Factors Affecting Faculty Satisfaction with Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/23

|15

|7437

|376

AI Summary

This article discusses the importance of faculty satisfaction in online courses and identifies factors affecting satisfaction. The study confirms that student-related, instructor-related, and institution-related factors affect faculty satisfaction. The article also defines distance education and online education, and discusses student satisfaction and faculty satisfaction as pillars of quality in online education. Theoretical frameworks and motivating factors for faculty participation in online education are also discussed.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Distance Education

Vol. 30, No. 1, May 2009, 103–116

ISSN 0158-7919 print/ISSN 1475-0198 online

© 2009 Open and Distance Learning Association of Australia, Inc.

DOI: 10.1080/01587910902845949

http://www.informaworld.com

Factors influencing faculty satisfaction with online teaching and

learning in higher education

Doris U. Bolliger* and Oksana Wasilik

Adult Learning and Technology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, USA

Taylor and FrancisCDIE_A_384766.sgm

(Received 7 September 2008; final version received 23 February 2009)

10.1080/01587910902845949Distance Education0158-7919 (print)/1475-0198 (online)Research Article2009Open and Distance Learning Association of Australia, Inc.301000000May 2009DorisBolligerdorisbolliger@gmail.com

Faculty satisfaction is considered an important factor of quality in online courses.

A study was conducted to identify and confirm factors affecting the satisfaction of

online faculty at a small research university, and to develop and validate an

instrument that can be used to measure perceived faculty satisfaction in the context

of the online learning environment. The online faculty satisfaction survey (OFSS)

was developed and administered to all instructors who had taught an online course

in fall 2007 or spring 2008 at a small research university in the USA. One hundred

and two individuals completed the web-based questionnaire. Results confirm that

three factors affect satisfaction of faculty in the online environment: student-

related, instructor-related, and institution-related factors.

Keywords: distance education; factor analysis; faculty satisfaction; higher

education; online teaching

Introduction

Distance education has become a fast-growing delivery method in higher education in

the USA. According to a report by Allen and Seaman (2007), during the fall 2006

semester approximately 20% of all higher education students in the USA were

enrolled in at least one online course. In fall 2005, enrollment in online courses expe-

rienced a 36.5% growth rate. The following year online enrollment experienced an

increase of 9.7%. By 2006, almost 35% of higher education institutions offered entire

programs online.

Reasons for offering online courses include improved student access, higher

degree completion rates, and the appeal of online courses to nontraditional students.

In contrast, institutions indicate barriers to the adoption of online courses include the

lack of online student discipline, the lack of faculty acceptance, and high costs asso-

ciated with online development and delivery (Allen & Seaman, 2007).

Moore and Kearsley (1996) have defined distance learning as a learning environ-

ment where ‘students and teachers are separated by distance and sometimes by time’

(p. 1). Rovai, Ponton, and Baker (2008) emphasized that if any element in structured

learning is separated by ‘time and/or geography’ (p. 1), then the learning takes place

in a distance learning setting. Online education is a process by which students and teach-

ers communicate with one another and interact with course content via Internet-based

learning technologies (Curran, 2008). A course is considered an online course if 80%

*Corresponding author. Email: dorisbolliger@gmail.com

Vol. 30, No. 1, May 2009, 103–116

ISSN 0158-7919 print/ISSN 1475-0198 online

© 2009 Open and Distance Learning Association of Australia, Inc.

DOI: 10.1080/01587910902845949

http://www.informaworld.com

Factors influencing faculty satisfaction with online teaching and

learning in higher education

Doris U. Bolliger* and Oksana Wasilik

Adult Learning and Technology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, USA

Taylor and FrancisCDIE_A_384766.sgm

(Received 7 September 2008; final version received 23 February 2009)

10.1080/01587910902845949Distance Education0158-7919 (print)/1475-0198 (online)Research Article2009Open and Distance Learning Association of Australia, Inc.301000000May 2009DorisBolligerdorisbolliger@gmail.com

Faculty satisfaction is considered an important factor of quality in online courses.

A study was conducted to identify and confirm factors affecting the satisfaction of

online faculty at a small research university, and to develop and validate an

instrument that can be used to measure perceived faculty satisfaction in the context

of the online learning environment. The online faculty satisfaction survey (OFSS)

was developed and administered to all instructors who had taught an online course

in fall 2007 or spring 2008 at a small research university in the USA. One hundred

and two individuals completed the web-based questionnaire. Results confirm that

three factors affect satisfaction of faculty in the online environment: student-

related, instructor-related, and institution-related factors.

Keywords: distance education; factor analysis; faculty satisfaction; higher

education; online teaching

Introduction

Distance education has become a fast-growing delivery method in higher education in

the USA. According to a report by Allen and Seaman (2007), during the fall 2006

semester approximately 20% of all higher education students in the USA were

enrolled in at least one online course. In fall 2005, enrollment in online courses expe-

rienced a 36.5% growth rate. The following year online enrollment experienced an

increase of 9.7%. By 2006, almost 35% of higher education institutions offered entire

programs online.

Reasons for offering online courses include improved student access, higher

degree completion rates, and the appeal of online courses to nontraditional students.

In contrast, institutions indicate barriers to the adoption of online courses include the

lack of online student discipline, the lack of faculty acceptance, and high costs asso-

ciated with online development and delivery (Allen & Seaman, 2007).

Moore and Kearsley (1996) have defined distance learning as a learning environ-

ment where ‘students and teachers are separated by distance and sometimes by time’

(p. 1). Rovai, Ponton, and Baker (2008) emphasized that if any element in structured

learning is separated by ‘time and/or geography’ (p. 1), then the learning takes place

in a distance learning setting. Online education is a process by which students and teach-

ers communicate with one another and interact with course content via Internet-based

learning technologies (Curran, 2008). A course is considered an online course if 80%

*Corresponding author. Email: dorisbolliger@gmail.com

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

104 D.U. Bolliger and O. Wasilik

or more of the content is delivered via the Internet (Simonson, Smaldino, Albright, &

Zvacek, 2009).

It is important to inquire about student and faculty perceptions of campus environ-

ments in order to assist campus leaders in changing policies that will lead to improve-

ment of teaching and learning conditions, if necessary (Baird, 1980). The commitment

of faculty to online education is valuable to educational institutions (Curran, 2008)

and important in the success of new distance education programs (Betts, 1998).

However, online teaching is complex and demanding on faculty, which can lead to

burnout, according to Hogan and McKnight (2007).

Faculty satisfaction is one of the five pillars of quality, together with student satis-

faction, learning effectiveness, access, and institutional cost-effectiveness (Sloan

Consortium, 2002). Components of faculty satisfaction need to be investigated as

online education becomes more prevalent and dynamic forces such as adoption rates,

learner expectations, levels of support, and other conditions continue to change.

Theoretical framework

Critics of online education have questioned the value, effectiveness, and quality of

online education. Ulmer, Watson, and Derby (2007) examined perceptions of faculty

pertaining to the value of distance education and reported statistically significant differ-

ences in findings between faculty with and without distance education experience.

Their results suggest that experienced faculty view distance education as effective in

terms of student performance and instructor-to-student interaction, and they ‘promote

and recommend engagement in distance education’ (p. 69). However, researchers have

reported conflicting results regarding the performance of online students. Some experts

have reported no significant differences in levels of performance, whereas others have

reported similar levels of online student achievement compared to campus-based

courses (Hislop, 2000). Schutte (1996) reported that student performance was higher

in an online course than in a traditional course. Olson and Wisher (2002) reviewed 47

online course evaluation reports published between 1996 and 2002 and suggested that

online instruction ‘appears to be an improvement over conventional classroom instruc-

tion’ (p. 11). Undoubtedly, this topic warrants further investigation before we can draw

conclusions about the effectiveness of online learning.

Quality is important in the delivery of all courses and programs, regardless of the

environment in which they are delivered. Two of the five elements in the Sloan

Consortium’s quality framework for online education are student satisfaction and

faculty satisfaction. These pillars of quality (Sloan Consortium, 2002) need to be

assessed on an ongoing basis.

Student satisfaction

Student satisfaction is defined as the student’s perceived value of his or her educa-

tional experiences at an educational institution (Astin, 1993). ‘Significant differences

still exist in the way students perceive their online experiences during learning’

(Muilenburg & Berge, 2005, p. 29). Perceptions about their learning experiences can

influence students in their decision to continue with the course (Carr, 2000) and

impact levels of satisfaction with overall online learning experiences (Kenny, 2003).

Student satisfaction, according to the American Distance Education Consortium

(ADEC, n.d.), ‘is the most important key to continue learning’ (¶5).

or more of the content is delivered via the Internet (Simonson, Smaldino, Albright, &

Zvacek, 2009).

It is important to inquire about student and faculty perceptions of campus environ-

ments in order to assist campus leaders in changing policies that will lead to improve-

ment of teaching and learning conditions, if necessary (Baird, 1980). The commitment

of faculty to online education is valuable to educational institutions (Curran, 2008)

and important in the success of new distance education programs (Betts, 1998).

However, online teaching is complex and demanding on faculty, which can lead to

burnout, according to Hogan and McKnight (2007).

Faculty satisfaction is one of the five pillars of quality, together with student satis-

faction, learning effectiveness, access, and institutional cost-effectiveness (Sloan

Consortium, 2002). Components of faculty satisfaction need to be investigated as

online education becomes more prevalent and dynamic forces such as adoption rates,

learner expectations, levels of support, and other conditions continue to change.

Theoretical framework

Critics of online education have questioned the value, effectiveness, and quality of

online education. Ulmer, Watson, and Derby (2007) examined perceptions of faculty

pertaining to the value of distance education and reported statistically significant differ-

ences in findings between faculty with and without distance education experience.

Their results suggest that experienced faculty view distance education as effective in

terms of student performance and instructor-to-student interaction, and they ‘promote

and recommend engagement in distance education’ (p. 69). However, researchers have

reported conflicting results regarding the performance of online students. Some experts

have reported no significant differences in levels of performance, whereas others have

reported similar levels of online student achievement compared to campus-based

courses (Hislop, 2000). Schutte (1996) reported that student performance was higher

in an online course than in a traditional course. Olson and Wisher (2002) reviewed 47

online course evaluation reports published between 1996 and 2002 and suggested that

online instruction ‘appears to be an improvement over conventional classroom instruc-

tion’ (p. 11). Undoubtedly, this topic warrants further investigation before we can draw

conclusions about the effectiveness of online learning.

Quality is important in the delivery of all courses and programs, regardless of the

environment in which they are delivered. Two of the five elements in the Sloan

Consortium’s quality framework for online education are student satisfaction and

faculty satisfaction. These pillars of quality (Sloan Consortium, 2002) need to be

assessed on an ongoing basis.

Student satisfaction

Student satisfaction is defined as the student’s perceived value of his or her educa-

tional experiences at an educational institution (Astin, 1993). ‘Significant differences

still exist in the way students perceive their online experiences during learning’

(Muilenburg & Berge, 2005, p. 29). Perceptions about their learning experiences can

influence students in their decision to continue with the course (Carr, 2000) and

impact levels of satisfaction with overall online learning experiences (Kenny, 2003).

Student satisfaction, according to the American Distance Education Consortium

(ADEC, n.d.), ‘is the most important key to continue learning’ (¶5).

Distance Education 105

Several elements influence student satisfaction in the online environment.

Bolliger and Martindale (2004) identified three key factors central to online student

satisfaction: the instructor, technology, and interactivity. Other components are

communication with all other course constituents, course management issues, and

course websites or course management systems used. Additionally, students’ percep-

tions of task value and self-efficacy, social ability, quality of system, and multimedia

instruction have been identified as important constructs (Liaw, 2008; Lin, Lin, &

Laffey, 2008).

However, Muilenburg and Berge (2005) have reported several barriers to online

learning encountered by students. These barriers include administrative issues, social

interaction, academic and technical skills, motivation, time, limited access to

resources, and technical difficulties. Other barriers include unfamiliar roles and

responsibilities, delays in feedback from instructors, limited technical assistance, high

degrees of technology dependence, and low student performance and satisfaction

(Navarro, 2000; Simonson et al., 2009).

Students also need to be confident that they can be successful in the online learning

environment (Sloan Consortium, 2002). Student satisfaction is linked to the students’

performance, and student satisfaction is an important element in the investigation of

faculty satisfaction. Hartman, Dziuban, and Moskal (2000) have suggested that

faculty satisfaction and student learning are highly correlated.

Faculty satisfaction

Faculty satisfaction is a complex issue that is difficult to describe and predict.

Included constructs are triggers described as changes in lifestyle (e.g., transfer to a

new position or change in rank) and mediators such as demographics, motivators, and

conditions in the environment that influence other variables (Hagedorn, 2000).

Faculty satisfaction in the context of this study is defined as the perception that

teaching in the online environment is ‘effective and professionally beneficial’ (ADEC,

n.d., ¶10).

Because faculty are instrumental in the success of distance education programs,

levels of faculty satisfaction are one measure for the assessment of program effective-

ness (Lock Haven University, 2004). The National Education Association (NEA,

2000) found that approximately 75% of faculty surveyed felt positively about distance

education. Hartman et al. (2000) reported that 83.4% of instructors were satisfied with

teaching fully online courses, and 93.6% of respondents were willing to continue to

teach online. Conceição (2006) pointed out that most participants in a phenomenolog-

ical study indicated online teaching ‘gave them some type of satisfaction’ (p. 40).

Fredericksen, Pickett, Shea, Pelz, and Swan (2000) reported a high level of faculty

satisfaction in a large online network in postsecondary education.

Factors contributing to faculty satisfaction

Several motivating factors in the participation of faculty in distance education and

barriers to faculty adoption have been identified in the literature (ADEC, n.d.; Betts,

1998; Bower, 2001; Durette, 2000; Fredericksen et al., 2000; Hartman et al., 2000;

NEA, 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2001; Panda & Mishra, 2007; Passmore, 2000; Rockwell,

Schauer, Fritz, & Marx, 1999; Simonson et al., 2009; Sloan Consortium, 2006). These

factors have the potential to influence faculty satisfaction in the online environment

Several elements influence student satisfaction in the online environment.

Bolliger and Martindale (2004) identified three key factors central to online student

satisfaction: the instructor, technology, and interactivity. Other components are

communication with all other course constituents, course management issues, and

course websites or course management systems used. Additionally, students’ percep-

tions of task value and self-efficacy, social ability, quality of system, and multimedia

instruction have been identified as important constructs (Liaw, 2008; Lin, Lin, &

Laffey, 2008).

However, Muilenburg and Berge (2005) have reported several barriers to online

learning encountered by students. These barriers include administrative issues, social

interaction, academic and technical skills, motivation, time, limited access to

resources, and technical difficulties. Other barriers include unfamiliar roles and

responsibilities, delays in feedback from instructors, limited technical assistance, high

degrees of technology dependence, and low student performance and satisfaction

(Navarro, 2000; Simonson et al., 2009).

Students also need to be confident that they can be successful in the online learning

environment (Sloan Consortium, 2002). Student satisfaction is linked to the students’

performance, and student satisfaction is an important element in the investigation of

faculty satisfaction. Hartman, Dziuban, and Moskal (2000) have suggested that

faculty satisfaction and student learning are highly correlated.

Faculty satisfaction

Faculty satisfaction is a complex issue that is difficult to describe and predict.

Included constructs are triggers described as changes in lifestyle (e.g., transfer to a

new position or change in rank) and mediators such as demographics, motivators, and

conditions in the environment that influence other variables (Hagedorn, 2000).

Faculty satisfaction in the context of this study is defined as the perception that

teaching in the online environment is ‘effective and professionally beneficial’ (ADEC,

n.d., ¶10).

Because faculty are instrumental in the success of distance education programs,

levels of faculty satisfaction are one measure for the assessment of program effective-

ness (Lock Haven University, 2004). The National Education Association (NEA,

2000) found that approximately 75% of faculty surveyed felt positively about distance

education. Hartman et al. (2000) reported that 83.4% of instructors were satisfied with

teaching fully online courses, and 93.6% of respondents were willing to continue to

teach online. Conceição (2006) pointed out that most participants in a phenomenolog-

ical study indicated online teaching ‘gave them some type of satisfaction’ (p. 40).

Fredericksen, Pickett, Shea, Pelz, and Swan (2000) reported a high level of faculty

satisfaction in a large online network in postsecondary education.

Factors contributing to faculty satisfaction

Several motivating factors in the participation of faculty in distance education and

barriers to faculty adoption have been identified in the literature (ADEC, n.d.; Betts,

1998; Bower, 2001; Durette, 2000; Fredericksen et al., 2000; Hartman et al., 2000;

NEA, 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2001; Panda & Mishra, 2007; Passmore, 2000; Rockwell,

Schauer, Fritz, & Marx, 1999; Simonson et al., 2009; Sloan Consortium, 2006). These

factors have the potential to influence faculty satisfaction in the online environment

106 D.U. Bolliger and O. Wasilik

and can be categorized into three groups: (a) student-related, (b) instructor-related,

and (c) institution-related.

Student-related factors

One of the most often cited reasons of why faculty like to teach online is the fact that

online education affords access to higher education for a more diverse student popu-

lation (ADEC, n.d.; Betts, 1998; NEA, 2000; Rockwell et al., 1999; Sloan Consor-

tium, 2006). Another motivating factor is that faculty perceive the online environment

as an opportunity for students to engage in highly interactive communication with the

instructor and their peers (ADEC, n.d.; Fredericksen et al., 2000; Hartman et al., 2000;

Sloan Consortium, 2006). However, some faculty members express concern about

limited interaction with students (Bower, 2001) in an environment where they never

meet the students face-to-face. Researchers have established a positive correlation

between faculty satisfaction and student performance. Generally, the level of faculty

satisfaction is higher in courses where student performance is better (Fredericksen

et al., 2000; Hartman et al., 2000).

Instructor-related factors

Faculty satisfaction is positively influenced when faculty believe that they can promote

positive student outcomes (Sloan Consortium, 2006). Other intrinsic motivators

include self-gratification (Rockwell et al., 1999), intellectual challenge, and an interest

in using technology (Panda & Mishra, 2007). This environment provides faculty with

professional development opportunities (ADEC, n.d.; Betts, 1998; Bower, 2001;

Hartman et al., 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2001; Panda & Mishra, 2007; Rockwell et al.,

1999; Simonson et al., 2009; Sloan Consortium, 2006) and research and collaboration

opportunities with colleagues (ADEC, n.d.; Sloan Consortium, 2006).

Faculty members are satisfied when they are recognized for the work that they are

doing (Rockwell et al., 1999; Sloan Consortium, 2006). However, faculty expect

reliable infrastructure and technology (ADEC, n.d.; Betts, 1998; Fredericksen et al.,

2000; Hartman et al., 2000; Panda & Mishra, 2007; Simonson et al., 2009; Sloan

Consortium, 2006). When faculty experience technology difficulties or do not have

access to adequate technology and tools, their satisfaction is likely to decrease.

Institution-related factors

Faculty satisfaction is generally high when the institution values online teaching and

has policies in place that support the faculty. Workload issues are the greatest barrier

in the adoption of online education because educators perceive the workload to be

higher than compared to that of traditional courses. At least initially, faculty expect to

spend more time on online course development and online teaching. Faculty are more

satisfied when the institution provides release time for course development and

recognizes that online teaching is time consuming (ADEC, n.d.; Betts, 1998; Bower,

2001; Hartman et al., 2000; Howell, Saba, Lindsay, & Williams, 2004; Passmore,

2000; Rockwell et al., 1999; Simonson et al., 2009; Sloan Consortium, 2006).

Two other major concerns are adequate compensation (Bower, 2001; Simonson

et al., 2009; Sloan Consortium, 2006) and an equitable reward system for promotion

and can be categorized into three groups: (a) student-related, (b) instructor-related,

and (c) institution-related.

Student-related factors

One of the most often cited reasons of why faculty like to teach online is the fact that

online education affords access to higher education for a more diverse student popu-

lation (ADEC, n.d.; Betts, 1998; NEA, 2000; Rockwell et al., 1999; Sloan Consor-

tium, 2006). Another motivating factor is that faculty perceive the online environment

as an opportunity for students to engage in highly interactive communication with the

instructor and their peers (ADEC, n.d.; Fredericksen et al., 2000; Hartman et al., 2000;

Sloan Consortium, 2006). However, some faculty members express concern about

limited interaction with students (Bower, 2001) in an environment where they never

meet the students face-to-face. Researchers have established a positive correlation

between faculty satisfaction and student performance. Generally, the level of faculty

satisfaction is higher in courses where student performance is better (Fredericksen

et al., 2000; Hartman et al., 2000).

Instructor-related factors

Faculty satisfaction is positively influenced when faculty believe that they can promote

positive student outcomes (Sloan Consortium, 2006). Other intrinsic motivators

include self-gratification (Rockwell et al., 1999), intellectual challenge, and an interest

in using technology (Panda & Mishra, 2007). This environment provides faculty with

professional development opportunities (ADEC, n.d.; Betts, 1998; Bower, 2001;

Hartman et al., 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2001; Panda & Mishra, 2007; Rockwell et al.,

1999; Simonson et al., 2009; Sloan Consortium, 2006) and research and collaboration

opportunities with colleagues (ADEC, n.d.; Sloan Consortium, 2006).

Faculty members are satisfied when they are recognized for the work that they are

doing (Rockwell et al., 1999; Sloan Consortium, 2006). However, faculty expect

reliable infrastructure and technology (ADEC, n.d.; Betts, 1998; Fredericksen et al.,

2000; Hartman et al., 2000; Panda & Mishra, 2007; Simonson et al., 2009; Sloan

Consortium, 2006). When faculty experience technology difficulties or do not have

access to adequate technology and tools, their satisfaction is likely to decrease.

Institution-related factors

Faculty satisfaction is generally high when the institution values online teaching and

has policies in place that support the faculty. Workload issues are the greatest barrier

in the adoption of online education because educators perceive the workload to be

higher than compared to that of traditional courses. At least initially, faculty expect to

spend more time on online course development and online teaching. Faculty are more

satisfied when the institution provides release time for course development and

recognizes that online teaching is time consuming (ADEC, n.d.; Betts, 1998; Bower,

2001; Hartman et al., 2000; Howell, Saba, Lindsay, & Williams, 2004; Passmore,

2000; Rockwell et al., 1999; Simonson et al., 2009; Sloan Consortium, 2006).

Two other major concerns are adequate compensation (Bower, 2001; Simonson

et al., 2009; Sloan Consortium, 2006) and an equitable reward system for promotion

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Distance Education 107

and tenure (ADEC, n.d.; Bower, 2001; Hartman et al., 2000; Passmore, 2000; Simonson

et al., 2009; Sloan Consortium, 2006). Policies that clarify intellectual property issues

(Durette, 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2001; Passmore, 2000; Simonson et al., 2009; Sloan

Consortium, 2006) need to be in place. Faculty are also concerned about the quality of

courses (Betts, 1998; Bower, 2001) because the perception is that student satisfaction

as expressed in course evaluations tends to be lower than that in traditional courses.

The purpose of this study was twofold. First, researchers aimed to identify and

confirm factors influencing faculty satisfaction in the online environment. Second,

they desired to develop a quantitative self-report measure of perceived faculty

satisfaction in the online environment.

Methodology

Sample

The sample consisted of the entire population of online instructors (122 individuals)

who taught a course during fall 2007 or spring 2008 at a public research university.

The university has an annual student enrollment of approximately 11,600 and is the

only provider of baccalaureate and graduate degrees in the state. Because the univer-

sity serves many rural areas, it has been engaged in providing distance learning and

outreach services since 1984.

Of 102 (82%) individuals who responded, the majority were female (59.8%) and

native English speakers (94.1%). Their ages ranged from 24 to 69 years (M = 50) and

their online teaching experience ranged from 0 to 20 years (M = 4.67).

Data collection

All online instructors at the institution were contacted via email and invited to partic-

ipate in the study. They were provided with information about the study and a link to

the online faculty satisfaction survey (OFSS) that was an integral part of the university’s

course management system. Participants needed to log in to a secure server site in order

to complete the questionnaire, which took approximately 10 minutes; however, all

responses were anonymous and confidential. As an incentive, participants were able

to register for the drawing of a gift certificate for the university bookstore after they

completed the questionnaire by providing their contact information. After two weeks,

a follow-up email was sent by the survey system to nonrespondents. Then the self-

reported data were analyzed to confirm the factors pertaining to faculty satisfaction.

Instrument

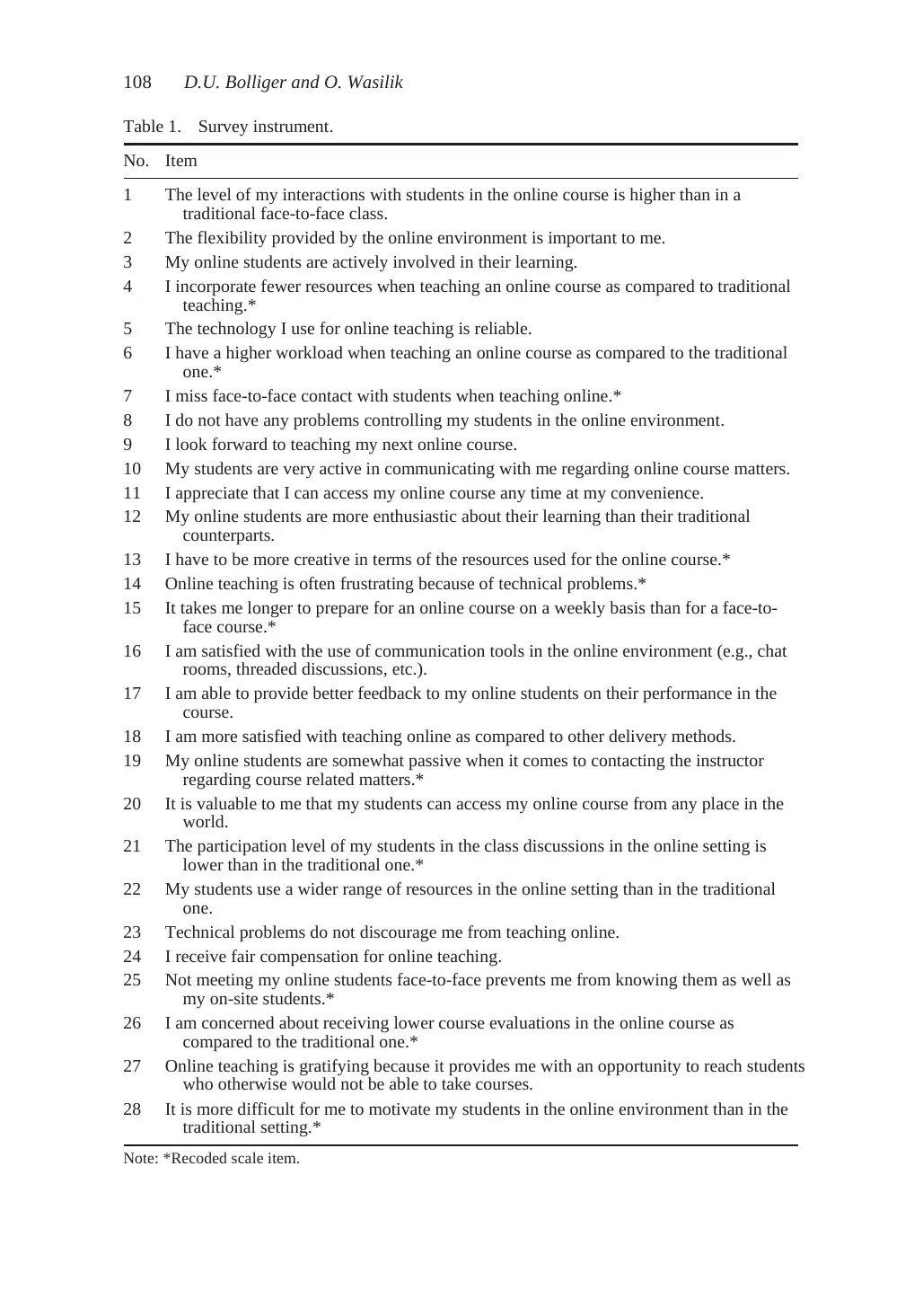

The OFSS has a total of 36 questions including 28 questions with a 4-point Likert scale,

ranging from 1 strongly disagree to 4 strongly agree (see Table 1). The questions were

based on the results of the literature review, which included articles pertaining to chal-

lenges of and barriers to faculty teaching online and faculty satisfaction. Once elements

were identified, researchers focused on issues that directly impact teaching in the

online environment. Items were developed for each of the three subscales: (a) student-

related issues, (b) instructor-related issues, and (c) institutional-related issues.

Respectively 14, 8, and 4 items were created based on the constructs derived from the

literature. Scale items were compared to other instruments published in the literature

and tenure (ADEC, n.d.; Bower, 2001; Hartman et al., 2000; Passmore, 2000; Simonson

et al., 2009; Sloan Consortium, 2006). Policies that clarify intellectual property issues

(Durette, 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2001; Passmore, 2000; Simonson et al., 2009; Sloan

Consortium, 2006) need to be in place. Faculty are also concerned about the quality of

courses (Betts, 1998; Bower, 2001) because the perception is that student satisfaction

as expressed in course evaluations tends to be lower than that in traditional courses.

The purpose of this study was twofold. First, researchers aimed to identify and

confirm factors influencing faculty satisfaction in the online environment. Second,

they desired to develop a quantitative self-report measure of perceived faculty

satisfaction in the online environment.

Methodology

Sample

The sample consisted of the entire population of online instructors (122 individuals)

who taught a course during fall 2007 or spring 2008 at a public research university.

The university has an annual student enrollment of approximately 11,600 and is the

only provider of baccalaureate and graduate degrees in the state. Because the univer-

sity serves many rural areas, it has been engaged in providing distance learning and

outreach services since 1984.

Of 102 (82%) individuals who responded, the majority were female (59.8%) and

native English speakers (94.1%). Their ages ranged from 24 to 69 years (M = 50) and

their online teaching experience ranged from 0 to 20 years (M = 4.67).

Data collection

All online instructors at the institution were contacted via email and invited to partic-

ipate in the study. They were provided with information about the study and a link to

the online faculty satisfaction survey (OFSS) that was an integral part of the university’s

course management system. Participants needed to log in to a secure server site in order

to complete the questionnaire, which took approximately 10 minutes; however, all

responses were anonymous and confidential. As an incentive, participants were able

to register for the drawing of a gift certificate for the university bookstore after they

completed the questionnaire by providing their contact information. After two weeks,

a follow-up email was sent by the survey system to nonrespondents. Then the self-

reported data were analyzed to confirm the factors pertaining to faculty satisfaction.

Instrument

The OFSS has a total of 36 questions including 28 questions with a 4-point Likert scale,

ranging from 1 strongly disagree to 4 strongly agree (see Table 1). The questions were

based on the results of the literature review, which included articles pertaining to chal-

lenges of and barriers to faculty teaching online and faculty satisfaction. Once elements

were identified, researchers focused on issues that directly impact teaching in the

online environment. Items were developed for each of the three subscales: (a) student-

related issues, (b) instructor-related issues, and (c) institutional-related issues.

Respectively 14, 8, and 4 items were created based on the constructs derived from the

literature. Scale items were compared to other instruments published in the literature

108 D.U. Bolliger and O. Wasilik

Table 1. Survey instrument.

No. Item

1 The level of my interactions with students in the online course is higher than in a

traditional face-to-face class.

2 The flexibility provided by the online environment is important to me.

3 My online students are actively involved in their learning.

4 I incorporate fewer resources when teaching an online course as compared to traditional

teaching.*

5 The technology I use for online teaching is reliable.

6 I have a higher workload when teaching an online course as compared to the traditional

one.*

7 I miss face-to-face contact with students when teaching online.*

8 I do not have any problems controlling my students in the online environment.

9 I look forward to teaching my next online course.

10 My students are very active in communicating with me regarding online course matters.

11 I appreciate that I can access my online course any time at my convenience.

12 My online students are more enthusiastic about their learning than their traditional

counterparts.

13 I have to be more creative in terms of the resources used for the online course.*

14 Online teaching is often frustrating because of technical problems.*

15 It takes me longer to prepare for an online course on a weekly basis than for a face-to-

face course.*

16 I am satisfied with the use of communication tools in the online environment (e.g., chat

rooms, threaded discussions, etc.).

17 I am able to provide better feedback to my online students on their performance in the

course.

18 I am more satisfied with teaching online as compared to other delivery methods.

19 My online students are somewhat passive when it comes to contacting the instructor

regarding course related matters.*

20 It is valuable to me that my students can access my online course from any place in the

world.

21 The participation level of my students in the class discussions in the online setting is

lower than in the traditional one.*

22 My students use a wider range of resources in the online setting than in the traditional

one.

23 Technical problems do not discourage me from teaching online.

24 I receive fair compensation for online teaching.

25 Not meeting my online students face-to-face prevents me from knowing them as well as

my on-site students.*

26 I am concerned about receiving lower course evaluations in the online course as

compared to the traditional one.*

27 Online teaching is gratifying because it provides me with an opportunity to reach students

who otherwise would not be able to take courses.

28 It is more difficult for me to motivate my students in the online environment than in the

traditional setting.*

Note: *Recoded scale item.

Table 1. Survey instrument.

No. Item

1 The level of my interactions with students in the online course is higher than in a

traditional face-to-face class.

2 The flexibility provided by the online environment is important to me.

3 My online students are actively involved in their learning.

4 I incorporate fewer resources when teaching an online course as compared to traditional

teaching.*

5 The technology I use for online teaching is reliable.

6 I have a higher workload when teaching an online course as compared to the traditional

one.*

7 I miss face-to-face contact with students when teaching online.*

8 I do not have any problems controlling my students in the online environment.

9 I look forward to teaching my next online course.

10 My students are very active in communicating with me regarding online course matters.

11 I appreciate that I can access my online course any time at my convenience.

12 My online students are more enthusiastic about their learning than their traditional

counterparts.

13 I have to be more creative in terms of the resources used for the online course.*

14 Online teaching is often frustrating because of technical problems.*

15 It takes me longer to prepare for an online course on a weekly basis than for a face-to-

face course.*

16 I am satisfied with the use of communication tools in the online environment (e.g., chat

rooms, threaded discussions, etc.).

17 I am able to provide better feedback to my online students on their performance in the

course.

18 I am more satisfied with teaching online as compared to other delivery methods.

19 My online students are somewhat passive when it comes to contacting the instructor

regarding course related matters.*

20 It is valuable to me that my students can access my online course from any place in the

world.

21 The participation level of my students in the class discussions in the online setting is

lower than in the traditional one.*

22 My students use a wider range of resources in the online setting than in the traditional

one.

23 Technical problems do not discourage me from teaching online.

24 I receive fair compensation for online teaching.

25 Not meeting my online students face-to-face prevents me from knowing them as well as

my on-site students.*

26 I am concerned about receiving lower course evaluations in the online course as

compared to the traditional one.*

27 Online teaching is gratifying because it provides me with an opportunity to reach students

who otherwise would not be able to take courses.

28 It is more difficult for me to motivate my students in the online environment than in the

traditional setting.*

Note: *Recoded scale item.

Distance Education 109

pertaining to satisfaction in the online environment. Additionally, four open-ended and

four demographic questions were created for inclusion in the questionnaire. The first

version of the survey was examined by a content and psychometric expert, who

suggested several modifications that were implemented.

The instrument was administered to 25 individuals in a preservice teacher course

in order to determine whether the items were clear and concise. One question was

slightly modified before the questionnaire was made available in the online course

management system. In order to determine the internal reliability of the questionnaire,

researchers performed a reliability analysis with the use of Cronbach’s alpha after the

data collection phase.

Statistical assumptions

Sample size and missing data

Initially, the sample size in this study was 102 participants. One case in the data set

had one-third of data missing and was deleted. Several other cases contained missing

data; these cases were estimated by using mean substitution. After the initial data

estimation, this assumption was considered met.

Outliers

Another assumption of the factor analysis is that there are no outliers. An examination

of z scores revealed seven potential outliers, which were confirmed by a visual exam-

ination of several scatter plots. Outliers within the range of z ±3.00 were deleted from

the data set. After these outliers were deleted, this assumption was met.

Linearity

In order to examine for linearity, several bivariate scatter plots were generated and

examined. Because the items on the instrument are on a 4-point Likert scale, all of the

scatter plots revealed abnormalities between the variables. This was an acceptable

violation of the assumption and it did not adversely affect the results of the study.

Multicollinearity and singularity

In order to determine if multicollinearity existed, the Pearson correlation coefficients

were examined in a correlation matrix. The three highest correlation coefficients in the

matrix were between items 10 and 19 (0.64), items 21 and 28 (0.63), and items 2 and 11

(0.60). The collinearity diagnostic showed that the highest variance proportion was 0.65.

Therefore, no multicollinearity existed between any of the dependent variables. Each of

the dependent variables is an independent measure, therefore ruling out singularity.

Results

Descriptive statistics

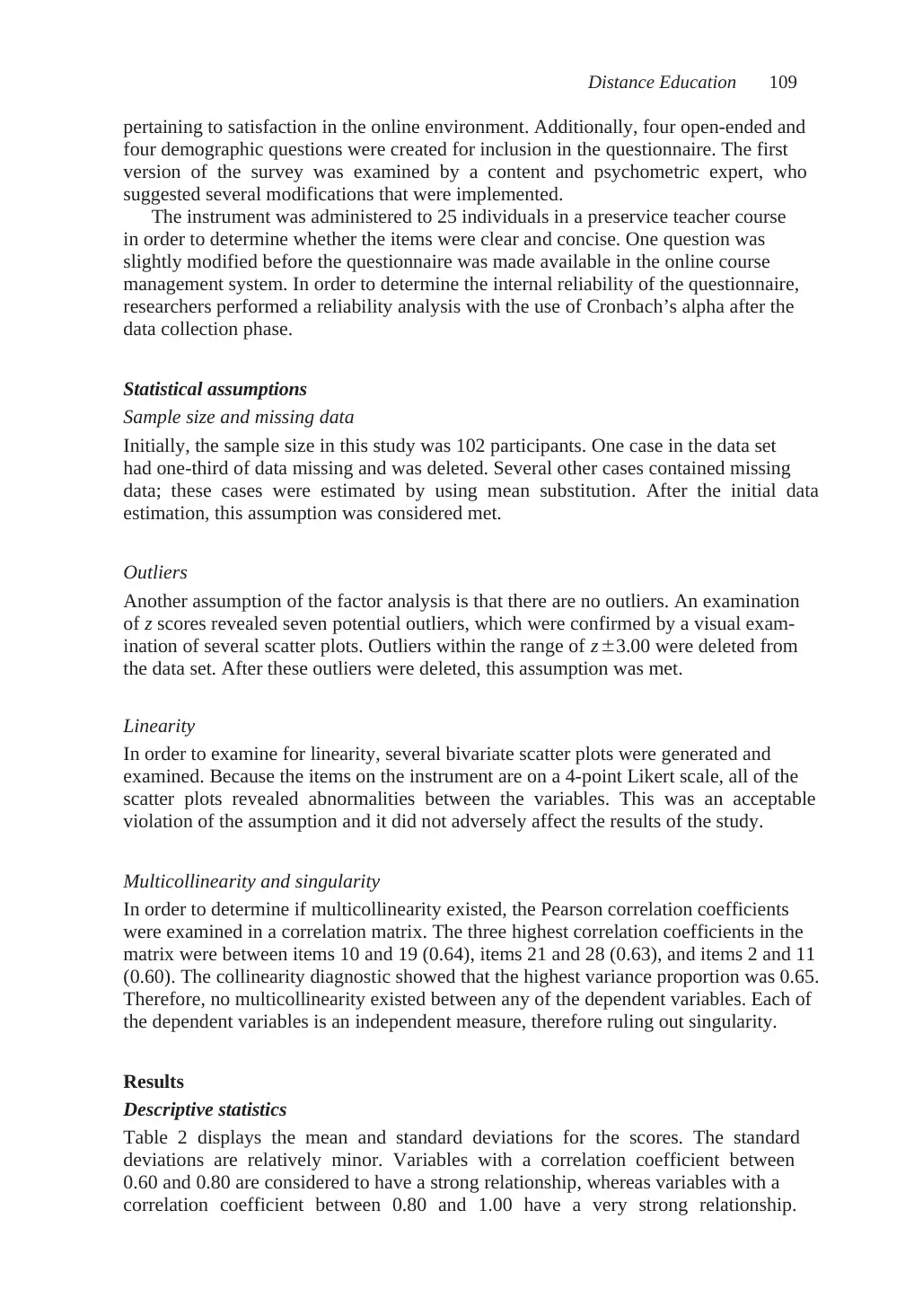

Table 2 displays the mean and standard deviations for the scores. The standard

deviations are relatively minor. Variables with a correlation coefficient between

0.60 and 0.80 are considered to have a strong relationship, whereas variables with a

correlation coefficient between 0.80 and 1.00 have a very strong relationship.

pertaining to satisfaction in the online environment. Additionally, four open-ended and

four demographic questions were created for inclusion in the questionnaire. The first

version of the survey was examined by a content and psychometric expert, who

suggested several modifications that were implemented.

The instrument was administered to 25 individuals in a preservice teacher course

in order to determine whether the items were clear and concise. One question was

slightly modified before the questionnaire was made available in the online course

management system. In order to determine the internal reliability of the questionnaire,

researchers performed a reliability analysis with the use of Cronbach’s alpha after the

data collection phase.

Statistical assumptions

Sample size and missing data

Initially, the sample size in this study was 102 participants. One case in the data set

had one-third of data missing and was deleted. Several other cases contained missing

data; these cases were estimated by using mean substitution. After the initial data

estimation, this assumption was considered met.

Outliers

Another assumption of the factor analysis is that there are no outliers. An examination

of z scores revealed seven potential outliers, which were confirmed by a visual exam-

ination of several scatter plots. Outliers within the range of z ±3.00 were deleted from

the data set. After these outliers were deleted, this assumption was met.

Linearity

In order to examine for linearity, several bivariate scatter plots were generated and

examined. Because the items on the instrument are on a 4-point Likert scale, all of the

scatter plots revealed abnormalities between the variables. This was an acceptable

violation of the assumption and it did not adversely affect the results of the study.

Multicollinearity and singularity

In order to determine if multicollinearity existed, the Pearson correlation coefficients

were examined in a correlation matrix. The three highest correlation coefficients in the

matrix were between items 10 and 19 (0.64), items 21 and 28 (0.63), and items 2 and 11

(0.60). The collinearity diagnostic showed that the highest variance proportion was 0.65.

Therefore, no multicollinearity existed between any of the dependent variables. Each of

the dependent variables is an independent measure, therefore ruling out singularity.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 displays the mean and standard deviations for the scores. The standard

deviations are relatively minor. Variables with a correlation coefficient between

0.60 and 0.80 are considered to have a strong relationship, whereas variables with a

correlation coefficient between 0.80 and 1.00 have a very strong relationship.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

110 D.U. Bolliger and O. Wasilik

Only three relationships were at or higher than 0.60 and no relationships were

above 0.80.

The OFSS includes two items that are considered general satisfaction questions.

Here instructors indicated their levels of agreement or disagreement with the state-

ments ‘I look forward to teaching my next online course’ (item 9) and ‘I am more

satisfied with teaching online as compared to other delivery methods’ (item 18). The

means for these items were 3.24 (SD = 0.72) and 2.29 (SD = 1.05), respectively.

Table 2. Means and standard deviation of scores.

Student subscale

Item M SD

Item 1 2.33 0.89

Item 2 3.53 0.60

Item 3 3.31 0.53

Item 7 2.15 0.80

Item 10 3.08 0.61

Item 11 3.65 0.58

Item 12 2.35 0.92

Item 16 3.14 0.52

Item 17 2.58 0.93

Item 19 2.93 0.73

Item 20 3.48 0.52

Item 21 3.16 0.69

Item 25 2.41 0.81

Item 27 3.33 0.64

Item 28 2.86 0.69

Instructor subscale

M SD

Item 4 3.10 0.81

Item 5 3.32 0.60

Item 8 2.81 1.01

Item 13 2.07 0.66

Item 14 3.04 0.70

Item 22 2.72 0.72

Item 23 3.19 0.76

Institution subscale

M SD

Item 6 2.15 0.77

Item 15 2.54 0.74

Item 24 2.81 0.69

Item 26 2.79 0.75

Only three relationships were at or higher than 0.60 and no relationships were

above 0.80.

The OFSS includes two items that are considered general satisfaction questions.

Here instructors indicated their levels of agreement or disagreement with the state-

ments ‘I look forward to teaching my next online course’ (item 9) and ‘I am more

satisfied with teaching online as compared to other delivery methods’ (item 18). The

means for these items were 3.24 (SD = 0.72) and 2.29 (SD = 1.05), respectively.

Table 2. Means and standard deviation of scores.

Student subscale

Item M SD

Item 1 2.33 0.89

Item 2 3.53 0.60

Item 3 3.31 0.53

Item 7 2.15 0.80

Item 10 3.08 0.61

Item 11 3.65 0.58

Item 12 2.35 0.92

Item 16 3.14 0.52

Item 17 2.58 0.93

Item 19 2.93 0.73

Item 20 3.48 0.52

Item 21 3.16 0.69

Item 25 2.41 0.81

Item 27 3.33 0.64

Item 28 2.86 0.69

Instructor subscale

M SD

Item 4 3.10 0.81

Item 5 3.32 0.60

Item 8 2.81 1.01

Item 13 2.07 0.66

Item 14 3.04 0.70

Item 22 2.72 0.72

Item 23 3.19 0.76

Institution subscale

M SD

Item 6 2.15 0.77

Item 15 2.54 0.74

Item 24 2.81 0.69

Item 26 2.79 0.75

Distance Education 111

Factor analysis

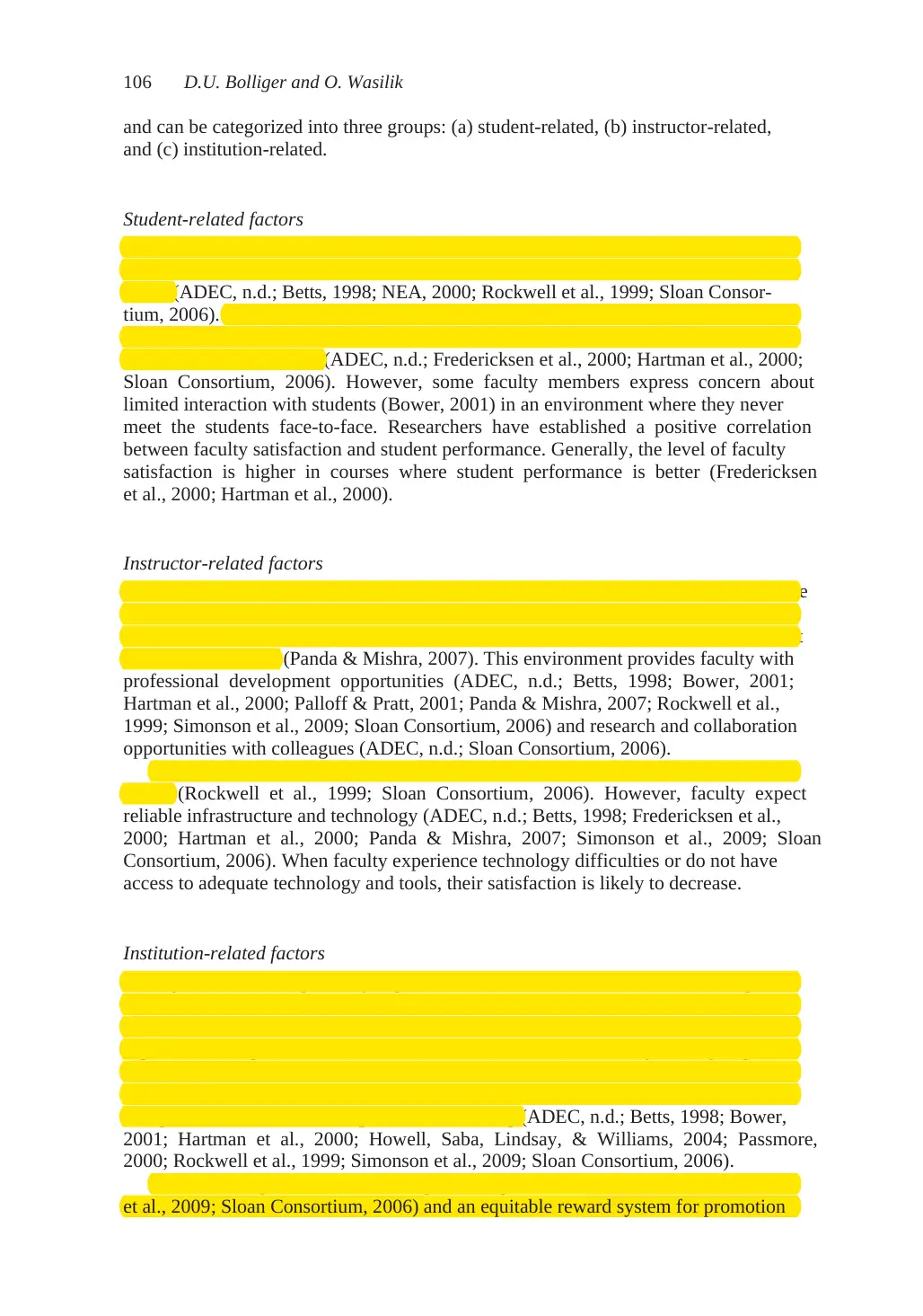

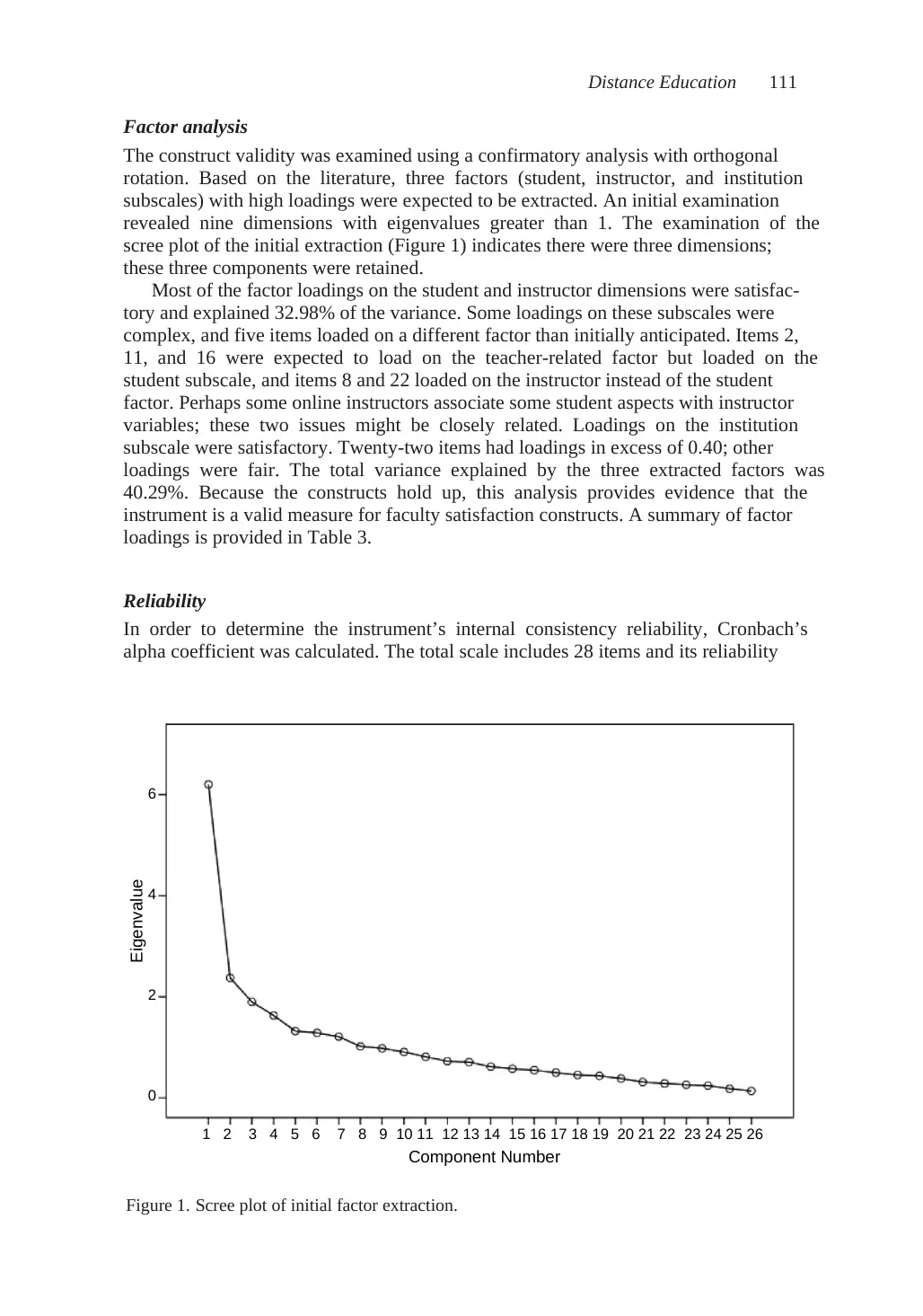

The construct validity was examined using a confirmatory analysis with orthogonal

rotation. Based on the literature, three factors (student, instructor, and institution

subscales) with high loadings were expected to be extracted. An initial examination

revealed nine dimensions with eigenvalues greater than 1. The examination of the

scree plot of the initial extraction (Figure 1) indicates there were three dimensions;

these three components were retained.

Figure 1.−Scree plot of initial factor extraction.

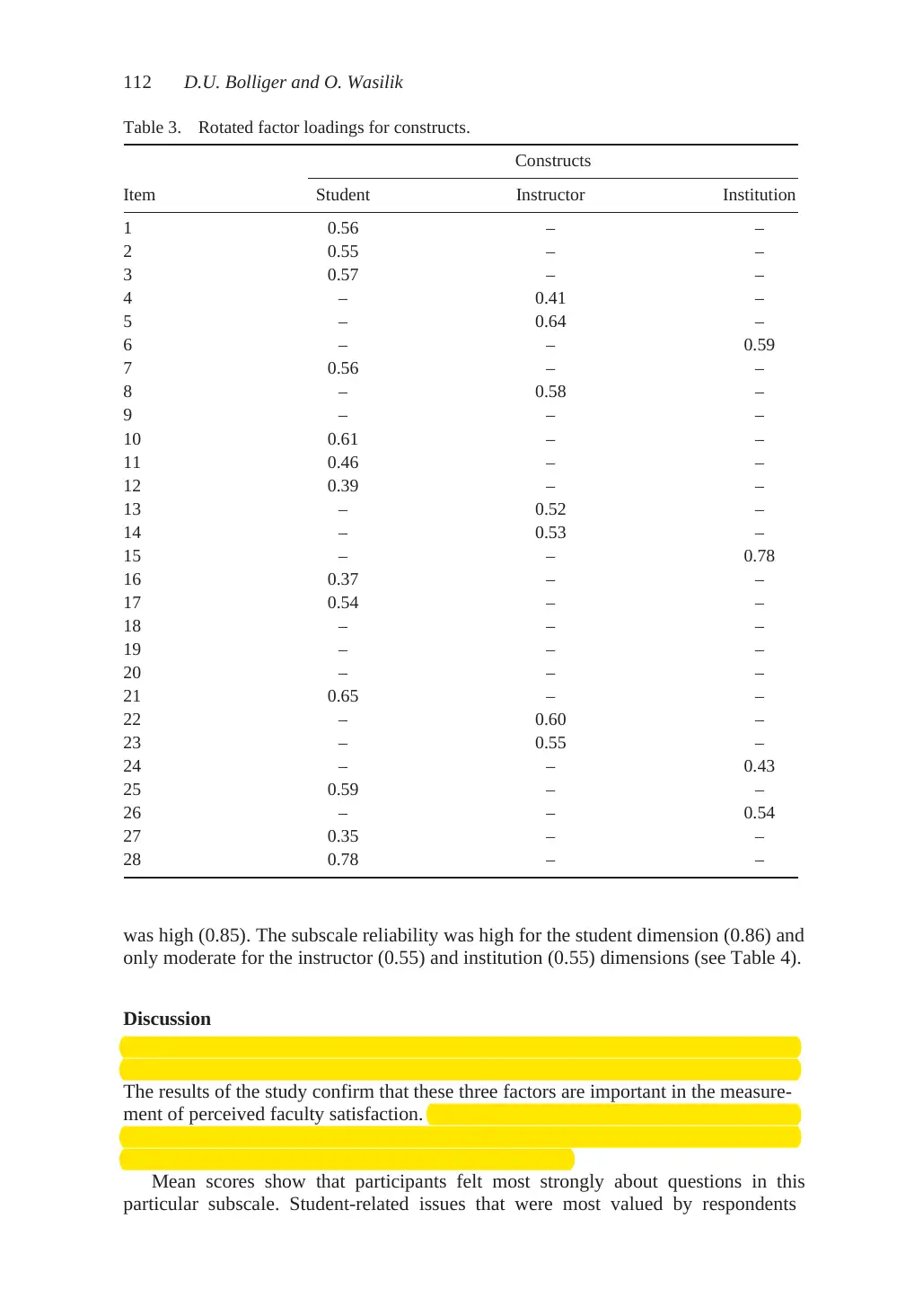

Most of the factor loadings on the student and instructor dimensions were satisfac-

tory and explained 32.98% of the variance. Some loadings on these subscales were

complex, and five items loaded on a different factor than initially anticipated. Items 2,

11, and 16 were expected to load on the teacher-related factor but loaded on the

student subscale, and items 8 and 22 loaded on the instructor instead of the student

factor. Perhaps some online instructors associate some student aspects with instructor

variables; these two issues might be closely related. Loadings on the institution

subscale were satisfactory. Twenty-two items had loadings in excess of 0.40; other

loadings were fair. The total variance explained by the three extracted factors was

40.29%. Because the constructs hold up, this analysis provides evidence that the

instrument is a valid measure for faculty satisfaction constructs. A summary of factor

loadings is provided in Table 3.

Reliability

In order to determine the instrument’s internal consistency reliability, Cronbach’s

alpha coefficient was calculated. The total scale includes 28 items and its reliability

Component Number

Eigenvalue

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

0

2

4

6

Figure 1. Scree plot of initial factor extraction.

Factor analysis

The construct validity was examined using a confirmatory analysis with orthogonal

rotation. Based on the literature, three factors (student, instructor, and institution

subscales) with high loadings were expected to be extracted. An initial examination

revealed nine dimensions with eigenvalues greater than 1. The examination of the

scree plot of the initial extraction (Figure 1) indicates there were three dimensions;

these three components were retained.

Figure 1.−Scree plot of initial factor extraction.

Most of the factor loadings on the student and instructor dimensions were satisfac-

tory and explained 32.98% of the variance. Some loadings on these subscales were

complex, and five items loaded on a different factor than initially anticipated. Items 2,

11, and 16 were expected to load on the teacher-related factor but loaded on the

student subscale, and items 8 and 22 loaded on the instructor instead of the student

factor. Perhaps some online instructors associate some student aspects with instructor

variables; these two issues might be closely related. Loadings on the institution

subscale were satisfactory. Twenty-two items had loadings in excess of 0.40; other

loadings were fair. The total variance explained by the three extracted factors was

40.29%. Because the constructs hold up, this analysis provides evidence that the

instrument is a valid measure for faculty satisfaction constructs. A summary of factor

loadings is provided in Table 3.

Reliability

In order to determine the instrument’s internal consistency reliability, Cronbach’s

alpha coefficient was calculated. The total scale includes 28 items and its reliability

Component Number

Eigenvalue

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

0

2

4

6

Figure 1. Scree plot of initial factor extraction.

112 D.U. Bolliger and O. Wasilik

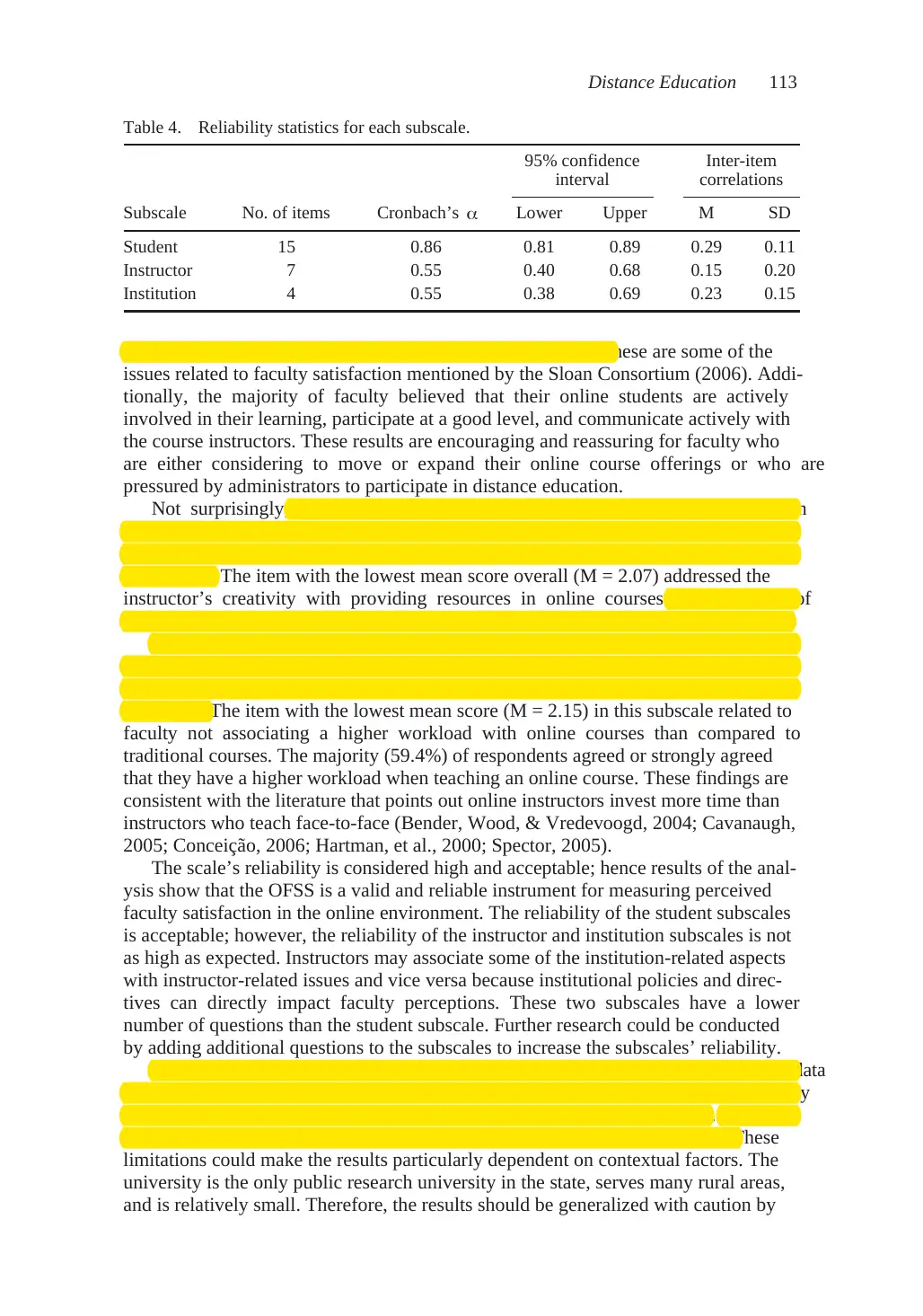

was high (0.85). The subscale reliability was high for the student dimension (0.86) and

only moderate for the instructor (0.55) and institution (0.55) dimensions (see Table 4).

Discussion

As previously mentioned, the literature consistently points out three elements impor-

tant to faculty who teach online courses: students, the instructor, and the institution.

The results of the study confirm that these three factors are important in the measure-

ment of perceived faculty satisfaction. The student factor is the most important factor

influencing satisfaction of online faculty, which is encouraging because it leads us to

believe that many online instructors are student centered.

Mean scores show that participants felt most strongly about questions in this

particular subscale. Student-related issues that were most valued by respondents

Table 3. Rotated factor loadings for constructs.

Constructs

Item Student Instructor Institution

1 0.56 – –

2 0.55 – –

3 0.57 – –

4 – 0.41 –

5 – 0.64 –

6 – – 0.59

7 0.56 – –

8 – 0.58 –

9 – – –

10 0.61 – –

11 0.46 – –

12 0.39 – –

13 – 0.52 –

14 – 0.53 –

15 – – 0.78

16 0.37 – –

17 0.54 – –

18 – – –

19 – – –

20 – – –

21 0.65 – –

22 – 0.60 –

23 – 0.55 –

24 – – 0.43

25 0.59 – –

26 – – 0.54

27 0.35 – –

28 0.78 – –

was high (0.85). The subscale reliability was high for the student dimension (0.86) and

only moderate for the instructor (0.55) and institution (0.55) dimensions (see Table 4).

Discussion

As previously mentioned, the literature consistently points out three elements impor-

tant to faculty who teach online courses: students, the instructor, and the institution.

The results of the study confirm that these three factors are important in the measure-

ment of perceived faculty satisfaction. The student factor is the most important factor

influencing satisfaction of online faculty, which is encouraging because it leads us to

believe that many online instructors are student centered.

Mean scores show that participants felt most strongly about questions in this

particular subscale. Student-related issues that were most valued by respondents

Table 3. Rotated factor loadings for constructs.

Constructs

Item Student Instructor Institution

1 0.56 – –

2 0.55 – –

3 0.57 – –

4 – 0.41 –

5 – 0.64 –

6 – – 0.59

7 0.56 – –

8 – 0.58 –

9 – – –

10 0.61 – –

11 0.46 – –

12 0.39 – –

13 – 0.52 –

14 – 0.53 –

15 – – 0.78

16 0.37 – –

17 0.54 – –

18 – – –

19 – – –

20 – – –

21 0.65 – –

22 – 0.60 –

23 – 0.55 –

24 – – 0.43

25 0.59 – –

26 – – 0.54

27 0.35 – –

28 0.78 – –

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Distance Education 113

include providing flexible and convenient access to courses. These are some of the

issues related to faculty satisfaction mentioned by the Sloan Consortium (2006). Addi-

tionally, the majority of faculty believed that their online students are actively

involved in their learning, participate at a good level, and communicate actively with

the course instructors. These results are encouraging and reassuring for faculty who

are either considering to move or expand their online course offerings or who are

pressured by administrators to participate in distance education.

Not surprisingly, instructor-related issues directly impact instructor satisfaction

but were less important than student-related issues. Questions that yielded the highest

mean scores pertained to using reliable technology and experiencing difficulties with

technology. The item with the lowest mean score overall (M = 2.07) addressed the

instructor’s creativity with providing resources in online courses. The majority of

respondents (77.4%) felt that they needed to be more creative in their online courses.

Institution-related issues are also important to online faculty as they can influence

satisfaction and motivation; however, none of the four subscale questions that pertain

to workload, compensation, preparation, and course evaluations yielded a mean score

above 3.0. The item with the lowest mean score (M = 2.15) in this subscale related to

faculty not associating a higher workload with online courses than compared to

traditional courses. The majority (59.4%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed

that they have a higher workload when teaching an online course. These findings are

consistent with the literature that points out online instructors invest more time than

instructors who teach face-to-face (Bender, Wood, & Vredevoogd, 2004; Cavanaugh,

2005; Conceição, 2006; Hartman, et al., 2000; Spector, 2005).

The scale’s reliability is considered high and acceptable; hence results of the anal-

ysis show that the OFSS is a valid and reliable instrument for measuring perceived

faculty satisfaction in the online environment. The reliability of the student subscales

is acceptable; however, the reliability of the instructor and institution subscales is not

as high as expected. Instructors may associate some of the institution-related aspects

with instructor-related issues and vice versa because institutional policies and direc-

tives can directly impact faculty perceptions. These two subscales have a lower

number of questions than the student subscale. Further research could be conducted

by adding additional questions to the subscales to increase the subscales’ reliability.

Some additional limitations of the study need to be pointed out. First, the data

analyzed in this study is self-reported data. Second, the sample is geographically

limited as only online instructors at one university participated in the study. Third, the

sample was relatively small even though the response rate (83.6%) was high. These

limitations could make the results particularly dependent on contextual factors. The

university is the only public research university in the state, serves many rural areas,

and is relatively small. Therefore, the results should be generalized with caution by

Table 4. Reliability statistics for each subscale.

95% confidence

interval

Inter-item

correlations

Subscale No. of items Cronbach’s α Lower Upper M SD

Student 15 0.86 0.81 0.89 0.29 0.11

Instructor 7 0.55 0.40 0.68 0.15 0.20

Institution 4 0.55 0.38 0.69 0.23 0.15

include providing flexible and convenient access to courses. These are some of the

issues related to faculty satisfaction mentioned by the Sloan Consortium (2006). Addi-

tionally, the majority of faculty believed that their online students are actively

involved in their learning, participate at a good level, and communicate actively with

the course instructors. These results are encouraging and reassuring for faculty who

are either considering to move or expand their online course offerings or who are

pressured by administrators to participate in distance education.

Not surprisingly, instructor-related issues directly impact instructor satisfaction

but were less important than student-related issues. Questions that yielded the highest

mean scores pertained to using reliable technology and experiencing difficulties with

technology. The item with the lowest mean score overall (M = 2.07) addressed the

instructor’s creativity with providing resources in online courses. The majority of

respondents (77.4%) felt that they needed to be more creative in their online courses.

Institution-related issues are also important to online faculty as they can influence

satisfaction and motivation; however, none of the four subscale questions that pertain

to workload, compensation, preparation, and course evaluations yielded a mean score

above 3.0. The item with the lowest mean score (M = 2.15) in this subscale related to

faculty not associating a higher workload with online courses than compared to

traditional courses. The majority (59.4%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed

that they have a higher workload when teaching an online course. These findings are

consistent with the literature that points out online instructors invest more time than

instructors who teach face-to-face (Bender, Wood, & Vredevoogd, 2004; Cavanaugh,

2005; Conceição, 2006; Hartman, et al., 2000; Spector, 2005).

The scale’s reliability is considered high and acceptable; hence results of the anal-

ysis show that the OFSS is a valid and reliable instrument for measuring perceived

faculty satisfaction in the online environment. The reliability of the student subscales

is acceptable; however, the reliability of the instructor and institution subscales is not

as high as expected. Instructors may associate some of the institution-related aspects

with instructor-related issues and vice versa because institutional policies and direc-

tives can directly impact faculty perceptions. These two subscales have a lower

number of questions than the student subscale. Further research could be conducted

by adding additional questions to the subscales to increase the subscales’ reliability.

Some additional limitations of the study need to be pointed out. First, the data

analyzed in this study is self-reported data. Second, the sample is geographically

limited as only online instructors at one university participated in the study. Third, the

sample was relatively small even though the response rate (83.6%) was high. These

limitations could make the results particularly dependent on contextual factors. The

university is the only public research university in the state, serves many rural areas,

and is relatively small. Therefore, the results should be generalized with caution by

Table 4. Reliability statistics for each subscale.

95% confidence

interval

Inter-item

correlations

Subscale No. of items Cronbach’s α Lower Upper M SD

Student 15 0.86 0.81 0.89 0.29 0.11

Instructor 7 0.55 0.40 0.68 0.15 0.20

Institution 4 0.55 0.38 0.69 0.23 0.15

114 D.U. Bolliger and O. Wasilik

the reader. One suggestion for future researchers is to include an institution with a

larger population of online faculty or to conduct a multi-institutional research study.

Conclusion

Just as we have to be concerned about appropriate levels of student satisfaction in the

online environment because it can impact student motivation and therefore student

success and completion rates, we need to continue to focus on faculty satisfaction

because it affects faculty motivation. Student and faculty satisfaction are two critical

pillars of quality (Sloan Consortium, 2002) in online education.

As mentioned, online teaching is a complex task that requires commitment from

faculty and can be time consuming and demanding. As online teaching has become an

expectation and an element of instructors’ regular teaching loads at many colleges and

universities, we should be concerned about faculty burnout. In a study conducted by

Hogan and McKnight (2007), online instructors in university settings experienced

average emotional burnout levels, high levels of depersonalization, and low levels of

personal accomplishment. These results should be of concern to administrators

because the success of online programs rests on the commitment of the faculty and

their willingness to continue the development and delivery of online courses (Betts,

1998). If positive student outcomes are highly correlated with faculty satisfaction as

suggested by Hartman et al. (2000), then administrators will need to pay close atten-

tion to levels of faculty satisfaction, because there may be an interaction effect.

The development, implementation, and maintenance of online courses and

programs is certainly not inexpensive. Boettcher (2004) estimated that an instructor

requires 10 hours to design and develop one hour of online instruction. This estimate

does not include the hours instructors spend on faculty training and development. It

will be costly to replace experienced instructors who choose to discontinue teaching

in the online environment.

Because faculty satisfaction is one of the five pillars of quality (Sloan Consortium,

2002), it is important and needs to be continuously assessed to assure quality online

educational experiences for faculty and students.

Notes on contributors

Doris U. Bolliger is assistant professor of instructional technology at the University of

Wyoming, USA. Her work focuses on distance learning with particular emphasis on commu-

nication, collaboration, interventions, and satisfaction in the online environment.

Oksana Wasilik is a doctoral candidate in education with a specialization in instructional

technology at the University of Wyoming (UW). She is a graduate assistant at the UW

Outreach School. Her research interests include online teaching, faculty satisfaction, and

aspects of instructional technology related to international faculty.

References

Allen, I.E., & Seaman, J. (2007, October). Online nation: Five years of growth in online

learning. Needham, MA: Sloan-C. Retrieved December 28, 2008, from http://www.sloan-

consortium.org/publications/survey/pdf/online_nation.pdf

American Distance Education Consortium (ADEC). (n.d.). Quality framework for online

education. Lincoln, NE: Author. Retrieved December 28, 2008, from http://

www.adec.edu/earmyu/SLOANC∼41.html

the reader. One suggestion for future researchers is to include an institution with a

larger population of online faculty or to conduct a multi-institutional research study.

Conclusion

Just as we have to be concerned about appropriate levels of student satisfaction in the

online environment because it can impact student motivation and therefore student

success and completion rates, we need to continue to focus on faculty satisfaction

because it affects faculty motivation. Student and faculty satisfaction are two critical

pillars of quality (Sloan Consortium, 2002) in online education.

As mentioned, online teaching is a complex task that requires commitment from

faculty and can be time consuming and demanding. As online teaching has become an

expectation and an element of instructors’ regular teaching loads at many colleges and

universities, we should be concerned about faculty burnout. In a study conducted by

Hogan and McKnight (2007), online instructors in university settings experienced

average emotional burnout levels, high levels of depersonalization, and low levels of

personal accomplishment. These results should be of concern to administrators

because the success of online programs rests on the commitment of the faculty and

their willingness to continue the development and delivery of online courses (Betts,

1998). If positive student outcomes are highly correlated with faculty satisfaction as

suggested by Hartman et al. (2000), then administrators will need to pay close atten-

tion to levels of faculty satisfaction, because there may be an interaction effect.

The development, implementation, and maintenance of online courses and

programs is certainly not inexpensive. Boettcher (2004) estimated that an instructor

requires 10 hours to design and develop one hour of online instruction. This estimate

does not include the hours instructors spend on faculty training and development. It

will be costly to replace experienced instructors who choose to discontinue teaching

in the online environment.

Because faculty satisfaction is one of the five pillars of quality (Sloan Consortium,

2002), it is important and needs to be continuously assessed to assure quality online

educational experiences for faculty and students.

Notes on contributors

Doris U. Bolliger is assistant professor of instructional technology at the University of

Wyoming, USA. Her work focuses on distance learning with particular emphasis on commu-

nication, collaboration, interventions, and satisfaction in the online environment.

Oksana Wasilik is a doctoral candidate in education with a specialization in instructional

technology at the University of Wyoming (UW). She is a graduate assistant at the UW

Outreach School. Her research interests include online teaching, faculty satisfaction, and

aspects of instructional technology related to international faculty.

References

Allen, I.E., & Seaman, J. (2007, October). Online nation: Five years of growth in online

learning. Needham, MA: Sloan-C. Retrieved December 28, 2008, from http://www.sloan-

consortium.org/publications/survey/pdf/online_nation.pdf

American Distance Education Consortium (ADEC). (n.d.). Quality framework for online

education. Lincoln, NE: Author. Retrieved December 28, 2008, from http://

www.adec.edu/earmyu/SLOANC∼41.html

Distance Education 115

Astin, A.W. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Baird, L.L. (1980). Importance of surveying student and faculty views. In L.L. Baird, R.T.

Hartnett, & Associates, Understanding student and faculty life: Using campus surveys to

improve academic decision making (pp. 1–67). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bender, D.M., Wood, B.J., & Vredevoogd, J.D. (2004). Teaching time: Distance education

versus classroom instruction. American Journal of Distance Education, 18(2), 103–114.

Betts, K.S. (1998). An institutional overview: Factors influencing faculty participation in

distance education in postsecondary education in the United States: An institutional study.

Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 1(3). Retrieved January 1, 2009,

from http://www.westga.edu/∼distance/Betts13.html

Boettcher, J.V. (2004, June 29). Online course development: What does it cost? Campus

Technology. Retrieved August 28, 2008, from http://www.campustechnology.com/arti-

cles/39863

Bolliger, D.U., & Martindale, T. (2004). Key factors for determining student satisfaction in

online courses. International Journal on E-Learning, 3(1), 61–67.

Bower, B.L. (2001). Distance education: Facing the faculty challenge. Online Journal of

Distance Learning Administration, 4(2). Retrieved January 1, 2009, from http://

www.westga.edu/∼distance/ojdla/summer42/bower42.html

Carr, S. (2000, February 11). As distance education comes of age, the challenge is keeping the

students. Chronicle of Higher Education, 46(23), A39–A41.

Cavanaugh, J. (2005). Teaching online – A time comparison. Online Journal of Distance

Learning Administration, 8(1). Retrieved January 1, 2009, from http://www.westga.edu/

∼distance/ojdla/spring81/cavanaugh81.htm

Conceição, S.C.O. (2006). Faculty lived experiences in the online environment. Adult

Education Quarterly, 57(1), 26–45.

Curran, C. (2008). Online learning and the university. In W.J. Bramble & S. Panda (Eds.),

Economics of distance and online learning: Theory, practice, and research (pp. 26–51).

New York: Routledge.

Durette, A. (2000). Legal perspectives in web course management. In B.L. Mann (Ed.), Perspec-

tives in web course management (pp. 87–101). Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Fredericksen, E., Pickett, A., Shea, P., Pelz, W., & Swan, K. (2000). Factors influencing

faculty satisfaction with asynchronous teaching and learning in the SUNY learning

network. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 4(3) 245–278. Retrieved August

28, 2008, from http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/jaln/v4n3/v4n3_fredericksen.asp

Hagedorn, L.S. (2000). Conceptualizing faculty job satisfaction: Components, theories, and

outcomes. In L.S. Hagedorn (Ed.), What contributes to job satisfaction among faculty and

staff: New directions for institutional research, No. 105 (pp. 5–20). San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Hartman, J., Dziuban, C., & Moskal, P. (2000). Faculty satisfaction in ALNs: A dependent or inde-

pendent variable? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 4(3), 155–177. Retrieved

August 28, 2008, from http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/jaln/v4n3/v4n3_hartman.asp

Hislop, G. (2000). Working professionals as part-time on-line learners. Journal of Asynchro-

nous Learning Networks, 4(2), 73–85. Retrieved September 18, 2007, from http://aln.org/

publications/jaln/v4n2/v4n2_hislop.asp

Hogan, R.L., & McKnight, M.A. (2007). Exploring burnout among university online instruc-

tors: An initial investigation. The Internet and Higher Education, 10(2), 117–124.

Howell, S.L., Saba, F., Lindsay, N.K., & Williams, P.B. (2004). Seven strategies for enabling

faculty success in distance education. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(1), 33–49.

Kenny, J. (2003, March). Student perceptions of the use of online learning technology in their

courses. ultiBase Articles. Retrieved December 28, 2008, from http://ultibase.rmit.edu.au/

Articles/march03/kenny2.pdf

Liaw, S.-S. (2008). Investigating students’ perceived satisfaction, behavioral intention, and

effectiveness of e-learning: A case study of the Blackboard system. Computers & Education,

51(2), 864–873.

Lin, Y., Lin, G., & Laffey, J.M. (2008). Building a social and motivational framework for

understanding satisfaction in online learning. Journal of Educational Computing

Research, 38(1), 1–27.

Astin, A.W. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Baird, L.L. (1980). Importance of surveying student and faculty views. In L.L. Baird, R.T.

Hartnett, & Associates, Understanding student and faculty life: Using campus surveys to

improve academic decision making (pp. 1–67). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bender, D.M., Wood, B.J., & Vredevoogd, J.D. (2004). Teaching time: Distance education

versus classroom instruction. American Journal of Distance Education, 18(2), 103–114.

Betts, K.S. (1998). An institutional overview: Factors influencing faculty participation in

distance education in postsecondary education in the United States: An institutional study.

Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 1(3). Retrieved January 1, 2009,

from http://www.westga.edu/∼distance/Betts13.html

Boettcher, J.V. (2004, June 29). Online course development: What does it cost? Campus

Technology. Retrieved August 28, 2008, from http://www.campustechnology.com/arti-

cles/39863

Bolliger, D.U., & Martindale, T. (2004). Key factors for determining student satisfaction in

online courses. International Journal on E-Learning, 3(1), 61–67.

Bower, B.L. (2001). Distance education: Facing the faculty challenge. Online Journal of

Distance Learning Administration, 4(2). Retrieved January 1, 2009, from http://

www.westga.edu/∼distance/ojdla/summer42/bower42.html