Analyzing Dietary Intakes of Young Children Against AGHE Guidelines

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/29

|9

|8394

|218

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes the dietary intakes of 54 Australian children aged two to three years, comparing them against the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating (AGHE) and Nutrient Reference Values (NRVs). The study found that no child met all AGHE targets, with most consuming insufficient servings of breads/cereals, vegetables, and meat/alternatives, while meeting or exceeding dairy and fruit recommendations. Macronutrient intakes were generally within recommended ranges, but saturated fatty acid consumption was excessive. Children who met selected NRVs exhibited different dietary patterns compared to AGHE recommendations, consuming more fruit, dairy, and discretionary foods, but fewer breads/cereals and vegetables. The study concludes that children's dietary intakes do not align with AGHE guidelines, although adequate nutrient profiles can be achieved through varying dietary patterns, highlighting the need for further research with larger, representative samples. Additionally, a diet analysis table is included, comparing food group servings with the AGHE, identifying key nutrients, and calculating energy provided by each food group, as well as comparing it with a person's estimated energy requirements.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Disparities exist between the Australian Guide to

Healthy Eating and the dietary intakes of young

children aged two to three years

Li K CHAI,1 Lesley MACDONALD-WICKS,2 Alexis J HURE,3 Tracy L BURROWS,2

Michelle L BLUMFIELD,1 Roger SMITH3 and Clare E COLLINS1,2

1Priority Research Centre in PhysicalActivity and Nutrition 2School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Health and

Medicine and3Hunter Medical Research Institute and Schoolof Medicine and Public Health, The University of

Newcastle, Callaghan, New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

Aim: To compare dietary intakes of young children to the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating (AGHE) and Nutrient

Reference Values (NRVs).

Methods: Dietary intakes of 54 children (50% girls) aged two to three years (mean 2.7 years) from the Women and

Their Children’s Health (WATCH) study were reported by mothers using a validated 120-item food frequency

questionnaire. Daily consumption of AGHE food group servings, macronutrients, and micronutrients were compared

to the AGHE and NRVs using t-test with significance set at P < 0.05.

Results: No child achieved all AGHE targets, with the majority consuming less breads/cereals (1.9 vs 4.0 servings/

day), vegetables (1.3 vs 2.5), and meat/alternatives (0.7 vs 1.0), all P < 0.0001. Adequate servings were observed for

dairy (2.2 vs 1.5) and fruit (1.3 vs 1.0). Macronutrients were within recommended ranges, although 96% exceeded

saturated fatty acid recommendations. Children who met selected NRVs consumed more fruit (1.4 vs 1.0; P < 0.0086),

dairy (2.2 vs 1.5; P < 0.0001) and discretionary foods (2.6 vs ≤1.0; P < 0.0001) but less breads/cereals (2.0 vs 4.0;

P < 0.0001) and vegetables (1.3 vs 2.5; P < 0.0001) servings, compared to the AGHE recommended servings.

Conclusions: Child dietary intakes did not align with AGHE, while adequate nutrient profiles were achieved by

various dietary patterns. Future studies involving data from larger, representative samples of children are warranted.

Key words: Australian Guide to Healthy Eating, children, dietary intake; Nutrient Reference Values, nutritional

status.

Introduction

Childhood nutrition can have a lifelong impact on an indi-

vidual’s health.1–3 Current research indicates that dietary pat-

terns,including frequency,variety and amountof food

habituallyconsumed,track from childhood through to

adulthood.2–4 The early years, between ages of one and three,

are a time when eating patterns, skills, knowledge and atti-

tude towards food begin to develop.5,6 Healthy childhood

eating patterns are essentialfor the provision ofsufficient

energy and nutrients for growth,cognitive development,7

and to reduce the risk ofnutrition-related chronic disease

later in life.8

In Australia,a healthy dietis characterised by the con-

sumption of a variety of foods from the five core food groups,

which are: (i) bread/cereals, mostly wholegrain and/or high

fibre varieties;(ii) fruit;(iii) vegetables and legumes/beans;

(iv) dairy products,such as reduced-fat milk yoghurt,and

cheese; and (v) lean meats/alternatives, such as poultry, fish

eggs, nuts, and legumes, with additional allowances for low

intakes of unsaturated fat and discretionary foods (energy-

dense,nutrient-poor).9 These are operationalised as a rec-

ommended number of daily servings in the Australian Guide

to Healthy Eating (AGHE).9 The 2013 AGHE was developed

from a detailed evidence base in conjunction with a Food

Modelling System10,11to establish a range of virtual diets: the

Foundation Dietsand TotalDiets.This wasachieved by

L.K. Chai BNutrDiet (Hons) APD, Research Assistant

L. MacDonald-Wicks PhD GCTT AdvAPD, Senior Lecturer Nutrition

and Dietetics

A.J. Hure PhD AdvAPD, HMRI Public Health Postdoctoral Fellow

T.L. Burrows PhD APD, Lecturer in Nutrition and Dietetics

M.L. Blumfield PhD (Nutr&Diet) APD, Postdoctoral researcher

R. Smith PhD, Professor

C.E. Collins PhD (Nutr&Diet) AdvAPD FDAA, Professor in Nutrition

and Dietetics

Correspondence: C.E. Collins, School of Health Sciences, Faculty of

Health and Medicine, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW

2308, Australia. Email: Clare.Collins@newcastle.edu.au

Accepted April 2015

bs_bs_banner

Nutrition & Dietetics 2015; ••: ••–•• DOI: 10.1111/1747-0080.12203

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia 1

Disparities exist between the Australian Guide to

Healthy Eating and the dietary intakes of young

children aged two to three years

Li K CHAI,1 Lesley MACDONALD-WICKS,2 Alexis J HURE,3 Tracy L BURROWS,2

Michelle L BLUMFIELD,1 Roger SMITH3 and Clare E COLLINS1,2

1Priority Research Centre in PhysicalActivity and Nutrition 2School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Health and

Medicine and3Hunter Medical Research Institute and Schoolof Medicine and Public Health, The University of

Newcastle, Callaghan, New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

Aim: To compare dietary intakes of young children to the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating (AGHE) and Nutrient

Reference Values (NRVs).

Methods: Dietary intakes of 54 children (50% girls) aged two to three years (mean 2.7 years) from the Women and

Their Children’s Health (WATCH) study were reported by mothers using a validated 120-item food frequency

questionnaire. Daily consumption of AGHE food group servings, macronutrients, and micronutrients were compared

to the AGHE and NRVs using t-test with significance set at P < 0.05.

Results: No child achieved all AGHE targets, with the majority consuming less breads/cereals (1.9 vs 4.0 servings/

day), vegetables (1.3 vs 2.5), and meat/alternatives (0.7 vs 1.0), all P < 0.0001. Adequate servings were observed for

dairy (2.2 vs 1.5) and fruit (1.3 vs 1.0). Macronutrients were within recommended ranges, although 96% exceeded

saturated fatty acid recommendations. Children who met selected NRVs consumed more fruit (1.4 vs 1.0; P < 0.0086),

dairy (2.2 vs 1.5; P < 0.0001) and discretionary foods (2.6 vs ≤1.0; P < 0.0001) but less breads/cereals (2.0 vs 4.0;

P < 0.0001) and vegetables (1.3 vs 2.5; P < 0.0001) servings, compared to the AGHE recommended servings.

Conclusions: Child dietary intakes did not align with AGHE, while adequate nutrient profiles were achieved by

various dietary patterns. Future studies involving data from larger, representative samples of children are warranted.

Key words: Australian Guide to Healthy Eating, children, dietary intake; Nutrient Reference Values, nutritional

status.

Introduction

Childhood nutrition can have a lifelong impact on an indi-

vidual’s health.1–3 Current research indicates that dietary pat-

terns,including frequency,variety and amountof food

habituallyconsumed,track from childhood through to

adulthood.2–4 The early years, between ages of one and three,

are a time when eating patterns, skills, knowledge and atti-

tude towards food begin to develop.5,6 Healthy childhood

eating patterns are essentialfor the provision ofsufficient

energy and nutrients for growth,cognitive development,7

and to reduce the risk ofnutrition-related chronic disease

later in life.8

In Australia,a healthy dietis characterised by the con-

sumption of a variety of foods from the five core food groups,

which are: (i) bread/cereals, mostly wholegrain and/or high

fibre varieties;(ii) fruit;(iii) vegetables and legumes/beans;

(iv) dairy products,such as reduced-fat milk yoghurt,and

cheese; and (v) lean meats/alternatives, such as poultry, fish

eggs, nuts, and legumes, with additional allowances for low

intakes of unsaturated fat and discretionary foods (energy-

dense,nutrient-poor).9 These are operationalised as a rec-

ommended number of daily servings in the Australian Guide

to Healthy Eating (AGHE).9 The 2013 AGHE was developed

from a detailed evidence base in conjunction with a Food

Modelling System10,11to establish a range of virtual diets: the

Foundation Dietsand TotalDiets.This wasachieved by

L.K. Chai BNutrDiet (Hons) APD, Research Assistant

L. MacDonald-Wicks PhD GCTT AdvAPD, Senior Lecturer Nutrition

and Dietetics

A.J. Hure PhD AdvAPD, HMRI Public Health Postdoctoral Fellow

T.L. Burrows PhD APD, Lecturer in Nutrition and Dietetics

M.L. Blumfield PhD (Nutr&Diet) APD, Postdoctoral researcher

R. Smith PhD, Professor

C.E. Collins PhD (Nutr&Diet) AdvAPD FDAA, Professor in Nutrition

and Dietetics

Correspondence: C.E. Collins, School of Health Sciences, Faculty of

Health and Medicine, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW

2308, Australia. Email: Clare.Collins@newcastle.edu.au

Accepted April 2015

bs_bs_banner

Nutrition & Dietetics 2015; ••: ••–•• DOI: 10.1111/1747-0080.12203

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia 1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

converting the Nutrient Reference Values (NRVs) into com-

binations of types and amounts of foods within the core food

groups to meet the nutritional requirements of each age and

gendergroup,factoring in heightand physicalactivity

levels.11 The information was simplified into the AGHE,a

user-friendly food selection guide.9

NRVs outline the average nutrientrequirements needed

on a daily basisto meetphysiologicalfunction and to

prevent deficiency or chronic disease.12 NRVs for population

average intakes are termed ‘estimated average requirements’

(EARs) and ‘adequate intakes’(AIs).12 The EAR refers to the

everyday nutrient intake levelneeded to meet the require-

mentsof 50% of the healthypopulation in aspecific

life-stage and gender group.12 When an EAR cannot be deter-

mined, then an AI, which is the average daily nutrient intake

levelthatis likely to be sufficient,based on observed or

experimentally determined estimation of nutrient intake by

an apparently healthy cohort, is used.12 The Upper Level of

Intake (UL) refers to the maximum average daily nutrient

intake levellikely to have no adverse health effects to the

majority of individuals in the general population.12

No studieshave examined and compared the dietary

intakes of young Australian children aged two to three years

to the AGHE age-appropriate recommendationsthusfar.

This is because prior to 2013,there were no quantitative

dietary guidelines for children less than four years ofage,

limiting the comparison of dietary patterns in this age group

to age-appropriate standards.13 The 1995 National Nutrition

Survey (NNS),14 the 2007 Australian NationalChildren’s

Nutrition and PhysicalActivity Survey (ANCNPAS),15 the

Childhood Asthma Prevention Study (CAPS),16 and the 2010

Australian NationalInfantFeeding Survey:Indicator Results17

have allincluded young children,but were only able to

describe food and nutrientintakesin reference to older

children,rather than evaluating intakes based on compari-

son with age-appropriatenationalfood group serving

recommendations.

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the dietary

intakes of a sample of Australian children aged two to three

years met:(i) the minimum recommended age-appropriate

daily food group servings in the AGHE, and (ii) the NRVs for

vitamin A, thiamin, folate, calcium, iron and zinc.

Methods

This is a secondary data analysis of child dietary intakes from

the Women and Their Children’s Health (WATCH) cohort.18

Pregnant women less than 18 gestational weeks were eligible

to participate in the WATCH study.18 Participants needed to

reside locally and be able to be present at the arranged study

visits at the John Hunter Hospital.18 Between June 2006 and

December 2007, 180 eligible participants were recruited to

the study through various approaches, such as via research

midwives at the John Hunter Hospital antenatal clinic, local

media coverage and by word ofmouth.18 The majority of

participants (n = 133,74% ofsample)remained enrolled

two years after study commencement, although not all par-

ticipants completed all components at study visits.18 Ethics

approvalfor the WATCH study wasobtained from the

Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee

and the University ofNewcastle Human Research Ethics

Committee.

Standardised proceduresof data collection were used,

with detailed methodspublished elsewhere.18,19 Briefly,

anthropometry measurements and dietary intakes forthe

mothers and children were collected by qualified dietitians

at the annualstudy visit.18 Data on socio-economic status,

health and lifestyle variables were also obtained via a self-

reported questionnaire at the first study visit.18 Dietary data

of 57 children aged two to three years, including one set of

twins, were available for the current analysis.

The toddler version of the Australian Child and Adoles-

cent Eating Survey (ACAES) was used to evaluate the dietar

intake of children at age two or three years.20 The ACAES is

a 120-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire

(FFQ) that was previouslyvalidated forenergyintake

using the gold-standard doubly labelled water method in

Australian children,21–24 including those aged two to three

years.20,22,23

Mothers were asked to complete the ACAES for

their child’s intake over the past six months as this reporting

period is designed to capture children’s usual eating habits.25

An individual response is required for each food item in the

ACAES, with varied frequency options ranging from ‘never’

to ‘four or more times per day’,18 and for some beverages up

to ‘seven or more glasses per day’.20 Toddler-specific portion

sizes were derived from the 2007 ANCNPAS15 unpublished

data purchased from the Australian SocialScience Data

Archive,Australian NationalUniversity.20 Additionalques-

tionsregarding food-related behavioursare described in

detail elsewhere.18 FFQs were included if they had less than

five missing responses,with three FFQs excluded for this

reason.

Raw data from the FFQ were entered into FoodWorks

Professional(Xyris Software,Brisbane,QLD, Australia)

based on AUSNUT 2007 to derive the amount (weight mass)

of daily food consumption and nutrient intakes. Food con-

sumption data were then exported into MicrosoftExcel

(MicrosoftCooperation,2010, Seattle,United States)

spreadsheets and categorised into food groups correspond-

ing to the core and discretionary groups of AGHE,9 which

has been published previously26 and reported in a number of

studies.22,27,28

Food portions were converted into a number of

servings based on the AGHE standard serving sizes.9 When

food items were not specified in the AGHE,standard por-

tions were derived based on similar energy values of other

food items in the same AGHE food group.For example,a

standard portion of cheese spread/cream cheese was deeme

to be 55 g as this amount provides a similar energy value to

the standard serving size of plain milk (250 mL), hard chees

(40 g) and ricotta cheese (120 g). To calculate consumption

of combination dishes, foods were broken into their compo-

nentingredientsand assigned into the appropriate food

groups.For example,the food item ‘beef/lamb pieces with

vegetables’was disaggregated into meat and vegetables food

groups in the weight ratio of 2:1. Foods that do not fit into

any of the core food groups were evaluated as ‘discretionary

L.K. Chai et al.

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia2

binations of types and amounts of foods within the core food

groups to meet the nutritional requirements of each age and

gendergroup,factoring in heightand physicalactivity

levels.11 The information was simplified into the AGHE,a

user-friendly food selection guide.9

NRVs outline the average nutrientrequirements needed

on a daily basisto meetphysiologicalfunction and to

prevent deficiency or chronic disease.12 NRVs for population

average intakes are termed ‘estimated average requirements’

(EARs) and ‘adequate intakes’(AIs).12 The EAR refers to the

everyday nutrient intake levelneeded to meet the require-

mentsof 50% of the healthypopulation in aspecific

life-stage and gender group.12 When an EAR cannot be deter-

mined, then an AI, which is the average daily nutrient intake

levelthatis likely to be sufficient,based on observed or

experimentally determined estimation of nutrient intake by

an apparently healthy cohort, is used.12 The Upper Level of

Intake (UL) refers to the maximum average daily nutrient

intake levellikely to have no adverse health effects to the

majority of individuals in the general population.12

No studieshave examined and compared the dietary

intakes of young Australian children aged two to three years

to the AGHE age-appropriate recommendationsthusfar.

This is because prior to 2013,there were no quantitative

dietary guidelines for children less than four years ofage,

limiting the comparison of dietary patterns in this age group

to age-appropriate standards.13 The 1995 National Nutrition

Survey (NNS),14 the 2007 Australian NationalChildren’s

Nutrition and PhysicalActivity Survey (ANCNPAS),15 the

Childhood Asthma Prevention Study (CAPS),16 and the 2010

Australian NationalInfantFeeding Survey:Indicator Results17

have allincluded young children,but were only able to

describe food and nutrientintakesin reference to older

children,rather than evaluating intakes based on compari-

son with age-appropriatenationalfood group serving

recommendations.

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the dietary

intakes of a sample of Australian children aged two to three

years met:(i) the minimum recommended age-appropriate

daily food group servings in the AGHE, and (ii) the NRVs for

vitamin A, thiamin, folate, calcium, iron and zinc.

Methods

This is a secondary data analysis of child dietary intakes from

the Women and Their Children’s Health (WATCH) cohort.18

Pregnant women less than 18 gestational weeks were eligible

to participate in the WATCH study.18 Participants needed to

reside locally and be able to be present at the arranged study

visits at the John Hunter Hospital.18 Between June 2006 and

December 2007, 180 eligible participants were recruited to

the study through various approaches, such as via research

midwives at the John Hunter Hospital antenatal clinic, local

media coverage and by word ofmouth.18 The majority of

participants (n = 133,74% ofsample)remained enrolled

two years after study commencement, although not all par-

ticipants completed all components at study visits.18 Ethics

approvalfor the WATCH study wasobtained from the

Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee

and the University ofNewcastle Human Research Ethics

Committee.

Standardised proceduresof data collection were used,

with detailed methodspublished elsewhere.18,19 Briefly,

anthropometry measurements and dietary intakes forthe

mothers and children were collected by qualified dietitians

at the annualstudy visit.18 Data on socio-economic status,

health and lifestyle variables were also obtained via a self-

reported questionnaire at the first study visit.18 Dietary data

of 57 children aged two to three years, including one set of

twins, were available for the current analysis.

The toddler version of the Australian Child and Adoles-

cent Eating Survey (ACAES) was used to evaluate the dietar

intake of children at age two or three years.20 The ACAES is

a 120-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire

(FFQ) that was previouslyvalidated forenergyintake

using the gold-standard doubly labelled water method in

Australian children,21–24 including those aged two to three

years.20,22,23

Mothers were asked to complete the ACAES for

their child’s intake over the past six months as this reporting

period is designed to capture children’s usual eating habits.25

An individual response is required for each food item in the

ACAES, with varied frequency options ranging from ‘never’

to ‘four or more times per day’,18 and for some beverages up

to ‘seven or more glasses per day’.20 Toddler-specific portion

sizes were derived from the 2007 ANCNPAS15 unpublished

data purchased from the Australian SocialScience Data

Archive,Australian NationalUniversity.20 Additionalques-

tionsregarding food-related behavioursare described in

detail elsewhere.18 FFQs were included if they had less than

five missing responses,with three FFQs excluded for this

reason.

Raw data from the FFQ were entered into FoodWorks

Professional(Xyris Software,Brisbane,QLD, Australia)

based on AUSNUT 2007 to derive the amount (weight mass)

of daily food consumption and nutrient intakes. Food con-

sumption data were then exported into MicrosoftExcel

(MicrosoftCooperation,2010, Seattle,United States)

spreadsheets and categorised into food groups correspond-

ing to the core and discretionary groups of AGHE,9 which

has been published previously26 and reported in a number of

studies.22,27,28

Food portions were converted into a number of

servings based on the AGHE standard serving sizes.9 When

food items were not specified in the AGHE,standard por-

tions were derived based on similar energy values of other

food items in the same AGHE food group.For example,a

standard portion of cheese spread/cream cheese was deeme

to be 55 g as this amount provides a similar energy value to

the standard serving size of plain milk (250 mL), hard chees

(40 g) and ricotta cheese (120 g). To calculate consumption

of combination dishes, foods were broken into their compo-

nentingredientsand assigned into the appropriate food

groups.For example,the food item ‘beef/lamb pieces with

vegetables’was disaggregated into meat and vegetables food

groups in the weight ratio of 2:1. Foods that do not fit into

any of the core food groups were evaluated as ‘discretionary

L.K. Chai et al.

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia2

foods’.9 Nutrient intake data were compared with the NRVs

to assess nutritional adequacy.

All data manipulation and statistical analyses was under-

taken using JMP (version 10,SAS Institute Inc.,Cary,NC,

1989–2007). Results were considered statistically significant

with P-values <0.05. Descriptive statistics were undertaken

to describe maternal and child characteristics by age groups.

Demographic characteristics of mothers (n = 53) were com-

pared to the baseline sample (n = 177) using t-tests.Body

mass index (BMI) z-scores for the children were calculated

using the LMS statistical method.29 Main outcome measures

included children’s daily consumption ofthe AGHE food

groups, macronutrients, and micronutrients; and the propor-

tion of children meeting recommendations as per the AGHE

and NRVs by age groups.The majority of dietary variables

were normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk Goodness ofFit

tests).Differences between dietary intakes ofchildren and

the AGHE recommended numberof daily servingswere

assessed using t-tests. The initial analysis included the whole

sample and all nutrients. Individual mean daily macronutri-

ent and micronutrient intakes were compared to the EAR or

AI to assesswhetherthe children in thisstudy metthe

NRVs.12 Selected nutrients important for healthy growth and

development were investigated in the subsample (n = 47) in

addition to the number ofdaily servings from the AGHE

food groups to investigate differentaspects ofdiet.Daily

food groups and macronutrientintakes were assessed for

thosemeeting theEARs for vitamin A,thiamin,folate,

calcium, iron and zinc. These nutrients were selected as key

nutrients for health and were deemed as most important for

children’s development and health.30,31They also represent

both fat-soluble and water-soluble vitamins,in addition to

minerals.12

Results

The majority of the mothers were aged between 25 and 34

years old at the age of delivery (62%),married (68%) and

had attained post-year 12 educational qualifications (55%).

No significant difference was found between these maternal

characteristics compared to baseline data.Young children

(n = 54) in the current study were aged two to three years

(mean age 2.7 years) with equalnumbers of boys (n = 27)

and girls (n = 27).The group mean BMI ± standard devia-

tion (SD) was 16.4 kg/m2 ± 1.6.Using the LMS statistical

method,29 the mean z-scores ± SD for weight was 0.4 ± 1.1,

height 0.5 ± 1.1, and BMI 0.1 ± 1.0.

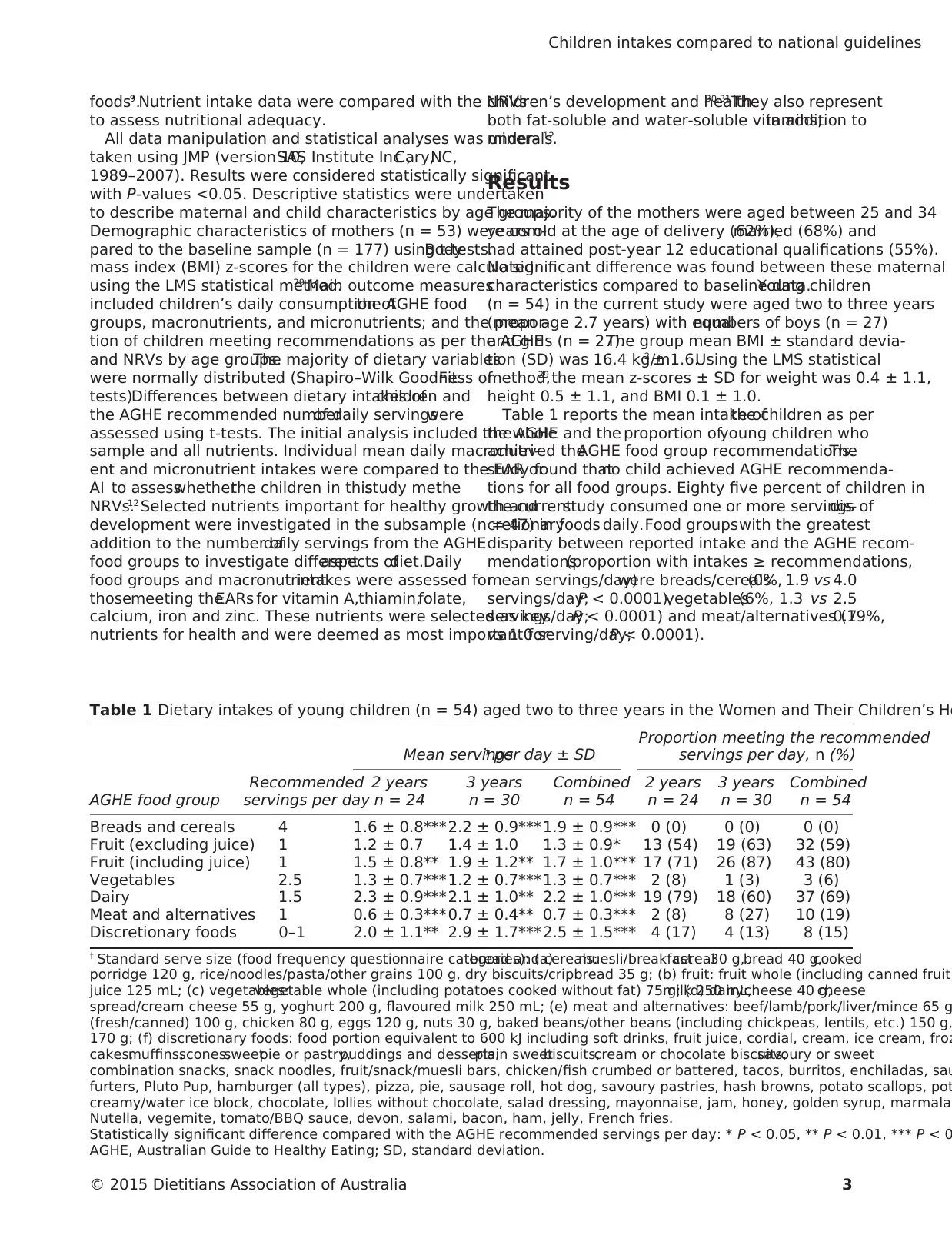

Table 1 reports the mean intake ofthe children as per

the AGHE and the proportion ofyoung children who

achieved theAGHE food group recommendations.The

study found thatno child achieved AGHE recommenda-

tions for all food groups. Eighty five percent of children in

the currentstudy consumed one or more servings ofdis-

cretionaryfoods daily.Food groupswith the greatest

disparity between reported intake and the AGHE recom-

mendations(proportion with intakes ≥ recommendations,

mean servings/day)were breads/cereals(0%, 1.9 vs 4.0

servings/day;P < 0.0001),vegetables(6%, 1.3 vs 2.5

servings/day;P < 0.0001) and meat/alternatives (19%,0.7

vs 1.0 serving/day;P < 0.0001).

Table 1 Dietary intakes of young children (n = 54) aged two to three years in the Women and Their Children’s He

AGHE food group

Recommended

servings per day

Mean servings† per day ± SD

Proportion meeting the recommended

servings per day, n (%)

2 years 3 years Combined 2 years 3 years Combined

n = 24 n = 30 n = 54 n = 24 n = 30 n = 54

Breads and cereals 4 1.6 ± 0.8*** 2.2 ± 0.9***1.9 ± 0.9*** 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0)

Fruit (excluding juice) 1 1.2 ± 0.7 1.4 ± 1.0 1.3 ± 0.9* 13 (54) 19 (63) 32 (59)

Fruit (including juice) 1 1.5 ± 0.8** 1.9 ± 1.2** 1.7 ± 1.0*** 17 (71) 26 (87) 43 (80)

Vegetables 2.5 1.3 ± 0.7*** 1.2 ± 0.7***1.3 ± 0.7*** 2 (8) 1 (3) 3 (6)

Dairy 1.5 2.3 ± 0.9*** 2.1 ± 1.0** 2.2 ± 1.0*** 19 (79) 18 (60) 37 (69)

Meat and alternatives 1 0.6 ± 0.3*** 0.7 ± 0.4** 0.7 ± 0.3*** 2 (8) 8 (27) 10 (19)

Discretionary foods 0–1 2.0 ± 1.1** 2.9 ± 1.7*** 2.5 ± 1.5*** 4 (17) 4 (13) 8 (15)

† Standard serve size (food frequency questionnaire categories): (a)bread and cereals:muesli/breakfastcereal30 g,bread 40 g,cooked

porridge 120 g, rice/noodles/pasta/other grains 100 g, dry biscuits/cripbread 35 g; (b) fruit: fruit whole (including canned fruit)

juice 125 mL; (c) vegetables:vegetable whole (including potatoes cooked without fat) 75 g; (d) dairy:milk 250 mL,cheese 40 g,cheese

spread/cream cheese 55 g, yoghurt 200 g, flavoured milk 250 mL; (e) meat and alternatives: beef/lamb/pork/liver/mince 65 g

(fresh/canned) 100 g, chicken 80 g, eggs 120 g, nuts 30 g, baked beans/other beans (including chickpeas, lentils, etc.) 150 g,

170 g; (f) discretionary foods: food portion equivalent to 600 kJ including soft drinks, fruit juice, cordial, cream, ice cream, froz

cakes,muffins,scones,sweetpie or pastry,puddings and desserts,plain sweetbiscuits,cream or chocolate biscuits,savoury or sweet

combination snacks, snack noodles, fruit/snack/muesli bars, chicken/fish crumbed or battered, tacos, burritos, enchiladas, sau

furters, Pluto Pup, hamburger (all types), pizza, pie, sausage roll, hot dog, savoury pastries, hash browns, potato scallops, pot

creamy/water ice block, chocolate, lollies without chocolate, salad dressing, mayonnaise, jam, honey, golden syrup, marmalad

Nutella, vegemite, tomato/BBQ sauce, devon, salami, bacon, ham, jelly, French fries.

Statistically significant difference compared with the AGHE recommended servings per day: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0

AGHE, Australian Guide to Healthy Eating; SD, standard deviation.

Children intakes compared to national guidelines

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia 3

to assess nutritional adequacy.

All data manipulation and statistical analyses was under-

taken using JMP (version 10,SAS Institute Inc.,Cary,NC,

1989–2007). Results were considered statistically significant

with P-values <0.05. Descriptive statistics were undertaken

to describe maternal and child characteristics by age groups.

Demographic characteristics of mothers (n = 53) were com-

pared to the baseline sample (n = 177) using t-tests.Body

mass index (BMI) z-scores for the children were calculated

using the LMS statistical method.29 Main outcome measures

included children’s daily consumption ofthe AGHE food

groups, macronutrients, and micronutrients; and the propor-

tion of children meeting recommendations as per the AGHE

and NRVs by age groups.The majority of dietary variables

were normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk Goodness ofFit

tests).Differences between dietary intakes ofchildren and

the AGHE recommended numberof daily servingswere

assessed using t-tests. The initial analysis included the whole

sample and all nutrients. Individual mean daily macronutri-

ent and micronutrient intakes were compared to the EAR or

AI to assesswhetherthe children in thisstudy metthe

NRVs.12 Selected nutrients important for healthy growth and

development were investigated in the subsample (n = 47) in

addition to the number ofdaily servings from the AGHE

food groups to investigate differentaspects ofdiet.Daily

food groups and macronutrientintakes were assessed for

thosemeeting theEARs for vitamin A,thiamin,folate,

calcium, iron and zinc. These nutrients were selected as key

nutrients for health and were deemed as most important for

children’s development and health.30,31They also represent

both fat-soluble and water-soluble vitamins,in addition to

minerals.12

Results

The majority of the mothers were aged between 25 and 34

years old at the age of delivery (62%),married (68%) and

had attained post-year 12 educational qualifications (55%).

No significant difference was found between these maternal

characteristics compared to baseline data.Young children

(n = 54) in the current study were aged two to three years

(mean age 2.7 years) with equalnumbers of boys (n = 27)

and girls (n = 27).The group mean BMI ± standard devia-

tion (SD) was 16.4 kg/m2 ± 1.6.Using the LMS statistical

method,29 the mean z-scores ± SD for weight was 0.4 ± 1.1,

height 0.5 ± 1.1, and BMI 0.1 ± 1.0.

Table 1 reports the mean intake ofthe children as per

the AGHE and the proportion ofyoung children who

achieved theAGHE food group recommendations.The

study found thatno child achieved AGHE recommenda-

tions for all food groups. Eighty five percent of children in

the currentstudy consumed one or more servings ofdis-

cretionaryfoods daily.Food groupswith the greatest

disparity between reported intake and the AGHE recom-

mendations(proportion with intakes ≥ recommendations,

mean servings/day)were breads/cereals(0%, 1.9 vs 4.0

servings/day;P < 0.0001),vegetables(6%, 1.3 vs 2.5

servings/day;P < 0.0001) and meat/alternatives (19%,0.7

vs 1.0 serving/day;P < 0.0001).

Table 1 Dietary intakes of young children (n = 54) aged two to three years in the Women and Their Children’s He

AGHE food group

Recommended

servings per day

Mean servings† per day ± SD

Proportion meeting the recommended

servings per day, n (%)

2 years 3 years Combined 2 years 3 years Combined

n = 24 n = 30 n = 54 n = 24 n = 30 n = 54

Breads and cereals 4 1.6 ± 0.8*** 2.2 ± 0.9***1.9 ± 0.9*** 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0)

Fruit (excluding juice) 1 1.2 ± 0.7 1.4 ± 1.0 1.3 ± 0.9* 13 (54) 19 (63) 32 (59)

Fruit (including juice) 1 1.5 ± 0.8** 1.9 ± 1.2** 1.7 ± 1.0*** 17 (71) 26 (87) 43 (80)

Vegetables 2.5 1.3 ± 0.7*** 1.2 ± 0.7***1.3 ± 0.7*** 2 (8) 1 (3) 3 (6)

Dairy 1.5 2.3 ± 0.9*** 2.1 ± 1.0** 2.2 ± 1.0*** 19 (79) 18 (60) 37 (69)

Meat and alternatives 1 0.6 ± 0.3*** 0.7 ± 0.4** 0.7 ± 0.3*** 2 (8) 8 (27) 10 (19)

Discretionary foods 0–1 2.0 ± 1.1** 2.9 ± 1.7*** 2.5 ± 1.5*** 4 (17) 4 (13) 8 (15)

† Standard serve size (food frequency questionnaire categories): (a)bread and cereals:muesli/breakfastcereal30 g,bread 40 g,cooked

porridge 120 g, rice/noodles/pasta/other grains 100 g, dry biscuits/cripbread 35 g; (b) fruit: fruit whole (including canned fruit)

juice 125 mL; (c) vegetables:vegetable whole (including potatoes cooked without fat) 75 g; (d) dairy:milk 250 mL,cheese 40 g,cheese

spread/cream cheese 55 g, yoghurt 200 g, flavoured milk 250 mL; (e) meat and alternatives: beef/lamb/pork/liver/mince 65 g

(fresh/canned) 100 g, chicken 80 g, eggs 120 g, nuts 30 g, baked beans/other beans (including chickpeas, lentils, etc.) 150 g,

170 g; (f) discretionary foods: food portion equivalent to 600 kJ including soft drinks, fruit juice, cordial, cream, ice cream, froz

cakes,muffins,scones,sweetpie or pastry,puddings and desserts,plain sweetbiscuits,cream or chocolate biscuits,savoury or sweet

combination snacks, snack noodles, fruit/snack/muesli bars, chicken/fish crumbed or battered, tacos, burritos, enchiladas, sau

furters, Pluto Pup, hamburger (all types), pizza, pie, sausage roll, hot dog, savoury pastries, hash browns, potato scallops, pot

creamy/water ice block, chocolate, lollies without chocolate, salad dressing, mayonnaise, jam, honey, golden syrup, marmalad

Nutella, vegemite, tomato/BBQ sauce, devon, salami, bacon, ham, jelly, French fries.

Statistically significant difference compared with the AGHE recommended servings per day: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0

AGHE, Australian Guide to Healthy Eating; SD, standard deviation.

Children intakes compared to national guidelines

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia 3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

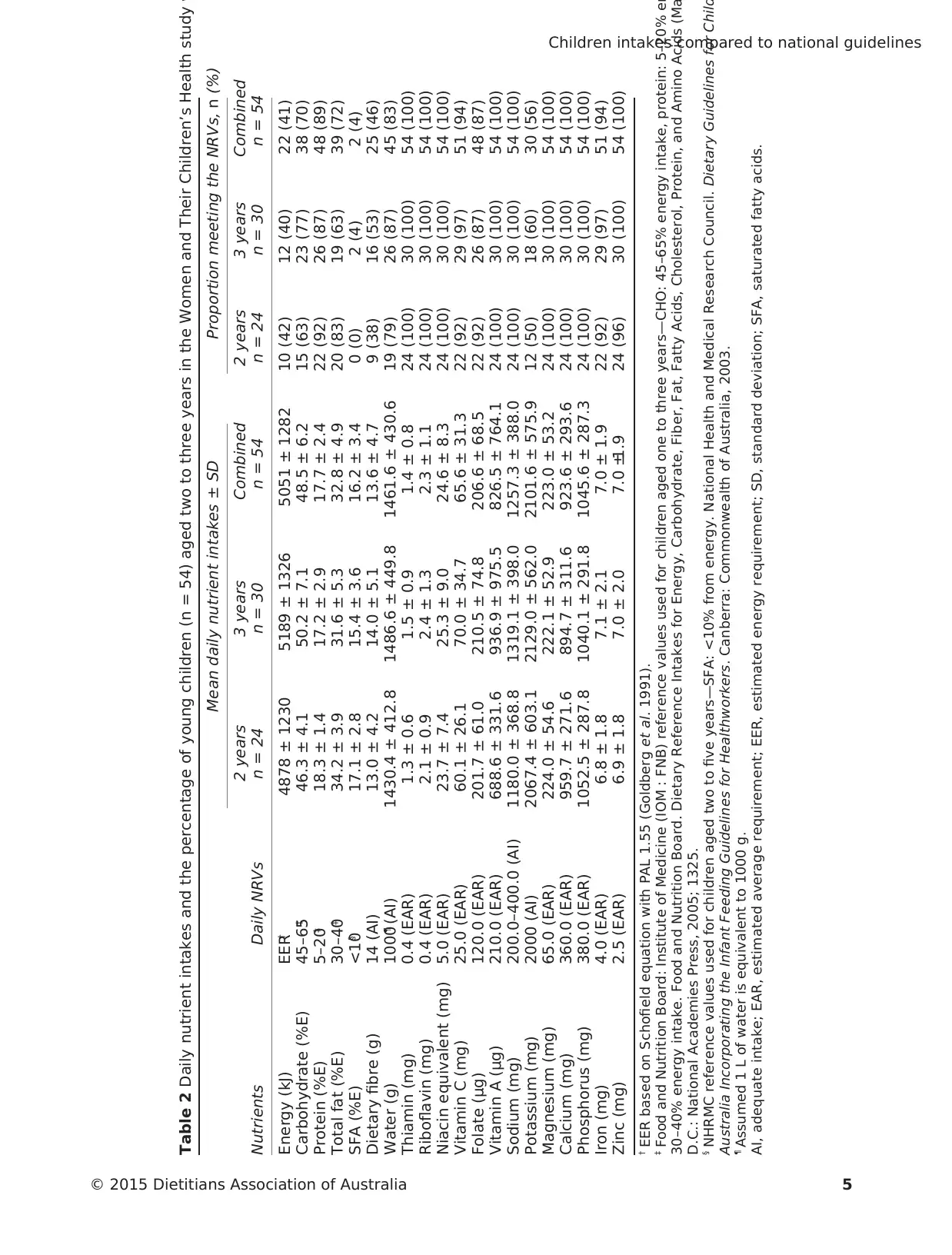

The nutrient profile and the proportion of children who

achieved the age-appropriate NRVs are presented in Table 2.

The mean macronutrient profile was: 48.5% of total energy

intake (%E) from carbohydrate,17.7%E from protein and

32.8%E from total fat, including 16%E from saturated fatty

acids(SFAs).The greatestdisparitiesbetween children’s

intakes and recommendations were observed in dietary fibre

and potassium,where 46% and 56% ofchildren metthe

target respectively. In addition, 50% of children exceeded the

UL for zinc12 and 96% ofchildren exceeded the National

Health and Medical Research Council SFA recommendation

of <10% of energy intake.32 For the remaining nutrients, at

least 83% of children met the respective NRV.

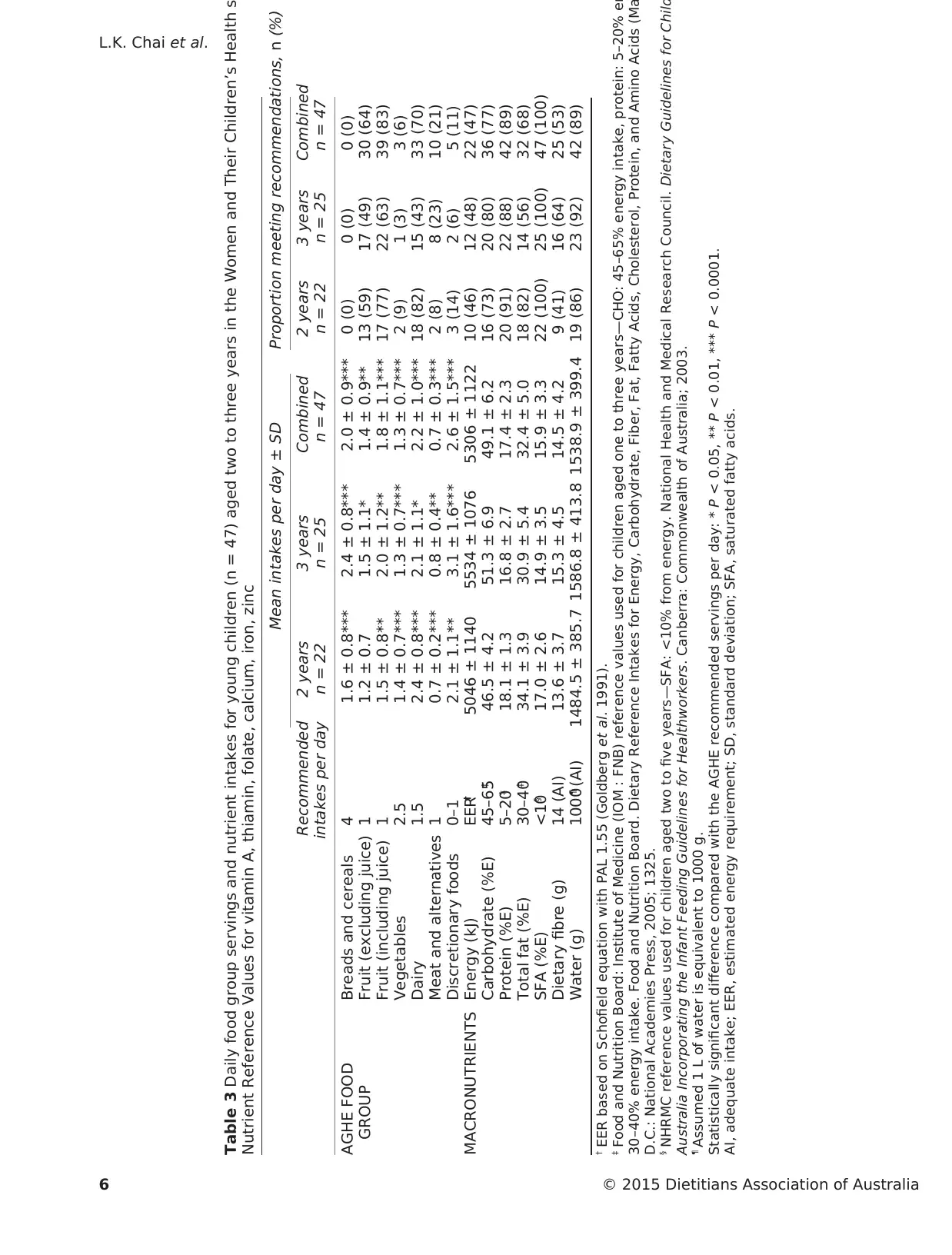

Further analysis was undertaken on a subsample of chil-

dren (n = 47)who metthe EARs for vitamin A,thiamin,

folate,calcium,iron and zinc,to evaluate their core food

group and macronutrient intakes (Table 3). The macronutri-

ent intakes of this subgroup were similar to the main study

sample (n = 54) with 100% of children meeting the relevant

NRVs,12 although intakesof SFA exceeded recommenda-

tions.32 This subgroup had significantly higher mean daily

servings of fruit, excluding juice (1.4 vs 1.0; P < 0.05), dairy

(2.2 vs 1.5; P < 0.001) and discretionary foods (2.6 vs ≤ 1.0;

P < 0.001),plus significantly lower mean daily servings of

breads and cereals (2.0 vs 4.0; P < 0.001), vegetables (1.3 vs

2.5; P < 0.001) and meat (0.7 vs 1.0; P < 0.001) compared

with the AGHE recommendations.

Discussion

This is the firstAustralian study to compare the dietary

patterns of children aged two to three years to the current

AGHE age-appropriate daily food group serving recommen-

dations.The study found thatno child achieved AGHE

recommendations for all food groups. The majority of chil-

dren had daily food group serving intakesbelow AGHE

recommendations for the bread/cereals, vegetables and meat/

alternatives groups.This is similar to the 2007 ANCNPAS

where 86–90% of children aged two to three were eating at

least one to three servings/day of fruit (including juice) but

less than two servings/day ofvegetables (including pota-

toes).15 The consumption ofcereals,meat,dairy products

and discretionary foods cannot be directly compared to the

previous study due to changes in the standard serving sizes

in the AGHE between the two analyses.The ANCNPAS

assessed dietary intake via 24-hour recalls.Parents or care

givers reported child intakes for the preceding 24 hours and

therefore may notreflectusualintake.33,34 In the current

study,child dietary intake was measured using a validated

FFQ20,22,23

and compared to the 2013 AGHE, which includes

serving sizes and recommendations specifically for young

children aged two to three years.Hence,the results in the

currentanalysismay betterrepresentusualchild dietary

patterns.

The common discretionary foodsconsumed included

snack bars,cakes and muffins,sweetbiscuits,and potato

chips/French fries, which contributed to an average 28% of

total energy intake in the young children within the current

study. ‘Discretionary foods’are high in energy, added sugars,

salt,and saturated fatand therefore should be eaten less

often and in limited amounts.9 In the 1995 NNS,2007

ANCNPAS and the Feeding Healthy Foods to Kids,discre-

tionary foods were over-consumed by Australian children

aged two to three years,contributing to 33%E,35%E and

29%E, respectively.28,35 Australian toddlers(aged 16–24

months) in the CAPS study also reported high intakes of

discretionary foods,contributing to 25–30%E.36 Evidence

shows discretionary foods displace nutrient dense foods and

are negatively associated with protein and micronutrient

intakes.36 These results raise concern regarding a relatively

consistenthigh consumption (25–35%E)of discretionary

foods among young children over the last decade.

The mean macronutrientdistributionsin the current

study were mostly within the acceptable ranges,although

SFA intakes exceeded recommendations and dietary fibre

was below recommendations.Thesefindingsweresup-

ported by a survey conducted in a larger sample of young

Australian children of a similar age. A cross-sectional survey

involving children aged one to five years (n = 300) in South

Australia found similar results with 50%E (vs 48.5%E) from

carbohydrate,17%E (vs17.7%E)from protein,33%E (vs

32.8%E) from fat,and 16%E (vs 16%E) from SFA.37 Fibre

intake in the currentstudy (13.6 g/day)wasabove that

assessed in children two to three years (10.4 g/day) in South

Australia,and about equalto the AI of14 g/day.The con-

sistency ofthe dietary patternsamong young Australian

children in differentstates warrants the conductof future

studies in a nationally representative population sample.

High SFA intakes in the currentstudy were related to

intakes offull-fatdairy products and discretionary foods,

which were the main sourcesof SFA. Five outof eight

children who met the AGHE recommendations for discre-

tionary foods (up to one serving/day) also met the EARs for

selected nutrients.However,only 4% ofchildren metthe

guidelines32 for consuming <10% of total energy from SFA,

compared to 15–16% oftwo to three yearolds in 2007

ANCNPAS.15 This finding is consistent with the South Aus-

tralian study,37 which found that only 5% of children older

than two years had an SFA intake within the recommenda-

tions,32 with milk and other dairy products also the most

common sources ofSFA.The Australia Dietary Guidelines

for children and adolescents32 recommend reduced-fat dairy

products from age two years. Hence children in the current

study would have been at the age where a transition from

full-fat dairy products to reduced-fat varieties is appropriate

meaningthat dairy as a majorSFA sourcewas to be

expected. Given that 28%E was derived from discretionary

foods, it is not surprising that SFA intakes were high.

The micronutrientintakes in the currentstudy metor

exceeded allage-specificNRVs, with the exception of

vitamin C,iron, folate and potassium.This is similarto

ANCNPAS where notall two to three year olds mettheir

NRVs for vitamin C, iron and calcium.15 Moreover, 50% of

the children in the current study exceeded the UL for zinc.

These results also agree with ANCNPAS.15 In both studies

the primary dietary sources of zinc were milk products, mea

L.K. Chai et al.

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia4

achieved the age-appropriate NRVs are presented in Table 2.

The mean macronutrient profile was: 48.5% of total energy

intake (%E) from carbohydrate,17.7%E from protein and

32.8%E from total fat, including 16%E from saturated fatty

acids(SFAs).The greatestdisparitiesbetween children’s

intakes and recommendations were observed in dietary fibre

and potassium,where 46% and 56% ofchildren metthe

target respectively. In addition, 50% of children exceeded the

UL for zinc12 and 96% ofchildren exceeded the National

Health and Medical Research Council SFA recommendation

of <10% of energy intake.32 For the remaining nutrients, at

least 83% of children met the respective NRV.

Further analysis was undertaken on a subsample of chil-

dren (n = 47)who metthe EARs for vitamin A,thiamin,

folate,calcium,iron and zinc,to evaluate their core food

group and macronutrient intakes (Table 3). The macronutri-

ent intakes of this subgroup were similar to the main study

sample (n = 54) with 100% of children meeting the relevant

NRVs,12 although intakesof SFA exceeded recommenda-

tions.32 This subgroup had significantly higher mean daily

servings of fruit, excluding juice (1.4 vs 1.0; P < 0.05), dairy

(2.2 vs 1.5; P < 0.001) and discretionary foods (2.6 vs ≤ 1.0;

P < 0.001),plus significantly lower mean daily servings of

breads and cereals (2.0 vs 4.0; P < 0.001), vegetables (1.3 vs

2.5; P < 0.001) and meat (0.7 vs 1.0; P < 0.001) compared

with the AGHE recommendations.

Discussion

This is the firstAustralian study to compare the dietary

patterns of children aged two to three years to the current

AGHE age-appropriate daily food group serving recommen-

dations.The study found thatno child achieved AGHE

recommendations for all food groups. The majority of chil-

dren had daily food group serving intakesbelow AGHE

recommendations for the bread/cereals, vegetables and meat/

alternatives groups.This is similar to the 2007 ANCNPAS

where 86–90% of children aged two to three were eating at

least one to three servings/day of fruit (including juice) but

less than two servings/day ofvegetables (including pota-

toes).15 The consumption ofcereals,meat,dairy products

and discretionary foods cannot be directly compared to the

previous study due to changes in the standard serving sizes

in the AGHE between the two analyses.The ANCNPAS

assessed dietary intake via 24-hour recalls.Parents or care

givers reported child intakes for the preceding 24 hours and

therefore may notreflectusualintake.33,34 In the current

study,child dietary intake was measured using a validated

FFQ20,22,23

and compared to the 2013 AGHE, which includes

serving sizes and recommendations specifically for young

children aged two to three years.Hence,the results in the

currentanalysismay betterrepresentusualchild dietary

patterns.

The common discretionary foodsconsumed included

snack bars,cakes and muffins,sweetbiscuits,and potato

chips/French fries, which contributed to an average 28% of

total energy intake in the young children within the current

study. ‘Discretionary foods’are high in energy, added sugars,

salt,and saturated fatand therefore should be eaten less

often and in limited amounts.9 In the 1995 NNS,2007

ANCNPAS and the Feeding Healthy Foods to Kids,discre-

tionary foods were over-consumed by Australian children

aged two to three years,contributing to 33%E,35%E and

29%E, respectively.28,35 Australian toddlers(aged 16–24

months) in the CAPS study also reported high intakes of

discretionary foods,contributing to 25–30%E.36 Evidence

shows discretionary foods displace nutrient dense foods and

are negatively associated with protein and micronutrient

intakes.36 These results raise concern regarding a relatively

consistenthigh consumption (25–35%E)of discretionary

foods among young children over the last decade.

The mean macronutrientdistributionsin the current

study were mostly within the acceptable ranges,although

SFA intakes exceeded recommendations and dietary fibre

was below recommendations.Thesefindingsweresup-

ported by a survey conducted in a larger sample of young

Australian children of a similar age. A cross-sectional survey

involving children aged one to five years (n = 300) in South

Australia found similar results with 50%E (vs 48.5%E) from

carbohydrate,17%E (vs17.7%E)from protein,33%E (vs

32.8%E) from fat,and 16%E (vs 16%E) from SFA.37 Fibre

intake in the currentstudy (13.6 g/day)wasabove that

assessed in children two to three years (10.4 g/day) in South

Australia,and about equalto the AI of14 g/day.The con-

sistency ofthe dietary patternsamong young Australian

children in differentstates warrants the conductof future

studies in a nationally representative population sample.

High SFA intakes in the currentstudy were related to

intakes offull-fatdairy products and discretionary foods,

which were the main sourcesof SFA. Five outof eight

children who met the AGHE recommendations for discre-

tionary foods (up to one serving/day) also met the EARs for

selected nutrients.However,only 4% ofchildren metthe

guidelines32 for consuming <10% of total energy from SFA,

compared to 15–16% oftwo to three yearolds in 2007

ANCNPAS.15 This finding is consistent with the South Aus-

tralian study,37 which found that only 5% of children older

than two years had an SFA intake within the recommenda-

tions,32 with milk and other dairy products also the most

common sources ofSFA.The Australia Dietary Guidelines

for children and adolescents32 recommend reduced-fat dairy

products from age two years. Hence children in the current

study would have been at the age where a transition from

full-fat dairy products to reduced-fat varieties is appropriate

meaningthat dairy as a majorSFA sourcewas to be

expected. Given that 28%E was derived from discretionary

foods, it is not surprising that SFA intakes were high.

The micronutrientintakes in the currentstudy metor

exceeded allage-specificNRVs, with the exception of

vitamin C,iron, folate and potassium.This is similarto

ANCNPAS where notall two to three year olds mettheir

NRVs for vitamin C, iron and calcium.15 Moreover, 50% of

the children in the current study exceeded the UL for zinc.

These results also agree with ANCNPAS.15 In both studies

the primary dietary sources of zinc were milk products, mea

L.K. Chai et al.

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table 2 Daily nutrient intakes and the percentage of young children (n = 54) aged two to three years in the Women and Their Children’s Health study w

Nutrients Daily NRVs

Mean daily nutrient intakes ± SD Proportion meeting the NRVs, n (%)

2 years

n = 24

3 years

n = 30

Combined 2 years 3 years Combined

n = 54 n = 24 n = 30 n = 54

Energy (kJ) EER† 4878 ± 1230 5189 ± 1326 5051 ± 1282 10 (42) 12 (40) 22 (41)

Carbohydrate (%E) 45–65‡ 46.3 ± 4.1 50.2 ± 7.1 48.5 ± 6.2 15 (63) 23 (77) 38 (70)

Protein (%E) 5–20‡ 18.3 ± 1.4 17.2 ± 2.9 17.7 ± 2.4 22 (92) 26 (87) 48 (89)

Total fat (%E) 30–40‡ 34.2 ± 3.9 31.6 ± 5.3 32.8 ± 4.9 20 (83) 19 (63) 39 (72)

SFA (%E) <10§ 17.1 ± 2.8 15.4 ± 3.6 16.2 ± 3.4 0 (0) 2 (4) 2 (4)

Dietary fibre (g) 14 (AI) 13.0 ± 4.2 14.0 ± 5.1 13.6 ± 4.7 9 (38) 16 (53) 25 (46)

Water (g) 1000¶ (AI) 1430.4 ± 412.8 1486.6 ± 449.8 1461.6 ± 430.6 19 (79) 26 (87) 45 (83)

Thiamin (mg) 0.4 (EAR) 1.3 ± 0.6 1.5 ± 0.9 1.4 ± 0.8 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Riboflavin (mg) 0.4 (EAR) 2.1 ± 0.9 2.4 ± 1.3 2.3 ± 1.1 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Niacin equivalent (mg) 5.0 (EAR) 23.7 ± 7.4 25.3 ± 9.0 24.6 ± 8.3 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Vitamin C (mg) 25.0 (EAR) 60.1 ± 26.1 70.0 ± 34.7 65.6 ± 31.3 22 (92) 29 (97) 51 (94)

Folate (μg) 120.0 (EAR) 201.7 ± 61.0 210.5 ± 74.8 206.6 ± 68.5 22 (92) 26 (87) 48 (87)

Vitamin A (μg) 210.0 (EAR) 688.6 ± 331.6 936.9 ± 975.5 826.5 ± 764.1 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Sodium (mg) 200.0–400.0 (AI) 1180.0 ± 368.8 1319.1 ± 398.0 1257.3 ± 388.0 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Potassium (mg) 2000 (AI) 2067.4 ± 603.1 2129.0 ± 562.0 2101.6 ± 575.9 12 (50) 18 (60) 30 (56)

Magnesium (mg) 65.0 (EAR) 224.0 ± 54.6 222.1 ± 52.9 223.0 ± 53.2 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Calcium (mg) 360.0 (EAR) 959.7 ± 271.6 894.7 ± 311.6 923.6 ± 293.6 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Phosphorus (mg) 380.0 (EAR) 1052.5 ± 287.8 1040.1 ± 291.8 1045.6 ± 287.3 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Iron (mg) 4.0 (EAR) 6.8 ± 1.8 7.1 ± 2.1 7.0 ± 1.9 22 (92) 29 (97) 51 (94)

Zinc (mg) 2.5 (EAR) 6.9 ± 1.8 7.0 ± 2.0 7.0 ±1.9 24 (96) 30 (100) 54 (100)

† EER based on Schofield equation with PAL 1.55 (Goldberg et al. 1991).

‡ Food and Nutrition Board: Institute of Medicine (IOM : FNB) reference values used for children aged one to three years—CHO: 45–65% energy intake, protein: 5–20% en

30–40% energy intake. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Ma

D.C.: National Academies Press, 2005; 1325.

§ NHRMC reference values used for children aged two to five years—SFA: <10% from energy. National Health and Medical Research Council. Dietary Guidelines for Child

Australia Incorporating the Infant Feeding Guidelines for Healthworkers. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2003.

¶ Assumed 1 L of water is equivalent to 1000 g.

AI, adequate intake; EAR, estimated average requirement; EER, estimated energy requirement; SD, standard deviation; SFA, saturated fatty acids.

Children intakes compared to national guidelines

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia 5

Nutrients Daily NRVs

Mean daily nutrient intakes ± SD Proportion meeting the NRVs, n (%)

2 years

n = 24

3 years

n = 30

Combined 2 years 3 years Combined

n = 54 n = 24 n = 30 n = 54

Energy (kJ) EER† 4878 ± 1230 5189 ± 1326 5051 ± 1282 10 (42) 12 (40) 22 (41)

Carbohydrate (%E) 45–65‡ 46.3 ± 4.1 50.2 ± 7.1 48.5 ± 6.2 15 (63) 23 (77) 38 (70)

Protein (%E) 5–20‡ 18.3 ± 1.4 17.2 ± 2.9 17.7 ± 2.4 22 (92) 26 (87) 48 (89)

Total fat (%E) 30–40‡ 34.2 ± 3.9 31.6 ± 5.3 32.8 ± 4.9 20 (83) 19 (63) 39 (72)

SFA (%E) <10§ 17.1 ± 2.8 15.4 ± 3.6 16.2 ± 3.4 0 (0) 2 (4) 2 (4)

Dietary fibre (g) 14 (AI) 13.0 ± 4.2 14.0 ± 5.1 13.6 ± 4.7 9 (38) 16 (53) 25 (46)

Water (g) 1000¶ (AI) 1430.4 ± 412.8 1486.6 ± 449.8 1461.6 ± 430.6 19 (79) 26 (87) 45 (83)

Thiamin (mg) 0.4 (EAR) 1.3 ± 0.6 1.5 ± 0.9 1.4 ± 0.8 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Riboflavin (mg) 0.4 (EAR) 2.1 ± 0.9 2.4 ± 1.3 2.3 ± 1.1 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Niacin equivalent (mg) 5.0 (EAR) 23.7 ± 7.4 25.3 ± 9.0 24.6 ± 8.3 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Vitamin C (mg) 25.0 (EAR) 60.1 ± 26.1 70.0 ± 34.7 65.6 ± 31.3 22 (92) 29 (97) 51 (94)

Folate (μg) 120.0 (EAR) 201.7 ± 61.0 210.5 ± 74.8 206.6 ± 68.5 22 (92) 26 (87) 48 (87)

Vitamin A (μg) 210.0 (EAR) 688.6 ± 331.6 936.9 ± 975.5 826.5 ± 764.1 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Sodium (mg) 200.0–400.0 (AI) 1180.0 ± 368.8 1319.1 ± 398.0 1257.3 ± 388.0 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Potassium (mg) 2000 (AI) 2067.4 ± 603.1 2129.0 ± 562.0 2101.6 ± 575.9 12 (50) 18 (60) 30 (56)

Magnesium (mg) 65.0 (EAR) 224.0 ± 54.6 222.1 ± 52.9 223.0 ± 53.2 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Calcium (mg) 360.0 (EAR) 959.7 ± 271.6 894.7 ± 311.6 923.6 ± 293.6 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Phosphorus (mg) 380.0 (EAR) 1052.5 ± 287.8 1040.1 ± 291.8 1045.6 ± 287.3 24 (100) 30 (100) 54 (100)

Iron (mg) 4.0 (EAR) 6.8 ± 1.8 7.1 ± 2.1 7.0 ± 1.9 22 (92) 29 (97) 51 (94)

Zinc (mg) 2.5 (EAR) 6.9 ± 1.8 7.0 ± 2.0 7.0 ±1.9 24 (96) 30 (100) 54 (100)

† EER based on Schofield equation with PAL 1.55 (Goldberg et al. 1991).

‡ Food and Nutrition Board: Institute of Medicine (IOM : FNB) reference values used for children aged one to three years—CHO: 45–65% energy intake, protein: 5–20% en

30–40% energy intake. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Ma

D.C.: National Academies Press, 2005; 1325.

§ NHRMC reference values used for children aged two to five years—SFA: <10% from energy. National Health and Medical Research Council. Dietary Guidelines for Child

Australia Incorporating the Infant Feeding Guidelines for Healthworkers. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2003.

¶ Assumed 1 L of water is equivalent to 1000 g.

AI, adequate intake; EAR, estimated average requirement; EER, estimated energy requirement; SD, standard deviation; SFA, saturated fatty acids.

Children intakes compared to national guidelines

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia 5

Table 3 Daily food group servings and nutrient intakes for young children (n = 47) aged two to three years in the Women and Their Children’s Health st

Nutrient Reference Values for vitamin A, thiamin, folate, calcium, iron, zinc

Recommended

intakes per day

Mean intakes per day ± SD Proportion meeting recommendations, n (%)

2 years 3 years Combined 2 years 3 years Combined

n = 22 n = 25 n = 47 n = 22 n = 25 n = 47

AGHE FOOD

GROUP

Breads and cereals 4 1.6 ± 0.8*** 2.4 ± 0.8*** 2.0 ± 0.9*** 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0)

Fruit (excluding juice) 1 1.2 ± 0.7 1.5 ± 1.1* 1.4 ± 0.9** 13 (59) 17 (49) 30 (64)

Fruit (including juice) 1 1.5 ± 0.8** 2.0 ± 1.2** 1.8 ± 1.1*** 17 (77) 22 (63) 39 (83)

Vegetables 2.5 1.4 ± 0.7*** 1.3 ± 0.7*** 1.3 ± 0.7*** 2 (9) 1 (3) 3 (6)

Dairy 1.5 2.4 ± 0.8*** 2.1 ± 1.1* 2.2 ± 1.0*** 18 (82) 15 (43) 33 (70)

Meat and alternatives 1 0.7 ± 0.2*** 0.8 ± 0.4** 0.7 ± 0.3*** 2 (8) 8 (23) 10 (21)

Discretionary foods 0–1 2.1 ± 1.1** 3.1 ± 1.6*** 2.6 ± 1.5*** 3 (14) 2 (6) 5 (11)

MACRONUTRIENTS Energy (kJ) EER† 5046 ± 1140 5534 ± 1076 5306 ± 1122 10 (46) 12 (48) 22 (47)

Carbohydrate (%E) 45–65‡ 46.5 ± 4.2 51.3 ± 6.9 49.1 ± 6.2 16 (73) 20 (80) 36 (77)

Protein (%E) 5–20‡ 18.1 ± 1.3 16.8 ± 2.7 17.4 ± 2.3 20 (91) 22 (88) 42 (89)

Total fat (%E) 30–40‡ 34.1 ± 3.9 30.9 ± 5.4 32.4 ± 5.0 18 (82) 14 (56) 32 (68)

SFA (%E) <10§ 17.0 ± 2.6 14.9 ± 3.5 15.9 ± 3.3 22 (100) 25 (100) 47 (100)

Dietary fibre (g) 14 (AI) 13.6 ± 3.7 15.3 ± 4.5 14.5 ± 4.2 9 (41) 16 (64) 25 (53)

Water (g) 1000¶ (AI) 1484.5 ± 385.7 1586.8 ± 413.8 1538.9 ± 399.4 19 (86) 23 (92) 42 (89)

† EER based on Schofield equation with PAL 1.55 (Goldberg et al. 1991).

‡ Food and Nutrition Board: Institute of Medicine (IOM : FNB) reference values used for children aged one to three years—CHO: 45–65% energy intake, protein: 5–20% en

30–40% energy intake. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Ma

D.C.: National Academies Press, 2005; 1325.

§ NHRMC reference values used for children aged two to five years—SFA: <10% from energy. National Health and Medical Research Council. Dietary Guidelines for Child

Australia Incorporating the Infant Feeding Guidelines for Healthworkers. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2003.

¶ Assumed 1 L of water is equivalent to 1000 g.

Statistically significant difference compared with the AGHE recommended servings per day: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.0001.

AI, adequate intake; EER, estimated energy requirement; SD, standard deviation; SFA, saturated fatty acids.

L.K. Chai et al.

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia6

Nutrient Reference Values for vitamin A, thiamin, folate, calcium, iron, zinc

Recommended

intakes per day

Mean intakes per day ± SD Proportion meeting recommendations, n (%)

2 years 3 years Combined 2 years 3 years Combined

n = 22 n = 25 n = 47 n = 22 n = 25 n = 47

AGHE FOOD

GROUP

Breads and cereals 4 1.6 ± 0.8*** 2.4 ± 0.8*** 2.0 ± 0.9*** 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0)

Fruit (excluding juice) 1 1.2 ± 0.7 1.5 ± 1.1* 1.4 ± 0.9** 13 (59) 17 (49) 30 (64)

Fruit (including juice) 1 1.5 ± 0.8** 2.0 ± 1.2** 1.8 ± 1.1*** 17 (77) 22 (63) 39 (83)

Vegetables 2.5 1.4 ± 0.7*** 1.3 ± 0.7*** 1.3 ± 0.7*** 2 (9) 1 (3) 3 (6)

Dairy 1.5 2.4 ± 0.8*** 2.1 ± 1.1* 2.2 ± 1.0*** 18 (82) 15 (43) 33 (70)

Meat and alternatives 1 0.7 ± 0.2*** 0.8 ± 0.4** 0.7 ± 0.3*** 2 (8) 8 (23) 10 (21)

Discretionary foods 0–1 2.1 ± 1.1** 3.1 ± 1.6*** 2.6 ± 1.5*** 3 (14) 2 (6) 5 (11)

MACRONUTRIENTS Energy (kJ) EER† 5046 ± 1140 5534 ± 1076 5306 ± 1122 10 (46) 12 (48) 22 (47)

Carbohydrate (%E) 45–65‡ 46.5 ± 4.2 51.3 ± 6.9 49.1 ± 6.2 16 (73) 20 (80) 36 (77)

Protein (%E) 5–20‡ 18.1 ± 1.3 16.8 ± 2.7 17.4 ± 2.3 20 (91) 22 (88) 42 (89)

Total fat (%E) 30–40‡ 34.1 ± 3.9 30.9 ± 5.4 32.4 ± 5.0 18 (82) 14 (56) 32 (68)

SFA (%E) <10§ 17.0 ± 2.6 14.9 ± 3.5 15.9 ± 3.3 22 (100) 25 (100) 47 (100)

Dietary fibre (g) 14 (AI) 13.6 ± 3.7 15.3 ± 4.5 14.5 ± 4.2 9 (41) 16 (64) 25 (53)

Water (g) 1000¶ (AI) 1484.5 ± 385.7 1586.8 ± 413.8 1538.9 ± 399.4 19 (86) 23 (92) 42 (89)

† EER based on Schofield equation with PAL 1.55 (Goldberg et al. 1991).

‡ Food and Nutrition Board: Institute of Medicine (IOM : FNB) reference values used for children aged one to three years—CHO: 45–65% energy intake, protein: 5–20% en

30–40% energy intake. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Ma

D.C.: National Academies Press, 2005; 1325.

§ NHRMC reference values used for children aged two to five years—SFA: <10% from energy. National Health and Medical Research Council. Dietary Guidelines for Child

Australia Incorporating the Infant Feeding Guidelines for Healthworkers. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2003.

¶ Assumed 1 L of water is equivalent to 1000 g.

Statistically significant difference compared with the AGHE recommended servings per day: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.0001.

AI, adequate intake; EER, estimated energy requirement; SD, standard deviation; SFA, saturated fatty acids.

L.K. Chai et al.

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

and poultry, and cereal products. It is possible that children

in this age group are atrisk of excessive zinc intakes.38

However, these findings need to be interpreted with caution

given thatadverse effects secondary to high dietary zinc

intakes have not been reported in Australia.Therefore our

study supports Rangan and Samman’s conclusions that the

currentUL for the two- to three-years age group may be

underestimated and should be reviewed.38

Further analyses were undertaken to assess whether the

eating patterns ofchildren who met the NRVs for vitamin

A, thiamin,folate,calcium,iron and zinc were similar or

differentfrom the eating pattern suggested by the AGHE.

The majority of children in this study met the NRV targets

by followinga patternthat deviatedfrom the age-

appropriaterecommendations.This demonstratedthat

young children could meet the NRVs for selected nutrients

by consuming a significantly greater number of daily serv-

ingsof fruit (excluding juice)and dairy,in combination

with significantly lowermean daily servingsof breads/

cereals,vegetables and meat/alternatives compared to the

AGHE.Implications ofthese findings indicate that model-

ling of food group patterns to inform future refinements of

the AGHE could considerthis approach.Potentially this

would lead to incorporation of even greater diversity in the

distribution of food group servings, within optimal nutrient

intake ranges.

Findings from the presentstudy are similar to those of

nationally representative studies ofAmerican and Belgian

children where a large proportion did notmeetnational

recommendations for food group servings.39,40Sixty percent

and 93% ofAmerican children aged 1–18 years did not

consume the recommended number of servings of fruit and

vegetables,respectively.39 The majority (>50%) ofyounger

Belgian children aged three to seven years did not meet the

recommended number of servings of fruits,vegetables and

dairy products.40

The current study has a few limitations and, in particular,

the small sample size. Hence, results from this study may not

be representative ofother populations and ethnicities and

should be interpreted with caution. The study, although not

population-based,is the firstAustralian study to examine

associations between dietary patterns of children aged two to

three years compared to the revised 2013 AGHE.9 While the

FFQ data were proxy-reported by mothers with a possibility

of reporting bias as parents were unable to observe child

intake at preschoolor day care,the ACAES has been vali-

dated for total energy intake18 in preschool age children and

micronutrient intakes in children above five years.20,21While

FFQs are able to capture usualintake over a longer time

frame,25 and reliable for estimating micronutrient intakes in

infants and preschool children,41 it is acknowledged that the

ACAES has notbeen validated atthe food group level.In

addition, it must be acknowledged that for younger children

the six months reporting period of the FFQ may not accu-

rately reflecttheirusualintake overthattime.A further

limitation is that not all EARs and AIs were considered in the

subsample analysis and hence results should be interpreted

with caution.

In conclusion, the dietary patterns of Australian children

aged two to three in the current study do not align with the

recommended daily servings in the AGHE.Children who

achieved the NRVs for nutrients importantfor health and

development consumed more fruit, dairy and discretionary

servings than current recommendations.Further studies in

larger nationally representative population samples should

be undertaken to evaluate whetherthe currentfindings

apply. Findings from larger cohorts may help to inform the

future modelling of food patterns to incorporate even greater

diversity in the distribution offood group servings while

optimising nutrient intakes.

Funding source

The WATCH study received funding from the University of

Newcastle, the Newcastle Permanent Charitable Foundation

and the John Hunter HospitalCharitable Trust.The study

sponsors were not involved in research design, implementa-

tion or publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authorship

LKC, LMW,AJH, MLB, TLB and CEC contributed to the

methodologicaldesign ofthe study;LKC performed data

analysisand prepared the manuscript.LKC, LMW, TLB,

AJH, MLB,RS and CEC contributed to the revision ofthe

manuscriptand tables.AJH, CEC and RS established the

originalWATCH cohortand MLB contributed to the data

collection. This study was undertaken as a part requirement

for the degreeof Bachelorof Nutrition and Dietetics

(Honours) at the University of Newcastle (LKC),Australia.

All authors contributed to reviewing, editing and approving

the final version of the manuscript.

References

1 Lynch J,Smith GD.A life course approach to chronic disease

epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health 2005; 26: 1–35.

2 Kaikkonen JE, Mikkila V, Magnussen CG, Juonala M, Viikari JS,

Raitakari OT. Does childhood nutrition influence adult cardio-

vascular disease risk?—insights from the Young Finns Study.

Ann Med 2013; 45: 120–28.

3 Jaaskelainen P,Magnussen CG,Pahkala K et al.Childhood

nutrition in predicting metabolic syndrome in adults:the car-

diovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Diabetes Care 2012; 35:

1937–43.

4 Togo P, Osler M, Sorensen T, Heitmann B. Food intake patterns

and body mass index iobservationalstudies.Int J Obes Relat

Metab Disord 2001; 25: 1741–51.

5 HorodynskiMA, StommelM. Nutrition education aimed at

toddlers:an intervention study.Pediatr Nurs 2005;31 (364):

367–72.

6 Birch LL, Doub AE. Learning to eat: birth to age 2 y. Am J Clin

Nutr 2014; 99: 723S–8S.

Children intakes compared to national guidelines

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia 7

in this age group are atrisk of excessive zinc intakes.38

However, these findings need to be interpreted with caution

given thatadverse effects secondary to high dietary zinc

intakes have not been reported in Australia.Therefore our

study supports Rangan and Samman’s conclusions that the

currentUL for the two- to three-years age group may be

underestimated and should be reviewed.38

Further analyses were undertaken to assess whether the

eating patterns ofchildren who met the NRVs for vitamin

A, thiamin,folate,calcium,iron and zinc were similar or

differentfrom the eating pattern suggested by the AGHE.

The majority of children in this study met the NRV targets

by followinga patternthat deviatedfrom the age-

appropriaterecommendations.This demonstratedthat

young children could meet the NRVs for selected nutrients

by consuming a significantly greater number of daily serv-

ingsof fruit (excluding juice)and dairy,in combination

with significantly lowermean daily servingsof breads/

cereals,vegetables and meat/alternatives compared to the

AGHE.Implications ofthese findings indicate that model-

ling of food group patterns to inform future refinements of

the AGHE could considerthis approach.Potentially this

would lead to incorporation of even greater diversity in the

distribution of food group servings, within optimal nutrient

intake ranges.

Findings from the presentstudy are similar to those of

nationally representative studies ofAmerican and Belgian

children where a large proportion did notmeetnational

recommendations for food group servings.39,40Sixty percent

and 93% ofAmerican children aged 1–18 years did not

consume the recommended number of servings of fruit and

vegetables,respectively.39 The majority (>50%) ofyounger

Belgian children aged three to seven years did not meet the

recommended number of servings of fruits,vegetables and

dairy products.40

The current study has a few limitations and, in particular,

the small sample size. Hence, results from this study may not

be representative ofother populations and ethnicities and

should be interpreted with caution. The study, although not

population-based,is the firstAustralian study to examine

associations between dietary patterns of children aged two to

three years compared to the revised 2013 AGHE.9 While the

FFQ data were proxy-reported by mothers with a possibility

of reporting bias as parents were unable to observe child

intake at preschoolor day care,the ACAES has been vali-

dated for total energy intake18 in preschool age children and

micronutrient intakes in children above five years.20,21While

FFQs are able to capture usualintake over a longer time

frame,25 and reliable for estimating micronutrient intakes in

infants and preschool children,41 it is acknowledged that the

ACAES has notbeen validated atthe food group level.In

addition, it must be acknowledged that for younger children

the six months reporting period of the FFQ may not accu-

rately reflecttheirusualintake overthattime.A further

limitation is that not all EARs and AIs were considered in the

subsample analysis and hence results should be interpreted

with caution.

In conclusion, the dietary patterns of Australian children

aged two to three in the current study do not align with the

recommended daily servings in the AGHE.Children who

achieved the NRVs for nutrients importantfor health and

development consumed more fruit, dairy and discretionary

servings than current recommendations.Further studies in

larger nationally representative population samples should

be undertaken to evaluate whetherthe currentfindings

apply. Findings from larger cohorts may help to inform the

future modelling of food patterns to incorporate even greater

diversity in the distribution offood group servings while

optimising nutrient intakes.

Funding source

The WATCH study received funding from the University of

Newcastle, the Newcastle Permanent Charitable Foundation

and the John Hunter HospitalCharitable Trust.The study

sponsors were not involved in research design, implementa-

tion or publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authorship

LKC, LMW,AJH, MLB, TLB and CEC contributed to the

methodologicaldesign ofthe study;LKC performed data

analysisand prepared the manuscript.LKC, LMW, TLB,

AJH, MLB,RS and CEC contributed to the revision ofthe

manuscriptand tables.AJH, CEC and RS established the

originalWATCH cohortand MLB contributed to the data

collection. This study was undertaken as a part requirement

for the degreeof Bachelorof Nutrition and Dietetics

(Honours) at the University of Newcastle (LKC),Australia.

All authors contributed to reviewing, editing and approving

the final version of the manuscript.

References

1 Lynch J,Smith GD.A life course approach to chronic disease

epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health 2005; 26: 1–35.

2 Kaikkonen JE, Mikkila V, Magnussen CG, Juonala M, Viikari JS,

Raitakari OT. Does childhood nutrition influence adult cardio-

vascular disease risk?—insights from the Young Finns Study.

Ann Med 2013; 45: 120–28.

3 Jaaskelainen P,Magnussen CG,Pahkala K et al.Childhood

nutrition in predicting metabolic syndrome in adults:the car-

diovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Diabetes Care 2012; 35:

1937–43.

4 Togo P, Osler M, Sorensen T, Heitmann B. Food intake patterns

and body mass index iobservationalstudies.Int J Obes Relat

Metab Disord 2001; 25: 1741–51.

5 HorodynskiMA, StommelM. Nutrition education aimed at

toddlers:an intervention study.Pediatr Nurs 2005;31 (364):

367–72.

6 Birch LL, Doub AE. Learning to eat: birth to age 2 y. Am J Clin

Nutr 2014; 99: 723S–8S.

Children intakes compared to national guidelines

© 2015 Dietitians Association of Australia 7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7 Queensland Health. A Healthy Start in Life:A Nutrition Manual

for Health Professionals. Brisbane: Queensland Health, 2008.

8 Queensland Public Health Forum.EatWellQueensland 2002–

2012:Smart Eating for a Healthier State.Brisbane:Queensland

Public Health Forum, 2002.

9 NationalHealth and MedicalResearch Council.Eat for Health

Australian Dietary GuidelinesSummary.Canberra:Common-

wealth of Australia, 2013. (Available from: http://

www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/

n55a_australian_dietary_guidelines_summary_131014.pdf,

accessed 2 June 2015).

10 Cashel K, Jeffreson S. The Core Food Groups: The Scientific Basis

for DevelopingNutrition Education Tools.Canberra:National

Health and Medical Research Council, 1994.

11 NationalHealth and MedicalResearch Council.A Modelling

System to Inform the Revision ofthe Australian Guide to Healthy

Eating. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2011. (Available

from: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/

public_consultation/n55a_dietary_guidelines_food_modelling

_111216.pdf, accessed 20 January 2015).

12 National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient Refer-

ence Values for Australia and New Zealand Including Recommended

Dietary Intakes.Canberra:NHMRC;, 2006.(Available from:

https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients-energy-calculation/nutrients

-energy-calc-result-1421754458, accessed 20 January 2015).

13 Kellett E, Smith A, Schmerlaib Y. The Australian Guide to Healthy

Eating—Background Information for Consumers.Canberra:Aus-

tralian GovernmentDepartmentof Health and Ageing,1998.

(Availablefrom: http://www.fairfieldcity.nsw.gov.au/upload/

pkmhl46337/AustGuidetoHealtyEating.pdf,accessed 20

January 2015).

14 Maclennan W,PodgerA. NationalNutrition Survey Nutrient

Intakesand PhysicalMeasurement1995.Canberra:Australian

Bureau of Statistics, 1998. (Available from: http://www.abs.gov

.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/95E87FE64B144FA3CA2568A9

001393C0, accessed 10 November 2014).

15 Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. 2007

Australian NationalChildren’sNutrition and PhysicalActivity

Survey Main Findings.Canberra:Commonwealth ofAustralia,

2008. (Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/

publishing.nsf/Content/8F4516D5FAC0700ACA257BF0001E0

109/$File/childrens-nut-phys-survey.pdf,accessed 20 January

2015).

16 Webb K, Rutishauser I, Knezevic N. Foods, nutrients and por-

tions consumed by a sample of Australian children aged 16–24

months. Nutr Diet 2008; 65: 56–65.

17 AIHW. 2010 Australian National Infant Feeding Survey: Indicator

Results.Canberra:AIHW, 2011.(Available from:http://www

.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=10737420927,accessed 10

November 2014).