Drilling for Micro-Foundations of Human Capital-Based Competitive Advantages

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/22

|16

|9420

|151

AI Summary

This article explores the micro-foundations of strategic capabilities and the importance of human capital as a source of sustained competitive advantage. It highlights the challenges associated with attracting, retaining, and motivating talented employees and outlines a research agenda for exploring cross-level components of human capital-based advantages.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

http://jom.sagepub.com/

Journal of Management

http://jom.sagepub.com/content/37/5/1429

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0149206310397772

2011 37: 1429 originally published online 22 February 2011Journal of Management

Russell Coff and David Kryscynski

Competitive Advantages

Based−Invited Editorial: Drilling for Micro-Foundations of Human Capital

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Southern Management Association

can be found at:Journal of ManagementAdditional services and information for

http://jom.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://jom.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://jom.sagepub.com/content/37/5/1429.refs.htmlCitations:

What is This?

- Feb 22, 2011OnlineFirst Version of Record

- Feb 28, 2011OnlineFirst Version of Record

- Aug 19, 2011Version of Record>>

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Journal of Management

http://jom.sagepub.com/content/37/5/1429

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0149206310397772

2011 37: 1429 originally published online 22 February 2011Journal of Management

Russell Coff and David Kryscynski

Competitive Advantages

Based−Invited Editorial: Drilling for Micro-Foundations of Human Capital

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Southern Management Association

can be found at:Journal of ManagementAdditional services and information for

http://jom.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://jom.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://jom.sagepub.com/content/37/5/1429.refs.htmlCitations:

What is This?

- Feb 22, 2011OnlineFirst Version of Record

- Feb 28, 2011OnlineFirst Version of Record

- Aug 19, 2011Version of Record>>

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Drilling for Micro-Foundations of Human

Capital–Based Competitive Advantages

Russell Coff

University of Wisconsin–Madison

David Kryscynski

Emory University

From the origins of resource-based theory, scholars have emphasized the importance of human

capital as a source of sustained competitive advantage, and recently there has been great inter-

est in gaining a better understanding of the micro-foundations of strategic capabilities. Along

these lines, there is little doubt that heterogeneous human capital is often a critical underlying

mechanism for capabilities. Here, the authors explore how individual-level phenomena under-

pin isolating mechanisms that sustain human capital–based advantages but also create man-

agement dilemmas that must be resolved in order to create value. The solutions to these

challenges cannot be found purely in generic human resource policies that reflect best prac-

tices. These are not designed to mitigate idiosyncratic dilemmas that arise from the very attri-

butes that hinder imitation (e.g., specificity, social complexity, and causal ambiguity). The

authors drill down deeper to identify individual- and firm-level components that interact to

grant some firms unique capabilities in attracting, retaining, and motivating human capital.

This cospecialization of idiosyncratic individuals and organizational systems may be among the

most powerful isolating mechanism. The authors conclude by outlining a research agenda for

exploring cross-level components of human capital–based advantages.

Keywords: acquisition/strategic factor markets; knowledge management; resource-based

theory; strategic HRM

1429

Corresponding author: Russell Coff, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 4259 Grainger Hall, 975 University

Avenue, Madison, WI 53706, USA

Email: RCoff@bus.wisc.edu

Journal of Management

Vol. 37 No. 5, September 2011 1429-1443

DOI: 10.1177/0149206310397772

© The Author(s) 2011

Reprints and permission: http://www.

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Special Issue:

Twenty Years of

Resource-Based Theory

Invited Editorial

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Capital–Based Competitive Advantages

Russell Coff

University of Wisconsin–Madison

David Kryscynski

Emory University

From the origins of resource-based theory, scholars have emphasized the importance of human

capital as a source of sustained competitive advantage, and recently there has been great inter-

est in gaining a better understanding of the micro-foundations of strategic capabilities. Along

these lines, there is little doubt that heterogeneous human capital is often a critical underlying

mechanism for capabilities. Here, the authors explore how individual-level phenomena under-

pin isolating mechanisms that sustain human capital–based advantages but also create man-

agement dilemmas that must be resolved in order to create value. The solutions to these

challenges cannot be found purely in generic human resource policies that reflect best prac-

tices. These are not designed to mitigate idiosyncratic dilemmas that arise from the very attri-

butes that hinder imitation (e.g., specificity, social complexity, and causal ambiguity). The

authors drill down deeper to identify individual- and firm-level components that interact to

grant some firms unique capabilities in attracting, retaining, and motivating human capital.

This cospecialization of idiosyncratic individuals and organizational systems may be among the

most powerful isolating mechanism. The authors conclude by outlining a research agenda for

exploring cross-level components of human capital–based advantages.

Keywords: acquisition/strategic factor markets; knowledge management; resource-based

theory; strategic HRM

1429

Corresponding author: Russell Coff, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 4259 Grainger Hall, 975 University

Avenue, Madison, WI 53706, USA

Email: RCoff@bus.wisc.edu

Journal of Management

Vol. 37 No. 5, September 2011 1429-1443

DOI: 10.1177/0149206310397772

© The Author(s) 2011

Reprints and permission: http://www.

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Special Issue:

Twenty Years of

Resource-Based Theory

Invited Editorial

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

1430 Journal of Management / September 2011

From the origins of the resource-based theory of the firm, scholars have emphasized the

importance of human capital as a source of sustained competitive advantage (Barney, 1991).

However, the underlying mechanisms tying human capital to competitive advantage have

not been fully developed. Recent calls to drill down to the “micro-foundations” of resources

and capabilities have highlighted the critical role of individuals in creating and sustaining

competitive advantages (Abell, Felin, & Foss, 2008; Felin & Hesterly, 2007; Teece, 2007).

As such, the more we drill down, the more we see that the micro-foundations of capabilities

are bolstered by human capital—that is, the knowledge skills and abilities of individual employ-

ees. Presumably, firms with superior human capital are better positioned to create resources

and capabilities characterized by asset specificity, social complexity, and causal ambiguity,

making them very difficult to imitate (Barney, 1991; Hall, 1993; Reed & DeFillippi, 1990).

While human capital may be at the root of many capabilities, the micro-foundations of

human capital management are not well developed (Coff, 1997). This lack of development

is concerning because, as we shall see, the very factors that make human capital inherently

hard to imitate may also make maximizing value through human capital a highly complex

and difficult challenge. Since valuable capabilities rely on individuals with idiosyncratic goals,

desires, and preferences who can choose whether to join, stay, or exert effort, our search for

solutions may also need to focus on individuals. As Foss (2011; this issue) points out, a more

detailed understanding of individuals and their interactions with each other and the firm may

help us to uncover how firms are better able to cope with the inherent dilemmas associated

with human capital–based competitive advantages.

Our primary thesis, then, is that human capital–based advantages require multilevel solu-

tions to address vexing challenges associated with attracting, retaining, and motivating talented

employees. As such, a human capital–driven advantage requires a set of capabilities and a

complementary set of unique individuals. We review the separate problems of attracting,

motivating, and retaining talented employees and highlight the multilevel nature of human

capital dilemmas as well as their possible solutions. In keeping with the goals of this special

issue, we also highlight fruitful opportunities for future research.

Human Capital and the Promise of Competitive Advantage

Early human capital theory focused on investment decisions that individuals face when

considering acquisitions of new knowledge or skills (Ashenfelter, 1978; Ashenfelter & Krueger,

1994; Becker, 1964; Griliches, 1977). Thus, we must define human capital at the micro

level—an individual’s stock of knowledge, skills, and abilities (hereafter, skills) that can be

increased through mechanisms like education, training, and experience (Becker, 1964). This

definition contrasts conceptualizations often utilized by strategy scholars that characterize

human capital as a unit-level resource (Ployhart & Moliterno, 2011). For convenience, we

refer to the firm-level aggregation of employee skills as firm-level human assets. As such,

the origins of human capital are inherently at the micro level despite a more macro focus in

the strategy literature on the aggregate human capital resources available to the firm (Hatch &

Dyer, 2004; Kor & Leblebici, 2005).

To focus our arguments, we first define human capital–based competitive advantage. Peteraf

and Barney (2003: 314) argue that “an enterprise has a competitive advantage if it is able to

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

From the origins of the resource-based theory of the firm, scholars have emphasized the

importance of human capital as a source of sustained competitive advantage (Barney, 1991).

However, the underlying mechanisms tying human capital to competitive advantage have

not been fully developed. Recent calls to drill down to the “micro-foundations” of resources

and capabilities have highlighted the critical role of individuals in creating and sustaining

competitive advantages (Abell, Felin, & Foss, 2008; Felin & Hesterly, 2007; Teece, 2007).

As such, the more we drill down, the more we see that the micro-foundations of capabilities

are bolstered by human capital—that is, the knowledge skills and abilities of individual employ-

ees. Presumably, firms with superior human capital are better positioned to create resources

and capabilities characterized by asset specificity, social complexity, and causal ambiguity,

making them very difficult to imitate (Barney, 1991; Hall, 1993; Reed & DeFillippi, 1990).

While human capital may be at the root of many capabilities, the micro-foundations of

human capital management are not well developed (Coff, 1997). This lack of development

is concerning because, as we shall see, the very factors that make human capital inherently

hard to imitate may also make maximizing value through human capital a highly complex

and difficult challenge. Since valuable capabilities rely on individuals with idiosyncratic goals,

desires, and preferences who can choose whether to join, stay, or exert effort, our search for

solutions may also need to focus on individuals. As Foss (2011; this issue) points out, a more

detailed understanding of individuals and their interactions with each other and the firm may

help us to uncover how firms are better able to cope with the inherent dilemmas associated

with human capital–based competitive advantages.

Our primary thesis, then, is that human capital–based advantages require multilevel solu-

tions to address vexing challenges associated with attracting, retaining, and motivating talented

employees. As such, a human capital–driven advantage requires a set of capabilities and a

complementary set of unique individuals. We review the separate problems of attracting,

motivating, and retaining talented employees and highlight the multilevel nature of human

capital dilemmas as well as their possible solutions. In keeping with the goals of this special

issue, we also highlight fruitful opportunities for future research.

Human Capital and the Promise of Competitive Advantage

Early human capital theory focused on investment decisions that individuals face when

considering acquisitions of new knowledge or skills (Ashenfelter, 1978; Ashenfelter & Krueger,

1994; Becker, 1964; Griliches, 1977). Thus, we must define human capital at the micro

level—an individual’s stock of knowledge, skills, and abilities (hereafter, skills) that can be

increased through mechanisms like education, training, and experience (Becker, 1964). This

definition contrasts conceptualizations often utilized by strategy scholars that characterize

human capital as a unit-level resource (Ployhart & Moliterno, 2011). For convenience, we

refer to the firm-level aggregation of employee skills as firm-level human assets. As such,

the origins of human capital are inherently at the micro level despite a more macro focus in

the strategy literature on the aggregate human capital resources available to the firm (Hatch &

Dyer, 2004; Kor & Leblebici, 2005).

To focus our arguments, we first define human capital–based competitive advantage. Peteraf

and Barney (2003: 314) argue that “an enterprise has a competitive advantage if it is able to

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Coff, Kryscynski / Human Capital–Based Advantages 1431

create more economic value than the marginal (breakeven) competitor in its product market.”

By extension, a human capital–based advantage arises when this “greater economic value”

is attributable to the firm’s access to and utilization of employee knowledge, skills, and

abilities. Thus, for the present discussion, the critical path to human capital–based competi-

tive advantage requires attracting, retaining, and motivating employees with valuable human

capital at an economic discount relative to competitors.

Isolating Mechanisms and Human Capital

It is widely accepted that human capital holds promise as a source of sustainable advan-

tage since human assets are often valuable, rare, and imperfectly imitable (Barney, 1991;

Hall, 1993; Hatch & Dyer, 2004). Human capital is valuable for the unique abilities that

individuals can bring, and it can also be quite rare—particularly at high levels of specialized

expertise. Finally, to result in a sustained advantage, human capital must be associated with

isolating mechanisms that keep rivals at bay. Human capital–based advantages are often

linked to three key isolating mechanisms: firm-specificity, social complexity, and causal

ambiguity. These operate simultaneously at the firm level and the individual level in slightly

different ways, as we discuss below. It is worth underscoring that human capital derives its

strategic importance from idiosyncratic individual differences—again highlighting the need

for strong micro-foundations.

Firm-specificity is the extent to which individual assets are tailored for use in a single

firm (Williamson, 1975). The strategy literature often treats specificity as a requirement for

strategic assets (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993). Firm-specificity can serve as an isolating

mechanism since there is no market to bid up the price of these assets (Klein, Crawford, &

Alchian, 1978)—they cannot be deployed in other contexts. At the firm level, firm-specificity

describes the extent to which human assets are more valuable to the current firm than to

rivals. For individuals, firm-specificity may limit mobility since employees’ skills are less

valuable to other firms. Skills can be more or less firm-specific due to idiosyncratic attributes

(Becker, 1964) or due to complex combinations of general skills that lead to idiosyncratic

bundles of skills (Lazear, 2009).

Social complexity refers to the extent to which individual assets are embedded in highly

complex social systems (Barney, 1991). At the firm level, these socially complex systems

hinder the replication of human assets—systems that are more complex are harder to copy.

The resources might be quite valuable to competitors, but the complexity makes them very

difficult to copy. Additionally, as complexity increases, it becomes more difficult to extract

any single piece of the system without degrading value. In other words, the value of a single

employee’s human capital may be drastically reduced if plucked out of the particular com-

plex social system.

Causal ambiguity is the extent to which individual assets are difficult to link to organiza-

tional performance (Lippman & Rumelt, 1982; Reed & DeFillippi, 1990). At the firm level,

it may be hard to link human capital to performance. On the individual level, the importance

of tacit knowledge presents additional dilemmas precisely because it resides in the heads of

individuals (Felin & Hesterly, 2007). Tacit knowledge can be causally ambiguous both for

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

create more economic value than the marginal (breakeven) competitor in its product market.”

By extension, a human capital–based advantage arises when this “greater economic value”

is attributable to the firm’s access to and utilization of employee knowledge, skills, and

abilities. Thus, for the present discussion, the critical path to human capital–based competi-

tive advantage requires attracting, retaining, and motivating employees with valuable human

capital at an economic discount relative to competitors.

Isolating Mechanisms and Human Capital

It is widely accepted that human capital holds promise as a source of sustainable advan-

tage since human assets are often valuable, rare, and imperfectly imitable (Barney, 1991;

Hall, 1993; Hatch & Dyer, 2004). Human capital is valuable for the unique abilities that

individuals can bring, and it can also be quite rare—particularly at high levels of specialized

expertise. Finally, to result in a sustained advantage, human capital must be associated with

isolating mechanisms that keep rivals at bay. Human capital–based advantages are often

linked to three key isolating mechanisms: firm-specificity, social complexity, and causal

ambiguity. These operate simultaneously at the firm level and the individual level in slightly

different ways, as we discuss below. It is worth underscoring that human capital derives its

strategic importance from idiosyncratic individual differences—again highlighting the need

for strong micro-foundations.

Firm-specificity is the extent to which individual assets are tailored for use in a single

firm (Williamson, 1975). The strategy literature often treats specificity as a requirement for

strategic assets (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993). Firm-specificity can serve as an isolating

mechanism since there is no market to bid up the price of these assets (Klein, Crawford, &

Alchian, 1978)—they cannot be deployed in other contexts. At the firm level, firm-specificity

describes the extent to which human assets are more valuable to the current firm than to

rivals. For individuals, firm-specificity may limit mobility since employees’ skills are less

valuable to other firms. Skills can be more or less firm-specific due to idiosyncratic attributes

(Becker, 1964) or due to complex combinations of general skills that lead to idiosyncratic

bundles of skills (Lazear, 2009).

Social complexity refers to the extent to which individual assets are embedded in highly

complex social systems (Barney, 1991). At the firm level, these socially complex systems

hinder the replication of human assets—systems that are more complex are harder to copy.

The resources might be quite valuable to competitors, but the complexity makes them very

difficult to copy. Additionally, as complexity increases, it becomes more difficult to extract

any single piece of the system without degrading value. In other words, the value of a single

employee’s human capital may be drastically reduced if plucked out of the particular com-

plex social system.

Causal ambiguity is the extent to which individual assets are difficult to link to organiza-

tional performance (Lippman & Rumelt, 1982; Reed & DeFillippi, 1990). At the firm level,

it may be hard to link human capital to performance. On the individual level, the importance

of tacit knowledge presents additional dilemmas precisely because it resides in the heads of

individuals (Felin & Hesterly, 2007). Tacit knowledge can be causally ambiguous both for

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1432 Journal of Management / September 2011

managers and competitors. It is unclear who has the knowledge, or even which knowledge

is critical. Thus, causal ambiguity hinders rivals’ attempts to identify which aspects of a

firm’s human capital management routines to copy and which employees are most important

to hire away.

Generic Human Resource Systems Cannot Fully Explain Human Capital–Based

Advantages

Taken together, firm-specificity, social complexity and causal ambiguity provide three

mechanisms that may explain why human assets can be a key source of sustained advantage.

Accordingly, the strategic human resource (HR) management literature has continued a rich

tradition of prescribing HR systems and policies that enhance a firm’s human capital resources

(Arthur, 1994; Lado & Wilson, 1994). However, one could argue that these fully codified

solutions are easily understood and, thus, unlikely to offer sustained human capital advan-

tages on their own (Chadwick & Dabu, 2009). If so, we should generally expect these “best

practice” solutions to be strategically less relevant. In other words, these systems may help

firms increase efficiency given their chosen strategies, but the systems are chosen to fit with

a strategy rather than to provide sustained advantages in and of themselves.

Additionally, Becker and Huselid (2006) critique the strategic HR literature for its “black

box” approach to relating HR systems to firm performance. They explicitly call for more

theory and empirical analysis to open this black box and more carefully articulate the mecha-

nisms connecting HR systems to human capital–based advantages. We echo these concerns

and also suggest that an excessive focus on firm-level HR practices has obscured the inher-

ently multilevel nature of human capital (Ployhart & Moliterno, 2011). A more careful analy-

sis at the individual and firm levels reveals both varied sources of the isolating mechanisms

and underappreciated dilemmas created by these mechanisms.

Micro-Foundations and Human Capital–Based Dilemmas

While human capital is a promising source of sustained competitive advantage, the attri-

butes that make these resources so attractive also pose significant management dilemmas.

As Coff (1997) points out, unlike other types of resources, humans can quit, withhold effort,

and bargain for rents. To create and sustain superior human assets, managers must mitigate

challenges linked to (1) attracting and hiring critical employees, (2) retaining the best

employees, and (3) motivating employees. Successfully navigating these challenges provides

a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for a human capital–based competitive advantage.

In the following sections, we explore these challenges along with potential coping strategies.

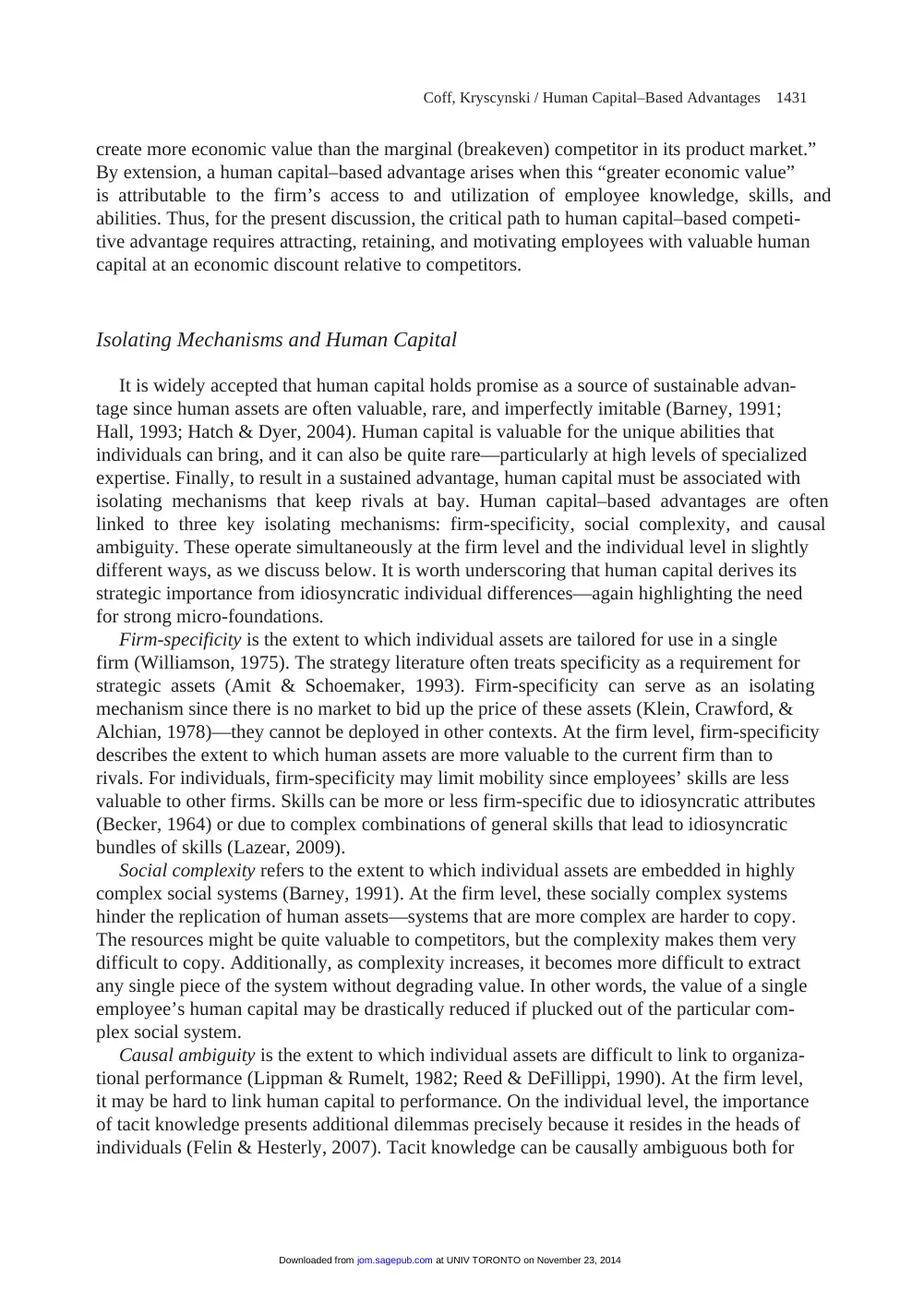

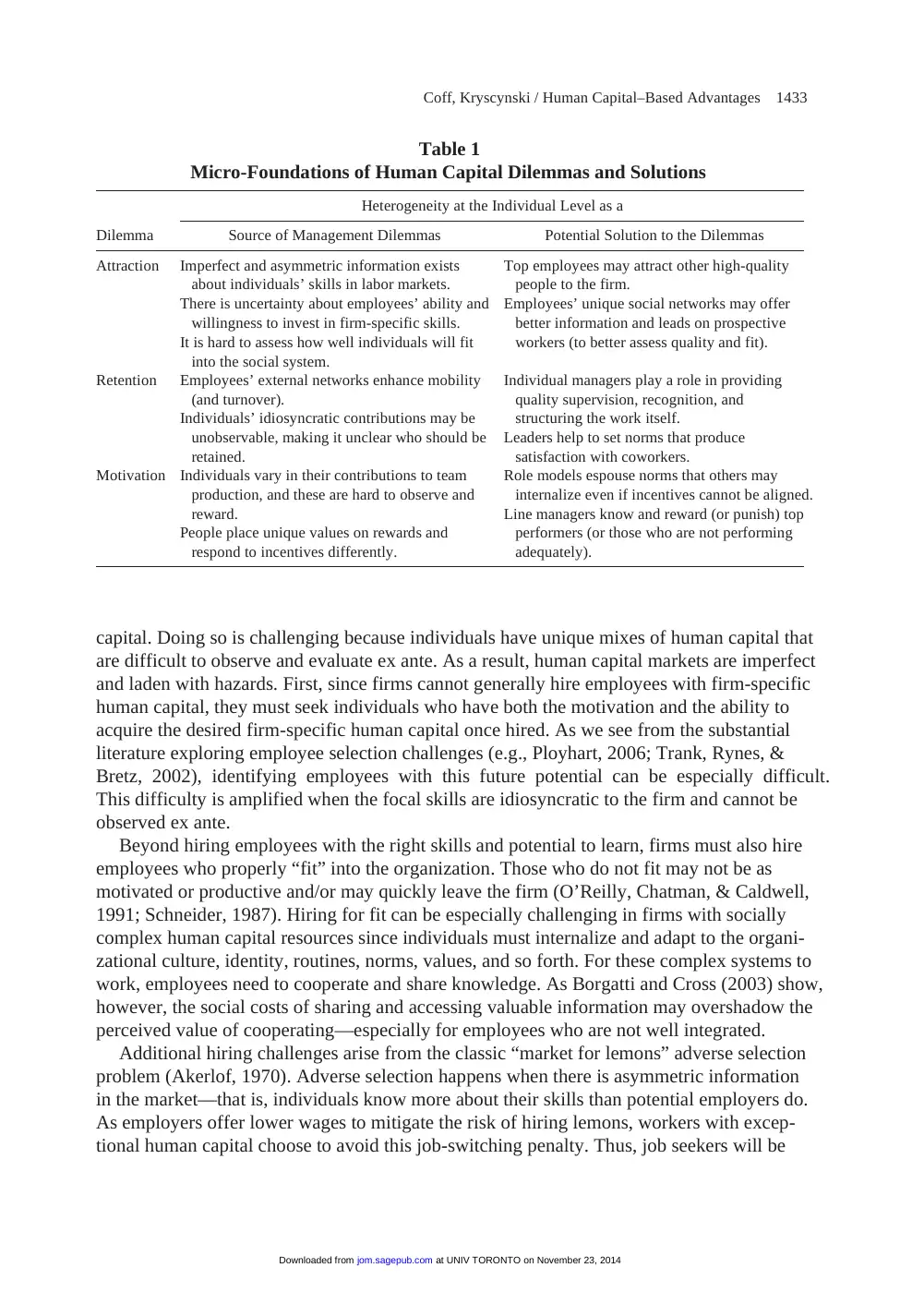

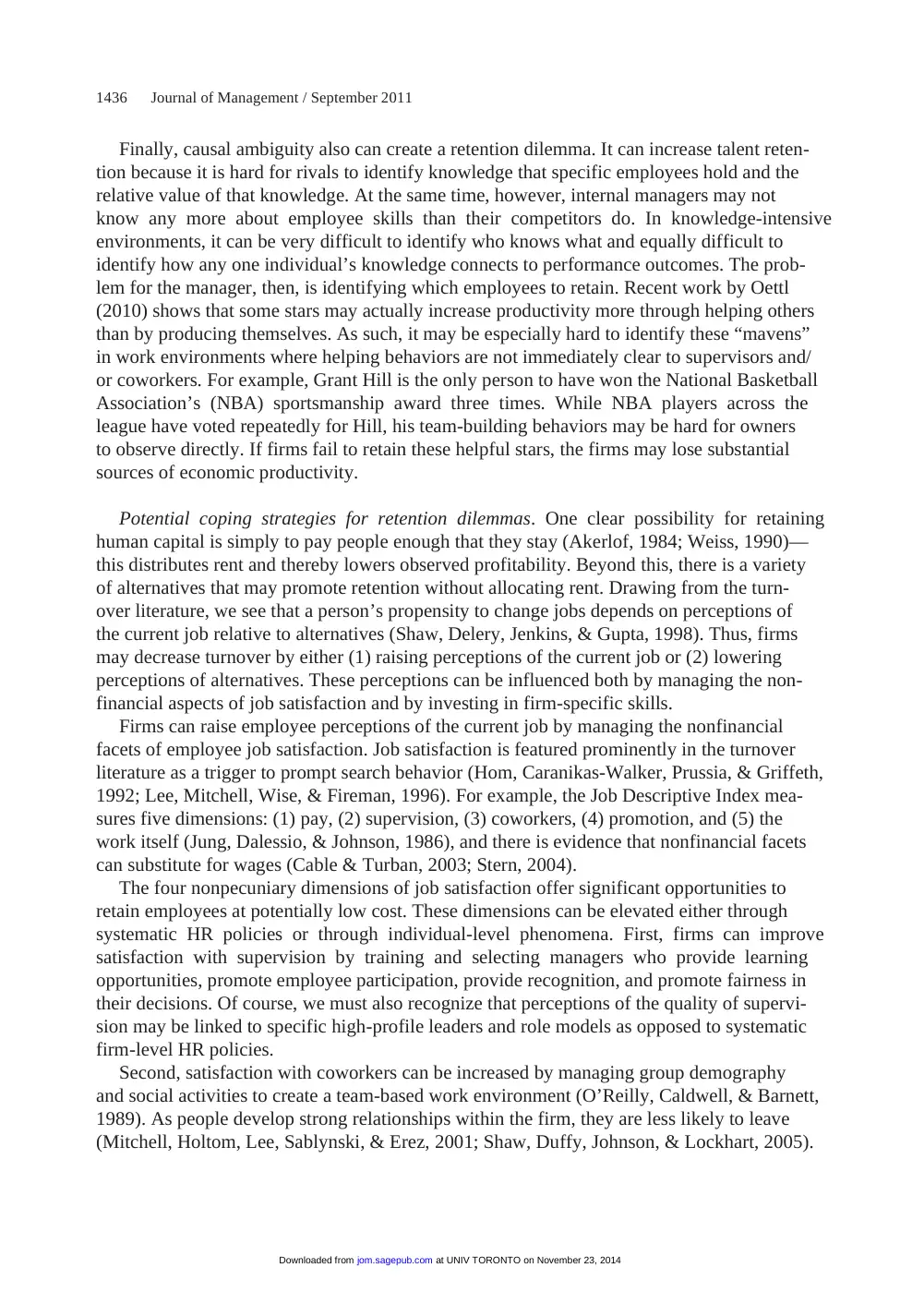

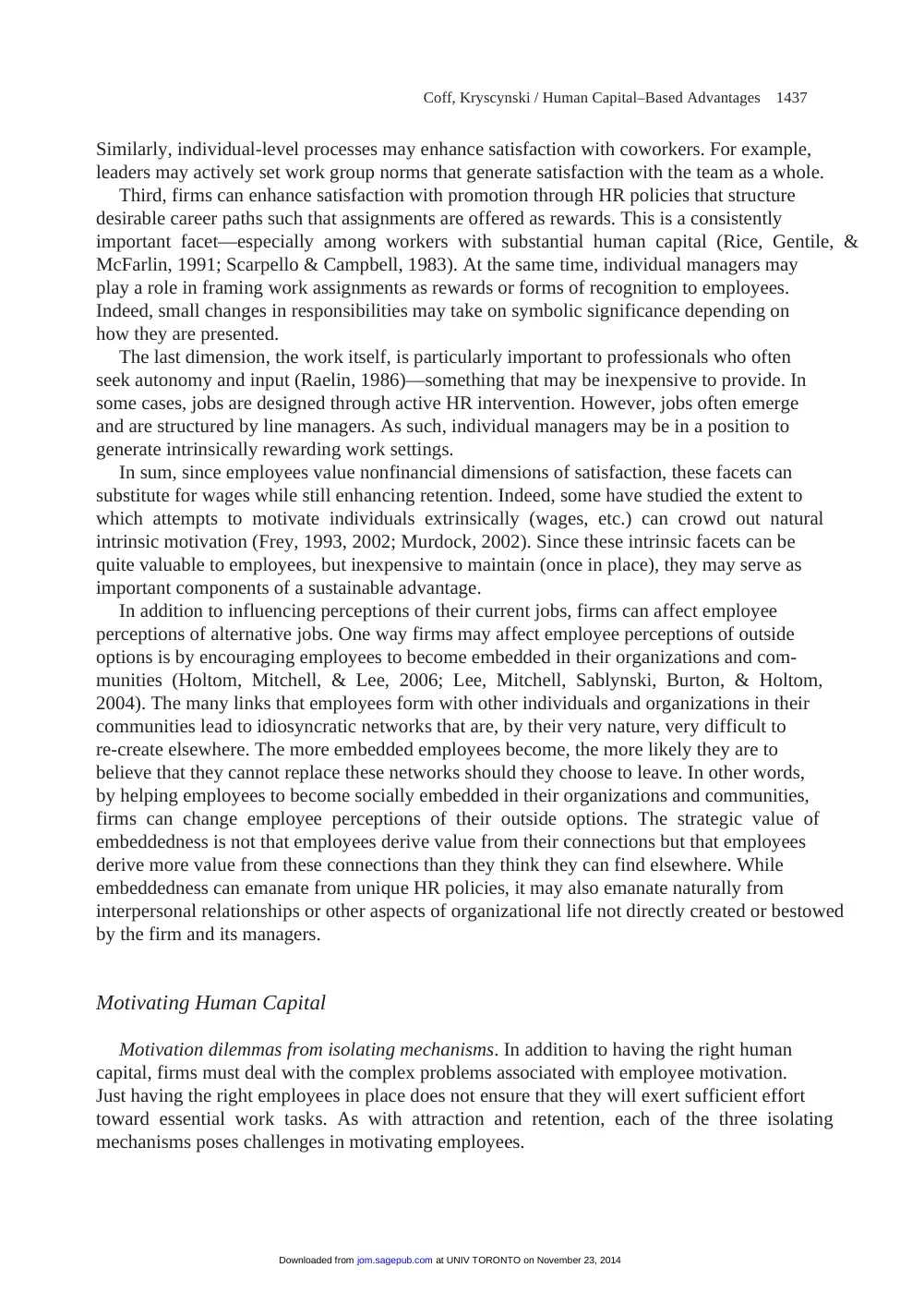

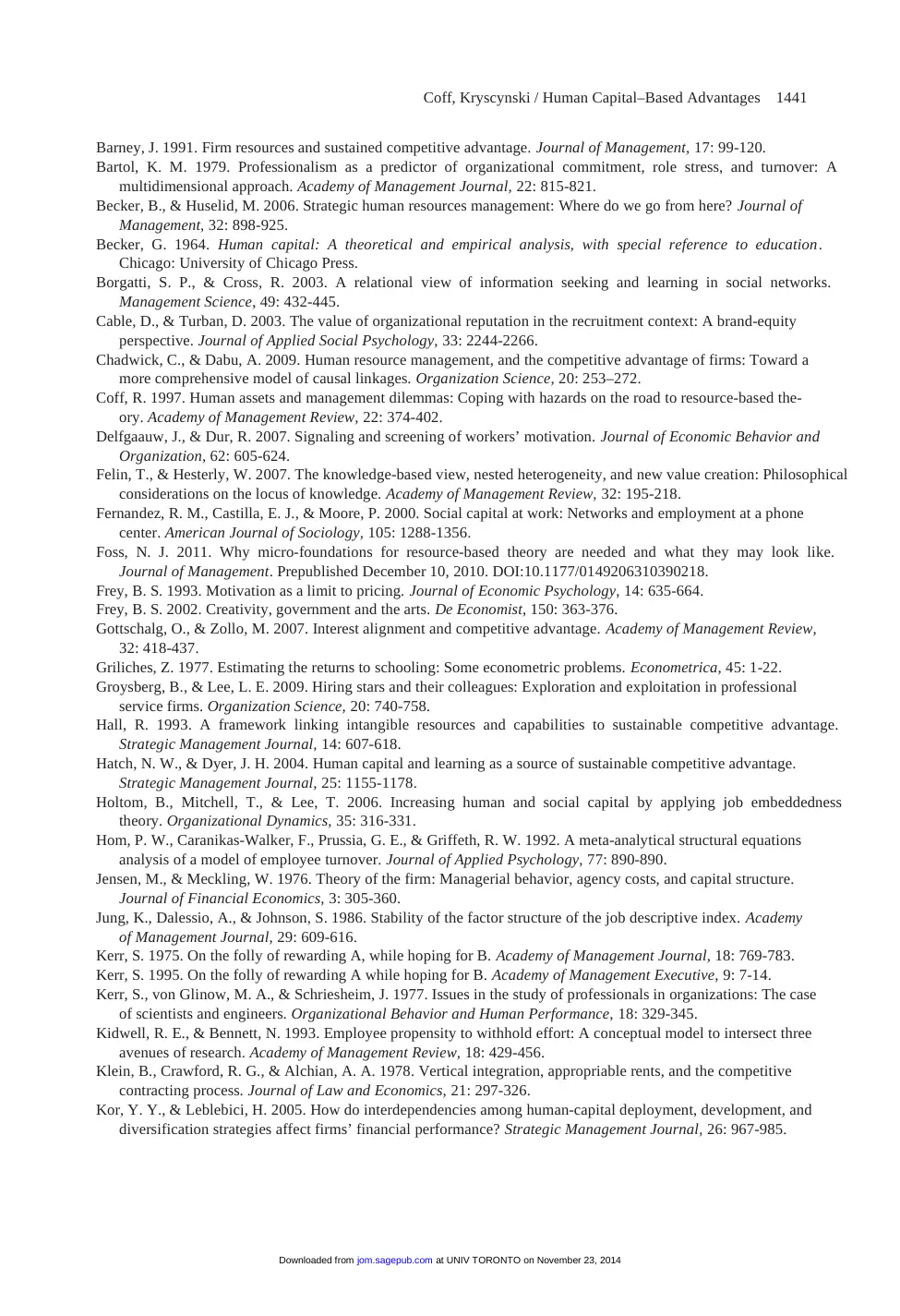

A summary of our arguments is shown in Table 1.

Attracting Human Capital

Attraction dilemmas from isolating mechanisms. The first challenge on the road to a

human capital–based advantage is attracting and hiring employees with valuable human

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

managers and competitors. It is unclear who has the knowledge, or even which knowledge

is critical. Thus, causal ambiguity hinders rivals’ attempts to identify which aspects of a

firm’s human capital management routines to copy and which employees are most important

to hire away.

Generic Human Resource Systems Cannot Fully Explain Human Capital–Based

Advantages

Taken together, firm-specificity, social complexity and causal ambiguity provide three

mechanisms that may explain why human assets can be a key source of sustained advantage.

Accordingly, the strategic human resource (HR) management literature has continued a rich

tradition of prescribing HR systems and policies that enhance a firm’s human capital resources

(Arthur, 1994; Lado & Wilson, 1994). However, one could argue that these fully codified

solutions are easily understood and, thus, unlikely to offer sustained human capital advan-

tages on their own (Chadwick & Dabu, 2009). If so, we should generally expect these “best

practice” solutions to be strategically less relevant. In other words, these systems may help

firms increase efficiency given their chosen strategies, but the systems are chosen to fit with

a strategy rather than to provide sustained advantages in and of themselves.

Additionally, Becker and Huselid (2006) critique the strategic HR literature for its “black

box” approach to relating HR systems to firm performance. They explicitly call for more

theory and empirical analysis to open this black box and more carefully articulate the mecha-

nisms connecting HR systems to human capital–based advantages. We echo these concerns

and also suggest that an excessive focus on firm-level HR practices has obscured the inher-

ently multilevel nature of human capital (Ployhart & Moliterno, 2011). A more careful analy-

sis at the individual and firm levels reveals both varied sources of the isolating mechanisms

and underappreciated dilemmas created by these mechanisms.

Micro-Foundations and Human Capital–Based Dilemmas

While human capital is a promising source of sustained competitive advantage, the attri-

butes that make these resources so attractive also pose significant management dilemmas.

As Coff (1997) points out, unlike other types of resources, humans can quit, withhold effort,

and bargain for rents. To create and sustain superior human assets, managers must mitigate

challenges linked to (1) attracting and hiring critical employees, (2) retaining the best

employees, and (3) motivating employees. Successfully navigating these challenges provides

a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for a human capital–based competitive advantage.

In the following sections, we explore these challenges along with potential coping strategies.

A summary of our arguments is shown in Table 1.

Attracting Human Capital

Attraction dilemmas from isolating mechanisms. The first challenge on the road to a

human capital–based advantage is attracting and hiring employees with valuable human

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Coff, Kryscynski / Human Capital–Based Advantages 1433

capital. Doing so is challenging because individuals have unique mixes of human capital that

are difficult to observe and evaluate ex ante. As a result, human capital markets are imperfect

and laden with hazards. First, since firms cannot generally hire employees with firm-specific

human capital, they must seek individuals who have both the motivation and the ability to

acquire the desired firm-specific human capital once hired. As we see from the substantial

literature exploring employee selection challenges (e.g., Ployhart, 2006; Trank, Rynes, &

Bretz, 2002), identifying employees with this future potential can be especially difficult.

This difficulty is amplified when the focal skills are idiosyncratic to the firm and cannot be

observed ex ante.

Beyond hiring employees with the right skills and potential to learn, firms must also hire

employees who properly “fit” into the organization. Those who do not fit may not be as

motivated or productive and/or may quickly leave the firm (O’Reilly, Chatman, & Caldwell,

1991; Schneider, 1987). Hiring for fit can be especially challenging in firms with socially

complex human capital resources since individuals must internalize and adapt to the organi-

zational culture, identity, routines, norms, values, and so forth. For these complex systems to

work, employees need to cooperate and share knowledge. As Borgatti and Cross (2003) show,

however, the social costs of sharing and accessing valuable information may overshadow the

perceived value of cooperating—especially for employees who are not well integrated.

Additional hiring challenges arise from the classic “market for lemons” adverse selection

problem (Akerlof, 1970). Adverse selection happens when there is asymmetric information

in the market—that is, individuals know more about their skills than potential employers do.

As employers offer lower wages to mitigate the risk of hiring lemons, workers with excep-

tional human capital choose to avoid this job-switching penalty. Thus, job seekers will be

Table 1

Micro-Foundations of Human Capital Dilemmas and Solutions

Heterogeneity at the Individual Level as a

Dilemma Source of Management Dilemmas Potential Solution to the Dilemmas

Attraction Imperfect and asymmetric information exists

about individuals’ skills in labor markets.

There is uncertainty about employees’ ability and

willingness to invest in firm-specific skills.

It is hard to assess how well individuals will fit

into the social system.

Top employees may attract other high-quality

people to the firm.

Employees’ unique social networks may offer

better information and leads on prospective

workers (to better assess quality and fit).

Retention Employees’ external networks enhance mobility

(and turnover).

Individuals’ idiosyncratic contributions may be

unobservable, making it unclear who should be

retained.

Individual managers play a role in providing

quality supervision, recognition, and

structuring the work itself.

Leaders help to set norms that produce

satisfaction with coworkers.

Motivation Individuals vary in their contributions to team

production, and these are hard to observe and

reward.

People place unique values on rewards and

respond to incentives differently.

Role models espouse norms that others may

internalize even if incentives cannot be aligned.

Line managers know and reward (or punish) top

performers (or those who are not performing

adequately).

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

capital. Doing so is challenging because individuals have unique mixes of human capital that

are difficult to observe and evaluate ex ante. As a result, human capital markets are imperfect

and laden with hazards. First, since firms cannot generally hire employees with firm-specific

human capital, they must seek individuals who have both the motivation and the ability to

acquire the desired firm-specific human capital once hired. As we see from the substantial

literature exploring employee selection challenges (e.g., Ployhart, 2006; Trank, Rynes, &

Bretz, 2002), identifying employees with this future potential can be especially difficult.

This difficulty is amplified when the focal skills are idiosyncratic to the firm and cannot be

observed ex ante.

Beyond hiring employees with the right skills and potential to learn, firms must also hire

employees who properly “fit” into the organization. Those who do not fit may not be as

motivated or productive and/or may quickly leave the firm (O’Reilly, Chatman, & Caldwell,

1991; Schneider, 1987). Hiring for fit can be especially challenging in firms with socially

complex human capital resources since individuals must internalize and adapt to the organi-

zational culture, identity, routines, norms, values, and so forth. For these complex systems to

work, employees need to cooperate and share knowledge. As Borgatti and Cross (2003) show,

however, the social costs of sharing and accessing valuable information may overshadow the

perceived value of cooperating—especially for employees who are not well integrated.

Additional hiring challenges arise from the classic “market for lemons” adverse selection

problem (Akerlof, 1970). Adverse selection happens when there is asymmetric information

in the market—that is, individuals know more about their skills than potential employers do.

As employers offer lower wages to mitigate the risk of hiring lemons, workers with excep-

tional human capital choose to avoid this job-switching penalty. Thus, job seekers will be

Table 1

Micro-Foundations of Human Capital Dilemmas and Solutions

Heterogeneity at the Individual Level as a

Dilemma Source of Management Dilemmas Potential Solution to the Dilemmas

Attraction Imperfect and asymmetric information exists

about individuals’ skills in labor markets.

There is uncertainty about employees’ ability and

willingness to invest in firm-specific skills.

It is hard to assess how well individuals will fit

into the social system.

Top employees may attract other high-quality

people to the firm.

Employees’ unique social networks may offer

better information and leads on prospective

workers (to better assess quality and fit).

Retention Employees’ external networks enhance mobility

(and turnover).

Individuals’ idiosyncratic contributions may be

unobservable, making it unclear who should be

retained.

Individual managers play a role in providing

quality supervision, recognition, and

structuring the work itself.

Leaders help to set norms that produce

satisfaction with coworkers.

Motivation Individuals vary in their contributions to team

production, and these are hard to observe and

reward.

People place unique values on rewards and

respond to incentives differently.

Role models espouse norms that others may

internalize even if incentives cannot be aligned.

Line managers know and reward (or punish) top

performers (or those who are not performing

adequately).

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

1434 Journal of Management / September 2011

disproportionately low-quality workers. Causal ambiguity can further exacerbate this lemons

problem by making it more difficult to identify how prospective employees may have con-

tributed to their prior employers’ successes. For example, applicants may misrepresent them-

selves by taking credit for others’ successes. Causal ambiguity will thwart efforts to verify

such claims.

These dilemmas highlight a very complicated attraction challenge—firms must attract

high-quality employees amid imperfect information about their skills, abilities, and fit with

the organization, while employees may offer incorrect or misleading information about their

own qualities. Firms often rely on crude signals, such as educational level, even though wide

variations in productivity remain (Delfgaauw & Dur, 2007; Spence, 1973). Thus, the ability

to identify individuals with valuable human capital, using incomplete information, may be

quite central to competitive advantage. This mastery may take the form of a competency in

gathering and interpreting labor market signals—a driving force behind strategic factor mar-

ket theory (Barney, 1986b; Makadok & Barney, 2001). For example, in the book Moneyball,

Michael Lewis (2004) describes how the Oakland Athletics used a different set of signals

than those of rivals and so were able to identify good baseball players that other teams ignored

and acquired those players at economic discounts.

Coping strategies for attraction dilemmas. Strategic HR scholars have devoted much

research to uncovering various selection policies and practices that reduce uncertainty and

improve fit in the hiring process (see Ployhart, 2006, for a recent review). However, our dis-

cussion has focused on the specific problems linked to firm-specificity, social complexity,

and causal ambiguity. These problems may not be present in all cases in equal measure. As

such, HR practices geared toward identifying those who can and will invest in specific human

capital may be important only in some contexts. These practices might include gaining labor

market intelligence through checking references or, perhaps, in-basket exercises to see if

applicants pick up subtleties as they respond to simulated problems. In other settings, the

problem may be finding people who fit into a team-based setting. Here, it may be more impor-

tant to develop an assessment center approach to identify team-based skills. Thus, the specific

bundle of HR policies may need to be just as idiosyncratic as the underlying human assets.

Beyond the application of idiosyncratic HR policies, we suggest two additional avenues

of research that especially highlight the micro-foundations of this attraction problem. First,

high-quality employees may be particularly concerned with the quality of coworkers, espe-

cially in knowledge-intensive environments where mentorship can have long-term career

impacts. Having current “stars” may help an organization attract future stars. This possibility

opens interesting avenues for human capital scholars where the economic value of hiring

stars is repeatedly questioned (Adler & Kwon, 2002; Groysberg & Lee, 2009)—since stars

can appropriate so much of their value, are they really worth the high market wages? If up-

and-coming stars are attracted by existing stars, then these up-and-coming stars may be

willing to make wage or other sacrifices in order to work with existing stars, just as employ-

ees may be willing to forego wages for other nonpecuniary job benefits (Cable & Turban,

2003; Stern, 2004).

Second, the interpersonal networks of current employees can provide excellent sources

of information about potential employees, as evidenced by recent increases in employee

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

disproportionately low-quality workers. Causal ambiguity can further exacerbate this lemons

problem by making it more difficult to identify how prospective employees may have con-

tributed to their prior employers’ successes. For example, applicants may misrepresent them-

selves by taking credit for others’ successes. Causal ambiguity will thwart efforts to verify

such claims.

These dilemmas highlight a very complicated attraction challenge—firms must attract

high-quality employees amid imperfect information about their skills, abilities, and fit with

the organization, while employees may offer incorrect or misleading information about their

own qualities. Firms often rely on crude signals, such as educational level, even though wide

variations in productivity remain (Delfgaauw & Dur, 2007; Spence, 1973). Thus, the ability

to identify individuals with valuable human capital, using incomplete information, may be

quite central to competitive advantage. This mastery may take the form of a competency in

gathering and interpreting labor market signals—a driving force behind strategic factor mar-

ket theory (Barney, 1986b; Makadok & Barney, 2001). For example, in the book Moneyball,

Michael Lewis (2004) describes how the Oakland Athletics used a different set of signals

than those of rivals and so were able to identify good baseball players that other teams ignored

and acquired those players at economic discounts.

Coping strategies for attraction dilemmas. Strategic HR scholars have devoted much

research to uncovering various selection policies and practices that reduce uncertainty and

improve fit in the hiring process (see Ployhart, 2006, for a recent review). However, our dis-

cussion has focused on the specific problems linked to firm-specificity, social complexity,

and causal ambiguity. These problems may not be present in all cases in equal measure. As

such, HR practices geared toward identifying those who can and will invest in specific human

capital may be important only in some contexts. These practices might include gaining labor

market intelligence through checking references or, perhaps, in-basket exercises to see if

applicants pick up subtleties as they respond to simulated problems. In other settings, the

problem may be finding people who fit into a team-based setting. Here, it may be more impor-

tant to develop an assessment center approach to identify team-based skills. Thus, the specific

bundle of HR policies may need to be just as idiosyncratic as the underlying human assets.

Beyond the application of idiosyncratic HR policies, we suggest two additional avenues

of research that especially highlight the micro-foundations of this attraction problem. First,

high-quality employees may be particularly concerned with the quality of coworkers, espe-

cially in knowledge-intensive environments where mentorship can have long-term career

impacts. Having current “stars” may help an organization attract future stars. This possibility

opens interesting avenues for human capital scholars where the economic value of hiring

stars is repeatedly questioned (Adler & Kwon, 2002; Groysberg & Lee, 2009)—since stars

can appropriate so much of their value, are they really worth the high market wages? If up-

and-coming stars are attracted by existing stars, then these up-and-coming stars may be

willing to make wage or other sacrifices in order to work with existing stars, just as employ-

ees may be willing to forego wages for other nonpecuniary job benefits (Cable & Turban,

2003; Stern, 2004).

Second, the interpersonal networks of current employees can provide excellent sources

of information about potential employees, as evidenced by recent increases in employee

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Coff, Kryscynski / Human Capital–Based Advantages 1435

referral programs. Firms appear to experience substantial hiring benefits, such as better

fit, higher employee quality, and lower subsequent turnover, by using employee referrals

(Fernandez, Castilla, & Moore, 2000). These benefits derive not from intraorganizational social

networks, or from any formal organizational ties, but rather from the informal and personal

social networks of the individual employees.

In this way, a focus on organization-level solutions to attraction dilemmas may lead to a

lack of emphasis on individual-level factors that may be critical in generating firm-level

heterogeneity in human capital. While heterogeneity among individuals may be the source

of substantial attraction and hiring dilemmas, individuals may also be part of the solution to

overcome these challenges. These examples of how individuals may help to mitigate hiring

dilemmas only scratch the surface. The strong focus on organization-level policies and rou-

tines has undoubtedly left many opportunities to integrate micro-foundations of attraction

and hiring into theories of human capital–based advantages.

Retaining Human Capital

Retention dilemmas from isolating mechanisms. The three isolating mechanisms also

engender challenges for retaining human capital. For example, a paradox arises from the fact

that firms often seek people who, once hired, will be adept at acquiring firm-specific knowl-

edge and routines. In this case, ironically, the best labor market signal of employee quality may

be whether individuals have gained specific skills at other firms (Morris, Alvarez, Barney, &

Molloy, 2010). The most observable indicator of employees’ firm-specific skills may be their

tenure at firms known to produce proprietary knowledge. The employees’ actual skills may not

be valuable outside of the focal firm, but the ability to acquire new firm-specific knowledge

may be quite valuable. The irony, then, is that knowledge that cannot be applied in other firms

may actually increase employees’ mobility, as other employers infer that such individuals will

be able to acquire new firm-specific knowledge. Accordingly, turnover may be more of a threat

for firm-specific human assets then is normally presumed in the literature (Becker, 1964).

Social complexity also may pose retention hazards. On one hand, it can have a strong

firm-specific component—as social complexity increases, employees need more sophisticated

mental mappings of who knows what and how things get done in the firm. Here, social com-

plexity may enhance retention if the social ties are valuable within the firm but not appli-

cable externally. Of course, as the discussion above suggests, the ability to form ties may be

in strong demand even if the actual ties are not.

On the other hand, some forms of social complexity may directly increase an individual’s

value in the labor market. Boundary spanners, for example, are embedded in complex social

networks that span both internal and external relationships. These boundary-spanning rela-

tionships may be quite valuable to rivals (Bartol, 1979; Kerr, von Glinow, & Schriesheim,

1977). Losing these boundary spanners, however, can be quite damaging because they are

critical for dynamic capabilities—that is, they often help the firm to incorporate external

knowledge and information. Accordingly, social complexity may directly or indirectly increase

the threat of employee turnover. Whether a given individual is at risk for turnover depends

on the nature of his or her social ties.

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

referral programs. Firms appear to experience substantial hiring benefits, such as better

fit, higher employee quality, and lower subsequent turnover, by using employee referrals

(Fernandez, Castilla, & Moore, 2000). These benefits derive not from intraorganizational social

networks, or from any formal organizational ties, but rather from the informal and personal

social networks of the individual employees.

In this way, a focus on organization-level solutions to attraction dilemmas may lead to a

lack of emphasis on individual-level factors that may be critical in generating firm-level

heterogeneity in human capital. While heterogeneity among individuals may be the source

of substantial attraction and hiring dilemmas, individuals may also be part of the solution to

overcome these challenges. These examples of how individuals may help to mitigate hiring

dilemmas only scratch the surface. The strong focus on organization-level policies and rou-

tines has undoubtedly left many opportunities to integrate micro-foundations of attraction

and hiring into theories of human capital–based advantages.

Retaining Human Capital

Retention dilemmas from isolating mechanisms. The three isolating mechanisms also

engender challenges for retaining human capital. For example, a paradox arises from the fact

that firms often seek people who, once hired, will be adept at acquiring firm-specific knowl-

edge and routines. In this case, ironically, the best labor market signal of employee quality may

be whether individuals have gained specific skills at other firms (Morris, Alvarez, Barney, &

Molloy, 2010). The most observable indicator of employees’ firm-specific skills may be their

tenure at firms known to produce proprietary knowledge. The employees’ actual skills may not

be valuable outside of the focal firm, but the ability to acquire new firm-specific knowledge

may be quite valuable. The irony, then, is that knowledge that cannot be applied in other firms

may actually increase employees’ mobility, as other employers infer that such individuals will

be able to acquire new firm-specific knowledge. Accordingly, turnover may be more of a threat

for firm-specific human assets then is normally presumed in the literature (Becker, 1964).

Social complexity also may pose retention hazards. On one hand, it can have a strong

firm-specific component—as social complexity increases, employees need more sophisticated

mental mappings of who knows what and how things get done in the firm. Here, social com-

plexity may enhance retention if the social ties are valuable within the firm but not appli-

cable externally. Of course, as the discussion above suggests, the ability to form ties may be

in strong demand even if the actual ties are not.

On the other hand, some forms of social complexity may directly increase an individual’s

value in the labor market. Boundary spanners, for example, are embedded in complex social

networks that span both internal and external relationships. These boundary-spanning rela-

tionships may be quite valuable to rivals (Bartol, 1979; Kerr, von Glinow, & Schriesheim,

1977). Losing these boundary spanners, however, can be quite damaging because they are

critical for dynamic capabilities—that is, they often help the firm to incorporate external

knowledge and information. Accordingly, social complexity may directly or indirectly increase

the threat of employee turnover. Whether a given individual is at risk for turnover depends

on the nature of his or her social ties.

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

1436 Journal of Management / September 2011

Finally, causal ambiguity also can create a retention dilemma. It can increase talent reten-

tion because it is hard for rivals to identify knowledge that specific employees hold and the

relative value of that knowledge. At the same time, however, internal managers may not

know any more about employee skills than their competitors do. In knowledge-intensive

environments, it can be very difficult to identify who knows what and equally difficult to

identify how any one individual’s knowledge connects to performance outcomes. The prob-

lem for the manager, then, is identifying which employees to retain. Recent work by Oettl

(2010) shows that some stars may actually increase productivity more through helping others

than by producing themselves. As such, it may be especially hard to identify these “mavens”

in work environments where helping behaviors are not immediately clear to supervisors and/

or coworkers. For example, Grant Hill is the only person to have won the National Basketball

Association’s (NBA) sportsmanship award three times. While NBA players across the

league have voted repeatedly for Hill, his team-building behaviors may be hard for owners

to observe directly. If firms fail to retain these helpful stars, the firms may lose substantial

sources of economic productivity.

Potential coping strategies for retention dilemmas. One clear possibility for retaining

human capital is simply to pay people enough that they stay (Akerlof, 1984; Weiss, 1990)—

this distributes rent and thereby lowers observed profitability. Beyond this, there is a variety

of alternatives that may promote retention without allocating rent. Drawing from the turn-

over literature, we see that a person’s propensity to change jobs depends on perceptions of

the current job relative to alternatives (Shaw, Delery, Jenkins, & Gupta, 1998). Thus, firms

may decrease turnover by either (1) raising perceptions of the current job or (2) lowering

perceptions of alternatives. These perceptions can be influenced both by managing the non-

financial aspects of job satisfaction and by investing in firm-specific skills.

Firms can raise employee perceptions of the current job by managing the nonfinancial

facets of employee job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is featured prominently in the turnover

literature as a trigger to prompt search behavior (Hom, Caranikas-Walker, Prussia, & Griffeth,

1992; Lee, Mitchell, Wise, & Fireman, 1996). For example, the Job Descriptive Index mea-

sures five dimensions: (1) pay, (2) supervision, (3) coworkers, (4) promotion, and (5) the

work itself (Jung, Dalessio, & Johnson, 1986), and there is evidence that nonfinancial facets

can substitute for wages (Cable & Turban, 2003; Stern, 2004).

The four nonpecuniary dimensions of job satisfaction offer significant opportunities to

retain employees at potentially low cost. These dimensions can be elevated either through

systematic HR policies or through individual-level phenomena. First, firms can improve

satisfaction with supervision by training and selecting managers who provide learning

opportunities, promote employee participation, provide recognition, and promote fairness in

their decisions. Of course, we must also recognize that perceptions of the quality of supervi-

sion may be linked to specific high-profile leaders and role models as opposed to systematic

firm-level HR policies.

Second, satisfaction with coworkers can be increased by managing group demography

and social activities to create a team-based work environment (O’Reilly, Caldwell, & Barnett,

1989). As people develop strong relationships within the firm, they are less likely to leave

(Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez, 2001; Shaw, Duffy, Johnson, & Lockhart, 2005).

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Finally, causal ambiguity also can create a retention dilemma. It can increase talent reten-

tion because it is hard for rivals to identify knowledge that specific employees hold and the

relative value of that knowledge. At the same time, however, internal managers may not

know any more about employee skills than their competitors do. In knowledge-intensive

environments, it can be very difficult to identify who knows what and equally difficult to

identify how any one individual’s knowledge connects to performance outcomes. The prob-

lem for the manager, then, is identifying which employees to retain. Recent work by Oettl

(2010) shows that some stars may actually increase productivity more through helping others

than by producing themselves. As such, it may be especially hard to identify these “mavens”

in work environments where helping behaviors are not immediately clear to supervisors and/

or coworkers. For example, Grant Hill is the only person to have won the National Basketball

Association’s (NBA) sportsmanship award three times. While NBA players across the

league have voted repeatedly for Hill, his team-building behaviors may be hard for owners

to observe directly. If firms fail to retain these helpful stars, the firms may lose substantial

sources of economic productivity.

Potential coping strategies for retention dilemmas. One clear possibility for retaining

human capital is simply to pay people enough that they stay (Akerlof, 1984; Weiss, 1990)—

this distributes rent and thereby lowers observed profitability. Beyond this, there is a variety

of alternatives that may promote retention without allocating rent. Drawing from the turn-

over literature, we see that a person’s propensity to change jobs depends on perceptions of

the current job relative to alternatives (Shaw, Delery, Jenkins, & Gupta, 1998). Thus, firms

may decrease turnover by either (1) raising perceptions of the current job or (2) lowering

perceptions of alternatives. These perceptions can be influenced both by managing the non-

financial aspects of job satisfaction and by investing in firm-specific skills.

Firms can raise employee perceptions of the current job by managing the nonfinancial

facets of employee job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is featured prominently in the turnover

literature as a trigger to prompt search behavior (Hom, Caranikas-Walker, Prussia, & Griffeth,

1992; Lee, Mitchell, Wise, & Fireman, 1996). For example, the Job Descriptive Index mea-

sures five dimensions: (1) pay, (2) supervision, (3) coworkers, (4) promotion, and (5) the

work itself (Jung, Dalessio, & Johnson, 1986), and there is evidence that nonfinancial facets

can substitute for wages (Cable & Turban, 2003; Stern, 2004).

The four nonpecuniary dimensions of job satisfaction offer significant opportunities to

retain employees at potentially low cost. These dimensions can be elevated either through

systematic HR policies or through individual-level phenomena. First, firms can improve

satisfaction with supervision by training and selecting managers who provide learning

opportunities, promote employee participation, provide recognition, and promote fairness in

their decisions. Of course, we must also recognize that perceptions of the quality of supervi-

sion may be linked to specific high-profile leaders and role models as opposed to systematic

firm-level HR policies.

Second, satisfaction with coworkers can be increased by managing group demography

and social activities to create a team-based work environment (O’Reilly, Caldwell, & Barnett,

1989). As people develop strong relationships within the firm, they are less likely to leave

(Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez, 2001; Shaw, Duffy, Johnson, & Lockhart, 2005).

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Coff, Kryscynski / Human Capital–Based Advantages 1437

Similarly, individual-level processes may enhance satisfaction with coworkers. For example,

leaders may actively set work group norms that generate satisfaction with the team as a whole.

Third, firms can enhance satisfaction with promotion through HR policies that structure

desirable career paths such that assignments are offered as rewards. This is a consistently

important facet—especially among workers with substantial human capital (Rice, Gentile, &

McFarlin, 1991; Scarpello & Campbell, 1983). At the same time, individual managers may

play a role in framing work assignments as rewards or forms of recognition to employees.

Indeed, small changes in responsibilities may take on symbolic significance depending on

how they are presented.

The last dimension, the work itself, is particularly important to professionals who often

seek autonomy and input (Raelin, 1986)—something that may be inexpensive to provide. In

some cases, jobs are designed through active HR intervention. However, jobs often emerge

and are structured by line managers. As such, individual managers may be in a position to

generate intrinsically rewarding work settings.

In sum, since employees value nonfinancial dimensions of satisfaction, these facets can

substitute for wages while still enhancing retention. Indeed, some have studied the extent to

which attempts to motivate individuals extrinsically (wages, etc.) can crowd out natural

intrinsic motivation (Frey, 1993, 2002; Murdock, 2002). Since these intrinsic facets can be

quite valuable to employees, but inexpensive to maintain (once in place), they may serve as

important components of a sustainable advantage.

In addition to influencing perceptions of their current jobs, firms can affect employee

perceptions of alternative jobs. One way firms may affect employee perceptions of outside

options is by encouraging employees to become embedded in their organizations and com-

munities (Holtom, Mitchell, & Lee, 2006; Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton, & Holtom,

2004). The many links that employees form with other individuals and organizations in their

communities lead to idiosyncratic networks that are, by their very nature, very difficult to

re-create elsewhere. The more embedded employees become, the more likely they are to

believe that they cannot replace these networks should they choose to leave. In other words,

by helping employees to become socially embedded in their organizations and communities,

firms can change employee perceptions of their outside options. The strategic value of

embeddedness is not that employees derive value from their connections but that employees

derive more value from these connections than they think they can find elsewhere. While

embeddedness can emanate from unique HR policies, it may also emanate naturally from

interpersonal relationships or other aspects of organizational life not directly created or bestowed

by the firm and its managers.

Motivating Human Capital

Motivation dilemmas from isolating mechanisms. In addition to having the right human

capital, firms must deal with the complex problems associated with employee motivation.

Just having the right employees in place does not ensure that they will exert sufficient effort

toward essential work tasks. As with attraction and retention, each of the three isolating

mechanisms poses challenges in motivating employees.

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Similarly, individual-level processes may enhance satisfaction with coworkers. For example,

leaders may actively set work group norms that generate satisfaction with the team as a whole.

Third, firms can enhance satisfaction with promotion through HR policies that structure

desirable career paths such that assignments are offered as rewards. This is a consistently

important facet—especially among workers with substantial human capital (Rice, Gentile, &

McFarlin, 1991; Scarpello & Campbell, 1983). At the same time, individual managers may

play a role in framing work assignments as rewards or forms of recognition to employees.

Indeed, small changes in responsibilities may take on symbolic significance depending on

how they are presented.

The last dimension, the work itself, is particularly important to professionals who often

seek autonomy and input (Raelin, 1986)—something that may be inexpensive to provide. In

some cases, jobs are designed through active HR intervention. However, jobs often emerge

and are structured by line managers. As such, individual managers may be in a position to

generate intrinsically rewarding work settings.

In sum, since employees value nonfinancial dimensions of satisfaction, these facets can

substitute for wages while still enhancing retention. Indeed, some have studied the extent to

which attempts to motivate individuals extrinsically (wages, etc.) can crowd out natural

intrinsic motivation (Frey, 1993, 2002; Murdock, 2002). Since these intrinsic facets can be

quite valuable to employees, but inexpensive to maintain (once in place), they may serve as

important components of a sustainable advantage.

In addition to influencing perceptions of their current jobs, firms can affect employee

perceptions of alternative jobs. One way firms may affect employee perceptions of outside

options is by encouraging employees to become embedded in their organizations and com-

munities (Holtom, Mitchell, & Lee, 2006; Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton, & Holtom,

2004). The many links that employees form with other individuals and organizations in their

communities lead to idiosyncratic networks that are, by their very nature, very difficult to

re-create elsewhere. The more embedded employees become, the more likely they are to

believe that they cannot replace these networks should they choose to leave. In other words,

by helping employees to become socially embedded in their organizations and communities,

firms can change employee perceptions of their outside options. The strategic value of

embeddedness is not that employees derive value from their connections but that employees

derive more value from these connections than they think they can find elsewhere. While

embeddedness can emanate from unique HR policies, it may also emanate naturally from

interpersonal relationships or other aspects of organizational life not directly created or bestowed

by the firm and its managers.

Motivating Human Capital

Motivation dilemmas from isolating mechanisms. In addition to having the right human

capital, firms must deal with the complex problems associated with employee motivation.

Just having the right employees in place does not ensure that they will exert sufficient effort

toward essential work tasks. As with attraction and retention, each of the three isolating

mechanisms poses challenges in motivating employees.

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1438 Journal of Management / September 2011

Firm-specificity, the first of the isolating mechanisms, is the focus of a classic human

capital motivation dilemma. Wang and Barney (2006) observe that while firm-specific

human capital may be critical for competitive advantage, employees may be unmotivated to

invest in such skills since they may effectively decrease their opportunities outside of the

firm. All else equal, employees may prefer not to undertake such investments.

Social complexity may pose a different sort of motivational challenge. Complex social

systems engender team production problems by which individual effort and contributions

are hard to observe (Alchian & Demsetz, 1972). This, in turn, makes it hard to rely on pow-

erful incentives and may lead to shirking, poor motivation, or even subversive behavior

(Ouchi, 1980). While these problems are addressed in agency theory (Jensen & Meckling,

1976), the motivation literature also documents reduced effort in some team settings (Kidwell

& Bennett, 1993). When individual contributions are intertwined, employees may be uncer-

tain about whether their efforts will impact outcomes (e.g., expectancy). In addition, the firm

cannot easily provide performance-based rewards (e.g., instrumentality). Finally, individuals

have distinct utility functions such that the value of rewards (valence) varies across people.

If valence, expectancy, and instrumentality are low, it will be hard to motivate employees

(Vroom, 1964).

Similarly, causal ambiguity paves the way for problems of moral hazard. People often

take credit for successes and assign external attributions for failures when it is difficult to

observe causality. Attribution theory refers to this as the “self-serving bias” (Miller & Ross,

1975). Therefore, it may be very hard for managers to recognize what behaviors and/or skills

ought to be rewarded. Since causality cannot be established, organizations may inadvertently

reward or punish employees for events that are beyond the employees’ control or influence

(Kerr, 1975, 1995).

Potential coping strategies for motivation dilemmas. Conventional solutions to the firm-

specific investment problem include offering higher wages to compensate employees for

firm-specific investments or providing contractual assurances of ex post compensation.

There may also be nonpecuniary or intrinsic rewards linked to human capital investments.

For example, socialization research suggests that individuals may actively choose to invest

in firm-specific human capital (Morrison, 1993). That is, people may experience positive util-

ity by matching a group’s norms, values, and culture (Gottschalg & Zollo, 2007; Morrison,

1993)—similar to what Foss (2011) calls a normative frame. Where organizational norms

support investments in firm-specific human capital, some individuals will choose to conform

with expectations. These norms may be reinforced both by HR policies to integrate new

hires and by specific individuals who espouse the norms.

The other motivation dilemmas arise around difficulties in identifying and measuring

individuals’ contributions. In this context, cultural norms may substitute for close monitor-

ing or powerful incentives (Ouchi, 1980). Some aspects of a corporate culture can be encour-

aged and maintained by HR policies and other organization-level routines (Lengnick-Hall &

Lengnick-Hall, 1988; Schein, 2004). For example, recruitment, selection, and recognition

systems can focus on those who espouse the firm’s core values. At the same time, high-profile

individuals who espouse those values may be invaluable and irreplaceable (Meindl, 1989;

Pettigrew, 1979). The idiosyncratic blend of critical individuals with organizational systems

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Firm-specificity, the first of the isolating mechanisms, is the focus of a classic human

capital motivation dilemma. Wang and Barney (2006) observe that while firm-specific

human capital may be critical for competitive advantage, employees may be unmotivated to

invest in such skills since they may effectively decrease their opportunities outside of the

firm. All else equal, employees may prefer not to undertake such investments.

Social complexity may pose a different sort of motivational challenge. Complex social

systems engender team production problems by which individual effort and contributions

are hard to observe (Alchian & Demsetz, 1972). This, in turn, makes it hard to rely on pow-

erful incentives and may lead to shirking, poor motivation, or even subversive behavior

(Ouchi, 1980). While these problems are addressed in agency theory (Jensen & Meckling,

1976), the motivation literature also documents reduced effort in some team settings (Kidwell

& Bennett, 1993). When individual contributions are intertwined, employees may be uncer-

tain about whether their efforts will impact outcomes (e.g., expectancy). In addition, the firm

cannot easily provide performance-based rewards (e.g., instrumentality). Finally, individuals

have distinct utility functions such that the value of rewards (valence) varies across people.

If valence, expectancy, and instrumentality are low, it will be hard to motivate employees

(Vroom, 1964).

Similarly, causal ambiguity paves the way for problems of moral hazard. People often

take credit for successes and assign external attributions for failures when it is difficult to

observe causality. Attribution theory refers to this as the “self-serving bias” (Miller & Ross,

1975). Therefore, it may be very hard for managers to recognize what behaviors and/or skills

ought to be rewarded. Since causality cannot be established, organizations may inadvertently

reward or punish employees for events that are beyond the employees’ control or influence

(Kerr, 1975, 1995).

Potential coping strategies for motivation dilemmas. Conventional solutions to the firm-

specific investment problem include offering higher wages to compensate employees for

firm-specific investments or providing contractual assurances of ex post compensation.

There may also be nonpecuniary or intrinsic rewards linked to human capital investments.

For example, socialization research suggests that individuals may actively choose to invest

in firm-specific human capital (Morrison, 1993). That is, people may experience positive util-

ity by matching a group’s norms, values, and culture (Gottschalg & Zollo, 2007; Morrison,

1993)—similar to what Foss (2011) calls a normative frame. Where organizational norms

support investments in firm-specific human capital, some individuals will choose to conform

with expectations. These norms may be reinforced both by HR policies to integrate new

hires and by specific individuals who espouse the norms.

The other motivation dilemmas arise around difficulties in identifying and measuring

individuals’ contributions. In this context, cultural norms may substitute for close monitor-

ing or powerful incentives (Ouchi, 1980). Some aspects of a corporate culture can be encour-

aged and maintained by HR policies and other organization-level routines (Lengnick-Hall &

Lengnick-Hall, 1988; Schein, 2004). For example, recruitment, selection, and recognition

systems can focus on those who espouse the firm’s core values. At the same time, high-profile

individuals who espouse those values may be invaluable and irreplaceable (Meindl, 1989;

Pettigrew, 1979). The idiosyncratic blend of critical individuals with organizational systems

at UNIV TORONTO on November 23, 2014jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Coff, Kryscynski / Human Capital–Based Advantages 1439

may be a key to understanding why corporate culture holds so much promise as a source of

competitive advantage (Barney, 1986a).

Beyond this, individuals may play an important role in resolving the information asym-

metries that hinder effective reward systems. Performance appraisal data can be gathered

from a wide array of individuals who, in turn, have unique perspectives on each other. Such

360-degree feedback draws on individual variation in information and perspectives and may

therefore help firms craft effective incentives even in the context of social complexity or causal

ambiguity. Additionally, some firms are beginning to utilize social media to allow employ-

ees to nominate others for positive work as a way to better observe and reward performance.

Future Directions and Conclusion

While we agree that human capital provides a promising source of competitive advantage

in the resource-based theory of the firm, we add our voices to those who have called for

stronger micro-foundations for understanding resources and capabilities (Coff, 1997; Felin

& Hesterly, 2007; Foss, 2011; Teece, 2007). Here, we focus specifically on the context of

human capital–based advantages. Beyond our general call for research, we identify several

specific areas we believe will be particularly fruitful. A greater understanding of the micro-

foundations of human capital–based competitive advantage requires further integration of

micro theories of individual motivation and behavior with macro theories explaining firm-

level activities.

Table 1 summarizes our discussion of the role that individual-level differences play in

(1) creating management dilemmas that could hinder the emergence of a competitive advan-

tage and (2) discovering possible solutions to these challenges. This represents a rich set of

opportunities for further research needed to build a more robust theory of human capital–