Dietary Sources of Energy, Solid Fats, and Added Sugars Among Children and Adolescents in the United States

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/30

|14

|7454

|323

AI Summary

This research identifies top dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among 2–18 year olds in the United States. The top sources of energy for 2–18 year olds were grain desserts, pizza, and soda. Identifying top sources of energy and empty calories can provide targets for changes in the marketplace and food environment.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Dietary Sources of Energy, Solid Fats, and Added Sugars

Among Children and Adolescents in the United States

Jill Reedy, PhD, MPH, RD and

Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD

Susan M. Krebs-Smith, PhD, MPH, RD

Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD

Abstract

Objective—The objective of this research was to identify top dietary sources of energy, solid

fats, and added sugars among 2–18 year olds in the United States.

Methods—Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a

cross-sectional study, were used to examine food sources (percentage contribution and mean

intake with standard errors) of total energy (2005–06) and calories from solid fats and added

sugars (2003–04). Differences were investigated by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and family income,

and the consumption of empty calories—defined as the sum of calories from solid fats and added

sugars—was compared with the corresponding discretionary calorie allowance.

Results—The top sources of energy for 2–18 year olds were grain desserts (138 kcal/day), pizza

(136 kcal), and soda (118 kcal). Sugar-sweetened beverages (soda and fruit drinks combined)

provided 173 kcal/day. Major contributors varied by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and income. Nearly

40% of total calories consumed (798 kcal/day of 2027 kcal) by 2–18 year olds were in the form of

empty calories (433 kcal from solid fat and 365 kcal from added sugars). Consumption of empty

calories far exceeded the corresponding discretionary calorie allowance for all sex-age groups

(which range from 8–20%). Half of empty calories came from six foods: soda, fruit drinks, dairy

desserts, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk.

Conclusion—There is an overlap between the major sources of energy and empty calories: soda,

grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk. The landscape of choices available to children and

adolescents must change to provide fewer unhealthy foods and more healthy foods with fewer

calories. Identifying top sources of energy and empty calories can provide targets for changes in

the marketplace and food environment. However, product reformulation alone is not sufficient—

the flow of empty calories into the food supply must be reduced.

Introduction

In the United States (US) today, over 23 million children and adolescents are overweight or

obese (1,2). Excess body weight, poor diet, and sedentary behavior have been associated

with an increased risk of many chronic diseases, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, type

2 diabetes, as well as depression, poor self-esteem, and associated quality of life issues (3,4).

Author responsible for correspondence/reprint requests: Jill Reedy, PhD, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences,

National Cancer Institute, 6130 Executive Blvd. MSC 7344, Bethesda, MD 20892, 301-594-6605, 301-435-3710 (FAX),

reedyj@mail.nih.gov.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our

customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of

the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be

discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

Published in final edited form as:

J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 October ; 110(10): 1477–1484. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.010.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Among Children and Adolescents in the United States

Jill Reedy, PhD, MPH, RD and

Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD

Susan M. Krebs-Smith, PhD, MPH, RD

Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD

Abstract

Objective—The objective of this research was to identify top dietary sources of energy, solid

fats, and added sugars among 2–18 year olds in the United States.

Methods—Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a

cross-sectional study, were used to examine food sources (percentage contribution and mean

intake with standard errors) of total energy (2005–06) and calories from solid fats and added

sugars (2003–04). Differences were investigated by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and family income,

and the consumption of empty calories—defined as the sum of calories from solid fats and added

sugars—was compared with the corresponding discretionary calorie allowance.

Results—The top sources of energy for 2–18 year olds were grain desserts (138 kcal/day), pizza

(136 kcal), and soda (118 kcal). Sugar-sweetened beverages (soda and fruit drinks combined)

provided 173 kcal/day. Major contributors varied by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and income. Nearly

40% of total calories consumed (798 kcal/day of 2027 kcal) by 2–18 year olds were in the form of

empty calories (433 kcal from solid fat and 365 kcal from added sugars). Consumption of empty

calories far exceeded the corresponding discretionary calorie allowance for all sex-age groups

(which range from 8–20%). Half of empty calories came from six foods: soda, fruit drinks, dairy

desserts, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk.

Conclusion—There is an overlap between the major sources of energy and empty calories: soda,

grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk. The landscape of choices available to children and

adolescents must change to provide fewer unhealthy foods and more healthy foods with fewer

calories. Identifying top sources of energy and empty calories can provide targets for changes in

the marketplace and food environment. However, product reformulation alone is not sufficient—

the flow of empty calories into the food supply must be reduced.

Introduction

In the United States (US) today, over 23 million children and adolescents are overweight or

obese (1,2). Excess body weight, poor diet, and sedentary behavior have been associated

with an increased risk of many chronic diseases, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, type

2 diabetes, as well as depression, poor self-esteem, and associated quality of life issues (3,4).

Author responsible for correspondence/reprint requests: Jill Reedy, PhD, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences,

National Cancer Institute, 6130 Executive Blvd. MSC 7344, Bethesda, MD 20892, 301-594-6605, 301-435-3710 (FAX),

reedyj@mail.nih.gov.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our

customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of

the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be

discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

Published in final edited form as:

J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 October ; 110(10): 1477–1484. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.010.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Although overweight and obesity are found in all subpopulations, the burden is particularly

striking among children, adolescents, and underserved populations. Children and

adolescents are now experiencing weight-related chronic diseases once seen only among

adults. Additionally, the prevalence of overweight is higher among adolescents compared to

younger children, Mexican-American boys compared to non-Hispanic black or white boys,

and Mexican-American and Non-Hispanic black girls compared to non-Hispanic white girls

(2).

Multiple factors influence overweight and obesity rates, but ultimately, an imbalance

between energy consumed and energy expended is the determining factor. The current

environment (including food stores, restaurants, schools, and worksites) and customs

surrounding food in the US have been labeled “obesogenic” and “toxic” due to the

contributions made to this imbalance by large portion sizes, snacking, away-from-home

meals, and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (5–7). Ironically, in a food

environment that supplies an overabundance of energy, there are too few vegetables, whole

grains, fruits, and milk products (8). Therefore, US children and adolescents do not always

consume the types and amounts of food they need to support an active, healthy lifestyle (9).

Recommendations for fruits, vegetables, whole grains and other nutrient-bearing food

groups are available in the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americansand MyPyramid (10,11).

These resources also define the concept of a “discretionary calorie allowance” to provide

limits for excess calories from consumption of food groups beyond recommended amounts

andall calories from solid fats, alcoholic beverages, and added sugars (SoFAAS). These

SoFAAS represent empty calories, or sources of energy with virtually no nutritional value,

and have been examined previously in relation to discretionary calorie allowances (12).

Although the discretionary calorie allowance should be considered an upper bound on

consumption of calories from SoFAAS, such intakes far exceed the recommended

discretionary calorie allowances across all sex-age groups in the US population (13). The

purpose of this paper is to identify the top as-eaten food sources of energy, solid fats, and

added sugars among US children and adolescents. “As-eaten” food sources include

composite foods (e.g., cookies), and mixed dishes (e.g., pizza), as well as discrete foods

(e.g., milk or apples).

Methods

Data source and sample

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a cross-

sectional study, were used to examine food sources of total energy (2005–06) and calories

from solid fats and added sugars (2003–04). NHANES is a nationally representative survey

with a complex multistage, stratified probability sample. Trained interviewers conducted in-

person 24-hour dietary recalls with all eligible persons, using automated data collection

systems that included multiple passes. Survey participants ages 12 years and older

completed the dietary interview on their own, proxy-assisted interviews were conducted

with children ages 6 to 11 years, and proxy respondents reported for children younger than

age 5 years (14). The NHANES protocol was approved by the National Center for Health

Statistics Research Ethics Review Board, Hyattsville, Maryland, and all participants

provided informed consent. Further information regarding the design of the NHANES,

including sampling and weighting procedures, can be found at

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm.

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 2

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

striking among children, adolescents, and underserved populations. Children and

adolescents are now experiencing weight-related chronic diseases once seen only among

adults. Additionally, the prevalence of overweight is higher among adolescents compared to

younger children, Mexican-American boys compared to non-Hispanic black or white boys,

and Mexican-American and Non-Hispanic black girls compared to non-Hispanic white girls

(2).

Multiple factors influence overweight and obesity rates, but ultimately, an imbalance

between energy consumed and energy expended is the determining factor. The current

environment (including food stores, restaurants, schools, and worksites) and customs

surrounding food in the US have been labeled “obesogenic” and “toxic” due to the

contributions made to this imbalance by large portion sizes, snacking, away-from-home

meals, and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (5–7). Ironically, in a food

environment that supplies an overabundance of energy, there are too few vegetables, whole

grains, fruits, and milk products (8). Therefore, US children and adolescents do not always

consume the types and amounts of food they need to support an active, healthy lifestyle (9).

Recommendations for fruits, vegetables, whole grains and other nutrient-bearing food

groups are available in the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americansand MyPyramid (10,11).

These resources also define the concept of a “discretionary calorie allowance” to provide

limits for excess calories from consumption of food groups beyond recommended amounts

andall calories from solid fats, alcoholic beverages, and added sugars (SoFAAS). These

SoFAAS represent empty calories, or sources of energy with virtually no nutritional value,

and have been examined previously in relation to discretionary calorie allowances (12).

Although the discretionary calorie allowance should be considered an upper bound on

consumption of calories from SoFAAS, such intakes far exceed the recommended

discretionary calorie allowances across all sex-age groups in the US population (13). The

purpose of this paper is to identify the top as-eaten food sources of energy, solid fats, and

added sugars among US children and adolescents. “As-eaten” food sources include

composite foods (e.g., cookies), and mixed dishes (e.g., pizza), as well as discrete foods

(e.g., milk or apples).

Methods

Data source and sample

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a cross-

sectional study, were used to examine food sources of total energy (2005–06) and calories

from solid fats and added sugars (2003–04). NHANES is a nationally representative survey

with a complex multistage, stratified probability sample. Trained interviewers conducted in-

person 24-hour dietary recalls with all eligible persons, using automated data collection

systems that included multiple passes. Survey participants ages 12 years and older

completed the dietary interview on their own, proxy-assisted interviews were conducted

with children ages 6 to 11 years, and proxy respondents reported for children younger than

age 5 years (14). The NHANES protocol was approved by the National Center for Health

Statistics Research Ethics Review Board, Hyattsville, Maryland, and all participants

provided informed consent. Further information regarding the design of the NHANES,

including sampling and weighting procedures, can be found at

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm.

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 2

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

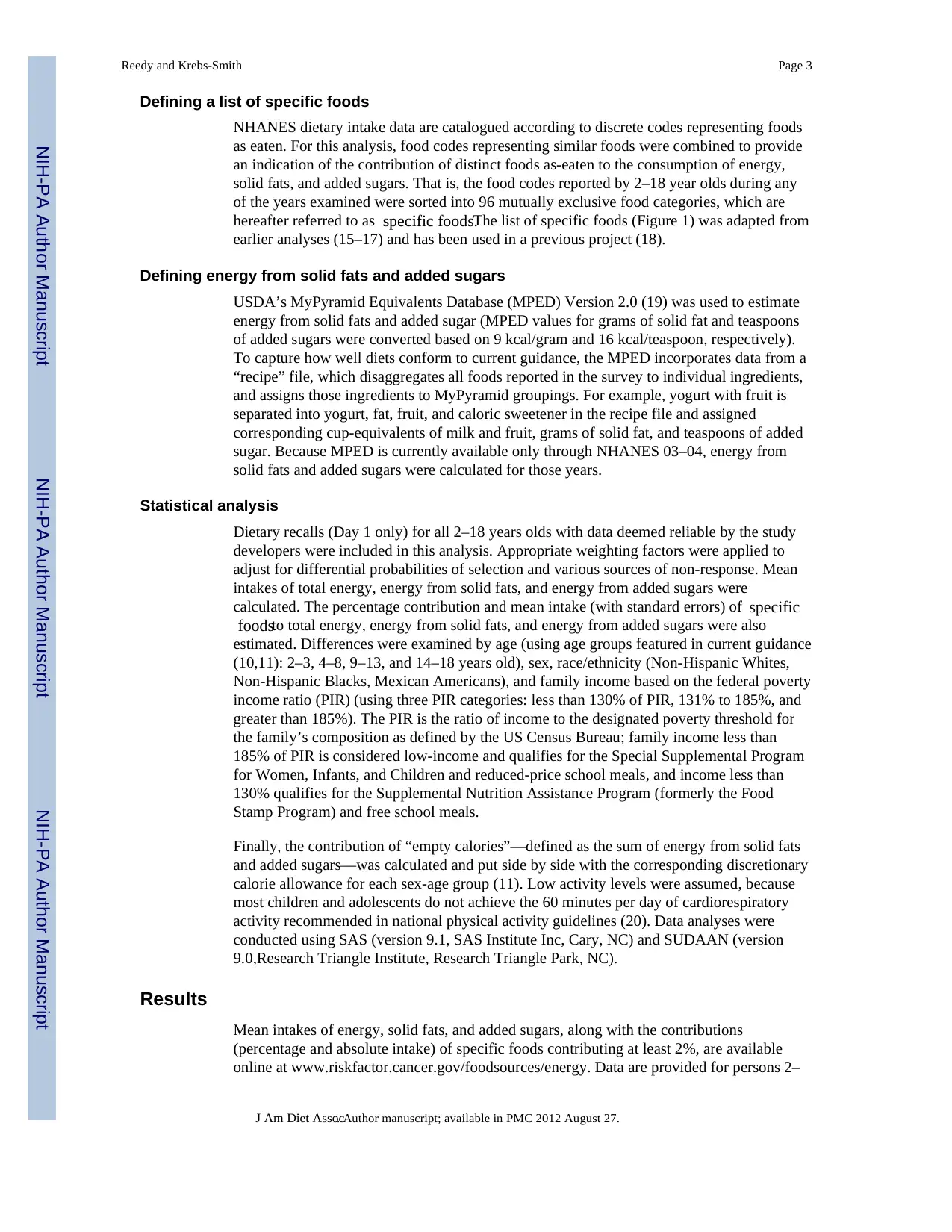

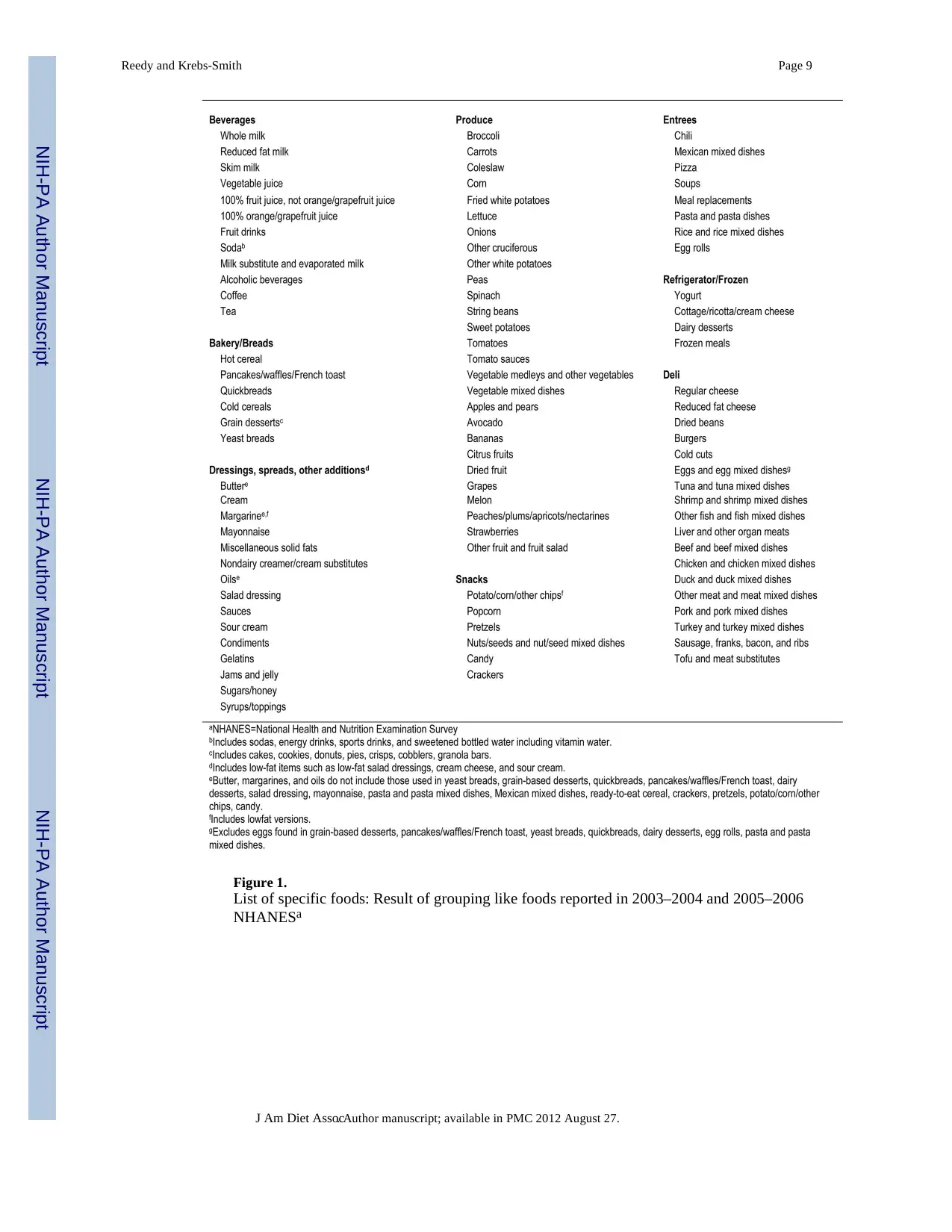

Defining a list of specific foods

NHANES dietary intake data are catalogued according to discrete codes representing foods

as eaten. For this analysis, food codes representing similar foods were combined to provide

an indication of the contribution of distinct foods as-eaten to the consumption of energy,

solid fats, and added sugars. That is, the food codes reported by 2–18 year olds during any

of the years examined were sorted into 96 mutually exclusive food categories, which are

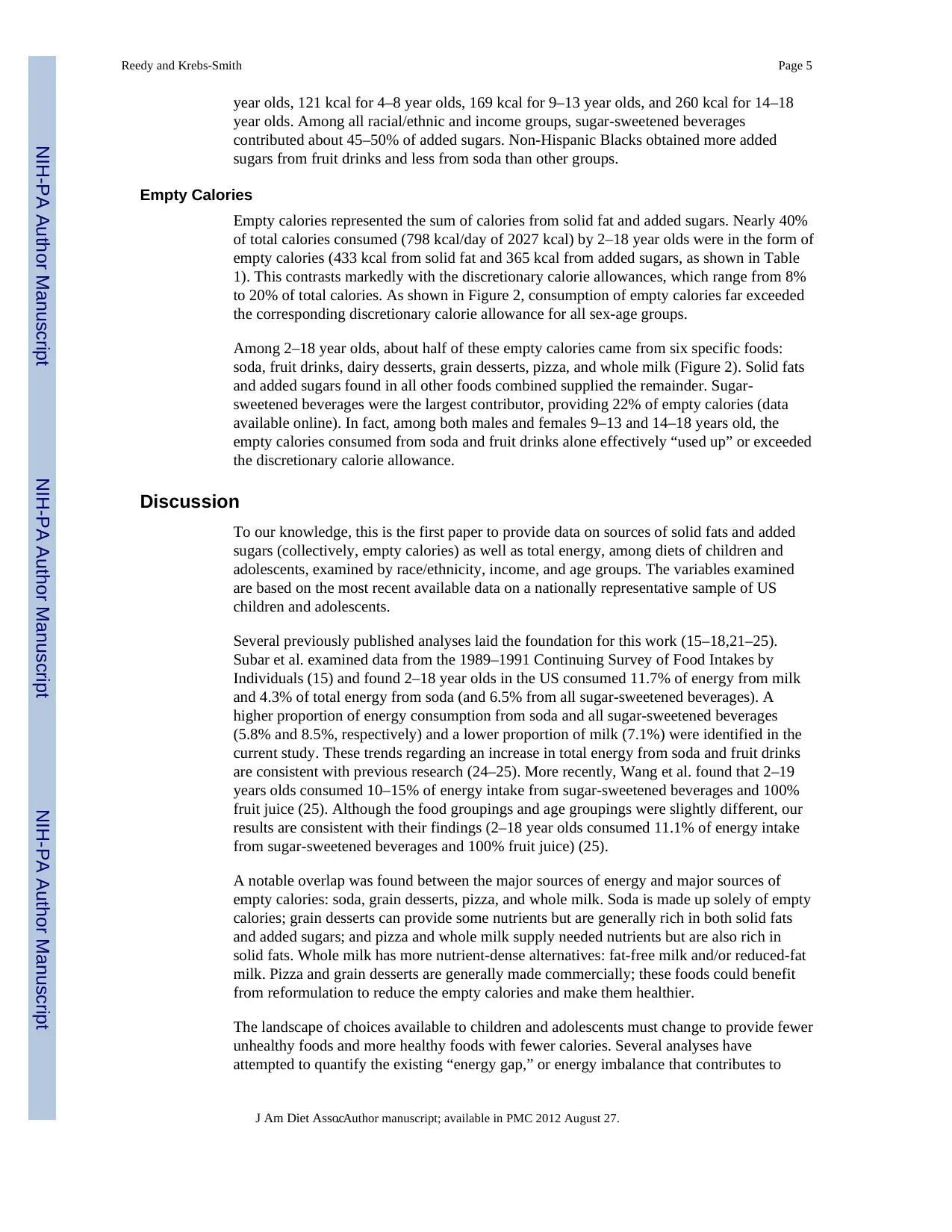

hereafter referred to as specific foods.The list of specific foods (Figure 1) was adapted from

earlier analyses (15–17) and has been used in a previous project (18).

Defining energy from solid fats and added sugars

USDA’s MyPyramid Equivalents Database (MPED) Version 2.0 (19) was used to estimate

energy from solid fats and added sugar (MPED values for grams of solid fat and teaspoons

of added sugars were converted based on 9 kcal/gram and 16 kcal/teaspoon, respectively).

To capture how well diets conform to current guidance, the MPED incorporates data from a

“recipe” file, which disaggregates all foods reported in the survey to individual ingredients,

and assigns those ingredients to MyPyramid groupings. For example, yogurt with fruit is

separated into yogurt, fat, fruit, and caloric sweetener in the recipe file and assigned

corresponding cup-equivalents of milk and fruit, grams of solid fat, and teaspoons of added

sugar. Because MPED is currently available only through NHANES 03–04, energy from

solid fats and added sugars were calculated for those years.

Statistical analysis

Dietary recalls (Day 1 only) for all 2–18 years olds with data deemed reliable by the study

developers were included in this analysis. Appropriate weighting factors were applied to

adjust for differential probabilities of selection and various sources of non-response. Mean

intakes of total energy, energy from solid fats, and energy from added sugars were

calculated. The percentage contribution and mean intake (with standard errors) of specific

foodsto total energy, energy from solid fats, and energy from added sugars were also

estimated. Differences were examined by age (using age groups featured in current guidance

(10,11): 2–3, 4–8, 9–13, and 14–18 years old), sex, race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic Whites,

Non-Hispanic Blacks, Mexican Americans), and family income based on the federal poverty

income ratio (PIR) (using three PIR categories: less than 130% of PIR, 131% to 185%, and

greater than 185%). The PIR is the ratio of income to the designated poverty threshold for

the family’s composition as defined by the US Census Bureau; family income less than

185% of PIR is considered low-income and qualifies for the Special Supplemental Program

for Women, Infants, and Children and reduced-price school meals, and income less than

130% qualifies for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly the Food

Stamp Program) and free school meals.

Finally, the contribution of “empty calories”—defined as the sum of energy from solid fats

and added sugars—was calculated and put side by side with the corresponding discretionary

calorie allowance for each sex-age group (11). Low activity levels were assumed, because

most children and adolescents do not achieve the 60 minutes per day of cardiorespiratory

activity recommended in national physical activity guidelines (20). Data analyses were

conducted using SAS (version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and SUDAAN (version

9.0,Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Results

Mean intakes of energy, solid fats, and added sugars, along with the contributions

(percentage and absolute intake) of specific foods contributing at least 2%, are available

online at www.riskfactor.cancer.gov/foodsources/energy. Data are provided for persons 2–

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 3

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NHANES dietary intake data are catalogued according to discrete codes representing foods

as eaten. For this analysis, food codes representing similar foods were combined to provide

an indication of the contribution of distinct foods as-eaten to the consumption of energy,

solid fats, and added sugars. That is, the food codes reported by 2–18 year olds during any

of the years examined were sorted into 96 mutually exclusive food categories, which are

hereafter referred to as specific foods.The list of specific foods (Figure 1) was adapted from

earlier analyses (15–17) and has been used in a previous project (18).

Defining energy from solid fats and added sugars

USDA’s MyPyramid Equivalents Database (MPED) Version 2.0 (19) was used to estimate

energy from solid fats and added sugar (MPED values for grams of solid fat and teaspoons

of added sugars were converted based on 9 kcal/gram and 16 kcal/teaspoon, respectively).

To capture how well diets conform to current guidance, the MPED incorporates data from a

“recipe” file, which disaggregates all foods reported in the survey to individual ingredients,

and assigns those ingredients to MyPyramid groupings. For example, yogurt with fruit is

separated into yogurt, fat, fruit, and caloric sweetener in the recipe file and assigned

corresponding cup-equivalents of milk and fruit, grams of solid fat, and teaspoons of added

sugar. Because MPED is currently available only through NHANES 03–04, energy from

solid fats and added sugars were calculated for those years.

Statistical analysis

Dietary recalls (Day 1 only) for all 2–18 years olds with data deemed reliable by the study

developers were included in this analysis. Appropriate weighting factors were applied to

adjust for differential probabilities of selection and various sources of non-response. Mean

intakes of total energy, energy from solid fats, and energy from added sugars were

calculated. The percentage contribution and mean intake (with standard errors) of specific

foodsto total energy, energy from solid fats, and energy from added sugars were also

estimated. Differences were examined by age (using age groups featured in current guidance

(10,11): 2–3, 4–8, 9–13, and 14–18 years old), sex, race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic Whites,

Non-Hispanic Blacks, Mexican Americans), and family income based on the federal poverty

income ratio (PIR) (using three PIR categories: less than 130% of PIR, 131% to 185%, and

greater than 185%). The PIR is the ratio of income to the designated poverty threshold for

the family’s composition as defined by the US Census Bureau; family income less than

185% of PIR is considered low-income and qualifies for the Special Supplemental Program

for Women, Infants, and Children and reduced-price school meals, and income less than

130% qualifies for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly the Food

Stamp Program) and free school meals.

Finally, the contribution of “empty calories”—defined as the sum of energy from solid fats

and added sugars—was calculated and put side by side with the corresponding discretionary

calorie allowance for each sex-age group (11). Low activity levels were assumed, because

most children and adolescents do not achieve the 60 minutes per day of cardiorespiratory

activity recommended in national physical activity guidelines (20). Data analyses were

conducted using SAS (version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and SUDAAN (version

9.0,Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Results

Mean intakes of energy, solid fats, and added sugars, along with the contributions

(percentage and absolute intake) of specific foods contributing at least 2%, are available

online at www.riskfactor.cancer.gov/foodsources/energy. Data are provided for persons 2–

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 3

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

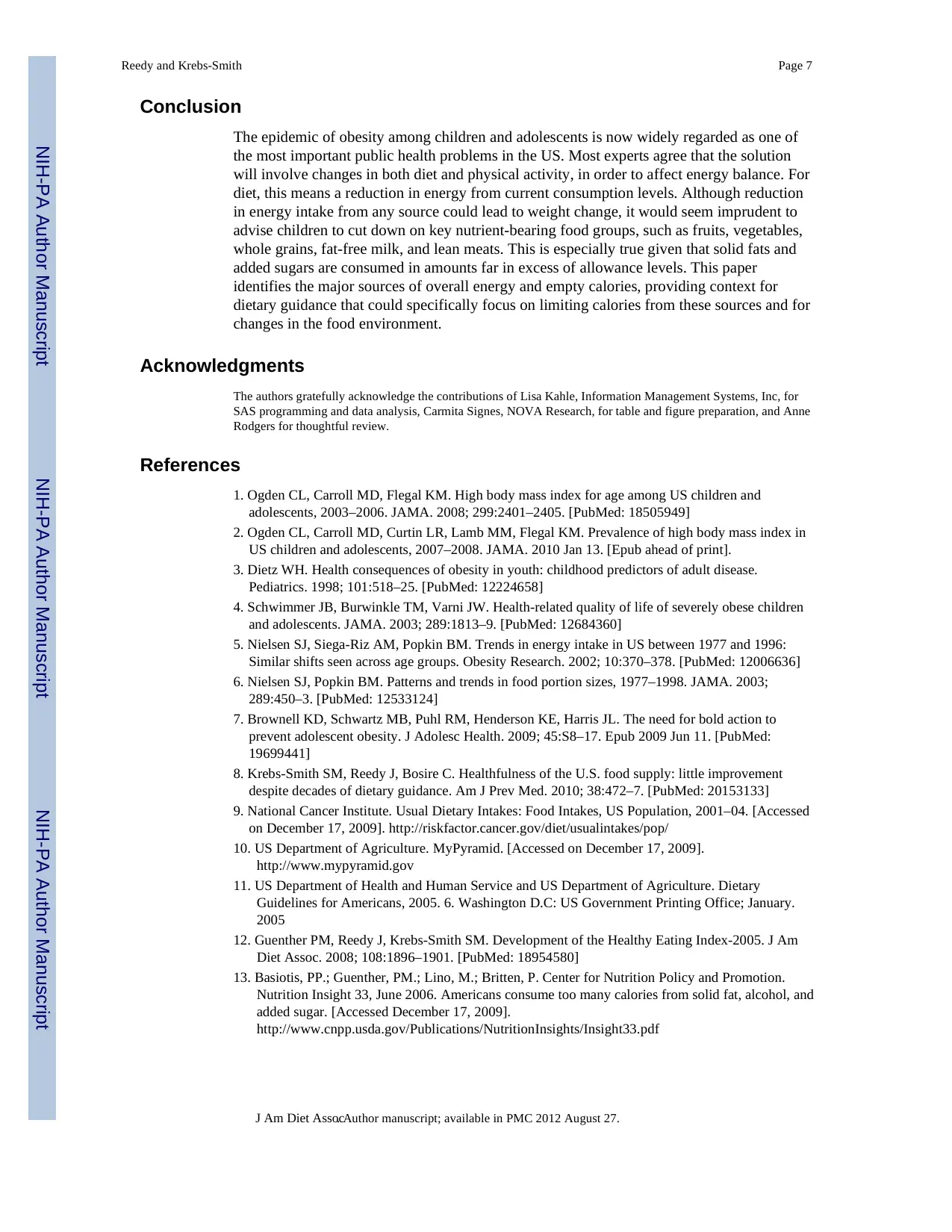

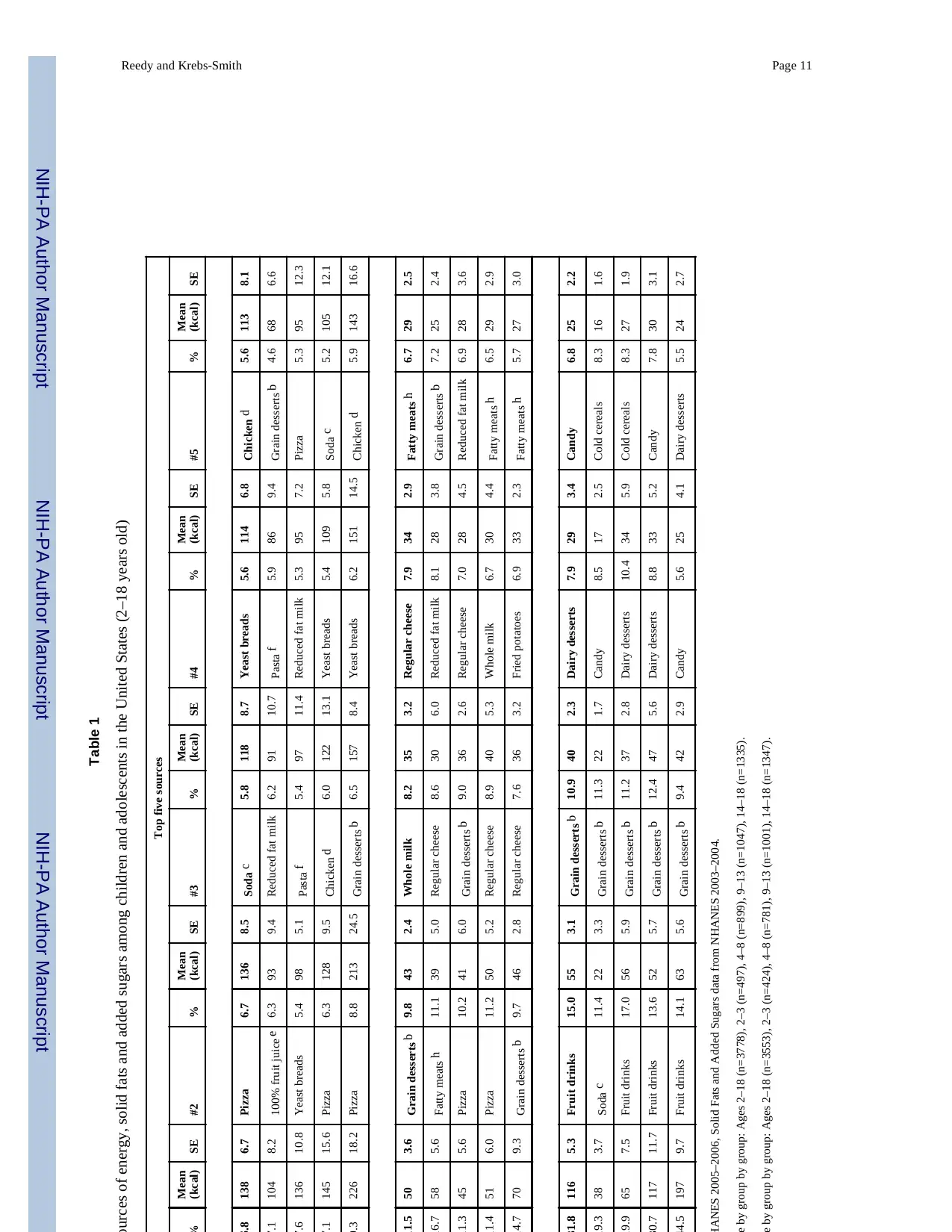

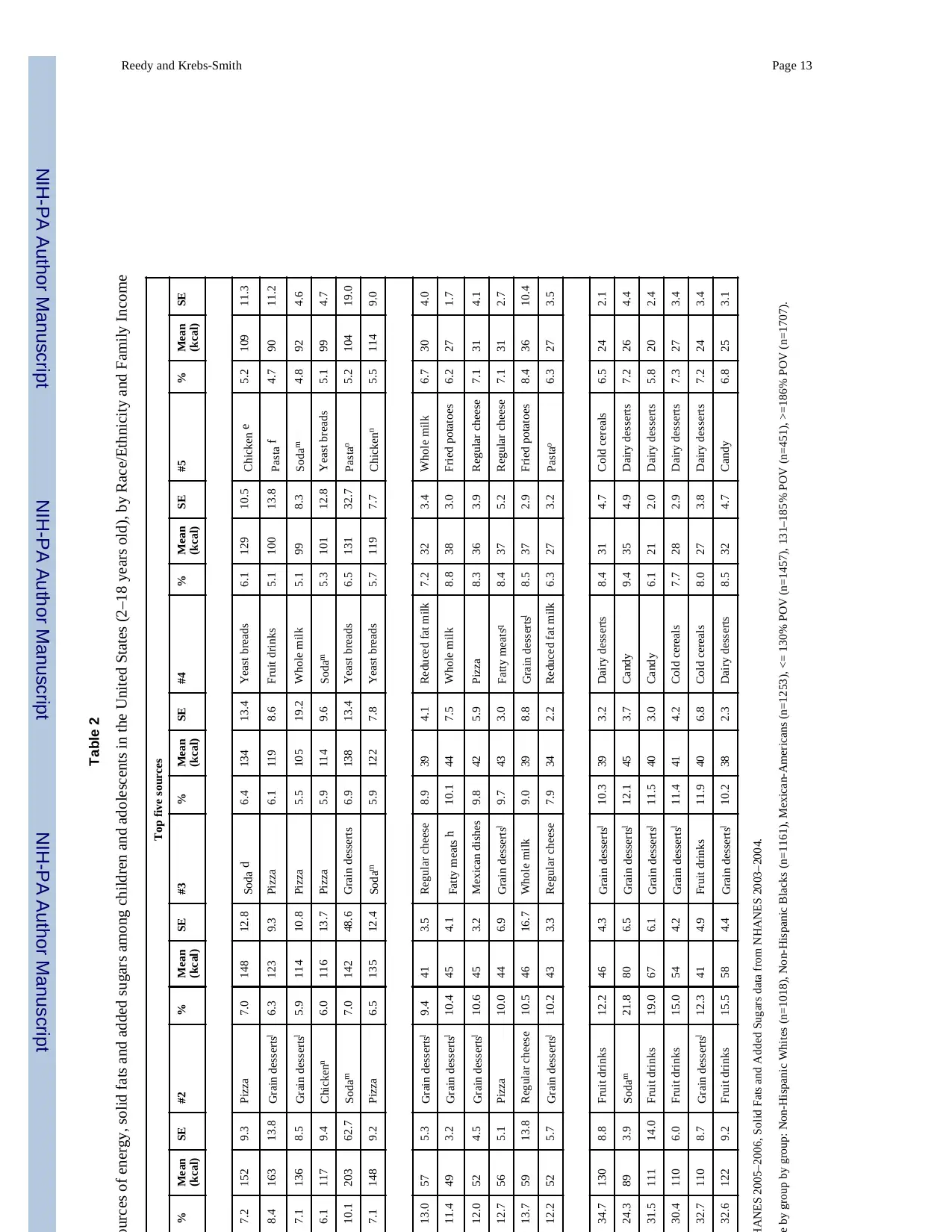

18 years and by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and income level. For ease of presentation in this

paper, mean intakes of energy, solid fats, and added sugars, and results from the top five

sources are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 2.

Energy

The top five sources of energy for 2–18 years olds were grain desserts (cakes, cookies,

donuts, pies, crisps, cobblers, and granola bars) (138 kcal/day), pizza (136 kcal), soda (118

kcal), yeast breads (114 kcal), and chicken and chicken mixed dishes (113 kcal) (Table 1).

These foods each contributed more than 5% to energy intake, or more than 100 kcal per

child per day. Combining related specific foods within the beverage category, children and

adolescents consumed 173 kcal from sugar-sweetened beverages (combining soda and fruit

drinks) and 146 kcal from milk (combining whole and reduced-fat versions) (data for fruit

drinks and reduced fat milk do not always appear in the top five sources, so these data are

available online).

These major contributors varied by age group. For example, the top five sources of energy

for 2–3 years olds included whole milk (104 kcal/day), fruit juice (93 kcal), reduced-fat milk

(91 kcal), and pasta and pasta dishes (86 kcal). Pasta and reduced-fat milk were also among

the top five sources of energy for 4–8 years olds (97 and 95 kcal, respectively).

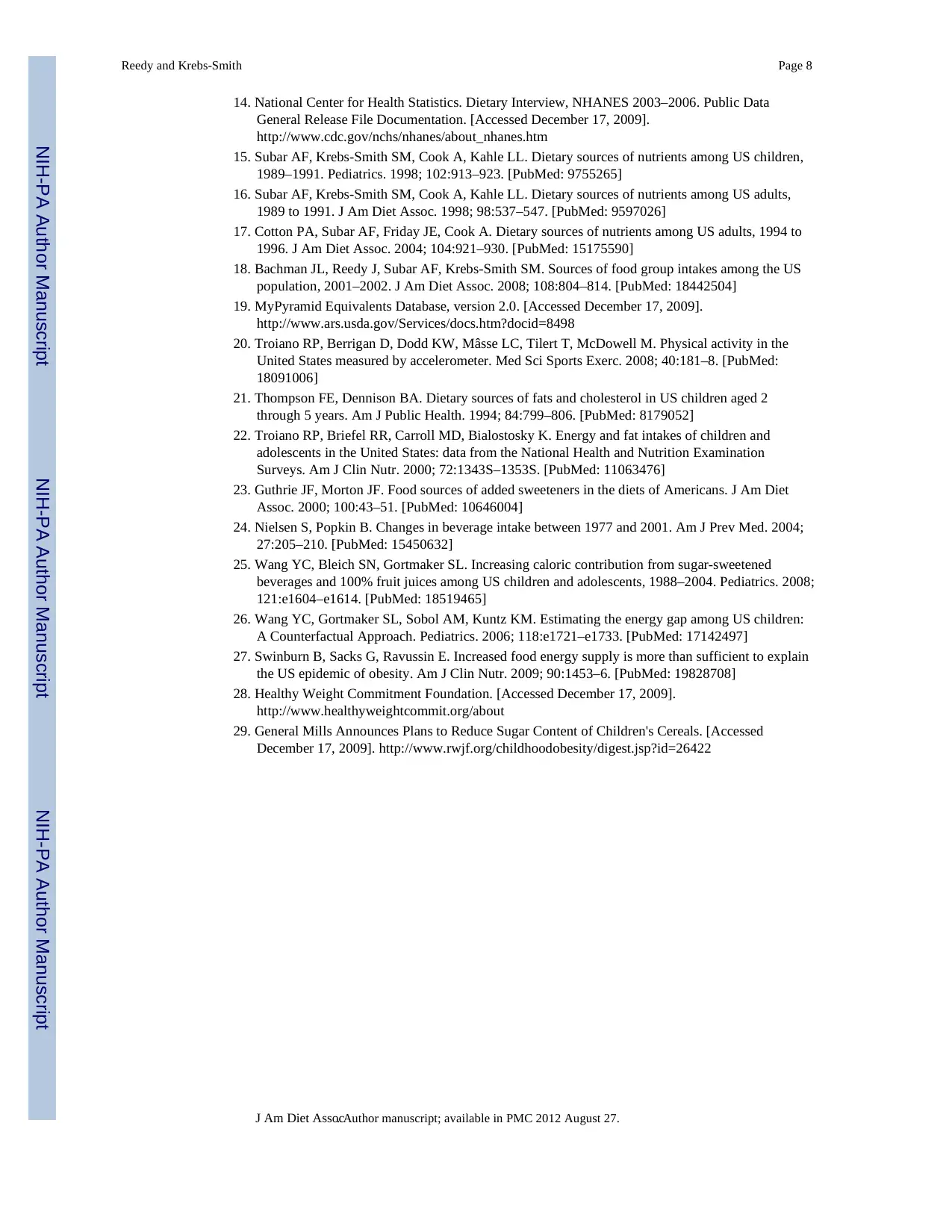

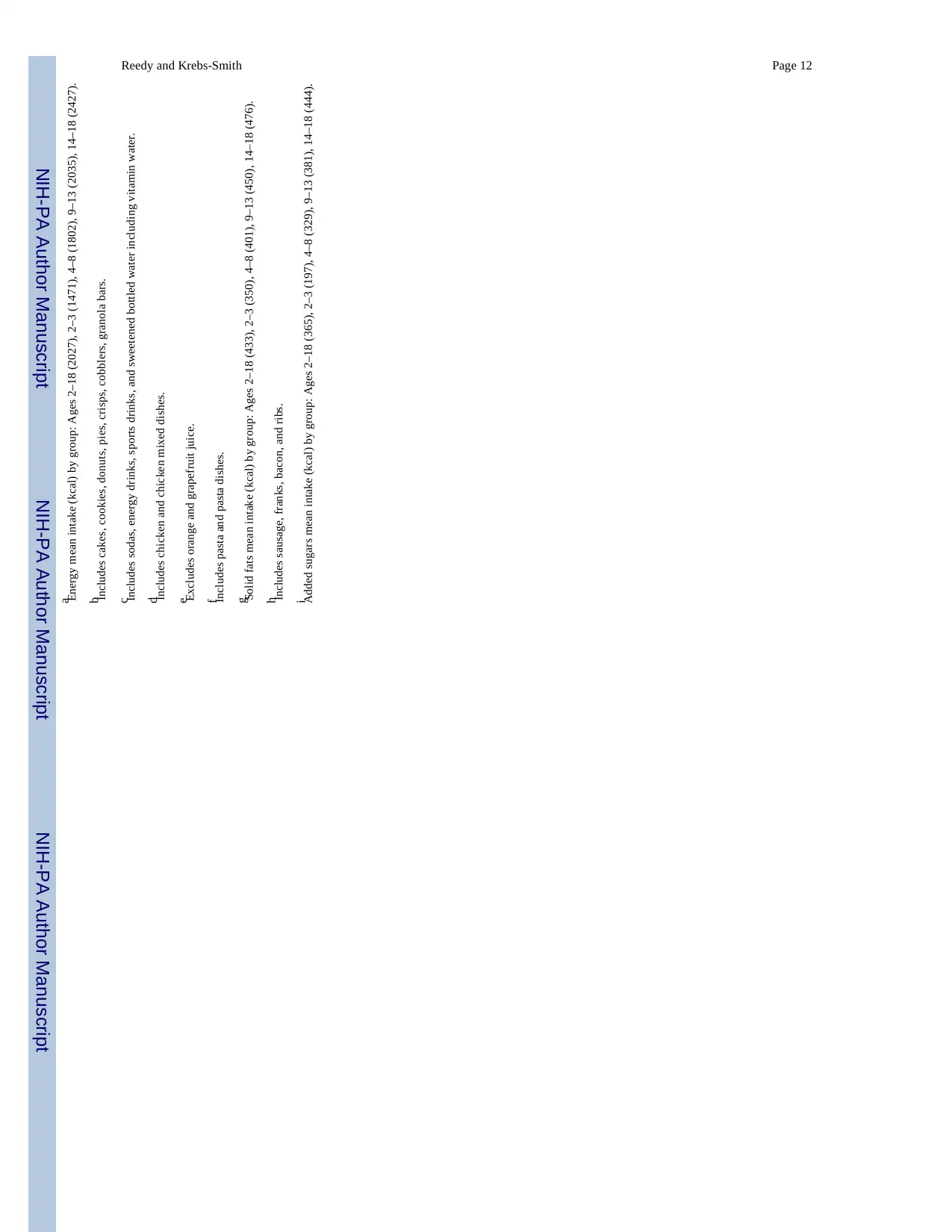

The top contributors of energy also varied by race/ethnicity (Table 2). For example, major

contributors for 2–18 year old Non-Hispanic Blacks included fruit drinks (100 kcal/day) and

pasta and pasta dishes (90 kcal), while Mexican-Americans’ top sources included Mexican

mixed dishes (136 kcal) and whole milk (99 kcal). Non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites

consumed more energy from sugar-sweetened beverages (combining soda and fruit drinks)

than from milk (combining all milks), whereas Mexican-Americans consumed more energy

from milk than from sugar-sweetened beverages (Table 2 and online tables). The top five

sources of energy by income were consistent across income levels, but varied in ranking

order.

Solid Fats

The average daily intake of energy from solid fats among 2–18 year olds is 433 kcal (Table

1). The major sources of solid fat were pizza (50 kcal/day from solid fat), grain desserts (43

kcal), whole milk (35 kcal), regular cheese (34 kcal), and fatty meats (29 kcal). This list

varied by age group, with younger children obtaining a greater share of their solid fat from

both whole and reduced-fat milk and 14–18 year olds getting more from fried potatoes.

Major contributors also included fried potatoes among non-Hispanic Blacks and persons

with PIR between 131% and 185%, Mexican dishes among Mexican-Americans, reduced-

fat milk among non-Hispanic Whites and persons with PIR greater than 185%, and pasta

among persons with PIR greater than 185% (Table 2).

Added Sugars

The average daily intake of energy from added sugars among all 2–18 year olds was 365

kcal (Table 1). The major sources of added sugars were soda (116 kcal/day from added

sugars), fruit drinks (55 kcal), grain desserts (40 kcal), dairy desserts (29 kcal), and candy

(25 kcal). The list does not vary markedly by age and demographic groups, but cold cereals

were among the top sources for 2–8 year old children, Non-Hispanic Whites, and low-

income groups (Table 2).

Sugar-sweetened beverages (soda and fruit drinks) represented the top two sources of

calories from added sugars among nearly all age and demographic groups (Tables 1 and 2).

The consumption of added sugar from sugar-sweetened beverages was 60 kcal/day for 2–3

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 4

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

paper, mean intakes of energy, solid fats, and added sugars, and results from the top five

sources are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 2.

Energy

The top five sources of energy for 2–18 years olds were grain desserts (cakes, cookies,

donuts, pies, crisps, cobblers, and granola bars) (138 kcal/day), pizza (136 kcal), soda (118

kcal), yeast breads (114 kcal), and chicken and chicken mixed dishes (113 kcal) (Table 1).

These foods each contributed more than 5% to energy intake, or more than 100 kcal per

child per day. Combining related specific foods within the beverage category, children and

adolescents consumed 173 kcal from sugar-sweetened beverages (combining soda and fruit

drinks) and 146 kcal from milk (combining whole and reduced-fat versions) (data for fruit

drinks and reduced fat milk do not always appear in the top five sources, so these data are

available online).

These major contributors varied by age group. For example, the top five sources of energy

for 2–3 years olds included whole milk (104 kcal/day), fruit juice (93 kcal), reduced-fat milk

(91 kcal), and pasta and pasta dishes (86 kcal). Pasta and reduced-fat milk were also among

the top five sources of energy for 4–8 years olds (97 and 95 kcal, respectively).

The top contributors of energy also varied by race/ethnicity (Table 2). For example, major

contributors for 2–18 year old Non-Hispanic Blacks included fruit drinks (100 kcal/day) and

pasta and pasta dishes (90 kcal), while Mexican-Americans’ top sources included Mexican

mixed dishes (136 kcal) and whole milk (99 kcal). Non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites

consumed more energy from sugar-sweetened beverages (combining soda and fruit drinks)

than from milk (combining all milks), whereas Mexican-Americans consumed more energy

from milk than from sugar-sweetened beverages (Table 2 and online tables). The top five

sources of energy by income were consistent across income levels, but varied in ranking

order.

Solid Fats

The average daily intake of energy from solid fats among 2–18 year olds is 433 kcal (Table

1). The major sources of solid fat were pizza (50 kcal/day from solid fat), grain desserts (43

kcal), whole milk (35 kcal), regular cheese (34 kcal), and fatty meats (29 kcal). This list

varied by age group, with younger children obtaining a greater share of their solid fat from

both whole and reduced-fat milk and 14–18 year olds getting more from fried potatoes.

Major contributors also included fried potatoes among non-Hispanic Blacks and persons

with PIR between 131% and 185%, Mexican dishes among Mexican-Americans, reduced-

fat milk among non-Hispanic Whites and persons with PIR greater than 185%, and pasta

among persons with PIR greater than 185% (Table 2).

Added Sugars

The average daily intake of energy from added sugars among all 2–18 year olds was 365

kcal (Table 1). The major sources of added sugars were soda (116 kcal/day from added

sugars), fruit drinks (55 kcal), grain desserts (40 kcal), dairy desserts (29 kcal), and candy

(25 kcal). The list does not vary markedly by age and demographic groups, but cold cereals

were among the top sources for 2–8 year old children, Non-Hispanic Whites, and low-

income groups (Table 2).

Sugar-sweetened beverages (soda and fruit drinks) represented the top two sources of

calories from added sugars among nearly all age and demographic groups (Tables 1 and 2).

The consumption of added sugar from sugar-sweetened beverages was 60 kcal/day for 2–3

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 4

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

year olds, 121 kcal for 4–8 year olds, 169 kcal for 9–13 year olds, and 260 kcal for 14–18

year olds. Among all racial/ethnic and income groups, sugar-sweetened beverages

contributed about 45–50% of added sugars. Non-Hispanic Blacks obtained more added

sugars from fruit drinks and less from soda than other groups.

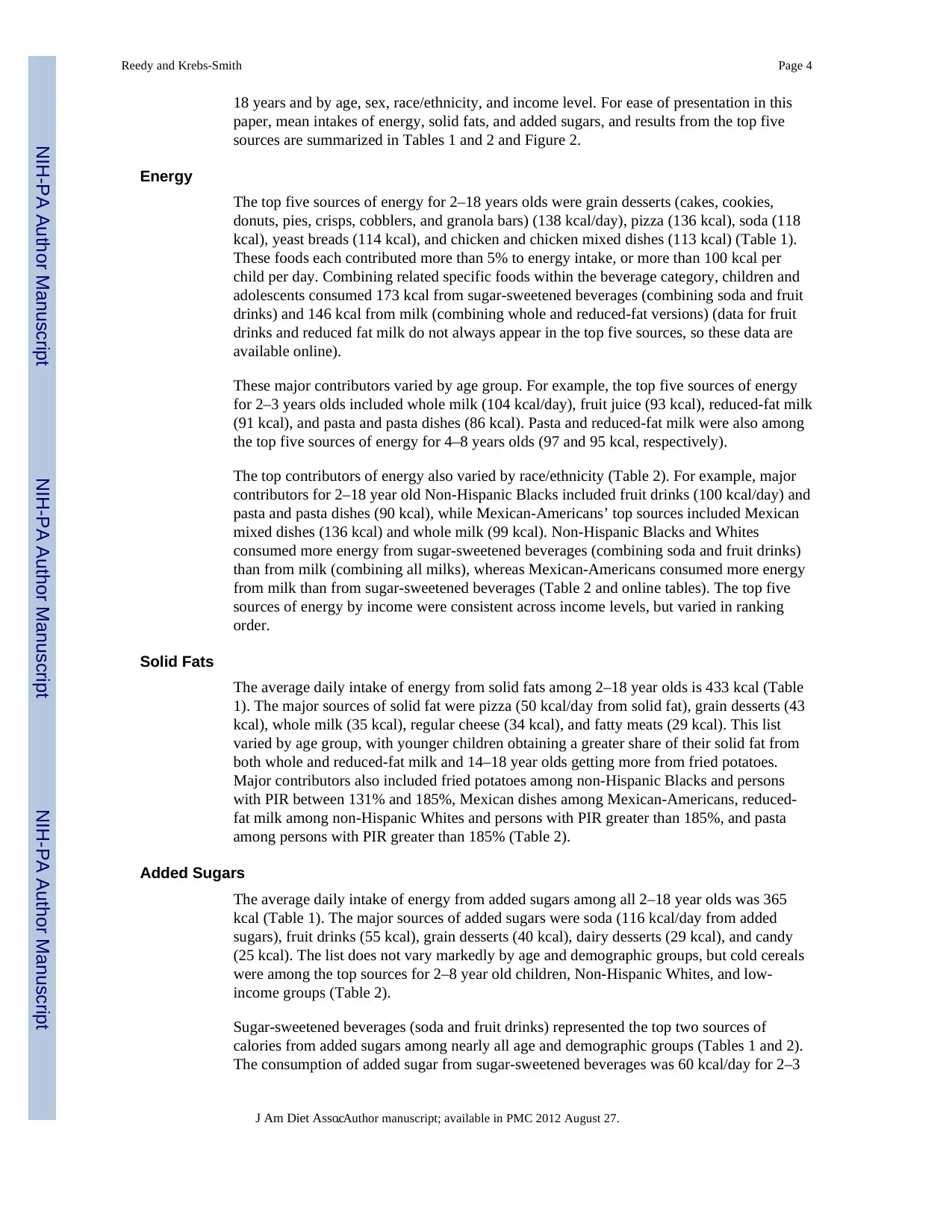

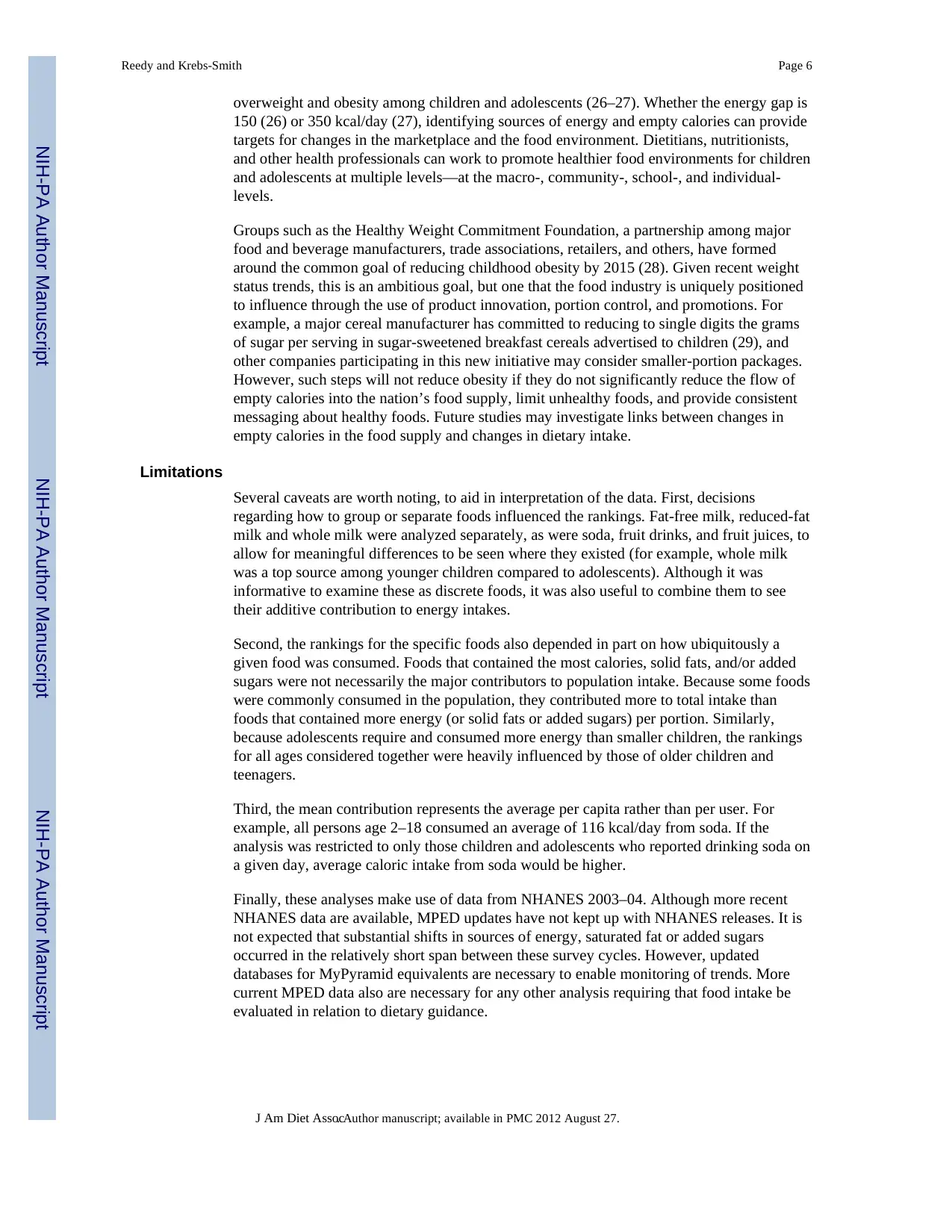

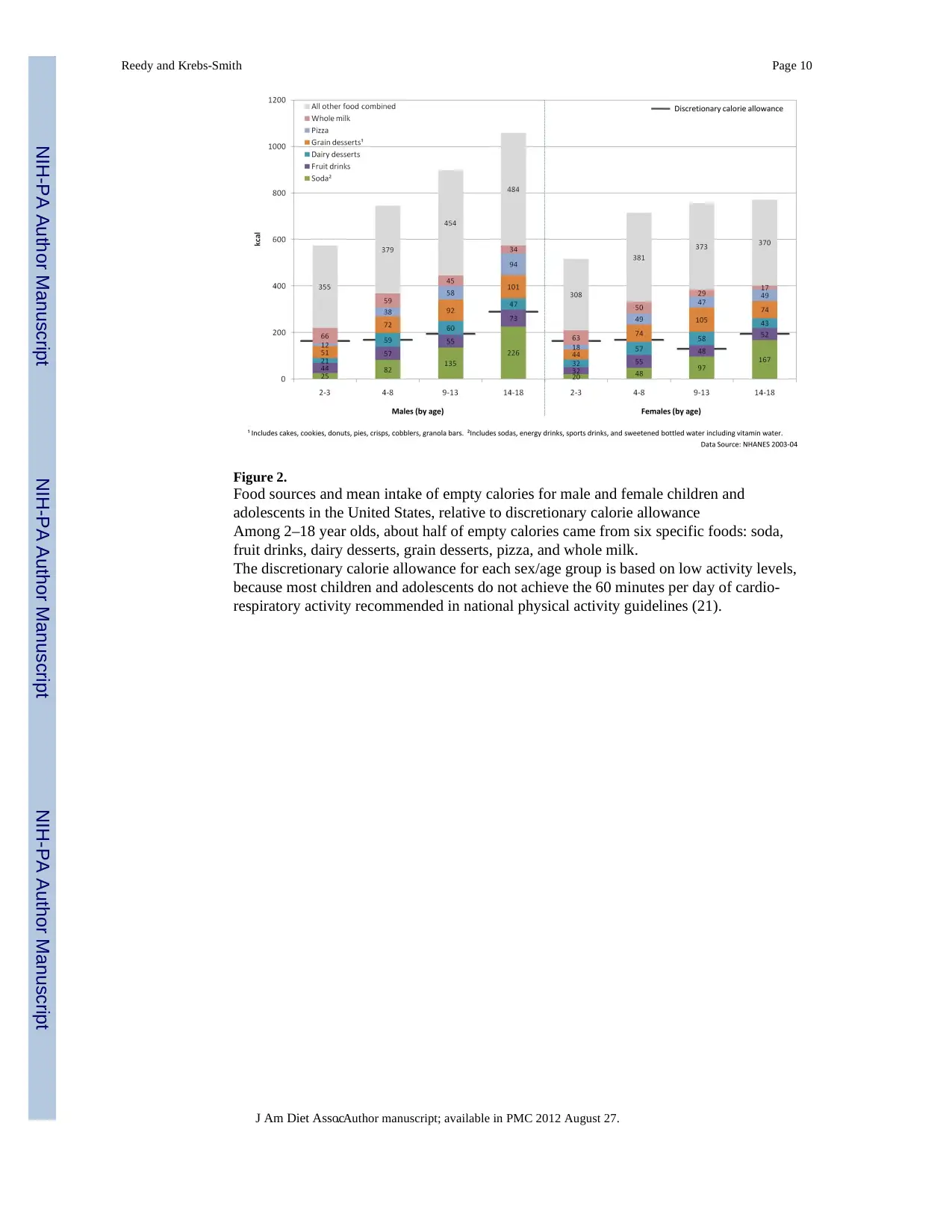

Empty Calories

Empty calories represented the sum of calories from solid fat and added sugars. Nearly 40%

of total calories consumed (798 kcal/day of 2027 kcal) by 2–18 year olds were in the form of

empty calories (433 kcal from solid fat and 365 kcal from added sugars, as shown in Table

1). This contrasts markedly with the discretionary calorie allowances, which range from 8%

to 20% of total calories. As shown in Figure 2, consumption of empty calories far exceeded

the corresponding discretionary calorie allowance for all sex-age groups.

Among 2–18 year olds, about half of these empty calories came from six specific foods:

soda, fruit drinks, dairy desserts, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk (Figure 2). Solid fats

and added sugars found in all other foods combined supplied the remainder. Sugar-

sweetened beverages were the largest contributor, providing 22% of empty calories (data

available online). In fact, among both males and females 9–13 and 14–18 years old, the

empty calories consumed from soda and fruit drinks alone effectively “used up” or exceeded

the discretionary calorie allowance.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first paper to provide data on sources of solid fats and added

sugars (collectively, empty calories) as well as total energy, among diets of children and

adolescents, examined by race/ethnicity, income, and age groups. The variables examined

are based on the most recent available data on a nationally representative sample of US

children and adolescents.

Several previously published analyses laid the foundation for this work (15–18,21–25).

Subar et al. examined data from the 1989–1991 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by

Individuals (15) and found 2–18 year olds in the US consumed 11.7% of energy from milk

and 4.3% of total energy from soda (and 6.5% from all sugar-sweetened beverages). A

higher proportion of energy consumption from soda and all sugar-sweetened beverages

(5.8% and 8.5%, respectively) and a lower proportion of milk (7.1%) were identified in the

current study. These trends regarding an increase in total energy from soda and fruit drinks

are consistent with previous research (24–25). More recently, Wang et al. found that 2–19

years olds consumed 10–15% of energy intake from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100%

fruit juice (25). Although the food groupings and age groupings were slightly different, our

results are consistent with their findings (2–18 year olds consumed 11.1% of energy intake

from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juice) (25).

A notable overlap was found between the major sources of energy and major sources of

empty calories: soda, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk. Soda is made up solely of empty

calories; grain desserts can provide some nutrients but are generally rich in both solid fats

and added sugars; and pizza and whole milk supply needed nutrients but are also rich in

solid fats. Whole milk has more nutrient-dense alternatives: fat-free milk and/or reduced-fat

milk. Pizza and grain desserts are generally made commercially; these foods could benefit

from reformulation to reduce the empty calories and make them healthier.

The landscape of choices available to children and adolescents must change to provide fewer

unhealthy foods and more healthy foods with fewer calories. Several analyses have

attempted to quantify the existing “energy gap,” or energy imbalance that contributes to

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 5

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

year olds. Among all racial/ethnic and income groups, sugar-sweetened beverages

contributed about 45–50% of added sugars. Non-Hispanic Blacks obtained more added

sugars from fruit drinks and less from soda than other groups.

Empty Calories

Empty calories represented the sum of calories from solid fat and added sugars. Nearly 40%

of total calories consumed (798 kcal/day of 2027 kcal) by 2–18 year olds were in the form of

empty calories (433 kcal from solid fat and 365 kcal from added sugars, as shown in Table

1). This contrasts markedly with the discretionary calorie allowances, which range from 8%

to 20% of total calories. As shown in Figure 2, consumption of empty calories far exceeded

the corresponding discretionary calorie allowance for all sex-age groups.

Among 2–18 year olds, about half of these empty calories came from six specific foods:

soda, fruit drinks, dairy desserts, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk (Figure 2). Solid fats

and added sugars found in all other foods combined supplied the remainder. Sugar-

sweetened beverages were the largest contributor, providing 22% of empty calories (data

available online). In fact, among both males and females 9–13 and 14–18 years old, the

empty calories consumed from soda and fruit drinks alone effectively “used up” or exceeded

the discretionary calorie allowance.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first paper to provide data on sources of solid fats and added

sugars (collectively, empty calories) as well as total energy, among diets of children and

adolescents, examined by race/ethnicity, income, and age groups. The variables examined

are based on the most recent available data on a nationally representative sample of US

children and adolescents.

Several previously published analyses laid the foundation for this work (15–18,21–25).

Subar et al. examined data from the 1989–1991 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by

Individuals (15) and found 2–18 year olds in the US consumed 11.7% of energy from milk

and 4.3% of total energy from soda (and 6.5% from all sugar-sweetened beverages). A

higher proportion of energy consumption from soda and all sugar-sweetened beverages

(5.8% and 8.5%, respectively) and a lower proportion of milk (7.1%) were identified in the

current study. These trends regarding an increase in total energy from soda and fruit drinks

are consistent with previous research (24–25). More recently, Wang et al. found that 2–19

years olds consumed 10–15% of energy intake from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100%

fruit juice (25). Although the food groupings and age groupings were slightly different, our

results are consistent with their findings (2–18 year olds consumed 11.1% of energy intake

from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juice) (25).

A notable overlap was found between the major sources of energy and major sources of

empty calories: soda, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk. Soda is made up solely of empty

calories; grain desserts can provide some nutrients but are generally rich in both solid fats

and added sugars; and pizza and whole milk supply needed nutrients but are also rich in

solid fats. Whole milk has more nutrient-dense alternatives: fat-free milk and/or reduced-fat

milk. Pizza and grain desserts are generally made commercially; these foods could benefit

from reformulation to reduce the empty calories and make them healthier.

The landscape of choices available to children and adolescents must change to provide fewer

unhealthy foods and more healthy foods with fewer calories. Several analyses have

attempted to quantify the existing “energy gap,” or energy imbalance that contributes to

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 5

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

overweight and obesity among children and adolescents (26–27). Whether the energy gap is

150 (26) or 350 kcal/day (27), identifying sources of energy and empty calories can provide

targets for changes in the marketplace and the food environment. Dietitians, nutritionists,

and other health professionals can work to promote healthier food environments for children

and adolescents at multiple levels—at the macro-, community-, school-, and individual-

levels.

Groups such as the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, a partnership among major

food and beverage manufacturers, trade associations, retailers, and others, have formed

around the common goal of reducing childhood obesity by 2015 (28). Given recent weight

status trends, this is an ambitious goal, but one that the food industry is uniquely positioned

to influence through the use of product innovation, portion control, and promotions. For

example, a major cereal manufacturer has committed to reducing to single digits the grams

of sugar per serving in sugar-sweetened breakfast cereals advertised to children (29), and

other companies participating in this new initiative may consider smaller-portion packages.

However, such steps will not reduce obesity if they do not significantly reduce the flow of

empty calories into the nation’s food supply, limit unhealthy foods, and provide consistent

messaging about healthy foods. Future studies may investigate links between changes in

empty calories in the food supply and changes in dietary intake.

Limitations

Several caveats are worth noting, to aid in interpretation of the data. First, decisions

regarding how to group or separate foods influenced the rankings. Fat-free milk, reduced-fat

milk and whole milk were analyzed separately, as were soda, fruit drinks, and fruit juices, to

allow for meaningful differences to be seen where they existed (for example, whole milk

was a top source among younger children compared to adolescents). Although it was

informative to examine these as discrete foods, it was also useful to combine them to see

their additive contribution to energy intakes.

Second, the rankings for the specific foods also depended in part on how ubiquitously a

given food was consumed. Foods that contained the most calories, solid fats, and/or added

sugars were not necessarily the major contributors to population intake. Because some foods

were commonly consumed in the population, they contributed more to total intake than

foods that contained more energy (or solid fats or added sugars) per portion. Similarly,

because adolescents require and consumed more energy than smaller children, the rankings

for all ages considered together were heavily influenced by those of older children and

teenagers.

Third, the mean contribution represents the average per capita rather than per user. For

example, all persons age 2–18 consumed an average of 116 kcal/day from soda. If the

analysis was restricted to only those children and adolescents who reported drinking soda on

a given day, average caloric intake from soda would be higher.

Finally, these analyses make use of data from NHANES 2003–04. Although more recent

NHANES data are available, MPED updates have not kept up with NHANES releases. It is

not expected that substantial shifts in sources of energy, saturated fat or added sugars

occurred in the relatively short span between these survey cycles. However, updated

databases for MyPyramid equivalents are necessary to enable monitoring of trends. More

current MPED data also are necessary for any other analysis requiring that food intake be

evaluated in relation to dietary guidance.

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 6

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

150 (26) or 350 kcal/day (27), identifying sources of energy and empty calories can provide

targets for changes in the marketplace and the food environment. Dietitians, nutritionists,

and other health professionals can work to promote healthier food environments for children

and adolescents at multiple levels—at the macro-, community-, school-, and individual-

levels.

Groups such as the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, a partnership among major

food and beverage manufacturers, trade associations, retailers, and others, have formed

around the common goal of reducing childhood obesity by 2015 (28). Given recent weight

status trends, this is an ambitious goal, but one that the food industry is uniquely positioned

to influence through the use of product innovation, portion control, and promotions. For

example, a major cereal manufacturer has committed to reducing to single digits the grams

of sugar per serving in sugar-sweetened breakfast cereals advertised to children (29), and

other companies participating in this new initiative may consider smaller-portion packages.

However, such steps will not reduce obesity if they do not significantly reduce the flow of

empty calories into the nation’s food supply, limit unhealthy foods, and provide consistent

messaging about healthy foods. Future studies may investigate links between changes in

empty calories in the food supply and changes in dietary intake.

Limitations

Several caveats are worth noting, to aid in interpretation of the data. First, decisions

regarding how to group or separate foods influenced the rankings. Fat-free milk, reduced-fat

milk and whole milk were analyzed separately, as were soda, fruit drinks, and fruit juices, to

allow for meaningful differences to be seen where they existed (for example, whole milk

was a top source among younger children compared to adolescents). Although it was

informative to examine these as discrete foods, it was also useful to combine them to see

their additive contribution to energy intakes.

Second, the rankings for the specific foods also depended in part on how ubiquitously a

given food was consumed. Foods that contained the most calories, solid fats, and/or added

sugars were not necessarily the major contributors to population intake. Because some foods

were commonly consumed in the population, they contributed more to total intake than

foods that contained more energy (or solid fats or added sugars) per portion. Similarly,

because adolescents require and consumed more energy than smaller children, the rankings

for all ages considered together were heavily influenced by those of older children and

teenagers.

Third, the mean contribution represents the average per capita rather than per user. For

example, all persons age 2–18 consumed an average of 116 kcal/day from soda. If the

analysis was restricted to only those children and adolescents who reported drinking soda on

a given day, average caloric intake from soda would be higher.

Finally, these analyses make use of data from NHANES 2003–04. Although more recent

NHANES data are available, MPED updates have not kept up with NHANES releases. It is

not expected that substantial shifts in sources of energy, saturated fat or added sugars

occurred in the relatively short span between these survey cycles. However, updated

databases for MyPyramid equivalents are necessary to enable monitoring of trends. More

current MPED data also are necessary for any other analysis requiring that food intake be

evaluated in relation to dietary guidance.

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 6

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Conclusion

The epidemic of obesity among children and adolescents is now widely regarded as one of

the most important public health problems in the US. Most experts agree that the solution

will involve changes in both diet and physical activity, in order to affect energy balance. For

diet, this means a reduction in energy from current consumption levels. Although reduction

in energy intake from any source could lead to weight change, it would seem imprudent to

advise children to cut down on key nutrient-bearing food groups, such as fruits, vegetables,

whole grains, fat-free milk, and lean meats. This is especially true given that solid fats and

added sugars are consumed in amounts far in excess of allowance levels. This paper

identifies the major sources of overall energy and empty calories, providing context for

dietary guidance that could specifically focus on limiting calories from these sources and for

changes in the food environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Lisa Kahle, Information Management Systems, Inc, for

SAS programming and data analysis, Carmita Signes, NOVA Research, for table and figure preparation, and Anne

Rodgers for thoughtful review.

References

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and

adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA. 2008; 299:2401–2405. [PubMed: 18505949]

2. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in

US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010 Jan 13. [Epub ahead of print].

3. Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease.

Pediatrics. 1998; 101:518–25. [PubMed: 12224658]

4. Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children

and adolescents. JAMA. 2003; 289:1813–9. [PubMed: 12684360]

5. Nielsen SJ, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake in US between 1977 and 1996:

Similar shifts seen across age groups. Obesity Research. 2002; 10:370–378. [PubMed: 12006636]

6. Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Patterns and trends in food portion sizes, 1977–1998. JAMA. 2003;

289:450–3. [PubMed: 12533124]

7. Brownell KD, Schwartz MB, Puhl RM, Henderson KE, Harris JL. The need for bold action to

prevent adolescent obesity. J Adolesc Health. 2009; 45:S8–17. Epub 2009 Jun 11. [PubMed:

19699441]

8. Krebs-Smith SM, Reedy J, Bosire C. Healthfulness of the U.S. food supply: little improvement

despite decades of dietary guidance. Am J Prev Med. 2010; 38:472–7. [PubMed: 20153133]

9. National Cancer Institute. Usual Dietary Intakes: Food Intakes, US Population, 2001–04. [Accessed

on December 17, 2009]. http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/diet/usualintakes/pop/

10. US Department of Agriculture. MyPyramid. [Accessed on December 17, 2009].

http://www.mypyramid.gov

11. US Department of Health and Human Service and US Department of Agriculture. Dietary

Guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6. Washington D.C: US Government Printing Office; January.

2005

12. Guenther PM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Development of the Healthy Eating Index-2005. J Am

Diet Assoc. 2008; 108:1896–1901. [PubMed: 18954580]

13. Basiotis, PP.; Guenther, PM.; Lino, M.; Britten, P. Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion.

Nutrition Insight 33, June 2006. Americans consume too many calories from solid fat, alcohol, and

added sugar. [Accessed December 17, 2009].

http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/NutritionInsights/Insight33.pdf

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 7

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

The epidemic of obesity among children and adolescents is now widely regarded as one of

the most important public health problems in the US. Most experts agree that the solution

will involve changes in both diet and physical activity, in order to affect energy balance. For

diet, this means a reduction in energy from current consumption levels. Although reduction

in energy intake from any source could lead to weight change, it would seem imprudent to

advise children to cut down on key nutrient-bearing food groups, such as fruits, vegetables,

whole grains, fat-free milk, and lean meats. This is especially true given that solid fats and

added sugars are consumed in amounts far in excess of allowance levels. This paper

identifies the major sources of overall energy and empty calories, providing context for

dietary guidance that could specifically focus on limiting calories from these sources and for

changes in the food environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Lisa Kahle, Information Management Systems, Inc, for

SAS programming and data analysis, Carmita Signes, NOVA Research, for table and figure preparation, and Anne

Rodgers for thoughtful review.

References

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and

adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA. 2008; 299:2401–2405. [PubMed: 18505949]

2. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in

US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010 Jan 13. [Epub ahead of print].

3. Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease.

Pediatrics. 1998; 101:518–25. [PubMed: 12224658]

4. Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children

and adolescents. JAMA. 2003; 289:1813–9. [PubMed: 12684360]

5. Nielsen SJ, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake in US between 1977 and 1996:

Similar shifts seen across age groups. Obesity Research. 2002; 10:370–378. [PubMed: 12006636]

6. Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Patterns and trends in food portion sizes, 1977–1998. JAMA. 2003;

289:450–3. [PubMed: 12533124]

7. Brownell KD, Schwartz MB, Puhl RM, Henderson KE, Harris JL. The need for bold action to

prevent adolescent obesity. J Adolesc Health. 2009; 45:S8–17. Epub 2009 Jun 11. [PubMed:

19699441]

8. Krebs-Smith SM, Reedy J, Bosire C. Healthfulness of the U.S. food supply: little improvement

despite decades of dietary guidance. Am J Prev Med. 2010; 38:472–7. [PubMed: 20153133]

9. National Cancer Institute. Usual Dietary Intakes: Food Intakes, US Population, 2001–04. [Accessed

on December 17, 2009]. http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/diet/usualintakes/pop/

10. US Department of Agriculture. MyPyramid. [Accessed on December 17, 2009].

http://www.mypyramid.gov

11. US Department of Health and Human Service and US Department of Agriculture. Dietary

Guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6. Washington D.C: US Government Printing Office; January.

2005

12. Guenther PM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Development of the Healthy Eating Index-2005. J Am

Diet Assoc. 2008; 108:1896–1901. [PubMed: 18954580]

13. Basiotis, PP.; Guenther, PM.; Lino, M.; Britten, P. Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion.

Nutrition Insight 33, June 2006. Americans consume too many calories from solid fat, alcohol, and

added sugar. [Accessed December 17, 2009].

http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/NutritionInsights/Insight33.pdf

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 7

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

14. National Center for Health Statistics. Dietary Interview, NHANES 2003–2006. Public Data

General Release File Documentation. [Accessed December 17, 2009].

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm

15. Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Kahle LL. Dietary sources of nutrients among US children,

1989–1991. Pediatrics. 1998; 102:913–923. [PubMed: 9755265]

16. Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Kahle LL. Dietary sources of nutrients among US adults,

1989 to 1991. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998; 98:537–547. [PubMed: 9597026]

17. Cotton PA, Subar AF, Friday JE, Cook A. Dietary sources of nutrients among US adults, 1994 to

1996. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004; 104:921–930. [PubMed: 15175590]

18. Bachman JL, Reedy J, Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM. Sources of food group intakes among the US

population, 2001–2002. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008; 108:804–814. [PubMed: 18442504]

19. MyPyramid Equivalents Database, version 2.0. [Accessed December 17, 2009].

http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=8498

20. Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the

United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008; 40:181–8. [PubMed:

18091006]

21. Thompson FE, Dennison BA. Dietary sources of fats and cholesterol in US children aged 2

through 5 years. Am J Public Health. 1994; 84:799–806. [PubMed: 8179052]

22. Troiano RP, Briefel RR, Carroll MD, Bialostosky K. Energy and fat intakes of children and

adolescents in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination

Surveys. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000; 72:1343S–1353S. [PubMed: 11063476]

23. Guthrie JF, Morton JF. Food sources of added sweeteners in the diets of Americans. J Am Diet

Assoc. 2000; 100:43–51. [PubMed: 10646004]

24. Nielsen S, Popkin B. Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001. Am J Prev Med. 2004;

27:205–210. [PubMed: 15450632]

25. Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened

beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988–2004. Pediatrics. 2008;

121:e1604–e1614. [PubMed: 18519465]

26. Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Sobol AM, Kuntz KM. Estimating the energy gap among US children:

A Counterfactual Approach. Pediatrics. 2006; 118:e1721–e1733. [PubMed: 17142497]

27. Swinburn B, Sacks G, Ravussin E. Increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain

the US epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009; 90:1453–6. [PubMed: 19828708]

28. Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation. [Accessed December 17, 2009].

http://www.healthyweightcommit.org/about

29. General Mills Announces Plans to Reduce Sugar Content of Children's Cereals. [Accessed

December 17, 2009]. http://www.rwjf.org/childhoodobesity/digest.jsp?id=26422

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 8

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

General Release File Documentation. [Accessed December 17, 2009].

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm

15. Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Kahle LL. Dietary sources of nutrients among US children,

1989–1991. Pediatrics. 1998; 102:913–923. [PubMed: 9755265]

16. Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Kahle LL. Dietary sources of nutrients among US adults,

1989 to 1991. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998; 98:537–547. [PubMed: 9597026]

17. Cotton PA, Subar AF, Friday JE, Cook A. Dietary sources of nutrients among US adults, 1994 to

1996. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004; 104:921–930. [PubMed: 15175590]

18. Bachman JL, Reedy J, Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM. Sources of food group intakes among the US

population, 2001–2002. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008; 108:804–814. [PubMed: 18442504]

19. MyPyramid Equivalents Database, version 2.0. [Accessed December 17, 2009].

http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=8498

20. Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the

United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008; 40:181–8. [PubMed:

18091006]

21. Thompson FE, Dennison BA. Dietary sources of fats and cholesterol in US children aged 2

through 5 years. Am J Public Health. 1994; 84:799–806. [PubMed: 8179052]

22. Troiano RP, Briefel RR, Carroll MD, Bialostosky K. Energy and fat intakes of children and

adolescents in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination

Surveys. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000; 72:1343S–1353S. [PubMed: 11063476]

23. Guthrie JF, Morton JF. Food sources of added sweeteners in the diets of Americans. J Am Diet

Assoc. 2000; 100:43–51. [PubMed: 10646004]

24. Nielsen S, Popkin B. Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001. Am J Prev Med. 2004;

27:205–210. [PubMed: 15450632]

25. Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened

beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988–2004. Pediatrics. 2008;

121:e1604–e1614. [PubMed: 18519465]

26. Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Sobol AM, Kuntz KM. Estimating the energy gap among US children:

A Counterfactual Approach. Pediatrics. 2006; 118:e1721–e1733. [PubMed: 17142497]

27. Swinburn B, Sacks G, Ravussin E. Increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain

the US epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009; 90:1453–6. [PubMed: 19828708]

28. Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation. [Accessed December 17, 2009].

http://www.healthyweightcommit.org/about

29. General Mills Announces Plans to Reduce Sugar Content of Children's Cereals. [Accessed

December 17, 2009]. http://www.rwjf.org/childhoodobesity/digest.jsp?id=26422

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 8

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Figure 1.

List of specific foods: Result of grouping like foods reported in 2003–2004 and 2005–2006

NHANESa

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 9

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

List of specific foods: Result of grouping like foods reported in 2003–2004 and 2005–2006

NHANESa

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 9

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Figure 2.

Food sources and mean intake of empty calories for male and female children and

adolescents in the United States, relative to discretionary calorie allowance

Among 2–18 year olds, about half of empty calories came from six specific foods: soda,

fruit drinks, dairy desserts, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk.

The discretionary calorie allowance for each sex/age group is based on low activity levels,

because most children and adolescents do not achieve the 60 minutes per day of cardio-

respiratory activity recommended in national physical activity guidelines (21).

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 10

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Food sources and mean intake of empty calories for male and female children and

adolescents in the United States, relative to discretionary calorie allowance

Among 2–18 year olds, about half of empty calories came from six specific foods: soda,

fruit drinks, dairy desserts, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk.

The discretionary calorie allowance for each sex/age group is based on low activity levels,

because most children and adolescents do not achieve the 60 minutes per day of cardio-

respiratory activity recommended in national physical activity guidelines (21).

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 10

J Am Diet Assoc. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 August 27.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 11

Table 1

urces of energy, solid fats and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States (2–18 years old)

Top five sources

Mean

(kcal) SE #2 %

Mean

(kcal) SE #3 %

Mean

(kcal) SE #4 %

Mean

(kcal) SE #5 %

Mean

(kcal) SE

.8 138 6.7 Pizza 6.7 136 8.5 Soda c 5.8 118 8.7 Yeast breads 5.6 114 6.8 Chicken d 5.6 113 8.1

.1 104 8.2 100% fruit juice e 6.3 93 9.4 Reduced fat milk 6.2 91 10.7 Pasta f 5.9 86 9.4 Grain desserts b 4.6 68 6.6

.6 136 10.8 Yeast breads 5.4 98 5.1 Pasta f 5.4 97 11.4 Reduced fat milk 5.3 95 7.2 Pizza 5.3 95 12.3

.1 145 15.6 Pizza 6.3 128 9.5 Chicken d 6.0 122 13.1 Yeast breads 5.4 109 5.8 Soda c 5.2 105 12.1

.3 226 18.2 Pizza 8.8 213 24.5 Grain desserts b 6.5 157 8.4 Yeast breads 6.2 151 14.5 Chicken d 5.9 143 16.6

1.5 50 3.6 Grain desserts b 9.8 43 2.4 Whole milk 8.2 35 3.2 Regular cheese 7.9 34 2.9 Fatty meats h 6.7 29 2.5

6.7 58 5.6 Fatty meats h 11.1 39 5.0 Regular cheese 8.6 30 6.0 Reduced fat milk 8.1 28 3.8 Grain desserts b 7.2 25 2.4

1.3 45 5.6 Pizza 10.2 41 6.0 Grain desserts b 9.0 36 2.6 Regular cheese 7.0 28 4.5 Reduced fat milk 6.9 28 3.6

1.4 51 6.0 Pizza 11.2 50 5.2 Regular cheese 8.9 40 5.3 Whole milk 6.7 30 4.4 Fatty meats h 6.5 29 2.9

4.7 70 9.3 Grain desserts b 9.7 46 2.8 Regular cheese 7.6 36 3.2 Fried potatoes 6.9 33 2.3 Fatty meats h 5.7 27 3.0

1.8 116 5.3 Fruit drinks 15.0 55 3.1 Grain desserts b 10.9 40 2.3 Dairy desserts 7.9 29 3.4 Candy 6.8 25 2.2

9.3 38 3.7 Soda c 11.4 22 3.3 Grain desserts b 11.3 22 1.7 Candy 8.5 17 2.5 Cold cereals 8.3 16 1.6

9.9 65 7.5 Fruit drinks 17.0 56 5.9 Grain desserts b 11.2 37 2.8 Dairy desserts 10.4 34 5.9 Cold cereals 8.3 27 1.9

0.7 117 11.7 Fruit drinks 13.6 52 5.7 Grain desserts b 12.4 47 5.6 Dairy desserts 8.8 33 5.2 Candy 7.8 30 3.1

4.5 197 9.7 Fruit drinks 14.1 63 5.6 Grain desserts b 9.4 42 2.9 Candy 5.6 25 4.1 Dairy desserts 5.5 24 2.7

ANES 2005–2006, Solid Fats and Added Sugars data from NHANES 2003–2004.

by group by group: Ages 2–18 (n=3778), 2–3 (n=497), 4–8 (n=899), 9–13 (n=1047), 14–18 (n=1335).

by group by group: Ages 2–18 (n=3553), 2–3 (n=424), 4–8 (n=781), 9–13 (n=1001), 14–18 (n=1347).

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 11

Table 1

urces of energy, solid fats and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States (2–18 years old)

Top five sources

Mean

(kcal) SE #2 %

Mean

(kcal) SE #3 %

Mean

(kcal) SE #4 %

Mean

(kcal) SE #5 %

Mean

(kcal) SE

.8 138 6.7 Pizza 6.7 136 8.5 Soda c 5.8 118 8.7 Yeast breads 5.6 114 6.8 Chicken d 5.6 113 8.1

.1 104 8.2 100% fruit juice e 6.3 93 9.4 Reduced fat milk 6.2 91 10.7 Pasta f 5.9 86 9.4 Grain desserts b 4.6 68 6.6

.6 136 10.8 Yeast breads 5.4 98 5.1 Pasta f 5.4 97 11.4 Reduced fat milk 5.3 95 7.2 Pizza 5.3 95 12.3

.1 145 15.6 Pizza 6.3 128 9.5 Chicken d 6.0 122 13.1 Yeast breads 5.4 109 5.8 Soda c 5.2 105 12.1

.3 226 18.2 Pizza 8.8 213 24.5 Grain desserts b 6.5 157 8.4 Yeast breads 6.2 151 14.5 Chicken d 5.9 143 16.6

1.5 50 3.6 Grain desserts b 9.8 43 2.4 Whole milk 8.2 35 3.2 Regular cheese 7.9 34 2.9 Fatty meats h 6.7 29 2.5

6.7 58 5.6 Fatty meats h 11.1 39 5.0 Regular cheese 8.6 30 6.0 Reduced fat milk 8.1 28 3.8 Grain desserts b 7.2 25 2.4

1.3 45 5.6 Pizza 10.2 41 6.0 Grain desserts b 9.0 36 2.6 Regular cheese 7.0 28 4.5 Reduced fat milk 6.9 28 3.6

1.4 51 6.0 Pizza 11.2 50 5.2 Regular cheese 8.9 40 5.3 Whole milk 6.7 30 4.4 Fatty meats h 6.5 29 2.9

4.7 70 9.3 Grain desserts b 9.7 46 2.8 Regular cheese 7.6 36 3.2 Fried potatoes 6.9 33 2.3 Fatty meats h 5.7 27 3.0

1.8 116 5.3 Fruit drinks 15.0 55 3.1 Grain desserts b 10.9 40 2.3 Dairy desserts 7.9 29 3.4 Candy 6.8 25 2.2

9.3 38 3.7 Soda c 11.4 22 3.3 Grain desserts b 11.3 22 1.7 Candy 8.5 17 2.5 Cold cereals 8.3 16 1.6

9.9 65 7.5 Fruit drinks 17.0 56 5.9 Grain desserts b 11.2 37 2.8 Dairy desserts 10.4 34 5.9 Cold cereals 8.3 27 1.9

0.7 117 11.7 Fruit drinks 13.6 52 5.7 Grain desserts b 12.4 47 5.6 Dairy desserts 8.8 33 5.2 Candy 7.8 30 3.1

4.5 197 9.7 Fruit drinks 14.1 63 5.6 Grain desserts b 9.4 42 2.9 Candy 5.6 25 4.1 Dairy desserts 5.5 24 2.7

ANES 2005–2006, Solid Fats and Added Sugars data from NHANES 2003–2004.

by group by group: Ages 2–18 (n=3778), 2–3 (n=497), 4–8 (n=899), 9–13 (n=1047), 14–18 (n=1335).

by group by group: Ages 2–18 (n=3553), 2–3 (n=424), 4–8 (n=781), 9–13 (n=1001), 14–18 (n=1347).

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 12

a

Energy mean intake (kcal) by group: Ages 2–18 (2027), 2–3 (1471), 4–8 (1802), 9–13 (2035), 14–18 (2427).

b

Includes cakes, cookies, donuts, pies, crisps, cobblers, granola bars.

c

Includes sodas, energy drinks, sports drinks, and sweetened bottled water including vitamin water.

d

Includes chicken and chicken mixed dishes.

e

Excludes orange and grapefruit juice.

f

Includes pasta and pasta dishes.

g

Solid fats mean intake (kcal) by group: Ages 2–18 (433), 2–3 (350), 4–8 (401), 9–13 (450), 14–18 (476).

h

Includes sausage, franks, bacon, and ribs.

i

Added sugars mean intake (kcal) by group: Ages 2–18 (365), 2–3 (197), 4–8 (329), 9–13 (381), 14–18 (444).

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 12

a

Energy mean intake (kcal) by group: Ages 2–18 (2027), 2–3 (1471), 4–8 (1802), 9–13 (2035), 14–18 (2427).

b

Includes cakes, cookies, donuts, pies, crisps, cobblers, granola bars.

c

Includes sodas, energy drinks, sports drinks, and sweetened bottled water including vitamin water.

d

Includes chicken and chicken mixed dishes.

e

Excludes orange and grapefruit juice.

f

Includes pasta and pasta dishes.

g

Solid fats mean intake (kcal) by group: Ages 2–18 (433), 2–3 (350), 4–8 (401), 9–13 (450), 14–18 (476).

h

Includes sausage, franks, bacon, and ribs.

i

Added sugars mean intake (kcal) by group: Ages 2–18 (365), 2–3 (197), 4–8 (329), 9–13 (381), 14–18 (444).

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 13

Table 2

urces of energy, solid fats and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States (2–18 years old), by Race/Ethnicity and Family Income

Top five sources

% Mean

(kcal)

SE #2 % Mean

(kcal)

SE #3 % Mean

(kcal)

SE #4 % Mean

(kcal)

SE #5 % Mean

(kcal)

SE

7.2 152 9.3 Pizza 7.0 148 12.8 Soda d 6.4 134 13.4 Yeast breads 6.1 129 10.5 Chicken e 5.2 109 11.3

8.4 163 13.8 Grain dessertsl 6.3 123 9.3 Pizza 6.1 119 8.6 Fruit drinks 5.1 100 13.8 Pasta f 4.7 90 11.2

7.1 136 8.5 Grain dessertsl 5.9 114 10.8 Pizza 5.5 105 19.2 Whole milk 5.1 99 8.3 Sodam 4.8 92 4.6

6.1 117 9.4 Chickenn 6.0 116 13.7 Pizza 5.9 114 9.6 Sodam 5.3 101 12.8 Yeast breads 5.1 99 4.7

10.1 203 62.7 Sodam 7.0 142 48.6 Grain desserts 6.9 138 13.4 Yeast breads 6.5 131 32.7 Pastao 5.2 104 19.0

7.1 148 9.2 Pizza 6.5 135 12.4 Sodam 5.9 122 7.8 Yeast breads 5.7 119 7.7 Chickenn 5.5 114 9.0

13.0 57 5.3 Grain dessertsl 9.4 41 3.5 Regular cheese 8.9 39 4.1 Reduced fat milk 7.2 32 3.4 Whole milk 6.7 30 4.0

11.4 49 3.2 Grain dessertsl 10.4 45 4.1 Fatty meats h 10.1 44 7.5 Whole milk 8.8 38 3.0 Fried potatoes 6.2 27 1.7

12.0 52 4.5 Grain dessertsl 10.6 45 3.2 Mexican dishes 9.8 42 5.9 Pizza 8.3 36 3.9 Regular cheese 7.1 31 4.1

12.7 56 5.1 Pizza 10.0 44 6.9 Grain dessertsl 9.7 43 3.0 Fatty meatsq 8.4 37 5.2 Regular cheese 7.1 31 2.7

13.7 59 13.8 Regular cheese 10.5 46 16.7 Whole milk 9.0 39 8.8 Grain dessertsl 8.5 37 2.9 Fried potatoes 8.4 36 10.4

12.2 52 5.7 Grain dessertsl 10.2 43 3.3 Regular cheese 7.9 34 2.2 Reduced fat milk 6.3 27 3.2 Pastao 6.3 27 3.5

34.7 130 8.8 Fruit drinks 12.2 46 4.3 Grain dessertsl 10.3 39 3.2 Dairy desserts 8.4 31 4.7 Cold cereals 6.5 24 2.1

24.3 89 3.9 Sodam 21.8 80 6.5 Grain dessertsl 12.1 45 3.7 Candy 9.4 35 4.9 Dairy desserts 7.2 26 4.4

31.5 111 14.0 Fruit drinks 19.0 67 6.1 Grain dessertsl 11.5 40 3.0 Candy 6.1 21 2.0 Dairy desserts 5.8 20 2.4

30.4 110 6.0 Fruit drinks 15.0 54 4.2 Grain dessertsl 11.4 41 4.2 Cold cereals 7.7 28 2.9 Dairy desserts 7.3 27 3.4

32.7 110 8.7 Grain dessertsl 12.3 41 4.9 Fruit drinks 11.9 40 6.8 Cold cereals 8.0 27 3.8 Dairy desserts 7.2 24 3.4

32.6 122 9.2 Fruit drinks 15.5 58 4.4 Grain dessertsl 10.2 38 2.3 Dairy desserts 8.5 32 4.7 Candy 6.8 25 3.1

ANES 2005–2006, Solid Fats and Added Sugars data from NHANES 2003–2004.

by group by group: Non-Hispanic Whites (n=1018), Non-Hispanic Blacks (n=1161), Mexican-Americans (n=1253), <= 130% POV (n=1457), 131–185% POV (n=451), >=186% POV (n=1707).

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 13

Table 2

urces of energy, solid fats and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States (2–18 years old), by Race/Ethnicity and Family Income

Top five sources

% Mean

(kcal)

SE #2 % Mean

(kcal)

SE #3 % Mean

(kcal)

SE #4 % Mean

(kcal)

SE #5 % Mean

(kcal)

SE

7.2 152 9.3 Pizza 7.0 148 12.8 Soda d 6.4 134 13.4 Yeast breads 6.1 129 10.5 Chicken e 5.2 109 11.3

8.4 163 13.8 Grain dessertsl 6.3 123 9.3 Pizza 6.1 119 8.6 Fruit drinks 5.1 100 13.8 Pasta f 4.7 90 11.2

7.1 136 8.5 Grain dessertsl 5.9 114 10.8 Pizza 5.5 105 19.2 Whole milk 5.1 99 8.3 Sodam 4.8 92 4.6

6.1 117 9.4 Chickenn 6.0 116 13.7 Pizza 5.9 114 9.6 Sodam 5.3 101 12.8 Yeast breads 5.1 99 4.7

10.1 203 62.7 Sodam 7.0 142 48.6 Grain desserts 6.9 138 13.4 Yeast breads 6.5 131 32.7 Pastao 5.2 104 19.0

7.1 148 9.2 Pizza 6.5 135 12.4 Sodam 5.9 122 7.8 Yeast breads 5.7 119 7.7 Chickenn 5.5 114 9.0

13.0 57 5.3 Grain dessertsl 9.4 41 3.5 Regular cheese 8.9 39 4.1 Reduced fat milk 7.2 32 3.4 Whole milk 6.7 30 4.0

11.4 49 3.2 Grain dessertsl 10.4 45 4.1 Fatty meats h 10.1 44 7.5 Whole milk 8.8 38 3.0 Fried potatoes 6.2 27 1.7

12.0 52 4.5 Grain dessertsl 10.6 45 3.2 Mexican dishes 9.8 42 5.9 Pizza 8.3 36 3.9 Regular cheese 7.1 31 4.1

12.7 56 5.1 Pizza 10.0 44 6.9 Grain dessertsl 9.7 43 3.0 Fatty meatsq 8.4 37 5.2 Regular cheese 7.1 31 2.7

13.7 59 13.8 Regular cheese 10.5 46 16.7 Whole milk 9.0 39 8.8 Grain dessertsl 8.5 37 2.9 Fried potatoes 8.4 36 10.4

12.2 52 5.7 Grain dessertsl 10.2 43 3.3 Regular cheese 7.9 34 2.2 Reduced fat milk 6.3 27 3.2 Pastao 6.3 27 3.5

34.7 130 8.8 Fruit drinks 12.2 46 4.3 Grain dessertsl 10.3 39 3.2 Dairy desserts 8.4 31 4.7 Cold cereals 6.5 24 2.1

24.3 89 3.9 Sodam 21.8 80 6.5 Grain dessertsl 12.1 45 3.7 Candy 9.4 35 4.9 Dairy desserts 7.2 26 4.4

31.5 111 14.0 Fruit drinks 19.0 67 6.1 Grain dessertsl 11.5 40 3.0 Candy 6.1 21 2.0 Dairy desserts 5.8 20 2.4

30.4 110 6.0 Fruit drinks 15.0 54 4.2 Grain dessertsl 11.4 41 4.2 Cold cereals 7.7 28 2.9 Dairy desserts 7.3 27 3.4

32.7 110 8.7 Grain dessertsl 12.3 41 4.9 Fruit drinks 11.9 40 6.8 Cold cereals 8.0 27 3.8 Dairy desserts 7.2 24 3.4

32.6 122 9.2 Fruit drinks 15.5 58 4.4 Grain dessertsl 10.2 38 2.3 Dairy desserts 8.5 32 4.7 Candy 6.8 25 3.1

ANES 2005–2006, Solid Fats and Added Sugars data from NHANES 2003–2004.

by group by group: Non-Hispanic Whites (n=1018), Non-Hispanic Blacks (n=1161), Mexican-Americans (n=1253), <= 130% POV (n=1457), 131–185% POV (n=451), >=186% POV (n=1707).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

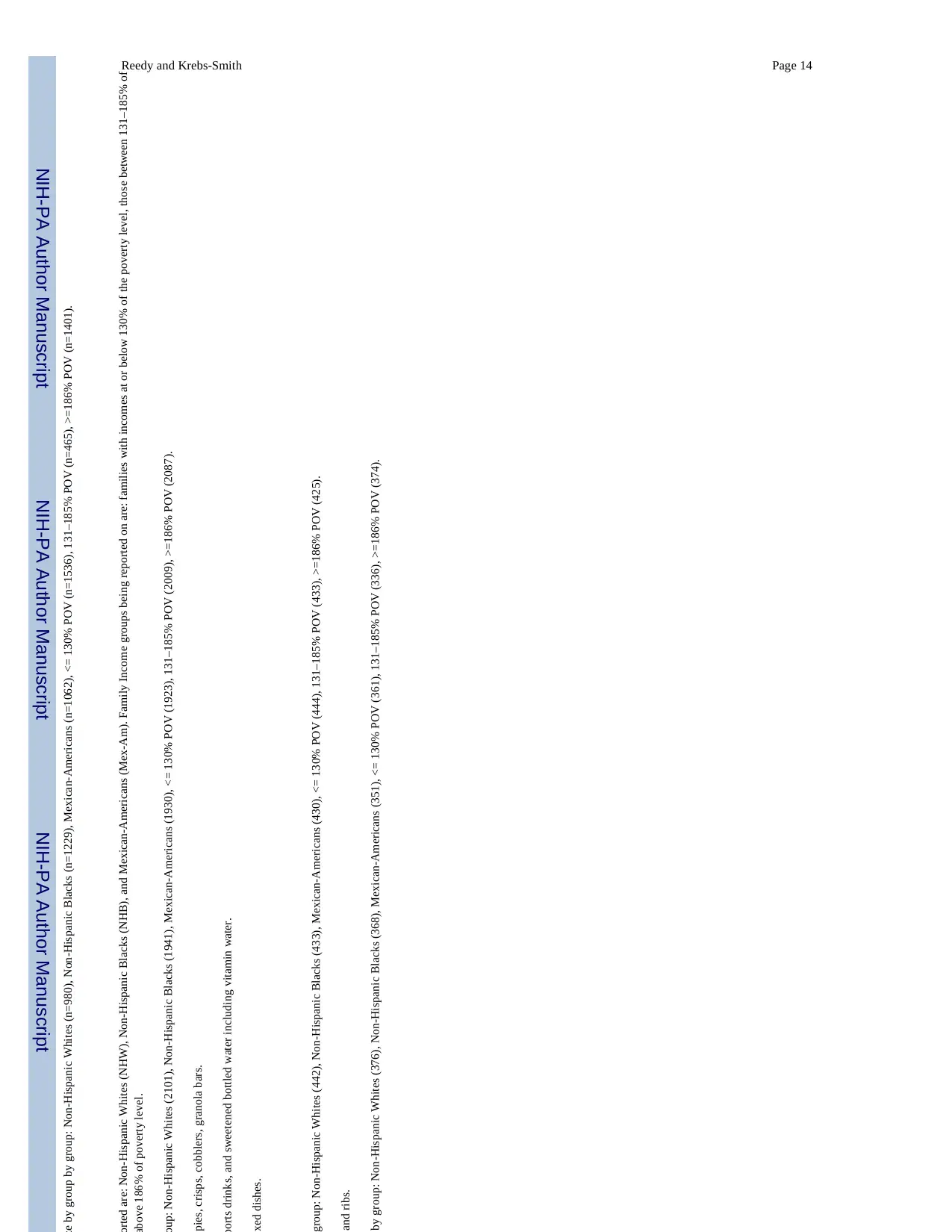

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 14

e by group by group: Non-Hispanic Whites (n=980), Non-Hispanic Blacks (n=1229), Mexican-Americans (n=1062), <= 130% POV (n=1536), 131–185% POV (n=465), >=186% POV (n=1401).

rted are: Non-Hispanic Whites (NHW), Non-Hispanic Blacks (NHB), and Mexican-Americans (Mex-Am). Family Income groups being reported on are: families with incomes at or below 130% of the poverty level, those between 131–185% of

bove 186% of poverty level.

up: Non-Hispanic Whites (2101), Non-Hispanic Blacks (1941), Mexican-Americans (1930), <= 130% POV (1923), 131–185% POV (2009), >=186% POV (2087).

pies, crisps, cobblers, granola bars.

orts drinks, and sweetened bottled water including vitamin water.

xed dishes.

roup: Non-Hispanic Whites (442), Non-Hispanic Blacks (433), Mexican-Americans (430), <= 130% POV (444), 131–185% POV (433), >=186% POV (425).

and ribs.

by group: Non-Hispanic Whites (376), Non-Hispanic Blacks (368), Mexican-Americans (351), <= 130% POV (361), 131–185% POV (336), >=186% POV (374).

Reedy and Krebs-Smith Page 14

e by group by group: Non-Hispanic Whites (n=980), Non-Hispanic Blacks (n=1229), Mexican-Americans (n=1062), <= 130% POV (n=1536), 131–185% POV (n=465), >=186% POV (n=1401).

rted are: Non-Hispanic Whites (NHW), Non-Hispanic Blacks (NHB), and Mexican-Americans (Mex-Am). Family Income groups being reported on are: families with incomes at or below 130% of the poverty level, those between 131–185% of

bove 186% of poverty level.

up: Non-Hispanic Whites (2101), Non-Hispanic Blacks (1941), Mexican-Americans (1930), <= 130% POV (1923), 131–185% POV (2009), >=186% POV (2087).

pies, crisps, cobblers, granola bars.