Systematic Overview: Efficacy of Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/11

|10

|11051

|428

Literature Review

AI Summary

This review systematically examines the efficacy of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for major psychiatric disorders in adults. It analyzes 61 meta-analyses encompassing 852 individual trials and 137,126 participants, comparing the effectiveness of these treatments against placebo, head-to-head, and in combination. The review also assesses the methodological quality of the included trials. Findings indicate that both pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies are effective, with psychotherapies showing higher effect sizes compared to placebo, though direct comparisons lack consistent differences. Pharmacotherapy trials generally exhibit larger sample sizes and better blinding, while psychotherapy trials report lower dropout rates and follow-up data. The review highlights the need for well-designed direct comparisons and research into combining both treatment modalities for optimal patient outcomes. It also addresses the methodological differences between pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy trials, emphasizing the limitations of indirect comparisons.

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Efficacy of Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

for Adult Psychiatric Disorders

A Systematic Overview of Meta-analyses

Maximilian Huhn, MD; Magdolna Tardy, MSc; Loukia Maria Spineli, MSc; Werner Kissling, MD; Hans Förstl, MD;

Gabriele Pitschel-Walz, PhD; Claudia Leucht, MD; Myrto Samara, MD; Markus Dold, MD; John M. Davis, MD;

Stefan Leucht, MD

IMPORTANCEThere is debate about the effectiveness of psychiatric treatments and whether

pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy should be primarily used.

OBJECTIVESTo perform a systematic overview on the efficacy of pharmacotherapies and

psychotherapies for major psychiatric disorders and to compare the quality of

pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy trials.

EVIDENCE REVIEWWe searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library

(April 2012, with no time or language limit) for systematic reviews on pharmacotherapy or

psychotherapy vs placebo, pharmacotherapy vs psychotherapy, and their combination vs

either modality alone. Two reviewers independently selected the meta-analyses and

extracted efficacy effect sizes. We assessed the quality of the individual trials included in the

pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy meta-analyses with the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

FINDINGSThe search yielded 45 233 results. We included 61 meta-analyses on 21 psychiatric

disorders, which contained 852 individual trials and 137 126 participants. The mean effect size

of the meta-analyses was medium (mean, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.41-0.59). Effect sizes of

psychotherapies vs placebo tended to be higher than those of medication, but direct

comparisons, albeit usually based on few trials, did not reveal consistent differences.

Individual pharmacotherapy trials were more likely to have large sample sizes, blinding,

control groups, and intention-to-treat analyses. In contrast, psychotherapy trials had lower

dropout rates and provided follow-up data. In psychotherapy studies, wait-list designs

showed larger effects than did comparisons with placebo.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCEMany pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies are effective,

but there is a lot of room for improvement. Because of the multiple differences in the

methods used in pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy trials, indirect comparisons of their

effect sizes compared with placebo or no treatment are problematic. Well-designed direct

comparisons, which are scarce, need public funding. Because patients often benefit from

both forms of therapy, research should also focus on how both modalities can be best

combined to maximize synergy rather than debate the use of one treatment over the other.

JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(6):706-715. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.112

Published online April 30, 2014.

Editorial page 624

Supplemental content at

jamapsychiatry.com

Author Affiliations: Department of

Psychiatry and Psychotherapy,

Technische Universität München,

München, Germany (Huhn, Tardy,

Kissling, Förstl, Pitschel-Walz, Claudia

Leucht, Samara, Dold, S. Leucht);

Department of Psychiatry, University

of Oxford, Warneford Hospital,

Oxford, England (C. Leucht, Stefan

Leucht); Department of Hygiene and

Epidemiology, School of Medicine,

University of Ioannina, University

Campus, Ioannina, Greece (Spineli);

Psychiatric Institute, University of

Illinois at Chicago (Davis); Institute of

Psychiatry, King’s College London,

London, England (S. Leucht).

Corresponding Author: Stefan

Leucht, MD, Department of

Psychiatry and Psychotherapy,

Technische Universität München,

Klinikum rechts der Isar,

Ismaningerstrasse 22, 81675

München, Germany (stefan.leucht

@lrz.tum.de).

Clinical Review & Education

Review

706 jamapsychiatry.com

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

Efficacy of Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

for Adult Psychiatric Disorders

A Systematic Overview of Meta-analyses

Maximilian Huhn, MD; Magdolna Tardy, MSc; Loukia Maria Spineli, MSc; Werner Kissling, MD; Hans Förstl, MD;

Gabriele Pitschel-Walz, PhD; Claudia Leucht, MD; Myrto Samara, MD; Markus Dold, MD; John M. Davis, MD;

Stefan Leucht, MD

IMPORTANCEThere is debate about the effectiveness of psychiatric treatments and whether

pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy should be primarily used.

OBJECTIVESTo perform a systematic overview on the efficacy of pharmacotherapies and

psychotherapies for major psychiatric disorders and to compare the quality of

pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy trials.

EVIDENCE REVIEWWe searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library

(April 2012, with no time or language limit) for systematic reviews on pharmacotherapy or

psychotherapy vs placebo, pharmacotherapy vs psychotherapy, and their combination vs

either modality alone. Two reviewers independently selected the meta-analyses and

extracted efficacy effect sizes. We assessed the quality of the individual trials included in the

pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy meta-analyses with the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

FINDINGSThe search yielded 45 233 results. We included 61 meta-analyses on 21 psychiatric

disorders, which contained 852 individual trials and 137 126 participants. The mean effect size

of the meta-analyses was medium (mean, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.41-0.59). Effect sizes of

psychotherapies vs placebo tended to be higher than those of medication, but direct

comparisons, albeit usually based on few trials, did not reveal consistent differences.

Individual pharmacotherapy trials were more likely to have large sample sizes, blinding,

control groups, and intention-to-treat analyses. In contrast, psychotherapy trials had lower

dropout rates and provided follow-up data. In psychotherapy studies, wait-list designs

showed larger effects than did comparisons with placebo.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCEMany pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies are effective,

but there is a lot of room for improvement. Because of the multiple differences in the

methods used in pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy trials, indirect comparisons of their

effect sizes compared with placebo or no treatment are problematic. Well-designed direct

comparisons, which are scarce, need public funding. Because patients often benefit from

both forms of therapy, research should also focus on how both modalities can be best

combined to maximize synergy rather than debate the use of one treatment over the other.

JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(6):706-715. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.112

Published online April 30, 2014.

Editorial page 624

Supplemental content at

jamapsychiatry.com

Author Affiliations: Department of

Psychiatry and Psychotherapy,

Technische Universität München,

München, Germany (Huhn, Tardy,

Kissling, Förstl, Pitschel-Walz, Claudia

Leucht, Samara, Dold, S. Leucht);

Department of Psychiatry, University

of Oxford, Warneford Hospital,

Oxford, England (C. Leucht, Stefan

Leucht); Department of Hygiene and

Epidemiology, School of Medicine,

University of Ioannina, University

Campus, Ioannina, Greece (Spineli);

Psychiatric Institute, University of

Illinois at Chicago (Davis); Institute of

Psychiatry, King’s College London,

London, England (S. Leucht).

Corresponding Author: Stefan

Leucht, MD, Department of

Psychiatry and Psychotherapy,

Technische Universität München,

Klinikum rechts der Isar,

Ismaningerstrasse 22, 81675

München, Germany (stefan.leucht

@lrz.tum.de).

Clinical Review & Education

Review

706 jamapsychiatry.com

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

M uch controversy surrounds psychiatry, including a de-

bate about the effectiveness of its treatments. For ex-

ample, the efficacy of antipsychotics,

1

cholinesterase

inhibitors,2and lithium prophylaxis3has been questioned, and Kirsch

et al4 concluded that antidepressants should be used only in se-

verely ill patients. Leucht et al5 showed that psychiatric drugs have

the same range of efficacy as frequently used drugs from other medi-

cal specialties. Nevertheless, the criticism has expanded to psycho-

therapy, in particular psychoanalysis,6 but also to cognitive behav-

ioral therapy (CBT).7 Moreover,whether psychotherapy or

medication should be used to treat psychiatric conditions is strongly

disputed. This ongoing criticism of psychiatry and the debate about

the appropriate treatment make it necessary to examine the situa-

tion and present a broad appraisal. Such an attempt has been made

possible by meta-analyses, which provide standardized quantita-

tive measures of their efficacy by the calculation of effect sizes.8 We

therefore conducted a systematic overview of meta-analyses on the

efficacy of drug therapy and psychotherapy for major psychiatric dis-

orders, which we classified in 3 comparisons: psychotherapy or phar-

macotherapy compared with placebo or no treatment, head-to-

head comparisons of pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies, and

the combination of both treatments. Moreover, we compared the

methodologic quality of the individual drug and psychotherapy trials

included in these meta-analyses. We had 3 objectives. First, we aimed

to present an overview of what benefits psychiatry as a field can pro-

vide for patients, examining the contributions of pharmaco-

therapy and psychotherapy. Second, we wanted to determine the

understudied areas, which can be roughly derived from the num-

bers of studies and participants included in the meta-analyses. Fi-

nally, we examined whether pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy

trials have general methodologic differences that would be impor-

tant for the interpretation of their meta-analyses. We emphasize that,

because of obvious limitations, our overview is not a guideline of

which treatments should be used and which should not be used for

a disorder. Nevertheless, the systematic approach should lead to re-

sults with important implications for psychiatry.

Methods

Identification of Diseases and Search Strategy

We drafted a protocol and made it freely available on our institu-

tional website (http://tinyurl.com/d6b277p; Supplement [eAppen-

dix 1]).9 Two authors (M.H. and S.L.) selected major psychiatric dis-

orders by reviewing the DSM-IV and InternationalStatistical

Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (Supplement [eAp-

pendix 1]). We did not examine child psychiatric disorders (ICD-10

categories F80-F98 and DSM-IV categories 307-319).

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and PsycINFO (last search on

April 22, 2012; no time or language limit) and individual records of

the Cochrane Library for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of

randomized clinical trials (RCTs) on the following comparisons: (1)

pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy vs placebo, (2) head-to-head

pharmacotherapy vs psychotherapy, and (3) combinations of phar-

macotherapy and psychotherapy vs monotherapy with each inter-

vention. Search terms were meta-analy* or metaanaly* or system-

atic review* combined with the thesaurus of the individual databases

concerning each disorder (Supplement [eAppendix 2]). Titles, ab-

stracts, and, subsequently, full articles were examined by one au-

thor (M.H.), and another (M.T.) independently examined a random

sample of 20% of the retrieved publications. Disagreements were

resolved by discussion with a third author (S.L.). Only between-

group effect sizes were extracted; within-treatment effect sizes were

not used because they generally inflate effects. We included only

standard treatments (eg, antipsychotics for schizophrenia [not

lithium]) and aimed to include one meta-analysis for each disorder.

We applied the following a priori–defined criteria to operationalize

the selection: (1) all patients rather than special populations (eg, only

first-episode patients); (2) classes of drugs rather than single drugs

(eg, any antipsychotic rather than only haloperidol); (3) CBT and psy-

chodynamic approaches (the former are usually recommended by

guidelines; we checked the National Institute for Health and Clini-

cal Excellence10and noted that psychodynamic therapy is consid-

ered a counterpart to CBT) unless other treatments are the stan-

dard (eg, cognitive training for dementia); when reviews on these

specific psychotherapies were not available, we used meta-

analyses on all psychotherapies; (4) the most up-to-date findings;

and (5) full reporting of the results. In case of doubt, Cochrane re-

views were preferred.

Parameters Extracted From the Meta-analyses

Two authors (M.H. and M.T.) independently extracted results on the

primary efficacy outcomes, which generally were the mean (change)

scores of overall symptoms at the end point (eg, Hamilton Scale for D

pression) and study-defined responder rates (for acute treatment) or

relapse rates (for maintenance treatment). We also recorded the num

ber of studies and participants included in the meta-analyses and the

mean study duration and number of psychotherapy sessions.

Dichotomous Outcomes

We extracted the percentage of responders (or relapsers) in drug and

placebo groups, the response ratio or relative risk reduction (both ab-

breviated as RR), the absolute response or risk difference (ARD), and

the number needed to treat (NNT), all with their 95% CIs. The Supple

ment (eAppendix 3) presents a detailed explanation.

Continuous Outcomes

For mean values of rating scales, we recorded between-group mean

differences (MDs) (ie, the difference between the raw scores) and

standardized MDs (SMDs) (effect size, Hedges g8 value if avail-

able), which express MD in standard deviation (SD) units. We fol-

lowed the original authors’ decisions concerning fixed- vs random-

effects models (the general use of a random-effects model did not

change the overall results [Supplement; eAppendix 4 and eTable 4]).

Missing Parameters

If necessary, we transformed the data to our 5 parameters (MD/SMD/

ARD/RR/NNT) or recalculated meta-analyses by entering single-trial

results into meta-analytic software programs.11,12

When only effect sizes

for dichotomous outcomes (ARD, RR) were available, SMDs were es-

timated with Comprehensive Meta-analysis, version 2.12The pur-

pose was to present all results in a single unit (SMD) in the figures.

Extraction of Quality Indicators From Individual Studies

One author (M.H., C.L., M.S., or M.D.) retrieved all studies included

in the meta-analyses (only the acute phase to enhance comparabil-

Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Adults Review Clinical Review & Education

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA PsychiatryJune 2014Volume 71, Number 6707

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

M uch controversy surrounds psychiatry, including a de-

bate about the effectiveness of its treatments. For ex-

ample, the efficacy of antipsychotics,

1

cholinesterase

inhibitors,2and lithium prophylaxis3has been questioned, and Kirsch

et al4 concluded that antidepressants should be used only in se-

verely ill patients. Leucht et al5 showed that psychiatric drugs have

the same range of efficacy as frequently used drugs from other medi-

cal specialties. Nevertheless, the criticism has expanded to psycho-

therapy, in particular psychoanalysis,6 but also to cognitive behav-

ioral therapy (CBT).7 Moreover,whether psychotherapy or

medication should be used to treat psychiatric conditions is strongly

disputed. This ongoing criticism of psychiatry and the debate about

the appropriate treatment make it necessary to examine the situa-

tion and present a broad appraisal. Such an attempt has been made

possible by meta-analyses, which provide standardized quantita-

tive measures of their efficacy by the calculation of effect sizes.8 We

therefore conducted a systematic overview of meta-analyses on the

efficacy of drug therapy and psychotherapy for major psychiatric dis-

orders, which we classified in 3 comparisons: psychotherapy or phar-

macotherapy compared with placebo or no treatment, head-to-

head comparisons of pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies, and

the combination of both treatments. Moreover, we compared the

methodologic quality of the individual drug and psychotherapy trials

included in these meta-analyses. We had 3 objectives. First, we aimed

to present an overview of what benefits psychiatry as a field can pro-

vide for patients, examining the contributions of pharmaco-

therapy and psychotherapy. Second, we wanted to determine the

understudied areas, which can be roughly derived from the num-

bers of studies and participants included in the meta-analyses. Fi-

nally, we examined whether pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy

trials have general methodologic differences that would be impor-

tant for the interpretation of their meta-analyses. We emphasize that,

because of obvious limitations, our overview is not a guideline of

which treatments should be used and which should not be used for

a disorder. Nevertheless, the systematic approach should lead to re-

sults with important implications for psychiatry.

Methods

Identification of Diseases and Search Strategy

We drafted a protocol and made it freely available on our institu-

tional website (http://tinyurl.com/d6b277p; Supplement [eAppen-

dix 1]).9 Two authors (M.H. and S.L.) selected major psychiatric dis-

orders by reviewing the DSM-IV and InternationalStatistical

Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (Supplement [eAp-

pendix 1]). We did not examine child psychiatric disorders (ICD-10

categories F80-F98 and DSM-IV categories 307-319).

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and PsycINFO (last search on

April 22, 2012; no time or language limit) and individual records of

the Cochrane Library for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of

randomized clinical trials (RCTs) on the following comparisons: (1)

pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy vs placebo, (2) head-to-head

pharmacotherapy vs psychotherapy, and (3) combinations of phar-

macotherapy and psychotherapy vs monotherapy with each inter-

vention. Search terms were meta-analy* or metaanaly* or system-

atic review* combined with the thesaurus of the individual databases

concerning each disorder (Supplement [eAppendix 2]). Titles, ab-

stracts, and, subsequently, full articles were examined by one au-

thor (M.H.), and another (M.T.) independently examined a random

sample of 20% of the retrieved publications. Disagreements were

resolved by discussion with a third author (S.L.). Only between-

group effect sizes were extracted; within-treatment effect sizes were

not used because they generally inflate effects. We included only

standard treatments (eg, antipsychotics for schizophrenia [not

lithium]) and aimed to include one meta-analysis for each disorder.

We applied the following a priori–defined criteria to operationalize

the selection: (1) all patients rather than special populations (eg, only

first-episode patients); (2) classes of drugs rather than single drugs

(eg, any antipsychotic rather than only haloperidol); (3) CBT and psy-

chodynamic approaches (the former are usually recommended by

guidelines; we checked the National Institute for Health and Clini-

cal Excellence10and noted that psychodynamic therapy is consid-

ered a counterpart to CBT) unless other treatments are the stan-

dard (eg, cognitive training for dementia); when reviews on these

specific psychotherapies were not available, we used meta-

analyses on all psychotherapies; (4) the most up-to-date findings;

and (5) full reporting of the results. In case of doubt, Cochrane re-

views were preferred.

Parameters Extracted From the Meta-analyses

Two authors (M.H. and M.T.) independently extracted results on the

primary efficacy outcomes, which generally were the mean (change)

scores of overall symptoms at the end point (eg, Hamilton Scale for D

pression) and study-defined responder rates (for acute treatment) or

relapse rates (for maintenance treatment). We also recorded the num

ber of studies and participants included in the meta-analyses and the

mean study duration and number of psychotherapy sessions.

Dichotomous Outcomes

We extracted the percentage of responders (or relapsers) in drug and

placebo groups, the response ratio or relative risk reduction (both ab-

breviated as RR), the absolute response or risk difference (ARD), and

the number needed to treat (NNT), all with their 95% CIs. The Supple

ment (eAppendix 3) presents a detailed explanation.

Continuous Outcomes

For mean values of rating scales, we recorded between-group mean

differences (MDs) (ie, the difference between the raw scores) and

standardized MDs (SMDs) (effect size, Hedges g8 value if avail-

able), which express MD in standard deviation (SD) units. We fol-

lowed the original authors’ decisions concerning fixed- vs random-

effects models (the general use of a random-effects model did not

change the overall results [Supplement; eAppendix 4 and eTable 4]).

Missing Parameters

If necessary, we transformed the data to our 5 parameters (MD/SMD/

ARD/RR/NNT) or recalculated meta-analyses by entering single-trial

results into meta-analytic software programs.11,12

When only effect sizes

for dichotomous outcomes (ARD, RR) were available, SMDs were es-

timated with Comprehensive Meta-analysis, version 2.12The pur-

pose was to present all results in a single unit (SMD) in the figures.

Extraction of Quality Indicators From Individual Studies

One author (M.H., C.L., M.S., or M.D.) retrieved all studies included

in the meta-analyses (only the acute phase to enhance comparabil-

Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Adults Review Clinical Review & Education

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA PsychiatryJune 2014Volume 71, Number 6707

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

ity) and assessed their quality with the Cochrane risk of bias tool,13

which is based on scientific evidence of associations between over-

estimates of effect and methodologic shortcomings in the follow-

ing domains:

1. appropriate randomization (eg, computer-generated random-

ization sequence),

2. allocation concealment (eg, voice mail system),

3. blinding (because blinding of therapists is impossible in psycho-

therapy trials, we compared blind outcome assessment with no

blinding), and

4. missing outcomes (whether patients who withdrew from the

study and their reasons for withdrawal were reported, an inten-

tion-to-treat analysis was performed, and we also reported the

size of the overall dropout rate).

We did not examine the tool’s domain selective reporting but

added an item to the control groups that we classified as any con-

temporaneous treatment (placebo, treatment as usual, or ineffec-

tive therapy) vs wait list or no treatment. All items were rated as low,

unclear, and high risk of bias, with items rated as unclear (eg, indi-

cated as randomized without further explanation) combined with

those having a high risk of bias in the statistical analysis. Moreover,

we analyzed how often follow-up data after the trial end point were

collected.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted in 4 steps.

1. We compared the sample sizes of psychotherapy and pharma-

cotherapy meta-analyses and their quality as measured by A Mea-

surement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) score.14

2. We compared the sample sizes and the methodologic quality of

the individualacute-phase studies included in the psycho-

therapy and pharmacotherapy meta-analyses with the Coch-

rane risk of bias tool.13The same analysis was performed on the

single disorders (Supplement [eAppendix 4, eFigures 1-7]).

3. We examined whether the meta-analyses conducted subgroup

comparisons on the risk of bias tool domains (eg, between stud-

ies using waiting lists or placebo), whether effects had re-

mained constant in follow-up assessments, and how often indi-

cations of publication bias were found.

4. We compared the mean baseline severity in pharmacotherapy and

psychotherapy trials on major depressive disorder (MDD) in-

cluded in evaluations by Turner et al15

and Cuijpers et al.16Because

such an analysis requires a sufficient number of studies for both

treatment modalities, it was not possible for other disorders.

Nonparametric tests were used throughout our study. Group means

were compared with Mann-Whitney tests and dichotomous data

with χ2tests; the α level was set at P < .05. Because all analyses were

considered exploratory rather than confirmatory, adjustments for

multiple testing were not made.

Results

The search retrieved 45 233 responses; 20 703 remained after elimi-

nation of duplicates. Detailed PRISMA flowcharts on the selection pro-

cess are provided in the Supplement (eAppendix 5).9 We included 61

meta-analyses (mean AMSTAR score, 8.4 [95% CI, 7.8-9.0]) on 21 dis-

orders (852 individual trials and 137 126 participants). Thirty-three

(54.1%) meta-analyses examined pharmacotherapy15,17-48

; 17

(27.9%), psychotherapy16,19,49-63

(most focused on CBT or specific

treatments; very few examined psychodynamic approaches50,59

);

7 (11.5%), direct comparisons49,59,64-68

; and 12, combination

therapies (19.7%)49,57,59,65,68-75

(several meta-analyses included

>1 comparison).

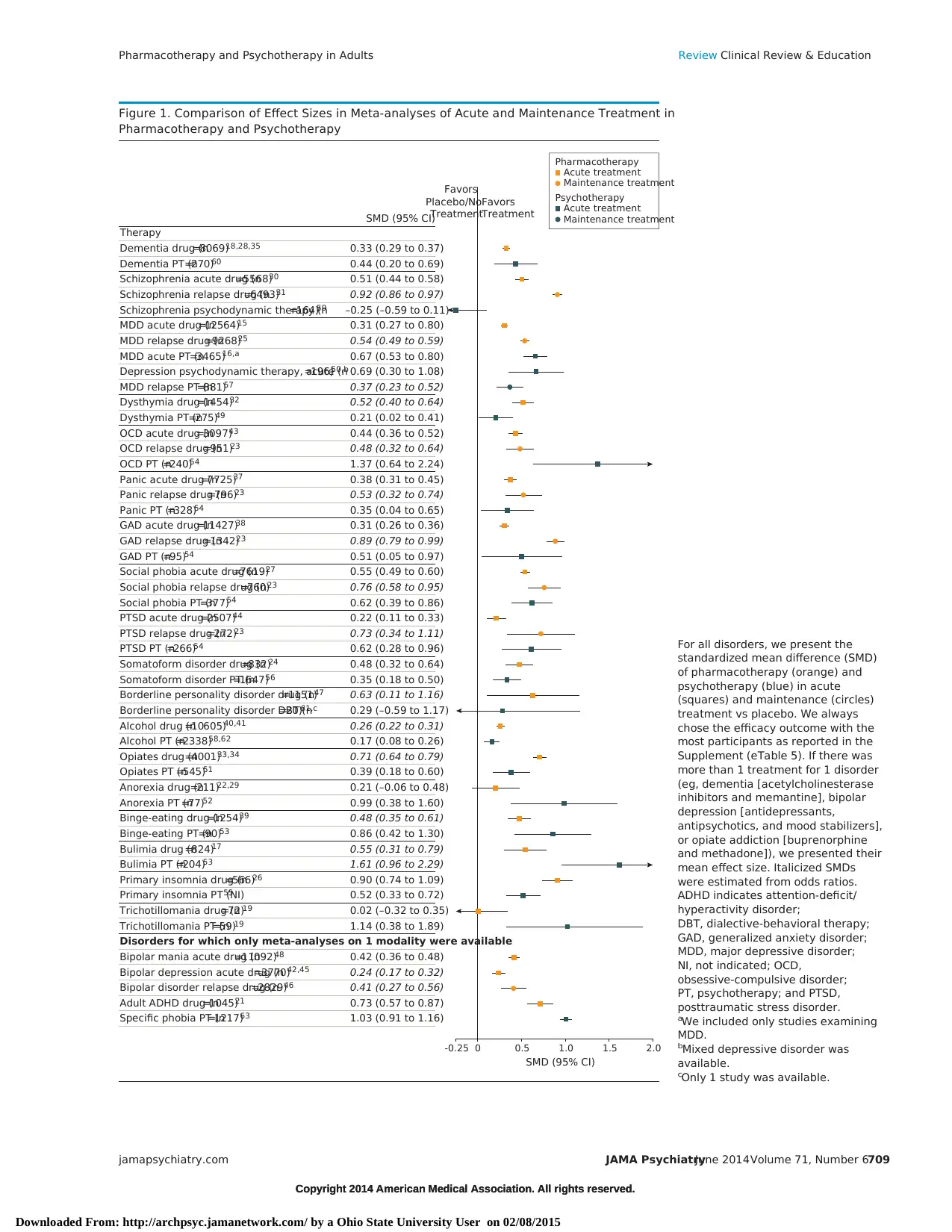

Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3 present the effect sizes in SMD

units. Because of the limitations of effect size estimates, we strongly

recommend that readers review the detailed narrative description

of the underlying meta-analyses, including the drug classes ana-

lyzed, responder rates, RRs, ARDs, NNTs, and SMDs in the Supple-

ment (eAppendix 6, with eTable 5). The sequence we used for our

report always follows the order of the disorders in the ICD-10.

Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy Compared With

Placebo or No Treatment

There were eligible reviews for at least one treatment modality for

all a priori–selected disorders except personality disorders other than

borderline personality disorder, impulse control disorders other than

trichotillomania, and substance-related disorders other than alco-

hol and opiate dependence (Figure 1). Most meta-analyses exam-

ined acute treatment; only 5 examined maintenance treatment. All

but 5 reviews demonstrated statistical significance compared with

placebo, which could be expected because only treatments recom-

mended by guidelines were chosen. However, the mean SMD of all

meta-analyses (0.50 [95% CI, 0.41-0.59]) suggests medium effi-

cacy of psychiatric treatments according to Cohen,8 and few treat-

ments had large effect sizes (mean SMD, ⱖ0.80).19,21,23,26,33,52-54,63

Acute-phase psychotherapy effect sizes for the same disorder tended

to be larger than those of pharmacotherapy (mean SMD, 0.40 [95%

CI, 0.28-0.52] vs 0.58 [0.40-0.76]). However, Figure 1 also shows

that the number of patients included in the acute-phase psycho-

therapy meta-analyses (median and mean sample sizes, 270 and 595,

respectively) was generally smaller than in the pharmacotherapy

studies (2507 and 3623) (U = 650.00; P < .001). The lower sample

sizes resulted in broader CIs and, thus, more uncertainty about the

true SMD. Finally, maintenance treatment with psychotropic drugs

was associated with consistently larger effect sizes than was acute

treatment.

Head-to-Head Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

Seven meta-analyses, often with small sample sizes (range, 92-

1662; median 375), on schizophrenia,59 MDD,64,67 dysthymic

disorder,49 panic disorder,68 generalized anxiety disorder,66 social

phobia,68 and bulimia65compared pharmacotherapy and psycho-

therapy head-to-head. Although there was a trend in favor of psy-

chotherapy, this trend was significant only for relapse prevention in

depression64and for bulimia65; pharmacotherapy was more effec-

tive for dysthymic disorder49and schizophrenia (compared with psy-

chodynamic therapy)59(Figure 2).

Combinations of Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

Twelve meta-analyses, also with small sample sizes (range, 23-

2131; median, 256) on schizophrenia,59,74MDD,70,71

dysthymic

disorder,49 bipolar disorder,57panic disorder,72,75

social phobia,68

posttraumatic stress disorder,73opiate addiction,69 and bulimia65

examined the effects of combining pharmacotherapy with psycho-

therapy.All analyses,except those on posttraumatic stress

Clinical Review & EducationReview Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Adults

708 JAMA PsychiatryJune 2014Volume 71, Number 6 jamapsychiatry.com

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

ity) and assessed their quality with the Cochrane risk of bias tool,13

which is based on scientific evidence of associations between over-

estimates of effect and methodologic shortcomings in the follow-

ing domains:

1. appropriate randomization (eg, computer-generated random-

ization sequence),

2. allocation concealment (eg, voice mail system),

3. blinding (because blinding of therapists is impossible in psycho-

therapy trials, we compared blind outcome assessment with no

blinding), and

4. missing outcomes (whether patients who withdrew from the

study and their reasons for withdrawal were reported, an inten-

tion-to-treat analysis was performed, and we also reported the

size of the overall dropout rate).

We did not examine the tool’s domain selective reporting but

added an item to the control groups that we classified as any con-

temporaneous treatment (placebo, treatment as usual, or ineffec-

tive therapy) vs wait list or no treatment. All items were rated as low,

unclear, and high risk of bias, with items rated as unclear (eg, indi-

cated as randomized without further explanation) combined with

those having a high risk of bias in the statistical analysis. Moreover,

we analyzed how often follow-up data after the trial end point were

collected.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted in 4 steps.

1. We compared the sample sizes of psychotherapy and pharma-

cotherapy meta-analyses and their quality as measured by A Mea-

surement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) score.14

2. We compared the sample sizes and the methodologic quality of

the individualacute-phase studies included in the psycho-

therapy and pharmacotherapy meta-analyses with the Coch-

rane risk of bias tool.13The same analysis was performed on the

single disorders (Supplement [eAppendix 4, eFigures 1-7]).

3. We examined whether the meta-analyses conducted subgroup

comparisons on the risk of bias tool domains (eg, between stud-

ies using waiting lists or placebo), whether effects had re-

mained constant in follow-up assessments, and how often indi-

cations of publication bias were found.

4. We compared the mean baseline severity in pharmacotherapy and

psychotherapy trials on major depressive disorder (MDD) in-

cluded in evaluations by Turner et al15

and Cuijpers et al.16Because

such an analysis requires a sufficient number of studies for both

treatment modalities, it was not possible for other disorders.

Nonparametric tests were used throughout our study. Group means

were compared with Mann-Whitney tests and dichotomous data

with χ2tests; the α level was set at P < .05. Because all analyses were

considered exploratory rather than confirmatory, adjustments for

multiple testing were not made.

Results

The search retrieved 45 233 responses; 20 703 remained after elimi-

nation of duplicates. Detailed PRISMA flowcharts on the selection pro-

cess are provided in the Supplement (eAppendix 5).9 We included 61

meta-analyses (mean AMSTAR score, 8.4 [95% CI, 7.8-9.0]) on 21 dis-

orders (852 individual trials and 137 126 participants). Thirty-three

(54.1%) meta-analyses examined pharmacotherapy15,17-48

; 17

(27.9%), psychotherapy16,19,49-63

(most focused on CBT or specific

treatments; very few examined psychodynamic approaches50,59

);

7 (11.5%), direct comparisons49,59,64-68

; and 12, combination

therapies (19.7%)49,57,59,65,68-75

(several meta-analyses included

>1 comparison).

Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3 present the effect sizes in SMD

units. Because of the limitations of effect size estimates, we strongly

recommend that readers review the detailed narrative description

of the underlying meta-analyses, including the drug classes ana-

lyzed, responder rates, RRs, ARDs, NNTs, and SMDs in the Supple-

ment (eAppendix 6, with eTable 5). The sequence we used for our

report always follows the order of the disorders in the ICD-10.

Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy Compared With

Placebo or No Treatment

There were eligible reviews for at least one treatment modality for

all a priori–selected disorders except personality disorders other than

borderline personality disorder, impulse control disorders other than

trichotillomania, and substance-related disorders other than alco-

hol and opiate dependence (Figure 1). Most meta-analyses exam-

ined acute treatment; only 5 examined maintenance treatment. All

but 5 reviews demonstrated statistical significance compared with

placebo, which could be expected because only treatments recom-

mended by guidelines were chosen. However, the mean SMD of all

meta-analyses (0.50 [95% CI, 0.41-0.59]) suggests medium effi-

cacy of psychiatric treatments according to Cohen,8 and few treat-

ments had large effect sizes (mean SMD, ⱖ0.80).19,21,23,26,33,52-54,63

Acute-phase psychotherapy effect sizes for the same disorder tended

to be larger than those of pharmacotherapy (mean SMD, 0.40 [95%

CI, 0.28-0.52] vs 0.58 [0.40-0.76]). However, Figure 1 also shows

that the number of patients included in the acute-phase psycho-

therapy meta-analyses (median and mean sample sizes, 270 and 595,

respectively) was generally smaller than in the pharmacotherapy

studies (2507 and 3623) (U = 650.00; P < .001). The lower sample

sizes resulted in broader CIs and, thus, more uncertainty about the

true SMD. Finally, maintenance treatment with psychotropic drugs

was associated with consistently larger effect sizes than was acute

treatment.

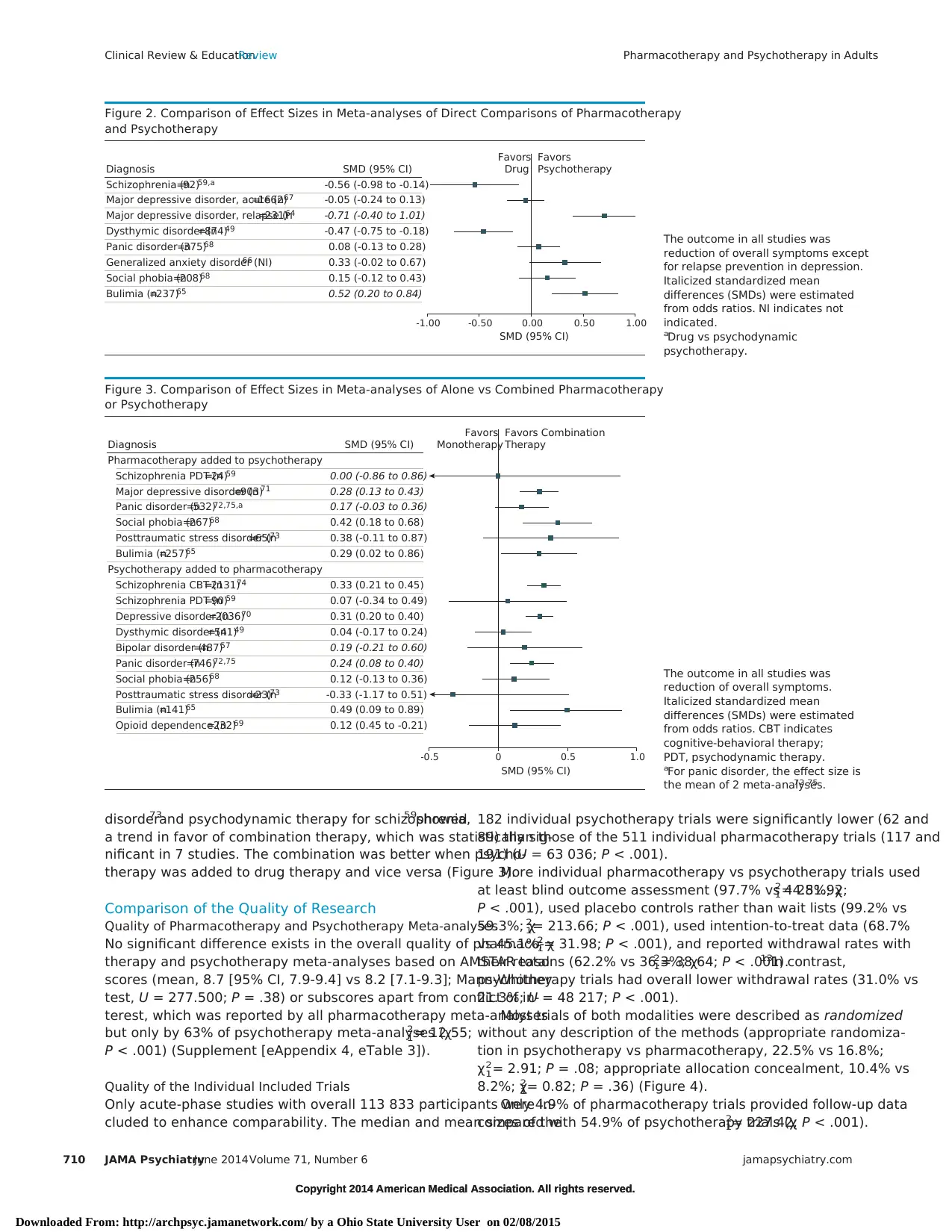

Head-to-Head Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

Seven meta-analyses, often with small sample sizes (range, 92-

1662; median 375), on schizophrenia,59 MDD,64,67 dysthymic

disorder,49 panic disorder,68 generalized anxiety disorder,66 social

phobia,68 and bulimia65compared pharmacotherapy and psycho-

therapy head-to-head. Although there was a trend in favor of psy-

chotherapy, this trend was significant only for relapse prevention in

depression64and for bulimia65; pharmacotherapy was more effec-

tive for dysthymic disorder49and schizophrenia (compared with psy-

chodynamic therapy)59(Figure 2).

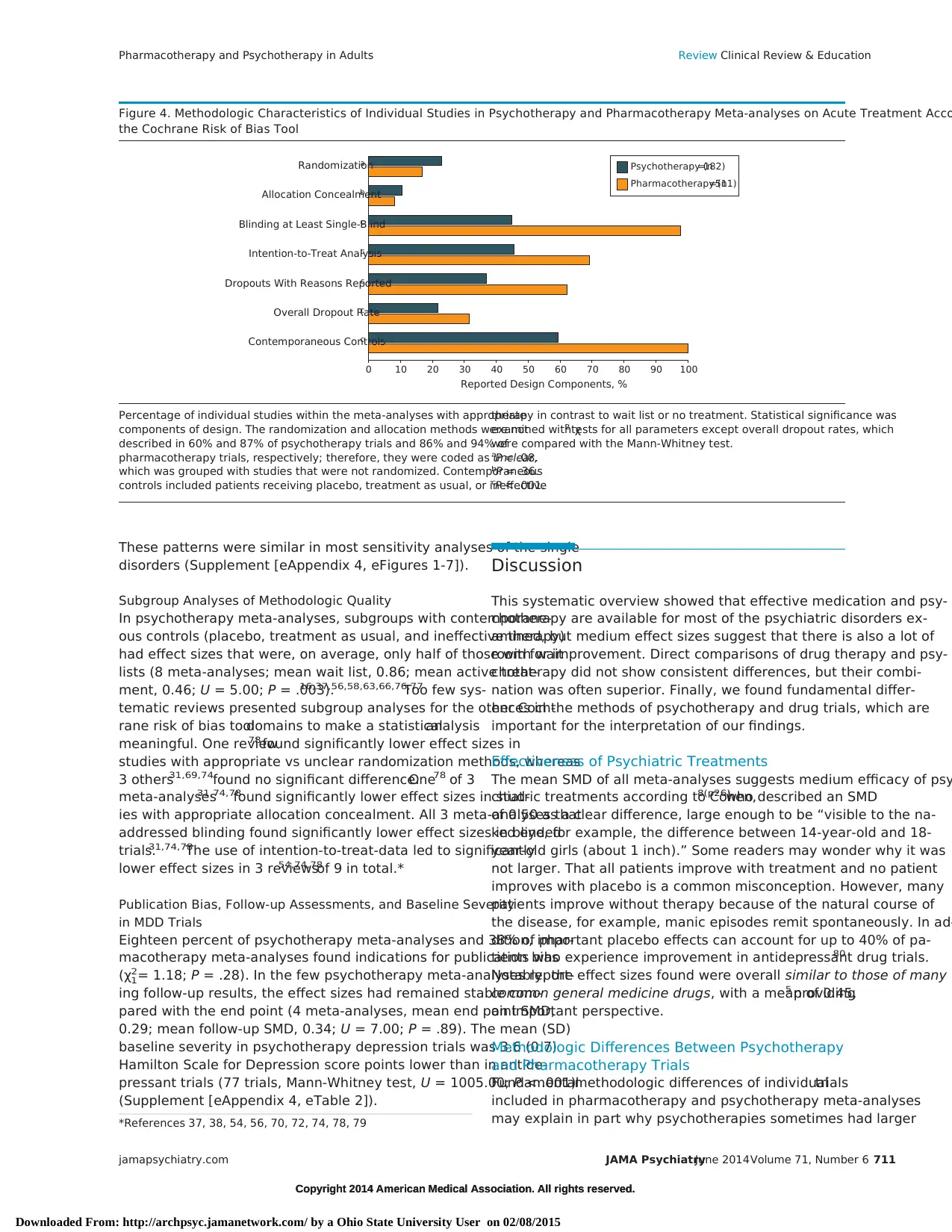

Combinations of Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

Twelve meta-analyses, also with small sample sizes (range, 23-

2131; median, 256) on schizophrenia,59,74MDD,70,71

dysthymic

disorder,49 bipolar disorder,57panic disorder,72,75

social phobia,68

posttraumatic stress disorder,73opiate addiction,69 and bulimia65

examined the effects of combining pharmacotherapy with psycho-

therapy.All analyses,except those on posttraumatic stress

Clinical Review & EducationReview Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Adults

708 JAMA PsychiatryJune 2014Volume 71, Number 6 jamapsychiatry.com

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Figure 1. Comparison of Effect Sizes in Meta-analyses of Acute and Maintenance Treatment in

Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

-0.25 1.0 2.00.5 1.5

SMD (95% CI)

0

Favors

Placebo/No

Treatment

Favors

Treatment

Therapy

SMD (95% CI)

0.33 (0.29 to 0.37)

0.44 (0.20 to 0.69)

0.51 (0.44 to 0.58)

0.92 (0.86 to 0.97)

–0.25 (–0.59 to 0.11)

0.31 (0.27 to 0.80)

0.54 (0.49 to 0.59)

0.67 (0.53 to 0.80)

0.69 (0.30 to 1.08)

0.37 (0.23 to 0.52)

0.52 (0.40 to 0.64)

0.21 (0.02 to 0.41)

0.44 (0.36 to 0.52)

0.48 (0.32 to 0.64)

1.37 (0.64 to 2.24)

0.38 (0.31 to 0.45)

0.53 (0.32 to 0.74)

0.35 (0.04 to 0.65)

0.31 (0.26 to 0.36)

0.89 (0.79 to 0.99)

0.51 (0.05 to 0.97)

0.55 (0.49 to 0.60)

0.76 (0.58 to 0.95)

0.62 (0.39 to 0.86)

0.22 (0.11 to 0.33)

0.73 (0.34 to 1.11)

0.62 (0.28 to 0.96)

0.48 (0.32 to 0.64)

0.35 (0.18 to 0.50)

0.63 (0.11 to 1.16)

0.29 (–0.59 to 1.17)

0.26 (0.22 to 0.31)

0.17 (0.08 to 0.26)

0.71 (0.64 to 0.79)

0.39 (0.18 to 0.60)

0.21 (–0.06 to 0.48)

0.99 (0.38 to 1.60)

0.48 (0.35 to 0.61)

0.86 (0.42 to 1.30)

0.55 (0.31 to 0.79)

1.61 (0.96 to 2.29)

0.90 (0.74 to 1.09)

0.52 (0.33 to 0.72)

0.02 (–0.32 to 0.35)

1.14 (0.38 to 1.89)

0.42 (0.36 to 0.48)

0.24 (0.17 to 0.32)

0.41 (0.27 to 0.56)

0.73 (0.57 to 0.87)

1.03 (0.91 to 1.16)

Dementia drug (n=8069)18,28,35

Dementia PT (n=270)60

Schizophrenia acute drug (n=5568)30

Schizophrenia relapse drug (n=6493)31

Schizophrenia psychodynamic therapy (n=164)59

MDD acute drug (n=12564)15

MDD relapse drug (n=9268)25

MDD acute PT (n=3465)16,a

Depression psychodynamic therapy, acute (n=196)50,b

MDD relapse PT (n=881)57

Dysthymia drug (n=1454)32

Dysthymia PT (n=275)49

OCD acute drug (n=3097)43

OCD relapse drug (n=951)23

OCD PT (n=240)54

Panic acute drug (n=7725)37

Panic relapse drug (n=796)23

Panic PT (n=328)54

GAD acute drug (n=11427)38

GAD relapse drug (n=1342)23

GAD PT (n=95)54

Social phobia acute drug (n=7619)27

Social phobia relapse drug (n=760)23

Social phobia PT (n=377)54

PTSD acute drug (n=2507)44

PTSD relapse drug (n=272)23

PTSD PT (n=266)54

Somatoform disorder drug (n=832)24

Somatoform disorder PT (n=1647)56

Borderline personality disorder drug (n=1151)47

Borderline personality disorder DBT (n=20)61,c

Alcohol drug (n=10605)40,41

Alcohol PT (n=2338)58,62

Opiates drug (n=4001)33,34

Opiates PT (n=545)51

Anorexia drug (n=211)22,29

Anorexia PT (n=77)52

Binge-eating drug (n=1254)39

Binge-eating PT (n=90)53

Bulimia drug (n=824)17

Bulimia PT (n=204)53

Primary insomnia drug (n=566)26

Primary insomnia PT (NI)55

Trichotillomania drug (n=72)19

Trichotillomania PT (n=59)19

Disorders for which only meta-analyses on 1 modality were available

Bipolar mania acute drug (n=11092)48

Bipolar depression acute drug (n=3770)42,45

Bipolar disorder relapse drug (n=2829)46

Adult ADHD drug (n=1045)21

Specific phobia PT (n=1217)63

Pharmacotherapy

Acute treatment

Maintenance treatment

Psychotherapy

Acute treatment

Maintenance treatment

For all disorders, we present the

standardized mean difference (SMD)

of pharmacotherapy (orange) and

psychotherapy (blue) in acute

(squares) and maintenance (circles)

treatment vs placebo. We always

chose the efficacy outcome with the

most participants as reported in the

Supplement (eTable 5). If there was

more than 1 treatment for 1 disorder

(eg, dementia [acetylcholinesterase

inhibitors and memantine], bipolar

depression [antidepressants,

antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers],

or opiate addiction [buprenorphine

and methadone]), we presented their

mean effect size. Italicized SMDs

were estimated from odds ratios.

ADHD indicates attention-deficit/

hyperactivity disorder;

DBT, dialective-behavioral therapy;

GAD, generalized anxiety disorder;

MDD, major depressive disorder;

NI, not indicated; OCD,

obsessive-compulsive disorder;

PT, psychotherapy; and PTSD,

posttraumatic stress disorder.

aWe included only studies examining

MDD.

bMixed depressive disorder was

available.

cOnly 1 study was available.

Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Adults Review Clinical Review & Education

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA PsychiatryJune 2014Volume 71, Number 6709

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

Figure 1. Comparison of Effect Sizes in Meta-analyses of Acute and Maintenance Treatment in

Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

-0.25 1.0 2.00.5 1.5

SMD (95% CI)

0

Favors

Placebo/No

Treatment

Favors

Treatment

Therapy

SMD (95% CI)

0.33 (0.29 to 0.37)

0.44 (0.20 to 0.69)

0.51 (0.44 to 0.58)

0.92 (0.86 to 0.97)

–0.25 (–0.59 to 0.11)

0.31 (0.27 to 0.80)

0.54 (0.49 to 0.59)

0.67 (0.53 to 0.80)

0.69 (0.30 to 1.08)

0.37 (0.23 to 0.52)

0.52 (0.40 to 0.64)

0.21 (0.02 to 0.41)

0.44 (0.36 to 0.52)

0.48 (0.32 to 0.64)

1.37 (0.64 to 2.24)

0.38 (0.31 to 0.45)

0.53 (0.32 to 0.74)

0.35 (0.04 to 0.65)

0.31 (0.26 to 0.36)

0.89 (0.79 to 0.99)

0.51 (0.05 to 0.97)

0.55 (0.49 to 0.60)

0.76 (0.58 to 0.95)

0.62 (0.39 to 0.86)

0.22 (0.11 to 0.33)

0.73 (0.34 to 1.11)

0.62 (0.28 to 0.96)

0.48 (0.32 to 0.64)

0.35 (0.18 to 0.50)

0.63 (0.11 to 1.16)

0.29 (–0.59 to 1.17)

0.26 (0.22 to 0.31)

0.17 (0.08 to 0.26)

0.71 (0.64 to 0.79)

0.39 (0.18 to 0.60)

0.21 (–0.06 to 0.48)

0.99 (0.38 to 1.60)

0.48 (0.35 to 0.61)

0.86 (0.42 to 1.30)

0.55 (0.31 to 0.79)

1.61 (0.96 to 2.29)

0.90 (0.74 to 1.09)

0.52 (0.33 to 0.72)

0.02 (–0.32 to 0.35)

1.14 (0.38 to 1.89)

0.42 (0.36 to 0.48)

0.24 (0.17 to 0.32)

0.41 (0.27 to 0.56)

0.73 (0.57 to 0.87)

1.03 (0.91 to 1.16)

Dementia drug (n=8069)18,28,35

Dementia PT (n=270)60

Schizophrenia acute drug (n=5568)30

Schizophrenia relapse drug (n=6493)31

Schizophrenia psychodynamic therapy (n=164)59

MDD acute drug (n=12564)15

MDD relapse drug (n=9268)25

MDD acute PT (n=3465)16,a

Depression psychodynamic therapy, acute (n=196)50,b

MDD relapse PT (n=881)57

Dysthymia drug (n=1454)32

Dysthymia PT (n=275)49

OCD acute drug (n=3097)43

OCD relapse drug (n=951)23

OCD PT (n=240)54

Panic acute drug (n=7725)37

Panic relapse drug (n=796)23

Panic PT (n=328)54

GAD acute drug (n=11427)38

GAD relapse drug (n=1342)23

GAD PT (n=95)54

Social phobia acute drug (n=7619)27

Social phobia relapse drug (n=760)23

Social phobia PT (n=377)54

PTSD acute drug (n=2507)44

PTSD relapse drug (n=272)23

PTSD PT (n=266)54

Somatoform disorder drug (n=832)24

Somatoform disorder PT (n=1647)56

Borderline personality disorder drug (n=1151)47

Borderline personality disorder DBT (n=20)61,c

Alcohol drug (n=10605)40,41

Alcohol PT (n=2338)58,62

Opiates drug (n=4001)33,34

Opiates PT (n=545)51

Anorexia drug (n=211)22,29

Anorexia PT (n=77)52

Binge-eating drug (n=1254)39

Binge-eating PT (n=90)53

Bulimia drug (n=824)17

Bulimia PT (n=204)53

Primary insomnia drug (n=566)26

Primary insomnia PT (NI)55

Trichotillomania drug (n=72)19

Trichotillomania PT (n=59)19

Disorders for which only meta-analyses on 1 modality were available

Bipolar mania acute drug (n=11092)48

Bipolar depression acute drug (n=3770)42,45

Bipolar disorder relapse drug (n=2829)46

Adult ADHD drug (n=1045)21

Specific phobia PT (n=1217)63

Pharmacotherapy

Acute treatment

Maintenance treatment

Psychotherapy

Acute treatment

Maintenance treatment

For all disorders, we present the

standardized mean difference (SMD)

of pharmacotherapy (orange) and

psychotherapy (blue) in acute

(squares) and maintenance (circles)

treatment vs placebo. We always

chose the efficacy outcome with the

most participants as reported in the

Supplement (eTable 5). If there was

more than 1 treatment for 1 disorder

(eg, dementia [acetylcholinesterase

inhibitors and memantine], bipolar

depression [antidepressants,

antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers],

or opiate addiction [buprenorphine

and methadone]), we presented their

mean effect size. Italicized SMDs

were estimated from odds ratios.

ADHD indicates attention-deficit/

hyperactivity disorder;

DBT, dialective-behavioral therapy;

GAD, generalized anxiety disorder;

MDD, major depressive disorder;

NI, not indicated; OCD,

obsessive-compulsive disorder;

PT, psychotherapy; and PTSD,

posttraumatic stress disorder.

aWe included only studies examining

MDD.

bMixed depressive disorder was

available.

cOnly 1 study was available.

Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Adults Review Clinical Review & Education

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA PsychiatryJune 2014Volume 71, Number 6709

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

disorder73

and psychodynamic therapy for schizophrenia,59showed

a trend in favor of combination therapy, which was statistically sig-

nificant in 7 studies. The combination was better when psycho-

therapy was added to drug therapy and vice versa (Figure 3).

Comparison of the Quality of Research

Quality of Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy Meta-analyses

No significant difference exists in the overall quality of pharmaco-

therapy and psychotherapy meta-analyses based on AMSTAR total

scores (mean, 8.7 [95% CI, 7.9-9.4] vs 8.2 [7.1-9.3]; Mann-Whitney

test, U = 277.500; P = .38) or subscores apart from conflict of in-

terest, which was reported by all pharmacotherapy meta-analyses

but only by 63% of psychotherapy meta-analyses (χ2

1 = 12.55;

P < .001) (Supplement [eAppendix 4, eTable 3]).

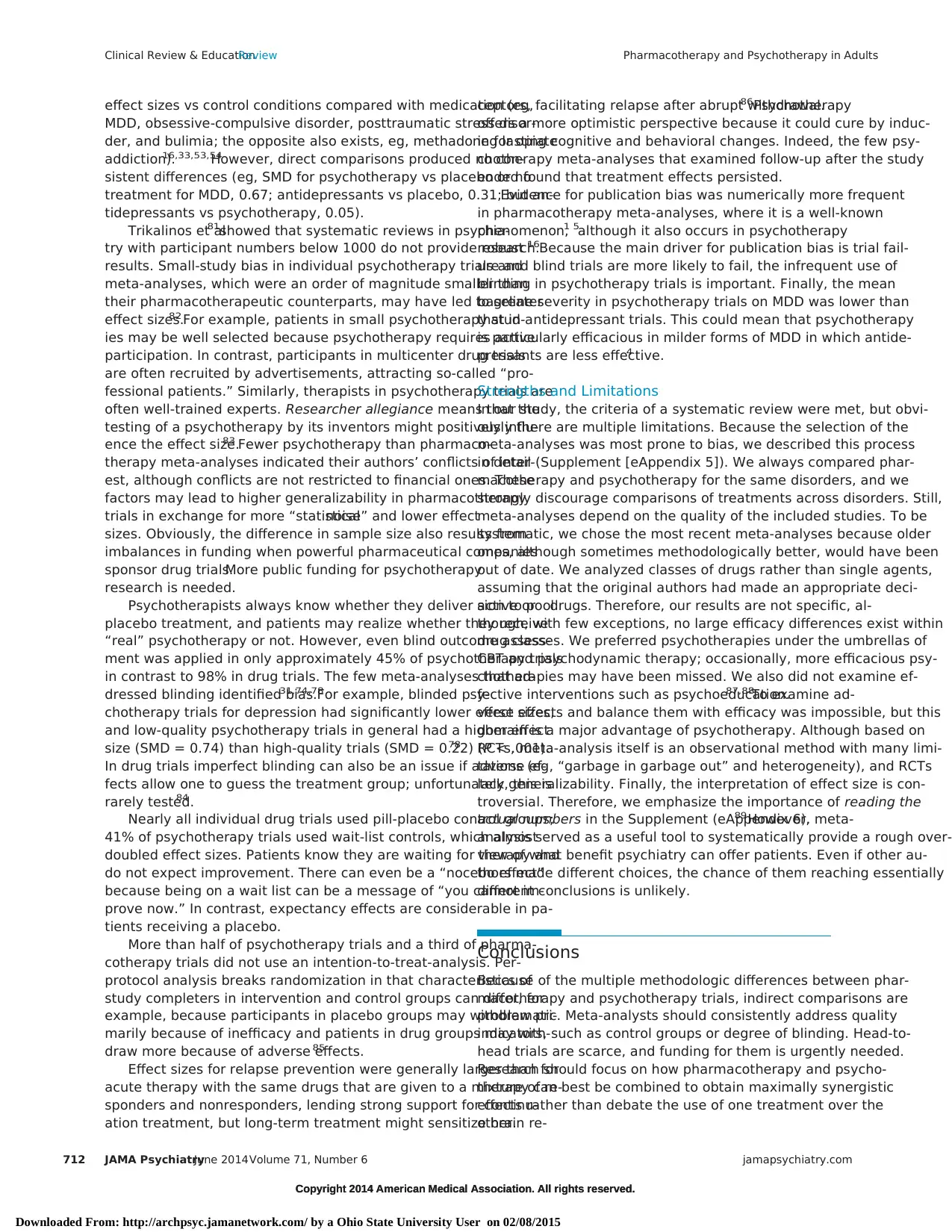

Quality of the Individual Included Trials

Only acute-phase studies with overall 113 833 participants were in-

cluded to enhance comparability. The median and mean sizes of the

182 individual psychotherapy trials were significantly lower (62 and

89) than those of the 511 individual pharmacotherapy trials (117 and

191) (U = 63 036; P < .001).

More individual pharmacotherapy vs psychotherapy trials used

at least blind outcome assessment (97.7% vs 44.5%; χ2

1= 281.92;

P < .001), used placebo controls rather than wait lists (99.2% vs

59.3%; χ2

1= 213.66; P < .001), used intention-to-treat data (68.7%

vs 45.1%; χ2

1= 31.98; P < .001), and reported withdrawal rates with

their reasons (62.2% vs 36.3%; χ2

1= 38.64; P < .001).13

In contrast,

psychotherapy trials had overall lower withdrawal rates (31.0% vs

21.3%; U = 48 217; P < .001).

Most trials of both modalities were described as randomized

without any description of the methods (appropriate randomiza-

tion in psychotherapy vs pharmacotherapy, 22.5% vs 16.8%;

χ 2

1= 2.91; P = .08; appropriate allocation concealment, 10.4% vs

8.2%; χ2

1= 0.82; P = .36) (Figure 4).

Only 4.9% of pharmacotherapy trials provided follow-up data

compared with 54.9% of psychotherapy trials (χ2

1= 227.42; P < .001).

Figure 3. Comparison of Effect Sizes in Meta-analyses of Alone vs Combined Pharmacotherapy

or Psychotherapy

-0.5 0.5 1.00

SMD (95% CI)

Favors

Monotherapy

Favors Combination

TherapyDiagnosis SMD (95% CI)

Schizophrenia PDT (n=24)59 0.00 (-0.86 to 0.86)

Major depressive disorder (n=903)71 0.28 (0.13 to 0.43)

Panic disorder (n=532)72,75,a 0.17 (-0.03 to 0.36)

Social phobia (n=267)68 0.42 (0.18 to 0.68)

Posttraumatic stress disorder (n=65)73 0.38 (-0.11 to 0.87)

Bulimia (n=257)65 0.29 (0.02 to 0.86)

Pharmacotherapy added to psychotherapy

Schizophrenia CBT (n=2131)74 0.33 (0.21 to 0.45)

Schizophrenia PDT (n=90)59 0.07 (-0.34 to 0.49)

Depressive disorder (n=2036)70 0.31 (0.20 to 0.40)

Dysthymic disorder (n=541)49 0.04 (-0.17 to 0.24)

Bipolar disorder (n=487)57 0.19 (-0.21 to 0.60)

Panic disorder (n=746)72,75 0.24 (0.08 to 0.40)

Psychotherapy added to pharmacotherapy

Social phobia (n=256)68 0.12 (-0.13 to 0.36)

Posttraumatic stress disorder (n=23)73 -0.33 (-1.17 to 0.51)

Bulimia (n=141)65 0.49 (0.09 to 0.89)

Opioid dependence (n=232)69 0.12 (0.45 to -0.21)

The outcome in all studies was

reduction of overall symptoms.

Italicized standardized mean

differences (SMDs) were estimated

from odds ratios. CBT indicates

cognitive-behavioral therapy;

PDT, psychodynamic therapy.

aFor panic disorder, the effect size is

the mean of 2 meta-analyses.72,75

Figure 2. Comparison of Effect Sizes in Meta-analyses of Direct Comparisons of Pharmacotherapy

and Psychotherapy

-1.00 0.50 1.000.00

SMD (95% CI)

-0.50

Favors

Drug

Favors

PsychotherapyDiagnosis SMD (95% CI)

Schizophrenia (n=92)59,a -0.56 (-0.98 to -0.14)

Major depressive disorder, acute (n=1662)67 -0.05 (-0.24 to 0.13)

Major depressive disorder, relapse (n=231)64 -0.71 (-0.40 to 1.01)

Dysthymic disorder (n=874)49 -0.47 (-0.75 to -0.18)

Panic disorder (n=375)68 0.08 (-0.13 to 0.28)

Generalized anxiety disorder (NI)66 0.33 (-0.02 to 0.67)

Social phobia (n=208)68 0.15 (-0.12 to 0.43)

Bulimia (n=237)65 0.52 (0.20 to 0.84)

The outcome in all studies was

reduction of overall symptoms except

for relapse prevention in depression.

Italicized standardized mean

differences (SMDs) were estimated

from odds ratios. NI indicates not

indicated.

aDrug vs psychodynamic

psychotherapy.

Clinical Review & EducationReview Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Adults

710 JAMA PsychiatryJune 2014Volume 71, Number 6 jamapsychiatry.com

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

disorder73

and psychodynamic therapy for schizophrenia,59showed

a trend in favor of combination therapy, which was statistically sig-

nificant in 7 studies. The combination was better when psycho-

therapy was added to drug therapy and vice versa (Figure 3).

Comparison of the Quality of Research

Quality of Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy Meta-analyses

No significant difference exists in the overall quality of pharmaco-

therapy and psychotherapy meta-analyses based on AMSTAR total

scores (mean, 8.7 [95% CI, 7.9-9.4] vs 8.2 [7.1-9.3]; Mann-Whitney

test, U = 277.500; P = .38) or subscores apart from conflict of in-

terest, which was reported by all pharmacotherapy meta-analyses

but only by 63% of psychotherapy meta-analyses (χ2

1 = 12.55;

P < .001) (Supplement [eAppendix 4, eTable 3]).

Quality of the Individual Included Trials

Only acute-phase studies with overall 113 833 participants were in-

cluded to enhance comparability. The median and mean sizes of the

182 individual psychotherapy trials were significantly lower (62 and

89) than those of the 511 individual pharmacotherapy trials (117 and

191) (U = 63 036; P < .001).

More individual pharmacotherapy vs psychotherapy trials used

at least blind outcome assessment (97.7% vs 44.5%; χ2

1= 281.92;

P < .001), used placebo controls rather than wait lists (99.2% vs

59.3%; χ2

1= 213.66; P < .001), used intention-to-treat data (68.7%

vs 45.1%; χ2

1= 31.98; P < .001), and reported withdrawal rates with

their reasons (62.2% vs 36.3%; χ2

1= 38.64; P < .001).13

In contrast,

psychotherapy trials had overall lower withdrawal rates (31.0% vs

21.3%; U = 48 217; P < .001).

Most trials of both modalities were described as randomized

without any description of the methods (appropriate randomiza-

tion in psychotherapy vs pharmacotherapy, 22.5% vs 16.8%;

χ 2

1= 2.91; P = .08; appropriate allocation concealment, 10.4% vs

8.2%; χ2

1= 0.82; P = .36) (Figure 4).

Only 4.9% of pharmacotherapy trials provided follow-up data

compared with 54.9% of psychotherapy trials (χ2

1= 227.42; P < .001).

Figure 3. Comparison of Effect Sizes in Meta-analyses of Alone vs Combined Pharmacotherapy

or Psychotherapy

-0.5 0.5 1.00

SMD (95% CI)

Favors

Monotherapy

Favors Combination

TherapyDiagnosis SMD (95% CI)

Schizophrenia PDT (n=24)59 0.00 (-0.86 to 0.86)

Major depressive disorder (n=903)71 0.28 (0.13 to 0.43)

Panic disorder (n=532)72,75,a 0.17 (-0.03 to 0.36)

Social phobia (n=267)68 0.42 (0.18 to 0.68)

Posttraumatic stress disorder (n=65)73 0.38 (-0.11 to 0.87)

Bulimia (n=257)65 0.29 (0.02 to 0.86)

Pharmacotherapy added to psychotherapy

Schizophrenia CBT (n=2131)74 0.33 (0.21 to 0.45)

Schizophrenia PDT (n=90)59 0.07 (-0.34 to 0.49)

Depressive disorder (n=2036)70 0.31 (0.20 to 0.40)

Dysthymic disorder (n=541)49 0.04 (-0.17 to 0.24)

Bipolar disorder (n=487)57 0.19 (-0.21 to 0.60)

Panic disorder (n=746)72,75 0.24 (0.08 to 0.40)

Psychotherapy added to pharmacotherapy

Social phobia (n=256)68 0.12 (-0.13 to 0.36)

Posttraumatic stress disorder (n=23)73 -0.33 (-1.17 to 0.51)

Bulimia (n=141)65 0.49 (0.09 to 0.89)

Opioid dependence (n=232)69 0.12 (0.45 to -0.21)

The outcome in all studies was

reduction of overall symptoms.

Italicized standardized mean

differences (SMDs) were estimated

from odds ratios. CBT indicates

cognitive-behavioral therapy;

PDT, psychodynamic therapy.

aFor panic disorder, the effect size is

the mean of 2 meta-analyses.72,75

Figure 2. Comparison of Effect Sizes in Meta-analyses of Direct Comparisons of Pharmacotherapy

and Psychotherapy

-1.00 0.50 1.000.00

SMD (95% CI)

-0.50

Favors

Drug

Favors

PsychotherapyDiagnosis SMD (95% CI)

Schizophrenia (n=92)59,a -0.56 (-0.98 to -0.14)

Major depressive disorder, acute (n=1662)67 -0.05 (-0.24 to 0.13)

Major depressive disorder, relapse (n=231)64 -0.71 (-0.40 to 1.01)

Dysthymic disorder (n=874)49 -0.47 (-0.75 to -0.18)

Panic disorder (n=375)68 0.08 (-0.13 to 0.28)

Generalized anxiety disorder (NI)66 0.33 (-0.02 to 0.67)

Social phobia (n=208)68 0.15 (-0.12 to 0.43)

Bulimia (n=237)65 0.52 (0.20 to 0.84)

The outcome in all studies was

reduction of overall symptoms except

for relapse prevention in depression.

Italicized standardized mean

differences (SMDs) were estimated

from odds ratios. NI indicates not

indicated.

aDrug vs psychodynamic

psychotherapy.

Clinical Review & EducationReview Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Adults

710 JAMA PsychiatryJune 2014Volume 71, Number 6 jamapsychiatry.com

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

These patterns were similar in most sensitivity analyses of the single

disorders (Supplement [eAppendix 4, eFigures 1-7]).

Subgroup Analyses of Methodologic Quality

In psychotherapy meta-analyses, subgroups with contemporane-

ous controls (placebo, treatment as usual, and ineffective therapy)

had effect sizes that were, on average, only half of those with wait

lists (8 meta-analyses; mean wait list, 0.86; mean active treat-

ment, 0.46; U = 5.00; P = .003).16,37,56,58,63,66,76,77

Too few sys-

tematic reviews presented subgroup analyses for the other Coch-

rane risk of bias tooldomains to make a statisticalanalysis

meaningful. One review78 found significantly lower effect sizes in

studies with appropriate vs unclear randomization methods, whereas

3 others31,69,74found no significant difference.One78 of 3

meta-analyses31,74,78

found significantly lower effect sizes in stud-

ies with appropriate allocation concealment. All 3 meta-analyses that

addressed blinding found significantly lower effect sizes in blinded

trials.31,74,78

The use of intention-to-treat-data led to significantly

lower effect sizes in 3 reviews54,74,78

of 9 in total.*

Publication Bias, Follow-up Assessments, and Baseline Severity

in MDD Trials

Eighteen percent of psychotherapy meta-analyses and 38% of phar-

macotherapy meta-analyses found indications for publication bias

(χ2

1= 1.18; P = .28). In the few psychotherapy meta-analyses report-

ing follow-up results, the effect sizes had remained stable com-

pared with the end point (4 meta-analyses, mean end point SMD,

0.29; mean follow-up SMD, 0.34; U = 7.00; P = .89). The mean (SD)

baseline severity in psychotherapy depression trials was 3.6 (0.7)

Hamilton Scale for Depression score points lower than in antide-

pressant trials (77 trials, Mann-Whitney test, U = 1005.00; P < .001)

(Supplement [eAppendix 4, eTable 2]).

Discussion

This systematic overview showed that effective medication and psy-

chotherapy are available for most of the psychiatric disorders ex-

amined, but medium effect sizes suggest that there is also a lot of

room for improvement. Direct comparisons of drug therapy and psy-

chotherapy did not show consistent differences, but their combi-

nation was often superior. Finally, we found fundamental differ-

ences in the methods of psychotherapy and drug trials, which are

important for the interpretation of our findings.

Effectiveness of Psychiatric Treatments

The mean SMD of all meta-analyses suggests medium efficacy of psy

chiatric treatments according to Cohen,8(p26)

who described an SMD

of 0.50 as a clear difference, large enough to be “visible to the na-

ked eye, for example, the difference between 14-year-old and 18-

year-old girls (about 1 inch).” Some readers may wonder why it was

not larger. That all patients improve with treatment and no patient

improves with placebo is a common misconception. However, many

patients improve without therapy because of the natural course of

the disease, for example, manic episodes remit spontaneously. In ad-

dition, important placebo effects can account for up to 40% of pa-

tients who experience improvement in antidepressant drug trials.80

Notably, the effect sizes found were overall similar to those of many

common general medicine drugs, with a mean of 0.45,5 providing

an important perspective.

Methodologic Differences Between Psychotherapy

and Pharmacotherapy Trials

Fundamentalmethodologic differences of individualtrials

included in pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy meta-analyses

may explain in part why psychotherapies sometimes had larger*References 37, 38, 54, 56, 70, 72, 74, 78, 79

Figure 4. Methodologic Characteristics of Individual Studies in Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy Meta-analyses on Acute Treatment Acco

the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool

Contemporaneous Controlsc

Overall Dropout Ratec

Dropouts With Reasons Reportedc

Intention-to-Treat Analysisc

Blinding at Least Single-Blindc

Allocation Concealmentb

Randomizationa

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Reported Design Components, %

Psychotherapy (n=182)

Pharmacotherapy (n=511)

Percentage of individual studies within the meta-analyses with appropriate

components of design. The randomization and allocation methods were not

described in 60% and 87% of psychotherapy trials and 86% and 94% of

pharmacotherapy trials, respectively; therefore, they were coded as unclear,

which was grouped with studies that were not randomized. Contemporaneous

controls included patients receiving placebo, treatment as usual, or ineffective

therapy in contrast to wait list or no treatment. Statistical significance was

examined with χ2 tests for all parameters except overall dropout rates, which

were compared with the Mann-Whitney test.

aP = .08.

bP = .36.

cP < .001.

Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Adults Review Clinical Review & Education

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA PsychiatryJune 2014Volume 71, Number 6 711

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

These patterns were similar in most sensitivity analyses of the single

disorders (Supplement [eAppendix 4, eFigures 1-7]).

Subgroup Analyses of Methodologic Quality

In psychotherapy meta-analyses, subgroups with contemporane-

ous controls (placebo, treatment as usual, and ineffective therapy)

had effect sizes that were, on average, only half of those with wait

lists (8 meta-analyses; mean wait list, 0.86; mean active treat-

ment, 0.46; U = 5.00; P = .003).16,37,56,58,63,66,76,77

Too few sys-

tematic reviews presented subgroup analyses for the other Coch-

rane risk of bias tooldomains to make a statisticalanalysis

meaningful. One review78 found significantly lower effect sizes in

studies with appropriate vs unclear randomization methods, whereas

3 others31,69,74found no significant difference.One78 of 3

meta-analyses31,74,78

found significantly lower effect sizes in stud-

ies with appropriate allocation concealment. All 3 meta-analyses that

addressed blinding found significantly lower effect sizes in blinded

trials.31,74,78

The use of intention-to-treat-data led to significantly

lower effect sizes in 3 reviews54,74,78

of 9 in total.*

Publication Bias, Follow-up Assessments, and Baseline Severity

in MDD Trials

Eighteen percent of psychotherapy meta-analyses and 38% of phar-

macotherapy meta-analyses found indications for publication bias

(χ2

1= 1.18; P = .28). In the few psychotherapy meta-analyses report-

ing follow-up results, the effect sizes had remained stable com-

pared with the end point (4 meta-analyses, mean end point SMD,

0.29; mean follow-up SMD, 0.34; U = 7.00; P = .89). The mean (SD)

baseline severity in psychotherapy depression trials was 3.6 (0.7)

Hamilton Scale for Depression score points lower than in antide-

pressant trials (77 trials, Mann-Whitney test, U = 1005.00; P < .001)

(Supplement [eAppendix 4, eTable 2]).

Discussion

This systematic overview showed that effective medication and psy-

chotherapy are available for most of the psychiatric disorders ex-

amined, but medium effect sizes suggest that there is also a lot of

room for improvement. Direct comparisons of drug therapy and psy-

chotherapy did not show consistent differences, but their combi-

nation was often superior. Finally, we found fundamental differ-

ences in the methods of psychotherapy and drug trials, which are

important for the interpretation of our findings.

Effectiveness of Psychiatric Treatments

The mean SMD of all meta-analyses suggests medium efficacy of psy

chiatric treatments according to Cohen,8(p26)

who described an SMD

of 0.50 as a clear difference, large enough to be “visible to the na-

ked eye, for example, the difference between 14-year-old and 18-

year-old girls (about 1 inch).” Some readers may wonder why it was

not larger. That all patients improve with treatment and no patient

improves with placebo is a common misconception. However, many

patients improve without therapy because of the natural course of

the disease, for example, manic episodes remit spontaneously. In ad-

dition, important placebo effects can account for up to 40% of pa-

tients who experience improvement in antidepressant drug trials.80

Notably, the effect sizes found were overall similar to those of many

common general medicine drugs, with a mean of 0.45,5 providing

an important perspective.

Methodologic Differences Between Psychotherapy

and Pharmacotherapy Trials

Fundamentalmethodologic differences of individualtrials

included in pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy meta-analyses

may explain in part why psychotherapies sometimes had larger*References 37, 38, 54, 56, 70, 72, 74, 78, 79

Figure 4. Methodologic Characteristics of Individual Studies in Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy Meta-analyses on Acute Treatment Acco

the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool

Contemporaneous Controlsc

Overall Dropout Ratec

Dropouts With Reasons Reportedc

Intention-to-Treat Analysisc

Blinding at Least Single-Blindc

Allocation Concealmentb

Randomizationa

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Reported Design Components, %

Psychotherapy (n=182)

Pharmacotherapy (n=511)

Percentage of individual studies within the meta-analyses with appropriate

components of design. The randomization and allocation methods were not

described in 60% and 87% of psychotherapy trials and 86% and 94% of

pharmacotherapy trials, respectively; therefore, they were coded as unclear,

which was grouped with studies that were not randomized. Contemporaneous

controls included patients receiving placebo, treatment as usual, or ineffective

therapy in contrast to wait list or no treatment. Statistical significance was

examined with χ2 tests for all parameters except overall dropout rates, which

were compared with the Mann-Whitney test.

aP = .08.

bP = .36.

cP < .001.

Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Adults Review Clinical Review & Education

jamapsychiatry.com JAMA PsychiatryJune 2014Volume 71, Number 6 711

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ by a Ohio State University User on 02/08/2015

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

effect sizes vs control conditions compared with medication (eg,

MDD, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disor-

der, and bulimia; the opposite also exists, eg, methadone for opiate

addiction).16,33,53,54

However, direct comparisons produced no con-

sistent differences (eg, SMD for psychotherapy vs placebo or no

treatment for MDD, 0.67; antidepressants vs placebo, 0.31; but an-

tidepressants vs psychotherapy, 0.05).

Trikalinos et al81showed that systematic reviews in psychia-

try with participant numbers below 1000 do not provide robust

results. Small-study bias in individual psychotherapy trials and

meta-analyses, which were an order of magnitude smaller than

their pharmacotherapeutic counterparts, may have led to greater

effect sizes.82 For example, patients in small psychotherapy stud-

ies may be well selected because psychotherapy requires active

participation. In contrast, participants in multicenter drug trials

are often recruited by advertisements, attracting so-called “pro-

fessional patients.” Similarly, therapists in psychotherapy trials are

often well-trained experts. Researcher allegiance means that the

testing of a psychotherapy by its inventors might positively influ-

ence the effect size.83 Fewer psychotherapy than pharmaco-

therapy meta-analyses indicated their authors’ conflicts of inter-

est, although conflicts are not restricted to financial ones. These

factors may lead to higher generalizability in pharmacotherapy

trials in exchange for more “statisticalnoise” and lower effect

sizes. Obviously, the difference in sample size also results from

imbalances in funding when powerful pharmaceutical companies

sponsor drug trials.More public funding for psychotherapy

research is needed.

Psychotherapists always know whether they deliver active or

placebo treatment, and patients may realize whether they receive

“real” psychotherapy or not. However, even blind outcome assess-

ment was applied in only approximately 45% of psychotherapy trials

in contrast to 98% in drug trials. The few meta-analyses that ad-

dressed blinding identified bias.31,74,78

For example, blinded psy-

chotherapy trials for depression had significantly lower effect sizes,

and low-quality psychotherapy trials in general had a higher effect

size (SMD = 0.74) than high-quality trials (SMD = 0.22) (P < .001).78

In drug trials imperfect blinding can also be an issue if adverse ef-

fects allow one to guess the treatment group; unfortunately, this is

rarely tested.84

Nearly all individual drug trials used pill-placebo control groups;

41% of psychotherapy trials used wait-list controls, which almost

doubled effect sizes. Patients know they are waiting for therapy and

do not expect improvement. There can even be a “nocebo effect”

because being on a wait list can be a message of “you cannot im-

prove now.” In contrast, expectancy effects are considerable in pa-

tients receiving a placebo.

More than half of psychotherapy trials and a third of pharma-

cotherapy trials did not use an intention-to-treat-analysis. Per-

protocol analysis breaks randomization in that characteristics of

study completers in intervention and control groups can differ, for

example, because participants in placebo groups may withdraw pri-

marily because of inefficacy and patients in drug groups may with-

draw more because of adverse effects.85

Effect sizes for relapse prevention were generally larger than for

acute therapy with the same drugs that are given to a mixture of re-

sponders and nonresponders, lending strong support for continu-

ation treatment, but long-term treatment might sensitize brain re-

ceptors, facilitating relapse after abrupt withdrawal.86Psychotherapy

offers a more optimistic perspective because it could cure by induc-

ing lasting cognitive and behavioral changes. Indeed, the few psy-

chotherapy meta-analyses that examined follow-up after the study

ended found that treatment effects persisted.

Evidence for publication bias was numerically more frequent

in pharmacotherapy meta-analyses, where it is a well-known

phenomenon,1 5although it also occurs in psychotherapy

research.16Because the main driver for publication bias is trial fail-

ure and blind trials are more likely to fail, the infrequent use of

blinding in psychotherapy trials is important. Finally, the mean

baseline severity in psychotherapy trials on MDD was lower than

that in antidepressant trials. This could mean that psychotherapy

is particularly efficacious in milder forms of MDD in which antide-

pressants are less effective.4

Strengths and Limitations

In our study, the criteria of a systematic review were met, but obvi-

ously there are multiple limitations. Because the selection of the

meta-analyses was most prone to bias, we described this process

in detail (Supplement [eAppendix 5]). We always compared phar-

macotherapy and psychotherapy for the same disorders, and we

strongly discourage comparisons of treatments across disorders. Still,

meta-analyses depend on the quality of the included studies. To be

systematic, we chose the most recent meta-analyses because older

ones, although sometimes methodologically better, would have been

out of date. We analyzed classes of drugs rather than single agents,

assuming that the original authors had made an appropriate deci-

sion to pooldrugs. Therefore, our results are not specific, al-

though, with few exceptions, no large efficacy differences exist within

drug classes. We preferred psychotherapies under the umbrellas of

CBT and psychodynamic therapy; occasionally, more efficacious psy-

chotherapies may have been missed. We also did not examine ef-

fective interventions such as psychoeducation.87,88

To examine ad-

verse effects and balance them with efficacy was impossible, but this

domain is a major advantage of psychotherapy. Although based on