on one

or a few attributes, e.g. the food in our

restaurant example (Lewis and Chambers,

1989, p, 157).

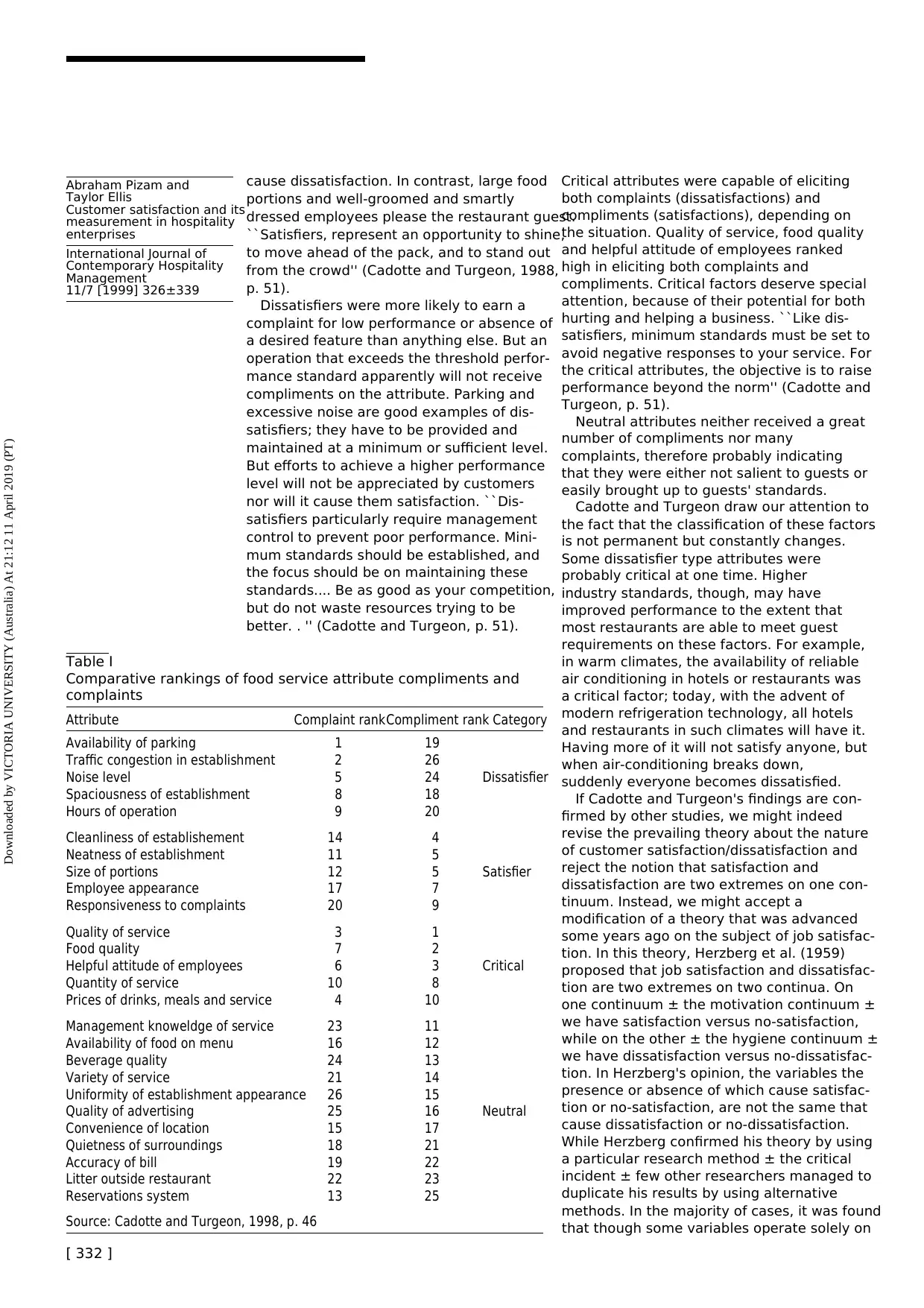

Research evidence conducted in tourism

and hospitality enterprises (Mazursky, 1989;

Cadotte and Turgeon, 1988) support the

disjunctive models. In a study conducted in

1978 among 432 foodservice firms represent-

ing 22,000 foodservice units, Cadotte and

Turgeon asked company executives to list the

type and frequency of their guests'

complaints and compliments. As indicated in

Table I, the data from the surveys suggest

that:

. . .some restaurant attributes are more likely

to earn guest complaints than compliments.

Availability of parking, hours of operation,

traffic congestion, noise level, and spacious-

ness of the establishment all appear in the

top-ten complaint list... In contrast, guests

express appreciation for high performance in

some areas, but rarely complain when per-

formance is so-so. The survey results suggest

that guest react favorably to a clean neat

restaurant, neat employees, ample portions,

and responsiveness to complaints. The qual-

ity and quantity of service, food quality,

helpfulness of the employees, and the prices

of drinks, meals and other services appear in

both the list of most frequent complaints and

the list of the most frequent compliments

(Cadotte and Turgeon, 1988, p. 47).

Following these findings, Cadotte and Turgeon

divided the attributes into the following four

categories: satisfiers, dissatisfiers, critical and

neutral. Satisfiers, were those attributes

where unusual performance apparently

elicited compliments and satisfaction, but

average performance or even the absence of

the feature did not cause dissatisfaction or

complaints. Large-size food portions, smartly

dressed employees, clean and neat restaurants

are all examples of a restaurant satisfier.

Normal food portions, regularly dressed

employees and not so neat restaurants do not

Figure 1

Hospitality service quality gap

[ 331 ]

Abraham Pizam and

Taylor Ellis

Customer satisfaction and its

measurement in hospitality

enterprises

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [1999] 326±339

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

these impressions? The answer to the above

question is dependent on one's belief about

the process of consumer choice. More

specifically, it is related to whether one

believes that consumer choice behaviour

could be explained by compensatory or non-

compensatory models.

Non-weighted compensatory models

presume that customers make trade-offs of

one attribute for another in order to make a

decision, i.e. a weakness in one attribute is

compensated by strength in another. In a

hotel stay example, if the guestroom was

small and uncomfortable, but the service was

good, the resultant overall satisfaction with

the hotel experience might still be high; small

and uncomfortable room was traded-off with

good service, because both of them were of

equal importance to the customer. Weighted

compensatory models (sometimes referred to

as expectancy-value models) also assume that

people have a measurement of belief about

the existence of an attribute, but that each

attribute has an importance weight relative

to other attributes. Using this model in our

previous example, we might conclude that

because guestroom quality was rated higher

in its relative importance than service was,

the resultant overall satisfaction with the

hotel experience will be dissatisfaction.

Non-compensatory models (no trade-offs of

attributes) can take one of two forms:

conjunctive or disjunctive. In conjunctive

models consumers establish a minimum

acceptable level for each important product

attribute and make a choice (or become

satisfied) only if each attribute equals or

exceeds the minimum level. In a restaurant

example each of the three attributes of

quality of food and beverage, quality of the

service, and the ambiance of the restaurant

will have to pass a threshold before overall

satisfaction will occur. If ambiance did not

pass this threshold, no matter how good the

food and the service was, the result is overall

dissatisfaction.

Disjunctive models are similar to conjunc-

tive models, with one exception. Rather than

establishing a minimum level on all impor-

tant attributes, in conjunctive models

consumers establish such levels only on one

or a few attributes, e.g. the food in our

restaurant example (Lewis and Chambers,

1989, p, 157).

Research evidence conducted in tourism

and hospitality enterprises (Mazursky, 1989;

Cadotte and Turgeon, 1988) support the

disjunctive models. In a study conducted in

1978 among 432 foodservice firms represent-

ing 22,000 foodservice units, Cadotte and

Turgeon asked company executives to list the

type and frequency of their guests'

complaints and compliments. As indicated in

Table I, the data from the surveys suggest

that:

. . .some restaurant attributes are more likely

to earn guest complaints than compliments.

Availability of parking, hours of operation,

traffic congestion, noise level, and spacious-

ness of the establishment all appear in the

top-ten complaint list... In contrast, guests

express appreciation for high performance in

some areas, but rarely complain when per-

formance is so-so. The survey results suggest

that guest react favorably to a clean neat

restaurant, neat employees, ample portions,

and responsiveness to complaints. The qual-

ity and quantity of service, food quality,

helpfulness of the employees, and the prices

of drinks, meals and other services appear in

both the list of most frequent complaints and

the list of the most frequent compliments

(Cadotte and Turgeon, 1988, p. 47).

Following these findings, Cadotte and Turgeon

divided the attributes into the following four

categories: satisfiers, dissatisfiers, critical and

neutral. Satisfiers, were those attributes

where unusual performance apparently

elicited compliments and satisfaction, but

average performance or even the absence of

the feature did not cause dissatisfaction or

complaints. Large-size food portions, smartly

dressed employees, clean and neat restaurants

are all examples of a restaurant satisfier.

Normal food portions, regularly dressed

employees and not so neat restaurants do not

Figure 1

Hospitality service quality gap

[ 331 ]

Abraham Pizam and

Taylor Ellis

Customer satisfaction and its

measurement in hospitality

enterprises

International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality

Management

11/7 [1999] 326±339

Downloaded by VICTORIA UNIVERSITY (Australia) At 21:12 11 April 2019 (PT)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

cause dissatisfaction. In contrast, large food

portions and well-groomed and smartly

dressed employees please the restaurant guest.

``Satisfiers, represent an opportunity to shine,

to move ahead of the pack, and to stand out

from the crowd'' (Cadotte and Turgeon, 1988,

p. 51).

Dissatisfiers were more likely to earn a

complaint for low performance or absence of

a desired feature than anything else. But an

operation that exceeds the threshold perfor-

mance standard apparently will not receive

compliments on the attribute. Parking and

excessive noise are good examples of dis-

satisfiers; they have to be provided and

maintained at a minimum or sufficient level.

But efforts to achieve a higher performance

level will not be appreciated by customers

nor will it cause them satisfaction. ``Dis-

satisfiers particularly require management

control to prevent poor performance. Mini-

mum standards should be established, and

the focus should be on maintaining these

standards.... Be as good as your competition,

but do not waste resources trying to be

better. . '' (Cadotte and Turgeon, p. 51).

Critical attributes were capable of eliciting

both complaints (dissatisfactions) and

compliments (satisfactions), depending on

the situation. Quality of service, food quality

and helpful attitude of employees ranked

high in eliciting both complaints and

compliments. Critical factors deserve special

attention, because of their potential for both

hurting and helping a business. ``Like dis-

satisfiers, minimum standards must be set to

avoid negative responses to your service. For

the critical attributes, the objective is to raise

performance beyond the norm'' (Cadotte and

Turgeon, p. 51).

Neutral attributes neither received a great

number of compliments nor many

complaints, therefore probably indicating

that they were either not salient to guests or

easily brought up to guests' standards.

Cadotte and Turgeon draw our attention to

the fact that the classification of these factors

is not permanent but constantly changes.

Some dissatisfier type attributes were

probably critical at one time. Higher

industry standards, though, may have

improved performance to the extent that

most restaurants are able to meet guest