Effectiveness of Structured Hourly Nurse | Report

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/04

|7

|4692

|24

Assignment

AI Summary

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

LWW/JNCQ JNCQ-D-14-00043 January 31, 2015 17:46

J Nurs Care Qual

Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 153–159

Copyrightc 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Effectiveness of Structured

Hourly Nurse Rounding on

Patient Satisfaction and Clinical

Outcomes

Lisa A. Brosey, DNP, RN, CPHQ;

Karen S. March, PhD, RN, ACNS-BC

Structured hourly nurse rounding is an effective method to improve patient satisfaction and clin-

icaloutcomes.This program evaluation describes outcomes related to the implementation of

hourly nurse rounding in one medical-surgical unit in a large community hospital. Overall Hospital

Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems domain scores increased with the ex-

ception of responsiveness of staff. Patient falls and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers decreased dur-

ing the project period. Key words: accidental falls, evidence-based nursing/standards, hourly

rounding, PARiHS framework, patient satisfaction, pressure ulcer/prevention and control

ACUTE CARE FACILITIES continue to eval-

uate cost-effectiveness methodsto en-

hance patient satisfaction and improve patient

safety.A growing body of evidence describ-

ing the positive effects ofstructured nurse

rounding on patient satisfaction and clinical

outcomes has emerged within the past few

years.1−25 On the basis of this emerging evi-

dence and the positive effects demonstrated,

many organizations in the United States and

Author Affiliations: Lancaster General Health,

Lancaster, Pennsylvania (Dr Brosey), and The

Stabler Department of Nursing, York College of

Pennsylvania, York (Dr March).

No funding was received for this work.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are

provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article

on the journal’s Web site (www.jncqjournal.com).

Correspondence:Lisa A. Brosey,DNP, RN, CPHQ,

Lancaster General Health, Lancaster, PA 17604

(labrosey@lghealth.org).

Accepted for publication: July 19, 2014

Published online before print: September 18, 2014

DOI: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000086

the United Kingdom have instituted hourly

nurse rounding as a standard component of

nursing practice in an attempt to improve pa-

tientsatisfaction and reduce patientharm.*

Hourly nurse rounding entails assessment of

3 to 12 elements on each patient every hour

between 6AMto 10PMand then every 2 hours

from 10PMto 6AM.1,6,9 Rounds are reduced

to every 2 hours during the night so that sleep

patterns are less disturbed and patients are not

awakened unnecessarily.

The most noted elementsassessed dur-

ing hourly nurse roundinginclude pain

level, need for toileting or elimination,

assessmentof the environmentincluding

room temperature,proximityof personal

items, safety hazards,and positioningof

the patientor need to change the patient’s

position.1,2,4,6,7,9,11−21,23−25

Studies on hourly

nurse rounding reveal that patients re-

port higherpatientsatisfaction,fewer pa-

tient falls and hospital-acquiredpressure

ulcers (HAPUs),and decreasedcall bell

activation.1−22,24,25Evidence further suggests

*References1 ,3 ,6 ,7 ,10-13,16, 17, 20-22.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

153

J Nurs Care Qual

Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 153–159

Copyrightc 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Effectiveness of Structured

Hourly Nurse Rounding on

Patient Satisfaction and Clinical

Outcomes

Lisa A. Brosey, DNP, RN, CPHQ;

Karen S. March, PhD, RN, ACNS-BC

Structured hourly nurse rounding is an effective method to improve patient satisfaction and clin-

icaloutcomes.This program evaluation describes outcomes related to the implementation of

hourly nurse rounding in one medical-surgical unit in a large community hospital. Overall Hospital

Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems domain scores increased with the ex-

ception of responsiveness of staff. Patient falls and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers decreased dur-

ing the project period. Key words: accidental falls, evidence-based nursing/standards, hourly

rounding, PARiHS framework, patient satisfaction, pressure ulcer/prevention and control

ACUTE CARE FACILITIES continue to eval-

uate cost-effectiveness methodsto en-

hance patient satisfaction and improve patient

safety.A growing body of evidence describ-

ing the positive effects ofstructured nurse

rounding on patient satisfaction and clinical

outcomes has emerged within the past few

years.1−25 On the basis of this emerging evi-

dence and the positive effects demonstrated,

many organizations in the United States and

Author Affiliations: Lancaster General Health,

Lancaster, Pennsylvania (Dr Brosey), and The

Stabler Department of Nursing, York College of

Pennsylvania, York (Dr March).

No funding was received for this work.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are

provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article

on the journal’s Web site (www.jncqjournal.com).

Correspondence:Lisa A. Brosey,DNP, RN, CPHQ,

Lancaster General Health, Lancaster, PA 17604

(labrosey@lghealth.org).

Accepted for publication: July 19, 2014

Published online before print: September 18, 2014

DOI: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000086

the United Kingdom have instituted hourly

nurse rounding as a standard component of

nursing practice in an attempt to improve pa-

tientsatisfaction and reduce patientharm.*

Hourly nurse rounding entails assessment of

3 to 12 elements on each patient every hour

between 6AMto 10PMand then every 2 hours

from 10PMto 6AM.1,6,9 Rounds are reduced

to every 2 hours during the night so that sleep

patterns are less disturbed and patients are not

awakened unnecessarily.

The most noted elementsassessed dur-

ing hourly nurse roundinginclude pain

level, need for toileting or elimination,

assessmentof the environmentincluding

room temperature,proximityof personal

items, safety hazards,and positioningof

the patientor need to change the patient’s

position.1,2,4,6,7,9,11−21,23−25

Studies on hourly

nurse rounding reveal that patients re-

port higherpatientsatisfaction,fewer pa-

tient falls and hospital-acquiredpressure

ulcers (HAPUs),and decreasedcall bell

activation.1−22,24,25Evidence further suggests

*References1 ,3 ,6 ,7 ,10-13,16, 17, 20-22.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

153

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

LWW/JNCQ JNCQ-D-14-00043 January 31, 2015 17:46

154 JOURNAL OFNURSINGCAREQUALITY/APRIL–JUNE2015

that nursingcare stronglycontributesto

patients’perceptionsof overallsatisfaction

and likelihood to recommend a facility to

others.26−30 SupplementalDigitalContent,

Table (availableat: http://links.lww.com/

JNCQ/A126),provides a summary of studies

on the effects of structured nurse rounding on

patient satisfaction,patient falls,HAPU,and

call light usage.

LOCAL PROBLEM

The project facilityadopted structured

hourly nurse rounding as a standard of nurs-

ing care in 2008;however,there was little

structure to and accountability for implemen-

tation of this practice. As a result, past efforts

with hourly nurse rounding were inconsistent

and ineffective. Discussions with the nursing

staff and observation of practice revealed min-

imal compliance with hourly nurse rounding

processor the intentto assesspain, elim-

ination,environment,and position (PEEP)

proactively in the current day. Therefore, the

projectleadermet with nursing leadership

to present current evidence and benefits as-

sociated with thisintervention and to gar-

ner support for implementation on one pilot

unit. The project unit was a 24-bed medical-

surgical nursing unit with private and semipri-

vate rooms. This unit was selected on the basis

of its need for improvement in patient satisfac-

tion scores (lowest rating of medical-surgical

units in facility) as well as its higher incidence

of patient falls (2 times the national mean) and

HAPUs (higher than facility mean).

Intended improvement/study question

The purpose of this project was to imple-

ment a standardized structured hourly nurse

rounding processand to monitorthe out-

comes of patient satisfaction, patient falls, and

HAPUs over a 3-month time period.

METHODS

Setting

Promoting Action on Research Implemen-

tation in Health Services(PARiHS)frame-

work was the translation model used for the

project.31 This framework isbased on the

premise that successful implementation of ev-

idence into practice is dependent on 3 fac-

tors:evidence,context or environment,and

facilitation. Each factor has equal importance

in the implementation process and is interre-

lated with other factors.For example,if the

evidence is strong and the environment is ac-

cessible to change, then the facilitation of the

change process willbe less rigorous and de-

manding.In contrast,if the evidence is not

strong and the environment is not adaptive to

change,the facilitation process may require

a higher levelof supportand change man-

agement skills for successful implementation

to occur. The framework requires evaluation

and presentation of the supporting evidence,

evaluation and analysis of the context or en-

vironment (including support from manage-

ment and the culture for change ofthe en-

vironment),and the use offacilitating tech-

niques that are fluid and adaptive to the chang-

ing environment.

For this project, the level of evidence was

rated low (mostof the evidence on hourly

nurse roundingincluded qualityimprove-

ment program evaluations) whereas context

or environment was rated high (demonstrated

by the expressed attitudesand beliefsof

the majority of staff members and leadership

aboutthe value ofimproving the care pro-

vided to patients and the desire to reduce

harm).Since the evidence componentwas

low and the contextcomponentwas high,

the facilitation method suggested by the PAR-

iHS framework was to enable and empower

the staff to take control of their learning and

change process needs through mentoring and

supportof staffdecisions.31 Discussions re-

garding current best practices and the posi-

tive effects of structured hourly nurse round-

ing practices were key elements in supporting

the staff to be active in the decision to move

forward with implementation. Institutional re-

view board–exemptapprovalwas obtained

for this evidence-based practice project.

Planning the intervention

A literature search was conducted using

CINAHL,PubMed,CochraneDatabaseof

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

154 JOURNAL OFNURSINGCAREQUALITY/APRIL–JUNE2015

that nursingcare stronglycontributesto

patients’perceptionsof overallsatisfaction

and likelihood to recommend a facility to

others.26−30 SupplementalDigitalContent,

Table (availableat: http://links.lww.com/

JNCQ/A126),provides a summary of studies

on the effects of structured nurse rounding on

patient satisfaction,patient falls,HAPU,and

call light usage.

LOCAL PROBLEM

The project facilityadopted structured

hourly nurse rounding as a standard of nurs-

ing care in 2008;however,there was little

structure to and accountability for implemen-

tation of this practice. As a result, past efforts

with hourly nurse rounding were inconsistent

and ineffective. Discussions with the nursing

staff and observation of practice revealed min-

imal compliance with hourly nurse rounding

processor the intentto assesspain, elim-

ination,environment,and position (PEEP)

proactively in the current day. Therefore, the

projectleadermet with nursing leadership

to present current evidence and benefits as-

sociated with thisintervention and to gar-

ner support for implementation on one pilot

unit. The project unit was a 24-bed medical-

surgical nursing unit with private and semipri-

vate rooms. This unit was selected on the basis

of its need for improvement in patient satisfac-

tion scores (lowest rating of medical-surgical

units in facility) as well as its higher incidence

of patient falls (2 times the national mean) and

HAPUs (higher than facility mean).

Intended improvement/study question

The purpose of this project was to imple-

ment a standardized structured hourly nurse

rounding processand to monitorthe out-

comes of patient satisfaction, patient falls, and

HAPUs over a 3-month time period.

METHODS

Setting

Promoting Action on Research Implemen-

tation in Health Services(PARiHS)frame-

work was the translation model used for the

project.31 This framework isbased on the

premise that successful implementation of ev-

idence into practice is dependent on 3 fac-

tors:evidence,context or environment,and

facilitation. Each factor has equal importance

in the implementation process and is interre-

lated with other factors.For example,if the

evidence is strong and the environment is ac-

cessible to change, then the facilitation of the

change process willbe less rigorous and de-

manding.In contrast,if the evidence is not

strong and the environment is not adaptive to

change,the facilitation process may require

a higher levelof supportand change man-

agement skills for successful implementation

to occur. The framework requires evaluation

and presentation of the supporting evidence,

evaluation and analysis of the context or en-

vironment (including support from manage-

ment and the culture for change ofthe en-

vironment),and the use offacilitating tech-

niques that are fluid and adaptive to the chang-

ing environment.

For this project, the level of evidence was

rated low (mostof the evidence on hourly

nurse roundingincluded qualityimprove-

ment program evaluations) whereas context

or environment was rated high (demonstrated

by the expressed attitudesand beliefsof

the majority of staff members and leadership

aboutthe value ofimproving the care pro-

vided to patients and the desire to reduce

harm).Since the evidence componentwas

low and the contextcomponentwas high,

the facilitation method suggested by the PAR-

iHS framework was to enable and empower

the staff to take control of their learning and

change process needs through mentoring and

supportof staffdecisions.31 Discussions re-

garding current best practices and the posi-

tive effects of structured hourly nurse round-

ing practices were key elements in supporting

the staff to be active in the decision to move

forward with implementation. Institutional re-

view board–exemptapprovalwas obtained

for this evidence-based practice project.

Planning the intervention

A literature search was conducted using

CINAHL,PubMed,CochraneDatabaseof

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

LWW/JNCQ JNCQ-D-14-00043 January 31, 2015 17:46

Effectiveness of Structured Hourly Nurse Rounding155

Systematic Reviews,and Nursing & Allied

Health Collection. The search was limited to

published literature between 2008 and 2014.

Key search words used were patient satisfac-

tion, patient fallprevention, pressure ulcer

prevention,and calllight.Additionalsearch

words of hospital and rounds were added to

the key word of patient satisfaction, and the

search word hospitalwas added to the key

words patientfall prevention and pressure

ulcer prevention. Peer-reviewed articles were

evaluated.Evaluation oftitles and abstracts

was performed with the following inclusion

criteria: inpatients in an acute care facility, an

intervention consisting ofstructured nurse

rounding, and written in the English language.

Studiesthat included every houror every

2 hours’structured nurse rounding and re-

ported outcomes were analyzed for strength

and quality ofevidence based on the Johns

Hopkins NursingEvidence-BasedPractice

Modeland Guidelines32 (see Supplemental

DigitalContent,Table,available at:http://

links.lww.com/JNCQ/A126).Evidencewas

classified into 1 of 5 (levels 1-5) hierarchical

levels dependent on the study design and then

a rating of quality (a,b, c) was assigned on

the basis of the overall study characteristics.

The process ofimplementation included

development of a structured approach to staff

education,historicaldata analysis,observa-

tions of staff workflow, evaluation of the cur-

rent state of hourly nurse rounding,and de-

velopment of guidelines for structured hourly

nurse rounding on the unit.First,a meeting

with the 8-member unit-based nursing gover-

nance council resulted in unanimous approval

for implementation of structured hourly nurse

rounding. A 20-minute education session that

included a review of evidence,working def-

inition of structured hourly nurse rounding,

review ofhistoricalperformance indicators,

and goals for improvement in the fiscalyear

were provided to every staff member on the

unit through group staff meetings or one-on-

one sessions.A fact sheet was presented to

the staff for their reference.

Observations and shadowing ofthe staff

on all3 shifts,on weekdays and weekends,

were performed for several weeks. These ob-

servations yielded information on workflow

patterns,usage and timelinessof response

to calllights,and length oftime needed to

complete a structured round with and with-

out need for toileting. Baseline data were col-

lected on compliance with performing hourly

nurse rounding, patient satisfaction, fall rates,

and HAPU rates.Key stakeholders included

the nurse manager,registered nurses,pa-

tient care assistants, and unit secretaries, who

were instrumental in developing the timeline

for implementation and were empowered to

make decisions throughout the project,and

the patients.Guidelines and principles out-

lining the accountabilities for performing the

nurse rounding were developed on the basis

of the published evidence, the observed time

needed for conducting nurse rounding,and

the workflow patterns of the staff.

Methods of evaluation

Baseline patient satisfaction scores on Hos-

pital ConsumerAssessmentof Healthcare

Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) surveys and

inpatientfall rates and HAPU rates through

the event report process were collected, an-

alyzed,and presented prior to implementa-

tion of structured nurse rounding. Structured

hourly nurse rounding compliance was also

determined during a 7-day period of time just

prior to implementation. Monthly data collec-

tion and outcome reporting were provided

on the performance indicators. Monitoring of

7-consecutive-day rounding compliance was

assessed each month during the project imple-

mentation period. Continuous monitoring of

compliance of structured hourly rounds was

not performed since manual collection of the

data was perceived by the staff as adding bur-

den to their other duties.Results were dis-

cussed monthly atstaffmeetings and were

graphically displayed in the staff lounge.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to trend, or-

ganize, and describe the characteristics of the

data collected on hourly nurse rounding com-

pliance,inpatient fallrates,and HAPU rates.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Effectiveness of Structured Hourly Nurse Rounding155

Systematic Reviews,and Nursing & Allied

Health Collection. The search was limited to

published literature between 2008 and 2014.

Key search words used were patient satisfac-

tion, patient fallprevention, pressure ulcer

prevention,and calllight.Additionalsearch

words of hospital and rounds were added to

the key word of patient satisfaction, and the

search word hospitalwas added to the key

words patientfall prevention and pressure

ulcer prevention. Peer-reviewed articles were

evaluated.Evaluation oftitles and abstracts

was performed with the following inclusion

criteria: inpatients in an acute care facility, an

intervention consisting ofstructured nurse

rounding, and written in the English language.

Studiesthat included every houror every

2 hours’structured nurse rounding and re-

ported outcomes were analyzed for strength

and quality ofevidence based on the Johns

Hopkins NursingEvidence-BasedPractice

Modeland Guidelines32 (see Supplemental

DigitalContent,Table,available at:http://

links.lww.com/JNCQ/A126).Evidencewas

classified into 1 of 5 (levels 1-5) hierarchical

levels dependent on the study design and then

a rating of quality (a,b, c) was assigned on

the basis of the overall study characteristics.

The process ofimplementation included

development of a structured approach to staff

education,historicaldata analysis,observa-

tions of staff workflow, evaluation of the cur-

rent state of hourly nurse rounding,and de-

velopment of guidelines for structured hourly

nurse rounding on the unit.First,a meeting

with the 8-member unit-based nursing gover-

nance council resulted in unanimous approval

for implementation of structured hourly nurse

rounding. A 20-minute education session that

included a review of evidence,working def-

inition of structured hourly nurse rounding,

review ofhistoricalperformance indicators,

and goals for improvement in the fiscalyear

were provided to every staff member on the

unit through group staff meetings or one-on-

one sessions.A fact sheet was presented to

the staff for their reference.

Observations and shadowing ofthe staff

on all3 shifts,on weekdays and weekends,

were performed for several weeks. These ob-

servations yielded information on workflow

patterns,usage and timelinessof response

to calllights,and length oftime needed to

complete a structured round with and with-

out need for toileting. Baseline data were col-

lected on compliance with performing hourly

nurse rounding, patient satisfaction, fall rates,

and HAPU rates.Key stakeholders included

the nurse manager,registered nurses,pa-

tient care assistants, and unit secretaries, who

were instrumental in developing the timeline

for implementation and were empowered to

make decisions throughout the project,and

the patients.Guidelines and principles out-

lining the accountabilities for performing the

nurse rounding were developed on the basis

of the published evidence, the observed time

needed for conducting nurse rounding,and

the workflow patterns of the staff.

Methods of evaluation

Baseline patient satisfaction scores on Hos-

pital ConsumerAssessmentof Healthcare

Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) surveys and

inpatientfall rates and HAPU rates through

the event report process were collected, an-

alyzed,and presented prior to implementa-

tion of structured nurse rounding. Structured

hourly nurse rounding compliance was also

determined during a 7-day period of time just

prior to implementation. Monthly data collec-

tion and outcome reporting were provided

on the performance indicators. Monitoring of

7-consecutive-day rounding compliance was

assessed each month during the project imple-

mentation period. Continuous monitoring of

compliance of structured hourly rounds was

not performed since manual collection of the

data was perceived by the staff as adding bur-

den to their other duties.Results were dis-

cussed monthly atstaffmeetings and were

graphically displayed in the staff lounge.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to trend, or-

ganize, and describe the characteristics of the

data collected on hourly nurse rounding com-

pliance,inpatient fallrates,and HAPU rates.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

LWW/JNCQ JNCQ-D-14-00043 January 31, 2015 17:46

156 JOURNAL OFNURSINGCAREQUALITY/APRIL–JUNE2015

A Cox-Stuart trend analysis was performed on

the historical inpatient fall data to effectively

illustrate that fall rates declined more consis-

tently postimplementation.Frequency distri-

bution analysis of the HCAHPS responses was

performed. Data were compared with appro-

priate benchmarks for patient satisfaction, in-

patient fall, and HAPU rates.

RESULTS

Outcomes

An overallgoalof more than 80% hourly

nurse rounding compliance was set after the

baseline assessmentand prior to the imple-

mentation ofhourly nurse rounding.Prein-

tervention baseline hourly nurse rounding

compliance was 48.4%.Additionalmonthly

compliancereviews were performedfor

7-consecutive-day periods revealing compli-

ance rates of 69.4%, 44.3%, and 59.2%. Overall

compliance was calculated by the total num-

ber ofrounds completed divided by the to-

tal number of possible events.Hourly nurse

rounding was considered to have been per-

formed when a staff member entered the pa-

tient’s room, evaluated the patient for PEEP,

and documented the activity on designated

flow sheets.

The projectunit discharged 582 eligible

patients during the project period. Eighty-one

HCAHPS surveys were returned.Percentage

of “always” declined slightly in the HCAHPS

composite domain score ofresponsiveness

of staff to 48.6% (n = 81) from patients

discharged postimplementation as compared

with a result of 49.3% (n = 35) preimplemen-

tation. However, the other domain responses

allincreased 6.1% to 30.9% postintervention

when compared with preintervention.The

Table displays the comparisons.

A patientfall was counted anytime a pa-

tient descended to the floor with or without

assistance from the hospitalstaff.A patient

fallrate was calculated by the totalnumber

of falls reported divided by the total number

of patient-days multiplied by 1000.A rate of

7.02 patient falls per 1000 patient-days was

noted in the prior year (November 2011 to

February 2012) and a rate of 3.18 resulted fol-

lowing implementation (November 15, 2012,

to February 14, 2013). This reflected a 57.7%

reduction from the previous year during sim-

ilar time periods.

Patientfall rateshad decreased on the

project unit prior to implementationof

structured hourly nurse rounding.A Cox-

Stuart trend analysis was performed on data

from the preceding12 months prior to

Table.Percentage of“Always,” “Yes,” and “9 or10” Reponses in each HCAHPS Domain

Composite Results Pre- and Postimplementation of Hourly Nurse Rounding

HCAHPS Domain

Pre %

(n = 35)

Post %

(n = 81)

1 y After Project

Implementation

(n = 472)

Overall satisfaction 48.6 72.3 72.2

Communication with nurses 70.5 76.6 78.8

Responsiveness of hospital staff 49.3 48.6 57.6

Communication with doctors 69.2 76.7 75.7

Hospital environment 49.1 61.8 59.8

Pain management 58.3 69.8 70.1

Communication about medicines 50.8 81.7 59.1

Discharge information 72.7 86.3 85.8

Likelihood to recommend 60.0 74.7 76.6

Abbreviation: HCAHPS, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

156 JOURNAL OFNURSINGCAREQUALITY/APRIL–JUNE2015

A Cox-Stuart trend analysis was performed on

the historical inpatient fall data to effectively

illustrate that fall rates declined more consis-

tently postimplementation.Frequency distri-

bution analysis of the HCAHPS responses was

performed. Data were compared with appro-

priate benchmarks for patient satisfaction, in-

patient fall, and HAPU rates.

RESULTS

Outcomes

An overallgoalof more than 80% hourly

nurse rounding compliance was set after the

baseline assessmentand prior to the imple-

mentation ofhourly nurse rounding.Prein-

tervention baseline hourly nurse rounding

compliance was 48.4%.Additionalmonthly

compliancereviews were performedfor

7-consecutive-day periods revealing compli-

ance rates of 69.4%, 44.3%, and 59.2%. Overall

compliance was calculated by the total num-

ber ofrounds completed divided by the to-

tal number of possible events.Hourly nurse

rounding was considered to have been per-

formed when a staff member entered the pa-

tient’s room, evaluated the patient for PEEP,

and documented the activity on designated

flow sheets.

The projectunit discharged 582 eligible

patients during the project period. Eighty-one

HCAHPS surveys were returned.Percentage

of “always” declined slightly in the HCAHPS

composite domain score ofresponsiveness

of staff to 48.6% (n = 81) from patients

discharged postimplementation as compared

with a result of 49.3% (n = 35) preimplemen-

tation. However, the other domain responses

allincreased 6.1% to 30.9% postintervention

when compared with preintervention.The

Table displays the comparisons.

A patientfall was counted anytime a pa-

tient descended to the floor with or without

assistance from the hospitalstaff.A patient

fallrate was calculated by the totalnumber

of falls reported divided by the total number

of patient-days multiplied by 1000.A rate of

7.02 patient falls per 1000 patient-days was

noted in the prior year (November 2011 to

February 2012) and a rate of 3.18 resulted fol-

lowing implementation (November 15, 2012,

to February 14, 2013). This reflected a 57.7%

reduction from the previous year during sim-

ilar time periods.

Patientfall rateshad decreased on the

project unit prior to implementationof

structured hourly nurse rounding.A Cox-

Stuart trend analysis was performed on data

from the preceding12 months prior to

Table.Percentage of“Always,” “Yes,” and “9 or10” Reponses in each HCAHPS Domain

Composite Results Pre- and Postimplementation of Hourly Nurse Rounding

HCAHPS Domain

Pre %

(n = 35)

Post %

(n = 81)

1 y After Project

Implementation

(n = 472)

Overall satisfaction 48.6 72.3 72.2

Communication with nurses 70.5 76.6 78.8

Responsiveness of hospital staff 49.3 48.6 57.6

Communication with doctors 69.2 76.7 75.7

Hospital environment 49.1 61.8 59.8

Pain management 58.3 69.8 70.1

Communication about medicines 50.8 81.7 59.1

Discharge information 72.7 86.3 85.8

Likelihood to recommend 60.0 74.7 76.6

Abbreviation: HCAHPS, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

LWW/JNCQ JNCQ-D-14-00043 January 31, 2015 17:46

Effectiveness of Structured Hourly Nurse Rounding157

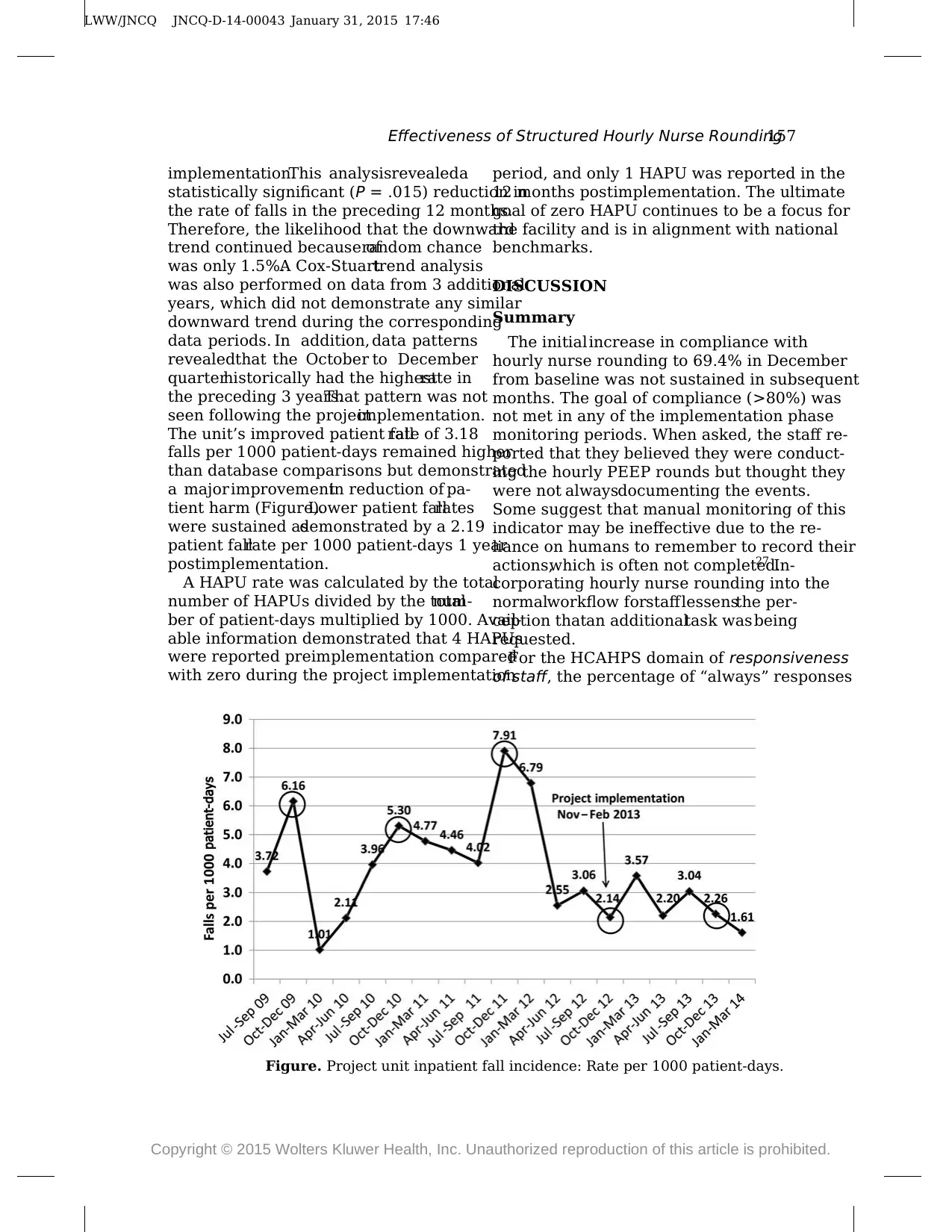

implementation.This analysisrevealeda

statistically significant (P = .015) reduction in

the rate of falls in the preceding 12 months.

Therefore, the likelihood that the downward

trend continued because ofrandom chance

was only 1.5%.A Cox-Stuarttrend analysis

was also performed on data from 3 additional

years, which did not demonstrate any similar

downward trend during the corresponding

data periods. In addition, data patterns

revealedthat the October to December

quarterhistorically had the highestrate in

the preceding 3 years.That pattern was not

seen following the projectimplementation.

The unit’s improved patient fallrate of 3.18

falls per 1000 patient-days remained higher

than database comparisons but demonstrated

a major improvementin reduction of pa-

tient harm (Figure).Lower patient fallrates

were sustained asdemonstrated by a 2.19

patient fallrate per 1000 patient-days 1 year

postimplementation.

A HAPU rate was calculated by the total

number of HAPUs divided by the totalnum-

ber of patient-days multiplied by 1000. Avail-

able information demonstrated that 4 HAPUs

were reported preimplementation compared

with zero during the project implementation

period, and only 1 HAPU was reported in the

12 months postimplementation. The ultimate

goal of zero HAPU continues to be a focus for

the facility and is in alignment with national

benchmarks.

DISCUSSION

Summary

The initialincrease in compliance with

hourly nurse rounding to 69.4% in December

from baseline was not sustained in subsequent

months. The goal of compliance (>80%) was

not met in any of the implementation phase

monitoring periods. When asked, the staff re-

ported that they believed they were conduct-

ing the hourly PEEP rounds but thought they

were not alwaysdocumenting the events.

Some suggest that manual monitoring of this

indicator may be ineffective due to the re-

liance on humans to remember to record their

actions,which is often not completed.27 In-

corporating hourly nurse rounding into the

normalworkflow forstafflessensthe per-

ception thatan additionaltask wasbeing

requested.

For the HCAHPS domain of responsiveness

of staff, the percentage of “always” responses

Figure. Project unit inpatient fall incidence: Rate per 1000 patient-days.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Effectiveness of Structured Hourly Nurse Rounding157

implementation.This analysisrevealeda

statistically significant (P = .015) reduction in

the rate of falls in the preceding 12 months.

Therefore, the likelihood that the downward

trend continued because ofrandom chance

was only 1.5%.A Cox-Stuarttrend analysis

was also performed on data from 3 additional

years, which did not demonstrate any similar

downward trend during the corresponding

data periods. In addition, data patterns

revealedthat the October to December

quarterhistorically had the highestrate in

the preceding 3 years.That pattern was not

seen following the projectimplementation.

The unit’s improved patient fallrate of 3.18

falls per 1000 patient-days remained higher

than database comparisons but demonstrated

a major improvementin reduction of pa-

tient harm (Figure).Lower patient fallrates

were sustained asdemonstrated by a 2.19

patient fallrate per 1000 patient-days 1 year

postimplementation.

A HAPU rate was calculated by the total

number of HAPUs divided by the totalnum-

ber of patient-days multiplied by 1000. Avail-

able information demonstrated that 4 HAPUs

were reported preimplementation compared

with zero during the project implementation

period, and only 1 HAPU was reported in the

12 months postimplementation. The ultimate

goal of zero HAPU continues to be a focus for

the facility and is in alignment with national

benchmarks.

DISCUSSION

Summary

The initialincrease in compliance with

hourly nurse rounding to 69.4% in December

from baseline was not sustained in subsequent

months. The goal of compliance (>80%) was

not met in any of the implementation phase

monitoring periods. When asked, the staff re-

ported that they believed they were conduct-

ing the hourly PEEP rounds but thought they

were not alwaysdocumenting the events.

Some suggest that manual monitoring of this

indicator may be ineffective due to the re-

liance on humans to remember to record their

actions,which is often not completed.27 In-

corporating hourly nurse rounding into the

normalworkflow forstafflessensthe per-

ception thatan additionaltask wasbeing

requested.

For the HCAHPS domain of responsiveness

of staff, the percentage of “always” responses

Figure. Project unit inpatient fall incidence: Rate per 1000 patient-days.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

LWW/JNCQ JNCQ-D-14-00043 January 31, 2015 17:46

158 JOURNAL OFNURSINGCAREQUALITY/APRIL–JUNE2015

was the only domain in which the score

was lower postimplementation than preim-

plementation. The other domain percentages

all increased.All but one HCAHPS domain

demonstrated increases in the percentage of

“always, “yes,” and “9 and 10” responses dur-

ing the project period, which was consistent

with the evidence.

The rate of patient falls on the project unit

decreased prior to implementation ofstruc-

tured hourly nurse rounding possibly due to

a reemphasis on the Fall Prevention Program

in the nursing department. When comparing

falls rates from similartime periods,it ap-

peared there was a decline in fallrates,al-

though the trend began to decline prior to

project implementation. Historically, fall rates

had been highest in the October to December

time period. That usual pattern did not recur

during the project implementation (Figure).

A reduction of 11 fall incidences between the

pre- and postimplementation period reflected

a cost avoidance of $46 563 ($4322 × 11) for

the project implementation period.33

The reduction in the rate ofpatient falls,

when comparinganalogousyearly time

periods,was similarto reportsfrom other

projects and studiesdocumentedin the

literature. While the decline in fall rates dur-

ing implementation wasmodestcompared

with preceding quarters,it was clinically

significantfor the winter quarter especially

considering historic dataand case-mix in-

dices.Both Bourgaultet al13 and Krepper

et al16 noted no effectin patientfalls with

implementation of rounding following preex-

isting robust fall prevention programs and low

rates of patient falls prior to implementation.

HAPU rates per 1000 patient-days had also

declined in the 6 months prior to implemen-

tation on the project unit. However, a reduc-

tion of 4 HAPUs comparing pre-and postim-

plementation resulted in a cost avoidance of

$172 720 ($43 180 × 4).33 This reduction in

HAPU rate was similar to results reported by

Ellis,14 Sherrod et al,18 and the Studer Group.2

Limitations

This project was implementedon 1

medical-surgical unit in 1 hospital. In addition,

3 months is a short period of time to evaluate a

change in nursing workflow or cultural adop-

tion of this intervention for sustainability.

CONCLUSIONS

Change management strategies were used

to influence the culture of nursing practice, so

changes were not be perceived as simply ad-

ditional tasks to complete. Recommendations

for project sustainability include incorporat-

ing unit-based rounding champions to con-

tinue to stimulate enthusiasm and prioritize

discussions so thatthe initialimprovement

changes do not drift. Periodic monitoring and

public display of the data stimulate continual

focus on the results of this intervention.

Evidence indicates thatstructured hourly

nurse rounds are safe,efficient,and useful

in today’s practice.Performing hourly nurse

rounding may be cost-effective as an interven-

tion because it promotes cost avoidance by

reducing injuries related to patient falls and

pressure ulcer formation, both of which may

extend hospitallength ofstays.The corpus

of evidence suggested that structured nurse

rounding demonstrated favorable trendsin

improving patientsatisfaction and reducing

patient falls, HAPUs, and call light usage. This

project demonstrated overall improvement in

patient satisfaction indicators and decreased

patient harm through lower patient fall

and HAPU rates. Reduced patient harm

contributedmore than $200 000in cost

avoidance ofcare that is not reimbursed to

organizations.

REFERENCES

1. MeadeCM, BursellAL, Ketelsen L. Effects of

nursingrounds on patients’ call light use, sat-

isfaction,and safety. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(9):

58-70.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

158 JOURNAL OFNURSINGCAREQUALITY/APRIL–JUNE2015

was the only domain in which the score

was lower postimplementation than preim-

plementation. The other domain percentages

all increased.All but one HCAHPS domain

demonstrated increases in the percentage of

“always, “yes,” and “9 and 10” responses dur-

ing the project period, which was consistent

with the evidence.

The rate of patient falls on the project unit

decreased prior to implementation ofstruc-

tured hourly nurse rounding possibly due to

a reemphasis on the Fall Prevention Program

in the nursing department. When comparing

falls rates from similartime periods,it ap-

peared there was a decline in fallrates,al-

though the trend began to decline prior to

project implementation. Historically, fall rates

had been highest in the October to December

time period. That usual pattern did not recur

during the project implementation (Figure).

A reduction of 11 fall incidences between the

pre- and postimplementation period reflected

a cost avoidance of $46 563 ($4322 × 11) for

the project implementation period.33

The reduction in the rate ofpatient falls,

when comparinganalogousyearly time

periods,was similarto reportsfrom other

projects and studiesdocumentedin the

literature. While the decline in fall rates dur-

ing implementation wasmodestcompared

with preceding quarters,it was clinically

significantfor the winter quarter especially

considering historic dataand case-mix in-

dices.Both Bourgaultet al13 and Krepper

et al16 noted no effectin patientfalls with

implementation of rounding following preex-

isting robust fall prevention programs and low

rates of patient falls prior to implementation.

HAPU rates per 1000 patient-days had also

declined in the 6 months prior to implemen-

tation on the project unit. However, a reduc-

tion of 4 HAPUs comparing pre-and postim-

plementation resulted in a cost avoidance of

$172 720 ($43 180 × 4).33 This reduction in

HAPU rate was similar to results reported by

Ellis,14 Sherrod et al,18 and the Studer Group.2

Limitations

This project was implementedon 1

medical-surgical unit in 1 hospital. In addition,

3 months is a short period of time to evaluate a

change in nursing workflow or cultural adop-

tion of this intervention for sustainability.

CONCLUSIONS

Change management strategies were used

to influence the culture of nursing practice, so

changes were not be perceived as simply ad-

ditional tasks to complete. Recommendations

for project sustainability include incorporat-

ing unit-based rounding champions to con-

tinue to stimulate enthusiasm and prioritize

discussions so thatthe initialimprovement

changes do not drift. Periodic monitoring and

public display of the data stimulate continual

focus on the results of this intervention.

Evidence indicates thatstructured hourly

nurse rounds are safe,efficient,and useful

in today’s practice.Performing hourly nurse

rounding may be cost-effective as an interven-

tion because it promotes cost avoidance by

reducing injuries related to patient falls and

pressure ulcer formation, both of which may

extend hospitallength ofstays.The corpus

of evidence suggested that structured nurse

rounding demonstrated favorable trendsin

improving patientsatisfaction and reducing

patient falls, HAPUs, and call light usage. This

project demonstrated overall improvement in

patient satisfaction indicators and decreased

patient harm through lower patient fall

and HAPU rates. Reduced patient harm

contributedmore than $200 000in cost

avoidance ofcare that is not reimbursed to

organizations.

REFERENCES

1. MeadeCM, BursellAL, Ketelsen L. Effects of

nursingrounds on patients’ call light use, sat-

isfaction,and safety. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(9):

58-70.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

LWW/JNCQ JNCQ-D-14-00043 January 31, 2015 17:46

Effectiveness of Structured Hourly Nurse Rounding159

2. StuderGroup.Hourly rounding supplement.Best

Practice ed. http://www.studergroup.com/flash

hourlyrounding.Published 2007.Accessed Novem-

ber 15, 2012.

3. Culley T.Reduce calllightfrequency with hourly

rounds. Nurs Manag. 2008;39(3):50-52.

4. Murphy TH,Labonte P,Houser L.Falls prevention

for elders in acute care.An evidence-based nursing

practice initiative. Crit Care Nurs Q.2008;31(1):33-

39.

5. SobaskiT, Abraham M,FillmoreR, McFallDE,

Davidhizar R. The effect of routine rounding by nurs-

ing staff on patient satisfaction on a cardiac telemetry

unit. Health Care Manag. 2008;27(4):332-337.

6. Tea C, Ellison M, Feghali F. Proactive patient rounding

to increase customer service and satisfaction on an

orthopaedic unit. Orthop Nurs. 2008;27(4):233-240.

7. Weisgram B, Raymond S. Using evidence-based nurs-

ing rounds to improve patientoutcomes.Medsurg

Nurs. 2008;17(6):429-430.

8. Stefancyk AL.Safe and reliable care.Am J Nurs.

2009;109(7):70-71.

9. Ford BM. Hourly rounding:a strategyto im-

prove patientsatisfaction scores.Medsurg Nurs.

2010;19(3):188-191.

10. Berg K,Sailors C,Reimer R,O’Brien Y,Ward-Smith

P. Hourly rounding with a purpose. Iowa Nurs Rep.

2011;3:12-14.

11. Blakley D, Kroth M, Gregson J. The impact of nurse

rounding on patient satisfaction in a medical-surgical

hospital unit. Medsurg Nurs. 2011;20(6):327-332.

12. Bonuel N, Manjos A, Lockett L, Gray-Becknell T. Best

practice fall prevention strategies. Crit Care Nurs Q.

2011;34(2):154-158.

13. BourgaultAM, King MM,Hart P, CampbellMK,

Swartz S,Lou M.Does regular rounding by nursing

associates boostpatientsatisfaction?Nurs Manag.

2008;39(11):18-24.

14. Ellis E. Hourly nurse rounds help to reduce falls, pres-

sure ulcers, and call light use, and contribute to rise

in patient satisfaction. http://www.innovations.ahrq

.gov/content.aspx?id=3204.Published 2012. Ac-

cessed November 24, 2012.

15. Kessler B,Claude-Gutekunst M,Donchez AM,Dries

RF, Snyder MM. The merry-go-round of patient round-

ing: assure your patients get the brass ring. Medsurg

Nurs. 2012;21(4):240-245.

16. Krepper R,Vallejo B,Smith C,et al. Evaluation of

a standardized hourly rounding process (SHaRP).J

Healthc Q. 2014;36(2):62-69.

17. Olrich T, Kalman M, Nigolian C. Hourly rounding: a

replication study. Medsurg Nurs. 2012;21(1):23-26.

18. Sherrod BC, Brown R, Vroom J, Sullivan DT. Round

with purpose. Nurs Manag. 2012;43(1):33-38.

19. Tucker SJ,Bieber PL,Attlesey-Pries JM,Olson ME,

Dierkhising RA.Outcomes and challenges in imple-

menting hourly rounds to reduce falls in orthope-

dic units.Worldviews Evid Based Nurs.2012;9(1):

18-29.

20. Hutchings M, Ward P, Bloodworth K. “Caring around

the clock”: a new approach to intentional rounding.

Nurs Manag. 2013;20(5):24-30.

21. Dix G, Phillips J, Braide M. Engaging staff with inten-

tional rounding. Nurs Times. 2012;108(3):14-16.

22. Braide M.The effect of intentionalrounding on es-

sential care. Nurs Times. 2013;109(20):16-18.

23. Gardner G, Woollett K, Daly N, Richardson B. Measur-

ing the effect of patient comfort rounds on practice

environment and patient satisfaction:a pilot study.

Int J Nurs Pract. 2009;15(4):287-293.

24. Woodard JL.Effects of rounding on patient satisfac-

tion and patient safety on a medical-surgical unit. Clin

Nurs Spec. 2009;23:201-206.

25. Petras DM,Dudjak LA,Bender CM.Piloting patient

rounding as a quality improvementinitiative.Nurs

Manag. 2013;44(7):19-23.

26. Shattell M, Hogen B, Thomas S. “It’s the people that

make the environment good or bad.” The patient’s

experience of the acute care hospitalenvironment.

AACN Clin Issues. 2005;16(2):159-169.

27. Wagner D, Bear M. Patient satisfaction with nursing

care: a concept analysis within a nursing framework.

J Adv Nurs. 2008;65(3):692-701.

28. OtaniK, Herrmann PA,Kurz RS.Improving patient

evaluation of hospital care and increasing their inten-

tion to recommend:are they the same or different

constructs? Health Serv Manag Res.2010;23(2):60-

65.

29. Kennedy B,Craig JB,WetselM, Reimels E,Wright

J. Three nursing interventions’impacton HCAHPS

scores. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013;28(4):327-334.

30. Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The

patientexperience and health outcomes.N Engl J

Med. 2013;368(3):201-203.

31. Kitson AL,Rycroft-Malone J,Harvey G,McCormack

B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful imple-

mentation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS

framework: theoretical and practical challenges [de-

bate].ImplementSci. 2008;3:1.doi:10.1186/1748-

5908-3-1.

32. DearholtSL, Dang D. Johns Hopkins Nursing

Evidence-Based Practice: Model and Guidelines. 2nd

ed. Indianapolis,IN:Sigma Theta Tau International;

2012.

33. Schifalacqua MM,Mamula J,Mason AR.Return on

investmentimperative.The costof care calculator

for an evidence-based practice program.Nurs Adm

Q. 2011;35(1):15-20.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Effectiveness of Structured Hourly Nurse Rounding159

2. StuderGroup.Hourly rounding supplement.Best

Practice ed. http://www.studergroup.com/flash

hourlyrounding.Published 2007.Accessed Novem-

ber 15, 2012.

3. Culley T.Reduce calllightfrequency with hourly

rounds. Nurs Manag. 2008;39(3):50-52.

4. Murphy TH,Labonte P,Houser L.Falls prevention

for elders in acute care.An evidence-based nursing

practice initiative. Crit Care Nurs Q.2008;31(1):33-

39.

5. SobaskiT, Abraham M,FillmoreR, McFallDE,

Davidhizar R. The effect of routine rounding by nurs-

ing staff on patient satisfaction on a cardiac telemetry

unit. Health Care Manag. 2008;27(4):332-337.

6. Tea C, Ellison M, Feghali F. Proactive patient rounding

to increase customer service and satisfaction on an

orthopaedic unit. Orthop Nurs. 2008;27(4):233-240.

7. Weisgram B, Raymond S. Using evidence-based nurs-

ing rounds to improve patientoutcomes.Medsurg

Nurs. 2008;17(6):429-430.

8. Stefancyk AL.Safe and reliable care.Am J Nurs.

2009;109(7):70-71.

9. Ford BM. Hourly rounding:a strategyto im-

prove patientsatisfaction scores.Medsurg Nurs.

2010;19(3):188-191.

10. Berg K,Sailors C,Reimer R,O’Brien Y,Ward-Smith

P. Hourly rounding with a purpose. Iowa Nurs Rep.

2011;3:12-14.

11. Blakley D, Kroth M, Gregson J. The impact of nurse

rounding on patient satisfaction in a medical-surgical

hospital unit. Medsurg Nurs. 2011;20(6):327-332.

12. Bonuel N, Manjos A, Lockett L, Gray-Becknell T. Best

practice fall prevention strategies. Crit Care Nurs Q.

2011;34(2):154-158.

13. BourgaultAM, King MM,Hart P, CampbellMK,

Swartz S,Lou M.Does regular rounding by nursing

associates boostpatientsatisfaction?Nurs Manag.

2008;39(11):18-24.

14. Ellis E. Hourly nurse rounds help to reduce falls, pres-

sure ulcers, and call light use, and contribute to rise

in patient satisfaction. http://www.innovations.ahrq

.gov/content.aspx?id=3204.Published 2012. Ac-

cessed November 24, 2012.

15. Kessler B,Claude-Gutekunst M,Donchez AM,Dries

RF, Snyder MM. The merry-go-round of patient round-

ing: assure your patients get the brass ring. Medsurg

Nurs. 2012;21(4):240-245.

16. Krepper R,Vallejo B,Smith C,et al. Evaluation of

a standardized hourly rounding process (SHaRP).J

Healthc Q. 2014;36(2):62-69.

17. Olrich T, Kalman M, Nigolian C. Hourly rounding: a

replication study. Medsurg Nurs. 2012;21(1):23-26.

18. Sherrod BC, Brown R, Vroom J, Sullivan DT. Round

with purpose. Nurs Manag. 2012;43(1):33-38.

19. Tucker SJ,Bieber PL,Attlesey-Pries JM,Olson ME,

Dierkhising RA.Outcomes and challenges in imple-

menting hourly rounds to reduce falls in orthope-

dic units.Worldviews Evid Based Nurs.2012;9(1):

18-29.

20. Hutchings M, Ward P, Bloodworth K. “Caring around

the clock”: a new approach to intentional rounding.

Nurs Manag. 2013;20(5):24-30.

21. Dix G, Phillips J, Braide M. Engaging staff with inten-

tional rounding. Nurs Times. 2012;108(3):14-16.

22. Braide M.The effect of intentionalrounding on es-

sential care. Nurs Times. 2013;109(20):16-18.

23. Gardner G, Woollett K, Daly N, Richardson B. Measur-

ing the effect of patient comfort rounds on practice

environment and patient satisfaction:a pilot study.

Int J Nurs Pract. 2009;15(4):287-293.

24. Woodard JL.Effects of rounding on patient satisfac-

tion and patient safety on a medical-surgical unit. Clin

Nurs Spec. 2009;23:201-206.

25. Petras DM,Dudjak LA,Bender CM.Piloting patient

rounding as a quality improvementinitiative.Nurs

Manag. 2013;44(7):19-23.

26. Shattell M, Hogen B, Thomas S. “It’s the people that

make the environment good or bad.” The patient’s

experience of the acute care hospitalenvironment.

AACN Clin Issues. 2005;16(2):159-169.

27. Wagner D, Bear M. Patient satisfaction with nursing

care: a concept analysis within a nursing framework.

J Adv Nurs. 2008;65(3):692-701.

28. OtaniK, Herrmann PA,Kurz RS.Improving patient

evaluation of hospital care and increasing their inten-

tion to recommend:are they the same or different

constructs? Health Serv Manag Res.2010;23(2):60-

65.

29. Kennedy B,Craig JB,WetselM, Reimels E,Wright

J. Three nursing interventions’impacton HCAHPS

scores. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013;28(4):327-334.

30. Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The

patientexperience and health outcomes.N Engl J

Med. 2013;368(3):201-203.

31. Kitson AL,Rycroft-Malone J,Harvey G,McCormack

B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful imple-

mentation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS

framework: theoretical and practical challenges [de-

bate].ImplementSci. 2008;3:1.doi:10.1186/1748-

5908-3-1.

32. DearholtSL, Dang D. Johns Hopkins Nursing

Evidence-Based Practice: Model and Guidelines. 2nd

ed. Indianapolis,IN:Sigma Theta Tau International;

2012.

33. Schifalacqua MM,Mamula J,Mason AR.Return on

investmentimperative.The costof care calculator

for an evidence-based practice program.Nurs Adm

Q. 2011;35(1):15-20.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

1 out of 7

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.