Residential Care EHR Adoption: An Analysis of NCHS Data Brief 128

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/13

|8

|3339

|84

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on the 2010 National Survey of Residential Care Facilities (NSRCF) data from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), examines the adoption and usage of electronic health records (EHRs) in residential care communities across the United States. The study reveals that only 17% of residential care communities used EHRs in 2010, with adoption rates varying based on facility characteristics such as size, ownership, chain affiliation, and location. Facilities using EHRs were more likely to be larger, not-for-profit, chain-affiliated, colocated with other care settings, and located in non-metropolitan areas. The most common types of resident health information tracked electronically included medical provider information, resident demographics, individual service plans, and medication lists. Furthermore, 40% of facilities with EHRs supported electronic health information exchange with other providers, particularly pharmacies. The findings provide baseline data relevant to discussions on improving care coordination, reducing rehospitalizations, and managing chronic conditions in residential care settings.

NCHS Data Brief ■ No. 128 ■ September 2013

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

Use of Electronic Health Records in

Residential Care Communities

Christine Caffrey, Ph.D., and Eunice Park-Lee, Ph.D.

Key findings

• In 2010, only 17% of

residential care communities

in the United States used

electronic health records.

• Residential care

communities that used

electronic health records

were more likely to be

larger, not-for-profit, chain-

affiliated, colocated with

another care setting, and in a

nonmetropolitan statistical area.

• The types of information

most commonly tracked

electronically by residential

care communities that used

electronic health records were

medical provider information,

resident demographics,

individual service plans, and

lists of residents’ medications

and active medication allergies.

• Four in 10 residential

care communities that used

electronic health records also

had support for electronic

exchange of health information

with service providers; nearly

25% could exchange with

pharmacies, and 17% could

exchange with physicians.

The ability to record and exchange health information electronically is

believed to improve the quality and efficiency of health care (1–4). It also has

the potential to increase coordination of care across a continuum of providers,

decrease duplication of testing (5), and allow providers timely access to

necessary health information. Although research has been done in other health

care settings (6–9), little has been focused on residential care communities’

use of electronic health records and their support for electronic exchange of

resident health information (10). This report provides baseline findings using

data from the 2010 National Survey of Residential Care Facilities (NSRCF).

Keywords: long-term care • health information technology • National Survey

of Residential Care Facilities

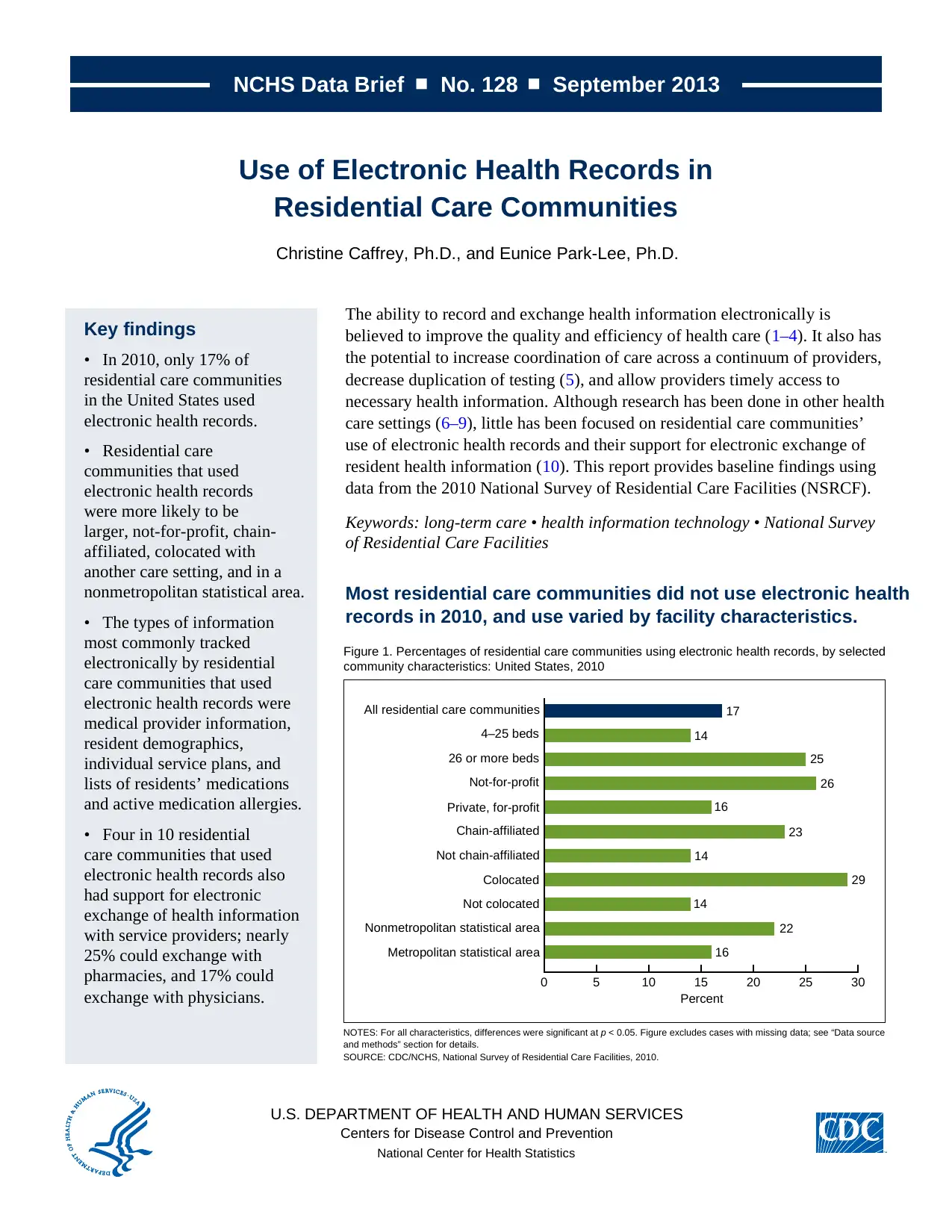

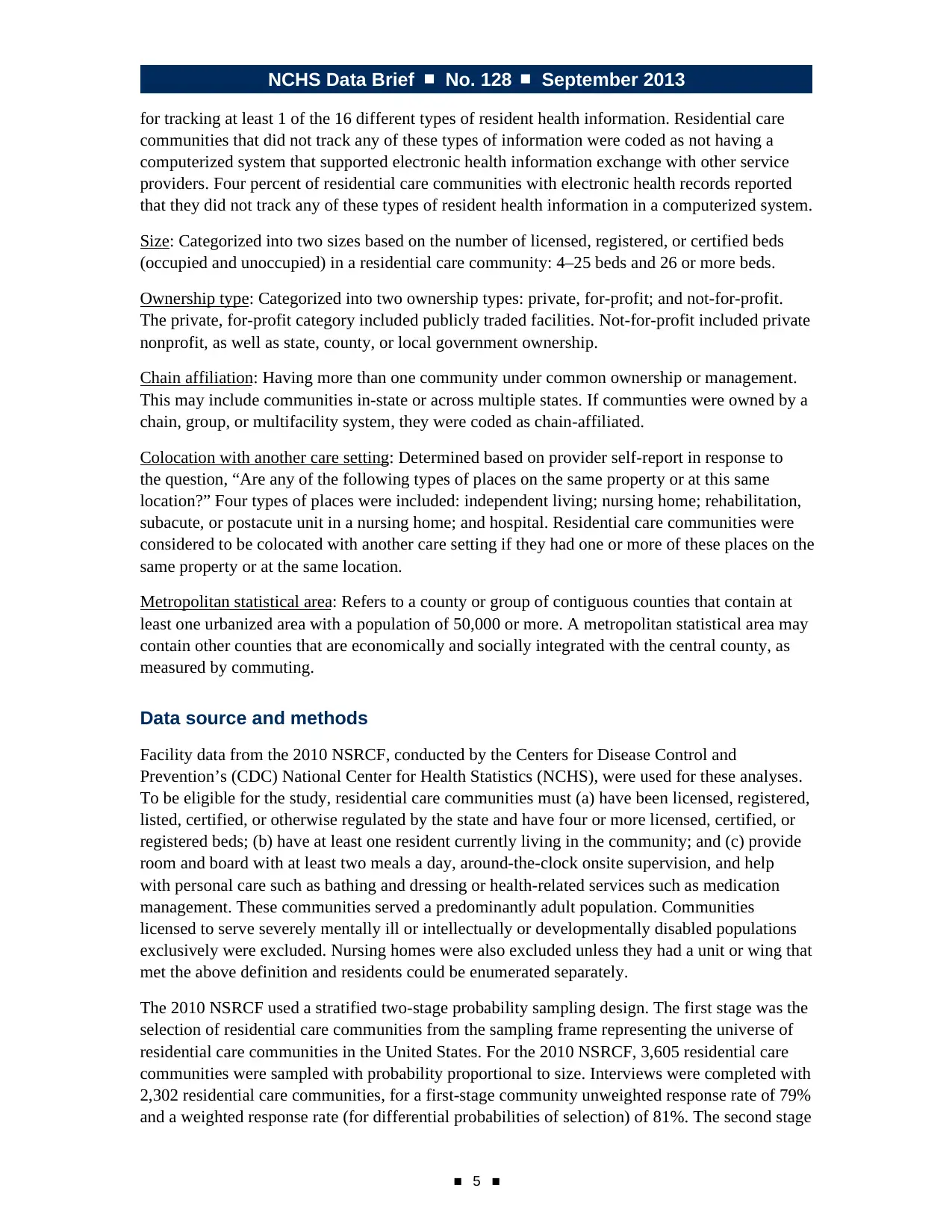

Most residential care communities did not use electronic health

records in 2010, and use varied by facility characteristics.

NOTES: For all characteristics, differences were significant at p < 0.05. Figure excludes cases with missing data; see “Data source

and methods” section for details.

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Survey of Residential Care Facilities, 2010.

Figure 1. Percentages of residential care communities using electronic health records, by selected

community characteristics: United States, 2010

0 5 10 15

Percent

20 25 30

All residential care communities 17

4–25 beds 14

26 or more beds 25

Not-for-profit 26

Private, for-profit 16

Chain-affiliated 23

Not chain-affiliated 14

Colocated 29

Not colocated 14

Nonmetropolitan statistical area 22

Metropolitan statistical area 16

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

Use of Electronic Health Records in

Residential Care Communities

Christine Caffrey, Ph.D., and Eunice Park-Lee, Ph.D.

Key findings

• In 2010, only 17% of

residential care communities

in the United States used

electronic health records.

• Residential care

communities that used

electronic health records

were more likely to be

larger, not-for-profit, chain-

affiliated, colocated with

another care setting, and in a

nonmetropolitan statistical area.

• The types of information

most commonly tracked

electronically by residential

care communities that used

electronic health records were

medical provider information,

resident demographics,

individual service plans, and

lists of residents’ medications

and active medication allergies.

• Four in 10 residential

care communities that used

electronic health records also

had support for electronic

exchange of health information

with service providers; nearly

25% could exchange with

pharmacies, and 17% could

exchange with physicians.

The ability to record and exchange health information electronically is

believed to improve the quality and efficiency of health care (1–4). It also has

the potential to increase coordination of care across a continuum of providers,

decrease duplication of testing (5), and allow providers timely access to

necessary health information. Although research has been done in other health

care settings (6–9), little has been focused on residential care communities’

use of electronic health records and their support for electronic exchange of

resident health information (10). This report provides baseline findings using

data from the 2010 National Survey of Residential Care Facilities (NSRCF).

Keywords: long-term care • health information technology • National Survey

of Residential Care Facilities

Most residential care communities did not use electronic health

records in 2010, and use varied by facility characteristics.

NOTES: For all characteristics, differences were significant at p < 0.05. Figure excludes cases with missing data; see “Data source

and methods” section for details.

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Survey of Residential Care Facilities, 2010.

Figure 1. Percentages of residential care communities using electronic health records, by selected

community characteristics: United States, 2010

0 5 10 15

Percent

20 25 30

All residential care communities 17

4–25 beds 14

26 or more beds 25

Not-for-profit 26

Private, for-profit 16

Chain-affiliated 23

Not chain-affiliated 14

Colocated 29

Not colocated 14

Nonmetropolitan statistical area 22

Metropolitan statistical area 16

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

NCHS Data Brief ■ No. 128 ■ September 2013

■ 2 ■

• In 2010, only 17% of residential care communities used electronic health records (Figure 1).

• One-quarter of larger residential care communities (those with 26 or more beds) used

electronic health records, compared with 14% of smaller communities (4–25 beds).

• Not-for-profit (26%) and chain-affiliated (23%) residential care communities were

more likely to use electronic health records than for-profit (16%) and nonchain (14%)

communities.

• Residential care communities colocated with another care setting (29%) and located in a

nonmetropolitan statistical area (22%) were more likely than those not colocated (14%) and

in a metropolitan statistical area (16%) to use electronic health records.

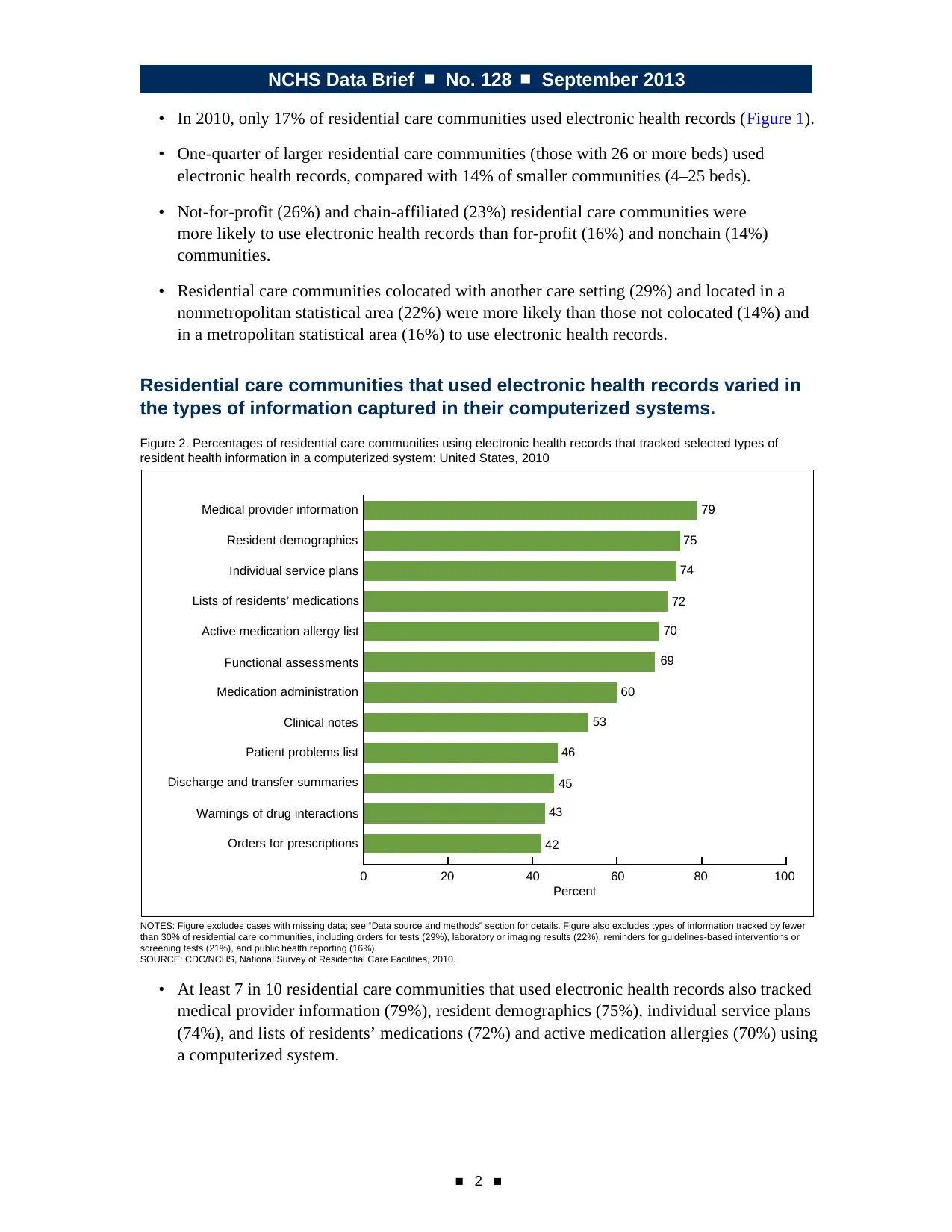

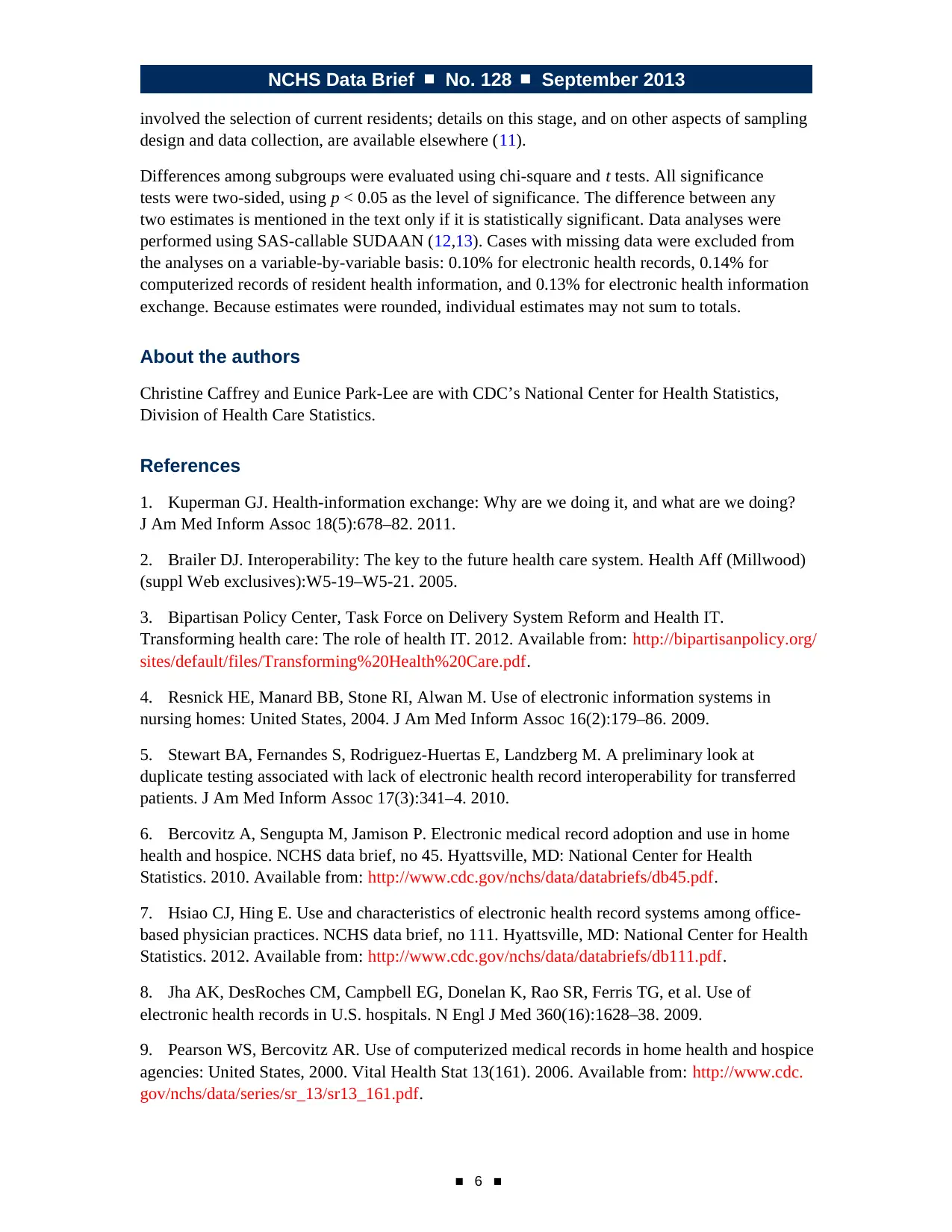

Residential care communities that used electronic health records varied in

the types of information captured in their computerized systems.

Figure 2. Percentages of residential care communities using electronic health records that tracked selected types of

resident health information in a computerized system: United States, 2010

NOTES: Figure excludes cases with missing data; see “Data source and methods” section for details. Figure also excludes types of information tracked by fewer

than 30% of residential care communities, including orders for tests (29%), laboratory or imaging results (22%), reminders for guidelines-based interventions or

screening tests (21%), and public health reporting (16%).

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Survey of Residential Care Facilities, 2010.

0 20 40 60

Percent

80

79

75

74

72

70

69

60

53

46

45

43

42

100

Orders for prescriptions

Warnings of drug interactions

Discharge and transfer summaries

Patient problems list

Clinical notes

Medication administration

Functional assessments

Active medication allergy list

Lists of residents’ medications

Individual service plans

Resident demographics

Medical provider information

• At least 7 in 10 residential care communities that used electronic health records also tracked

medical provider information (79%), resident demographics (75%), individual service plans

(74%), and lists of residents’ medications (72%) and active medication allergies (70%) using

a computerized system.

■ 2 ■

• In 2010, only 17% of residential care communities used electronic health records (Figure 1).

• One-quarter of larger residential care communities (those with 26 or more beds) used

electronic health records, compared with 14% of smaller communities (4–25 beds).

• Not-for-profit (26%) and chain-affiliated (23%) residential care communities were

more likely to use electronic health records than for-profit (16%) and nonchain (14%)

communities.

• Residential care communities colocated with another care setting (29%) and located in a

nonmetropolitan statistical area (22%) were more likely than those not colocated (14%) and

in a metropolitan statistical area (16%) to use electronic health records.

Residential care communities that used electronic health records varied in

the types of information captured in their computerized systems.

Figure 2. Percentages of residential care communities using electronic health records that tracked selected types of

resident health information in a computerized system: United States, 2010

NOTES: Figure excludes cases with missing data; see “Data source and methods” section for details. Figure also excludes types of information tracked by fewer

than 30% of residential care communities, including orders for tests (29%), laboratory or imaging results (22%), reminders for guidelines-based interventions or

screening tests (21%), and public health reporting (16%).

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Survey of Residential Care Facilities, 2010.

0 20 40 60

Percent

80

79

75

74

72

70

69

60

53

46

45

43

42

100

Orders for prescriptions

Warnings of drug interactions

Discharge and transfer summaries

Patient problems list

Clinical notes

Medication administration

Functional assessments

Active medication allergy list

Lists of residents’ medications

Individual service plans

Resident demographics

Medical provider information

• At least 7 in 10 residential care communities that used electronic health records also tracked

medical provider information (79%), resident demographics (75%), individual service plans

(74%), and lists of residents’ medications (72%) and active medication allergies (70%) using

a computerized system.

NCHS Data Brief ■ No. 128 ■ September 2013

■ 3 ■

• More than one-half of residential care communities that used electronic health records

tracked functional assessments (69%), medication administration (60%), and clinical notes

(53%).

• About 4 in 10 residential care communities that used electronic health records tracked

patient problems (46%), discharge and transfer summaries (45%), warnings of drug

interactions or contraindications (43%), and orders for prescriptions (42%) (Figure 2).

• Less than one-third of residential care communities that used electronic health records

tracked orders for tests (29%), laboratory or imaging results (22%), reminders for

guidelines-based interventions or screening tests (21%), and public health reporting (16%).

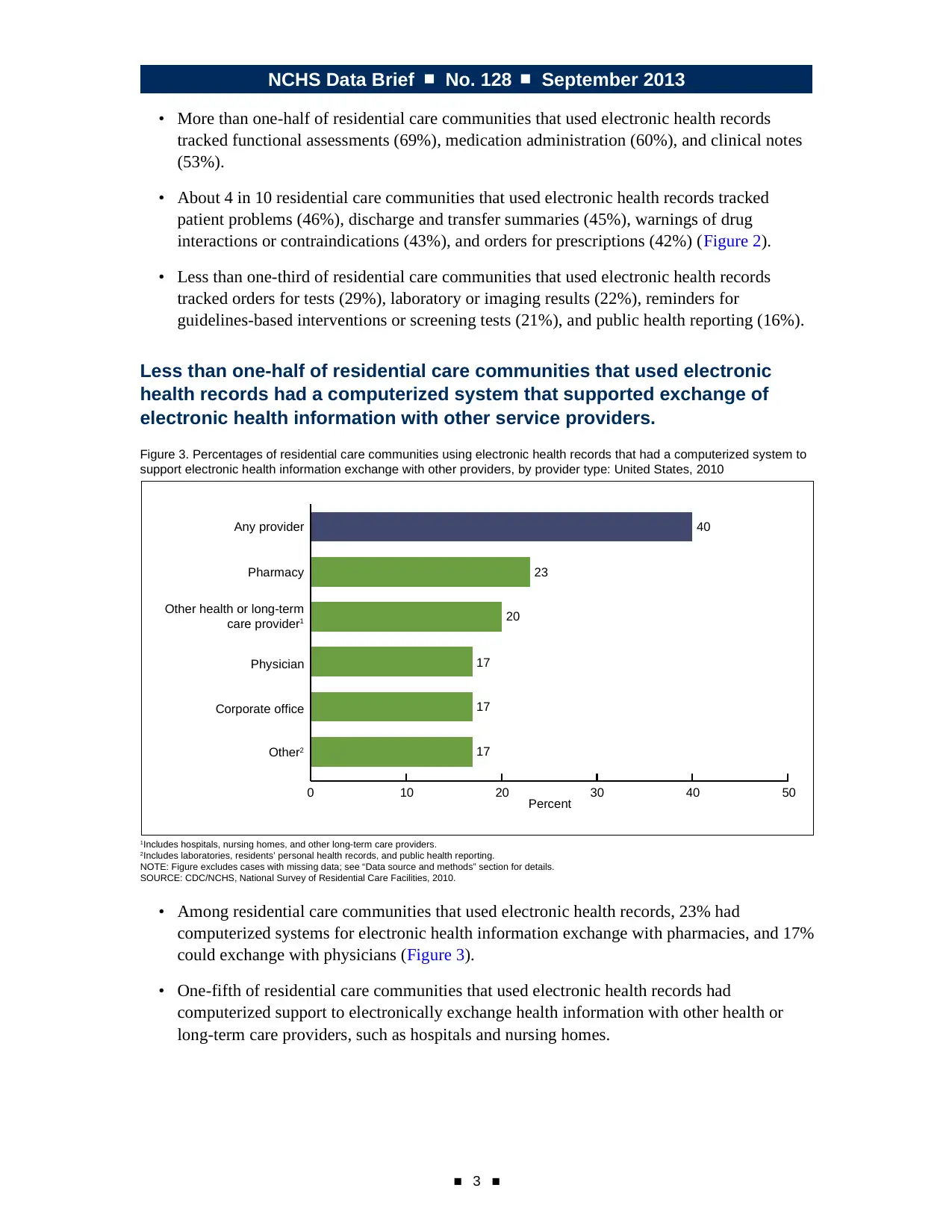

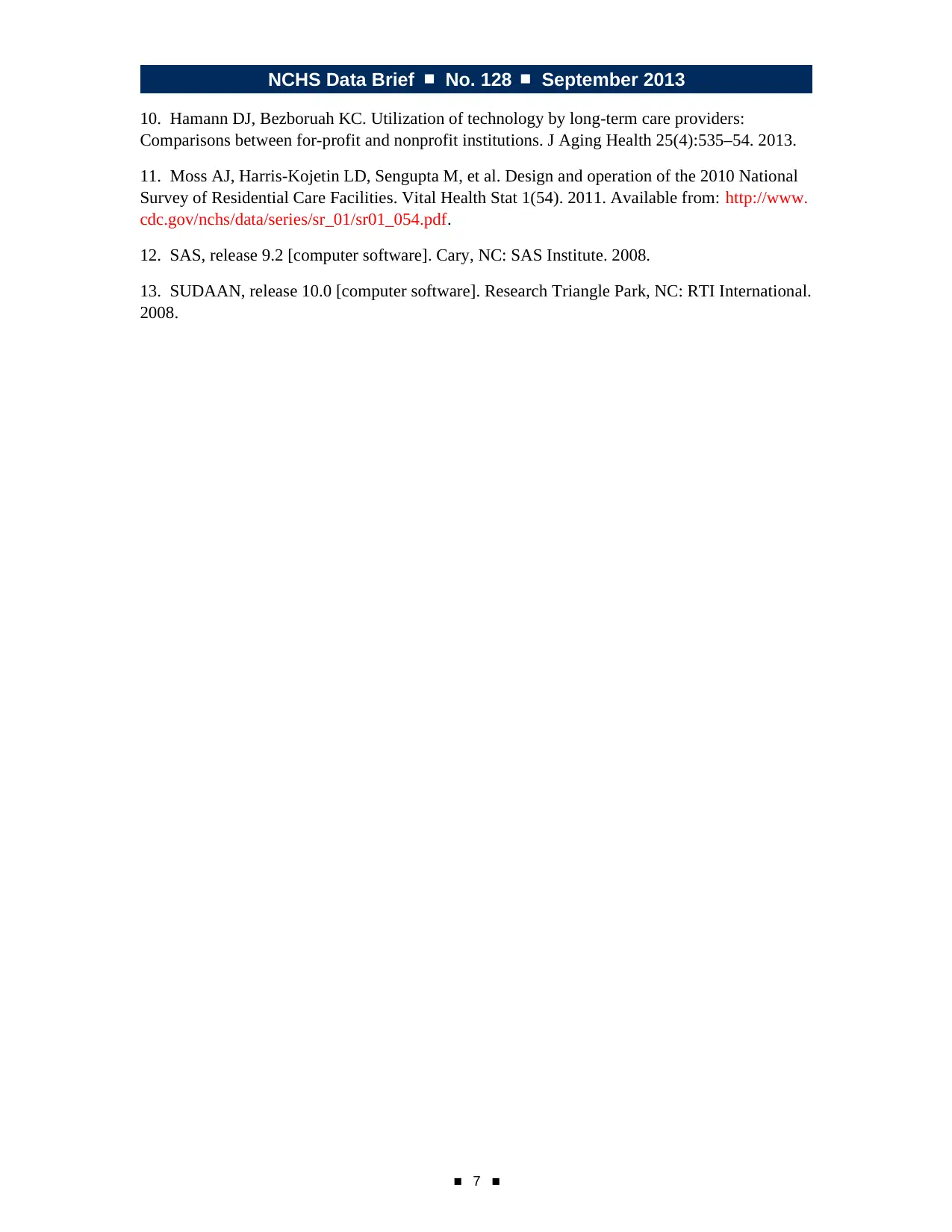

Less than one-half of residential care communities that used electronic

health records had a computerized system that supported exchange of

electronic health information with other service providers.

Figure 3. Percentages of residential care communities using electronic health records that had a computerized system to

support electronic health information exchange with other providers, by provider type: United States, 2010

1Includes hospitals, nursing homes, and other long-term care providers.

2Includes laboratories, residents’ personal health records, and public health reporting.

NOTE: Figure excludes cases with missing data; see “Data source and methods” section for details.

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Survey of Residential Care Facilities, 2010.

0 10 20 30

Percent 40 50

40

23

20

17

17

17Other2

Corporate office

Physician

Other health or long-term

care provider1

Pharmacy

Any provider

• Among residential care communities that used electronic health records, 23% had

computerized systems for electronic health information exchange with pharmacies, and 17%

could exchange with physicians (Figure 3).

• One-fifth of residential care communities that used electronic health records had

computerized support to electronically exchange health information with other health or

long-term care providers, such as hospitals and nursing homes.

■ 3 ■

• More than one-half of residential care communities that used electronic health records

tracked functional assessments (69%), medication administration (60%), and clinical notes

(53%).

• About 4 in 10 residential care communities that used electronic health records tracked

patient problems (46%), discharge and transfer summaries (45%), warnings of drug

interactions or contraindications (43%), and orders for prescriptions (42%) (Figure 2).

• Less than one-third of residential care communities that used electronic health records

tracked orders for tests (29%), laboratory or imaging results (22%), reminders for

guidelines-based interventions or screening tests (21%), and public health reporting (16%).

Less than one-half of residential care communities that used electronic

health records had a computerized system that supported exchange of

electronic health information with other service providers.

Figure 3. Percentages of residential care communities using electronic health records that had a computerized system to

support electronic health information exchange with other providers, by provider type: United States, 2010

1Includes hospitals, nursing homes, and other long-term care providers.

2Includes laboratories, residents’ personal health records, and public health reporting.

NOTE: Figure excludes cases with missing data; see “Data source and methods” section for details.

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Survey of Residential Care Facilities, 2010.

0 10 20 30

Percent 40 50

40

23

20

17

17

17Other2

Corporate office

Physician

Other health or long-term

care provider1

Pharmacy

Any provider

• Among residential care communities that used electronic health records, 23% had

computerized systems for electronic health information exchange with pharmacies, and 17%

could exchange with physicians (Figure 3).

• One-fifth of residential care communities that used electronic health records had

computerized support to electronically exchange health information with other health or

long-term care providers, such as hospitals and nursing homes.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

NCHS Data Brief ■ No. 128 ■ September 2013

■ 4 ■

Summary

In 2010, 17% of residential care communities reported that they used electronic health records.

These communities had different characteristics than those without electronic health records.

Communities that had electronic health records were more likely to be larger, to have

not-for-profit ownership, to be colocated with other care settings, and to be in a nonmetropolitan

statistical area. Medical provider information, resident demographics, individual service plans,

and lists of residents’ medications and active medication allergies were the most common

categories of resident health information recorded using a computerized system. Forty percent of

residential care communities that used electronic health records had a computerized system that

supported electronic health information exchange with one or more types of service providers.

Almost one-quarter had computerized support for exchanging electronic health information with

pharmacies.

This report has provided baseline findings on the use of electronic health record and electronic

health information exchange systems by residential care communities. This information should

be relevant to discussions on the role of residential care communities; the effective transition

from hospitals to residential care communities or other long-term care settings; avoidable

rehospitalizations; and helping persons who live with multiple chronic conditions better manage

their health care.

Definitions

Residential care communities: Includes assisted-living facilities and similar residential care

communities (e.g., personal care homes, adult care homes, board care homes, and adult foster

care) that meet the study eligibility criteria described in the “Data source and methods” section.

Electronic health records: Use was identified based on provider self-report in response to the

question, “Other than for accounting or billing purposes, does this facility use electronic health

records? This is a computerized version of the resident’s health and personal information used in

the management of the resident’s health care.” All providers were asked this question.

Computerized resident health information: Use was identified based on provider self-report

in response to the question, “Which of the following computerized capabilities does this

facility have?” Included were 16 types of computerized resident health information: resident

demographics, medical provider information, functional assessments, individual service plans,

clinical notes, patient problems list, medication administration, lists of residents’ medications

and active medication allergies, orders for prescriptions, warning of drug interactions or

contraindications, orders for tests, laboratory and imaging results, reminders for guidelines-based

interventions or screening tests, discharge and transfer summaries, and public health reporting.

All providers were asked this question.

Electronic health information exchange system: Use was identified based on provider self-report

in response to the question, “Does this facility’s computerized system support electronic health

information exchange with any of the following?” Nine different types of service providers were

included: physician, nursing home, hospital, pharmacy, laboratories, other health or long-term

care provider, residents’ personal health record, public health reporting, and corporate office.

To be asked this question, residential care communities had to have a computerized system

■ 4 ■

Summary

In 2010, 17% of residential care communities reported that they used electronic health records.

These communities had different characteristics than those without electronic health records.

Communities that had electronic health records were more likely to be larger, to have

not-for-profit ownership, to be colocated with other care settings, and to be in a nonmetropolitan

statistical area. Medical provider information, resident demographics, individual service plans,

and lists of residents’ medications and active medication allergies were the most common

categories of resident health information recorded using a computerized system. Forty percent of

residential care communities that used electronic health records had a computerized system that

supported electronic health information exchange with one or more types of service providers.

Almost one-quarter had computerized support for exchanging electronic health information with

pharmacies.

This report has provided baseline findings on the use of electronic health record and electronic

health information exchange systems by residential care communities. This information should

be relevant to discussions on the role of residential care communities; the effective transition

from hospitals to residential care communities or other long-term care settings; avoidable

rehospitalizations; and helping persons who live with multiple chronic conditions better manage

their health care.

Definitions

Residential care communities: Includes assisted-living facilities and similar residential care

communities (e.g., personal care homes, adult care homes, board care homes, and adult foster

care) that meet the study eligibility criteria described in the “Data source and methods” section.

Electronic health records: Use was identified based on provider self-report in response to the

question, “Other than for accounting or billing purposes, does this facility use electronic health

records? This is a computerized version of the resident’s health and personal information used in

the management of the resident’s health care.” All providers were asked this question.

Computerized resident health information: Use was identified based on provider self-report

in response to the question, “Which of the following computerized capabilities does this

facility have?” Included were 16 types of computerized resident health information: resident

demographics, medical provider information, functional assessments, individual service plans,

clinical notes, patient problems list, medication administration, lists of residents’ medications

and active medication allergies, orders for prescriptions, warning of drug interactions or

contraindications, orders for tests, laboratory and imaging results, reminders for guidelines-based

interventions or screening tests, discharge and transfer summaries, and public health reporting.

All providers were asked this question.

Electronic health information exchange system: Use was identified based on provider self-report

in response to the question, “Does this facility’s computerized system support electronic health

information exchange with any of the following?” Nine different types of service providers were

included: physician, nursing home, hospital, pharmacy, laboratories, other health or long-term

care provider, residents’ personal health record, public health reporting, and corporate office.

To be asked this question, residential care communities had to have a computerized system

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

NCHS Data Brief ■ No. 128 ■ September 2013

■ 5 ■

for tracking at least 1 of the 16 different types of resident health information. Residential care

communities that did not track any of these types of information were coded as not having a

computerized system that supported electronic health information exchange with other service

providers. Four percent of residential care communities with electronic health records reported

that they did not track any of these types of resident health information in a computerized system.

Size: Categorized into two sizes based on the number of licensed, registered, or certified beds

(occupied and unoccupied) in a residential care community: 4–25 beds and 26 or more beds.

Ownership type: Categorized into two ownership types: private, for-profit; and not-for-profit.

The private, for-profit category included publicly traded facilities. Not-for-profit included private

nonprofit, as well as state, county, or local government ownership.

Chain affiliation: Having more than one community under common ownership or management.

This may include communities in-state or across multiple states. If communties were owned by a

chain, group, or multifacility system, they were coded as chain-affiliated.

Colocation with another care setting: Determined based on provider self-report in response to

the question, “Are any of the following types of places on the same property or at this same

location?” Four types of places were included: independent living; nursing home; rehabilitation,

subacute, or postacute unit in a nursing home; and hospital. Residential care communities were

considered to be colocated with another care setting if they had one or more of these places on the

same property or at the same location.

Metropolitan statistical area: Refers to a county or group of contiguous counties that contain at

least one urbanized area with a population of 50,000 or more. A metropolitan statistical area may

contain other counties that are economically and socially integrated with the central county, as

measured by commuting.

Data source and methods

Facility data from the 2010 NSRCF, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), were used for these analyses.

To be eligible for the study, residential care communities must (a) have been licensed, registered,

listed, certified, or otherwise regulated by the state and have four or more licensed, certified, or

registered beds; (b) have at least one resident currently living in the community; and (c) provide

room and board with at least two meals a day, around-the-clock onsite supervision, and help

with personal care such as bathing and dressing or health-related services such as medication

management. These communities served a predominantly adult population. Communities

licensed to serve severely mentally ill or intellectually or developmentally disabled populations

exclusively were excluded. Nursing homes were also excluded unless they had a unit or wing that

met the above definition and residents could be enumerated separately.

The 2010 NSRCF used a stratified two-stage probability sampling design. The first stage was the

selection of residential care communities from the sampling frame representing the universe of

residential care communities in the United States. For the 2010 NSRCF, 3,605 residential care

communities were sampled with probability proportional to size. Interviews were completed with

2,302 residential care communities, for a first-stage community unweighted response rate of 79%

and a weighted response rate (for differential probabilities of selection) of 81%. The second stage

■ 5 ■

for tracking at least 1 of the 16 different types of resident health information. Residential care

communities that did not track any of these types of information were coded as not having a

computerized system that supported electronic health information exchange with other service

providers. Four percent of residential care communities with electronic health records reported

that they did not track any of these types of resident health information in a computerized system.

Size: Categorized into two sizes based on the number of licensed, registered, or certified beds

(occupied and unoccupied) in a residential care community: 4–25 beds and 26 or more beds.

Ownership type: Categorized into two ownership types: private, for-profit; and not-for-profit.

The private, for-profit category included publicly traded facilities. Not-for-profit included private

nonprofit, as well as state, county, or local government ownership.

Chain affiliation: Having more than one community under common ownership or management.

This may include communities in-state or across multiple states. If communties were owned by a

chain, group, or multifacility system, they were coded as chain-affiliated.

Colocation with another care setting: Determined based on provider self-report in response to

the question, “Are any of the following types of places on the same property or at this same

location?” Four types of places were included: independent living; nursing home; rehabilitation,

subacute, or postacute unit in a nursing home; and hospital. Residential care communities were

considered to be colocated with another care setting if they had one or more of these places on the

same property or at the same location.

Metropolitan statistical area: Refers to a county or group of contiguous counties that contain at

least one urbanized area with a population of 50,000 or more. A metropolitan statistical area may

contain other counties that are economically and socially integrated with the central county, as

measured by commuting.

Data source and methods

Facility data from the 2010 NSRCF, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), were used for these analyses.

To be eligible for the study, residential care communities must (a) have been licensed, registered,

listed, certified, or otherwise regulated by the state and have four or more licensed, certified, or

registered beds; (b) have at least one resident currently living in the community; and (c) provide

room and board with at least two meals a day, around-the-clock onsite supervision, and help

with personal care such as bathing and dressing or health-related services such as medication

management. These communities served a predominantly adult population. Communities

licensed to serve severely mentally ill or intellectually or developmentally disabled populations

exclusively were excluded. Nursing homes were also excluded unless they had a unit or wing that

met the above definition and residents could be enumerated separately.

The 2010 NSRCF used a stratified two-stage probability sampling design. The first stage was the

selection of residential care communities from the sampling frame representing the universe of

residential care communities in the United States. For the 2010 NSRCF, 3,605 residential care

communities were sampled with probability proportional to size. Interviews were completed with

2,302 residential care communities, for a first-stage community unweighted response rate of 79%

and a weighted response rate (for differential probabilities of selection) of 81%. The second stage

NCHS Data Brief ■ No. 128 ■ September 2013

■ 6 ■

involved the selection of current residents; details on this stage, and on other aspects of sampling

design and data collection, are available elsewhere (11).

Differences among subgroups were evaluated using chi-square and t tests. All significance

tests were two-sided, using p < 0.05 as the level of significance. The difference between any

two estimates is mentioned in the text only if it is statistically significant. Data analyses were

performed using SAS-callable SUDAAN (12,13). Cases with missing data were excluded from

the analyses on a variable-by-variable basis: 0.10% for electronic health records, 0.14% for

computerized records of resident health information, and 0.13% for electronic health information

exchange. Because estimates were rounded, individual estimates may not sum to totals.

About the authors

Christine Caffrey and Eunice Park-Lee are with CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics,

Division of Health Care Statistics.

References

1. Kuperman GJ. Health-information exchange: Why are we doing it, and what are we doing?

J Am Med Inform Assoc 18(5):678–82. 2011.

2. Brailer DJ. Interoperability: The key to the future health care system. Health Aff (Millwood)

(suppl Web exclusives):W5-19–W5-21. 2005.

3. Bipartisan Policy Center, Task Force on Delivery System Reform and Health IT.

Transforming health care: The role of health IT. 2012. Available from: http://bipartisanpolicy.org/

sites/default/files/Transforming%20Health%20Care.pdf.

4. Resnick HE, Manard BB, Stone RI, Alwan M. Use of electronic information systems in

nursing homes: United States, 2004. J Am Med Inform Assoc 16(2):179–86. 2009.

5. Stewart BA, Fernandes S, Rodriguez-Huertas E, Landzberg M. A preliminary look at

duplicate testing associated with lack of electronic health record interoperability for transferred

patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc 17(3):341–4. 2010.

6. Bercovitz A, Sengupta M, Jamison P. Electronic medical record adoption and use in home

health and hospice. NCHS data brief, no 45. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health

Statistics. 2010. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db45.pdf.

7. Hsiao CJ, Hing E. Use and characteristics of electronic health record systems among office-

based physician practices. NCHS data brief, no 111. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health

Statistics. 2012. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db111.pdf.

8. Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Donelan K, Rao SR, Ferris TG, et al. Use of

electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med 360(16):1628–38. 2009.

9. Pearson WS, Bercovitz AR. Use of computerized medical records in home health and hospice

agencies: United States, 2000. Vital Health Stat 13(161). 2006. Available from: http://www.cdc.

gov/nchs/data/series/sr_13/sr13_161.pdf.

■ 6 ■

involved the selection of current residents; details on this stage, and on other aspects of sampling

design and data collection, are available elsewhere (11).

Differences among subgroups were evaluated using chi-square and t tests. All significance

tests were two-sided, using p < 0.05 as the level of significance. The difference between any

two estimates is mentioned in the text only if it is statistically significant. Data analyses were

performed using SAS-callable SUDAAN (12,13). Cases with missing data were excluded from

the analyses on a variable-by-variable basis: 0.10% for electronic health records, 0.14% for

computerized records of resident health information, and 0.13% for electronic health information

exchange. Because estimates were rounded, individual estimates may not sum to totals.

About the authors

Christine Caffrey and Eunice Park-Lee are with CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics,

Division of Health Care Statistics.

References

1. Kuperman GJ. Health-information exchange: Why are we doing it, and what are we doing?

J Am Med Inform Assoc 18(5):678–82. 2011.

2. Brailer DJ. Interoperability: The key to the future health care system. Health Aff (Millwood)

(suppl Web exclusives):W5-19–W5-21. 2005.

3. Bipartisan Policy Center, Task Force on Delivery System Reform and Health IT.

Transforming health care: The role of health IT. 2012. Available from: http://bipartisanpolicy.org/

sites/default/files/Transforming%20Health%20Care.pdf.

4. Resnick HE, Manard BB, Stone RI, Alwan M. Use of electronic information systems in

nursing homes: United States, 2004. J Am Med Inform Assoc 16(2):179–86. 2009.

5. Stewart BA, Fernandes S, Rodriguez-Huertas E, Landzberg M. A preliminary look at

duplicate testing associated with lack of electronic health record interoperability for transferred

patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc 17(3):341–4. 2010.

6. Bercovitz A, Sengupta M, Jamison P. Electronic medical record adoption and use in home

health and hospice. NCHS data brief, no 45. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health

Statistics. 2010. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db45.pdf.

7. Hsiao CJ, Hing E. Use and characteristics of electronic health record systems among office-

based physician practices. NCHS data brief, no 111. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health

Statistics. 2012. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db111.pdf.

8. Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Donelan K, Rao SR, Ferris TG, et al. Use of

electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med 360(16):1628–38. 2009.

9. Pearson WS, Bercovitz AR. Use of computerized medical records in home health and hospice

agencies: United States, 2000. Vital Health Stat 13(161). 2006. Available from: http://www.cdc.

gov/nchs/data/series/sr_13/sr13_161.pdf.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

NCHS Data Brief ■ No. 128 ■ September 2013

■ 7 ■

10. Hamann DJ, Bezboruah KC. Utilization of technology by long-term care providers:

Comparisons between for-profit and nonprofit institutions. J Aging Health 25(4):535–54. 2013.

11. Moss AJ, Harris-Kojetin LD, Sengupta M, et al. Design and operation of the 2010 National

Survey of Residential Care Facilities. Vital Health Stat 1(54). 2011. Available from: http://www.

cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_01/sr01_054.pdf.

12. SAS, release 9.2 [computer software]. Cary, NC: SAS Institute. 2008.

13. SUDAAN, release 10.0 [computer software]. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International.

2008.

■ 7 ■

10. Hamann DJ, Bezboruah KC. Utilization of technology by long-term care providers:

Comparisons between for-profit and nonprofit institutions. J Aging Health 25(4):535–54. 2013.

11. Moss AJ, Harris-Kojetin LD, Sengupta M, et al. Design and operation of the 2010 National

Survey of Residential Care Facilities. Vital Health Stat 1(54). 2011. Available from: http://www.

cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_01/sr01_054.pdf.

12. SAS, release 9.2 [computer software]. Cary, NC: SAS Institute. 2008.

13. SUDAAN, release 10.0 [computer software]. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International.

2008.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

NCHS Data Brief ■ No. 128 ■ September 2013

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF

HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

3311 Toledo Road, Room 5419

Hyattsville, MD 20782

OFFICIAL BUSINESS

PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE, $300

FIRST CLASS MAIL

POSTAGE & FEES PAID

CDC/NCHS

PERMIT NO. G-284

Suggested citation

Caffrey C, Park-Lee E. Use of electronic

health records in residential care

communities. NCHS data brief, no 128.

Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health

Statistics. 2013.

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in

the public domain and may be reproduced

or copied without permission; citation as to

source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health

Statistics

Charles J. Rothwell, M.S., Acting Director

Jennifer H. Madans, Ph.D., Associate

Director for Science

Division of Health Care Statistics

Clarice Brown, M.S., Director

For e-mail updates on NCHS publication

releases, subscribe online at:

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/govdelivery.htm.

For questions or general information

about NCHS:

Tel: 1–800–CDC–INFO (1–800–232–4636)

TTY: 1–888–232–6348

Internet: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs

Online request form: http://www.cdc.gov/

cdc-info/requestform.html

ISSN 1941–4927 Print ed.

ISSN 1941–4935 Online ed.

DHHS Publication No. 2013–1209

CS242703

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF

HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

3311 Toledo Road, Room 5419

Hyattsville, MD 20782

OFFICIAL BUSINESS

PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE, $300

FIRST CLASS MAIL

POSTAGE & FEES PAID

CDC/NCHS

PERMIT NO. G-284

Suggested citation

Caffrey C, Park-Lee E. Use of electronic

health records in residential care

communities. NCHS data brief, no 128.

Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health

Statistics. 2013.

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in

the public domain and may be reproduced

or copied without permission; citation as to

source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health

Statistics

Charles J. Rothwell, M.S., Acting Director

Jennifer H. Madans, Ph.D., Associate

Director for Science

Division of Health Care Statistics

Clarice Brown, M.S., Director

For e-mail updates on NCHS publication

releases, subscribe online at:

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/govdelivery.htm.

For questions or general information

about NCHS:

Tel: 1–800–CDC–INFO (1–800–232–4636)

TTY: 1–888–232–6348

Internet: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs

Online request form: http://www.cdc.gov/

cdc-info/requestform.html

ISSN 1941–4927 Print ed.

ISSN 1941–4935 Online ed.

DHHS Publication No. 2013–1209

CS242703

1 out of 8

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.