Evidence Base for Natural Capital Risks in Australian Wheat Farms

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/13

|24

|9981

|360

Report

AI Summary

This report delves into the critical connection between natural capital and financial risk in the context of Australian wheat farming. It highlights the agricultural sector's significant dependence on natural capital, such as soil health and water resources, and how lenders are exposed to related risks through loans to farmers. The study emphasizes the limitations of traditional credit risk assessment methods, which primarily rely on historical financial data and often overlook environmental factors. It provides an evidence base to support natural capital risk assessment for Australian wheat farming, acknowledging the complexity and interconnectedness of natural capital processes, particularly concerning soil health. The research outlines a methodology for identifying key environmental risks and dependencies, and it offers insights into how these risks can be assessed, mitigated, and monitored by financial institutions. The study contributes to the broader discussion on sustainable lending and the integration of environmental considerations into financial decision-making, especially within the Australian agricultural sector. The report also reviews the relevant literature on environmental credit risk assessment, noting the scarcity of research in the context of smaller-scale loans and specific agricultural sub-sectors.

Developing an evidence base for assessing natural

capital risks and dependencies in lending to Australian

wheat farms

Abstract:

Farmers are highly dependent on stocks of natural capital, and lenders are in turn exposed to

natural capital through their loans to farmers. However, the traditional process for assessing a

farmer’s credit risk relies primarily on historical financial data. Banks’ consideration of

environmental factors tends to be limited to major risks such as contaminated land liabilities,

and to large project and corporate finance, as opposed to the smaller loans typical of the

Australian agricultural sector. The relevant risks and dependencies for agriculture vary by sub-

sector and geography, and there is a lack of standardized methodologies and evidence to

support risk assessment. We provide an evidence base to support natural capital risk

assessment for a single sub-sector of Australian agriculture – wheat farming. We show that

such an assessment is possible, with a combination of quantitative and qualitative inputs, but

the complexity and interconnectedness of natural capital processes is a challenge, particularly

for soil health.

Key Words:

Natural capital; environmental risk; environmental credit risk assessment; responsible lending;

wheat farming; Australia

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the Australian Commonwealth Department of Infrastructure and

Rural Development under the Sense-T “Sensing Natural Capital” project. We thank the project’s

industry partners, National Australia Bank (NAB) and the Climate Disclosure Standards Board

(CDSB) for their support.

capital risks and dependencies in lending to Australian

wheat farms

Abstract:

Farmers are highly dependent on stocks of natural capital, and lenders are in turn exposed to

natural capital through their loans to farmers. However, the traditional process for assessing a

farmer’s credit risk relies primarily on historical financial data. Banks’ consideration of

environmental factors tends to be limited to major risks such as contaminated land liabilities,

and to large project and corporate finance, as opposed to the smaller loans typical of the

Australian agricultural sector. The relevant risks and dependencies for agriculture vary by sub-

sector and geography, and there is a lack of standardized methodologies and evidence to

support risk assessment. We provide an evidence base to support natural capital risk

assessment for a single sub-sector of Australian agriculture – wheat farming. We show that

such an assessment is possible, with a combination of quantitative and qualitative inputs, but

the complexity and interconnectedness of natural capital processes is a challenge, particularly

for soil health.

Key Words:

Natural capital; environmental risk; environmental credit risk assessment; responsible lending;

wheat farming; Australia

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the Australian Commonwealth Department of Infrastructure and

Rural Development under the Sense-T “Sensing Natural Capital” project. We thank the project’s

industry partners, National Australia Bank (NAB) and the Climate Disclosure Standards Board

(CDSB) for their support.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

1 Introduction

Agriculture is a small but important part of the Australian economy, accounting for 7% (by

value) of total exports in 2014-15 (ABS 2016a), and contributing as much as 12% of Australia’s

GDP, when including the value of associated pre- and post-farm production activities (NFF

2012). Farmers own or manage 61% of Australia’s land (NFF 2012) and therefore play a key role

in managing Australia’s stocks of natural capital, or “those elements of nature which either

directly provide benefits or underpin human wellbeing” (Natural Capital Committee 2013, 11).

Farmers all over the world are highly dependent on environmental factors such as rainfall,

temperature and climate, as well as natural capital stocks such as energy, mineral and water

resources, productive soils and ecosystems. Australia’s aridity (70% of mainland Australia

receives less than 500mm of rain per year – Geoscience Australia 2016) and generally poor soils

means that Australian agriculture is particularly vulnerable to variability and extreme

conditions. For example, widespread drought in 2002-03 led to a 41% reduction in agricultural

income, reducing Australia’s GDP by around 1% in that year (Lu and Hedley 2004).

99% of the 134,000 farm businesses operating in Australia in 2012 were family owned (NFF

2012), with on average 85% of business equity being held by the operator and close relatives or

business partners (ABARES 2016). The remaining 15% takes the form of debt, including short-

term unsecured debt such as credit cards; equipment supplier finance; and formal secured

loans, usually from one of the small number of Australian banks with extensive rural networks.

Through these loans, which are typically used either to fund land or machinery purchases, or to

provide working capital to bridge temporary income-cost mismatches, these banks are exposed

to a range of natural capital and environmental risks and dependencies. The traditional process

for assessing a farmer’s credit risk, however, relies primary on historical financial data, which

only indirectly and incompletely reflects these risks and dependencies.

In 2012, around 40 international financial institutions signed the Natural Capital Declaration

(NCD), committing to integrate natural capital considerations into their financial products, and

their accounting and reporting frameworks, by 2020. 1 A pilot study (Cojoianu et al. 2015) found

that 42% of financial institutions claim to be already integrating natural capital risks in credit

risk assessments. However, the evidence to date suggests that this is limited to large (over

US$10 million) project finance deals and even larger corporate loans, and is virtually non-

existent for smaller secured loans typical of the Australian agricultural sector. A key challenge

for agriculture is the fact that the relevant risks and dependencies vary by sub-sector and in

some cases by individual crop or animal production system, as well as by geography. Other

difficulties include lack of awareness around natural capital issues, the vagueness of regulatory

1 http://www.naturalcapitalfinancealliance.org/about-the-natural-capital-declaration/ (accessed 26 October 2016).

1 Introduction

Agriculture is a small but important part of the Australian economy, accounting for 7% (by

value) of total exports in 2014-15 (ABS 2016a), and contributing as much as 12% of Australia’s

GDP, when including the value of associated pre- and post-farm production activities (NFF

2012). Farmers own or manage 61% of Australia’s land (NFF 2012) and therefore play a key role

in managing Australia’s stocks of natural capital, or “those elements of nature which either

directly provide benefits or underpin human wellbeing” (Natural Capital Committee 2013, 11).

Farmers all over the world are highly dependent on environmental factors such as rainfall,

temperature and climate, as well as natural capital stocks such as energy, mineral and water

resources, productive soils and ecosystems. Australia’s aridity (70% of mainland Australia

receives less than 500mm of rain per year – Geoscience Australia 2016) and generally poor soils

means that Australian agriculture is particularly vulnerable to variability and extreme

conditions. For example, widespread drought in 2002-03 led to a 41% reduction in agricultural

income, reducing Australia’s GDP by around 1% in that year (Lu and Hedley 2004).

99% of the 134,000 farm businesses operating in Australia in 2012 were family owned (NFF

2012), with on average 85% of business equity being held by the operator and close relatives or

business partners (ABARES 2016). The remaining 15% takes the form of debt, including short-

term unsecured debt such as credit cards; equipment supplier finance; and formal secured

loans, usually from one of the small number of Australian banks with extensive rural networks.

Through these loans, which are typically used either to fund land or machinery purchases, or to

provide working capital to bridge temporary income-cost mismatches, these banks are exposed

to a range of natural capital and environmental risks and dependencies. The traditional process

for assessing a farmer’s credit risk, however, relies primary on historical financial data, which

only indirectly and incompletely reflects these risks and dependencies.

In 2012, around 40 international financial institutions signed the Natural Capital Declaration

(NCD), committing to integrate natural capital considerations into their financial products, and

their accounting and reporting frameworks, by 2020. 1 A pilot study (Cojoianu et al. 2015) found

that 42% of financial institutions claim to be already integrating natural capital risks in credit

risk assessments. However, the evidence to date suggests that this is limited to large (over

US$10 million) project finance deals and even larger corporate loans, and is virtually non-

existent for smaller secured loans typical of the Australian agricultural sector. A key challenge

for agriculture is the fact that the relevant risks and dependencies vary by sub-sector and in

some cases by individual crop or animal production system, as well as by geography. Other

difficulties include lack of awareness around natural capital issues, the vagueness of regulatory

1 http://www.naturalcapitalfinancealliance.org/about-the-natural-capital-declaration/ (accessed 26 October 2016).

3

requirements around natural capital issues, the challenge of relating long-term issues to short-

term materiality, and most importantly, lack of standardized industry- and geography-specific

methodologies and robust information for the quantification of natural capital risks (Cojoianu

et al. 2015). Our paper therefore aims to help address these challenges by developing an

evidence base to support natural capital credit risk assessment for a single sub-sector of

Australian agriculture – wheat farming, which contributed over A$7 billion or 13% of Australia’s

total value of agricultural production in 2015, second only to cattle grazing (ABS 2016b).

The paper is structured as follows. In section 2, we review the literature on environmental

credit risk assessment. Section 3 outlines our methodology for identifying key environmental

and natural capital risks and dependencies, and section 4 sets out our findings for the

Australian wheat sector, explaining why each risk is material, how it can be mitigated, and how

a bank could assess and monitor the risk. Finally, section 5 discusses the overall findings that

emerged from this analysis.

2 Environmental credit risk assessment

The literature on sustainability in the banking sector can be divided into two broad groups

(Zeidan et al., 2015): one dealing with external practices (which include banks’ communications

with shareholders and stakeholders around sustainability issues) and the other with internal

practices (which include how sustainability issues are incorporated into risk management

models and lending or investment decisions). Our paper contributes to the latter.

Within this strand of the literature there are two main areas of focus. The first considers how

environmental performance influences the perceived credit risk and cost of debt of companies,

with most studies finding that firms with better sustainability performance ratings experience a

lower cost of debt, and vice versa (Bauer & Hann 2010; Nandy & Lodh 2012). Most studies focus

on public companies in developed countries (although Weber, Hoque, and Ayub Islam (2015)

provide evidence linking sustainability criteria to loan default probability in a developing

country, while noting that sustainability criteria are not yet being used by lenders there), and

on major risks such as hazardous chemicals, substantial emissions and climate change

(Schneider 2011; Chava 2014). Most papers also focus on large-scale corporate loans and bond

finance, rather than smaller loans to privately held companies and SMEs, where data on

sustainability as well as financial issues is much scarcer and opaque (Berger and Udell 1998).

There is, to the best of our knowledge, no peer-reviewed research demonstrating a clear link

between environmental performance at this smaller scale, and the availability, terms or cost of

bank loans. Nevertheless, from our discussions with Australian banking officials it appears that

at least some banks are operating on the assumption that there is such a link:

requirements around natural capital issues, the challenge of relating long-term issues to short-

term materiality, and most importantly, lack of standardized industry- and geography-specific

methodologies and robust information for the quantification of natural capital risks (Cojoianu

et al. 2015). Our paper therefore aims to help address these challenges by developing an

evidence base to support natural capital credit risk assessment for a single sub-sector of

Australian agriculture – wheat farming, which contributed over A$7 billion or 13% of Australia’s

total value of agricultural production in 2015, second only to cattle grazing (ABS 2016b).

The paper is structured as follows. In section 2, we review the literature on environmental

credit risk assessment. Section 3 outlines our methodology for identifying key environmental

and natural capital risks and dependencies, and section 4 sets out our findings for the

Australian wheat sector, explaining why each risk is material, how it can be mitigated, and how

a bank could assess and monitor the risk. Finally, section 5 discusses the overall findings that

emerged from this analysis.

2 Environmental credit risk assessment

The literature on sustainability in the banking sector can be divided into two broad groups

(Zeidan et al., 2015): one dealing with external practices (which include banks’ communications

with shareholders and stakeholders around sustainability issues) and the other with internal

practices (which include how sustainability issues are incorporated into risk management

models and lending or investment decisions). Our paper contributes to the latter.

Within this strand of the literature there are two main areas of focus. The first considers how

environmental performance influences the perceived credit risk and cost of debt of companies,

with most studies finding that firms with better sustainability performance ratings experience a

lower cost of debt, and vice versa (Bauer & Hann 2010; Nandy & Lodh 2012). Most studies focus

on public companies in developed countries (although Weber, Hoque, and Ayub Islam (2015)

provide evidence linking sustainability criteria to loan default probability in a developing

country, while noting that sustainability criteria are not yet being used by lenders there), and

on major risks such as hazardous chemicals, substantial emissions and climate change

(Schneider 2011; Chava 2014). Most papers also focus on large-scale corporate loans and bond

finance, rather than smaller loans to privately held companies and SMEs, where data on

sustainability as well as financial issues is much scarcer and opaque (Berger and Udell 1998).

There is, to the best of our knowledge, no peer-reviewed research demonstrating a clear link

between environmental performance at this smaller scale, and the availability, terms or cost of

bank loans. Nevertheless, from our discussions with Australian banking officials it appears that

at least some banks are operating on the assumption that there is such a link:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

“I guess, you know, there’s an assumption that we’ve made, that seems to be validated

by numerous case studies, that our more productive agribusiness customers are those

who manage their environmental resources better, and they seem to be one and the

same thing.” (Environmental finance professional, August 6, 2015).

The second area concerns the extent to which banks incorporate sustainability criteria in their

lending decision-making. It is generally agreed that banks have been incorporating some

environmental risks into their credit assessment processes, since the early 1990s (Weber,

Fenchel, & Scholz 2008). This was originally driven by legislation, such as the Comprehensive

Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act 1980 in the United States, which

imposed remediation liabilities on the owners of contaminated sites. As a result, early

environmental credit risk assessments tended to focus only on such specific liabilities, rather

than providing a comprehensive framework for the assessment of all potentially material

environmental (and social) risks, dependencies and opportunities. In the mid-2000s, Weber,

Fenchel, & Scholz (2008) identified only four classes of environmental risk being considered by

banks: contamination liabilities; impacts of mandatory environmental regulations; changes in

buyer/consumer attitudes; and reputational risk due to being associated with projects seen as

environmentally or socially damaging by stakeholders. Furthermore, they found that most

attention was given to environmental issues in the rating (or risk identification) phase of the

credit management process, least in the costing (or risk evaluation) phase and an intermediate

level in the monitoring (or risk controlling) phases.

A recent survey of 36 financial institutions and 26 financial research providers undertaken for

the NCD (Cojoianu et al. 2015) found that although 42% of respondents claim to consider

natural capital risks in their credit risk assessment, there is no evidence that this is done

systematically. Lenders cited numerous difficulties in assessing natural capital risks including

the lack of suitable contextual methodologies, data, budgets and capacity. Currently, only

project finance transactions and related services can be benchmarked to an international

standard of environmental and social due diligence: the Equator Principles, which are applied

only to projects over US$10 million, or US$100 million for corporate loans.

The aforementioned body of research on sustainability performance and perceived credit risk

of borrowers goes some way toward explaining why banks might seek to incorporate

environmental risks and dependencies in their credit assessment processes. As Weber, Hoque,

and Ayub Islam (2015, 3) observe, “The rationale for using sustainability indicators for

predicting credit risks is based on the idea that good sustainability performance mitigates risks

arising through environmental and social impacts as well as through and stakeholder pressure

and regulation.” However, while high-level sustainability indicators may be available for larger

companies, usually based on research providers’ analysis of annual and sustainability reports,

“I guess, you know, there’s an assumption that we’ve made, that seems to be validated

by numerous case studies, that our more productive agribusiness customers are those

who manage their environmental resources better, and they seem to be one and the

same thing.” (Environmental finance professional, August 6, 2015).

The second area concerns the extent to which banks incorporate sustainability criteria in their

lending decision-making. It is generally agreed that banks have been incorporating some

environmental risks into their credit assessment processes, since the early 1990s (Weber,

Fenchel, & Scholz 2008). This was originally driven by legislation, such as the Comprehensive

Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act 1980 in the United States, which

imposed remediation liabilities on the owners of contaminated sites. As a result, early

environmental credit risk assessments tended to focus only on such specific liabilities, rather

than providing a comprehensive framework for the assessment of all potentially material

environmental (and social) risks, dependencies and opportunities. In the mid-2000s, Weber,

Fenchel, & Scholz (2008) identified only four classes of environmental risk being considered by

banks: contamination liabilities; impacts of mandatory environmental regulations; changes in

buyer/consumer attitudes; and reputational risk due to being associated with projects seen as

environmentally or socially damaging by stakeholders. Furthermore, they found that most

attention was given to environmental issues in the rating (or risk identification) phase of the

credit management process, least in the costing (or risk evaluation) phase and an intermediate

level in the monitoring (or risk controlling) phases.

A recent survey of 36 financial institutions and 26 financial research providers undertaken for

the NCD (Cojoianu et al. 2015) found that although 42% of respondents claim to consider

natural capital risks in their credit risk assessment, there is no evidence that this is done

systematically. Lenders cited numerous difficulties in assessing natural capital risks including

the lack of suitable contextual methodologies, data, budgets and capacity. Currently, only

project finance transactions and related services can be benchmarked to an international

standard of environmental and social due diligence: the Equator Principles, which are applied

only to projects over US$10 million, or US$100 million for corporate loans.

The aforementioned body of research on sustainability performance and perceived credit risk

of borrowers goes some way toward explaining why banks might seek to incorporate

environmental risks and dependencies in their credit assessment processes. As Weber, Hoque,

and Ayub Islam (2015, 3) observe, “The rationale for using sustainability indicators for

predicting credit risks is based on the idea that good sustainability performance mitigates risks

arising through environmental and social impacts as well as through and stakeholder pressure

and regulation.” However, while high-level sustainability indicators may be available for larger

companies, usually based on research providers’ analysis of annual and sustainability reports,

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

they are typically not applicable to smaller-scale loans such as those typical in the Australian

agricultural sector.

Very little research has been published on the incorporation of environmental risks and

dependencies into credit assessment for smaller-scale loans in any sector, or for any scale of

loans in agriculture in particular. A search across all academic databases subscribed to by the

University of Oxford using the keywords ‘environmental’, ‘credit’, ‘risk’ and ‘agriculture’ yielded

only 80 results, only a few of which were found to be relevant. For example, Georgopoulou et

al. (2015) develop a framework to assess the risk of climate change to lending across several

Greek industries, including wheat farming, using the loan portfolio of a Greek bank as a case

study. The authors use climate and agronomic modelling to make the case for materiality of

climate change to the agriculture sector, and conclude that the physical risks from climate

change to Greek crop farms are between 7.4-12.4% of their annual turnover. However, they do

not provide an evidence base for the assessment of more granular risk factors (e.g. rainfall

availability), but rather rely on a generic crop yield simulation model. The emphasis is on

calculation of portfolio-level exposure to systemic risks, as opposed to individual loan

assessment. Similarly, Do et al. (2016) find evidence that banks are considering drought risk at a

systemic level, increasing loan interest rates to large agricultural enterprises by up to 6 basis

points for every step increase in regional drought level in the 12 months prior to loan

origination. Zeidan et al. (2015) propose a sustainability credit score system for the sugar

industry in Brazil, based on six dimensions: economic growth, environmental protection, social

progress, socio-economic development, eco-efficiency and socio-environmental development.

Whilst taking a higher-level sustainability focus, this study is the most complementary to our

own in terms providing a basis for the evaluation of such risks for a specific sector and country.

In summary, there is an almost complete absence in the literature of detailed assessments of

how environmental and natural capital risks can be identified and included in the credit risk

assessment process for smaller-scale (e.g. US$0.5-2 million) bank loans. This is true across

industries, and for agriculture in particular. Our paper complements the top-down approach

taken by Zeidan et al. (2015) by developing a bottom-up, robust evidence base on why and how

different natural capital risks and dependencies are likely to affect the financial performance of

wheat farms in Australia, how these risks can be managed, and how the resultant managed risk

can be assessed by a lender.

3 Methodology

We followed a multi-stage approach to identifying, prioritizing and researching the natural

capital risks and dependencies applicable to Australian wheat farm lending, from a lender’s

perspective. First, we searched the publicly available environmental risk methodologies of 66

financial research providers and consultants identified by Cojoianu et al. (2015) for

they are typically not applicable to smaller-scale loans such as those typical in the Australian

agricultural sector.

Very little research has been published on the incorporation of environmental risks and

dependencies into credit assessment for smaller-scale loans in any sector, or for any scale of

loans in agriculture in particular. A search across all academic databases subscribed to by the

University of Oxford using the keywords ‘environmental’, ‘credit’, ‘risk’ and ‘agriculture’ yielded

only 80 results, only a few of which were found to be relevant. For example, Georgopoulou et

al. (2015) develop a framework to assess the risk of climate change to lending across several

Greek industries, including wheat farming, using the loan portfolio of a Greek bank as a case

study. The authors use climate and agronomic modelling to make the case for materiality of

climate change to the agriculture sector, and conclude that the physical risks from climate

change to Greek crop farms are between 7.4-12.4% of their annual turnover. However, they do

not provide an evidence base for the assessment of more granular risk factors (e.g. rainfall

availability), but rather rely on a generic crop yield simulation model. The emphasis is on

calculation of portfolio-level exposure to systemic risks, as opposed to individual loan

assessment. Similarly, Do et al. (2016) find evidence that banks are considering drought risk at a

systemic level, increasing loan interest rates to large agricultural enterprises by up to 6 basis

points for every step increase in regional drought level in the 12 months prior to loan

origination. Zeidan et al. (2015) propose a sustainability credit score system for the sugar

industry in Brazil, based on six dimensions: economic growth, environmental protection, social

progress, socio-economic development, eco-efficiency and socio-environmental development.

Whilst taking a higher-level sustainability focus, this study is the most complementary to our

own in terms providing a basis for the evaluation of such risks for a specific sector and country.

In summary, there is an almost complete absence in the literature of detailed assessments of

how environmental and natural capital risks can be identified and included in the credit risk

assessment process for smaller-scale (e.g. US$0.5-2 million) bank loans. This is true across

industries, and for agriculture in particular. Our paper complements the top-down approach

taken by Zeidan et al. (2015) by developing a bottom-up, robust evidence base on why and how

different natural capital risks and dependencies are likely to affect the financial performance of

wheat farms in Australia, how these risks can be managed, and how the resultant managed risk

can be assessed by a lender.

3 Methodology

We followed a multi-stage approach to identifying, prioritizing and researching the natural

capital risks and dependencies applicable to Australian wheat farm lending, from a lender’s

perspective. First, we searched the publicly available environmental risk methodologies of 66

financial research providers and consultants identified by Cojoianu et al. (2015) for

6

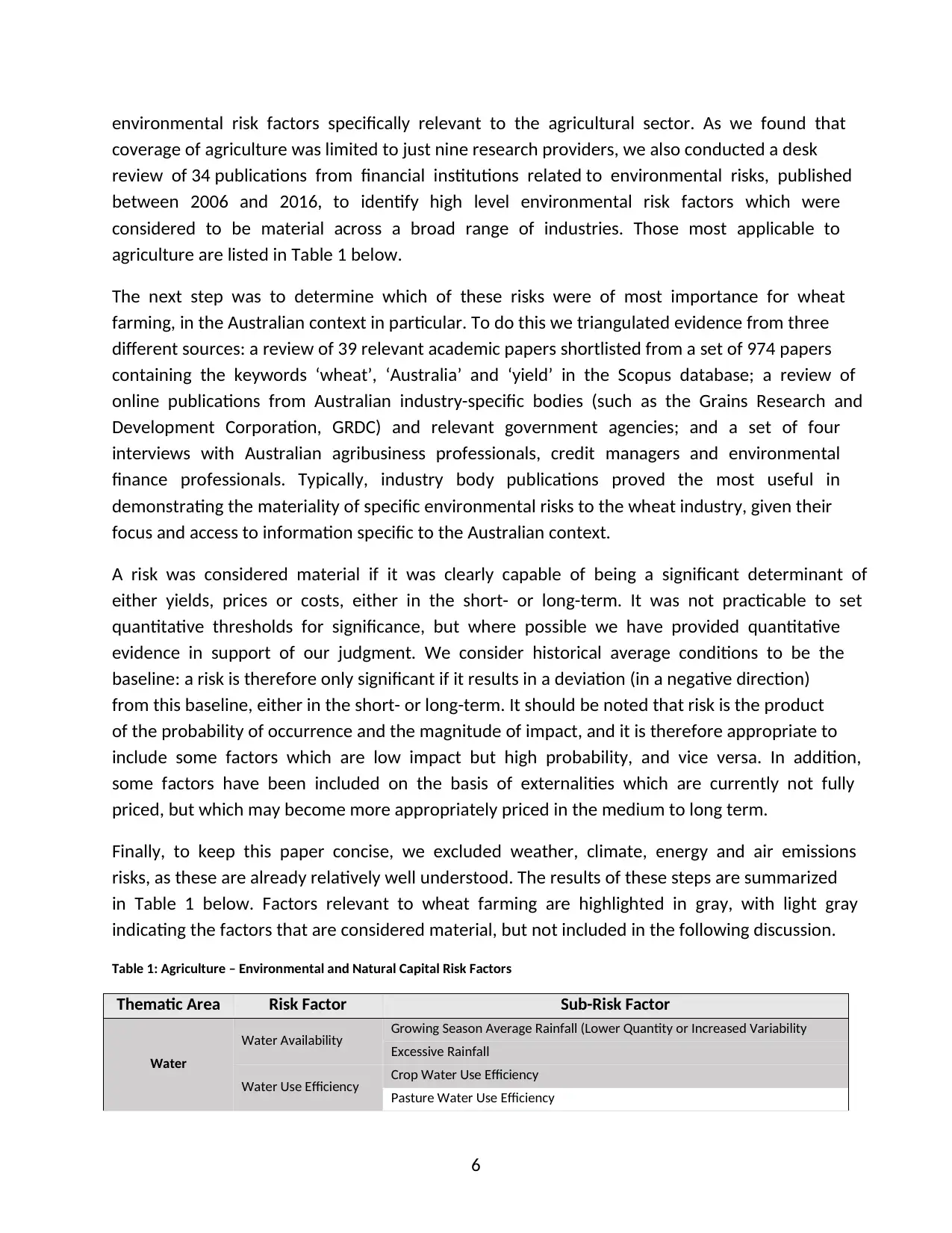

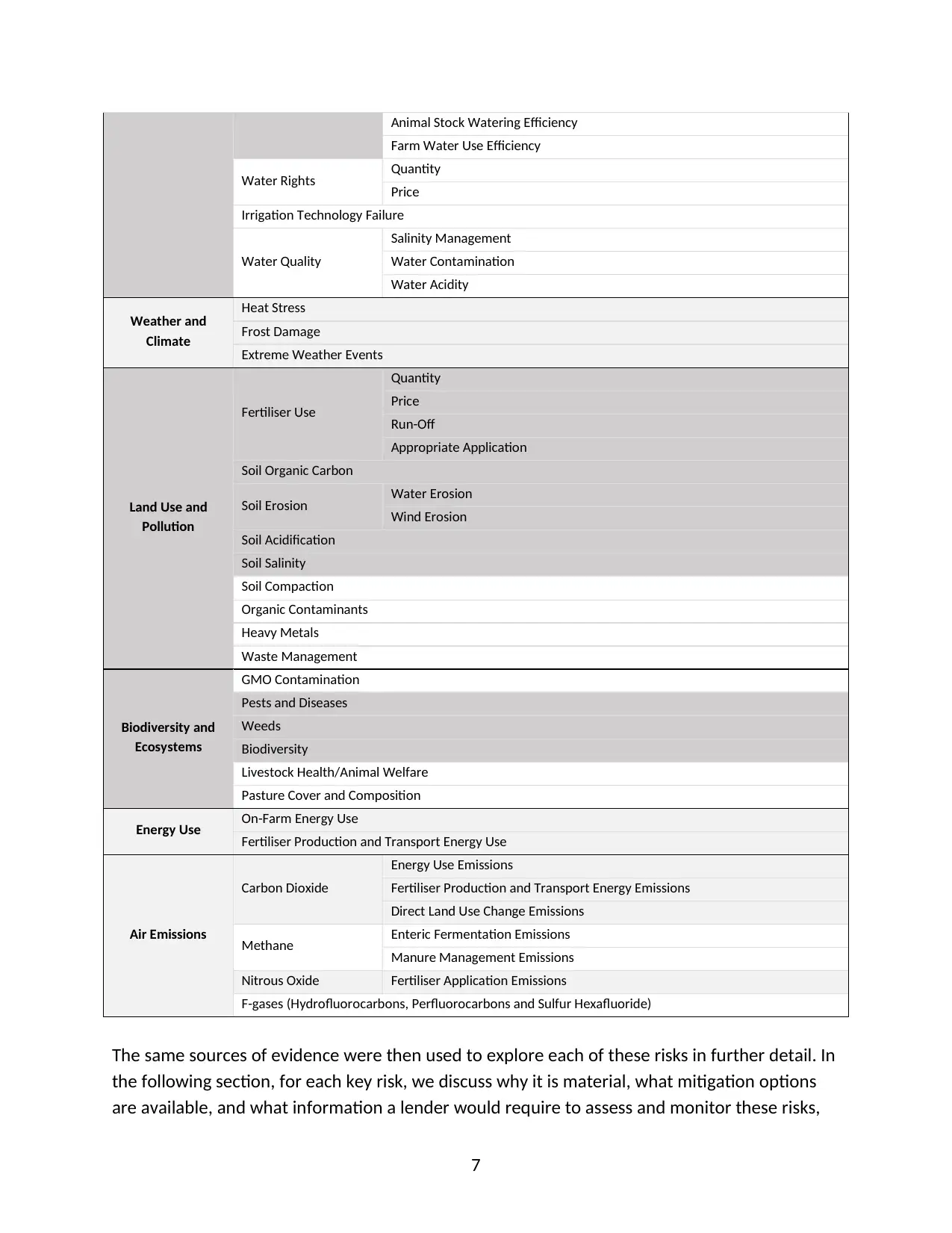

environmental risk factors specifically relevant to the agricultural sector. As we found that

coverage of agriculture was limited to just nine research providers, we also conducted a desk

review of 34 publications from financial institutions related to environmental risks, published

between 2006 and 2016, to identify high level environmental risk factors which were

considered to be material across a broad range of industries. Those most applicable to

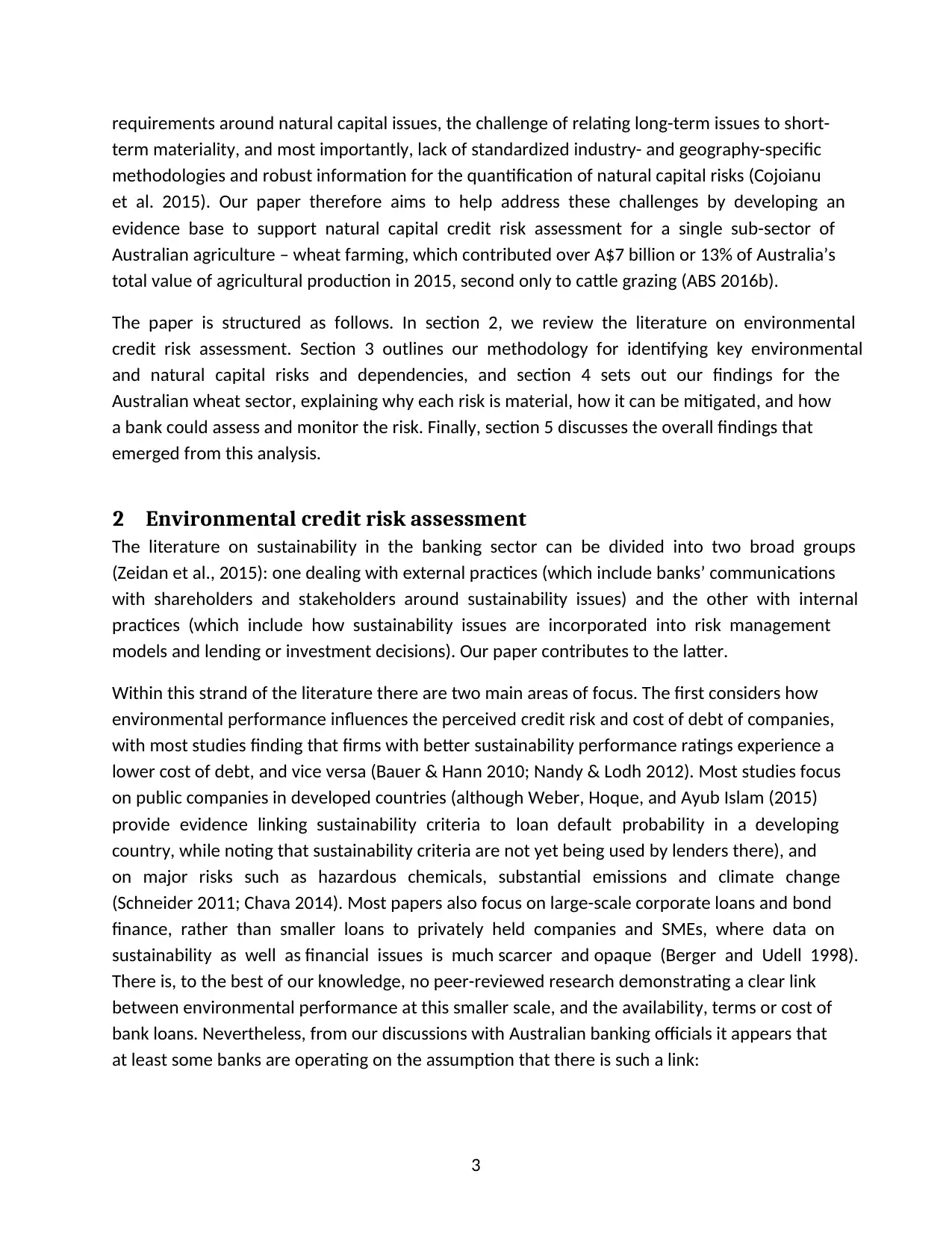

agriculture are listed in Table 1 below.

The next step was to determine which of these risks were of most importance for wheat

farming, in the Australian context in particular. To do this we triangulated evidence from three

different sources: a review of 39 relevant academic papers shortlisted from a set of 974 papers

containing the keywords ‘wheat’, ‘Australia’ and ‘yield’ in the Scopus database; a review of

online publications from Australian industry-specific bodies (such as the Grains Research and

Development Corporation, GRDC) and relevant government agencies; and a set of four

interviews with Australian agribusiness professionals, credit managers and environmental

finance professionals. Typically, industry body publications proved the most useful in

demonstrating the materiality of specific environmental risks to the wheat industry, given their

focus and access to information specific to the Australian context.

A risk was considered material if it was clearly capable of being a significant determinant of

either yields, prices or costs, either in the short- or long-term. It was not practicable to set

quantitative thresholds for significance, but where possible we have provided quantitative

evidence in support of our judgment. We consider historical average conditions to be the

baseline: a risk is therefore only significant if it results in a deviation (in a negative direction)

from this baseline, either in the short- or long-term. It should be noted that risk is the product

of the probability of occurrence and the magnitude of impact, and it is therefore appropriate to

include some factors which are low impact but high probability, and vice versa. In addition,

some factors have been included on the basis of externalities which are currently not fully

priced, but which may become more appropriately priced in the medium to long term.

Finally, to keep this paper concise, we excluded weather, climate, energy and air emissions

risks, as these are already relatively well understood. The results of these steps are summarized

in Table 1 below. Factors relevant to wheat farming are highlighted in gray, with light gray

indicating the factors that are considered material, but not included in the following discussion.

Table 1: Agriculture – Environmental and Natural Capital Risk Factors

Thematic Area Risk Factor Sub-Risk Factor

Water

Water Availability Growing Season Average Rainfall (Lower Quantity or Increased Variability

Excessive Rainfall

Water Use Efficiency Crop Water Use Efficiency

Pasture Water Use Efficiency

environmental risk factors specifically relevant to the agricultural sector. As we found that

coverage of agriculture was limited to just nine research providers, we also conducted a desk

review of 34 publications from financial institutions related to environmental risks, published

between 2006 and 2016, to identify high level environmental risk factors which were

considered to be material across a broad range of industries. Those most applicable to

agriculture are listed in Table 1 below.

The next step was to determine which of these risks were of most importance for wheat

farming, in the Australian context in particular. To do this we triangulated evidence from three

different sources: a review of 39 relevant academic papers shortlisted from a set of 974 papers

containing the keywords ‘wheat’, ‘Australia’ and ‘yield’ in the Scopus database; a review of

online publications from Australian industry-specific bodies (such as the Grains Research and

Development Corporation, GRDC) and relevant government agencies; and a set of four

interviews with Australian agribusiness professionals, credit managers and environmental

finance professionals. Typically, industry body publications proved the most useful in

demonstrating the materiality of specific environmental risks to the wheat industry, given their

focus and access to information specific to the Australian context.

A risk was considered material if it was clearly capable of being a significant determinant of

either yields, prices or costs, either in the short- or long-term. It was not practicable to set

quantitative thresholds for significance, but where possible we have provided quantitative

evidence in support of our judgment. We consider historical average conditions to be the

baseline: a risk is therefore only significant if it results in a deviation (in a negative direction)

from this baseline, either in the short- or long-term. It should be noted that risk is the product

of the probability of occurrence and the magnitude of impact, and it is therefore appropriate to

include some factors which are low impact but high probability, and vice versa. In addition,

some factors have been included on the basis of externalities which are currently not fully

priced, but which may become more appropriately priced in the medium to long term.

Finally, to keep this paper concise, we excluded weather, climate, energy and air emissions

risks, as these are already relatively well understood. The results of these steps are summarized

in Table 1 below. Factors relevant to wheat farming are highlighted in gray, with light gray

indicating the factors that are considered material, but not included in the following discussion.

Table 1: Agriculture – Environmental and Natural Capital Risk Factors

Thematic Area Risk Factor Sub-Risk Factor

Water

Water Availability Growing Season Average Rainfall (Lower Quantity or Increased Variability

Excessive Rainfall

Water Use Efficiency Crop Water Use Efficiency

Pasture Water Use Efficiency

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

Animal Stock Watering Efficiency

Farm Water Use Efficiency

Water Rights Quantity

Price

Irrigation Technology Failure

Water Quality

Salinity Management

Water Contamination

Water Acidity

Weather and

Climate

Heat Stress

Frost Damage

Extreme Weather Events

Land Use and

Pollution

Fertiliser Use

Quantity

Price

Run-Off

Appropriate Application

Soil Organic Carbon

Soil Erosion Water Erosion

Wind Erosion

Soil Acidification

Soil Salinity

Soil Compaction

Organic Contaminants

Heavy Metals

Waste Management

Biodiversity and

Ecosystems

GMO Contamination

Pests and Diseases

Weeds

Biodiversity

Livestock Health/Animal Welfare

Pasture Cover and Composition

Energy Use On-Farm Energy Use

Fertiliser Production and Transport Energy Use

Air Emissions

Carbon Dioxide

Energy Use Emissions

Fertiliser Production and Transport Energy Emissions

Direct Land Use Change Emissions

Methane Enteric Fermentation Emissions

Manure Management Emissions

Nitrous Oxide Fertiliser Application Emissions

F-gases (Hydrofluorocarbons, Perfluorocarbons and Sulfur Hexafluoride)

The same sources of evidence were then used to explore each of these risks in further detail. In

the following section, for each key risk, we discuss why it is material, what mitigation options

are available, and what information a lender would require to assess and monitor these risks,

Animal Stock Watering Efficiency

Farm Water Use Efficiency

Water Rights Quantity

Price

Irrigation Technology Failure

Water Quality

Salinity Management

Water Contamination

Water Acidity

Weather and

Climate

Heat Stress

Frost Damage

Extreme Weather Events

Land Use and

Pollution

Fertiliser Use

Quantity

Price

Run-Off

Appropriate Application

Soil Organic Carbon

Soil Erosion Water Erosion

Wind Erosion

Soil Acidification

Soil Salinity

Soil Compaction

Organic Contaminants

Heavy Metals

Waste Management

Biodiversity and

Ecosystems

GMO Contamination

Pests and Diseases

Weeds

Biodiversity

Livestock Health/Animal Welfare

Pasture Cover and Composition

Energy Use On-Farm Energy Use

Fertiliser Production and Transport Energy Use

Air Emissions

Carbon Dioxide

Energy Use Emissions

Fertiliser Production and Transport Energy Emissions

Direct Land Use Change Emissions

Methane Enteric Fermentation Emissions

Manure Management Emissions

Nitrous Oxide Fertiliser Application Emissions

F-gases (Hydrofluorocarbons, Perfluorocarbons and Sulfur Hexafluoride)

The same sources of evidence were then used to explore each of these risks in further detail. In

the following section, for each key risk, we discuss why it is material, what mitigation options

are available, and what information a lender would require to assess and monitor these risks,

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

either quantitatively or qualitatively. The key risks identified for wheat can, for ease of

discussion, be grouped into the following headings: water; fertiliser use; soil health; pests,

diseases and weeds, and biodiversity.

Hoepner et al. (2014) point out that banks can adopt two different approaches to assess the

credit-worthiness of a borrower. The first is the traditional approach to credit risk assessments

or ‘transaction-based banking’, which is based on quantitative and easily verifiable information,

predominantly financial metrics. The second is ‘relationship banking’, in which lending decisions

are based on intangible factors which are harder to quantify, often collected manually and

difficult to verify (e.g. managerial competence). The authors highlight a growing body of

literature showing that the use of intangible information in tandem with financial metrics can

lead to better credit risk assessments than those based only on financial factors. Hence we have

considered both quantitative and qualitative information that could contribute to assessing

each risk.

4 Natural capital risks and dependencies in Australian wheat farming

Most of Australia’s grain production is located on a narrow belt of land (in the east, south east

and south west of the country), known as the Wheatbelt or Grainbelt, which benefits from a

temperate climate, sufficient rainfall (on average 300-600mm/year) and relatively fertile soils

(Land Commodities 2012). At 46 million hectares, the Wheatbelt comprises 6% of Australia’s

total land area (Land Commodities 2012). Despite the name, farmers in the Wheatbelt also

raise livestock and grow other crops in addition to wheat. In 2014-15, wheat was grown on

about 57% (13.8 million ha) of total Wheatbelt farmland (24.3 million ha) (Farrell 2015).

The majority of Australia’s grain, including around 90% of wheat, is grown in a single winter

growing season, with precise sowing and harvesting periods varying by region (Land

Commodities 2012). There is minimal water available for irrigation across the Wheatbelt, hence

almost all grain in Australia is produced under a dryland cropping system (i.e. crops are rain-fed,

not irrigated). Rainwater availability and efficiency of use is therefore a key natural capital

risk/dependency for Australian wheat farming.

4.1 Water

4.1.1 Overview

The level of rainfall is the biggest predictor of agricultural productivity in a given year, and long-

term averages are a key determinant of land prices (Land Commodities 2012). Rainwater

availability for any crop is a function of four inter-related dimensions (Land Commodities 2012):

• Quantity (total annual average rainfall);

either quantitatively or qualitatively. The key risks identified for wheat can, for ease of

discussion, be grouped into the following headings: water; fertiliser use; soil health; pests,

diseases and weeds, and biodiversity.

Hoepner et al. (2014) point out that banks can adopt two different approaches to assess the

credit-worthiness of a borrower. The first is the traditional approach to credit risk assessments

or ‘transaction-based banking’, which is based on quantitative and easily verifiable information,

predominantly financial metrics. The second is ‘relationship banking’, in which lending decisions

are based on intangible factors which are harder to quantify, often collected manually and

difficult to verify (e.g. managerial competence). The authors highlight a growing body of

literature showing that the use of intangible information in tandem with financial metrics can

lead to better credit risk assessments than those based only on financial factors. Hence we have

considered both quantitative and qualitative information that could contribute to assessing

each risk.

4 Natural capital risks and dependencies in Australian wheat farming

Most of Australia’s grain production is located on a narrow belt of land (in the east, south east

and south west of the country), known as the Wheatbelt or Grainbelt, which benefits from a

temperate climate, sufficient rainfall (on average 300-600mm/year) and relatively fertile soils

(Land Commodities 2012). At 46 million hectares, the Wheatbelt comprises 6% of Australia’s

total land area (Land Commodities 2012). Despite the name, farmers in the Wheatbelt also

raise livestock and grow other crops in addition to wheat. In 2014-15, wheat was grown on

about 57% (13.8 million ha) of total Wheatbelt farmland (24.3 million ha) (Farrell 2015).

The majority of Australia’s grain, including around 90% of wheat, is grown in a single winter

growing season, with precise sowing and harvesting periods varying by region (Land

Commodities 2012). There is minimal water available for irrigation across the Wheatbelt, hence

almost all grain in Australia is produced under a dryland cropping system (i.e. crops are rain-fed,

not irrigated). Rainwater availability and efficiency of use is therefore a key natural capital

risk/dependency for Australian wheat farming.

4.1 Water

4.1.1 Overview

The level of rainfall is the biggest predictor of agricultural productivity in a given year, and long-

term averages are a key determinant of land prices (Land Commodities 2012). Rainwater

availability for any crop is a function of four inter-related dimensions (Land Commodities 2012):

• Quantity (total annual average rainfall);

9

• Timing (in particular, the amount received during the growing season, and the amount

received in excessive downpours which can cause damage during the growing season or

at harvest time);

• Reliability (the variability of both quantity and timing from year to year); and

• Water use efficiency (the proportion of rainfall which becomes available to the crop

itself, which itself is a function of various factors including soil characteristics, drainage,

topography, timing of rainfall events, climatic conditions after rainfall, nitrogen supply,

weed cover and crop characteristics).

In a relatively small study (based on rainfall data from six weather stations in New South Wales

over six years) CelsiusPro AG (2010) found a linear relationship between wheat yields and

cumulative rainfall during the late growing season (1 st August to 31 st September), with rainfall

over this period explaining 90% of the annual variation in wheat yield. This suggests that every

millimeter less rainfall in the late growing season would result in a decrease in yield of 0.0188

t/ha (compared with average yields of around 1.5 t/ha). Assuming an average farm-gate price of

A$250-300/t, this would translate into a decrease in earnings of A$4.70-5.64/ha/mm. This is

significant in the context of typical profit margins of 10-20% or roughly A$37.50-90.00/ha based

on the same yield and price assumptions. 2 While further work is required to establish whether

these implications hold for other regions and time periods, it does suggest that the quantity of

rainfall during the late growing season is a critical component of water risk for wheat.

4.1.2 Risk mitigation

Farmers can mitigate the impacts of rainfall variability in several ways. Huda (1994) concludes

that yields can be protected by reducing the area sown when rainfall is low (less than 40mm) in

the early growing season (1st April -15th June) and increasing the area sown when rainfall is high

(greater than 100mm). Timing is also important: farmers should decrease planting when the

opening of the rainy season is delayed, and increase planting when the opening is early.

Choosing to grow a longer-duration wheat cultivar in early rainfall years, or increasing sheep

stocking as an alternative to wheat during low rainfall years is another option given accurate

and early forecasting capabilities of growing season rainfall. A variety of actions can be taken to

improve crop water use efficiency, for example by increasing the depth of rooting (Turner

2004). However, this strategy is most effective on sandy soils in high-rainfall zones where

nitrogen may leach into the root zone, with neutral and sometimes even negative effects in clay

soils which experience limited wetting to root depth (Smith and Harris 1981).

4.1.3 Lender information requirements

In the short term, lenders providing finance to wheat farmers can assess likely rainfall quantity,

timing and variability according to location, by comparison with historical rainfall data. In

2 Own analysis. Indicative prices and profit margins from personal communication, Agribusiness finance manager,

August 12, 2016.

• Timing (in particular, the amount received during the growing season, and the amount

received in excessive downpours which can cause damage during the growing season or

at harvest time);

• Reliability (the variability of both quantity and timing from year to year); and

• Water use efficiency (the proportion of rainfall which becomes available to the crop

itself, which itself is a function of various factors including soil characteristics, drainage,

topography, timing of rainfall events, climatic conditions after rainfall, nitrogen supply,

weed cover and crop characteristics).

In a relatively small study (based on rainfall data from six weather stations in New South Wales

over six years) CelsiusPro AG (2010) found a linear relationship between wheat yields and

cumulative rainfall during the late growing season (1 st August to 31 st September), with rainfall

over this period explaining 90% of the annual variation in wheat yield. This suggests that every

millimeter less rainfall in the late growing season would result in a decrease in yield of 0.0188

t/ha (compared with average yields of around 1.5 t/ha). Assuming an average farm-gate price of

A$250-300/t, this would translate into a decrease in earnings of A$4.70-5.64/ha/mm. This is

significant in the context of typical profit margins of 10-20% or roughly A$37.50-90.00/ha based

on the same yield and price assumptions. 2 While further work is required to establish whether

these implications hold for other regions and time periods, it does suggest that the quantity of

rainfall during the late growing season is a critical component of water risk for wheat.

4.1.2 Risk mitigation

Farmers can mitigate the impacts of rainfall variability in several ways. Huda (1994) concludes

that yields can be protected by reducing the area sown when rainfall is low (less than 40mm) in

the early growing season (1st April -15th June) and increasing the area sown when rainfall is high

(greater than 100mm). Timing is also important: farmers should decrease planting when the

opening of the rainy season is delayed, and increase planting when the opening is early.

Choosing to grow a longer-duration wheat cultivar in early rainfall years, or increasing sheep

stocking as an alternative to wheat during low rainfall years is another option given accurate

and early forecasting capabilities of growing season rainfall. A variety of actions can be taken to

improve crop water use efficiency, for example by increasing the depth of rooting (Turner

2004). However, this strategy is most effective on sandy soils in high-rainfall zones where

nitrogen may leach into the root zone, with neutral and sometimes even negative effects in clay

soils which experience limited wetting to root depth (Smith and Harris 1981).

4.1.3 Lender information requirements

In the short term, lenders providing finance to wheat farmers can assess likely rainfall quantity,

timing and variability according to location, by comparison with historical rainfall data. In

2 Own analysis. Indicative prices and profit margins from personal communication, Agribusiness finance manager,

August 12, 2016.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

Australia, Bureau of Meteorology data is likely to be sufficient, but could be supplemented with

farm-specific rainfall data, particularly for remote areas. In addition, lenders could qualitatively

determine whether the farmer has the necessary knowledge and track record to deal with

variable rainfall patterns and to employ appropriate risk mitigation measures as described

above and in Table 2. In the longer term, shifting rainfall patterns could change the risk profile

of wheat farms. Assessing this risk requires inputs from state-of-the-art climatic models

producing decadal and regional projections.

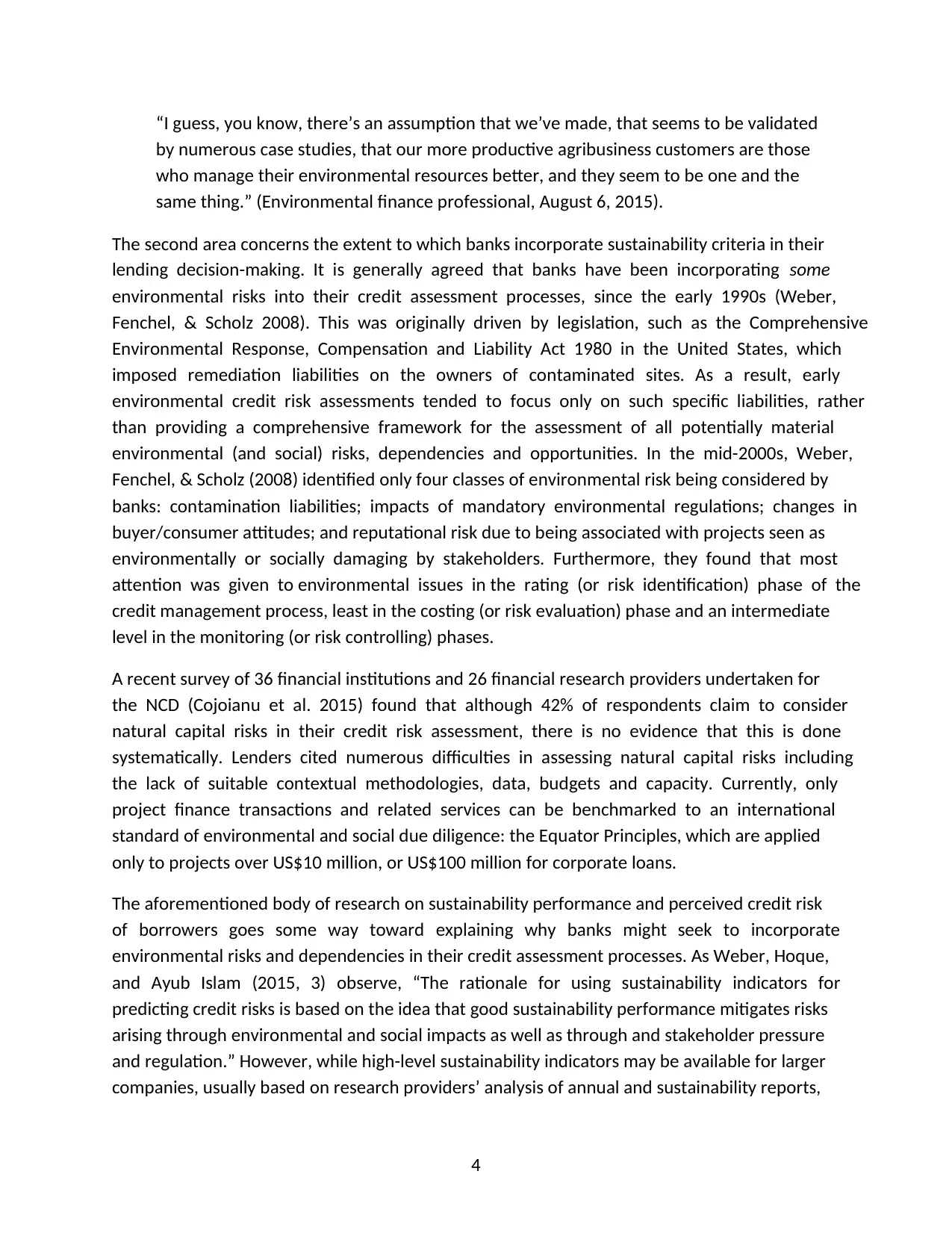

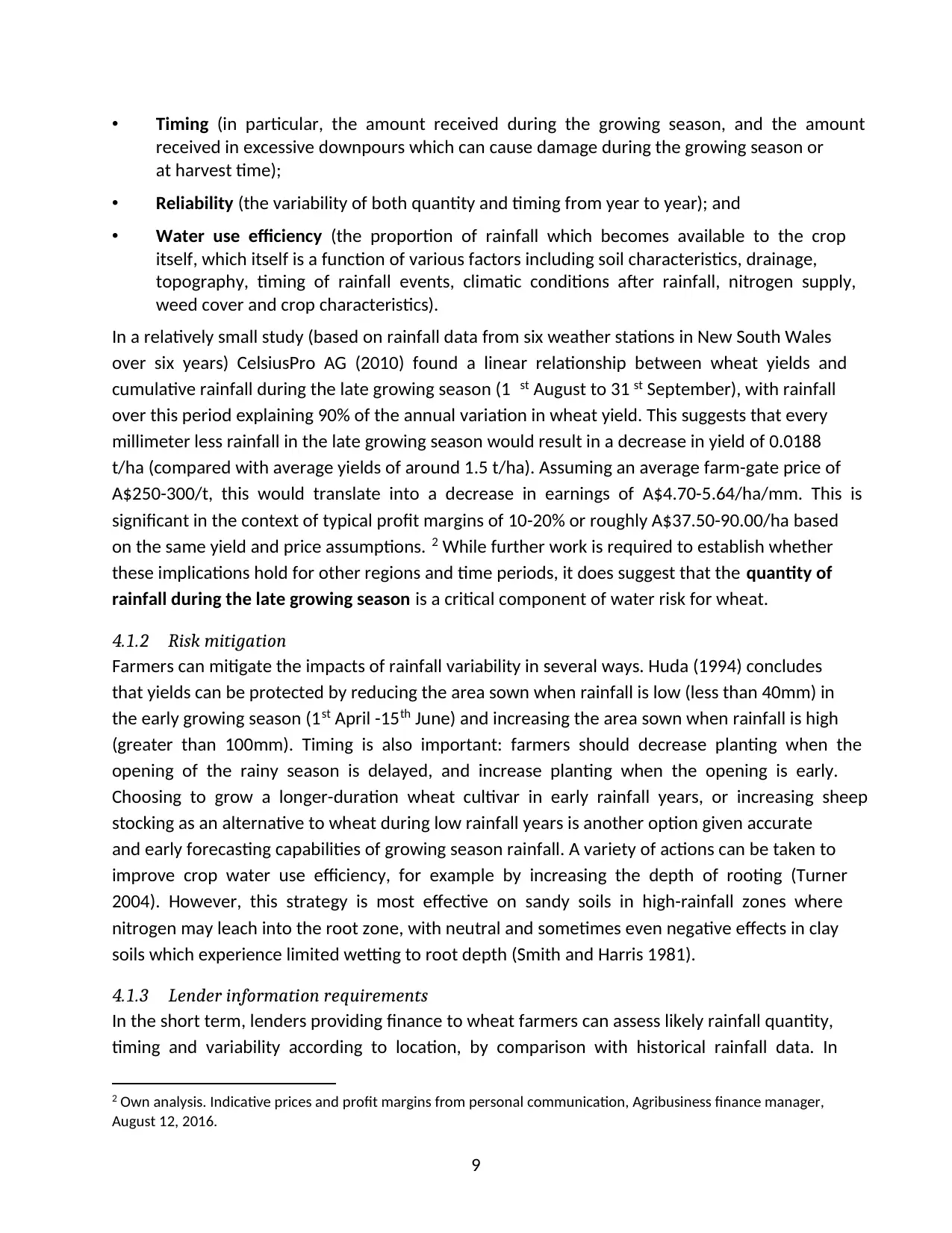

Table 2: Water risks, information needs and data sources

Risk Factor Timeframe Scale Information Need Data Sources

Growing Season Rainfall

Short term Region to

farm

Region- or farm-

specific critical growing

season dates

Bureau of Meteorology or farm-

specific rainfall datasets combined

with regional- or farm-specific yield

records

Short term Region to

farm

Region-specific

historical average

growing season rainfall

and variability (e.g.

over 10 years)

Bureau of Meteorology or farm-

specific rainfall datasets

Short term Farm

Farmer’s ability to

predict and deal with

variability

Farmer questionnaire

Long term Region

Projected changes in

growing season rainfall

patterns

Regional outputs from long-term

climatic models

Harvesting Season

Excessive Rainfall Short term Region to

farm

Farm exposure to

excessive rainfall

during growing season

or harvesting season

Farmer questionnaire on historical

crop damage in growing or

harvesting season.

Bureau of Meteorology or farm-

specific rainfall datasets.

Crop Water Use

Efficiency

Short term Farm

Recent historical

average water use

efficiency, compared

with the same data for

similar farms

Farmer yield data and Bureau of

Meteorology or farm-specific

rainfall datasets

Short term Farm

Farmer’s ability to

improve water use

efficiency

Farmer questionnaire

Australia, Bureau of Meteorology data is likely to be sufficient, but could be supplemented with

farm-specific rainfall data, particularly for remote areas. In addition, lenders could qualitatively

determine whether the farmer has the necessary knowledge and track record to deal with

variable rainfall patterns and to employ appropriate risk mitigation measures as described

above and in Table 2. In the longer term, shifting rainfall patterns could change the risk profile

of wheat farms. Assessing this risk requires inputs from state-of-the-art climatic models

producing decadal and regional projections.

Table 2: Water risks, information needs and data sources

Risk Factor Timeframe Scale Information Need Data Sources

Growing Season Rainfall

Short term Region to

farm

Region- or farm-

specific critical growing

season dates

Bureau of Meteorology or farm-

specific rainfall datasets combined

with regional- or farm-specific yield

records

Short term Region to

farm

Region-specific

historical average

growing season rainfall

and variability (e.g.

over 10 years)

Bureau of Meteorology or farm-

specific rainfall datasets

Short term Farm

Farmer’s ability to

predict and deal with

variability

Farmer questionnaire

Long term Region

Projected changes in

growing season rainfall

patterns

Regional outputs from long-term

climatic models

Harvesting Season

Excessive Rainfall Short term Region to

farm

Farm exposure to

excessive rainfall

during growing season

or harvesting season

Farmer questionnaire on historical

crop damage in growing or

harvesting season.

Bureau of Meteorology or farm-

specific rainfall datasets.

Crop Water Use

Efficiency

Short term Farm

Recent historical

average water use

efficiency, compared

with the same data for

similar farms

Farmer yield data and Bureau of

Meteorology or farm-specific

rainfall datasets

Short term Farm

Farmer’s ability to

improve water use

efficiency

Farmer questionnaire

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

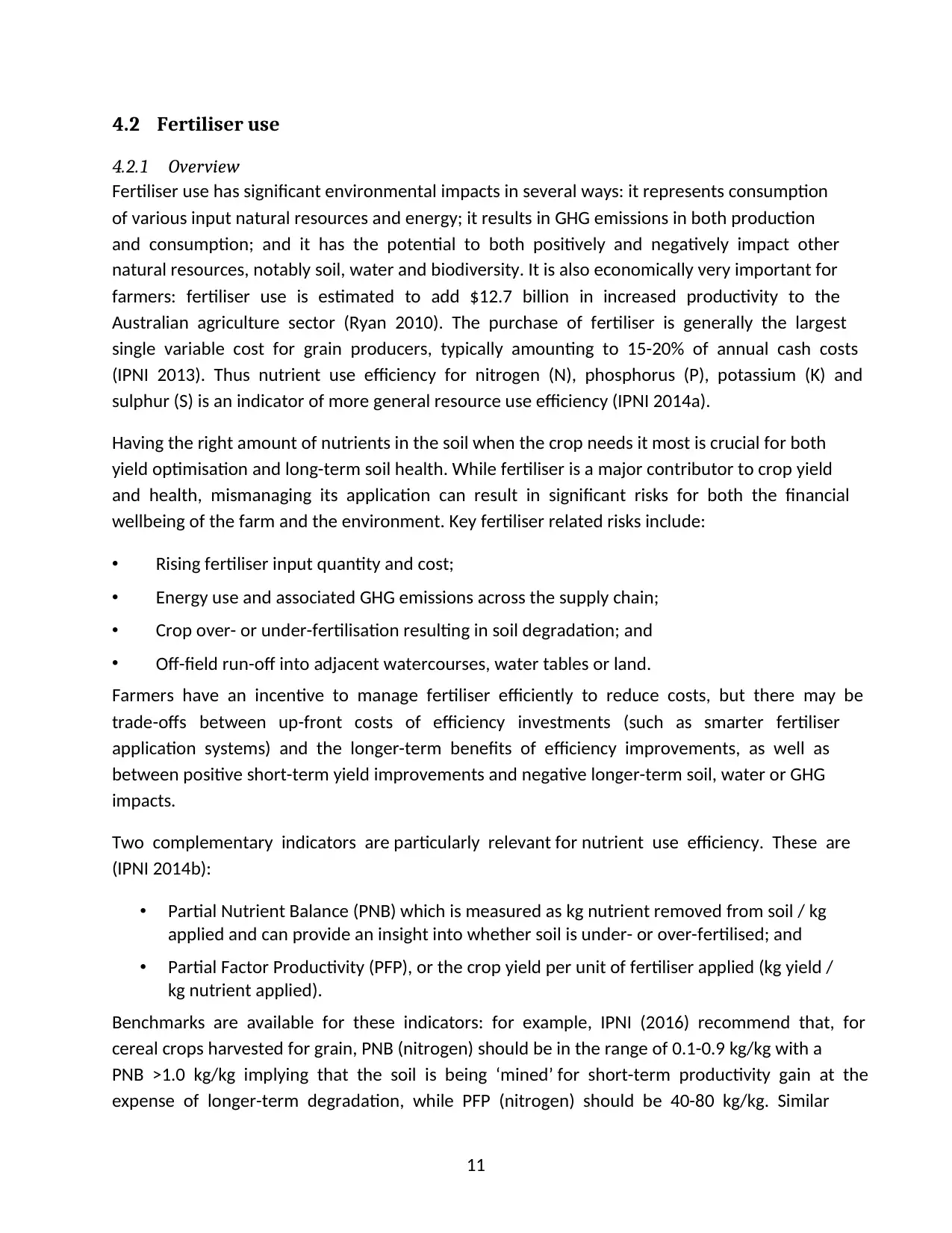

4.2 Fertiliser use

4.2.1 Overview

Fertiliser use has significant environmental impacts in several ways: it represents consumption

of various input natural resources and energy; it results in GHG emissions in both production

and consumption; and it has the potential to both positively and negatively impact other

natural resources, notably soil, water and biodiversity. It is also economically very important for

farmers: fertiliser use is estimated to add $12.7 billion in increased productivity to the

Australian agriculture sector (Ryan 2010). The purchase of fertiliser is generally the largest

single variable cost for grain producers, typically amounting to 15-20% of annual cash costs

(IPNI 2013). Thus nutrient use efficiency for nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) and

sulphur (S) is an indicator of more general resource use efficiency (IPNI 2014a).

Having the right amount of nutrients in the soil when the crop needs it most is crucial for both

yield optimisation and long-term soil health. While fertiliser is a major contributor to crop yield

and health, mismanaging its application can result in significant risks for both the financial

wellbeing of the farm and the environment. Key fertiliser related risks include:

• Rising fertiliser input quantity and cost;

• Energy use and associated GHG emissions across the supply chain;

• Crop over- or under-fertilisation resulting in soil degradation; and

• Off-field run-off into adjacent watercourses, water tables or land.

Farmers have an incentive to manage fertiliser efficiently to reduce costs, but there may be

trade-offs between up-front costs of efficiency investments (such as smarter fertiliser

application systems) and the longer-term benefits of efficiency improvements, as well as

between positive short-term yield improvements and negative longer-term soil, water or GHG

impacts.

Two complementary indicators are particularly relevant for nutrient use efficiency. These are

(IPNI 2014b):

• Partial Nutrient Balance (PNB) which is measured as kg nutrient removed from soil / kg

applied and can provide an insight into whether soil is under- or over-fertilised; and

• Partial Factor Productivity (PFP), or the crop yield per unit of fertiliser applied (kg yield /

kg nutrient applied).

Benchmarks are available for these indicators: for example, IPNI (2016) recommend that, for

cereal crops harvested for grain, PNB (nitrogen) should be in the range of 0.1-0.9 kg/kg with a

PNB >1.0 kg/kg implying that the soil is being ‘mined’ for short-term productivity gain at the

expense of longer-term degradation, while PFP (nitrogen) should be 40-80 kg/kg. Similar

4.2 Fertiliser use

4.2.1 Overview

Fertiliser use has significant environmental impacts in several ways: it represents consumption

of various input natural resources and energy; it results in GHG emissions in both production

and consumption; and it has the potential to both positively and negatively impact other

natural resources, notably soil, water and biodiversity. It is also economically very important for

farmers: fertiliser use is estimated to add $12.7 billion in increased productivity to the

Australian agriculture sector (Ryan 2010). The purchase of fertiliser is generally the largest

single variable cost for grain producers, typically amounting to 15-20% of annual cash costs

(IPNI 2013). Thus nutrient use efficiency for nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) and

sulphur (S) is an indicator of more general resource use efficiency (IPNI 2014a).

Having the right amount of nutrients in the soil when the crop needs it most is crucial for both

yield optimisation and long-term soil health. While fertiliser is a major contributor to crop yield

and health, mismanaging its application can result in significant risks for both the financial

wellbeing of the farm and the environment. Key fertiliser related risks include:

• Rising fertiliser input quantity and cost;

• Energy use and associated GHG emissions across the supply chain;

• Crop over- or under-fertilisation resulting in soil degradation; and

• Off-field run-off into adjacent watercourses, water tables or land.

Farmers have an incentive to manage fertiliser efficiently to reduce costs, but there may be

trade-offs between up-front costs of efficiency investments (such as smarter fertiliser

application systems) and the longer-term benefits of efficiency improvements, as well as

between positive short-term yield improvements and negative longer-term soil, water or GHG

impacts.

Two complementary indicators are particularly relevant for nutrient use efficiency. These are

(IPNI 2014b):

• Partial Nutrient Balance (PNB) which is measured as kg nutrient removed from soil / kg

applied and can provide an insight into whether soil is under- or over-fertilised; and

• Partial Factor Productivity (PFP), or the crop yield per unit of fertiliser applied (kg yield /

kg nutrient applied).

Benchmarks are available for these indicators: for example, IPNI (2016) recommend that, for

cereal crops harvested for grain, PNB (nitrogen) should be in the range of 0.1-0.9 kg/kg with a

PNB >1.0 kg/kg implying that the soil is being ‘mined’ for short-term productivity gain at the

expense of longer-term degradation, while PFP (nitrogen) should be 40-80 kg/kg. Similar

12

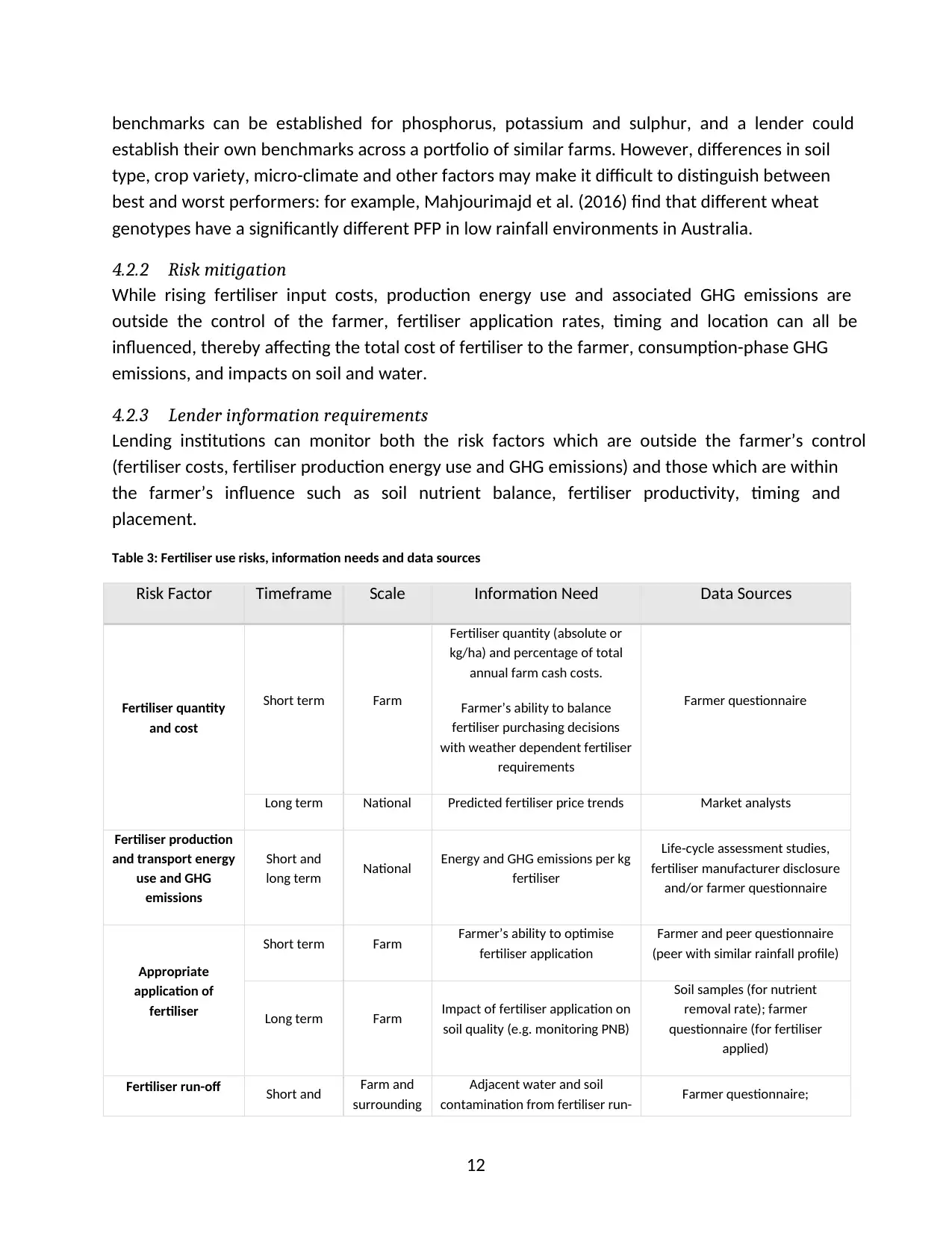

benchmarks can be established for phosphorus, potassium and sulphur, and a lender could

establish their own benchmarks across a portfolio of similar farms. However, differences in soil

type, crop variety, micro-climate and other factors may make it difficult to distinguish between

best and worst performers: for example, Mahjourimajd et al. (2016) find that different wheat

genotypes have a significantly different PFP in low rainfall environments in Australia.

4.2.2 Risk mitigation

While rising fertiliser input costs, production energy use and associated GHG emissions are

outside the control of the farmer, fertiliser application rates, timing and location can all be

influenced, thereby affecting the total cost of fertiliser to the farmer, consumption-phase GHG

emissions, and impacts on soil and water.

4.2.3 Lender information requirements

Lending institutions can monitor both the risk factors which are outside the farmer’s control

(fertiliser costs, fertiliser production energy use and GHG emissions) and those which are within

the farmer’s influence such as soil nutrient balance, fertiliser productivity, timing and

placement.

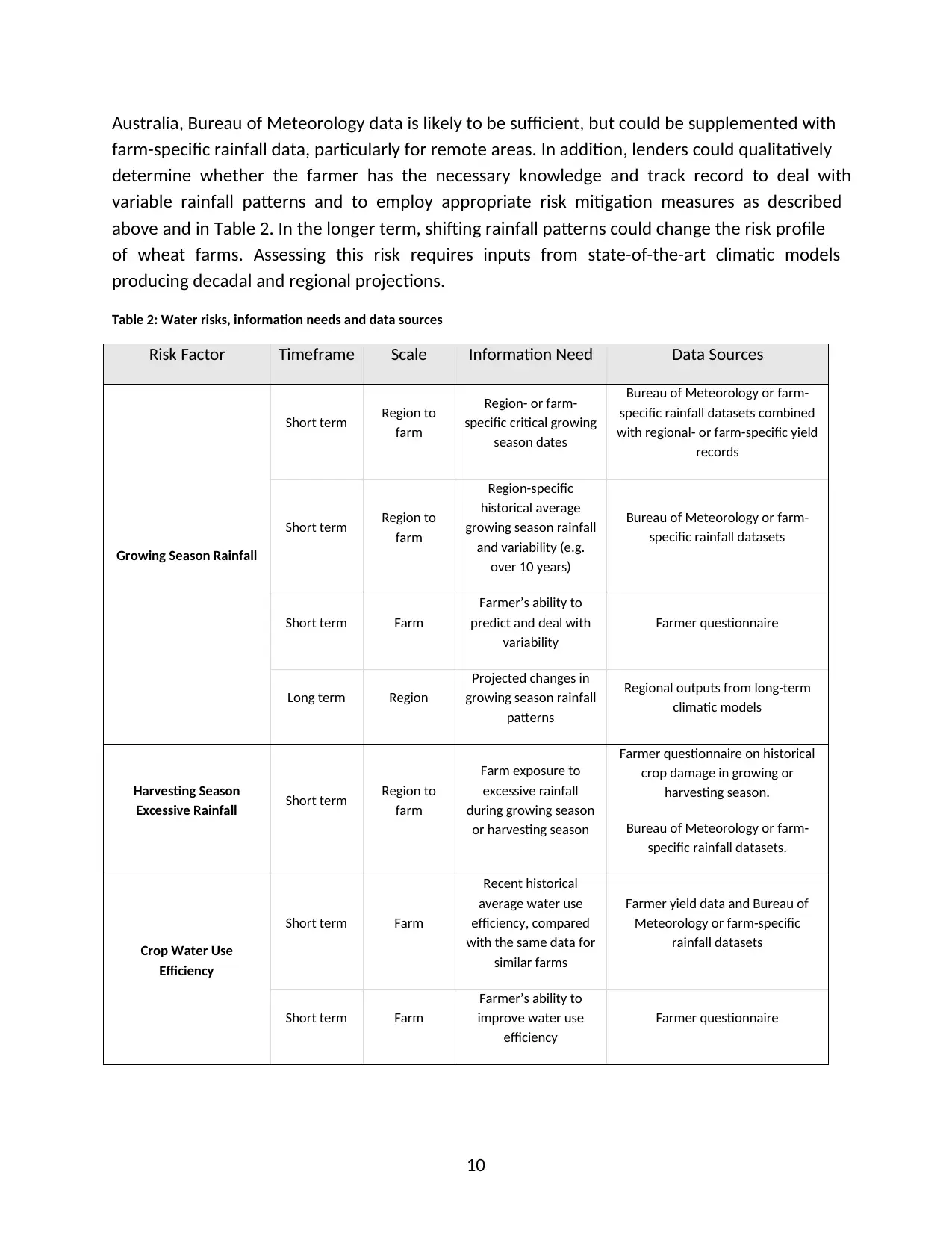

Table 3: Fertiliser use risks, information needs and data sources

Risk Factor Timeframe Scale Information Need Data Sources

Fertiliser quantity

and cost

Short term Farm

Fertiliser quantity (absolute or

kg/ha) and percentage of total

annual farm cash costs.

Farmer’s ability to balance

fertiliser purchasing decisions

with weather dependent fertiliser

requirements

Farmer questionnaire

Long term National Predicted fertiliser price trends Market analysts

Fertiliser production

and transport energy

use and GHG

emissions

Short and

long term National Energy and GHG emissions per kg

fertiliser

Life-cycle assessment studies,

fertiliser manufacturer disclosure

and/or farmer questionnaire

Appropriate

application of

fertiliser

Short term Farm Farmer’s ability to optimise

fertiliser application

Farmer and peer questionnaire

(peer with similar rainfall profile)

Long term Farm Impact of fertiliser application on

soil quality (e.g. monitoring PNB)

Soil samples (for nutrient

removal rate); farmer

questionnaire (for fertiliser

applied)

Fertiliser run-off Short and Farm and

surrounding

Adjacent water and soil

contamination from fertiliser run- Farmer questionnaire;

benchmarks can be established for phosphorus, potassium and sulphur, and a lender could

establish their own benchmarks across a portfolio of similar farms. However, differences in soil

type, crop variety, micro-climate and other factors may make it difficult to distinguish between

best and worst performers: for example, Mahjourimajd et al. (2016) find that different wheat

genotypes have a significantly different PFP in low rainfall environments in Australia.

4.2.2 Risk mitigation

While rising fertiliser input costs, production energy use and associated GHG emissions are

outside the control of the farmer, fertiliser application rates, timing and location can all be

influenced, thereby affecting the total cost of fertiliser to the farmer, consumption-phase GHG

emissions, and impacts on soil and water.

4.2.3 Lender information requirements

Lending institutions can monitor both the risk factors which are outside the farmer’s control

(fertiliser costs, fertiliser production energy use and GHG emissions) and those which are within

the farmer’s influence such as soil nutrient balance, fertiliser productivity, timing and

placement.

Table 3: Fertiliser use risks, information needs and data sources

Risk Factor Timeframe Scale Information Need Data Sources

Fertiliser quantity

and cost

Short term Farm

Fertiliser quantity (absolute or

kg/ha) and percentage of total

annual farm cash costs.

Farmer’s ability to balance

fertiliser purchasing decisions

with weather dependent fertiliser

requirements

Farmer questionnaire

Long term National Predicted fertiliser price trends Market analysts

Fertiliser production

and transport energy

use and GHG

emissions

Short and

long term National Energy and GHG emissions per kg

fertiliser

Life-cycle assessment studies,

fertiliser manufacturer disclosure

and/or farmer questionnaire

Appropriate

application of

fertiliser

Short term Farm Farmer’s ability to optimise

fertiliser application

Farmer and peer questionnaire

(peer with similar rainfall profile)

Long term Farm Impact of fertiliser application on

soil quality (e.g. monitoring PNB)

Soil samples (for nutrient

removal rate); farmer

questionnaire (for fertiliser

applied)

Fertiliser run-off Short and Farm and

surrounding

Adjacent water and soil

contamination from fertiliser run- Farmer questionnaire;

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 24

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.