Deviance Crime And Social Control Assesment

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/12

|58

|23628

|26

AI Summary

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 1/58

Home Read Sign in

INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLOGY – 1ST CANADIAN EDITION

CONTENTS

Search in book…

Main Body

CHAPTER 7. DEVIANCE, CRIME, AND SOCIAL

CONTROL

Figure 7.1. Psychopaths and

sociopaths are some of the star

deviants in contemporary popular

culture. What makes them so

appealing asctional characters?Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 1/58

Home Read Sign in

INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLOGY – 1ST CANADIAN EDITION

CONTENTS

Search in book…

Main Body

CHAPTER 7. DEVIANCE, CRIME, AND SOCIAL

CONTROL

Figure 7.1. Psychopaths and

sociopaths are some of the star

deviants in contemporary popular

culture. What makes them so

appealing asctional characters?Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 2/58

(Photo courtesy of Christian

Weber/Flickr)

Learning Objectives

7.1. Deviance and Control

De ne deviance and categorize dierent types of deviant behaviour

Determine why certain behaviours are dened as deviant while others are not

Di erentiate between methods of social control

Describe the characteristics of disciplinary social control and their relationship

to normalizing societies

7.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance

Describe the functionalist view of deviance in society and compare Durkheim’

views with social disorganization theory, control theory, and strain theory

Explain how critical sociology understands deviance and crime in society

Understand feminist theory’s unique contributions to the critical perspective o

crime and deviance

Describe the symbolic interactionist approach to deviance, including labelling

and other theories

7.3. Crime and the Law

Identify and dierentiate between dierent types of crimes

Evaluate Canadian crime statistics

Understand the nature of the corrections system in Canada

INTRODUCTION TO DEVIANCE, CRIME, AN

SOCIAL CONTROL

Psychopaths and sociopaths are some of the favourite “deviants” in contemporary

popular culture. From Patrick Bateman inAmerican Psycho, to Dr. Hannibal Lecter in

The Silence of the Lambs, to Dexter Morgan inDexter, to Sherlock Holmes in

Sherlockand Elementary, the gure of the dangerous individual who lives among us

provides a fascinating ctional gure.Psychopathyand sociopathyboth refer to

personality disorders that involve anti-social behaviour, diminished empathy, and

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 2/58

(Photo courtesy of Christian

Weber/Flickr)

Learning Objectives

7.1. Deviance and Control

De ne deviance and categorize dierent types of deviant behaviour

Determine why certain behaviours are dened as deviant while others are not

Di erentiate between methods of social control

Describe the characteristics of disciplinary social control and their relationship

to normalizing societies

7.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance

Describe the functionalist view of deviance in society and compare Durkheim’

views with social disorganization theory, control theory, and strain theory

Explain how critical sociology understands deviance and crime in society

Understand feminist theory’s unique contributions to the critical perspective o

crime and deviance

Describe the symbolic interactionist approach to deviance, including labelling

and other theories

7.3. Crime and the Law

Identify and dierentiate between dierent types of crimes

Evaluate Canadian crime statistics

Understand the nature of the corrections system in Canada

INTRODUCTION TO DEVIANCE, CRIME, AN

SOCIAL CONTROL

Psychopaths and sociopaths are some of the favourite “deviants” in contemporary

popular culture. From Patrick Bateman inAmerican Psycho, to Dr. Hannibal Lecter in

The Silence of the Lambs, to Dexter Morgan inDexter, to Sherlock Holmes in

Sherlockand Elementary, the gure of the dangerous individual who lives among us

provides a fascinating ctional gure.Psychopathyand sociopathyboth refer to

personality disorders that involve anti-social behaviour, diminished empathy, and

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 3/58

of inhibitions. In clinical analysis, these analytical categories should be distinguish

from psychosis, which is a condition involving a debilitating break with reality.

Psychopaths and sociopaths are o en able to manage their condition and pass as

“normal” citizens, although their capacity for manipulation and cruelty can have

devastating consequences for people around them. The term psychopathy is o e

used to emphasize that the source of the disorder is internal, based on psychologi

biological, or genetic factors, whereas sociopathy is used to emphasize predomin

social factors in the disorder: the social or familial sources of its development and

inability to be social or abide by societal rules (Hare 1999). In this sense sociopath

would be the sociological disease par excellence. It entails an incapacity for

companionship (socius), yet many accounts of sociopaths describe them as being

charming, attractively con dent, and outgoing (Hare 1999).

In a modern society characterized by the predominance of secondary rather than

primary relationships, the sociopath or psychopath functions, in popular culture at

least, as a prime index of contemporary social unease. The sociopath is like the ni

neighbour next door who one day “goes o” or is revealed to have had a sinister

second life. In many ways the sociopath is a cypher for many of the anxieties we h

about the loss of community and living among people we do not know. In this sens

the sociopath is a very modern sort of deviant. Contemporary approaches to

psychopathy and sociopathy have focused on biological and genetic causes. This i

tradition that goes back to 19th century positivist approaches to deviance, which

attempted to nd a biological cause for criminality and other types of deviant

behaviour.

The Italian professor of legal psychiatry Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909) was a key

gure in positivist criminology who thought he had isolated specic physiological

characteristics of “degeneracy” that could distinguish “born criminals” from norma

individuals (Rimke 2011). In a much more sophisticated way, this was also the pre

of Dr. James Fallon, a neuroscientist at the University of California. His research

involved analyzing brain scans of serial killers. He found that areas of the frontal a

temporal lobes associated with empathy, morality, and self-control are “shut o” in

serial killers. In turn, this lack of brain activity has been linked with specic genetic

markers suggesting that psychopathy or sociopathy was passed down genetically.

Fallon’s premise was that psychopathy is genetically determined. An individual’s

genes determine whether they are psychopathic or not (Fallon 2013).Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 3/58

of inhibitions. In clinical analysis, these analytical categories should be distinguish

from psychosis, which is a condition involving a debilitating break with reality.

Psychopaths and sociopaths are o en able to manage their condition and pass as

“normal” citizens, although their capacity for manipulation and cruelty can have

devastating consequences for people around them. The term psychopathy is o e

used to emphasize that the source of the disorder is internal, based on psychologi

biological, or genetic factors, whereas sociopathy is used to emphasize predomin

social factors in the disorder: the social or familial sources of its development and

inability to be social or abide by societal rules (Hare 1999). In this sense sociopath

would be the sociological disease par excellence. It entails an incapacity for

companionship (socius), yet many accounts of sociopaths describe them as being

charming, attractively con dent, and outgoing (Hare 1999).

In a modern society characterized by the predominance of secondary rather than

primary relationships, the sociopath or psychopath functions, in popular culture at

least, as a prime index of contemporary social unease. The sociopath is like the ni

neighbour next door who one day “goes o” or is revealed to have had a sinister

second life. In many ways the sociopath is a cypher for many of the anxieties we h

about the loss of community and living among people we do not know. In this sens

the sociopath is a very modern sort of deviant. Contemporary approaches to

psychopathy and sociopathy have focused on biological and genetic causes. This i

tradition that goes back to 19th century positivist approaches to deviance, which

attempted to nd a biological cause for criminality and other types of deviant

behaviour.

The Italian professor of legal psychiatry Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909) was a key

gure in positivist criminology who thought he had isolated specic physiological

characteristics of “degeneracy” that could distinguish “born criminals” from norma

individuals (Rimke 2011). In a much more sophisticated way, this was also the pre

of Dr. James Fallon, a neuroscientist at the University of California. His research

involved analyzing brain scans of serial killers. He found that areas of the frontal a

temporal lobes associated with empathy, morality, and self-control are “shut o” in

serial killers. In turn, this lack of brain activity has been linked with specic genetic

markers suggesting that psychopathy or sociopathy was passed down genetically.

Fallon’s premise was that psychopathy is genetically determined. An individual’s

genes determine whether they are psychopathic or not (Fallon 2013).Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 4/58

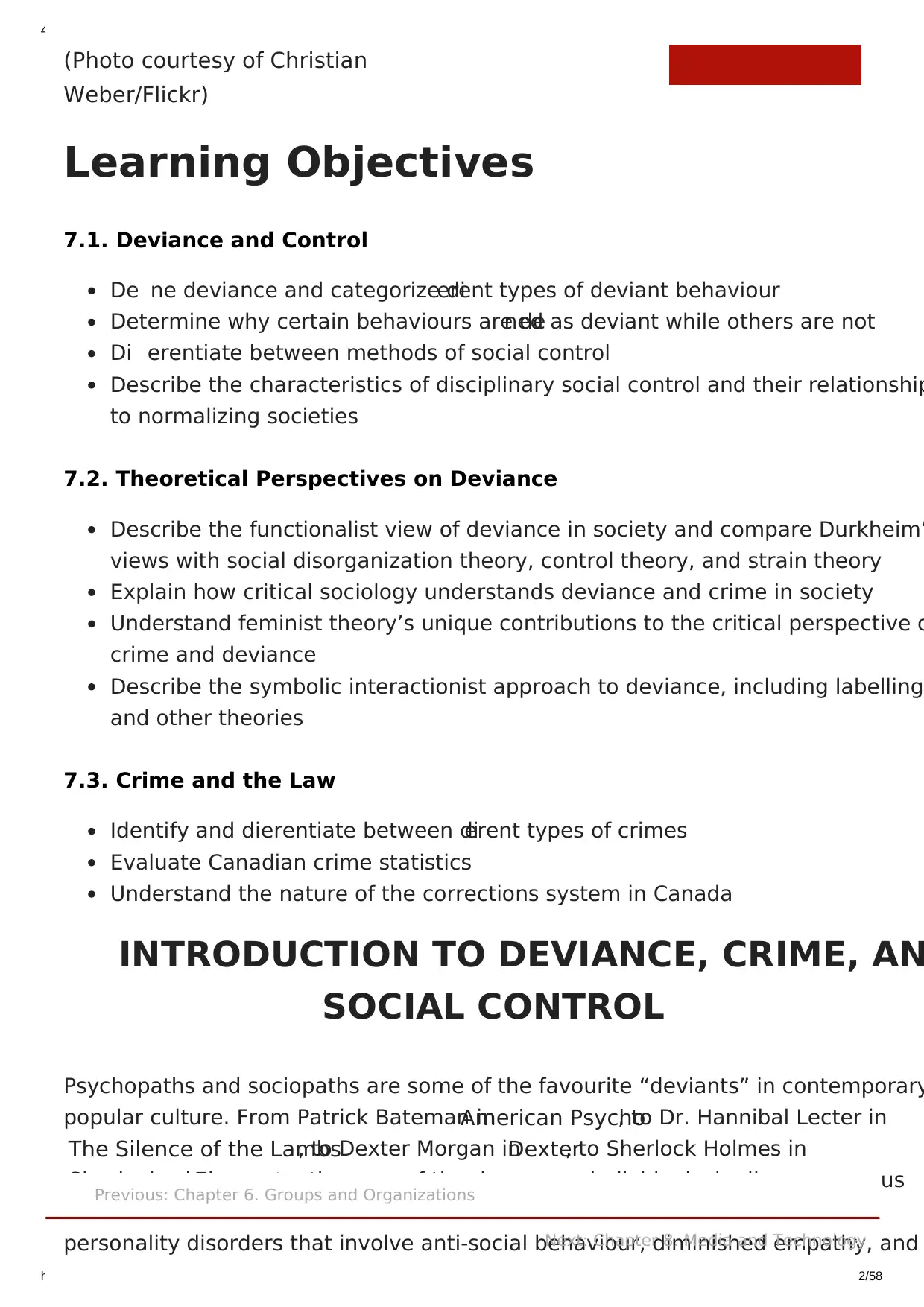

Figure 7.2. Lizzie Borden

(1860–1927) was tried but not

convicted of the axe murders

of her father and stepmother

in 1892. The popular rhyme of

the time went, “Lizzie Borden

took an axe, and gave her

mother 40 whacks.When she

saw what she had done, she

gave her father 41. ” (Photo

courtesy of Wikimedia

Commons).

However, at the same time that he was conducting research on psychopaths, he w

studying the brain scans of Alzheimer’s patients. In the Alzheimer’s study, he

discovered a brain scan from a control subject that indicated the symptoms of

psychopathy he had seen in the brain scans of serial killers. The scan was taken fr

member of his own family. He broke the seal that protected the identity of the sub

and discovered it was his own brain scan.

Fallon was a successfully married man, who had raised children and held down a

demanding career as a successful scientist and yet the brain scan indicated he wa

psychopath. When he researched his own genetic history, he realized that his fam

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 4/58

Figure 7.2. Lizzie Borden

(1860–1927) was tried but not

convicted of the axe murders

of her father and stepmother

in 1892. The popular rhyme of

the time went, “Lizzie Borden

took an axe, and gave her

mother 40 whacks.When she

saw what she had done, she

gave her father 41. ” (Photo

courtesy of Wikimedia

Commons).

However, at the same time that he was conducting research on psychopaths, he w

studying the brain scans of Alzheimer’s patients. In the Alzheimer’s study, he

discovered a brain scan from a control subject that indicated the symptoms of

psychopathy he had seen in the brain scans of serial killers. The scan was taken fr

member of his own family. He broke the seal that protected the identity of the sub

and discovered it was his own brain scan.

Fallon was a successfully married man, who had raised children and held down a

demanding career as a successful scientist and yet the brain scan indicated he wa

psychopath. When he researched his own genetic history, he realized that his fam

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 5/58

tree contained seven alleged murderers including the famous Lizzie Borden, who

allegedly killed her father and stepmother in 1892. He began to notice some of his

own behaviour patterns as being manipulative, obnoxiously competitive, egocentr

and aggressive, just not in a criminal manner.He decided that he was a “pro-socia

psychopath”—an individual who lacks true empathy for others but keeps his or he

behaviour within acceptable social norms—due to the loving and nurturing family

grew up in. He had to acknowledge that environment, and not just genes, played a

signi cant role in the expression of genetic tendencies (Fallon 2013).

What can we learn from Fallon’s example from a sociological point of view? Firstly

psychopathy and sociopathy are recognized as problematic forms of deviance bec

of prevalent social anxieties about serial killers as types of criminal who “live next

door” or blend in. This is partly because we live in a type of society where we do n

know our neighbours well and partly because we are concerned to discover their

identi able traits as these are otherwise concealed. Secondly, Fallon acknowledge

that there is no purely biological or genetic explanation for psychopathy and

sociopathy.

Many individuals with the biological and genetic markers of psychopathy are not

dangers to society—key to pathological expressions of psychopathy are elements

individual’s social environment and social upbringing (i.e., nurture). Finally, in

Fallon’s own account, it is dicult to separate the discovery of the aberrant brain

scan and the discovery and acknowledgement of his personal traits of psychopath

it clear which came rst? He only recognizes the psychopatholoy in himself aer

seeing the brain scan. This is the problem of what Ian Hacking (2006) calls the

“looping e ect” that aects the sociological study of deviance (see discussion below)

In summary, what Fallon’s example illustrates is the complexity of the study of soc

deviance.

7.1. DEVIANCE AND CONTROL

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 5/58

tree contained seven alleged murderers including the famous Lizzie Borden, who

allegedly killed her father and stepmother in 1892. He began to notice some of his

own behaviour patterns as being manipulative, obnoxiously competitive, egocentr

and aggressive, just not in a criminal manner.He decided that he was a “pro-socia

psychopath”—an individual who lacks true empathy for others but keeps his or he

behaviour within acceptable social norms—due to the loving and nurturing family

grew up in. He had to acknowledge that environment, and not just genes, played a

signi cant role in the expression of genetic tendencies (Fallon 2013).

What can we learn from Fallon’s example from a sociological point of view? Firstly

psychopathy and sociopathy are recognized as problematic forms of deviance bec

of prevalent social anxieties about serial killers as types of criminal who “live next

door” or blend in. This is partly because we live in a type of society where we do n

know our neighbours well and partly because we are concerned to discover their

identi able traits as these are otherwise concealed. Secondly, Fallon acknowledge

that there is no purely biological or genetic explanation for psychopathy and

sociopathy.

Many individuals with the biological and genetic markers of psychopathy are not

dangers to society—key to pathological expressions of psychopathy are elements

individual’s social environment and social upbringing (i.e., nurture). Finally, in

Fallon’s own account, it is dicult to separate the discovery of the aberrant brain

scan and the discovery and acknowledgement of his personal traits of psychopath

it clear which came rst? He only recognizes the psychopatholoy in himself aer

seeing the brain scan. This is the problem of what Ian Hacking (2006) calls the

“looping e ect” that aects the sociological study of deviance (see discussion below)

In summary, what Fallon’s example illustrates is the complexity of the study of soc

deviance.

7.1. DEVIANCE AND CONTROL

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 6/58

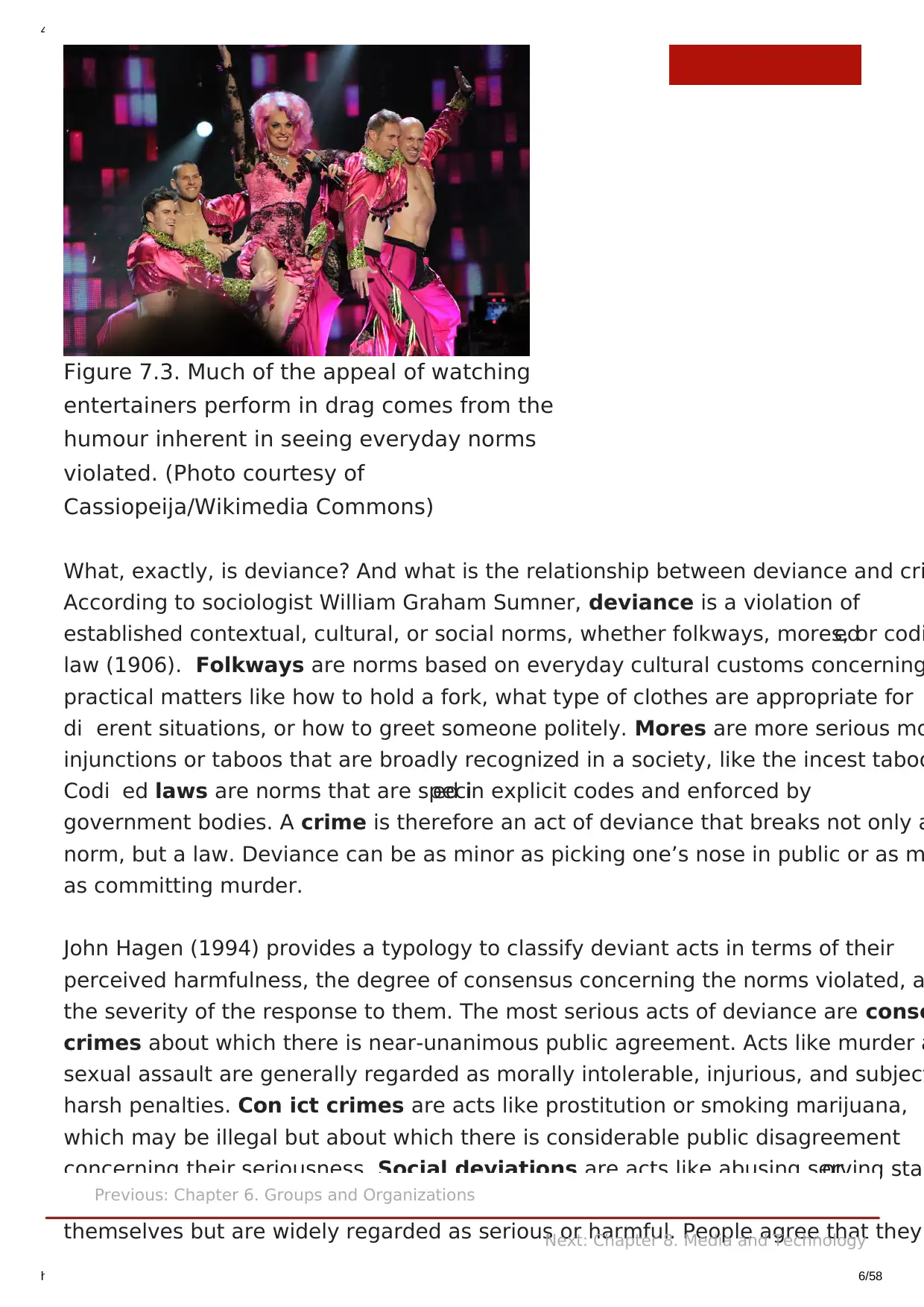

Figure 7.3. Much of the appeal of watching

entertainers perform in drag comes from the

humour inherent in seeing everyday norms

violated. (Photo courtesy of

Cassiopeija/Wikimedia Commons)

What, exactly, is deviance? And what is the relationship between deviance and cri

According to sociologist William Graham Sumner, deviance is a violation of

established contextual, cultural, or social norms, whether folkways, mores, or codied

law (1906). Folkways are norms based on everyday cultural customs concerning

practical matters like how to hold a fork, what type of clothes are appropriate for

di erent situations, or how to greet someone politely. Mores are more serious mo

injunctions or taboos that are broadly recognized in a society, like the incest taboo

Codi ed laws are norms that are specied in explicit codes and enforced by

government bodies. A crime is therefore an act of deviance that breaks not only a

norm, but a law. Deviance can be as minor as picking one’s nose in public or as m

as committing murder.

John Hagen (1994) provides a typology to classify deviant acts in terms of their

perceived harmfulness, the degree of consensus concerning the norms violated, a

the severity of the response to them. The most serious acts of deviance are conse

crimes about which there is near-unanimous public agreement. Acts like murder a

sexual assault are generally regarded as morally intolerable, injurious, and subject

harsh penalties. Con ict crimes are acts like prostitution or smoking marijuana,

which may be illegal but about which there is considerable public disagreement

concerning their seriousness. Social deviations are acts like abusing serving staor

behaviours arising from mental illness and addiction, which are not illegal in

themselves but are widely regarded as serious or harmful. People agree that they

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 6/58

Figure 7.3. Much of the appeal of watching

entertainers perform in drag comes from the

humour inherent in seeing everyday norms

violated. (Photo courtesy of

Cassiopeija/Wikimedia Commons)

What, exactly, is deviance? And what is the relationship between deviance and cri

According to sociologist William Graham Sumner, deviance is a violation of

established contextual, cultural, or social norms, whether folkways, mores, or codied

law (1906). Folkways are norms based on everyday cultural customs concerning

practical matters like how to hold a fork, what type of clothes are appropriate for

di erent situations, or how to greet someone politely. Mores are more serious mo

injunctions or taboos that are broadly recognized in a society, like the incest taboo

Codi ed laws are norms that are specied in explicit codes and enforced by

government bodies. A crime is therefore an act of deviance that breaks not only a

norm, but a law. Deviance can be as minor as picking one’s nose in public or as m

as committing murder.

John Hagen (1994) provides a typology to classify deviant acts in terms of their

perceived harmfulness, the degree of consensus concerning the norms violated, a

the severity of the response to them. The most serious acts of deviance are conse

crimes about which there is near-unanimous public agreement. Acts like murder a

sexual assault are generally regarded as morally intolerable, injurious, and subject

harsh penalties. Con ict crimes are acts like prostitution or smoking marijuana,

which may be illegal but about which there is considerable public disagreement

concerning their seriousness. Social deviations are acts like abusing serving staor

behaviours arising from mental illness and addiction, which are not illegal in

themselves but are widely regarded as serious or harmful. People agree that they

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 7/58

for institutional intervention. Finally there are social diversions like riding

skateboards on sidewalks, overly tight leggings, or facial piercings that violate nor

in a provocative way but are generally regarded as distasteful but harmless, or for

some, cool.

The point is that the question, “What is deviant behaviour?” cannot be answered i

straightforward manner. This follows from two key insights of the sociological

approach to deviance (which distinguish it from moral and legalistic approaches).

Firstly, deviance is dened by its social context. To understand why some acts are

deviant and some are not, it is necessary to understand what the context is, what

existing rules are, and how these rules came to be established. If the rules change

what counts as deviant also changes. As rules and norms vary across cultures and

time, it makes sense that notions of deviance also change.

Fi y years ago, public schools in Canada had strict dress codes that, among other

stipulations, o en banned women from wearing pants to class. Today, it is socially

acceptable for women to wear pants, but less so for men to wear skirts. In a time o

war, acts usually considered morally reprehensible, such as taking the life of anoth

may actually be rewarded. Much of the confusion and ambiguity regarding the use

violence in hockey has to do with the dierent sets of rules that apply inside and

outside the arena. Acts that are acceptable and even encouraged on the ice would

punished with jail time if they occurred on the street.

Whether an act is deviant or not depends on society’s denition of that act. Acts are

not deviant in themselves. The second sociological insight is that deviance is not a

intrinsic (biological or psychological) attribute of individuals, nor of the acts

themselves, but a product ofsocial processes. The norms themselves, or the social

contexts that determine which acts are deviant or not, are continually dened and

rede ned through ongoing social processes—political, legal, cultural, etc. One way

which certain activities or people come to be understood and dened as deviant is

through the intervention of moral entrepreneurs.

Becker (1963) dened moral entrepreneurs as individuals or groups who, in the

service of their own interests, publicize and problematize “wrongdoing” and have

power to create and enforce rules to penalize wrongdoing. Judge Emily Murphy,

commonly known today as one of the “Famous Five” feminist su ragists who fough

to have women legally recognized as “persons” (and thereby qualied to hold a

position in the Canadian Senate), was a moral entrepreneur instrumental in chang

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 7/58

for institutional intervention. Finally there are social diversions like riding

skateboards on sidewalks, overly tight leggings, or facial piercings that violate nor

in a provocative way but are generally regarded as distasteful but harmless, or for

some, cool.

The point is that the question, “What is deviant behaviour?” cannot be answered i

straightforward manner. This follows from two key insights of the sociological

approach to deviance (which distinguish it from moral and legalistic approaches).

Firstly, deviance is dened by its social context. To understand why some acts are

deviant and some are not, it is necessary to understand what the context is, what

existing rules are, and how these rules came to be established. If the rules change

what counts as deviant also changes. As rules and norms vary across cultures and

time, it makes sense that notions of deviance also change.

Fi y years ago, public schools in Canada had strict dress codes that, among other

stipulations, o en banned women from wearing pants to class. Today, it is socially

acceptable for women to wear pants, but less so for men to wear skirts. In a time o

war, acts usually considered morally reprehensible, such as taking the life of anoth

may actually be rewarded. Much of the confusion and ambiguity regarding the use

violence in hockey has to do with the dierent sets of rules that apply inside and

outside the arena. Acts that are acceptable and even encouraged on the ice would

punished with jail time if they occurred on the street.

Whether an act is deviant or not depends on society’s denition of that act. Acts are

not deviant in themselves. The second sociological insight is that deviance is not a

intrinsic (biological or psychological) attribute of individuals, nor of the acts

themselves, but a product ofsocial processes. The norms themselves, or the social

contexts that determine which acts are deviant or not, are continually dened and

rede ned through ongoing social processes—political, legal, cultural, etc. One way

which certain activities or people come to be understood and dened as deviant is

through the intervention of moral entrepreneurs.

Becker (1963) dened moral entrepreneurs as individuals or groups who, in the

service of their own interests, publicize and problematize “wrongdoing” and have

power to create and enforce rules to penalize wrongdoing. Judge Emily Murphy,

commonly known today as one of the “Famous Five” feminist su ragists who fough

to have women legally recognized as “persons” (and thereby qualied to hold a

position in the Canadian Senate), was a moral entrepreneur instrumental in chang

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 8/58

Canada’s drug laws. In 1922 she wroteThe Black Candle, in which she demonized the

use of marijuana:

[Marijuana] has the eect of driving the [user] completely insane. The addict loses al

sense of moral responsibility. Addicts to this drug, while under its in uence, are

immune to pain, and could be severely injured without having any realization of th

condition. While in this condition they become raving maniacs and are liable to kill

indulge in any form of violence to other persons, using the most savage methods o

cruelty without, as said before, any sense of moral responsibility…. They are

dispossessed of their natural and normal will power, and their mentality is that of

idiots. If this drug is indulged in to any great extent, it ends in the untimely death

its addict (Murphy 1922).

One of the tactics used by moral entrepreneurs is to create a moral panic about

activities, like marijuana use, that they deem deviant. A moral panic occurs when

media-fuelled public fear and overreaction lead authorities to label and repress

deviants, which in turn creates a cycle in which more acts of deviance are discove

more fear is generated, and more suppression enacted. The key insight is that

individuals’ deviant status is ascribed to them through social processes. Individual

are not born deviant, but become deviant through their interaction with reference

groups, institutions, and authorities.

Through social interaction, individuals are labelled deviant or come to recognize

themselves as deviant. For example, in ancient Greece, homosexual relationships

between older men and young acolytes were a normal component of the teacher-

student relationship. Up until the 19th century, the question of who slept with who

was a matter of indierence to the law or customs, except where it related to family

alliances through marriage and the transfer of property through inheritance.

However, in the 19th century sexuality became a matter of moral, legal, and

psychological concern. The homosexual, or “sexual invert,” was dened by the

emerging psychiatric and biological disciplines as a psychological deviant whose

instincts were contrary to nature.

Homosexuality was dened as not simply a matter of sexual desire or the act of sex,

but as a dangerous quality that dened the entire personality and moral being of an

individual (Foucault 1980). From that point until the late 1960s, homosexuality wa

regarded as a deviant, closeted activity that, if exposed, could result in legal

prosecution, moral condemnation, ostracism, violent assault, and loss of career. S

then, the gay rights movement and constitutional protections of civil liberties have

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 8/58

Canada’s drug laws. In 1922 she wroteThe Black Candle, in which she demonized the

use of marijuana:

[Marijuana] has the eect of driving the [user] completely insane. The addict loses al

sense of moral responsibility. Addicts to this drug, while under its in uence, are

immune to pain, and could be severely injured without having any realization of th

condition. While in this condition they become raving maniacs and are liable to kill

indulge in any form of violence to other persons, using the most savage methods o

cruelty without, as said before, any sense of moral responsibility…. They are

dispossessed of their natural and normal will power, and their mentality is that of

idiots. If this drug is indulged in to any great extent, it ends in the untimely death

its addict (Murphy 1922).

One of the tactics used by moral entrepreneurs is to create a moral panic about

activities, like marijuana use, that they deem deviant. A moral panic occurs when

media-fuelled public fear and overreaction lead authorities to label and repress

deviants, which in turn creates a cycle in which more acts of deviance are discove

more fear is generated, and more suppression enacted. The key insight is that

individuals’ deviant status is ascribed to them through social processes. Individual

are not born deviant, but become deviant through their interaction with reference

groups, institutions, and authorities.

Through social interaction, individuals are labelled deviant or come to recognize

themselves as deviant. For example, in ancient Greece, homosexual relationships

between older men and young acolytes were a normal component of the teacher-

student relationship. Up until the 19th century, the question of who slept with who

was a matter of indierence to the law or customs, except where it related to family

alliances through marriage and the transfer of property through inheritance.

However, in the 19th century sexuality became a matter of moral, legal, and

psychological concern. The homosexual, or “sexual invert,” was dened by the

emerging psychiatric and biological disciplines as a psychological deviant whose

instincts were contrary to nature.

Homosexuality was dened as not simply a matter of sexual desire or the act of sex,

but as a dangerous quality that dened the entire personality and moral being of an

individual (Foucault 1980). From that point until the late 1960s, homosexuality wa

regarded as a deviant, closeted activity that, if exposed, could result in legal

prosecution, moral condemnation, ostracism, violent assault, and loss of career. S

then, the gay rights movement and constitutional protections of civil liberties have

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 9/58

reversed many of the attitudes and legal structures that led to the prosecution of

lesbians, and transgendered people. The point is that to whatever degree

homosexuality has a natural or inborn biological cause, its deviance is the outco

of a social process.

It is not simply a matter of the events that lead authorities to dene an activity or

category of persons deviant, but of the processes by which individuals come to

recognize themselves as deviant. In the process of socialization, there is a “loopin

e ect” (Hacking 2006). Once a category of deviance has been established and ap

to a person, that person begins to dene himself or herself in terms of this category

and behave accordingly. This in uence makes it dicult to dene criminals as kinds

of person in terms of pre-existing, innate predispositions or individual

psychopathologies. As we will see later in the chapter, it is a central tenet of symb

interactionist labelling theory, that individuals become criminalized through con

with the criminal justice system (Becker 1963). When we add to this insight the

sociological research into the social characteristics of those who have been arreste

processed by the criminal justice system—variables such as gender, age, race,

class— it is evident that social variables and power structures are key to

understanding who chooses a criminal career path.

One of the principle outcomes of these two sociological insights is that a focus on

social constructionof di erent social experiences and problems leads to alternative

ways of understanding them and responding to them. In the study of crime and

deviance, the sociologist o en confronts a legacy of entrenched beliefs concerning

either the innate biological disposition or the individual psychopathology of person

considered abnormal: the criminal personality, the sexual or gender “deviant,” the

disabled or ill person, the addict, or the mentally unstable individual. However, as

Hacking observes, even when these beliefs about kinds of persons are products of

objective scientic classi cation, the institutional context of science and expert

knowledge is not independent of societal norms, beliefs, and practices (2006).

The process of classifying kinds of people is a social process that Hacking calls

“making up people” and Howard Becker calls “labelling” (1963). Crime and devian

are social constructs that vary according to the denitions of crime, the forms and

e ectiveness of policing, the social characteristics of criminals, and the relations o

power that structure society. Part of the problem of deviance is that the social pro

of labelling some kinds of persons or activities as abnormal or deviant limits the ty

of social responses available. The major issue is not that labels are arbitrary or tha

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 9/58

reversed many of the attitudes and legal structures that led to the prosecution of

lesbians, and transgendered people. The point is that to whatever degree

homosexuality has a natural or inborn biological cause, its deviance is the outco

of a social process.

It is not simply a matter of the events that lead authorities to dene an activity or

category of persons deviant, but of the processes by which individuals come to

recognize themselves as deviant. In the process of socialization, there is a “loopin

e ect” (Hacking 2006). Once a category of deviance has been established and ap

to a person, that person begins to dene himself or herself in terms of this category

and behave accordingly. This in uence makes it dicult to dene criminals as kinds

of person in terms of pre-existing, innate predispositions or individual

psychopathologies. As we will see later in the chapter, it is a central tenet of symb

interactionist labelling theory, that individuals become criminalized through con

with the criminal justice system (Becker 1963). When we add to this insight the

sociological research into the social characteristics of those who have been arreste

processed by the criminal justice system—variables such as gender, age, race,

class— it is evident that social variables and power structures are key to

understanding who chooses a criminal career path.

One of the principle outcomes of these two sociological insights is that a focus on

social constructionof di erent social experiences and problems leads to alternative

ways of understanding them and responding to them. In the study of crime and

deviance, the sociologist o en confronts a legacy of entrenched beliefs concerning

either the innate biological disposition or the individual psychopathology of person

considered abnormal: the criminal personality, the sexual or gender “deviant,” the

disabled or ill person, the addict, or the mentally unstable individual. However, as

Hacking observes, even when these beliefs about kinds of persons are products of

objective scientic classi cation, the institutional context of science and expert

knowledge is not independent of societal norms, beliefs, and practices (2006).

The process of classifying kinds of people is a social process that Hacking calls

“making up people” and Howard Becker calls “labelling” (1963). Crime and devian

are social constructs that vary according to the denitions of crime, the forms and

e ectiveness of policing, the social characteristics of criminals, and the relations o

power that structure society. Part of the problem of deviance is that the social pro

of labelling some kinds of persons or activities as abnormal or deviant limits the ty

of social responses available. The major issue is not that labels are arbitrary or tha

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 10/58

is possible not to use labels at all, but that the choice of label has consequences. W

gets labelled by whom and the way social labels are applied have powerful social

repercussions.

MAKING CONNECTIONS: CAREERS IN SOCIOL

Why I Drive a Hearse

When Neil Young le Canada in 1966 to seek his fortune in California as a musician,

he was driving his famous 1953 Pontiac hearse “Mort 2.” He and Bruce Palmer we

driving the hearse in Hollywood when they happened to see Stephen Stills and Ric

Furray driving the other way, a fortuitous encounter that led to the formation of th

band Bu alo Spring eld (McDonough 2002). Later Young wrote “Long May You Run

as an elegy to his rst hearse “Mort,” which he performed at the closing ceremonie

of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. Rock musicians are o en noted for thei

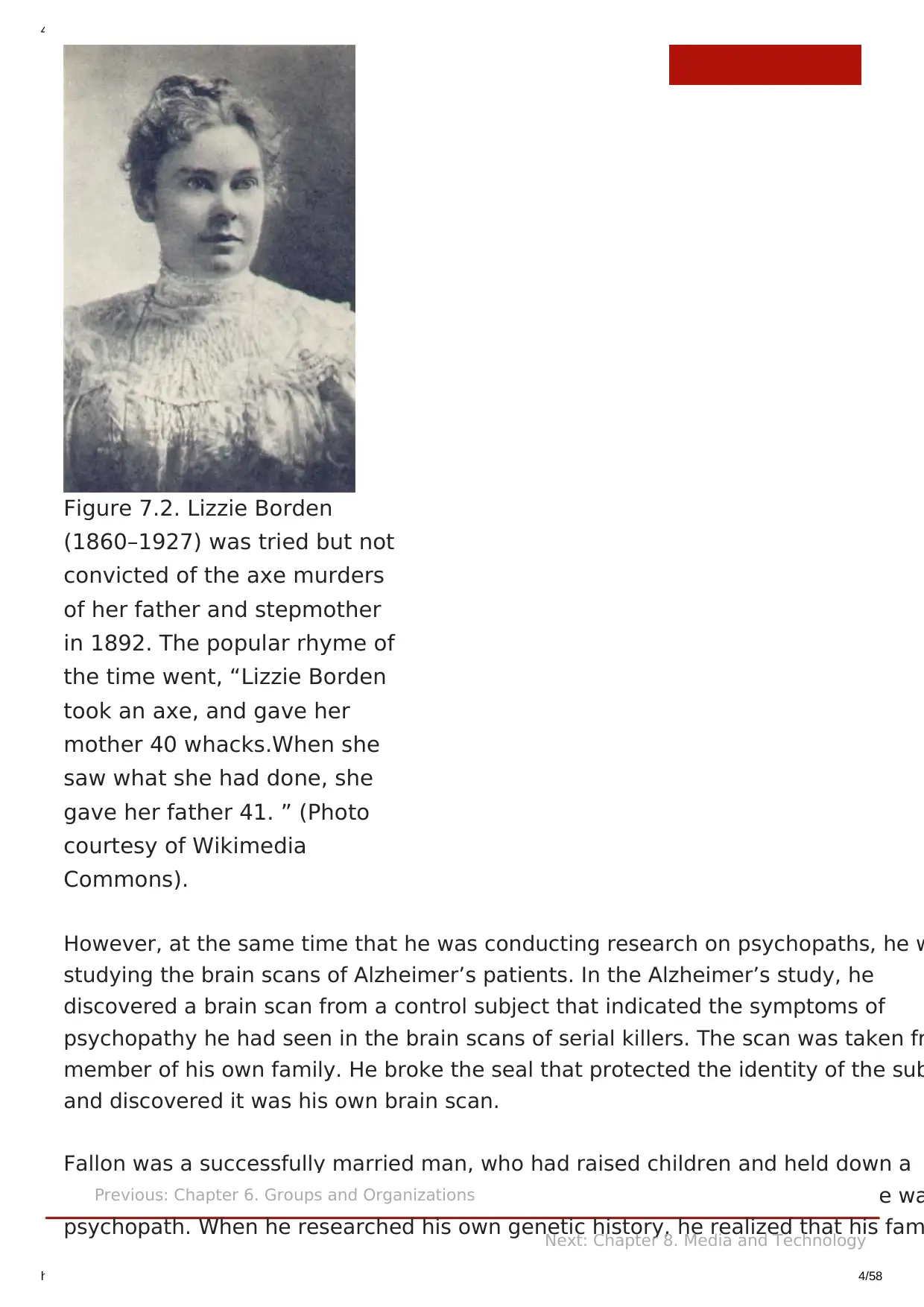

eccentricities, but is driving a hearse deviant behaviour? When sociologist Todd

Schoep in ran into his childhood friend Bill who drove a hearse, he wondered what

e ect driving a hearse had on his friend and what eect it might have on others on

the road. Would using such a vehicle for everyday errands be considered deviant b

most people? Schoep in interviewed Bill, curious rst to know why he drove such an

unconventional car. Bill had simply been on the lookout for a reliable winter car; o

tight budget, he searched used car ads and stumbled on one for the hearse. The c

ran well and the price was right, so he bought it. Bill admitted that others’ reaction

to the car had been mixed. His parents were appalled and he received odd stares

his coworkers. A mechanic once refused to work on it, stating that it was “a dead

person machine.” On the whole, however, Bill received mostly positive reactions.

Strangers gave him a thumbs-up on the highway and stopped him in parking lots t

chat about his car. His girlfriend loved it, his friends wanted to take it tailgating, an

people o ered to buy it. Could it be that driving a hearse isn’t really so deviant aer

all? Schoep in theorized that, although viewed as outside conventional norms,

driving a hearse is such a mild form of deviance that it actually becomes a mark o

distinction. Conformists nd the choice of vehicle intriguing or appealing, while

nonconformists see a fellow oddball to whom they can relate. As one of Bill’s frien

remarked, “Every guy wants to own a unique car like this andyoucan certainly pull it

o .” Such anecdotes remind us that although deviance is o en viewed as a violation

norms, it’s not always viewed in a negative light (Schoep in 2011).

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 10/58

is possible not to use labels at all, but that the choice of label has consequences. W

gets labelled by whom and the way social labels are applied have powerful social

repercussions.

MAKING CONNECTIONS: CAREERS IN SOCIOL

Why I Drive a Hearse

When Neil Young le Canada in 1966 to seek his fortune in California as a musician,

he was driving his famous 1953 Pontiac hearse “Mort 2.” He and Bruce Palmer we

driving the hearse in Hollywood when they happened to see Stephen Stills and Ric

Furray driving the other way, a fortuitous encounter that led to the formation of th

band Bu alo Spring eld (McDonough 2002). Later Young wrote “Long May You Run

as an elegy to his rst hearse “Mort,” which he performed at the closing ceremonie

of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. Rock musicians are o en noted for thei

eccentricities, but is driving a hearse deviant behaviour? When sociologist Todd

Schoep in ran into his childhood friend Bill who drove a hearse, he wondered what

e ect driving a hearse had on his friend and what eect it might have on others on

the road. Would using such a vehicle for everyday errands be considered deviant b

most people? Schoep in interviewed Bill, curious rst to know why he drove such an

unconventional car. Bill had simply been on the lookout for a reliable winter car; o

tight budget, he searched used car ads and stumbled on one for the hearse. The c

ran well and the price was right, so he bought it. Bill admitted that others’ reaction

to the car had been mixed. His parents were appalled and he received odd stares

his coworkers. A mechanic once refused to work on it, stating that it was “a dead

person machine.” On the whole, however, Bill received mostly positive reactions.

Strangers gave him a thumbs-up on the highway and stopped him in parking lots t

chat about his car. His girlfriend loved it, his friends wanted to take it tailgating, an

people o ered to buy it. Could it be that driving a hearse isn’t really so deviant aer

all? Schoep in theorized that, although viewed as outside conventional norms,

driving a hearse is such a mild form of deviance that it actually becomes a mark o

distinction. Conformists nd the choice of vehicle intriguing or appealing, while

nonconformists see a fellow oddball to whom they can relate. As one of Bill’s frien

remarked, “Every guy wants to own a unique car like this andyoucan certainly pull it

o .” Such anecdotes remind us that although deviance is o en viewed as a violation

norms, it’s not always viewed in a negative light (Schoep in 2011).

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 11/58

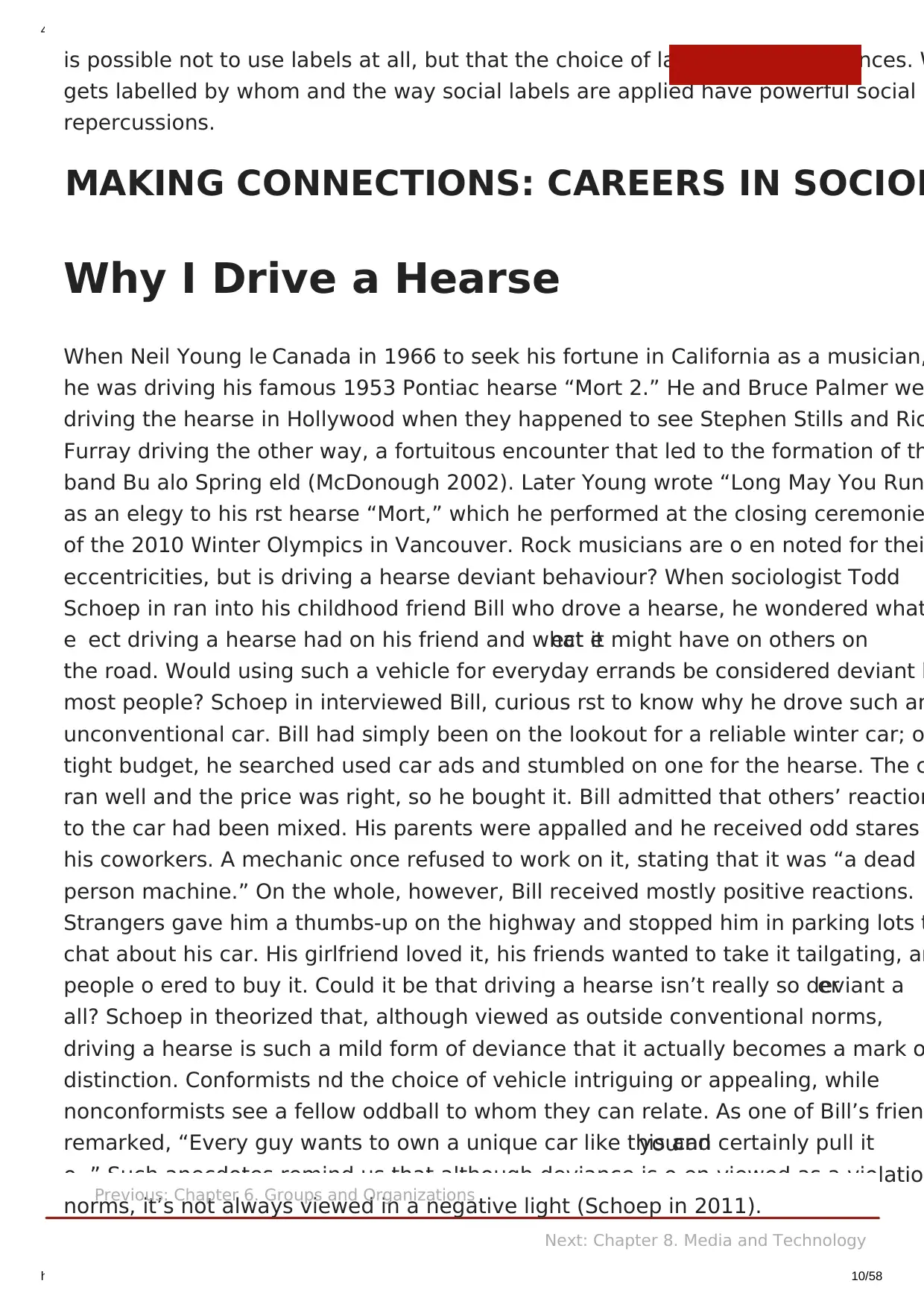

Figure 7.4. A hearse with the license

plate “LASTRYD.” How would you

view the owner of this car? (Photo

courtesy of Brian Teutsch/ickr)

Social Control

When a person violates a social norm, what happens? A driver caught speeding ca

receive a speeding ticket. A student who texts in class gets a warning from a profe

An adult belching loudly is avoided. All societies practise social control, the

regulation and enforcement of norms. Social control can be dened broadly as an

organized action intended to change people’s behaviour (Innes 2003). The underly

goal of social control is to maintain social order, an arrangement of practices and

behaviours on which society’s members base their daily lives. Think of social order

an employee handbook and social control as the incentives and disincentives used

encourage or oblige employees to follow those rules. When a worker violates a

workplace guideline, the manager steps in to enforce the rules. One means of

enforcing rules are through sanctions. Sanctions can be positive as well as negat

Positive sanctions are rewards given for conforming to norms. A promotion at w

is a positive sanction for working hard. Negative sanctions are punishments for

violating norms. Being arrested is a punishment for shopliing. Both types of

sanctions play a role in social control.

Sociologists also classify sanctions as formal or informal. Although shopliing, a form

of social deviance, may be illegal, there are no laws dictating the proper way to

scratch one’s nose. That doesn’t mean picking your nose in public won’t be punish

instead, you will encounter informal sanctions. Informal sanctions emerge in fac

face social interactions. For example, wearing ip-ops to an opera or swearing

loudly in church may draw disapproving looks or even verbal reprimands, whereas

behaviour that is seen as positive—such as helping an old man carry grocery bags

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 11/58

Figure 7.4. A hearse with the license

plate “LASTRYD.” How would you

view the owner of this car? (Photo

courtesy of Brian Teutsch/ickr)

Social Control

When a person violates a social norm, what happens? A driver caught speeding ca

receive a speeding ticket. A student who texts in class gets a warning from a profe

An adult belching loudly is avoided. All societies practise social control, the

regulation and enforcement of norms. Social control can be dened broadly as an

organized action intended to change people’s behaviour (Innes 2003). The underly

goal of social control is to maintain social order, an arrangement of practices and

behaviours on which society’s members base their daily lives. Think of social order

an employee handbook and social control as the incentives and disincentives used

encourage or oblige employees to follow those rules. When a worker violates a

workplace guideline, the manager steps in to enforce the rules. One means of

enforcing rules are through sanctions. Sanctions can be positive as well as negat

Positive sanctions are rewards given for conforming to norms. A promotion at w

is a positive sanction for working hard. Negative sanctions are punishments for

violating norms. Being arrested is a punishment for shopliing. Both types of

sanctions play a role in social control.

Sociologists also classify sanctions as formal or informal. Although shopliing, a form

of social deviance, may be illegal, there are no laws dictating the proper way to

scratch one’s nose. That doesn’t mean picking your nose in public won’t be punish

instead, you will encounter informal sanctions. Informal sanctions emerge in fac

face social interactions. For example, wearing ip-ops to an opera or swearing

loudly in church may draw disapproving looks or even verbal reprimands, whereas

behaviour that is seen as positive—such as helping an old man carry grocery bags

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 12/58

across the street—may receive positive informal reactions, such as a smile or pat

the back.

Formal sanctions, on the other hand, are ways to ocially recognize and enforce

norm violations. If a student plagiarizes the work of others or cheats on an exam,

example, he or she might be expelled. Someone who speaks inappropriately to the

boss could be red. Someone who commits a crime may be arrested or imprisoned.

On the positive side, a soldier who saves a life may receive an ocial commendation,

or a CEO might receive a bonus for increasing the pro ts of his or her corporation.

Not all forms of social control are adequately understood through the use of

sanctions, however. Black (1976) identies four key styles of social control, each of

which de nes deviance and the appropriate response to it in a dierent manner.

Penal social control functions by prohibiting certain social behaviours and

responding to violations with punishment. Compensatory social control obliges

o ender to pay a victim to compensate for a harm committed. Therapeutic socia

control involves the use of therapy to return individuals to a normal state.

Conciliatory social control aims to reconcile the parties of a dispute and mutua

restore harmony to a social relationship that has been damaged. While penal and

compensatory social controls emphasize the use of sanctions, therapeutic and

conciliatory social controls emphasize processes of restoration and healing.

Social Control as Government and

Discipline

Michel Foucault notes that from a period of early modernity onward, European

society became increasingly concerned with social control as a practice of

government (Foucault 2007). In this sense of the term, government does not simp

refer to the activities of the state, but to all the practices by which individuals or

organizations seek to govern the behaviour of others or themselves. Government

refers to the strategies by which one seeks to direct or guide the conduct of anoth

others. In the 15th and 16th centuries, numerous treatises were written on how to

govern and educate children, how to govern the poor and beggars, how to govern

family or an estate, how to govern an army or a city, how to govern a state and ru

economy, and how to govern one’s own conscience and conduct. These treatises

described the burgeoning arts of government, which dened the dierent ways in

which the conduct of individuals or groups might be directed. Niccolo Machiavelli’s

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 12/58

across the street—may receive positive informal reactions, such as a smile or pat

the back.

Formal sanctions, on the other hand, are ways to ocially recognize and enforce

norm violations. If a student plagiarizes the work of others or cheats on an exam,

example, he or she might be expelled. Someone who speaks inappropriately to the

boss could be red. Someone who commits a crime may be arrested or imprisoned.

On the positive side, a soldier who saves a life may receive an ocial commendation,

or a CEO might receive a bonus for increasing the pro ts of his or her corporation.

Not all forms of social control are adequately understood through the use of

sanctions, however. Black (1976) identies four key styles of social control, each of

which de nes deviance and the appropriate response to it in a dierent manner.

Penal social control functions by prohibiting certain social behaviours and

responding to violations with punishment. Compensatory social control obliges

o ender to pay a victim to compensate for a harm committed. Therapeutic socia

control involves the use of therapy to return individuals to a normal state.

Conciliatory social control aims to reconcile the parties of a dispute and mutua

restore harmony to a social relationship that has been damaged. While penal and

compensatory social controls emphasize the use of sanctions, therapeutic and

conciliatory social controls emphasize processes of restoration and healing.

Social Control as Government and

Discipline

Michel Foucault notes that from a period of early modernity onward, European

society became increasingly concerned with social control as a practice of

government (Foucault 2007). In this sense of the term, government does not simp

refer to the activities of the state, but to all the practices by which individuals or

organizations seek to govern the behaviour of others or themselves. Government

refers to the strategies by which one seeks to direct or guide the conduct of anoth

others. In the 15th and 16th centuries, numerous treatises were written on how to

govern and educate children, how to govern the poor and beggars, how to govern

family or an estate, how to govern an army or a city, how to govern a state and ru

economy, and how to govern one’s own conscience and conduct. These treatises

described the burgeoning arts of government, which dened the dierent ways in

which the conduct of individuals or groups might be directed. Niccolo Machiavelli’s

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 13/58

The Prince(1532), which o ers advice to the prince on how best to conduct his

relationship with his subjects, is the most famous of these treatises.

Figure 7.5. Machiavelli:

“If an injury has to be

done to a man it should

be so severe that his

vengeance need not be

feared.” The ruthlessness

with which Machiavelli

advised the prince to

govern his relationships

with subjects and rivals

has earned its own

adjective in common

usage: Machiavellian.

(Image courtesy of

Wikipedia Commons)

The common theme in the various arts of governing proposed in early modernity w

the extension of Christian monastic practices involving the detailed and continuou

government and salvation of souls. The principles of monastic government were

applied to a variety of non-monastic areas. People needed to be governed in all as

of their lives. It was not, however, until the 19th century and the invention of mod

institutions like the prison, the public school, the modern army, the asylum, thePrevious: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 13/58

The Prince(1532), which o ers advice to the prince on how best to conduct his

relationship with his subjects, is the most famous of these treatises.

Figure 7.5. Machiavelli:

“If an injury has to be

done to a man it should

be so severe that his

vengeance need not be

feared.” The ruthlessness

with which Machiavelli

advised the prince to

govern his relationships

with subjects and rivals

has earned its own

adjective in common

usage: Machiavellian.

(Image courtesy of

Wikipedia Commons)

The common theme in the various arts of governing proposed in early modernity w

the extension of Christian monastic practices involving the detailed and continuou

government and salvation of souls. The principles of monastic government were

applied to a variety of non-monastic areas. People needed to be governed in all as

of their lives. It was not, however, until the 19th century and the invention of mod

institutions like the prison, the public school, the modern army, the asylum, thePrevious: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 14/58

hospital, and the factory, that the means for extending government and social con

widely through the population were developed.

Foucault (1979) describes these modern forms of government as disciplinary soc

control because they each rely on the detailed continuous training, control, and

observation of individuals to improve their capabilities: to transform criminals into

law abiding citizens, children into educated and productive adults, recruits into

disciplined soldiers, patients into healthy people, etc. Foucault argues that the ide

discipline as a means of social control is to render individuals docile. That does no

mean that they become passive or sheep-like, but that disciplinary

training simultaneously increases their abilities, skills, and usefulness while makin

them more compliant and manipulable.

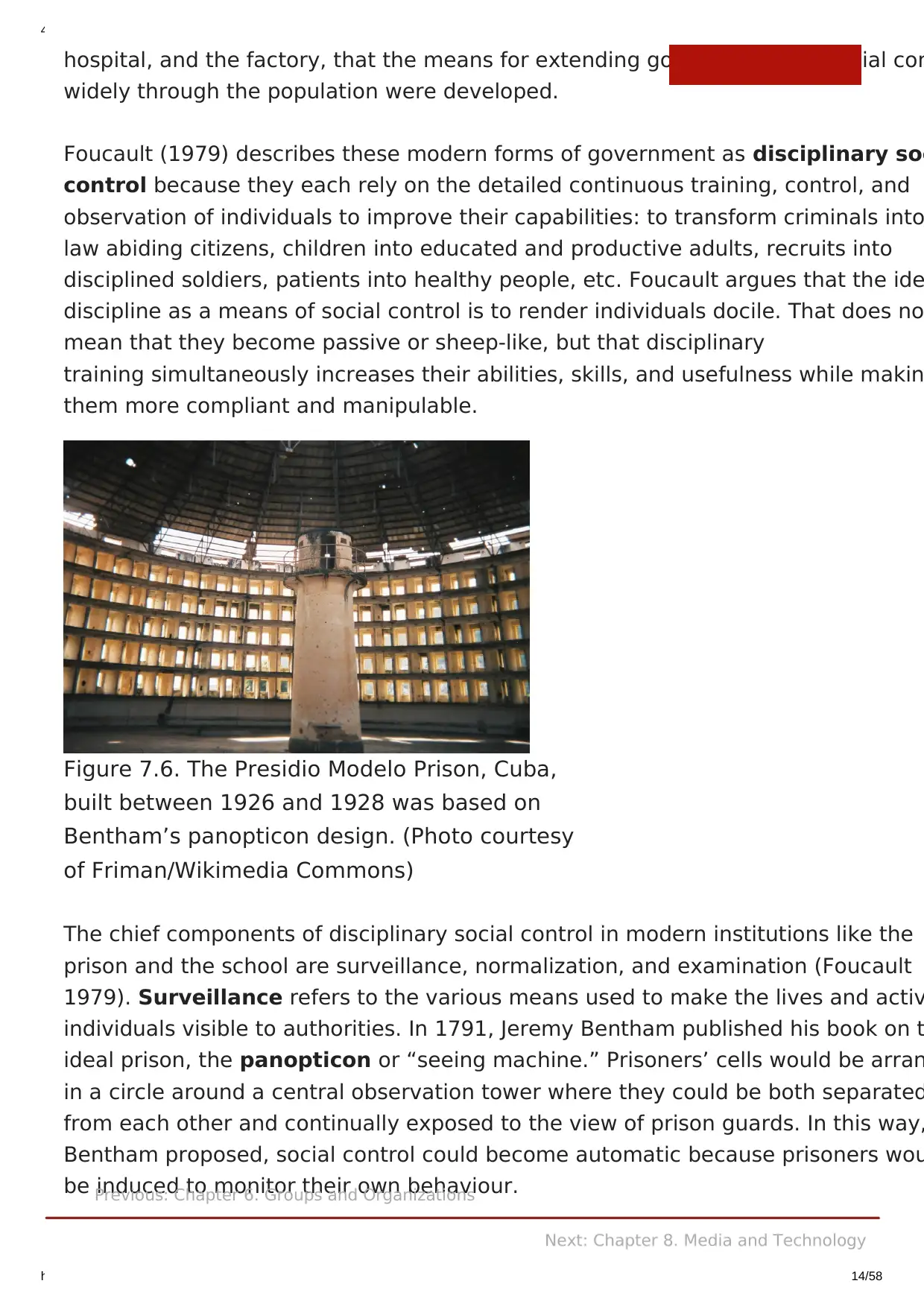

Figure 7.6. The Presidio Modelo Prison, Cuba,

built between 1926 and 1928 was based on

Bentham’s panopticon design. (Photo courtesy

of Friman/Wikimedia Commons)

The chief components of disciplinary social control in modern institutions like the

prison and the school are surveillance, normalization, and examination (Foucault

1979). Surveillance refers to the various means used to make the lives and activ

individuals visible to authorities. In 1791, Jeremy Bentham published his book on t

ideal prison, the panopticon or “seeing machine.” Prisoners’ cells would be arran

in a circle around a central observation tower where they could be both separated

from each other and continually exposed to the view of prison guards. In this way,

Bentham proposed, social control could become automatic because prisoners wou

be induced to monitor their own behaviour.Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 14/58

hospital, and the factory, that the means for extending government and social con

widely through the population were developed.

Foucault (1979) describes these modern forms of government as disciplinary soc

control because they each rely on the detailed continuous training, control, and

observation of individuals to improve their capabilities: to transform criminals into

law abiding citizens, children into educated and productive adults, recruits into

disciplined soldiers, patients into healthy people, etc. Foucault argues that the ide

discipline as a means of social control is to render individuals docile. That does no

mean that they become passive or sheep-like, but that disciplinary

training simultaneously increases their abilities, skills, and usefulness while makin

them more compliant and manipulable.

Figure 7.6. The Presidio Modelo Prison, Cuba,

built between 1926 and 1928 was based on

Bentham’s panopticon design. (Photo courtesy

of Friman/Wikimedia Commons)

The chief components of disciplinary social control in modern institutions like the

prison and the school are surveillance, normalization, and examination (Foucault

1979). Surveillance refers to the various means used to make the lives and activ

individuals visible to authorities. In 1791, Jeremy Bentham published his book on t

ideal prison, the panopticon or “seeing machine.” Prisoners’ cells would be arran

in a circle around a central observation tower where they could be both separated

from each other and continually exposed to the view of prison guards. In this way,

Bentham proposed, social control could become automatic because prisoners wou

be induced to monitor their own behaviour.Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 15/58

Similarly, in a school classroom, students sit in rows of desks immediately visible t

the teacher at the front of the room. In a store, shoppers can be observed through

way glass or video monitors. Contemporary surveillance expands the capacity for

observation using video or electronic forms of surveillance to render the activities

population visible. London, England, holds the dubious honour of being the most

surveilled city in the world. The city’s “ring of steel” is a security cordon in which o

half a million surveillance cameras are used to monitor and record trac moving in

and out of the city centre.

The practice of normalization refers to the way in which norms, such as the leve

math ability expected from a grade 2 student, are rst established and then used to

assess, dierentiate, and rank individuals according to their abilities (an A student,

student, C student, etc.). Individuals’ progress in developing their abilities, whethe

math skills, good prison behaviour, health outcomes, or other areas, is established

through constant comparisons with others and with natural and observable norms

Minor sanctions are used to continuously modify behaviour that does not comply w

correct conduct: rewards are applied for good behaviour and penalties for bad.

Periodic examinations through the use of tests in schools, medical examinations

hospitals, inspections in prisons, year-end reviews in the workplace, etc. bring

together surveillance and normalization in a way that enables each individual and

each individual’s abilities to be assessed, documented, and known by authorities.

the basis of examinations, individuals can be subjected to dierent disciplinary

procedures more suited to them. Gied children might receive an enriched

educational program, whereas poorer students might receive remedial lessons.

Foucault describes disciplinary social control as a key mechanism in creating a

normalizing society. The establishment of norms and the development of discip

procedures to correct deviance from norms become increasingly central to the

organization and operation of institutions from the 19th century onward. To the

degree that “natural” or sociological norms are used to govern our lives more than

laws and legal mechanisms, society can be said to be controlled

through normalization and disciplinary procedures. Whereas the use of formal law

courts, and the police come into play only when laws are broken, disciplinary

techniques enable the continuous and ongoing social control of an expanding rang

activities in our lives through surveillance, normalization, and examination. While

may never encounter the police for breaking a law, if we work, go to school, or end

in hospital, we are routinely subject to disciplinary control through most of the day

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 15/58

Similarly, in a school classroom, students sit in rows of desks immediately visible t

the teacher at the front of the room. In a store, shoppers can be observed through

way glass or video monitors. Contemporary surveillance expands the capacity for

observation using video or electronic forms of surveillance to render the activities

population visible. London, England, holds the dubious honour of being the most

surveilled city in the world. The city’s “ring of steel” is a security cordon in which o

half a million surveillance cameras are used to monitor and record trac moving in

and out of the city centre.

The practice of normalization refers to the way in which norms, such as the leve

math ability expected from a grade 2 student, are rst established and then used to

assess, dierentiate, and rank individuals according to their abilities (an A student,

student, C student, etc.). Individuals’ progress in developing their abilities, whethe

math skills, good prison behaviour, health outcomes, or other areas, is established

through constant comparisons with others and with natural and observable norms

Minor sanctions are used to continuously modify behaviour that does not comply w

correct conduct: rewards are applied for good behaviour and penalties for bad.

Periodic examinations through the use of tests in schools, medical examinations

hospitals, inspections in prisons, year-end reviews in the workplace, etc. bring

together surveillance and normalization in a way that enables each individual and

each individual’s abilities to be assessed, documented, and known by authorities.

the basis of examinations, individuals can be subjected to dierent disciplinary

procedures more suited to them. Gied children might receive an enriched

educational program, whereas poorer students might receive remedial lessons.

Foucault describes disciplinary social control as a key mechanism in creating a

normalizing society. The establishment of norms and the development of discip

procedures to correct deviance from norms become increasingly central to the

organization and operation of institutions from the 19th century onward. To the

degree that “natural” or sociological norms are used to govern our lives more than

laws and legal mechanisms, society can be said to be controlled

through normalization and disciplinary procedures. Whereas the use of formal law

courts, and the police come into play only when laws are broken, disciplinary

techniques enable the continuous and ongoing social control of an expanding rang

activities in our lives through surveillance, normalization, and examination. While

may never encounter the police for breaking a law, if we work, go to school, or end

in hospital, we are routinely subject to disciplinary control through most of the day

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 16/58

7.2. THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES ON DEVIA

Figure 7.7. Functionalists believe that deviance

plays an important role in society and can be

used to challenge people’s views. Protesters,

such as these PETA members, o en use this

method to draw attention to their cause. (Photo

courtesy of David Shankbone/ickr)

Why does deviance occur? How does it aect a society? Since the early days of

sociology, scholars have developed theories attempting to explain what deviance

crime mean to society. These theories can be grouped according to the three majo

sociological paradigms: functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and con ict theory.

Functionalism

Sociologists who follow the functionalist approach are concerned with how the

di erent elements of a society contribute to the whole. They view deviance as a ke

component of a functioning society. Social disorganization theory, strain theory, an

cultural deviance theory represent three functionalist perspectives on deviance

society.

Émile Durkheim: The Essential Nature of

Deviance

Émile Durkheim believed that deviance is a necessary part of a successful society.

way deviance is functional, he argued, is that it challenges people’s present views

(1893). For instance, when black students across the United States participated in

ins” during the civil rights movement, they challenged society’s notions of

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 16/58

7.2. THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES ON DEVIA

Figure 7.7. Functionalists believe that deviance

plays an important role in society and can be

used to challenge people’s views. Protesters,

such as these PETA members, o en use this

method to draw attention to their cause. (Photo

courtesy of David Shankbone/ickr)

Why does deviance occur? How does it aect a society? Since the early days of

sociology, scholars have developed theories attempting to explain what deviance

crime mean to society. These theories can be grouped according to the three majo

sociological paradigms: functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and con ict theory.

Functionalism

Sociologists who follow the functionalist approach are concerned with how the

di erent elements of a society contribute to the whole. They view deviance as a ke

component of a functioning society. Social disorganization theory, strain theory, an

cultural deviance theory represent three functionalist perspectives on deviance

society.

Émile Durkheim: The Essential Nature of

Deviance

Émile Durkheim believed that deviance is a necessary part of a successful society.

way deviance is functional, he argued, is that it challenges people’s present views

(1893). For instance, when black students across the United States participated in

ins” during the civil rights movement, they challenged society’s notions of

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

Increase Font Size

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

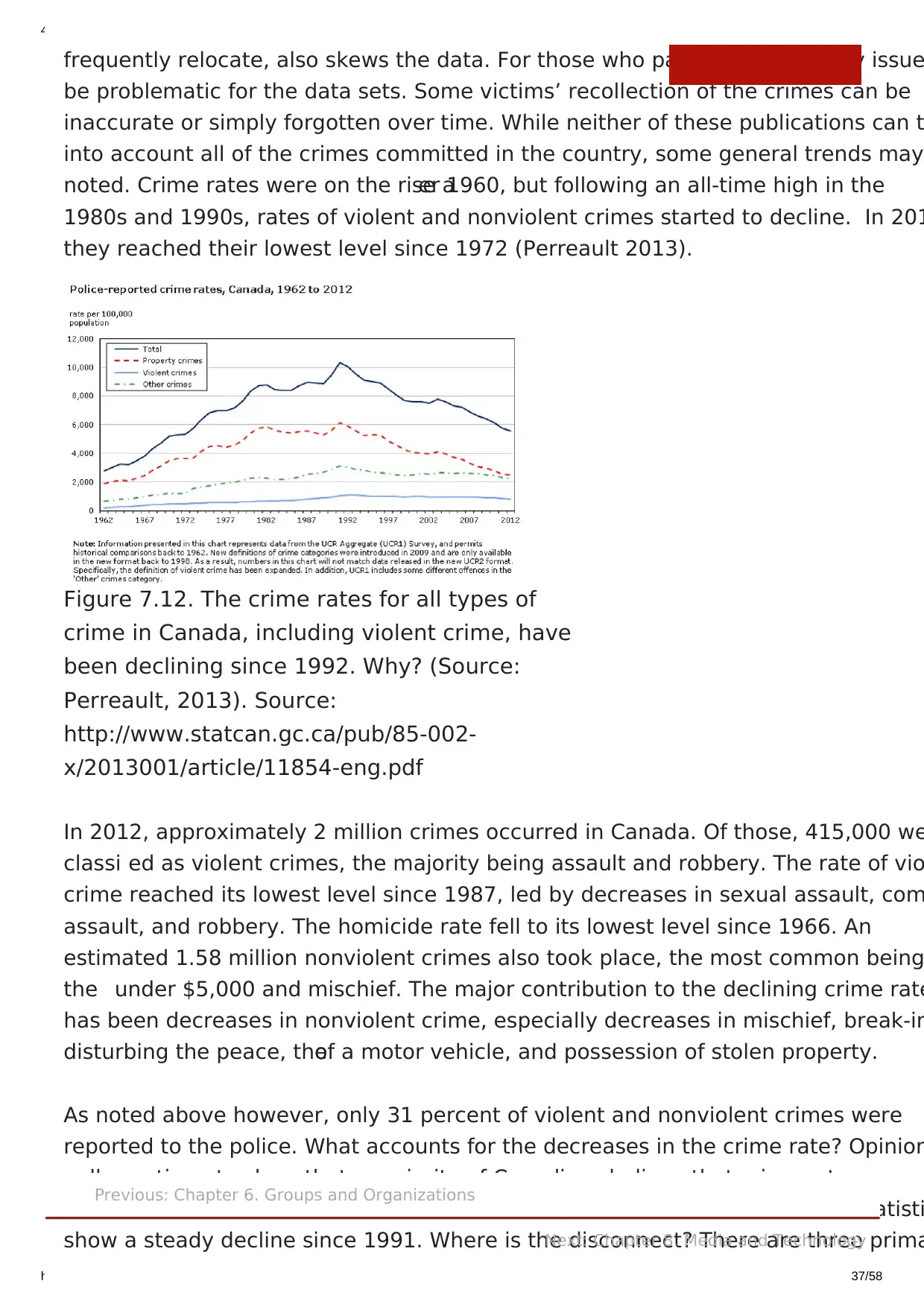

4/4/2020 Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control – Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/chapter/chapter7-deviance-crime-and-social-control/ 17/58

segregation. Moreover, Durkheim noted, when deviance is punished, it rearms

currently held social norms, which also contributes to society (1893). Seeing a stu

given a detention for skipping class reminds other high schoolers that playing hoo

isn’t allowed and that they, too, could get a detention.

Social Disorganization Theory

Developed by researchers at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, so

disorganization theory asserts that crime is most likely to occur in communities

weak social ties and the absence of social control. In a certain way, this is the opp

of Durkheim’s thesis. Rather than deviance being a force that reinforces moral and

social solidarity, it is the absence of moral and social solidarity that provides the

conditions for social deviance to emerge.

Early Chicago School sociologists used an ecological model to map the zones in

Chicago where high levels of social problem were concentrated. During this period

Chicago was experiencing a long period of economic growth, urban expansion, and

foreign immigration. They were particularly interested in thezones of transition

between established working class neighbourhoods and the manufacturing

district. The city’s poorest residents tended to live in these transitional zones, whe

there was a mixture of races, immigrant ethnic groups, and non-English languages

and a high rate of in ux as people moved in and out. They proposed that these zon

were particularly prone to social disorder because the residents had not yet

assimilated to the American way of life. When they did assimilate they moved out,

making it di cult for a stable social ecology to become established there.

Figure 7.8. Proponents of social

disorganization theory believe that

individuals who grow up in

impoverished areas are more likely

Previous: Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Next: Chapter 8. Media and Technology

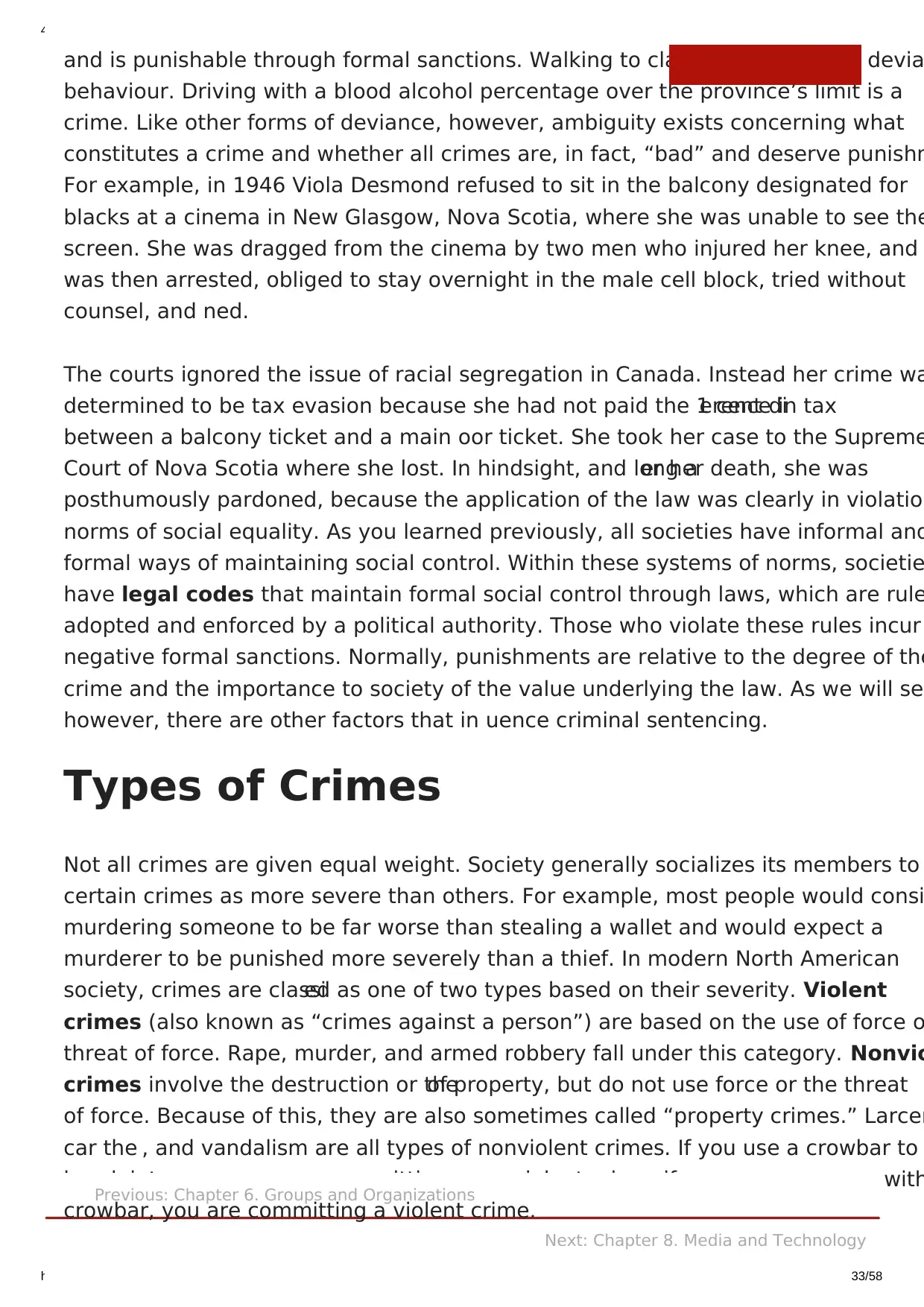

Increase Font Size