CVD Health Promotion for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander People

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/29

|10

|2850

|24

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a comprehensive needs assessment focusing on cardiovascular disease (CVD) health promotion within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. It begins with an introduction highlighting the significant health disparities in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, emphasizing the critical need for interventions. The report analyzes the health needs of the target population, including the high prevalence of ischemic heart failure, particularly among younger Indigenous Australians, and the associated risk factors. It examines health status, demographic and geographic distributions, social, environmental, and behavioral determinants, and the existing service needs. The assessment also explores workforce availability, efficiency, and effectiveness of current programs. Furthermore, it identifies opportunities, priorities, and options for improvement, culminating in specific recommendations for actions, such as recalibrating risk assessment tools and expanding access to healthcare. Stakeholder analysis is included to demonstrate the involvement of different groups. The report concludes by emphasizing the importance of funding and expanded programs to improve the quality of life for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

Running Head: CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author Note:

CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author Note:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

Introduction:

The new 10-year report of the Closing the Gap Program, aiming at decreasing the gap in life

expectancy between Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders and other Australians by 2031 (Jones), found

that somehow the lifespan with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians increased between

2005–2007 and 2010–2012, but the difference did not significantly reduce, and is still about 10 years old.

The article below reflects on the need to encourage avoidance of cardiovascular disorders by Indigenous

and Torres Strait citizens (Woodruffe et al., 2015). The article also demonstrates the importance of the

particular demographic community and the support required to implement the management and

promotion system (Jones et al., 2018) to increase quality of life.

Discussion:

Analysis of health needs of target population:

Ischaemic heart failure is the main cause of death for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islanders, with a population rate 1.8 times that of non-Indigenous Australians where the percentage for

young people is far higher. These stand at 12.0 percent of heart disease-triggered deaths in 30–39 year old

Aboriginal Australians, relative to 3.8 percent for non-Indigenous citizens in this age range. While the

statistic is observed to be very small in Indigenous communities, it is recommended to add 5 percent to

the calculated 5-year risk score in cultures with lower prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and

disease, whereas in societies with high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and disease it is proposed

that 5 percent be added to the assessed 5-year risk amount. The data given by their population survey

findings from the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Study, taken into account the

incidence of coronary disease and the utilization of lipid-lowering medication among Indigenous

Australians. Investigators recorded that 4.7% of participants aged 25–34 without pre-existing coronary

illness were at elevated extreme risk of cardiovascular disease, greater than the percentage of high

Introduction:

The new 10-year report of the Closing the Gap Program, aiming at decreasing the gap in life

expectancy between Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders and other Australians by 2031 (Jones), found

that somehow the lifespan with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians increased between

2005–2007 and 2010–2012, but the difference did not significantly reduce, and is still about 10 years old.

The article below reflects on the need to encourage avoidance of cardiovascular disorders by Indigenous

and Torres Strait citizens (Woodruffe et al., 2015). The article also demonstrates the importance of the

particular demographic community and the support required to implement the management and

promotion system (Jones et al., 2018) to increase quality of life.

Discussion:

Analysis of health needs of target population:

Ischaemic heart failure is the main cause of death for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islanders, with a population rate 1.8 times that of non-Indigenous Australians where the percentage for

young people is far higher. These stand at 12.0 percent of heart disease-triggered deaths in 30–39 year old

Aboriginal Australians, relative to 3.8 percent for non-Indigenous citizens in this age range. While the

statistic is observed to be very small in Indigenous communities, it is recommended to add 5 percent to

the calculated 5-year risk score in cultures with lower prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and

disease, whereas in societies with high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and disease it is proposed

that 5 percent be added to the assessed 5-year risk amount. The data given by their population survey

findings from the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Study, taken into account the

incidence of coronary disease and the utilization of lipid-lowering medication among Indigenous

Australians. Investigators recorded that 4.7% of participants aged 25–34 without pre-existing coronary

illness were at elevated extreme risk of cardiovascular disease, greater than the percentage of high

2CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

absolute risk (4.0%) among non-Indigenous Australians aged 45–54 years. There was a recurrent

circulatory disease in 12 per cent of the Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander communities. Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander populations were 20 per cent more likely than non-Indigenous Australians to

report circulatory disease. Since 2001, indigenous Australians with a recurrent circulatory condition have

seen a significant increase.

Health status:

Indigenous people are more likely to die from CVD than non-Indigenous residents, with

extremely high mortality risk levels for individuals in both young and middle ages. Coronary heart

disease (CHD), stroke (CBVD), and hypertension are the main medical conditions linked with increased

mortality among indigenous people. Such illnesses make up 76 percent of all cardiovascular deaths.

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), now a rare cause of death in non-Aboriginal Australians, also causes

major deaths within the indigenous population, mainly due to the incidence of acute rheumatic fever

(ARF), especially in children. In 2010, CVD was the leading cause of death for indigenous populations,

responsible for 668 indigenous deaths (26 percent of all indigenous deaths). CHD and CBVD constituted

the two major popular causal factors of death from CVD. CHD accounted for 349 deaths among

indigenous peoples in 2010, 13 per cent of all fatalities and 52 per cent of cardiovascular fatalities among

indigenous peoples (also the leading cause of death for non-indigenous peoples). CHD mortality rates for

indigenous groups were almost twice as high as those for non-indigenous societies (179 deaths per

100,000, compared with 89 deaths per 100,000).

Demography and geography of population:

The Australian Statistics Bureau (ABS) reported the Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander

community at 30 June 2011, based on data gathered as part of the 2011 Community and Housing Survey,

to be 669,736 individuals. This is projected that the NSW population will be the highest (208,364

aboriginal people), followed by Qld (188,892), WA (88,277), and NT (68,901). The NT has the highest

absolute risk (4.0%) among non-Indigenous Australians aged 45–54 years. There was a recurrent

circulatory disease in 12 per cent of the Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander communities. Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander populations were 20 per cent more likely than non-Indigenous Australians to

report circulatory disease. Since 2001, indigenous Australians with a recurrent circulatory condition have

seen a significant increase.

Health status:

Indigenous people are more likely to die from CVD than non-Indigenous residents, with

extremely high mortality risk levels for individuals in both young and middle ages. Coronary heart

disease (CHD), stroke (CBVD), and hypertension are the main medical conditions linked with increased

mortality among indigenous people. Such illnesses make up 76 percent of all cardiovascular deaths.

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), now a rare cause of death in non-Aboriginal Australians, also causes

major deaths within the indigenous population, mainly due to the incidence of acute rheumatic fever

(ARF), especially in children. In 2010, CVD was the leading cause of death for indigenous populations,

responsible for 668 indigenous deaths (26 percent of all indigenous deaths). CHD and CBVD constituted

the two major popular causal factors of death from CVD. CHD accounted for 349 deaths among

indigenous peoples in 2010, 13 per cent of all fatalities and 52 per cent of cardiovascular fatalities among

indigenous peoples (also the leading cause of death for non-indigenous peoples). CHD mortality rates for

indigenous groups were almost twice as high as those for non-indigenous societies (179 deaths per

100,000, compared with 89 deaths per 100,000).

Demography and geography of population:

The Australian Statistics Bureau (ABS) reported the Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander

community at 30 June 2011, based on data gathered as part of the 2011 Community and Housing Survey,

to be 669,736 individuals. This is projected that the NSW population will be the highest (208,364

aboriginal people), followed by Qld (188,892), WA (88,277), and NT (68,901). The NT has the highest

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

number of Indigenous people in the nation (29.8%) and the lowest in Vic (0.9%). The indigenous

community around Australia is far more scattered than the non-indigenous population is. Slightly over

half of the indigenous community resides in regions known as 'big cities' or 'core rural' zones, relative to

about nine-tenths of the non-indigenous people.

Social, environmental, and behavioral health determinants:

There are various triggers of CVD in indigenous people, but the disorder and its symptoms may

well be considerably reduced by modifying behavioural and biochemical risk factors, both of which are

influenced by mitigating factors such as the severe socioeconomic poverty experienced by indigenous

people. Often modifiable risk factors for CVD include smoking, alcohol, physical inactivity, eating,

overweight and obesity, diabetes, increased blood pressure and high blood cholesterol. These risk factors

are strongly associated with nearly 70 per cent of indigenous people's CVD load. Consumption of

nicotine is the key cause that contributes to overweight and obesity, elevated blood cholesterol, physical

inactivity and high blood pressure. For other Australians, a large percentage of the CVD strain is

attributed to the same risk factors, but the major causes are elevated blood pressure and high blood

cholesterol, followed by excessive inactivity, overweight and obesity, alcohol and inadequate

consumption of fruit and vegetables. Improvements in indigenous people's physical activity and nutrition

played a key role in the growth of CVD and diabetes, particularly in the second half of the 20th century,

as major modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease and other chronic conditions (Gubhajuet al.,

2019). Psychosocial problems and illnesses affecting indigenous people's behavioral and emotional well-

being are also considered to be main trigger factors for CVD and contribute to higher incidence. Financial

opportunities, natural infrastructure and socio-economic conditions have a significant effect on the well-

being of people, communities and culture as a whole. In addition, these effects are visible in measures

such as education, jobs, incomes, housing, resource exposure, social networks, land ties, discrimination

and incarceration. Indigenous populations experience significant disadvantage on all these tests.

number of Indigenous people in the nation (29.8%) and the lowest in Vic (0.9%). The indigenous

community around Australia is far more scattered than the non-indigenous population is. Slightly over

half of the indigenous community resides in regions known as 'big cities' or 'core rural' zones, relative to

about nine-tenths of the non-indigenous people.

Social, environmental, and behavioral health determinants:

There are various triggers of CVD in indigenous people, but the disorder and its symptoms may

well be considerably reduced by modifying behavioural and biochemical risk factors, both of which are

influenced by mitigating factors such as the severe socioeconomic poverty experienced by indigenous

people. Often modifiable risk factors for CVD include smoking, alcohol, physical inactivity, eating,

overweight and obesity, diabetes, increased blood pressure and high blood cholesterol. These risk factors

are strongly associated with nearly 70 per cent of indigenous people's CVD load. Consumption of

nicotine is the key cause that contributes to overweight and obesity, elevated blood cholesterol, physical

inactivity and high blood pressure. For other Australians, a large percentage of the CVD strain is

attributed to the same risk factors, but the major causes are elevated blood pressure and high blood

cholesterol, followed by excessive inactivity, overweight and obesity, alcohol and inadequate

consumption of fruit and vegetables. Improvements in indigenous people's physical activity and nutrition

played a key role in the growth of CVD and diabetes, particularly in the second half of the 20th century,

as major modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease and other chronic conditions (Gubhajuet al.,

2019). Psychosocial problems and illnesses affecting indigenous people's behavioral and emotional well-

being are also considered to be main trigger factors for CVD and contribute to higher incidence. Financial

opportunities, natural infrastructure and socio-economic conditions have a significant effect on the well-

being of people, communities and culture as a whole. In addition, these effects are visible in measures

such as education, jobs, incomes, housing, resource exposure, social networks, land ties, discrimination

and incarceration. Indigenous populations experience significant disadvantage on all these tests.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

Analysis of service needs:

In 2010, CVD was the leading cause of death for indigenous peoples, responsible for 668 deaths

of indigenous peoples (26% of all indigenous peoples 'deaths)[5]. CHD and CBVD represented the two

most severe causes of CVD death. For Indigenous males, fatalities from this disease were more frequent

than for Indigenous females, with a sex ratio of 2.1. In 2010, CHD was accounted for 349 indigenous

deaths, 13 per cent of all deaths and 52 per cent of cardiovascular deaths by indigenous citizens. CHD

mortality rates were almost twice as high for Aboriginal populations, than for non-Indigenous

communities. Most of the morbidity and mortality induced by CVD is preventable, both as regards the

early occurrence of the disease (primary prevention) and as regards the treatment and containment of

existing disease (secondary prevention and rehabilitation) (Woodruffe et al., 2015). CVD has attracted

substantial attention in Australia owing to the fairly preventable existence of the disease, and the

subsequent high degree of health risk and expense. This emphasis has contributed to advancements in

cardiovascular health in modern Australia but these innovations have not been completely incorporated

into indigenous cultures. This is illustrated by the continued elevated rates of prevalence, hospitalization,

and mortality in Aboriginal people with CVD.

Cardiovascular Risk Assessment Program for Aboriginal & Torres Islander

Traits:

Australia's total cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk evaluation algorithm(Paigea et al., 2019) first

determines which people follow the requirements for a scientifically defined elevated risk of CVD and,

among those that do not fulfill such requirements, the Framingham Risk Equation applies to predict an

individual's risk of CVD over the next 5 years. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and non-

Indigenous Australians, the same risk calculation is used, but there is difference in inherent vulnerability

between the two groups, with the former facing a larger prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors.

Analysis of service needs:

In 2010, CVD was the leading cause of death for indigenous peoples, responsible for 668 deaths

of indigenous peoples (26% of all indigenous peoples 'deaths)[5]. CHD and CBVD represented the two

most severe causes of CVD death. For Indigenous males, fatalities from this disease were more frequent

than for Indigenous females, with a sex ratio of 2.1. In 2010, CHD was accounted for 349 indigenous

deaths, 13 per cent of all deaths and 52 per cent of cardiovascular deaths by indigenous citizens. CHD

mortality rates were almost twice as high for Aboriginal populations, than for non-Indigenous

communities. Most of the morbidity and mortality induced by CVD is preventable, both as regards the

early occurrence of the disease (primary prevention) and as regards the treatment and containment of

existing disease (secondary prevention and rehabilitation) (Woodruffe et al., 2015). CVD has attracted

substantial attention in Australia owing to the fairly preventable existence of the disease, and the

subsequent high degree of health risk and expense. This emphasis has contributed to advancements in

cardiovascular health in modern Australia but these innovations have not been completely incorporated

into indigenous cultures. This is illustrated by the continued elevated rates of prevalence, hospitalization,

and mortality in Aboriginal people with CVD.

Cardiovascular Risk Assessment Program for Aboriginal & Torres Islander

Traits:

Australia's total cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk evaluation algorithm(Paigea et al., 2019) first

determines which people follow the requirements for a scientifically defined elevated risk of CVD and,

among those that do not fulfill such requirements, the Framingham Risk Equation applies to predict an

individual's risk of CVD over the next 5 years. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and non-

Indigenous Australians, the same risk calculation is used, but there is difference in inherent vulnerability

between the two groups, with the former facing a larger prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors.

5CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

Workforce availability:

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander-related findings contained total CVD risk evaluation

and/or diagnosis, main evidence identified and participants with no known CVDs. Studies were excluded

if they reported observations only for persons with current CVD or did not publish outcomes

independently for individuals without CVD, involved only pregnant women or children, registered the

development or examination of electronic decision support systems or published only CVD risk

evaluation studies. Additionally, defined research that helps in meeting the selection requirements

were reported prior to 2010.

Efficiency and effectiveness:

Generally, there is a dearth of scientific data to educate the Indigenous and Torres Strait Islanders

of Australian health recommendations for risk evaluation and treatment of CVD. There is confirmation

that CVD incidence begins rapidly in Indigenous and Torres Strait Islanders, and that the Framingham

Incidence Calculation alone underestimates the danger of CVD, at least in rural northern Australian

communities.

Identification of opportunities, priorities and options:

The lack of evidence in this report highlights the need to make suggestions for more empirical

study. New results from data collection efforts across ongoing trials, such as ongoing Cardiovascular

Disease Risk Assessment research of Aboriginal Australians, will be valuable for risk evaluation though

limits on sample size and generalizability exist (Paigea et al. 2019). The main determinant of overall

CVD exposure is the implicit age- and gender-specific danger to the population in question. Thus

descriptive evidence on age-specific and sex-specific frequency of CVD should be used to recalibrate risk

levels and estimate the target population incidence more accurately.

Workforce availability:

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander-related findings contained total CVD risk evaluation

and/or diagnosis, main evidence identified and participants with no known CVDs. Studies were excluded

if they reported observations only for persons with current CVD or did not publish outcomes

independently for individuals without CVD, involved only pregnant women or children, registered the

development or examination of electronic decision support systems or published only CVD risk

evaluation studies. Additionally, defined research that helps in meeting the selection requirements

were reported prior to 2010.

Efficiency and effectiveness:

Generally, there is a dearth of scientific data to educate the Indigenous and Torres Strait Islanders

of Australian health recommendations for risk evaluation and treatment of CVD. There is confirmation

that CVD incidence begins rapidly in Indigenous and Torres Strait Islanders, and that the Framingham

Incidence Calculation alone underestimates the danger of CVD, at least in rural northern Australian

communities.

Identification of opportunities, priorities and options:

The lack of evidence in this report highlights the need to make suggestions for more empirical

study. New results from data collection efforts across ongoing trials, such as ongoing Cardiovascular

Disease Risk Assessment research of Aboriginal Australians, will be valuable for risk evaluation though

limits on sample size and generalizability exist (Paigea et al. 2019). The main determinant of overall

CVD exposure is the implicit age- and gender-specific danger to the population in question. Thus

descriptive evidence on age-specific and sex-specific frequency of CVD should be used to recalibrate risk

levels and estimate the target population incidence more accurately.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

Recommendation of specific actions based on the analysis of the information:

The broader application of these results is restricted by the usage of the Framingham Risk

Method (Paigea et al., 2019) without corresponding categorization into high-risk categories using clinical

parameters, and concerns with generalizing the effects of this specific primary care community to other

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (Ski et al., 2015). An alternate, realistic and potentially more

generalizable solution is required to update the specific formula, including recalibrating the Framingham

Risk Equation and raising the risk level, using regional figures on Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander

CVD incident levels as associated hospital and mortality data are available.

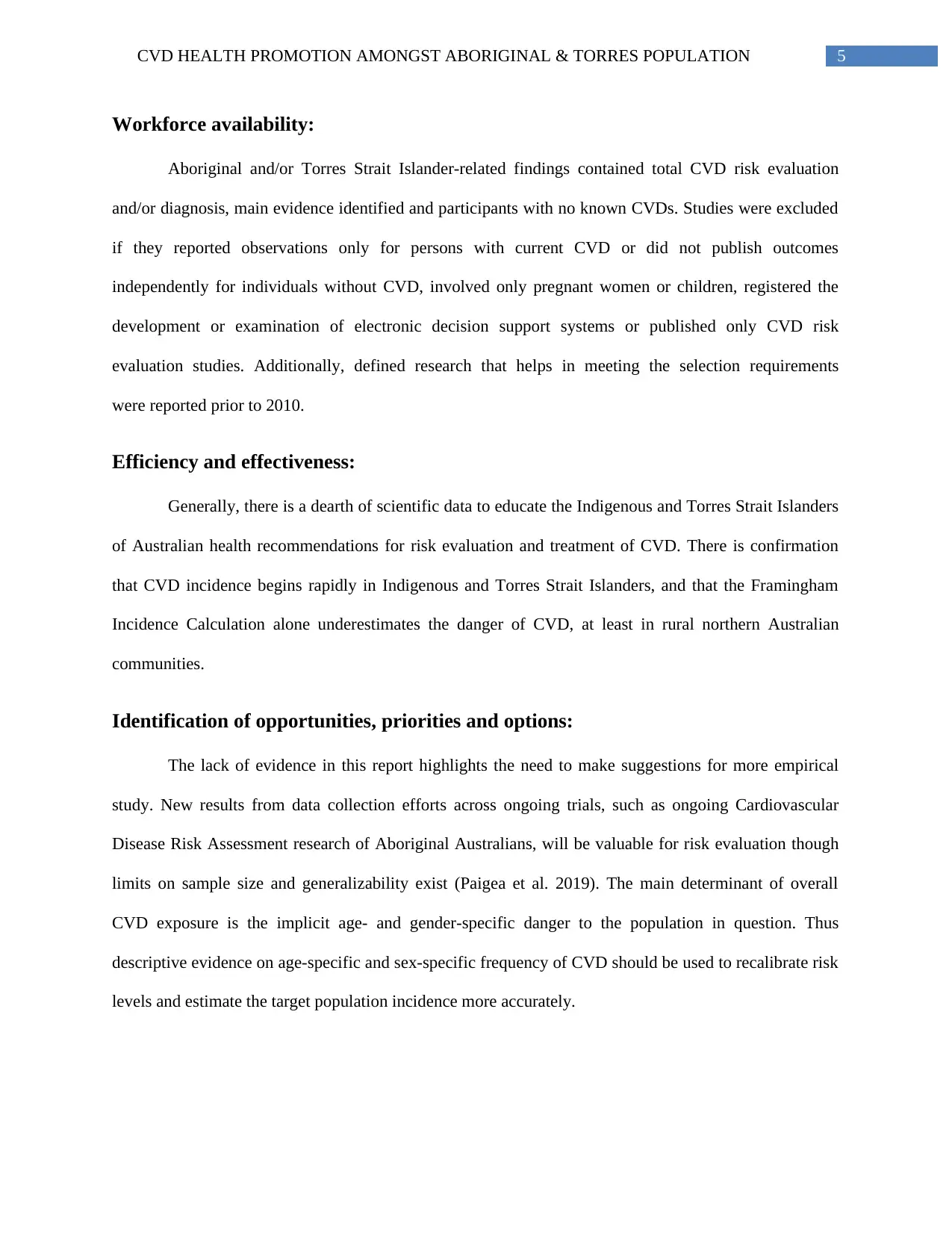

Stakeholder Analysis:

Stakeholder Description of

involvement issue

Interest in

the issue

Influence/power Position Impact of

issue on

stakeholder

National

institute of

alcohol

Coordinates

national activities in

alcohol research,

prevention and

treatment

High Low Supportive High

Action Heart rehabilitation

service that helps

people who have

suffered from a

heart attack,

undergone cardiac

surgery,

High High supportive high

Recommendation of specific actions based on the analysis of the information:

The broader application of these results is restricted by the usage of the Framingham Risk

Method (Paigea et al., 2019) without corresponding categorization into high-risk categories using clinical

parameters, and concerns with generalizing the effects of this specific primary care community to other

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (Ski et al., 2015). An alternate, realistic and potentially more

generalizable solution is required to update the specific formula, including recalibrating the Framingham

Risk Equation and raising the risk level, using regional figures on Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander

CVD incident levels as associated hospital and mortality data are available.

Stakeholder Analysis:

Stakeholder Description of

involvement issue

Interest in

the issue

Influence/power Position Impact of

issue on

stakeholder

National

institute of

alcohol

Coordinates

national activities in

alcohol research,

prevention and

treatment

High Low Supportive High

Action Heart rehabilitation

service that helps

people who have

suffered from a

heart attack,

undergone cardiac

surgery,

High High supportive high

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

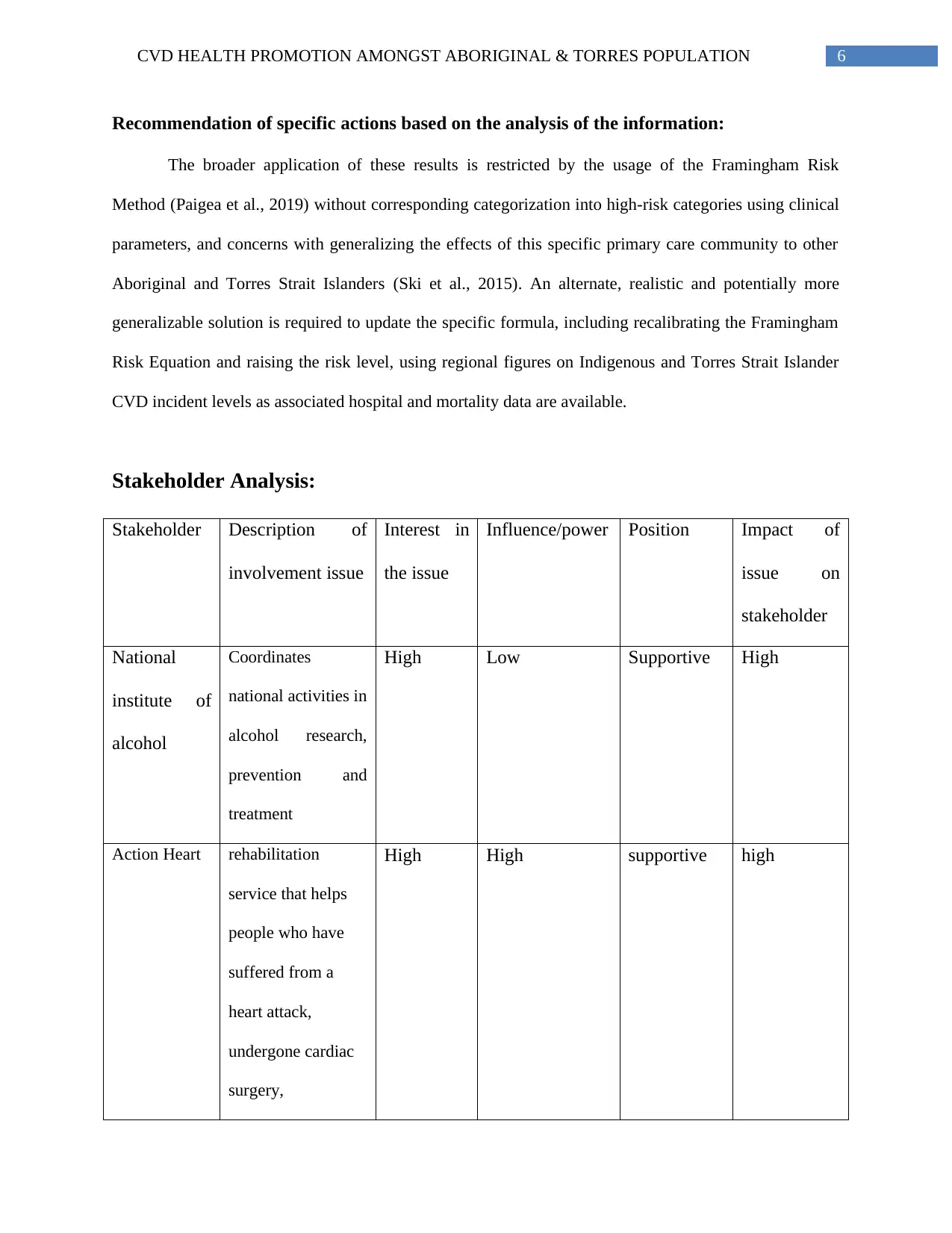

Diabetes

Management

and Education

Group

Regulates

routine treatment on

clinical, lifestyle

and psychosocial

outcomes in type-

2 diabetes patients.

high low supportive low

Conclusion:

There is a need to expand the number of physicians for aboriginal communities with chronic

cardiovascular disease and referral programs by Aboriginal community-controlled health agencies and

other metropolitan, rural and remote settings. To eliminate negative effects of chronic illness, the

Regional Aboriginal Health Equity Summit established goals for aboriginal communities to help

minimize the period spent of treatment and in-hospital management. To that the risk of chronic heart

disease within the targeted population, the need for funds to control the aforementioned programs has

become quite important. The promotional program mentioned above prove to be one of the crucial ways

with which better quality of life can be promoted amongst the Aboriginal & Torres Island Strait Islanders.

Diabetes

Management

and Education

Group

Regulates

routine treatment on

clinical, lifestyle

and psychosocial

outcomes in type-

2 diabetes patients.

high low supportive low

Conclusion:

There is a need to expand the number of physicians for aboriginal communities with chronic

cardiovascular disease and referral programs by Aboriginal community-controlled health agencies and

other metropolitan, rural and remote settings. To eliminate negative effects of chronic illness, the

Regional Aboriginal Health Equity Summit established goals for aboriginal communities to help

minimize the period spent of treatment and in-hospital management. To that the risk of chronic heart

disease within the targeted population, the need for funds to control the aforementioned programs has

become quite important. The promotional program mentioned above prove to be one of the crucial ways

with which better quality of life can be promoted amongst the Aboriginal & Torres Island Strait Islanders.

8CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

References:

Brown, A., & Kritharides, L. (2017). Overcoming cardiovascular disease in Indigenous

Australians. Medical Journal of Australia, 206(1), 10-12.

Gibson, O., Lisy, K., Davy, C., Aromataris, E., Kite, E., Lockwood, C., ... & Brown, A. (2015). Enablers

and barriers to the implementation of primary health care interventions for Indigenous people

with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Implementation Science, 10(1), 71.

Gubhaju, L., Banks, E., MacNiven, R., McNamara, B. J., Joshy, G., Bauman, A., & Eades, S. J. (2015).

Physical functional limitations among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal older adults: associations

with socio-demographic factors and health. PloS one, 10(9).

Gubhaju, L., Banks, E., Ward, J., D’Este, C., Ivers, R., Roseby, R., ... & Hotu, C. (2019). ‘Next

Generation Youth Well-being Study:’understanding the health and social well-being trajectories

of Australian Aboriginal adolescents aged 10–24 years: study protocol. BMJ open, 9(3), e028734.

Helms, A., Gilhotra, R., Preston, S., Saireddy, R., Starmer, G., & Sutcliffe, S. (2020). P188 Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Australians have significantly

Jones, R. The epidemiology of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, health and wellbeing.

(Jones)

Jones, R., Thurber, K. A., Wright, A., Chapman, J., Donohoe, P., Davis, V., & Lovett, R. (2018).

Associations between participation in a ranger program and health and wellbeing outcomes

among aboriginal and torres strait islander people in Central Australia: a proof of concept

study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(7), 1478.

Paigea, E., Jenkinsa, L. O. D., Agostinoa, J., Penningsc, S., Waded, V., Lovetta, R., ... & Banksa, E.

(2019). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander absolute cardiovascular risk assessment and

management: systematic review of evidence to inform national guidelines.

References:

Brown, A., & Kritharides, L. (2017). Overcoming cardiovascular disease in Indigenous

Australians. Medical Journal of Australia, 206(1), 10-12.

Gibson, O., Lisy, K., Davy, C., Aromataris, E., Kite, E., Lockwood, C., ... & Brown, A. (2015). Enablers

and barriers to the implementation of primary health care interventions for Indigenous people

with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Implementation Science, 10(1), 71.

Gubhaju, L., Banks, E., MacNiven, R., McNamara, B. J., Joshy, G., Bauman, A., & Eades, S. J. (2015).

Physical functional limitations among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal older adults: associations

with socio-demographic factors and health. PloS one, 10(9).

Gubhaju, L., Banks, E., Ward, J., D’Este, C., Ivers, R., Roseby, R., ... & Hotu, C. (2019). ‘Next

Generation Youth Well-being Study:’understanding the health and social well-being trajectories

of Australian Aboriginal adolescents aged 10–24 years: study protocol. BMJ open, 9(3), e028734.

Helms, A., Gilhotra, R., Preston, S., Saireddy, R., Starmer, G., & Sutcliffe, S. (2020). P188 Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Australians have significantly

Jones, R. The epidemiology of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, health and wellbeing.

(Jones)

Jones, R., Thurber, K. A., Wright, A., Chapman, J., Donohoe, P., Davis, V., & Lovett, R. (2018).

Associations between participation in a ranger program and health and wellbeing outcomes

among aboriginal and torres strait islander people in Central Australia: a proof of concept

study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(7), 1478.

Paigea, E., Jenkinsa, L. O. D., Agostinoa, J., Penningsc, S., Waded, V., Lovetta, R., ... & Banksa, E.

(2019). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander absolute cardiovascular risk assessment and

management: systematic review of evidence to inform national guidelines.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9CVD HEALTH PROMOTION AMONGST ABORIGINAL & TORRES POPULATION

Rice, K., Te Hiwi, B., Zwarenstein, M., Lavallee, B., Barre, D. E., & Harris, S. B. (2016). Best practices

for the prevention and Management of Diabetes and Obesity-Related Chronic Disease among

indigenous peoples in Canada: a review. Canadian journal of diabetes, 40(3), 216-225.

Sahle, B. W., Owen, A. J., Mutowo, M. P., Krum, H., & Reid, C. M. (2016). Prevalence of heart failure in

Australia: a systematic review. BMC cardiovascular disorders, 16(1), 32.

Ski, C. F., Vale, M. J., Bennett, G. R., Chalmers, V. L., McFarlane, K., Jelinek, V. M., ... & Thompson,

D. R. (2015). Improving access and equity in reducing cardiovascular risk: the Queensland

Health model. Medical Journal of Australia, 202(3), 148-152.

Woodruffe, S., Neubeck, L., Clark, R. A., Gray, K., Ferry, C., Finan, J., ... & Briffa, T. G. (2015).

Australian Cardiovascular Health and Rehabilitation Association (ACRA) core components of

cardiovascular disease secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation 2014. Heart, Lung and

Circulation, 24(5), 430-441.

Woodruffe, S., Neubeck, L., Clark, R. A., Gray, K., Ferry, C., Finan, J., ... & Briffa, T. G. (2015).

Australian Cardiovascular Health and Rehabilitation Association (ACRA) core components of

cardiovascular disease secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation 2014. Heart, Lung and

Circulation, 24(5), 430-441.

Rice, K., Te Hiwi, B., Zwarenstein, M., Lavallee, B., Barre, D. E., & Harris, S. B. (2016). Best practices

for the prevention and Management of Diabetes and Obesity-Related Chronic Disease among

indigenous peoples in Canada: a review. Canadian journal of diabetes, 40(3), 216-225.

Sahle, B. W., Owen, A. J., Mutowo, M. P., Krum, H., & Reid, C. M. (2016). Prevalence of heart failure in

Australia: a systematic review. BMC cardiovascular disorders, 16(1), 32.

Ski, C. F., Vale, M. J., Bennett, G. R., Chalmers, V. L., McFarlane, K., Jelinek, V. M., ... & Thompson,

D. R. (2015). Improving access and equity in reducing cardiovascular risk: the Queensland

Health model. Medical Journal of Australia, 202(3), 148-152.

Woodruffe, S., Neubeck, L., Clark, R. A., Gray, K., Ferry, C., Finan, J., ... & Briffa, T. G. (2015).

Australian Cardiovascular Health and Rehabilitation Association (ACRA) core components of

cardiovascular disease secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation 2014. Heart, Lung and

Circulation, 24(5), 430-441.

Woodruffe, S., Neubeck, L., Clark, R. A., Gray, K., Ferry, C., Finan, J., ... & Briffa, T. G. (2015).

Australian Cardiovascular Health and Rehabilitation Association (ACRA) core components of

cardiovascular disease secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation 2014. Heart, Lung and

Circulation, 24(5), 430-441.

1 out of 10

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.