Developing Leadership: Action Learning in Undergraduate Education

VerifiedAdded on 2021/08/23

|9

|9040

|129

Report

AI Summary

This report explores the limitations of traditional classroom-based leadership development programs and proposes an action learning approach as a more effective alternative. It argues that leadership is best learned through practical, real-world experiences rather than abstract concepts and case studies. The report highlights the high costs and low transferability of traditional programs, emphasizing the importance of applying learned skills in the context where they will be used. Action learning, which involves experiential exercises in personal or professional lives, is presented as a way to foster deeper understanding and transform day-to-day leadership practices. The authors share their experience in applying this action learning approach in an undergraduate leadership course, advocating for a shift from passive learning to active experimentation in leadership development.

Page 69 - Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, Volume 45, 2018

ABSTRACT

University leadership courses or corporate leadership development programs traditionally offer classroom -based instruction

pertaining to the theories, attributes, and behaviors of leaders. Although these activities may spark increased awareness and

understanding of leadership, this learning is not easily transferable to the workplace. Indeed, transference of learning is a

significant issue not only in traditional leadership education and training, but in any learning program that take learners away from

the context in which they will be applying their new skills. To address these deficiencies in transference, we propose an action

learning approach that invites individuals to undertake practical exercises in their personal or professional lives as a means of

building leadership skills “in context.” In this paper, we share our experience in applying an action learning approach in an

undergraduate leadership course.

INTRODUCTION

Because effective leadership is central to organizational success, the development of leadership capacity is an ongoing

concern for organizations (Chakrabarti, 2009). Traditionally, leadership development, whether through organizationally -based

workshops or university classes, has occurred within a classroom setting (Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturm & McKee, 2014; Quatro,

Waldman, & Galvin, 2007). In this manner, leadership has been treated like another subject such as mathematics or English that

requires formal lessons so that individuals may master its fundamentals. Indeed, according to an American Society of Training and

Development survey, leadership development occurs in a classroom setting for 85% of the companies surveyed (Day et al., 2014).

However, there is growing concern that these high cost programs are poorly transferable.

Alternatives to classroom-based learning are needed to ensure that learning about leadership readily translates into improved

leadership. But, what is the best way for individuals to learn how to lead? Through classroom instruction, case studies, self -

assessments, exercises, or real-life experiences? In this paper, we propose that the best way for individuals to learn to lead is through

experiential exercises undertaken in the context in which new learnings or skills will be applied (i.e., an action learning approach).

We argue that leadership is something that is learned primarily by doing it.

Absorbing theories and ideas on the topic of leadership, a common approach to leadership development (Morrison Rha, &

Helfman, 2003), allows individuals to become knowledgeable about leadership primarily as an abstract concept. Analyzing case

studies helps to bring these concepts to life. Completing self-assessment questionnaires and 360o assessments helps individuals

understand their potential strengths and weaknesses as leaders. Participating in exercises in a classroom setting helps individuals

develop insights into the leadership process and their own tendencies. In all cases, however, individuals are left to determine how

best to apply what they have learned in the exercises to the ‘real world.’ We contend that it is only by actually testing or applying

concepts and experimenting with leadership in ‘real life’ that students develop a profound sense of their own leadership capabilities

and, consequently, are able to transform their day-to-day leadership practices. Our approach is grounded on the belief that leadership

development “is a continuous process that can take place anywhere (Fulmer, 1997). Leadership development in practice today means

helping people learn from their work rather than taking them away from their work to learn (Moxley & O’Connor Wilson,

1998)” (Day, 2000, p. 586).

In this paper, we discuss how organizations, including universities, have traditionally approached the task of developing

leaders through classroom-based instruction. We then address the downsides and costs of this approach and consider an alternative

means of developing leaders outside the classroom setting. In particular, we propose action learning as a practical means of

developing leadership skills in a ‘natural,’ ‘embedded’ environment, one in which the leadership skills will be exercised. We

conclude this paper by describing how we have applied this action learning approach in an undergraduate leadership course.

Developing Leadership Through Leadership Experiences:

An Action Learning Approach

Céleste M. Grimard

Université du Québec à Montréal

grimard.celeste@uqam.ca

Sabrina Pellerin

Université du Québec à Montréal

pellerin.sabrina@courrier.uqam.ca

ABSTRACT

University leadership courses or corporate leadership development programs traditionally offer classroom -based instruction

pertaining to the theories, attributes, and behaviors of leaders. Although these activities may spark increased awareness and

understanding of leadership, this learning is not easily transferable to the workplace. Indeed, transference of learning is a

significant issue not only in traditional leadership education and training, but in any learning program that take learners away from

the context in which they will be applying their new skills. To address these deficiencies in transference, we propose an action

learning approach that invites individuals to undertake practical exercises in their personal or professional lives as a means of

building leadership skills “in context.” In this paper, we share our experience in applying an action learning approach in an

undergraduate leadership course.

INTRODUCTION

Because effective leadership is central to organizational success, the development of leadership capacity is an ongoing

concern for organizations (Chakrabarti, 2009). Traditionally, leadership development, whether through organizationally -based

workshops or university classes, has occurred within a classroom setting (Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturm & McKee, 2014; Quatro,

Waldman, & Galvin, 2007). In this manner, leadership has been treated like another subject such as mathematics or English that

requires formal lessons so that individuals may master its fundamentals. Indeed, according to an American Society of Training and

Development survey, leadership development occurs in a classroom setting for 85% of the companies surveyed (Day et al., 2014).

However, there is growing concern that these high cost programs are poorly transferable.

Alternatives to classroom-based learning are needed to ensure that learning about leadership readily translates into improved

leadership. But, what is the best way for individuals to learn how to lead? Through classroom instruction, case studies, self -

assessments, exercises, or real-life experiences? In this paper, we propose that the best way for individuals to learn to lead is through

experiential exercises undertaken in the context in which new learnings or skills will be applied (i.e., an action learning approach).

We argue that leadership is something that is learned primarily by doing it.

Absorbing theories and ideas on the topic of leadership, a common approach to leadership development (Morrison Rha, &

Helfman, 2003), allows individuals to become knowledgeable about leadership primarily as an abstract concept. Analyzing case

studies helps to bring these concepts to life. Completing self-assessment questionnaires and 360o assessments helps individuals

understand their potential strengths and weaknesses as leaders. Participating in exercises in a classroom setting helps individuals

develop insights into the leadership process and their own tendencies. In all cases, however, individuals are left to determine how

best to apply what they have learned in the exercises to the ‘real world.’ We contend that it is only by actually testing or applying

concepts and experimenting with leadership in ‘real life’ that students develop a profound sense of their own leadership capabilities

and, consequently, are able to transform their day-to-day leadership practices. Our approach is grounded on the belief that leadership

development “is a continuous process that can take place anywhere (Fulmer, 1997). Leadership development in practice today means

helping people learn from their work rather than taking them away from their work to learn (Moxley & O’Connor Wilson,

1998)” (Day, 2000, p. 586).

In this paper, we discuss how organizations, including universities, have traditionally approached the task of developing

leaders through classroom-based instruction. We then address the downsides and costs of this approach and consider an alternative

means of developing leaders outside the classroom setting. In particular, we propose action learning as a practical means of

developing leadership skills in a ‘natural,’ ‘embedded’ environment, one in which the leadership skills will be exercised. We

conclude this paper by describing how we have applied this action learning approach in an undergraduate leadership course.

Developing Leadership Through Leadership Experiences:

An Action Learning Approach

Céleste M. Grimard

Université du Québec à Montréal

grimard.celeste@uqam.ca

Sabrina Pellerin

Université du Québec à Montréal

pellerin.sabrina@courrier.uqam.ca

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Page 70 - Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, Volume 45, 2018

TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

EFFECTIVENESS IN DEVELOPING LEADERS

Traditional leadership development programs remove students and professionals from their natural environment and

reassemble them in classrooms. Typically, after a theoretical grounding, these individuals are asked to evaluate case studies that

describe situations faced by leaders. They discuss the case study, evaluate possible solutions and prepare a presentation to their

colleagues on how to solve the identified problems (Fulmer, 1997). This case-based approach to leadership development relies on

students’ ability to determine how to apply what they have learned in the case analysis process to the ‘real world,’ “make

applications when and if similar situations presented themselves” (Fulmer, 1997, p. 60), and bring back the “latest leadership

thinking” (Rowland, 2016, para. 2), personal lessons and some ‘practical’ tools to their workplaces. Although these types of activities

are intended to prepare students for workplace situations and challenges, transfer of learning rarely takes place, in part, because many

case studies are not easily transferable to learners’ work situations.

This traditional model of leadership development, referred to as the “chalk-and-talk model” (Rowland, 2016, para 9), is well

established but somewhat obsolete (Fulmer, 1997). On one hand, leadership courses are useful for accumulating knowledge and

concepts that are likely to be used in the future (Fulmer, 1997). Also, when leadership development programs are offered in a context

other than the workplace (i.e., universities, workshop environment), participants can see things differently, gain new perspectives of

their work and advance their analytical competencies (Fulmer, 1997) while distancing themselves from day -to-day work pressures

(Gurdjian, Halbeisen, & Lane, 2014). On the other hand, the classroom context is not the best way to develop the ‘holistic leaders’

that are needed in the business world (Quatro, Waldman, & Galvin, 2007). Leadership development must go beyond the classroom.

Needed skillsets are best developed in an organizational context (Quatro et al., 2007). Consequently, the emphasis of leadership

development should be experience, with classroom-based training used as a supplement (McCall, 2004) or complement (Quatro et

al., 2007) to leadership development, rather than as its essence.

Traditional leadership development employs a “one directional, one dimensional, one size fits all” approach (Myatt, 2012,

no page number) that encourages passivity rather than ownership. It is offered to groups of individuals who have different

backgrounds and competencies, all requiring different levels of development and evolving at various rates (Day et al., 2014). As

such, “it is highly unlikely that anyone would be able to develop fully as a leader merely through participation in a series of

programs, workshops, or seminars” (Day et al., 2014, p. 80). Others suggest that such programs can form misguided leaders (Quatro

et al., 2007) who lack essential leadership skills (such as interpersonal or strategic skills) (Volz -Peacock, Carson & Marquardt, 2016)

and who are not well prepared to face today’s challenges. As Quatro et al. (2007, p. 435) posit, given that these rational programs

focus on the development of analytical capabilities, they are a “possible driver of the preponderance of analytically -focused leaders”

who have a limited understanding of leadership beyond analytical challenges. In sum, traditional classroom -based leadership

development programs are not considered to be effective means of developing leaders (Volz -Peacock et al., 2016; Day, 2000).

RETURN ON INVESTMENT

Leadership development is an important cost center for organizations, given the investment required in both money and

time (Cromwell & Kolb, 2004). According to Gurdjian, Halbeisen, and Lane (2014), every year, American organizations invest

almost $14 billion in leadership development programs. Chakrabarti (2009), leader of the People Analytics and Employee

Engagement research practices at Bersin by Deloitte, indicates that their recent survey of corporate America found that organizations

invested nearly $500,000 in 2009 on leadership development, which ranged from $170,000 to nearly $1.3 million depending on

organizational size. Aside from corporate-based leadership development programs, such programs are available in universities,

colleges and business schools, but they tend to be costly (Volz-Peacock & al., 2016). For example, the cost of developing a leader in

a customized program in a top business school can be as much as $150,000 (Gurdjian et al., 2014).

Organizations may not be receiving an adequate return on their investment in leadership development. Effective programs

show evidence of positive transfer of learning, which takes place when “learning in one context improves performance in some other

context” (Perkins, & Salomon, 1992, p. 3) or when “trainees effectively apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes gained in a

training context to the job” (Newstrom, 1986 cited in Cromwell & Kolb, 2004, p. 450). For example, there is positive transfer of

learning in leadership development programs when participants apply new skills and competencies gained in the program in their

leadership practices in the workplace. These new competencies should be demonstrated and widespread in the work context for a

substantial period of time in order to affirm that positive transfer has occurred (Baldwin & Ford, 1988). However, traditional

classroom-based leadership development programs account for less than 10 % of managers’ development (Robinson &Wick, 1992).

A recent survey of corporate America found weaknesses in leadership skills at every level of most organizations in the study

(Chakrabarti, 2009). Moreover, participants tend to remember about 10 % of what is said in lectures (Gurdjian et al., 2014),

suggesting that traditional programs lack transferability (Day, 2000).

Regrettably, neither positive transfer nor performance improvement seem to materialize regularly after training programs

(Cromwell & Kolb, 2004). Lessons learned in a classroom context are not integrated firmly into participants’ knowledge and skill

base: “Soon after the course ends, people slip back into their previous behavioral patterns, and little lasting change or developmental

progress is achieved” (Day, 2000, p. 601). Accordingly, in their research, Hirst, Mann, Bain, Pirola-Merlo, & Richver (2004, p. 311)

found that there was “a lag between learning leadership skills and translating these skills into leadership behavior.” These researchers

posited that this delay was likely caused by the difficulty involved in translating learned skills and behaviors into practice. These

TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

EFFECTIVENESS IN DEVELOPING LEADERS

Traditional leadership development programs remove students and professionals from their natural environment and

reassemble them in classrooms. Typically, after a theoretical grounding, these individuals are asked to evaluate case studies that

describe situations faced by leaders. They discuss the case study, evaluate possible solutions and prepare a presentation to their

colleagues on how to solve the identified problems (Fulmer, 1997). This case-based approach to leadership development relies on

students’ ability to determine how to apply what they have learned in the case analysis process to the ‘real world,’ “make

applications when and if similar situations presented themselves” (Fulmer, 1997, p. 60), and bring back the “latest leadership

thinking” (Rowland, 2016, para. 2), personal lessons and some ‘practical’ tools to their workplaces. Although these types of activities

are intended to prepare students for workplace situations and challenges, transfer of learning rarely takes place, in part, because many

case studies are not easily transferable to learners’ work situations.

This traditional model of leadership development, referred to as the “chalk-and-talk model” (Rowland, 2016, para 9), is well

established but somewhat obsolete (Fulmer, 1997). On one hand, leadership courses are useful for accumulating knowledge and

concepts that are likely to be used in the future (Fulmer, 1997). Also, when leadership development programs are offered in a context

other than the workplace (i.e., universities, workshop environment), participants can see things differently, gain new perspectives of

their work and advance their analytical competencies (Fulmer, 1997) while distancing themselves from day -to-day work pressures

(Gurdjian, Halbeisen, & Lane, 2014). On the other hand, the classroom context is not the best way to develop the ‘holistic leaders’

that are needed in the business world (Quatro, Waldman, & Galvin, 2007). Leadership development must go beyond the classroom.

Needed skillsets are best developed in an organizational context (Quatro et al., 2007). Consequently, the emphasis of leadership

development should be experience, with classroom-based training used as a supplement (McCall, 2004) or complement (Quatro et

al., 2007) to leadership development, rather than as its essence.

Traditional leadership development employs a “one directional, one dimensional, one size fits all” approach (Myatt, 2012,

no page number) that encourages passivity rather than ownership. It is offered to groups of individuals who have different

backgrounds and competencies, all requiring different levels of development and evolving at various rates (Day et al., 2014). As

such, “it is highly unlikely that anyone would be able to develop fully as a leader merely through participation in a series of

programs, workshops, or seminars” (Day et al., 2014, p. 80). Others suggest that such programs can form misguided leaders (Quatro

et al., 2007) who lack essential leadership skills (such as interpersonal or strategic skills) (Volz -Peacock, Carson & Marquardt, 2016)

and who are not well prepared to face today’s challenges. As Quatro et al. (2007, p. 435) posit, given that these rational programs

focus on the development of analytical capabilities, they are a “possible driver of the preponderance of analytically -focused leaders”

who have a limited understanding of leadership beyond analytical challenges. In sum, traditional classroom -based leadership

development programs are not considered to be effective means of developing leaders (Volz -Peacock et al., 2016; Day, 2000).

RETURN ON INVESTMENT

Leadership development is an important cost center for organizations, given the investment required in both money and

time (Cromwell & Kolb, 2004). According to Gurdjian, Halbeisen, and Lane (2014), every year, American organizations invest

almost $14 billion in leadership development programs. Chakrabarti (2009), leader of the People Analytics and Employee

Engagement research practices at Bersin by Deloitte, indicates that their recent survey of corporate America found that organizations

invested nearly $500,000 in 2009 on leadership development, which ranged from $170,000 to nearly $1.3 million depending on

organizational size. Aside from corporate-based leadership development programs, such programs are available in universities,

colleges and business schools, but they tend to be costly (Volz-Peacock & al., 2016). For example, the cost of developing a leader in

a customized program in a top business school can be as much as $150,000 (Gurdjian et al., 2014).

Organizations may not be receiving an adequate return on their investment in leadership development. Effective programs

show evidence of positive transfer of learning, which takes place when “learning in one context improves performance in some other

context” (Perkins, & Salomon, 1992, p. 3) or when “trainees effectively apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes gained in a

training context to the job” (Newstrom, 1986 cited in Cromwell & Kolb, 2004, p. 450). For example, there is positive transfer of

learning in leadership development programs when participants apply new skills and competencies gained in the program in their

leadership practices in the workplace. These new competencies should be demonstrated and widespread in the work context for a

substantial period of time in order to affirm that positive transfer has occurred (Baldwin & Ford, 1988). However, traditional

classroom-based leadership development programs account for less than 10 % of managers’ development (Robinson &Wick, 1992).

A recent survey of corporate America found weaknesses in leadership skills at every level of most organizations in the study

(Chakrabarti, 2009). Moreover, participants tend to remember about 10 % of what is said in lectures (Gurdjian et al., 2014),

suggesting that traditional programs lack transferability (Day, 2000).

Regrettably, neither positive transfer nor performance improvement seem to materialize regularly after training programs

(Cromwell & Kolb, 2004). Lessons learned in a classroom context are not integrated firmly into participants’ knowledge and skill

base: “Soon after the course ends, people slip back into their previous behavioral patterns, and little lasting change or developmental

progress is achieved” (Day, 2000, p. 601). Accordingly, in their research, Hirst, Mann, Bain, Pirola-Merlo, & Richver (2004, p. 311)

found that there was “a lag between learning leadership skills and translating these skills into leadership behavior.” These researchers

posited that this delay was likely caused by the difficulty involved in translating learned skills and behaviors into practice. These

Page 71 - Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, Volume 45, 2018

transferability issues may also be due to other factors: (a) the classroom context is limited compared to the real challenges and issues

participants will encounter in real life; (b) lessons learned as part of formal training are not usable/applicable in participants’ daily

lives; (c) classroom-based development expects students “to extrapolate from generic theories the specific ideas that address

workplace problems” (Brotheridge & Long, 2007, p. 839); or the organizational culture may not support the new techniques and

practices learned as part of the training process. There are many possible explanations, but what is certain is that traditional training

does not entirely fulfill its promises.

LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT THROUGH ACTION LEARNING

LEARNING OUTSIDE THE CLASSROOM

As Fulmer (1997) suggests, the paradigm of leadership development is evolving. Whereas leadership development was

previously carried out on university campuses or in corporate meeting rooms, the new approach is to develop leadership through

action regardless of the location chosen to do so (Fulmer, 1997). ‘Real’ leadership development occurs in daily experiences –

whether in one’s professional or personal life (Day et al., 2014; McCall, 2004; 2010; Robinson & Wick, 1992). Real environments

provide a rich context in which to explore and develop fundamental leadership capabilities (Mumford, Marks, Connelly, Zaccaro, &

Reiter-Palmon, 2000).

Learning outside the classroom setting means doing experiments in real, non-simulated situations. While classroom-based

leadership development tends to be concentrated over a certain period of time (Amagoh, 2009) and in specific locations, experience -

based leadership development is endless (Myatt, 2012) and can take place everywhere (Day, 2000). Unlike the classroom context

that is limited, learning outside the classroom is vast and permits individuals to position themselves as active experimenters instead

of as listeners or students (Fulmer, 1997).

As a result, individuals take responsibility for and participate actively in their development. For example, being involved in

a problem-solving process can help individuals acquire new skills. Since these skills are acquired through practice and in the context

in which they will be used, they are more likely to be translated into actual leadership behaviors (Hirst et al., 2004). However, there

is a caveat: an individual must want to learn from his or her experiences since learning from one's experiences is not necessarily

something that individuals naturally do (McCall, 2004). Moreover, time is required to change behavioral patterns and develop new

skills (Mumford et al., 2000). Translating and integrating knowledge into new leadership behaviors is not instantaneous (Hirst et al.,

2004). Given the foregoing, it appears that action learning may be a possible solution to the ineffectiveness of traditional leadership

development programs (Amagoh, 2009; Volz-Peacock et al., 2016).

ACTION LEARNING

Action learning is based on the assumption that “there can be no action without learning, and no learning without

action” (Revans, 2011, p. 11) in the same manner that learning from actions cannot happen without reflection (Brockbank & McGill,

2004). It involves “learning by doing” (Revans, 2016: p. 5), and it means “learning from tackling significant problems in the real

world through cycles of new action and reflection in the good company of those who can help to explore emergent issues with fresh

questions” (Simpson & Bourner, 2007, p. 184). There are four fundamental components of action learning: (a) real problems (not

simulated or invented ones, nor realistic case studies), (b) exploration occurring in the real world (not in a classroom/conference

room setting), (c) a learning process that is nested within action (i.e., learning does not occur before actions are taken), and (d) peers

acting as coaches or mentors in the learning process (in contrast to limited interactions in traditional learning settings).

The foregoing suggests that classroom-based programs and action learning may be “two opposite ends of the learning

spectrum” (Morrison, Rha, & Helfman, 2003, p. 16). Whereas the former permits individuals to acquire knowledge about leadership,

the latter permits them to develop skills in the context in which they are used. Action learning consists of learning from one’s

experiences rather than in the classroom (Smith, 2001). The traditional sequence for acquiring leadership skills (theory first, then

application and practice) is turned upside down and enriched with action learning. Real life experiences become the teacher, lessons

learned become theories, and experiences replace studying. While traditional leadership development employs a deductive approach

(applying theories to challenges), action learning favors an inductive approach (learning from experiences to develop lessons)

combined with a deductive approach for acquiring knowledge (applying theories to the workplace to make them tacit; Ralin, 1997).

From this perspective, action learning provides a “mix of practice-field experience using real issues, combined with a drawing-down

of theory where appropriate” (Smith, 2001, p. 36).

Concretely, individuals involved in action learning address a problem by asking themselves deep questions that lead them to

choose the actions to be asked, to observe, to think and to draw lessons from their experience (Simpson & Bourner, 2007) in order to

apply them later (Smith, 2001). The problem is usually taken from the participant’s workplace (Scott, 2017) and discussed with other

individuals to gain different perspectives (Ralin, 1997). The action learning process is undertaken in the real work setting, but still

provides an environment that is safe and favorable to learning (Smith, 2001).

In order to be effective, organizations need to apply action learning appropriately. Based on Conger and Toegel (2002) and

Marquardt (2006), the following conditions for success should be respected: (a) Action learning needs to be implemented more than

one time, even on a continual basis to develop, confirm and integrate new knowledge; (b) Problems analysed in the action learning

process must be explicitly connected to the subject matter being learned (for example, leadership); (c) Reflections should be

transferability issues may also be due to other factors: (a) the classroom context is limited compared to the real challenges and issues

participants will encounter in real life; (b) lessons learned as part of formal training are not usable/applicable in participants’ daily

lives; (c) classroom-based development expects students “to extrapolate from generic theories the specific ideas that address

workplace problems” (Brotheridge & Long, 2007, p. 839); or the organizational culture may not support the new techniques and

practices learned as part of the training process. There are many possible explanations, but what is certain is that traditional training

does not entirely fulfill its promises.

LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT THROUGH ACTION LEARNING

LEARNING OUTSIDE THE CLASSROOM

As Fulmer (1997) suggests, the paradigm of leadership development is evolving. Whereas leadership development was

previously carried out on university campuses or in corporate meeting rooms, the new approach is to develop leadership through

action regardless of the location chosen to do so (Fulmer, 1997). ‘Real’ leadership development occurs in daily experiences –

whether in one’s professional or personal life (Day et al., 2014; McCall, 2004; 2010; Robinson & Wick, 1992). Real environments

provide a rich context in which to explore and develop fundamental leadership capabilities (Mumford, Marks, Connelly, Zaccaro, &

Reiter-Palmon, 2000).

Learning outside the classroom setting means doing experiments in real, non-simulated situations. While classroom-based

leadership development tends to be concentrated over a certain period of time (Amagoh, 2009) and in specific locations, experience -

based leadership development is endless (Myatt, 2012) and can take place everywhere (Day, 2000). Unlike the classroom context

that is limited, learning outside the classroom is vast and permits individuals to position themselves as active experimenters instead

of as listeners or students (Fulmer, 1997).

As a result, individuals take responsibility for and participate actively in their development. For example, being involved in

a problem-solving process can help individuals acquire new skills. Since these skills are acquired through practice and in the context

in which they will be used, they are more likely to be translated into actual leadership behaviors (Hirst et al., 2004). However, there

is a caveat: an individual must want to learn from his or her experiences since learning from one's experiences is not necessarily

something that individuals naturally do (McCall, 2004). Moreover, time is required to change behavioral patterns and develop new

skills (Mumford et al., 2000). Translating and integrating knowledge into new leadership behaviors is not instantaneous (Hirst et al.,

2004). Given the foregoing, it appears that action learning may be a possible solution to the ineffectiveness of traditional leadership

development programs (Amagoh, 2009; Volz-Peacock et al., 2016).

ACTION LEARNING

Action learning is based on the assumption that “there can be no action without learning, and no learning without

action” (Revans, 2011, p. 11) in the same manner that learning from actions cannot happen without reflection (Brockbank & McGill,

2004). It involves “learning by doing” (Revans, 2016: p. 5), and it means “learning from tackling significant problems in the real

world through cycles of new action and reflection in the good company of those who can help to explore emergent issues with fresh

questions” (Simpson & Bourner, 2007, p. 184). There are four fundamental components of action learning: (a) real problems (not

simulated or invented ones, nor realistic case studies), (b) exploration occurring in the real world (not in a classroom/conference

room setting), (c) a learning process that is nested within action (i.e., learning does not occur before actions are taken), and (d) peers

acting as coaches or mentors in the learning process (in contrast to limited interactions in traditional learning settings).

The foregoing suggests that classroom-based programs and action learning may be “two opposite ends of the learning

spectrum” (Morrison, Rha, & Helfman, 2003, p. 16). Whereas the former permits individuals to acquire knowledge about leadership,

the latter permits them to develop skills in the context in which they are used. Action learning consists of learning from one’s

experiences rather than in the classroom (Smith, 2001). The traditional sequence for acquiring leadership skills (theory first, then

application and practice) is turned upside down and enriched with action learning. Real life experiences become the teacher, lessons

learned become theories, and experiences replace studying. While traditional leadership development employs a deductive approach

(applying theories to challenges), action learning favors an inductive approach (learning from experiences to develop lessons)

combined with a deductive approach for acquiring knowledge (applying theories to the workplace to make them tacit; Ralin, 1997).

From this perspective, action learning provides a “mix of practice-field experience using real issues, combined with a drawing-down

of theory where appropriate” (Smith, 2001, p. 36).

Concretely, individuals involved in action learning address a problem by asking themselves deep questions that lead them to

choose the actions to be asked, to observe, to think and to draw lessons from their experience (Simpson & Bourner, 2007) in order to

apply them later (Smith, 2001). The problem is usually taken from the participant’s workplace (Scott, 2017) and discussed with other

individuals to gain different perspectives (Ralin, 1997). The action learning process is undertaken in the real work setting, but still

provides an environment that is safe and favorable to learning (Smith, 2001).

In order to be effective, organizations need to apply action learning appropriately. Based on Conger and Toegel (2002) and

Marquardt (2006), the following conditions for success should be respected: (a) Action learning needs to be implemented more than

one time, even on a continual basis to develop, confirm and integrate new knowledge; (b) Problems analysed in the action learning

process must be explicitly connected to the subject matter being learned (for example, leadership); (c) Reflections should be

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Page 72 - Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, Volume 45, 2018

undertaken in sufficient number and at the appropriate moments during the action -learning process; (d) Teams must be created with

care to promote good internal dynamics; and (e) At the end of the program, care should be taken to ensure that learning is applied in

the workplace, for example through action plans. These conditions parallel those identified by Marquardt (2006: p.4): “1) an action

learning group or a team; 2) a project, problem or task; 3) a questioning and reflection process; 4) a commitment to action; 5) a

commitment to learning and 6) a group facilitator.”

ACTION LEARNING APPLIED TO LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

Leadership development is increasingly taking place by means of action learning (Conger & Toegel, 2002; Marquardt,

2000; Skipton Leonard & Lang, 2010). Because action learning proposes experiences that fit easily in the course of one’s work, it

increases the added value of these experiences (Hernez-Broome & Hughes, 2004). Moreover, developing leaders through action

learning allows leaders to: (a) develop complex competencies in their own unique and natural context while collaborating with

others; (b) apply their skills to the real world while gaining feedback; and (c) to develop their skills rather quickly without the

investment involved in developing an extensive implementation process (Conger & Toegel, 2002; Smith, 2001; Volz -Peacock et al.

2016). Action learning initiates individuals to the importance of “continually asking questions, gathering information, and analyzing

the situation” (Marquardt, 2000, p. 236). Individuals can practice their new skills, receive feedback (Volz-Peacock & al., 2016) and

know rapidly how well they are doing.

From an organizational perspective, an action learning approach to leadership development results in numerous benefits.

Action learning produces concrete outcomes since individuals complete tasks during the development process (Conger & Toegel,

2002) such as tackling actual organizational problems (Skipton Leonard & Lang, 2010) and finding innovative solutions (Volz -

Peacock et al., 2016). The skills that they learn are more easily transferred to their real work setting (Volz -Peacock et al., 2016) and

integrated into their competencies. Finally, the flexibility of such programs allows both individuals and organizations to adapt to

organizational challenges and priorities (Marquardt, 2000) because participants can choose the skills to be developed (Skipton

Leonard & Lang, 2010).

Many employers in various countries have used an action learning approach to develop and maintain their leadership capital

(Marquardt, 2000). General Electric’s (GE) leadership program serves as a good example of how action learning has been applied to

leadership development (Marquardt, 2000). GE used to develop leaders via traditional programs including activities and lectures on

diverse themes related to leadership. Due to their lack of impact, GE implemented an action learning program to involve participants

in real organizational challenges and to facilitate participation, team work and the development of useful skills. More specifically,

“Action learning teams are built around GE problems that are real, relevant, and require decisions. Formats may vary, but typically,

two teams of five to seven people who come from diverse businesses and functions within GE work together on the

problem” (Marquardt, 2000, p. 239). Similarly, the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) leadership development program (Skipton

Leonard & Lang, 2010) employed the following learning approach: acquisition of certain basic knowledge, implementation of action

learning projects, and application of the skills developed within the framework of these projects. Their program showed strong

results, and program participants considered it to be central to their development as leaders.

101 LEADERSHP EXERCISES

Leadership development by means of action learning is not restricted to organizational settings; action learning can also be

the foundation of university-based leadership courses. This section describes how we applied an action learning perspective in

undergraduate leadership courses. With few exceptions, the students were business majors who were working either part-time or full-

time while taking university courses.

PHILOSOPHY AND OBJECTIVES

After almost 20 years of offering leadership courses in an experiential manner and developing those exercises into

experiences that were applied in students’ personal or professional lives, the first author realized that the transformative ability of the

exercises resided in their integration in students’ ‘real life’ situations. In other words, what were initially primarily in -class exercises

evolved into practical experiences that embraced action learning. By assembling the exercises into a practical workbook (Grimard &

Pellerin, 2017), we hope to promote action learning as an ongoing practice among students and others interested in developing their

leadership.

The philosophy behind 101 Exercises for Developing your Leadership is as follows:

It is by practicing leadership that one becomes a leader. Leadership is developed by doing it. It isn’t sufficient,

effective, or even desirable to stockpile tons of leadership theories without testing or practicing them. It is through

experimentation that you can develop a good knowledge of your strengths and weaknesses as a leader and shape

your own way of thinking about leadership. If, indeed, "it's by riding a bike that you learn how to ride a bike,” then

it’s by practicing leadership that you become a leader. And, just like learning to ride a bike, learning to lead is an

incremental process. If you take small steps, you will see your confidence in yourself as a leader grow. Leadership

theories are useful; they can guide your thinking and understanding about the leadership process. However,

ingesting tons of theories about leadership without testing or using them will not make you a leader. It is through

experimentation that you discover your own way of being a leader (Grimard & Pellerin, 2017, p. 4).

undertaken in sufficient number and at the appropriate moments during the action -learning process; (d) Teams must be created with

care to promote good internal dynamics; and (e) At the end of the program, care should be taken to ensure that learning is applied in

the workplace, for example through action plans. These conditions parallel those identified by Marquardt (2006: p.4): “1) an action

learning group or a team; 2) a project, problem or task; 3) a questioning and reflection process; 4) a commitment to action; 5) a

commitment to learning and 6) a group facilitator.”

ACTION LEARNING APPLIED TO LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

Leadership development is increasingly taking place by means of action learning (Conger & Toegel, 2002; Marquardt,

2000; Skipton Leonard & Lang, 2010). Because action learning proposes experiences that fit easily in the course of one’s work, it

increases the added value of these experiences (Hernez-Broome & Hughes, 2004). Moreover, developing leaders through action

learning allows leaders to: (a) develop complex competencies in their own unique and natural context while collaborating with

others; (b) apply their skills to the real world while gaining feedback; and (c) to develop their skills rather quickly without the

investment involved in developing an extensive implementation process (Conger & Toegel, 2002; Smith, 2001; Volz -Peacock et al.

2016). Action learning initiates individuals to the importance of “continually asking questions, gathering information, and analyzing

the situation” (Marquardt, 2000, p. 236). Individuals can practice their new skills, receive feedback (Volz-Peacock & al., 2016) and

know rapidly how well they are doing.

From an organizational perspective, an action learning approach to leadership development results in numerous benefits.

Action learning produces concrete outcomes since individuals complete tasks during the development process (Conger & Toegel,

2002) such as tackling actual organizational problems (Skipton Leonard & Lang, 2010) and finding innovative solutions (Volz -

Peacock et al., 2016). The skills that they learn are more easily transferred to their real work setting (Volz -Peacock et al., 2016) and

integrated into their competencies. Finally, the flexibility of such programs allows both individuals and organizations to adapt to

organizational challenges and priorities (Marquardt, 2000) because participants can choose the skills to be developed (Skipton

Leonard & Lang, 2010).

Many employers in various countries have used an action learning approach to develop and maintain their leadership capital

(Marquardt, 2000). General Electric’s (GE) leadership program serves as a good example of how action learning has been applied to

leadership development (Marquardt, 2000). GE used to develop leaders via traditional programs including activities and lectures on

diverse themes related to leadership. Due to their lack of impact, GE implemented an action learning program to involve participants

in real organizational challenges and to facilitate participation, team work and the development of useful skills. More specifically,

“Action learning teams are built around GE problems that are real, relevant, and require decisions. Formats may vary, but typically,

two teams of five to seven people who come from diverse businesses and functions within GE work together on the

problem” (Marquardt, 2000, p. 239). Similarly, the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) leadership development program (Skipton

Leonard & Lang, 2010) employed the following learning approach: acquisition of certain basic knowledge, implementation of action

learning projects, and application of the skills developed within the framework of these projects. Their program showed strong

results, and program participants considered it to be central to their development as leaders.

101 LEADERSHP EXERCISES

Leadership development by means of action learning is not restricted to organizational settings; action learning can also be

the foundation of university-based leadership courses. This section describes how we applied an action learning perspective in

undergraduate leadership courses. With few exceptions, the students were business majors who were working either part-time or full-

time while taking university courses.

PHILOSOPHY AND OBJECTIVES

After almost 20 years of offering leadership courses in an experiential manner and developing those exercises into

experiences that were applied in students’ personal or professional lives, the first author realized that the transformative ability of the

exercises resided in their integration in students’ ‘real life’ situations. In other words, what were initially primarily in -class exercises

evolved into practical experiences that embraced action learning. By assembling the exercises into a practical workbook (Grimard &

Pellerin, 2017), we hope to promote action learning as an ongoing practice among students and others interested in developing their

leadership.

The philosophy behind 101 Exercises for Developing your Leadership is as follows:

It is by practicing leadership that one becomes a leader. Leadership is developed by doing it. It isn’t sufficient,

effective, or even desirable to stockpile tons of leadership theories without testing or practicing them. It is through

experimentation that you can develop a good knowledge of your strengths and weaknesses as a leader and shape

your own way of thinking about leadership. If, indeed, "it's by riding a bike that you learn how to ride a bike,” then

it’s by practicing leadership that you become a leader. And, just like learning to ride a bike, learning to lead is an

incremental process. If you take small steps, you will see your confidence in yourself as a leader grow. Leadership

theories are useful; they can guide your thinking and understanding about the leadership process. However,

ingesting tons of theories about leadership without testing or using them will not make you a leader. It is through

experimentation that you discover your own way of being a leader (Grimard & Pellerin, 2017, p. 4).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Page 73 - Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, Volume 45, 2018

The leadership course, based on this book, was designed to help students understand and develop their leadership skills. At

the end of the course, the student should be able to: (a) draw a realistic picture of their strengths and vulnerabilities as leaders; (b) be

aware of patterns of behavior that promote or impede leadership; and (c) identify and undertake avenues for action in developing

their personal leadership.

OVERALL APPROACH

“For learning to occur, there has to be some kind of change in the learner. No change, no learning. And significant

learning requires that there be some kind of lasting change that is important in terms of the learner’s life” (Fink,

2013, p. 30).

Consistent with an action learning approach (Marquardt, 2006), the exercises involve students in ‘embedded learning’ in the

context in which leadership takes place (rather than being centered in the classroom). The exercises invite individuals to: (a)

undertake ‘real’ challenges in their personal or professional lives as a means of developing particular leadership skills; (b) reflect on

those experiences and distill the key lessons and insights that they have learned; (c) develop and implement an action plan (based on

what they learned) that will enable them to become more effective leaders; (d) keep a record of their actions and progress in a

learning journal; and (e) involve others in their learning, for example, as a member of their feedback team. Individuals are required to

undertake the exercises, not simply read their description in the book. The professor’s role becomes that of a guide, a coach, or an

additional source of feedback rather than that of a lecturer. In this manner, the experiential learning cycle is applied in an innovative

way. Students’ experiences/challenges occur in the ‘real world’ rather than in a classroom setting. The exercises guide them through

the experiential learning cycle, and class time is invested in assisting students in their passage through this cycle; for example,

removing potential road blocks, clarifying and deepening learning, and challenging students to develop action plans that will

transform their leadership skills.

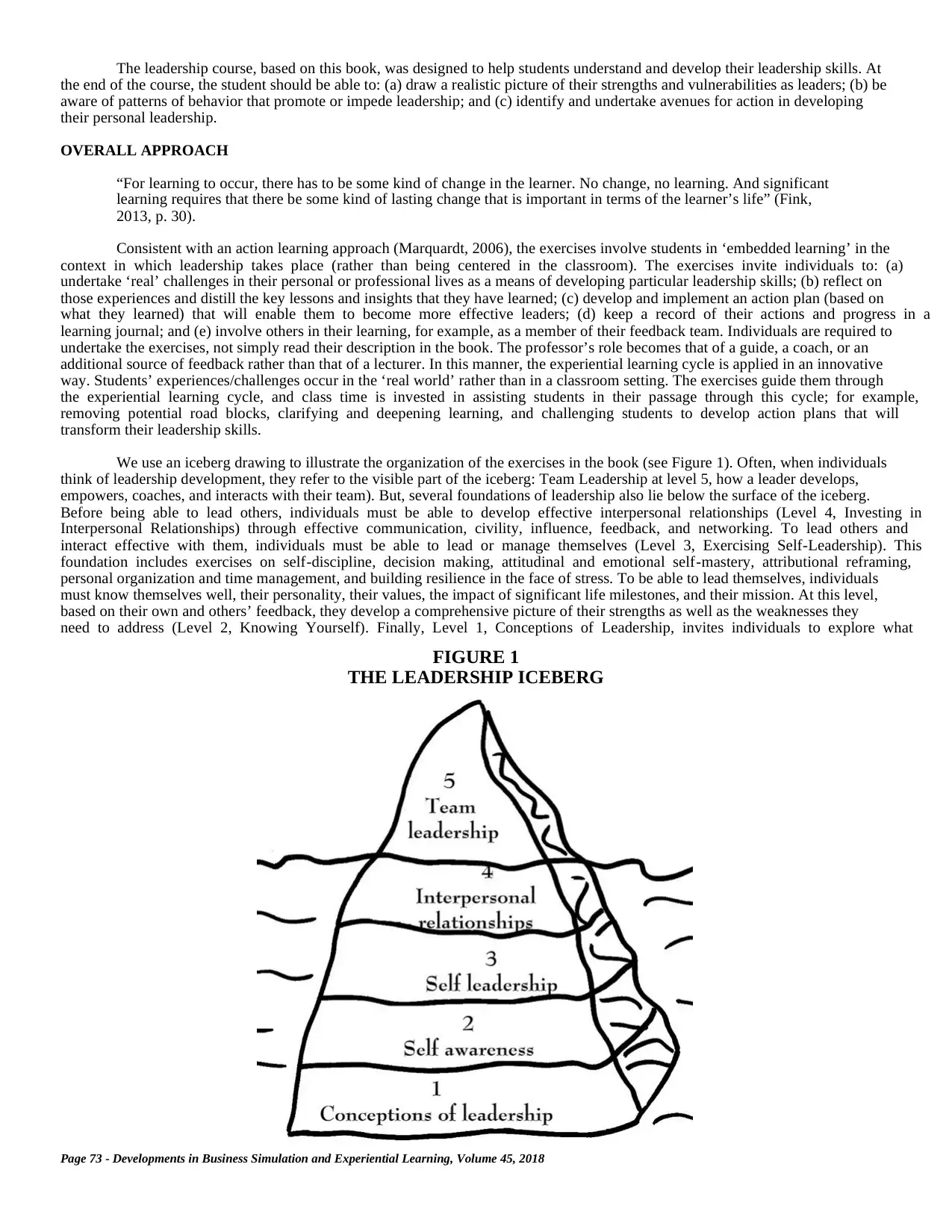

We use an iceberg drawing to illustrate the organization of the exercises in the book (see Figure 1). Often, when individuals

think of leadership development, they refer to the visible part of the iceberg: Team Leadership at level 5, how a leader develops,

empowers, coaches, and interacts with their team). But, several foundations of leadership also lie below the surface of the iceberg.

Before being able to lead others, individuals must be able to develop effective interpersonal relationships (Level 4, Investing in

Interpersonal Relationships) through effective communication, civility, influence, feedback, and networking. To lead others and

interact effective with them, individuals must be able to lead or manage themselves (Level 3, Exercising Self-Leadership). This

foundation includes exercises on self-discipline, decision making, attitudinal and emotional self-mastery, attributional reframing,

personal organization and time management, and building resilience in the face of stress. To be able to lead themselves, individuals

must know themselves well, their personality, their values, the impact of significant life milestones, and their mission. At this level,

based on their own and others’ feedback, they develop a comprehensive picture of their strengths as well as the weaknesses they

need to address (Level 2, Knowing Yourself). Finally, Level 1, Conceptions of Leadership, invites individuals to explore what

FIGURE 1

THE LEADERSHIP ICEBERG

The leadership course, based on this book, was designed to help students understand and develop their leadership skills. At

the end of the course, the student should be able to: (a) draw a realistic picture of their strengths and vulnerabilities as leaders; (b) be

aware of patterns of behavior that promote or impede leadership; and (c) identify and undertake avenues for action in developing

their personal leadership.

OVERALL APPROACH

“For learning to occur, there has to be some kind of change in the learner. No change, no learning. And significant

learning requires that there be some kind of lasting change that is important in terms of the learner’s life” (Fink,

2013, p. 30).

Consistent with an action learning approach (Marquardt, 2006), the exercises involve students in ‘embedded learning’ in the

context in which leadership takes place (rather than being centered in the classroom). The exercises invite individuals to: (a)

undertake ‘real’ challenges in their personal or professional lives as a means of developing particular leadership skills; (b) reflect on

those experiences and distill the key lessons and insights that they have learned; (c) develop and implement an action plan (based on

what they learned) that will enable them to become more effective leaders; (d) keep a record of their actions and progress in a

learning journal; and (e) involve others in their learning, for example, as a member of their feedback team. Individuals are required to

undertake the exercises, not simply read their description in the book. The professor’s role becomes that of a guide, a coach, or an

additional source of feedback rather than that of a lecturer. In this manner, the experiential learning cycle is applied in an innovative

way. Students’ experiences/challenges occur in the ‘real world’ rather than in a classroom setting. The exercises guide them through

the experiential learning cycle, and class time is invested in assisting students in their passage through this cycle; for example,

removing potential road blocks, clarifying and deepening learning, and challenging students to develop action plans that will

transform their leadership skills.

We use an iceberg drawing to illustrate the organization of the exercises in the book (see Figure 1). Often, when individuals

think of leadership development, they refer to the visible part of the iceberg: Team Leadership at level 5, how a leader develops,

empowers, coaches, and interacts with their team). But, several foundations of leadership also lie below the surface of the iceberg.

Before being able to lead others, individuals must be able to develop effective interpersonal relationships (Level 4, Investing in

Interpersonal Relationships) through effective communication, civility, influence, feedback, and networking. To lead others and

interact effective with them, individuals must be able to lead or manage themselves (Level 3, Exercising Self-Leadership). This

foundation includes exercises on self-discipline, decision making, attitudinal and emotional self-mastery, attributional reframing,

personal organization and time management, and building resilience in the face of stress. To be able to lead themselves, individuals

must know themselves well, their personality, their values, the impact of significant life milestones, and their mission. At this level,

based on their own and others’ feedback, they develop a comprehensive picture of their strengths as well as the weaknesses they

need to address (Level 2, Knowing Yourself). Finally, Level 1, Conceptions of Leadership, invites individuals to explore what

FIGURE 1

THE LEADERSHIP ICEBERG

Page 74 - Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, Volume 45, 2018

leadership means to them, particularly the impact of their past experiences on their current understanding of leadership. Although

there is some overlap in the foundations, individuals are encouraged to start at Level 1 and move up to Level 5. The final section of

the book, The Grand Finale, provides individuals with exercises and case studies for integrating their learning. For example, one

exercise invites students to identify the top 10 lessons that they have learned about leadership during their learning journal. Another

exercise invites students to examine the biography of their favorite leader through the lens of the five levels of the iceberg.

LEARNING PROCESS

At the core of the learning process are the 101 exercises presented in the book. When students undertake these exercises,

they take actions to develop their leadership, develop good habits and learn more about their own strengths and weaknesses. Each

exercise presents them with challenges, reflection questions, and the opportunity to develop an action plan. Students are expected to

keep a detailed record of all that they have experienced and learned in their learning journals. For each exercise, they must keep track

of what they have done and learned and what they will do in the future (their challenges, thoughts and action plans) in a learning

journal. They are also asked to create a feedback group comprised of five or six students who are also taking the course.

Each foundation and The Grand Finale are addressed in a period of approximately two weeks, for a total of approximately

12 weeks. Given the time constraints of a regular semester, not all 101 of the exercises presented in the book are undertaken.

Students are asked to undertake a specific number of exercises, including some required exercises. For example, for Foundation 2,

Building Self-Awareness, students undertake two required exercises in week 1 relating to developing one’s personality and seeking

feedback and two exercises of their choice in week 2. After students complete their journal entries for the exercises that they’ve

undertaken, they upload their report for the foundation (the journal entries) to the online instructional platform (for example,

Moodle) the evening prior to the class in which they are to be discussed. This demonstrates that students have completed the

exercises and are able to contribute to the class discussion pertaining to the exercises. Points are not attributed to the reports

submitted before the course since they are "draft" versions of those submitted in final form later on in the semester. A penalty of 1%

is attributed (on the final grade) for each exercise report that is not submitted to the online instructional platform before 11 pm the

day before each session. Late reports are not accepted. Additionally, randomly selected reports are spot checked for quality.

‘Superficial’ reports (those showing that very little learning has taken place) do not constitute adequate preparation. In other words,

they are considered equivalent to not submitting a report at all (and, therefore, a 1% penalty is applied).

During class on the following day, students assemble in their feedback groups to share what they have done and learned in

doing the exercises. For every class, the formal leadership of the team is rotated so that all team members have a chance to lead the

team discussion. Each student shares their report and receives feedback from the members of their team. After each student has had

this opportunity, the team prepares a list of lessons and insights that they have derived from the exercises. This team discussion

generally takes about an hour of class time. The instructor then facilitates the presentation and discussion of these team reports,

weaving in additional insights where appropriate. These class discussions help students to reflect upon, revise and improve upon

what they have written in their learning journal. For each foundation, students are expected to revise their reports and submit the

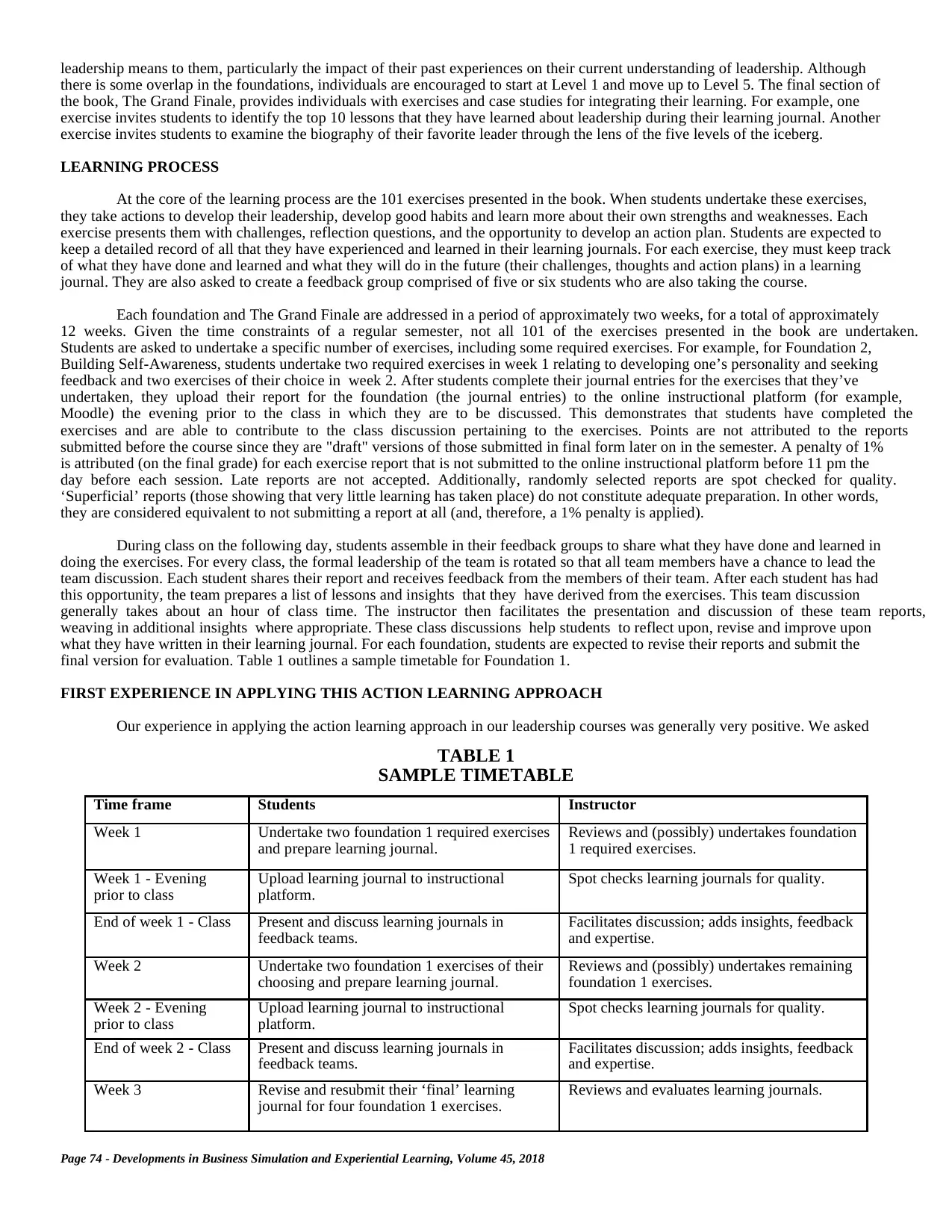

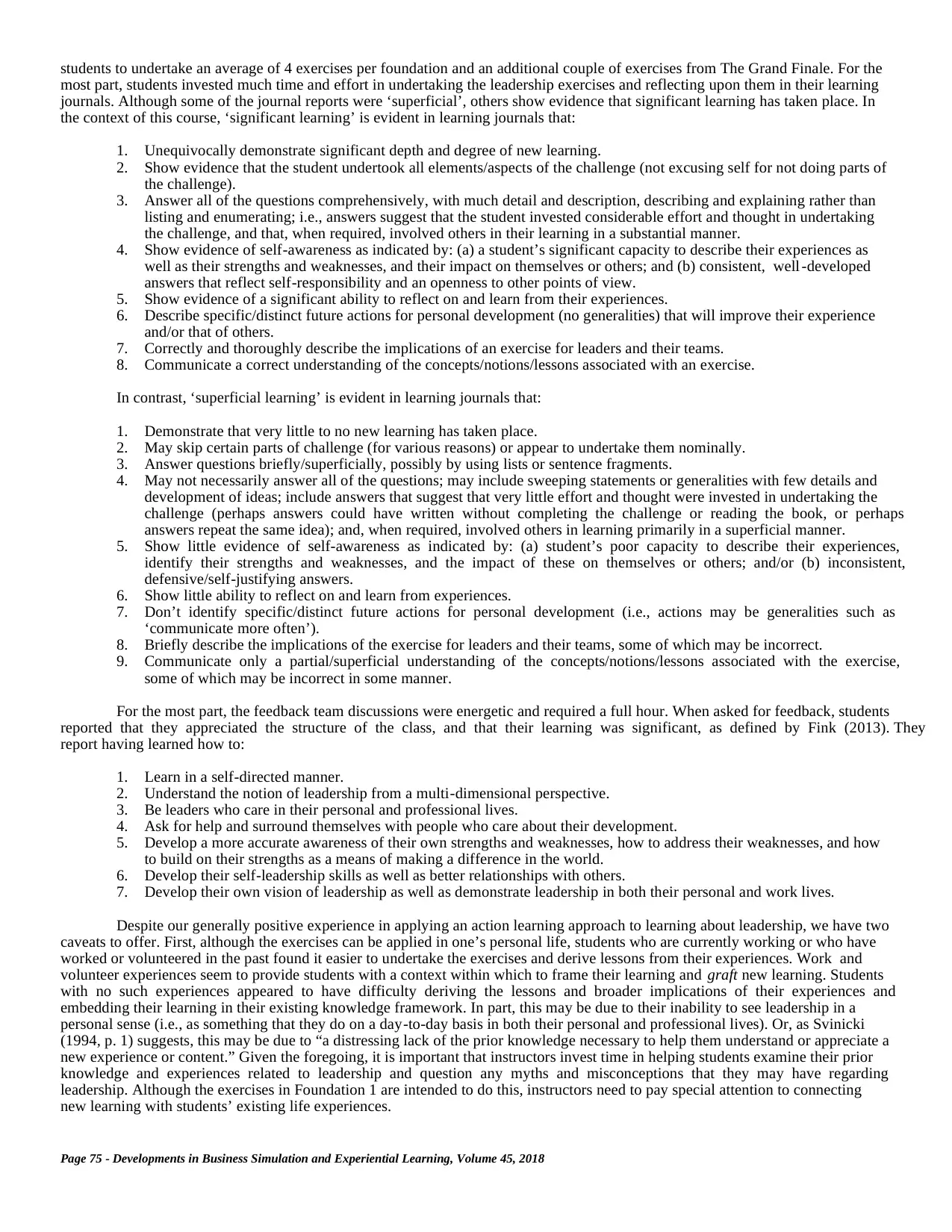

final version for evaluation. Table 1 outlines a sample timetable for Foundation 1.

FIRST EXPERIENCE IN APPLYING THIS ACTION LEARNING APPROACH

Our experience in applying the action learning approach in our leadership courses was generally very positive. We asked

TABLE 1

SAMPLE TIMETABLE

Time frame Students Instructor

Week 1 Undertake two foundation 1 required exercises

and prepare learning journal.

Reviews and (possibly) undertakes foundation

1 required exercises.

Week 1 - Evening

prior to class

Upload learning journal to instructional

platform.

Spot checks learning journals for quality.

End of week 1 - Class Present and discuss learning journals in

feedback teams.

Facilitates discussion; adds insights, feedback

and expertise.

Week 2 Undertake two foundation 1 exercises of their

choosing and prepare learning journal.

Reviews and (possibly) undertakes remaining

foundation 1 exercises.

Week 2 - Evening

prior to class

Upload learning journal to instructional

platform.

Spot checks learning journals for quality.

End of week 2 - Class Present and discuss learning journals in

feedback teams.

Facilitates discussion; adds insights, feedback

and expertise.

Week 3 Revise and resubmit their ‘final’ learning

journal for four foundation 1 exercises.

Reviews and evaluates learning journals.

leadership means to them, particularly the impact of their past experiences on their current understanding of leadership. Although

there is some overlap in the foundations, individuals are encouraged to start at Level 1 and move up to Level 5. The final section of

the book, The Grand Finale, provides individuals with exercises and case studies for integrating their learning. For example, one

exercise invites students to identify the top 10 lessons that they have learned about leadership during their learning journal. Another

exercise invites students to examine the biography of their favorite leader through the lens of the five levels of the iceberg.

LEARNING PROCESS

At the core of the learning process are the 101 exercises presented in the book. When students undertake these exercises,

they take actions to develop their leadership, develop good habits and learn more about their own strengths and weaknesses. Each

exercise presents them with challenges, reflection questions, and the opportunity to develop an action plan. Students are expected to

keep a detailed record of all that they have experienced and learned in their learning journals. For each exercise, they must keep track

of what they have done and learned and what they will do in the future (their challenges, thoughts and action plans) in a learning

journal. They are also asked to create a feedback group comprised of five or six students who are also taking the course.

Each foundation and The Grand Finale are addressed in a period of approximately two weeks, for a total of approximately

12 weeks. Given the time constraints of a regular semester, not all 101 of the exercises presented in the book are undertaken.

Students are asked to undertake a specific number of exercises, including some required exercises. For example, for Foundation 2,

Building Self-Awareness, students undertake two required exercises in week 1 relating to developing one’s personality and seeking

feedback and two exercises of their choice in week 2. After students complete their journal entries for the exercises that they’ve

undertaken, they upload their report for the foundation (the journal entries) to the online instructional platform (for example,

Moodle) the evening prior to the class in which they are to be discussed. This demonstrates that students have completed the

exercises and are able to contribute to the class discussion pertaining to the exercises. Points are not attributed to the reports

submitted before the course since they are "draft" versions of those submitted in final form later on in the semester. A penalty of 1%

is attributed (on the final grade) for each exercise report that is not submitted to the online instructional platform before 11 pm the

day before each session. Late reports are not accepted. Additionally, randomly selected reports are spot checked for quality.

‘Superficial’ reports (those showing that very little learning has taken place) do not constitute adequate preparation. In other words,

they are considered equivalent to not submitting a report at all (and, therefore, a 1% penalty is applied).

During class on the following day, students assemble in their feedback groups to share what they have done and learned in

doing the exercises. For every class, the formal leadership of the team is rotated so that all team members have a chance to lead the

team discussion. Each student shares their report and receives feedback from the members of their team. After each student has had

this opportunity, the team prepares a list of lessons and insights that they have derived from the exercises. This team discussion

generally takes about an hour of class time. The instructor then facilitates the presentation and discussion of these team reports,

weaving in additional insights where appropriate. These class discussions help students to reflect upon, revise and improve upon

what they have written in their learning journal. For each foundation, students are expected to revise their reports and submit the

final version for evaluation. Table 1 outlines a sample timetable for Foundation 1.

FIRST EXPERIENCE IN APPLYING THIS ACTION LEARNING APPROACH

Our experience in applying the action learning approach in our leadership courses was generally very positive. We asked

TABLE 1

SAMPLE TIMETABLE

Time frame Students Instructor

Week 1 Undertake two foundation 1 required exercises

and prepare learning journal.

Reviews and (possibly) undertakes foundation

1 required exercises.

Week 1 - Evening

prior to class

Upload learning journal to instructional

platform.

Spot checks learning journals for quality.

End of week 1 - Class Present and discuss learning journals in

feedback teams.

Facilitates discussion; adds insights, feedback

and expertise.

Week 2 Undertake two foundation 1 exercises of their

choosing and prepare learning journal.

Reviews and (possibly) undertakes remaining

foundation 1 exercises.

Week 2 - Evening

prior to class

Upload learning journal to instructional

platform.

Spot checks learning journals for quality.

End of week 2 - Class Present and discuss learning journals in

feedback teams.

Facilitates discussion; adds insights, feedback

and expertise.

Week 3 Revise and resubmit their ‘final’ learning

journal for four foundation 1 exercises.

Reviews and evaluates learning journals.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Page 75 - Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, Volume 45, 2018

students to undertake an average of 4 exercises per foundation and an additional couple of exercises from The Grand Finale. For the

most part, students invested much time and effort in undertaking the leadership exercises and reflecting upon them in their learning

journals. Although some of the journal reports were ‘superficial’, others show evidence that significant learning has taken place. In

the context of this course, ‘significant learning’ is evident in learning journals that:

1. Unequivocally demonstrate significant depth and degree of new learning.

2. Show evidence that the student undertook all elements/aspects of the challenge (not excusing self for not doing parts of

the challenge).

3. Answer all of the questions comprehensively, with much detail and description, describing and explaining rather than

listing and enumerating; i.e., answers suggest that the student invested considerable effort and thought in undertaking

the challenge, and that, when required, involved others in their learning in a substantial manner.

4. Show evidence of self-awareness as indicated by: (a) a student’s significant capacity to describe their experiences as

well as their strengths and weaknesses, and their impact on themselves or others; and (b) consistent, well -developed

answers that reflect self-responsibility and an openness to other points of view.

5. Show evidence of a significant ability to reflect on and learn from their experiences.

6. Describe specific/distinct future actions for personal development (no generalities) that will improve their experience

and/or that of others.

7. Correctly and thoroughly describe the implications of an exercise for leaders and their teams.

8. Communicate a correct understanding of the concepts/notions/lessons associated with an exercise.

In contrast, ‘superficial learning’ is evident in learning journals that:

1. Demonstrate that very little to no new learning has taken place.

2. May skip certain parts of challenge (for various reasons) or appear to undertake them nominally.

3. Answer questions briefly/superficially, possibly by using lists or sentence fragments.

4. May not necessarily answer all of the questions; may include sweeping statements or generalities with few details and

development of ideas; include answers that suggest that very little effort and thought were invested in undertaking the

challenge (perhaps answers could have written without completing the challenge or reading the book, or perhaps

answers repeat the same idea); and, when required, involved others in learning primarily in a superficial manner.

5. Show little evidence of self-awareness as indicated by: (a) student’s poor capacity to describe their experiences,

identify their strengths and weaknesses, and the impact of these on themselves or others; and/or (b) inconsistent,

defensive/self-justifying answers.

6. Show little ability to reflect on and learn from experiences.

7. Don’t identify specific/distinct future actions for personal development (i.e., actions may be generalities such as

‘communicate more often’).

8. Briefly describe the implications of the exercise for leaders and their teams, some of which may be incorrect.

9. Communicate only a partial/superficial understanding of the concepts/notions/lessons associated with the exercise,

some of which may be incorrect in some manner.

For the most part, the feedback team discussions were energetic and required a full hour. When asked for feedback, students

reported that they appreciated the structure of the class, and that their learning was significant, as defined by Fink (2013). They

report having learned how to:

1. Learn in a self-directed manner.

2. Understand the notion of leadership from a multi-dimensional perspective.

3. Be leaders who care in their personal and professional lives.

4. Ask for help and surround themselves with people who care about their development.

5. Develop a more accurate awareness of their own strengths and weaknesses, how to address their weaknesses, and how

to build on their strengths as a means of making a difference in the world.

6. Develop their self-leadership skills as well as better relationships with others.

7. Develop their own vision of leadership as well as demonstrate leadership in both their personal and work lives.

Despite our generally positive experience in applying an action learning approach to learning about leadership, we have two

caveats to offer. First, although the exercises can be applied in one’s personal life, students who are currently working or who have

worked or volunteered in the past found it easier to undertake the exercises and derive lessons from their experiences. Work and

volunteer experiences seem to provide students with a context within which to frame their learning and graft new learning. Students

with no such experiences appeared to have difficulty deriving the lessons and broader implications of their experiences and

embedding their learning in their existing knowledge framework. In part, this may be due to their inability to see leadership in a

personal sense (i.e., as something that they do on a day-to-day basis in both their personal and professional lives). Or, as Svinicki

(1994, p. 1) suggests, this may be due to “a distressing lack of the prior knowledge necessary to help them understand or appreciate a

new experience or content.” Given the foregoing, it is important that instructors invest time in helping students examine their prior

knowledge and experiences related to leadership and question any myths and misconceptions that they may have regarding

leadership. Although the exercises in Foundation 1 are intended to do this, instructors need to pay special attention to connecting

new learning with students’ existing life experiences.

students to undertake an average of 4 exercises per foundation and an additional couple of exercises from The Grand Finale. For the

most part, students invested much time and effort in undertaking the leadership exercises and reflecting upon them in their learning

journals. Although some of the journal reports were ‘superficial’, others show evidence that significant learning has taken place. In

the context of this course, ‘significant learning’ is evident in learning journals that:

1. Unequivocally demonstrate significant depth and degree of new learning.

2. Show evidence that the student undertook all elements/aspects of the challenge (not excusing self for not doing parts of

the challenge).

3. Answer all of the questions comprehensively, with much detail and description, describing and explaining rather than

listing and enumerating; i.e., answers suggest that the student invested considerable effort and thought in undertaking

the challenge, and that, when required, involved others in their learning in a substantial manner.

4. Show evidence of self-awareness as indicated by: (a) a student’s significant capacity to describe their experiences as

well as their strengths and weaknesses, and their impact on themselves or others; and (b) consistent, well -developed

answers that reflect self-responsibility and an openness to other points of view.

5. Show evidence of a significant ability to reflect on and learn from their experiences.

6. Describe specific/distinct future actions for personal development (no generalities) that will improve their experience

and/or that of others.

7. Correctly and thoroughly describe the implications of an exercise for leaders and their teams.

8. Communicate a correct understanding of the concepts/notions/lessons associated with an exercise.

In contrast, ‘superficial learning’ is evident in learning journals that:

1. Demonstrate that very little to no new learning has taken place.

2. May skip certain parts of challenge (for various reasons) or appear to undertake them nominally.

3. Answer questions briefly/superficially, possibly by using lists or sentence fragments.

4. May not necessarily answer all of the questions; may include sweeping statements or generalities with few details and