Investigation of the complementary and alternative medicine’s benefits in cancer pain management: A comparative study between cannabis and morphine

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/19

|51

|12010

|89

AI Summary

This research investigation aims to evaluate and explore the effect of traditional and alternative medicine such as Cannabis and Morphine in pain management of cancer patients.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Running head: DISSERTATION

DISSERTATION ON EVIDENCE BASED NURSING

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Submission Date:

Word Count:

DISSERTATION ON EVIDENCE BASED NURSING

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Submission Date:

Word Count:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1DISSERTATION

Investigation of the complementary and alternative medicine’s benefits

in cancer pain management: A comparative study between cannabis and

morphine.

Investigation of the complementary and alternative medicine’s benefits

in cancer pain management: A comparative study between cannabis and

morphine.

2DISSERTATION

Abstract

Background: Morphine has been one of the frequently used opioids to treat serious cancer

injuries. In this regard, cancer is an acute and chronic disease sufficient to cause immense

suffering for the person, and also to reduce the willingness to live longer. Thus, morphine, a

chain opiate painkiller, is amongst the most commonly used analgesics for pain. The absence of

clinical evidence on cannabis used as medicinal purpose for the treatment of cancer pain is still

inconclusive which limited its investigation as a potential medical product because of its lack

of classification as an agent for schedule I by the Controlled Substances Act of 1970.

Aim: This research investigation aim was to evaluate and explore the effect of traditional and

alternative medicine such as Cannabis and Morphine in pain management of cancer patient.

Research question: Research questions for this investigation was “Does Morphine or Cannabis

improve the pain management among the patients living with cancer?”

Design: Rapid Evidence Assessment was used as a study design for this investigation.

Method: Electronic searches have been conducted in two databases with key words for this

investigation. Identified research publication were selected for relevancy according to the

inclusion criterion adopted or this study, evaluated for quality, and relevant data and the analysis

were conducted on the extracted data.

Ethical consideration: No primary research has been conducted for this research and only

secondary research has been conducted for this study. Therefore, no ethical consideration was

required for this study.

Abstract

Background: Morphine has been one of the frequently used opioids to treat serious cancer

injuries. In this regard, cancer is an acute and chronic disease sufficient to cause immense

suffering for the person, and also to reduce the willingness to live longer. Thus, morphine, a

chain opiate painkiller, is amongst the most commonly used analgesics for pain. The absence of

clinical evidence on cannabis used as medicinal purpose for the treatment of cancer pain is still

inconclusive which limited its investigation as a potential medical product because of its lack

of classification as an agent for schedule I by the Controlled Substances Act of 1970.

Aim: This research investigation aim was to evaluate and explore the effect of traditional and

alternative medicine such as Cannabis and Morphine in pain management of cancer patient.

Research question: Research questions for this investigation was “Does Morphine or Cannabis

improve the pain management among the patients living with cancer?”

Design: Rapid Evidence Assessment was used as a study design for this investigation.

Method: Electronic searches have been conducted in two databases with key words for this

investigation. Identified research publication were selected for relevancy according to the

inclusion criterion adopted or this study, evaluated for quality, and relevant data and the analysis

were conducted on the extracted data.

Ethical consideration: No primary research has been conducted for this research and only

secondary research has been conducted for this study. Therefore, no ethical consideration was

required for this study.

3DISSERTATION

Results: In total six recent researches journal was used to evaluate the research question

presented in this study. Three of them related to morphine and three of them are related to the

Cannabis. In the data extraction process, it has been found out that both cannabis and morphine

can be used to treat pain among the patients suffering from cancer.

Conclusion: In a nutshell, it can be stated that the both methods used for the treatment of the pain

among cancer patients can be compared. However, the significant difference among them is that

morphine has more adverse effect when used as a first line treatment. Nonetheless, further

studies are required for the standardisation and regulatory administration of morphine and

cannabis as treatment for cancer pain.

Results: In total six recent researches journal was used to evaluate the research question

presented in this study. Three of them related to morphine and three of them are related to the

Cannabis. In the data extraction process, it has been found out that both cannabis and morphine

can be used to treat pain among the patients suffering from cancer.

Conclusion: In a nutshell, it can be stated that the both methods used for the treatment of the pain

among cancer patients can be compared. However, the significant difference among them is that

morphine has more adverse effect when used as a first line treatment. Nonetheless, further

studies are required for the standardisation and regulatory administration of morphine and

cannabis as treatment for cancer pain.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

4DISSERTATION

Glossary of Acronyms

CBD :Cannabidiol

REA : Rapid Evidence Assessment

THC : Tetrahydrocannabinol

PICO : Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

ECLIPSE : Expectation, Client group, Location, Impact, Professionals, Service

CIMO : Context, Intervention, Mechanism, Outcome

RCT : Randomised Controlled Trial

QOL : Quality of Life

Glossary of Acronyms

CBD :Cannabidiol

REA : Rapid Evidence Assessment

THC : Tetrahydrocannabinol

PICO : Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

ECLIPSE : Expectation, Client group, Location, Impact, Professionals, Service

CIMO : Context, Intervention, Mechanism, Outcome

RCT : Randomised Controlled Trial

QOL : Quality of Life

5DISSERTATION

Table of Contents

1. Introduction..................................................................................................................................8

1.1 Rationale behind the research investigation..........................................................................8

1.2 Introduction to Cannabis for pain management in cancer.....................................................9

1.3 Introduction to Morphine for pain management in cancer..................................................10

1.4 Aim and objectives..............................................................................................................11

1.5 Study design.........................................................................................................................12

1.6 Ethical consideration...........................................................................................................13

2. Methods.....................................................................................................................................14

2.1 Research question................................................................................................................14

2.2 Search strategy.....................................................................................................................15

2.3 Rationale behind the search terms.......................................................................................17

2.4 Article Selection..................................................................................................................19

2.5 Inclusion and exclusion criteria...........................................................................................19

2.6 Data synthesis and extraction..............................................................................................20

2.7 Quality appraisal..................................................................................................................22

Table of Contents

1. Introduction..................................................................................................................................8

1.1 Rationale behind the research investigation..........................................................................8

1.2 Introduction to Cannabis for pain management in cancer.....................................................9

1.3 Introduction to Morphine for pain management in cancer..................................................10

1.4 Aim and objectives..............................................................................................................11

1.5 Study design.........................................................................................................................12

1.6 Ethical consideration...........................................................................................................13

2. Methods.....................................................................................................................................14

2.1 Research question................................................................................................................14

2.2 Search strategy.....................................................................................................................15

2.3 Rationale behind the search terms.......................................................................................17

2.4 Article Selection..................................................................................................................19

2.5 Inclusion and exclusion criteria...........................................................................................19

2.6 Data synthesis and extraction..............................................................................................20

2.7 Quality appraisal..................................................................................................................22

6DISSERTATION

3. Results........................................................................................................................................24

3.1 Summary of the included studies.........................................................................................24

3.2 Summary of the excluded studies and rationale behind exclusion......................................24

3.3 Description of the study findings.........................................................................................24

3.3.1 Bandieri et al. 2016.......................................................................................................24

3.3.2 Riley et al. 2015............................................................................................................25

3.3.3Nunes, Garcia and Sakata 2014.....................................................................................27

3.3.4Khaiser et al. 2016.........................................................................................................28

3.3.5 Abrams 2016.................................................................................................................30

3.3.6 Shaw et al. 2017............................................................................................................31

4. Discussion..................................................................................................................................33

4.1 Discussion on morphine as a pain management among cancer patients.............................33

4.2 Discussion on Cannabis as a pain management among cancer patients..............................35

5. Conclusion.................................................................................................................................38

5.1 Summary..............................................................................................................................38

5.2 Limitations...........................................................................................................................39

5.3 Recommendations................................................................................................................39

3. Results........................................................................................................................................24

3.1 Summary of the included studies.........................................................................................24

3.2 Summary of the excluded studies and rationale behind exclusion......................................24

3.3 Description of the study findings.........................................................................................24

3.3.1 Bandieri et al. 2016.......................................................................................................24

3.3.2 Riley et al. 2015............................................................................................................25

3.3.3Nunes, Garcia and Sakata 2014.....................................................................................27

3.3.4Khaiser et al. 2016.........................................................................................................28

3.3.5 Abrams 2016.................................................................................................................30

3.3.6 Shaw et al. 2017............................................................................................................31

4. Discussion..................................................................................................................................33

4.1 Discussion on morphine as a pain management among cancer patients.............................33

4.2 Discussion on Cannabis as a pain management among cancer patients..............................35

5. Conclusion.................................................................................................................................38

5.1 Summary..............................................................................................................................38

5.2 Limitations...........................................................................................................................39

5.3 Recommendations................................................................................................................39

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7DISSERTATION

6. References..................................................................................................................................41

7. Appendices................................................................................................................................47

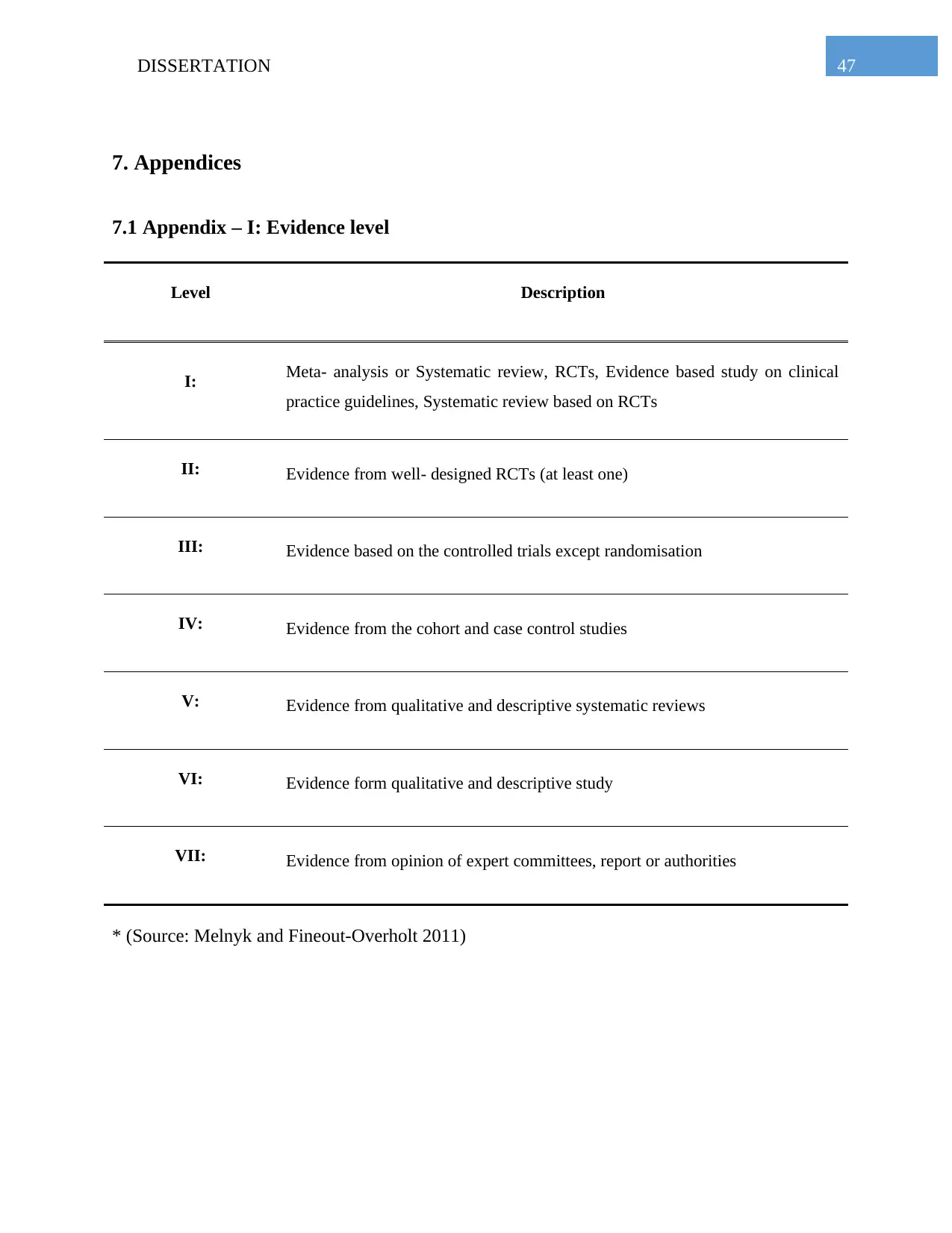

7.1 Appendix – I: Evidence level..............................................................................................47

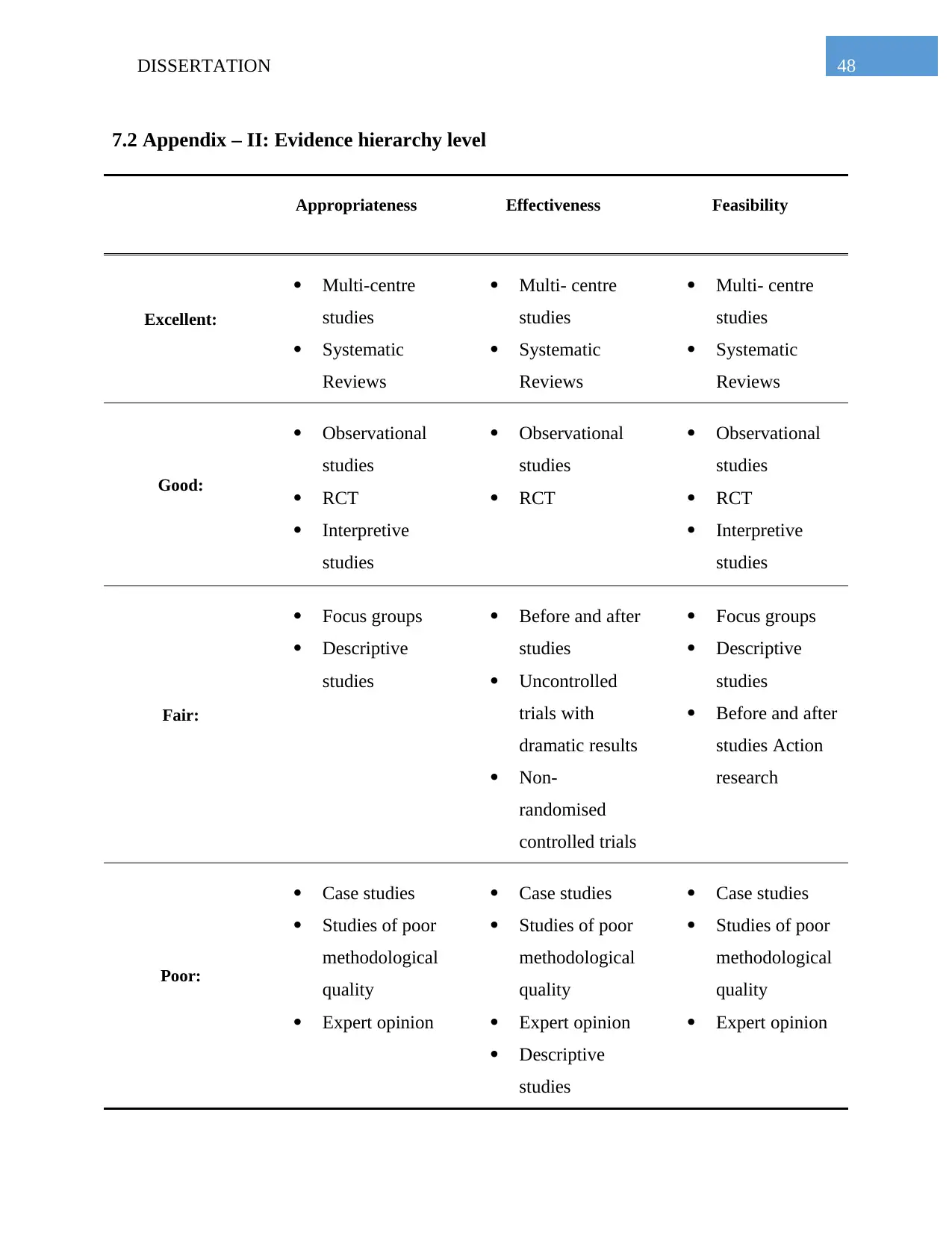

7.2 Appendix – II: Evidence hierarchy level.............................................................................48

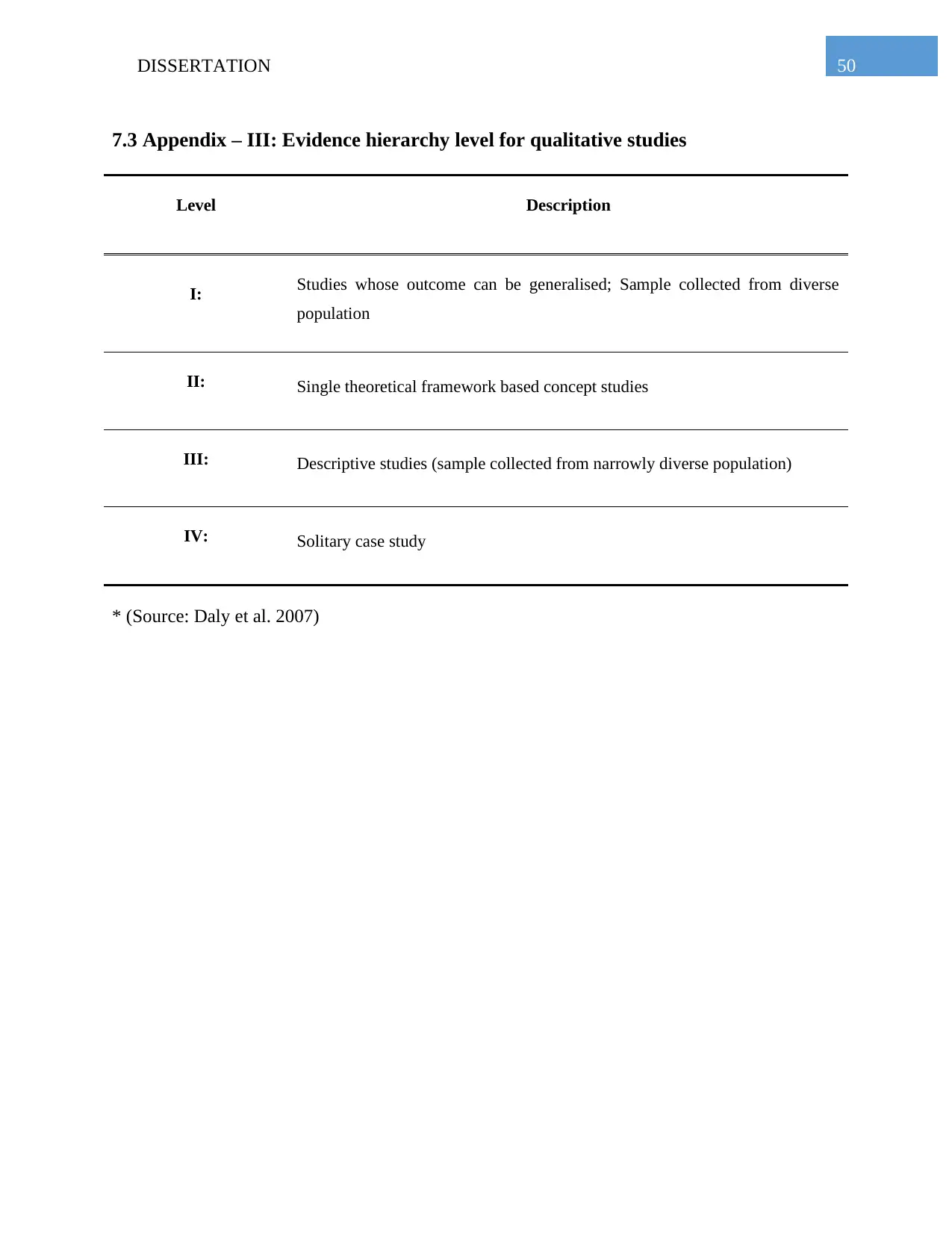

7.3 Appendix – III: Evidence hierarchy level for qualitative studies........................................49

6. References..................................................................................................................................41

7. Appendices................................................................................................................................47

7.1 Appendix – I: Evidence level..............................................................................................47

7.2 Appendix – II: Evidence hierarchy level.............................................................................48

7.3 Appendix – III: Evidence hierarchy level for qualitative studies........................................49

8DISSERTATION

Chapter 1

1. Introduction

1.1 Rationale behind the research investigation

The adverse impacts of morphine or any opioid derived drugs have been studied several times

over but no sufficient attempts have been made to create alternative medications to substitute the

widely used opioid- based pain relievers even though various adverse impacts of long-term use

are present (Wiffen, Wee and Moore 2016). Morphine, though, has been one of the frequently

used opioids to treat serious cancer injuries. In this regard, cancer is an acute and chronic disease

sufficient to cause immense suffering for the person, and also to reduce the willingness to live

longer. Thus, morphine, a chain opiate painkiller, is amongst the most commonly used analgesics

for pain (Money and Garber 2018). However opioid-based treatment such as the morphine, as

described by Bandieri et al. (2015), is still very tentative and with many discretions used in

clinical exercise, even in the palliative medication field, despite its effectively and efficiently

reducing even severe suffering such as cancer-related suffering. As Wiffen et al. (2017) have

mentioned, the use of morphine can be viewed as a balance act, and many writers and clinics

have even taken into account the use of moral suffering as a compensation between pain relief

and negative impacts (Mercadante et al. 2016). Recent study uses morphine as a synonym for or

marker of imminent mortality and cancer suffering is also a benchmark for a deep existential

illness. In addition, the morphine mode of action is mediated by a receptor binding process,

particularly the CNS Opioid cells. As Mercadante et al. (2015) discusses, morphine mainly

operates on mu- opioid receptors by catalysing a sequence of responses that in turn alter the

Chapter 1

1. Introduction

1.1 Rationale behind the research investigation

The adverse impacts of morphine or any opioid derived drugs have been studied several times

over but no sufficient attempts have been made to create alternative medications to substitute the

widely used opioid- based pain relievers even though various adverse impacts of long-term use

are present (Wiffen, Wee and Moore 2016). Morphine, though, has been one of the frequently

used opioids to treat serious cancer injuries. In this regard, cancer is an acute and chronic disease

sufficient to cause immense suffering for the person, and also to reduce the willingness to live

longer. Thus, morphine, a chain opiate painkiller, is amongst the most commonly used analgesics

for pain (Money and Garber 2018). However opioid-based treatment such as the morphine, as

described by Bandieri et al. (2015), is still very tentative and with many discretions used in

clinical exercise, even in the palliative medication field, despite its effectively and efficiently

reducing even severe suffering such as cancer-related suffering. As Wiffen et al. (2017) have

mentioned, the use of morphine can be viewed as a balance act, and many writers and clinics

have even taken into account the use of moral suffering as a compensation between pain relief

and negative impacts (Mercadante et al. 2016). Recent study uses morphine as a synonym for or

marker of imminent mortality and cancer suffering is also a benchmark for a deep existential

illness. In addition, the morphine mode of action is mediated by a receptor binding process,

particularly the CNS Opioid cells. As Mercadante et al. (2015) discusses, morphine mainly

operates on mu- opioid receptors by catalysing a sequence of responses that in turn alter the

9DISSERTATION

regulation of pain response in the human body. Morphine is undoubtedly an amazing treatment

of pain and, but at the other side, it is also has a highly significant list of secondary impacts. The

danger of dependency and withdrawal is particularly strong for patients who receive morphine.

Furthermore, the administration of morphine has several other side impacts for a lengthy moment

(Abrams 2016). These adverse implications include severe nausea, constipation, dullness,

severe dry throat, headache, mood depression, sudden and uncontrollable bodily wobbles, loss of

gender or libido, localized discomfort, particularly in the abdomen, insomnia, drowsiness, and

excessive tiredness in multiple areas of the body, lack of appetites, swelling of both arm and

ultimate bodily limbs (Bandieri et al. 2016). The use of an alternative option that can be given by

marijuana can therefore be a very important answer to the upcoming opioid outbreak. The

patients can create an opiates’ tolerance which requires an increasing amount of the drug to

obtain the required effects (Abrams and Guzman 2015). In an elaborate sense, Cannabis is an

ancient natural plant compound claimed to have a variety of medicinal characteristics. One of the

countless health advantages is managing acute pain sensations Cannabis, if efficiently applied,

can surpass morphine while being secure and non-toxic. This research aims to strengthen and

evaluate current proof on this subject using the organizational form of the systematic evaluation

and to solve the query whether marijuana and morphine are leading to better clinical pain

leadership, particularly for cancer- related injuries (Garud et al. 2017).

1.2 Introduction to Cannabis for pain management in cancer

The absence of clinical evidence on cannabis used as medical remedy for the treatment of cancer

pain is still inconclusive which limited its examination as a potential medical product because of

its lack of classification as an agent for schedule I by the Controlled Substances Act of 1970

(Borgelt et al. 2013). Nevertheless, several surveys generated on the treatment of cancer

regulation of pain response in the human body. Morphine is undoubtedly an amazing treatment

of pain and, but at the other side, it is also has a highly significant list of secondary impacts. The

danger of dependency and withdrawal is particularly strong for patients who receive morphine.

Furthermore, the administration of morphine has several other side impacts for a lengthy moment

(Abrams 2016). These adverse implications include severe nausea, constipation, dullness,

severe dry throat, headache, mood depression, sudden and uncontrollable bodily wobbles, loss of

gender or libido, localized discomfort, particularly in the abdomen, insomnia, drowsiness, and

excessive tiredness in multiple areas of the body, lack of appetites, swelling of both arm and

ultimate bodily limbs (Bandieri et al. 2016). The use of an alternative option that can be given by

marijuana can therefore be a very important answer to the upcoming opioid outbreak. The

patients can create an opiates’ tolerance which requires an increasing amount of the drug to

obtain the required effects (Abrams and Guzman 2015). In an elaborate sense, Cannabis is an

ancient natural plant compound claimed to have a variety of medicinal characteristics. One of the

countless health advantages is managing acute pain sensations Cannabis, if efficiently applied,

can surpass morphine while being secure and non-toxic. This research aims to strengthen and

evaluate current proof on this subject using the organizational form of the systematic evaluation

and to solve the query whether marijuana and morphine are leading to better clinical pain

leadership, particularly for cancer- related injuries (Garud et al. 2017).

1.2 Introduction to Cannabis for pain management in cancer

The absence of clinical evidence on cannabis used as medical remedy for the treatment of cancer

pain is still inconclusive which limited its examination as a potential medical product because of

its lack of classification as an agent for schedule I by the Controlled Substances Act of 1970

(Borgelt et al. 2013). Nevertheless, several surveys generated on the treatment of cancer

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

10DISSERTATION

suffering with medical marijuana indicate that they have beneficial capacity and at least need

further research. There are no dosing rules in clinical exercise for the use of therapies based on

cannabinoid usage. The perfect dose would allow an efficient treatment of pain but does not

generate unbearable side impacts. Moreover, it is difficult for the complicated cancer patient

populations to achieve this ideal dose (Blake et al. 2017). One of those is the person to person

variation according to the outcomes of the drugs and other pharmaceuticals intervention. Since

the appropriate dose has been observed to differ from patient to patient, doctors need to know

how the right dosage is determined when a fresh patient is prescribed. Advanced patients with

disease are also expected to show complicated symptoms, which render it hard, and often take

several concomitant medicines, to precisely evaluate the side impacts of marijuana medicines

(Blake et al. 2017).However, a multitude of such studies have noted that detected side effects

appear to not be limiting the therapy and that dose titration may be controlled by pain relief in a

low dosage of 2.7 to 10.8 milligrams THC combined with 2.5–10.0 milligrams CBD. This shows

the need to establish and validate a titration protocol to enable scientists to safely and effectively

define efficient and tolerated dosages (Lynch, Cesar - Rittenberg and Hohmann 2014).

1.3 Introduction to Morphine for pain management in cancer

After the World Health organization's (WHO) instructions were published in the mid-1980s,

treatment of mild to serious cancer suffering became common every four hours of daily

administration of aqueous morphine remedy (Wiffen, Wee and Moore 2016). Morphine was

initially commercialised at around the same moment in a release tablet form to extend the dosage

period to 12 hours. Both 12 hour and 24 hour discharge tablets are accessible and should be

swallowed in their entirety (Wiffen, Wee and Moore 2016). Modified release tablets contain

covered tiny beads and, if needed, may be sprinkled with food. Most trials contrasted oral dosing

suffering with medical marijuana indicate that they have beneficial capacity and at least need

further research. There are no dosing rules in clinical exercise for the use of therapies based on

cannabinoid usage. The perfect dose would allow an efficient treatment of pain but does not

generate unbearable side impacts. Moreover, it is difficult for the complicated cancer patient

populations to achieve this ideal dose (Blake et al. 2017). One of those is the person to person

variation according to the outcomes of the drugs and other pharmaceuticals intervention. Since

the appropriate dose has been observed to differ from patient to patient, doctors need to know

how the right dosage is determined when a fresh patient is prescribed. Advanced patients with

disease are also expected to show complicated symptoms, which render it hard, and often take

several concomitant medicines, to precisely evaluate the side impacts of marijuana medicines

(Blake et al. 2017).However, a multitude of such studies have noted that detected side effects

appear to not be limiting the therapy and that dose titration may be controlled by pain relief in a

low dosage of 2.7 to 10.8 milligrams THC combined with 2.5–10.0 milligrams CBD. This shows

the need to establish and validate a titration protocol to enable scientists to safely and effectively

define efficient and tolerated dosages (Lynch, Cesar - Rittenberg and Hohmann 2014).

1.3 Introduction to Morphine for pain management in cancer

After the World Health organization's (WHO) instructions were published in the mid-1980s,

treatment of mild to serious cancer suffering became common every four hours of daily

administration of aqueous morphine remedy (Wiffen, Wee and Moore 2016). Morphine was

initially commercialised at around the same moment in a release tablet form to extend the dosage

period to 12 hours. Both 12 hour and 24 hour discharge tablets are accessible and should be

swallowed in their entirety (Wiffen, Wee and Moore 2016). Modified release tablets contain

covered tiny beads and, if needed, may be sprinkled with food. Most trials contrasted oral dosing

11DISSERTATION

of morphine or oral morphine formulations with other oral opioids on separate paths of

administration on occasion. For any specific comparative there was no collection of proof.

Evidence should have been still helpful if continuously reported results were that a patient

reported result of recognized benefits was obtained with respondents receiving excellent pain

relief ideally not worse than moderate pain. A particular focus on research that attempted to

identify tiny effective distinctions or harms between formulas, opioids or both has also hindered

the application of the proof (Wiffen, Wee and Moore 2016).

1.4 Aim and objectives

Aim and objectives are two most vital part of a research investigation and it is a very integral

part of the research topic. Therefore, the aim and objectives of a research topic should be

designed and developed in a concise and clear manner, so that it can effectively and concisely

convey the message and objectives of the research topic. Academics have suggested that the

aims and objective should clearly state the purpose of the whole project, the clear reason it is

being conducted for, outline and overall structure of the project and expected outcome of the

project (Booth, Sutton and Papaioannou 2016). Therefore, during the development of this

project’s aim and objective, the above criteria of the aims and objectives were considered. The

aim and objective of this investigation project is mentioned below:

Aim: This research investigation’s aim was evaluate and explore the effect of traditional and

alternative medicine such as Cannabis and Morphine in pain management of cancer patient.

Objectives:

Analysis and identification of current research publication on the use and efficacy of

of morphine or oral morphine formulations with other oral opioids on separate paths of

administration on occasion. For any specific comparative there was no collection of proof.

Evidence should have been still helpful if continuously reported results were that a patient

reported result of recognized benefits was obtained with respondents receiving excellent pain

relief ideally not worse than moderate pain. A particular focus on research that attempted to

identify tiny effective distinctions or harms between formulas, opioids or both has also hindered

the application of the proof (Wiffen, Wee and Moore 2016).

1.4 Aim and objectives

Aim and objectives are two most vital part of a research investigation and it is a very integral

part of the research topic. Therefore, the aim and objectives of a research topic should be

designed and developed in a concise and clear manner, so that it can effectively and concisely

convey the message and objectives of the research topic. Academics have suggested that the

aims and objective should clearly state the purpose of the whole project, the clear reason it is

being conducted for, outline and overall structure of the project and expected outcome of the

project (Booth, Sutton and Papaioannou 2016). Therefore, during the development of this

project’s aim and objective, the above criteria of the aims and objectives were considered. The

aim and objective of this investigation project is mentioned below:

Aim: This research investigation’s aim was evaluate and explore the effect of traditional and

alternative medicine such as Cannabis and Morphine in pain management of cancer patient.

Objectives:

Analysis and identification of current research publication on the use and efficacy of

12DISSERTATION

alternative and traditional method like Cannabis and Morphine in pain management.

Evaluation and exploration of current research publication on the efficacy of Cannabis as

pain management among cancer patient.

Evaluation and exploration of current research publication on the efficacy of Morphine as

pain management among cancer patient.

Report and identification of relevant data whether these pain management techniques

effectively applied in clinical settings.

1.5 Study design

REA or Rapid evidence assessment is an effective tool for analysing and evaluating existing

research among a limited time frame. It is allows the investigator of the research to provide a

critical evidence based overview on the research topic as well as to find a research gap among

the existing research publication (Haby et al. 2016). In addition to that, REA also allows the

investigator to find, appraise, gather and summarize data on a particular research topic and it can

be done on the within a short time frame like 2 – 3 months. This application and implementation

of evidence based method is particularly effective in the area of the health care practice (Haby et

al. 2016). From the above discussion, it can be stated that the REA can be used effectively to

gather, analyse, and explore high quality research publication within short frame which very

much in line with the timeframe of this investigation. Therefore, REA will be used as a study

design for this research investigation.

However, there are some limits for the Rapid Evidence Assessment study design. The assurance

of the outcomes of this study design can be lower due to the publication bias (Ganann, Ciliska

and Thomas2010). Owing to the short time frame of this study design, it is less demanding than a

alternative and traditional method like Cannabis and Morphine in pain management.

Evaluation and exploration of current research publication on the efficacy of Cannabis as

pain management among cancer patient.

Evaluation and exploration of current research publication on the efficacy of Morphine as

pain management among cancer patient.

Report and identification of relevant data whether these pain management techniques

effectively applied in clinical settings.

1.5 Study design

REA or Rapid evidence assessment is an effective tool for analysing and evaluating existing

research among a limited time frame. It is allows the investigator of the research to provide a

critical evidence based overview on the research topic as well as to find a research gap among

the existing research publication (Haby et al. 2016). In addition to that, REA also allows the

investigator to find, appraise, gather and summarize data on a particular research topic and it can

be done on the within a short time frame like 2 – 3 months. This application and implementation

of evidence based method is particularly effective in the area of the health care practice (Haby et

al. 2016). From the above discussion, it can be stated that the REA can be used effectively to

gather, analyse, and explore high quality research publication within short frame which very

much in line with the timeframe of this investigation. Therefore, REA will be used as a study

design for this research investigation.

However, there are some limits for the Rapid Evidence Assessment study design. The assurance

of the outcomes of this study design can be lower due to the publication bias (Ganann, Ciliska

and Thomas2010). Owing to the short time frame of this study design, it is less demanding than a

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

13DISSERTATION

systematic review and it omits the area of dissertation and unpublished research. However, if

strict exclusion and inclusion criteria can be implemented to the REA study design to make it

less prone to publication bias (Ganann, Ciliska and Thomas2010).

1.6 Ethical consideration

The study design of this assignment is REA and no primary research has been conducted for this

research. Only secondary research has been conducted for this study. Therefore, no ethical

consideration was exclusively required for this study.

systematic review and it omits the area of dissertation and unpublished research. However, if

strict exclusion and inclusion criteria can be implemented to the REA study design to make it

less prone to publication bias (Ganann, Ciliska and Thomas2010).

1.6 Ethical consideration

The study design of this assignment is REA and no primary research has been conducted for this

research. Only secondary research has been conducted for this study. Therefore, no ethical

consideration was exclusively required for this study.

14DISSERTATION

Chapter 2

2. Methods

2.1 Research question

In all scientific studies, it is highly important to implement a focused question model. In this

sense, the significance of a focused study issue must be recognized as ideal in simplifying and

clarifying the precise subject on which the study will be based. A focused research issue enables

scientists to advance a research study in a well guided manner and enables them explore and deal

with the precise and particular fields of interest in the subject in an ideal way (Peters et al. 2015).

Different designs are accessible for study questions. Other design includes Context, Intervention,

Mechanism, Outcome (CIMO) model (Wong et al. 2013), and the Expectation, Client group,

Location, Impact, Professionals, Service (ECLIPSE) framework (Wildridge and Bell 2002).

PICO is a well-developed medical study structure (Davies 2011) that could assist to formulate a

clearly specified and restricted query that can be used to guide the REA method. The PICO

structure has, however, been established to assist scientists respond to and adapt the layout of

this REA to health-related issues (Davies 2011).

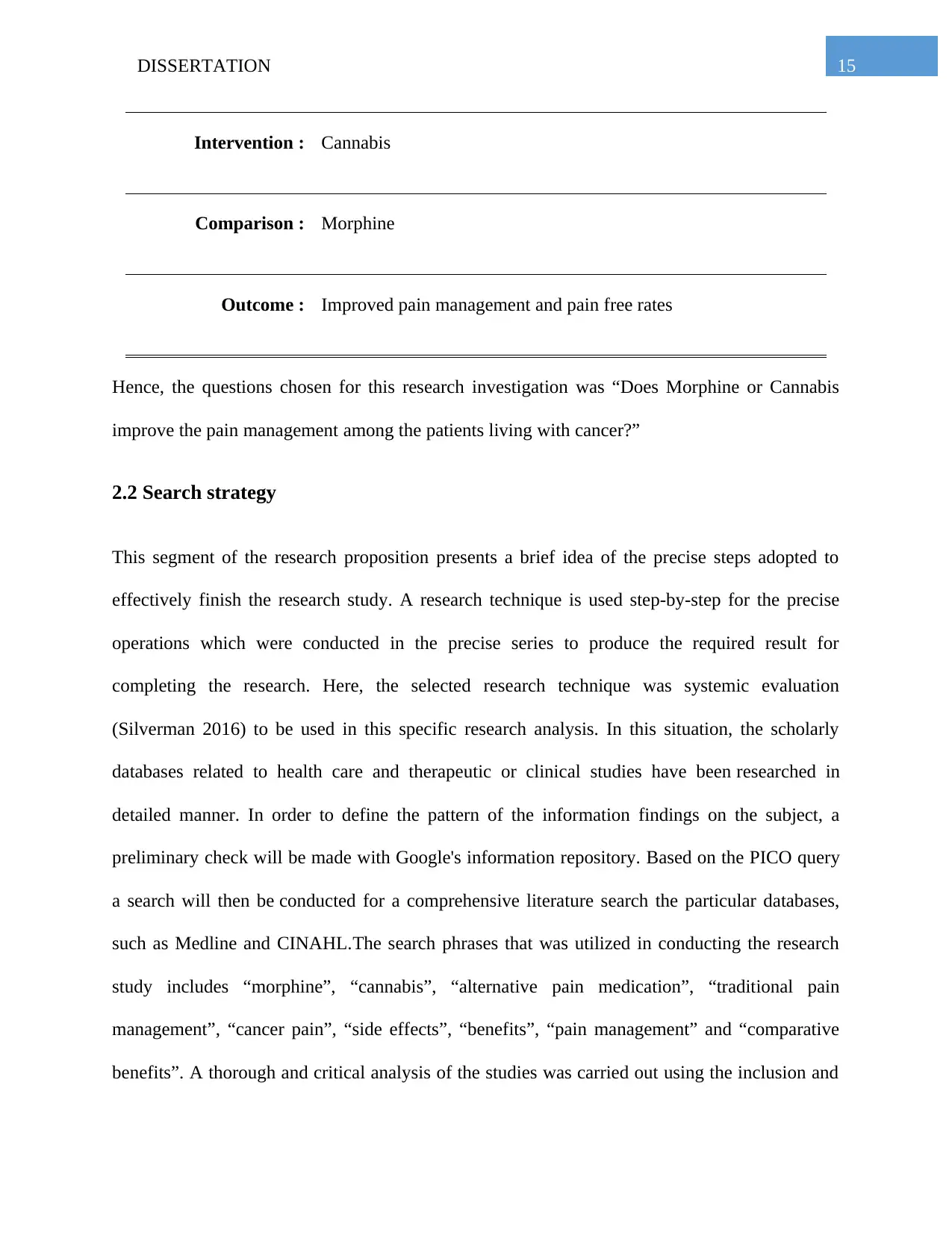

PICO question for this research is presented in the Table 1 below.

Table 1: PICO Questions

Population : Patients living with cancer

Chapter 2

2. Methods

2.1 Research question

In all scientific studies, it is highly important to implement a focused question model. In this

sense, the significance of a focused study issue must be recognized as ideal in simplifying and

clarifying the precise subject on which the study will be based. A focused research issue enables

scientists to advance a research study in a well guided manner and enables them explore and deal

with the precise and particular fields of interest in the subject in an ideal way (Peters et al. 2015).

Different designs are accessible for study questions. Other design includes Context, Intervention,

Mechanism, Outcome (CIMO) model (Wong et al. 2013), and the Expectation, Client group,

Location, Impact, Professionals, Service (ECLIPSE) framework (Wildridge and Bell 2002).

PICO is a well-developed medical study structure (Davies 2011) that could assist to formulate a

clearly specified and restricted query that can be used to guide the REA method. The PICO

structure has, however, been established to assist scientists respond to and adapt the layout of

this REA to health-related issues (Davies 2011).

PICO question for this research is presented in the Table 1 below.

Table 1: PICO Questions

Population : Patients living with cancer

15DISSERTATION

Intervention : Cannabis

Comparison : Morphine

Outcome : Improved pain management and pain free rates

Hence, the questions chosen for this research investigation was “Does Morphine or Cannabis

improve the pain management among the patients living with cancer?”

2.2 Search strategy

This segment of the research proposition presents a brief idea of the precise steps adopted to

effectively finish the research study. A research technique is used step-by-step for the precise

operations which were conducted in the precise series to produce the required result for

completing the research. Here, the selected research technique was systemic evaluation

(Silverman 2016) to be used in this specific research analysis. In this situation, the scholarly

databases related to health care and therapeutic or clinical studies have been researched in

detailed manner. In order to define the pattern of the information findings on the subject, a

preliminary check will be made with Google's information repository. Based on the PICO query

a search will then be conducted for a comprehensive literature search the particular databases,

such as Medline and CINAHL.The search phrases that was utilized in conducting the research

study includes “morphine”, “cannabis”, “alternative pain medication”, “traditional pain

management”, “cancer pain”, “side effects”, “benefits”, “pain management” and “comparative

benefits”. A thorough and critical analysis of the studies was carried out using the inclusion and

Intervention : Cannabis

Comparison : Morphine

Outcome : Improved pain management and pain free rates

Hence, the questions chosen for this research investigation was “Does Morphine or Cannabis

improve the pain management among the patients living with cancer?”

2.2 Search strategy

This segment of the research proposition presents a brief idea of the precise steps adopted to

effectively finish the research study. A research technique is used step-by-step for the precise

operations which were conducted in the precise series to produce the required result for

completing the research. Here, the selected research technique was systemic evaluation

(Silverman 2016) to be used in this specific research analysis. In this situation, the scholarly

databases related to health care and therapeutic or clinical studies have been researched in

detailed manner. In order to define the pattern of the information findings on the subject, a

preliminary check will be made with Google's information repository. Based on the PICO query

a search will then be conducted for a comprehensive literature search the particular databases,

such as Medline and CINAHL.The search phrases that was utilized in conducting the research

study includes “morphine”, “cannabis”, “alternative pain medication”, “traditional pain

management”, “cancer pain”, “side effects”, “benefits”, “pain management” and “comparative

benefits”. A thorough and critical analysis of the studies was carried out using the inclusion and

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

16DISSERTATION

exclusion criteria. For this investigation, the research papers published after 2014, edited in

English, evaluated by peers and research on human subject chosen. All research plans and

evidence syntheses have been prioritized through publications that have consistently

strengthened accessible evidence. Scientific studies published in other languages than English

have been published before 2014, have not been peer- reviewed and have been omitted from

study clinical current studies on topics other than individuals (Flick 2018). Scientific papers

included in the analysis of evidence or systematic studies as the main format in this specific

investigation were not included in the evaluation separately but were also included as evidence in

the systemic assessment or the synthesis of evidence.

exclusion criteria. For this investigation, the research papers published after 2014, edited in

English, evaluated by peers and research on human subject chosen. All research plans and

evidence syntheses have been prioritized through publications that have consistently

strengthened accessible evidence. Scientific studies published in other languages than English

have been published before 2014, have not been peer- reviewed and have been omitted from

study clinical current studies on topics other than individuals (Flick 2018). Scientific papers

included in the analysis of evidence or systematic studies as the main format in this specific

investigation were not included in the evaluation separately but were also included as evidence in

the systemic assessment or the synthesis of evidence.

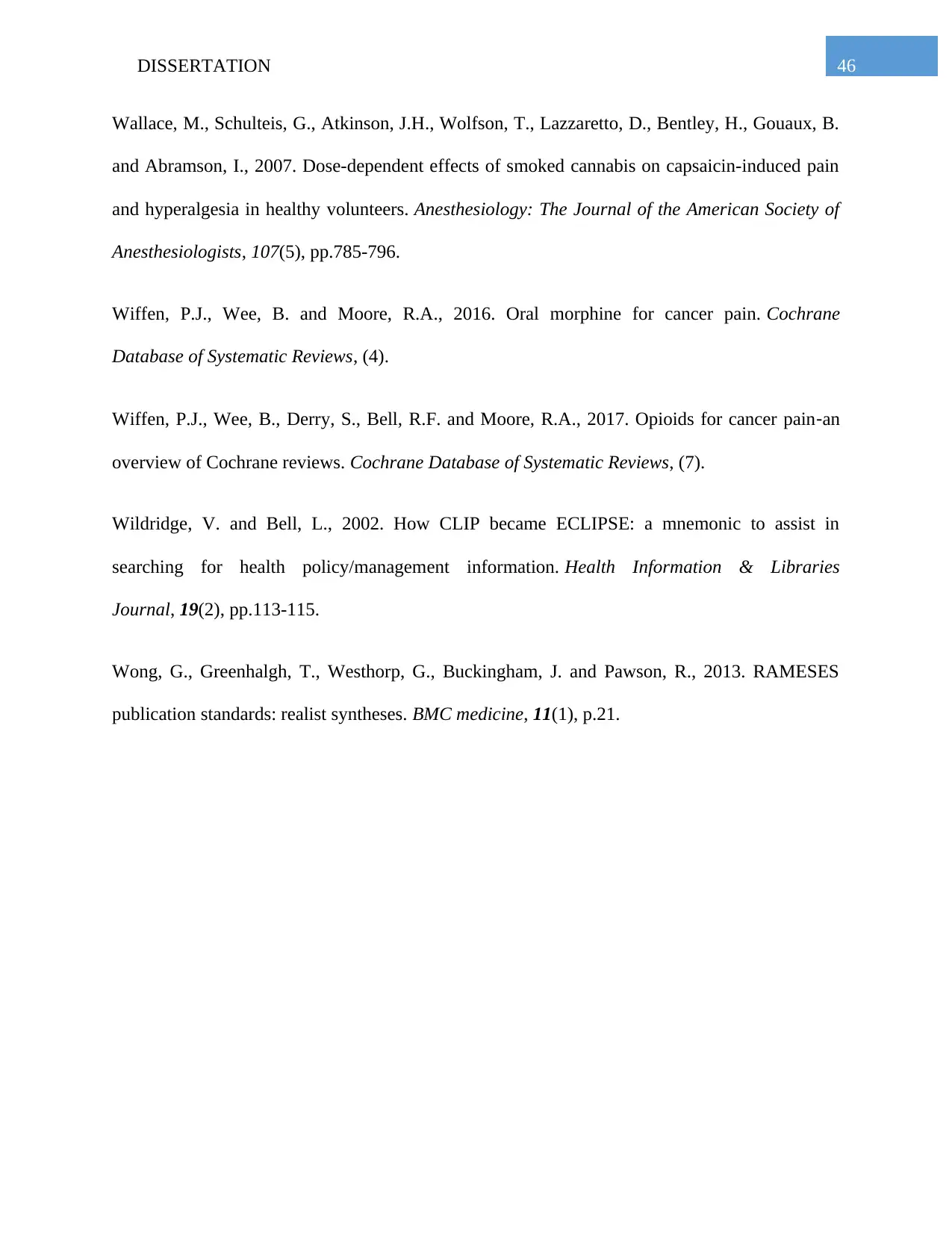

Identified articles through database searching

(n = 163)

Articles remained after duplicates

eliminated

(n = 135)

Records after duplicates removed

(n = 198)

Duplicates removed

(n = 28)

Duplicates removed

(n = 34)

Articles evaluated

(n = 135)

Records screened

(n = 198)

Articles omitted

(n = 124)

Records excluded

(n = 186)

Full text articles evaluated

for suitability

(n = 11)

Full-text articles assessed

for eligibility

(n = 12)

Full text articles omitted,

with reasons

(n = 5)

Full-text articles excluded,

with reasons

(n = 6)

Studies included in

qualitative synthesis

(n = 6)

Included

Screening

Eligibility

Identification

17DISSERTATION

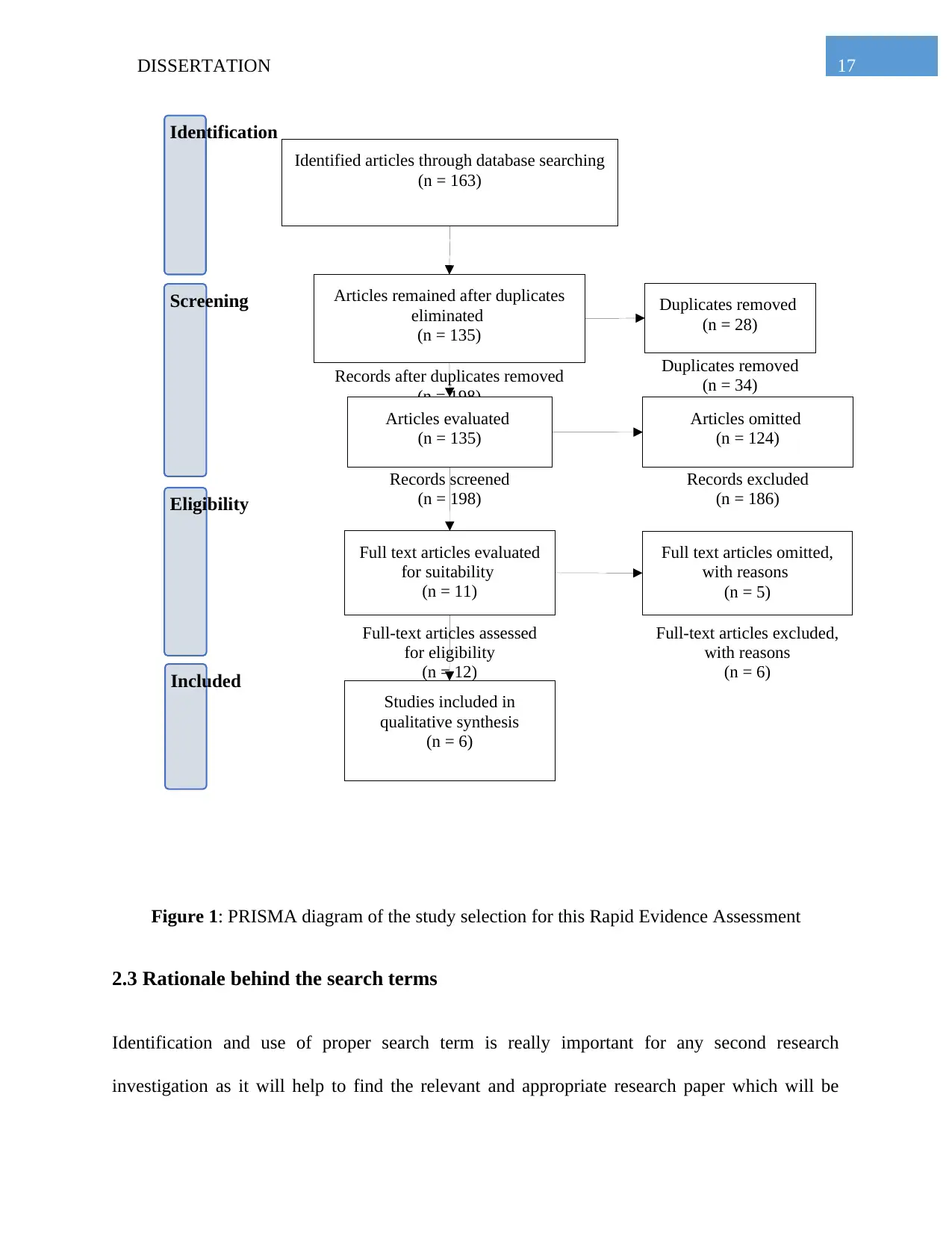

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram of the study selection for this Rapid Evidence Assessment

2.3 Rationale behind the search terms

Identification and use of proper search term is really important for any second research

investigation as it will help to find the relevant and appropriate research paper which will be

(n = 163)

Articles remained after duplicates

eliminated

(n = 135)

Records after duplicates removed

(n = 198)

Duplicates removed

(n = 28)

Duplicates removed

(n = 34)

Articles evaluated

(n = 135)

Records screened

(n = 198)

Articles omitted

(n = 124)

Records excluded

(n = 186)

Full text articles evaluated

for suitability

(n = 11)

Full-text articles assessed

for eligibility

(n = 12)

Full text articles omitted,

with reasons

(n = 5)

Full-text articles excluded,

with reasons

(n = 6)

Studies included in

qualitative synthesis

(n = 6)

Included

Screening

Eligibility

Identification

17DISSERTATION

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram of the study selection for this Rapid Evidence Assessment

2.3 Rationale behind the search terms

Identification and use of proper search term is really important for any second research

investigation as it will help to find the relevant and appropriate research paper which will be

18DISSERTATION

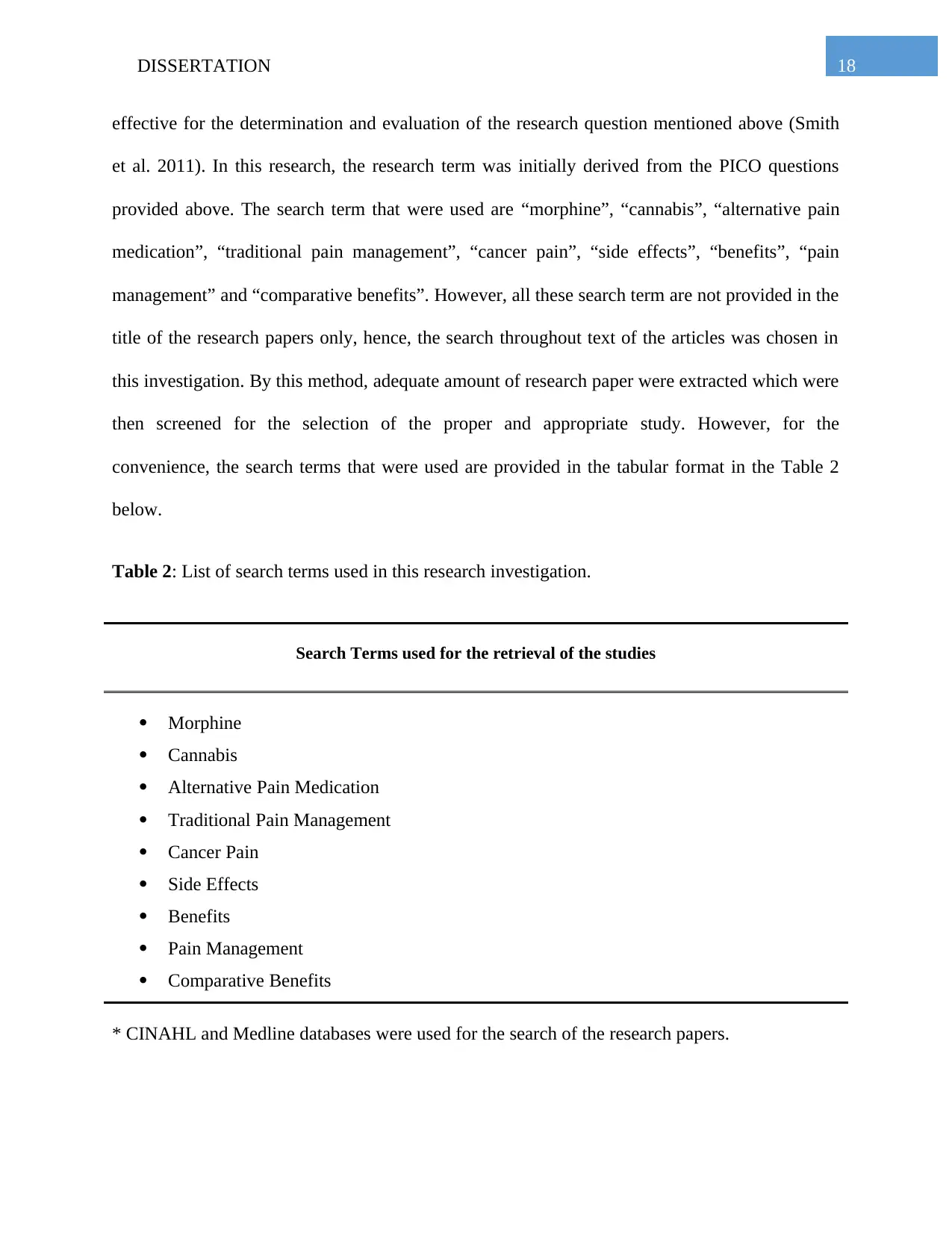

effective for the determination and evaluation of the research question mentioned above (Smith

et al. 2011). In this research, the research term was initially derived from the PICO questions

provided above. The search term that were used are “morphine”, “cannabis”, “alternative pain

medication”, “traditional pain management”, “cancer pain”, “side effects”, “benefits”, “pain

management” and “comparative benefits”. However, all these search term are not provided in the

title of the research papers only, hence, the search throughout text of the articles was chosen in

this investigation. By this method, adequate amount of research paper were extracted which were

then screened for the selection of the proper and appropriate study. However, for the

convenience, the search terms that were used are provided in the tabular format in the Table 2

below.

Table 2: List of search terms used in this research investigation.

Search Terms used for the retrieval of the studies

Morphine

Cannabis

Alternative Pain Medication

Traditional Pain Management

Cancer Pain

Side Effects

Benefits

Pain Management

Comparative Benefits

* CINAHL and Medline databases were used for the search of the research papers.

effective for the determination and evaluation of the research question mentioned above (Smith

et al. 2011). In this research, the research term was initially derived from the PICO questions

provided above. The search term that were used are “morphine”, “cannabis”, “alternative pain

medication”, “traditional pain management”, “cancer pain”, “side effects”, “benefits”, “pain

management” and “comparative benefits”. However, all these search term are not provided in the

title of the research papers only, hence, the search throughout text of the articles was chosen in

this investigation. By this method, adequate amount of research paper were extracted which were

then screened for the selection of the proper and appropriate study. However, for the

convenience, the search terms that were used are provided in the tabular format in the Table 2

below.

Table 2: List of search terms used in this research investigation.

Search Terms used for the retrieval of the studies

Morphine

Cannabis

Alternative Pain Medication

Traditional Pain Management

Cancer Pain

Side Effects

Benefits

Pain Management

Comparative Benefits

* CINAHL and Medline databases were used for the search of the research papers.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

19DISSERTATION

2.4 Article Selection

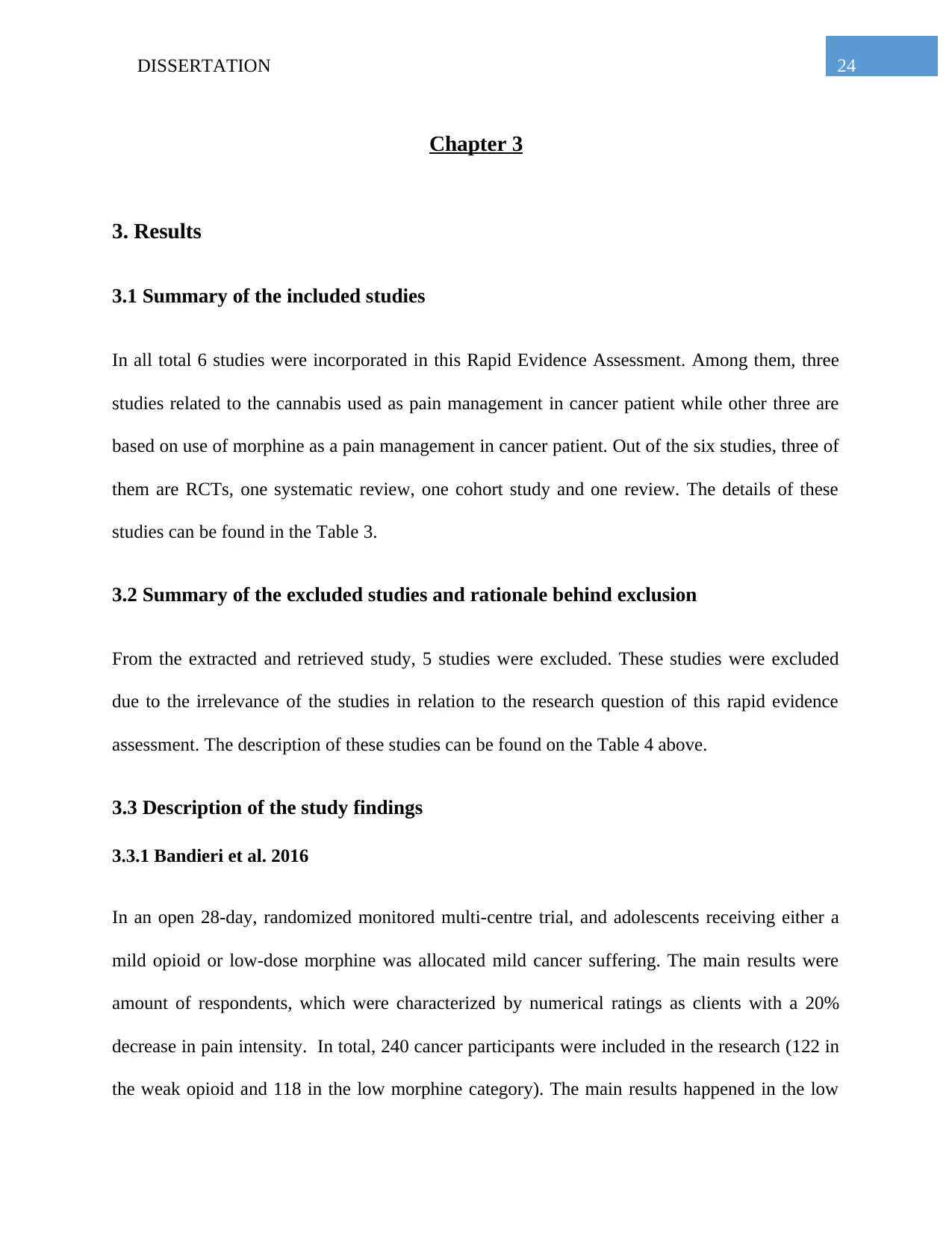

By using the above mentioned search terms all total of 163 articles were extracted from the

search databases. Out of these 163 articles, there were some duplicates of the retrieved articles. A

total number of 28 duplicates were present and they were removed from the search results. After

the removal of the duplicates, 135 articles were left in the search results which were then

screened for the eligibility of their relevancy. Out of these 135 screened articles, 11 articles were

selected which deals with the pain management by the interventions of either morphine or

cannabis. From these 11 articles, 6 were included in the study, as they are able to shed light in

the research question of this investigation and 5 were excluded due to their irrelevancy. The

details of the included study can be found in the Table 3 below and details of the excluded study

can be found on the Table 4 below.

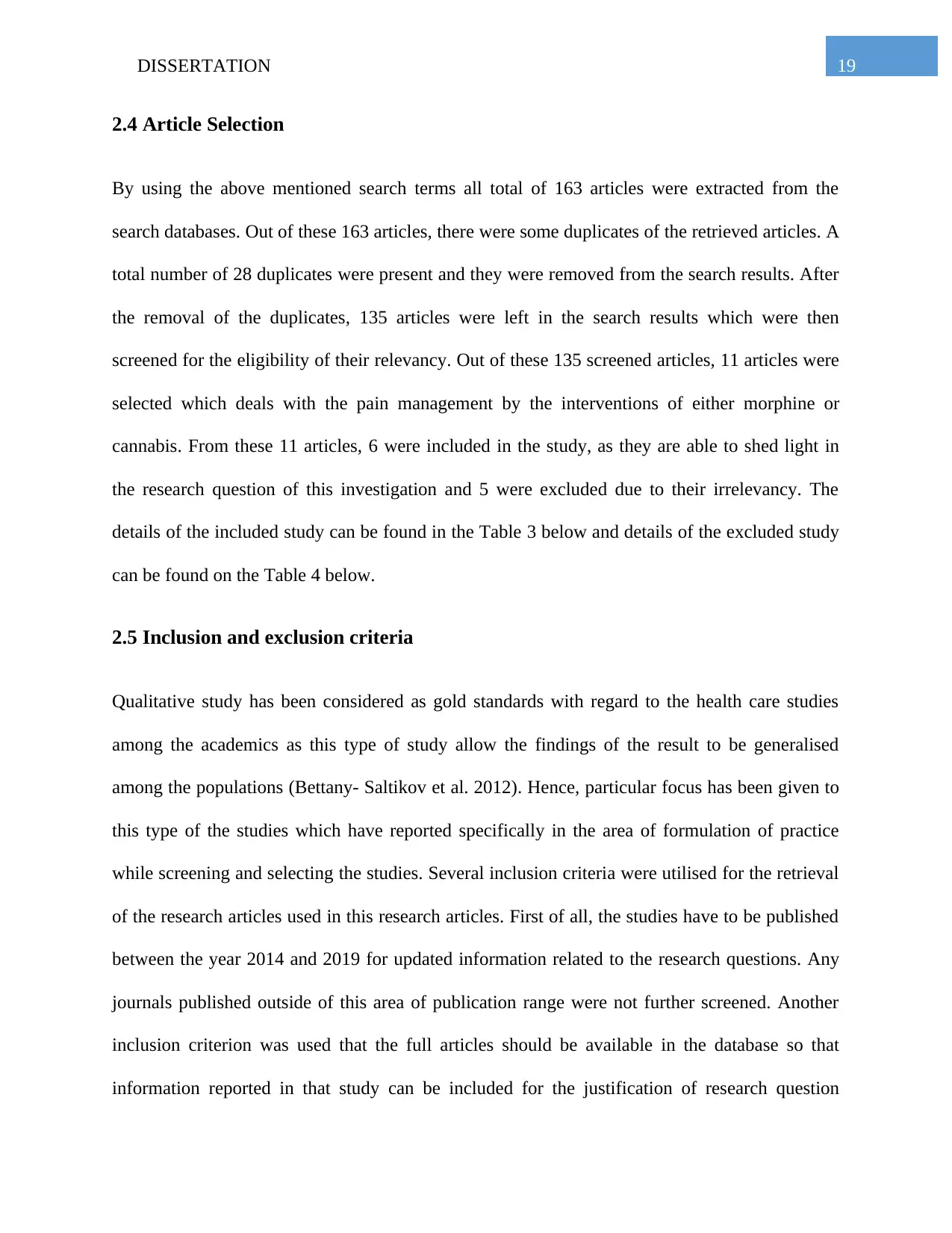

2.5 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Qualitative study has been considered as gold standards with regard to the health care studies

among the academics as this type of study allow the findings of the result to be generalised

among the populations (Bettany- Saltikov et al. 2012). Hence, particular focus has been given to

this type of the studies which have reported specifically in the area of formulation of practice

while screening and selecting the studies. Several inclusion criteria were utilised for the retrieval

of the research articles used in this research articles. First of all, the studies have to be published

between the year 2014 and 2019 for updated information related to the research questions. Any

journals published outside of this area of publication range were not further screened. Another

inclusion criterion was used that the full articles should be available in the database so that

information reported in that study can be included for the justification of research question

2.4 Article Selection

By using the above mentioned search terms all total of 163 articles were extracted from the

search databases. Out of these 163 articles, there were some duplicates of the retrieved articles. A

total number of 28 duplicates were present and they were removed from the search results. After

the removal of the duplicates, 135 articles were left in the search results which were then

screened for the eligibility of their relevancy. Out of these 135 screened articles, 11 articles were

selected which deals with the pain management by the interventions of either morphine or

cannabis. From these 11 articles, 6 were included in the study, as they are able to shed light in

the research question of this investigation and 5 were excluded due to their irrelevancy. The

details of the included study can be found in the Table 3 below and details of the excluded study

can be found on the Table 4 below.

2.5 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Qualitative study has been considered as gold standards with regard to the health care studies

among the academics as this type of study allow the findings of the result to be generalised

among the populations (Bettany- Saltikov et al. 2012). Hence, particular focus has been given to

this type of the studies which have reported specifically in the area of formulation of practice

while screening and selecting the studies. Several inclusion criteria were utilised for the retrieval

of the research articles used in this research articles. First of all, the studies have to be published

between the year 2014 and 2019 for updated information related to the research questions. Any

journals published outside of this area of publication range were not further screened. Another

inclusion criterion was used that the full articles should be available in the database so that

information reported in that study can be included for the justification of research question

20DISSERTATION

presented in the study. In addition to that, it was checked that the study should be available in the

English language for the understanding of the information portrayed in the study. During the

screening of the articles, particular focus was given in the relevancy of the information presented

in the journal with regard to the research question presented above. The studies whose

information were not relevant to the research question were excluded from this study despite

meeting the above mentioned inclusion criteria. There were 5 research articles retrieved from the

database which met these criteria. In addition to that all the articles have to be published in a

peer-reviewed journal; otherwise the study was not selected. Finally, 6 articles were selected

which have met all the criteria and relevant to the research questions. The details of the included

study can be found in the Table 3 below and details of the excluded study can be found on the

Table 4 below.

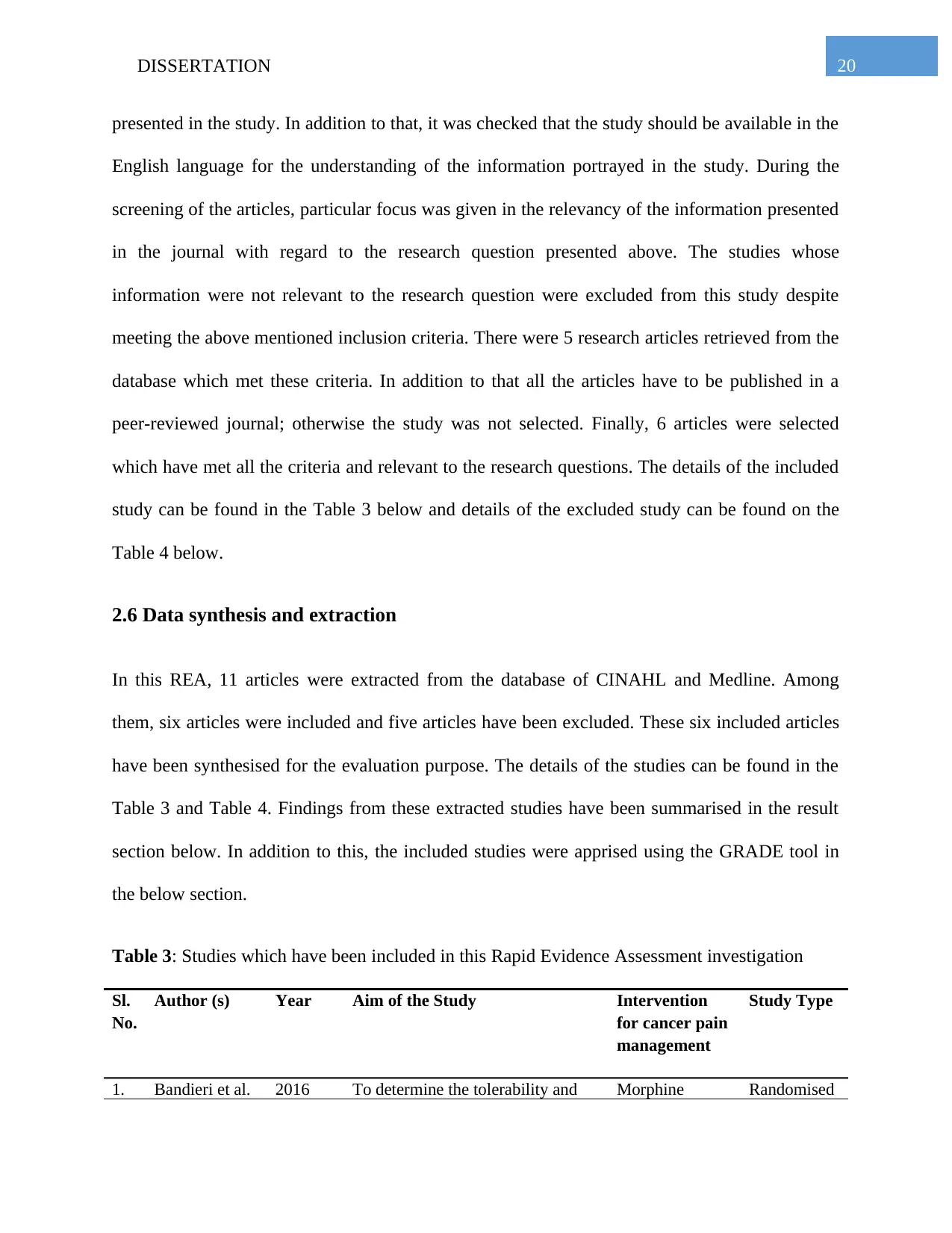

2.6 Data synthesis and extraction

In this REA, 11 articles were extracted from the database of CINAHL and Medline. Among

them, six articles were included and five articles have been excluded. These six included articles

have been synthesised for the evaluation purpose. The details of the studies can be found in the

Table 3 and Table 4. Findings from these extracted studies have been summarised in the result

section below. In addition to this, the included studies were apprised using the GRADE tool in

the below section.

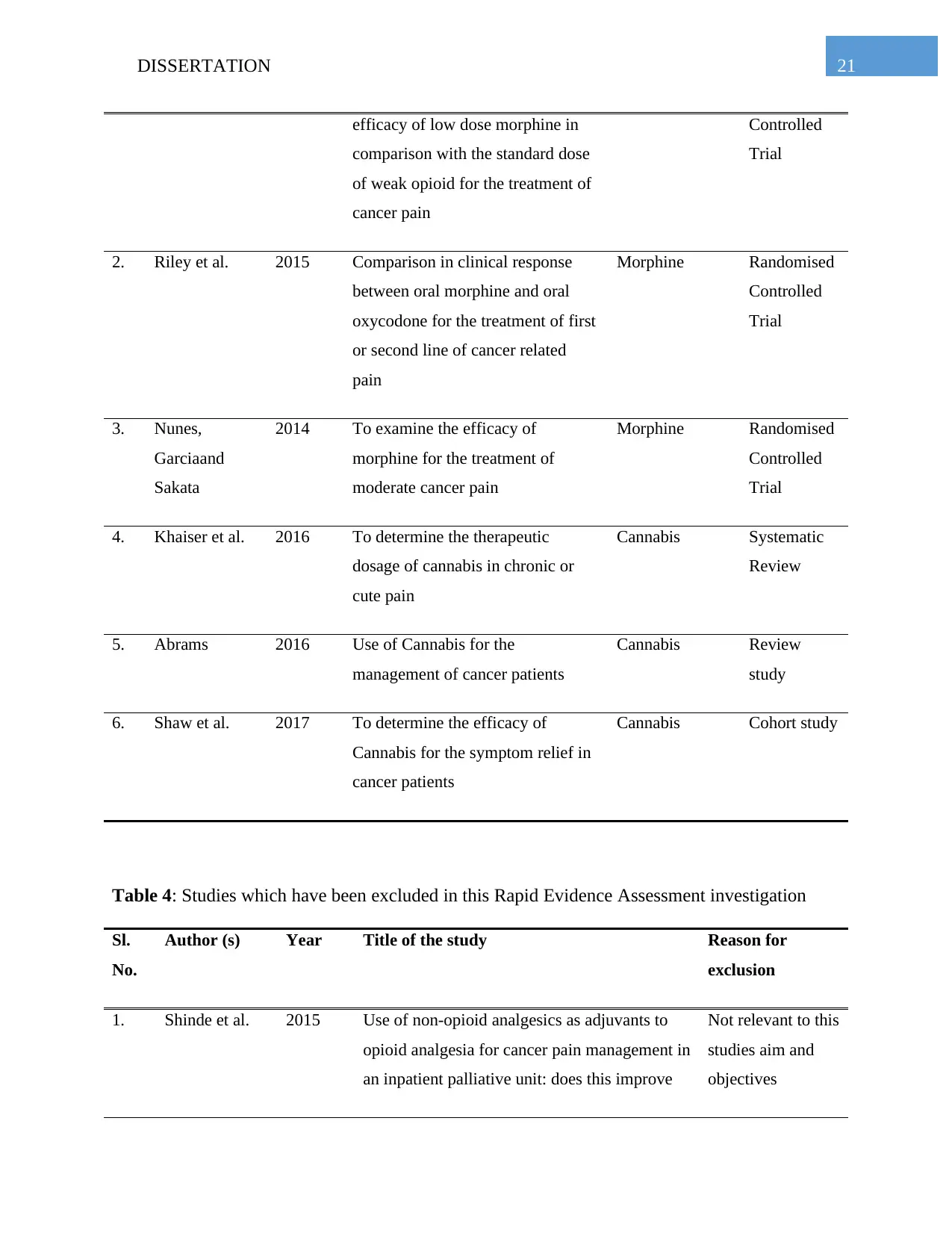

Table 3: Studies which have been included in this Rapid Evidence Assessment investigation

Sl.

No.

Author (s) Year Aim of the Study Intervention

for cancer pain

management

Study Type

1. Bandieri et al. 2016 To determine the tolerability and Morphine Randomised

presented in the study. In addition to that, it was checked that the study should be available in the

English language for the understanding of the information portrayed in the study. During the

screening of the articles, particular focus was given in the relevancy of the information presented

in the journal with regard to the research question presented above. The studies whose

information were not relevant to the research question were excluded from this study despite

meeting the above mentioned inclusion criteria. There were 5 research articles retrieved from the

database which met these criteria. In addition to that all the articles have to be published in a

peer-reviewed journal; otherwise the study was not selected. Finally, 6 articles were selected

which have met all the criteria and relevant to the research questions. The details of the included

study can be found in the Table 3 below and details of the excluded study can be found on the

Table 4 below.

2.6 Data synthesis and extraction

In this REA, 11 articles were extracted from the database of CINAHL and Medline. Among

them, six articles were included and five articles have been excluded. These six included articles

have been synthesised for the evaluation purpose. The details of the studies can be found in the

Table 3 and Table 4. Findings from these extracted studies have been summarised in the result

section below. In addition to this, the included studies were apprised using the GRADE tool in

the below section.

Table 3: Studies which have been included in this Rapid Evidence Assessment investigation

Sl.

No.

Author (s) Year Aim of the Study Intervention

for cancer pain

management

Study Type

1. Bandieri et al. 2016 To determine the tolerability and Morphine Randomised

21DISSERTATION

efficacy of low dose morphine in

comparison with the standard dose

of weak opioid for the treatment of

cancer pain

Controlled

Trial

2. Riley et al. 2015 Comparison in clinical response

between oral morphine and oral

oxycodone for the treatment of first

or second line of cancer related

pain

Morphine Randomised

Controlled

Trial

3. Nunes,

Garciaand

Sakata

2014 To examine the efficacy of

morphine for the treatment of

moderate cancer pain

Morphine Randomised

Controlled

Trial

4. Khaiser et al. 2016 To determine the therapeutic

dosage of cannabis in chronic or

cute pain

Cannabis Systematic

Review

5. Abrams 2016 Use of Cannabis for the

management of cancer patients

Cannabis Review

study

6. Shaw et al. 2017 To determine the efficacy of

Cannabis for the symptom relief in

cancer patients

Cannabis Cohort study

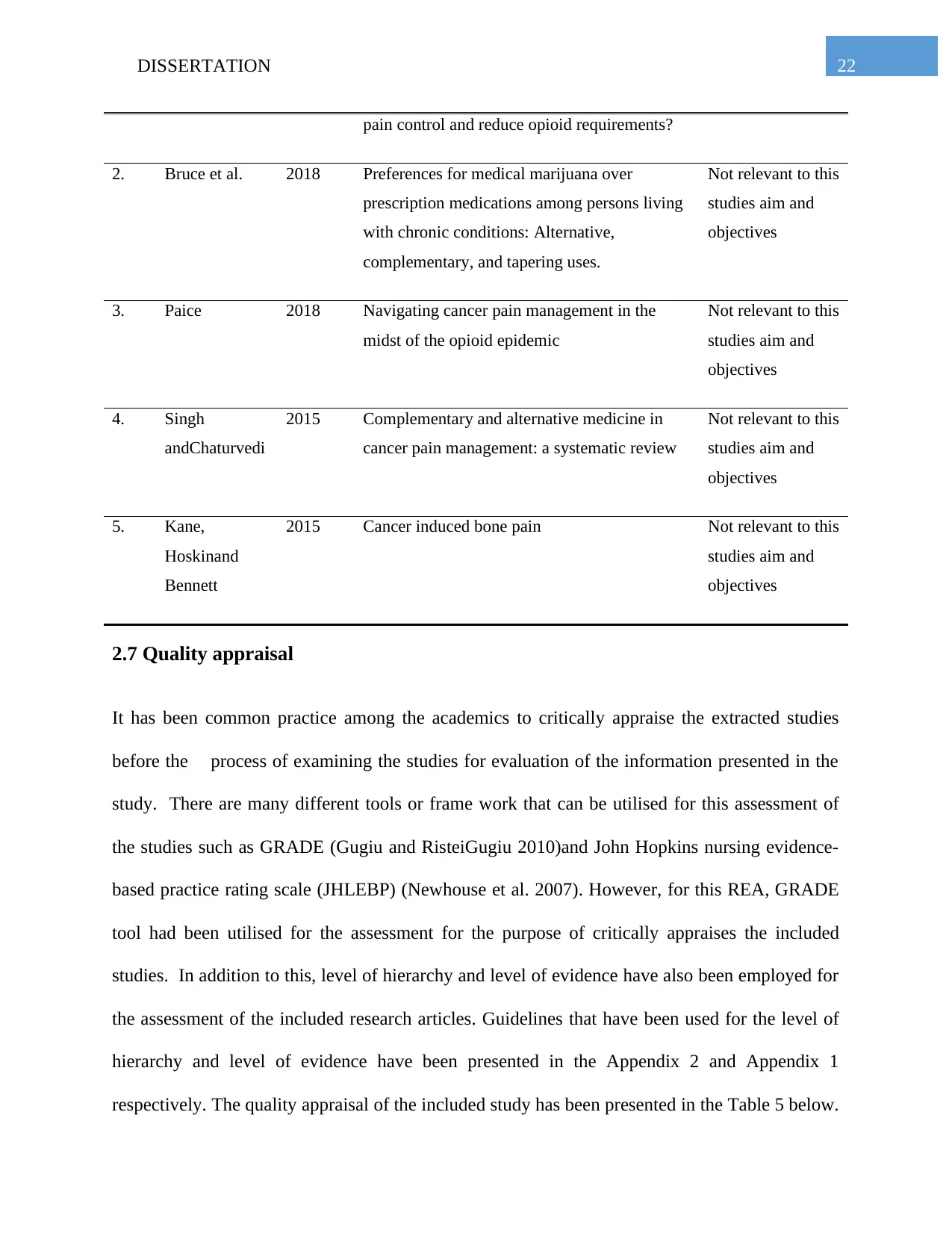

Table 4: Studies which have been excluded in this Rapid Evidence Assessment investigation

Sl.

No.

Author (s) Year Title of the study Reason for

exclusion

1. Shinde et al. 2015 Use of non-opioid analgesics as adjuvants to

opioid analgesia for cancer pain management in

an inpatient palliative unit: does this improve

Not relevant to this

studies aim and

objectives

efficacy of low dose morphine in

comparison with the standard dose

of weak opioid for the treatment of

cancer pain

Controlled

Trial

2. Riley et al. 2015 Comparison in clinical response

between oral morphine and oral

oxycodone for the treatment of first

or second line of cancer related

pain

Morphine Randomised

Controlled

Trial

3. Nunes,

Garciaand

Sakata

2014 To examine the efficacy of

morphine for the treatment of

moderate cancer pain

Morphine Randomised

Controlled

Trial

4. Khaiser et al. 2016 To determine the therapeutic

dosage of cannabis in chronic or

cute pain

Cannabis Systematic

Review

5. Abrams 2016 Use of Cannabis for the

management of cancer patients

Cannabis Review

study

6. Shaw et al. 2017 To determine the efficacy of

Cannabis for the symptom relief in

cancer patients

Cannabis Cohort study

Table 4: Studies which have been excluded in this Rapid Evidence Assessment investigation

Sl.

No.

Author (s) Year Title of the study Reason for

exclusion

1. Shinde et al. 2015 Use of non-opioid analgesics as adjuvants to

opioid analgesia for cancer pain management in

an inpatient palliative unit: does this improve

Not relevant to this

studies aim and

objectives

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

22DISSERTATION

pain control and reduce opioid requirements?

2. Bruce et al. 2018 Preferences for medical marijuana over

prescription medications among persons living

with chronic conditions: Alternative,

complementary, and tapering uses.

Not relevant to this

studies aim and

objectives

3. Paice 2018 Navigating cancer pain management in the

midst of the opioid epidemic

Not relevant to this

studies aim and

objectives

4. Singh

andChaturvedi

2015 Complementary and alternative medicine in

cancer pain management: a systematic review

Not relevant to this

studies aim and

objectives

5. Kane,

Hoskinand

Bennett

2015 Cancer induced bone pain Not relevant to this

studies aim and

objectives

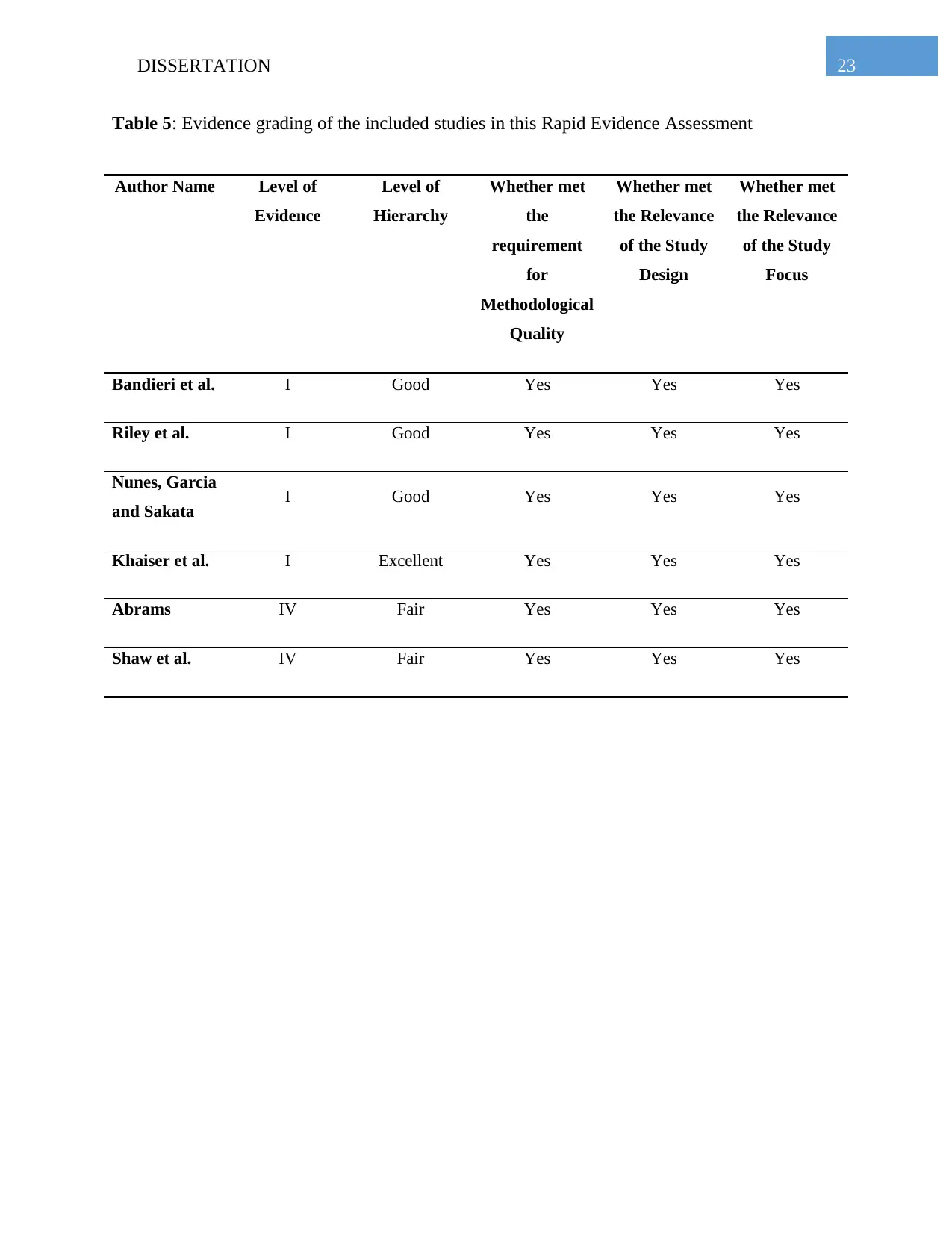

2.7 Quality appraisal

It has been common practice among the academics to critically appraise the extracted studies

before the process of examining the studies for evaluation of the information presented in the

study. There are many different tools or frame work that can be utilised for this assessment of

the studies such as GRADE (Gugiu and RisteiGugiu 2010)and John Hopkins nursing evidence-

based practice rating scale (JHLEBP) (Newhouse et al. 2007). However, for this REA, GRADE

tool had been utilised for the assessment for the purpose of critically appraises the included

studies. In addition to this, level of hierarchy and level of evidence have also been employed for

the assessment of the included research articles. Guidelines that have been used for the level of

hierarchy and level of evidence have been presented in the Appendix 2 and Appendix 1

respectively. The quality appraisal of the included study has been presented in the Table 5 below.

pain control and reduce opioid requirements?

2. Bruce et al. 2018 Preferences for medical marijuana over

prescription medications among persons living

with chronic conditions: Alternative,

complementary, and tapering uses.

Not relevant to this

studies aim and

objectives

3. Paice 2018 Navigating cancer pain management in the

midst of the opioid epidemic

Not relevant to this

studies aim and

objectives

4. Singh

andChaturvedi

2015 Complementary and alternative medicine in

cancer pain management: a systematic review

Not relevant to this

studies aim and

objectives

5. Kane,

Hoskinand

Bennett

2015 Cancer induced bone pain Not relevant to this

studies aim and

objectives

2.7 Quality appraisal

It has been common practice among the academics to critically appraise the extracted studies

before the process of examining the studies for evaluation of the information presented in the

study. There are many different tools or frame work that can be utilised for this assessment of

the studies such as GRADE (Gugiu and RisteiGugiu 2010)and John Hopkins nursing evidence-

based practice rating scale (JHLEBP) (Newhouse et al. 2007). However, for this REA, GRADE

tool had been utilised for the assessment for the purpose of critically appraises the included

studies. In addition to this, level of hierarchy and level of evidence have also been employed for

the assessment of the included research articles. Guidelines that have been used for the level of

hierarchy and level of evidence have been presented in the Appendix 2 and Appendix 1

respectively. The quality appraisal of the included study has been presented in the Table 5 below.

23DISSERTATION

Table 5: Evidence grading of the included studies in this Rapid Evidence Assessment

Author Name Level of

Evidence

Level of

Hierarchy

Whether met

the

requirement

for

Methodological

Quality

Whether met

the Relevance

of the Study

Design

Whether met

the Relevance

of the Study

Focus

Bandieri et al. I Good Yes Yes Yes

Riley et al. I Good Yes Yes Yes

Nunes, Garcia

and Sakata I Good Yes Yes Yes

Khaiser et al. I Excellent Yes Yes Yes

Abrams IV Fair Yes Yes Yes

Shaw et al. IV Fair Yes Yes Yes

Table 5: Evidence grading of the included studies in this Rapid Evidence Assessment

Author Name Level of

Evidence

Level of

Hierarchy

Whether met

the

requirement

for

Methodological

Quality

Whether met

the Relevance

of the Study

Design

Whether met

the Relevance

of the Study

Focus

Bandieri et al. I Good Yes Yes Yes

Riley et al. I Good Yes Yes Yes

Nunes, Garcia

and Sakata I Good Yes Yes Yes

Khaiser et al. I Excellent Yes Yes Yes

Abrams IV Fair Yes Yes Yes

Shaw et al. IV Fair Yes Yes Yes

24DISSERTATION

Chapter 3

3. Results

3.1 Summary of the included studies

In all total 6 studies were incorporated in this Rapid Evidence Assessment. Among them, three

studies related to the cannabis used as pain management in cancer patient while other three are

based on use of morphine as a pain management in cancer patient. Out of the six studies, three of

them are RCTs, one systematic review, one cohort study and one review. The details of these

studies can be found in the Table 3.

3.2 Summary of the excluded studies and rationale behind exclusion

From the extracted and retrieved study, 5 studies were excluded. These studies were excluded

due to the irrelevance of the studies in relation to the research question of this rapid evidence

assessment. The description of these studies can be found on the Table 4 above.

3.3 Description of the study findings

3.3.1 Bandieri et al. 2016

In an open 28-day, randomized monitored multi-centre trial, and adolescents receiving either a

mild opioid or low-dose morphine was allocated mild cancer suffering. The main results were

amount of respondents, which were characterized by numerical ratings as clients with a 20%

decrease in pain intensity. In total, 240 cancer participants were included in the research (122 in

the weak opioid and 118 in the low morphine category). The main results happened in the low

Chapter 3

3. Results

3.1 Summary of the included studies

In all total 6 studies were incorporated in this Rapid Evidence Assessment. Among them, three

studies related to the cannabis used as pain management in cancer patient while other three are

based on use of morphine as a pain management in cancer patient. Out of the six studies, three of

them are RCTs, one systematic review, one cohort study and one review. The details of these

studies can be found in the Table 3.

3.2 Summary of the excluded studies and rationale behind exclusion

From the extracted and retrieved study, 5 studies were excluded. These studies were excluded

due to the irrelevance of the studies in relation to the research question of this rapid evidence

assessment. The description of these studies can be found on the Table 4 above.

3.3 Description of the study findings

3.3.1 Bandieri et al. 2016

In an open 28-day, randomized monitored multi-centre trial, and adolescents receiving either a

mild opioid or low-dose morphine was allocated mild cancer suffering. The main results were

amount of respondents, which were characterized by numerical ratings as clients with a 20%

decrease in pain intensity. In total, 240 cancer participants were included in the research (122 in

the weak opioid and 118 in the low morphine category). The main results happened in the low

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

25DISSERTATION

dose morphine unit at 88.2 and 57.7% (odd danger, 6.18; 95% CI, 3.12 to 12.24; P less than

0.001). The main result was in the low dose community. In the low-dose morphine cluster, the

proportion of respondents was greater at 1 week. In the cluster of low dose morphine it was

considerably greater (P less than 0.001) for statistical significant (greater than or equal to 30

percent) and extremely significant (greater than or equal to 50 per cent) pain decrease from

baseline. In the weak- opioid community a shift in the therapy allocated was more common due

to insufficient analgesia. Patients were better off as a particular disease in the morphine category

based on the overall symptom rating of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. The

negative impacts in both organizations were comparable.13 individuals (eight in a M and five in

the WO group) were not included in this assessment from the initial randomized cohort of 240

individuals, because they left the survey for different times before the first measurement of the

main endpoint. 88.2 percent (97 out of 110) in the M band and 54.7 percent (64 of 117) of WO

groups (Odds Ratio, 6.18; 95 percent CI, 3.12 to 12.24; P = .001) accomplished the main start

point with a 20 percent pain decrease or more from baseline. This outcome was not modified by

complete adjustment for baseline covariates. The overall situation of the clients was superior in

morphine (average score, 10; IQR, 6 to 15) compared to the low- opioid community (average

score, 19; IQR, 10 to 17; P, 001).). The overall ESAS rating was superior in children. Both

medicines have been well tolerated. Only five nurses in each community stopped therapy due to

negative impacts or tolerability, respectively (three and two patients per group). There were no

variations between the two organizations in the severity and frequency of opioid reactions.

3.3.2 Riley et al. 2015

Patients suffering from cancer related discomfort were alerted to either oral oxycodone or

morphine as first-line therapy in this potential, open label, randomized monitored study with a

dose morphine unit at 88.2 and 57.7% (odd danger, 6.18; 95% CI, 3.12 to 12.24; P less than

0.001). The main result was in the low dose community. In the low-dose morphine cluster, the

proportion of respondents was greater at 1 week. In the cluster of low dose morphine it was

considerably greater (P less than 0.001) for statistical significant (greater than or equal to 30

percent) and extremely significant (greater than or equal to 50 per cent) pain decrease from

baseline. In the weak- opioid community a shift in the therapy allocated was more common due

to insufficient analgesia. Patients were better off as a particular disease in the morphine category

based on the overall symptom rating of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. The

negative impacts in both organizations were comparable.13 individuals (eight in a M and five in

the WO group) were not included in this assessment from the initial randomized cohort of 240

individuals, because they left the survey for different times before the first measurement of the

main endpoint. 88.2 percent (97 out of 110) in the M band and 54.7 percent (64 of 117) of WO

groups (Odds Ratio, 6.18; 95 percent CI, 3.12 to 12.24; P = .001) accomplished the main start

point with a 20 percent pain decrease or more from baseline. This outcome was not modified by

complete adjustment for baseline covariates. The overall situation of the clients was superior in

morphine (average score, 10; IQR, 6 to 15) compared to the low- opioid community (average

score, 19; IQR, 10 to 17; P, 001).). The overall ESAS rating was superior in children. Both

medicines have been well tolerated. Only five nurses in each community stopped therapy due to

negative impacts or tolerability, respectively (three and two patients per group). There were no

variations between the two organizations in the severity and frequency of opioid reactions.

3.3.2 Riley et al. 2015

Patients suffering from cancer related discomfort were alerted to either oral oxycodone or

morphine as first-line therapy in this potential, open label, randomized monitored study with a

26DISSERTATION

chosen cross over stage. Until the person indicated appropriate pain control, dose was titrated

separately. The alternative opioid has been moved in patients who have failed to react to the

first-line opium (be they due to insufficient analgesia or negative impacts unacceptable). The

recruitment of two hundred patients was considered in this investigation. Intention to treat

and analyze the number of patients reacting to morphine (62 per cent) or oxycodone (67 per cent)

was used as a first-line opioid which was not significantly distinguished by intention to treat

(total number of patients = 198, morphine = 98, oxycodone =100). Simultaneous changes to

either morphine (67 per cent) or oxycodone (52 per cent) have not been observed in the ensuing

reaction. An assessment of a protocol showed that when both opioids were accessible a 95

percent reaction frequency was accessible. In first-line respondents or non- responders there was

no distinction in negative response rates among oxycodone and morphine. The most prevalent

cause for the first line opioid change was intolerable side effects with sleepiness as the most

prevalent negative response. Although dose increases were observed, some nurses (8 per

cent) turned because of unrestrained pain, and the remaining 28 per cent had an uninhibited pain

mix and intolerable side impacts. The average pre- contaminated dose of morphine was 60 mg

(range 30 to 260 mg) with a median post-contamination dose of 60 mg (range 20 to130 mg) in

respondents randomized to morphine. Five patients with morphine were assumed to have a

severe negative event (five constipations). There was a presumed severe response to eight

oxycodone patients (two constipations, three confusions, vomiting, and nausea, somnolence and

delusions, and secondary virus poisoning to the opioid). Seven people who received morphine

encountered unprecedented severe negative occurrences (arthritis, other negative responses to

medicines, falling, lower gastrointestinal bleeding, infectious aneurysm, mistake in the

prescription of medicines and severe coronary syndrome).

chosen cross over stage. Until the person indicated appropriate pain control, dose was titrated

separately. The alternative opioid has been moved in patients who have failed to react to the

first-line opium (be they due to insufficient analgesia or negative impacts unacceptable). The

recruitment of two hundred patients was considered in this investigation. Intention to treat

and analyze the number of patients reacting to morphine (62 per cent) or oxycodone (67 per cent)

was used as a first-line opioid which was not significantly distinguished by intention to treat

(total number of patients = 198, morphine = 98, oxycodone =100). Simultaneous changes to

either morphine (67 per cent) or oxycodone (52 per cent) have not been observed in the ensuing

reaction. An assessment of a protocol showed that when both opioids were accessible a 95

percent reaction frequency was accessible. In first-line respondents or non- responders there was

no distinction in negative response rates among oxycodone and morphine. The most prevalent

cause for the first line opioid change was intolerable side effects with sleepiness as the most

prevalent negative response. Although dose increases were observed, some nurses (8 per

cent) turned because of unrestrained pain, and the remaining 28 per cent had an uninhibited pain