An Analysis of Malaysia's Middle-Income Challenge (ECN70104)

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/11

|15

|3365

|478

Report

AI Summary

This report delves into Malaysia's persistent struggle to transition from a middle-income to a high-income nation, examining the 'middle-income trap' phenomenon. The analysis begins with an overview of Malaysia's economic evolution since independence, highlighting its shift from a commodity-based economy to a services-oriented one. The report defines the middle-income trap, emphasizing the stagnation experienced by countries like Malaysia that have been unable to achieve high-income status despite initial economic growth. It explores various factors contributing to this trap, including the slow growth of Total Factor Productivity (TFP), insufficient investment in Research & Development (R&D), and a lack of diversification in exports. The paper also references studies comparing Malaysia's economic performance to other East Asian nations and discusses the role of foreign labor and multinational companies. The report further examines the role of innovation, patent applications, and the impact of foreign direct investment. Finally, it suggests potential strategies for Malaysia to overcome these challenges and achieve high-income status. The report uses figures and data from various sources like World Bank and Asian Development Bank to support the arguments.

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

MALAYSIA’ S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

Abstract: -

Malaysia continues to struggle in addressing the identified challenges that are preventing or

delaying the country’s shift from middle-income status to high-income status. Malaysia

transited from lower middle to upper middle income status in 1992 and has been stagnating in

a middle income status for fifty-five (55) years since 1960. The economic resilience of

Malaysia had been continuously challenged by modest levels of income and existing

vulnerabilities to the conditions of global economy. The term ‘middle-income trap’ was first

brought to attention by Gill and Kharas (2007), to highlight growth slowdowns in many East

Asian economies. This paper conducts a review on the existing literatures on the background

of Malaysia’s economy, the definition of Middle-Income Trap (MIT), factors which lead

Malaysia to fall into the middle-income trap and suggested ways to escape the middle-income

trap.

Keywords: - Malaysia, South East Asia, Economic Growth, Middle-Income Trap

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 1

MALAYSIA’ S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

Abstract: -

Malaysia continues to struggle in addressing the identified challenges that are preventing or

delaying the country’s shift from middle-income status to high-income status. Malaysia

transited from lower middle to upper middle income status in 1992 and has been stagnating in

a middle income status for fifty-five (55) years since 1960. The economic resilience of

Malaysia had been continuously challenged by modest levels of income and existing

vulnerabilities to the conditions of global economy. The term ‘middle-income trap’ was first

brought to attention by Gill and Kharas (2007), to highlight growth slowdowns in many East

Asian economies. This paper conducts a review on the existing literatures on the background

of Malaysia’s economy, the definition of Middle-Income Trap (MIT), factors which lead

Malaysia to fall into the middle-income trap and suggested ways to escape the middle-income

trap.

Keywords: - Malaysia, South East Asia, Economic Growth, Middle-Income Trap

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

Introduction

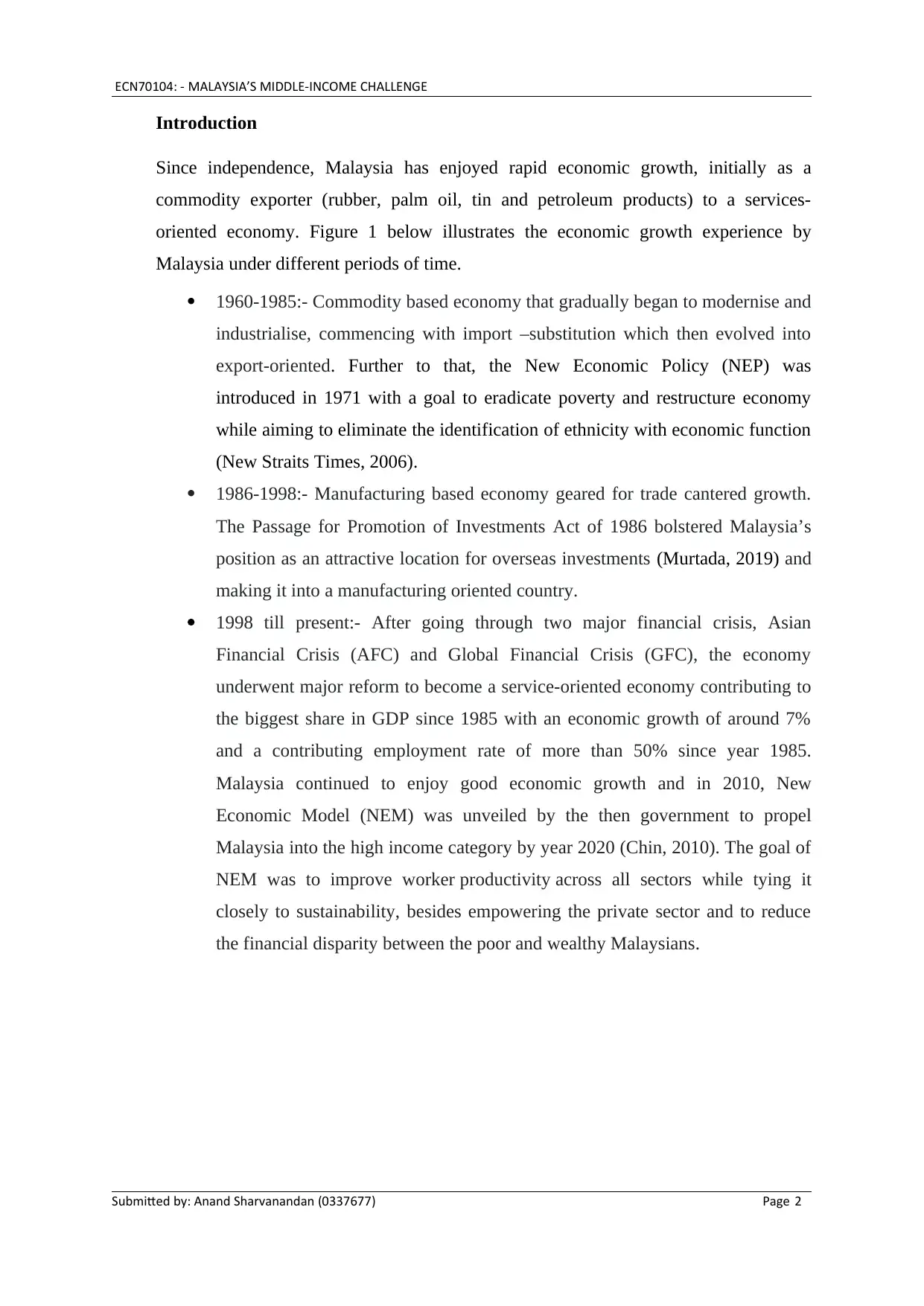

Since independence, Malaysia has enjoyed rapid economic growth, initially as a

commodity exporter (rubber, palm oil, tin and petroleum products) to a services-

oriented economy. Figure 1 below illustrates the economic growth experience by

Malaysia under different periods of time.

1960-1985:- Commodity based economy that gradually began to modernise and

industrialise, commencing with import –substitution which then evolved into

export-oriented. Further to that, the New Economic Policy (NEP) was

introduced in 1971 with a goal to eradicate poverty and restructure economy

while aiming to eliminate the identification of ethnicity with economic function

(New Straits Times, 2006).

1986-1998:- Manufacturing based economy geared for trade cantered growth.

The Passage for Promotion of Investments Act of 1986 bolstered Malaysia’s

position as an attractive location for overseas investments (Murtada, 2019) and

making it into a manufacturing oriented country.

1998 till present:- After going through two major financial crisis, Asian

Financial Crisis (AFC) and Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the economy

underwent major reform to become a service-oriented economy contributing to

the biggest share in GDP since 1985 with an economic growth of around 7%

and a contributing employment rate of more than 50% since year 1985.

Malaysia continued to enjoy good economic growth and in 2010, New

Economic Model (NEM) was unveiled by the then government to propel

Malaysia into the high income category by year 2020 (Chin, 2010). The goal of

NEM was to improve worker productivity across all sectors while tying it

closely to sustainability, besides empowering the private sector and to reduce

the financial disparity between the poor and wealthy Malaysians.

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 2

Introduction

Since independence, Malaysia has enjoyed rapid economic growth, initially as a

commodity exporter (rubber, palm oil, tin and petroleum products) to a services-

oriented economy. Figure 1 below illustrates the economic growth experience by

Malaysia under different periods of time.

1960-1985:- Commodity based economy that gradually began to modernise and

industrialise, commencing with import –substitution which then evolved into

export-oriented. Further to that, the New Economic Policy (NEP) was

introduced in 1971 with a goal to eradicate poverty and restructure economy

while aiming to eliminate the identification of ethnicity with economic function

(New Straits Times, 2006).

1986-1998:- Manufacturing based economy geared for trade cantered growth.

The Passage for Promotion of Investments Act of 1986 bolstered Malaysia’s

position as an attractive location for overseas investments (Murtada, 2019) and

making it into a manufacturing oriented country.

1998 till present:- After going through two major financial crisis, Asian

Financial Crisis (AFC) and Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the economy

underwent major reform to become a service-oriented economy contributing to

the biggest share in GDP since 1985 with an economic growth of around 7%

and a contributing employment rate of more than 50% since year 1985.

Malaysia continued to enjoy good economic growth and in 2010, New

Economic Model (NEM) was unveiled by the then government to propel

Malaysia into the high income category by year 2020 (Chin, 2010). The goal of

NEM was to improve worker productivity across all sectors while tying it

closely to sustainability, besides empowering the private sector and to reduce

the financial disparity between the poor and wealthy Malaysians.

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 2

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

Figure 1: Real GDP and Real Annual Median Income Household Income, 1960-2016 (Malaysia)

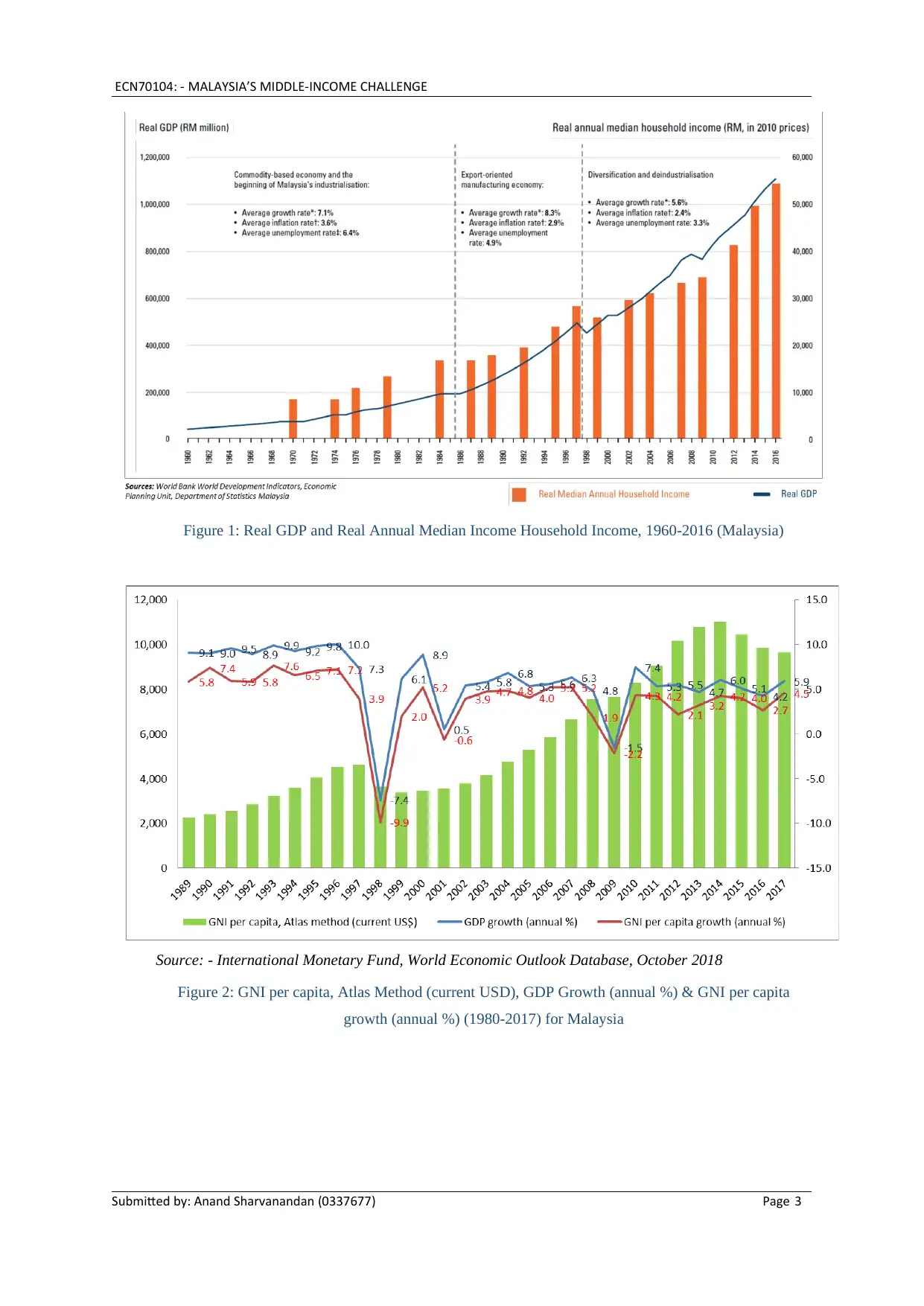

Source: - International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2018

Figure 2: GNI per capita, Atlas Method (current USD), GDP Growth (annual %) & GNI per capita

growth (annual %) (1980-2017) for Malaysia

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 3

Figure 1: Real GDP and Real Annual Median Income Household Income, 1960-2016 (Malaysia)

Source: - International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2018

Figure 2: GNI per capita, Atlas Method (current USD), GDP Growth (annual %) & GNI per capita

growth (annual %) (1980-2017) for Malaysia

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

Countries in the Middle Income Trap

The World Bank estimation in the year 2013 segregated countries into low income

countries and middle income countries. According to the estimation countries having a

per capita gross national income (GNI) of USD 1045 are identified as low income

countries. Countries with a per capita GNI ranging between USD 1045 and 2125 are

classified as lower middle income countries whereas countries with a per capita GNI

lying between USD 4125 and 12,475 are regarded as upper middle income countries.

Some economists researching in the field of economic growth are of the view that

countries belonging to low income group face the fear of falling in poverty trap and

countries belonging to middle income group face the danger of middle-income trap

(Felipe, Kumar and Galope 2017). The situation where middle income nations are stuck

and are unable to make progress towards a high income nation is known as middle-

income trap.

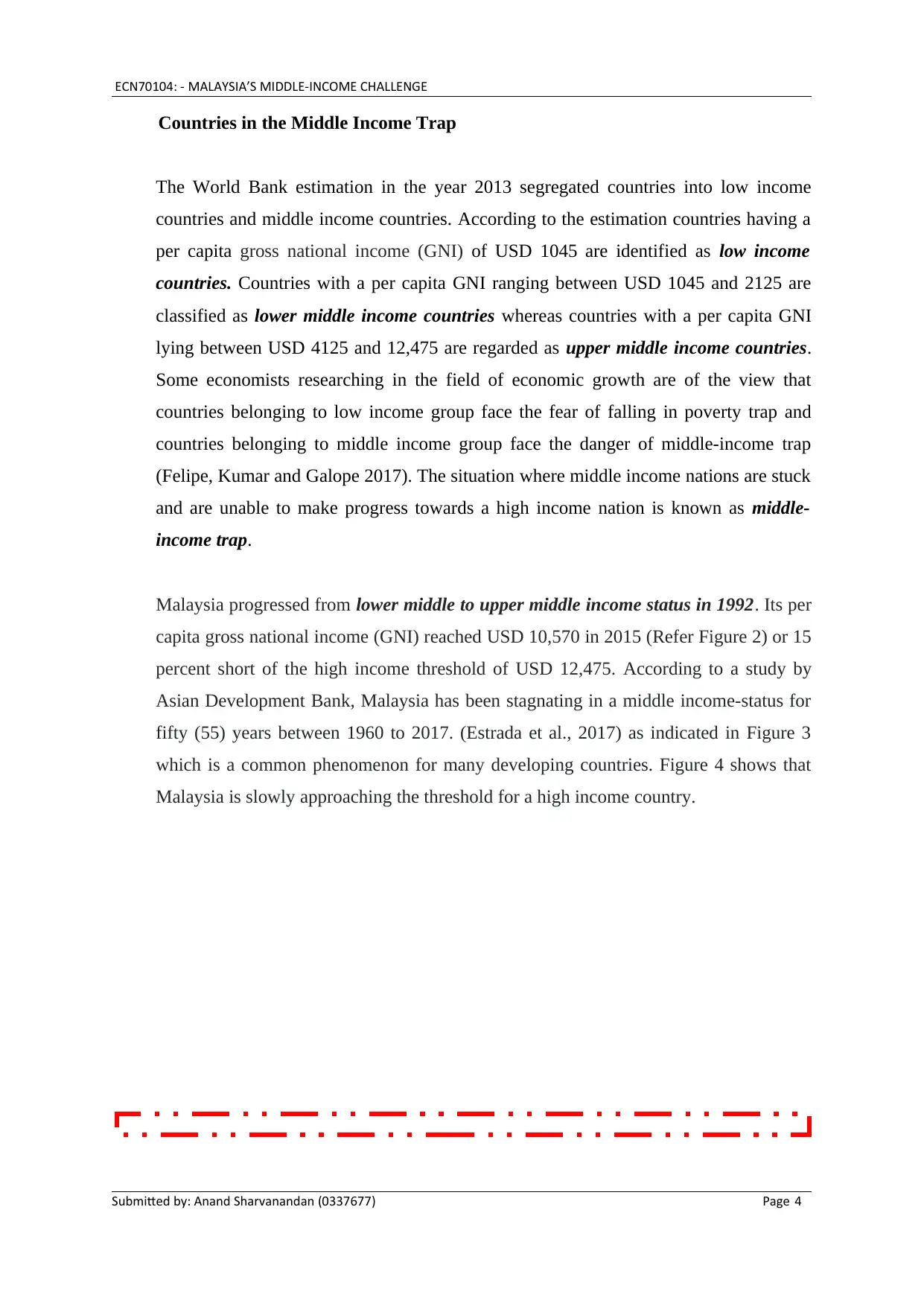

Malaysia progressed from lower middle to upper middle income status in 1992. Its per

capita gross national income (GNI) reached USD 10,570 in 2015 (Refer Figure 2) or 15

percent short of the high income threshold of USD 12,475. According to a study by

Asian Development Bank, Malaysia has been stagnating in a middle income-status for

fifty (55) years between 1960 to 2017. (Estrada et al., 2017) as indicated in Figure 3

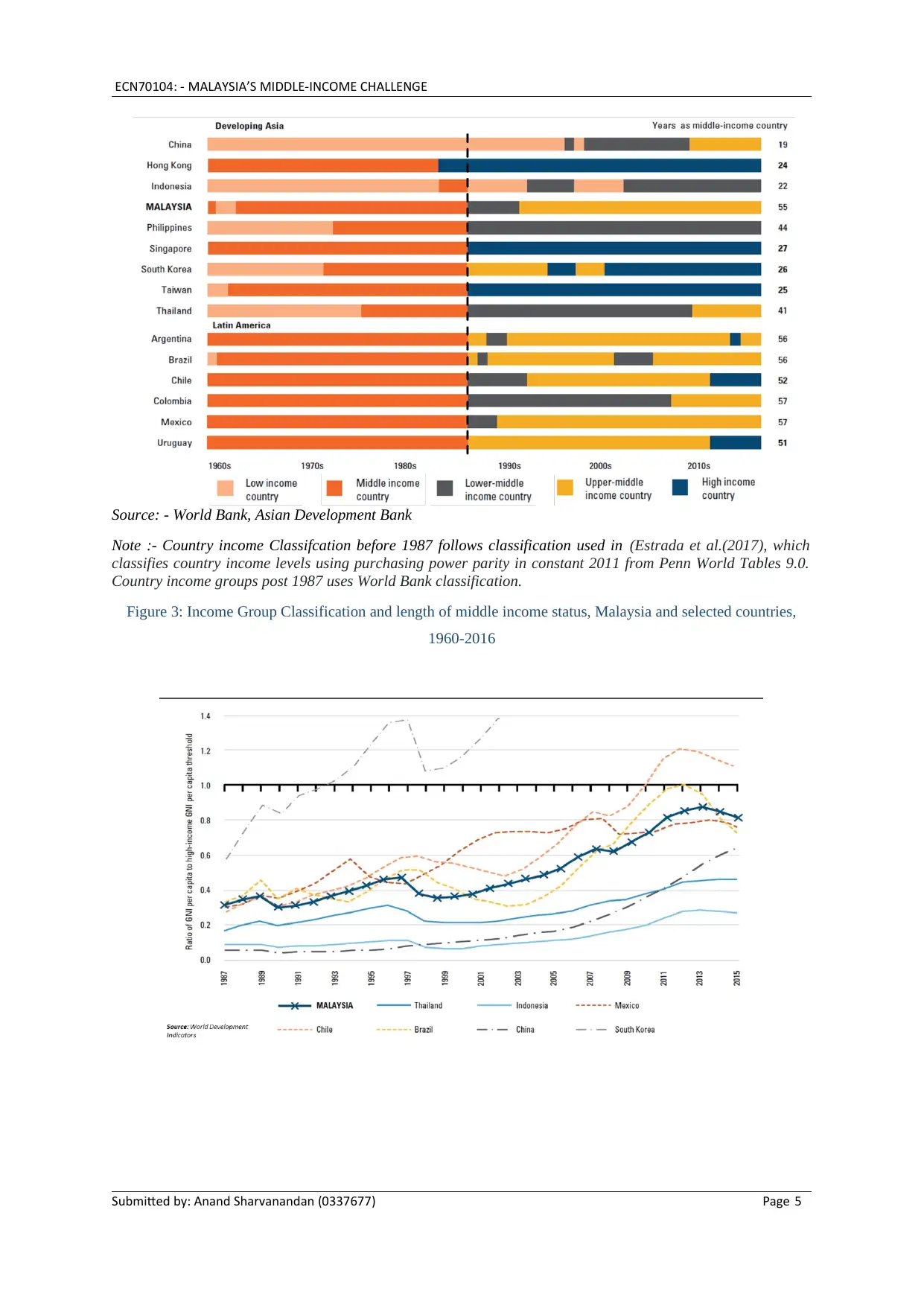

which is a common phenomenon for many developing countries. Figure 4 shows that

Malaysia is slowly approaching the threshold for a high income country.

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 4

Countries in the Middle Income Trap

The World Bank estimation in the year 2013 segregated countries into low income

countries and middle income countries. According to the estimation countries having a

per capita gross national income (GNI) of USD 1045 are identified as low income

countries. Countries with a per capita GNI ranging between USD 1045 and 2125 are

classified as lower middle income countries whereas countries with a per capita GNI

lying between USD 4125 and 12,475 are regarded as upper middle income countries.

Some economists researching in the field of economic growth are of the view that

countries belonging to low income group face the fear of falling in poverty trap and

countries belonging to middle income group face the danger of middle-income trap

(Felipe, Kumar and Galope 2017). The situation where middle income nations are stuck

and are unable to make progress towards a high income nation is known as middle-

income trap.

Malaysia progressed from lower middle to upper middle income status in 1992. Its per

capita gross national income (GNI) reached USD 10,570 in 2015 (Refer Figure 2) or 15

percent short of the high income threshold of USD 12,475. According to a study by

Asian Development Bank, Malaysia has been stagnating in a middle income-status for

fifty (55) years between 1960 to 2017. (Estrada et al., 2017) as indicated in Figure 3

which is a common phenomenon for many developing countries. Figure 4 shows that

Malaysia is slowly approaching the threshold for a high income country.

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

Source: - World Bank, Asian Development Bank

Note :- Country income Classifcation before 1987 follows classification used in (Estrada et al.(2017), which

classifies country income levels using purchasing power parity in constant 2011 from Penn World Tables 9.0.

Country income groups post 1987 uses World Bank classification.

Figure 3: Income Group Classification and length of middle income status, Malaysia and selected countries,

1960-2016

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 5

Source: - World Bank, Asian Development Bank

Note :- Country income Classifcation before 1987 follows classification used in (Estrada et al.(2017), which

classifies country income levels using purchasing power parity in constant 2011 from Penn World Tables 9.0.

Country income groups post 1987 uses World Bank classification.

Figure 3: Income Group Classification and length of middle income status, Malaysia and selected countries,

1960-2016

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 5

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

Source: - World Development Indicators

Figure 4: Distance to High Income Country Threshold, 1987-2016

Source: - Felipe, J., Kumar, U. and Galope, R. (2014). Middle-Income Transitions: Trap or Myth. SSRN

Electronic Journal.

Figure 5: Distribution of economies by income categories, 1950–2013.

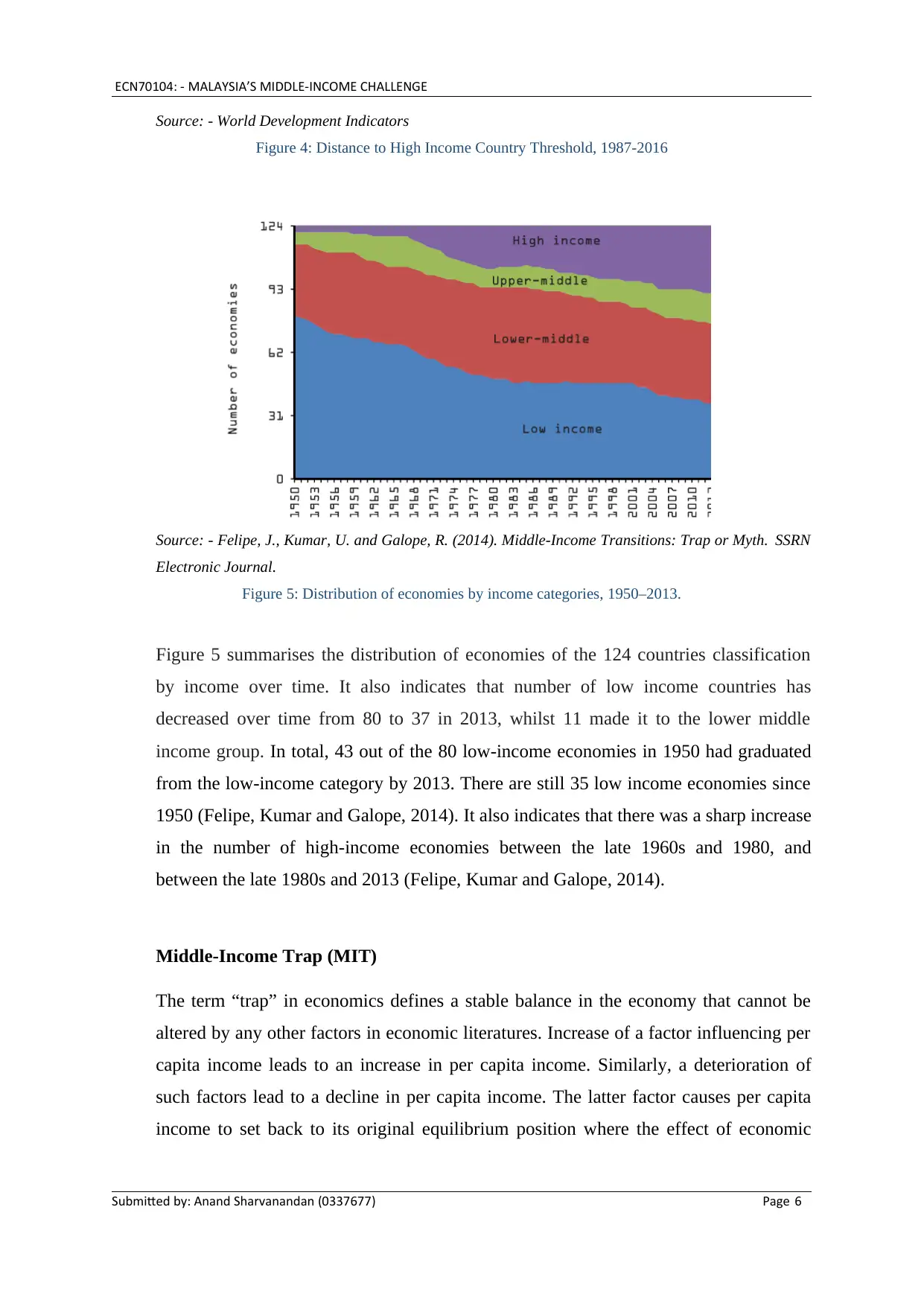

Figure 5 summarises the distribution of economies of the 124 countries classification

by income over time. It also indicates that number of low income countries has

decreased over time from 80 to 37 in 2013, whilst 11 made it to the lower middle

income group. In total, 43 out of the 80 low-income economies in 1950 had graduated

from the low-income category by 2013. There are still 35 low income economies since

1950 (Felipe, Kumar and Galope, 2014). It also indicates that there was a sharp increase

in the number of high-income economies between the late 1960s and 1980, and

between the late 1980s and 2013 (Felipe, Kumar and Galope, 2014).

Middle-Income Trap (MIT)

The term “trap” in economics defines a stable balance in the economy that cannot be

altered by any other factors in economic literatures. Increase of a factor influencing per

capita income leads to an increase in per capita income. Similarly, a deterioration of

such factors lead to a decline in per capita income. The latter factor causes per capita

income to set back to its original equilibrium position where the effect of economic

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 6

Source: - World Development Indicators

Figure 4: Distance to High Income Country Threshold, 1987-2016

Source: - Felipe, J., Kumar, U. and Galope, R. (2014). Middle-Income Transitions: Trap or Myth. SSRN

Electronic Journal.

Figure 5: Distribution of economies by income categories, 1950–2013.

Figure 5 summarises the distribution of economies of the 124 countries classification

by income over time. It also indicates that number of low income countries has

decreased over time from 80 to 37 in 2013, whilst 11 made it to the lower middle

income group. In total, 43 out of the 80 low-income economies in 1950 had graduated

from the low-income category by 2013. There are still 35 low income economies since

1950 (Felipe, Kumar and Galope, 2014). It also indicates that there was a sharp increase

in the number of high-income economies between the late 1960s and 1980, and

between the late 1980s and 2013 (Felipe, Kumar and Galope, 2014).

Middle-Income Trap (MIT)

The term “trap” in economics defines a stable balance in the economy that cannot be

altered by any other factors in economic literatures. Increase of a factor influencing per

capita income leads to an increase in per capita income. Similarly, a deterioration of

such factors lead to a decline in per capita income. The latter factor causes per capita

income to set back to its original equilibrium position where the effect of economic

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

growth ultimately turns out to be zero (Eryılmaz and Eryılmaz 2015). The term

‘middle-income trap’ was first brought to attention by Gill and Kharas (2007), to

highlight growth slowdowns in many East Asian economies. These countries

experienced rapid growth, enabling them to reach the middle income status but have

not been able to catch up with developed countries and achieve high income status (Gill

and Kharas, 2007). When a country in stuck in between a low wage poor country which

dominates in mature industries and a rich country which dominates in rapid

technological change industries, that country can also be characterised as a Middle

Income Trap country (Gill and Kharas, 2007).

MIT also refers to a situation in which a middle-income country (MIC) falls into

economic stagnation and becomes unable to advance its economy to a high-income

level for certain reasons specific to MICs (Egawa, 2013). Egawa (2013) further

suggests that a delay or failure to change the economic structure from an input driven

growth model into a productivity-driven growth model is a factor in triggering the risk

of a MIT. Glawe and Wagner, 2016 states as per definition, the Middle Income Trap is

seen as sustained slowdown of growth for at least fifty (50) years.

Causes of Middle Income Trap in Malaysia

There are several factors that have contributed to the persistent problem of middle-

income trap in Malaysia as discussed below.

Total Factor Productivity (TFP) is commonly referred so as a measure for technological

progress. It incorporates the impact of technological change and other factors that rise

further than the quantified contribution of factor accumulation (Solow, 1957). Various

studies have been carried out to identify the role of TFP in economic growth dynamics

of the country. Eichengreen, Park and Shin (2012) compared the experience of middle

income countries that successfully moved to high income with that those that were

unable to do so. They found that whole physical and human capital played a similar

role, labour played a less role for the economy to grow and transition to a high income.

(Kim and Park, 2018). TFP growth was found slower and accounted for much lower

share to the GDP for Middle Income Trapped Countries. TFP growth in Malaysia

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 7

growth ultimately turns out to be zero (Eryılmaz and Eryılmaz 2015). The term

‘middle-income trap’ was first brought to attention by Gill and Kharas (2007), to

highlight growth slowdowns in many East Asian economies. These countries

experienced rapid growth, enabling them to reach the middle income status but have

not been able to catch up with developed countries and achieve high income status (Gill

and Kharas, 2007). When a country in stuck in between a low wage poor country which

dominates in mature industries and a rich country which dominates in rapid

technological change industries, that country can also be characterised as a Middle

Income Trap country (Gill and Kharas, 2007).

MIT also refers to a situation in which a middle-income country (MIC) falls into

economic stagnation and becomes unable to advance its economy to a high-income

level for certain reasons specific to MICs (Egawa, 2013). Egawa (2013) further

suggests that a delay or failure to change the economic structure from an input driven

growth model into a productivity-driven growth model is a factor in triggering the risk

of a MIT. Glawe and Wagner, 2016 states as per definition, the Middle Income Trap is

seen as sustained slowdown of growth for at least fifty (50) years.

Causes of Middle Income Trap in Malaysia

There are several factors that have contributed to the persistent problem of middle-

income trap in Malaysia as discussed below.

Total Factor Productivity (TFP) is commonly referred so as a measure for technological

progress. It incorporates the impact of technological change and other factors that rise

further than the quantified contribution of factor accumulation (Solow, 1957). Various

studies have been carried out to identify the role of TFP in economic growth dynamics

of the country. Eichengreen, Park and Shin (2012) compared the experience of middle

income countries that successfully moved to high income with that those that were

unable to do so. They found that whole physical and human capital played a similar

role, labour played a less role for the economy to grow and transition to a high income.

(Kim and Park, 2018). TFP growth was found slower and accounted for much lower

share to the GDP for Middle Income Trapped Countries. TFP growth in Malaysia

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

averaged 1.8 percent, compared to 2.2 percent in Korea and Singapore. Similarly, while

labour productivity growth in Malaysia has been fairly stable and more robust than in

other emerging economies, however it has failed to keep pace with growth rates in

Hong Kong, Korea, and Singapore (World Bank, 2019). Currently, Malaysia has a high

proportion of foreign works, mostly from Bangladesh and Indonesia, working in the

manufacturing sector and migrant workers hardly contributed to the improvement of

labour productivity due to their unstable working status and short-term employment

contracts. The percentage of foreign workers rose from a mere 2% in 1990 to 21% in

2004 and exceeded 28% in 2008 (Tham and Loke, 2011). Having such a high number

of migrant workers also meant wages are suppressed as they are willing to work longer

hours for a lower wage.

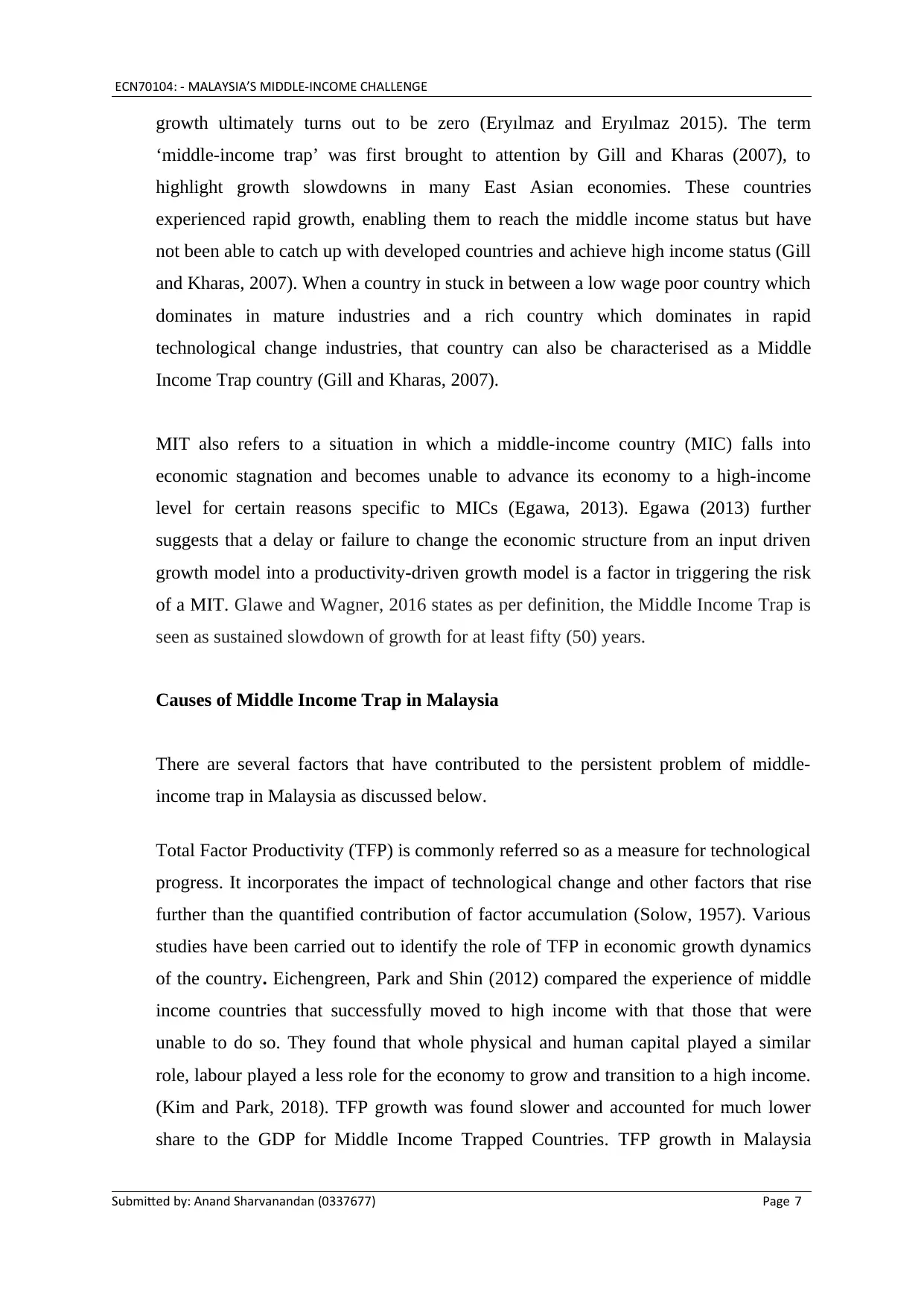

Innovation plays a vital role in spurring economic growth and Research &

Development (R&D) is one of the key indicators of a knowledge creation society and

investment in innovative activities. For example, Malaysia has invested only 0.7% of

its GDP into Research and Development (R&D) as compared to other East Asian nation

like South Korea which spent 3.4% of its GDP for R&D purposes. Multinational

companies (MNCs) provide instant capital, expertise and technology but they do not get

involved in developing or improving Malaysia’s products. Malaysia has been very

comfortable in servicing the MNCs and maintaining the assembly based business

model. It can be said that the local innovations are quite weak in nature and also, there

is little demand from local companies for innovation. The innovation in technologies

also requires huge research teams which the Malaysia firms cannot mobilize.

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 8

averaged 1.8 percent, compared to 2.2 percent in Korea and Singapore. Similarly, while

labour productivity growth in Malaysia has been fairly stable and more robust than in

other emerging economies, however it has failed to keep pace with growth rates in

Hong Kong, Korea, and Singapore (World Bank, 2019). Currently, Malaysia has a high

proportion of foreign works, mostly from Bangladesh and Indonesia, working in the

manufacturing sector and migrant workers hardly contributed to the improvement of

labour productivity due to their unstable working status and short-term employment

contracts. The percentage of foreign workers rose from a mere 2% in 1990 to 21% in

2004 and exceeded 28% in 2008 (Tham and Loke, 2011). Having such a high number

of migrant workers also meant wages are suppressed as they are willing to work longer

hours for a lower wage.

Innovation plays a vital role in spurring economic growth and Research &

Development (R&D) is one of the key indicators of a knowledge creation society and

investment in innovative activities. For example, Malaysia has invested only 0.7% of

its GDP into Research and Development (R&D) as compared to other East Asian nation

like South Korea which spent 3.4% of its GDP for R&D purposes. Multinational

companies (MNCs) provide instant capital, expertise and technology but they do not get

involved in developing or improving Malaysia’s products. Malaysia has been very

comfortable in servicing the MNCs and maintaining the assembly based business

model. It can be said that the local innovations are quite weak in nature and also, there

is little demand from local companies for innovation. The innovation in technologies

also requires huge research teams which the Malaysia firms cannot mobilize.

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 8

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

Source: - Global Innovation Index

Figure 6: Gross Expenditure on R&D (Selected Countries- 2015)

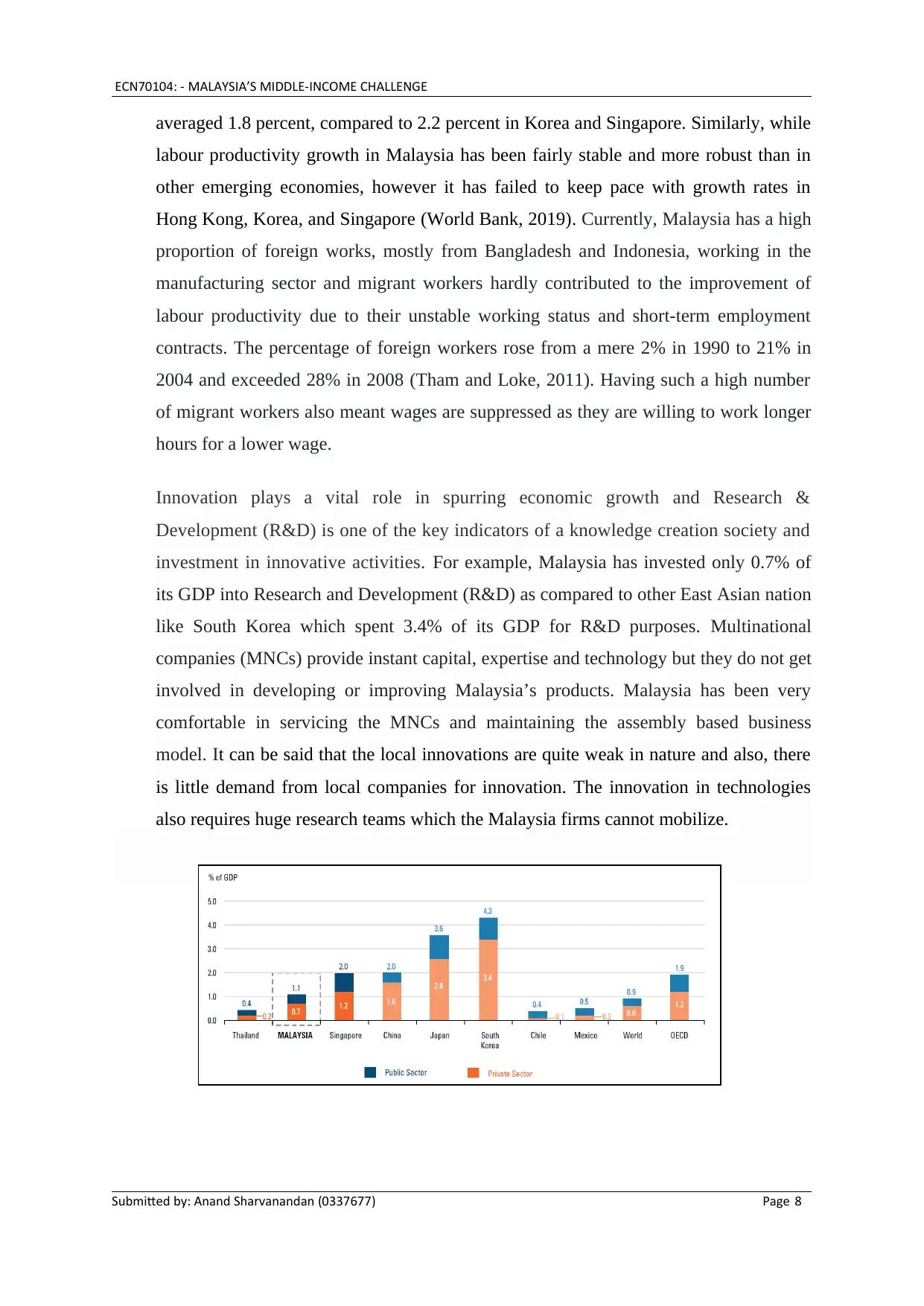

Another key indicator for innovation are patent applications, which indicates the ability to

transform ideas into actual products. Malaysia patent applications are significantly lower

compared to high income countries.

Source: - Global Innovation Index

Figure 7: Gross Expenditure on R&D (Selected Countries- 2015)

Shahid Yusuf in his paper “Can Malaysia escape the middle-income trap?” states that Penang

had been successful in attracting foreign direct investments in the electronic industry, the

foreign detect investment had enabled Penang to become a manufacturing hub specializing in

electronics as well as electrical machinery (Yusuf, 2017). Although electronics has emerged

as the strength of the city, it can be said that the product space analysis does not support the

case for high tech development other than the electronics. Also, the absence of the local

industries also plays an important role. Malaysia failed to diversify its exports to other high-

value added export products, partially due to the fact that personnel was not trained enough to

develop new technologies and new products (Yusuf and Nabeshima, 2009). The electric and

electronic sectors which grew into a large industry, drove the Malaysian economy and

accounted for more than 70% of manufactured exports and more than 50% of total experts by

the end of 1990s. The pain was felt after several big players i.e. Seagate, Intel, Motorola and

Dell either closed their plants or shrunk their operations (Yusuf, 2003).

Under the Control Act 1961, subsidy was implemented for items such as petrol, gas, rice,

sugar, salt and other essential commodity items. These subsidies have increased government

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 9

Source: - Global Innovation Index

Figure 6: Gross Expenditure on R&D (Selected Countries- 2015)

Another key indicator for innovation are patent applications, which indicates the ability to

transform ideas into actual products. Malaysia patent applications are significantly lower

compared to high income countries.

Source: - Global Innovation Index

Figure 7: Gross Expenditure on R&D (Selected Countries- 2015)

Shahid Yusuf in his paper “Can Malaysia escape the middle-income trap?” states that Penang

had been successful in attracting foreign direct investments in the electronic industry, the

foreign detect investment had enabled Penang to become a manufacturing hub specializing in

electronics as well as electrical machinery (Yusuf, 2017). Although electronics has emerged

as the strength of the city, it can be said that the product space analysis does not support the

case for high tech development other than the electronics. Also, the absence of the local

industries also plays an important role. Malaysia failed to diversify its exports to other high-

value added export products, partially due to the fact that personnel was not trained enough to

develop new technologies and new products (Yusuf and Nabeshima, 2009). The electric and

electronic sectors which grew into a large industry, drove the Malaysian economy and

accounted for more than 70% of manufactured exports and more than 50% of total experts by

the end of 1990s. The pain was felt after several big players i.e. Seagate, Intel, Motorola and

Dell either closed their plants or shrunk their operations (Yusuf, 2003).

Under the Control Act 1961, subsidy was implemented for items such as petrol, gas, rice,

sugar, salt and other essential commodity items. These subsidies have increased government

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

spending and have become too heavy for the ruling government to continue to bear the cost.

In addition, subsidies have also restrained the government’s ability to invest more in R&D

sector or in upgrading the infrastructure; which is crucial to have a competitive edge and to

increase productivity.

Many Malaysians are now living and working abroad and this has caused a phenomenon

called ‘Brain Drain’ in the country whereby the nation is lacking or losing highly educated

and highly skilled workers to foreign countries. This phenomenon happened due to two main

reasons: a) the lack of strong higher education system in the country, b) silent dissatisfaction

of ethnic Chinese and Indian towards the NEP program which favours the Bumiputras.

Escape from the Middle Income

It is evident that Malaysia is trying to move from a middle income economy to a high income

economy. There are several clear measures which need to be undertaken for Malaysia to

come out of this middle-income trap phenomenon.

The country needs to build up its domestic firm capabilities to produce and export. When

sustainable growth is achieved, living standards in the nation and productivity increases. One

way of doing this is by entering a sector with little comparative advantage, lack of skills,

resources and experience and have a relatively high risk of losing money. However, in the

long run, these sectors are the same sectors which are able to catapult the nation into a high

income status when the sector offers high returns. We can quote Toyota as an example here;

before its heydays, when it had not been profitable for 30 years. (Chang and Lin, 2009).

Malaysia needs to invest more on its own research and development. The country’s R&D is

still significantly low compared to other high income countries in the region. Malaysia, a

country rich in natural resources can use these same natural resources as a way to propel itself

into R&D advancement. Close collaboration can be explored with universities or companies

in order to gain valuable knowledge which can later be used in spearheading an R&D

projects in the country.

While a country moves through stages of development, middle-income trap occurs when

productivity slows down as achievements from low cost labour and foreign technology

imitation diminishes. In order to avoid or move away from this effect, the country needs to

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 10

spending and have become too heavy for the ruling government to continue to bear the cost.

In addition, subsidies have also restrained the government’s ability to invest more in R&D

sector or in upgrading the infrastructure; which is crucial to have a competitive edge and to

increase productivity.

Many Malaysians are now living and working abroad and this has caused a phenomenon

called ‘Brain Drain’ in the country whereby the nation is lacking or losing highly educated

and highly skilled workers to foreign countries. This phenomenon happened due to two main

reasons: a) the lack of strong higher education system in the country, b) silent dissatisfaction

of ethnic Chinese and Indian towards the NEP program which favours the Bumiputras.

Escape from the Middle Income

It is evident that Malaysia is trying to move from a middle income economy to a high income

economy. There are several clear measures which need to be undertaken for Malaysia to

come out of this middle-income trap phenomenon.

The country needs to build up its domestic firm capabilities to produce and export. When

sustainable growth is achieved, living standards in the nation and productivity increases. One

way of doing this is by entering a sector with little comparative advantage, lack of skills,

resources and experience and have a relatively high risk of losing money. However, in the

long run, these sectors are the same sectors which are able to catapult the nation into a high

income status when the sector offers high returns. We can quote Toyota as an example here;

before its heydays, when it had not been profitable for 30 years. (Chang and Lin, 2009).

Malaysia needs to invest more on its own research and development. The country’s R&D is

still significantly low compared to other high income countries in the region. Malaysia, a

country rich in natural resources can use these same natural resources as a way to propel itself

into R&D advancement. Close collaboration can be explored with universities or companies

in order to gain valuable knowledge which can later be used in spearheading an R&D

projects in the country.

While a country moves through stages of development, middle-income trap occurs when

productivity slows down as achievements from low cost labour and foreign technology

imitation diminishes. In order to avoid or move away from this effect, the country needs to

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

innovate; it needs to create new ideas, methods, processes and technologies in production

rather than relying on imitation and Malaysia needs to do more of this (Aghion and Hewiit,

1992).

Malaysia’s tertiary education system needs to be improved whereby higher learning institutes

should engage in frequent partnerships with the industrial sector in order for its students to

gain hands-on knowledge. An example of this is the recent Memorandum of Understanding

(MOU) signed between HSS Engineers Berhad and University Malaysia Sabah in where

students are placed in HSS Engineers Berhad for industrial training. In addition, the

Government should implement initiatives to increase access to Technical and Vocational

Education Training (TVET) as Malaysia gears towards becoming a high income nation.

Malaysia needs to find a way to diversify its source of funds. Instead of seeing Foreign Direct

Investment (FDI) as mainly the source of income for the country, it should be seen as a way

to create jobs and improve local skills by emphasizing that skill creation is the main spill over

from foreign firms to the domestic economy.

Word Count: 2487

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 11

innovate; it needs to create new ideas, methods, processes and technologies in production

rather than relying on imitation and Malaysia needs to do more of this (Aghion and Hewiit,

1992).

Malaysia’s tertiary education system needs to be improved whereby higher learning institutes

should engage in frequent partnerships with the industrial sector in order for its students to

gain hands-on knowledge. An example of this is the recent Memorandum of Understanding

(MOU) signed between HSS Engineers Berhad and University Malaysia Sabah in where

students are placed in HSS Engineers Berhad for industrial training. In addition, the

Government should implement initiatives to increase access to Technical and Vocational

Education Training (TVET) as Malaysia gears towards becoming a high income nation.

Malaysia needs to find a way to diversify its source of funds. Instead of seeing Foreign Direct

Investment (FDI) as mainly the source of income for the country, it should be seen as a way

to create jobs and improve local skills by emphasizing that skill creation is the main spill over

from foreign firms to the domestic economy.

Word Count: 2487

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 11

ECN70104: - MALAYSIA’S MIDDLE-INCOME CHALLENGE

References

Adb.org. (2019). [online] Available at:

https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/237761/ado-2017.pdf [Accessed 17 Mar.

2019].

Aghion, P. and Howitt, P. (1992). A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction.

Econometrica, 60(2), p.323.

Annamalah, S., Munusamy, J. and Sentosa, I. (2016). Middle Income Trap Economies, the

Way Forward in Malaysia. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Global Innovation Index, (2019). [online] Available at:

https://www.globalinnovationindex.org/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

Asian Development Bank. (2019). Asian Development Bank. [online] Available at:

https://www.adb.org/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

Asian development outlook 2017 update. (2017). [Manila]: Asian Development Bank.

Bezemer, D. (2008). An East Asian Renaissance: ideas for economic growth - by Homi

Kharas & Indermit Gill. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature, 22(2), pp.57-59.

Bnm.gov.my. (2019). [online] Available at:

http://www.bnm.gov.my/files/publication/qb/2017/Q1/p3.pdf [Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 12

References

Adb.org. (2019). [online] Available at:

https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/237761/ado-2017.pdf [Accessed 17 Mar.

2019].

Aghion, P. and Howitt, P. (1992). A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction.

Econometrica, 60(2), p.323.

Annamalah, S., Munusamy, J. and Sentosa, I. (2016). Middle Income Trap Economies, the

Way Forward in Malaysia. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Global Innovation Index, (2019). [online] Available at:

https://www.globalinnovationindex.org/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

Asian Development Bank. (2019). Asian Development Bank. [online] Available at:

https://www.adb.org/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

Asian development outlook 2017 update. (2017). [Manila]: Asian Development Bank.

Bezemer, D. (2008). An East Asian Renaissance: ideas for economic growth - by Homi

Kharas & Indermit Gill. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature, 22(2), pp.57-59.

Bnm.gov.my. (2019). [online] Available at:

http://www.bnm.gov.my/files/publication/qb/2017/Q1/p3.pdf [Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

Submitted by: Anand Sharvanandan (0337677) Page 12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 15

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.